Abstract

Purpose

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a condition which causes significant difficulties in physical, cognitive and psychological domains. It is a progressive condition which people have to live with for a long time; consequently, there is a need to understand what contributes to individual adjustment. This review aimed to answer the question “how do individuals adjust to PD?”

Method

A systematic search of three databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycINFO) was carried out of papers documenting the adjustment process when living with PD and the findings were synthesised using a meta-ethnographic approach.

Results

After exclusion based on eligibility criteria, 21 articles were included and were assessed for quality prior to analysing the data. Three main themes are proposed relating to the process of adjustment: “maintaining a coherent sense of self”, “feeling in control” and “holding a positive mindset”. Although many of the studies described challenges of living with PD, the results are dominated by the determination of individuals to self-manage their condition and maintain positive wellbeing.

Conclusion

The results highlight the need to empower patients to self-manage their illness, mitigating the effects of Parkinson’s disease and supporting future wellbeing.

Individual identity disruption impacts on the self-value and sense of self coherence in individuals living with Parkinson’s disease.

Healthcare professionals should appreciate the complexity of the adjustment process which is related to the ability to maintain a coherent sense of self, to feel in control and to hold a positive mindset.

Healthcare professionals should ensure information and knowledge related to self-management is tailored to an individual’s understanding and experience of the disease.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a debilitating, progressive neurological condition normally diagnosed after the age of 50 although onset at a younger age is possible. The prevalence of PD is between 100 and 300/100,000 population and due to the general aging of the population, the number of PD patients is expected to double by 2030 [Citation1]. The symptoms of PD are wide-ranging, but individuals typically start with motor difficulties including tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and loss of postural reflexes [Citation2], although other physical symptoms commonly experienced include excessive saliva and dribbling, urinary urgency, and constipation [Citation3]. Cognitive symptoms are also common and in later stages many individuals can experience dementia [Citation4]. Such symptoms frequently cause difficulties for an individual to carry out daily activities and may contribute to activity limitations [Citation4]. Furthermore, psychological difficulties are also common. The most commonly experienced psychological difficulty in PD is depression; although prevalence rates vary widely, the average prevalence is about 35% [Citation5]. Anxiety is also frequently experienced, the reported current prevalence rates ranging between 12.8% and 43.0% [Citation6]. Anxiety and depression co-occur quite often and there is evidence to suggest that anxiety may cause a significant deterioration in physical symptoms, which may in turn exacerbate anxiety [Citation7]. Psychotic symptoms can also be experienced by individuals with PD, typically manifesting around 10 years after the initial diagnosis [Citation7]. Estimates of the prevalence of psychotic symptoms in individuals with PD vary from 15% to 52% in those who receive treatment [Citation7]. In the early stages, psychosis in PD typically occurs with a high level of insight, and psychological support can be sufficient in managing symptoms. However, psychotic symptoms are typically recurrent and likely to worsen over time, resulting in significant anxiety and increasing the likelihood of social and functional impairment [Citation8]. Additionally, apathy occurs in approximately 40% of individuals with PD [Citation9] and can occur independently of depression and cognitive impairment [Citation10]. Psychological difficulties and quality of life in people with PD vary according to gender, with women often having more positive disease outcomes with regard to emotion processing, non-motor symptoms and cognitive symptoms [Citation11]. Although prevalence of PD differs across ethnicity, where it has been shown to be highest among Hispanics, followed by non-Hispanic Whites, Asians and then Blacks [Citation12], the severity of anxiety and depression has not been observed to differ across ethnic groups [Citation13]. Additionally, whilst age does not seem to be a predictor of disease severity or disability, quality of life is significantly worse in young onset than in older onset individuals and they also report greater perceived stigma, life disruption and depression [Citation14]. It is clear that both the prevalence and the psychological burden of PD do not affect individuals equally; nevertheless, the research highlights the extensive impact of psychological difficulties on excess disability, worse quality of life, poorer outcomes and increased caregiver burden [Citation15–17]. In this context it is essential to better understand how individuals develop the ability to adjust despite both the motor and psychological challenges.

Despite growing literature in the area, there is still little consensus on what constitutes psychological adjustment, especially with regard to individuals living with a chronic illness. Typically, literature has framed the concept as both a state and a process. Adjustment as a state is the outcome of an individual’s process of adaptation. Optimal adjustment is when the person manages to balance the difficulties of their condition with a good quality of life [Citation18], resulting in good physical, cognitive and emotional functioning [Citation19]. The state of adjustment is normally defined according to objective measurement such as low negative affect and maintaining function, but this may not necessarily reflect subjective considerations of an individual [Citation20]. Additionally, defining adjustment this way implies that poor adjustment can be considered a mental health problem [Citation21] yet this perspective is not seen as helpful in many people with a chronic illness. As such, defining adjustment as a state is limited in its ability to address the complexity of adjusting to living with a chronic illness.

In contrast, defining adjustment as a process enables one to consider the idiosyncratic nature of how an individual adapts to a chronic illness, which considers how this process may not be captured by functional outcomes [Citation21]. Considering adjustment as a process acknowledges how adjustment is likely to be condition specific and that the adaptive tasks required in adjusting to a condition will vary according to the specific illness challenges. Furthermore, the presence of negative affect may at times be an understandable and even adaptive consequence of deteriorating function, as long as this negative affect is not prolonged [Citation21]. It is important that our understanding of adjustment acknowledges the fluctuating and on-going nature of the process, rather than considering adjustment as a static factor defined by outcomes. As such, adjustment in this review was based on the Moss-Morris (2013) model of adjustment. This model defines adjustment as the process by which an individual is able to return to equilibrium in following specific illness triggers (such as when one receives their diagnosis or in the case of physical deterioration) or maintain equilibrium in the face of day to day illness [Citation21]. Equilibrium involves factors such as good illness management, positive affect and less illness interference on an individual’s roles and relationships [Citation21]. Adjustment in this sense is a dynamic process, as factors which may be successful for adjustment at one stage of disease severity may no longer be successful with advancing deterioration. This is especially relevant in PD, given in the latter stages motor control and active problem-solving strategies may be rendered impossible by worsening of symptoms. When we take a more nuanced focus on aspects of the adjustment process, we can move beyond consideration of individual experience of the condition, the symptoms and the treatment effects, to a more interpretive understanding of how the condition-and crucially too its progression-fundamentally affects the perception of the self.

Previous meta-syntheses of qualitative studies have aimed to explore the subjective experience of PD [Citation22,Citation23]. An earlier review aimed to identify factors which may influence an individual’s wellbeing or feelings of hope and highlighted the importance of individuals with PD retaining their pre-illness identity and maintaining normality as far as possible [Citation22]. Adjustment was considered to involve individuals acknowledging something was wrong and accepting both the diagnosis and its implications for their identity. Similarly, a more recent review by Rutten and colleagues developed a holistic model of the subjective experience of PD from the individual’s perspective and the factors which contribute to this experience [Citation23]. This review added a valuable contribution to the literature on how individuals adjust to PD, where the authors described how individuals with PD undergo a process of identifying whether their core self-beliefs can be maintained in the context of their condition. Where previously held beliefs about the self can be assimilated with condition specific limitations, equilibrium is assumed to occur. As suggested by the aforementioned Moss-Morris model, the authors clearly articulate aspects of the adjustment process in PD. Although both earlier reviews help to inform what might contribute to an individual’s adjustment process, the theoretical orientation of the papers were on the experience of PD, whereas the current paper focuses specifically on the adjustment process. With its narrower focus, the present review can more fully articulate aspects of the adjustment process not accounted for by the Rutten review [Citation23].

Aims

The purpose of this study was to address gaps in the existing literature by systematically identifying, analysis and synthesizing the evidence on adjusting to Parkinson’s disease. Specifically, the review aimed to answer the question of “How do individuals adjust to living with Parkinson’s disease?”

Methods

A meta-ethnography was chosen because it is an approach which not only synthesises information but also seeks to broaden conceptual knowledge, as was the aim of the present review [Citation24]. Meta-ethnography was developed by Noblit and Hare following their perceived failure of existing approaches to synthesis to preserve the context of the individual studies and their recognition of the importance of this context in shaping the findings of a study [Citation24]. The approach of meta-ethnography is therefore informed by an interpretive rather than aggregative intent [Citation25].

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Citation26] and followed the seven-step process detailed by Noblit and Hare [Citation25]. These are as follows: getting started, deciding what is relevant to the initial interest, reading the studies, determining how the studies are related, translating the studies into one another, synthesising translations, and expressing the synthesis.

Identifying relevant papers

The first stage of the meta-synthesis was “getting started,” which involved exploring the existing literature on individuals living with PD; this informed the identification of the precise focus of the review in highlighting the limited existing literature. Following this, relevant papers were identified by searching three databases: MEDLINE Complete, CINAHL and PsycINFO. Following guidance from an academic librarian, the search involved three areas: (1) qualitative approaches, (2) adjustment and (3) Parkinson’s disease. details the search terms employed.

Table 1. Table displaying the search strategy and the terms used for each database.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for papers to be selected were: (1) used a qualitative approach to data collection (i.e., an approach which aimed to understand people’s beliefs, experiences or attitudes and generated non-numerical data [Citation27]) (2) peer-reviewed, (3), written in English (4) focused on the experience of the individual with PD rather than a caregiver, and (5) at least one major theme (or concept) focused on the process of adjustment. There was no requirement as to the date the paper was published and thus all papers held by the databases were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: (1) focused on adjustment after deep brain stimulation, (2) a comparative or dyadic study where the experiences of the individual with PD could not be clearly extracted (3) focused on adjustment of aspects not specific to the condition e.g., coping with menstruation in individuals with PD and (4) the focus was solely on barriers to optimal adjustment. Papers were excluded if they solely focused on barriers to optimal adjustment because the focus of the review is on the process of adjusting, not the difficulties of living with the condition. These are two distinct entities, and the converse of the challenges of living with PD cannot be assumed to contribute to adaptive adjustment to the condition.

Articles focused on the experience of living with PD were included if they described some of the processes which helped an individual to reach the outcome of “living well” (e.g., [Citation28]) but not merely if they only depicted the outcome of an individual’s adjustment (e.g., [Citation29]).

Search results

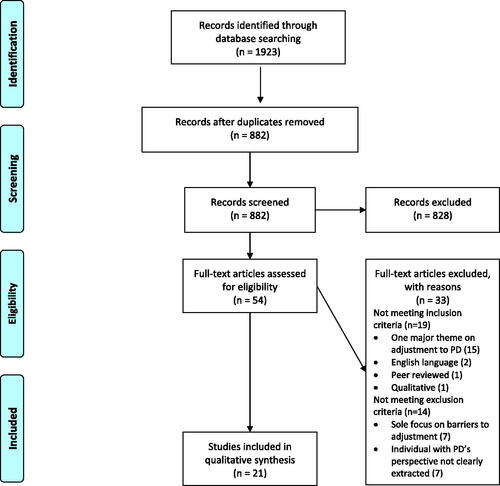

The original search was conducted in June 2020 and was updated in December 2020 and again in March 2021. An alert was set up within the databases which provided monthly updates of any new articles which would be identified by the original search, of which there were none. The most recent search identified 1923 articles across all databases-a total of 882 remained after duplicates were removed. The remaining papers were appraised for relevance based on the title and abstract. 828 were excluded because they were unrelated to the research question or did not meeting eligibility criteria. 54 papers were accessed in full, either because the abstract suggested potential relevance to the research question or because there was insufficient information to exclude them based on eligibility criteria. Of these, 33 were excluded; 19 did not meet the inclusion criteria and 14 met exclusion criteria. This resulted in 21 articles being identified as being of relevance for inclusion in the review. details the characteristics of the included studies. The process from initial searches to final identification of review articles is outlined in .

Table 2. Characteristics of the studies included for the synthesis.

Quality of the selected studies

Although not initially outlined as part of Noblit and Hare’s guidelines, the studies were assessed for quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). The use of critical appraisal tools is contentious, with some arguing that quality appraisal is never compatible with qualitative research methodology [Citation30]. However, if we are to use the findings of qualitative research to inform clinical practice, we need to be confident that the research is of a good enough quality [Citation31]. Although there is much debate about how, or whether, to assess the quality of qualitative research [Citation30], quality judgments are always made, and appraisal checklists can bring some transparency to this process. Given the use of quality assessment is cautioned, and the lack of agreement about what high quality qualitative research looks like, the CASP checklist was used to support critical engagement with the studies but not used to exclude any individual studies. The CASP checklist enables researchers to assess the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers and is widely used in clinical research (CASP, 2019). Assessing the quality of the papers using this checklist involved identifying the standard of methodological reporting and study robustness and focused on three key areas: validity of the research, rigour of the findings, and utility of the results. Studies were assessed based on eight appraisal questions and each question was given a score of one to three; one point was scored for weak explanations of a particular issue, two points were assigned to items which were addressed in the article but not fully elaborated upon and three points assigned to articles that extensively explained the issue at hand [Citation32]. The total possible score for the CASP is 24; articles in the present review ranged from 14 to 22, with the majority of papers scoring between 17 and 22. outlines quality assessment scores for each paper. The first author conducted the quality appraisal and then consulted with a colleague who conducted their own appraisal, to ensure consistency in the approach. Following this, discussion was had around where differences lay regarding individual scores and an agreed total score for each paper was determined. Differences between the decisions mainly centred around the requirements of papers to meet each score on the individual items. Higher quality articles typically gave a more thorough description of the data collection and analysis process and produced a more detailed account of their consideration of the ethical issues. Considering the final themes, each sub-theme was present in at least two of the three strongest papers and thus no subtheme depended solely on the weaker papers.

Table 3. Table outlining the evaluative process using the CASP tool.

Analysis

The translation followed the process outlined by Noblit and Hare [Citation25]. There are three possible types of relationships that guide translation and subsequent synthesis. The first of these is reciprocal, where similar concepts across the studies are translated into one another and overarching metaphors are revealed which provide explanatory power for the individual studies. The second type is refutational, where more elaborate translations are developed which uncover the relation between the main accounts of a study and competing explanations, or explore incongruences between studies. Finally, line of argument synthesis involves uncovering the larger inference which is implicitly conveyed in the studies but is not explicitly stated i.e., identifying the full picture from the individual pieces. The proposed model of adjustment, articulated in the findings, was developed during this line of argument synthesis and attempts to draw together the studies into a unified account of adjustment. Additionally, the concepts of first and second order constructs, developed by Britten [Citation32] following initial conceptualisation by Schutz [Citation33], were used to guide subsequent analysis. First order constructs reflect the participants’ interpretations to the original questions asked within a single study. Second order constructs reflect the author’s interpretations of the participants’ responses. Finally, third order constructs reflect the researcher’s interpretations of the original author’s interpretations. A meta-ethnographic approach rests upon these third order constructs, which allows for an interpretative account of the shared concepts in adjustment rather than merely combining themes together [Citation32]. Each paper was read and annotated in detail, with key concepts drawn out for each paper, reflective of second order constructs [Citation33]. Consideration was also given to divergent concepts and how these might reflect either aspects of the concept which were difficult for some individuals to achieve e.g., acceptance, or how a broader definition of the concept might capture such refutations. The key concepts were then synthesised to generate three key themes, the third order constructs, which seemed to capture the important aspects of individuals’ experience. This is detailed in . The first author undertook the analysis, but this was refined in discussion with the second and third authors which helped to maintain the quality of the original findings and uphold methodological rigour [Citation34].

Table 4. Constructing the synthesis through the generation of initial concepts to develop the final themes.

Findings

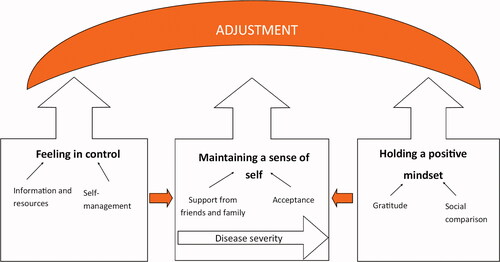

In synthesising the 21 papers, three main themes relating to how individuals adjust to living with PD were constructed: (1) maintaining a coherent sense of self, (2) feeling in control and (3) holding a positive mindset. The model in encompasses these three themes and proposes the relationship between these themes. Central to this model is the process of maintaining a coherent sense of self; a key aim of the adjustment process is to achieve equilibrium, in which an individual’s understanding of themselves is maintained alongside negotiation of the physical and cognitive limitations of PD. Maintaining a coherent sense of self is supported by both internal and external processes which enable an individual to feel in control and to hold a positive mindset.

Theme 1: maintaining a coherent sense of self

Maintaining a coherent sense of self felt to be important for individuals to adjust to the challenges of PD and to accommodate changes where necessary. There appeared a temporal dimension to this process. The early stages of the illness involved an individual’s initial recognition of the chronicity of their illness and what it meant for their identity. This involved understanding its progressive and terminal nature and acknowledging how on-going deterioration might limit their ability to continue with valued roles and activities. Individual responses were often aimed at preserving aspects of their pre-illness self, with the support of friends and family being crucial in this, in supporting them to do the activities they had always done and in encouraging them to retain valued roles. In later stages of the illness, given on-going deterioration in physical and mental ability, it was often not possible to maintain many aspects of their pre-illness identity. Here, acceptance provided the context for reshaping identity to incorporate the illness, in order to allow for positive self-evaluation and maintaining a coherent sense of self in the face of progressive deterioration.

Sub theme: support from friends and family

The support from friends and family was important in helping an individual to retain a valued social identity and maintain a coherent sense of self, finding the aspects of themselves which may initially have been lost following physical deterioration:

…. with the help of caring and supportive family members, a few special friends, doctors, and my husband I have been back to moving and finding my groove [Citation35].

Despite some deterioration in their physical ability, family members enabled an individual to continue valued activity, reinforcing the coherence of their sense of self rather than someone whose identity had changed as a result of the diagnosis [Citation28,Citation36]. Furthermore, by helping individuals with practical aspects of the condition such as daily planning or cooking, partners helped individuals with PD to maintain independence in the activities which mattered most [Citation35,Citation37–39]. Individuals were determined to maintain their usual activities as far as possible even when this was at conflict with doctors’ advice about expected behaviours, only adjusting their behaviour when their habitual activities were no longer working for them [Citation40]. Although negotiating the role in the family was often necessary [Citation41] focusing on the continuity of these relationships allowed an individual to maintain who they wanted to be [Citation41–43].

Support groups were one forum where an individual gained friendship which encouraged a coherent sense of self. Coherence was provided by opportunities which allowed individuals to reinforce and confirm the experiences of themselves which mattered, such as through participation in enriching activity and offering reciprocal support [Citation35,Citation42,Citation43].

In helping others find theirs, I have created a purpose for myself and the amazing thing is I found that I began to enjoy life more! It was not just a service for others; it became a pathway to regain my lost dignity and optimism, and sense of value as a person [Citation35].

Despite disruption to their sense of self as a result of the illness, individuals were able to re-establish coherence by providing support to others and maintaining purpose and valued social activity.

However, support groups were not always helpful in supporting an individual’s adjustment to the condition [Citation44,Citation45] and their helpfulness or not likely depended upon whether meeting others with PD facilitated the maintenance of their sense of self. If seeing others with the condition generated incongruence between the person’s understanding of who they were and their understanding of the self as “a person with PD,” then it was likely to impede the adjustment process. As described by one individual:

I have seen the future in the eyes, faces and activities, or inactivities, of my fellow Parkinson sufferers who are in more advanced stages of the disease than me. I can picture myself sitting paralysed in a wheelchair unable to communicate, in pain because my back is hurting, and no one knows that I need to lie down. Or unable to watch television because no one knows they have given me the wrong spectacles and I cannot tell them [Citation44]

Sub theme: acceptance

Where an individual’s pre-illness self-image was no longer congruent with PD related changes, acceptance of the diagnosis and illness limitations was required to adjust to their condition. This allowed individuals to maintain a coherent sense of self despite alterations in their identity. The diagnosis for many was perceived as an emotional force which changed their identity and challenged fundamental aspects of themselves [Citation45]. Individuals faced a major challenge of moving from being overwhelmed to acknowledging the illness as their own [Citation41]. In order to accept the disease, individuals described going through many different emotions from initial denial, through to sadness and anger, before eventually allowing themselves to be hopeful for their new future [Citation41,Citation46,Citation47]. The process culminated in a shift in how they thought about their diagnosis, from having to adjust to living with a diagnosis they did not want, to a situation in which they were able hold an optimistic outlook and feel a sense of mastery in living with PD [Citation35,Citation37,Citation39].

For many individuals, acceptance involved modifying their expectations of what they were able to do, incorporating their disease related limitations into an identity which accommodated illness changes. The metaphor “like a bird with a broken wing” highlights how participants accepted the things they were no longer able to do in order to adapt to the newfound circumstances [Citation4]. There was an ongoing tension between preserving their current sense of self and releasing aspects of the former self [Citation39,Citation48] to adjust to a self which integrated “the broken wing”. Although aspects of their self might change, participants who had adjusted were able to build on past relationships and events to maintain coherence in their sense of self, integrating the PD into an altered understanding of the self [Citation43,Citation45]. This acceptance facilitated proactive coping, such as through using mobility devices and making necessary adaptations to their activities, thus enabling continued social engagement alongside the ability to optimise care [Citation4,Citation37,Citation39,Citation45]. By continuing to adapt their activities to allow for sustained wellbeing and activity participation, individuals were able to redefine themselves in relation to their impairments and activity limitations [Citation39,Citation45,Citation49].

For individuals experiencing cognitive impairment, or indeed where an individual’s strongly held roles or self-beliefs were incongruent with PD related changes, acceptance was more challenging. In such instances, the representations an individual held of their physical and mental self-image seemed to be fundamentally incongruent with the illness identity [Citation37,Citation50]. Although this is likely to depend on individual beliefs about what acceptance of the illness might mean, it may also differ according to age or gender, where societal roles or expectations may contribute to incompatibility between sense of self and illness changes.

Indeed, some studies reported accounts of individuals who felt forced into constructing a new identity [Citation50,Citation51] or of hiding their symptoms away [Citation39]. Individuals who found acceptance more difficult often experienced poorer psychosocial adjustment [Citation37]. Consequences of not accepting the disease often meant an individual not being able to maintain their sense of self and experiencing PD as a threat to their identity.

Where individuals were required to adjust to increased dependence and progressive deterioration, fears for their future and low self-esteem were challenges which they often had to contend with [Citation48]. Loss of major roles was also a major challenge for the participants, where interviewees described having to make decisions about their ability to do things because they were no longer cognitively able [Citation37,Citation48,Citation51]. The uncertainty of PD and the daily challenges it raised meant that individuals were no longer able to pursue their previous lifestyle and contributed to frequent reminders of their PD status [Citation49,Citation50]. As one individual acknowledged:

I knew that I’d read it was long term, but I couldn’t absorb that, er and really accept it and I had a close member of family who’d been an auxiliary nurse, who knew exactly what it would lead to who didn’t tell me, but I could tell from their facial expressions when talking about Parkinson’s er that they, it, there was something more to it than just an illness that would go away [Citation4].

The phrase “more than just an illness” highlights the powerful and pervasive nature of the diagnosis, which felt to take over all aspects of their identity; in many respects, too consuming to absorb or accept into their pre-existing identity.

Theme 2: feeling in control

Feeling in control helped individuals to retain a sense of agency despite the illness limitations. Undertaking self-management of their condition was one way in which individuals gained back a sense of control while living with PD. In order to feel able to self-manage their condition, information and resources were necessary to provide individuals with the required knowledge and expertise.

Sub theme: self-management

Feeling able to self-manage care was an important component of feeling in control. Learning self-management techniques helped an individual to feel they had a greater understanding of their situation and thus strengthened feelings of being control:

…and this education as a whole has helped me to take on my illness in a more powerful way. Maybe it’s because I’m relatively newly diagnosed…for me…this education gave me hands-on tangible things to do for myself. That felt good for me [Citation46]

Feeling in control and of owning responsibility for management of symptoms were stressed as important across many of the studies [Citation4,Citation45,Citation52,Citation53]. This was often not easy to achieve, especially given the progressive nature of the condition. In PD, the adjustment process is transitory, and feeling in control is a recurring process which one has to maintain throughout the course of the illness. This is articulated in the following extract:

It is deteriorating, getting worse and worse. The most miserable thing is that I have to deal with the worsening situation, and I have to deal with it again and again… Every time when it gets worse, regarding the progressive nature of the illness, it made me feel in the middle of nowhere. But I still have to bear it… I have to bear it every time [Citation37]

In referencing the “middle of nowhere”, this participant alludes to the sense of losing control over their life with no way out, given the impossibility of gaining primary control over the progression of symptoms.

When primary control of PD is not possible given the unknown and fluctuating course of the disease, feelings of secondary control (i.e., the ability to control the psychological impact of circumstances) were important to maintain some sense of self-efficacy. Even previously mundane tasks such as maintaining the physical environment were described as valued tasks in helping to occupy individuals in a way which contributed to their feelings of self-efficacy:

Taking care of the house keeps me busy, I enjoy doing woodwork and there is always something to attend to. [Citation42]

In many of the studies, individuals with PD actively monitored their health to tailor the management of their symptoms [Citation45,Citation46]. Regarding medication, individuals made independent decisions about how and when to take prescribed and non-prescribed medications, often listening to their body to determine medication needs [Citation40,Citation43,Citation45,Citation48]. Listening to the body often resulted in confrontation with the limits of formal knowledge and the acknowledgement that the person knew best in managing their condition. Medication helped individuals to stabilise their symptoms and maintain independence [Citation37,Citation41,Citation42], allowing individuals to feel “master of [their] own fate” [Citation54]. Despite being an external way of managing physical symptoms, taking medication allowed individuals to feel they had control over their condition and gave them agency in practical aspects such as dosage, timing, and the management of side effects [Citation41].

Sub theme: information and resources

Information and resources were important for individuals to feel in control of their condition. Individuals reported how information about the medical aspects of PD were particularly useful in helping them to feel in control of their care [Citation36,Citation42,Citation47,Citation52]. Unfortunately, even in later studies, individuals still reported they often received little information from their healthcare professional or received information which was delivered without due regard for the impact which disclosure might have on the individual [Citation41,Citation51,Citation54]. Furthermore, lack of knowledge about the disease and its symptoms had forced some to conduct autonomous searches for information and try alternative solutions, to satisfy their “need to know” [Citation37,Citation41]. Limitations of a service such as having insufficient resources and lack of professionals’ time were reported as making it difficult to ask the right questions, leading to concerns remaining unanswered and decreasing agency [Citation4,Citation40]. The progressive and fluctuating course of the disease, experienced differently in every individual, could create mystery and uncertainty which may be amplified by lack of knowledge [Citation41,Citation48].

In contrast, participants who received regular contact from healthcare professionals really valued the support that was offered, describing it as sensitive to their needs and making them feel able to manage their condition [Citation46]. Sufficient knowledge of and education about the disease could facilitate anticipation of change and could help individuals to feel more in control of their condition [Citation36,Citation40,Citation42,Citation54]. This sense of agency was important in helping individuals to feel better able to overcome the barriers of PD {50]. In empowering individuals to self-manage their condition, many individuals agreed that resources from healthcare professionals helped them to feel more capable of adjusting to PD [Citation36].

It seemed that the utility of information in supporting people’s self-management efforts depended upon whether it contributed to congruence with the individual’s social role [Citation36,Citation40,Citation44]. Information which focused on symptom management could be in conflict with the needs of the individual with PD, who may have been aiming to maintain their existing social roles as far as possible. Expected behaviours about what people should do often ignored an individual’s understanding or needs, and where the benefits of new behaviours were not clearly articulated, individuals preferred to maintain existing social roles.

Theme 3: holding a positive mindset

Having a positive attitude enabled individuals to experience positive wellbeing despite the challenges raised by their condition. Social comparison-both upward (looking to others functioning better than oneself) and downward (reflecting on the worse situation of others) helped individuals to reflect on their ability to cope. A related concept, gratitude, helped individuals to value the things which they appreciated and valued in their life.

Sub theme: social comparison

The ability to make both upward and downward positive social comparisons seemed to be important in helping individuals with PD to achieve a positive mindset. Self-help support groups were one environment whereby individuals had the opportunity to make social comparisons [Citation35,Citation42,Citation44]. Members of self-help groups were able to utilize the experience of peers to make a positive downward social comparison and reflect on their relatively good fortune [Citation44,Citation46]. Downward social comparisons were reflected in statements such as “There is always someone worse off than me” [Citation46]. For many, reflecting on the worse situation of others could help to keep their own situation in perspective and facilitate emotional coping [Citation38]. Strengthening self-image through downward social comparisons allowed individuals to adjust to their own situation and was experienced regardless of their own degree of impairment [Citation46,Citation49].

Participants were also able to make positive upward social comparisons to find inspiration and optimism from well adapted peers who had experienced PD for significantly longer duration [Citation44,Citation52]. By gaining inspiration from others who were coping well, broadening knowledge of PD management or heightening gratitude of their current functioning, social comparison helped individuals to maintain positivity [Citation52]. This positivity translated into individuals perceiving their future as possible [Citation35,Citation52], with individuals realising that illness changes could be managed observing the positive and encouraging outcomes of peers [Citation52].

Sub theme: gratitude

In many of the studies, participants described how having gratitude helped them to maintain a positive mindset and facilitated their adjustment to the PD [Citation39,Citation53]. Having gratitude for present functioning facilitated the ability to place high value on the activities participants were still able to do, which translated into individuals feeling less burdened by their activity limitations [Citation50,Citation53]. In the early stages of disease progression, individuals could be grateful that their body in some respects functioned “normally,” and thus reflect upon how they were still themselves despite the PD [Citation28,Citation48,Citation49]. Even experiences of tiredness and sweating when exercising or being active were considered positive, and were longed for, since they meant expressions of a healthy body [Citation49]. It also helped individuals to remain active in society, which they described as contributing to feelings of being useful and maintaining high levels of self-worth [Citation28,Citation43].

Gratitude for friends and family was also described in many individuals’ accounts. For instance, kinship and sense of belonging were important sources of wellbeing and helped an individual with PD to reflect on the valued relationships they had despite the changes brought on by the diagnosis [Citation43,Citation46]. As one individual reflected on how their relationship with their partner had changed since diagnosis

I mean we sort of found out that our feelings for each other had multiplied. We’ve got a lot more time for each other. [Citation4]

By focusing on the relationships which they valued, individuals were able to relinquish relationships which were no longer helpful [Citation4,Citation28,Citation46,Citation48]. This renewed sense of focus brought gratitude for valued connections and provided companionship [Citation4,Citation52], hope [Citation35,Citation46,Citation50,Citation55] and feelings of closeness [Citation45].

For some individuals, the sense that they should be grateful for their close relationships felt to be more of an obligatory process, which involved the painful recognition of their own dependence on their partner, alongside a sadness that both the PD and also family members limited what they felt able to do. As one individual describedif I didn’t have him to answer the phone and organise, I’d have never have been able to re-organise this morning…he just liaises, he even buys the birthday cards now, we, which was everything I used to do, in fact he’s taken over me diary, I feel taken over [Citation4].

This extract describes the difficulty which comes with having gratitude for the things that family members assist with, which results in a lost sense of purpose and also perhaps pleasure.

Gratitude for the present seemed to be a way in which individuals were able to live life to the full despite the challenges faced living with PD. Many of the individuals living with PD described the importance of acknowledging that their future was likely to be associated with symptom deterioration and reduced life expectancy, and the need therefore to live in the present with renewed energy and determination [Citation43–45]. This renewed energy led participants to take up desired opportunities in the present and not the future, thereby leading to the sense that they were embracing the present [Citation4,Citation43,Citation45]. By living for each day, their present became more manageable and they were able to be grateful for the things they could still achieve. For some individuals, gratitude and positive thinking felt to be part of their personality and a natural process, whereas for others it was more of a conscious strategy or through a sense of obligation [Citation42]. Many individuals experienced negative reactions to the initial diagnosis [Citation37,Citation51], but gratitude helped an individual to navigate their path to finding an optimistic perspective [Citation35].

Discussion

According to the findings of a recent review [Citation23], individuals are required to make repeated behavioural and psychological adjustments when living with PD in order to maintain a stable relationship with their self-concept and their environment. This often involves external adjustments which aim to maintain stability such as medical treatment or social support, but also involves cognitive re-evaluation of the self-concept when physical or cognitive limitations mean that restoring/maintaining stability is unattainable. The present review supports the findings about the importance of an individual maintaining their sense of self, either through social support or external adjustments which allow for continued engagement with valued activities, or through accepting their limitations in order to re-evaluate their self-concept to include the PD. Nevertheless, the present review extends these findings, articulating in more detail how an individual is able to achieve stability in their sense of self-through the processes of feeling in control and holding a positive mindset. A key finding from the present review is the way in which individuals experienced PD as a threat to their self-identity, thus maintaining a coherent sense of self was a key adaptive task in adjusting to their condition. This is in line with the Moss-Morris model of adjustment [Citation21] whereby critical events in an illness experience (such as the diagnosis or initial symptoms), alongside on-going illness stressors, disrupt emotional equilibrium and quality of life. The goal of adjustment is to return to equilibrium, thereby reducing the impact of the illness on everyday life. However, the present review describes how maintaining a coherent sense of self did not just involve a restoration of an individual’s previous sense of self, as assumed in the aforementioned model, but also involved altering their sense of self to integrate the PD. This suggests that rather than restore equilibrium or return to previous assumptions, individuals living with a progressive condition need to alter their equilibrium to accommodate illness changes. Williams [Citation55] describes how, when confronted with a chronic illness, individuals need to reconstruct their identity narrative in order to understand the illness in terms of their past experiences and to reaffirm their sense of self as one of purpose and meaning. For individuals living with chronic fatigue syndrome, reconstructing an identity narrative has been shown to be a powerful way in which individuals make sense of their illness and in providing opportunities to connect with other individuals with similar illness narratives [Citation56]. In placing the experience of chronic illness within the framework of their life history, an individual can find meaning to the events which have disrupted and changed their identity [Citation55] and re-establish their relationship between their self, the world and their body [Citation57]. The ability of an individual to reconstruct a narrative which integrates their illness experience allows an individual to maintain a coherent sense of self. In developing a sense of self which not only incorporates but is enriched by their illness experience, individuals may be better able to adjust to their condition.

In order to manage the threat to health and maintain a coherent sense of self, participants in the reviewed studies described the importance of gaining control over their condition. According to the Common Sense Model of Self-Regulation [Citation58], a widely used framework exploring how individuals navigate affective responses to health threat [Citation58], disruption to an individual’s normative sense of self is likely to interact with illness prototypes and activate the representation of threat to health. In the reviewed studies, disruptions to an individual’s usual way of life were often perceived prior to the diagnosis of PD, and the threat of illness often prompted them to seek guidance from a clinician. Seeking professional support and taking action towards understanding their symptoms helped people to gain a sense of control not only over initial symptoms but also the management of their condition. Having a sense of control has consistently been linked to good psychological and physical adjustment to chronic illness [59]. Gaining control over symptoms through self-management (primary control) allowed individuals to feel more in control of their life and better able to adapt to disease related limitations (secondary control). This felt important given the uncontrollable nature of disease progression. Both increased perceptions of primary control [Citation60,Citation61] and secondary control [Citation62] have previously been associated with greater wellbeing and psychological adjustment in individuals with PD. Even if control of disease may not be possible, global life control and feelings of self-efficacy rather than control over the disease per se can also be important [Citation63]. Indeed, in one study investigating perceptions of cause and control in individuals with PD [Citation64], knowledge of aetiology and underlying physiological processes of PD did not contribute to a perception of control, although knowledge supporting management techniques was perceived as helpful. Whether knowledge of the disease contributes to a perception of control is likely to depend upon the individual and the meaning which potential knowledge has for them; including whether it is congruent with their own understanding. According to the Common-Sense Model, clarifying the patient’s illness and treatment representations and ensuring action plans are congruent with these representations is likely to facilitate treatment adherence [Citation65]. Unfortunately, given the limited time clinicians often having with individuals during consultations, conversations are often limited to symptoms and treatment effects [Citation65]. However, exploring the personal factors which might influence the adoption of self-management practices is likely to facilitate treatment adherence. In a study which explored the role which the content of clinical communications may have on treatment adherence, when patients perceived the visit to have a common sense rather than medical purpose (i.e., focusing on treatment monitoring and the individual’s ability to manage their condition, as opposed to patient feelings of treatment effects), visits which were deemed to have a common sense purpose resulted in greater treatment adherence and better management of their condition [Citation66]. Practitioners who give time to explore patient beliefs about when and how to do the treatment and their expectations of own self-efficacy may be more effective at empowering individual self-management because they set the stage for action and evaluation of treatment efficacy [Citation67]. This highlights the importance of ensuring that information and knowledge related to self-management is tailored to an individual’s understanding and experience of the disease.

In line with the Moss-Morris model [Citation21], cognitive factors including gratitude and social comparison were important components for individuals living with PD to hold a positive mindset despite continuing deterioration. In comparing themselves with others and experiencing gratitude for the things one appreciated in life, individuals seemed able to come to terms with their condition. For many, reaching a place of optimism involved a series of emotional stages first including shock, denial and anger [Citation35], situating it as a similar process to that of bereavement. This process of adaptation may be a healthy way in which an individual grieves for the person they once were. In making space for and allowing oneself to experience and share negative emotional experiences with others, individuals with chronic illness may be better able to self-regulate emotions [Citation68]. The ability to hold a positive mindset alongside co-existence of positive and negative emotions is likely to facilitate an optimistic outlook in the face of adversity and adjustment to the challenges imposed by their condition [Citation69].

Clinical implications

In order to improve access to support and provide individualised care, healthcare systems need to be offering a range of interventions which are cost-effective, and high intensity input is not always preferable or desirable. Consequently, the adoption of self-management policies needs to be prioritised in order to facilitate an individual’s adjustment to their condition [Citation70]. Effective approaches to supporting this adjustment requires (1) tailored information which meets the individual’s needs (2) partnership decision making and care planning, (3) support with the social and emotional impact of the condition and (4) education and motivation in self-management [Citation71]. All of these factors emerged from the findings in the present synthesis: decision making and planning which treats the individual as a true partner in their care supports the maintenance of their sense of self; education and information on self-management supports individuals to feel in control and support with the social and emotional impact of the condition helps the individual to achieve a positive mindset. How each of these can be effectively achieved within current models of healthcare delivery met will be explored in turn in the following discussion.

Tailored information which meets the individual’s needs is essential to supporting an individual’s self-management of their condition and key to facilitating the participants’ perceptions of control. Consistency in the information provided by healthcare professionals is important to minimise distress related to confusion about their symptoms and to heighten individual’s self-efficacy in their ability to manage their condition. Several of the studies highlighted incidences where individuals had felt information had been delivered insensitively or without due regard to an individual’s preference in the timing or setting for the delivery. Individuals described being informed of their diagnosis in non-private settings or in an abrupt and impersonal manner [Citation51]. This may reflect the complexity of providing the right information at the right time [Citation72] or reflect clinician’s guilt about their inability to provide a medical treatment or cure, thus affecting their consideration of appropriate manner and timing of delivery [Citation73]. Nonetheless it is concerning, given the importance of individuals feeling empowered through professional support to self-manage their care. Where professionals deliver recommendations without recourse to an individual’s practical understandings or idiosyncratic needs, individuals may feel forced into adopting habits they are not ready to adopt and available solutions can be unsettling [Citation39]. Thus, healthcare professionals need to ensure that the provision of information is tailored to the needs of the individual so that they feel able to make good decisions about their current and future care [Citation51].

Partnership care planning and decision making is also key to individual adjustment, and this requires an integrated approach. An integrated approach including the individual with PD in any decision making is considered the best way to manage PD [Citation74]. This integrated approach should recognise the importance of the availability of supportive others in supporting their self-management approach [75]. Although not fully recognised by current models of adjustment, the role that other people have in encouraging an individual in their self-management and in mediating beliefs about self-efficacy should be more readily acknowledged by healthcare professionals. The self-management of illness is often perceived to be an individual phenomenon yet it is arguably a collective process, taking place within a social context [Citation76]. People who readily engage in self-management practices are often not able to meet their roles and responsibilities within the family, because of the required routines and practises required in most self-management approaches. Individuals are reluctant to involve family in illness self-management because of the way self-management has been framed in healthcare discourse as an individual process, despite the fact that social support and collective adaptation provide environments which promote illness management [Citation77]. This is likely to depend upon cultural perceptions about the importance of family and social networks in supporting adjustment to disease [75] and has been shown to be an important aspect in experiencing success with the illness, defined as the ability to hold on to family lifestyles and usual routines [Citation28]. Early intervention incorporating psycho-education about the management of symptoms, which recognises the social context in which the individual experiences their condition, is important to facilitating adjustment to PD.

Supporting individuals with the emotional and social impact of the condition can be identified in the need expressed by participants to focus their energies on embracing a present filled with purpose rather than a future focused on deterioration. As such, mindfulness-based approaches may be an effective intervention in facilitating individual adjustment to the condition. Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) typically takes places over 8 weeks and teaches participants to become more aware of their present thoughts and feelings. It also encourages a more detached relationship with these thoughts and feelings, rather than viewing them as accurate representations of the self or reality [78]. In developing a detached perspective to difficult thoughts and feelings which may arise from living with PD, an individual may be less likely to experience the difficult thoughts as a reflection of their inability to cope and more able to fully engage with their present. Preliminary evidence suggests the experience of mindfulness can help individuals to access inner resources and reaffirm their existing coping ability, enabling them to confront previously avoided social situations and to have more confidence in their ability to self-manage situations which they may have previously avoided [Citation79]. Facilitating this self-management and encouraging individuals to fully engage with their present experience may provide a protective mindset against PD related challenges and an acceptance of the feelings or emotions of having PD. In encouraging individuals to focus on their present and enhancing existing coping ability, MBCT may help individuals to adjust to their condition.

The need to feel motivated and supported in self-management and the acceptance of a readjusted state of health was reflected across the individual studies and healthcare professionals should support this acceptance where possible. Interventions based on acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) [Citation80] may help individuals to develop acceptance to the changes which PD brings. Acceptance is a stance an individual adopts rather than a process of coping and enables an individual to pursue a life in accordance with their values, despite the limitations imposed by their illness [Citation81]. ACT encourages this accepting stance through techniques such as cognitive defusion, which help an individual to detach from difficult thoughts and in doing so develop more flexible ways of responding to challenging situations [Citation80]. In developing more flexible responses, individuals are supported to lead a meaningful life despite the continual challenges which PD presents. Although there is little evidence for the efficacy of ACT in PD populations, there is evidence that ACT may be effective in conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS), where greater acceptance of the condition (according to ACT principles) was found to relate to better adjustment [Citation82]. Furthermore, a recent intervention utilizing a trans-diagnostic approach for individuals with chronic illness has highlighted the effectiveness of ACT principles in reducing psychological distress, reducing physical limitations, and increasing valued behaviour [Citation83]. This effect was seen despite the individuals’ evaluation of their health changes remaining the same. It is important that the effectiveness of the intervention was independent of the evaluation of health status, given that the progressive nature of PD means that an individual’s health status is likely to continually deteriorate. The efficacy of ACT based interventions in other chronic illnesses highlights its potential efficacy in supporting individuals with PD to adjust to their condition. Nevertheless, this approach should recognise that the clinical management of PD needs to be different to that utilised in other chronic conditions. Due to the progressive nature of the condition, at some point acceptance of deterioration will become incongruent with beliefs about the self that the individual strongly identifies with. At this point, clinician encouragement to focus on acceptance of the illness and self-management is likely to neglect fundamental aspects of the individual’s experience of the condition, the loss of self. Once external management is no longer compatible with internal belief systems of the individual, a more nuanced approach targeting the individual’s feelings of loss and supporting them through the bereavement process is likely to be required.

Limitations and future research

Conducting a meta-ethnography largely ensures that the experiences of the participants in the individual studies are preserved [Citation32]. Nevertheless, the synthesizing of multiple studies meant that some of the individual experiences may have been lost. For instance, nuances in adjustment which may have reflected differences in disease duration, extent of symptoms and disease severity of individual participants were not considered in depth. Furthermore, the majority of the studies included individuals with PD of either low or medium severity. Although some studies included participants with more severe symptoms, it is likely that these participants represent those individuals who are functioning relatively well despite the severity of their condition. Although recruiting individuals with more severe PD is challenging, future research should aim to explore how adjustment might differ in the more advanced stages of the disease. An additional avenue for future research would be to study in depth the experience of individuals with PD who additionally experience cognitive impairment. Although not discussed in detail in the present synthesis given that few of the included studies involved individuals with cognitive impairment, it is nevertheless an important aspect to consider. It may be expected that cognitive changes would limit an individual’s ability to flexibly adapt their sense of self and to adopt self-management skills, with consequent implications on an individual’s ability to adjust to their condition.

The majority of the included studied were conducted in Western countries and consequently, future research should explore the experiences of adjustment for individuals living with PD in non-Western countries. Culture is arguably the ‘inherited lens’ through which we understand the world around us and how we navigate our experiences within it [Citation76]; it is inevitable therefore that differing cultures will have different understandings of both health and illness. This review has highlighted the importance of an individual’s representation of illness in the process of adjustment to PD, suggesting that adjustment might also differ across different cultural contexts. The generalizability of the research to Eastern populations is therefore limited, although the consistency of findings across epistemological orientations, methodological approaches, countries and healthcare settings suggests some transferability of the results. Nevertheless, a primary aim of the meta-ethnographic approach is to interpret findings within the context of the initial study; as many of the studies failed to provide sufficient contextual detail regarding socioeconomic status, ethnicity, cognitive impairment or living situation of the participants, the contribution of the meta-ethnography is itself limited. Furthermore, all of the studies used a cross sectional design. In contrast, longitudinal studies provide valuable insights on the temporality of the adjustment process and how it might differ according to the trajectory of recovery. Given 21 studies were included in the review spanning differing healthcare contexts and there was considerable overlap in the findings, it is likely that we were able to achieve data saturation. Nevertheless, future research should explore how adjustment differs according to ethnicity, socioeconomic status and disease severity of participants.

The studies were of variable quality, as determined according to the CASP checklist, and this may be a limitation to the findings of the review. Indeed, few studies explicitly commented on issues surrounding reflexivity, failing to fully account for any relationship between the researcher and the participants, or their own influence on the data. This raises questions regarding the validity of the research. [Citation84]. All the authors have a clinical psychology background, with knowledge of neurodegenerative health literature, which inevitably provided a particular lens through which these findings were interpreted. The synthesis was conducted primarily by the first author, who met regularly with the second and third authors, to ensure the themes were credible and grounded in the data.

Conclusion

This review used a meta-synthesis approach to examine individual adjustment processes, with the research question “how do individuals adjust to living with Parkinson’s disease?” Findings from the review indicate the need for individuals to maintain a stable sense of self and feel in control, despite illness changes and on-going deteriorating. Having a positive mindset was also important in helping individuals to experience positive wellbeing. Understanding how an individual adapts to living with a chronic illness is important not only to better understand the full implications of the condition but also so we are better able to offer early intervention for individuals who are finding adjustment difficult. Supporting individuals to self-manage their condition is not only an approach which empowers individuals and their families with the ability to cope in the face of illness, it may also maximise individual wellbeing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, et al. The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Movement Disord. 2014;29(13):1583–1590.

- Montel S. Coping and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15:139.

- Khoo TK, Yarnall AJ, Duncan GW, et al. The spectrum of nonmotor symptoms in early Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2013;80(3):276–281.

- Smith L, Shaw J. Learning to live with Parkinson’s disease in the family unit: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of well-being. Med Health Care Philos. 2017;20(1):13–21.

- Reijnders JS, Ehrt U, Weber WE, et al. A systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(2):183–189.

- Nègre‐Pagès L, Grandjean H, Lapeyre‐Mestre M, et al. Anxious and depressive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: the French cross‐sectional DoPaMiP study. Mov Disord. 2010;25(2):157–166.

- Schneider F, Althaus A, Backes V, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258(S5):55–59.

- Wint DP, Okun MS, Fernandez HH. Psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17(3):127–136.8.

- Starkstein S, Merello M, Jorge R, et al. The syndromal validity and nosological position of apathy in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24(8):1211–1216.

- Kirsch-Darrow L, Fernandez HH, Fernandez HF, et al. Dissociating apathy and depression in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2006;67(1):33–38.

- Crispino P, Gino M, Barbagelata E, et al. Gender differences and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):19.

- Van Den Eeden S, Tanner C, Bernstein A, et al. Incidence of Parkinson’s disease: variation by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(11):1015–1022.

- Rana A, Qureshi AR, Fareez F, et al. Impact of ethnicity on mood disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Neurosci. 2016;126(8):734–738.

- Schrag A, Hovris A, Morley D, et al. Young- versus older-onset Parkinson’s disease: impact of disease and psychosocial consequences ’. Mov Disord. 2003;18(11):1250–1256.

- Garlovsky JK, Overton PG, Simpson J. Psychological predictors of anxiety and depression in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. J Clin Psychol. 2016;72(10):979–998.

- Soh S-E, Morris ME, McGinley JL. Determinants of health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17(1):1–9.

- Van Uem J, Marinus J, Canning C, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease-a systematic review based on the ICF model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;61:26–34.

- Sharpe L, Curran L. Understanding the process of adjustment to illness. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(5):1153–1166.

- Hammond LD, Hirst-Winthrop S. Proposal of an integrative model of adjustment to chronic conditions: an understanding of the process of psychosocial adjustment to living with type 2 diabetes. J Health Psychol. 2018;23(8):1063–1107.

- Stanton AL, Revenson TA, Tennen H. Health psychology: psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:565–592.

- Moss-Morris R. Adjusting to chronic illness: time for a unified theory. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(4):681–686.

- Soundy A, Stubbs B, Roskell C. The experience of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:613592.

- Rutten S, van den Heuvel OA, de Kruif A, et al. The subjective experience of living with Parkinson’s disease: a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(1):139–151.

- Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, et al. 2016. Guidance on choosing qualitative evidence synthesis methods for use in health technology assessments of complex interventions [Online]. Available from: http://www.integrate-hta.eu/downloads/.

- Noblit G, Hare RD. 1988. Meta-ethnography synthesizing qualitative studies (qualitative research methods; v. 11). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

- Pathak V, Jena B, Kalra S. Qualitative research. Perspect Clin Res. 2013;4(3):192–192.

- Kang M, Ellis‐Hill C. How do people live life successfully with Parkinson’s disease? J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(15–16):2314–2322.

- Kennedy-Behr A, Hatchett M. Wellbeing and engagement in occupation for people with Parkinson’s disease. British J Occup Ther. 2017;80(12):745–751.

- Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, et al. ‘Trying to pin down jelly’ - exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):46.

- Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320(7226):50–52.

- Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, et al. Using Meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(4):209–215.

- Schütz A. 1962. Collected papers 1. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

- Gardenhire J, Mullet N, Fife S. Living with Parkinson’s: the process of finding optimism. Qual Health Res. 2019;29(12):1781–1793.

- Navarta‐Sánchez MV, Caparrós N, Riverol Fernández M, et al. Core elements to understand and improve coping with Parkinson’s disease in individuals with PDs and family carers: a focus group study. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73:2609–2621.

- Kwok JYY, Lee JJ, Auyeung M, et al. Letting nature take its course: A qualitative exploration of the illness and adjustment experiences of Hong Kong Chinese people with Parkinson’s disease. Health Soc Care Commun. 2020;28(6):2343.

- Uebelacker LA, Epstein-Lubow G, Lewis T, et al. A survey of Parkinson’s disease patients: most bothersome symptoms and coping preferences. J Parkinsons Dis. 2014;4(4):717–723.

- Lutz SG, Holmes JD, Rudman DL, et al. Understanding Parkinson’s through visual narratives: “I’m not mrs. Parkinson’s”. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;81(2):90–100.

- Lubi K. The adaptation of everyday practices in the adoption of chronic illness. Health (London). 2019;23(3):325–343.

- Habermann B. Day-to-day demands of Parkinson’s disease. West J Nurs Res. 1996;18:387–413.

- Sperens M, Hamberg K, Hariz G. Challenges and strategies among women and men with Parkinson’s disease: striving toward joie de vivre in daily life. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;81(12):700–708.

- Williams S, Keady J. ‘A stony road… a 19 year journey’: ‘bridging’ through late-stage Parkinson’s disease. J Res Nurs. 2008;13(5):373–388.

- Charlton G, Barrow C. Coping and self-help group membership in Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory qualitative study. Health Soc Care Commun. 2002;10(6):472–478.

- Vann-Ward T, Morse J, Charmaz K. Preserving self: theorizing the social and psychological processes of living with Parkinson disease. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(7):964–982.

- Hellqvist C, Dizdar N, Hagell P, et al. Improving self-management for persons with Parkinson’s disease through education focusing on management of daily life: patients’ and relatives’ experience of the Swedish National Parkinson School. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(19–20):3719–3728.

- Nazzal M, Khalil H. Living with Parkinson’s disease: a Jordanian perspective. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24(1):74–82.

- Stanley-Hermanns M, Engebretson J. Sailing the stormy seas: the illness experience of persons with Parkinson’s disease. Qual Rep. 2010;15(2):340–369.

- Eriksson B, Arne M, Ahlgren C. Keep moving to retain the healthy self: the meaning of physical exercise in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(26):2237–2244.

- Lawson RA, Collerton D, Taylor J-P, et al. Coping with cognitive impairment in people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers: a qualitative study. Parkinsons Dis. 2018;2018:1362053–1362010.

- Shaw ST, Vivekananda-Schmidt P. Challenges to ethically managing Parkinson disease: an interview study of patient perspectives. J Patient Exp. 2017;4(4):191–196.

- Soundy A, Collett J, Lawrie S, et al. A qualitative study on the impact of first steps-a peer-led educational intervention for people newly diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Behav Sci. 2019;9(10) 107.

- Den Oudsten BL, Lucas-Carrasco R, Green AM, et al. Perceptions of persons with Parkinson’s disease, family and professionals on quality of life: an international focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(25–26):2490–2508.

- Plouvier A, Olde Hartman T, Van Litsenburg A, et al. Being in control of Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative study of community-dwelling patients’ coping with changes in care. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):138–145.

- Williams G. The genesis of chronic illness: narrative re-construction. Sociol Health Illn. 1984;6(2):175–200.

- Bulow P. Sharing experiences of contested illness by storytelling. Discourse Soc. 2004;159(1):33–53.

- Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn. 1982;4(2):167–182.

- Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Kitas GD. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness: How can we use it to understand and respond to our patients’ needs? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(6):904–906.

- Taylor S, Kemeny M, Reed G, et al. Psychological resources, positive illusions, and health. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):99–109.

- Pape T, Kim J, Weiner B. The shaping of individual meanings assigned to assistive technology: a review of personal factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(1–3):5–20.

- Krakow K, Haltenhof H, Bühler K. Coping with Parkinson’s disease and refractory epilepsy. A comparative study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(8):503–508.

- McQuillen AD, Licht MH, Licht BG. Contributions of disease severity and perceptions of primary and secondary control to the prediction of psychosocial adjustment to Parkinson’s disease. Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):504–512s.

- Eccles F, Simpson J. A review of the demographic, clinical and psychosocial correlates of perceived control in three chronic motor illnesses. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(13–14):1065–1088.

- Eccles F, Murray C, Simpson J. Perceptions of cause and control in people with Parkinson’s disease. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(15–16):1409–1420.

- Hulbert SM, Goodwin VA. ‘Mind the gap’ - a scoping review of long term, physical, self-management in Parkinson’s. Physiotherapy. 2020;107:88–99.

- Phillips LA, Leventhal H, Leventhal EA. Physicians’ communication of the common-sense self-regulation model results in greater reported adherence than physicians’ use of interpersonal skills. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17(2):244–257.

- Omer ZB, Hwang ES, Esserman LJ, et al. Impact of ductal carcinoma in situ terminology on patient treatment preferences. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(19):1830–1831.

- de Ridder D, Geenen R, Kuijer R, et al. Psychological adjustment to long-term disease. The Lancet. 2008;372(9634):246–255.

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004;15(1):1–18.

- Lawton J, Ahmad N, Hanna L, et al. ‘We should change ourselves, but we can’t’: accounts of food and eating practices amongst British Pakistanis and Indians with type 2 diabetes. Ethn Health. 2008;13(4):305–319.

- The Health foundation. Helping people to help themselves. A review of the evidence considering whether it is worthwhile to support self-management. London: The Health Foundation; 2021. Available from: Evidence: Helping people help themselves | The Health Foundation.

- Eijk M, Faber M, Post B, et al. Capturing patients’ experiences to change Parkinson’s disease care delivery: a multicenter study. J Neurol. 2015;262(11):2528–2538.

- Schrag A, Modi S, Hotham S, et al. Patient experiences of receiving a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2018;265(5):1151–1157.

- Post B, van der Eijk M, Munneke M, et al. Multidisciplinary care for Parkinson’s disease: not if, but how!. Pract Neurol. 2011;11(2):58–61.

- Vassilev I, Rogers A, Kennedy A, et al. The influence of social networks on self-management support: a metasynthesis. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:719.

- Helman C. 2000. Culture, health and illness. 4th ed. London: Hodder Arnold.

- Berkman LF. Social support, social networks, social cohesion and health. Soc Work Health Care. 2000;31(2):3–14.

- Batink T, Peeters F, Geschwind N, et al. How does MBCT for depression work? Studying cognitive and affective mediation pathways. PloS One. 2013;8(8):e72778.

- Fitzpatrick L, Simpson J, Smith A. A qualitative analysis of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in Parkinson’s disease. Psychol Psychother. 2010;83(Pt 2):179–192.

- Hayes S, Kirk S. 2011. A practical guide to acceptance and commitment therapy. New York; London: Springer