Abstract

Purpose

Patient empowerment may be particularly important in children and young people (CYP) with CF, due to high treatment burden and limited peer support opportunities. This review aimed to meta-synthesize the qualitative literature pertaining to empowerment in CYP with CF.

Materials and methods

This work was guided by the ENTREQ framework, with a search strategy based on the SPIDER framework. A systematic search of PsycInfo, Medline, CINAHL and ASSIA databases was conducted. Identified studies were quality assessed and data analysed using thematic synthesis. PROSPERO registration: CRD42019154014.

Results

Seventeen studies met inclusion criteria, though none explicitly explored empowerment. Thematic synthesis identified six analytic themes: relational support, information and understanding and feeling heard and respected appeared to facilitate empowerment, while prejudices and assumptions were identified as potential barriers. Mastery and competence and Navigating being different appeared to be components of empowerment.

Conclusions

The findings provide an initial understanding of patient empowerment in CYP with CF. Potential clinical implications include the need for more CYP-friendly information, more shared decision making and more opportunities to experience mastery. The need for further research is highlighted, particularly relating to developmental influences and factors unique to CF, which are not adequately addressed in existing patient empowerment models.

Empowerment in children and young people with cystic fibrosis can be facilitated by supportive and respectful relationships with family, friends and clinical teams, that enable them to feel heard and understood.

It can be further supported by providing developmentally appropriate information and opportunities for children and young people to experience mastery and competency in typical childhood activities.

Prejudices and assumptions about the capabilities of children and young people with CF, even when based in good intentions, can act as a barrier to empowerment.

Empowerment can shape (and be shaped by) the way the children and young people navigate differences associated with living with CF.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

The concept of empowerment has been used in a wide range of contexts, including community work, education, health and social care [Citation1]. Empowering patients with long term conditions is essential for future engagement and has potential to impact significantly on health outcomes [Citation2,Citation3]. The World Health Organisation considers patient empowerment to be a process whereby patients acquire the information and skills required to perform health care tasks in a context that is culturally aware and in which patients are encouraged to participate [Citation4]. The concept of self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to have influence and control over their life [Citation5], is closely related to patient empowerment, as people and populations who believe they have influence and control are more likely to attempt new behaviours [Citation6]. It is argued that empowerment enables self-management and is a consequence of achieving self-efficacy [Citation7]. Experiences of empowerment are thought to be highly personal and context dependent [Citation8] and empowered patients may or may not choose to exercise their power.

The potential value of patient empowerment can be understood through reference to self-determination theory [Citation9]. According to this, people have intrinsic needs for competence, autonomy and relatedness, and meeting these can support better mental wellbeing and increased self-motivation [Citation9]. Thus, empowering patients to feel more competent and autonomous in relation to their own condition(s) and their management, and empowering them to feel more connected with others, should both support their mental wellbeing and their motivation to manage their condition and engage fully with life more generally.

While much of the patient empowerment literature has focused on adults with long term conditions, there is growing interest in child and young people (CYP) patient empowerment [Citation10]. However, most existing research has attempted to map understandings of adult patient empowerment onto CYP. This may overlook potential complexities of patient empowerment in CYP relating to developmental factors and systemic influences including parents, teachers and peers.

One condition for which CYP patient empowerment may be particularly relevant is Cystic Fibrosis (CF). CF is a multisystemic condition with a high treatment burden [Citation11]. Approximately one in every 2,500 babies in the UK is born with CF [Citation12]. Fifty years ago it would be unlikely for a child with CF to live to their 10th birthday [Citation13]. With universal screening, earlier diagnosis, new understandings and treatments, life expectancy has increased dramatically with over half of CF patients living beyond the age of 47 [Citation12]. Following discovery of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene in 1989, research intensified [Citation14,Citation15]. Precision medications known as CFTR modulators have been developed to tackle the more common underlying causes of CF [Citation14]. In the UK, Orkambi and Symkevi were made available through the NHS in late 2019 [Citation16], while Kaftrio received its European licence in 2020 [Citation16]. However, treatments for those with rarer CFTR mutations are still in development [Citation14,Citation16].

This combination of a significant treatment burden, rapid changes in life expectancy, and the inability of CYP with CF to access in person peer support due to cross-infection risk [Citation12], means patient empowerment is likely to be particularly important in CYP with CF. Therefore, there is value in understanding the nature of patient empowerment, and its facilitator and barriers, in this group. Furthermore, given the complexities of empowerment in CYP with CF and the above-mentioned limitations of applying models of adult empowerment to CYP, there is value in developing an understanding that is grounded in CYP with CF's experiences of empowerment. Qualitative research is arguably best suited to exploring people’s lived experiences of such complex phenomena [Citation17], and the qualitative literature on this topic has yet to be reviewed.

Therefore, the current review aimed to conduct a meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature that elucidates experiences of CYP with CF in relation to components of empowerment and its facilitators and barriers. (Originally, the aim was limited to examining facilitators and barriers, but through the process of meta synthesis, it became clear that there was substantial overlap between components of empowerment and its facilitators and barriers. Hence the aim was revised.) Drawing on the approach taken in previous reviews (e.g., 18), for the purpose of this review, patient empowerment was defined as both a state (i.e., a sense of having mastery or being in control) and a process, whereby people build motivation, skills and knowledge in order to take ownership of their situation [Citation18–20]. Furthermore, included studies had to describe at least one of Jorgensen et al.'s [Citation18] indicators that empowerment is the phenomenon being described; namely: feeling in control, having mastery, being in charge, having influence, having agency, or having autonomy.

Method

Meta-synthesis refers to systematic approaches to reviewing qualitative research. The current review was guided by the ENTREQ (enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research) framework [Citation21]. Several methods exist for conducting meta-synthesis [Citation22]. Thematic synthesis [Citation23] was selected as it is a method developed to address questions about people’s perspectives and experiences, and consisting of a clear set of steps:

Preparatory phase – searching the literature; study selection and assessing the quality of the papers; extracting data from the selected literature.

Thematic synthesis: (a) initial coding of text; (b) developing descriptive categories; (c) generating analytical themes.

The review adopted a critical realist stance, assuming that whilst an objective reality exists, it can only be made sense of and described through the lenses of language and social context [Citation24]. To promote rigour, a bracketing interview was undertaken (see online Supplementary Material) to consider how the lead researcher’s prior experiences, biases and assumptions may impact on the thematic synthesis. The NVivo 12 software package was used to maintain a clear audit trail of the development of descriptive and analytical themes. The review was pre-registered on PROSPERO (registration no. CRD42019154014).

Search strategy

The search strategy was guided by the SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type) framework [Citation25]. Two domains were identified to combine within the search:

Sample: children and young people with cystic fibrosis

Phenomenon of interest: patient empowerment

In line with Cochrane guidance [Citation11], terms for “children and young people” were not used to limit the search, in order to maximise relevant results. Similarly, a decision was made not to include terms for ‘qualitative research’ as there are numerous qualitative methods that may be described by authors in a multitude of ways [Citation26]. Search terms (see online Supplementary Material) were generated from existing research and theoretical literature relating to patient empowerment [Citation8,Citation18,Citation27,Citation28]. Various combinations of concept heading and search terms were trialled before settling on a broad search strategy. PsycInfo, Medline, CINAHL and ASSIA databases were selected for their relevance to the field and to encompass relevant disciplines; i.e., psychology, nursing, medicine and social work. Databases were searched from inception to September 2020.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included where: (a) participants were CYP with CF explicitly under the care of paediatric CF services; (b) the participants’ perspectives were explored; (c) a qualitative research design was used; (d) the study was published in a peer reviewed journal, available in English and; (e) the findings included at least one indicator that experiences of empowerment were being described, namely at least one of feeling in control, having mastery, being in charge, having influence, having agency, and having autonomy [Citation7]. Studies that reported the perspectives of other family members, in addition to the perspectives of CYP with CF, were included, but only if the findings stemming from the CYP could be disaggregated from the other participants' data. Only the former were included and coded.

Study selection

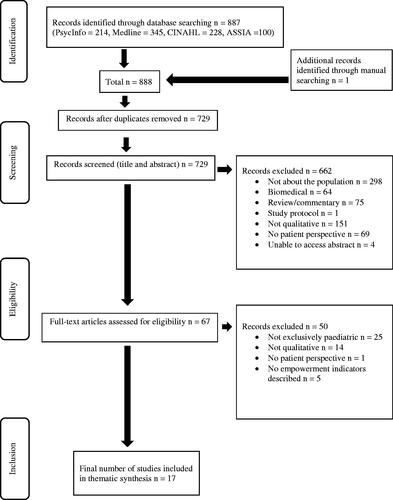

Screening was conducted by the first author. The second author checked a random 10% of all titles and abstracts, and 25% of articles through to the full text review stage. Agreement levels were 79 and 77%, respectively. Cases of disagreement were resolved through discussion. The study selection process is shown in .

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed by the lead author using a tool for appraising qualitative research developed by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [CASP] [Citation29] and the criteria for assessing research conducted with children used by Thomas et al. [Citation30]. 29% (5/17) of the included studies were also quality assessed by the second author. The level of agreement was 86%. Most of the disagreement centred around whether lack of information about researcher reflexivity should be coded as “criteria not met” or “uncertain.” Following discussion, it was agreed that “uncertain” was the most appropriate quality rating for such cases. As there are no widely accepted methods for excluding qualitative studies from reviews on the basis of quality, sensitivity analysis was employed [Citation23]. In this approach, the possible impact of study quality on the reviews’ conclusions are considered after the thematic synthesis, by examining the relative contribution of each study to final themes and recommendations.

Meta-synthesis process

The meta-synthesis followed the steps outlined by Thomas and Harden [Citation23], as follows.

Extracting data from the selected articles

The characteristics of the included studies were entered into a template along with the empowerment indicators described by the study. All data labelled as “results” or “findings” were extracted digitally and imported verbatim into NVivo 12 software for qualitative analysis. At this stage, findings were extracted regardless of whether they related to empowerment. Decisions were made on relevance during the subsequent analysis. Discussions sections were not included. Data from different qualitative approaches (e.g., thematic analysis, grounded theory etc.) were pooled. Key bits of context (e.g., the age of participants) were held in mind and, where relevant, these were integrated into themes.

Coding text and developing descriptive themes

Data were analysed inductively. Descriptive codes were assigned to sections of text by the first author through a process of line-by-line coding, resulting in a total of 36 initial codes. All the codes were reviewed and discussed by both authors. Initial descriptive codes were then compared and grouped into a hierarchical tree structure. New codes were created to capture the meaning of groups of initial codes, resulting in a tree structure with several layers of descriptive themes. Use of line-by-line coding enabled the translation of concepts from one study to another [Citation23].

Generating analytical themes

Whilst the descriptive themes adhered closely to the original findings of the included studies, the generation of analytical themes aimed to move beyond the findings of the primary studies to generate new concepts, understandings and hypotheses. “Going beyond” the content of the original studies was achieved by using the descriptive themes that emerged from the inductive analysis to provide answers to the more abstract review question [Citation23]. All analytic themes were reviewed and discussed by both authors, with disagreements being resolved through discussion.

Facilitators of, barriers to and components of empowerment for CYP with CF were inferred from the views of CYP and the interpretations provided by researchers in original studies. Facilitators, barriers and components, and implications for clinical practice and research were examined again in light of increasingly analytic themes and changes made as necessary. This process was repeated until the themes were sufficiently abstract to describe and/or explain the initial descriptive themes, inferred facilitators, barriers and components, and the clinical and research implications.

Results

Overview of included studies

The database search identified 887 papers, of which 16 were relevant for inclusion. An additional paper was identified through searching reference sections. summarises the 17 included studies.

Table 1. Summary of studies.

A total of 255 CYP were included in the 17 studies which were conducted across a variety of geographical and cultural contexts. Participants ranged in age from 6 to 21, and were predominantly white, though there were representatives from Black and Asian communities. Many studies did not report severity of CF, but those that did included CYP whose CF ranged from mild to severe.

All studies used interviews as the primary qualitative data collection method. A minority additionally used field diary notes and patient chart review or clinic observations. A wide range of data analysis methods were employed. Studies varied in quality, as shown in . Lack of evidence of researcher reflexivity and lack of involvement of CYP in the design and conduct of the research were key weaknesses across studies. In other respects, the quality of the studies was by and large assessed as good, except for Durst et al. [Citation37] and Moola and Faulkner [Citation39] which reported limited information; see for further details. The implications of this will be considered in the discussion.

Table 2. An overview of the quality assessment using CASP [Citation29] and Thomas et al.'s [Citation30] criteria.

All the included studies described at least one empowerment indicator as defined by Jørgensen et al. [Citation18]. The studies' aims covered a broad range of topics, including identity, decision-making, adherence, the role of family and friends, and communication with healthcare professionals. The majority of studies focused on a specific issue, e.g., needle-related distress, CF-related diabetes, or coping post-lung transplant. Other studies explored the experience of growing up with CF more broadly. Study aims and empowerment indicators are listed for each study in .

Thematic synthesis

The thematic synthesis resulted in the generation of six analytical themes (highlighted in bold). Facilitators of empowerment appeared to include having relational support, having information and understanding, feeling heard and respected, and experiencing mastery and competence. In contrast the prejudice and assumptions of others could be a barrier to empowerment, whilst navigating being different appeared to both influence and be influenced by empowerment. The themes, subthemes, and studies contributing to each are described in , and representative quotations are shown in . In the main text, themes and subthemes are identified by italics.

Table 3. Table of studies contributing to themes.

Table 4. Representative quotations.

In some cases, there was a direct connection between the data and empowerment; for others, further synthesis was required. In contrast to quantitative approaches to data synthesis, the number of contributing studies is not necessarily representative of the strength of the theme [Citation22].

Relational support

Across studies, CYP described support from others, including family, friends and professionals, as promoting positive coping with the demands of CF and CF treatment, and enabling participation in activities that were important to them. Relational support took a variety of forms, which can be broadly divided into practical support associated with treatment regimens and more general emotional support.

Practical support

CYP of all ages implicitly or explicitly referred to the role of parents in providing practical support [Citation32,Citation34,Citation38–41,Citation44]. This took several forms, including undertaking physiotherapy with or for CYP, preparing medications, arranging medical appointments, and providing treatment reminders and encouragement. In one study, CYP reported that parents sometimes let them “slack off” their treatments and reported this lack of monitoring as unsupportive [Citation32]. CYP also spoke of the role that friends played in providing practical support [Citation32,Citation33,Citation35].

Many CYP described the high treatment burden associated with CF and made links between receiving support with treatment and being able to do the things that were important to them, e.g., spending time with friends or participating in sport. CYP identified treatment-related behaviours, such as nagging, as annoying or unwanted, but were reluctant to describe family members or friends as being “unsupportive” when they engaged in these behaviours [Citation32]. Where studies included a focus on relationships with health care professionals, the importance of consistency and trust was repeatedly articulated [Citation31,Citation41,Citation44–46].

Emotional support

The importance of emotional support was highlighted by several studies across a range of contexts. In a study of needle-related distress [Citation31], CYP spoke of the role of parents in providing emotional support during distressing procedures. In other studies, CYP referred to emotional support more generally, e.g., the role of family members “being there and listening” [Citation34].

Participants in several studies noted that, alongside practical treatment related support, health care professionals often provided essential emotional support [Citation31,Citation41,Citation44–46]. CYP described the importance of feeling comfortable talking with their CF team about general life concerns, and of the importance of medical staff understanding what CYP’s lives were like and empathising with the difficulties of adhering to complex treatment regimens [Citation44,Citation46].

Emotional support provided by “good friends” was found to offer protection from the effects of bullying and difficulties associated with trying to keep CF a secret, such as feeling unable to take medication at school [Citation33,Citation35]. This was the case both for younger [Citation33] and older children [Citation35].

In several studies participants referred to support from other CYP with CF [Citation33,Citation39]. Prior to the mid-1990s, CYP were encouraged to socialise through organised events, e.g., summer camps. It became apparent that this practice was potentially dangerous due to infection risks, and as a result, strict infection control guidelines were introduced to prevent face-to-face contact between CYP with CF. These studies alluded to the impact of infection control guidelines, with difference between studies reflecting differing geographical contexts and years of study publication.

Information and understanding

In many studies, CYP described the impact of the amount of information to which they had access. Having information and understanding appeared to facilitate empowerment by influencing how CYP made sense of their experiences, and how confident they felt in making decisions and explaining CF to others. Information appeared to come both from external sources (e.g., clinic consultations), and CYP’s own experiences (e.g., learning from the consequences of medication non-adherence).

Knowledge about CF

CYP's levels of CF knowledge appeared to vary both between and within studies. In several studies, CYP with CF and their peers were found to have difficulty understanding the meaning of CF and how the label could account for their differences [Citation33,Citation39,Citation42]. CYP in a number of studies described awareness of not having the knowledge and skills to feel confident in telling their peers about CF [Citation33,Citation35,Citation42]. Some CYP reported the experience of being diagnosed with complications of CF, such as CF-related diabetes (CFRD), as “shocking” or “terrible,” attributing much of the distress to not understanding the meaning and implications of the news [Citation34]. A lack of information and understanding about CF limited participation, with some CYP avoiding activities because they were unsure what they could do safely or what they might need to do differently [Citation33,Citation38]. Some authors interpreted this as a consequence of professionals lacking consideration for social and cultural factors and overestimating the scientific knowledge of CYP [Citation38,Citation42]. In several studies, CYP described meeting other children with CF at camps giving them a broader perspective of CF and potential implications for their future lives [Citation33,Citation39]. One study described CYP wanting more information about CF’s potential impact on areas such as careers and fertility to enable them to plan ahead [Citation41].

Learning from experience

Many CYP described learning from experience as a process [Citation39]. CYP in a number of studies commented on learning from the consequences of not following treatment plans, with subsequent increased adherence [Citation44,Citation46]. Some described the development of CF-related comorbidities such as CFRD acting as a “wake-up call” [Citation34]. Other CYP commented that occasionally skipping physio or medication did not seem to have an impact on their health [Citation44,Citation46].

Feeling heard and respected

The importance of being heard and respected, particularly in the hospital setting, was articulated by participants of all ages [Citation31,Citation41,Citation43,Citation44]. This was true both for studies focusing on specific issues such as needle-related distress and studies exploring experiences of growing up with CF more generally. Feeling heard and respected encompassed a number of subthemes including, asserting autonomy, for example in relation to ambitions [Citation36,Citation37] and responsibility for CF care [Citation41,Citation44,Citation47], and the importance of shared decision making [Citation34,Citation41,Citation43,Citation44,Citation46]. For many older participants it was important to be treated as an adult, seeing professionals alone or having professionals address them rather than their parents. Having their social life, roles and commitments accommodated were important indicators of this [Citation44,Citation45], and contrasted with adults making decisions.

Many CYP commented on the distress caused when they perceived their voice was not being heard; suggested care could be improved through increased patient input [Citation41]; and believed that they should be the principal person consulted on matters such as diet [Citation43]. Some CYP said having their parents “on them” all the time regarding CF treatment had a negative impact on their relationships and behaviour; when parents stepped back and passed over responsibility for CF care CYP did better [Citation44]. Similarly, a study of clinic consultations, found that CYP felt more competent when professionals used a communication style that encouraged participation rather than telling them what to do, e.g., asking CYP to advise as to which physiotherapy technique they found most helpful [Citation43]. Across studies CYP referred to the importance of others meeting them where they are at. This subtheme was labelled as contextual fit and highlighted the personal and context dependent nature of empowerment.

Mastery and competence

In many studies, CYP made references to the importance of experiencing mastery and being perceived by others as competent. This was the case both in relation to CF care and typical activities of childhood, e.g., achievement in sports [Citation36,Citation47]. Many CYP described feeling competent in managing CF getting easier over time; others spoke of becoming used to it as “all I’ve ever known” [Citation34]. Often feelings of competence were linked to the development of routines [Citation36,Citation47]. Feeling confident and competent in managing CF regimens appeared to increase independence, enabling CYP to adopt more normalised and engaged roles and participate in social activities, such as going on trips [Citation45,Citation46].

CYP in a number of studies commented on enjoyment of physical activities and the role that sport and fitness played in the development of a positive identity [Citation36,Citation39,Citation40,Citation46,Citation47]. The comments of some CYP suggested that these activities provided memorable mastery experiences, which resulted in an enduring sense of competence and achievement [Citation36,Citation40]. In several studies, CYP emphasized that CF did not stop them from achieving goals and aspirations [Citation45–47]. For many CYP, this appeared to relate to the pursuit of normality and ensuring that personal, hopes, values and aspirations were not disrupted by CF. Participants in the only study to focus on the experiencs of CYP who had undergone transplantation, described feelings of freedom post-transplant associated with being able to do ordinary tasks such as walking without breathlessness, housework, and socialising [Citation37]. In contrast, a minority of participants described feelings of hopelessness associated with a sense of CF being a barrier to goals and aspirations [Citation36,Citation39,Citation43].

Prejudice and assumptions

In many studies, CYP described the negative impact of other people’s responses to differences associated with CF. Both explicit teasing or bullying and well-intentioned differential treatment appeared in some cases to act as barriers to empowerment.

Bullying

CYP spoke of attracting negative attention from peers. This was often described as one of the most stressful aspects of growing up with CF, with some CYP becoming anxious as they anticipated the potential reactions of their peers [Citation35]. CYP described peers highlighting and mocking CF-related differences and treating them with suspicion [Citation33,Citation35,Citation42,Citation47]. For some this included being labelled as “druggies” or “contagious,” and bullies encouraging other children to stay away [Citation32,Citation33].

Perceived differential treatment

CYP in several studies reported being treated differently by others because of CF. These perceptions of differential treatment included experiencing teachers and coaches using unequal standards to evaluate performance [Citation33] and healthy peers being less competitive [Citation40]. CYP who had undergone lung transplantation described continuing to feel overprotected, post-transplant [Citation37]. Across studies, CYP expressed strong preferences for adults treating them like any other child, and described feeling frustrated, patronized, or guilty when they perceived differential treatment.

Navigating being different

CYP’s experiences of navigating differences associated with having CF appeared to influence and be influenced by empowerment. This theme had the following subthemes.

Effect of age

CYP in several studies described the process of becoming aware of having CF and of the ways that this made them different from other children. For many children, becoming aware of “being different” occurred between 6 and 8 years [Citation33] and was often reported as being a surprise [Citation33,Citation35]. Younger children in contrast did not reveal any major struggles to mask differences associated with having CF, such as taking medication [Citation47]. Whereas older participants made reference to issues of difference, sameness, and acceptance, and were found to use language that emphasised non-difference [Citation40,Citation44,Citation47].

Effect of comparison and perceptions and management of threats to “normality”

The “CF cough,” taking medications, and physical limitations were reported by CYP in a number of studies as the aspects of CF that most highlighted difference from peers [Citation33,Citation35,Citation47]. Physiotherapy was found to threaten CYP’s sense of “non-difference” in three ways: time taken from activities that maintain “non-different” identity; non-participation in typical childhood activities; and physiotherapy elements perceived as “embarrassing” and “disgusting,” e.g., spitting [Citation46]. Sawicki et al. [Citation44] grouped comments from CYP under “privacy concerns,” including wanting to be “normal,” not wanting to be different or disabled, being self-conscious about taking medications at school, and not wanting to take CF-related equipment outside the home. CYP described being embarrassed undertaking physiotherapy away from home and that joining their peers in typical childhood activities, such as sleepovers, “wasn’t worth the hassle” [Citation45]. Interestingly, CYP expressed a sense of belonging and improved interactions with peers post-transplantation [Citation37].

Deciding if and who to tell

CYP in approximately half of the studies mentioned deciding if and who to tell that they had CF. Telling others about the CF diagnosis appeared to threaten a normal developmental need to gain social approval and develop friendships [Citation33,Citation35,Citation46]. Many participants described ambivalence about disclosing CF, e.g., wanting to tell but fearing that this could jeopardize their potential to have romantic relationships [Citation33]. Some CYP reported that by not telling teachers and coaches about CF, they could be viewed as equally competent in group activities [Citation33]. For others, there seemed to be a more general reluctance to talk about CF [Citation42].

Competing priorities

The impact of having limited time and a high treatment burden was described by CYP across studies and age groups. CYP in several studies described the challenge of balancing competing priorities within the context of a life-limiting condition [Citation40,Citation41]. Many CYP understood that their life expectancy was shorter than that of their peers and questioned whether they would ever attain important developmental milestones [Citation40]. Some older participants described CF as getting in the way of their goals and career aspirations [Citation47], while CYP of all ages reported a sense of inequality and unfairness due to the way that physiotherapy restricted their lives compared to their peers [Citation46]. Younger children who were receiving percussive physiotherapy from their parents expressed a sense of loss at not being able to stay overnight with friends or go on school trips, as they needed parental help. Older CYP spoke of not being able to stay out as late as friends due to physiotherapy [Citation46,Citation47]. CYP who had undergone transplantation reflected on balancing the risks of infection and transplant rejection against “trying to have a normal life,” suggesting that the need to balance competing priorities remains post-transplantation [Citation37].

Although CYP were aware of the benefits of physical activity, for some CYP, CF symptoms meant that even simple everyday activities were exhausting [Citation40]. In the only study to include CYP’s reflections on an intervention, one participant in the small case series reported feeling less limited by CF and more able to consider attending college following an intervention involving physical activity and counselling [Citation39].

Positive aspects of difference

CYP in several studies noted positive aspects of difference associated with having CF, with CYP who had undergone lung transplantation speaking of their surgical scars as representing “strength,” “survival” and a “signature point in my life” [Citation37]. Whilst others spoke of their experience of having CF leading to an increased sense of determination in the face of challenge [Citation36].

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first attempt to synthesise existing qualitative literature relating to empowerment in CYP with CF. Despite a thorough systematic search, no articles explicitly exploring empowerment were identified. However, descriptions of empowerment indicators were found in studies covering a wide range of topics, including identity, decision-making, adherence, interpersonal support and communication.

The key facilitators and components of empowerment in CYP with CF suggested by this review are having relational support, having information and understanding, feeling heard and respected, and experiencing mastery and competence. Barriers to empowerment emerging from the review reflect the opposite of the above-mentioned facilitators; for example, prejudice and assumptions leading to bullying or differential treatment could be considered the opposite of feeling heard and respected. Navigating being different was found to both influence and be influenced by empowerment.

The quality of the included studies was assessed as generally good, except for two papers [Citation37,Citation39]. As can be seen from , none of the themes or subthemes relied solely on these two studies for support. Furthermore, while guidance on meta-synthesis suggests that the number of contributing studies should not necessarily determine the weight of themes [Citation22], it is of note that each subtheme was supported by a minimum of four studies and usually more. Therefore, the findings of the review do not appear to have been comprised by study quality.

Many of the themes emerging from the current meta-synthesis map on to Bravo et al.’s [Citation8] theory of patient empowerment, which was developed from research with adults with a range of long term conditions. This theory highlights the importance of “feeling respected,” experiencing “self-efficacy” and having access to “knowledge.” Note that, by this account, self-efficacy (namely an individual’s belief in their ability to have influence and control over their life [5]), is seen as distinct from and a support to achieving empowerment.

The meta-synthesis findings can also be understood in terms of self-determination theory (SDT [Citation9]), with the theme mastery and competence relating to the competence component of SDT, and the themes feeling heard and respected and relational support fitting with SDT's relatedness component. Furthermore, the theme having information and understanding, along with the afore mentioned themes, support the final SDT component of autonomy [Citation9]. Thus, the positive benefits of mastery and competence, feeling heard and respected, relational support, and information and understanding, suggested by CYP with CF's accounts, are consistent with SDT's premise that competence, relatedness and autonomy support both mental wellbeing and motivation [Citation9].

There are also similarities between the current review’s findings and those from the literature on empowerment in adult patients. For example, in a review focusing on facilitators of patient empowerment in cancer patients during follow-up, identified themes included “knowledge is power” and “communication and interaction between patients and health care professionals” [Citation18]. Similarly, a study of empowerment in adults, in the advanced stages of life-limiting illness, identified themes including “personalised knowledge in theory and practice” and “negotiating personal and healthcare relationships” [Citation27].

Key differences between this review and previous work are that the themes identified included a greater emphasis on support from parents and healthy peers; less emphasis on support from patient groups; and greater significance of themes related to identity and difference. The lives of CYP with or without long term conditions are highly influenced by their adult caregivers. The findings of the current review suggest that empowerment in CYP with CF may be associated with attachment relationships. For example, CYP who can reliably depend on parents and other adults, including health care professionals and teachers, for acceptance, support and information, may be more empowered than those with a tendency towards more anxious-avoidant relationship patterns, who may attempt to be entirely self-sufficient, or those with anxious-ambivalent relationship patterns, who may struggle to separate from caregivers and thus have fewer opportunities to experience mastery and competence [Citation48].

Strengths and limitations

Developing the search strategy was a challenge as the concept of patient empowerment overlaps with other concepts, such as self-efficacy, and can be understood and defined in many different ways [Citation8]. Nonetheless, it was considered important to use a single definition of patient empowerment to enable a rigorous systematic search and synthesis of identified literature. While findings should be generalised with some caution, the included studies encompassed a range of settings and ethnic groups. In addition, although most of the included papers lacked evidence of researcher reflexivity, potentially raising some doubt regarding the researchers' interpretations, this was mitigated by the fact that multiple studies contributed to each theme and that the studies were otherwise largely assessed as relatively good quality. Finally, none of the included studies looked explicitly at empowerment in CYP with CF nor explored in detail the ways that developmental and social factors may influence empowerment. Therefore, it is possible that the included studies, and so this review, may have missed important influences on empowerment. Thus, further qualitative research is required, particularly in relation to developmental and social factors influencing empowerment in CYP with CF.

Clinical implications

The findings of the current review highlight the importance of CYP with CF having accessible information, feeling heard and respected, and experiencing mastery, including in relation to CF self-management. It may therefore be useful for clinicians to continuously review CYP’s understanding of CF and to build a library of accessible resources. There may be a role for service evaluations, for example, using Likert scales to ascertain the extent to which CYP felt heard and respected. Strategies that may enhance both feeling heard and respected, and mastery and competence, include the development of CYP expert patient groups, enabling CYP to be involved in the training of medical staff and other health professionals, service development and creating CYP-friendly resources.

It may also be useful to explore the utility of incorporating issues related to CF and other long term medical conditions into school curriculums, potentially with involvement of clinicians. Clinicians might also work with educators to promote acceptance of difference, to find ways of managing perceived differential treatment, and to support CYP in making choices around managing difference, e.g., by enabling CYP to take medication in private at school, if they wish.

Supporting CYP with CF in coming to terms with difference through interventions such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) may be beneficial. The decisions CYP must make in balancing CF-treatment choices with the day to day social and academic activities of childhood are complex. They might be supported in making these by therapeutic approaches such as motivational interviewing or ACT values-based work.

Conclusions

This meta-synthesis of qualitative studies provides an initial insight into the experiences of CYP with CF relating to patient empowerment. It suggests it is important that CYP with CF have relational support, feel heard and respected, have information and understanding about CF, and experience mastery and competence. It also suggests that more should be done to challenge prejudice and assumptions that lead to bullying or unhelpful differential treatment. Whilst some of the findings resonate with previous reviews exploring empowerment in relation to adults with a range of long-term conditions, the current findings place greater emphasis on support from parents and healthy peers, less emphasis on support from patient groups, and more significance on identity and difference. Further research to better understand the role of developmental stage on empowerment in CYP with CF is warranted.

Online_supplementary_material__R1.pdf

Download PDF (266.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Rowlands J. Empowerment examined. Dev Pract. 1995;5(2):101–107.

- Prigge JK, Dietz B, Homburg C, et al. Patient empowerment: a cross-disease exploration of antecedents and consequences. Int J Res Mark. 2015;32(4):375–386.

- Yeh MY, Wu SC, Tung TH. The relation between patient education, patient empowerment and patient satisfaction: a cross-sectional-comparison study. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;39(45):11–17.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Patient empowerment and health care. In: WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: first global patient safety challenge clean care is safer care [Internet]. Geneva: WHO Press; 2009.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

- Kärner Köhler A, Tingström P, Jaarsma T, et al. Patient empowerment and general self-efficacy in patients with coronary heart disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):1–10.

- Rawlett K. Journey from self-efficacy to empowerment. HC. 2014;2(1):1.

- Bravo P, Edwards A, Barr PJ, The Cochrane Healthcare Quality Research Group, Cardiff University, et al. Conceptualising patient empowerment: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–14.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78.

- Acuña Mora M, Luyckx K, Sparud-Lundin C, et al. Patient empowerment in young persons with chronic conditions: psychometric properties of the Gothenburg young persons empowerment scale (GYPES). PLOS One. 2018;13(7):e0201007–13.

- Malone H, Biggar S, Javadpour S, et al. Interventions for promoting participation in shared decision-making in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;(5):CD012578. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD012578.pub2.

- Cystic Fibrosis Trust. Cystic fibrosis FAQs [Internet]. What is cystic fibrosis. 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.cysticfibrosis.org.uk/what-is-cystic-fibrosis#:∼:text=Cysticfibrosis(CF)isa,causesit%2Cusuallywithoutknowing.

- Coulthard KP. Cystic fibrosis: novel therapies, remaining challenges. J Pharm Pract Res. 2018;48(6):569–577.

- De Boeck K. Cystic fibrosis in the year 2020: a disease with a new face. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(5):893–899.

- Kerem BS, Zielenski J, Markiewicz D, et al. Identification of mutations in regions corresponding to the two putative nucleotide (ATP)-binding folds of the cystic fibrosis gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(21):8447–8451.

- Cystic Fibrosis Trust. Fighting for life-saving drugs [Internet]. Life saving drugs. 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.cysticfibrosis.org.uk/the-work-we-do/campaigning-hard/life-saving-drugs.

- Flemming K, José Closs S, Hughes ND, et al. Using qualitative research to overcome the shortcomings of systematic reviews when designing of a self-management intervention for advanced cancer pain. Int J Qual Methods. 2016;15(1):1–11.

- Jørgensen CR, Thomsen TG, Ross L, et al. What facilitates “patient empowerment" in cancer patients during follow-up: a qualitative systematic review of the literature”. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(2):292–304.

- Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: issues and illustrations. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23(5):581–599.

- Rappaport J. Studies in empowerment. Prev Hum Serv [Internet]. 1984;3:1–7.

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(Figure 1):181–188.

- Dixon-Woods M, Bonas S, Booth A, Jones DR, et al. How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qual Res. 2006;6(1):27–44.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45–10.

- Oliver C. Critical realist grounded theory: a new approach for social work research. Br J Soc Work. 2012;42(2):371–387.

- Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443.

- Barroso J, Gollop CJ, Sandelowski M, et al. The challenges of searching for and retrieving qualitative studies. West J Nurs Res. 2003;25(2):153–178.

- Wakefield D, Bayly J, Selman LE, et al. Patient empowerment, what does it mean for adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: a systematic review using critical interpretive synthesis. Palliat Med. 2018;32(8):1288–1304.

- Acuña Mora M, Sparud-Lundin C, Burström Å, et al. Patient empowerment and its correlates in young persons with congenital heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;18(5):389–398.

- Public Health Resource Unit. Critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) qualitative checklist [Internet]. 2006. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf.

- Thomas J, Sutcliffe K, Harden A, et al. Children and healthy eating: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators. London (UK): EPPI-Centre, University of London; 2003.

- Ayers S, Muller I, Mahoney L, et al. Understanding needle-related distress in children with cystic fibrosis. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16(Pt 2):329–343.

- Barker DH, Driscoll KA, Modi AC, et al. Supporting cystic fibrosis disease management during adolescence: the role of family and friends. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38(4):497–504.

- Christian BJ, D'Auria JP. The child’s eye: memories of growing up with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Nurs. 1997;12(1):3–12.

- Dashiff C, Suzuki-Crumly J, Kracke B, et al. Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes in older adolescents: parental support and self-management. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2013;18(1):42–53.

- D’Auria J, Christian B, Richardson L. Through the looking glass: Children’s perceptions of growing up with cystic fibrosis. Can J Nurs Resaerch [Internet]. 1997;29(4):99–112.

- Denford S, Hill DM, Mackintosh KA, On behalf of Youth Activity Unlimited – A Strategic Research Centre of the UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust, et al. Using photo-elicitation to explore perceptions of physical activity among young people with cystic fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):220.

- Durst CL, Horn MV, MacLaughlin EF, et al. Psychosocial responses of adolescent cystic fibrosis patients to lung transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2001;5(1):27–31.

- Keyte R, Egan H, Mantzios M. An exploration into knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs towards risky health behaviours in a paediatric cystic fibrosis population. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2019;13:117954841984942.

- Moola FJ, Faulkner GEJ. 'A tale of two cases:' the health, illness, and physical activity stories of two children living with cystic fibrosis. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;19(1):24–42.

- Moola FJ, Faulkner GEJ, Schneiderman JE. "No time to play": perceptions toward physical activity in youth with cystic fibrosis. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2012;29(1):44–62.

- Nuttall P, Nicholes P. Cystic fibrosis: adolescent and maternal concerns about hospital and home care. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1992;15(3):199–213.

- Pizzignacco TMP, de Lima RAG. Socialization of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis: Support for nursing care. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2006;14(4):569–577.

- Savage E, Callery P. Clinic consultations with children and parents on the dietary management of cystic fibrosis. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(2):363–374.

- Sawicki GS, Heller KS, Demars N, et al. Motivating adherence among adolescents with cystic fibrosis: youth and parent perspectives. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50(2):127–136.

- Williams B, Mukhopadhyay S, Dowell J, et al. Problems and solutions: accounts by parents and children of adhering to chest physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(14):1097–1105.

- Williams B, Mukhopadhyay S, Dowell J, et al. From child to adult: an exploration of shifting family roles and responsibilities in managing physiotherapy for cystic fibrosis. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(10):2135–2146.

- Williams B, Corlett J, Dowell JS, et al. I've never not had it so I don't really know what it's like not to: nondifference and biographical disruption among children and young people with cystic fibrosis. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(10):1443–1455.

- Prior V, Glasser D. Understanding attachment and attachment disorders: theory, evidence and practice. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2006.