Abstract

Purpose

We explored the content and attainment of rehabilitation goals the first year after rehabilitation among patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases.

Methods

Participants (n = 523) recorded goals in the Patient Specific Functional Scale at admission and reported goal attainment at admission, discharge, and 12 months after rehabilitation on an 11-point numeric rating scale. Goal content was linked to the ICF coding system and summarized as high, maintained, or no attainment. Changes in absolute scores were investigated using paired samples t-tests.

Results

Goals had high attainment with a significant positive change (–1.83 [95% CI −2.0, −1.65], p > 0.001) during rehabilitation, whereas goals had no attainment with a significant negative change (0.36 [0.14, 0.57], p > 0.001) between discharge and 12 months after rehabilitation. Goals focusing on everyday routines, physical health, pain management, and social or work participation were highly attained during rehabilitation. Goals that were difficult to enhance or maintain after rehabilitation addressed everyday routines, physical health, and work participation.

Conclusion

The positive changes in goal attainment largely occurred during rehabilitation, but they appeared more difficult to maintain at home. Therefore, rehabilitation goals should be reflected in the follow-up care planned at discharge.

The contents of rehabilitation goals reflect the complexity and wide range of challenges patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases experience.

Positive changes in goal attainment largely occur during rehabilitation and appear to be more difficult to enhance or maintain at home.

Rehabilitation interventions and follow-up care should be tailored to support patients in maintaining their attained goals for healthy self-management.

Rehabilitation goals should be reflected in the follow-up care planned at discharge.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) are a complex group of chronic disorders that substantially impact both individuals and society [Citation1–3]. Earlier diagnosis and more effective pharmacological and surgical treatment have led to improved prognosis and better lives for patients with RMDs [Citation4]. However, the effect of such treatment has been reported to be suboptimal [Citation5,Citation6] and successful management of these conditions also relies on multidisciplinary rehabilitation to maintain general health and cope with health changes inherent in living with a chronic condition [Citation7–10]. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation aims at enabling patients to self-manage healthy behaviour [Citation11–14], manage symptoms and treatment, and reach and maintain their optimal physical, psychological, and social functioning [Citation15].

Rehabilitation goals are recognized as a core component of ensuring effective multidisciplinary rehabilitation [Citation16–18] and contribute to patients’ healthy self-management. A study aiming to develop an indicator set to measure quality in RMD rehabilitation found goal-setting to be an appropriate indicator of rehabilitation quality on the structure level [Citation19]. Such goals are considered essential for directing the rehabilitation focus and to drive the rehabilitation process forward, both during the rehabilitation stay and in the patients’ home and everyday life after discharge [Citation20–23].

It is generally acknowledged that goals should be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and relevant, and feasible within a time frame (SMART goals) [Citation24,Citation25]. Moreover, goals should refer to an intended future state of functioning, implying a change in behaviour and planned actions [Citation23]. A recent study assembling theory and empirical evidence on goal-setting practices affirmed that goals also have to be meaningful and important to the patient [Citation26]. There is growing evidence that rehabilitation is most effective when the goal-setting process is patient-centred [Citation27,Citation28] and when the patient is encouraged to communicate their needs and preferences [Citation26,Citation29,Citation30]. Goals developed in a shared decision-making process between the patient and the health care professional are acknowledged to strengthen the patients’ confidence and sense of ownership, affecting the individual rehabilitation processes and enhancing the patients’ motivation for goal attainment [Citation31–33]. Nonetheless, goal-setting practices differ, and little knowledge is available on how and whether patients with RMDs attain their rehabilitation goals over time after rehabilitation in specialized health care.

Therefore, the present study set out to explore the content of activity-related rehabilitation goals reported by patients with RMDs and the levels of goal attainment during the first year after rehabilitation in specialized health care.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The current study is nested within a large pragmatic multicentre cohort study in which the main aim was to explore continuity and quality in rehabilitation trajectories for patients with RMDs. Patients undergoing in-patient or out-patient rehabilitation were enrolled from five specialized rehabilitation institutions and four rheumatology hospital departments across Norway (all hereafter referred to as rehabilitation centres) and followed for 1 year after rehabilitation.

Participants were included in the study if they were ≥18 years old, proficient in spoken and written Norwegian, and admitted to rehabilitation in specialized health care due to inflammatory rheumatic diseases (spondyloarthritis [SpA], psoriatic arthritis [PsA], rheumatoid arthritis [RA]), osteoarthritis, chronic low back pain, chronic neck/shoulder pain, chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia), osteoporosis, connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], myositis, etc.), or fractures or orthopaedic surgery that required rehabilitation. Participants also had to have acquired a Bank-ID that allowed secure login to a digital data reporting system containing patient-reported questionnaires. Participants were excluded if they had reduced cognitive function or severe mental illness.

Data collection

Data were collected between November 2015 and January 2017, and the 1-year follow-up period was completed by January 2018. Patient-reported data addressing health status and function, activity-related rehabilitation goals, and goal attainment were collected electronically at admission and discharge from rehabilitation, and 12 months after rehabilitation.

When reporting at admission and discharge, participants had access to personal guidance from health care professionals from the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team. One year after rehabilitation, participants received a text message and an e-mail with a link to the digital reporting system to complete the questionnaires. One reminder was sent after 1 week to those who did not respond.

Health status and function

Participants’ demographic characteristics (age, gender, body mass index, education level, and employment status), referral diagnoses, comorbidities, smoking status, and frequencies of physical and social activities were collected at admission to rehabilitation.

Activity-related rehabilitation goals

Up to five activity-related rehabilitation goals were described by each participant in collaboration with health care professionals from the multidisciplinary rehabilitation team during a goal-setting conversation at admission to rehabilitation and recorded in the Patient Specific Functional Scale (PSFS) [Citation34]. The PSFS aims to detect activity limitations experienced by patients [Citation34]; therefore, the goals in our study were activity related and reflect the importance of addressing such challenges. A validated translation of the PSFS is accessible in Norwegian and found to be reliable and responsive in patients with musculoskeletal disorders when tested in primary health care settings in Norway [Citation35].

Goal attainment

Goal attainment was self-reported by participants at rehabilitation admission, discharge, and 12 months after rehabilitation on an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS) in the PSFS. The scale ranged from 0 (no goal attainment) to 10 (full goal attainment). In addition, participants reported their motivation for attaining each goal at admission on an 11-point NRS ranging from 0 (no motivation) to 10 (fully motivated), which was calculated as a mean score of all goals for each participant.

Analyses

Drop-outs

Analysis on between group differences of the demographic baseline characteristics were performed for participants and non-participants at 12 months after rehabilitation.

Content of activity-related rehabilitation goals

The content of the self-reported activity-related rehabilitation goals were linked to the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF) coding system [Citation36]. The ICF Linking Rules from Cieza et al. [Citation37–39], with refinements, were applied in the linking process as follows. All activity-related rehabilitation goals were assigned third-level ICF codes (three digits). The goals were then linked to one main ICF category and up to three additional categories to avoid skewed interpretation and loss of information when the goals were multicomponent. Thus, each goal could be linked to up to four ICF codes. The following additional linking rule was developed by the authors and applied to supplement the ICF linking rules: If a goal was complex with multiple components, the main ICF category was described within an activity and participation concept, reflecting clinical relevance and ensuring external validity.

Two researchers (HLV and MK) who are familiar with the ICF and the ICF Linking Rules, and have different health professional backgrounds (physiotherapist and occupational therapist, respectively), linked the first 50 registered activity-related rehabilitation goals to the ICF independently. They then compared and contrasted their linking and agreed on the most appropriate category when they linked differently. They had a linking agreement of 84% before reaching consensus on their differences. HLV linked the remaining goals to the ICF according to the agreed linking strategy.

Goal attainment

The absolute changes in scores from admission to discharge, from discharge to 12 months after rehabilitation, and from admission to 12 months after rehabilitation were calculated as the mean score of the one to five patient-reported activity-related rehabilitation goals combined. These changes were investigated using paired samples t-test. All statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS version 27.

To describe coded content within groups based on attainment of the activity-related rehabilitation goals, changes in goal attainment reported in the PSFS for each goal were calculated between admission and rehabilitation discharge, between discharge and 12 months after rehabilitation, and between admission and 12 months after rehabilitation. A 2-point change in the PSFS score was considered a clinically relevant difference [Citation35]. Goals with a positive change ≥2 points were categorized as high attainment, goals with a positive change between 0 and 2 points as maintained attainment, and goals with a negative change as no attainment. Frequency counts were generated for the activity-related rehabilitation goal content and summarized within groups as high, maintained, and no attainment of the goals.

Ethics

All participants received oral and written information about the study prior to signing informed consent forms and underwent the rehabilitation they would have received regardless of participation in the study. Data were stored at the highest security level. The study was approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services, Oslo University Hospital (2015/16099). The ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration and privacy requirements were followed.

Results

A total of 523 participants completed the assessments at baseline, 436 of whom (83%) completed discharge assessments and 354 (68%) the assessment 12 months after rehabilitation in specialized health care. presents the participants’ baseline characteristics. The largest diagnostic groups were inflammatory rheumatic disease (SpA, PsA, RA; 50%) and chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia; 29%). The majority of participants were women and middle-aged, and 46% were still working. In general, participants had high motivation to attain their activity-related rehabilitation goals at admission with a mean (SD) score of 7.9 (2.0).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 523 patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases undergoing rehabilitation in specialized health care.

Non-participants at 12 months after rehabilitation were significantly younger (p ≤ 0.001), were smoking (p = 0.003), had higher BMI (p = 0.03), shorter disease duration (p = 0.04), were less physically active (p = 0.02) and less social participating (p = 0.01), and they were significantly more often diagnosed with chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia; p = 0.002), than participants reporting at 12 months after rehabilitation.

All 523 participants registered at least one activity-related rehabilitation goal at admission: 519 (99%) reported at least three goals, 323 (62%) reported four goals, and 210 (40%) five goals. A total of 2096 goals were identified at admission; 1766 (83%) goals were rescored at rehabilitation discharge and 1375 (66%) 12 months after rehabilitation.

Content of activity-related rehabilitation goals

Linked ICF codes

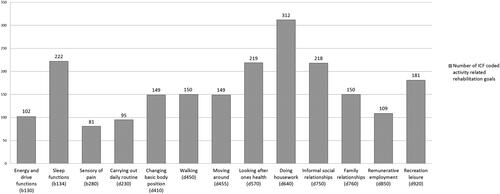

The 2096 activity-related rehabilitation goals identified at rehabilitation admission were linked to 2705 separate ICF codes, comprising 39 distinctive ICF categories. Thirteen categories were linked more frequently than the others and represented 2137 of the 2705 separate ICF codes (79%). These categories comprised the following ICF third-level categories: Doing Housework (d640; n = 312 ICF codes linked to this ICF category at admission, 14.9%), Sleep Functions (b134; n = 222, 10.6%), Looking After One’s Health (d570; n = 219, 10.4%), Informal Social Relationships (d750; n = 218, 10.4%), Remunerative Employment (d850; n = 181, 8.6%), Walking (d450; n = 150, 7.2%), Recreation and Leisure (d920; n = 150, 7.2%), Changing Basic Body Position (d410; n = 149, 7.1%), Moving Around (d455; n = 149, 7.1%), Family Relationships (d760; n = 109, 5.2%), Energy and Drive Functions (b130; n = 102, 4.9%), Carrying Out Daily Routine (d230; n = 95, 4.5%), and Sensory of Pain (b280; n = 81, 3.9%). presents the distribution of the 13 most frequent ICF categories in coded activity-related rehabilitation goals, and presents detailed descriptions of the 13 ICF categories and activity-related rehabilitation goals with examples.

Figure 1. Distribution of the 13 most frequent third-level ICF categories in linked activity-related rehabilitation goals (n = 2137) reported in the Patient Specific Functional Scale by 523 patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases undergoing rehabilitation in specialized health care. The number above each bar is the number of goals.

Table 2. Content of the 13 most frequent third-level ICF categories in linked activity-related rehabilitation goals (n = 2137) reported in the patient specific functional scale by 523 patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases undergoing rehabilitation in specialized health care.

Content descriptions

“Enhance physical health and general well-being” was a topic put forward in a large proportion of the activity-related rehabilitation goals (d410, d450, d455, and d570) and involved being able to move around, coordinate movements, and maintain an appropriate level of physical activity alongside pursuing a balanced and healthy diet, losing weight, avoiding smoking, and staying fit. Content addressing managing the household (d640) was the most frequently used single code and involved being able to do or spend time doing housework, such as cleaning the house, washing clothes, or other household chores. The goals focusing on managing symptoms related to RMDs (b130, b134, and b280) involved enhancing energy and motivation levels and optimizing rest and recovery, together with sleep and pain management. These goals were also frequently expressed as symptom management to further pursue daily activities and participation. Goals expressing wishes to manage everyday routines (d230) addressed content on carrying out daily routines, such as exercising four times a week, eating breakfast every day, or eating three main meals a day, along with using a time table for appointments or planning a schedule for the day. Goals addressing content related to social participation and leisure (d750 and d920) comprised wishes to be more social and meet up with friends in various settings, or wishes to attend recreational activities or organized activities, plays and sports, physical fitness programmes, going to cinemas, museums, or theatres, engaging in crafts and hobbies, or traveling for pleasure. The goals focusing on remunerative employment (d850) concerned different work relations and described employment participation and wishes to clarify and determine their future work load. The coded content in goals related to interactions and personal relationships with other people (d760) comprised wishes to engage in and prioritize activities with close family and to contribute to these important personal relationships.

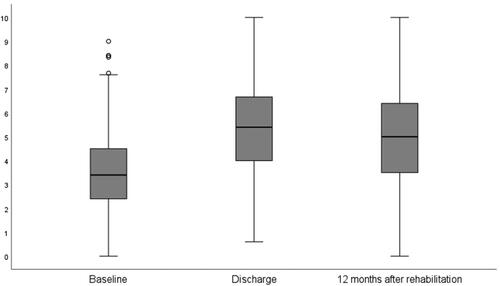

Overall goal attainment

The mean score for goal attainment on the PSFS increased between baseline and discharge, but decreased between discharge and 12 months after rehabilitation (). When looking at changes in the absolute scores, we found a significantly positive change in goal attainment from admission to discharge (change in score −1.83 [95% CI −2.0, −1.65], p > 0.001), but there was a significantly negative change in goal attainment between discharge and 12 months after rehabilitation (change in score 0.36 [95% CI 0.14, 0.57], p > 0.001). However, a significant positive change in goal attainment occurred over the total rehabilitation period from admission to 12 months after rehabilitation (change in score −1.41 [95% CI −1.61, −1.20], p > 0.001).

Figure 2. Median goal attainment scores of the one to five activity-related rehabilitation goals reported by patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases on an 11-point numeric rating scale at baseline (n = 2096 goals), discharge (n = 1766), and 12 months after rehabilitation (n = 1375) in specialized health care. The whiskers represent the smallest and largest number in the sets.

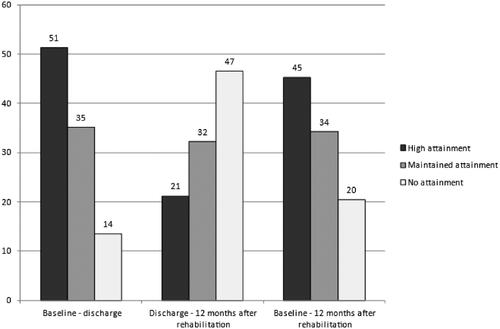

A total of 907 (51.4%) goals were categorized as high goal attainment at discharge from rehabilitation, whereas 620 (35.1%) and 239 (13.5%) were categorized as maintained attainment and no goal attainment, respectively. Two hundred and fifty-nine (21.2%) goals were above the cut-off for high attainment between discharge and 12 months after rehabilitation, 394 (32.2%) goals were maintained, and 570 (46.6%) goals had a negative change and considered in the no attainment group. Between baseline and 12 months after rehabilitation, 623 (45.3%) goals were in the high attainment group, 471 (34.3%) in the maintained attainment group, and 281 (20.4%) in the no attainment group ().

Figure 3. Distribution of high, maintained, and no goal attainment in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (n = 523) between baseline and discharge, discharge and 12 months after rehabilitation, and between baseline and 12 months after rehabilitation. The number above each bar is the percentage of goals in each group of goal attainment. The y-coordinates represent percentages.

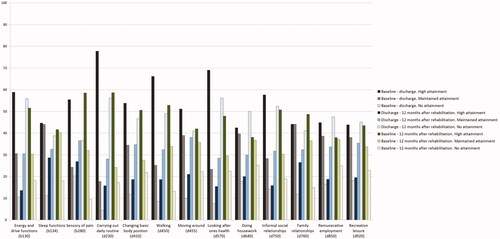

Content of goals with high, maintained, and no attainment

The distribution of the 13 most frequent ICF categories in coded activity-related rehabilitation goals based on attainment during the rehabilitation stay, after the rehabilitation stay, and from admission to 12 months after rehabilitation is presented in . At discharge from rehabilitation, goals in managing everyday routines (d230) were the content with the highest frequency in the high attainment group. Moreover, goals with content on physical health and general well-being (d410, d450, d455, and d570), pain management (b280), enhancing energy and motivation levels (b130), informal social relationships (d750), work participation (d850), and leisure activities (d920) appeared most frequently in the high attainment group during rehabilitation. Managing housework (d640), interacting in personal relationships (d760), and sleep management (b134) appeared equally or close to equally as frequent in the high and maintained goal attainment groups during the rehabilitation stay.

Figure 4. Distribution of the 13 most frequent third-level ICF categories in linked activity-related rehabilitation goals reported in the Patient Specific Functional Scale among rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease patients (n = 523) undergoing rehabilitation in specialized health care. The patients were grouped as high, maintained, and no goal attainment for the rehabilitation stay, the follow-up period after rehabilitation, and the total rehabilitation period from admission to 12 months after rehabilitation. The y-coordinates represent percentages.

In the period between discharge and the 12-month follow-up, the majority of goals appeared most frequently in the no attainment group, especially content on managing everyday routines (d230), work participation (d850), enhancing energy and motivation levels (b130), and content on physical health and general well-being (d410, d450, d455, and d570). Goals in managing housework (d640) and social participation and leisure (d750 and d920) also had high frequencies of no attainment. Nonetheless, when looking at the rehabilitation period from admission to 1 year after rehabilitation as a whole, all goals were maintained or in the high attainment group.

Discussion

This study is one of a few to explore the content and goal attainment in activity-related rehabilitation goals among individuals with RMDs. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore levels of goal attainment during and after rehabilitation in specialized health care.

The results demonstrate that goals comprise a wide range of content addressing important parts of everyday life, such as general health and well-being, leisure activities, and social and work participation. Our findings show that positive changes in goal attainment largely occur during the rehabilitation stay, and it appears more difficult to enhance or maintain these positive changes after coming home. Nonetheless, when observing the rehabilitation period from admission to 1 year after rehabilitation as a whole, our results demonstrate a significant positive change in goal attainment with a higher frequency of goals with high attainment than goals with no attainment. During rehabilitation, goals focusing on everyday routines, enhancing physical health and general well-being, pain management, enhancing energy and motivation levels, or social or work participation appeared most frequently in the high attainment group. After rehabilitation, goals addressing the management of everyday routines, social and work participation, recreational and leisure activities, enhancing energy and motivation levels, and physical health and general well-being appeared most frequently in the no goal attainment group.

In line with previous research [Citation40–42], our results show that rehabilitation goals comprise a broad spectrum of everyday activities and participation, extending from enhanced physical health and general well-being and symptom management to managing the household, leisure activities, social and work participation, and reinforcing family relationships. The wide range of content demonstrates the complexity and multicomponent challenges experienced by patients with RMDs, and indicates their concern with improving several aspects of their lives. Moreover, our results support previous research on content in in-patient RMD rehabilitation [Citation7] in which the content focussed on physical activity and fitness in collaboration with the physiotherapist, attending pain management education classes, having a structured plan and time table for the rehabilitation stay, and spending time together and connecting with other people with similar challenges in diverse activities and settings. In our study, such goals showed high attainment during the rehabilitation stay, underlining that patients’ needs and preferences for a healthier life are mirrored in the rehabilitation interventions and targeted by health care professionals in current rehabilitation practice.

Enhanced physical health and general well-being were the goal contents most frequently described by patients in our study. This is consistent with other research, which has found that the most common long-term goal put forward by patients with RMDs participating in specialized rehabilitation concerns physical exercise aiming for the maintenance or improvement of physical fitness [Citation41]. Patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease [Citation43–46]. Therefore, interventions targeting physical activity and physical fitness are highly recommended [Citation47–49] and, not surprisingly, are a part of the rehabilitation goals developed in collaboration with health care professionals. However, a challenge concerned with goals of pursuing regular fitness activities is the patient’s ability to manage this as a routine in a demanding everyday life at home. We found that both physical activity and managing routines were goals that were difficult to attain at home. A recent study in clinical epidemiology suggested that replacing sedentary time with light-intensity physical activity could have beneficial health effects [Citation50]. From the perspective of public health, management plans could focus more on the importance of everyday activities to supplement going to the gym, and could include activities such as walking or biking to work, getting off the bus one stop before home, taking the stairs instead of the elevator, or doing work in and around the house.

Household management was the most frequently single ICF-code used to describe rehabilitation goals in our study. One reason for this may be the high proportion of females in our study, and that household traditionally has been the domain of women. However, gender equality has come a long way in Norway, with 66.3% of all women of working age being in paid employment in 2021 [Citation51]. Correspondingly, men also increasingly take part in household chores. While time used on household management by women was five times that of men in 1970, it was reduced to twice as much in 2010 [Citation52]. Thus, even if traditional roles may still play a part, the large proportion of goals related to household chores may also reflect that men increasingly take responsibility for such activities. This hypothesis is supported by results from a Norwegian rehabilitation study with 65% male participants, where household management was one of the most frequent cited important activity limitations [Citation53].

Our results demonstrate that patient-reported rehabilitation goals are most frequently highly attained, with a significant positive change in goal attainment during the rehabilitation stay, whereas the majority of goals had a significant negative change after rehabilitation. These findings reflect the instant and direct effect of the rehabilitation interventions delivered during the rehabilitation stay, but also support previous research finding a declining effect of rehabilitation over time [Citation7,Citation53–56]. Research has shown that patients feel ill-prepared for managing activities in their everyday lives when discharged from rehabilitation [Citation57]. A recent study addressing patients’ experiences with challenges to attaining their goals after discharge from rheumatology rehabilitation found time, additional health problems, changes in routines, and events outside of the plan to be areas that affected goal attainment [Citation42]. A finite effect of a rehabilitation stay is not surprising, as patients are taken out of their demanding everyday context to attend systematized and individualized rehabilitation. Therefore, it is plausible that patients with chronic conditions are in need of repetitive rehabilitation stays in specialized health care. On the other hand, maintenance of goal attainment and behavioural changes may be enhanced by increasing the focus on the follow-up care patients receive in primary health care after rehabilitation. A recent study investigating quality indicators for RMD rehabilitation found a low pass-rate (22%) for the process indicator “External personnel were involved in planning follow-up”, and a pass-rate of 55% for the structure indicator of having a “Written individual plan for follow-up” [Citation19], supporting suboptimal follow-up care in current rehabilitation practice. Although the current design of follow-up care interventions lacks consensus [Citation58], results from one of our previous studies [Citation59] indicate that discussing and planning follow-up care at discharge from rehabilitation is significantly associated with the follow-up care received; thus, plans for follow-up in primary health care should be an integral part of rehabilitation in specialized health care. The current study may add that the activity-related rehabilitation goals put forward should be reflected in the follow-up care planned at rehabilitation discharge, and that health care professionals should be specifically aware of offering support when the goals address physical activity, recreational and leisure activities, managing everyday routines, and social and work participation, as these goals are more difficult to attain or maintain after rehabilitation in specialized health care. Furthermore, studies on methods to improve patient maintenance of behavioural changes are warranted.

There is some evidence of a positive relationship between work and health status [Citation60,Citation61], and work participation was frequently addressed by the patients in our study. Recently, there has been an increased political focus on supporting people with chronic conditions in continuing or returning to work, and “Points to consider to support people with RMDs to participate in healthy and sustainable work” is currently being developed by the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), as a work participation gap remains when comparing patients with RMDs to the general population [Citation62]. In Norway, political strategies state that all rehabilitation programmes in specialized health care should have a work-oriented focus, and a recent feasibility randomized controlled trial found that job retention-focussed vocational rehabilitation including work assessment, ergonomics, work modification, activity diaries, action planning, and arthritis self-management in the workplace is a credible and acceptable intervention for reducing work productivity loss, absenteeism, and perceived risk of job loss in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases [Citation61]. Nonetheless, our results show that patients do not attain work-related goals after rehabilitation. This should encourage future research to explore implementation strategies for such interventions in RMD rehabilitation and encourage further improvement of clinical rehabilitation practices to support patients with RMDs in participating and remaining in healthy and sustainable paid work.

In our study, we used the ICF, as it is a well-known and validated framework tool for describing and comparing health information [Citation39,Citation63]. However, a potential weakness is that a large number of ICF categories initially described the content of our patients’ goals before they were delimited into the 13 most frequent ICF categories, which led to a description of only the largest trends. These limitations potentially address a weakness of the ICF coding system and a shortcoming of its validity in describing the content of complex rehabilitation. Another limitation of our study was that the participants did not have the opportunity to change their goals at rehabilitation discharge; thus, the patients’ progress and modification in needs and preferences towards goals in their home setting may have been lost. Future research on activity-related rehabilitation goals should allow a dynamic goal-setting process, with discussion and adjustment of the rehabilitation goals both before and after discharge from rehabilitation. Our results were based on the participants self-reported data; consequently, the results may have been affected by recall bias and peoples known tendency of overemphasizing normative behaviours, such as goal attainment [Citation64,Citation65]. The strengths of our study include the relatively large sample size and the inclusion of patients with a wide diversity of RMDs from rehabilitation centres in different geographical locations in Norway, which support the generalizability of our results.

In summary, our findings show that rehabilitation goals comprise a wide range of content reflecting the complexity of the challenges patients with RMDs experience. Regarding goal attainment, positive changes largely occur during the rehabilitation stay, and it appears to be more difficult to enhance or maintain positive changes after coming home. Therefore, rehabilitation interventions and follow-up care should be tailored to support the patients in maintaining their attained goals for healthy self-management, as these may improve health outcomes and prolong the effects of rehabilitation. Moreover, rehabilitation goals that are put forward should be reflected in the follow-up care planned at rehabilitation discharge.

Acknowledgements

All authors contributed to the analyses and interpretation of data. All authors contributed substantially to drafting the article or revising it critically.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–2223.

- van der Heijde D, Daikh DI, Betteridge N, et al. Common language description of the term rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) for use in communication with the lay public, healthcare providers and other stakeholders endorsed by the European league against rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR). Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(6):829–832.

- EUMUSC.NET. Musculoskeletal health in Europe report v5.0. [cited 2019 May 28]. Available from: http://eumusc.net/publications.cfm

- Krishnan E, Lingala B, Bruce B, et al. Disability in rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biological treatments. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(2):213–218.

- Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(2):318–328.

- Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(2):220–233.

- Klokkerud M, Hagen KB, Lochting I, et al. Does the content really matter? A study comparing structure, process, and outcome of team rehabilitation for patients with inflammatory arthritis in two different clinical settings. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41(1):20–28.

- Vlieland TPMV, vdEC, da Silva JAP. Rehabilitation in rheumatic diseases. In: Bijlsma JWJ, editor. EULAR textbook on rheumatic diseases. 1st ed. London: BMJ Group; 2012. p. 1183–1198.

- Geenen RF. Psycho-social approaches in rheumatic diseases. In: Bijlsma JWJ, editor. EULAR textbook on rheumatic diseases. 1st ed. London (UK): BMJ Group; 2012. p. 139–162.

- McCuish WJ, Bearne LM. Do inpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes improve health status in people with long-term musculoskeletal conditions? A service evaluation. Musculoskelet Care. 2014;12(4):244–250.

- de Ridder D, Geenen R, Kuijer R, et al. Psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Lancet. 2008;372(9634):246–255.

- Iversen MD, Hammond A, Betteridge N. Self-management of rheumatic diseases: state of the art and future perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):955–963.

- Dures E, Hewlett S. Cognitive-behavioural approaches to self-management in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(9):553–559.

- Knittle K, De Gucht V, Maes S. Lifestyle- and behaviour-change interventions in musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(3):293–304.

- WHO. Rehabilitation. [cited 2016 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/rehabilitation/en/

- Wade DT, de Jong BA. Recent advances in rehabilitation. BMJ. 2000;320(7246):1385–1388.

- Steiner WA, Ryser L, Huber E, et al. Use of the ICF model as a clinical problem-solving tool in physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine. Phys Ther. 2002;82(11):1098–1107.

- Klokkerud M, Hagen KB, Kjeken I, et al. Development of a framework identifying domains and elements of importance for arthritis rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(5):406–413.

- Johansen I, Klokkerud M, Anke A, et al. A quality indicator set for use in rehabilitation team care of people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases; development and pilot testing. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):265.

- Siegert RJ, Taylor WJ. Theoretical aspects of goal-setting and motivation in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(1):1–8.

- MWA B. Oxford handbook of rehabilitation medicine. United States (NY): Oxford University Press; 2005.

- Playford ED, Siegert R, Levack W, et al. Areas of consensus and controversy about goal setting in rehabilitation: a conference report. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):334–344.

- Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):291–295.

- Schut HA, Stam HJ. Goals in rehabilitation teamwork. Disabil Rehabil. 1994;16(4):223–226.

- Bovend’Eerdt TJ, Botell RE, Wade DT. Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):352–361.

- Dekker J, de Groot V, Ter Steeg AM, et al. Setting meaningful goals in rehabilitation: rationale and practical tool. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(1):3–12.

- Sugavanam T, Mead G, Bulley C, et al. The effects and experiences of goal setting in stroke rehabilitation – a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(3):177–190.

- Plewnia A, Bengel J, Körner M. Patient-centeredness and its impact on patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in medical rehabilitation. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):2063–2070.

- Law M, Baptiste S, Mills J. Client-centred practice: what does it mean and does it make a difference? Can J Occup Ther. 1995;62(5):250–257.

- Cameron LJ, Somerville LM, Naismith CE, et al. A qualitative investigation into the patient-centered goal-setting practices of allied health clinicians working in rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(6):827–840.

- Levack WM, Weatherall M, Hay-Smith JC, et al. Goal setting and strategies to enhance goal pursuit in adult rehabilitation: summary of a cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;52(3):400–416.

- Rose A, Rosewilliam S, Soundy A. Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):65–75.

- Yun D, Choi J. Person-centered rehabilitation care and outcomes: a systematic literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;93:74–83.

- Westaway MD, Stratford PW, Binkley JM. The patient-specific functional scale: validation of its use in persons with neck dysfunction. The. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27(5):331–338.

- Moseng TT, Holm I. Pasient-Spesifikk Funksjonsskala. Et nyttig verktøy for fysioterpaeuter i primaerhelsetjenesten. Nor J Physiother. 2013;2:20–26.

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF): World Health Organization. 2018 [cited 2018 Mar 2]. Available from: http://www.who.int/classification/icf/en/.2018

- Cieza A, Brockow T, Ewert T, et al. Linking health-status measurements to the international classification of functioning, disability and health. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34(5):205–210.

- Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, et al. ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(4):212–218.

- Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J, et al. Refinements of the ICF linking rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(5):510–574.

- Meesters J, Hagel S, Klokkerud M, et al. Goal-setting in multidisciplinary team care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an international multi-center evaluation of the contents using the international classification of functioning, disability and health as a reference. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(9):888–899.

- Berdal G, Sand-Svartrud A-L, Bø I, et al. Aiming for a healthier life: a qualitative content analysis of rehabilitation goals in patients with rheumatic diseases. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(7):765–778.

- Hamnes B, Berdal G, Bø I, et al. Patients’ experiences with goal pursuit after discharge from rheumatology rehabilitation: a qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2021;19(3):249–258.

- Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(12):1690–1697.

- Mathieu S, Pereira B, Soubrier M. Cardiovascular events in ankylosing spondylitis: an updated meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44(5):551–555.

- Polachek A, Touma Z, Anderson M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular morbidity in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(1):67–74.

- Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):17–28.

- Rausch Osthoff AK, Juhl CB, Knittle K, et al. Effects of exercise and physical activity promotion: meta-analysis informing the 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis and hip/knee osteoarthritis. RMD Open. 2018;4(2):e000713.

- Rausch Osthoff AK, Niedermann K, Braun J, et al. 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(9):1251–1260.

- Liff MH, Hoff M, Fremo T, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is associated with the patient global assessment but not with objective measurements of disease activity. RMD Open. 2019;5(1):e000912.

- Dohrn IM, Kwak L, Oja P, et al. Replacing sedentary time with physical activity: a 15-year follow-up of mortality in a national cohort. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:179–186.

- Statistics Norway. Arbeidskraftundersøkelsen: Statistisk Sentralbyrå. 2021. Available from: https://www.ssb.no/arbeid-og-lonn/sysselsetting/statistikk/arbeidskraftundersokelsen.

- Statistics Norway. Tidsbruksundersøkelsen: Statistisk Sentralbyrå. 2021. Available from: https://www.ssb.no/kultur-og-fritid/tids-og-mediebruk/statistikk/tidsbruksundersokelsen.

- Kjeken I, Bø I, Rønningen A, et al. A three-week multidisciplinary in-patient rehabilitation programme had positive long-term effects in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(3):260–267.

- Bearne LM, Byrne AM, Segrave H, et al. Multidisciplinary team care for people with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(3):311–324.

- Uhlig T, Bjørneboe O, Krøll F, et al. Involvement of the multidisciplinary team and outcomes in inpatient rehabilitation among patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:18.

- Berdal G, Bø I, Dager TN, et al. Structured goal planning and supportive telephone followup in rheumatology care: results from a pragmatic stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70(11):1576–1586.

- Cott CA. Client-centred rehabilitation: client perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(24):1411–1422.

- Berdal G, Smedslund G, Dagfinrud H, et al. Design and effects of supportive followup interventions in clinical care of patients with rheumatic diseases: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67(2):240–254.

- Valaas HK, Hildeskår J, Hagland AS, et al. Follow-up care and adherence to self-management activities in rehabilitation for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases – results from a multicentre cohort study. Disabil Rehabil [Submitted article]. 2021.

- Waddell G, Burton K, Aylward M. Work and common health problems. J Insurance Med. 2007;39(2):109–120.

- Hammond A, O’Brien R, Woodbridge S, et al. Job retention vocational rehabilitation for employed people with inflammatory arthritis (WORK-IA): a feasibility randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):315.

- Boonen AV, Butink M, Webers C, et al. Points to consider when supporting persons with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases to participate in healthy and sustainable paid work. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(Suppl 1):101.

- Fayed N, Cieza A, Edmond Bickenbach J. Linking health and health-related information to the ICF: a systematic review of the literature from 2001 to 2008. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(21–22):1941–1951.

- Garfield S, Clifford S, Eliasson L, et al. Suitability of measures of self-reported medication adherence for routine clinical use: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:149.

- Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: status, limitations, and future directions. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71 (Suppl 2):1–14.

- ICF Illustration Library. English version. Available from: http://icfillustration.com/icfil_eng/top.html