Abstract

Background and purpose

Chronic pain is a major reason for sick leave worldwide. Interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs (IPRPs), workplace interventions, and stakeholder collaboration may support patients in their return to work (RTW). Few studies have examined stakeholders’ experiences of important components in the RTW rehabilitation process for patients with chronic pain, especially in the context of IPRP. This study explores and describes stakeholders’ experiences with stakeholder collaboration and factors related to RTW for patients with chronic pain who have participated in IPRP.

Methods

Six focus groups, three pair and four individual interviews were conducted with a total of 28 stakeholder representatives from three societal and three health care stakeholders. Data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Results

The participants revealed that stakeholder collaboration and a tailored RTW rehabilitation plan were important strategies although they noted that these strategies were not working sufficiently efficient as presently implemented. The different stakeholders’ paradigms and organizational prerequisites were described as hindrances of such strategies and that the degree of tailoring depended on individual attitudes.

Conclusions

More knowledge transfer and flexibility, clearer responsibilities, and better coordination throughout the RTW rehabilitation process may increase the efficiency of stakeholder collaboration and support for patients.

Stakeholders need to have a close dialogue initiated before IPRP to be able to reach consensus and shared decision making in the RTW rehabilitation plan throughout the RTW rehabilitation process.

Individually tailored solutions based on a thorough assessment of each patient’s work ability and context are identified during IPRP and shall be included in the shared RTW rehabilitation plan.

The responsibilities of the stakeholders need to be clarified and documented in the RTW rehabilitation plan.

The role of RCs should be developed to improve the coordination throughout the patients’ RTW rehabilitation process.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Chronic pain negatively affects health and the ability to perform work and routine activities. In addition, chronic pain often leads to distress or poor mental health [Citation1,Citation2]. In Sweden [Citation1] and other European [Citation2,Citation3] countries, about 20% of the adult population report living with chronic pain. As chronic pain causes many biological, psychological, and social obstacles to work [Citation4], it can cause long-term sickness absence and return to work (RTW) rehabilitation beyond medical rehabilitation programs [Citation5,Citation6], effects that result in expenses for people and societies around the world. In Sweden, musculoskeletal pain is the second most common reason for sick leave, after psychiatric-related and stress-related diagnoses [Citation7]. Long-term sickness absence is also associated with lower disposable income for the disabled person over time [Citation8].

Strategies to support people with chronic pain in their RTW may involve both clinical and occupational interventions [Citation9], early contact between the employer and the employee on sick leave, early RTW with modified work tasks when needed, supervisors trained in work disability prevention and RTW planning, communication between employer and health care providers, and the presence of an RTW coordinator [Citation10]. Multiprofessional bio-psycho-social interventions – i.e., Interdisciplinary Pain Rehabilitation Programs (IPRPs) – to some extent can effectively treat patients with chronic pain and strengthen their ability to RTW [Citation6,Citation11–13]. One efficient strategy may be to develop an action plan that is tailored, coordinated, action-oriented, and implemented in close collaboration with involved stakeholders [Citation14]. Furthermore, interventions involving the workplace seem to be more effective supporting RTW than interventions not involving the workplace [Citation15,Citation16].

As RTW rehabilitation is a complex process involving a myriad of stakeholders, stakeholder collaboration is one important factor for supporting people on sick leave to RTW [Citation5,Citation15,Citation17–20]. Different stakeholders have different roles in the RTW rehabilitation process. To make the RTW rehabilitation process as smooth and efficient as possible, it seems important that the roles are clear and that all stakeholders form a cohesive team with the same goals throughout the process. Stakeholders who may take part in the RTW rehabilitation process include the person on sick leave, employers (e.g., senior management, supervisors, and co-workers), union representatives, physicians, rehabilitation clinicians, RTW coordinators, and insurers [Citation17,Citation21]. The communication between stakeholders is important albeit difficult. It is difficult to find consensus about goals and strategies because stakeholders have different paradigms, assumptions, regulations, and motivating factors [Citation21–23]. For example, Seing et al. identified three perspectives on work ability represented in a Swedish context of RTW stakeholders – i.e., a medical perspective, a workplace perspective, and a regulatory perspective [Citation22]. In addition, stakeholders may also have different communication styles [Citation23] and it may be difficult and time-consuming to connect [Citation24]. Furthermore, stakeholders experience that a lack of communication and collaboration can delay RTW interventions and ultimately RTW [Citation19,Citation23,Citation25]. The RTW coordinator should facilitate communication between the different stakeholders and guide the process through application of RTW protocols [Citation21], and both supervisors and rehabilitation clinicians can act as coordinators to facilitate the RTW rehabilitation process [Citation18].

In Sweden, there has been a recent push to include more RTW interventions such as stakeholder collaboration in the health care, including more communication between health care clinicians and employers [Citation26]. A new law regulates the presence and the responsibility for coordination of rehabilitation of people on sick-leave within Swedish health care [Citation27]. Furthermore, the Swedish government has initiated an investigation into how to improve collaboration between stakeholders in the RTW rehabilitation process for people on sick leave [Citation28]. Today, stakeholder collaboration is seen as an important ingredient in the RTW management of patients with chronic pain. IPRP often aim for RTW, but it is unclear to what extent RTW interventions such as stakeholder collaboration are included in the program. Over the last 10 years, researchers have increased their focus on strategies for RTW rehabilitation, the stakeholder’s roles, and how to efficiently collaborate [Citation29]. In spite of this increased focus, more knowledge is needed on how to support people with chronic conditions in their RTW rehabilitation process and on how to efficiently collaborate [Citation30]. Patients’ views of important factors for RTW and stakeholder collaboration have been described in a qualitative study. One important factor highlighted by the patients is more efficient stakeholder collaboration [Citation31]. Though, few studies have investigated stakeholders’ experiences of important components in the RTW rehabilitation process for patients with chronic pain, especially in the context of IPRP. To this end, this study explores and describes stakeholders’ experiences with stakeholder collaboration and factors related to RTW for patients with chronic pain who have participated in an IPRP.

Methods

This explorative interview study was designed to conduct focus groups with participants representing six different stakeholders. The stakeholders were involved in RTW rehabilitation process for patients with chronic pain who had participated in an IPRP. Specifically, the participants came from three Society stakeholders – the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA), The Swedish Public Employment Service (SPES) and employers, and three Health Care Stakeholders – Occupational Health Service (OHS), Rehabilitation Coordinators (RC) from primary care, and professionals (physicians and occupational therapists) working with IPRP.

Study context – the Swedish Sickness Insurance System

In Sweden, sick leave benefits may be granted at 25, 50, 75, or 100% of full work ability. The SSIA is responsible for social insurance, including assessing work ability (i.e., the eligibility to receive sick leave benefits and to what degree after 14 days of sick leave). From the first day of sick leave until day 14, the sickness benefit is paid by the employer: for days 15–90, eligibility is assessed in relation to the patient’s ordinary work task; for days 91–180, eligibility is assessed in relation to all work tasks that may be offered at the work place; and from day 181, eligibility is assessed in relation to any work task in the employment market. Including assessing work ability and the eligibility to achieve sick leave benefit, the SSIA also assesses the need of RTW interventions and coordinates the overall RTW rehabilitation process with other stakeholders [Citation32]. Several stakeholders are involved in the RTW rehabilitation process for patients with chronic pain in Sweden. The health care system is responsible for medical rehabilitation such as IPRPs. In both primary and specialized care, RCs coordinate health care interventions for patients with sickness absence. Patients participating in IPRP may have contact with an RC before and/or after the IPRP. In relation to the SSIA coordination, the RC coordination is more focused on personal support and coordination of interventions and professionals from a health care perspective [Citation27]. The employer is responsible for work rehabilitation, which includes adapting the work tasks and the workplace to the employee’s limitations. Often, the employers have an agreement with OHS to seek support for their rehabilitation responsibilities. SPES is obligated to offer support to unemployed patients or patients who are unable to return to their previous work. SPES may assess the patient’s work ability and help the patient find new suitable or adapted work [Citation32].

Participants

A purposive, group characteristics sampling method was used as this method creates an information-rich group that can reveal important patterns of a phenomenon [Citation33]. Stakeholder representatives were identified who had been active in stakeholder collaboration during IPRP at one of two pain clinics in two geographical regions (further called region A and region B) in south-eastern Sweden. The stakeholder representatives were chosen because they had the experience that would enable them to discuss and describe experiences relevant to the aim of the study. All the participants had experience with the RTW rehabilitation process for at least one patient with chronic pain who had participated in an IPRP. Occupational therapists working with work interventions during IPRP provided a list of stakeholder representatives from the stakeholders they had been in contact with during IPRP in the previous year. An email was sent to each representative on the list with the same information and a request to participate. Some representatives answered by email. A reminder email was sent to those who did not answer and then the representatives were contacted by phone. Information about the study was sent by email to responsible managers within IPRP at the SSIA and SPES. This contact was done to firmly establish the study within the organizations where several employees had a request to participate. Of the 68 representatives contacted by email, 32 agreed to participate. Of these, four representatives dropped out on the day for the interview due to work activities or sickness. Before starting the interviews, the participants provided written informed consent. They were informed that all the material would be handled with confidentiality and all participants were also asked to keep the content of the interview confidential.

The objective was to gather representatives from different stakeholders in each focus group to encourage different viewpoints and create dynamic discussions. According to Patton, focus groups are not intended to create consensus or to find disagreements but to share experiences in the context of other views [Citation33]. When a representative had agreed to participate, time and place for a focus group was offered. When a representative did not have the possibility to attend any of the focus groups, an individual interview was scheduled. Six focus group interviews with three participants in each group were conducted. In addition, three pair interviews and four individual interviews were conducted ().

Table 1. Number of participants, stakeholder representatives, and drop-out in each interview.

In total, 28 representatives participated, 14 representatives from society stakeholders and 14 representatives from health care stakeholders ().

Table 2. Number of participants from each stakeholder.

Data collection

An interview guide with open-ended questions was used to keep focus on the aim and make sure that important issues were discussed during the interviews [Citation33]. The interview guide consisted of three themes: (1) stakeholder collaboration, facilitating factors, and development needs; (2) important factors for support of patients in their RTW rehabilitation process; and (3) the role of IPRP in the stakeholder collaboration and RTW rehabilitation process. The interview guide included a few open questions addressing each theme. It was developed by experienced researchers and clinicians (all four authors) in collaboration with a patient research partner. Before starting the interviews, the participants were informed about the aim of the study and the three themes of the interview. They were asked to openly discuss their experiences in relation to the aim and the themes with each other. According to Krueger and Casey, a focus group interview should start with a question that is rather easy for all participants to answer and that underscores the common characteristics of the participants [Citation34]. Therefore, each interview started with the same request: Tell us about how you work with stakeholder collaboration today. After the discussions had started, the questions in the interview guide were asked when needed to keep focus on the aim of the study. Two researchers participated in the focus group interviews and in two of the pair interviews. One had a more active role as a moderator, asking questions during the discussions [Citation34]. The other acted more as an observer, taking notes and making sure the discussions focused on the aim of the study and that all participants had an opportunity to describe their experiences (FS, GL, and MB were involved as either moderator or observer). One pair interview and the individual interviews were conducted by one researcher alone (FS or GL). The interview procedure was the same for the pair interviews and the individual interviews as for the focus group interviews. They started with the same question and the guide was used to keep focus on the aim of the study. Overall, the interviews were fluid and the participants rather independently discussed and described their experiences. However, some participants were more talkative than others and a few more follow-up questions were used in the individual interviews. The interviews lasted between 40 and 80 min.

The focus group interviews, the pair interviews, and one of the individual interviews took place at the local pain clinic or the hospital where the pain clinic was located. One participant joined the focus group digitally by Skype. Three of the individual interviews took place at the participants’ workplace. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a skilled secretary. A patient research partner from the Swedish Rheumatism Association was involved in the preparation of the interview guide and participated in one of the pair interviews.

Analysis

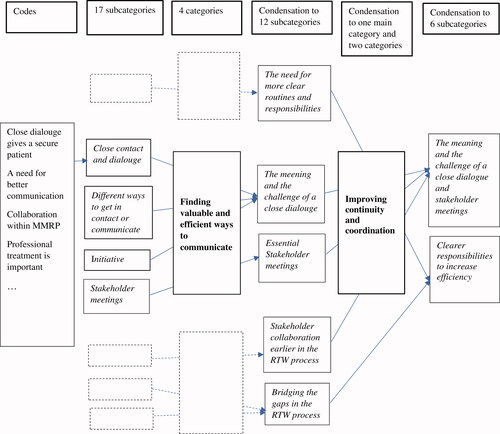

A qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach was used to analyze the data. That is, the transcribed interviews were analyzed with focus on its content, searching for patterns in the text and categorizing rather than interpreting the content [Citation33]. The analysis was performed in four steps. First, all interviews were read through several times. To control the transcription of the data, all interviews were listened to while the transcriptions were read and corrected where there was inaccuracy in the transcriptions. Second, the coding of the material started by reviewing all the interviews again. In this step, the text was divided into smaller parts with similar content. Some parts consisted of a couple of lines and other parts of larger pieces of the text. The core content of each text part was identified and coded. The codes were named using the participants’ own words as much as possible. Two of the researchers (FS and GL) worked with the data independently, double-coding all interviews, before discussing the codes and arriving at agreement. Overall, there was agreement from the beginning. However, after the discussions, some names of codes changed and some codes were combined if their content seemed redundant. Third, the codes were further condensed and sorted into subcategories by going through the codes and sorting similar codes together into subcategories, first independently by one researcher (FS) and then in discussion with another (GL) to reach consensus. In this step, 17 subcategories were identified. The subcategories were named to label the content of each subcategory. Fourth, the last step, focused on condensing the results. The subcategories were compared and abstracted – that is, the subcategories with similar content were sorted into categories. In this phase, four categories and twelve subcategories emerged. The two researchers (FS and GL) read and discussed the data and the categories again, a process that resulted in one main category, two categories, and six subcategories (). The four authors repeatedly discussed the emerging subcategories and the categories until consensus was reached. When consensus was reached, the interviews were reread by the first author (FS) to verify the findings.

Figure 1. Extract from the analysis process. Examples related to the category “Improving continuity and coordination”, from first codes to final categories and subcategories.

Figure 2. Overview of categories and subcategories.

To facilitate the analysis process, the Open Code 4.0 Umeå software [Citation35] was used in steps 2 and 3. The transcript of the text was transferred to the Open Code, where the coding and categorizing into subcategories took place.

Ethics

Participants were informed about the aim and the procedures of the study, including that participation in the study was voluntary and that they could withdraw participation at any time. Informed written consent was provided by the participants before the interviews. All procedures followed the Helsinki protocol [Citation36]. Participants were asked not to mention any patient names during the interviews. The data were handled with confidentiality and stored on a secure database. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Dnr. 2016/184-31).

Results

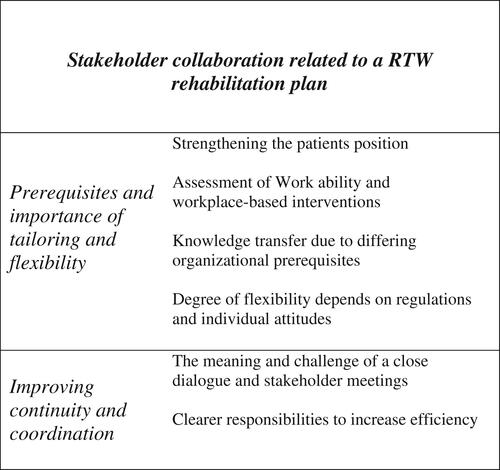

One main category – stakeholder collaboration related to an RTW rehabilitation plan – and two categories – prerequisites and importance of tailoring and flexibility and Improving continuity and coordination – were identified ().

Stakeholder collaboration related to an RTW rehabilitation plan

When discussing the RTW rehabilitation process, participants from all stakeholders identified stakeholder collaboration as key support for patients. Although the stakeholder collaboration was viewed as important, it was not sufficiently efficient in practice. Many components were mentioned as important for RTW rehabilitation and efficient collaboration between stakeholders and patients. An RTW rehabilitation plan, discussed in relation to the stakeholder collaboration, was an example all stakeholders recurrently acknowledged. The stakeholders experienced that different types of RTW plans are currently used, but often they are not sufficiently concrete, communicated and accepted to be efficient in practice. Participants from both society and health care stakeholders argued that these plans need to include rehabilitation goals and be sufficiently concrete to clarify each step of the RTW rehabilitation process:

… Now this is step 1, then this can be step 2, that you piece together a map, a puzzle with the patient //…// step 1, step 2, step 3, good, and you can see that they become more relaxed and calm down when they know the next step. (SPES, woman, FGI1, region A)

Furthermore, the participants noted that a solid plan needs to be anchored with all involved stakeholder representatives and collaboration is important with active involvement of the patient. The involvement of all stakeholders was emphasized by an RC:

… that you have the planning so that plan both patients, the Social Insurance Office, employers or the Employment Agency and we as staff need to have and work with the same. (RC, woman, FGI5, region B)

Prerequisites and importance of tailoring and flexibility

Strengthening the patient’s position

Both society and health care stakeholders experienced that a patient’s ability to reach RTW goals improved when solutions were identified in relation to a patient’s unique problems and work situation. What is useful for one patient may not be useful for another, and the participants suggested that the patients be given the opportunity to test different strategies so they can evaluate which strategies would work best for them:

That’s probably how it is. With so many patients with this challenge, there is probably no single solution. We are talking about individuals. Situationally adapted for everything. (Employer, man, FGI3, region A)

The participants noted that because patients often experience pain, are fragile, and are uncertain, it is important to focus the support and the collaboration on the patients’ needs. The participants generally experienced that when patients are involved in the planning of strategies and interventions, they become more motivated and ready for change. Both the society and health care stakeholders agreed that IPRP helps patients generate more knowledge and strategies, preparing and motivating them for the next step, further strengthening the patients’ position in the RTW rehabilitation process. In addition, according to the participants, encouraging the patients’ own responsibility prepared, motivated, and strengthened their position in the RTW rehabilitation process:

Then you have to have the patient also pushing their own rehabilitation so that they get the most out of it, so it is to be the patient’s plan. (RC, woman, FGI5, region B)

Foremost, participants from the society stakeholders discussed the importance of making demands on the patients to drive their own rehabilitation process. However, all the stakeholders experienced that it was sometimes hard for the patients to fulfill their responsibility as they did not have the strength or the knowledge to do so. To avoid uncertainty and achieve confidence, the participants discussed the importance for an RTW rehabilitation plan, which presumably would strengthen and empower the patients.

Assessment of work ability and workplace-based interventions

Participants from the society stakeholders wanted a patient’s work ability to be assessed more thoroughly than it is presently done, to be the foundation for tailored solutions, and to provide the right level of sick leave compensation. They expressed that measuring work ability may help them find the right level of sick leave compensation for each patient, which, according to participants from both society and health care stakeholders, may be important for patients to feel secure and to focus on the rehabilitation process rather than their unstable economic position. When these assessments were unclear or lacking, the society stakeholders found it hard to do their work. The society stakeholders and the RCs desired more documentation on work ability and prerequisites for further RTW rehabilitation at the end of IPRP. They found that after an IPRP, the team had a good overall picture of the prerequisites that need to be documented and communicated to a higher degree:

…Now what do you see happening next from here (IPRP)? Should you actually continue with work training and what do you think? Should you aim for a full-time job or are there lasting health problems so that you should not be too ambitious, or? (SSIA, woman, PI1, region B)

The participants described the sickness certificates as important documents. The healthcare stakeholders experienced difficulties writing those certificates in line with the regulations of the SSIA, the SSIA found it difficult to interpret the formulations, and suggestions were made to standardize certificates to overcome these difficulties. Another suggestion was to discuss and collaborate to reach consensus about the degree of sick leave for each patient.

Furthermore, the participants argued that the question about what work and work tasks may be appropriate for each patient needs to be raised. If possible, the patient would be given the opportunity to try different strategies until they find what works best for them:

… so it’s about finding the right possible types of work, looking at what are reasonable working hours, and looking at the pace of the work, the content of the work, all this. To find what adjustments are needed in the form of physical adjustments, but also when it comes to work pace, new ways of working, thinking about how to organise the working day with breaks, how to place the person if they can’t work full time but maybe work 50% //…// To have the opportunity to try things until you find what works. (SPES, woman, FGI2, region A)

When patients are employed, the interventions need to be implemented at the workplace as much as possible. According to the participants, this may increase the possibilities of individual adaptations. Making a workplace visit during IPRP was experienced as valuable for the implementation of concrete and tailored interventions at the workplace. However, making workplace visits was also experienced as too time-consuming in practice:

If there was more time, workplace visits would be really good. There is a lot you could do. (IPRP, woman, FGI5, region B)

Knowledge transfer due to differing organizational prerequisites

The participants identified several major barriers to stakeholder collaboration and implementation of an accepted tailored plan for RTW: stakeholders have different rules and regulations, stakeholders have different aims and assignments, and stakeholders have different interpretations of the important factors for the RTW rehabilitation process. For example, a patient’s work ability has different interpretations depending on the stakeholder’s view. As the participants put different demands on the patients, it may be hard for patients to reconcile how to interpret the stakeholders’ demands:

We have also been told to back away a bit from coordinating and force the employers to take steps, which means that if you compare to the current situation, the SSIA used to take the employer’s place and do some things that were the employer’s responsibility. If you look at the regulations, the SSIA should actually be here and the employer there instead. Now the SSIA has backed away and the employer has not realised that they must get onboard. So right now I experience a fairly large gap between the employer and the SSIA. (SSIA, man, FGI2, region A)

All the stakeholders described a lack of knowledge concerning different organizational prerequisites and each other’s roles in the RTW rehabilitation process. They described situations where the lack of knowledge could lead to wrong expectations. For example, the SSIA could expect an assessment of work ability or that the patient be healthy during IPRP. The health care stakeholders, in turn, could make rehabilitation plans with solutions outside the regulations of the sickness insurance system regulations:

It could be that we came up with a plan (IPRP) and thought //…// then the SSIA says that you can’t do that because it goes against our rules or something like that. (IPRP, woman, FGI4, region B)

The society stakeholders described that sometimes they did not have enough knowledge about pain, IPRP, and appropriate solutions to meet the needs of a patient with chronic pain. For example, the employer participants expressed uncertainty concerning how to adapt the workplace and work tasks. The participants discussed that today there is an insufficient transfer of knowledge between the different stakeholders. They also discussed different ways to make this better, for example, by professionals from IPRP holding a “crash course” for the society stakeholders in need of more knowledge concerning pain rehabilitation and by involving more stakeholder representatives during IPRP, both in making rehabilitation plans and participating in lectures to increase knowledge and understanding for the patient’s needs:

She invited me to this program (IPRP) so I could take part and listen to what it is about, what it meant. There was a psychologist but also a therapist who described, actually explained, what it was about, so I got a good, very good understanding of that part. (Employer, man, FGI3, region A)

Degree of flexibility depends on regulations and individual attitudes

Participants from all stakeholders talk about the need for flexibility in relation to the application of different rules and regulations in the sickness assurance system. Several participants express that the SSIA regulations are so rigid that it is hard to make tailored solutions that will efficiently support RTW. Furthermore, some participants experienced stakeholder reconciliation meetings being about information concerning the rules and regulations more than about collaboration to help the patient.

According to the participants, different regulations, officers, and professionals are important for the successful implementation of a tailored RTW rehabilitation plan. The participants describe a great variance in how flexible different officers and professionals act in relation to the rules and regulations: some officers are more focused on tailored solutions and some are more focused on applying the regulations in the right way. Some participants described different ways of acting within their own stakeholder organization:

[…] some are so stuck in the regulations that they do not try to find ways. They only see that ‘this is what the regulations look like’. (SSIA, man, FGI2, region A)

It depends so much on which case officer it is, and this applies of course to both authorities (SSIA and SPES) […] this is the explanation some hear//…//you also get suggestions on ways forward, while others just hear ‘no’. So, it is very based on the individual. (SPES, woman, FGI2, region A)

According to the participants, this may lead to different assessments, solutions, time frames, and treatments. Participants from all stakeholders wanted more “rounded corners” and a flexible approach to meet the needs of the patient.

Improving continuity and coordination

The meaning and challenge of a close dialogue and stakeholder meetings

All the stakeholders revealed that close dialogue is something that participants consider important for supporting patients during the RTW rehabilitation process. To be open-minded and to openly discuss solutions for the patient are described as important. There are different opinions on how frequent the dialogue should take place, but they agree about the importance on finding efficient forms for communication. When one stakeholder representative notices some sort of need, it is important for all stakeholders to know about this and to be involved in the plan. However, the participants found it challenging to find efficient ways to communicate. They believed efficient communication was time consuming as it is difficult to establish a collaborative and communicative relationship with different stakeholder representatives. Therefore, the participants suggested more clear, common routines for communication and assigning a contact person to make the communication more efficient:

It would have been easier if there had been a person at the SSIA who could coordinate all this so you didn't have to find 20 different people or however many it was //…// we spend a lot of time looking for people and that is a pity. (IPRP, woman, FGI5, region B)

Participants from all stakeholders described positive experiences of stakeholder reconciliation meetings. To gather involved stakeholder representatives and the patient, to discuss the prerequisites, and to formulate a tailored plan for RTW rehabilitation were described as essential for reaching consensus and making the patient comfortable and confident in the plan. Most participants preferred physical meetings for discussing and making plans but described that shorter check-ups could be made over telephone or through video conferencing. Some participants such as employers and RCs suggested more frequent stakeholder meetings and argued that although meetings may be experienced as time consuming, time is saved in the long run when more efficient plans and consensus about the patients RTW plan are implemented:

The best thing would be to meet everyone together. That you get to hear the same thing at the same time about what different areas of expertise say and think. I understand that it is difficult to bring together all these people to a single meeting, but I still think that in the end when you look at //…// how much time each individual person has spent in this process, I am completely convinced that you could make back 10 times the investment. (Employer, man, II4, region A)

Several participants viewed IPRP as a good forum for the stakeholder representatives to meet. They argued that at least one meeting should be held during the IPRP. However, some participants suggested more meetings, for example, before starting the IPRP to set up a plan and make the prerequisites clear for the patient and the stakeholders:

What you would have to cover was a planning meeting before the programme to decide […] ‘now we are going to spend this money on this person. Now we want to do most of this’ […]. (Employer, woman, II1, region A)

A common experience among the participants was that generally the collaboration had started too late in the RTW process. Finding ways to collaborate earlier seemed important for increasing continuity and efficiency. Some participants, such as those from health care stakeholders and the SSIA, discussed that the employers need to act early and that OHC should have made appropriate interventions before the IPRP. There were also suggestions that the RC be involved earlier, in the very beginning of the RTW rehabilitation process, to improve the dialogue and the continuity:

It would be good if we were asked before, too. What has happened? Too often, before they get to IPRP, it is common as you say, most often the person has been on sick leave several times before. (RC, woman, FGI3, region A)

Clearer responsibilities to increase efficiency

Some participants described the IPRP as an intensive, short protective period when the patients learn to assess their weaknesses and strengths so as to develop strategies to better handle their work and everyday life. However, many of the stakeholders experienced that after the IPRP it was hard for the patients to keep up what they had learned. Therefore, they suggested more follow up and continuity in stakeholder reconciliation meetings to support the patients’ implementation of their RTW plan. The participants related that it is often the case that patients have to wait a long time for decisions regarding their sick leave benefits from the SSIA, work training arrangements from the SPES, and workplace interventions to be implemented:

Maybe we have come far (with the patient), and then the bureaucracy slows down the whole rehab process, because that’s when there are delays, delays with the employment service, the patient does not start the work trial, the case officer is not available. There is no one coordinating everything or staying in touch with the patient or informing the patient or placing small demands on the patient. We've had a few who have improved during the IPRP and then nothing happens. (IPRP, man, PI2, region A)

According to the participants, there are some clear responsibilities in the RTW rehabilitation process such as the SSIAs responsibility for coordinating the RTW process and the employer’s responsibility for work rehabilitation. Although there are some formal responsibilities, several participants, primarily from the society stakeholders and RCs, experienced some uncertainty about their responsibility in relation to the other stakeholders such as the degree the employers fulfill their responsibilities concerning RTW rehabilitation, whether the employers have enough knowledge about their responsibilities, and whether their responsibilities are viewed as mandatory:

I have noticed that the employer feels that it is a bit unclear. It feels unclear to the employer, but we now see with the new proposals //…// that the employer has a greater responsibility and must invest resources at a much earlier stage, at which point we come with support through the OHC. //…// I really think that it requires a good dialogue with the employer, that the employer realises both their responsibility and what can be achieved with this collaboration. (OHS, woman, FGI1, region A)

Participants from all stakeholders agree there is a need for clearer coordination and someone to hold the RTW rehabilitation process together, making the RTW interventions and the stakeholder collaboration tighter and more efficient for the patient. Employer participants discussed the need for some kind of “project manager” who has the responsibility and mandate to coordinate all stakeholders with the aim of implementing an efficient tailored RTW plan for the patient. According to participants from both health care stakeholders and society stakeholders, there are RC in primary care who play this role.

Discussion

Keep working on stakeholder collaboration related to an RTW rehabilitation plan

In our study, participants from six stakeholders discussed and described how they experience stakeholder collaboration, the role of IPRP, and important factors for RTW for patients with chronic pain. This study produced two main results with respect to the importance of stakeholder collaboration in relation to RTW rehabilitation plan: the RTW rehabilitation process needs greater support to strengthen the patients’ position and collaboration among stakeholders is difficult due to different organizational prerequisites and lack of flexibility and coordination. The RTW rehabilitation plan was described as an important tool to strengthen the patients’ position by tailoring solutions for the patients or coordinating the RTW rehabilitation process. Earlier studies on patients with musculoskeletal disorders found that the use of an action-oriented, tailored, and well-coordinated RTW rehabilitation plan when implemented in close collaboration with relevant stakeholders [Citation14,Citation17], specifically in the early phase of sick leave [Citation14], could be useful. In addition, some qualitative studies have explored stakeholder communication and collaboration in the RTW rehabilitation process for patients with long-term sick leave due to chronic pain and other diagnoses. Different stakeholders such as compensation board representatives, employers, union members, RTW coordinators, and health care professionals have described the importance of good collaboration. However, in practice, they all experience a lack of communication and coordination that may result in delay of RTW for the patients [Citation19,Citation23,Citation25]. Friesen et al. [Citation19], relying on group interviews and individual interviews with different stakeholders (named above), found that the different stakeholders had an overall agreement regarding the different facilitating factors and barriers for RTW. In our study, the stakeholders consistently described similar experiences. In addition, our study found that the stakeholders experienced the plan and a close dialogue concerning the plan as valuable. A difference between our study and earlier studies was the participation of SPES, as the discussions concerned even unemployed patients, which makes the results of our study cover a broader patient group than previous studies. Furthermore, the stakeholders in our study raised the importance of physical meetings and highlighted that even though it might seem time-consuming to meet, such meetings actually save time in the long run. Franche et al. also highlighted the importance of physical stakeholder meetings. The discussions in their own right may contribute to increased knowledge and understanding concerning the different stakeholders’ roles, which may increase the tolerance for each other and the involvement in stakeholder collaboration [Citation21]. Nonetheless, it is hard for the stakeholders to practice what they think are the best strategies. The results of our study add to knowledge that supports the continuing work to improve the prerequisites to apply stakeholder collaboration related to an RTW rehabilitation plan.

Different paradigms, responsibilities, and a bureaucratic sickness insurance system

Although we acknowledge the importance of an RTW plan, efficient communication, and stakeholder collaboration, these practices are rarely applied. How come? In the literature, four stakeholder perspectives on work disability prevention for workers with musculoskeletal pain have been described [Citation37–39]: (1) the person with work disability, representing the view of a lifeworld, trying to manage life with chronic pain; (2) the health care system, representing a medical and rehabilitating view with the goal to increase the patient health; (3) the workplace system, representing a view of production with an emphasis on economic goals; and (4) the legislative/insurance system, representing a bureaucratic system with a focus on the right to achieve compensation. In our study, the participants discussed that employers tend ignore their responsibility concerning work rehabilitation and they also discussed the bureaucratic approach from SSIA officers. In the light of the stakeholder perspectives described above, these experiences can be better understood as being a part of a larger systems approach. Also, according to Stahl et al., different stakeholders have different organizational structures, paradigms, and prerequisites, and they view work ability in different ways. Collaboration between stakeholders may be hard because of the strict bureaucratic sickness insurance system [Citation40], and stakeholder meetings might maintain rather than overcome organizational differences. It might be hard to adopt a comprehensive view as all stakeholders hold their own perspective and sometimes negotiate about their responsibilities [Citation22]. Ståhl et al. [Citation41] described how socio-political challenges may affect the implementation of work disability prevention strategies. Work disability prevention should include a high level of collaboration between stakeholders and of well-coordinated actions, spanning over different organizational and interorganizational contexts.

In Sweden, the policies have changed over the last decades with considerably more restrictive regulations. These changes often have resulted in policies that do not pay enough attention on the workplace system, employer responsibilities, and multi-stakeholder approaches [Citation41]. Perhaps, this is one part of the explanation. The stakeholders in our study generally experienced unclear responsibilities and specifically that the employers’ responsibilities are sometimes unclear or that some employers do not have the knowledge to fulfill their responsibilities. For employed patients, the employer is an urgent actor who needs to have a dialogue with the patient and other relevant stakeholders to achieve efficient RTW [Citation10,Citation17,Citation21]. Employers may be supported by specific tools to manage their responsibilities. The use of a dialogue-based workplace intervention, including Convergence Dialogue Meetings (CDM), has been developed and qualitatively evaluated with positive experiences for patients with stress-related disorders and their employers [Citation42,Citation43]. Patients with acute/subacute back and neck pain returned to work faster when CDM was added to structured physiotherapy in primary health care in Sweden [Citation44]. Such tools need to be developed and tested for patients with chronic pain and their employers.

How to improve coordination throughout the RTW rehabilitation process

Another important part of the results of our study was the lack of coordination throughout the RTW rehabilitation process and the need to strengthen this coordination. One employer requested a case manager and other stakeholders raised the possibility to strengthen the role of the RC to hold the stakeholders and the RTW rehabilitation process together. According to Hubertsson et al. [Citation45], patients with musculoskeletal disorders may experience both coherent and fragmented interaction with the social insurance agency and health care. Coherent interactions contributed to recovery and a feeling of being recognized as a person and receiving support. On the other hand, fragmented interactions were experienced as unsupportive, leading to a feeling of being alone in the process and lack of continuity that was disadvantageous to recovery and RTW [Citation45]. Both patients and different stakeholders in the RTW rehabilitation process experience lack of coordination and raise the importance of better structures and more focus on coordination [Citation18,Citation21]. In February 2020, the Swedish government established a new law with the aim of regulating the presence and the responsibility of RCs both in primary and specialized care [Citation27]. Hopefully, this will help satisfy the call for better coordination in the RTW rehabilitation process for patients with chronic pain. However, future research is needed that evaluates the implementation and compliance to the new law and how the new law affects stakeholders and RTW numbers.

Empowering patients

The participants in our study identified motivation, confidence, and a readiness for change as important patient factors to strengthen the patients’ role in the RTW rehabilitation process and stakeholder collaboration. Loisel et al. explored obstacles and facilitators that an RTW rehabilitation team perceived in their collaboration with different stakeholders such as employers and insurers. They found several obstacles and facilitators that affected collaboration such as motivational and organizational factors as well as actions and attitudes. The patient’s motivation, a positive but realistic attitude, and good coping strategies were perceived as facilitating factors for collaboration [Citation46]. In our study, several of these factors were also identified not only by representatives from an RTW rehabilitation team but also by participants form the different society and health care stakeholders. Motivation and other self-efficacy aspects such as pain self-efficacy belief [Citation47], confidence [Citation48], and RTW expectations [Citation49,Citation50] have also been raised as important factors in other studies. In our study, the stakeholders raised the importance of the patient’s responsibility to drive his or her own RTW rehabilitation process; however, the stakeholders in our study also described that if patients’ motivation and confidence are low, they might find it hard to drive their own processes and it might be hard for the stakeholder representatives to make patients a strong part of the collaboration. Cummings et al. found that patients with chronic pain may experience a low sense of self-efficacy, and there may be a tension between a willingness to endure a situation independently but at the same time feel that they cannot manage alone [Citation51]. When there is a need to rely on others, a positive relationship between the helpers and patient is required. However, several studies have shown that injured workers experience interactions with insurers negatively. They may experience unprofessional behavior as well as lack of knowledge and understanding and lack of possibilities to establish individual solutions. In addition, patients may feel stigmatized by stakeholders who often do not believe that they are sick or injured to the extent they deserve benefits, a lack of trust that leads to mental, social, and vocational consequences. The result of this negative cyclic relationship may worsen the problems instead of supporting the worker RTW [Citation52]. Professionals who express positive and supportive attitudes may improve patients’ motivation and self-confidence. Viewing the patients as legitimate partners may help patients move from passive to active participants in their RTW rehabilitation process [Citation53].

The stakeholders in our study described the importance of tailoring the interventions and solutions to meet the specific needs of each patient, such as finding manageable work tasks, working time, and working tempo adapted to the patient’s capacities. This approach may empower the patients and make them more confident, which in turn may facilitate RTW. Dekkers-Sánchez et al. identified the importance of matching guidance to an individual’s needs [Citation20]. In addition, some studies have found this may require tailoring in relation to changing symptoms, which are a part of living with chronic pain. That is, there is a need to tailor and adapt activity performance such as work activities to the problems and needs that surface during different periods [Citation54–56]. A fluctuating work status may be used as a strategy or occur as a consequence for different patients. Patients using fluctuating work status as a strategy have good knowledge about the regulations of the sickness insurance system, know their rights and obligations, and may control the interactions with stakeholders. They find strategies and take the responsibility for their work situation and rehabilitation. On the contrary, patients who have fluctuating work status as a consequence of their pain and different regulations seem to struggle more in their interactions with stakeholders and tend to take a more passive role in their RTW rehabilitation, relying on the stakeholders’ expertise and knowledge, resulting in little room for tailored and adapted conditions [Citation57]. Hence, there is a need to develop strategies in the RTW rehabilitation context that further empower the patients and give them the knowledge, strength, and confidence to take an active role in their RTW rehabilitation process, the most important part of the stakeholder collaboration.

Methodological considerations

The data collection method in our study was planned to be focus groups with one participant from each stakeholder in each focus group to let different stakeholder viewpoints meet, to see differences in perspectives, and to ensure dynamic discussions as recommended by Krueger and Casey [Citation34]. However, it was not possible to gather the participants this way. The composition of stakeholders in each focus group became secondary to just gathering different stakeholder representatives who could meet at the available times. In combination with late drop-outs, this resulted in focus groups with few participants. Despite the few participants in each focus group, there were rich discussions. Overall, the stakeholders met between two and five other stakeholders, and all met with both society and health care stakeholders. Altogether, the focus groups provided possibilities where the experiences from all stakeholders were discussed in relation to other stakeholders’ viewpoints, which was an important aim of the study. Combining the focus groups and the pair interviews with individual interviews had pragmatic reasons, as described by Lambert and Loiselle [Citation58]. The participants that were interested in participating but could not attend the focus groups were offered an individual interview at a time of their choosing. Foremost, this was current for employers. Although they did not discuss their experiences in relation to other stakeholders, their answers were fluid and reasoned. The content of the individual interviews was consistent with the content of the focus groups and pair interviews.

One possible limitation with this study is that one stakeholder is not represented, namely the person with chronic pain. Earlier studies [Citation17,Citation21] as well as this study highlight the importance of the person on sick-leave as an active part of the collaboration. However, the perspective of this important stakeholder has also been explored in another study [Citation31] that focuses on specific experiences of patients with chronic pain who have participated in an IPRP. In this way, the persons with chronic pain could speak about their experiences, as telling their experiences in the same room as the other stakeholders could have made them hesitant to tell the truth about their experiences with the collaboration.

The purposive group characteristic sampling method [Citation33] made sure that the participants had diverse experiences of stakeholder collaboration supporting patients with chronic pain RTW. However, there may be a selection bias [Citation34] due to an overrepresentation of participants with a special interest in stakeholder collaboration. There is a risk that the stakeholder representatives who declined to participate in the study do not value stakeholder collaboration in the same manner. The overall results of the study highlighted the importance of stakeholder collaboration and there was an overall agreement between the different stakeholders on this point.

Four researchers collaborated in all parts of the study, from design to report. For example, the analysis was performed by two of the researchers both independently and in collaboration. The subcategories and the categories were repeatedly discussed throughout the analysis by all four authors until consensus was reached. The use of multiple researchers may increase the credibility of a study [Citation59] and according to Patton, two or more researchers analyzing the data is a sort of analytical triangulation, which increases trustworthiness [Citation33]. Furthermore, a patient research partner contributed to the validation of the interviews and the trustworthiness of the results of the study.

Conclusions

Stakeholder representatives from both society and health care describe stakeholder collaboration related to an RTW rehabilitation plan as important for supporting RTW for patients with chronic pain who have participated in an IPRP. They highlight the need to empower the patients and strengthen their position in the RTW rehabilitation process. There is a further need for better coordinated and tailored solutions in the RTW plans and closer dialogue between the stakeholders. Today, the different stakeholders paradigms and organizational prerequisites may hinder solutions, and the degree of tailoring may depend on individual attitudes. More knowledge transfer, clearer responsibilities, and better coordination throughout the RTW rehabilitation process may increase the efficiency of the stakeholder collaboration and the support of the patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants who took part in the interviews in this study. We also thank our patient research partner, Jan Bagge from the Swedish Rheumatism Association, for scrutinizing and validating the data collection.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Harker J, Reid KJ, Bekkering GE, et al. Epidemiology of chronic pain in Denmark and Sweden. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:371248.

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):287–333.

- Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):e273–e283.

- Wynne-Jones G, Buck R, Porteous C, et al. What happens to work if you're unwell? Beliefs and attitudes of managers and employees with musculoskeletal pain in a public sector setting. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(1):31–42.

- Hellman T, Jensen I, Bergstrom G, et al. Returning to work – a long-term process reaching beyond the time frames of multimodal non-specific back pain rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(6):499–505.

- Fischer M, Persson E, Stålnacke B, et al. Return to work after interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation: one- and two-year follow-up based on the Swedish Quality Registry for Pain Rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(4):281–289.

- Försäkringskassan; 2020 [updated 2020 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.forsakringskassan.se/statistik/sjuk/sjuk-och-rehabiliteringspenning

- Wiberg M, Friberg E, Palmer E, et al. Sickness absence and subsequent disposable income: a population-based cohort study. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43(4):432–440.

- Williams RM, Westmorland MG, Lin CA, et al. Effectiveness of workplace rehabilitation interventions in the treatment of work-related low back pain: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(8):607–624.

- Institute for Work and Health. Seven ‘Principles’ for successful return to work; 2007. Available from: https://www.iwh.on.ca/sites/iwh/files/iwh/tools/seven_principles_rtw_2014.pdf

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h444.

- Brendbekken R, Eriksen HR, Grasdal A, et al. Return to work in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: multidisciplinary intervention versus brief intervention: a randomized clinical trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(1):82–91.

- Berglund E, Anderzen I, Andersen A, et al. Multidisciplinary intervention and acceptance and commitment therapy for return-to-work and increased employability among patients with mental illness and/or chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2424.

- Bültmann U, Sherson D, Olsen J, et al. Coordinated and tailored work rehabilitation: a randomized controlled trial with economic evaluation undertaken with workers on sick leave due to musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(1):81–93.

- Carroll C, Rick J, Pilgrim H, et al. Workplace involvement improves return to work rates among employees with back pain on long-term sick leave: a systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(8):607–621.

- van Vilsteren M, van Oostrom SH, de Vet HCW, et al. Workplace interventions to prevent work disability in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(10):CD006955.

- Durand MJ, Corbiere M, Coutu MF, et al. A review of best work-absence management and return-to-work practices for workers with musculoskeletal or common mental disorders. Work. 2014;48(4):579–589.

- MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche RL, et al. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(4):257–269.

- Friesen MN, Yassi A, Cooper J. Return-to-work: the importance of human interactions and organizational structures. Work. 2001;17(1):11–22.

- Dekkers-Sánchez PM, Wind H, Sluiter JK, et al. What promotes sustained return to work of employees on long-term sick leave? Perspectives of vocational rehabilitation professionals. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011;37(6):481–493.

- Franche RL, Baril R, Shaw W, et al. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: optimizing the role of stakeholders in implementation and research. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):525–542.

- Seing I, Stahl C, Nordenfelt L, et al. Policy and practice of work ability: a negotiation of responsibility in organizing return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(4):553–564.

- Russell E, Kosny A. Communication and collaboration among return-to-work stakeholders. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(22):2630–2639.

- Nilsing E, Söderberg E, Berterö C, et al. Primary healthcare professionals' experiences of the sick leave process: a focus group study in Sweden. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(3):450–461.

- Soklaridis S, Ammendolia C, Cassidy D. Looking upstream to understand low back pain and return to work: psychosocial factors as the product of system issues. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(9):1557–1566.

- Axén G. Mer trygghet och bättre försäkring – Parlamentariska socialförsäkringsutredningen SOU 2015:21; 2015. Available from: www.regeringen.se

- Lag om koordineringsinsatser för sjukskrivna patienter 2019:1297 (Law on coordination efforts for sick-leave patients). Sveriges riksdag, Socialdepartementet.

- Mandus F. SOU 2020:24 Tillsammans för en välfungerande sjukskrivnings- och rehabiliteringsprocess. In: Socialdepartementet, editor; 2020. Available from: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2020/04/sou-202024/2020

- Nastasia I, Coutu MF, Tcaciuc R. Topics and trends in research on non-clinical interventions aimed at preventing prolonged work disability in workers compensated for work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WRMSDs): a systematic, comprehensive literature review. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(22):1841–1856.

- Sabariego C, Coenen M, Ito E, et al. Effectiveness of integration and re-integration into work strategies for persons with chronic conditions: a systematic review of European strategies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(3):552.

- Svanholm F, Liedberg GM, Löfgren M, et al. Factors of importance for return to work, experienced by patients with chronic pain that have completed a multimodal rehabilitation program – a focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;1–9.

- Socialförsäkringsbalk 2010:110 (Social Insurance Code). Sveriges riksdag, Socialdepartementet.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2015.

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2015.

- The Open Code 4.03 Software program. Umeå: Umeå University; 2013.

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194.

- Loisel P, Durand M-J, Berthelette D, et al. Disability prevention. Dis Manage Health Outcomes. 2001;9(7):351–360.

- Loisel P, Buchbinder R, Hazard R, et al. Prevention of work disability due to musculoskeletal disorders: the challenge of implementing evidence. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):507–524.

- Lindqvist R. Vocational rehabilitation between work and welfare – the Swedish experience. Scand J Disabil Res. 2003;5(1):68–92.

- Stahl C, Mussener U, Svensson T. Implementation of standardized time limits in sickness insurance and return-to-work: experiences of four actors. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(16):1404–1411.

- Ståhl C, Costa-Black K, Loisel P. Applying theories to better understand socio-political challenges in implementing evidence-based work disability prevention strategies. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(8):952–959.

- Strömbäck M, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Keisu S, et al. Restoring confidence in return to work: a qualitative study of the experiences of persons with exhaustion disorder after a dialogue-based workplace intervention. PLOS One. 2020;15(7):e0234897.

- Eskilsson T, Norlund S, Lehti A, et al. Enhanced capacity to act: managers' perspectives when participating in a dialogue-based workplace intervention for employee return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31(2):263–274.

- Sennehed CP, Holmberg S, Axén I, et al. Early workplace dialogue in physiotherapy practice improved work ability at 1-year follow-up-WorkUp, a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Pain. 2018;159(8):1456–1464.

- Hubertsson J, Petersson IF, Arvidsson B, et al. Sickness absence in musculoskeletal disorders – patients' experiences of interactions with the social insurance agency and health care. A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:107.

- Loisel P, Durand MJ, Baril R, et al. Interorganizational collaboration in occupational rehabilitation: perceptions of an interdisciplinary rehabilitation team. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):581–590.

- de Vries HJ, Reneman MF, Groothoff JW, et al. Self-reported work ability and work performance in workers with chronic nonspecific musculoskeletal pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(1):1–10.

- Grant M, Rees S, Underwood M, et al. Obstacles to returning to work with chronic pain: in-depth interviews with people who are off work due to chronic pain and employers. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):486.

- Lindell O, Johansson SE, Strender LE. Predictors of stable return-to-work in non-acute, non-specific spinal pain: low total prior sick-listing, high self prediction and young age. A two-year prospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11(1):53.

- Wåhlin C, Ekberg K, Persson J, et al. Association between clinical and work-related interventions and return-to-work for patients with musculoskeletal or mental disorders. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(4):355–362.

- Cummings EC, van Schalkwyk GI, Grunschel BD, et al. Self-efficacy and paradoxical dependence in chronic back pain: a qualitative analysis. Chronic Illn. 2017;13(4):251–261.

- Kilgour E, Kosny A, McKenzie D, et al. Interactions between injured workers and insurers in workers' compensation systems: a systematic review of qualitative research literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):160–181.

- Esteban E, Coenen M, Ito E, et al. Views and experiences of persons with chronic diseases about strategies that aim to integrate and re-integrate them into work: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5):1022.

- Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, et al. A synthesis of qualitative research exploring the barriers to staying in work with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(6):566–572.

- Sallinen M, Kukkurainen ML, Peltokallio L, et al. Women's narratives on experiences of work ability and functioning in fibromyalgia. Musculoskeletal Care. 2010;8(1):18–26.

- Patel S, Greasley K, Watson PJ. Barriers to rehabilitation and return to work for unemployed chronic pain patients: a qualitative study. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(8):831–840.

- Ahlstrom L, Dellve L, Hagberg M, et al. Women with neck pain on long-term sick leave-approaches used in the return to work process: a qualitative study. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(1):92–105.

- Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(2):228–237.

- Guba YLE. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, London, New Delhi: SAGE Publications; 1985.