Abstract

Purpose

An evidence-based, theory-driven self-management programme “My Life After Stroke” (MLAS) was developed to address the longer-term unmet needs of stroke survivors.

This study’s aim was to test the acceptability and feasibility of MLAS as well as exploring what outcomes measures to include as part of further testing.

Methods

Stroke registers in four GP practices across Leicester and Cambridge were screened, invite letters sent to eligible stroke survivors and written, informed consent gained. Questionnaires including Southampton Stroke Self-Management Questionnaire (SSSMQ) were completed before and after MLAS.

Participants (and carers) attended MLAS (consisting of two individual appointments and four group sessions) over nine weeks, delivered by two trained facilitators. Feedback was gained from participants (after the final group session and final individual appointment) and facilitators.

Results

Seventeen of 36 interested stroke survivors participated alongside seven associated carers. 15/17 completed the programme and attendance ranged from 13–17 per session. A positive change of 3.5 of the SSSMQ was observed. Positive feedback was gained from facilitators and 14/15 participants recommended MLAS (one did not respond).

Conclusions

MLAS was a feasible self-management programme for stroke survivors and warrants further testing as part of the Improving Primary Care After Stroke (IPCAS) cluster randomised controlled trial.

My Life After Stroke is a self-management programme developed for stroke survivors living in the community.

MLAS is feasible and acceptable to stroke survivors.

MLAS could be considered to help address the unmet educational and psychological needs of stroke survivors.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Survival after stroke is increasing [Citation1,Citation2], so a greater number of stroke survivors are living with the long-term impact of their stroke. This has led to an increased focus on long-term care needs for both stroke survivors and their carers. However, survey findings demonstrate that the longer term needs of stroke survivors and their carers are not being adequately addressed, with the majority being dissatisfied with the care they receive after hospital discharge [Citation3,Citation4] and qualitative studies suggesting stroke survivors and caregivers feel abandoned [Citation5].

Among the many unmet needs of stroke survivors and their carers, information needs rank high in survey responses [Citation3], despite provision of information being recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [Citation6]. There is a wealth of printed (and on-line) information but a Cochrane Review concluded that it is still unclear how best to provide this [Citation7]. In other long term conditions, NICE advises self-management programmes be tailored to the needs of the individual, evidenced-based and theory-driven [Citation8]. Community self-management programmes have been found to benefit stroke survivors, however, some previous studies have taken place with small numbers of participants, or in countries other than UK where health systems and culture are different [Citation9] or are delivered on a one-to-one basis [Citation10,Citation11], which can be expensive and may not fully address social support needs. Group-based interventions have shown variable results [Citation12,Citation13]. Therefore the most appropriate content and approach to delivery remains to be determined and further high quality trials to test feasibility, acceptability and efficacy are needed [Citation3,Citation9,Citation14,Citation15].

We have therefore developed an evidence-based, theory-driven self-management programme (My Life After Stroke; MLAS) for stroke survivors (reported elsewhere). As part of our preliminary work, we found that other stroke self-management studies used a variety of different primary outcomes measures. Although outcome measures often revolve around self-efficacy or quality of life [Citation16], a universally agreed outcome measure is yet to be established for these types of interventions.

Therefore we carried out a feasibility study, in order to:

Test the acceptability and feasibility of our self-management programme (MLAS) for stroke survivors, carers and facilitators, prior to investing in a multi-centred randomised controlled trial (RCT), and secondly,

Explore which outcome measures we should include within an RCT.

Methods

The MLAS programme

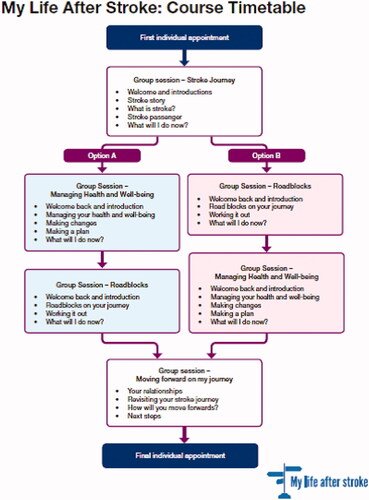

The development of MLAS has been reported elsewhere. In brief, MLAS is underpinned by the narrative therapy approach [Citation17] and consists of one 30–45 min one-to-one individual appointment, 4 weekly group sessions of 2.5 h each and a final 30 min one-to-one individual appointment four weeks after the final group session. shows the structure and content for each session.

Figure 1. Structure and content of the MLAS programme. A flow chart showing the ordering of MLAS sessions. MLAS starts with a first individual appointment, followed by the Stroke Journey group session then will undertake either option A (Managing Health and Wellbeing followed by Roadblocks sessions) or option B (Roadblocks then Managing Health and Wellbeing). Whether option A or B is taken, the final group session is Moving Forward on my Journey followed by the final individual appointment.

Participants receive four handbooks (one for each group session) which adhere to accessible information guidelines [Citation18] and a stroke directory which detail relevant organisations and contacts for the participants’ geographical area. The programme is designed to be delivered to four to eight stroke survivors and carers are also welcome to attend. Two trained facilitators deliver MLAS in an interactive style, supported by a curriculum and resources for each session.

Facilitator training

Facilitators were recruited via advertisements, including those known to be delivering existing self-management programmes in other chronic conditions and then interviewed. Facilitators (who could be lay or health care professionals) were required to have experience of long-term conditions, demonstrate effective communication skills and have a non-judgmental approach. Successful candidates were appointed and attended a 3-day training course in order to deliver the intervention. The training course was developed () based on existing training packages for other self-management programmes [Citation19]. The aims of training were to understand and be able to apply the theories and philosophy underpinning MLAS and become familiar with the MLAS curriculum and associated resources. Stroke-specific training was provided to equip facilitators with skills and knowledge needed to take into account the wide variations of (dis)abilities stroke survivors can exhibit.

Table 1. outline of the 3-day facilitator training course.

Feasibility study

Primary care stroke registers in four GP practices across Leicester (n = 3) and Cambridge (n = 1) were screened for eligible participants. GP practices were recruited by responding to a Research Information Sheet for Practices sent by the Clinical Research Network. Participants were included if they had a confirmed diagnosis of stroke, were aged at least 18 years and able to provide informed consent. Participants were excluded if they had no history of a stroke (i.e., transient ischaemic attack, or “mini stroke” only), lived in residential care, had a terminal illness, were unable to understand English, were currently undergoing intensive rehabilitation (i.e., within 6 weeks of acute stroke) or had dementia, severe ongoing cognitive or mental health problems that would significantly limit their involvement in the programme. Invite letters were sent to eligible participants via the participating GP practices, informing them about the study and providing them with a reply slip and freepost envelope for them to return, indicating if they were interested in the study or not. For those interested, a patient information sheet was then sent and subsequent contact made to screen individuals and book consent appointments where relevant. Reminders were sent out two weeks later to those who had not responded. After one mail out, invite letters were amended to make it clearer that transport could be provided and pre-emptive phone calls were made by GP practice staff to inform eligible patients that they would be receiving the invite letter in the post. For those interested in the study, they were asked if their carer may also be interested in participating and relevant documents were sent out.

Written consent was taken for all participants (stroke survivors and carers) at a consent appointment at a community venue. Baseline data (including completion of questionnaires) was also collected at this appointment by a research nurse. Stroke survivors completed the Stroke Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SSEQ) [Citation20], Stroke-Specific Quality Of Life Scale (SS-QOL) [Citation21], Stroke Impact Scale-Short Form (SIS-SF) [Citation22] and Southampton Stroke Self-Management Questionnaire (SSSMQ) [Citation23] in random orders. Assistance from an independent research nurse was provided if stroke survivors needed help completing the questionnaire (e.g., in terms of overcoming physical impairment). Participants were then allocated to an MLAS programme at a local community venue and dates for all sessions provided upfront.

Following the final group session, all participants were invited to stay for a feedback session lasting up to 60 min. This was facilitated by an independent researcher not involved in the programme delivery, using a topic guide (Supplemental Appendix 1). An observer made notes based on participants’ responses and feedback as not all participants gave consent for these feedback sessions to be audio recorded. Further written feedback was gathered via forms (Supplemental Appendix 2) provided to participants after the final individual appointment to gain satisfaction levels about the MLAS programme and identify areas for improvement as well as completion of the 4 questionnaires again.

Attendance rate and reasons for non-attendance were recorded by facilitators throughout the programme.

A group feedback session was also held with facilitators from both sites at the end of the feasibility study. This explored facilitators’ thoughts about what could be adapted or improved in terms of their training and support as well as the self-management programme itself. This was conducted by an independent researcher not involved with MLAS, with an observer taking notes.

Descriptive statistics were carried out for quantitative data. A content analysis of the qualitative data from the observer notes and participant responses from the written feedback forms were carried out.

Outcome measures

In order to help decide which outcomes measures should be included in future analysis of MLAS, completion rates of the questionnaires, change in scores pre to post-MLAS (including ceiling effects) and participant feedback were discussed within the wider research steering group meetings (including statistician input). These discussions also took into account how each questionnaire had the potential to be sensitive to change based upon how it related to the intervention and what would be achievable to undertake as part of the larger cluster RCT.

Results

Seventeen stroke survivors and 7 associated carers took part in the study. Three programmes were delivered; two in Leicester (n = 11, carers = 5) and one in Cambridge (n = 6, carers =2). Six facilitators were trained (three from Cambridge and three from Leicester) to deliver these MLAS programmes across both locations. Participants remained in their allotted cohort. shows demographic information of participants. All stroke survivors and carers were White British and all carers were spouses of the stroke survivor.

Table 2. Demographics of stroke survivors and carers that attended MLAS.

Recruitment and retention

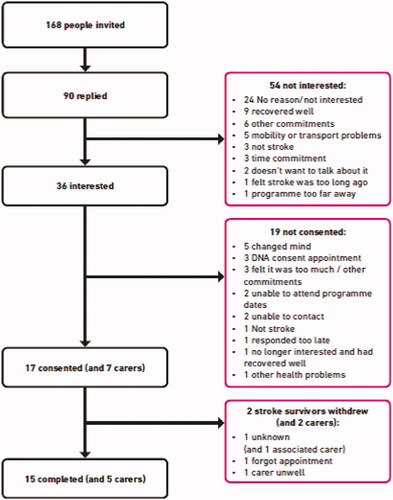

An overview of the number of invitations sent out, responders, those interested and consented and reasons for not participating are demonstrated in . Of those invited, 21.43% were interested in taking part and 47.22% of those consented. 88.24% of those that consented, completed MLAS. Attendance rate for each session of the programme and reasons for non-attendance (where applicable) are shown in .

Figure 2. Recruitment flow chart. A flow chart showing 168 people were invited to take part in the MLAS feasibility study, leading to 90 who replied, 36 of these were interested in the study. 17 consented and 15 completed the study. Reasons for not being interested or consenting or withdrawing are shown and included people having other commitments or being unable to attend session dates, mobility or transport problems to get to appointments, feeling too well or fully recovered from their stroke, their stroke being too long ago and some people did not provide a reason.

Table 3. Attendance rates and reasons for non-attendance for each MLAS session.

Outcome measures

There was a positive change in scores for SSSMQ at the end of MLAS compared to baseline, with other questionnaire results changing marginally. Mean baseline scores and change from baseline for each questionnaire are reported in .

Table 4. Baseline and change in stroke survivor questionnaires scores.

Stroke survivor and carer feedback

Written feedback

Written feedback data was received from 15 participants after the final individual appointment. Participants either strongly agreed or agreed that: they felt listened to ((15/15); the facilitator was interested in them as a whole person (14/15) and; the programme helped them to take control [(11/15) 2 participants did not respond and 2 did not agree nor disagree]. 14/15 participants would recommend MLAS to someone else (1 did not respond).

Feedback sessions

12 stroke survivors and 6 carers (from 3 cohorts) attended the feedback sessions at the end of group session 4. A content analysis was carried out on researchers’ notes from these sessions as well as the qualitative feedback received from written feedback forms (of which, quotes are provided in ). The following headings summarise the main areas that feedback represented.

Table 5. Summary of participant feedback in the feasibility study.

General feedback

In general, the programme was described as helpful, easy to understand, informative and the interactive format was positively spoken of. Participants felt it gave them a feeling that they were not alone. The timings of sessions and the length of each session was acceptable, with one suggestion of spreading the content over a greater number of sessions (for example six shorter sessions rather than the current four), bringing the advantage that if you miss a session, it would be less content missed.

One point for improvement across two of the groups was that at times they felt the content was repetitive, however, others enjoyed the opportunity to recap so this point may depend on individuals’ preferences and stroke recovery.

Venue

It was consistently reported that having the sessions delivered in a community venue rather than a hospital was a strong positive to the programme. Some participants reported that a hospital setting would have been a deterrent to them attending and this is an important consideration when planning where to deliver programmes. Furthermore, practical aspects of no parking fees were also commented upon to avoid worry about charges and running out of time.

Session topics and structure

Overall, feedback regarding content was generally positive and enjoyable. One group commented that they enjoyed a less medical focus with more attention being paid to wider health and diet. The relationships topic was well-received with participants commenting that they were surprised they talked so openly about this. The roadblocks session was less recalled, suggesting that this lacked meaning or relevance to participants, which could relate to the timing of attending MLAS (see below section) or further refinement of the learning aims being needed. Having a one-to-one with a facilitator prior to group sessions was another positive aspect and enabled participants to understand what was involved, start to build rapport with the facilitator and share their personal stroke story. The group sessions gave participants the feeling that they weren’t alone and they found hearing other stroke survivors’ experiences helpful.

It was highlighted that when facilitating a session, it can be important to balance the group discussion with delivery of content; some participants felt that more time to discuss topics would have been beneficial, whereas others felt that at times, content would be rushed to make up for extended discussions that had strayed off the immediate topic.

Journey analogy

There was variation in the feedback received about the journey analogy used across the sessions. For some, this was very relevant to how they felt about their stroke experience and easy to understand. However, there were comments across two of the groups that found this basic, or that whilst the analogy itself was acceptable, they found the physical resources (including a car, road and other related images) that were used within the group sessions to support this analogy, gimmicky. Instead they would have preferred more of a diagram, rather than physical accessories.

Timing of MLAS

There were conflicting opinions about when (in relation to time since stroke) that MLAS should be best delivered. Some reported that they would have liked to receive this sooner (as they felt that previous information they had received was not sufficient), whereas others felt a delay was good so that they had had space to process and understand their stroke and it’s recovery. It can be difficult to conclude from this small sample, about the optimal time of delivery for MLAS (or similar programmes) and a greater understanding of this is needed in stroke care. There was also a suggestion that it may have been useful for stroke survivors who attended MLAS to be of more mixed ability/disability, as participants felt most of those who attended where not that limited by their stroke. Considering the variable opinions in our small sample, it is possible that factors such as satisfaction with post-stroke information, time since post stroke and how abled or adapted to life after stroke participants felt (in this sample) influenced feedback about this.

Carer role

Many felt positive about the inclusion of carers in the MLAS programme. The presence of carers was described as helping to reinforce the programme at home and aiding understanding and learning. Some reported that it helped encourage the stroke survivor to attend, and that having separate points where stroke survivors and carers carried out activities independently was beneficial. However, one group did acknowledge that the presence of carers could also be a barrier within the programme, for instance, if a participant wanted to discuss things that they didn’t want their spouse/carer to hear. This suggests that whilst there is a benefit to both carers and stroke survivors to have a programme that includes carers, that this should be optional in consideration of individual circumstances.

Facilitators

Stroke survivors commented how understanding and approachable the facilitators were. They felt the facilitators worked well together, which was viewed as important. Participants thought the facilitators made them feel comfortable and treated them as a person rather than talking down to them. Participants preferred to have the same facilitators throughout the programme, although logistically this was not always possible to achieve.

Outcome measures

Some participants fed back that the questionnaires could be confusing, repetitive and too long and this is an important consideration for outcomes when evaluating such programmes. In this instance, we acknowledge that there was a greater number of questionnaires measuring similar outcomes as one aim of this feasibility study was to establish the most appropriate measures for a larger study. Upon review of the completed questionnaires, 14/15 participants achieved the maximum score in at least 1 domain of the SIS and 12/15 participants scored the maximum in at least 1 domain of the SSQOL at baseline. Two participants ran out of time to complete the SIS and SSSMQ during their appointments.

Facilitator feedback

Feedback received from facilitators via the feedback sessions are captured under the following headings and provide insight into skills and training needs and adaptations that could be made to MLAS to aid delivery.

Learning & training needs

Facilitators stated that more time in training, and afterwards, to practice facilitator skills and behaviours would be beneficial and help with confidence. Some facilitators only delivered one programme, whereas those who delivered more, felt they improved during subsequent programmes. For example, facilitators wanted to feel more skilled and confident with the CBT based session (within Roadblocks), as well as the broader behaviours such as posing reflective questions to the group whilst also being mindful of keeping a session on track and running to time. While some facilitators found completing some of the flip charts and the start of sessions repetitive, those who delivered more sessions, realised the curriculum is a guide to delivery, which can be tailored to some extent to the group, using their facilitation skills. More time to practice using the handbook and how to integrate it into sessions was also described.

It was suggested within training, that observing how another facilitator introduces the journey analogy would be useful, as well as having more emphasis of the rationale behind this analogy and how to support a group if they struggle to engage with the roadmap analogy and resources. Having a video of facilitators delivering certain sessions may also be useful to reinforce training received. Facilitators also felt that their curriculum could include “tips” about delivery, such as strategies to keep to time and managing extended discussion between participants.

Suggested adaptations to the programme

Facilitators felt that many flipcharts throughout some sessions could lead to some repetition and that reducing some of these could be helpful. As previously mentioned by participants, facilitators also commented that at times they found it difficult to engage them with the journey analogy. As well as increasing the emphasis on this within training, it was also suggested to include more explanation regarding the background and rationale of this analogy within the curriculum and more explicitly detail how the facilitators can set the scene for participants using this analogy at the beginning of sessions.

Interestingly, it was also suggested that more time should be allocated to the relationships section, which was also given positive feedback in the participant accounts. Facilitators also made practical suggestions such as having separate rooms for carers and stroke survivors when they complete activities apart, ensuring facilitators remain the same throughout the duration of the programme where possible and more time to spend reviewing handbooks with participants individually.

In keeping with participant feedback, facilitators also reflected that engagement could depend on how long ago a participant had had their stroke. For those whose stroke was a long time ago, engagement with some sections, such as Moving Forward, were difficult as they felt that participants had already largely adapted to life after stroke and so would have benefitted from this material earlier on. Again, this raises the problem of the optimal timing of such programmes in stroke care and may be worthy of further exploration on the factors that influence when is the “right” time for stroke survivors to receive such interventions.

Discussion

We have shown that My Life After Stroke is an acceptable and feasible self-management programme to deliver to stroke survivors in the community. Feedback from MLAS was positive, although completion of all the questionnaires was difficult for some.

Attendance rates and retention to MLAS itself was high, suggesting it is a feasible programme. Fewer people attended group session 4 in the Cambridge cohort, mainly because the timing coincided with holidays over the summer period. This is a useful point to consider when scheduling programmes. The two stroke survivor withdrawals were also in this Cambridge cohort which could indicate a difference in sites or could also potentially be due to this cohort overlapping the peak summer holiday period more than the Leicester cohorts, but as these withdrawals did not give a reason, we are not able to draw conclusions. It may be beneficial for stroke survivors to be able to attend a catch-up session in a different cohort if they miss a session; however this may not be acceptable as all stroke survivors in our study remained in the same cohort with some feedback that participants would prefer to stay in the same cohort. Participants were informed of session dates in advance of being consented, which may also have contributed to the high attendance rates.

We appreciate asking stroke survivors to complete four fairly lengthy questionnaires as part of this study was time consuming and difficult and potentially a reason why some data was missing. However, our rationale for including all of these was to investigate which outcome measure(s) should be included in the forthcoming RCT. There was a wide variation seen for baseline and change in scores for each questionnaire, likely due to the small number of participants in this feasibility study and the large variation in time since having had their stroke. Statistical significance was not calculated due to this being a feasibility study and therefore not powered for this purpose. The SIS was included because the primary outcome measure for the main RCT was likely to be this. The SSQoL had items relating to psychosocial adjustment which MLAS corresponds with, however, it also has many items relating to physical function, as does the Stroke Self-efficacy Questionnaire, which do not necessarily fit with the content and theoretical basis of MLAS and maybe explains the lack of change seen in this feasibility study. Ceiling effects were observed in at least 1 domain of the SIS and SSQOL at baseline. Many of the statements of the SSSMQ match with the aims of MLAS and is maybe why this measure demonstrated positive change within this study. While, a minimal clinically important difference has not been determined for the SSSMQ, it appears this measure was sensitive to change and should therefore be included in the RCT.

There was a wide variation amongst participants in time since people had had their stroke and attending the programme, with some people commenting that they wanted it later or sooner. Delivering self-management programmes too soon may be inappropriate as they may not have capacity to set goals but leaving it for a long period of time could mean stroke survivors are not accessing the right intervention at the right time for them. Therefore it appears individual preference should determine if and when stroke survivors attend MLAS (which is discussed during the initial individual appointment), rather than implementing specific inclusion/exclusion criteria and maybe should be considered when reviewing their needs annually [Citation5]. Furthermore, having a group of mixed (dis)abilities and length of time since stroke, may help some stroke survivors in terms of realising where they are on their own journey and recovery potential.

It could be argued that there was low uptake to this self-management programme, given that only 21% of people were interested and 10% were consented onto this study. However there were many reasons for people not being willing or able to take up this study, which wasn’t necessarily due to the intervention itself. Interested reply rates and recruitment rates increased after the first mail-out, once invite letters were amended and GP practice staff contacted stroke survivors to pre-empt receipt of the invite letter. Recruiting to research studies can be difficult, but in this population where stroke survivors may be limited by physical, visual and/or cognitive impairments, the effort involved in getting to the venue, understanding written information and filling out forms, may be an additional barrier to recruitment. Some of these barriers may have been overcome by emphasising the availability of transport at first contact and the pre-emptive phone calls which helped to engage participants and highlight the study to potential participants from a known, trusted member of their GP practice with whom they already had some relationship with (rather than an unknown researcher) and so indicates useful recruitment strategies for the RCT and future implementation. All participants were White British which suggests additional recruitment strategies and cultural adaptation of MLAS is needed for stroke survivors of other ethnicities. This was beyond the scope and resources available for this feasibility study but we would envisage culturally adapting MLAS where appropriate before real-world implementation [Citation24]. Recruitment rates have been found to vary widely and Caucasians be over-represented in other chronic disease self-management programme research [Citation25]. Furthermore, interventions such as MLAS are not necessarily suitable, or appropriate for all, especially in this population where effects following stroke can vary from being very disabled to recovering well due to medical advances; therefore MLAS should be seen as another treatment option in the stroke pathway. Retention and feedback from those who attended MLAS was very positive, suggesting that those who did attend, found it beneficial. Feedback from stroke survivors and facilitators were also quite similar, suggesting the points they raised were valid. However, those who didn’t stay for the feedback sessions may have had different opinions. We tried to gain as many perspectives as possible through also providing the opportunity to feedback via written forms however we anonymised feedback session responses and written feedback forms so do not know who did or did not give their opinion.

Limitations to this study included all participants being White British, therefore results may not be generalisable to other ethnicities. While we tried to find out reasons for any withdrawals to help assess feasibility and acceptability of MLAS, we were unable to ascertain one participant’s reason. Enough facilitators were recruited and trained to deliver MLAS, however they only delivered one or two programmes each; therefore they may not yet have had the opportunity or experience to fully develop their skills. This will be taken into account during the cluster RCT by refining facilitator training, providing mentorship and assessing intervention fidelity. By further training, repeated delivery and familiarisation of MLAS and its components, this may help to address some of the stroke survivors’ and facilitators’ recommendations of having more time to discuss certain aspects, using the handbooks and adequately explaining the stroke journey analogy. During the development of MLAS, stroke survivor volunteers embraced the journey analogy but this was delivered by researchers involved in its development and therefore fully understood its purpose. This suggests it’s not necessarily the concept itself that need revising but further support and training for facilitators. Therefore, facilitator training for the RCT has been refined based on this feedback and mentorship will also be provided to further help and support facilitators.

In conclusion, MLAS was a feasible self-management programme for stroke survivors. Therefore, this intervention is sufficiently robust to form part of an RCT. MLAS will now be offered as part the Improving Primary Care After Stroke (IPCAS) service development randomised controlled trial [Citation26] which will include a longer-term follow-up, cost-effectiveness [Citation9] and interventional fidelity assessment [Citation27].

Appendix_2_Feedback_form_v.1.0_04-01-2017.pdf

Download PDF (224.5 KB)Appendix_1_Feedback_groups_topic_guide.pdf

Download PDF (332.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The MLAS development group involved a number of team members including Rosie Horne, Clare Makepeace, Lorraine Martin Stacey, Yvonne Doherty, Marian Carey, Jayna Mistry as well as facilitators and PPI members who contributed to various aspects of study set up, trial management, intervention development, refinement and delivery for who we are thankful to.

Disclosure statement

VJ, LA, EK, RM, JM, MJD are, or were, employed through their respective organisations during this work. Intellectual property rights are held through the University of Leicester on behalf of the DESMOND collaborative at Leicester Diabetes Centre.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gulliford MC, Charlton J, Rudd A, et al. Declining 1-year case-fatality of stroke and increasing coverage of vascular risk management: population-based cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(4):416–422.

- Lee S, Shafe AC, Cowie MR. UK stroke incidence, mortality and cardiovascular risk management 1999-2008: time-trend analysis from the general practice research database. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000269.

- McKevitt C, Fudge N, Redfern J, et al. Self-reported long-term needs after stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1398–1403.

- National Audit Office. Progress in improving stroke care. 2010. Available from: https://www.nao.org.uk/report/department-of-health-progress-in-improving-stroke-care/

- Pindus DM, Mullis R, Lim L, et al. Stroke survivors’ and informal caregivers’ experiences of primary care and community healthcare services - a systematic review and Meta-ethnography. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192533.

- NICE. Stroke rehabilitation in adults. 2013. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg162

- Forster A, Brown L, Smith J, et al. Information provision for stroke patients and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(11):CD001919.

- NICE. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28

- Lennon S, McKenna S, Jones F. Self-management programmes for people post stroke: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(10):867–878.

- Jones F, Gage H, Drummond A, et al. Feasibility study of an integrated stroke self-management programme: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e008900.

- McKenna S, Jones F, Glenfield P, et al. Bridges self-management program for people with stroke in the community: a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(5):697–704.

- Cadilhac DA, Hoffmann S, Kilkenny M, et al. A phase II multicentered, single-blind, randomized, controlled trial of the stroke self-management program. Stroke. 2011;42(6):1673–1679.

- Lund A, Michelet M, Sandvik L, et al. A lifestyle intervention as supplement to a physical activity programme in rehabilitation after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(6):502–512.

- Fryer CE, Luker JA, McDonnell MN, et al. Self management programmes for quality of life in people with stroke. Cochrane Stroke Group; 2016. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD010442.pub2/full

- Jones F, Riazi A. Self-efficacy and self-management after stroke: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(10):797–810.

- Cheng HY, Chair SY, Chau JP. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for stroke family caregivers and stroke survivors: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(1):30–44.

- Chow EO. Narrative therapy an evaluated intervention to improve stroke survivors’ social and emotional adaptation. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29(4):315–326.

- Stroke Association. Accessible Information Guidelines. 2012. Available from: https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/accessible_information_guidelines.pdf1_.pdf

- Davies MJ, Heller S, Skinner T, et al. Effectiveness of the diabetes education and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):491–495.

- Jones F, Partridge C, Reid F. The stroke self-efficacy questionnaire: measuring individual confidence in functional performance after stroke. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(7b):244–252.

- Williams LS, Weinberger M, Harris LE, et al. Development of a Stroke-Specific quality of life scale. Stroke. 1999;30(7):1362–1369.

- Duncan PW, Bode RK, Min Lai S, et al. Rasch analysis of a new stroke-specific outcome scale: the stroke impact scale11No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the author(s) or upon any organization with which the author(s) is/are associated. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(7):950–963.

- Boger EJ, Hankins M, Demain SH, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of a new patient -reported outcome measure for stroke self -management: the Southampton stroke Self - Management questionnaire (SSSMQ). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:165.

- Chatterjee S, Davies MJ, Stribling B, et al. Real-world evaluation of the DESMOND type 2 diabetes education and self-management programme. Pract Diab. 2018;35(1):19–22a.

- Horrell LN, Kneipp SM. Strategies for recruiting populations to participate in the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP): a systematic review. Health Mark Q. 2017;34(4):268–283.

- Mullis R, Aquino M, Dawson SN, et al. Improving primary care after stroke (IPCAS) trial: protocol of a randomised controlled trial to evaluate a novel model of care for stroke survivors living in the community. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e030285.

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health psychology: official journal of the division of health psychology. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):443–451.