Abstract

Purpose

This meta-synthesis aimed to synthesise qualitative evidence on experiences of people with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) in receiving a diagnosis, to derive a conceptual understanding of adjustment to MS diagnosis.

Methods

Five electronic databases were systematically searched to identify qualitative studies that explored views and experiences around MS diagnosis. Papers were quality-appraised using a standardised checklist. Data synthesis was guided by principles of meta-ethnography, a well-established interpretive method for synthesising qualitative evidence.

Results

Thirty-seven papers were selected (with 874 people with MS). Synthesis demonstrated that around the point of MS diagnosis people experienced considerable emotional upheaval (e.g., shock, denial, anger, fear) and difficulties (e.g., lengthy diagnosis process) that limited their ability to make sense of their diagnosis, leading to adjustment difficulties. However, support resources (e.g., support from clinicians) and adaptive coping strategies (e.g., acceptance) facilitated the adjustment process. Additionally, several unmet emotional and informational support needs (e.g., need for personalised information and tailored emotional support) were identified that, if addressed, could improve adjustment to diagnosis.

Conclusions

Our synthesis highlights the need for providing person-centred support and advice at the time of diagnosis and presents a conceptual map of adjustment for designing interventions to improve adjustment following MS diagnosis.

The period surrounding Multiple Sclerosis diagnosis can be stressful and psychologically demanding.

Challenges and disruptions at diagnosis can threaten sense of self, resulting in negative emotions.

Adaptive coping skills and support resources could contribute to better adjustment following diagnosis.

Support interventions should be tailored to the needs of newly diagnosed people.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is one of the most common diseases of the central nervous system among young adults, affecting around 2.8 million people worldwide [Citation1]. The diagnostic process can be arduous and complicated due to the variable nature of MS and the lack of a single diagnostic test to confirm it. The lack of a precise and specific MS biomarker also makes the process of reaching a definitive diagnosis challenging [Citation2,Citation3]. There are also a number of conditions that can result in multifocal involvement of the brain and spinal cord, mimicking MS [Citation4] and causing difficulties in confirming the diagnosis. The 2017 McDonald criteria for MS diagnosis combines clinical, imaging and laboratory evidence to make a reliable diagnosis of MS [Citation5]. However, the McDonald criteria are often misunderstood and misapplied [Citation6], resulting in a lengthy and complex diagnosis process. Consequently, the period surrounding diagnosis in MS can be psychologically demanding, causing distress, confusion and frustration to people with MS and their families [Citation7–10]. The experience of being diagnosed with MS and the way in which this diagnostic phase is managed may influence the individual’s future perceptions about MS, and the nature and quality of their relationships with healthcare professionals [Citation8,Citation11]. Therefore, support around this challenging and confusing period is important.

Current evidence suggests that the support and information provided at the time of diagnosis is poor, and there is a need to design effective interventions, or improve available services, specifically targeting newly diagnosed individuals [Citation12–16]. It is well-established that interventions should be based on sound theoretical frameworks, providing researchers and clinicians with an evidence-based approach that helps identify potential mechanisms of action and the most important factors that can be targeted [Citation17–19]. However, the current literature lacks a comprehensive multi-dimensional theoretical framework, which limits our ability to fully understand the needs and experiences of people with MS around the point of diagnosis. This makes it difficult to design and deliver services for these individuals. The lack of theoretical framework also limits our ability to consider the relevance and importance of other MS adjustment literature for translatable knowledge.

There are models of adjustment studied specifically to understand the adjustment to living with MS in general [Citation20–22]. These models are largely guided by Lazarus and Folkman’s [Citation23] Transactional Model of Stress and Coping. This model describes stress as the result of a transaction between the person and the environment, which is mediated by a person’s cognitive appraisal of the stressor (primary appraisal) and an evaluation of the available social and coping resources (secondary appraisal) [Citation23]. According to this model, adjustment to a chronic illness can be influenced by an individual’s appraisal of this stressful life event, the coping resources and strategies they use for managing this situation, and their appraisal of the efficacy of the strategies used. However, this model has been criticised for underestimating the complexity of relationships between stressors, coping and appraisals [Citation24,Citation25], and for not accounting for other external and contextual factors [Citation26]. When applied to illness adjustment, the model emphasises the importance of reappraising the illness as non-threatening [Citation27]. However, due to the unpredictable and progressive nature of MS, reappraisal of the condition as ‘non-threatening’ may be difficult to accomplish for a person living with MS [Citation16]. A recent meta-review [Citation16] identified other models for understanding adjustment to MS, such as the working model of adjustment to MS [Citation28], model of emotional adjustment and hope [Citation29], model of the psychological impact of the unpredictability of multiple sclerosis [Citation30]. Although these models were postulated to be important in understanding adjustment to MS in general, their utility in explaining adjustment to the process of being diagnosed to MS is unclear, as none of them specifically targeted the challenges faced at the time of the diagnosis [Citation16]. Therefore, more in-depth and person-centred qualitative research is needed to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework that focuses specifically on the period around MS diagnosis. This would guide the development and provision of services for people with MS at the point of diagnosis in a more accurately targeted way.

Our initial scoping exercise of the literature revealed that there were several qualitative studies that investigated the views of newly diagnosed people with MS, or people being diagnosed, and their experiences. To enhance our understanding of the existing qualitative evidence and increase the trustworthiness (i.e., credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability) and authenticity of qualitative findings [Citation31], we conducted a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on experiences of people with MS receiving a diagnosis. The aim of our meta-synthesis was, therefore, to explore the views and experiences of individuals around the point of MS diagnosis to derive a conceptual understanding of how people adjust to the diagnosis of MS.

Methods

The systematic review protocol was prospectively registered on Prospero (Registration ID: CRD42017067703, 10/07/2017).

Search strategy

The CHIP (Context, How, Issues, Population) tool [Citation32] was used to formulate the terms for the search strategy. A health sciences librarian with expertise in systematic review searching and our Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) co-author were consulted during the development of the final search strategy for the meta-synthesis. We followed Shaw's [Citation33] recommendations for identifying qualitative research articles within electronic databases. A systematic search of five electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Web of Science) was conducted in July 2017 and updated in August 2021. No start date was set for the search, therefore the search identified the digitally published studies from the inception of the databases, including any back publications incorporated into the online databases after inception. The final search strategy was adapted to the syntax and subject headings of each database, and, where possible, the MeSH explode function was used. Boolean operators (i.e., ‘AND’ and ‘OR’) were used to combine the final search terms. We kept our search criteria broad to be inclusive and to not overlook any important papers on MS diagnosis (See Supplementary Appendix A for the final search strategy for MEDLINE). To maximise the identification of relevant studies, the reference lists of all potentially relevant articles that met the inclusion criteria were examined.

Selection criteria

Papers were included if they: (1) were published qualitative studies (i.e., studies that used qualitative methods for data collection and analysis) – Mixed methods studies were included in the meta-synthesis, as long as their qualitative components met the inclusion criteria and formed a substantial part of the study, (2) explored the views and experiences of people around the point of MS diagnosis (studies including people who had been diagnosed years before entering the studies were also considered eligible, but only if the studies focused on retrospective diagnosis experiences), and (3) were published in English. Papers were excluded if they: (1) focused on people with conditions other than MS, (2) focused on people under the age of 18, or (3) were qualitative studies on the transition and adjustment to secondary progressive MS, or the adjustment to the disabling symptoms long after diagnosis.

Screening and data extraction

The selection process involved the screening of titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria by at least two reviewers. Any uncertainties regarding the eligibility of any particular paper for inclusion were addressed through full-text screening, and irrelevant papers were discarded. The full-texts of all remaining potentially relevant papers, including those over which there was doubt, were then screened for eligibility by at least two reviewers independently. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, or arbitrated if necessary, by the wider review team. Similarly, if eligibility was unclear, this was discussed across the wider team. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [Citation34] flowchart was used to record the review process step-by-step (See ). The findings of the papers selected for inclusion in the review, including the raw data (i.e., first-order constructs), and the themes and authors' interpretations (i.e., second-order constructs) were then recorded onto structured data extraction forms by at least two independent reviewers.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram describing the literature search and screening process (Adapted from Moher et al. [Citation34]).

![Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram describing the literature search and screening process (Adapted from Moher et al. [Citation34]).](/cms/asset/eee187da-23c1-4fe6-9152-db4b6ffb6c85/idre_a_2046187_f0001_c.jpg)

Critical appraisal

The quality of the included studies was assessed independently by at least two researchers using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [Citation35] tool for qualitative research. In addition, the Traffic Light System [Citation36] was used to grade each article as green (key paper and satisfactory paper), yellow (unsure), and red (fatally flawed and irrelevant paper). The review team met to agree on the quality of the studies, and any disagreements between them were arbitrated. The aim was to assess the contributions of each paper to the synthesis and to highlight their potential limitations, rather than to exclude papers [Citation37–39]. Therefore, no papers were excluded on the basis of their critical appraisal rating.

Synthesis

Data synthesis was conducted in accordance with the principles of meta-ethnography outlined by Noblit and Hare [Citation40] and Malpass et al. [Citation37], following an inductive approach. Meta-ethnography is an inductive, interpretive approach to synthesising qualitative evidence [Citation37,Citation40–42]. It has emerged as a leading method for synthesising qualitative evidence in healthcare research [Citation43], and its utility with regard to developing a theoretical understanding of the current evidence base has been established [Citation33,Citation37,Citation42,Citation43]. Meta-ethnography was initially developed for combining data from ethnographies (i.e., qualitative research method that provides an account of a particular group or phenomenon, through descriptive interpretation of behaviours, situations and practices), but later adapted to synthesise findings from a wider range of qualitative approaches [Citation44]. We chose meta-ethnography as the synthesis approach due to its interpretative nature and capacity to formulate new conceptual understandings of a phenomenon [Citation44].

The meta-ethnographic process involved interpretative activity (reciprocal synthesis) in which we compared and contrasted themes across articles to develop our third-order themes (i.e., higher-order constructs; synthesists’ interpretations of first- [participant quotations] and second-order constructs [interpretations of authors] expressed as themes and key concepts). A line of argument through the identified third-order themes was created to explore what the set of individual studies say as a whole. The synthesis phase was led by the first author with independent input from the other researchers in the team (including our PPI co-author). In addition, to ensure trustworthiness (i.e., credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability) of findings, the preliminary results were discussed at a PPI meeting with 10 people with MS, 3 carers, 9 clinicians, and 9 charity volunteers (who were also patients or carers themselves) to agree on the final themes and conceptual organisation.

Results

We identified 37 papers that met the inclusion criteria and had a focus on diagnosis experiences of people with MS (recent or retrospective). Some papers drew on the same data (i.e., [Citation45] & [Citation46] and [Citation47] & [Citation48]). Fifteen of the studies were conducted in the UK [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11,Citation14,Citation49–59], four studies in Canada [Citation60–63], three studies in Italy [Citation10,Citation64,Citation65] and Iran [Citation45,Citation46,Citation66], two studies in USA [Citation67,Citation68], The Netherlands [Citation47,Citation48], Germany [Citation69,Citation70] and Malaysia [Citation71,Citation72], and one study in Australia [Citation73], New Zealand [Citation74], Sweden [Citation75] and Norway [Citation76]. The total number of participants across all studies was 874 people with MS (∼517 women; gender was not reported in five studies [Citation56,Citation63,Citation69,Citation72,Citation76]), 38 family members/carers and 19 healthcare professionals. The age range of participants across the studies was 18–82 years. The disease duration ranged from 0 (i.e., time of diagnosis) to 47 years. See Supplementary Appendix B for the full list of included papers and Supplementary Appendix C for study characteristics.

Overall, the quality of the papers was satisfactory (See Supplementary Appendix D). Only one paper [Citation50] was rated as ‘unsure’ because of a lack of a clear description of its research design and qualitative data analysis procedures.

The reciprocal synthesis resulted in two overarching third-order themes: (1) Receiving the MS diagnosis, and (2) Support and informational needs around diagnosis. presents a summary of the derived third-order themes and sub-themes, and the respective articles that contributed to the development of each theme. Supplementary Appendix E illustrates participants’ quotations that are representative of the third-order themes.

Table 1. Themes and sub-themes derived from the studies reviewed.

Receiving the MS diagnosis

This overarching third-order theme encompassed the emotional reactions and difficulties experienced around the point of diagnosis, and how people appraised and responded to the diagnosis.

Emotional reactions

There were consistent findings among the papers regarding the emotional reactions experienced at different time points (i.e., pre-diagnosis, at the time of the diagnosis and post-diagnosis). The most common emotional reactions, identified by 29 papers, were fear, anxiety and worry during both the pre-diagnosis and post-diagnosis period [Citation7,Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation14,Citation45–47,Citation49–52,Citation54–56,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation65–72,Citation74,Citation75]. Before the diagnosis, people reported feeling worried and scared that they might have a brain tumour or other life-threatening disease [Citation14,Citation45,Citation51,Citation61,Citation62,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75]. The strangeness of undergoing multiple medical tests [Citation55,Citation62,Citation69,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75] and the uncertainties during the pre-diagnosis process [Citation11,Citation54,Citation61,Citation62,Citation66,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75] also evoked fear and anxiety in some people. Lack of knowledge about MS at the time of diagnosis [Citation45,Citation55,Citation56,Citation62,Citation66,Citation74], uncertainty about the future (including the future progression of MS) [Citation7,Citation8,Citation14,Citation45,Citation49,Citation51,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation65–68,Citation72,Citation74,Citation75] and threatened roles, goals and relationships also led to feelings of fear and anxiety [Citation7,Citation14,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation51,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation65,Citation66,Citation71,Citation72,Citation75].

Denial at the time of diagnosis was another frequently reported emotional reaction, reported in 14 papers, which led people to blank out information and decline the support offered. Many people with MS reported that they repressed the diagnosis news at first by denying that the diagnosis happened or ignoring it [Citation7,Citation11,Citation45,Citation51,Citation56–59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation68,Citation74,Citation75]. Others refused to accept the diagnosis as they did not believe the accuracy of the test findings [Citation55,Citation59,Citation75].

Feelings of sadness and depression were also commonly reported (21 papers in total) [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11,Citation45–47,Citation49,Citation51,Citation55,Citation58–62,Citation64–66,Citation68,Citation72,Citation74,Citation75]. Some people described receiving the diagnosis as a traumatic experience that had emotionally wounded them [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11,Citation45,Citation46,Citation49,Citation55,Citation58,Citation60–62,Citation64,Citation74,Citation75]. They were saddened by the threat to life roles and self-identity, lost dreams and the possible changes to their future plans [Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation62,Citation68,Citation75]. Some people reported feeling depressed and having suicidal thoughts immediately after receiving the diagnosis [Citation45,Citation51,Citation59,Citation65,Citation68,Citation72,Citation74,Citation75]. Others reported feelings of sadness about the symptoms pre-diagnosis for which there were difficulties in attributing a cause to and about not being believed by other people (including the clinicians) [Citation75]. People also consistently reported feeling helpless and out of control during pre- and post-diagnosis periods, particularly while undergoing several different medical tests and waiting for the results [Citation10,Citation14,Citation45,Citation48,Citation51,Citation53–55,Citation59,Citation61,Citation65,Citation74,Citation75].

Another common emotional reaction around the point of diagnosis was anger, reported in 17 papers [Citation7,Citation45–47,Citation49–51,Citation54,Citation55,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation66,Citation68,Citation74,Citation75]. People reported feeling angry and frustrated by the lack of understanding and support from their friends and families [Citation45,Citation46,Citation50,Citation55,Citation66,Citation75], and by health professionals for not believing them previously or holding back information [Citation51,Citation54,Citation55,Citation75]. The prolonged diagnostic process and the way individuals had received their diagnosis also evoked feelings of anger towards clinicians and the healthcare system [Citation51,Citation54,Citation59,Citation61,Citation75].

Although reported emotional reactions towards the diagnosis were mostly negative, people with MS also frequently expressed a sense of relief upon receiving a diagnosis [Citation8,Citation11,Citation14,Citation51,Citation55,Citation58,Citation61,Citation62,Citation67,Citation68,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75]. For some, it was a relief to finally have a name for their symptoms and know that their condition was not terminal.

External challenges, disruptions and barriers at diagnosis

Another theme evident from the synthesis, reported in 32 papers, was external challenges, disruptions and barriers that encompassed the difficulties faced by people with MS around the diagnosis. For instance, difficulty in communication with health professionals often led to feelings of distress, and there was generally a sense of dissatisfaction with the support and information provided by health professionals [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation46,Citation50,Citation53–56,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation64,Citation68–70,Citation74,Citation75]. Other common reasons for this dissatisfaction were: professionals not believing patients’ symptoms [Citation8,Citation11,Citation50,Citation51,Citation55,Citation59,Citation61,Citation67,Citation68,Citation75], not answering questions during the diagnostic process or afterwards [Citation10,Citation55,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61,Citation74,Citation75], not spending additional time with patients to provide more information [Citation8,Citation10,Citation58,Citation59,Citation62,Citation74,Citation75], and not providing ongoing care and timely follow-up support [Citation11,Citation58,Citation59,Citation74,Citation75]. Professionals’ perceived lack of knowledge about MS [Citation8,Citation11,Citation53,Citation56,Citation59,Citation75], lack of understanding, caring and empathy [Citation10,Citation46,Citation50,Citation51,Citation56,Citation59,Citation61,Citation64,Citation69,Citation74,Citation75], and only focusing on “solving the puzzle” [Citation11,p.83] led to further feelings of anger, distress and anxiety. However, although people reported mostly negative encounters with health professionals around the point of diagnosis, some patients also stated receiving adequate emotional support and information from health professionals [Citation11,Citation50,Citation56,Citation70,Citation75], particularly from nurses [Citation11,Citation46,Citation62].

Most people also reported a sense of dissatisfaction, disappointment and anger in the way they had received the diagnosis from health professionals and the health professionals’ handling of the situation; this in turn influenced their acceptance and adjustment to MS [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation55,Citation56,Citation58,Citation59,Citation61,Citation68,Citation74]. Some felt that the disclosure was very impersonal with no consideration of their feelings [Citation8,Citation10,Citation59,Citation68,Citation74], and being “very professional” [Citation74,p.437] with no adequate explanation of MS [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation55,Citation56,Citation58,Citation59,Citation68,Citation74]. Some patients described how they felt helpless and vulnerable when they received the diagnosis in an inadequate setting (e.g., over the phone, in a letter to pass on to their neurologist) [Citation8,Citation10,Citation55,Citation58,Citation59,Citation75] or when they received the diagnosis with a degree of uncertainty [Citation55,Citation74] (e.g., “might be MS but it might not be” [Citation74,p.437]). The lengthy diagnostic process, long waiting periods, the amount and foreignness of medical tests, inefficient healthcare system and staff, and having multiple contacts with various different health professionals were also commonly described as a source of distress during the diagnostic process in 16 papers [Citation8,Citation14,Citation50,Citation51,Citation54–57,Citation59,Citation61,Citation66,Citation68–70,Citation74,Citation75].

There were conflicting findings regarding the support received from friends and family around the diagnosis period. While some patients were satisfied with the support received from loved ones [Citation7,Citation11,Citation46,Citation51,Citation57,Citation59–62,Citation65,Citation67,Citation74,Citation75], others felt they were being treated differently, pitied, ignored or rejected, which led to feelings of disappointment, anger and loneliness [Citation8,Citation14,Citation45,Citation47,Citation50,Citation51,Citation56,Citation57,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation65,Citation75].

Invisible symptoms (e.g., fatigue) were expressed by patients in 12 papers as another source of stress they had to deal with during both the pre-diagnosis and post-diagnosis periods. Many patients reported that health professionals did not believe their complaints about fatigue or other invisible symptoms at first [Citation8,Citation11,Citation50,Citation55,Citation59], and that they were labelled as being ‘hypochondriac’ [Citation11,Citation67], ‘daft’ [Citation50], ‘neurotic’ [Citation8], ‘depressed’ [Citation68] or just ‘lonely’ [Citation67]. Clinicians often attributed the invisible symptoms to psychosomatic, psychiatric or emotional problems [Citation54,Citation55,Citation68,Citation75], particularly if the patient was a woman [Citation68]. Consequently, patients often doubted their own symptoms during the pre-diagnosis period [Citation14,Citation59] and felt like they were ‘going crazy’ [Citation67,Citation68]. Such feelings were boosted by the lengthy diagnostic process and the professionals’ negative attitudes.

Coping

A wide range of coping strategies in managing the diagnosis period were identified. These were: (1) Using re-appraisal to find new meanings to life and refocus the life, and re-evaluating the priorities and goals [Citation7,Citation14,Citation47,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52,Citation57,Citation59,Citation61–63,Citation65,Citation71,Citation72,Citation74–76]; (2) Adopting a fighting spirit to maintain a sense of normality and continuity [Citation7,Citation49,Citation65,Citation75]; (3) Focusing on the present and not dwelling on the uncertain/unpredictable future [Citation7,Citation14,Citation49,Citation51,Citation54,Citation59–61,Citation65,Citation67]; (4) Being positive and having a positive mental attitude [Citation7,Citation46,Citation49,Citation51,Citation52,Citation55,Citation57,Citation59–61,Citation67,Citation75,Citation76]; (5) Using religious faith to cope with diagnosis and to attain mental peace [Citation45,Citation46,Citation53,Citation61,Citation67]; (6) Use of self-help management strategies to cope with the diagnosis and manage symptoms during pre-diagnosis or post-diagnosis periods [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11,Citation48–51,Citation58,Citation61,Citation62,Citation67,Citation73,Citation76]; (7) Seeking information from various resources (e.g., the Internet, MS organisations, health professionals, books, pharmaceutical companies, etc.) to increase knowledge about MS and its management [Citation7,Citation8,Citation10,Citation45,Citation46,Citation49–51,Citation55,Citation57,Citation58,Citation60,Citation62–64,Citation67,Citation73–76], but also having an awareness that not all resources provide accurate and reliable information (particularly on the Internet) [Citation10,Citation50,Citation51,Citation58,Citation63,Citation73]. In contrast, some patients found reading too much distressing and depressing [Citation7,Citation50,Citation51,Citation53,Citation58,Citation62,Citation67]; (8) Accepting and claiming the diagnosis and new identity, as well as the uncertainties and possible changes/losses that MS may bring [Citation7,Citation8,Citation14,Citation47,Citation49,Citation51–54,Citation57,Citation59,Citation61–63,Citation67,Citation68,Citation75]; (9) Denying or refusing the diagnosis and the new identity, avoiding reminders of MS and disability, rejecting support or using aids [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11,Citation47,Citation49,Citation51,Citation52,Citation54,Citation57,Citation58,Citation60–62,Citation64,Citation65,Citation67,Citation68,Citation73–76]; and (10) Concealing the diagnosis to protect others from grief, rage and distress [Citation8,Citation45,Citation49,Citation66,Citation76], to protect self from expressions of pity, rejection and stigmatisation and maintain a sense of normality [Citation45,Citation46,Citation49,Citation51,Citation57,Citation61,Citation62,Citation65,Citation66,Citation75], and due to the lack of public awareness and misconception, and the possibility of being ostracised and judged [Citation45,Citation46,Citation49,Citation57,Citation61,Citation65,Citation74].

Making sense

Another theme evident from the synthesis was sense making, reported in 31 papers, which encompassed attempts to develop explanations and meanings for adversity around the MS diagnosis. People reported embarking on a “journey of inquiry” [Citation74,p.437] where they attempted to understand the cause of their MS and make sense of the ambiguous and mostly transient pre-diagnosis symptoms to protect themselves from undue anxiety, fear and distress [Citation14,Citation49,Citation50,Citation55,Citation61,Citation67,Citation74,Citation75]. Some people had an awareness that there was something potentially seriously wrong with their health, which prompted them to search for a cause and explanation [Citation14,Citation50,Citation54,Citation55,Citation67,Citation74,Citation75]. While some attempted to provide simple non-threatening explanations for their symptoms during the pre-diagnostic period [Citation50,Citation68,Citation74], others attributed their symptoms to life threatening illnesses (e.g., brain tumour) causing fear and anxiety [Citation51,Citation74,Citation75].

For many, receiving the diagnosis, or learning about the possibility of MS immediately evoked frightful images and overwhelming thoughts of wheelchairs, disability, dependency and death [Citation7,Citation11,Citation45,Citation49,Citation52,Citation57,Citation59,Citation61,Citation66,Citation75]. Such negative perceptions threatened their roles and sense of self as an independent being, leading to anxiety over the future and further negative emotions. Some people with MS perceived that successful adjustment to diagnosis would only be possible in the context of no severe symptoms, and thought that they would not be able to deal with the disability and dependency if their disease progressed [Citation7,Citation59]. Forming negative perceptions might be partially related to their lack of knowledge or misinformation about MS at the time of diagnosis [Citation8,Citation45,Citation46,Citation54,Citation56,Citation57,Citation61,Citation62,Citation65–67,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75]. Some defined MS diagnosis as a period of uncertainty, which caused distress, anxiety, depression, and led to feeling helpless and out of control [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11,Citation14,Citation48–51,Citation53–55,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation64,Citation65,Citation67,Citation68,Citation72,Citation74,Citation75]. They expressed confusion about the unpredictability of symptoms and the nature of MS itself [Citation49–51,Citation53,Citation61,Citation66,Citation67,Citation74,Citation75]. This limited their ability to make sense of their MS diagnosis and how they appraised their illness.

Coherence also emerged in 22 papers as an important factor in adjustment and the response to diagnosis [Citation7,Citation8,Citation11,Citation14,Citation49–51,Citation53–55,Citation57,Citation59,Citation61–63,Citation65–68,Citation72,Citation74,Citation75]. Coherence is defined as the extent to which patients understand or make sense of their diagnosis in a coherent way through the realisation of what is happening, perceived resources and the ability to find meaning of life with MS. For instance, some people acknowledged the irreversible nature of MS diagnosis and the need to adjust to the subsequent changes in their health and lives (e.g., [Citation8,Citation14,Citation49,Citation51,Citation55,Citation61,Citation65,Citation67,Citation74,Citation75]). They came to accept the MS and its inevitable future consequences, even though the future was clouded by the uncertainty and lack of adequate support [Citation7,Citation49,Citation50,Citation53,Citation54,Citation61,Citation65,Citation66,Citation68,Citation75]. Patients became aware of their disrupted sense of self (i.e., pre-diagnosis self) and acknowledged the need for the integration of MS into their new self [Citation7,Citation14,Citation49,Citation51,Citation53,Citation54,Citation57,Citation59,Citation61–63,Citation65,Citation67,Citation68,Citation75]. On the other hand, some patients were reluctant to integrate MS into their sense of self, as they perceived diagnosis as a threat to their quality of life, goals and self-image [Citation14,Citation57,Citation62,Citation65,Citation75].

Support and information needs of people around MS diagnosis

This overarching third-order theme encompassed the emotional and informational support needs of people around the point of MS diagnosis.

Emotional support needs

People with MS indicated that their emotional needs were often ignored at the time of diagnosis, leaving them waiting, worrying and wondering (e.g., [Citation14,Citation55,Citation59,Citation61,Citation74,Citation75]). They described feeling lonely and abandoned due to lack of support from health professionals, friends and family [Citation7,Citation11,Citation14,Citation47,Citation50,Citation52,Citation59,Citation61,Citation74,Citation75]. They felt that they needed emotional support to be better able to manage negative emotional reactions and deal with negative attitudes of other people, to come to terms with the diagnosis, to empower them and increase their self-efficacy, and to develop new meaningful post-diagnosis identities [Citation45,Citation46,Citation48,Citation50,Citation52,Citation53,Citation55–57,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation64,Citation65,Citation67–70,Citation74,Citation75]. Some patients described experiencing mood problems (e.g., depression, anxiety) and having suicidal thoughts pre-diagnosis or immediately after the diagnosis, which were sometimes unrecognised or ignored by health professionals, or left untreated [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation45,Citation59,Citation65,Citation68,Citation74,Citation75]. Therefore, there was a sense that around the time people were being diagnosed with MS, their emotional state and needs should also have been assessed, monitored, and if required, adequately treated (e.g., [Citation61,Citation68]).

There were consistent findings among 25 papers regarding the need for ongoing, therapeutic and rewarding interactions and support from health professionals. People with MS consistently reported that they needed their health professionals to be sensitive to their needs and to their reactions to dealing with the diagnosis (e.g., [Citation7,Citation10,Citation11,Citation14,Citation45–47,Citation53,Citation59,Citation61,Citation62,Citation65,Citation69,Citation74,Citation75]), to devote adequate time to them [Citation11,Citation14,Citation46,Citation53,Citation61,Citation74], to listen to their concerns [Citation10,Citation46,Citation50,Citation53,Citation61,Citation75], to acknowledge their reporting of symptoms [Citation50,Citation75], and to be open and frank with them [Citation50,Citation64]. There was a need for caring and understanding health professionals who recognised that everyone’s experience of MS is unique [Citation7,Citation8,Citation10,Citation45–47,Citation52,Citation53,Citation55,Citation61,Citation62,Citation64,Citation68,Citation70,Citation75,Citation76]. Patients wanted to be informed of the diagnosis clearly and unambiguously as soon as this was available, in an appropriate setting without distractions and interruptions [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation61,Citation69,Citation74]. Need for a follow-up session with the neurologist after receiving the diagnosis was also consistently highlighted by patients [Citation10,Citation11,Citation46,Citation48,Citation52,Citation74,Citation76].

Eight studies revealed that there was a need for ongoing supportive interventions that are sensitive to people’s individual needs and focus on learning strategies for coping with the negative emotions and thoughts, and improving confidence, communication, achievement of various goals and tasks, and adjustment to the diagnosis [Citation7,Citation10,Citation14,Citation48,Citation52,Citation61,Citation63,Citation75]. However, some people with MS questioned the suitability of such interventions for the newly diagnosed, and suggested that they would be more suitable and useful during the time when people start to experience more serious challenges [Citation52]. They also felt that the type of psychological support needed to fit with their views about a specific therapy, or they needed to ‘buy into’ the rationale for the therapy [Citation52].

There were conflicting findings in the studies with regards to getting support and information from MS organisations and other people with MS. Some patients felt the need to get in touch with other people and use services provided by MS organisations [Citation7,Citation56,Citation57,Citation60,Citation62,Citation63,Citation67,Citation74,Citation76]. They also found this a positive experience. Others, however, felt the need to avoid other people with MS as they found the exposure to reminders of MS (particularly seeing others with severe disabilities) threatening and distressing [Citation7,Citation45,Citation49,Citation57,Citation62,Citation74,Citation75]. Some people did not wish to be a member of a ‘stigmatised’ group [Citation7] with a ‘disabled identity’ [Citation49] and were also scared to witness decline and disability [Citation62].

Informational needs

Ten studies highlighted that many people with MS reported needing information on the diagnosis process and the tests undertaken during the pre-diagnosis period (particularly from competent health professionals) [Citation7,Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation61,Citation64,Citation68–70,Citation74]. Once they received the diagnosis, they wanted information about MS (its causes, symptoms, prognosis, treatment and management) [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation45,Citation55,Citation58,Citation61,Citation62,Citation64,Citation68,Citation69,Citation74,Citation75]. The information provided needed to be pertinent, personalised and balanced (including pros and cons of undergoing diagnostic tests or different treatments) [Citation10,Citation53,Citation61–64,Citation69,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75]. They wished to receive high quality information in different formats (e.g., face-to-face, written, and electronic) in simple, direct and understandable language [Citation10,Citation63,Citation74]. One paper reported that some patients preferred to initially receive information from the neurologists as they considered them to have the most accurate information [Citation64].

Additionally, the timing of providing information was important [Citation58,Citation62,Citation64,Citation69,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75]. One paper highlighted that providing detailed information at the time of the diagnosis might not always be optimal as people with MS were often shocked and were unable to process the information [Citation74]. Eight papers reported that raising the possibility of MS before a definite diagnosis may help prepare the individuals for receiving the diagnosis later [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation61,Citation64,Citation68,Citation69,Citation74]. They also suggested the need to have a follow-up session to give an opportunity to process the information about the diagnosis and ask illness-specific questions [Citation8,Citation10,Citation63,Citation64,Citation74]. Some people expressed a need to be signposted to services that could help to improve their quality of life [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation56,Citation61,Citation62,Citation74]. There was a need for a timely provision of information about support groups, resources, and contact details of local MS charities. Seven papers revealed that using educational interventions and/or information aids could facilitate providing timely, personalised and pertinent information to people with MS at the time of the diagnosis [Citation10,Citation62,Citation64,Citation69,Citation70,Citation74,Citation75].

Line of argument

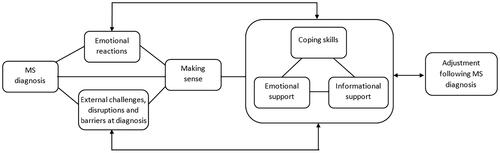

summarises our line of argument and presents a conceptual organisation of the third-order themes and sub-themes identified in this synthesis, explaining how they can be understood together in the context of adjustment following MS diagnosis. The figure shows the dynamic relationships between different factors in relation to adjustment following MS diagnosis. The arrows and lines between different factors, responses and modifiers do not imply causation or a strict temporal sequence, so should be treated cautiously and as ‘links’. We found that people experience several negative emotions and external challenges, disruptions and barriers around the time of diagnosis, which might limit their ability to make sense of MS diagnosis and to adjust to this new and uncertain situation. However, coping and helpful resources might help reduce the negative impact of being diagnosed and facilitate the adjustment process around the period of MS diagnosis. Our line of argument also highlights the dynamic nature of the adjustment following MS diagnosis as the amount of stress varies over time due to changes to the people’s appraisal of the external factors and the available resources, making adjustment following MS diagnosis more difficult at times than others.

Figure 2. A conceptual map of adjustment following MS diagnosis, representing the dynamic relationships between the themes identified from the synthesis.

Discussion

Our meta-synthesis of 24 years of published qualitative research (37 papers in total) provided insight into the experiences of people with MS receiving a diagnosis, and has shown that individuals are confronted with many challenges and changes to their lives around this point. Our conceptual map resulting from the line of argument synthesis highlights how these challenges and disruptions can threaten people’s sense of self and meaningfulness, resulting in various negative emotions. It also highlights that people need to engage in adaptive coping strategies and should have access to various support resources, information and advice to adjust to the difficulties of the diagnosis period, and to restore meaning, goals and self-worth.

In line with the generic stress and coping models [Citation23], we found that the adjustment to the MS diagnosis might be mediated by how people appraise their diagnosis and how they evaluate and use the available resources. Although our conceptual map comprises similar constructs to generic stress and coping models (stressors, appraisal and coping resources), supporting their utility in explaining adjustment to MS diagnosis, it also emphasises that the associations between these constructs are complex and dynamic in nature.

The generic stress and coping models are often criticised for underestimating the complexity of associations between relevant constructs [Citation24,Citation25]. Consistently, we found that stress appraisal at the time of the diagnosis constantly changes with time and with a number of internal (e.g., emotions, belief and expectations) and external processes (e.g., uncertainties around diagnosis, duration of the diagnostic process). Our findings suggest that at the time of the MS diagnosis people may go through emotional stages similar to Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’s [Citation77] five stages of grieving (i.e., denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance). The way people make sense of and conceptualise their diagnosis and how they cope with the diagnosis were found to be interrelated with the emotional stage people were going through. Similar to Kübler-Ross’ model, our findings suggest that these emotional reactions do not necessarily have an order, nor are all emotions experienced by all newly diagnosed people.

Our findings demonstrated that people may experience several emotions in a roller coaster effect, switching between different emotions or experiencing different emotions at the same time, returning to one or more stages several times before adjusting to the diagnosis. This suggests that adjusting to the MS diagnosis exists on a continuum, not in a single time point as suggested within the generic stress and coping models, and can be affected by personal, societal and environmental factors.

Cognitive appraisal of being diagnosed with MS and the sense-making process individuals go through may be considered within the conceptual definitions of illness representations [Citation78], which are central to Leventhal’s self-regulation theory [Citation79,Citation80]. Self-regulation theory emphasises that illness representations (perceptions of an illness in terms of identity, timeline, consequences, causes, control/cure, and coherence) determine an individual’s appraisal of an illness situation. According to this theory, a person’s appraisal of an illness can be a result of both cognitive and emotional processes [Citation78]. Illness representations have been postulated to be important predictors of various aspects of self-regulation, such as adjustment, treatment adherence, and the use of and intention to use of services [Citation81–83].

Previous research supports the application of the illness representations to MS and shows that illness representations contribute to outcomes such as general psychosocial adjustment to MS [Citation21,Citation84], health-related quality of life [Citation85,Citation86], self-management [Citation87], and health service utilisation [Citation83]. Our review also highlights the ways in which illness representations of newly diagnosed people are important in understanding the adjustment to the diagnosis of MS (e.g., coherence, meaning people ascribe to the pre-diagnostic symptoms, understanding of MS and its unpredictable symptoms and disease course). Newly diagnosed individuals’ beliefs and perceptions of their MS diagnosis (including illness representations) may influence the extent to which they accept their diagnosis, and may indicate how they will respond to the diagnosis. For instance, where people had negative or false beliefs or perceptions regarding their MS and the consequences of MS, this resulted in diagnosis concealment or delayed support seeking.

Affective responses to unpredictability in MS have been previously identified [Citation30]. In our review, perceiving MS as unpredictable (control/cure) and its progressive nature (i.e., timeline) were associated with an understanding that part of the new diagnosis and their new identity (i.e., changes in pre-diagnosis self) requires taking control, acknowledging the irreversible nature of MS diagnosis, and finding a coherent meaning to life with MS. These findings indicate that illness representations may provide a framework for the formulation of interventions to support newly diagnosed people and guide the development of tailored support services and/or resources. As such, investigating individuals’ illness representations (i.e., accurate/inaccurate or helpful/unhelpful beliefs about their diagnosis, such as its cause, consequences, timeline and treatment prospects) and the beliefs underlying their behavioural responses (i.e., adaptive/maladaptive) could contribute to tailoring interventions to individual needs.

Our meta-synthesis demonstrated that coping resources (i.e., coping skills, emotional and informational support) could play a mediating and moderating role in the relationship between perceived stress and adjustment. Our findings revealed that the most frequently adopted coping strategies were: avoidance, denial, and concealing the diagnosis. People also often appraised the diagnosis as threatening due to unhelpful illness representations and limited information about MS. However, adopting such maladaptive coping strategies and having unhelpful negative thoughts might lead to adjustment difficulties. Previous evidence demonstrated certain avoidant emotion-focused coping strategies are linked to worse adjustment, whereas engaging in problem-focused coping techniques is related to better adjustment [Citation88,Citation89]. Although some people relied on adaptive coping strategies (e.g., acceptance, seeking information and having a positive mental attitude) which were empowering in the short-term, in the absence of appropriate emotional and informational support resources, such individually identified coping strategies can become burdensome over time [Citation55]. Therefore, it is equally important to provide useful support at the right time. However, current evidence showed that people did not receive appropriate support, or that this was sporadically provided.

In addition, our meta-synthesis highlighted several emotional and informational support needs of people with MS around the time of the diagnosis which were not being addressed, indicating there is a clear need for emotional support and advice during this period. Furthermore, there appears to be a gap between clinics and the MS charities as there are no evidence-based referral pathway available to triage people (based on their needs) to the wider support resources which could potentially help people adjust to MS diagnosis. Moreover, our meta-synthesis revealed that people at the time of diagnosis, and at the early stages of MS, typically avoid contacting MS charities for fear of witnessing decline and disability in others, as they find the exposure to such reminders as threatening and distressing. Therefore, people often prefer first to receive information and support from competent healthcare professionals around the diagnosis (who they may have already had a contact with during the diagnosis period), and choose to use the services provided by the MS charities further ‘down the road’ when their illness has progressed or when they have incorporated their MS identity within their lives. Johnson [Citation11] suggested that the diagnostic phase should be communicated as a transition from the MS clinics to wider services and resources. Consequently, there needs to be a pathway in place to allow a transition from clinic to MS charities (and back), and to provide timely emotional support and advice to people around the point of MS diagnosis.

Limitations and strengths

Our meta-synthesis relied on the quality of the included qualitative papers. The included papers were frequently limited by inadequate reporting of sampling techniques, ethical considerations and researchers’ reflexivity on how their own preconceptions and context of understanding affected data generation and analysis, which raises concerns about transparency and rigour. It is therefore crucial that future qualitative studies follow formal reporting guidelines such as Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research [Citation90] to improve transparency. Other limitations of the synthesis included excluding the grey literature (e.g., conference abstracts), printed publications that have yet to be incorporated into online databases and papers published in languages other than English, meaning some potentially important and relevant literature may have been missed. In addition, although we included 37 papers, these represented only 35 studies as some papers drew from the same data. Synthesising papers that use the same data might result in over-representing certain first- and second-order constructs, limiting the representativeness of our findings [Citation37].

Meta-ethnographic synthesis is interpretive in nature, and therefore, can be prone to bias [Citation37]. We also acknowledge that we were interpreting other authors’ accounts of views and experiences of people with MS when synthesising the included papers. It is possible that a different review team might have arrived at a different conclusion and developed a different conceptual map. However, this was mitigated by having several reviewers with varied backgrounds, who discussed and challenged each other’s interpretations when arbitrating and arriving at a consensus. The third-order constructs (our own interpretations of raw data and authors’ interpretations) were cross-verified independently by all the reviewers to ensure the trustworthiness of our findings. In addition, the involvement of our PPI co-author and PPI members enhanced the rigour of our synthesis and provided further confidence that our interpretations are firmly centred on experiences of people with MS. Our PPI co-author was also involved at other key stages of the meta-synthesis process (e.g., identifying and formulating the research question, designing the protocol and formulating the search terms), offering a patient perspective on the meta-synthesis process as a whole which helped consolidate rigour and quality.

Furthermore, to ensure trustworthiness of findings, all key stages of the review process (e.g., screening, data extraction) were conducted by at least two reviewers independently with any discrepancies arbitrated by the wider review team. In addition, we adhered to the principles of meta-ethnography outlined by Noblit and Hare [Citation40] and Malpass et al. [Citation37] when conducting the meta-synthesis, and followed the PRISMA guidelines [Citation34] to ensure completeness, transparency and rigour in methodology and reporting. By synthesising existing qualitative literature on diagnosis experiences of people with MS, a more comprehensive overview of potentially relevant determinants of adjustment to MS diagnosis were derived which could have been difficult to obtain through the findings from each of the individual studies.

Conclusion

We present a conceptual understanding of adjustment following MS diagnosis explaining the dynamic relationships between psychosocial factors, which could be utilised when developing support interventions for people around the point of MS diagnosis. Our review revealed that many newly diagnosed people with MS had unmet emotional and informational needs and required support and advice to help them cope with the MS diagnosis. Interventions focusing on developing acceptance by coming to terms with difficult thoughts and feelings (e.g., Acceptance and Commitment Therapy) might be particularly beneficial in developing and practicing more adaptive ways of responding to the diagnosis. Designing effective person-centred interventions that avoid a one-size-fits-all approach and are tailored to people’s needs could also facilitate the adjustment to MS diagnosis and contribute to enhancing patients’ health and wellbeing. In the absence of tailored support and information, people are likely to perceive available services as irrelevant, which may lead them to either reject the support or accept it reluctantly, which in turn could reduce their potential benefits. Having access to a point of contact who is able to provide newly diagnosed people with tailored support and advice, provide relevant information around MS and services as required, and make appropriate referrals to key health and social care services when necessary, could also improve adjustment to MS diagnosis.

Appendices_Supplemental_materials_revised.docx

Download MS Word (79.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anita Rose, Karen Vernon, Jeanette Eldridge, Farhad Shokraneh, Abigail Methley, Olga Klein and the Multiple Sclerosis Patient and Public Group members for their contributions.

Disclosure statement

RdN is an author in one study that was included in this meta-synthesis. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atlas of MS 3rd Edition [Internet]. London: Multiple Sclerosis International Federation; 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.msif.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Atlas-3rd-Edition-Epidemiology-report-EN-updated-30-9-20.pdf

- Solomon AJ, Corboy JR. The tension between early diagnosis and misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(9):567–572.

- Brownlee WJ, Hardy TA, Fazekas F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1336–1346.

- Gates P. Clinical neurology: a primer. Chatswood: Elsevier Australia; 2010.

- Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162–173.

- Solomon AJ, Pettigrew R, Naismith RT, et al. Challenges in multiple sclerosis diagnosis: Misunderstanding and misapplication of the McDonald criteria. Mult Scler. 2021;27(2):250–258.

- Dennison L, Yardley L, Devereux A, et al. Experiences of adjusting to early stage multiple sclerosis. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(3):478–488.

- Edwards RG, Barlow JH, Turner AP. Experiences of diagnosis and treatment among people with multiple sclerosis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008;14(3):460–464.

- Giordano A, Granella F, Lugaresi A, et al. Anxiety and depression in multiple sclerosis patients around diagnosis. J Neurol Sci. 2011;307(1-2):86–91.

- Solari A, Acquarone N, Pucci E, et al. Communicating the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis - a qualitative study. Mult Scler. 2007;13(6):763–769.

- Johnson J. On receiving the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: managing the transition. Mult Scler. 2003;9(1):82–88.

- Köpke S, Solari A, Khan F, et al. Information provision for people with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 10(10):CD008757.

- Methley AM, Chew-Graham C, Campbell S, et al. Experiences of UK health-care services for people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic narrative review. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):1844–1855.

- Strickland K, Worth A, Kennedy C. The liminal self in people with multiple sclerosis: an interpretative phenomenological exploration of being diagnosed. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(11-12):1714–1724.

- Solari A. Effective communication at the point of multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20(4):397–402.

- Topcu G, Griffiths H, Bale C, et al. Psychosocial adjustment to multiple sclerosis diagnosis: a Meta-review of systematic reviews. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;82:101923.

- Craig P, Medical Research Council Guidance, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

- Nolan M, Ryan T, Enderby P, et al. Towards a more inclusive vision of dementia care practice and research. Dementia. 2002;1(2):193–211.

- Rothman AJ. "Is there nothing more practical than a good theory?": Why innovations and advances in health behavior change will arise if interventions are used to test and refine theory. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2004;1(1):11.

- Pakenham KI. Adjustment to multiple sclerosis: application of a stress and coping model. Health Psychol. 1999;18(4):383–392.

- Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. A review of psychological correlates of adjustment in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(2):141–153.

- Kehler MD. Emotional Adjustment to Multiple Scleoris: Evaluation of a stress and coping model and a cognitive adaptation model [dissertation]. Regina (CA): University of Regina; 2013.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York (NY): Springer; 1984.

- Goldsworthy B, Knowles S. Caregiving for parkinson's disease patients: an exploration of a stress-appraisal model for quality of life and burden. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63(6):P372–P376.

- Zarit SH. Do we need another "stress and caregiving" study? Gerontologist. 1989;29(2):147–148.

- Harkness AMB, Long BC, Bermbach N, et al. Talking about work stress: Discourse analysis and implications for stress interventions. Work Stress. 2005;19(2):121–136.

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Coping as a mediator of emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(3):466–475.

- Dennison L. Factors and Processes involved in Adjustment to Multiple Sclerosis [dissertation]. Southampton (UK): University of Southampton; 2011.

- Soundy A, Roskell C, Elder T, et al. The psychological processes of adaptation and hope in patients with multiple sclerosis: a thematic synthesis. OJTR. 2016;04(01):22–47.

- Wilkinson HR, das Nair R. The psychological impact of the unpredictability of multiple sclerosis: a qualitative literature Meta-synthesis. Br J Neurosci Nurs. 2013;9(4):172–178.

- Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C. Focus on qualitative methods. Qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and techniques. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(4):365–371.

- Shaw RL. Conducting literature reviews. In: Forrester M, editor. Doing qualitative research in psychology: a practical guide. London: Sage; 2010. p. 39–52.

- Shaw RL. Identifying and synthesizing qualitative literature. In: Harper D, Thompson AR, editors. Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: a guide for students and practitioners. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. p. 9–22.

- Moher D, PRISMA Group, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

- CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [Internet]. Oxford (UK): Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 18]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Dixon-Woods M, Sutton A, Shaw RL, et al. Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(1):42–47.

- Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, et al. "Medication career" or "moral career"? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients' experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(1):154–168.

- Bennion AE, Shaw RL, Gibson JM. What do we know about the experience of age related macular degeneration? A systematic review and Meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(6):976–985.

- Topcu G, Buchanan H, Aubeeluck A, et al. Caregiving in multiple sclerosis and quality of life: a Meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Psychol Health. 2016;31(6):693–710.

- Noblit GW. Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: Synthesising qualitative studies. London: Sage; 1988.

- Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, et al. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(4):209–215.

- Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M, et al. Evaluating Meta-ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(43):1–164.

- Ring NA, Ritchie K, Mandava L, et al. A guide to synthesising qualitative research for researchers undertaking health technology assessments and systematic reviews [Internet]. Edinburgh: NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (NHS QIS); 2011 [cited 2021 Nov 4]. Available from: https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/3205/1/HTA_MethodsofSynthesisingQualitativeLiterature_DEC101.pdf

- Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, et al. Conducting a Meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):21.

- Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Ghafari S, Nourozi K, et al. Confronting the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study of patient experiences. J Nurs Res. 2014;22(4):275–282.

- Ghafari S, Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Nourozi K, et al. Patients' experiences of adapting to multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Contemp Nurse. 2015;50(1):36–49.

- Ceuninck van Capelle Ad, de Ceuninck van Capelle A, Visser LH, Vosman F. Multiple sclerosis (MS) in the life cycle of the family: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the perspective of persons with recently diagnosed MS. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34(4):435–440.

- Ceuninck van Capelle Ad, Ceuninck van Capelle A. D, Meide H. V D, Vosman FJH, et al. A qualitative study assessing patient perspectives in the process of decision-making on disease modifying therapies (DMT's) in multiple sclerosis (MS. ). PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182806–e.

- Finlay L. The intertwining of body, self and world: a phenomenological study of living with recently-diagnosed multiple sclerosis. J Phenomenol Psychol. 2003;34(2):157–178.

- Fawcett TN, Lucas M. Multiple sclerosis: living the reality. Br J Nurs. 2006;15(1):46–51.

- Bogosian A, Moss-Morris R, Yardley L, et al. Experiences of partners of people in the early stages of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2009;15(7):876–884.

- Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Yardley L, et al. Change and processes of change within interventions to promote adjustment to multiple sclerosis: Learning from patient experiences. Psychol Health. 2013;28(9):973–992.

- Koffman J, Goddard C, Gao W, et al. Exploring meanings of illness causation among those severely affected by multiple sclerosis: a comparative qualitative study of black caribbean and white british people. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:13.

- Strickland K, Worth A, Kennedy C. The experiences of support persons of people newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis: an interpretative phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(12):2811–2821.

- Frost J, Grose J, Britten N. A qualitative investigation of lay perspectives of diagnosis and self-management strategies employed by people with progressive multiple sclerosis. Health (London)). 2017;21(3):316–336.

- Hepworth M, Harrison J. A survey of the information needs of people with multiple sclerosis. Health Informatics J. 2004;10(1):49–69.

- Barker AB, Smale K, Hunt N, et al. Experience of identity change in people who reported a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a qualitative inquiry. Int J MS Care. 2019;21(5):235–242.

- Manzano A, Eskytė I, Ford HL, et al. Impact of communication on first treatment decisions in people with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(12):2540–2547.

- Hunter R, Parry B, Thomas C. Fears for the future: a qualitative exploration of the experiences of individuals living with multiple sclerosis, and its impact upon the family from the perspective of the person with MS. Br J Health Psychol. 2021;26(2):464–481.

- Sullivan MJL, Mikail S, Weinshenker B. Coping with a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Can J Behav Sci. 1997;29(4):249–256.

- Koopman W, Schweitzer A. The journey to multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. J Neurosci Nurs. 1999;31(1):17–26.

- Lowden D, Lee V, Ritchie JA. Redefining self: Patients' decision making about treatment for multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2014;46(4):E14–E24.

- Bansback N, Chiu JA, Carruthers R, et al. Development and usability testing of a patient decision aid for newly diagnosed relapsing multiple sclerosis patients. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):173.

- Borreani C, SIMS-Trial group, Giordano A, Falautano M, et al. Experience of an information aid for newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis patients: a qualitative study on the SIMS-Trial. Health Expect. 2014;17(1):36–48.

- Giovannetti AM, Brambilla L, Clerici VT, et al. Difficulties in adjustment to multiple sclerosis: vulnerability and unpredictability of illness in the foreground. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(9):897–903.

- Roshangaran F, Masoudi R. Exposure experience of the families with MS patients to the disease: Struggle for admission of disease. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2016;5(7):171–178.

- Russell CS, White MB, White CP. Why me? Why now? Why multiple sclerosis? Making meaning and perceived quality of life in a midwestern sample of patients with multiple sclerosis. Fam Syst Health. 2006;24(1):65–81.

- Loveland CA. The experiences of african americans and Euro-Americans with multiple sclerosis. Sex Disabil. 1999;17(1):19–35.

- Heesen C, Schaffler N, Kasper J, et al. Suspected multiple sclerosis - what to do? Evaluation of a patient information leaflet. Mult Scler. 2009;15(9):1103–1112.

- Brand J, Kopke S, Kasper J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis-patients' experiences, information interests and responses to an education programme. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113252.

- Vijayasingham L, Jogulu U, Allotey P. Work change in multiple sclerosis as motivated by the pursuit of illness-work-life balance: a qualitative study. Mult Scler Int. 2017;2017:8010912.

- Vijayasingham L. Work right to right work: an automythology of chronic illness and work. Chronic Illn. 2018;14(1):42–53.

- Russell RD, Black LJ, Sherriff JL, et al. Dietary responses to a multiple sclerosis diagnosis: a qualitative study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(4):601–608.

- Barker-Collo S, Cartwright C, Read J. Into the unknown: the experiences of individuals living with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006;38(6):435–446.

- Isaksson A, Ahlstrom G. From symptom to diagnosis; illness experience of multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006;38(4):229–237.

- Satinovic M. Remodelling the life course: Making the most of life with multiple sclerosis. Grounded Theory Rev. 2017;16(1):26–37.

- KüBler-Ross E. On death and dying. New York: The Macmillan Company; 1969.

- Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn Ther Res. 1992;16(2):143–163.

- Leventhal H. Findings and theory in the study of fear communications. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1970;5:119–186.

- Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, editor. Medical psychology. Vol 2. New York: Pergamon Press; 1980. p. 7–30.

- Hagger MS, Orbell S. A Meta-Analytic review of the Common-Sense model of illness representations. Psychol Health. 2003;18(2):141–184.

- Petrie K, Weinman J. Why illness perceptions matter. Clin Med (Lond)). 2006;6(6):536–539.

- Glattacker M, Giesler JM, Klindtworth K, et al. Rehabilitation use in multiple sclerosis: Do illness representations matter? Brain Behav. 2018;8(6):e00953.

- Jopson NM, Moss-Morris R. The role of illness severity and illness representations in adjusting to multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(6):503–511.

- Spain LA, Tubridy N, Kilpatrick TJ, et al. Illness perception and health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116(5):293–299.

- Wilski M, Tasiemski T. Health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: role of cognitive appraisals of self, illness and treatment. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(7):1761–1770.

- Wilski M, Tasiemski T. Illness perception, treatment beliefs, self-esteem, and self-efficacy as correlates of self-management in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016;133(5):338–345.

- Kvillemo P, Bränström R. Coping with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112733.

- Shakeri J, Kamangar M, Ebrahimi E, et al. Association of coping styles with quality of life in cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2015;21(3):298–304.

- Tong A, Craig J, Sainsbury P. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.