?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose

To describe patients’ perspectives of collagenase injection or needle fasciotomy for Dupuytren disease (DD) including hand therapy, and their view of hand function and occupational performance.

Materials and methods

Interviews were performed with twelve patients who had undergone non-surgical treatment and rehabilitation for DD. Data was analysed using a problem-driven content analysis using the model of Patient Evaluation Process as a theoretical framework.

Results

The participants' previous experiences influenced their expectations of the upcoming treatment and they needed information to be prepared for treatment. Treatment and rehabilitation had a positive impact on daily life and were regarded as effective and simple with quick recovery. However, there could be remaining issues with tenderness or stiffness. The participants expressed their belief in rehabilitation and how their own efforts could contribute to an improved result. Despite concerns about future recurrence participants described increased knowledge and sense of control regarding future needs.

Conclusion

Undergoing a non-surgical treatment and rehabilitation process for DD was regarded as quick and easy and can meet the need for improved hand function and occupational performance. Taking responsibility for one’s own rehabilitation was considered to influence the outcome positively. The theoretical framework optimally supported the exploration of participants’ perspective.

Treatment of Dupuytren Disease (DD) with needle/collagenase combined with hand therapy was experienced as giving fast improvement in hand function and occupational performance.

An individualized care process which satisfies the need for knowledge about the disease, prognosis, treatment options and rehabilitation can give individuals suffering from DD a sense of security.

The need for active participation in the DD care process can vary and it is crucial to listen to individuals’ opinions and needs.

Individuals can take considerable responsibility for rehabilitation after non-surgical treatment for DD and regard it as important for the outcome.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Dupuytren disease (DD) is a chronic disease affecting the palmar aponeurosis of the hand and leads to cords creating flexion contractures and an inability to extend the finger joints. The ulnar fingers, little and ring finger, are most frequently affected, which impairs the grip function of the hand [Citation1]. The precise aetiology of the disease remains unknown but a strong heredity has been shown and risk factors associated with DD include smoking, diabetes and alcohol consumption [Citation2,Citation3]. The prevalence of DD varies globally between 3% and 42%, and Northern Europe demonstrates a higher rate [Citation1]. The prevalence increases with rising age and DD is more common among males [Citation4], for example in Sweden where 10% of men and 2% of women at the age of 55 years, has the disease [Citation5].

The flexion contractures caused by DD affects hand function, occupational performance, and quality of life [Citation6–10] and can affect self-confidence, participation, and interaction with others [Citation6,Citation7,Citation9,Citation10]. Surgical and non-surgical (needle fasciotomy or collagenase injection) corrective treatment methods exist for DD and can improve finger extension [Citation11–13]. During surgical treatment the affected tissue in the hand is removed. Needle fasciotomy involves sectioning of the cords, and treatment with collagenase injection leads to lysis of the collagen within the diseased tissue. However, regardless of treatment method, the disease cannot be cured and recurrence in treated fingers is common [Citation14–16].

Hand therapy is usually part of corrective treatment of Dupuytren disease (DD) [Citation17]. The extent of hand therapy after corrective treatment varies depending on the treatment procedure and the patient’s needs [Citation18]. Previous research on corrective treatment and hand therapy for DD has shown that corrective treatment improves finger joint extension, functioning and quality of life [Citation14,Citation19–25] but few studies have examined the patients’ subjective perspectives on the results or the treatment process [Citation8,Citation26]. Qualitative studies of patient experiences after surgical treatment of DD [Citation8,Citation26] have demonstrated the complexity in patients’ evaluation of care and results, where functional status is only one factor of importance for how patients’ value their result. Equally important was experiences of the structure and process of the treatment, that is material, human and organisational resources and interprofessional relations like information and communication [Citation8]. A positive experience of care for DD among patients has also shown a strong correlation with communication, post-operative care, and information about the treatment process. This correlation was strong regardless of treatment method and whether patients had a remaining extension deficit [Citation27]. Thus, optimising experiences of the care process can be one way of improving treatment outcomes and quality of care [Citation8].

There is an increasing need for studies in hand therapy regarding the quality of care and treatment for hand conditions [Citation28]. Collagenase injection or needle fasciotomy treatment for DD is considered as less demanding for the patient compared to a surgical treatment process as the latter involves longer time for recovery of hand function and more complications [Citation13,Citation29–31]. However, there is a lack of knowledge regarding patients’ subjective experiences of undergoing non-surgical treatment for DD and their view of outcomes on hand function and occupational performance. Furthermore, the importance of hand therapy after non-surgical treatment has not been fully explored [Citation32]. Therefore, it is valuable to illuminate patients’ subjective perspective on the results and the care process after non-surgical treatment. The aim of this study was to describe patients’ perspectives of collagenase injection or needle fasciotomy for Dupuytren disease (DD) including hand therapy, and their view of hand function and occupational performance.

Methods

Study design

This was a qualitative interview study with a descriptive design where problem-driven content analysis [Citation33] with a deductive-inductive approach was applied for analysis of data. To understand patients’ experiences of a non-surgical treatment process, the model of Patient Evaluation Process was used as a theoretical framework during the data collection and analysis [Citation34].

Theoretical framework

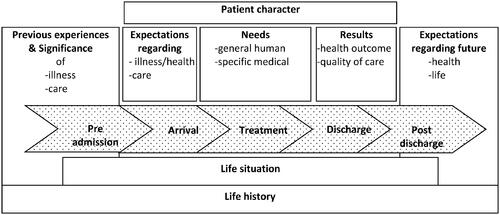

The model of Patient Evaluation Process () describes five phases that individuals undergo during a treatment process, and factors which can affect the experiences of care and treatment results. In the model, Krevers et al. (2002) [Citation34] describe patients’ evaluation of care and treatment results as a flexible rather than a linear process, which is influenced by the patients’ previous experiences of disease and care, expectations, subjective needs, the individuals’ life situation and life history and patient characters. Needs are described in the model as general human or specific medical needs. Human needs are the physical and psychosocial needs that exist in life, while the specific medical needs are related to the actual planned treatment. Patients’ evaluation of care is also affected by patient character, which is the patients’ description of themselves and their participation in decision-making, communication, and interaction with staff during their care and rehabilitation [Citation34]. Four patient characters are described in the model: active, passive, tolerant and frustrated [Citation34], and a fifth patient character has been identified in research using the model: eager [Citation35].

Figure 1. The model of Patient Evaluation Process published in Krevers, Närvänen, Öberg. Patient evaluation of the care and rehabilitation process in geriatric hospital care. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2002, 24(9):482-491. Reprinted with permission from the copyright holder, www.tandfonline.com.

Context and researchers’ position

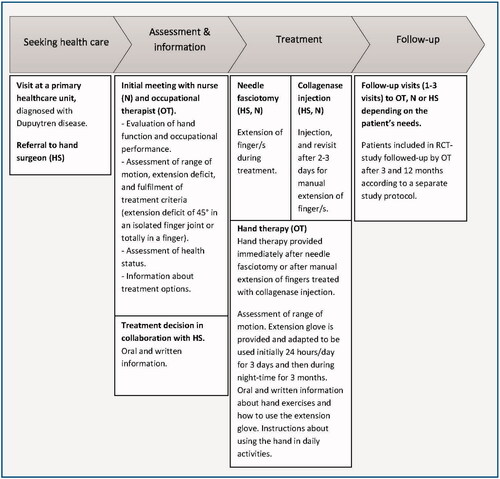

This study is part of a larger research project on outcomes of treatment and rehabilitation after hand and wrist diagnoses, where DD is one of these. All participants in this study underwent an outpatient care process at a specialist clinic for hand surgery within the public health care system. All participants received non-surgical treatment for DD, with needle fasciotomy or collagenase injection followed by hand therapy. The hand surgeon made the decision about corrective treatment based on the severity of DD and the individual patient. The hand therapy protocol was the same for all participants regardless of treatment procedure (). The participants had contact with an occupational therapist prior to and immediately after the non-surgical treatment. They received verbal and written information about hand exercises to be carried out regularly throughout the day. They were allowed to use the hand in daily activities three days after treatment and they were instructed to use an extension glove with the treated finger in a fully extended position during the night for three months.

Figure 2. The care process for treatment with needle fasciotomy or collagenase injection for Dupuytren disease.

The authors of this study are clinicians and employees at the service and experienced in hand therapy for persons with DD. Bracketing [Citation36] by using notes and an on-going discussion was applied to handle this preunderstanding methodologically. To capture detailed experiences and descriptions from the participants, the author who performed the interviews (MW) was careful not to reveal her clinical experience and preunderstanding of DD. None of the authors have been involved in the treatment of the participants in the study.

Participants

Participants were recruited from a specialist clinic for hand surgery in the south of Sweden. Strategic sampling was applied to capture different experiences and creating a deliberately heterogeneous sample [Citation37]. Inclusion criteria for the study was age above 18 years, and men or women with experience of non-surgical treatment and rehabilitation of DD. Patients were eligible if they had received non-surgical treatment three to 12 months prior, which resulted in a total of 124 eligible patients. Patients for the study were chosen based on a review of medical records in relation to the inclusion criteria. Variation in gender and age was sought as well as an even distribution between the two different non-surgical methods. Individuals who were unable to communicate in swedish or suffering from other health issues in the upper extremities that affected their hand function, were excluded. Written invitations with information about the study were sent on four occasions (a total of 16 individuals). The eligible participants were then contacted via telephone one to two weeks after the written invitation was sent, and an appointment for the interview was set with those giving informed consent to participate in the study.

Twelve individuals gave informed consent to participate in the study, one declined participation and three did not respond to the phone call. The mean age of the participants was 72 years (±5, range 62–81 years), five were women and seven were men (). Five participants in this study were already participating in another research project and had been randomised to either needle fasciotomy or collagenase injection. All participants were retired.

Table 1. Background data on the study participants.

Data collection

The interviews were performed during the spring of 2020, 11 by telephone and one face to face at the clinic. On average, eight months (±3, range 3-12 months) had passed since the patients’ treatment for DD. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions was used during the interviews ().

Table 2. Content of the interview guide inspired by the model of Patient Evaluation Process with examples of starting questions.

The interview guide was inspired by the model of Patient Evaluation Process [Citation34] and earlier research about DD [Citation26,Citation35]. The questions concerned earlier experiences and knowledge about DD, needs and the decision to seek help, expectations, treatment and rehabilitation, hand function, occupational performance, and future expectations. Follow-up questions were asked to further explore the participants’ perspective.

A conscious interview approach [Citation38] was used during the interviews where the interviewer took care to create a situation where the participants were encouraged to develop their views. Open questions were used to gain understanding [Citation37] on how the participants experienced their treatment without revealing pre-existing thoughts of the interviewer. The interviews lasted on average 20 min (±6, range 15-33 min). Before starting the interview, the participants were asked about background data such as age, gender, disease duration, affected hand, dominant hand, type of treatment method, time since treatment and heredity. The first interview was performed as a pilot to test the interview guide. No changes were made, and this interview was included in the study. The intention was to include 15-16 participants but after 12 interviews had been performed, they were deemed to render sufficient content for the study purpose, so the data collection was stopped. All interviews were recorded digitally.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymised to protect the identity of the participants. Problem driven content analysis [Citation33] was applied and the analysis was based on predefined categories from of the model of Patient Evaluation Process [Citation34]: earlier experiences, expectations of treatment and of the future, needs and results of treatment and rehabilitation. To ensure openness to information not fitting the predefined categories, one category labelled “other” was created. The analysis was performed in two steps; first – deductively from the predefined categories; and secondly – inductively to refine the categories and create subcategories. Coding of data was performed in MS Word.

The first part of the analysis started with reading the transcribed data thoroughly to gain a sense of the whole. A deductive approach was then applied and meaning units were collected in relation to the predefined categories. Brief reflections on the meaning units were noted and used for the creation of labels (codes). In the second part of the analysis, the codes were inductively sorted into groups based on their similarities and differences and how they related to each other. Preliminary subcategories emerged for the predefined categories. The analysis continued in an iterative process, and moved between text, codes, preliminary subcategories, and main categories, to refine the categories and ensure that the analysis was based on the data and reflected the central meaning of the interviews. Regarding trustworthiness [Citation39,Citation40], investigator triangulation, where both authors were involved in the analysis and made decisions about interpretations in a collaborative work process, was applied to increase the credibility of the findings. The first author (MW) conducted the main analysis independently and then the preliminary subcategories and main categories were defined and discussed continuously with the second author (CT). If there were disagreements during the analysis, data were revisited to reach consensus. Several quotes were chosen to illustrate and amplify the findings.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board in Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 2019-00438).

Results

The result is presented in four categories based on the model of Patient Evaluation Process and refined to reflect the central meaning of the interviews: expectations before treatment, needs and fulfilment of needs during the care process, results of treatment and rehabilitation, and being prepared with knowledge for the future ().

Table 3. Summary of the categories, subcategories and content based on the model of Patient Evaluation Process.

Expectations before treatment

Expectations of the upcoming treatment were closely connected to the participants’ previous experiences, thoughts and feelings and their perception of health and disease.

Expectations based on previous experiences

Based on previous experiences, there were expectations of having improved hand function, but also an awareness of the risk of recurrence and that the disease cannot be cured. Some participants expected a fully extended and functional finger after treatment with a better grip function that would improve performance of activities in daily life. Others were looking forward to resuming meaningful activities, like golf and yoga, which they had enjoyed before and had been unable to perform due to DD.

Ím doing some handicraft in my garage in my spare time. I have a wood craft/sawing machine, and when I was using this, the finger was placed on the side, and that was kind of scary, it didn’t work so well anymore… I sought treatment so I could use this machine again and be able to grip properly (patient 8)

Participants’ own, relatives’ or friends’ experiences influenced the expectations of treatment. Those who had relatives with experience of the treatment as effective and easy had a more relaxed approach towards their upcoming treatment. In contrast, there were participants who described expecting complications such as skin ruptures after treatment for DD which worried them and made them wonder what it would be like for them.

It was going to crack…and I have a few acquaintances that felt bad about this. They had to have a plaster afterwards [because of skin ruptures] and all that. I might have had thoughts about that to… (patient 10)

Expectations related to thoughts and feelings

Positive or negative expectations of treatment were also related to thoughts and feelings about the disease, treatment, and their future hand function. Some said that it was exciting to be part of a treatment process, and this was based on gratitude for an existing treatment. Others expressed uncertainty and anxiety about their future hand function.

Well…(sigh) I thought it will probably be fine…I hoped… but some people have to do it again [receive treatment] (patient 11)

There were also those who worried about their ability to continue working or to be able to do leisure activities.

I’m not sure [about my future hand function] … will it work…I do maintenance of lawns, gardening and stuff like that (patient 6)

Others spoke of sadness and disappointment about the diagnosis and that their impaired hand function forced them to undergo treatment.

She [the primary care doctor] said ‘the Viking disease’, as it is called, well I don’t remember… I was disappointed maybe. Yes, I was disappointed… (patient 6)

Expectations related to the perception of health and disease

Expectations about what could be achieved from treatment were influenced by the participants’ perceptions of health and disease. There were expectations of age-related ailments such as stiffness and pain in the body and that DD would affect them even more because of increasing age. Some participants said that a coping strategy often used for dealing with this was to try to stay positive towards life, even if health issues or diseases existed. This constituted a way of thinking about what they had to do and made them feel better.

Íve had arthritis in my knees and received a lot of different treatments, and I have done my rehabilitation with exercises…I made it go away. So exercising is very, very good. It hurts sometimes, but you have to start somewhere (patient 3)

Needs and fulfilment of needs during the care process

The overarching needs the participants wanted to be met by treatment was the need for improved hand function. The need for knowledge to be prepared for the upcoming treatment varied among the participants, and the participants emphasised that the healthcare staff had the skills to meet their needs to feel secure.

To get improved hand function

The participants described a range of activity limitations due to DD and spoke of the need for improved hand function as they had severe difficulties with self-care, work, and leisure activities. There could be inability to grip and handle objects, clumsiness, and impaired coordination as well as fear of hurting themselves and limited participation in social leisure activities, exercise, and sports. The participants reached a limit where they had had enough and they were also urged by persons in their surroundings to seek help.

I thought it was hard for me to apply moisturizer in my face, I couldn’t do it, the finger was in the way (laughing), or when I was taking care of my small grandchildren… I felt that it was really a disability. And it was easy to knock things down, for example from a table, I just waved you know like one can do. And it did not feel good to shake hands with people (patient 7)

A need for knowledge

The participants expressed varying needs for knowledge to be prepared for treatment. There were participants who described being actively involved and asking a lot of questions when meeting the healthcare staff. Some of them sought information and read about DD and wanted detailed information to be visualised through pictures or short movies to gain a deeper understanding about the upcoming treatment procedure.

Well, I did that [sought more information about DD] because it’s very easy nowadays to find out more about things…so I had read some things and heard and seen some available information (patient 5)

Others initiated discussions about DD and treatment but were at the same time receptive to decisions and assessment made by healthcare staff. There were also participants who were satisfied with the verbal and written information from the staff and who described no need for further knowledge or to participate actively in the DD care process.

I let them [healthcare staff] make the decisions…they know more about this [DD] than me. (patient 11)

They emphasised that they felt secure, and it was a relief not to be a part of any decision-making regarding their hand. They had full confidence and trust in the healthcare staff to make these decisions.

I have absolutely no experience and they [healthcare staff] have so much experience, so it has to be their thing to decide (patient 4)

Among those participants who were randomised to a treatment method there were expressions of being lucky to be part of a study, and some of them had no need for further knowledge.

I was really happy for this study [the RCT study] … to be included (patient 2)

Others wanted clear explanations and to get all accessible information about the differences between the non-surgical methods.

To get explanations about the different methods [was important to me] … why you choose one method instead of the other (patient 5)

There was also a need for knowledge about how they would feel after treatment, whether there could be complications, and how the rehabilitation was performed. Some emphasised the importance of the individual assessment that they had undergone before treatment. They described this as an opportunity for them to express their individual needs and receive information.

I met the staff [nurse, occupational therapist] at the hand surgery clinic and they were very nice to me during the assessment. They told me everything I needed to know about treatment, rehabilitation and treatment criteria – very detailed… (patient 10)

Healthcare staff professional skills

The participants spoke of the healthcare staff professional skills for meeting the participants’ needs to feel secure. This could be receiving detailed explanations, or that the staff waited or took a break during treatment when something felt uncomfortable. The staff also used different methods to divert the participants’ attention during the treatment, such as talking about other matters or asking questions.

Well, I had two young men that gave me attention (laughing). I don’t know their exact role or function but I think they were there to distract me, and they did a good job… (patient 4)

Some participants emphasised the skills and interplay between the staff and how they seemed to work with enthusiasm and happiness, which made the participants feel secure and less tense about the situation.

Other ways of meeting needs emerging during the treatment could be to squeeze a health professional’s hand when feeling pain during the needle fasciotomy, and this had a calming effect. It could also be the hand surgeon’s assessment of vital functions in the hand such as sensation and tendon function after treatment, which reassured patients that there were no injuries due to treatment.

They tested what I could and could not do with my hand, before I went home. Well, and then I got written information to take home, about what to do and when, and how I could get hold of them [the healthcare staff] (patient 7)

The information given (verbal and written) during the care process was yet another important part of the fulfilment of needs and was deemed easy to understand. One participant described swelling and pain in the hand after the collagenase injection, which made her contact a counselling nurse at the clinic. This contact and guidance reassured her and led to an increased sense of security.

Results after treatment and rehabilitation

The participants’ descriptions of the results were related to the impact on everyday life, how the treatment, the care process and the encounters with the staff were experienced, and their commitment to rehabilitation.

Impact of treatment on daily life

Participants said that treatment and rehabilitation had a positive impact on daily life and activities that had been difficult before, such as baking, washing themselves and putting on gloves. Gardening and the use of different tools were other examples of activities that could be performed again with improved or regained hand function. The participants also expressed joy and happiness at resuming their earlier leisure activities, such as playing golf, typing on a computer, and driving vehicles like a moped or camper.

I think that everything works now…when Ím baking, or washing my face, well…it’s wonderful to notice the difference from before. The most important thing is to be able to use the hand as normal, and to be able to do the things you want to do (patient 1)

Hand function and occupational performance were described as restored or significantly improved due to regained finger joint extension, which led to better grip function. These improvements led to not being aware of the hand all the time.

I have forgotten about the hand! So that must be good, right? (laughing) (patient 2)

The non-surgical treatment process

The participants described the non-surgical treatment overall as positive, effective and simple. Together with the rehabilitation it led to regaining good function in the treated finger. Recovery after treatment, regardless of treatment method, was experienced as quick and there were participants who compared the treatment they had received with other methods.

The treatment Íve had now [non-surgical treatment] and the process I went through… if I had still been working, say full time, I wouldn’t have needed sick leave for a long time. That is a big difference versus if you commit to an operation, a surgical method (patient 6)

Others commented they were positively surprised about the non-surgical treatment.

Well…it [the treatment] was said to be pretty quick and smooth, but I thought it was going to hurt more than it actually did (laughing) - and I did not expect it to be performed so quickly! (patient 5)

However, there were also participants who experienced pain when the anaesthetic was applied and who said that they were uncomfortable when the surgeon applied force to and straightened their finger.

Maybe I wanted more anaesthesia in the hand. So I wouldn’t feel pain, but at the same time…all those injections in the hand! You are very sensitive in the hand, it can really hurt (patient 3)

There were also those who experienced issues with hand function after treatment and rehabilitation. It could be tenderness in the palm or fingers, stiffness, less strength in the treated finger or a wish for better finger joint extension, all of which made them disappointed.

Well, I don’t know…I hoped somehow to have a better result than what Íve had (patient 7)

Others were satisfied with their treatment results or with the care process, although they had remaining issues or signs of DD.

I have a nodule that’s located in the base of the finger, I can see that nodule, but there is no discomfort from it (patient 2)

It’s a bit strange in the palm [after treatment] … the DD cords in the palm are shiny and the tendons are prominent…but I could not ask for a better result, because the way it was before… I am really satisfied now! (patient 3)

Information from and encounters with the staff

The overall view of the care processes the participants had undergone was generally positive and was described as effective and informative with high professionality among the staff. Also, participants who were not fully pleased with the results could still express an overall satisfaction with the care process. Most participants were pleased with the information they had received during the different stages of the care process.

And you get written information to take home after the treatment and rehabilitation visit…information about what to do, when to do it and how to get hold of the staff at the clinic. So that was not a problem for me and I actually contacted them once. (patient 7)

However, participants who had high expectations of treatment could notice details like still having the cords in the palm after treatment, although the finger had regained the extension and they thought that this should be explained in the written but also verbal information from the healthcare. Furthermore, among participants who described taking fewer initiatives during the care process there was a wish for more information about wound healing after skin rupture. Sometimes information was given but not fully understood.

It [the wound] did not heal immediately, it took a very long time. That was surprising to me, because they said I could expect to be using my hand after about a week, so that was troublesome, and it was a long wait… (patient 2)

The participants also mentioned their encounters with the staff, which were influenced by humour and happiness, but also by good teamwork.

I think that I have been treated very well. I have to say that. And…it felt good all the way and it’s been smooth and easy and you get relevant information (patient 4)

It was appreciated that no follow-up visits to the clinic, or only a few, were required after the treatment, and if the participants needed to contact the clinic, they knew how to do so.

Well, the first time I had that [follow-up visits to rehabilitation], but then I was familiar with the exercises and as Íd done them before, I didn’t need to participate in further follow-up visits. I did my exercises at home, and it worked just fine (patient 9)

Commitment to rehabilitation

There were mixed descriptions of following the recommendations about rehabilitation among the participants. Those who described themselves as more active during the care process described higher compliance with rehabilitation. They spoke of great confidence in the use of the extension glove and doing exercises and thought that these interventions could prevent or hinder the risk of recurrence.

The most important work starts after the DD treatment… the rehabilitation and the hand exercises…you should not cheat with it! (patient 6)

The hand exercise programme was stated to be easy to perform and the extension glove was described as comfortable, and this all together increased the compliance with treatment. These participants said that they wanted to do everything they could to get better and that the rehabilitation interventions made a difference for them.

It becomes a habit to do it [the hand exercises]. It’s the first thing you do when you wake up in the morning, and it’s the last thing you do before you go to sleep, and then you do it automatically! And I thought that was really good. And you also had this extension glove. For at least three months [during night-time], I actually wore it even longer… (patient 7)

The participants who expressed confidence in the rehabilitation interventions emphasised that they believed taking great responsibility for rehabilitation could affect the treatment result in a positive way, for example by performing hand exercises consistently, following the given advice from the staff, and trying to have a positive attitude during rehabilitation.

I want to encourage others to perform their hand therapy exercises after the DD treatment, because this is crucial for your rehabilitation, I think. I believe that many think that they can skip the exercises in their rehabilitation generally, I know this from earlier experiences…but no…it is really crucial to comply fully to get a perfect result (patient 3)

In contrast, there were also participants who said that the recommendations regarding the glove had not been followed. The reasons not to use it was that they forgot to put it on before going to bed but also a conscious choice not to use it because it felt too hot or sweaty. These participants stated that they had not experienced any negative effects of not following the instructions, and the finger remained continued to have good finger joint extension. They also described how instead they focused on doing hand exercises regularly and used the hand in ordinary activities during the day.

I do not use the extension glove… Ím doing hand exercises instead, I work as usual and Ìm using the hand as normal… (patient 9)

Being prepared with knowledge for the future

The participants described having good knowledge about DD after treatment and rehabilitation and had an awareness that there could be recurrence. The knowledge about the disease, treatment and rehabilitation gave them a sense of security and control for future needs.

The acquired knowledge about DD among the participants helped them to know when it was time to seek help again, and the criteria to be fulfilled before the next treatment session. They also felt confident about knowing who they could contact when symptoms started to get worse. There were participants hoping that this would be the first and last time they had to be treated. One participant felt confident regarding the future need of treatment based on the knowledge about treatment and rehabilitation, and recovery being fast and uncomplicated.

They said to me that you can’t take away the disease, the disease is still there, so I am prepared for a recurrence…and…if so, there is excellent help! (patient 2)

Another participant described thoughts about future recurrence and not wanting to do anything about it due to age and as it felt like it was too late. There were also thoughts about not wanting to undergo treatment again because of discomfort or pain.

There were participants who emphasised that the same treatment method that they had had before was preferable and if something else were to be considered, they wanted to receive thorough information about why and how the procedure was planned.

Well…if so [there is a need for a different treatment method], I want to know more about how it should be done and why, and the advantages with that…it… if so, there must be quite big advantages (patient 5)

Others said that another treatment method was acceptable if necessary and that they trusted the healthcare staff completely.

If there was a recurrence, I would listen to them [healthcare staff] and their assessment, what they thought was the best treatment for me. I would not hesitate to receive any other treatments than what Íve had before (patient 2)

There was a curiosity about what else there is to offer in DD treatment. Some of the participants had read a lot about DD after their first treatment as they wanted to be prepared and updated in case of recurrence. Several participants said that if there was a need for a second treatment in the future, they would not wait too long to have it done.

If there is a need for a new treatment, I will not hesitate to do that! I’m almost sure that I will have to have a new treatment for my ring finger (patient 10)

Discussion

This study adds new knowledge regarding patients’ perception of non-surgical treatment and rehabilitation for DD. This has not been fully explored previously. The present study shows that non-surgical treatment and rehabilitation for DD was experienced as effective and simple and had a positive impact on everyday life and activities for most participants. The participants described the importance of taking their own responsibility for rehabilitation after treatment. Performing exercises, using the hand in activities, and having a positive attitude were emphasised as positively affecting the outcome. Feedback was mixed regarding the use of the extension glove, with some participants not using it.

The findings in the present study, with mainly a positive view of non-surgical treatment, are in concordance with earlier quantitative studies about satisfaction after non-surgical treatment [Citation16,Citation30,Citation41–44]. However, there were participants in the present study who had hoped for a better result, and reasons for not being satisfied were having remaining issues with reduced finger joint extension, stiffness, or tenderness. There were also participants who mentioned the presence of nodules and cords in the palm after treatment, although this did not seem to cause concern or affect hand function. Determinant factors for patient satisfaction after orthopaedic interventions in the hand have been shown to be, for example, pain, sensation, strength, movement, deformity, and function in occupational performance [Citation45]. For patients with DD undergoing surgical treatment, a positive outcome has been strongly correlated with a positive experience of the delivery of care [Citation27]. Furthermore, fulfilment of expectations and needs has also been shown to contribute to how the result of treatment and the care process is valued [Citation27,Citation34,Citation35,Citation45]. The subjective needs can vary during the care process and how these needs are met can influence the patients’ perception and evaluation of the treatment [Citation26]. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the overall positive view of the non-surgical care process in the present study can be related to both the participants’ experiences of improved hand function and occupational performance, and to the experience of the staffs’ management and fulfilment of their needs.

This study revealed the participants’ positive beliefs in the effectiveness of rehabilitation after DD treatment and how they valued their own effort as important for having a good result. This is in line with previous research regarding patient activation showing that patients who can see themselves as team members and understand the given advice experience better treatment results [Citation46–48]. The participants in the present study also described considerable compliance with the DD rehabilitation, despite few follow-up visits (1-3 visits) to the clinic. Compliance with hand rehabilitation is influenced by several factors related to health beliefs such as the perceived efficacy or rewards of rehabilitation [Citation49]. However, in the present study there were also participants who did not follow all the advice regarding using the extension glove. According to Pomey et al. (2015), the patients are continuously involved in assessments and adaptations of the received healthcare based on the experienced effect of the interventions [Citation50]. As the participants in the present study reported not experiencing any negative effects of not using the extension glove, this may have influenced their decision on whether to follow the given instructions. The participants’ decision not to use the extension glove could also be due to not experiencing any loss of digital extension after the non-surgical treatment. The evidence for using extension gloves or orthoses after non-surgical treatment is scarce. A recent study showed that providing patients with an orthosis after treatment with collagenase injection offered no further benefits to hand therapy alone, especially for patients with metacarpophalangeal-joint contractures [Citation51]. Clinical reasoning regarding the use of orthoses is necessary and a more specific approach regarding the use of orthoses has therefore been suggested, providing orthoses primarily to patients who rapidly loose digital extension after corrective treatment [Citation51,Citation52]. Further research is needed regarding the effectiveness of extension gloves or orthoses after non-surgical treatment for DD.

An important result of the present study is that the participants described increased knowledge and a sense of security after going through the DD care process. This is especially valuable as DD is a chronic disease with some probability of recurrence and further problems in the future [Citation13]. Learning has been described as one aspect of patients’ engagement in their healthcare and is a continuous process where they gather scientific and medical knowledge [Citation50]. In the present study the participants mentioned having received information in several ways and some of them were more actively seeking information. Despite this, it is also important to note that not all the participants wished to use their knowledge, which they could consider as limited, for decision-making regarding the treatment method. This has also been revealed previously and it has been argued that despite a wish for patient participation and a person-centred approach in healthcare, there are those who have neither the ability nor the desire to be actively involved [Citation26,Citation53]. It is therefore important that healthcare staff provide information but that they are also responsive to how the individual patient wishes to be involved regarding decisions about their treatment. For a treatment such as non-surgical treatment of DD, which is characterised by primarily medically determined and service-driven selection processes, there may also be limited scope for patient-held decision-making beyond the decision to accept or decline the treatment that has been offered. Further studies are warranted to fully explore the patient’s role in decision-making in non-surgical treatment and rehabilitation of DD.

A strength of the present study is the use of an established theoretical framework for data collection and analysis, which can increase credibility [Citation39]. The model of Patient Evaluation Process provided a conceptual lens for collecting data, analysis and reporting findings. The inclusion of the category “other” decreased the risk of not being open to data not fitting into the theoretical framework [Citation33]. Although developed in a different context, namely geriatric rehabilitation, the model of Patient Evaluation Process has been useful for describing the experiences of the care process after surgical treatment of DD [Citation35]. The present study confirms how intertwined the components ‘earlier experiences’ and ‘expectations for coming treatment and care’ are, which also has been shown in earlier studies [Citation35]. The findings of the present study contribute to further nuancing the component ‘results’ in the model through the participants’ descriptions of their beliefs in rehabilitation after DD and taking their own responsibility for it. To validate the model further, future research is needed in other areas of healthcare. Also, knowledge regarding the components in the model can be a used for improving health care services which can influence the patients’ experiences of undergoing a care process.

Strengths and limitations

The study sample was small, and we did not include as many participants as intended. However, the sample reflected the population of patients with DD regarding age, sex and disease presentation [Citation54]. The interviews were conducted via telephone, which increased accessibility to eligible participants due to the spreading Covid-19 pandemic during spring 2020. The interviews were relatively short but informative and resulted in a satisfying amount of data after 12 interviews. Timing of the interviews several months after non-surgical treatment may have led to difficulty recalling smaller negative experiences and reporting of mainly positive experiences. It was a conscious choice not to disclose the interviewer’s clinical experience as this could have affected the participants’ answers. Throughout the study, the authors have maintained awareness of their preunderstanding and how this might affect decisions made in the study. This preunderstanding was handled by using bracketing and returning to data to ensure findings were grounded in the text. Despite a quite small sample, the present study reveals new information about patients’ subjective perspective on non-surgical treatment and rehabilitation for DD. The result of this study is limited to its context and further research is needed to fully explore patients’ experiences of non-surgical treatment for DD and the consequences for hand function and daily activities. However, the results of this study can contribute to further development of health care services for patients with DD.

Conclusion

Undergoing a non-surgical treatment and rehabilitation process for DD was regarded as quick and easy and can meet the need for improved hand function and occupational performance. Taking one’s own responsibility for rehabilitation was considered to influence the outcome positively. The theoretical framework optimally supported the exploration of participants’ perspective. It is a useful lens for understanding components affecting experiences of care and for developing health care services.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution in this study, and the hand surgery clinic and rehabilitation colleagues for making this study possible.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Hindocha S. Risk factors, disease associations, and dupuytren diathesis. Hand Clin. 2018;34(3):307–314.

- Gudmundsson K, Arngrı́msson R, Sigfússon N, et al. Epidemiology of dupuytren’s disease: clinical, serological, and social assessment. The reykjavik study. J Clin Epidem. 2000;53(3):291–296.

- Shih B, Bayat A. Scientific understanding and clinical management of dupuytren disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(12):715–726.

- Lanting R, Broekstra D, Werker P, et al. A systematic review and Meta-Analysis on the prevalence of dupuytren disease in the general population of Western countries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(3):593–603.

- Bergenudd H, Lindgärde F, Nilsson B. Prevalence of dupuytren’s contracture and its correlation with degenerative changes in the hand and feet and with criteria of general health. J Hand Surg. 1993;18(2):254–257.

- Engstrand C, Borén L, Liedberg G. Evaluation of activity limitation and digital extension in Dupuytren's contracture three months after fasciectomy and hand therapy interventions. J Hand Ther. 2009;22(1):21–27.

- Pratt A, Byrne G. The lived experience of Dupuytren's disease of the hand . J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(12):1793–1802.

- Engstrand C, Krevers B, Kvist J. Factors affecting functional recovery after surgery and hand therapy in patients with dupuytren's disease. J Hand Ther. 2015;28(3):255–260.

- Turesson C, Kvist J, Krevers B. Experiences of men living with dupuytren’s disease – consequences of the disease for hand function and daily activities. J Hand Ther. 2020;33:386–393.

- Wilburn J, McKenn SP, Perry-Hinsley D, et al. The impact of dupuytren disease on patient activity and quality of life. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(6):1209–1214.

- Badalamente A, Hurst L. Development of collagenase treatment for dupuytren disease. Hand Clin. 2018;34(3):345–349.

- Desai S, Hentz V. The treatment of dupuytren disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(5):936–942.

- Haase S, Chung K. Bringing it all Together: A Practical Approach to the Treatment of Dupuytren Disease. Hand Clin. 2018;34(3):427–436.

- Werker P, Pess G, van Rijssen A, et al. Correction of contracture and recurrence rates of dupuytren contracture following invasive treatment: the importance of clear definitions. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(10):2095–2105.

- Sanjuan - Cerveró V. Efficacy of collagenase Clostridium Histolyticum for dupuytren disease: a systematic review. Revista Iberoamericana de Cirugía de La Mano. 2017;45(2):70–88.

- Buckwalter V, Kitchin S, Goldfarb C, et al. Needle aponeurotomy versus collagenase injections for dupuytren disease: a review of the literature and survey of Patient-Reported satisfaction, recurrence, and complications after needle aponeurotomy. J Hand Surg Global Online. 2019;1(2):91–95.

- Sweet S, Blackmore S. Surgical and therapy update on the management of Dupuytren's disease. J Hand Ther. 2014;27(2):77–84.

- Turesson C. The role of hand therapy in dupuytren disease. Hand Clin. 2018;34(3):395–401.

- Ball C, Pratt A, Nanchahal J. Optimal functional outcome measures for assessing treatment for Dupuytren's disease: a systematic review and recommendations for future practice. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14(1):131.

- Becker G, Davis T. The outcome of surgical treatments for primary Dupuytren's disease-a systematic review. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2010;35(8):623–626.

- Chen N, Srinivasan R, Shauver M, et al. A systematic review of outcomes of fasciotomy, aponeurotomy, and collagenase treatments for Dupuytren's contracture. Hand (N Y)). 2011;6(3):250–255.

- Rodrigues J, Becker G, Ball C, Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group, et al. Surgery for dupuytren’s contracture of the fingers. The. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;2015(12):CD010143–CD010143.

- Rodrigues J, Zhang W, Scammell B, et al. Recovery, responsiveness and interpretability of patient-reported outcome measures after surgery for Dupuytren's disease. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2017;42(3):301–309.

- Thoma A, Kaur M, Ignacy T, et al. Psychometric properties of Health-Related quality of life instruments in patients undergoing palmar fasciectomy for dupuytren's disease: a prospective study. Hand (N Y)). 2014;9(2):166–174.

- Karpinski M, Moltaji S, Baxter C, et al. A systematic review identifying outcomes and outcome measures in Dupuytren's disease research. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2020;45(5):513–520.

- Turesson C, Kvist J, Krevers B. Patients' needs during a surgical intervention process for Dupuytren's disease . Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(6):666–673.

- Poelstra R, Selles R, Slijper H, Hand-Wrist Study Group, et al. Better patients' treatment experiences are associated with better postoperative results in Dupuytren's disease. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2018;43(8):848–854.

- Takata W, Wade E, Roll S. Hand therapy interventions, outcomes, and diagnoses evaluated over the last 10 years: a mapping review linking research to practice. J Hand Ther. 2019;32(1):1–9.

- Strömberg J, Ibsen-Sörensen A, Fridén J. Comparison of treatment outcome after collagenase and needle fasciotomy for Dupuytren Contracture: a randomized, single-blinded, clinical trial with a 1-year follow-up. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(9):873–880.

- Elzinga K, Morhart M. Needle aponeurotomy for dupuytren disease. Hand Clin. 2018;34(3):331–344.

- Krefter C, Marks M, Hensler S, et al. Complications after treating Dupuytren's disease. A systematic literature review. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2017;36(5):322–329.

- Aglen T, Matre K, Lind C, et al. Hand therapy or not following collagenase treatment for Dupuytren's contracture? Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):314–387.

- Krippendorf K. Content analysis. An introduction to its methodology. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage;2013.

- Krevers N, Närvänen A-L, Oberg B. Patient evaluation of the care and rehabilitation process in geriatric hospital care. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(9):482–491.

- Engstrand C, Kvist J, Krevers B. Patients' perspective on surgical intervention for dupuytren's disease - experiences, expectations and appraisal of results. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(26):2538–2549.

- Tufford L, Newman P. Bracketing in qualitative research. Qualitative Social Work. 2012;11(1):80–96.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2002.

- Hermanns H. Interviewing as an activity. In: Flick U, Kardorff E, Steinke I, eds. A companion to qualitative research. London: SAGE; 2004. 209–213.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. In: Williams D, Editor new directions for program evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass: 1986. 73–84.

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120–124.

- Bradley J, Warwick D. Patient satisfaction with collagenase. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(6):689–697.

- Hentz V. Collagenase injections for treatment of dupuytren disease. Hand Clin. 2014;30(1):25–32.

- Warwick D, Arner M, Pajardi G, POINT X Investigators, et al. Collagenase clostridium histolyticum in patients with dupuytren's contracture: results from POINT X, an open-label study of clinical and patient-reported outcomes. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015;40(2):124–132.

- Witthaut J, Jones G, Skrepnik N, et al. Efficacy and safety of collagenase clostridium histolyticum injection for dupuytren contracture: short-term results from 2 open-label studies. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(1):2–11.

- Marks M, Herren D, Vliet Vlieland T, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction after orthopedic interventions to the hand: a review of the literature. J Hand Ther. 2011;24(4):303–312.

- Smith-Forbes EV, Howell DM, Willoughby J, et al. Adherence of individuals in upper extremity rehabilitation: a qualitative study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(8):1262–1268.e1.

- Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences;fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood)). 2013;32(2):207–214.

- Gruber JS, Hageman M, Neuhaus V, et al. Patient activation and disability in upper extremity illness. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(7):1378–1383.

- Groth GN, Wulf MB. Compliance with hand rehabilitation. Health beliefs and strategies. J Hand Therapy. 1995;8(1):18–22.

- Pomey M, Ghadiri D, Karazivan P, et al. Patients as partners: a qualitative study of patients' engagement in their health care. PloS One. 2015;10(4):e0122499.

- Bowers NL, Merrell GA, Foster T, et al. Does use of a night extension orthosis improve outcomes in patients with dupuytren contracture treated with injectable collagenase? Journal of Hans Surgery Global Online. 2021;3(5):272–277.

- Karam M, Kahlar N, Abul A, et al. Comparison of hand therapy with or without splinting postfasciectomy for dupuytren’s contracture: systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Hand Microsurg. 2021. DOI:10.1055/s-0041-1725221.

- Andersson V, Otterstrom-Rydberg E, Karlsson A. The importance of written and verbal information on pain treatment for patients undergoing surgical interventions. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(5):634–641.

- Dahlin LB, Bainbridge C, Leclercq C, et al. Dupuytren’s disease presentation, referral pathways and resource utilisation in Europe: regional analysis of a surgeon survey and patient chart review. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(3):261–270.