Abstract

Purpose We studied the effectiveness of a new cardiac rehabilitation (CR) program developed for patients with obesity compared with standard CR on HRQOL and psychosocial well-being.

Materials and methods OPTICARE XL was a multicentre RCT in patients with cardiac disease and obesity (Netherlands Trial Register: NL5589). Patients were randomized to OPTICARE XL CR (n = 102) or standard CR (n = 99). The one-year OPTICARE XL CR group program included endurance and resistance exercises, behavioural coaching, and after-care. Standard CR consisted of a 6- to 12-week endurance exercise group program, and cardiovascular lifestyle education. Primary endpoint was HRQOL (MacNew) at six months post CR. Second, we assessed anxiety and depression (both HADS), fatigue (FSS), and participation in society (USER-P).

Results In both groups, improvements in HRQOL were observed six months post CR. Mean HRQOL improved from 4.92 to 5.40 in standard CR [mean change (95% CI): 0.48 (0.28, 0.67)] and from 4.96 to 5.45 in OPTICARE XL CR (mean change (95% CI): 0.49 (0.29, 0.70), without between-group differences. Psychosocial well-being improvements within both groups were obtained at six months post CR, regardless of allocated program.

Conclusions OPTICARE XL CR did not have added value in improving HRQOL and psychosocial well-being in patients with obesity.

More than a third of cardiac patients suffers from obesity, and standard cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs are suboptimal in this increasing patient population.

The OPTICARE XL CR program is a state-of-the art, one-year CR program designed for patients with obesity including aerobic and strength exercises, behavioural coaching towards a healthy diet and an active lifestyle, and after-care.

Improvements in HRQOL and psychosocial well-being were comparable between patients with obesity allocated to standard CR and OPTICARE XL CR.

Therefore, there was no additional benefit of OPTICARE XL CR.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Obesity is an increasing public health problem worldwide [Citation1]. The most recent report of the World Health Organisation showed that 13% of the general population is affected by obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2 [Citation2]. Obesity is associated with a higher blood pressure, dyslipidaemia and elevated risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and thus with a higher risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [Citation3]. Results of the most recent EUROASPIRE registry showed that no less than 38% of patients with CVD is obese [Citation4]. Obesity is also associated with an increased risk for the development of atrial fibrillation (AF), known as the most common sustained arrhythmia in adults [Citation5].

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is strongly recommended for secondary prevention in a wide spectrum of patients with cardiac diseases [Citation3,Citation6]. Alongside exercise training, which mainly consists of weight-bearing endurance exercises, education on cardiovascular risk factors and lifestyle is also offered. Improving health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is an important goal of CR, as well as restoring psychosocial well-being, such as reducing feelings of anxiety and depression, fatigue, and experienced restrictions in participation in society [Citation3,Citation6].

CR has shown to be effective in improving HRQOL [Citation7], but results among patients with obesity are contradictory. Although we showed in a previous study that patients with obesity start CR with equivalent HRQOL levels as compared with patients with normal weight, and improvements during CR are similar between BMI classes [Citation8], other studies showed lower HRQOL levels at the start of CR and smaller improvements during CR in patients with obesity [Citation9,Citation10]. Furthermore, Terada et al. showed that patients with obesity experience anxiety and depression more often than those with normal weight and that improvements during CR are smaller [Citation10]. Fatigue is known to be strongly related to these symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with CVD [Citation11]. Lastly, in a study in non-cardiac patients, it has been shown that obesity negatively influences return to work after treatment [Citation12]. Similar results might be expected in patients with obesity who enter CR with respect to return to work, as well as to other aspects of participation in society such as leisure and household activities.

Behavioural interventions and an improved physical fitness have previously shown to positively impact HRQOL and psychosocial outcomes [Citation13,Citation14]. Therefore, we developed the OPTICARE XL CR program, which is a one-year, state-of-the art, peer group program designed for patients with obesity. We conducted a multicentre randomized controlled trial to study the effectiveness of the OPTICARE XL CR on HRQOL in patients with obesity compared with standard CR six months after completion of either program. Second, we assessed the effects on anxiety, depression, fatigue, and participation in society, and we assessed short-term effects for all outcomes, i.e., three months after the start of CR.

Materials and methods

Study design

The OPTImal CArdiac REhabilitation XL (OPTICARE XL) study is a parallel multicentre open label randomized controlled trial among patients with obesity entering CR. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus University Medical Centre Rotterdam, The Netherlands (MEC-2016-622). All patients provided written informed consent before study entry.

Population

Patients were recruited from the three largest CR centres in the western and southern regions of the Netherlands: Capri Cardiac Rehabilitation in Rotterdam, Capri Cardiac Rehabilitation in The Hague and Máxima Medical Centre in Eindhoven/Veldhoven. Patients aged ≥18 years with obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) referred to CR with documented coronary artery disease (CAD) or nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) were invited to participate. Exclusion criteria were heart failure, left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, prior implantation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, psychological or cognitive impairments, or severe comorbidities which could hamper participation in CR. Patients had to be able to communicate in Dutch.

OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 allocation ratio to OPTICARE XL CR or standard CR (Supplemental Figure 1). An independent researcher used a computer-generated block randomization scheme, with a block size of four, to allocate patients and subsequently prepared consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed randomisation envelopes. Enrolment of participants was performed by study coordinators in each centre who were unaware of the block size, and randomisation was performed directly after baseline measurements.

The main characteristics of OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR are presented in . The OPTICARE XL CR group received a one-year program specifically designed for patients with obesity, which was developed by health professionals, patients and scientists of Capri Cardiac Rehabilitation and Erasmus University Medical Centre. The main aim of OPTICARE XL CR was guiding patients with obesity towards a healthier lifestyle by combining several behavioural change techniques such as self-monitoring, goal setting, planning, receiving feedback, identifying barriers, and developing plans for relapse prevention [Citation15–17]. By applying these techniques, awareness about a healthy lifestyle is created, which supports behavioural change [Citation18,Citation19]. On top of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for CR as applied in standard CR, the OPTICARE XL CR program was based on the Dutch dietary guidelines on food intake and food choices, and on the Dutch Physical Activity Guidelines of the Health Council of the Netherlands [Citation6,Citation20–22]. The program consisted of two parts:

Table 1. Characteristics of OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR.

In part I of the OPTICARE XL CR program, 60-90 min supervised exercise sessions were provided twice a week for 12 weeks. These sessions comprised a combination of endurance training with mainly non-weight-bearing exercises (e.g., on cycle ergometer, rowing ergometer), and resistance training (using fitness equipment), aimed at expansion to activities with a higher caloric energy expenditure. This type of training is preferred in patients with obesity for prevention of musculoskeletal complaints and facilitation of weight loss [Citation23–25]. Exercise sessions were provided in small groups of six to eight patients, all with obesity. In addition to usual information sessions and facultative modules as offered in the standard CR program, patients received two group coaching modules in which peer support was encouraged. The first was the Healthy Weight module and was provided once a week by a dietician. Each session started with measuring body weight and waist circumference to enhance self-monitoring, after which weekly a different topic was discussed (such as intake of specific nutrients, reading and understanding food labels, or different types of eating behaviour). The second module was the Active Lifestyle module, which was provided by a physiotherapist once every three weeks. During this module not only regular physical activity was stimulated, but also the prevention of sedentary behaviour. Self-monitoring and goal setting were enhanced by using an activity tracker (Garmin VivoSmart HR XL). Both modules were supported by social workers and psychologists, and all therapists were trained in motivational interviewing [Citation26].

OPTICARE XL CR part II was a nine-month after-care program. This after-care program consisted of six booster sessions, which comprised topics of the modules Healthy Weight and Active Lifestyle, included guidance on psychosocial problems and provided time for questions or topics brought in by patients. Peer support was further created by a group chat on participants’ mobile phones in which participation was voluntary.

Standard CR was in line with the ESC guidelines [Citation3,Citation6] and consisted of 60–90 min supervised exercise sessions (mainly endurance weight-bearing activities such as walking, jogging, sports) provided twice a week in groups including patients with and without obesity. Exercise training was complemented with group information sessions on lifestyle and risk factors for cardiac diseases and facultative counselling sessions on a healthy diet, stress management, physical activity or smoking cessation. The duration of standard CR was 6–12 weeks and patients received no after-care. Exact duration of the CR program depended on progression and goals of the patient as determined by a multidisciplinary team, consisting of physiotherapists, nurses, psychologist or social workers, dieticians, cardiologists and sports physicians.

Assessment of outcomes

HRQOL was measured by the Dutch version of the MacNew Heart Disease HRQOL Instrument, which is a validated 27-item disease-specific questionnaire [Citation27,Citation28]. The score on HRQOL ranged from 1 (poor HRQOL) to 7 (high HRQOL) on each of the four HRQOL domains (global, physical function, emotions, and social participation).

Anxiety and depression were screened by the widely used Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [Citation29]. A 4-point Likert scale was used to measure anxiety (HADS-A score) and depression (HADS-D score) with seven questions per domain. A score of 0-7 is defined as “no anxiety/depressive disorder”, a score of 8-10 as “possible anxiety/depressive disorder”, and a score of 11-21 as “likely anxiety/depressive disorder”.

The Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) was used to measure fatigue and has been found reliable and valid in patients with various diseases [Citation30]. The FSS consists of nine questions on a 7-point scale from “totally disagree” to “totally agree”. A FSS score of ≥4 is defined as being fatigued [Citation30].

Participation in society was assessed with the Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation (USER-P), which focusses on different aspects of daily life, such as paid or unpaid work, housekeeping, outdoor activities, relationship with partner, and paying visits to family and friends [Citation31–33]. Two different dimensions of participation in society were addressed: satisfaction and perceived restrictions. A score from 0 to 100 was calculated for each dimension, in which higher scores indicate better participation.

During baseline assessment, characteristics on sex, age, BMI, reason for referral to CR and treatment, marital status, educational level, work status and presence of cardiovascular risk factors were collected for descriptive reasons. Marital status (partnered or unpartnered), educational level (low, intermediate or high) and work status (employed or unemployed) were assessed by a questionnaire developed for the purpose of the study. Cardiovascular risk factors (presence of family history of CVD, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and smoking before CR) were collected from medical records.

Study end points

The OPTICARE XL CR program aims at long-lasting behavioural changes; therefore, the change from baseline (T0) to six months post CR (T18M in the OPTICARE XL CR group and T9M in the standard CR group) in HRQOL was the primary study end point (Supplemental Figure 1). Changes in anxiety and depression, fatigue, and participation in society were secondary outcomes and also investigated at baseline and six months post CR. We also investigated short-term between-group differences in the outcome measures, i.e., change from baseline to three months after the start of CR (change T0-T3M).

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation was based on an estimated effect on HRQOL at the primary end point six months post CR. We assumed an improvement of 10% after OPTICARE XL CR and no improvement after standard CR, and used a baseline HRQOL score on the global domain of 5.37 [Citation34]. A total of 56 patients per group was required to test the null hypothesis that the population means were equal (power = 0.80 and alpha = 0.05). To account for a drop-out of 25%, 14 extra patients per group were included. Total sample size was therefore estimated at 140 patients. We increased the number of patients from 140 to 200 to be able to evaluate the effects on secondary outcomes with sufficient power as well as to explore factors associated with effects of the intervention (both not this paper).

Statistical analyses

Baseline data were depicted for the OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR group separately. We checked normality of continuous variables by means of a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally distributed data were depicted as means ± SD, not normally distributed data as median and IQR. Categorical data were displayed as numbers and percentages.

Changes in study endpoints in relation to the randomly allocated CR strategies were studied by linear mixed-effect models. Patients were included if at least one outcome measurement was completed. Treatment allocation (standard CR or OPTICARE XL CR) was modelled as a fixed effect, and “time” (baseline or follow-up measurement) as random effect. Treatment × time interaction was added to study differences in changes in study endpoints between the randomly allocated treatments. All models were corrected for age and sex (fixed effects).

To gain insight into the effects in patients who actually completed the program, we also performed a per-protocol analysis. Patients who attended at least 75% of the exercise training sessions (both OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR) and at least 75% of the modules Healthy Weight and Active Lifestyle (OPTICARE XL CR) were included in the per-protocol analysis.

All analyses were performed in R Statistical software (Version 1.3.1093, RStudio Team (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, URL (https://www.rstudio.com/). For all tests, a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient inclusion and baseline characteristics

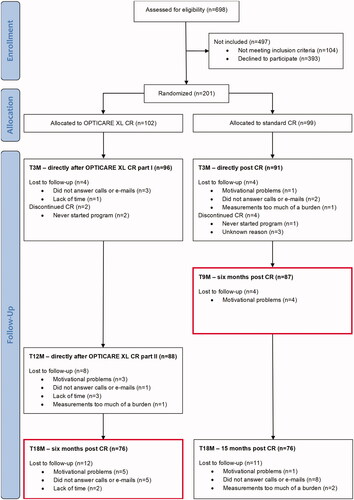

Between February 2017 and January 2019, 698 patients with obesity were screened for eligibility (). Main reasons for declining participation were travel distance to the CR centre, lack of motivation to participate in scientific research and lack of time. A total of 201 patients were included and successfully randomized to OPTICARE XL CR (n = 102) or standard CR (n = 99). The proportion of males was 66.7% in the OPTICARE XL CR group and 78.8% in the standard CR group and mean age was 59 years in both groups (). Two-third of the patients was referred to CR after documented CAD, of which the majority had a percutaneous intervention. Mean time (95% confidence interval; 95% CI) between hospital discharge and admission to CR was 59.5 days (28.5, 90.5) in patients referred to CR after CAD. Most patients had a partner and were employed at the start of CR. The last follow-up measurements were performed in July 2020.

Figure 1. Flow diagram. Primary end point in red.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics study population (n = 201).

Six months post CR, a total of 26 patients were lost to follow-up in the OPTICARE XL CR group, including two patients who never started CR. In the standard CR group, a total of 12 patients were lost to follow-up, including four patients who quit CR prematurely. Reasons for loss to follow-up, in both groups, were motivational problems (such as not willing to participate in measurements anymore), lack of time or not answering calls or e-mails for measurement invitations. In the OPTICARE XL CR group, patients who were lost to follow-up were on average significantly younger than patients who were not lost to follow-up (55 vs. 61 years, p = 0.012), while this was not observed within the standard CR group (59 vs. 59 years, p = 0.936).

Long-term changes in HRQOL and psychosocial well-being

From baseline to six months post CR, HRQOL increased significantly on all four domains in both randomly allocated groups (). For instance, mean HRQOL on the global domain increased from 4.96 to 5.45 in the OPTICARE XL CR group (mean change (95% CI): 0.49 (0.29, 0.70)) and from 4.92 to 5.40 in the standard CR group (mean change (95% CI): 0.48 (0.28, 0.67)). However, these improvements were not significantly different between the study groups.

Table 3. Mean health-related quality of life at the start of CR, at six months post CR, and mean change for OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR group separately, as well as difference in change between groups.

Six months post CR, anxiety, depression, fatigue and participation in society scores also improved within groups, without significant between-group differences (). The prevalence of possible or likely anxiety (HADS_A score ≥8) decreased from 22.5% to 8.6% in the OPTICARE XL CR group and from 33.0% to 16.2% in the standard CR group. The prevalence of possible or likely depression (HADS_D score ≥8) decreased from 18.0% to 13.0% in the OPTICARE XL CR group and from 26.2% to 7.7% in the standard CR group. The prevalence of fatigue (FSS score ≥4) decreased from 51.2% to 41.0% in the OPTICARE XL CR group and from 51.2% to 28.3% in the standard CR group.

Table 4. Mean scores on anxiety, depression, fatigue and participation in society at the start of CR, at six months post CR, and mean change for OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR group separately, as well as difference in change between groups.

Short-term changes in HRQOL and psychosocial well-being

On the short-term, significant improvements in HRQOL were observed within both study groups and these improvements were not significantly different between study groups (). Scores on anxiety, depression, and fatigue also improved within both study groups, without between-group differences (). The OPTICARE XL CR group showed a significantly larger improvement in perceived restrictions with participation in society score from 83.4 to 90.5 (mean change (95% CI): 7.1 (4.7, 9.5) compared with an improvement from 83.4 to 86.6 in the standard CR group (mean change (95% CI): 3.2 (0.6, 5.7)). A post hoc exploration showed the largest improvements in the OPTICARE XL CR group in the aspects of physical exercise, outdoor activities and relationship with partner (data not shown).

Table 5. Mean health-related quality of life at the start of CR, at three months after start of CR, and mean change for OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR group separately, as well as difference in change between groups.

Table 6. Mean scores on anxiety, depression, fatigue and participation in society at the start of CR, at three months after start of CR, and mean change for OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR group separately, as well as difference in change between groups.

Per-protocol analysis

In the OPTICARE XL CR group, 65 of 102 patients (63.7%) followed at least 75% of the exercise sessions and additional OPTICARE XL CR modules, and in the standard CR group 69 of 99 patients (69.7%) participated in at least 75% of the exercise sessions (p = 0.369). The per-protocol analysis (Supplemental Tables I-IV) showed no significant differences in the changes in HRQOL and psychosocial well-being between OPTICARE XL CR and standard CR six months post CR.

Three months after the start of CR, patients allocated to OPTICARE XL CR showed, on average, a significantly larger improvement in perceived restrictions with participation in society score from 82.9 to 90.9 (mean change (95% CI): 8.0 (5.1, 10.9)) compared with an improvement from 87.0 to 88.8 in the standard CR group (mean change (95% CI): 1.8 (−1.1, 4.8)). In addition, the OPTICARE XL CR group showed a significantly smaller improvement in anxiety score of −0.6 (95% CI: −1.2, 0.0) compared with −1.5 (95% CI: −2.2, −0.9) in the standard CR group.

Discussion

This paper described the results of the OPTICARE XL trial, comparing a dedicated CR program for patients with obesity with standard CR. Importantly, both groups showed improvements in HRQOL and psychosocial well-being. However, we observed no additional benefit of the OPTICARE XL CR program.

Improving HRQOL and psychosocial well-being are important goals of CR [Citation3,Citation6]. Studies in which HRQOL scores were compared between patients with obesity and patients with normal weight found lower baseline scores in patients with obesity, although generic HRQOL questionnaires were used, thereby making comparability with the scores found in the present study difficult [Citation9,Citation10]. HRQOL scores observed in our study were comparable to those found by Maes et al. in an observational study in 6749 CR patients with unknown BMI [Citation35] as well as in our previous study on the differences in HRQOL improvements during and after CR between BMI classes [Citation8], and point at a rather good HRQOL at baseline. An explanation for the absence of a significantly larger improvement in HRQOL in the OPTICARE XL CR group may be related to these apparently good baseline values and thereby the smaller possibility for improvement in HRQOL score. Nevertheless, regardless the fairly high baseline levels, we found improvements in HRQOL in both groups. Nonetheless, this suggests that additional care with regard to HRQOL is not needed in the majority of this patient population.

As expected, a considerable proportion of patients showed symptoms of anxiety and depression, which is in line with previous studies indicating a higher prevalence of symptoms of anxiety/depression in the obese versus non-obese population (in the general and cardiac population) [Citation36–38]. The prevalence of anxiety and depression reported in patients with CVD in the Netherlands is 18.0% and 16.4%, respectively [Citation39]. In our study, 8.6% of patients allocated to OPTICARE XL CR experienced feelings of anxiety and 13.0% feelings of depression six months post CR. In the standard CR group, 16.2% of the patients experienced feelings of anxiety and 7.7% feelings of depression six months post CR. Thus, both groups showed large improvements in anxiety and depression and since the prevalence was lower than in the overall CVD population in the NL [Citation39], we can conclude that anxiety and depression successfully decreased after CR in patients with obesity, regardless of being allocated to OPTICARE XL CR or standard CR. Significantly smaller improvement in anxiety score in the OPTICARE XL CR group was observed in the per-protocol analysis. Nevertheless, these differences no longer existed at the longer term and might be due to chance.

In our study, the mean score on fatigue decreased significantly, regardless of the allocated intervention. Nevertheless, we observed that a total of 41.0% in the OPTICARE XL CR group and 28.3% in the standard CR group still experienced fatigue six months post CR. In both groups, this prevalence of fatigue was still substantially higher than in the general population, in which 18.0% experiences fatigue [Citation30], indicating that extra treatment of fatigue during CR is likely to be beneficial. Future studies should focus on assessing determinants of fatigue and on developing interventions to decrease fatigue in CR populations. This is of special concern in patients with obesity, since the prevalence of fatigue in our study was higher than in a comparable CR study population including patients from all BMI classes, in which 13.2% of patients who were attained standard CR experienced fatigue after CR [Citation40].

Lastly, we observed that patients with obesity benefit equally from standard CR as from OPTICARE XL CR in perceiving less restrictions and more satisfaction with participation in society six months post CR. Nevertheless, a significantly larger improvement in perceived restrictions with participation in society was found in the OPTICARE XL CR group than in the standard CR group three months after the start of CR. Interestingly, a post hoc exploration showed the largest improvements in aspects of participation in society which are also the focus of the group coaching modules of the OPTICARE XL CR program (physical exercise, outdoor activities and relationship with partner). However, since the significantly larger improvement in perceived restrictions was only found in one of the nine outcomes assessed in the present study, this finding may also be due to chance. Furthermore, as described above, between-group differences no longer existed six months post CR and follow-up scores in the present study were comparable to the scores found in the validation study of the USER-P questionnaire in patients with cardiac diseases four months after completion of CR and were relatively high [Citation31]. Altogether, this indicates that patients with cardiac disease and obesity do not need extra guidance in improving their participation in society during CR.

Strengths and limitations

The effectiveness of OPTICARE XL CR was studied in a large multicentre randomized controlled trial design, including a long-term follow-up period up to six months post CR. A major strength of this dedicated CR program was that it was developed in close collaboration between health professionals, patients and scientists. An additional strength was the use of validated disease-specific questionnaires, and frequently used questionnaires in rehabilitation medicine. Results of the OPTICARE XL study on physical-oriented outcomes such as body weight and physical activity will be described in a separate paper.

Two limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, patients who were eligible to participate were asked to adhere to an extensive one-year program, specific for patients with obesity. Not all patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria for our study recognize obesity as a risk factor for cardiac disease and see the need to change their behaviour with respect to this risk factor, which could explain the high proportion of patients who declined to participate (393 out of 698). As a result, we might have included highly motivated patients, which could also explain the good results in the standard CR group. Future studies should focus on finding ways to motivate a more diverse group of patients with obesity to participate in dedicated lifestyle programs. Secondly, patients who were lost to follow-up at six months post CR in the OPTICARE XL CR group were significantly younger as compared to patients who were not lost to follow-up. Since patients were included in the analysis if they had at least one measurement completed, this is not expected to have influenced the results. Nonetheless, it should be kept in mind when offering an extensive program to patients in the future.

We conclude that patients with obesity improved their HRQOL, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and participation in society, regardless of being allocated to the one-year OPTICARE XL CR program or standard CR. This suggests that the specific care as provided in OPTICARE XL CR is not needed to improve HRQOL and psychosocial well-being in patients with obesity.

TIDS-11-2021-122-R1-supplementary.docx

Download MS Word (240.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating patients of all centres. We also thank the personnel of Capri Cardiac Rehabilitation and Máxima Medical Centre who collected data and treated patients according to protocol. Lastly, we want to thank Verena van Marrewijk and medical students from Erasmus MC for assisting in data collection.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article are available in DANS, at https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:204552

Additional information

Funding

References

- GBD Obesity Collaborators. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. New Eng J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27.

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight fact sheet no 311 [cited 2020 May]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

- Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S; ESC Scientific Document Group, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the sixth joint task force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR)). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315–2381.

- Kotseva K, De Backer G, De Bacquer D; on behalf of the EUROASPIRE Investigators*, et al. Lifestyle and impact on cardiovascular risk factor control in coronary patients across 27 countries: results from the European Society of Cardiology ESC-EORP EUROASPIRE V registry. Eur J Prev Cardiolog. 2019;26(8):824–835.

- Morin DP, Bernard ML, Madias C, editors, et al. The state of the art: atrial fibrillation epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2016;91(12):1778–1810.

- Revalidatiecommissie NVVC/NHS en projectgroep PAAHR. Multidisciplinary guidelines cardiac rehabilitation (Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn Hartrevalidatie 2011) 2011.

- Francis T, Kabboul N, Rac V, et al. The effect of cardiac rehabilitation on health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35(3):352–364.

- Den Uijl I, Hoeve NT, Sunamura M, et al. Health-related quality of life and cardiac rehabilitation: Does body mass index matter? J Rehabil Med. 2020;52(7):0–6.

- Gunstad J, Luyster F, Hughes J, et al. The effects of obesity on functional work capacity and quality of life in phase II cardiac rehabilitation. Prev Cardiol. 2007;10(2):64–67.

- Terada T, Chirico D, Tulloch HE, et al. Psychosocial and cardiometabolic health of patients with differing body mass index completing cardiac rehabilitation. Canad J Cardiol. 2019;35(6):712–720.

- Bunevicius A, Stankus A, Brozaitiene J, et al. Relationship of fatigue and exercise capacity with emotional and physical state in patients with coronary artery disease admitted for rehabilitation program. Am Heart J. 2011;162(2):310–316.

- Di Meglio A, Menvielle G, Dumas A, et al. Body weight and return to work among survivors of early-stage breast cancer. ESMO Open. 2020;5(6):e000908.

- Nooijen CF, Stam HJ, Sluis T, et al. A behavioral intervention promoting physical activity in people with subacute spinal cord injury: secondary effects on health, social participation and quality of life. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(6):772–780.

- Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Anton PM, et al. Effects of a multicomponent physical activity behavior change intervention on fatigue, anxiety, and depressive symptomatology in breast cancer survivors: randomized trial. Psychooncology. 2017;26(11):1901–1906.

- Aldcroft SA, Taylor NF, Blackstock FC, et al. Psychoeducational rehabilitation for health behavior change in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of controlled trials. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2011;31(5):273–281.

- Chase J-AD. Systematic review of physical activity intervention studies after cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26(5):351–358.

- Ferrier S, Blanchard CM, Vallis M, et al. Behavioural interventions to increase the physical activity of cardiac patients: a review. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011;18(1):15–32.

- Janssen V, Gucht VD, Dusseldorp E, et al. Lifestyle modification programmes for patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20(4):620–640.

- Lara-Breitinger K, Lynch M, Kopecky S. Nutrition intervention in cardiac rehabilitation: a review of the literature and strategies for the future. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2021;41(6):383–388.

- Health Council of the Netherlands. Guidelines for a healthy diet 2015 (richtlijn goede voeding 2015). The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands (Gezondheidsraad); 2015.

- Health Council of the Netherlands. Advies Beweegrichtlijnen 2017. 2017.

- Weggemans RM, Backx FJ, Borghouts L; Committee Dutch Physical Activity Guidelines 2017, et al. The 2017 Dutch physical activity guidelines. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):58.

- Christle JW, Schlumberger A, Zelger O, et al. Effect of individualized combined exercise versus group-based maintenance exercise in patients with heart disease and reduced exercise capacity: the DOPPELHERZ trial. J Cardiopulmon Rehab Prevent. 2018;38(1):31–37.

- Ho SS, Dhaliwal SS, Hills AP, et al. The effect of 12 weeks of aerobic, resistance or combination exercise training on cardiovascular risk factors in the overweight and obese in a randomized trial. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1–10.

- Schjerve IE, Tyldum GA, Tjønna AE, et al. Both aerobic endurance and strength training programmes improve cardiovascular health in obese adults. Clin Sci. 2008;115(9):283–293.

- Hancock K, Davidson PM, Daly J, et al. An exploration of the usefulness of motivational interviewing in facilitating secondary prevention gains in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulmon Rehab Prevent. 2005;25(4):200–206.

- De Gucht V, Van Elderen T, Van Der Kamp L, et al. Quality of life after myocardial infarction: translation and validation of the MacNew questionnaire for a Dutch population. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(8):1483–1488.

- Höfer S, Lim L, Guyatt G, et al. The MacNew heart disease health-related quality of life instrument: a summary. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2(1):3–8.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

- Valko PO, Bassetti CL, Bloch KE, et al. Validation of the fatigue severity scale in a Swiss cohort. Sleep. 2008;31(11):1601–1607.

- Post MW, van der Zee CH, Hennink J, et al. Validity of the Utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(6):478–485.

- van der Zee CH, Kap A, Mishre RR, et al. Responsiveness of four participation measures to changes during and after outpatient rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(11):1003–1009.

- van der Zee CH, Priesterbach AR, van der Dussen L, et al. Reproducibility of three self-report participation measures: the ICF measure of participation and activities screener, the participation scale, and the Utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(8):752–757.

- Janssen V, De Gucht V, van Exel H, et al. Changes in illness perceptions and quality of life during participation in cardiac rehabilitation. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20(4):582–589.

- Maes S, De Gucht V, Goud R, et al. Is the MacNew quality of life questionnaire a useful diagnostic and evaluation instrument for cardiac rehabilitation? Eur J Prevent Cardiol. 2008;15(5):516–520.

- Amiri S, Behnezhad S. Obesity and anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatry. 2019;33(2):72–89.

- Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220–229.

- Murphy B, Le Grande M, Alvarenga M, et al. Anxiety and depression after a cardiac event: prevalence and predictors. Front Psychol. 2020;10:3010.

- Pogosova N, Kotseva K, De Bacquer D, EUROASPIRE Investigators, et al. Psychosocial risk factors in relation to other cardiovascular risk factors in coronary heart disease: results from the EUROASPIRE IV survey. A registry from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(13):1371–1380.

- Ter Hoeve N, Sunamura M, Stam HJ, et al. A secondary analysis of data from the OPTICARE randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of extended cardiac rehabilitation on functional capacity, fatigue, and participation in society. Clin Rehabil. 2019;33(8):1355–1366.