Abstract

Purpose

To explore patients’ experiences of early active motion flexor tendon rehabilitation in relation to adherence to restrictions and outcome of rehabilitation.

Method

Seventeen patients with a flexor tendon injury in one or several fingers participated in qualitative interviews performed between 74 and 111 days after surgery. Data were analysed using directed content analysis with the Health Belief Model (HBM) as a theoretical framework.

Results

Perceived severity of hand function and susceptibility to loss of hand function affected the participants’ behaviour. A higher perceived threat increased motivation to exercise and be cautious in activities. During rehabilitation, the perceived benefits or efficacy of doing exercise and following restrictions were compared to the cost of doing so, leading to adherence or non-adherence behaviour. Perceived self-efficacy was affected by previous knowledge and varied through the rehabilitation period. External factors and interaction with therapists influenced the perception of the severity of the injury and the cost and benefits of adhering to rehabilitation.

Conclusion

Patient’s perception of the injury, the effectiveness of exercises, context and social support to manage daily life affected adherence to restriction, motivation and commitment to rehabilitation. The HBM as a theoretical framework can be beneficial for understanding factors that influence patients’ adherence.

Information regarding the injury and consequences for the patient should be presented at different time points and in different ways, tailored to the patient.

It’ is important to aid patients to perceive the small gradual improvements in hand function to create motivation to adhere to exercise.

Strategies to reduce the cost of adherence in terms of managing everyday life should be addressed by individually based strategies.

Instructions regarding exercise and restrictions should be less complex and consider the patient’s individual needs.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

The incidence of flexor tendon injuries is seven in 100 000/year, most commonly affecting men in their thirties [Citation1]. The balance between gaining a good range of motion and avoiding tendon rupture is a well-known problem during flexor tendon rehabilitation, especially when the injury is in zone one and two. Literature reports tendon ruptures in 5% of patients [Citation2] and decreased range of motion in 9% at follow-up between three months and five years after surgery [Citation3]. This could lead to a loss of essential hand function affecting everyday life. Early active motion is one of the most used methods for flexor tendon rehabilitation. The patients are recommended regular home-based exercises often several times a day, starting the first week after surgery, including passive and active finger flexion at a sufficient level. Following restrictions in hand, use is required, while still managing everyday life. Previous research has shown that patients with higher adherence get better outcomes [Citation4,Citation5] and that poor adherence to restrictions can lead to ruptures after flexor tendon repair [Citation6,Citation7]. However, few studies have investigated the patient’s view regarding flexor tendon rehabilitation. In a general hand therapy population, Kirwan et al. [Citation8] found that the most common reasons for non-compliance with home exercises according to the patients were lack of time, pain or discomfort, forgetfulness, and interference with family or social life. The same reasons were identified by the therapists although they reported non-compliant behaviour with home exercises to occur more often than the patients did. Sandford et al. [Citation9] investigated adherence to wearing a splint for 24 h a day after flexor and extensor tendon repair. They found that 67% of patients remove their protective splint in order to be able to use their hands. Kaskutas et al. [Citation10] examined activity limitations and restrictions in relation to orthotic wear after flexor tendon injury and found that patients struggle to fulfil their life roles. Still, there is a lack of knowledge about the patient’s experience regarding adherence to early active motion flexor tendon rehabilitation regime and the restrictions in using the hand. Adhering to recommendations after flexor tendon repair can have a profound impact on the clinical outcome and can be demanding for the patient. This suggests a need for a better understanding of the patients’ perspective to fully understand the reasons for not adhering to restrictions or exercises.

Adherence to rehabilitation is a complex behaviour phenomenon with potential multifaceted explanations. The Health Belief Model (HBM) by Becker [Citation11] from 1974 is one of the most commonly used behaviour theories [Citation12]. It has been adapted to hand rehabilitation by Groth and Wulf, describing the inter-relationships of factors that could influence adherence [Citation13]. The adapted model states that the patient’s likelihood of being actively engaged in rehabilitation following restrictions and doing exercises is dependent on the patient’s perception of the constructs described in the model as internal factors. These constructs are the severity of the injury, the susceptibility to loss of hand function, the efficacy of rehabilitation, the cost, and benefits of rehabilitation, the self-efficacy to following recommendations, and the patient-practitioner relationship. In addition, external environmental factors can have an impact on the patient.

The adapted HBM has not been tested on patients with flexor tendon injuries but may provide a theoretical construct for exploring patients’ experience of adherence to a demanding hand rehabilitation regime. Exploring aspects related to adherence is crucial to improve rehabilitation service and to avoid tendon adhesions, as well as tendon ruptures, which both may lead to poor hand function and long-term disability. The aim of this study was to explore patients` experience of early active motion flexor tendon rehabilitation in relation to adherence and outcome of rehabilitation.

Method

A study design with qualitative interviews was chosen to explore the participants’ experiences since the nature of the problem is complex [Citation14] and to enable a more full understanding of the patients’ experience of adherence to restrictions and rehabilitation. The HBM modified for hand rehabilitation by Groth and Wulf [Citation13] was used as a theoretical framework and guided data collection and analysis. Data were analysed using directed content analysis [Citation15] originating from a deductive approach where an existing theory can help focus the research question, advance theory and contribute to existing knowledge [Citation16].

Sample

Participants were recruited using a relevance sampling strategy with the intention to get a maximum variety of experiences. We strived for a variation in rehabilitation outcomes (range of motion), age, gender, and type of injury. The inclusion criteria were: patients above 18 years of age, with a flexor tendon injury in one or several fingers, able to speak and understand Swedish, who had undergone rehabilitation according to an early active motion regime. Sampling was initially based on the presence or absence of a postoperative tendon rupture during rehabilitation but, we expanded the inclusion after five interviews to also consider differences in a range of motion outcomes according to the Strickland criteria [Citation17] in patients with no ruptures. This was done to further deepen the exploration of experiences of rehabilitation as differences in a range of motion can influence the patient’s view of the outcome.

Patients were recruited from three-hand surgery departments in Sweden where they were treated for a flexor tendon injury. They were invited to participate in the study by their treating hand therapist during their first three months of rehabilitation. Oral and written information about the study was given and written consent was obtained from all participants. Nineteen patients with repair of one or several finger flexor tendons were recruited for the study. Two participants did not respond and were excluded, leaving 17 for inclusion in the study. Descriptions of the participants' age, gender, type of tendon injury and rehabilitation outcomes are presented in .

Table 1. Background data on all participants regarding, gender, injury type and rehabilitation outcome in a range of motion classified according to Strickland’s criteria in patients with no ruptures, or as tendon rupture in case of rupture during rehabilitation.

Ethics

Ethical consent from the regional ethics committee in Stockholm (Dnr 2018/1466-31) was obtained before the study started. All names of the participants were changed to pseudonyms to protect them from being identified when reporting the study results. The Participants were granted permission to audio-record the interviews.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted at a median of 94 days after surgery (range 74–111 days). This time was chosen because patients are recommended to avoid heavy load on the hand until that point. The collection of data started in June 2018, parallel to the inclusion of the participants and ended in September 2019 when the data collection was deemed sufficient. This was based on the overall perception of the content of the interviews when new information tended to be redundant to data already collected [Citation18]. The participants were asked to find a quiet place where they could take part in the interviews. All interviews were carried out over the telephone by the first author using a semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary material) with open-ended questions inspired by the HBM modified for hand rehabilitation [Citation13], Probing questions were thereafter asked in relation to the aim of the study. All interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim by the first author or a research assistant. The interviews were conducted by telephone because the participants were recruited from different clinical sites and nonverbal expressions were not analysed. The first author who conducted the interviews had not been involved in the rehabilitation of the participants and presented himself as a researcher, instead of a physiotherapist at the start of the interview. This was done to get an unbiased description of the participants’ experiences. The interviews lasted between 30 and 59 min.

Data analysis

A directed content analysis was used [Citation15]. The manifest content of the transcribed interviews was chosen as the unit of analysis. The first author immersed himself in the unit of analysis by reading the transcripts several times. A categorisation matrix was created based on the constructs of the modified HBM and with one main category labelled “Other” allowing for openness to data that did not fit the model. The main categories were defined based on the HBM modified for hand injuries, and rules for coding were established. As the internal factors in the modified HBM are connected to the patient’s health beliefs regarding the different constructs, a central part of the definitions and coding rules was to capture how the participants perceived and thought about the different aspects and how it affected their behaviour. The categorisation matrix was tested on the data and refined after a discussion between the authors. This refinement continued as the analysis proceeded and consisted of more detailed descriptions of each construct to make the distinctions between them clearer. The meaning units related to the aim of the study or the categorization matrix were identified in the transcriptions. The meaning units were then coded, and subcategories and generic categories were made by grouping the codes based on their meaning, similarities, and differences (). The link between subcategories, generic categories and main categories was established using a constant comparing technique. In the final step of the analysis, the two constructs the efficacy of rehabilitation and the cost and benefits of rehabilitation were merged into one category due to their interrelationship. The first author had long experience of treating patients with flexor tendon injuries and had completed doctoral courses in qualitative methods. The last author was a senior researcher with experience in qualitative methods and long experience of hand therapy. The first author conducted the analysis independently and discussed the analysis continuously with the last author in a reflective work process moving between the text, codes, subcategories, and categories to establish that the results were founded in the data.

Table 2. An Example of the steps taken in the data analysis.

Results

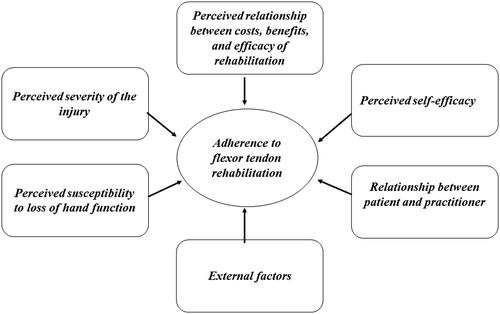

The results are presented in six categories: perceived susceptibility to loss of hand function; perceived severity of the injury; the perceived relationship between cost, benefits and efficacy of rehabilitation; perceived self-efficacy; the relationship between patient and practitioner; and external factors. Each category is explained below under the headings ().

Figure 1. An overview of the results in six main categories. The result of deductive analysis of the seventeen interviews using the Health Belief Model.

Perceived susceptibility to loss of hand function

The perceived susceptibility to loss of hand function concerning thoughts and feelings regarding future ability to perform activities, and the relation to exercise and daily hand use.

There were reports of fear of doing the exercises and using the injured hand. At the beginning of the rehabilitation, participants could describe fear and uncertainty about making something worse and not being able to use the hand in activities in the future.

Interview 9

“At the beginning I was very much afraid to make things worse with the exercises I was doing, I was afraid that if I used too much force, that something would happen with the injured tendon.” (Male, 31–50 years, injury to long finger on non-dominant hand)

The intrinsic meaning and impact of losing hand function were contextualized through activities such as not being able to play a musical instrument or participate in family life or work. Despite this fear and uncertainty, the perceived risk of losing hand function could also be a driver of motivation to do the exercises. At the same time, the fear of rupture or of making something worse modulated the execution of the exercise and the daily activities. The fear itself could be an advantage by promoting adherence to instructions and avoidance of excessive use of the injured hand.

Interview 1

“It was the fear of not being able to use the hand that made me do those exercises, which I think I did very well”. (Male, below 31 years, injury little finger on dominant hand)

Perceived severity of the injury

The participants’ perceptions of the severity of the injury and how it affected the adherence to rehabilitation varied. The injury could be considered as minor or more severe and this perception could also change over time. There were participants who expressed that the injury was not that severe and who had an extrinsic belief that the health care system would fix the injury. It took some time for them to understand the severity and the impact of the injury. The respect for the injury changed after an experience of tendon rupture or poor range of motion, and in retrospect, they could perceive the injury as more severe. In contrast, others perceived the injury as serious from the start and there were different reasons for this view. There could be a previous fear of cutting oneself in the hand, a traumatic injury event or previous experience of being injured. The cast was described as something that affected the view of the severity as it increased the feeling of being injured. Consequences of the perceived severity of the injury could be that activities and exercise were performed with caution, and it took some time for them to be convinced that the tendon would hold. The early start of high repetitions of the exercise was surprising and did not correspond to their view of the severity of the injury which affected the motivation to proceed with the exercises.

Interview 15

“At the beginning, the first and second months… I did not dare to do as much as I was told, but in the third month I used more force. I was afraid to injure the tendon again, and I would not like that…” (Male. 31–50 years, injury to index finger on non-dominant hand)

With an experience of rupture, the perception of the injury changed, and the view of the severity of the injury increased, as did the precautions taken during activity and exercise. Overall, the respect for the injury increased. The rupture was also described in retrospect as having been caused by a lack of understanding of the fragility of the tendon.

Interview 7

“I think about my presence in things I do, I don’t just proceed as I used to do, gather my things, and go, instead I go many times. This time I do things more by default, after the second operation. I have become more aware and maybe I did not understand how easily it could break, I understand this now, that it could happen. It really led to cautiousness, I think”. (Male, above 50 years, injury to little finger on non-dominant hand)

The impact of the time off work was also mentioned. Some participants felt that having a long time off work could have led to increased caution and better exercise. A longer time off work was described as a sign of the severity of the injury and to increase the time available for exercise.

Interview 4

“… if you are to cope with all the rehabilitation, it’s better that you take sick leave, and it will be longer than one month. Because then you have an idea when you talk to your employer and you can also prepare yourself. When the cast is removed then you must do exercises every hour, intensively. So you understand that, I probably took the injury too easy…” (Male, below 31years, injury to the thumb on non-dominant hand)

Perceived relationship between costs, benefits, and efficacy of rehabilitation

The participants described the perceived benefits and efficacy of adhering to rehabilitation and how it affected their behaviour. They also spoke of the perceived cost of adhering to rehabilitation, and how to manage rehabilitation by developing strategies.

To feel and see the benefits and the efficacy of performing the exercises was an important motivating factor, although participants thought it was hard to notice the results themselves. When the improvements from exercise were visualised and perceived it increased the motivation to continue.

Interview 13

(About the exercises)

Yes, it was good, completely ok. I did not understand the use of them then. Because they felt silly, it only took about ten – fifteen minutes to complete the programme, what difference could it make? But then I understood… that it gave results, I achieved a pinch grip rather quickly if I did the exercises seven times a day as I was told, so it was motivating, then I started to really exercise when I noticed that it truly helped. (Female, above 50 years, injury the thumb on non-dominant hand)

A feeling of frustration, impatience and resignation was described in the presence of too slow or no perceived improvement at all. The importance of visualising the improvement of hand function to gain motivation to continue was highlighted and measurements of range of motion of the injured finger were important during the process.

Interview 9

“Maybe you don’t see it by yourself because you are in it all the time, but when you meet somebody that you don’t see regularly, and they can see the difference, that makes you want to continue.” (Male, 31–50 years, injury to long finger on non-dominant hand)

Others had an intrinsic belief in the exercises, that the exercises would be beneficial for them.

This could be based on experience and previous knowledge of the importance of rehabilitation which affected their perception of the efficacy of rehabilitation.

Interview 3

(About the impact of experience of the rehabilitation)

“I understand the process and I understand the importance of sticking to the rehabilitation programme better. I think, it’s allowed to take some time and you need to follow the instructions. Not do too little and not too much to reach the goal.” (Male, above 50 years, injury to the thumb on non-dominant hand)

In contrast, some participants did not understand the usefulness of doing the exercises, which could be regretted later when experience from the current injury was achieved. A better understanding of the aim of each exercise and what could be anticipated in the end would have helped.

Interview 7

I believe that I could have done the exercises in a better way if I had understood the purpose of them. This exercise you do because of this. Then ok, then I should be able to interpret them by myself, I could have done them like this or support little in that way if only I had understood them from the beginning. (Male, above 50 years, injury to little finger on non-dominant hand)

There were also those who described the perception that it was not important to do the stated exercises exactly as they were shown. Instead, these participants spoke of just moving the fingers, and that everyday hand use replaced doing the exercises.

The perceived cost of rehabilitation and following the restrictions were difficulties with daily activities, pain and time needed for exercises. Managing everyday life with the restrictions and the cast on the injured hand was frustrating according to the participants. They spoke of struggling as many things were hard to do with only one hand. It was difficult and energy-consuming to manage all the things that needed to be done with only one hand. This led to the perception that using the injured hand in some way was inevitable. Developing strategies and learning how to perform activities with only one hand was one way to manage this and to reduce the cost of following the restrictions. In contrast, the cast was also perceived as a safety measure, and a reminder to be cautious.

Interview 10

“The cast did not hold that well but it was because I have children and I need to do stuff, it does not work when you are alone at home with two kids, you must be able to lift sometimes.” (Male, below 31 years, injury to little finger on dominant hand)

The pain was a major consequence of exercise, especially at the beginning of the rehabilitation, which led to modification in exercise behaviour. The pain was connected to a feeling of fear of making something worse. Exercises were skipped or adjusted to be less painful to perform. Although the pain was an exercise modifier it was also perceived as something that contributed to avoiding the use of the injured hand.

Interview 5

(About doing the exercises)

“It is not that easy, what should I say. Of course, if something is very painful then you cannot do that, you do a bit less of that. “(Male, below 31years, injury to index and long finger on non-dominant hand)

The exercises were perceived to be time- and energy-consuming, and the time available during the day influenced how much exercise was done. Returning to work led to less time to do the exercises. A way to manage this was to develop strategies, to set a clock as an exercise reminder, and to make exercise a daily habit.

Interview 6

“It was the time and my working situation that led to me being careless, that I didn’t have focus on rehab of the thumb all the time. “(Female, above 50years, injury to the thumb on the dominant hand)

Perceived self-efficacy

The participants’ beliefs in their own capability to perform the recommended treatment was influenced by their perception of themselves as a person where some viewed themselves as optimistic, and able to manage. They thought it was up to them, and they accepted the situation. Others expressed a lack of control in the beginning and relied on the health care system to take care of them.

Interview 8

“Because it was my first experience of health care in that way and I think that blood and wounds are creepy in general, I was not comfortable in that situation because I feel a lack of control.” (Female, below 31, injury to little finger on non-dominant hand)

Although self-efficacy could be perceived to be high, it fluctuated during the rehabilitation process and was modulated by different factors. Previous experience of injury increased the perceived self-efficacy, and experience of exercise and competition in sports, in general, was also seen as an advantage.

Interview 10.

“Belief in myself, no that did not change, rather it improved because of my experience, as I told you, it is about the other two fingers (previous injury), I was more careless about them, so rather, the responsibility rested more with me. “(Male, below 31years, injury to little finger on dominant hand)

In the absence of perceived improvements, the participants described how self-efficacy could decrease, and feelings of doubt regarding their ability to manage the recommended treatment were expressed.

Relationship between patient and practitioner

Participants’ view of the relationship and interaction with the occupational therapist and physiotherapist, was, in general, positive but could also impact their adherence to being cautious and exercising. The information and communication were described as helpful which facilitated the exercises. The appointments with the health care service were comforting since answers to raised questions were given and doubts were addressed. Revisits were also helpful to see progress in rehabilitation and stimulated motivation to carry on with the exercises. Regular revisits to the same person were highlighted as especially beneficial.

Interview 8.

“And I believe that having regular revisits all the time, has helped me quite a lot; then you receive check-ups to see if there is any progress or not. “(Female, below 31, injury to little finger on non-dominant hand).

Despite this, there could be expressions of uncertainty among the participants about the strength of the injured tendon, and what activities in daily life the participants could engage in, and to what extent.

Interview 4

“Then it is a bit hard to feel the balance, how much or how little you are allowed to do during this time, it is hard to know. In principle, what I have understood is that nobody can say if there is a particular level [of how much the hand could be used in activities].” (Male, below 31years, injury to the thumb on non-dominant hand)

There were also participants who expressed that the instructions were too general and that more personalized instructions would have been beneficial. Difficulty to take in all the information during the appointments was also expressed, and some said that the instructions were complicated.

Interview 14

“I did those exercises but then it was shown that it was not correct, the therapist said that it was difficult to explain…but I just felt it was difficult.” (Female, 31–50 years, injury to little finger on dominant hand)

External factors

The participants’ social and environmental context outside health care influenced their adherence to rehabilitation and modulated their behaviour. The social interactions with other people close to the participants were perceived as helpful. Friends, colleagues, and family helped them to perceive improvements and to understand the injury, which motivated the participants to carry on with the exercise.

Interview 6

“I believe I have listened very much to a special colleague that also is one of my closest friends, that has a new knee [prosthesis] and we call here “the nurse” at work, but she is good at rehab also and she has encouraged me.” (Female, above 50years, injury to the thumb on the dominant hand)

In contrast to this, there were participants who reported struggling with the roles in an ordinary family life when injured. They described a feeling of not being able to contribute or of not being independent in daily activities.

Interview 17

“The mental struggle with your self is the biggest [problem] in general. Suddenly, how should I express myself…, that you can’t contribute… you need to adapt to things you have taken for granted. Take your clothes off or be able to wear a particular outfit, or be able to take a shower or help out at home… that’s a struggle I have felt more than to have a splint on…” (Male, 31–50 years, injury to the thumb on dominant hand)

The participants’ social context in which the rehabilitation occurred affected how the participants perceived the potential cost and benefit of adhering to the protocol. There were participants who mentioned that they avoided doing exercises in some social circumstances, due to a desire not to do them among people at work. In contrast, friends and family also helped participants to cope with the injury and manage everyday tasks and follow restrictions.

Interview 13

“Yes, if I do something with my left hand, then the kids or a colleague is there and asks me what are you doing? “(Female, above 50 years, injury to the thumb on non-dominant hand)

Discussion

This study provides a new perspective on adherence to flexor tendon rehabilitation, connecting participants’ experience and perception to behaviour theory. The study shows that the participants’ perceived beliefs in relation to the constructs in the HBM are of importance as they affected their adherence to exercise and restrictions.

The participants’ perceived level of threat of the injury in terms of severity and susceptibility affected their behaviour, a higher perceived threat increased their motivation to exercise and to be cautious in activities. The perception regarding the cost and benefits of rehabilitation, and self-efficacy also affected their adherence. The benefits or efficacy of doing exercise and following restrictions were compared to the cost of doing so, leading to behaviour among the participants that had a perceived low cost and high benefit. In addition, external factors and interaction with therapists influenced their perception of the severity of the injury and adherence to exercise and restrictions. Thus, the explanation of adherence by the perception of the constructs in the HBM is not simple and direct as it varied over time and between individuals.

In our study, the susceptibility to loss of hand function concerned the future ability to use the hand and perform activities, which indicates a desire to return to normal hand function. This is consistent with previous qualitative research by Smith-Forbes et al. on patient adherence after upper extremity injury where the participants expressed a desire to return to normal function which highly determined adherence [Citation19]. Research on adherence and the relation to injury threat is inconclusive. Some suggest injury threat is a predictor of adherence [Citation20], while other research shows no such connection [Citation21]. The present study shows that patients’ perceptions of the overall severity of a flexor tendon injury are complex and may vary over time which may be one explanation why the relation between injury threat and adherence is not clear. Providing information regarding the injury and its’ consequences to the patient on several occasions and in different ways may be an important part to consider in the treatment of patients with flexor tendon injuries, considered when creating a hypothesis for future intervention studies. Nevertheless, more research is needed on how patients perceive their injury and the effects on adherence after flexor tendon injury.

To perceive the exercise as an effective and beneficial created motivation among the participants in our study to continue doing it. The importance of perceived benefits of adhering to treatment has been shown in previous research regarding adherence to a splinting regime [Citation22]. The recovery process after flexor tendon injury can be slow with small and gradual improvements, and the participants in our study felt that it was hard to perceive them. Visualising improvements to patients to enhance adherence during flexor tendon rehabilitation may be considered when designing future interventions. Several previous studies have established that a perceived barrier and cost affect adherence [Citation8,Citation21]. In our study, one perceived cost was managing everyday life with a cast on the injured hand, which felt frustrating and led to a feeling that it was unavoidable not to use the hand. Similar to our research, previous studies have shown that patients struggle and feel frustration when facing these difficulties [Citation23], and the need for strategies to reduce the cost of managing everyday life could be a way to improve adherence to wearing a splint [Citation10].

Self-efficacy has also been shown to affect adherence in previous research [Citation24,Citation25] and increasing self-efficacy should be considered as an intervention to improve adherence to therapy in upper limb conditions [Citation26]. Among our participants, there were those who expressed a high self-efficacy in general which is similar to previous research on rehabilitation of flexor tendon injuries [Citation27]. However, our study also showed that self-efficacy could vary over time and was affected by previous experiences of injury and exercise. Therefore, the timing of assessing or discussing self-efficacy with the patient may be considered together with previous experiences when meeting patients, as previous experiences also affected the perceived benefits of rehabilitation and the severity of the injury.

The interaction between patient and therapist is complex, involving several different areas, for example how the communication is done, when it is done, and how it is interpreted and adopted. Our participants perceived the interaction as beneficial in general but in contrast, the experience of complex and lacking personalised instructions was also reported. Patients recall less than half of the instructions given during flexor tendon rehabilitation [Citation28]. Making the instructions less complex, for instance, simplified exercises or helping the patient to understand the most crucial information by taking more time to explain may be useful. Also, taking external factors into accounts, such as including support from friends or family to cope with the large amount of information provided regarding the injury and rehabilitation could be ways to improve [Citation29].

The results of our study also include external factors as they had an indirect impact on the participants' descriptions of adherence. This emphasizes the importance of not only taking internal factors into account but also being aware of the patient’s individual context. Previous research has shown the importance of social support when coping with traumatic hand injuries [Citation30] and its positive effect on adherence to home-based exercise [Citation25]. In research by Fitzpatrick on patients with flexor tendon injuries, participants felt that social support was required to engage in normal activities [Citation31]. We found a similar result with our participants who experienced the need for both practical and emotional help from others. The importance of social support could therefore be emphasised in clinical practice or future intervention as one way to lower the patient’s cost of adhering to restrictions.

Trustworthiness

The method of directed content analysis is valuable when a prior theory or research exists and can help to expand, refine, or validate the existing theory and contribute to knowledge building [Citation16]. The HBM, originally derived from work by Rosenstock [Citation32] is one of the most used models to explain health behaviour [Citation12]. It was adapted by Groth [Citation13] for hand rehabilitation, but it has not been tested in the context of flexor tendon rehabilitation. A directed content analysis approach has benefits and limitations. Using the modified HBM in the present study increased credibility as it systematised the data collection and analysis. The restrictions of the theory and the likelihood of biased findings were handled by the potential inclusion of new categories for codes not matching the coding matrix [Citation33]. Furthermore, to improve confirmability we applied an audit process [Citation16], which ensured that the findings were grounded in patient data. The interrelationship between the constructs in the model demanded careful consideration during analysis and was performed in a reflective work process. A consequence was that two of the constructs were merged into one category (cost, benefits and efficacy of rehabilitation) during the end of the analysis. Having used the constructs from the modified HBM does not allow for saying that the model is applicable on its whole as an explanation to findings of the present study. However, it provides insight regarding adherence behaviour that can be useful to consider when developing interventions for patients with flexor tendon injuries. The sample in the present study is small and the results may be limited to the study context. However, the participants had a mean age of 39, and about 35% were women which are considered as representative for the population. Furthermore, we strived to obtain a sample of participants with varying experiences of flexor tendon injury and rehabilitation to increase transferability. One limitation of the present study is that the participants tended not to be willing to admit to particularly non-adherent behaviour. We aimed to address this issue by using a conscious interviewer approach [Citation34], building trust and asking questions in a way that was non-judgemental and indirect.

Conclusion

The present study shows that patients’ perception of the injury, the effectiveness of exercises, context and social support to manage daily life affected adherence to restriction, motivation and commitment to rehabilitation. The HBM as a theoretical framework can be beneficial for understanding factors that influence patients’ adherence.

Interview_guide.docx

Download MS Word (16.2 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank colleagues at the Departments of Hand Surgery in Stockholm, Malmö and Linköping, Sweden for practical support.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Manninen M, Karjalainen T, Määttä J, et al. Epidemiology of flexor tendon injuries of the hand in a Northern Finnish population. Scand J Surg. 2017;106(3):278–282.

- Dy CJ, Hernandez-Soria A, Ma Y, et al. Complications after flexor tendon repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(3):543–551.e1.

- Starr HM, Snoddy M, Hammond KE, et al. Flexor tendon repair rehabilitation protocols: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(9):1712–1717.

- Groth GN, Wilder DM, Young VL. The impact of compliance on the rehabilitation of patients with mallet finger injuries. J Hand Ther. 1994;7(1):21–24.

- Lyngcoln A, Taylor N, Pizzari T, et al. The relationship between adherence to hand therapy and short-term outcome after distal radius fracture. J Hand Ther. 2005;18(1):2–8. quiz 9.

- Harris SB, Harris D, Foster AJ, et al. The aetiology of acute rupture of flexor tendon repairs in zones 1 and 2 of the fingers during early mobilization. J Hand Surg Br. 1999;24(3):275–280.

- Peck FH, Bücher CA, Watson JS, et al. A comparative study of two methods of controlled mobilization of flexor tendon repairs in zone 2. J Hand Surg Br. 1998;23(1):41–45.

- Kirwan T, Tooth L, Harkin C. Compliance with hand therapy programs: therapists' and patients' perceptions. J Hand Ther. 2002;15(1):31–40.

- Sandford F, Barlow N, Lewis J. A study to examine patient adherence to wearing 24-hour forearm thermoplastic splints after tendon repairs. J Hand Ther. 2008;21(1):44–53.

- Kaskutas V, Powell R. The impact of flexor tendon rehabilitation restrictions on individuals' independence with daily activities: implications for hand therapists. J Hand Ther. 2013;26(1):22–28; quiz 29.

- Becker MH, Drachman RH, Kirscht JP. A new approach to explaining sick-role behavior in low-income populations. Am J Public Health. 1974;64(3):205–216.

- Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, et al. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):323–344.

- Groth GN, Wulf MB. Compliance with hand rehabilitation: health beliefs and strategies. J Hand Ther. 1995;8(1):18–22.

- Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. Vol. 3. West Sussex (UK): Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, et al. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. 2018;23(1):42–55.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Strickland JW, Glogovac SV. Digital function following flexor tendon repair in zone II: a comparison of immobilization and controlled passive motion techniques. J Hand Surg Am. 1980;5(6):537–543.

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–1907.

- Smith-Forbes EV, Howell DM, Willoughby J, et al. Adherence of individuals in upper extremity rehabilitation: a qualitative study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(8):1262–1268.e1.

- Sluijs EM, Kok GJ, van der Zee J. Correlates of exercise compliance in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1993;73(11):771–782. discussion 783–6.

- Carpenter CJ. A Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Commun. 2010;25(8):661–669.

- O'Brien L, Presnell S. Patient experience of distraction splinting for complex finger fracture dislocations. J Hand Ther. 2010;23(3):249–249; quiz 260.

- Fitzpatrick N, Finlay L. Frustrating disability: the lived experience of coping with the rehabilitation phase following flexor tendon surgery. Int J Qualitative Stud Health Well-Being. 2008;3(3):143–154.

- Jack K, McLean SM, Moffett JK, et al. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15(3):220–228.

- Essery R, Geraghty AWA, Kirby S, et al. Predictors of adherence to home-based physical therapies: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(6):519–534.

- Cole T, Robinson L, Romero L, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to improve therapy adherence in people with upper limb conditions: a systematic review. J Hand Ther. 2019;32(2):175–183.e2

- Svingen J, Rosengren J, Christina T, et al. A smartphone application to facilitate adherence to home-based exercise after flexor tendon repair: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2021;35(2):266–275.

- Kortman B. Patient recall and understanding of instructions concerning splints following a zone 2 flexor tendon repair. Aust Occup Ther J. 2010;39(2):5–11.

- Supp G, Schoch W, Baumstark MW, et al. Do patients with low back pain remember physiotherapists' advice? A mixed-methods study on patient-therapist communication. Physiother Res Int. 2020;25(4):e1868–n/a.

- Gustafsson M, Persson L-O, Amilon A. A qualitative study of coping in the early stage of acute traumatic hand injury. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(5):594–602.

- Fitzpatrick N. A phenomenological investigation of the experience of patients during a rehabilitation programme following a flexor tendon injury to their hand. Hand Therapy. 2007;12(3):76–101.

- Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education & Behavior. 1974;2(4):328–335.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115.

- Flick U, Von Kardoff E, Steinke I. A companion to qualitative research. London: SAGE; 2004.