Abstract

Purpose

To describe patients’ perceived and expected recovery 1 year after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH).

Materials and methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 16 persons 1 year after aSAH. Inductive manifest qualitative content analysis was used.

Results

The analysis resulted in two categories and seven subcategories. The category “A spectrum of varying experiences of recovery” includes four subcategories describing physical recovery, mental recovery, alterations in social life, and perceived possibilities to return to normality. Some informants felt that life was almost as before, while others described a completely different life, including a new view of self, altered relationships, not being able to return to work, and effects on personal finances. The category “A spectrum of reflections and expectations of recovery” comprises three subcategories depicturing that expectations of recovery were influenced by existential thoughts, describing what they based own expectations of recovery on, and how expectations from others influenced them.

Conclusions

aSAH was perceived as a life-changing event. The changes impacted on informants’ view of self and relationships, and they perceived new barriers in their living conditions. Lack of information on expected recovery was expressed and expectations of recovery were at times unrealistic.

Contracting an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) is a life-changing event with possible impact on a variety of areas in daily life.

There is a need for improved information to aSAH survivors and their significant others on the course of the recovery and possible long-term consequences.

aSAH survivors may need assistance to balance unrealistic expectations on recovery.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death in the world. Disability and the stroke burden vary between stroke subtypes concerning incidence and mortality. Subarachnoid hemorrhage accounts for up to 9% of all strokes [Citation1] and is most commonly caused by a ruptured intracranial aneurysm [Citation2]. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) is more preponderant in women [Citation3] and occurs more often at a younger age in comparison to ischemic strokes [Citation4]. Long-term affected health-related quality of life after aSAH is common and is significantly worse in comparison to the general population [Citation5]. Approximately 19% of patients are dependent on help for activities in daily life in the first year after the aSAH [Citation6]. Persistent physical fatigue is prevalent and has been found to be associated with reduced participation in activities of daily living 4 years after aSAH [Citation7].

Psychological consequences are also common after aSAH, in terms of anxiety and/or depression [Citation8] and emotionalism [Citation9]. Psychological well-being and cognitive functions are inter-connected; higher levels of psychological well-being are associated with better cognitive function, while deteriorating cognitive functions may lead to worse psychological well-being [Citation10]. The cognition may be affected in several ways after aSAH, with for instance impaired memory, affected perception, and executive functions [Citation11,Citation12]. Another aspect of cognitive dysfunction after aSAH is mental fatigue [Citation13], which means individuals can put effort into mental activities only for short periods, leading to exhaustion and a longer time to regain energy [Citation14].

There is no standard definition of the concept recovery, but most commonly means a period of returning to health or a former condition after sickness [Citation15], defined by comparative standards and include to regain control over physical, psychological, social, and habitual functions [Citation16]. Recovery can be viewed objectively through health assessments or subjectively including individuals’ own perceptions of recovery or being recovered [Citation15].

There is increasing evidence that patients’ expectations influence their treatment outcomes, which has been shown in patients with various medical conditions [Citation17] and in connection with surgery [Citation18]. Patients’ expectations of outcome are not merely what they would like to happen, but can be defined as conscious, predictive future-directed beliefs concerning specific events or experiences [Citation17].

Rehabilitation is defined by the World Health Organization as “a set of measures that assist individuals who experience, or are likely to experience, disability to achieve and maintain optimal functioning in interaction with their environments” [Citation19,p.96]. It is common that individuals recovering from stroke have long-term persistent disabilities. The need for post-stroke rehabilitation is greatest in the first year after the onset, but improvement can continue several years after stroke, and patients’ needs may vary over time [Citation20]. Rehabilitation outcomes after stroke are connected to the patient’s expectations about their capabilities (self-efficacy beliefs), which can influence their motivation, the goals they set and how much effort they invest in achieving those goals [Citation21]. Differences in expectations of recovery between patients and healthcare professionals have previously been described: persons with stroke are more likely to rate their recovery by the extent to which they can perform activities they considered important before the stroke, while healthcare professionals evaluate the degree of recovery from the performance of activities of daily life (such as the ability to walk) [Citation22]. Low perceived recovery after aSAH has been associated with higher levels of anxiety 2 years after the onset [Citation8].

The literature provides numerous quantitative results on symptoms and impairments after suffering from an aSAH [Citation23–27], indicating a low ability to regain health and return to previous life [Citation28–30]. The timing of outcomes and endpoints varies substantially in quantitative follow-up studies after aSAH, which complicates interpretation of results between studies. Therefore, long-term outcome assessments at 3 and/or 12 months have been recommended [Citation31]. But qualitative descriptions of patients’ own experiences on recovery are scarce. Qualitative research designs are particularly valuable to give a deeper understanding of patients’ expectations, perceptions, and behaviors, and the meaning attached to them – in contrast to quantitative designs [Citation32]. The existing qualitative studies on recovery after aSAH differs in objectives, methodology and results; perceived consequences of the aSAH that affect recovery are partly described [Citation33–36], as well as coping strategies [Citation33]. Expectations on recovery are only briefly mentioned [Citation34,Citation36].

Increased knowledge on aSAH patients’ perceived and expected recovery is important for healthcare professionals, patients and their significant others regarding what to expect during the recovery period, and the possibility to balance unrealistic expectations.

The aim in this study was to describe patients’ perceived and expected recovery 1 year after aSAH.

Materials and methods

A qualitative, inductive, and descriptive approach with naturalism as the theoretical foundation was used, with the intention of staying close to the data [Citation37,Citation38]. The study is inductive since the aim was to describe patients’ perceptions unbiased.

The Consolidating criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist [Citation39] was used to ensure quality reporting of this study.

Sample

The informants had been treated for aSAH at a large university hospital in Sweden. According to the clinical guidelines, aSAH patients are followed-up with a medical check-up 3 months and 1 year after the event. The informants were recruited from the Neurosurgical clinic’s registry on patients that were to be called for the 1-year follow-up visit. The inclusion criteria were being scored 3–5 on Glasgow Outcome scale (GOS) [Citation40] at hospital discharge, able to communicate in Swedish and to sign informed consent. Maximum variation sampling was used, including both sexes, varying ages, residence areas (urban or rural areas) and treatment regimens (open surgery or endovascular procedure). The potential informants were first contacted by phone and received oral information about the study. If they were interested in participation, written information and an informed consent form was sent to their home addresses. Those who accepted participation were thereafter contacted once again by phone to decide time and place for the interview. A total of 18 former patients were approached by phone, whereof two declined participation without giving a reason. The remaining 16 agreed to participate.

Data collection

An interview guide was used with open questions concerning perceived differences after the aSAH, with the following probing topics: social life, physical ability, work/daily activities, cognition, personality and mood, relationships with significant others and friends. Further, also questions on expectations of recovery, if their expectations changed over time and what they based their expectations on. Since the interview guide consisted of few open questions and probing topics, pre-testing was not considered necessary. Data were collected through individual interviews in Swedish. Individual interviews were chosen since the informants were considered vulnerable [Citation41] due to possible affected cognition [Citation42], thus the setting ensured tranquility and the possibility to talk about very personal issues. All but two interviews were conducted in a secluded room at the hospital. The other two interviews were conducted by phone (preferred by the informants). The data collection period ranged from March to December 2015. All interviews were conducted by the first author, who is well-trained and experienced in undertaking individual interviews. The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and additional field notes were taken. The first author had not been involved in any clinical care of the informants, and the aim and reasons for conducting the research was addressed in the information letter. The median duration was 42.5 min (range 24–75 min). Relevant quotes were translated into English by the first and last authors and were discussed with a native English-speaking person outside the research group before they were added to the result section to further illustrate the findings.

Ethical considerations

A signed informed consent form was obtained from each informant. In the study information, voluntary participation was emphasized, and confidentiality was guaranteed. Transcribed interviews were pseudonymized with interview-specific code numbers to ensure that identification of the informants was not possible, and only the first author had access to the identifying code list. The Stockholm regional board for ethics of research involving humans approved the study (registration number 2014/2182-31/4).

Data analysis

The inductive manifest content analysis followed the approach described by Graneheim and Lundman [Citation43,Citation44] by all authors reading four transcripts of the interviews each, extracting meaning units, condensing those, and applying codes to the meaning units. Thereafter all codes were compiled by the first author and discussed among all four authors until consensus, and categories and subcategories were created together, ensuring they were externally heterogenous and internally homogenous [Citation45]. shows examples from the analysis process.

Table 1. Examples of meaning units, condensed meaning units, subcategories and categories.

Results

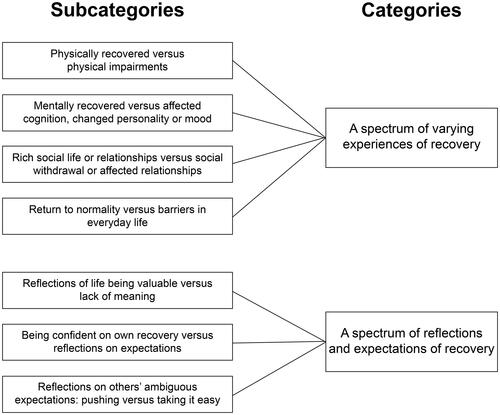

Characteristics of the informants are presented on a group level to ensure confidentiality (). Quotes are presented with the informants’ pseudonymization numbers, interview timing, and whether age was below or above median age (51 years). The analyzed data resulted in two categories: “A spectrum of varying experiences of recovery” and “A spectrum of reflections and expectations of recovery,” and a total of seven subcategories ().

Figure 1. Recovery 1 year after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, subcategories, and categories.

Table 2. Characteristics of participants.

A spectrum of varying experiences of recovery

Physically recovered versus physical impairments

This subcategory includes descriptions of informants’ experiences of being physically recovered, as well as symptoms and impairments after the aSAH, implying that the previous physical condition not yet was restored. A complete physical recovery, or few marginal changes were described by some informants:

I still lack energy some days. Gets a headache when it gets too much. Located right next to the scar, it is not a common headache. […] Apart from that, it feels like I am completely recovered, as if it had never happened. But then the headache reminds me, it has actually happened. (Informant 6, interviewed 525 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Active strategies to enhance recovery were described; a faster physical recovery was facilitated by regular physical exercise, being more responsive to bodily signals, and stress-reducing activities. They created time on their own, put up limits toward others, spent time in nature, and rested more. Some informants expressed that they had an own responsibility, that their recovery partly depended on themselves and their own stubbornness and willingness:

I believe a lot also depends on oneself. How one view things, how one deals with life. […] I believe one needs to have the will. If you have no desire to do so… I think it’s so easy to just sit down and just ‘no, it’s not possible.’ (Informant 6, interviewed 525 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Contrary, other informants described severe symptoms and physical impairments: balance problem, needing walking aids as well as learning how to walk the stairs again. Also, for some, dizziness and shakiness remained 1 year after aSAH. General pain was described, and headache was common, perceived as constant and different than their usual headache:

24-7, all time while awake I have a headache. […] And the balance gets worse if I am tired and have a headache, so I stumble and so. (Informant 13, interviewed 365 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

There were descriptions of influenced sensory organs, such as not being able to take in several visual impressions at the same time, having tinnitus, increased photosensitivity, or changes to or lost smell and taste. Physical fatigue and having lower energy than before aSAH influenced everyday life, such as being unable to take a walk or have a functioning social life. Some informants described being so exhausted that they just wanted to stay at home. One informant described the physical fatigue as follows:

Then just ‘bang’. Then it’s like syrup and it feels that I need to sleep for half a year, that I could fall asleep standing […] It’s 200 meters home and I feel ready to cry because I just don’t know how I’ll be able to walk home. Because it’s so difficult, you know, it’s such a challenging tiredness. (Informant 13, interviewed 365 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Mentally recovered versus affected cognition, changed personality, or mood

This subcategory consists of the informants’ descriptions of mental recovery in terms of psychological health including mood, personality, and perceived cognitive status. The informants’ descriptions varied considerably, some perceived themselves as being the same as before the aSAH, while others described having to adapt to be a new person with impairments. One informant feeling mentally recovered expressed:

I think I'm the same. But the difference is that I … maybe set more boundaries … because I know I have to, to feel good. The most important thing of all is to get well. (Informant 11, interviewed 379 d after asAH, aged above median age)

Some of the informants were cognitively affected and in addition to their narratives it was noticeable that they lost the thread in the conversation and forgot which question they were answering and what they planned to say. The informants described different aspects of memory problems affecting everyday life, for instance:

I forget my medicines, I forget to cook meals, I forget to get dressed. I can go out completely wrongly dressed, forget the jacket even though it’s winter […] I forget to put on socks even though the temperature is below zero. I do a lot of crazy things, I lose things, forget things and put things in the wrong places. (Informant 3, interviewed 400 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

Affected perception, such as difficulties keeping up with the action when watching a movie or reading a book, or a feeling of everything moving in slow motion was described. Some informants mentioned that they had lost their multi-tasking ability.

I've always been able to spin many plates in the air. Now I can't. I have to focus on and do one thing at the time. (Informant 3, interviewed 400 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

Mental fatigue was described by the informants, which affected the social life, and was denoted for instance as sensitivity to noise and inability to stay in crowds:

I cannot stand when there are lots of impressions, talk, life and movement. Then I get so tired that I just want to sleep, go home and sleep. It is too much for my head. (Informant 5, interviewed 506 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Problems regarding executive cognitive functions were also described i.e., taking the initiative less, difficulties in planning and getting started with activities, lack of perseverance, difficulties in completing tasks and procrastination behaviors. The affected cognition and striving to gain control over one’s life was described as strenuous, and sometimes led to not seeing friends or even not going out:

I can get a black-out when I am going to cross a road. I can’t walk if a car is coming, so what do I do? I just stand there and refuse to cross the road, because it is completely still in my brain. So, I try to avoid going out. Because it sometimes happens that it feels completely… empty in my brain and I don’t know where I am, what I was going to do or where I am headed. (Informant 5, interviewed 506 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Most informants felt that they had a different mood or a different personality than before. Increased emotional lability, for instance starting to cry more easily, was commonly mentioned. Some described more noticeable moods, such as becoming angry or irritated more easily, or being meaner and more brusque. The perceived personality changes varied. Some said they had become more introverted, while others said they were extroverted now. Some said they felt a lack of patience. On the other hand, others described being calmer now that the emotional range had shrunk and that they felt more subdued:

I believe I am more introvert and have become blunted. So, I am calmer in that way. I’m not getting exited anymore. (Informant 2, interviewed 442 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Rich social life or relationships versus social withdrawal or affected relationships

This subcategory encompasses descriptions of functioning in interactions with significant others and friends, perceived relationships and range of social or leisure activities. There were descriptions of altered relationships with the closest relations. Positive changes mentioned included that some relationships were enriched by becoming closer to their significant others and relationships becoming much more important than before, and this was a source of happiness:

I have somehow regained contact with my sister and that is very important, I only have one sister. (Informant 8, interviewed 377 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

However, relationships were also strained. For those having children in the household, the relationships were described as being affected by conflicts when the children watched the parent and made comments on things the parent forgot, said or did wrong. Some informants perceived themselves as being a burden on their closest relations. Changed roles were described, such as the partner becoming a caregiver, or taking over all household work, or children taking on more responsibility:

When I was in hospital, she [daughter] took over my role. It was her who paid the bills, but from our accounts, and it was her who did everything. So, when I got back home, I took over those tasks from her again […] she had grown with it. And then I’m suddenly back, so she thought I could go back to the nursing home. (Informant 10, interviewed 411 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Some informants described intimacy and sexual relations as being negatively affected. There were descriptions of being sexually abstinent for more than a year, and lacking information on when sexual activity could be resumed, even when asking this as a direct question to the neurosurgeon at the three months follow-up visit. One informant described the affected intimate relation as follows:

Both regarding doing fun things together, as well as having sex and being intimate, that part of the relationship is gone […] we don’t manage that. I believe that my concentration… also have an impact, and the ability to be in the present. (Informant 12, interviewed 371 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Regarding social life and leisure activities, some said that contacts and engagements were the same as before aSAH, while others described changes. Changes included stronger relationships, exchange or loss of shallow friends, and descriptions of being pickier with social contacts, due to lack of energy.

[New friends] probably didn’t know how they should handle this. So, many of them are lost. While those I have known my entire life have come back. (Informant 2, interviewed 442 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Some described avoidant strategies, choosing a limited social life or even social withdrawal:

I find it almost a relief to just shut the door and turn off the phone and just ‘you can’t reach me.’ (Informant 6, interviewed 525 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Return to normality versus barriers in everyday life

This subcategory comprises the informants’ description of attempting to return to their previous everyday life and perceived barriers when doing so, which implies for instance returning to work and take responsibility for the economy. Those informants who returned to work, did so to their previous workplaces. They received support from their colleagues and managers, and they dared to ask for help. The informants described having a new insight into their own limitations, needing breaks to cope, and working slower than before, resulting in the return feeling tough.

I started working [eight months after aSAH] at 25% (snivels). I thought I would die from it (laughs). I was so tired, so tired! Two hours at work is not much […] I started with two hours, then I went up to four, six eight. But it was tough, really tough to go back to 100%. (Informant 6, interviewed 525 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Driving cessation had major consequences. Some got their driver’s license back after a few months and after struggling with tests, while others had not yet received theirs back. The informants found the time without a driving license difficult, especially those living on the countryside. They felt a lack of freedom and became dependent on relatives or friends to be able to shop or were unable to return to work as a professional driver.

I couldn’t get anywhere, they took my driver’s license. I live about 25 kilometers from the nearest store and pharmacy. So, that was pretty tough. I had to get help all the time. (Informant 1, interviewed 379 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

I have had epilepsy seizures, and that is a barrier because I am not allowed to drive a car. […] I am still on sick leave because I cannot continue as a professional driver. (Informant (14, interviewed 418 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

Finances were negatively affected after the aSAH when the informants had less money in sickness compensation than their previous salary. It was difficult to manage on very little money and they received financial contributions from significant others.

I was on sick leave and had rather low sick pay, so that affected me. (Informant 16, interviewed 370 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

A spectrum of reflections and expectations of recovery

Reflections of life being valuable versus lack of meaning

This subcategory contains the informants’ existential reflections, when they after a while understood that they had been close to death, an insight that was built on over time. There were rich descriptions of thinking differently about life and death, thinking that life is fragile and thereby valuable, feeling grateful for life. This also affected future perspectives and planning:

I realize I can die tomorrow, so that is different. Live for the day, that is how I think now. There is no long-term planning anymore. […] I earn lots of money and I use them, not for drugs or partying, but for living a good life. (Informant 15, interviewed 365 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Still, there were descriptions of trying to find a meaning in what had happened or feeling indifferent and wanting to give up:

When you have been so close to die, I think you need to see reality, life, from different angles. […] it's hard to find the meaning, as well as to move on. (Informant 2, interviewed 442 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Descriptions varied from experiences of a totally different life with uncertainties to perceptions of being back to previous everyday life. There were descriptions of initially trying to capture the experience and being grateful for life but as time went by, not reflecting upon the existential aspect of life anymore.

Being confident on own recovery versus reflections on expectations

This subcategory incorporates the informants’ thoughts about their expectations of recovery, what they founded their expectations on. The informants lacked information from healthcare about what to expect considering the recovery after an aSAH. As a result, they were not aware of their individual prognosis and possibilities.

The information was insufficient, someone, a doctor maybe could have told me: ‘I have now written a medical certificate for three months, but that is just the beginning. Your family doctor will continue to refer you on sick leave. You can expect that this will probably last for a year.’ (Informant 2, interviewed 442 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

There were reflections on how the recovery would turn out, how they would feel in the future and how they would be able to handle themselves. Some described being confident as they felt alert and were sure that everything was going to be all right:

I had no problem speaking, I had no paralysis or anything. So that was not the case, I wasn’t that worried … I just assumed I would be pretty good. (Informant 8, interviewed 377 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

They compared themselves with others they had met at the hospital or rehabilitation center who had suffered from a cerebrovascular event. There were descriptions of being lucky to have managed so well after their aSAH when comparing themselves to others worse off, but also finding out that they had worse symptoms than others:

When I was at rehab for two months this spring, I noticed that […] this mental fatigue and concentration [problems]… that not everyone had it. (Informant 12, interviewed 371 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

On the contrary, some informants pushed themselves and thought that their recovery was slow and that their symptoms were unusual. There were also descriptions of unrealistic expectations, as informants initially thought they would be just as before the aSAH:

I thought when I was at the rehabilitation hospital ‘when I have been discharged from here, I will start working immediately.’ (Informant 4, interviewed 457 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

Contrarily, some dared not to have any expectations of recovery or their future life:

I had no expectations at all. I don’t think I was so aware that I thought ahead. I probably just thought that this day must pass. (Informant 9, interviewed 381 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

As time went by and they had less pain and took fewer painkillers, they were enlightened that their recovery would take longer time than expected and an insight that they would have a changed life came gradually, when realizing the whole magnitude of symptoms and sometimes lost abilities.

I received a medical certificate for three months, and I thought: ’Great! Within three months I will be up and running again and can apply for a full-time job’. Then I had contact with an occupational therapist, and she said: ‘you’d better calm down, you can start talking about that in a year’. And I just ‘what?!’ (Informant 2, interviewed 442 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Reflections on others’ ambiguous expectations: pushing versus taking it easy

This subcategory consists of the informants’ narratives on others’ expectations on their recovery, including significant others, friends, and healthcare professionals. They expressed that the lack of visual signs of their condition could be ambiguous. It was difficult for anyone to understand what they could manage or not when problems they had were not visible on the outside. On the other hand, it was a relief that all their problems were not obvious for everyone to see. When meeting people, some informants said that they made an effort to conceal that they were different compared to before:

I have not been paralyzed and have no speech difficulties. But these other things I have, of course, people don’t notice, because I disguise it. (Informant 8, interviewed 377 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

They also listened to healthcare professionals’ assessments based on the symptoms and signs that were possible to observe. Sometimes they felt that they were compared to previous patients with aSAH. Informants expressed being disappointed when even healthcare professionals assessed them from how they looked.

When the doctor looks at me and says Oh, what you look lively and fresh!’ Well, they just see the outside, they don’t see how messy it is in my head. And it's frustrating when even the neurologist says ‘oh, you look so lively and fresh.’ (Informant 3, interviewed 400 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

Some informants said that others expected everything to be as before the aSAH:

People expect a lot more from me than I can handle now. (Short break) And that’s tough… Because it would have been easier if I had some kind of damage that was visible. Now they think, they can say ‘come on, you’re just lazy’ or something like that when I say I can’t manage, I need to rest now (pause, sniveling followed by a deep sigh). (Informant 3, interviewed 400 d after aSAH, aged below median age)

In contrast, some informants described being stopped by friends or significant others while pushing themselves too hard:

She [a neighbor] visited me on a more or less daily basis. When she saw me doing something, she scolded me: ‘you mustn’t do that!’ she said. (Informant 1, interviewed 379 d after aSAH, aged above median age)

Discussion

This qualitative study aimed to describe the informants’ perceived and expected recovery in the first year after aSAH. The findings illustrate a broad spectrum of perceptions and expectations, from descriptions of returning to life almost as before to a totally different life including altered view of oneself and relationships, changed social life and existential concerns. The informants’ expectations of recovery were sometimes unrealistic and were influenced by existential thoughts, comparisons with others, and others’ expectations. The results are clinically useful in several ways; a deeper understanding on patients’ expectations and perceptions of recovery can help clinicians to enable support and balance unrealistic expectations. The results may also be useful to patients to normalize their experiences during the recovery period, and for their significant others for a wider understanding.

Some informants described lack of mental energy and concentration problems, which affected their perceptions of recovery and they identified as mental fatigue. They also described tearfulness, irritability, sensitivity to light and loud noise, which may be associated symptoms to mental fatigue [Citation46]. There were also expressions that others expected more than one was able to handle and being considered lazy. Mental fatigue is an invisible problem [Citation46], and a previous study found that 30% of family and friends interpreted fatigue as laziness [Citation47]. The common occurrence of long-term mental fatigue after aSAH is confirmed in a recent study, where the prevalence comprised slightly less than half of patients [Citation23]. To alleviate mental fatigue, the condition needs to be identified and measured, general recommendations need to be provided to patients (i.e., avoid over-exertion, regular rest, planning activities, and prioritizing tasks) and available treatments need to be considered [Citation46].

One factor relating to others’ expectations of recovery was the lack of visible signs regarding what problems the informants had. This was described as ambiguous, but also dependent on the situation the informants were in. Expressions of disappointment toward healthcare professionals were obvious, when informants felt that their health condition was assessed to be synonymous with how they looked. Contrarily, some informants described that they concealed their problems for others. To deliberately hide symptoms has previously been described after aSAH, resulting in stress and aggravated tiredness [Citation33].

The ability to return to work is a factor having a major impact on everyday life and the feeling of returning to normality and previous habits. The informants described various challenges related to the return and expectations not matching reality. Similar work-related challenges were reported in a recent cross-sectional study, where individuals suffering from aSAH described health problems, early retirement or need of another employment [Citation48]. Driving cessation was another factor having major consequences on their overall well-being, leading to a loss of independence. These results correspond to a study by Stepney et al. [Citation49], where persons described driving cessation due to neurological illnesses a loss of enjoyment in life, meaning losing a sense of normal adulthood, social participation, and of identity. In Sweden, the most common time interval for driving cessation after stroke is 3–6 months. The physician is responsible to inform the patient and follow-up the restriction, and to report to the responsible authority if the patient is unfit to drive [Citation50].

The informants described different strategies to handle specific situations, which could be viewed as coping, including active, and avoidant strategies. Active coping strategies are associated with more personal and social network resources and are used in connection with both negative and positive stressful life events, while avoidant strategies are associated with less resources and are used in connection with negative events [Citation51]. The relation between avoidant coping and depression has been suggested as an important predictor for recovery after aSAH [Citation52] and thus is important for health care professionals to be aware of when interacting with patients recovering after aSAH. It is also of importance in a long-term perspective since research has shown that 6 years after aSAH, informants still describe the changed life as forcing them to use new coping strategies to deal with everyday life [Citation33].

The informants expressed that the information from healthcare on what to expect when recovering from an aSAH was insufficient, which resulted in uncertainty. Lacking information has been found to be one of the most common unmet needs after an aSAH [Citation53], and the most requested information concerned issues on the aSAH itself [Citation54]. The results from an interview study by Persson et al. [Citation33] reveals that persons with aSAH who were discharged to home after the neurosurgical unit specifically lacked information about the course of the illness and possible cognitive consequences. Moreover, they also lacked follow-up appointments, resulting in a perception of being abandoned and that they had to manage their own recovery.

To strengthen the recovery after aSAH, we suggest a more person-centered approach in follow-ups and rehabilitation, to tailor care in a way that directly addresses the individual patient’s needs and preferences. Person-centered care implies (1) a view of partnership between the patient and clinicians (physicians and nurses), (2) to listen to the patient’s individual view of their condition and daily life in relation to it, and (3) to use shared decision making when formulating an individual care plan, including the patient’s resources, specific needs and to establish realistic goals. Further, to clarify what responsibility the patient and healthcare professionals have in different parts to achieve goal completion [Citation55].

Methodological considerations

The results in this study consolidate those from numerous quantitative studies, presenting data on functional outcome [Citation24,Citation25], physical and mental fatigue [Citation23,Citation26], affected cognition [Citation12,Citation56], psychological distress [Citation27,Citation57], affected social life and relationships [Citation28,Citation29,Citation58], and return to work [Citation30,Citation59]. This study adds to the literature by giving a deeper understanding of the process of trying to regain health and return to previous life after an aSAH, by describing patients’ perceptions and the meaning attached to them.

The interview data were rich, and saturation was achieved, with variation in descriptions. Moser and Korstjens [Citation41] emphasize that the most important criterion when assessing saturation is the availability of enough in-depth data showing patterns and variations in the phenomenon under study. In this study, the rich data were obtained due to having a maximum variation sample and quotes from all informants contributed to the study results.

All interviews were conducted by the same researcher, using a semi-structured interview guide, and within a limited time period, which strengthens the dependability [Citation44]. Reflexivity was considered by all authors throughout the process by acknowledging assumptions, preconceptions, and values and how these aspects might affect the research process [Citation60]. The authors’ preunderstandings are based on theoretical and practical knowledge gained from their professional experience as registered nurses and researchers within different areas of acute conditions as well as long-term illnesses (neurosurgery care, rheumatology care, heart and vascular care, and cancer care). The different forms of professional experience in the group were an asset that enriched the procedure of analyzing the transcripts, through a process of reflection and discussion [Citation44] and resulting in the presented subcategories and categories. The collaboration during the analysis process between all authors (investigator triangulation) [Citation60] further contributed to the study’s credibility.

To help the reader validate the trustworthiness of the results and address credibility and transferability, each subcategory is described with emerging patterns to enable assessment of external heterogeneity and internal homogeneity [Citation45], the results are synthesized and supported by citations [Citation60].

This study has some limitations that need to be mentioned. Only patients assessed to be GOS 4 or 5 were included, limiting the results to only include experiences of those who had a fairly good outcome. Informants assessed as GOS 3 at hospital discharge were invited but declined participation. Another limitation is that the interviews were conducted some years back, but the results are still considered relevant today since rehabilitation regimens and organizational structures are the same. We therefore suggest that the results are transferable to persons who have experienced an aSAH with a fairly good outcome and not restricted to Swedish context.

Conclusion

Contracting an aSAH was perceived as a life-changing event. The changes had an impact on the informants’ view of self and affected relationships with friends and significant others. They perceived new barriers in their living conditions, such as affected finances and feeling restricted due to driving cessation. The informants’ lacked information on what to expect when recovering from an aSAH, which resulted in uncertainty. Their expectations of recovery were at times unrealistic and were influenced by existential thoughts, comparisons with others, and expectations of significant others. Based on the findings, we suggest a person-centered approach in follow-ups and rehabilitation programs to strengthen the recovery after aSAH.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the informants in this study for their willingness to share their experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Krishnamurthi RV, Ikeda T, Feigin VL. Global, regional and country-specific burden of ischaemic stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage and subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Neuroepidemiology. 2020;54(2):171–179.

- Zacharia BE, Hickman ZL, Grobelny BT, et al. Epidemiology of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2010;21(2):221–233.

- Ziemba-Davis M, Bohnstedt BN, Payner TD, et al. Incidence, epidemiology, and treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in 12 midwest communities. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(5):1073–1082.

- Kissela BM, Khoury JC, Alwell K, et al. Age at stroke: temporal trends in stroke incidence in a large, biracial population. Neurology. 2012;79(17):1781–1787.

- von Vogelsang AC, Thelin EP, Hakim R, et al. Health-Related quality of life dynamics 2 years following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a prospective cohort study using EQ-5D. Neurosurgery. 2017;81(4):650–658.

- Nieuwkamp DJ, Setz LE, Algra A, et al. Changes in case fatality of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage overtime, according to age, sex, and region: a meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(7):635–642.

- Vries E, Boerboom W, Berg-Emons R, et al. Fatigue in relation to long-term participation outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage survivors. J Rehabil Med. 2021;53(4):jrm00173– 7.

- von Vogelsang AC, Forsberg C, Svensson M, et al. Patients experience high levels of anxiety 2 years following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2015;83(6):1090–1097.

- Ferro JM, Caeiro L, Santos C. Poststroke emotional and behavior impairment: a narrative review. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27(1):197–203.

- Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Langa KM, et al. Cognitive function and psychological well-being: findings from a population-based cohort. Age Ageing. 2008;37(6):685–689.

- Chahal N, Barker-Collo S, Feigin V. Cognitive and functional outcomes of 5-year subarachnoid haemorrhage survivors: comparison to matched healthy controls. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;37(1):31–38.

- Wong GKC, Lam SW, Ngai K, et al. Cognitive domain deficits in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage at 1year. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(9):1054–1058.

- Sörbo A, Eiving I, Löwhagen Hendén P, et al. Mental fatigue assessment may add information after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Brain Behav. 2019;9(7):e01303.

- Johansson B, Rönnbäck L. Evaluation of the mental fatigue scale and its relation to cognitive and emotional functioning after traumatic brain injury or stroke. Int J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;2(1):1–7.

- Bergbom I. The process of recovery from severe illness. Inj Surg Treat Austral - Asian J Cancer. 2010;9(3):181–193.

- Allvin R, Berg K, Idvall E, et al. Postoperative recovery: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57(5):552–558.

- Laferton JA, Kube T, Salzmann S, et al. Patients’ expectations regarding medical treatment: a critical review of concepts and their assessment. Front Psychol. 2017;8:233.

- Auer CJ, Glombiewski JA, Doering BK, et al. Patients’ expectations predict surgery outcomes: a meta-analysis. Intj Behav Med. 2016;23(1):49–62.

- World Health Organization and the World Bank. World report on disability. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2011. Available from: www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf

- Norrving B, Barrick J, Davalos A, et al. Action plan for stroke in Europe 2018–2030. Eur Stroke J. 2018;3(4):309–336.

- Jones F, Riazi A. Self-efficacy and self-management after stroke: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(10):797–810.

- Wottrich AW, Astrom K, Lofgren M. On parallel tracks: newly home from hospital-people with stroke describe their expectations. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(14):1218–1224.

- Buunk AM, Groen RJM, Wijbenga RA, et al. Mental versus physical fatigue after subarachnoid hemorrhage: differential associations with outcome. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(11):1313–e113.

- Custal C, Koehn J, Borutta M, et al. Beyond functional impairment: redefining favorable outcome in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;50(6):729–737.

- Gerner ST, Reichl J, Custal C, et al. Long-term complications and influence on outcome in patients surviving spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;49(3):307–315.

- Western E, Nordenmark TH, Sorteberg W, et al. Fatigue after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: clinical characteristics and associated factors in patients with good outcome. Front Behav Neurosci. 2021;15:633616.

- Tang WK, Wang L, Kwok Chu Wong G, et al. Depression after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review. J Stroke. 2020;22(1):11–28.

- Wermer MJH, Kool H, Albrecht KW, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage treated with clipping: long-term effects on employment, relationships, personality, and mood. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(1):91–97.

- Buunk AM, Groen RJ, Veenstra WS, et al. Leisure and social participation in patients 4–10 years after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Brain Inj. 2015;29(13–14):1589–1596.

- Turi ER, Conley Y, Crago E, et al. Psychosocial comorbidities related to return to work rates following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(1):205–211.

- Stienen MN, Visser-Meily JM, Schweizer TA, et al. Prioritization and timing of outcomes and endpoints after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in clinical trials and observational studies: proposal of a multidisciplinary research group. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30(1):102–113.

- Agius SJ. Qualitative research: its value and applicability. Psychiatrist. 2013;37(6):204–206.

- Persson HC, Tornbom K, Sunnerhagen KS, et al. Consequences and coping strategies six years after a subarachnoid hemorrhage - a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181006.

- Hedlund M, Zetterling M, Ronne-Engstrom E, et al. Perceived recovery after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage in individuals with or without depression. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(11–12):1578–1587.

- Berggren E, Sidenvall B, Muhli UH. Identity construction and meaning-making after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;6(2):86–93.

- Jarvis A. Recovering from subarachnoid haemorrhage: patients’ perspective. Br J Nurs. 2002;11(22):1430–1437.

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340.

- Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1(7905):480–484.

- Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):9–18.

- Eagles ME, Tso MK, Macdonald RL. Cognitive impairment, functional outcome, and delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2019;124:e558–e562.

- Graneheim UH, Lindgren BM, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;56:29–34.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2015.

- Johansson B, Rönnbäck L. Assessment and treatment of mental fatigue after a traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2017;27(7):1047–1055.

- Norrie J, Heitger M, Leathem J, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury and fatigue: a prospective longitudinal study. Brain Inj. 2010;24(13–14):1528–1538.

- Seule M, Oswald D, Muroi C, et al. Outcome, return to work and health-related costs after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2020;33(1):49–57.

- Stepney M, Kirkpatrick S, Locock L, et al. A licence to drive? Neurological illness, loss and disruption. Sociol Health Illn. 2018;40(7):1186–1199.

- Mårdh S, Mårdh P, Anund A. Driving restrictions post-stroke: physicians’ compliance with regulations. Traffic Inj Prev. 2017;18(5):477–480.

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH. Personal and contextual determinants of coping strategies. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(5):946–955.

- Ackermark PY, Schepers VP, Post MW, et al. Longitudinal course of depressive symptoms and anxiety after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(1):98–104.

- Boerboom W, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, van Kooten F, et al. Unmet needs, community integration and employment status four years after subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(6):529–534.

- Dulhanty LH, Hulme S, Vail A, et al. The self-reported needs of patients following subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(24):3450–3456.

- Wallström S, Ekman I. Person-centred care in clinical assessment. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17(7):576–579.

- Geraghty JR, Lara-Angulo MN, Spegar M, et al. Severe cognitive impairment in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: predictors and relationship to functional outcome. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(9):105027.

- Bartlett M, Bulters D, Hou R. Psychological distress after subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2021;148:110559.

- Kruisheer EM, Huenges Wajer IMC, Visser-Meily JMA, et al. Course of participation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26(5):1000–1006.

- Buunk AM, Spikman JM, Metzemaekers JDM, et al. Return to work after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the influence of cognitive deficits. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220972.

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120–124.