Abstract

Purpose: The objectives of this study were to determine the effects of hearing disability on employment rates; examine how various factors are associated with employment; and identify workplace accommodations available to persons with hearing disabilities in Canada.

Material and methods: A population-based analysis was done using the data collected through the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD), representing 6 million (n = 6 246 640) Canadians. A subset of the complete dataset was created focusing on individuals with a hearing disability (n = 1 334 520). Weighted descriptive and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed.

Results: In 2017, the employment rates for working-age adults with a hearing disability were 55%. Excellent general health status (OR: 3.37; 95% CI: 2.29–4.96) and daily use of the internet (OR: 2.70; 95% CI: 1.78–4.10) had the highest positive effect on the employment rates. The top three needed but least available accommodations were communication aids (16%), technical aids (19%), and accessible parking/elevator (21%).

Conclusion: Employment rates for persons with a hearing disability are lower than the general population in Canada. Employment outcomes are closely associated with one’s general health and digital skills. Lack of certain workplace accommodations may disadvantage individuals with a hearing disability in their employment.

People with severe hearing disabilities and those with additional disabilities may need additional and more rigorous services and supports to achieve competitive employment.

It is important for the government to improve efforts toward inclusive education and develop strategies that promote digital literacy for job seekers with hearing disabilities.

Officials concerned with implementing employment equity policies in Canada should focus on finding strategies that enable employees to have supportive conversations with their employers regarding disability disclosure and obtaining required accommodations.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Acquiring a disability affects an individual’s health directly and deteriorates other social determinants of health [Citation1]. Global reports and scientific evidence demonstrate that persons with disabilities face higher rates and severity of multidimensional poverty as measured through income, employment, assets, expenditures, and healthcare expenses [Citation2]. In comparison to people without disabilities, persons with disabilities face higher levels of material deprivation and face 1.9 times higher stress about having enough money to pay for basic needs [Citation3]. In addition, persons with disabilities face disparities in employment opportunities even after having similar education and need three times more income to experience an equivalent level of financial well-being [Citation4,Citation5]. A study found that disability has an immediate negative effect on employment and has the greatest detrimental influence on income over other social determinants of health [Citation1].

Hearing disability is one such example. Deafness and hearing impairment is now the fourth largest contributors to the number of years lived with a disability worldwide [Citation6,Citation7]. The World Report on Hearing, published recently by the World Health Organization (WHO), reports that globally around 1.5 billion people live with some form of hearing loss [Citation8,Citation9]. Among them, over 400 million (>5% of the world’s population, 1 in 5 people in the world) have severe to profound hearing impairment [Citation7,Citation9]. This number is projected to increase rapidly and change to 1 in 4 by 2050 [Citation9]. The economic impact of hearing loss is prohibitive, and countries incur between USD 1.8 and 194 billion on direct medical expenditures and indirect costs due to lost productivity and income [Citation10]. In addition, a recent systematic review found that sensory loss, including hearing and vision loss, was the largest contributor to the need for rehabilitation in children under 15 and older adults above 65 years [Citation11].

At the level of the individual, hearing impairment has negative consequences on one’s physical, mental, and psychosocial health and well-being [Citation12]. Communication difficulties due to hearing loss generate a cascade of adverse effects on individuals’ quality of life – from social isolation, loneliness, depression, and stress to cognitive decline [Citation13–16]. In addition, hearing loss is associated with lower educational attainment and workforce participation among affected individuals [Citation17,Citation18]. A systematic review examining the association between hearing loss and employment found that, after controlling for age, sex and education, people with adult-onset hearing loss were still more likely to be unemployed than individuals without hearing loss [Citation7].

Studies from the USA have reported a gap of 20% in wage earnings and nearly double the likelihood of unemployment and underemployment for individuals with hearing impairment, even after adjusting for education and other demographic determinants [Citation19,Citation20]. A study using a cross-sectional survey of 630 000 individuals in Australia with self-reported hearing loss reported that unemployment rates ranged between 11.3% and 16.6%, while full-time employment rates ranged between 48.3% and 52.7% [Citation21]. These rates varied depending on the age of onset (at birth or childhood versus adulthood), cause of hearing impairment (congenital versus acquired or induced), and degree or severity of the hearing impairment. Similar trends have been reported in studies from the UK, Spain, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and the Netherlands, where employment rates for individuals with hearing impairment were found significantly less than those for hearing individuals [Citation22–27].

Challenges in gaining employment cannot be fully attributed to the individuals’ hearing loss alone. In fact, these challenges stem from a combination of barriers faced by individuals due to discrimination and a lack of available support [Citation9,Citation18]. Numerous studies have reported wage disparities between those with and without hearing loss and issues related to employment discrimination, lack of accessibility and inadequate accommodations [Citation18,Citation25,Citation28–30]. Researchers examining workforce participation experiences of people who are D/deaf or hard of hearing found that they were less likely to be employed in high-status occupations and earn comparable wages despite having the required experience and qualifications [Citation31,Citation32]. Studies further highlight that negative attitudes and discriminatory practices at the workplace lead to lower job satisfaction and put deaf or hard-of-hearing individuals at risk of developing psychosocial problems and dropping out of work eventually [Citation33,Citation34]. Women with hearing loss have been found to be facing a double disadvantage. Though the prevalence of hearing impairment is high among men, employment inequity is reported to be higher among women, with an increased need for having sick leaves, disability pensions and sickness benefits [Citation22,Citation24,Citation27].

Employment support for persons with disabilities in Canada is provided through a variety of federal and provincial programs, governed through several acts and protective legislations. At the federal level, some of the major programs include opportunities funds, workforce development agreements and labour market development agreements governed by the Canadian Human Rights Act, Employment Equity Act, and Canada Labour Code. These programs support a wide range of services for persons with disabilities including job search, employability services, wage subsidies, work placements and employer awareness initiatives to encourage employers to hire persons with disabilities. In addition, the federal government also provides certain tax credits, cash transfers, and tax-advantaged saving plans to enhance the financial security of persons with disability [Citation35].

Similarly, the provincial government under the mandate of the human rights code and employment and accessibility legislation provides several employment benefits and support measures for persons with disabilities. These include education, training, counselling, job assistance services, targeted wage subsidies, and skills development opportunities [Citation35]. Though the programs, their funding and individuals’ eligibility vary from province to province. There are also funding streams for the employment service providers and national disability organizations to increase the social inclusion of persons with disabilities in Canadian society. Despite the wide range of programs and services, the employment rates of persons with disabilities in Canada remain significantly lower than that of the general population. In recognition of this fact, the Employment and Social Development Canada commits to finalize and release a Disability Inclusion Action Plan to improve financial security and create a robust employment strategy for persons with disabilities as per the federal budget for the year 2022 [Citation36].

To inform Canada’s first disability inclusion action plan, robust evidence is needed. Although many studies have examined the relationship between hearing loss and employment in other countries, no empirical studies have been conducted recently in Canada to examine access to meaningful employment for people with hearing disabilities. The latest available estimates come from the Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD) in 2012, which reported that 48% of people who self-identified themselves with a hearing disability (aged 15–64) were employed while 44% were not in the labour force and 8% were unemployed [Citation37]. Other than the CSD, the Canadian Association of the Deaf (CAD) conducted a survey in 1998, which found that only 21% of self-identified D/deaf Canadians were then employed while 37.5% were unemployed and 42% were underemployed [Citation38]. The CAD estimates are dated. However, in a recent report, CAD quotes that individuals with hearing disabilities continue to face employer discrimination in the form of misconceptions about their skills and abilities, lack of provision of sign language interpreters for interviews and training; and the reluctance of managers to provide accommodations that lead to chronic underemployment and economic disadvantage for affected individuals [Citation38]. Apart from the CAD report, only a few studies have examined the employment barriers faced by people with hearing disabilities in Canada, of which all are either small-scale or have derived their findings from the data collected almost two decades ago [Citation39,Citation40].

Therefore, the objectives of our study were to determine the effects of hearing disability on employment, examine how various factors such as a person’s age, gender, and education are associated with employment and identify workplace accommodations that are needed and available to persons with hearing disability in Canada. An analysis using nationally representative data provides strong leverage for improving current policy emphasis – specifically accessibility legislation and human rights declarations for people with hearing disabilities in Canada.

Methods

A cross-sectional population-based analysis was conducted using the data collected by Statistics Canada in 2017 through the Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD) [Citation41]. The ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the institutional review board of Université de Montréal (#2020-164 CERC-20-057-D). We also obtained approval from the joint adjudication committee of Statistics Canada that reserves the copyright of the census and CSD data. After gaining approvals, master files for CSD data were accessed in the Statistics Canada Research Data Centre located at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. All the data were fully anonymized.

The CSD is conducted every five years and includes Canadians who are above 15 years of age and living anywhere within the 10 Canadian provinces or three territories [Citation42]. The CSD collects data on disability and its effect on various life aspects from the Canadians who experience functional limitations. It captures information on specific medical diagnoses and classifies those as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes developed by the World Health Organization [Citation43]. Further, using the disability screening questionnaire (DSQ), the CSD identifies individuals with one or more of these ten disability types- hearing, vision, mobility, flexibility, dexterity, pain, learning, mental health, memory, and developmental disabilities.

The CSD defines disability based on the social model approach and takes a person’s subjective assessment of the impact of health conditions on their daily activities into account [Citation42]. A disability severity score is generated based on two criteria and assigned to each individual. The first is based on the intensity of activity limitations, and the second is based on the frequency of activity limitations. The first criteria measure the degree to which difficulties are experienced across various domains of functioning, while the second measures how often daily activities are limited by these difficulties. A final global score is created by adding individual scores on all ten disability types.

The CSD questionnaire contains various modules to collect specific information on an individual’s disability-related characteristics such as severity and age of onset of the disability and its impact on an individual’s various life domains. Various life domains covered by the CSD include educational attainment and experiences; labour force status and details; access to government services; use of, and unmet needs for, health services; use of, and unmet needs for, aids and assistive devices; general health status; housebound status; and internet use. All data are collected either using a secure online questionnaire or through a telephone interview, depending on each participant’s preference.

The sampling frame for the 2017 CSD consisted of individuals who completed the 2016 census. The sample for the census is drawn using a two-stage stratified sampling technique. Stage 1 involves a stratified sample of one in four households occupying a private dwelling in most Canadian regions and all households in remote areas and on First Nations reserves. The second phase involves a sample for the CSD selected from the individuals who reported having difficulty in response to the sub-questions about activities of daily living on the long-form census questionnaire. This sample excludes people living on First Nations reserves and those under the age of 15 as of May 10, 2016.

The response rate on the 2017 CSD was 70%, corresponding to 50 000 individuals and representing more than 6 million (n = 6 246 640) Canadians. More information on sampling and data collection within CSD can be found on the Statistics Canada website within the CSD concepts and methods guide [Citation42]. The exact wording and sequence of questions are also available directly from Statistics Canada (2017).

Study population and analysis

To reach our study objectives, we selected a subset of the individuals from the larger CSD dataset who reported having a hearing disability with or without other types of disabilities. Within the CSD, persons with a hearing disability were identified using two questions on the survey. The first question asked about the level of difficulty a person has in hearing (even with a hearing aid or cochlear implant), and for those who reported some difficulty hearing, a second question asked how often this difficulty limited their daily activities. Persons who reported “some” difficulty hearing but “rarely” being limited in their daily activities were not identified as having a hearing disability. The variables that were included in our analysis comprised demographic attributes (i.e., age, sex, province, education) and disability-related characteristics of our study population (i.e., age of onset of disability, the severity of a disability, number of types of disabilities, number and types of aids or assistive devices used, use of other aids). Individuals’ employment details such as employment status, personal income, sources of income, employment accommodations, and labour force discrimination were also analyzed using descriptive statistics and reported as counts and proportions. Each survey respondent on the CSD is assigned a weight equivalent to the number of people they represent in the larger population, and therefore all estimates were provided in weighted numbers. Please note that data with low numbers (less than 10) or large standard errors (high variability among the samples) were not released due to unreliable estimates and hence are not reported here.

Multivariate logistic regression was built to identify predictors associated with positive employment outcomes for working-age adults (25–64 years) with a hearing disability, which was further stratified by sex. The outcome variable for logistic regression was employment status divided into binary categories – i) employed either full- or part-time; ii) unemployed and out of labour force. The independent variables included in the logistic models comprised sex, age of onset of disability, the severity of a disability, number of types of disabilities, education, number of aids or assistive devices used, provincial region, frequency of internet use, housebound status, general health status, mental health status and life satisfaction. These variables have been shown to be associated with employment among individuals with hearing loss in prior studies and were available in the CSD dataset.

The regression model was built using backward elimination and was checked for its robustness using the likelihood ratio test. We also checked confounding and multicollinearity among variables and used appropriate strategies to control for that. Crude and adjusted odds ratio and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were computed, and a p-value < .05 was considered statistically significant. The overall model accuracy was evaluated using goodness-of-fit statistics – Hosmer and Lemeshow test of significance. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Demographic profile

Of all individuals represented by the CSD respondents, around 1.3 million (n = 1 334 520) Canadians reported having a hearing disability, constituting 21% of all people with disabilities in Canada and 4.76% of the total Canadian population (15 years and above) in 2017 (). At the time of the survey, most of the individuals with a hearing disability were living in Ontario (42%), followed by British Columbia (17%) and Quebec (14%). The average age of people with hearing disabilities was 64 years (SD: 16.85). Almost 50% were above 65 years of age, 47% were between 25 and 64 years, and the rest 3% were between 15 and 24 years of age. Around 54% were males, and 46% were females. With regards to disability parameters, 80% of individuals had mild to moderate, while 20% indicated a severe hearing disability. For more than 37% of individuals, hearing difficulty began between 45 and 65 years of age. Another 25% reported onset in early adulthood between 15 and 44 years of age, and another 25% reported onset in older adulthood after 65 years. For the rest 12%, hearing difficulty began at birth or before 15 years.

Table 1. Demographic, education, and employment profile of persons with hearing disability in Canada, 2017 (N = 1 334 520).

Education and employment

With regards to the educational attainment of individuals with hearing disabilities, almost half (50%) had a high school diploma/certificate or less, followed by 29% with a trade certificate or college diploma and 21% with a university degree. A small proportion of individuals (3%) were attending high school/college/university in 2017.

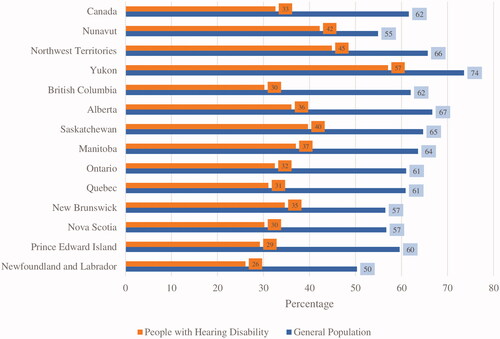

Regarding the employment status of individuals with hearing disabilities in 2017, around a third (32%) were employed while 64% were out of the labour force and 3% were unemployed. Of those who reported being employed, 80% were in full-time employment while 20% were in part-time employment. More than half (56%) of the individuals had non-employment income only, while for 20% of the individuals, employment was the source of income. Almost 17% had income coming from both employment and non-employment sources, while 6.7% of individuals had no income at all. Around 18% of the employed individuals belonged to the category of ‘professionals’ under the National Occupational Code (NOC) groupings of Canada. Other common employment categories for individuals with a hearing disability included sales and service (13%) and semi-skilled manual work (13%). The employment rates were highest in Yukon (57%), Nunavut (42%), and Northwest territories (44%), while lowest in Newfoundland and Labrador (26%) and Prince Edward Island (29%) ().

Factors affecting employment

To identify factors related to employment among individuals with hearing disabilities in Canada, we conducted several bivariate and multivariate analyses. The bivariate trends suggested that there was a significant difference in the employment rates between males and females: 38% of males were employed in comparison to 26% of females (OR: 1.78; 95% CI: 1.76–1.79). Furthermore, age >65 years, being an ethnic minority, later onset of hearing disability, a more severe hearing disability, using a higher number of aids, a greater number of types of disabilities, and a positive housebound status were associated with lower employment rates (see for the strength of these associations). Education above high school, daily use of the internet, a good or excellent general health and mental health status, and higher life satisfaction were positively related to employment. People residing in the Atlantic provinces had the lowest employment rates, while those living in northern Canada had the highest employment rates ().

Table 2. Employment profile of persons with hearing disability in Canada, 2017 (N = 1 334 520).

We further built a multivariate model to identify predictors of employment for working-age adults (25–64 years) with hearing disabilities, and for males and females separately within this age group. The variables that were significantly associated with employment after controlling for each other included sex, the severity of hearing disability, age of onset of hearing disability, number of types of disabilities, education attainment, internet use frequency and general health status. The provincial region, housebound status, number of aids, life satisfaction, and ethnicity were not significantly related to employment in multivariable analysis.

Of all the variables, general health status and frequency of internet users had the highest positive effect size, while a number of types of disabilities had the highest negative effect size in the model. Individuals with general health status between excellent to good had the highest odds of being employed (OR: 3.37; 95% CI: 2.29–4.96) compared to those with less than good health status. Individuals who used the internet every day had the highest odds of employment in comparison to those who use the internet sometimes or never (OR: 2.70; 95% CI: 1.78–4.10). Individuals with a greater number of types of disabilities had lower odds of employment (OR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.73–0.82) in comparison to those with hearing disabilities only. Similar trends were found in the females-only model except that the effect of severity of hearing disability and having more number of disabilities was more pronounced in females in comparison to males. In the males-only model, the severity of hearing disability was not significantly associated with employment after controlling for other factors, which included age of onset, number of types of disabilities, educational attainment, internet use frequency and general health status ().

Table 3. Logistic regression model for predictors of employment for adults with hearing disability in Canada, 2017 (N = 631 040).

Workplace accommodations and labour force discrimination

From the individuals who were employed at the time of the survey (N = 434 770), CSD asked about the workplace accommodations. The top three employment accommodations that were needed and available included: modified work hours (32%), modified or different duties (29%) and special chair/back support (20%). The top three needed but least available accommodations were communication aids (16%), technical aids (19%), and accessible parking/elevator (21%) (). When asked about the labour force discrimination, around 38% of individuals with a hearing disability who were employed said that they were disadvantaged in their employment due to their condition. Almost 10% were refused a promotion, and a job due to their condition and around 7.65% were refused a job interview in the past five years.

Table 4. Needed and available workplace accommodations for individuals with hearing disability (N = 434 770).

Discussion

This study explored the employment rates for people with hearing disabilities using the Canadian Survey on Disability 2017 and studied how various demographic, health and social factors affected this phenomenon. The first important finding of our study was that 33% of individuals with hearing disabilities in Canada were employed in 2017 (). For working-age adults (25–64 years), employment rates were higher at 55%, though these rates were lower than the employment rates for the general population, which was around 80% in 2017 [Citation44]. The employment rates found for people with hearing disabilities within the working-age group in Canada were close to what has been reported in the USA (53% in the USA vs 55% in Canada) [Citation45] but slightly higher than what has been reported in the UK (47% in the UK vs 55% in Canada) [Citation46]. The average age of Canadians with hearing disabilities was 64 years, which implies hearing disability is mostly age-related in Canada, and this can be partially attributed to the lower employment rates. However, there still existed a wide gap in employment rates for people with and without hearing disabilities within the working-age group.

Figure 1. Employment rates of general population and people with hearing disability in 2017. Notes: The employment rate is the number of persons employed expressed as a percentage of the population 15 years of age and over. The employment rate for a particular group (individuals with hearing disability) is the number employed in that group expressed as a percentage of the population for that group. Estimates are percentages, rounded to the nearest tenth. All rates in the charts/tables are calculated excluding non-response categories ("refusal," "don't know," and "not stated") in the denominator.

Another important finding of this study was that poor general, and psychosocial health was significantly associated with negative employment outcomes among working-age adults with hearing disabilities in Canada. Previous research shows that hearing loss negatively impacts the psychosocial health and well-being of individuals in the form of depression, anxiety, frustration, loneliness, withdrawal, and stress due to their inability to participate in several daily and social activities [Citation47]. With regards to work, the hearing loss puts a strain on an individual’s work ability and professional relationships as they feel restricted to participate in several aspects of work-life, including taking part in meetings, contributing to discussions, interacting with colleagues, and participating in training or other professional activities. Further, they may feel embarrassed about the disclosure of their hearing loss and find themselves uncomfortable while asking for support from their peers and supervisors [Citation40,Citation48]. These facts support our findings and suggest that hearing disability has a profound impact on the psychosocial health of individuals, which, in turn, affects their employment outcomes. In addition to general health, a set of impairment-related factors affected employment outcomes for people with hearing disabilities. These factors can also be referred to as non-modifiable factors, including severity and age of onset of the hearing disability, and presence of other types of disabilities. Studies have reported similar findings related to the impact of severity of hearing disability and secondary disabilities on employment [Citation27].

Other important factors that had a significant impact on employment for people with hearing disability was educational attainment and age of onset. Many studies conducted across different parts of the world have identified the role of education in determining the employment outcomes for adults with disabilities in general as well as for those with hearing conditions [Citation26,Citation40,Citation49–51]. Hearing loss, depending on its age of onset, affects speech recognition and the development of language skills in children, which in turn have an impact on their academic performance and advancement [Citation52]. Poor language skills at an early age then bear a trickle-down effect on individuals’ ability to compete in the job market during adulthood [Citation53]. Additionally, children with hearing loss experience barriers to mainstream education mostly related to the absence of accessible curriculum and sign language training, stigma towards the use of aids, and bullying [Citation54–56]. The World Federation of Deaf estimates that 80% of the 34 million children with disabling hearing impairment living worldwide do not have access to education, and the remaining who do face several barriers mentioned above [Citation57]. These findings emphasize the importance of inclusive education for children and youth with hearing disabilities with a specific focus on improving access to multilingual curriculum, availability, and training on the use of assistive technologies, and promoting a supportive and respectful environment.

The frequency of internet use was another important element that had a positive impact on employment for adults with hearing disabilities in Canada. An apparent explanation behind this finding could be digital skills are indispensable for most individuals in the modern world and enable them to succeed in the work environment [Citation58,Citation59]. Another possibility is that most jobs are advertised online first and people with internet skills would have timely access to those opportunities. Specific to individuals with hearing disabilities, research has shown that the internet creates a special opportunity because of its invisibility, textuality, availability, and multimodality [Citation60,Citation61]. These features not only enhance the communication power of individuals with hearing loss but also relieves them of negative attitudes and stereotypical responses that are generated in non-virtual environments where the impairment becomes evident. Further, it is suggested that there is a positive relationship between internet use and psychosocial health, well-being, quality of life, and self-efficacy for individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing [Citation61,Citation62]. These findings explain why individuals with a hearing disability who used the internet daily had a higher likelihood of being employed in comparison to those who did not use the internet in our sample.

This study supplements the findings from a parallel study where we explored the employment rates of people with seeing disabilities in Canada and the factors associated [Citation63]. Less severe disability, education above high school, and daily use of the internet were positively related to the employment of adults with seeing disabilities, which is also the case with hearing disabilities. However, the use of assistive aids and devices, which was a predominant factor negatively associated with the employment of adults with seeing disabilities, did not play a role in determining the employment outcomes for individuals with hearing disabilities.

With regards to the workplace accommodations, our findings suggested that specific accommodations such as communication and technical aids were not commonly provided and more than a third of adults with hearing disabilities reported facing labour-force discrimination, which prevented them from advancing in their careers. A study by Laynes and Lindon (2012) reported similar results that individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing consider workplace accommodations significant in completing their jobs yet reported dissatisfaction with the accommodations provided to them [Citation64]. There are several biopsychosocial factors that mediate the process and outcomes of workplace accommodations [Citation65,Citation66]. Studies report that very often, individuals with a disability, specifically those with invisible disabilities, are reluctant to request accommodations due to social stigma, low self-efficacy, low self-perceived usefulness of accommodations, lack of social support, or poor knowledge about the laws and processes [Citation65–67]. However, individuals who do ask for accommodations report higher levels of job satisfaction and job performance [Citation65]. Therefore, strategies are needed that enable employees with disabilities to have supportive conversations with their employers regarding disability disclosure and obtain required accommodations and achieve desired work-related outcomes.

An interesting finding to note here is that 21% of the participants needed an accessible parking/elevator, which was not available in their workplace. This could mean that despite having accessible building codes statutes and standards in place, accessible parking/elevator is not a reality across provincial jurisdictions in Canada [Citation68]. Another noteworthy finding is about the employment accommodation of special chair/back support (20%) that was needed and was available. This could be because individuals with disabilities often have comorbidities that require accommodation that is not obvious with respect to their hearing impairment.

Overall, this study suggested that employment rates for persons with a hearing disability are lower than the general population in Canada. Evidence is emerging that hiring persons with disabilities promotes wider workforce diversity and provides economic benefits for companies by fostering a positive reputation among clients, business partners and society, increased innovation, and staff loyalty and commitment [Citation69–71]. Bonaccio and colleagues (2019) provided evidence-based answers to the most important concerns expressed by hiring managers to break myths with regard to employing people with disabilities [Citation72]. Specific to workers with hearing loss, studies have found that employees with hearing impairment were productive with excellent work habits and added value to the company by enhancing their image of caring and inclusivity [Citation73,Citation74]. Therefore, we hope that our study findings will provide strong leverage for improving current efforts regarding improving employment equity for people with hearing disabilities in Canada.

Future research

Although this was not explored in our study, the impact of hearing loss on psychosocial health can be differential in different age groups. While hearing loss is a common part of the aging process, it is not as prevalent in younger age groups [Citation33]. It would therefore be important in future studies to identify and address the psychosocial impacts of hearing loss across different age groups in a specific manner to support employment efforts for people with hearing disabilities accordingly. Given the recent policy emphasis on improving accessibility and inclusion of diverse groups in Canada, future research should examine the effectiveness of accessibility and employment equity policies that aim to promote labour force participation for disadvantaged groups, including those with hearing disabilities. Another key direction to advance this employment research in the field of sensory disabilities could be exploring the employment rates for Canadians with concurrent hearing and seeing disabilities (also referred to as deafblindness) using the CSD data. A 2018 global report on the situation of persons with deafblindness reveals that people with deafblindness experience barriers to employment and are at risk of exclusion from the Sustainable Developmental Goals implementation [Citation75]. A Canadian stakeholder consultation report in 2019 reported the prevalence estimates obtained from the CSD 2017 and suggested that around 1.66% of the Canadian population above 15 years of age has deafblindness and that individuals with deafblindness continue to experience limited access to employment opportunities in Canada [Citation76].

Lastly, as most of the current research in this area is cross-sectional and survey-based in nature, more research is needed that is qualitative and longitudinal in nature. Qualitative studies can add valuable insights towards understanding the barriers faced by and needs and supports required by employment-seeking individuals with hearing disabilities. Similarly, longitudinal research will be valuable in deepening our understanding of the most important personal and external predictors that lead to positive employment outcomes for individuals with hearing disabilities.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations which must be considered while interpreting the findings. Our results are based on the analysis of the CSD, which is a cross-sectional survey; therefore, causal relationships could not be established between various factors that were found to be associated with employment outcomes for people with hearing disabilities in Canada. Similarly, as the data were collected on a particular date in 2017, some individual characteristics might have changed, which are not known to us. The sample for the CSD is drawn from the Census respondents and does not include every person who might have had a disability and specifically excludes those living in the institutions, collective dwellings or on First Nations reserves. Therefore, the estimates are subjected to a sampling variation and/or underestimation. Also, the findings are based on self-reported data and hence are subjected to several individual biases and response biases. Lastly, our analyses only included variables that were available in the research data centres for the CSD data. There could be other factors that are linked to employment outcomes of people with hearing disabilities that were not included in this study.

Conclusion

The employment rates for individuals with a hearing disability are lower compared to the general population in Canada. These outcomes are closely associated with the demographic and disability-related factors and one’s physical, mental, and psychosocial health and well-being. The severity of disability and having more than one type of disability impede positive employment outcomes while better health, higher education, and daily use of the internet boost this phenomenon. Further, there was a lack of certain workplace accommodations when there was a need, which included both specific accommodations required for hearing loss as well as those for other additional health conditions. These findings have important implications for service organizations and policymakers.

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by a Reseau Vision – National and International Networking grant 2020, provided to Walter Wittich. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors also acknowledge the support received from the Queen’s Research Data Centre for providing access to the Statistics Canada data to conduct this project work.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Data availability statement

Data used in this study contain potentially sensitive information, and therefore, are restricted to be released by Statistics Canada. Data access request can be made at the Research Data Centres of Statistics Canada (Queen's University Research Data Centre in this case – [email protected]) via research analysts at the designated institutions. Please note that data will be only available to researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Frier A, Barnett F, Devine S, et al. Understanding disability and the 'social determinants of health': how does disability affect peoples' social determinants of health? Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(5):538–547.

- Pinilla-Roncancio M, Alkire S. How poor are People with Disabilities around the Globe? A Multidimensional Perspective. 2017. Available from: www.ophi.org.uk.

- Smith DL. Disability, employment and stress regarding ability to pay for housing and healthy food. Work. 2013;45(4):449–463.

- Kennedy J, Wood EG, Frieden L. Disparities in insurance coverage, health services use, and access following implementation of the affordable care act: a comparison of disabled and nondisabled working-age adults. Inquiry. 2017;54:46958017734031.

- Mitra S, Palmer M, Kim H, et al. Extra costs of living with a disability: a review and agenda for research. Disabil Health J. 2017;10(4):475–484.

- Graydon K, Waterworth C, Miller H, et al. Global burden of hearing impairment and ear disease. J Laryngol Otol. 2019;133(1):18–25.

- Shan A, Ting JS, Price C, et al. Hearing loss and employment: a systematic review of the association between hearing loss and employment among adults. J Laryngol Otol. 2020;134(5):387–397.

- Haile LM, Kamenov K, Briant PS, et al. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990-2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):996–1009.

- World Health Organization. World Report on Hearing. World Health Organisation. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-report-on-hearing

- Huddle MG, Goman AM, Kernizan FC, et al. The economic impact of adult hearing loss: a systematic review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(10):1040–1048.

- Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, et al. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the global burden of disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2021;396(10267):2006–2017.

- Chapman M, Dammeyer J. The significance of deaf identity for psychological well-being. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2017;22(2):187–194.

- Uchida Y, Sugiura S, Nishita Y, et al. Age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline – the potential mechanisms linking the two. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019;46(1):1–9.

- Thomson RS, Auduong P, Miller AT, et al. Hearing loss as a risk factor for dementia: a systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2017;2(2):69–79.

- Shukla A, Harper M, Pedersen E, et al. Hearing loss, loneliness, and social isolation: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162(5):622–633.

- Cosh S, Helmer C, Delcourt C, et al. Depression in elderly patients with hearing loss: current perspectives. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1471–1480.

- Jung D, Bhattacharyya N. Association of hearing loss with decreased employment and income among adults in the United States. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121(12):771–775.

- Punch R. Employment and adults who are deaf or hard of hearing: current status and experiences of barriers, accommodations, and stress in the workplace. Am Ann Deaf. 2016;161(3):384–397.

- Emmett SD, Francis HW. The socioeconomic impact of hearing loss in U.S. Adults. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(3):545–550.

- Walter GG, Dirmyer R. The effect of education on the occupational status of deaf and hard of hearing 26-to-64-year-olds. Am Ann Deaf. 2013;158(1):41–49.

- Hogan A, O'Loughlin K, Davis A, et al. Hearing loss and paid employment: Australian population survey findings. Int J Audiol. 2009;48(3):117–122.

- Dammeyer J, Crowe K, Marschark M, et al. Work and employment characteristics of deaf and hard-of-hearing adults. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2019;24(4):386–395.

- Nachtegaal J, Kuik DJ, Anema JR, et al. Hearing status, need for recovery after work, and psychosocial work characteristics: results from an internet-based national survey on hearing. Int J Audiol. 2009;48(10):684–691.

- Pierre PV, Fridberger A, Wikman A, et al. Self-reported hearing difficulties, main income sources, and socio-economic status; a cross-sectional population-based study in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):874.

- Kim EJ, Byrne B, Parish SL. Deaf people and economic well-being: findings from the life opportunities survey. Disabil Soc. 2018;33(3):374–391.

- Garramiola-Bilbao I, Rodríguez-Álvarez A. Linking hearing impairment, employment and education. Public Health. 2016;141:130–135.

- Svinndal EV, Solheim J, Rise MB, et al. Hearing loss and work participation: a cross-sectional study in Norway. Int J Audiol. 2018;57(9):646–656.

- Harris J, Bamford C. The uphill struggle: services for deaf and hard of hearing people – issues of equality, participation and access. Disabil Soc. 2001;16(7):969–979.

- O’Connell N. Opportunity blocked”: deaf people, employment and the sociology of audism. Humanity Soc. 2021;46(2):336–358.

- Perkins-Dock Ph.D R, Battle MT, Edgerton MJ, et al. A survey of barriers to employment for individuals who are deaf. Jadara. 2015;49(2):3.

- Samosh D. The three-legged stool: synthesizing and extending our understanding of the career advancement facilitators of persons with disabilities in leadership positions. Bus Soc. 2021;60(7):1773–1810.

- Kim SY, Min C, Yoo DM, et al. Hearing impairment increases economic inequality. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;14(3):278–286.

- Nachtegaal J, Festen JM, Kramer SE. Hearing ability and its relationship with psychosocial health, work-related variables, and health care use: the national longitudinal study on hearing. Audiol Res. 2011;1(1):28–33.

- Stokar H, Orwat J. Hearing managers of deaf workers: a phenomenological investigation in the restaurant industry. Am Ann Deaf. 2018;163(1):13–34.

- Prince MJ. Inclusive employment for Canadians with disabilities. Inst Res Public Policy. 2016;60(60):1–23.

- Trudeau J. Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion Mandate Letter. Office of the Prime Minister of Canada; 2021. [cited 2022 May 3]. p. 1–7. Available from: https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2021/12/16/minister-employment-workforce-development-and-disability-inclusion

- Bizier C, Contreras R, Walpole A. Hearing disabilities among Canadians aged 15 years and older, 2012. Can Surv Disabil. 2016;(89):1–67.

- Russell D, Chovaz C, Boudreault P. Administration of justice: the experiences of deaf, deafblind, and deaf people with additional disabilities in accessing the justice system. 2018;27(3):113–120.

- Murray JB, Klinger L, McKinnon CC. The deaf: an exploration of their participation in community life. OTJR Occup Particip Heal. 2007;27(3):113–120.

- Southall K, Jennings MB, Gagné JP. Factors that influence disclosure of hearing loss in the workplace. Int J Audiol. 2011;50(10):699–707.

- Woodcock K, Pole JD. Educational attainment, labour force status and injury: a comparison of Canadians with and without deafness and hearing loss. Int J Rehabil Res. 2008;31(4):297–304.

- Statistics Canada. Canadian survey on disability, 2012: concepts and methods guide; 2018. p. 1–69. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2014001-eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. ICD-10 Version: 2010. 2010.

- Morris S, Fawcett G, Brisebois L, et al. A demographic, employment and income profile of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over, 2017. Statistics Canada; 2018. Available from: www.statcan.gc.ca

- Lou GC, Cawthon S, Bond M. Deaf people and employment in the United States. National Deaf Center of Postsecondary Outcomes; 2019. Available from: https://www.nationaldeafcenter.org/sites/default/files/DeafEmploymentReport_final.pdf

- Bate A, Powell A, Pyper D, et al. Deafness and hearing loss. Westminster: Parliament of UK; House of Commons Library; 2017.

- Bigelow RT, Bigelow RT, Reed NS, et al. Association of hearing loss with psychological distress and utilization of mental health services among adults in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2010986–12.

- Heffernan E, Coulson NS, Henshaw H, et al. Understanding the psychosocial experiences of adults with mild-moderate hearing loss: an application of Leventhal’s self-regulatory model. Int J Audiol. 2016;55(sup3):S3–S12.

- Whittenburg HN, Cimera RE, Thoma CA. Comparing employment outcomes of young adults with autism: does postsecondary educational experience matter? J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2019;32(2):159–172.

- Southward JD, Kyzar K. Predictors of competitive employment for students with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. Educ Train Autism Dev Disabil. 2017;52(1):26–37.

- Madaus JW, Zhao J, Ruban L. Employment satisfaction of university graduates with learning disabilities. Remedial Spec Educ. 2008;29(6):323–332.

- Leclair KL, Saunders JE. Meeting the educational needs of children with hearing loss. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(10):722–724.

- Idstad M, Engdahl B. Childhood sensorineural hearing loss and educational attainment in adulthood: results from the HUNT study. Ear Hear. 2019;40(6):1359–1367.

- Hadjikakou K, Papas P. Bullying and cyberbullying and deaf and hard of hearing children: a review of the literature. Int J Ment Heal Deaf. 2012;2(1):18–32.

- Murray JJ, Hall WC, Snoddon K. Education and health of children with hearing loss: the necessity of signed languages. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(10):711–716.

- Olsson S, Dag M, Kullberg C. Deaf and hard-of-hearing adolescents’ experiences of inclusion and exclusion in mainstream and special schools in Sweden. Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2018;33(4):495–509.

- Murray JJ, Kraus K, Down E, et al. World Federation of the Deaf position paper on the language rights of deaf children. 2016. Available from: https://2tdzpf2t7hxmggqhq3njno1y-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WFD-Position-Paper-on-Language-Rights-of-Deaf-Children-7-Sept-2016.pdf

- Leahy D, Wilson D. Digital skills for employment. IFIP Adv Inf Commun Technol. 2014;444:178–189.

- van Laar E, van Deursen AJAM, van Dijk JAGM, et al. Measuring the levels of 21st-century digital skills among professionals working within the creative industries: a performance-based approach. Poetics. 2020;81(December 2019):101434.

- Maiorana-Basas M, Pagliaro CM. Technology use among adults who are deaf and hard of hearing: a national survey. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2014;19(3):400–410.

- Barak A, Sadovsky Y. Internet use and personal empowerment of hearing-impaired adolescents. Comput Human Behav. 2008;24(5):1802–1815.

- Soetan AK, Onojah AO, Alaka TB, et al. Hearing impaired students’ self-efficacy on the utilization of assistive technology in federal college of education (special) Oyo. IJCDSE. 2020;11(1):4245–4252.

- Gupta S, Sukhai M, Wittich W. Employment outcomes and experiences of people with seeing disability in Canada: an analysis of the Canadian survey on disability 2017. PLOS One. 2021;16(11):e0260160.

- Haynes S, Linden M. Workplace accommodations and unmet needs specific to individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(5):408–415.

- Dong S, Guerette AR. Workplace accommodations, job performance and job satisfaction among individuals with sensory disabilities. Aust J Rehabil Couns. 2013;19(1):1–20.

- Shahin S, Reitzel M, Di Rezze B, et al. Environmental factors that impact the workplace participation of transition-aged young adults with brain-based disabilities: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2378–2402.

- Man X, Zhu X, Sun C. The positive effect of workplace accommodation on creative performance of employees with and without disabilities. Front Psychol. 2020;11(June):1–11.

- Lau S, Nirmalanathan K, Khan M, et al. A Canadian Roadmap for Accessibility Standards. Can Stand Assoc; 2020. (November). Available from: https://www.csagroup.org/wp-content/uploads/CSA-Group-Research-Canadian-Roadmap-for-Accessibility-Standards.pdf

- Lindsay S, Cagliostro E, Albarico M, et al. A systematic review of the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(4):634–655.

- International Labour Organization, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Labour market inclusion of people with disabilities. 2018. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=103080&p_country=IDN

- Aichner T. The economic argument for hiring people with disabilities. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2021;8(1):8–11.

- Bonaccio S, Connelly CE, Gellatly IR, et al. The participation of people with disabilities in the workplace across the employment cycle: employer concerns and research evidence. J Bus Psychol. 2020;35(2):135–158.

- Friedner M. Deaf bodies and corporate bodies: new regimes of value in Bangalore’s business process outsourcing sector. J R Anthropol Inst. 2015;21(2):313–329.

- Friedner M. Producing “silent brewmasters”: deaf workers and added value in India’s coffee cafés. Anthropol Work Rev. 2013;34(1):39–50.

- World Federation of the Deafblind. At risk of exclusion from CRPD and SDGs implementation: Inequality and Persons with Deafblindness; 2018.

- Jaiswal A. Stakeholder Consultation Project. Toronto; 2019. Available from: https://deafblindontario.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019_Stakeholders_Consultation_Report_FINAL-s_1022047.pdf