Abstract

Purpose

Physical activity is recommended as first-choice treatment in chronic pain conditions. The aim was to describe the content and perceptions of person-centred health plans, and to evaluate patients’ implementation of the health plan in their everyday life.

Materials and methods

A descriptive retrospective review was conducted of person-centred health plans to support physical activity in 133 participants. Quantitative content analysis was used to analyse the content of the health plans. Questionnaires on physical activity and on implementation and perception of the health plans, and a test of physical capacity were administered.

Results

Participants’ goals were found to be related to physical function (n = 118), general health (n = 90), activity and participation (n = 80) and symptoms (n = 35). Participants identified personal (n = 174), social (n = 69) and material resources (n = 36). They identified fears and obstacles related to health issues (n = 95), difficulties getting it done (n = 41), competing priorities (n = 19) and contextual factors (n = 12). Participants identified need for external support (n = 110). Participants’ level of physical activity and physical capacity increased significantly during the first 6 months of the study.

Conclusion

The person-centred approach seems helpful in enhancing motivation to achieve set goals and strengthen self-efficacy in physical activity also supported by increased physical activity and physical capacity.

A person-centred approach can be helpful to enhance motivation to achieve set goals and self-efficacy to manage symptoms when engaging in physical activity.

Shared documentation of a personal health plan helps to visualize resources to promote regular physical activity as well as alternative ways to reach set goals.

The co-created health-plan captures the participant’s goals, resources, fears and need of support, helps the participant to overcome challenges, and supports the participant to be physically active.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Chronic pain is defined as pain lasting beyond 3 months [Citation1] and the mean prevalence of chronic pain in the general population is estimated to be 10–15% [Citation2,Citation3]. Chronic pain is associated with disability, impaired physical function, activity limitations and reduced quality of life [Citation4].

Studies on exercise show that persons with chronic widespread pain (CWP) can improve their physical capacity, pain, and wellbeing when regularly performing physical activity [Citation5–7]. Physical activity is recommended as first-choice treatment in chronic pain conditions as it can be individually adapted, is something people can do to help themselves, and is associated with minimal adverse effects, when compared with pharmaceutical interventions. However, it appears to be difficult for most persons with chronic pain to manage to exercise regularly at a health-enhancing level. Therefore, it is important to develop strategies to support long-term sustainability of physical activity.

Engaging the patient in decision-making and in the planning of the treatment process has been reported to enhance motivation for physical activity, as well as the person’s ability to manage pain and other disease-related symptoms during activity [Citation8]. Previous studies have shown that a person-centred approach, comprising individually adjusted physical activity through co-creation of a health plan, is an effective intervention [Citation9,Citation10]. Person-centred care (PCC) is based on ethical principles emphasizing the importance of knowing the patient as a person with resources and needs, and as a person (with health concerns, e.g., with a chronic condition) who is capable of taking responsibility for their health [Citation8]. PCC aims to establish a partnership reflecting the expertise of both the health care professional(s) and the patient.

It is known that a person-centred approach including shared documentation of the jointly agreed health plan differs from traditional approaches to planning and documentation in care and rehabilitation [Citation8,Citation11]. Several studies have reported examples of how person-centred documentation is applied in care/rehabilitation settings, and of challenges with implementation in practice [Citation11–13]. There are, to our knowledge, no studies describing person-centred health plans co-created by physiotherapists and persons with CWP. Therefore, in the present study we will analyse the content of health plans co-created between patients and physiotherapists in a recently published randomized controlled trial (RCT) [Citation14].

Aim

The study’s aim was to describe the content and perceptions of person-centred health plans, and evaluate patients’ implementation of such health plans in their everyday life (after 6 months).

Materials and methods

Study design

A descriptive retrospective review was conducted of person-centred health plans using quantitative content analysis, two questionnaires (one regarding implementation and perception of the health plan, and the other regarding physical activity level) and a test of physical capacity.

Health plans analysed in this study were obtained in an RCT study comprising 139 participants, both men and women. Participants in the intervention and active control group received an individually tailored health plan, and were randomized to different follow-up methods (digital support during 12 months versus one phone call). At the 6-month follow-up, no difference in the primary endpoint was found between the intervention group and the control group [Citation14].

Details of the study procedure, methods and results have been previously reported [Citation14], and are briefly described below. Inclusion criteria were CWP according to American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria [Citation15], i.e., pain below and above the waistline, pain in the left or right side of the body, and axial pain (neck, thorax or lumbar), and age 20–62 years. Exclusion criteria were other dominating causes of pain, such as inflammatory rheumatic disease, neuropathic pain, neurologic disease, or severe arthrosis (Clinical Trials No. NCT03434899).

Co-creation of a health plan

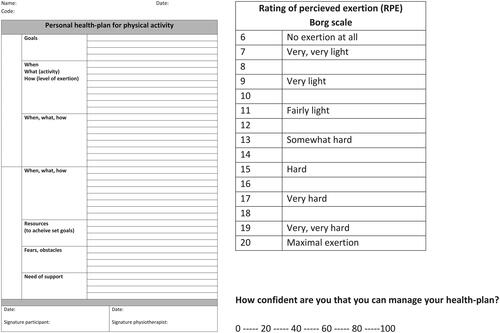

The person-centred health plan was jointly developed between the participants and physiotherapists aiming to support the participants to overcome barriers to physical activity, enhance self-efficacy, and strengthen their ability to manage symptoms and be physically active over time. Each health plan was individually adjusted regarding levels of physical activity and, if needed, stress management. Participants were invited to attend an individual meeting during which they were encouraged to share their narrative with the physiotherapist. During the meeting, the physiotherapist used active listening including open-ended questions, with suggestions for areas to be addressed (see ), to identify the patient’s goals, resources, obstacles and needs. Based on the narrative, a tailored health plan was co-created, reflecting both the participant’s and the physiotherapist’s perspectives and expertise. The aim was that the health plan should be designed in such a way that the participant, based on their situation and prerequisites, would overcome barriers to physical activity and manage to be physically active. Stress management was also included if the patient felt the need for it. The health plan contained items concerning the participant’s goals, activities/interventions (when, what and how), resources (personal or other), fears and obstacles, and their need for support, .

Figure 1. Template for the health plan, Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion scale and visual analogue scale (VAS).

Box 1 Examples of questions used during the dialogue between the participant and the physiotherapist.

The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion scale [Citation16], , was used to illustrate different levels of exertion, and the participant was encouraged to try to reach a fairly strenuous level (Borg score 13–15) during the chosen physical activity.

A visual analogue scale (VAS) scale (0–100%) for rating the participant’s beliefs in the manageability of the planned activities was used, . The participant was asked, “How confident are you that you can manage your health plan?” If the participant rated lower than 80% the health plan was discussed again and revised until the participant was at least 80% certain that the activities in the health plan were manageable [Citation17].

Questionnaires regarding the implementation and perception of the health plan

The implementation of the health plan was assessed at the 6-month follow-up by three questions: “To what extent have you followed the health plan regarding physical activity?” (completely; partially; not at all); “To what extent have you followed the health plan regarding stress management?” (completely; partially; not at all); and “Have you made any changes to the initial health plan you formulated together with the physiotherapist during your visit 6 months ago?” (completely; partially; not at all).

Participants’ perception of co-creation of the health plan was assessed at 6 months’ follow-up by two questions retrieved from the Swedish National Patient Survey (https://patientenkat.se) in which the word “physician” was replaced with “physiotherapist”: “How did you experience the response from the physiotherapist you met 6 months ago?” (very good; good; fairly good); and “Did the physiotherapist sufficiently take into consideration your knowledge and experience of your problems when the health plan was formulated?” (completely; partially; not at all).

Questionnaire regarding physical activity level

Level of leisure time physical activity during a typical week was obtained at baseline and after 6 months, using the Leisure Time Physical Activity Instrument (LTPAI) [Citation18].

Test of physical capacity

Physical capacity was assessed by means of 1-min chair stand test, at baseline and after 6 months. The participant was instructed to stand up and sit down, as rapidly and as many times as possible during 1 min [Citation19].

Analysis

Quantitative content analysis was used to analyse the health plans [Citation20]. First, all health plans were reviewed by two researchers (AL and KM); core content was discussed and textual meaning units were identified and labelled with a code. The meaning units were divided into categories and, where appropriate, subcategories. All codes generating categories and subcategories were noted, counted, and summarized. During the analysis, the two researchers (AL and KM) had regular discussions with each other, and competing interpretations during category development were discussed with their co-authors until consensus was reached.

Statistics

Descriptive data are presented as mean, (SD), and median (min; max) for continuous variables and number (n) and percentage (%) for categorical variables. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for comparison between baseline and post-test for continuous variables.

Results

In total 139 persons with CWP, defined as pain in both sides of the body, pain above and below the waist, and axial pain for at least 3 months, participated in the RCT [Citation14]. The health plans of six of these were missing, leaving 133 persons’ health plans to be reviewed.

Characteristics of study participants are described in .

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population (n = 133).

Health plan goals

The participants’ goals were divided into four categories: physical function (n = 118); general health (n = 90); activity and participation (n = 80); and symptoms (n = 35), . The most frequently reported goals were related to general health or physical function, such as to improve mental health aspects, to increase the ability to exercise/increase physical capacity or to improve muscle strength. Other frequent goals were to relieve pain, to get started with regular exercise and to get the energy to participate in enjoyable social activities.

Table 2. Patient goals.

Planned activities

All health plans except one (n = 132) comprised some kind of aerobic activity. Most participants preferred taking brisk walks several days a week (n = 105), while some preferred bicycling (n = 19), rowing (n = 2) or jogging (n = 6). Often they chose more than one activity and also did dancing (n = 6), exercising in water or swimming (n = 22), horse riding (n = 2), or group exercise (n = 8). The majority of the health plans (n = 91) included strengthening exercises. Sixty-three participants preferred to do their strengthening exercise at home; 25 wanted to visit a gym to exercise, and three did their strengthening exercises in a pool.

The health plans of 99 participants included stress management activities. For these, they chose relaxation and mindfulness exercises, conscious breathing, meditation, and slow walks in the forest. Seven participants planned to perform meditative movement such as yoga or Qigong.

The health plans of 48 participants included exercises designed for flexibility.

Participants’ personal, social and material resources for managing the activities

While co-creating the health plans, several resources were identified. The named resources were divided into three categories: personal resources (n = 174); social resources (n = 69); and material resources (n = 36), . Personal resources, such as being motivated to meet the set goals, were most frequently reported, followed by social resources, such as having someone close who can provide support. Previous positive experiences of exercise and its effects, together with self-efficacy, were also reported as important resources.

Table 3. Identified resources to manage the planned activities.

Identified fears and obstacles

Documented fears and obstacles were divided into four categories: health issues (n = 95); difficulties getting it done (n = 41); competing everyday priorities (n = 19); and contextual factors (n = 12), . Patients reported health issues such as pain and fatigue as being the most frequent fear/obstacle related to management of the health plan. Another obstacle was not getting the exercise done, postponing it until tomorrow, or deficient energy levels. Competing everyday priorities were yet another obstacle reported by the participants.

Table 4. Patient fears and obstacles.

Support needed to manage the planned activities

Participants’ documented support needs to manage the planned activities were divided into two categories: external support (n = 110); and no need of external support (n = 12), . The most commonly reported support need was for the health plan to have follow-ups, together with the need for professional support from a physiotherapist. Another frequently reported support need was the need for structure. Few participants stated that they had no need for external support, and that they could manage on their own.

Table 5. Support needed to manage the planned activities.

Implementation of the health plan (n = 108)

Seventeen percent (n = 18) of the participants had followed the health plan completely regarding physical activity and 75% (n = 81) had followed it partially, while 8% (n = 9) had not followed it at all.

Twenty-six per cent (n = 26) of the participants had followed the health plan completely regarding stress management; 60% (n = 59) had followed it partially, and 14% (n = 14) had not followed it at all.

The most common reasons for not following the health plan were other health-related problems that hindered physical activity, such as prolonged infections, injuries or surgery (n = 24) and increased pain, fatigue, or other disease-related symptoms (n = 21). Other reasons were lack of motivation and stress (n = 14), time limits due to work or family issues (n = 10), and contextual factors such as closed pool, not having access to a horse, or “too hot outside” (n = 4). Yet another reason for not following the health plan was that the participants had increased their physical activity level and/or tried other types of exercise than those documented in the health plan (n = 10).

Participants’ perception of co-creating the health plan (n = 108)

Ninety-four per cent (n = 102) of the participants felt that the response from the physiotherapist at the initial meeting had been very good or good. Ninety-three per cent (n = 98) felt that the physiotherapist had taken their knowledge and experience of their problems into account completely when designing the health plan.

Physical activity level and physical capacity

The amount and level of physical activity, measured using the LTPAI, increased significantly during the first 6 months of the study. Participants increased their mean total physical activity level from 5.9 to 7 h per week (p = 0.023), their mean level of strenuous physical activity from 0 to 1 h per week (p = 0.028) and their mean ability to rise from a chair from 18 times to 22 times in 1 min (p < 0.001).

Discussion

The present study contributes with new knowledge on how co-creation of a health plan can help patients with CWP to develop goals for physical activity that can be performed in their own environment. Goals that were most frequently reported were related to improvement of general health or physical function. Ninety-four per cent (102/108) of the participants felt that the physiotherapist took into account their wishes and expertise, and that they felt well treated. The 6-month follow-up evaluation showed that the level of physical activity had increased and physical capacity had improved.

The findings indicate that a PCC approach enabled the participants and physiotherapists to set jointly agreed goals. It made it possible to identify the patients’ own resources, as well as resources in their social network, which were used to achieve the set goals and promote regular physical activity.

The participants in this study chose goals that they considered relevant and meaningful, such as increasing their physical capacity, improving their mental health, decreasing their pain, and getting the energy to participate in enjoyable social activities. This finding is similar to a previous study where patients set goals related to physical activity, work, relationships, and coping skills [Citation21]. Setting meaningful personal goals related to physical activity as well as choosing activities that can be performed in the patient’s own environment is assumed to make the activity relevant [Citation22] and also to enhance the motivation to achieve set goals [Citation23]. Identifying meaningful goals, rather than aiming for increased function, is described as a difference between PCC and patient-centred care [Citation24]. Co-creating a health plan together with the patient in a person-centred manner is challenging, and requires skills in terms of listening carefully to the patient’s narrative, in order to identify and understand their resources, needs, limitations, strengths, and context [Citation22]. Previous research has indicated that practising PCC means to remould the professional role in order to engage patients to participate as active partners in their own care and treatment [Citation25].

Having shared documentation that captures essential details from the patient narrative including both vulnerability (such as fears and obstacles) and resources is reported to promote the acknowledgement of patients as capable persons [Citation8]. Our results indicate that some of the participants’ fears were related to the disease, while other fears that they expressed, such as lack of time, motivation and social support, can also be found in the general population [Citation26]. Documenting a plan for physical activity is a common routine in physiotherapy although, based on our clinical experience, we believe that patients’ fears, resources, and support needs are not regularly documented. Similar experiences have been reported for other health care professions [Citation11,Citation13]. The participants’ reflection on their fears, resources and need for support, which then were acknowledged and documented in the health plan, may of course have contributed to the participants’ ability to overcome these obstacles and manage the activities planned.

An interesting finding of this study is that co-creation of a health plan using a PCC approach appears to have enabled the participants and physiotherapists to identify the participants’ own personal and social resources to manage jointly agreed goals for regular physical activity. The two most common resources documented in the health plan were own motivation to reach the set goals and positive experience of previous exercise. It is notable that the documented own resources (personal, social and material) were greater in both number and frequency than was the documented need for support. In contrast to traditional care, which is often focused on needs and support from health care, this suggests that a person-centred dialogue highlights and enables visualization and verbalization of the patient’s own abilities and resources. Identification and use of their personal resources can help patients to better manage their illness and enhances their self-efficacy, which in turn is associated with greater physical activity participation and better physical functioning [Citation27]. The concept of self-efficacy is closely related to PCC [Citation17], and previous person-centred interventions have shown to improve patients’ self-efficacy [Citation28], which together with earlier positive experiences is an important factor in rehabilitation and achieving set goals [Citation17].

In addition to using their own resources, the participants in this study mentioned the role of professional support from the physiotherapists in the progression of exercise and, hence, the ability to reach their goals. For some participants, the level of exercise was sufficient to reach set goals, but not for all participants. The follow-ups and progression of the health plan were based on the participant’s own decision to contact the physiotherapist [Citation14]. It is possible that more frequent, scheduled follow-ups to discuss progression of the health plan would have enhanced the participants’ possibilities to achieve set goals. Previous research has shown that when patients scheduled their follow-ups according to their preferences, the mean number of follow-ups during a 12-week intervention was three [Citation9]. This implies that fear of overuse of health care through frequent follow-ups is not warranted.

When asked about the need for external support the participants expressed how important it was to have support from family and friends. It was gratifying to see that 44% (59/133) of the participants had that kind of support. Physical activity is largely a social activity, because people prefer to exercise together, and this applies to both unwell and healthy people. It makes exercise more fun and stimulating, and contributes to getting it done. Another interesting finding is that the participants had insight into the fact that physical activity can improve mental health, affecting wellbeing, mood and stress levels [Citation29], and this was reflected by the goals in their health plans.

The activities chosen by the participants varied considerably, and the amount, dose and frequency of physical activity were adjusted according to the participants’ preferences, ability and resources. Individually adjusted physical activity based on patient preferences has been highlighted in treatment recommendations for patients with chronic pain [Citation30]. Our findings showed that the physical activity level increased among participants; however, only a few participants actually followed the health plan completely, while most participants adjusted the plan based on daily form. One reason for this might be that people with CWP continuously struggle to try to control or avoid pain to be able to perform everyday tasks or manage their work [Citation31]. Pain is an obstacle that has to be coped with in the pursuit of activities and goals that matter [Citation32,Citation33]. Increased pain during or following exercise can be a major obstacle and may lead to a vicious circle of inactivity causing increased pain and disability [Citation34]. Having access to a health plan may have reminded the participants of their resources and helped them to overcome challenges and barriers to meet set goals, resulting in adaptation of the planned activities included in the health plan instead of cancelling all physical activity. Only 8% of participants reported that they did not follow their health plan at all, which indicates that the health plan helped the majority of the participants to overcome obstacles, and thereby promoted physical activity.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the content of health plans co-created by physiotherapists and patients with CWP. One limitation is that the participants were recruited from a previous study, i.e., a convenience sample. However, they were recruited from five different health centres, representing both urban and rural areas in western Sweden. A further limitation is that the participants were not asked whether they had actually reached their individual goals reported in the health plans. Future studies in other settings, with different physical activity profiles, pain profiles and age groups, are warranted to further examine the goals, resources, and requirements when developing health plans for physical activity.

The validity of the content analysis is assumed to be strengthened by the fact that two researchers separately analysed the health plans, developing categories and subcategories, which then were discussed with all other authors who represented different health care professions.

Implications

The results of the present study implicate that this person-centred approach can be helpful in a clinical physiotherapy setting when designing rehabilitation programmes together with patients with CWP. The health plan documentation captures not only the patient’s goals but also their fears, obstacles, resources and support needs when planning for regular physical activity.

Conclusions

The co-created health plans captured not only individual participants’ goals but also their resources, fears and support needs. They helped the participants to overcome challenges, and supported them to be physically active. At a group level, the participants increased their physical activity level and their physical capacity, which suggests that a person-centred approach can enhance motivation to achieve set goals and self-efficacy in managing symptoms when engaging in physical activity.

Ethics

The patients received oral and written information about the study and gave their written consent to participate. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Gothenburg (No. 1025-17).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Närhälsan Rehabilitation Centres, Region Västra Götaland, and the Sahlgrenska University Hospital.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd ed. (revised). Seattle: IASP. 2011.

- Mansfield KE, Sim J, Jordan JL, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic widespread pain in the general population. Pain. 2016;157(1):55–64.

- Bergman S, Herrstrom P, Hogstrom K, et al. Chronic musculoskeletal pain, prevalence rates, and sociodemographic associations in a Swedish population study. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(6):1369–1377. PMID: 11409133.

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):287–287.

- Busch AJ, Webber SC, Brachaniec M, et al. Exercise therapy for fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(5):358–367.

- Larsson A, Palstam A, Löfgren M, et al. Resistance exercise improves muscle strength, health status and pain intensity in fibromyalgia—a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):1–15.

- Mannerkorpi K, Nordeman L, Cider A, et al. Does moderate-to-high intensity Nordic walking improve functional capacity and pain in fibromyalgia? A prospective randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(5):R189.

- Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, et al. Person-centered care-ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10(4):248–251.

- Feldthusen C, Dean E, Forsblad-d’Elia H, et al. Effects of person-centered physical therapy on fatigue-related variables in persons with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(1):26–36.

- Lange E, Kucharski D, Svedlund S, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in older adults with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71(1):61–70.

- Heckemann B, Chaaya M, Jakobsson Ung E, et al. Finding the person in electronic health records. a mixed-methods analysis of person-centered content and language. Health Commun. 2022;37(4):418–424.

- Jansson I, Fors A, Ekman I, et al. Documentation of person-centred health plans for patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17(2):114–122.

- Broderick MC, Coffey A. Person-centred care in nursing documentation. Int J Older People Nurs. 2013;8(4):309–318.

- Juhlin S, Bergenheim A, Gjertsson I, et al. Physical activity with person-centred guidance supported by a digital platform for persons with chronic widespread pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2021;53(4):jrm00175.

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(2):160–172. Med PMID: 2306288.

- Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14(5):377–381.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York (NY): Freeman; 1997.

- Mannerkorpi K, Hernelid C. Leisure time physical activity instrument and Physical Activity at Home and Work Instrument. Development, face validity, construct validity and test-retest reliability for subjects with fibromyalgia. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(12):695–701.

- Mannerkorpi K, Svantesson U, Carlsson J, et al. Tests of functional limitations in fibromyalgia syndrome: a reliability study. Arthritis Care Res. 1999;12(3):193–199.

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage. 2004.

- Gardner T, Refshauge K, McAuley J, et al. Patient led goal setting in chronic low back pain – what goals are important to the patient and are they aligned to what we measure? Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(8):1035–1038.

- Melin J, Nordin Å, Feldthusen C, et al. Goal-setting in physiotherapy: exploring a person-centered perspective. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37(8):863–880.

- Rose A, Rosewilliam S, Soundy A. Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):65–75.

- Eklund JH, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, et al. Same same or different? A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care?. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(1):3–11.

- Boström E, Ali L, Fors A, et al. Registered nurses’ experiences of communication with patients when practising person–centred care over the phone: a qualitative interview study. BMC Nurs. 2020;19(1):1–8.

- Herazo-Beltrán Y, Pinillos Y, Vidarte J, et al. Predictors of perceived barriers to physical activity in the general adult population: a cross-sectional study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2017;21(1):44–50.

- Martinez-Calderon J, Zamora-Campos C, Navarro-Ledesma S, et al. The role of self-efficacy on the prognosis of chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2018;19(1):10–34.

- Britten N, Ekman I, Naldemirci Ö, et al. Learning from Gothenburg model of person centred healthcare. BMJ. 2020;370:m2738.

- Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–1462.

- Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(2):318–328.

- Crombez G, Eccleston C, Van Damme S, et al. Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: the next generation. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(6):475–483.

- Van Damme S, Crombez G, Eccleston C. Coping with pain: a motivational perspective. Pain. 2008;139(1):1–4.

- Karsdorp PA, Vlaeyen JW. Goals matter: both achievement and pain-avoidance goals are associated with pain severity and disability in patients with low back and upper extremity pain. Pain. 2011;152(6):1382–1390.

- Rice D, Nijs J, Kosek E, et al. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free and chronic pain populations: state of the art and future directions. J Pain. 2019;20(11):1249–1266.