Abstract

Purpose

Over the past two decades, healthcare systems have shifted to adopt a more holistic, patient-centered care system. However, operationalization in practice remains challenging. Two frameworks have contributed substantially to the transformation toward more holistic and patient-centered care: the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and the capability approach (CA). Using these frameworks jointly can contribute to improved patient-centered care in clinical practice.

Methods

This article explores the strengths and weaknesses of the use of the two frameworks in care and investigates whether using them jointly might contribute to more appropriate and patient-centered care. We will present a practical example of this integration in the form of a novel e-health application.

Results

The exploration indicated that if the frameworks are used jointly, the individual weaknesses can be overcome. The application, used to exemplify the joint use of the frameworks, contains all categories of the ICF. It offers a unique tool that allows a person to self-assess, record, and evaluate their functioning and capabilities and formulate related goals.

Conclusions

Using the ICF jointly with the CA can foster holistic, patient-centered care. The e-health application provides a concrete example of how the frameworks can be used jointly.

Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health jointly with the capability approach can foster holistic, patient-centered care.

The joint use of the frameworks is demonstrated by an e-health application which enables users to evaluate their functioning in relation to their own goals, provides them with the opportunity to increase control over their health and have a more active role in their care.

Tools to record both functioning and goals from a patient’s perspective can support professionals in offering patient-centered care in daily practice.

Individual recording, monitoring and evaluation of functioning, capabilities and goals regarding functioning can provide a basis for research and quality improvement.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Over the past two decades, healthcare systems have shifted to a more holistic, patient-centered care system [Citation1]. Patient-centered care was defined in 2001 by the Institute of Medicine as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions” [Citation2]. Patient-centered interactions between professionals and patients lead to better health outcomes [Citation3]. However, operationalization in practice remains challenging [Citation4]. Traditional practices and attitudes have been identified as barriers to implementing patient-centered care, including the dominance of the biomedical paradigm and the predefined structure of care pathways [Citation5]. Indeed, the separate treatment of each of a patient’s condition often does not improve a patient’s health outcomes and can lead to unnecessarily complex interactions with the healthcare system [Citation6].

Two frameworks have contributed substantially over the past two decades to the transformation toward more holistic and patient-centered care. One is the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation7]. The ICF is based on an integrative model of health and provides a holistic, multidimensional, and interdisciplinary model which can be used to describe and classify health and health-related conditions. It is a framework and classification system that integrates biological, individual, and social aspects of health. It can be used at individual and population level and contains over 1500 categories related to body functions, activity, social participation, and environmental factors influencing functioning. It provides a universal language for describing functioning, and a person’s lived experience of health. Since publication in 2001, the ICF has contributed greatly to the shift in “the way we think about, measure, design, collect and analyze data about functioning and disability” [Citation8]. Publications in which the ICF is applied have increased tremendously over the last 20 years [Citation9].

The other framework is the capability approach (CA), initiated by Amartya Sen and further developed jointly with Martha Nussbaum. The CA is a theoretical framework based on the normative assumption that people should have the freedom to live a life they value. The two main concepts in the CA are functionings and capabilities. Functionings, within this approach, refer specifically to what people are actually doing (e.g., working) or being (e.g., being well-fed), whereas capabilities are the real freedoms or opportunities that people have to do and be what they have reason to value (the opportunity to choose between working or staying at home to raise one’s children, to eat a nourishing meal, or skip a meal during the day by choice) [Citation10,Citation11]. Over the last decade, the framework has been used to define disability [Citation12] and has since then increasingly been applied in various settings in the health and social care [Citation13]. It has been proposed as a bridging framework for transdisciplinary health promotion [Citation14] and efforts have been made through data collection and research to operationalize the framework [Citation12].

There are considerable parallels between the two approaches. Both the ICF and CA offer the possibility tolook beyond the presence of health conditions and address respectively human functioning and individual choice and preferences in a holistic, comprehensive way. The ICF and the CA acknowledge the influence of contextual factors on individual functioning, including personal and environmental factors. However, the two frameworks differ in their main purpose. The CA is a normative, theoretical framework focusing on well-being, quality of life, and social justice [Citation10,Citation11]. The ICF is both a conceptual framework and a classification based on the biopsychosocial model that is used primarily to describe health and health-related conditions [Citation7]. As a classification, the ICF organizes and codes this health information for data collection and comparison, health information systems, and other reasons [Citation15]. Neither the ICF nor the CA are assessment instruments, which allows for the development of assessment tools that incorporate both complementary approaches to improve the assessment of health and functioning.

To date, reflection on the joint use of the two frameworks is limited and practical joint implementation in care is lacking. The aim of this article is to investigate whether the two frameworks can be theoretically integrated and to present a practical example of an application of an integrated framework.

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

Core components

In 1980, the World Health Organisation published the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH) as a tool for the classification of the consequences of disease (as well as of injuries and other disorders) and of their implications for the lives of individuals. The aim was to provide a model of disability that synthesizes the medical and the social model, without reducing the whole, complex notion of disability to one of its aspects.

The ICIDH was subsequently criticized for its focus on negative consequences of a disease, a lack of environmental and personal factors in the classification, and outdated terminology like “handicap” [Citation16,Citation17]. In response to these critiques and after extensive deliberation and testing, the WHO revised the framework and presented a new framework, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, abbreviated as ICF. Based on the biopsychosocial model, the ICF integrates biological, individual, and social aspects of health. In the ICF, the focus shifted from a linear model of causation between impairments and handicaps to a multidimensional model on functioning and health and included environmental and personal factors influencing functioning. With these adaptations, the ICF framework became suitable for organizing and documenting information on functioning and disability [Citation7]. At this moment, the ICF is the only international reference language that enables standardized collection and recording of information about the lived experience of health [Citation18] and offers the possibility to compare the functioning of people globally [Citation19]. The ICF is regularly updated by the WHO in an iterative process of improvement and it is encouraged that people with disability have greater involvement in this process [Citation20].

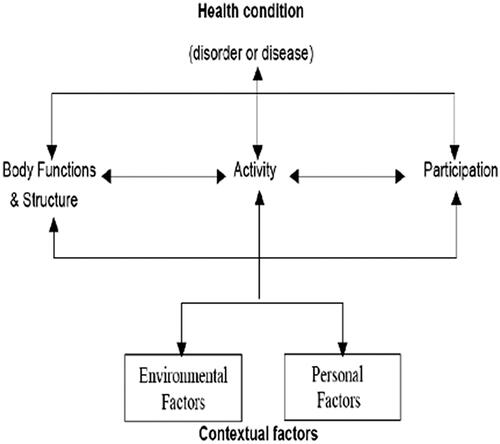

As depicted in , the framework represents functioning as the dynamic interaction between a person’s health condition, the environmental factors, and personal factors (contextual factors). The interaction between the components and contextual factors is complex, often unpredictable, and bidirectional [Citation7]. The ICF can be used to monitor the dynamic interaction between aspects of functioning longitudinally over time.

Figure 1. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

Use in healthcare

The ICF is meant for use for all people and within a wide range of settings. In the 20 years since the ICF was published, it has valuably been applied in clinical practice, public health, health information, health sciences, health policy, and education [Citation9]. Two review articles describe the broad domains of clinical and non-clinical settings in which the ICF has been implemented [Citation21,Citation22]. An example of the use of the ICF in a community setting – to assess the functioning and to describe goals that match the objectives regarding their functioning, showed that the ICF allowed community workers to manage and track important outcomes, and the professionals appreciated that the ICF offered them the opportunity to apply their skills more holistically, leading to improved overall functioning [Citation23].

However, although suitable to describe functioning for all persons and settings, the ICF is most dominantly used in specialized rehabilitative settings for people with specific chronic conditions and disabilities, in physical therapy and in occupational therapy practice [Citation24]. The ability to describe a person's functioning without having to assign a disease label is a benefit of the use of the ICF, thus enabling the use in a variety of situations outside of the healthcare domain such as in the education or occupational health domain. Furthermore, the ICF can provide a framework for the education of health care professionals as it provides a common language which can improve collaboration and interdisciplinary communication [Citation25,Citation26].

Instruments to evaluate care can be derived or developed using ICF terms. An example of a questionnaire based on the ICF is the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) [Citation27]. The WHODAS consist of questions on six domains of functioning: cognition, mobility, self-care, getting along, life activities, and participation. The WHODAS can be used to evaluate functioning before and after an intervention. Next to the WHODAS, over recent years multiple ICF core sets have been developed. ICF core sets are questionnaires with a selection of disease-specific categories of the ICF and are used in several healthcare settings. A core set is used to describe the functioning of a person living with a specific health condition [Citation28]. The Rehabilitation Problem-Solving Form, based on the ICF, is used to describe functioning from both the perspective of the patient and professionals and aims to improve the participation of patients in the decision-making process in their individual rehabilitation treatment plan [Citation29].

The ICF can be used as a framework for instruments to self-assess functioning and to individuals’ aspirations regarding their functioning. Several tools have been developed to self-assess functioning, such as YIPE. This tool aims to support the development of person-centered goals and communicate needs with professionals. The instrument consists of 83 self-reported items and includes items related to ICF “activities, participation and environmental factors” chapters and their interactions [Citation30]. The study confirmed the importance of considering both participation and the environment together.

Madden et al. [Citation19] have stressed the need for an Integrative Measure of Functioning (IMF) based on the concepts of functioning and environmental factors in the ICF, both in practice and policy. An IMF could deliver person-centered, policy-relevant information regarding functioning for a range of programs, promoting harmonized language and measurement and supporting international trends in human services and public health. Assessments and measurements of functioning could further improve the knowledge of the “health capacity and environmental determinants of people’s actual experience of living with health conditions in their environments” [Citation18].

Potential barriers for applying the framework in practice

The large number of ICF categories remains a potential barrier to the use of the ICF in practice. Using the entire classification allows for maximum specificity but can be time-consuming and difficult to manage. The use of the WHODAS, an ICF-based questionnaire, is an example of limiting the number of ICF categories [Citation31]. Another example is the use of ICF core sets, sets which contain a selection of ICF categories for specific health conditions, groups and/or settings. ICF core sets are developed in a multi-stage process [Citation28] and their availability has contributed greatly to the use of the ICF in clinical practice [Citation9]. Depending on the purpose and specific user needs, an appropriate level of granularity of ICF can be chosen, allowing functioning to be described at a broad, domain level or in a more detailed level [Citation31].

The current, purposeful absence of personal factors in the ICF classification, according to some, is another possible barrier. Personal factors refer to “the particular background of an individual’s life and living and comprise features of the individual that are not part of a health condition or health states” such as gender, race, age, education, and character style [Citation7]. While these are recognized as important in the ICF framework, personal characteristics are not included in the ICF classification codes due to a lack of international consensus. Personal characteristics, have the potential to improve the “understanding of functioning, disability and health, facilitate interventions and services for people with disabilities, and strengthening the perspective of individuals in the ICF” [Citation32]. Therefore, it is argued that personal factors might be an aspect of the ICF that needs to be further developed as these factors are believed to significantly influence how people function [Citation33,Citation34]. One should, however, be aware that their inclusion might raise conceptual and practical challenges including duplication and, potentially, “victim blaming” and stigmatization [Citation35,Citation36].

Third, if functioning is assessed only from the perspective of the professional, the individual’s own goals and aspirations are not sufficiently addressed [Citation37,Citation38]. The ICF provides an agreed framework which can be used for individual goal setting in clinical settings. However, the use in practice from the subjective perspective of the individual and their individual choices regarding their functioning is still limited [Citation39].

Capability approach

Core components

Amartya Sen first introduced the CA [Citation10], asserting that welfare should be evaluated according to the extent that people have the freedom to live a life they are willing to lead. The approach entails two core normative claims: freedom to achieve well-being is of primary moral importance, and freedom to achieve well-being is to be understood in terms of people's capabilities. A core concept of the CA is agency. Agency has been referred to as a person “deciding and acting based on what he/she values and has reason to value, whether or not that action is personally advantageous. A person’s agency freedom is the freedom to make decisions and the power to act and be effective” [Citation40].

Another core concept in the CA is the notion of conversion factor, which is based on the idea that “persons have different abilities to convert resources into functionings”. Conversion factors determine the extent to which people are capable of converting resources into capabilities and functionings. Resources are the means to realize functionings. Resources can be material, like having access to transportation or the internet but also having access to education or healthcare are considered resources [Citation41].

Sen emphasizes human capacity to act and rejects the idea that capabilities can be captured in a specific list, as this would be detrimental for individual free choice. This stance has been supported by other scholars who have provided alternatives including a procedural approach to determining capabilities [Citation42] and a participatory evaluation of capabilities [Citation43]. Martha Nussbaum, who approaches the CA from a narrative, political-philosophical perspective, however proposed a list of 10 basic human capabilities. The list was developed through conversations with women, and particularly with marginalized women in the low-income countries. These 10 capabilities are (1) life, (2) bodily health, (3) bodily integrity, (4) senses, imagination, and thought, (5) emotions, (6) practical reason, (7) affiliation, (8) to live with and enjoy other species, (9) play, and (10) control over one’s environment [Citation44]. Nussbaum’s rationale for defining a list of basic capabilities is that a just society should provide means for people to accomplish at least certain capabilities and evaluate if the conditions to fulfill these capabilities are met, protected, and restored [Citation45].

Use in healthcare

The CA is relevant for healthcare, as it aims to strengthen well-being and quality of life from a broad perspective. It offers a valuable foundation for person-centered health care interventions, as patient-centered care “involves recognizing and cultivating patients’ person-al capabilities” [Citation46]. The CA has been described as a promising framework for “developing interventions responsive to both personal and environmental determinants” [Citation47]. Ruger has applied the theory to the healthcare domain and defined functionings and capabilities from this perspective. In the context of care, in her view, health can be seen as a capability or a functioning. Health capability consists of both health functioning and health agency. Health functioning is the “outcome of the action to maintain or improve health”. Health agency refers to the “ability to achieve health goals they value and act as agents of their own health” [Citation48]. Utilizing the CA as a framework to assess health assessment should include “indicators based on the achieved dimension (health functioning), resources and conversion factors (health capability), and freedom to achieve (agency)” [Citation49].

A review of applications of the CA in health care found four areas of care in which applications of the theory were used; physical activity and diet; patient empowerment; multidimensional poverty and assessments of health; and assessments of social care interventions [Citation13]. Applications related to physical activity and diet both involved a focus on the built environment to strengthen the capability of being physically active, questionnaires to measure this capability, and on the use of an instrument to assess the opportunities for healthy behavior. Studies that focused on patient empowerment identified factors that facilitate making decisions regarding one’s health. Factors related to poverty were particularly influential [Citation50]. People with chronic conditions were more likely to be multidimensionally poor (with limited income, education, and health). These studies called for the further development of the assessment of multidimensional poverty. Lastly, a number of studies described the development of instruments to capture capabilities supported by social care [Citation13].

An important implication of the CA is that social policies, programs, and services should be developed to expand individual capabilities. A true test of development is whether individuals have greater capabilities and greater freedoms to achieve their beings and doings. An attempt to collect and measure capabilities is the Human Development Index (HDI) [Citation51]. The HDI is “a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, being knowledgeable and have a decent standard of living” [Citation52]. The HDI is mainly used in the comparison between countries.

Operationalization of the CA with capabilities questionnaires has been developed in health economics to assess and evaluate important domains of well-being. A variety of measurements have been proposed, depending in the specific research-objectives [Citation53]. Examples of capabilities-based questionnaires are the ICEpop CAPability-O (ICECAP-O) for older people, the ICECAP-A for adults and the ICECACP-SCM for end-of-life care, the Oxford Capabilities Questionnaire-Mental Health (OxCap-MH), and the ASCOT Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT). The ASCOT is aimed for use with older people and combines both functioning and capabilities [Citation13,Citation45,Citation54]. The questionnaires to assess capabilities have been used and translated for different countries and applied in several health-care settings [Citation13,Citation45].

Potential barriers for applying the framework in practice

Due to the broad and abstract nature of the CA, operationalization in practice is challenging. One potential barrier of operationalization is uncertainty about how to assess outcomes for people. Most often evaluations are based on qualitative research methods. Over the past decade, efforts have been made to operationalize evaluations of the CA through questionnaires but these quantitative measurements do not always take the “choice” dimension of the CA framework into account [Citation55]. Finally, as the CA is an open-ended theoretical framework, Nussbaum has argued that the theory is mainly to be used in public policy, as the government is the most important change agent [Citation41].

Integrating the ICF and CA

Both the ICF and the CA offer the possibility to, respectively, look beyond a person with a health-condition toward how patients function in all life-domains, and to prioritize what they have reason to value. Both approaches acknowledge and value human diversity. The ICF recognizes the diversity of functioning in people. For example, two people with the same health condition may differ considerably in their respective functioning. In the CA, diversity is a basic claim; “human diversity is no secondary complication (to be ignored, or to be introduced later on); it is a fundamental aspect of our interest in equality” [Citation56]. The recognition of diversity within both the ICF and the CA is considered the primary inherent strength of these models [Citation57].

Both Bickenbach and Mitra have pointed out commonalities of the two frameworks; both the ICF and the CA acknowledge that environmental and personal factors are relevant for people with health conditions in their day-to-day lives and the independence of disability from health conditions. The frameworks do not use disability-related terminology but emphasize the importance of using neutrality of terminology. Bickenbach however also concludes that the CA as a normative framework lacks operationalization and might not have enough potential to bring about change. Mitra points out that the lack of information on choice, personal goals, and resources is a limitation of the ICF and that the CA, in contrast to the ICF, has the advantage of focusing on individual’s capabilities and functioning through choice and decision-making. Mitra further states that as CA is an open-ended conceptual framework; it is more holistic than the ICF. However, Mitra [Citation58,Citation59] suggests that the ICF classification can be used to operationalize the CA at an international level by expanding the ICF with central aspects of the CA and that in a revised model of the ICF, the concept of agency should be included.

Conceptually, Welch Saleeby has acknowledged the parallels between, and the potential complementarity of, the ICF and the CA and has argued that joint use of the two frameworks would be useful. The ICF focuses on functionings; the CA can help assess functioning and capabilities. Using the ICF and the CA jointly may contribute to an improved understanding of the life situations of individuals [Citation60].

At present, illness and disease are well recorded in patients’ files but a systematic review has shown that while the ICF is accepted as a conceptual and terminological standard, its implementation into Electronic Health Records (EHR) is still limited [Citation61].

The narrative, goals, and actions of the person themselves serve as a starting point for personalized and value-based integrated healthcare. Using the two frameworks jointly can foster the implementation of patient-centered care in which care is based on how people perceive their functioning as well as which goals and actions they choose to set. These assessments could be included in EHR-registrations. The joint use has also the potential to serve as a foundation for interprofessional education and communication. Lastly, using both frameworks jointly is not limited to the healthcare domain and can also enhance practices in other domains such as education or the occupational health care-domain.

A practice example: an e-health application recording individual functionings and personal goals

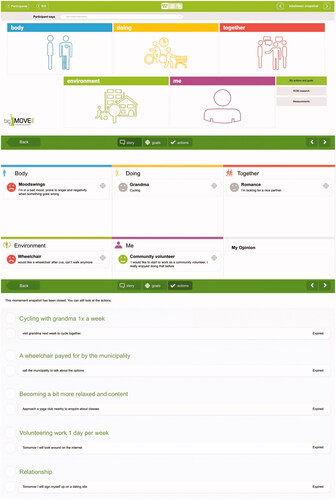

We will present an e-health application in which such joint use of the ICF and the CA is operationalized in a user-friendly format. The e-health application, which was developed in 2011, contains all categories of the ICF classification, including a list of personal factors. In the application, the participants record their evaluation of their current functioning, and their goals for future functioning. Recording functioning as experienced by the person, the subjective evaluation of functioning as positive, neutral or negative, and the setting of goals by the person, produces a measurement of functionings and capabilities. The ICF, therefore, is enhanced with an element of individual choice.

A Dutch IT company, ICF experts, health professionals, and end-users collaboratively developed the app in an iterative process. The app, used on a tablet, has a user-friendly interface based on the ICF scheme. The choice for an e-health application was based on the rationale that a digital application is user-friendly and offers the opportunity to assess all categories as described in the ICF in an attractive, clearly visible way. Moreover, it is not bound to any particular discipline, and easily used by professionals and lay persons. The Dutch WHO collaborating center [Citation62], a designated center to carry out activities in support of the WHO’s programs in countries, regions and at headquarters, approved usage of the ICF in the application. The application is regularly updated based on error reports and user experiences.

In the application of lay terms are used for the description of categories and the categories are supported by specially designed icons. At the top of the application, there is a search bar which will help persons to select the applicable category. As lay terms are used the application might show several categories which are connected to a lay term.

The assessment can address all aspects of functioning, perceived as positive, neutral of negative. In addition, the application provides the opportunity to record individual goals and related actions. Goals regarding functioning are chosen by the user and recorded.

The recording of current functioning and aspirations in the e-health application, supported by the professionals, serves four goals: (1) to increase patients’ influence and choice regarding their functioning, (2) to give them a more equal position in the delivery for care, (3) to provide a more accurate evaluation of functionings and capabilities from the perspective of patient, and (4) to provide a more standard recording of functioning suitable for use in research and quality improvement. The application has been used in the BigMove intervention, that aims to improve functioning of people with a combination of physical and mental health problems. Professionals involved in the intervention receive training in motivational interviewing and support participants in describing how they perceive their overall functioning and in setting goals. During the intervention functioning is re-assessed and previous goals are discussed and adjusted where necessary ().

Figure 2. Screenshots of the application (a) home screen reflecting framework of ICF, (b) self-assessment on functioning, and (c) setting of goals and actions.

An example of how functioning is recorded in the application is:

Walking D 450 (ICF category-code): I am not able to walk to my friend’s house ![]() (negative)

(negative)

Goal: After a period of 4 weeks, I will be able to be able to walk to my friend’s house.

Action: I will practice every day with walking to reach my goal

From a CA perspective, the example makes the distinction between functioning and capabilities and reflects the concept of agency:

Functioning: Not able to walk to a friend’s house

Capabilities: I value visiting my friend; therefore, I assess this functioning as negative.

Agency: I aspire to achieve this functioning because I value being able to walk to my friend, therefore I choose to work on achieving this functioning.

Strengths and limitations of using the ICF and CA jointly in an application

To record both individual assessment of functioning and setting of personal goals an e-health application has been developed. A strength of the application is that it records the perspective of a person on their functioning, with the ability to address all categories of the ICF; it also records the goals that a person wants to achieve. It not only provides insight for persons themselves but also allows functioning, to be broadly recorded and not limited through the selection of categories as is the case in core sets or questionnaires, both ICF and CA based. A limitation of the application is that it is not yet integrated with existing EHR and therefore used next to EHR. The implication is that both for patients and professionals the recording of functionings and capabilities will require extra time and information about goals and aspirations is absent in EHR.

A second limitation is that the assessment of functionings and capabilities is focused on the patient’s present perspective and aspirations. The application is not designed to evaluate whether aspired functionings or goals are achieved but to assess over time how patient perceive their functioning and aspirations. In a hospital setting, the application was used to study the usability of an ICF core set. The application proved to be reliable to collect and use data related to used ICF categories for scientific research [Citation63]. There are plans to further develop and implement the application in several settings in the near future. As the ICF and CA can be used without the need to label diseases or diagnoses, their joint use, and the specific tool, presented in this article, can be useful in settings outside the clinical care domain. In the application, environmental factors are included and future evaluation of the use of the application in practice will also provide insights in the environmental factors relevant to the users. Further research is needed to explore the user-experience of the application from both the patient and professional perspective and to further tailor it to the user-needs.

Conclusions

In this article, we have argued that, in order to foster holistic healthcare, joint use of the ICF and the CA is desirable. We argued that it is possible to integrate the ICF and the CA, both in theory and practice. Theoretically, the proposed joint use of the frameworks (1) provides the opportunity to increase patients’ influence and choice regarding their functioning, and to give them a more equal position in the delivery for care, (2) enables an evaluation of functionings and capabilities from the perspective of patients, and (3) provides a basis for recording of functioning and evaluation of goals suitable for use in research and quality improvement. We also presented a practice example, an e-health application, containing all categories of the ICF and reflecting the core assumptions of the CA, allowing a person to self-assess their functioning and capabilities and express their functioning related goals and aspirations.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Lim SA, Khorrami A, Wassersug RJ. Twenty years on – has patient-centered care been equally well integrated among medical specialties? Postgrad Med. 2022;134(1):20–25.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

- Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(12):600–607.

- Giusti A, Nkhoma K, Petrus R, et al. The empirical evidence underpinning the concept and practice of person-centred care for serious illness: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(12):e003330.

- Moore L, Britten N, Lydahl D, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of person-centred care in different healthcare contexts. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31(4):662–673.

- Whitty CJM, MacEwen C, Goddard A, et al. Rising to the challenge of multimorbidity. BMJ. 2020;368:l6964.

- WHO. ICF. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Madden RH, Bundy A. The ICF has made a difference to functioning and disability measurement and statistics. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(12):1450–1462.

- Cieza A, Kostansjek N. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: the first 20 years. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021;63(4):363.

- Sen A. Equality of what? In: McMurrin SM, editor. Tanner lectures on human values. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press; 1980.

- Nussbaum M, Sen A. The quality of life. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1993.

- Mitra S. The human development model of disability, health and wellbeing. In: Palgrave Pivot, editor. Disability, health and human development. Palgrave studies in disability and international development. New York: Palgrave Pivot; 2018.

- Mitchell PM, Roberts TE, Barton PM, et al. Applications of the capability approach in the health field: a literature review. Soc Indic Res. 2017;133(1):345–371.

- Frahsa A, Abel T, Gelius P, et al. The capability approach as a bridging framework across health promotion settings: theoretical and empirical considerations. Health Promot Int. 2021;36(2):493–504.

- Kostanjsek N. Use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a conceptual framework and common language for disability statistics and health information systems. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl. 4):S3.

- Dickson HG. Problems with the ICIDH definition of impairment. Disabil Rehabil. 1996;18(1):52–54.

- Pfeiffer D. The ICIDH and the need for its revision. Disabil Soc. 1998;13(4):503–523.

- Bickenbach J. Human functioning: developments and grand challenges. Front Rehabil Sci. 2021;1:3.

- Madden RH, Glozier N, Fortune N, et al. In search of an integrative measure of functioning. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(6):5815–5832.

- Sykes CR, Maribo T, Stallinga HA, et al. Remodeling of the ICF: a commentary. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(1):100978.

- Cerniauskaite M, Quintas R, Boldt C, et al. Systematic literature review on ICF from 2001 to 2009: its use, implementation and operationalisation. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(4):281–309.

- Maribo T, Petersen KS, Handberg C, et al. Systematic literature review on ICF from 2001 to 2013 in the Nordic countries focusing on clinical and rehabilitation context. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8(1):1–9.

- Ferrer RL, Gonzalez Schlenker C, Lozano Romero R, et al. Advanced primary care in San Antonio: linking practice and community strategies to improve health. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(3):288–298.

- Debrouwere I, Lebeer J, Prinzie P. The use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in primary care: findings of exploratory implementation throughout life. Disabil CBR Inclus Dev. 2016;27(2):57–76.

- Snyman S, Heidi Anttila H, de Camargo OAK, et al. The ICanFunction mHealth solution (mICF): a project bringing equity to health and social care within a person-centered approach. J Interprofess Workforce Res Dev. 2019;2(1):1–17.

- Moran M, Bickford J, Barradell S, et al. Embedding the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in health professions curricula to enable interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520933855.

- Üstün TB. Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule WHODAS 2.0. Geneva, Switserland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Selb M, Escorpizo R, Kostanjsek N, et al. A guide on how to develop an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health core set. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51(1):105–117.

- Steiner WA, Ryser L, Huber E, et al. Use of the ICF model as a clinical problem-solving tool in physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine. Phys Ther. 2002;82(11):1098–1107.

- Cheeseman D, Madden R, Bundy A. Your ideas about participation and environment: a new self-report instrument. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(22):1903–1908.

- World Health Organization. How to use the ICF: a practical manual for using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO; 2013.

- Geyh S, Peter C, Müller R, et al. The personal factors of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in the literature – a systematic review and content analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(13–14):1089–1102.

- Grotkamp S, Cibis W, Brüggemann S, et al. Personal factors classification revisited: a proposal in the light of the biopsychosocial model of the World Health Organization (WHO). Aust J Rehabil Counsel. 2020;26(2):73–91.

- Jelsma J. Use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: a literature survey. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41(1):1–12.

- Simeonsson RJ, Lollar D, Björck-Åkesson E, et al. ICF and ICF-CY lessons learned: Pandora's box of personal factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(25):2187–2194.

- Heerkens YF, de Weerd M, Huber M, et al. Reconsideration of the scheme of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: incentives from The Netherlands for a global debate. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(5):603–611.

- Trani JF, Bakhshi P, Bellanca N, et al. Disabilities through the capability approach lens: implications for public policies. Alter. 2011;5(3):143–157.

- Wade DT, Halligan PW. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(8):995–1004.

- Leonardi M, Fheodoroff K. Goal setting with ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health) and multidisciplinary team approach in stroke rehabilitation. In: Platz T, editor. Clinical pathways in stroke rehabilitation. Cham: Springer. 2021.

- Crocker D. Sen’s concept of agency. Human Development and Capability Association Conference; New Delhi; 2008. p. 10–13.

- Robeyns I. Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: the capability approach re-examined. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers; 2017.

- Robeyns I. Sen’s capability approach and gender inequality: selecting relevant capabilities. Femin Econ. 2003;9(2–3):61–92.

- Alkire S. Valuing freedoms: Sen's capability approach and poverty reduction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002.

- Nussbaum MC. Women and human development: the capabilities approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

- van Loon MS, van Leeuwen KM, Ostelo RWJG, et al. Quality of life in a broader perspective: does ASCOT reflect the capability approach? Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1181–1189.

- Entwistle VA, Watt IS. Treating patients as persons: a capabilities approach to support delivery of person-centered care. Am J Bioeth. 2013;13(8):29–39.

- Ferrer RL, Cruz I, Burge S, et al. Measuring capability for healthy diet and physical activity. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(1):46–56.

- Ruger JP. Health capability: conceptualization and operationalization. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):41–49.

- López Barreda R, Robertson-Preidler J, Bedregal García P. Health assessment and the capability approach. Glob Bioeth. 2019;30(1):19–27.

- Welch Saleeby P. Applying the capabilities approach to disability, poverty, and gender. In: Comim F, Nussbaum MC, editors. Capabilities, gender, equality: towards fundamental entitlements. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 308–321.

- Anand S, Sen A. Human Development Index: methodology & measurement, occasional paper 12, human development report office. New York: UNDP; 1993.

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Index; [cited 2021 May 25]. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi

- Chiappero-Martinetti E, Roche JM. Operationalization of the capability approach, from theory to practice: a review of techniques and empirical applications. In: Chiappero-Martinetti E, editor. Debating global society: reach and limits of the capability approach. Milan: Fondazione Giangiacomo Feltrinelli; 2009. p. 157–201.

- Karimi M, Brazier J, Basarir H. The capability approach: a critical review of its application in health Economics. Value Health. 2016;19(6):795–799.

- Bickenbach J. Reconciling the capability approach and the ICF. Alter. 2014;8(1):10–23.

- Sen A. Inequality reexamined. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992.

- Lowry C, Welch Saleeby P, Chatterji S, et al. From disability theory to practice: essays in honor of Jerome E. Bickenbach. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield; 2018.

- Mitra S. Reconciling the capability approach and the ICF: a response. Alter. 2014;8(1):24–29.

- Mitra S, Shakespeare T. Remodeling the ICF. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(3):337–339.

- Welch Saleeby P. Applications of a capability approach to disability and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in social work practice. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2006;6(1–2):217–232.

- Maritz R, Aronsky D, Prodinger B. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in electronic health records. A systematic literature review. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(3):964–980.

- WHO; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/about/collaboration/collaborating-centres

- Stallinga HA, Bakker J, Haan SJ, et al. The usability of the preliminary ICF core set for hospitalized patients after a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from the perspective of nurses: a feasibility study. Front Rehabilit Sci. 2021. DOI:10.3389/fresc.2021.710127