Abstract

Purpose

To develop a new assessment form that is assessed by therapists for the performance of public transportation use for stroke survivors through content validation.

Materials and Methods

The items for the tentative assessment form were selected using hierarchical clustering analysis on previous records of 76 field-based training sessions for public transportation use for stroke survivors. After the modification of the tentative form based on 6 months of clinical use, the final form was developed through content validation using the Delphi method by 71 therapists who had been working at the hospital for more than 2 years and had experience with training for public transportation use.

Results

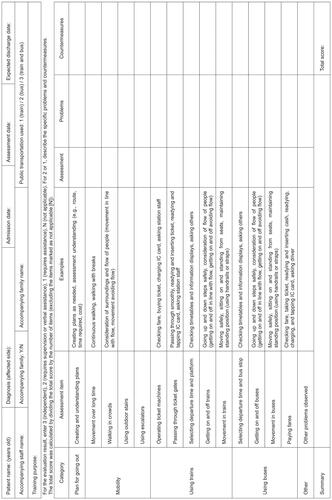

The Public Transportation use Assessment Form (PTAF) for stroke was successfully developed through three validation processes. It consists of four categories (plan for going out, mobility, using trains, and using buses) including 15 items that cover various tasks of public transportation use. The scoring for each was as follows: 3, independent; 2, requires supervision of verbal assistance; 1, requires assistance; and N, not applicable.

Conclusion

The PTAF, developed through content validation, could assess the ability of public transportation use, and identify specific problems for each stroke survivor in clinical setting.

We developed the Public Transportation use Assessment Form (PTAF) to assess the ability of stroke survivors to use public transportation.

The PTAF could identify specific problems related to public transportation use for stroke survivors and aid in planning rehabilitation programs based on the results.

The PTAF could share information about which task need support in public transportation use and could augment the hospital discharge plan.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Going out is important for social participation and health promotion. When going out, various modes of transportation are used depending on the area of residence, the distance to the destination, the purpose, and individual lifestyle. Public transportation use is an essential mode of transportation, especially for people who live in urban areas [Citation1] that have well developed public transportation systems for outings, such as for commuting and shopping. Furthermore, using public transportation also has its advantages, such as being pro-environmental and reducing the cost of commutation. In stroke survivors, the ability to use public transportation is a major factor in expanding the range of activities and social participation [Citation2]. Previous studies have reported that 31% of stroke survivors returned to driving within 6 months after stroke onset [Citation3], and 61%–65% of stroke survivors returned to driving within one year [Citation4,Citation5], indicating that many stroke survivors are unable to return to driving. Thus, stroke survivors particularly need an alternative mode of transportation. Therefore, acquiring the skills for public transportation use is an important rehabilitation goal to expand the life spaces of individuals with stroke.

Although train use varies among countries and regions, 52%–60% of the people aged between 12 and 74 years who live in metropolitan areas in Japan use the train at least once a week [Citation6]. However, the use of public transportation is difficult for stroke survivors. A study from Sweden reported that approximately only 9% and 21% of stroke survivors used the train and bus in the preceding year of the study, respectively [Citation7]; and, in Sweden, the use of public transportation was reduced or discontinued in 51% of stroke survivors who had been using public transportation before stroke onset [Citation8]. Using public transportation comprises many tasks, and therefore presents many potential barriers for stroke survivors [Citation9–11]. Thus, rehabilitative intervention with appropriate assessment is important.

However, there are few assessment tools focused on stroke survivors using public transportation. The common instrumental activities of daily living assessment tools such as Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Scale (NEADL) [Citation12], Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL) [Citation13], and Frenchay Activities Index (FAI) [Citation14], include items of public transportation use. The NEADL can assess the degree of independence in public transportation use; the IADL can assess the degree of independence in mobility, including modes of transportation other than public transportation; and the FAI can assess the frequency of public transportation use. These assessment tools cannot evaluate a patient’s ability to use public transportation in detail; although, they can be used to assess the outcomes in interventional studies on going out after stroke [Citation15]. Sawada et al. conducted a questionnaire survey among occupational therapists working in rehabilitation wards to determine what items they assessed in their clinical practice for using public transportation [Citation16]. They categorized the contents of the assessments into four categories consisting of 22 items. In their study, they pointed out that there was no objective/comprehensive assessment tool for assessing patient performance and judging the effectiveness of using public transportation practice, even though there were many components to be assessed during practice [Citation16].

For professionals in rehabilitation practice, a comprehensive assessment tool to assess the ability of public transportation use in clinical settings is necessary to identify specific problems of using public transportation and to plan appropriate interventions. The aim of this study was to develop the Public Transportation use Assessment Form (PTAF), which could assess the actual performance of a series of tasks in public transportation use, especially train and bus, by direct observation for stroke survivors in clinical setting. Specifically, we aimed: (1) to identify the items for development of a tentative assessment form from problems found in previous training for public transportation and (2) to develop the final version of the PTAF through content validation.

Materials and methods

Study setting

The study was conducted at a 160-bed subacute rehabilitation hospital in Japan where medical insurance paid for the rehabilitation of stoke patients who were admitted to the wards within 2 months of onset and up to 6 months after hospitalization [Citation17]. The hospital is located in Narashino city (total population of 169 000 people in January 2016 [Citation18] in northwestern Chiba prefecture, which is adjacent to the Japanese capital, Tokyo. It takes about 30–40 min to get to Tokyo by train, and the trip is most frequently made by car (34%) followed by train (27%) in this area [Citation19]. In the hospital, trainings for public transportation use have been conducted during hospitalization according to the patients’ needs. The number of daily passengers at each station used in the training for using public transportation in the present study ranged from 11 000−137 000 [Citation20,Citation21].

The study protocol was approved by the ethics review committee at Tokyo Bay Rehabilitation Hospital (approval number: 149 169). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the study.

Study outline

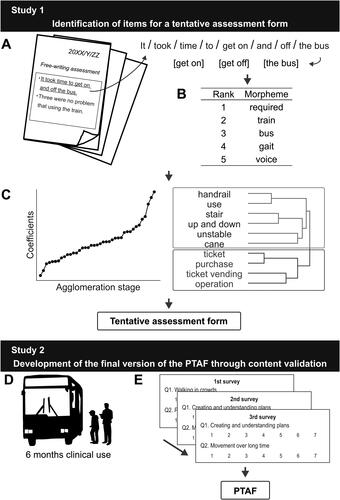

The PTAF was developed to assess the actual performance of a series of tasks in public transportation use by direct observation of stroke survivors in a clinical setting. In the present study, we aimed to define the framework of the scale, pool the potential items, and examine the items by experts’ reviews [Citation22]. Specifically, the PTAF was developed in two steps as shown in . In study 1, there was no framework regarding performance of public transportation use to pool the items and develop a tentative assessment form; thus, we performed a retrospective hierarchical clustering analysis of data from previously conducted trainings for public transportation. In study 2, after some items were added based on 6 months of clinical use of the tentative form, the final version of the PTAF was developed through content validation using multiple surveys according to the Delphi method and [Citation23] based on the Classical Test theory.

Figure 1. Study outline. (A) The difficulties or problems encountered during training for public transportation use were extracted from previous records. (B) The top 100 frequently used morphemes were extracted. (C) After a hierarchical clustering analysis, we considered the combination of distance coefficients and the contents of the cluster for determining the number of clusters. (D) Some items were added after the tentative assessment form was used for 6 months in a clinical setting. (E) We examined the appropriateness of the form using multiple questionnaires according to the Delphi method.

Study 1: Identification of items for a tentative assessment form

Participants

Data from 76 patients with stroke who were admitted to the hospital from April 2015 and March 2016 and had attended training for public transportation use, which were conducted as a part of routine care during hospitalization, were retrospectively collected. Participants who were relatively young and had a high degree of independence in daily life activities were recruited (Supplemental material 1). The field trainings were conducted by 37 physical therapists (experience in stroke survivor care, 5 months to 18.5 years; median, 2 years), 30 occupational therapists (experience in stroke survivor care, 2 months to 11.5 years; median, 2 years), and 1 speech language therapist (experience in stroke survivor care, 8 years and 11 months). Interpretation of the results and analyses was conducted among four authors (two occupational therapists [KU, SK], a physical therapist [SI], and a physiatrist [YO]).

Data analyses for item generation

To broadly extract and pool the items of the tentative assessment form, we retrospectively analyzed the text data regarding the difficulties and/or problems encountered during trainings of public transportation use. The training sessions were conducted with a therapist(s), and the type of transportation was chosen from the following: only train, only bus, and both train and bus. To plan the rehabilitation program and share information with the patient’s caregivers or other supporters after discharge from the hospital, the therapist(s) who accompanied the patient prepared a free-written record after training that consisted of the training content, difficulties and/or problems during training, and an evaluation of the patients’ ability to use public transportation.

Text-based data were analyzed by the text mining method using KH Coder [Citation24,Citation25] (). After extracting the top 100 frequently used morphemes (), we replaced the synonyms with a single morpheme and deleted the nonspecific morphemes based on discussions among four authors (KU, YO, SK, and SI). A morpheme is the smallest meaningful linguistic unit of a language. To understand the context in which these morphemes were frequently used, a hierarchical clustering analysis was performed using Ward’s method [Citation26] with Jaccard coefficients. For this analysis, we included the morphemes that appeared 10 times or more in the records. Ward’s method is an agglomerative clustering method that minimizes the sum of squares within two elements that combine in the process of consisting cluster in stage. The number of clusters to be adopted was determined by the combination of distance coefficients (dissimilarity: 1-Jaccard coefficient) and the contents of the clusters. First, we identified the number of clusters where the distance coefficients jumped, namely where the dissimilar items were clustered. From that number, we increased the number of clusters one-by-one until we found the best number where each cluster conceptually represented one task (). After the analysis, the name of each cluster was determined based on the contents expressed by the morphemes in the clusters.

Development of a tentative assessment form

Based on derived clusters, items for a tentative assessment form were determined through discussion among four authors (KU, YO, SK, and SI). Based on a scoring system of assessment form to assess actual performance by direct observation of the series of transferring and toileting task [Citation27,Citation28], we adopted the following scoring system: 3, independent (patient can complete the task without requiring any help by therapists); 2, requires supervision or verbal assistance (patient is able to complete the task with supervision or needs verbal assistance by therapists); 1, requires assistance (therapists needs to physically assist the patient’s body or therapists needs to manipulate equipment to complete the task); and N, not applicable (the participant does not perform the task; for example, items in category of “using trains” are not applicable to those who use only bus). The total score was calculated by dividing the total score by the number of items (excluding the items marked as not applicable [N]).

Study 2: Development of the final version of the PTAF through content validation

After using the tentative assessment form in clinical settings for 6 months (), the four authors (KU, YO, SK, and SI) discussed additional difficulties or problems that were not included in the tentative form but observed in field-based training sessions and thus, some more items were added. Then, the appropriateness of the PTAF was examined by multiple surveys using the Delphi method ().

Participants

All rehabilitation staff in the hospital who conducted assessment and intervention related to the use of public transportation in clinical setting was included. Seventy-one therapists (experience in stroke survivor care, 2 years and 2 months to 30 years and 2 months; median, 4 years) who had been working at the hospital for more than 2 years and had experience with training for public transportation use responded to the questionnaire. Among them, 34 were physical therapists, 32 were occupational therapists, and five were speech language therapists. Interpretation of the results and analyses was done among three authors (KU, YO, and SK).

Data collection and analysis

To select items that could assess the actual performance of a series of tasks in public transportation use through direct observation by professionals in clinical settings, we adopted the Delphi method [Citation23], which is one of the methods to summarize the opinions of professionals and obtain consensus. Each item of the PTAF was evaluated according to whether the assessment was able to (1) be used as a measure to verify the degree of independence of the public transportation use, (2) clarify the specific problem of training for public transportation use, and (3) help in planning a better rehabilitation program.

The appropriateness of each item of the assessment form was evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale in the first questionnaire-based survey, as follows: 5, very necessary; 4, mostly necessary; 3, neither necessary nor not necessary; 2, almost not necessary; and 1, not necessary at all. The results of the first questionnaire suggested that the results of the responses were less variable and did not adequately reflect the intentions of the respondents, as most respondents chose 5 (very necessary) or 4 (mostly necessary). Therefore a 7-point Likert scale was used in the second or subsequent questionnaire-based surveys, as follows: 7, very necessary; 6, mostly necessary; 5, slightly necessary, 4, neither necessary nor not necessary, 3, slightly not necessary; 2, almost not necessary; 1, not necessary at all. In addition, all responders were asked to describe the reason when they answered “3: neither necessary nor not necessary” (in the second or subsequent questionnaires, “4: neither necessary nor not necessary”) or less. The forms were revised based on the results of the questionnaires. An item was included if ≥70% of the participants considered it as very necessary or mostly necessary. All items were either revised or deleted if less than 70% of the participants considered it as very necessary or mostly necessary.

A second or subsequent questionnaire-based survey assessed the appropriateness of the forms that had been corrected based on the previous survey. During the second or subsequent survey, the scores of the preceding survey were presented. The questionnaire surveys were repeated until ≥70% of the participants responded to all items as very necessary or mostly necessary and if the opinions for corrections and additional items had converged. Therefore, we did not determine the rounds of the questionnaire surveys priorly. Based on the results of all surveys, three authors (KU, YO, and SK) examined the suitability of each item and finalized the content of the form.

In addition, we developed the English version of the PTAF to increase the versatility of the form, by translation from Japanese to English according to the COSMIN checklist [Citation29]. Forward translation (from Japanese to English) was performed by two independent native English speakers who were fluent in Japanese, and three authors (KU, YO, and SK) compared the two translations and integrated it into one. Back translation (from English to Japanese) was performed by two independent native Japanese speakers who were fluent in English, and the above authors verified the equivalence of the original and translated versions. All translations were performed by professional translators.

Results

Study 1: Identification of item for a tentative assessment form

A total of 233 sentences that included a description of the difficulty or problem encountered in the field-based training sessions were obtained from the records of 76 patients. Finally, 41 morphemes occurring 10 times, or more were extracted. After the hierarchical cluster analysis, seven clusters were derived based on the generated dendrogram (Supplemental material 2). and changes of the distance coefficient (Supplemental material 3), and the name for each cluster was determined ().

Table 1. Derived seven clusters and the morphemes for each cluster.

Based on the seven derived clusters, 11 assessment items were determined from the discussion among four authors (KU, YO, SK, and SI); a tentative assessment form was developed using three categories: “mobility,” “going up and down steps,” and “paying the bus or train fare” ().

Table 2. Assessment items of the tentative assessment form.

Study 2: Development of the final version of the PTAF through content validation

Four items, namely, “movement in trains and buses,” “creating and understanding plans,” “checking the electric bulletin board,” and “selecting platform and bus stop,” were added to the form based on the difficulties and/or problems newly identified during the 6 months use of the tentative form.

In the validation process by the Delphi method, a total of three surveys with questionnaires were conducted. The response rate was 100% for all three surveys. shows the proportion of positive responses for each item in the three surveys, and shows the contents of additional comments.

Table 3. Percentages of responses for each item in the questionnaires.

Table 4. Additional comments in the questionnaires.

Round 1

In the first survey, all items satisfied the consensus criteria (≥70% of participants scored 4 or 5 for each item). However, there were many opinions as additional comments. Especially, several responders commented that it was difficult to identify the category or item corresponding to the behavior observed as a difficulty or problem. Some items can be grouped as a concept but cannot be grouped as a task while using public transportation. Therefore, we reorganized the items into new categories, “plan for going out,” “mobility,” “using trains,” and “using buses,” that were more suitable for the assessment of actual procedures in public transportation use. Accordingly, items such as getting on and off trains and buses, which were grouped in the tentative assessment form, were separated and included both in “using trains” and “using buses.” In addition, there were many opinions that it was necessary to add the example of the tasks. For example, there was an opinion that “when assessment walking in crowds, it is necessary to judge whether the patient could pay attention to the surrounding people or not.” Therefore, items that show similar tasks were integrated, and the examples were added in each item. For example, the items “operating ticket machines,” “checking fare,” “buying ticket,” “charging IC card,” and “asking station staff” were included as “examples.” In the above process, items “checking fare” and “readying fare” were removed from the items and included in the “examples” of “operating ticket machines” and “paying fares,” respectively. For the item of “checking the electric bulletin board,” there were opinions that it is hard to understand what “the electric bulletin board” indicates. Therefore, the item was replaced with the purpose of the task, “selecting departure time and platform,” and “checking timetables and information displays” was listed as an example. Furthermore, there were opinions that it is necessary to assess “communication with bus drivers and station staffs,” “dealing with troubles,” and “carrying luggage;” all of which were added to the assessment form.

Round 2

In the second survey, items that did not satisfy the consensus criteria were “carrying luggage (65%),” “operating ticket machines (68%),” “dealing with troubles (60%),” and “communication with bus drivers and station staffs (56%).” The item “carrying luggage” was removed, because there were many opinions that this item was not a specific task for the use of public transportation. The item “dealing with troubles” and “communication with bus drivers and station staffs” were also removed, because there were many opinions that it is difficult to assess these tasks, and they are difficult to reproduce as the scene for the training. On the contrary, although “operating ticket machines” did not satisfy the consensus criteria, the item was generated as a category in the hierarchical cluster analysis described above and minimally required task for using public transportation use. Therefore, we decided that the item should be reevaluated. With respect to the other items, some descriptions in the examples were modified based on the responses in the questionnaire.

Round 3

In the third survey, all 14 items satisfied the consensus criteria. Furthermore, to increase the versatility of the assessment form, an item of “other problems observed” was added in addition to the items satisfied by the consensus criteria; the item can be used to describe additional problems found during training. The PTAF, was finally developed with four categories (plan for going out, mobility, using trains, and using buses) including 15 items (14 items and “other problems observed”). The English version is shown in (original Japanese version is in Supplementary material 4 ). We adopted the same scoring system as the in tentative form: 3, independent; 2, requires supervision or verbal assistance; 1, requires assistance; and N, not applicable.

Discussion

This study aimed to develop the PTAF that could assess actual performance of public transportation use for stroke survivors. Initially, by pooling potential items of the PTAF, we analyzed the difficulties and/or problems identified during training for public transportation use by text mining, and we developed the tentative assessment form. After 6 months of clinical use of the tentative assessment form, we verified its content validity using the Delphi method. The results show that the PTAF was found to have good content validity.

Seven clusters were generated by the hierarchical clustering analysis using text data of field-based training for public transportation use. The clusters “going up and down stairs,” “using escalators,” and “getting on and off trains and buses” are related to tasks of going up and down stairs and steps. Getting on and off trains and buses are difficult tasks because they involve going up and down stairs, which are known to be difficult tasks for stroke survivors [Citation30,Citation31]. This was consistent with findings in previous reports that listed getting on and off as a common difficulty for public transportation use [Citation7,Citation11]. The clusters “buying ticket” and “paying fares” are related to tasks of paying the bus or train fare. This is consistent with findings in previous reports that buying and/or booking tickets and finding ticket machines were difficult tasks for public transportation use [Citation7,Citation11]. These tasks may reflect difficulties in manipulating a wallet due to post-stroke motor impairments, such as hemiparesis, or in using the machine and calculating the money due to cognitive impairments, such as aphasia and unilateral spatial neglect. The cluster, “consideration of surroundings in crowds,” is a task requiring appropriate attention to the surroundings. As evident in the fact that dual-task related gate performance decreases in stroke survivors compared with healthy subjects [Citation32], this category may be difficult for stroke survivors with attentional deficits. The cluster “passing through ticket gates” requires smooth execution of tasks in a stream of other people and is difficult for stroke survivors with decreased gait speed. Thus, the above seven clusters were difficult for stroke survivors and tended to be raised as problems in training for public transportation use.

Among the 14 items in the PTAF, all but “creating and understanding plans,” were consistent with the questionnaire-based study by Sawada et al. [Citation16]. The 13 common items comprise difficult tasks commonly found in various situations when stroke survivors use public transportation and are considered to be highly valid in identifying tasks for training. It was reported that “the planning trip in advance” was one of the facilitators for stroke survivors with cognitive limitation to traveling with public transportation and creating a plan before going out decreased participants’ feelings of stress [Citation33] Many stroke survivors present with post-stroke cognitive impairment [Citation34]. Therefore, contrary to the results of a previous study, we believe that the item "creating and understanding plans," is an important task to be assessed in stroke patients’ use of public transportation and is a suitable item for the PTAF. In this study, the items of the PTAF were determined through multiple surveys of experts using the Delphi method. The experts’ review of items is considered practical for enhancing content validity [Citation22]. By repeatedly modifying the items in this study until a consensus was reached among the experts, we believe that the PTAF has been developed with a good content validity to assess the actual performance of a series of public transportation use in a clinical setting.

The PTAF includes only tasks that are clinically common and in need of assessment to increase its versatility. Therefore, the PTAF consists of fewer tasks than the number of items extracted by Sawada et al. [Citation16]. The items focused on only communication, such as “dealing with troubles” and “communication with bus drivers and station staffs,” were deleted, because the PTAF included only the tasks of frequently encountered situations when using public transportation. Of course, people may encounter various circumstances and problems when using the public transportation. However, the inclusion of various tasks for many possible situations may make the form too complex and redundant. Therefore, to make the form as concise as possible, we only included the items that comprised more frequently encountered tasks when using public transportation.

The PTAF has three strengths. Firstly, the PTAF could assess actual performance of individual task of public transportation use by direct observation. Whereas, all existing assessment tools such as the NEADL [Citation12], IADL [Citation13], and FAI [Citation14], which comprise items of public transportation use, do not allow assessors to assess the actual behavior. To the best of our knowledge, the PTAF is the first assessment tool to evaluate the actual performance of public transportation use. Secondly, the PTAF includes a series of tasks following the actual procedures in public transportation use; it consists of a number of frequently encountered tasks. There are a variety of tasks that can be difficult for stroke survivors when using public transportation [Citation7,Citation11], and the series of tasks needs to be assessed individually. The PTAF allows for individualized assessment of the tasks that comprise public transportation use in real clinical setting. Furthermore, the PTAF is an interventional measure that will help to identify which tasks are difficult and to plan a rehabilitation program based on the results. The PTAF could also share information about which tasks need support during public transportation use and could augment the hospital discharge plan. Finally, using the total score of the PTAF can quantifiably assess actual performance of public transportation use. Therefore, the PTAF could identify the degree of independence in using public transportation.

The PTAF has other possibilities. It was developed to be mainly suitable for assessing individuals with stroke. However, it could assess the actual performance by direct observation of public transportation use and possibly assess individual with other diseases. Additionally, the PTAF can identify the degree of difficulty or problem in public transportation use. Accordingly, the PTAF could also be used to identify individuals with stroke who require personal or social support and therefore, could contribute to the development of social systems and policies. The English version of the PTAF was also developed according to the COSMIN checklist. Therefore, we believe that the PTAF can be used in English-speaking areas if its reliability and validation are verified.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, the study was conducted in a single facility where the public transportation system was well developed, and the sample was limited to subacute individuals with stroke. Furthermore, the items of the PTAF developed in this study are mainly suitable for assessing individuals with stroke who can ambulate. Therefore, generalization of the results of this study should be performed with caution. Further studies will examine its validity in different regions and countries, including stroke survivors at different phases and wheelchair users. Secondly, the assessment items are pooled to focus on the frequent tasks during training for public transportation use and do not include tasks that occur less frequently. Even if the frequency of assessment is low, the tasks that occur irregularly should be assessed to ensure the safety of stroke survivors during transportation. To complement this short-coming, an assessment of the simulated tasks in different training sessions would be required in addition to the assessment with PTAF during real field trainings. Thirdly, in the field trainings, most of the assessments were performed by physical therapists and occupational therapists, and only a small number of speech language therapists were included. The perspectives from the stroke survivors themselves and their care givers are also lacking. Including various viewpoints from those people may make the form more comprehensive and patient-oriented. Finally, this study only verified the content validation. This study is part of the scale development process [Citation22], and further studies are necessary to verify its reliability and validity.

In conclusion, the PTAF was successfully developed with good content validity as an assessment tool, which can assess the actual performance of public transportation use by direct observation in a clinical setting for patients with stroke.

Supplementary material_4.pdf

Download PDF (98 KB)Supplementary material_3.pdf

Download PDF (36.7 KB)Supplementary material_2.pdf

Download PDF (38.4 KB)Supplementary material_1.pdf

Download PDF (56 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge all the participants of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. City Bureau. City Planning Division. Transportation of people and its change in metropolitan [internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001223976.pdf

- Norlander A, Iwarsson S, Jönsson A-C, et al. Living and ageing with stroke: an exploration of conditions influencing participation in social and leisure activities over 15 years. Brain Inj. 2018;32(7):858–866.

- Aufman EL, Bland MD, Barco PP, et al. Predictors of return to driving after stroke. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92(7):627–634.

- Perrier MJ, Korner-Bitensky N, Mayo NE. Patient factors associated with return to driving poststroke: findings from a multicenter cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(6):868–873.

- Finestone HM, Guo M, O’Hara P, et al. Driving and reintegration into the community in patients after stroke. Pm R. 2010;2(6):497–503.

- E.J.R. Marketing & Communications, Inc. jeki capital region and Kansai region transportation of people survey 2019. [internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.jeki.co.jp/info/files/upload/20191119/jeki移動者調査2019HP.pdf

- Asplund KS, Wallin S, Jonsson F. Use of public transport by stroke survivors with persistent disability. Scand J Disabil Res. 2012;14(4):289–299.

- Wendel K, Ståhl A, Risberg J, et al. Post-stroke functional limitations and changes in use of mode of transport. Scand J Occup Ther. 2010;17(2):162–174.

- Risser R, Iwarsson S, Ståhl A. How do people with cognitive functional limitations post-stroke manage the use of buses in local public transport? Transp Res Part F. 2012;15(2):111–118.

- Rosenkvist J, Risser R, Iwarsson S, et al. The challenge of using public transport: descriptions by people with cognitive functional limitations. J Transp Land Use. 2009;2:65–80.

- Persson HC, Selander H. Transport mobility 5 years after stroke in an urban setting. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2018;25(3):180–185.

- Nouri F, Lincoln N. An extended activities of daily living scale for stroke patients. Clin Rehabil. 1987;1(4):301–305.

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186.

- Holbrook M, Skilbeck CE. An activities index for use with stroke patients. Age Ageing. 1983;12(2):166–170.

- Logan PA, Gladman JRF, Avery A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of an occupational therapy intervention to increase outdoor mobility after stroke. BMJ. 2004;329(7479):1372–1375.

- Sawada T, Ogawa M, Miki Y, et al. Occupational therapists’ recognition of the rehabilitative methods and effects of using public transportation: analysis of free description-type questionnaires. Jpn Occup Ther Res. 2014;33:508–516. [Japanese]

- Miyai I, Sonoda S, Nagai S, et al. Results of new policies for inpatient rehabilitation coverage in Japan. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25(6):540–547.

- Chiba Prefectural Government [internet]. Report on the Chiba prefecture monthly population survey. 2015. [cited 2021 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.pref.chiba.lg.jp/toukei/toukeidata/joujuu/nenpou/2015/documents/nenpou_2015_2.pdf

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism [internet]. Kanto Regional Development Bureau. Result of survey of Tokyo metropolitan area personal trip. [cited 2021 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.tokyo-pt.jp/static/hp/file/press/1127press.pdf

- Keisei Electric Railway Co, L [internet]. The daily ridership at the stations. 2019 [cited 2020 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.keisei.co.jp/keisei/tetudou/2019_ks_joukou.pdf

- Company E.J.R [internet]. The daily ridership at the stations. 2019 [cited 2020 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.jreast.co.jp/passenger/2019_01.html

- DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications (4th ed.). Newbury Park California: Sage publications; 2017.

- Rubin SE. Research directions related to rehabilitation practice: a Delphi study. J Rehabil. 1998;64:19.

- Higuchi K. A two-step approach to quantitative content analysis – KH coder tutorial using anne of green gables (part I). Ritsumeikan Soc Sci Rev. 2016;52:77–90.

- Higuchi K. A two-step approach to quantitative content analysis: KH coder tutorial using anne of green gables (part 2). Ritsumeikan Soc Sci Rev. 2017;53:137–147.

- Ward JH. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J Am Stat Assoc. 1963;58(301):236–244.

- Kitamura S, Otaka Y, Murayama Y, et al. Reliability and validity of a new transfer assessment form for stroke patients. Pm R. 2021;13(3):282–288.

- Kitamura S, Otaka Y, Murayama Y, et al. Reliability and validity of a new toileting assessment form for patients with hemiparetic stroke. Pm R. 2021;13(3):289–296.

- Mokkink LB, Prinsen CA, Patrick DL. COSMIN study design checklist for patient-reported outcome measurement instruments. [cited 2021 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-study-designing-checklist_final.pdf

- Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD, et al. The structure and stability of the functional independence measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75(2):127–132.

- Tsuji T, Sonoda S, Domen K, et al. ADL structure for stroke patients in Japan based on the functional independence measure. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;74(6):432–438.

- Yang Y-R, Chen Y-C, Lee C-S, et al. Dual-task-related gait changes in individuals with stroke. Gait Posture. 2007;25(2):185–190.

- Stahl A, Lexell EM. Facilitators for travelling with local public transport among people with mild cognitive limitations after stroke. Scand J Occup Ther. 2018;25:108–118.

- Mori N, Otaka Y, Honaga K, et al. Factors associated with cognitive improvement in subacute stroke survivors. J Rehabil Med. 2021;53(8):jrm00220.