Abstract

Purpose

To assess the psychosocial outcomes of facial weakness in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD).

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional survey study. The severity of facial weakness was assessed by patients (self-reported degree of facial weakness) and by physicians (part I FSHD clinical score). Questionnaires on facial function, psychosocial well-being, functioning, pain, and fatigue were completed. Regression analyses were performed to explain variance in psychosocial outcomes by demographic and disease variables.

Results

One hundred and thirty-eight patients participated. They reported mild to moderate psychological distress, no to mild fear of negative evaluation, and moderate to good social functioning. However, patients with severe self-reported facial weakness scored lower in social functioning. Patients with more facial dysfunction experienced more fear of negative evaluation and lower social functioning. Furthermore, younger age, presence of pain, fatigue, walking difficulty, and current or previous psychological support were associated with lower psychosocial outcomes. Overall, patients report moderate to good psychosocial functioning in this study. The factors contributing to lower psychosocial functioning are diverse.

Conclusions

A multidisciplinary, personalized approach, focusing on coping with physical, emotional, and social consequences of FSHD is supposed to be helpful. Further research is needed to assess the psychosocial outcomes of facial weakness in younger patients.

Research on the psychosocial consequences of facial weakness in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is limited.

Patients with FSHD experience mild to moderate psychosocial distress, partly due to overall disease severity, such as reduced mobility, and partly due to facial weakness and reduced facial function.

Self-reported degree of facial weakness and facial dysfunction were related to lower psychosocial outcomes (social functioning, fear of negative evaluation, and psychological distress).

Physician-reported degree of facial weakness was not related to psychosocial outcomes, suggesting an absence of a strong correlation between observed facial weakness and experienced disease burden in this study.

This calls for a multidisciplinary, personalized approach with a focus on coping with physical, emotional, and social consequences of FSHD.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is a slowly progressive, heritable muscle disease that typically leads to asymmetrical weakness of facial, scapular, and humeral muscles [Citation1–5]. The first symptoms generally develop in the second decade of life. Over time, the lower extremities and pelvic girdle muscles can become affected, with 20% of the patients being wheelchair dependent at the age of 50 [Citation2,Citation4]. It is one of the most common muscular dystrophies, with a worldwide prevalence estimated between 1:15 000 and 1:50 000 [Citation2,Citation4,Citation6].

Patients with FSHD have a normal life span, but the disease can have a major impact on quality of life, due to physical and social problems, emotional distress, and diminished productivity [Citation3,Citation7–13]. This might partly be due to facial weakness, present in 75–90% of patients [Citation5,Citation14]. The assumption of facial weakness being a contributing factor of psychosocial consequences is supported by observations in other diseases. Facial paralysis due to different causes, such as Bell’s palsy and Moebius syndrome, and facial masking in Parkinson’s disease are known to lead to emotional and social difficulties, partly due to miscomprehension of facial expressions of patients with these diseases [Citation8,Citation15–23]. In particular, impairment of the ability to smile can lead to depressive symptoms [Citation24]. It is known that FSHD leads to less cheek compression strength, which is associated with communication difficulties [Citation22]. This could reduce psychosocial well-being.

However, research on the psychosocial consequences of facial weakness in FSHD is limited, and patients call for more awareness about this subject [Citation25,Citation26]. Recently, a qualitative study on the psychosocial consequences of FHSD is performed in 16 FSHD patients. Reduced facial expression affected different aspects of the participants life, which was reinforced by fatigue. Particularly the younger participants described the confrontation with reduced facial expression as upsetting. The unpredictability of the progression of facial weakness made many participants insecure and concerned. They generally tended to avoid discussing facial weakness with loved ones as well as with strangers [Citation27].

To investigate what the psychosocial outcomes of facial weakness and reduced facial function are in a large cohort of patients with FSHD, we performed a survey study on facial function and psychosocial well-being and functioning, including depression, anxiety, social appearance anxiety, and social interaction anxiety. In addition, both patients and physicians rated the severity of facial weakness. We hypothesize that patients with FSHD and facial weakness have poorer psychosocial outcomes compared with patients without facial weakness. We aim to increase awareness for the possible psychosocial consequences of facial weakness and reduced facial function in FSHD and provide a starting point for the development of a multidisciplinary personalized treatment.

Methods

Patients

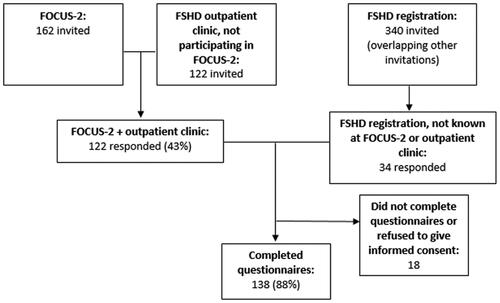

To reach a majority of all Dutch FSHD patients, we contacted three largely overlapping cohorts of patients known at the FSHD expertise center in the Netherlands by secured e-mail. First, participants in the FOCUS-2 study, an ongoing natural history-study in patients with FSHD, were invited by the research physician (n = 162) [Citation28]. Additionally, patients followed-up at the FSHD-outpatient clinic who were not participating in the FOCUS-2 study were invited by their physician (n = 122). Finally, all adult participants of the Dutch FSHD registry [Citation29] were contacted by the administrator (n = 340). Patients were allowed to fill out the questionnaires only once in case of multiple invitations. Inclusion criteria were: clinically and/or genetically confirmed FSHD, and age ≥16 years. Only completed questionnaires were analyzed. The questionnaires had been split into four parts, to allow participants to take a break and help them to fill out all questionnaires. Patients with neurological comorbidities which affect the facial muscles (e.g., Bell’s palsy or stroke with residual facial weakness) were excluded. Patient enrollment is depicted in . Participant acquisition and data collection took place between June and August 2020. Patients filled out the questionnaires and an informed consent form via a secured online program (RadQuest).

Figure 1. Participant enrollment. FOCUS-2: an ongoing natural history-study in patients with FSHD. FSHD registration: Dutch FSHD registration.

Demographic and social data

Demographic and social data (age, sex, FSDH type, time since diagnosis, change in work due to FSHD, household, and highest education level), presence of close acquaintances (family or close friends) with FSHD, and current or previous psychological support were collected.

Severity of FSHD and of facial weakness

Self-reported overall FSHD severity

To roughly assess the severity of FSHD, patients were asked if they were able to lift their arms above the shoulders and if they could walk without a helping aid. Answer options of both questions were “able”, “able with extra effort or aid”, and “unable”.

Facial weakness severity

To assess the severity of facial weakness, patients were first asked if they had any symptoms of facial weakness in general (e.g., difficulty with closing eyes, pouting lips or puffing cheeks). The answer options were “no facial weakness”, “mild facial weakness”, and “severe facial weakness” (referred to as “self-reported degree of facial weakness”). Next, a physician-reported facial weakness score was available from the patients who participated in the FOCUS-2 study. This score is extracted from the FSHD clinical score [Citation30]. Outcomes were “no facial weakness”, “mild facial weakness”, and “severe facial weakness” (referred to as “physician-reported degree of facial weakness”). Finally, we assessed facial function, using different questionnaires.

Questionnaires

The questionnaires are summarized in . They focus on facial function, psychosocial well-being and functioning, pain and fatigue.

Table 1. Used questionnaires.

Questionnaires on facial function

We assessed facial function using different questionnaires: the FSHD Rasch-built overall disability scale (FSHD-RODS) [Citation31], Facial Clinimetric Evaluation scale (FaCE) [Citation32], and Facial Disability Index (FDI) [Citation33].

Questionnaires on psychosocial functioning

Several domains of psychosocial functioning were assessed: psychological distress (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [Citation34]), depressive symptoms and anxiety (HADS subscales), emotional well-being and role limitations due to emotional problems (Research and Development-36 (RAND-36) [Citation35]), fear of negative evaluation of appearance (Social Appearance Anxiety Scale (SAAS) [Citation36]), social interaction anxiety (Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) [Citation37]), and social functioning, for instance, social withdrawal or adapted social behavior due to FSHD (FaCE [Citation32]).

Questionnaires on pain and fatigue

To assess pain severity, we used the pain subscore of the RAND-36 questionnaire [Citation35]. Fatigue severity was assessed by the fatigue subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS-fatigue) [Citation38].

Comparison with pre-COVID psychosocial functioning

We conducted this study during the COVID-19 pandemic (May–July 2020). This could have influenced the psychosocial outcomes of the patients. To assess this, we compared the scores on the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care (BDI-PC) completed by participants of the Dutch FSHD registry before and during the outbreak. Surveys completed between the start of 2019 and mid-February 2020 were considered to be pre-pandemic and those completed between mid-February and July 2020 were considered to be during the pandemic. In addition, patients were asked if they thought their psychosocial functioning was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (Armonk, NY). Scores on most outcomes were not normally distributed (skewness >1; kurtosis >1; significant test of normality) and therefore non-parametric tests were used.

Descriptive statistics

Scores were given as mean with standard deviation. In the absence of validated cut-off scores, the outcomes of the SAAS questionnaire, SIAS questionnaire, FaCE subscores, FSHD-RODS, FDI, and two of the RAND-36 subscores were further analyzed by the frequencies of patients who scored the highest and lowest 10% of the possible questionnaire outcomes. Kruskal–Wallis tests and post hoc Bonferroni’s analysis were used to compare psychosocial outcomes between patients with no, mild, and severe facial weakness, using the self-reported facial weakness score and the physician-reported facial weakness score. Correlations between psychosocial outcomes and facial dysfunction were analyzed using Spearman’s rho correlations. Values of p < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Regression analysis

To assess the association between demographic and disease variables and psychosocial functioning, different linear regression analyses were performed with psychological distress (HADS), fear of negative evaluation (SAAS), and social functioning (FaCE subscore) as dependent variables. Independent variables were based on previous research and information of patients visiting the FSHD outpatient clinic, taking into account overlap in questionnaires: sex, age, living alone or accompanied, diagnosed acquaintances (close friends or family diagnosed with FSHD), current or previous psychological help, change in work, pain, fatigue, possibility to raise arms and to walk, and the different aspects of facial weakness (self-reported facial weakness, facial function as assessed in the FaCE and FDI questionnaires, and physician-reported facial weakness). Prior to running the regression analyses, the final set of independent variables for each of the three regression analyses was defined, based on significant correlations between independent and dependent variables, using Spearman’s rho correlations. Missing scores of the clinical facial weakness score were replaced with the mean clinical score.

Results

Patients, demographic, and social data

Of the contacted patients, 156 responded through one of the three routes of recruitment: 138 patients consented with participation and completed all questionnaires; 18 patients did not return their consent form or had not completed all questionnaires (). Demographics are presented in . Ninety-eight percent of the participants were Dutch.

Table 2. Demographics and social data.

Of the participating patients, 41% had received psychological support from different health care professionals in the past or at the time of study participation. Psychological support was initiated mostly for issues not related to facial weakness, but to other aspects of FSHD or general psychological difficulties.

Severity of FSHD and of facial weakness

Self-reported severity of FSHD, self-reported facial weakness and physician-reported facial weakness are presented in . Regarding self-reported FSHD severity, half of the patients (51%) was not able to lift their arms above the shoulders and 41% was not able to walk without helping aid. One in 10 patients (10%) was wheelchair bound. Almost half of the patients (47%) reported mild facial weakness, and approximately one in six patients (17%) reported severe facial weakness. The physician-reported facial weakness score was available in 64 patients enrolled in the FOCUS-2 study. This score was in 34% comparable to the self-reported facial weakness score; in the other patients, the physician reported more severe facial weakness.

Table 3. Severity of FSHD and facial weakness, facial function, pain, and fatigue.

Facial function

Scores of the facial function questionnaires are presented in . Most patients had moderate to good outcomes on the facial function questionnaires. Outcomes in the facial movement-domain, containing questions about the ability to smile, raise eyebrows and pout lips, were less positive: almost 11% of the patients scored in the range of the most negative 10% of the possible questionnaire outcomes.

Pain and fatigue

Results on the pain and fatigue subdomains are summarized in . None of the patients scored the most negative outcomes of the pain subscale. Not all patients suffered from fatigue, but it was a common symptom. Severe experienced fatigue was present in 5% of the patients.

Psychosocial functioning

Outcomes of psychosocial functioning are listed in . Overall, the psychosocial outcomes were moderate to good. Of the patients, 41% experienced psychological distress, and 22% reported feelings of depression or anxiety. Eighteen patients (13%) scored above the cut-off score in both the depression and the anxiety subscale. For emotional well-being scores were moderate to good. This was also seen on other questionnaires, with only a few patients (0–1%) having outcomes in the most negative 10% of the possible questionnaire outcomes.

Table 4. Psychosocial outcomes.

Comparison with psychosocial functioning before the COVID-19 pandemic

Depression scores from the FSHD registry before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were available for 86 patients. The depression scores from the FSHD registry showed no difference: the rate of depressive feelings before mid-February 2020 was 12%; from February 2020 onwards it was 13%, with 9% of the patients reporting depressive feelings in the pre-pandemic period as well as during the pandemic. In this study, 55% of the patients stated their psychosocial well-being was not affected positively or negatively by the COVID-19 pandemic, 35% stated their psychosocial well-being was minimally affected, 6% stated it was moderately affected, and 4% stated their psychosocial well-being was much or very much affected. During the pandemic and consequent governmental regulations, the amount of social contacts was affected in 36% of the patients, and daily life was affected in 20%. The degree of sadness and anxiety, and working status were each affected in less than 15% of the patients.

Correlations between psychosocial functioning, facial weakness, and facial function

Psychosocial functioning for patients with different degrees of facial weakness is presented in , including correlations between degree of facial weakness and facial function and scores on the psychosocial functioning questionnaires. Patients who reported severe facial weakness scored significantly lower in social functioning (FaCE) than patients reporting no or mild self-reported facial weakness, and patients reporting severe facial weakness scored significantly higher in fear of negative evaluation (SAAS). Differences in emotional well-being were not statistically significant. There were no significant differences in psychosocial outcomes between the groups with no, mild, and severe facial weakness as reported by the physician. Significant correlations were found between all the scores on the used psychosocial questionnaires and the FSHD-RODS, as well as the psychosocial outcomes and the FDI. The Facial Comfort subscore, containing questions about tiredness and painfulness of the face, also correlated significantly with all psychosocial outcomes; patients with lower facial comfort had mostly poorer psychosocial outcomes. Correlations were also found between the Lacrimal Control subscore and emotional well-being (RAND-36) and the SAAS, and between the Eye Comfort subscore and emotional distress, depression and anxiety (HADS). Fear of negative evaluation (SAAS) was mild to moderately correlated to all different facial function-scores.

Table 5. Correlations between facial weakness and facial function, and psychosocial outcomes.

Regression analysis of disease type and severity and demographic variables and psychosocial functioning

Three linear regression analyses were performed, based on significant correlations between independent and dependent variables. Neither self-reported nor physician-reported degree of facial weakness were significant factors for any of the three dependent variables. Facial function was only a significant determinant in social functioning.

Social functioning

For the model with social functioning (FaCE scale, subscore social function) as dependent variable, independent variables were: presence of close acquaintances (family or close friends) with FSHD (yes/no), change in work due to FSHD (yes/no), overall FSHD severity (ability to raise arms and ability to walk); self-reported and physician-reported degree of facial weakness (no, mild, or severe); facial function (FaCE subscales facial movement, oral function, eye comfort, lacrimal control, and facial comfort, and FDI); pain (RAND-36, subscale pain); and fatigue (CIS fatigue). The final model was statistically significant, and variance explained (R2) was 59%. Different facial function dimensions were statistically significant factors: facial comfort (including tension or tiredness of the face, β 0.616), eye comfort (including dry or irritated eyes, β − 0.374), facial movement (including the ability to smile, raise eyebrows, and pout lips, β 0.198), and pain (β 0.196). More facial dysfunction and more pain were associated with lower social functioning.

Fear of negative evaluation

For the model with fear of negative evaluation (SAAS) as dependent variable, independent variables were: age; current or previous psychological support (yes or no); overall FSHD severity (ability to raise arms and ability to walk); self-reported and physician-reported degree of facial weakness (no, mild, or severe); facial function (FaCE subscores facial movement, facial comfort, oral function, and eye comfort; FDI), and pain (RAND-36, subscale pain). The final model was statistically significant, and variance explained (R2) was 24%. Age (β − 0.195), and walking difficulty (β 0.200) were statistically significant factors. Reporting more fear of negative evaluation was associated with younger age and more severe walking difficulty.

Psychological distress

For the model with psychological distress (HADS) as dependent variable, independent variables were: change in work due to FSHD; current or previous psychological support (yes or no); facial function (FaCE subscore facial comfort; FDI), pain (RAND-36, subscale pain); and fatigue (CIS fatigue). The final model was statistically significant, and variance explained (R2) was 37%. Current or previous psychological support (β 0.241) and fatigue (β 0.481) were statistically significant factors. More fatigue, and having had psychological help currently or in the past were associated with more psychological distress.

Discussion

This survey study in a large cohort of FSHD patients showed that patients with FSHD experience mild to moderate psychosocial distress, partly due to overall disease severity, such as reduced mobility, and partly due to facial weakness and reduced facial function. Self-reported degree of facial weakness and facial dysfunction were related to lower psychosocial outcomes (social functioning, fear of negative evaluation, and psychological distress). In contrast, physician-reported degree of facial weakness was not related to these outcomes, suggesting the absence of a strong correlation between observed facial weakness and experienced disease burden. Although the general degree of psychosocial distress reported by patients was only mild to moderate, 41% of the patients reported elevated levels of distress and 22% had scores reflecting increased feelings of depression and anxiety. Scores of emotional well-being and role limitations due to emotional problems were moderate to good. Nevertheless, these scores for emotional and social well-being were lower compared to healthy populations, reflecting more distress in patients with FSHD [Citation32,Citation37,Citation39–41].

We used three approaches to assess severity of facial weakness and facial function, and estimated correlations between these measures and psychosocial outcomes. Patients with severe self-reported facial weakness scored significantly lower on social functioning. In addition, patients with more facial dysfunction had significantly more fear of negative evaluation and scored significantly lower on social functioning. This might imply that patients who report facial weakness withdraw from social situations and are afraid of negative judgments on their appearance. In contrast, there was no statistical significant correlation between the physician-reported facial weakness score and scores on psychosocial functioning. This might be related to the very rough classification (no, mild, or severe facial weakness) or the limited number of available data for this item. It could also reflect that the level of emotional and social distress does not correlate to objectively assessed facial weakness. This supports findings in other diseases that cause facial alterations, such as Bell’s palsy [Citation16], suggesting that psychosocial outcomes could be improved not only by focusing on the facial muscle structure and function, but also on psychosocial support.

Reduced facial function and pain are associated with poorer outcomes in social functioning (e.g., withdrawal from social situations). Furthermore, more fatigue and current or previous psychological support are associated with a poorer psychological health, and younger age and more walking difficulty are associated with more fear of negative evaluation. This is in line with our recent qualitative study, in which patients retrospectively reported a larger psychosocial burden in younger age [Citation27].

Some patients might not be aware of the effect of facial weakness, experience the other features of FSHD as more debilitating, or both. First, the discrepancy between the self-reported degree of facial weakness and physician-reported degree of facial weakness suggest that some patients do not experience their facial weakness as severe as the physician reports [Citation42]. Furthermore, patients who had psychological support currently or in the past reported that this was not due to facial weakness or reduced facial function. However, the effect of this aspect of FSHD may be underestimated, for instance, when a patient is unaware of facial weakness while others alter their behavior toward him or her because of this altered facial appearance. This is supported by our data, wherein the physician scores facial weakness as more pronounced than patients. The inability to smile is shown to be a major cause of psychosocial problems in facial palsy [Citation19,Citation24].

Psychosocial outcomes in this study were generally lower compared to healthy populations, but similar with or slightly better than in Bell’s palsy [Citation17,Citation40], facial palsy [Citation43,Citation44], limb-girdle muscular dystrophy [Citation45], and limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis [Citation46,Citation47]. This suggests that FSHD leads to psychosocial distress, but not as much as in other chronic diseases causing facial alterations. This might be related to the early onset and very slow progression of FSHD: the first symptoms of FSHD often occur early in life, while disease manifestation in other diseases could occur later on and with an acute or subacute onset. Hence, patients with FSHD are likely to learn to handle the consequences of their disease, possibly supported by older, affected family members. This hypothesis is supported by our data, showing that older patients report less social anxiety and have better social functioning. This is, however, not specific for FSHD: older patients generally have a more settled social life, while younger patients have to develop their social environment. At the same time, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy most of the time starts early in life span as well, and has more negative psychosocial outcomes than FSHD [Citation45], and the SAAS score for fear of negative evaluation is almost equal with the score of patients with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis, which is an acquired disease [Citation47]. This suggests age of onset is not the only factor explaining the difference in psychosocial outcomes between these diseases.

This survey study also sheds light on other contributors of psychosocial well-being. Pain and fatigue, which are common symptoms in FSHD [Citation7], were found to reduce psychosocial well-being. This confirms previous findings: pain leads to poorer social functioning [Citation12], and fatigue is a predictor for poorer mental well-being [Citation9,Citation12]. Furthermore, difficulty with walking is a major limitation [Citation10,Citation11] and a predictor for poorer social functioning. Sex was not a predictive factor in this study, however in literature, it is stated that women tend to have more facial palsy-related psychosocial dysfunction than men [Citation17].

Due to the variety in recruitment strategies, we consider the outcomes to be generalizable to the Dutch population, although we did not ask for ethnic background. A limitation of this study is the participation bias inherent to voluntary participation and recruitment among the cohorts that have sought medical attention before. Due to the amount of questionnaires, more severely affected patients might have renounced participation. To overcome this barrier, the questionnaires were split in four parts which could be filled in at different moments. Next, data of physician-reported degree of facial weakness were only available for the participants that also participate in the natural history study in our center. Therefore, drawing conclusions from these data should be done with caution.

Furthermore, only few participants were younger than 30 years old. External validity might therefore be limited, especially in younger patients. More research needs to be done to assess the psychosocial outcomes of facial weakness in younger patients. Finally, the influence of others’ reactions is not taken into account in this study and could be assessed to be aware of the impact of these reactions and to help patients to be able to alter these reactions or to respond them in a helpful way.

Based on research in Moebius syndrome, we propose that the first step to improve the psychosocial outcomes in FSHD patients is to acknowledge and recognize the consequences of facial weakness and reduced facial function by both the patient and the clinician [Citation15,Citation48]. This is supported by our recent qualitative study [Citation27]. Next, a multidisciplinary approach to diminish the negative effects of facial dysfunction, pain, fatigue, and walking difficulties is recommended. It is assumed this could be especially helpful for patients more prone to negative psychosocial outcomes, such as patients with more facial dysfunction, more pain, fatigue, and walking difficulty, younger patients and patients who had had current or previous psychological support. Therapy should focus on coping with the physical, emotional, and social consequences of FSHD, and social skills to handle reactions of others. Speech therapy might improve facial function, similarly as in Parkinson’s disease [Citation49]. The applicability of muscle transplantation in FSHD has not yet been assessed [Citation50,Citation51]. Patients can be informed that, with aging, the impact of social consequences of facial dysfunction are likely to reduce. Finally, there is a role for the community to fully accept patients who look or act different and to broaden the norms, for instance by educational programs at schools [Citation52]. Patients may use other strategies to express themselves, compensate with gestures and variations in the tones of their voice, and help others by being open about their disease [Citation15].

In short, this study has shown that psychosocial outcome in patients with FSHD is moderate to good. However, some patients are more prone to poorer psychosocial outcomes than others. Facial dysfunction, but not objectively assessed facial weakness, correlates with poorer psychosocial outcomes. It is essential that these symptoms are acknowledged and that a multidisciplinary approach with a focus on handling physical, emotional, and social aspects will be developed.

Author contributions

W.A. van de Geest-Buit, MD: study design; participant acquisition; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript drafting. N.B. Rasing, MD: study design; data interpretation; manuscript revision. J.A.E. Custers, PhD: study design; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript revision; study supervision. N.C. Voermans, MD, PhD: study design; participant acquisition; data interpretation; manuscript revision; study supervision. K. Mul, MD, PhD: study design; composing of FSHD-RODS; revision of manuscript. J.C.W. Deenen, MSc: participant acquisition via FSHD registration; assessment of psychosocial well-being before and during COVID-19 pandemic. S.C.C. Vincenten, MD: participant acquisition via FOCUS2-study; design of self-reported facial functioning score; provision of physician-reported facial weakness score; revision of manuscript. A. Lanser: review of study design, provision of information about psychosocial outcomes of FSHD. J.T. Groothuis, MD, PhD: review of study design; provision of a patient list from the FSHD outpatient clinic. B.G. van Engelen MD PhD: revision of manuscript.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Radboud university medical center in Nijmegen, The Netherlands (CMO 2020-6328). All patients gave informed consent.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the participants of the FSHD registration for participating in this study. Besides, we are grateful to S. Sezer, MD for her support in the design of this study, and H. Geurts for her support in preparing the online questionnaires. Several authors of this publication are members of the Radboudumc Center of Expertise for neuromuscular disorders (Radboud-NMD), Netherlands Neuromuscular Center (NL-NMD) and the European Reference Network for rare neuromuscular diseases (EURO-NMD). H. Geurts: providing information about RadQuest; implemented questionnaires in RadQuest; providing data codebook. S. Sezer, MD: Performing interview study in the same subject; sharing first results. Several authors of this publication are members of the Netherlands Neuromuscular Center (NL-NMD), the Radboudumc Center of Expertise for neuromuscular disorders, and the European Reference Network for rare neuromuscular diseases (EURO-NMD).

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

Anonymous data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Hamel J, Tawil R. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: update on pathogenesis and future treatments. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(4):863–871.

- Statland JM, Tawil R. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Continuum. 2016;22:1916–1931.

- Tawil R, van der Maarel S, Padberg GW, et al. 171st ENMC International Workshop: standards of care and management of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20(7):471–475.

- Tawil R, Kissel JT, Heatwole C, et al. Evidence-based guideline summary: evaluation, diagnosis, and management of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Issues Review Panel of the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Neurology. 2015;85(4):357–364.

- Banerji CRS, Cammish P, Evangelista T, et al. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy 1 patients participating in the UK FSHD registry can be subdivided into 4 patterns of self-reported symptoms. Neuromuscul Disord. 2020;30(4):315–328.

- Deenen JC, Arnts H, van der Maarel SM, et al. Population-based incidence and prevalence of facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Neurology. 2014;83(12):1056–1059.

- Smith AE, McMullen K, Jensen MP, et al. Symptom burden in persons with myotonic and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(5):387–395.

- Bakker M, Schipper K, Geurts AC, et al. It's not just physical: a qualitative study regarding the illness experiences of people with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(10):978–986.

- Schipper K, Bakker M, Abma T. Fatigue in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: a qualitative study of people's experiences. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(18):1840–1846.

- Hamel J, Johnson N, Tawil R, et al. Patient-reported symptoms in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (PRISM-FSHD). Neurology. 2019;93(12):e1180–e1192.

- Johnson NE, Quinn C, Eastwood E, et al. Patient-identified disease burden in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46(6):951–953.

- Graham CD, Rose MR, Grunfeld EA, et al. A systematic review of quality of life in adults with muscle disease. J Neurol. 2011;258(9):1581–1592.

- Padua L, Aprile I, Frusciante R, et al. Quality of life and pain in patients with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40(2):200–205.

- Loonen TGJ, Horlings CGC, Vincenten SCC, et al. Characterizing the face in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. J Neurol. 2021;268(4):1342–1350.

- Bogart KR, Tickle-Degnen L, Joffe MS. Social interaction experiences of adults with Moebius syndrome: a focus group. J Health Psychol. 2012;17(8):1212–1222.

- Bradbury E. Meeting the psychological needs of patients with facial disfigurement. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50(3):193–196.

- Bylund N, Hultcrantz M, Jonsson L, et al. Quality of life in Bell's palsy: correlation with Sunnybrook and House–Brackmann over time. Laryngoscope. 2020;131(2):E612–E618.

- Hemmesch AR. The detrimental effects of atypical nonverbal behavior on older adults' first impressions of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Psychol Aging. 2014;29(3):521–527.

- Hotton M, Huggons E, Hamlet C, et al. The psychosocial impact of facial palsy: a systematic review. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25(3):695–727.

- Ishii LE, Nellis JC, Boahene KD, et al. The importance and psychology of facial expression. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51(6):1011–1017.

- Kim JH, Fisher LM, Reder L, et al. Speech and communicative participation in patients with facial paralysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(8):686–693.

- Mul K, Berggren KN, Sills MY, et al. Effects of weakness of orofacial muscles on swallowing and communication in FSHD. Neurology. 2019;92(9):e957–e963.

- Wootton A, Starkey NJ, Barber CC. Unmoving and unmoved: experiences and consequences of impaired non-verbal expressivity in Parkinson's patients and their spouses. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(21):2516–2527.

- VanSwearingen JM, Cohn JF, Bajaj-Luthra A. Specific impairment of smiling increases the severity of depressive symptoms in patients with facial neuromuscular disorders. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999;23(6):416–423.

- Nederland F. De Nachtmerrie van Iedere Cabaretier. YouTube; 2017. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UqOim1pbPT4

- Journalists V. I cannot smile. Linda (Dutch glossy magazine); 2018.

- Sezer S, Cup EHC, Roets-Merken LM, et al. Experiences of patients with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy with facial weakness: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;16:1–8.

- Mul K, Voermans NC, Lemmers R, et al. Phenotype–genotype relations in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy type 1. Clin Genet. 2018;94(6):521–527.

- FSHD databank en registratie. Available from: www.fshdregistratie.nl

- Lamperti C, Fabbri G, Vercelli L, et al. A standardized clinical evaluation of patients affected by facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: the FSHD clinical score. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42(2):213–217.

- Mul K, Hamadeh T, Horlings CGC, et al. The facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy Rasch-built overall disability scale (FSHD-RODS). Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(7):2339–2348.

- Kahn JB, Gliklich RE, Boyev KP, et al. Validation of a patient-graded instrument for facial nerve paralysis: the FaCE scale. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(3):387–398.

- VanSwearingen JM, Brach JS. The Facial Disability Index: reliability and validity of a disability assessment instrument for disorders of the facial neuromuscular system. Phys Ther. 1996;76(12):1288–1298.

- Spinhoven P, Ormel J, Sloekers PP, et al. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):363–370.

- Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1055–1068.

- Levinson CA, Rodebaugh TL. Validation of the Social Appearance Anxiety Scale: factor, convergent, and divergent validity. Assessment. 2011;18(3):350–356.

- Beurs dE, Tielen D, Wollmann L. The Dutch Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale: reliability, validity, and clinical utility. Psychiatry J. 2014;2014:360193.

- Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Fennis JF, et al. Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38(5):383–392.

- Crawford JR, Henry JD, Crombie C, et al. Normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001;40(4):429–434.

- Pouwels S, Beurskens CH, Kleiss IJ, et al. Assessing psychological distress in patients with facial paralysis using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(8):1066–1071.

- Zee K, Sanderman R. Het meten van de algemene gezondheidstoestand met de RAND-36. Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken, reeks meetinstrumenten; 1993. p. 1–28.

- Wohlgemuth M, Lemmers RJ, Jonker M, et al. A family-based study into penetrance in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy type 1. Neurology. 2018;91(5):e444–e454.

- Volk GF, Granitzka T, Kreysa H, et al. Nonmotor disabilities in patients with facial palsy measured by patient-reported outcome measures. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(7):1516–1523.

- Kleiss IJ, Hohman MH, Susarla SM, et al. Health-related quality of life in 794 patients with a peripheral facial palsy using the FaCE Scale: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015;40(6):651–656.

- Peric M, Peric S, Stevanovic J, et al. Quality of life in adult patients with limb-girdle muscular dystrophies. Acta Neurol Belg. 2018;118(2):243–250.

- Del Rosso A, Mikhaylova S, Baccini M, et al. In systemic sclerosis, anxiety and depression assessed by hospital anxiety depression scale are independently associated with disability and psychological factors. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:1–8.

- Mills SD, Kwakkenbos L, Carrier ME, et al. Validation of the Social Appearance Anxiety Scale in patients with systemic sclerosis: a scleroderma patient-centered intervention network cohort study. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70(10):1557–1562.

- Bogart KR, Tickle-Degnen L, Ambady N. Compensatory expressive behavior for facial paralysis: adaptation to congenital or acquired disability. Rehabil Psychol. 2012;57(1):43–51.

- Dumer AI, Oster H, McCabe D, et al. Effects of the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT(R) LOUD) on hypomimia in Parkinson's disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20(3):302–312.

- Bianchi B, Ferri A, Poddi V, et al. Facial animation with gracilis muscle transplant reinnervated via cross-face graft: does it change patients' quality of life? J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016;44(8):934–939.

- Bradbury ET, Simons W, Sanders R. Psychological and social factors in reconstructive surgery for hemi-facial palsy. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59(3):272–278.

- Stichting Eigen Gezicht. Web page of a Dutch foundation, set up for people with an altered appearance. Includes an education program for elementary schools; 2020. Available from: https://eigengezicht.nl/