Abstract

Purpose

There is a lack of knowledge about interprofessional rehabilitation for culturally diverse patients with chronic pain. This study explores experiences of healthcare professionals developing and working with rehabilitation with patients in need of an interpreter and their experience of working with interpreters.

Methods

Twelve healthcare professionals at two Swedish specialist rehabilitation centres were interviewed. Grounded theory principles were used for the data collection and analysis.

Results

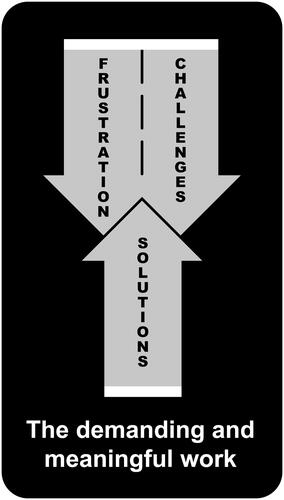

The main category "Demanding and Meaningful Work" represents three concurrently interacting categories: “Frustration” includes the informants’ doubts regarding the benefits of the rehabilitation, lack of care for patients and cultural dissonance between professionals and patients. "Challenges" describes problems in the rehabilitation work due to the need for interpreted mediated communication, the complexity in health status and social aspects among the patients. "Solutions" represents practical working methods and personal approaches developed by the informants for managing frustrations and challenges.

Conclusions

The informants’ frustration and challenges when working with a new group of patients, vulnerable and different in their preconceptions, led to new solutions in working methods and approaches. When starting a pain rehabilitation programme for culturally diverse patients, it is important to consider the rehabilitation team’s need for additional time and support.

Healthcare professionals who encounter immigrants with chronic pain need resources to develop their own skills in order to handle complex ethical questions as the patients represent a vulnerable patient group with many low status identities

In order to adapt rehabilitation programmes to patient groups with different languages and pre-understandings of chronic pain, there is a need for a team with specific qualities, i.e., close cooperation, an innovative atmosphere, time and also support from experts

For appropriate language interpretation it is important to have a professional interpreter and a healthcare professional who are aware of and adopt the rules, possibilities and restrictions of interpretation

The rehabilitation of patients in need of language interpretation needs more time and organisation compared to the rehabilitation of patients who speak the national language

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Pain is an individual experience which is affected by psychological, physical, social and existential factors [Citation1]. How pain is perceived, described and communicated differs in humans with different cultural backgrounds from different parts of the world [Citation2], including perceptions of pain control [Citation3] and treatment expectancies [Citation4].

The growth of immigration, including asylum seekers, to Western countries poses a challenge to healthcare and rehabilitation [Citation5]. The high prevalence of trauma exposure before, during and after migration puts immigrants at high risk of long-term problems with their physical and psychological health [Citation6–8], and a mutual maintenance relationship has been identified between pain and post-traumatic stress [Citation9]. Immigrants, particularily from non-Western countries, have higher levels of pain, more often musculoskeletal conditions [Citation10] and an increased risk of mental health disorders [Citation11] compared with the local population. However, immigrants have been found to be less likely than the native population to receive treatment for their pain problems [Citation12,Citation13]. Interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation (IPR) is the recommended treatment for complex chronic pain [Citation14]. In Sweden, around 20% of the patients referred to IPR at specialised pain rehabilitation centres were born abroad, but those who do not speak Swedish are often excluded from participating in IPR due to the lack of a shared language [Citation15]. In this group of patients, other factors such as treatment expectancies [Citation4] and perceptions about pain [Citation2] might also influence participation in IPR.

Few studies have been found on IPR for culturally diverse patient groups [Citation16]. One explanation for this could be that those who do not read or speak a country’s dominant language are often excluded from research studies [Citation16].

In order for pain treatment and rehabilitation to be successful, it is crucial the participants accept and engage in the therapies being offered [Citation4]. IPR usually includes group-based interventions coordinated by an interdisciplinary team, which aim to increase the participants’ knowledge of pain and increase their acceptance of pain and positive coping strategies [Citation17]. It may be difficult for patients from south-eastern Europe and the Middle East, for example, to accept and engage in these interventions since they are often accustomed to more passive, symptom-based management [Citation4,Citation18].

The lack of a shared language in IPR is another obstacle when healthcare professionals strive to increase knowledge and promote the patients’ acceptance and engagement. Here, interpreters are intended to act as a link between the patient and the caregiver. However, misunderstandings or a lack of knowledge among the interpreters could result in problems regarding the healthcare professionals’ collaboration with the patients [Citation19]. Professionalism and the right training are crucial for managing the bi-directional communication that is needed in rehabilitation interventions [Citation20].

In one of the few studies on IPR for immigrant patients, healthcare professionals were found to have experienced doubt as to whether the healthcare services had sufficient resources to cater for these patients [Citation21] and they asked for support to identify the needs of their patients with pain problems. Despite these dilemmas, research has seldom focused on the experiences of the personnel working with IPR for immigrant patients in need of interpreters [Citation21,Citation22].

The aims of the present study were to explore the experiences of healthcare professionals developing and working with IPR with patients in need of an interpreter and their experience of working with interpreters.

Methods

A qualitative approach according to the principles of grounded theory [Citation23–25] was chosen as we wanted to take part of the healthcare professionals’ subjective experiences and develop a model in order to increase our understanding. An emergent design [Citation23] was used with concurrent data collection and analysis, allowing us to adapt the interview guide to the emerging results.

Study setting

The study was conducted at two tertiary pain rehabilitation clinics in Sweden. The development of the interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation with interpreter (IPRI) programme started at one of the clinics in 2012 and at the other in 2014. The ordinary IPR programmes for Swedish-speaking patients at those clinics were not affected; they proceeded as before. The teams met to share experiences and knowledge when the IPRI programme at the second clinic started. Both teams were given supervision by professionals experienced in intercultural communication during the first year of IPRI development. The development of the programmes continued during the study period. The teams were composed of physicians, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, psychologists and social workers. One of the IPRI teams also included a nurse.

The patients had usually been referred from primary care, but some from occupational healthcare and various specialist clinics. The criteria for participation in IPRI were: 18 years of age or over, disabling chronic pain, no further medical investigation needed and a lack of ability regarding the Swedish language. Exclusion criteria were: ongoing major somatic or psychiatric disease, history of significant substance abuse and being in a state of acute crisis. The patients represented a diversity of cultural backgrounds. Most of them came from countries in eastern Europe, south-eastern Europe, western Europe, the Middle East, Asia and South America.

Before participation in IPRI was decided, the patient participated in an initial assessment by a physician together with a physiotherapist or a social worker and thereafter with other professionals. The team discussed the assessment and participation in IPRI together with the patient and a joint decision about participation was made.

The IPRI comprised two parts: (1) Introduction (group interventions over the course of 2–5 days) including information about rehabilitation and pain and starting the process of individual goal-setting.

(2) The comprehensive IPRI (2–3 days/week for 6–8 weeks) included lectures and group discussions with up to eight patients and interpreters. The programme included pain physiology, pain management psychoeducation and practical groups with physical training and occupation-based therapy. Family members were invited to specially organised information meetings in different forms: daytime and evening respectively, in groups with and without patients, and individual meetings with the patient. Weekly team conferences were performed to monitor the progress of each patient. Professional interpreters were always present during the theoretical interventions and during practical interventions when necessary.

One of the clinics included a follow-up meeting 2 months after discharge. One clinic developed videos in four languages (Turkish, Arabic, English and Farsi) with information about IPRI, pain physiology and coping strategies. The films had been published on YouTube [Citation26]. The patients watched the films during the IPRI and it was also possible to watch them at home together with their families and significant others. Information about the films was also sent to the primary care facilities in the area, as a form of support when physicians wanted to refer patients to IPRI.

Informants, data collection and analysis

Twelve healthcare professionals from the two tertiary pain rehabilitation clinics where IPRI programmes were developed were invited to participate in the study. All 12 agreed to take part. The informants were selected to represent a broad range of professions: two occupational therapists, three physiotherapists, two medical doctors, three psychologists and two social workers, all of whom had worked or were working with the IPRI programme at the time of the study.

Data were collected through thematised individual interviews from October 2016 to January 2019. The interviews lasted on average 60 min, ranging from 31 to 82 min, and were conducted at the tertiary rehabilitation clinics in Lund and Stockholm by KU and EP. EP, an occupational therapist working in Lund, performed 7 interviews in Stockholm and KU, a medical doctor working in Stockholm, performed 5 interviews in Lund, making a total of 12 interviews. KU had worked for 10 months in the IPRI team and was still working at the start of the data collection. EP had previously worked in the IPRI programme for 6 months. Both EP and KU continued to work at their respective clinics all through the data collection period but worked with other assignments. EP and KU did not report back results or reflections from the interviews to the IPRI teams during the period of interviewing so as not to affect data collection.

The interviews were conducted using an interview guide with a few broad open areas (see ). Probing questions were used when necessary, aimed at providing rich data. The initial interview guide was formed according to the important themes found in the literature and from the authors’ experience.

Table 1. The interview guide, initial and evolving areas.

The analysis started after the first interview and continued thereafter in parallel with the data collection [Citation23]. The interview guide was developed further during the data collection process according to the emerging results.

After each interview, the interviewers wrote down their thoughts and feelings about the interview and the environment of the rehabilitation setting, e.g., memos. The analysis process started when the interviewer began by listening to the recorded interview. The interviews were thereafter transcribed verbatim by the interviewer and the text was read several times in order to gain a general understanding of the material. The text was coded in the Open Code software programme [Citation27] independently by EP and KU into meaning units line by line. The emerging codes were continuously compared with previous codes and categories [Citation23]. After the first two interviews, EP, KU and ML discussed the results and the coding until consensus was reached. The discussion led to the first revision of the interview guide.

After six more interviews, the emerging results from the categories and sub-categories were discussed with the authors and two other senior researchers with extensive experience from pain rehabilitation. Based on this discussion, the interview guide was further revised in order to also gain information about how the informants had handled the interpreters’ reactions and about the informants’ experiences of how to best support patients with severe and often traumatic experiences. Categories, sub-categories and their properties were refined during the analysis process. provides examples from one of the categories.

Table 2. Example of a category with sub-categories and their properties.

During the discussions, a preliminary model was developed which was then continuously developed and refined after further discussion between the authors. The data collection ended after 12 interviews; theoretical saturation was reached in the main themes after 10 interviews and the following two interviews confirmed the previous results.

Several methods were used to ensure validity [Citation23]. Credibility [Citation23] was ensured in three ways: firstly, by prolonged engagement since two of the researchers had extensive previous experience of the investigated IPRI and working with interpreters; secondly, by the triangulation of the researchers which ensured that different perspectives from the data were explored during the analysis; and thirdly, by member checks being performed on several occasions when analytical categories, interpretations and conclusions were tested with healthcare professionals familiar with the setting and other researchers familiar with rehabilitation. Confirmability [Citation23] was ensured by taking notes during the data collection and the analytical process. Transferability [Citation23] was facilitated by an accurate description of the setting and the informants.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Stockholm Regional Ethical Review Board (registration no. 2016/858-31). The participants received written and verbal information about voluntary participation, which emphasised they could end their participation at any time without giving a reason, and they gave their written informed consent.

Results

Most of the informants were women with extensive experience of their profession (). They had worked in IPRI for approximately 2 years when the interviews were conducted. The majority of the informants had experience of working with IPR for Swedish-speaking patients before working with IPRI. Those who did not have this experience had worked with similar groups of patients, for example, in primary care or psychiatry.

Table 3. Background data for the informants, n = 12.

The analysis revealed several important aspects of the work as experienced by the informants. Three categories with subcategories emerged, which together formed the core category Demanding and Meaningful Work. The core category comprised the informants’ complex work situation: a struggle with many demanding aspects but at the same time very rewarding because of doing a deeply meaningful job and managing new and complex situations. The core category also illustrates the interaction between the three categories Frustration, Challenges and Solutions. Frustration illustrates the informants’ experiences when they encounter new or more severe aspects in their work, compared with their usual work with Swedish-speaking patients, for which there was no obvious solution. Challenges illustrates the work situation in which they had to find new approaches to enable rehabilitation. In order to meet the challenges, the informants continuously developed Solutions, which could reduce their feelings of frustration and enable them to address other challenges. Some frustrations and challenges remained unsolved.

In and below, the categories and sub-categories are described in detail with headings in italics and with quotations from the interviews.

Table 4. Categories and sub-categories included in the main category: Demanding and Meaningful Work.

“Frustration”

This category illustrates the informants’ ongoing uncertainty concerning the patients, about the benefits of the programme, the lack of resources in healthcare and in the social security system, and the cultural dissonance between professionals and patients, which all caused them frustration. There were few answers and no obvious ways to solve these issues.

The informants described how they struggled with their feelings about the benefits of the IPRI programme, even though adaptations and changes had been made:

… we need to rethink things quite a lot here. … and we did try to make changes, but I still got the feeling it wasn’t really quite working, or it wasn’t enough. I think we need something different, or something more… or something anyway. (Psychologist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants discussed whether different alternatives to the IPRI programme could be of value, e.g., some kind of social rehabilitation. They had heard about one example in which the participants worked with food catering, sewing and domestic services. Another more hypothetical alternative was thoughts about participation in the clinic’s ordinary IPR programme, on condition the patients had learned to speak Swedish before participation. This would be a way of guaranteeing equal rehabilitation (like for other Swedish-speaking patients):

… it’s a bit like learning a new type of behaviour. And in that situation it’s difficult when you’re always using an interpreter… there are so many potential sources of misunderstanding. (Medical doctor) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

On the other hand, they identified valuable aspects of the rehabilitation programme, which was due to the setting at the tertiary pain rehabilitation unit, i.e., working in interprofessional teams that possessed significant knowledge about chronic pain and pain rehabilitation.

The informants described the results they usually expect their Swedish-speaking patients to achieve during IPR: being able to shift their focus away from the pain, coming to an understanding of and starting to change unsuccessful or maladaptive behaviour. This was their standard for a successful intervention. The results achieved by this group of patients were different and the informants were uncertain whether the improvements could be judged as success. For example, it could be that a patient started to walk with walking sticks.

I think this is something that remains ingrained in some of the participants. They could learn to take public transport on their own, not always feel the need to have someone with them or take a taxi or get a lift (Occupational therapist) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

Another positive result was when they succeeded in meeting patients on equal terms and when they created an alliance. When the programme started a positive process, the patients improved in their self-esteem, cognitive presence and endurance and in daring to try new activities.

They might have felt seen and heard for the first time. And that they, (with emphasis) they are important as an individual… (Psychologist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants asked themselves if these positive but relatively minor results would lead to any changes in the long run.

The patients had large and diverse needs for coordinated care, support from healthcare and society, as well as other basic needs that became apparent, for example, regarding economic and social rights. The informants realised that the patients were not getting enough support, neither from healthcare such as primary care or specialist care such as psychiatry, nor from other stakeholders, as for example, the social services or the Public Employment Service. The situation was the same both before and after the IPRI:

Because we’ve done lots of work and they’ve seen what they need to do and where they’re headed. But if they don’t get help maintaining what they’ve achieved, they’ll slip back again. And that would be a loss at all levels. (Psychologist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

There were examples of caregivers or social services in which the activities worked very well but on some of these occasions other problems became obvious, e.g., failed coordination between the stakeholders. The informants felt that patients who did not speak Swedish were not treated equally and they thought this was very unfair. Possible explanations for this were that many caregivers and stakeholders did not work with interpreters as a part of their regular duties and also because the patients were not able to fully speak up for themselves. The lack of adequate care meant that when the patients came for rehabilitation, they were rarely ready to participate, and when the IPRI was over, there was no coordinated care that could follow up and continue the rehabilitation process.

The informants described cultural dissonance in several aspects, including the living conditions and family relations of many of the female patients and how their lack of Swedish language made the patients dependent on their children.

The informants described that many of the female patients were not used to expressing their opinions and were often both financially and socially dependent on their husbands. The patients were usually quiet and it was hard to engage them in a discussion. The female patients could become even more quiet when their husbands or a male interpreter were in the room. This affected the informants in different ways:

It’s an awful feeling when you’re uncertain… what does the patient actually want? Is this more about what I want, or what the relatives want…? (Physiotherapist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants described that the patients were holding back information from their children with the aim of protecting them. For example, the children were not always informed about the illness of a parent (patient). Parents who were divorced might also pretend that they were still married in front of their children. From the informants’ perspective, this was not the right way to treat children but when they tried to talk to the patients about it, they got no response. It was clear that their approaches were completely different.

You don’t understand my way of thinking at all, and I don’t understand yours. (Psychologist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants reasoned about why the patients had not learned Swedish. They had difficulty creating a dialogue with the patients about this, but they thought of possible explanations, for example, that it had not been possible for them to prioritise learning Swedish, that the patient had stopped studying “Swedish for Immigrants” and started to do a job where language skills were not needed, or that the patient had cognitive obstacles due to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or other reasons. Female patients often stayed at home taking care of the children.

Well, I’ve asked them, but often the answers are evasive. Like when women have been staying at home. And their kids speak Swedish but not with them. So they’ve had no need to learn it. (Medical doctor) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants described that they had discovered that sometimes the patient continued wanting to have an interpreter seemingly for reasons of safety.

Sometimes it’s as if the patient feels supported from the outside [the interpreter], that they [the patients] can communicate and are not alone and vulnerable, or sometimes the two of them form a strong bond… (Physiotherapist) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

“Challenges”

This category illustrates the informants’ working situation in which they had to find new approaches. Their usual methods were not enough or did not work when collecting information, making assessments, working with interpreters, building alliances and co-operating with the patients about their goals.

When collecting information, for example during the initial assessment, the informants were sometimes uncertain about what they would dare to ask the patients about, as well as doubting the honesty of the patients’ answers. They sometimes felt that the conversation was like two parties wanting to talk about completely different subjects:

I think they find the things we talk about so strange and want us to just talk about the pain and how to alleviate it. (Occupational therapist) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants described how the patients often did not give them the full picture about their economic or psychiatric problems. When a severe psychiatric disease or significant financial problems emerged subsequently, it became obvious that the patient had needs that prevented their rehabilitation and which needed solving first. However, at that point it was not easy to end the rehabilitation:

When somebody has come here maybe five, ten times and is very reserved, and (finally (author’s comment)) dares to open up and confide in you, and then you’ve got to say, oh, well in that case it’s not suitable for you to come here… that feels wrong as well. (Physiotherapist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants tried to make the assessment according to their usual standards but it was often difficult to anticipate which patients would manage to participate actively in the rehabilitation process. For example, the patients’ level of education did not always predict success and patients who were illiterate could also benefit from the rehabilitation programme. At the end of the IPRI, patients sometimes told the informants things about their lives that they had never told anyone before. These confidences were often very complex and could be difficult to handle both emotionally and practically due to the lack of remaining time in the IPRI and the lack of coordinated care.

The informants described difficulties in their cooperation with the patients when aiming at finding a common goal and ways of increasing the patients’ level of activity. A high rate of absence added to these problems. The informants and the patients often had different levels of knowledge and different attitudes about pain and its treatment, about the body, how to use the body and about psychological problems such as anxiety.

Many patients came to the unit with the main aim of getting rid of their pain and had great difficulty accepting a goal for handling their pain.

Some of them had been told that it (the pain) couldn’t be cured through surgery, for example. They had difficulty understanding this… in Sweden, such an advanced country, why can’t everything be fixed?…, they expect the pain to be miraculously taken away. (Medical doctor) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

It was often difficult for the patients to focus on their rehabilitation because of high levels of anxiety and a preoccupation with financial insecurity and social problems, for example, an insecure housing situation. Thus, it was important to talk to the patients about their anxiety but the issue was often complex; the patients did not understand that they suffered from anxiety and were sometimes not able to describe it in their own language, or they felt ashamed:

There are a lot of taboos and a lack of knowledge about what sort of people go to see a psychologist, why people see a psychologist and what a psychologist does. Also about the consequences of seeing a psychologist. (Psychologist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants described how fear of pain during movement often prevented an increase in activity. The patients perceived their pain as a sign that something was wrong or even broken in their body and some were afraid of needing a wheelchair. If their pain increased during movement, they could perceive moving as being dangerous and when their heart started pounding during movement, it reminded them of the sensations they had when they experienced anxiety. When working on setting individual goals for rehabilitation, the patients and informants had different starting points. If the goals were unrealistic, the rehabilitation process was hampered:

They expect us to take away the pain, but because we can’t take it away, it’s as if there’s been a mismatch somewhere. They have an expectation that we can’t meet, and we can work with something else which doesn’t really exist. (Occupational therapist) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

When the patients had goals associated with housework, the informants stated that they initially thought that those goals were too low, with reference to the ordinary programme. However, these areas were of great importance to the patients and the informants eventually understood that this was an important starting point if they were to understand each other.

Interpreted mediated communication and interpreters caused difficulties in different ways. The informants described how they were often uncertain about whether the patient had understood what the informant had said and whether the reply given by the patient had been correctly translated. Sometimes there was no dialogue, just short answers; sometimes they received obvious mistranslations or just a summary of the patients’ words instead of interpreting word by word.

Creating an alliance with the patient in the presence of an interpreter was a challenge. There were subtle problems such as difficulty making eye contact with the patient when the eye contact between the patient and interpreter became intense. The interpreters sometimes tried to take on the role of the expert, tried to make decisions about the examination and give their own advice. They intended to help but instead they interfered with the informants’ work:

Starts explaining what I meant (yes, exactly, exactly, and they get it wrong). They get it wrong and then you have to explain to the interpreter that (it’s you who?) It’s us who have to sort it out. And I want to know what the patient said because I want to know (yes, exactly). (Social worker) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The interpreters sometimes disrupted the treatment situation, for example, by arriving late at the meeting, by reacting to or acting on the patients’ traumatic stories and anxiety, for example, laughing due to their nervousness or patting the patient. Sometimes the interpreters reacted very strongly and the informants thought about how the interpreters themselves might have a traumatic background. The interpreters could also be a hindrance for the patients to express themselves; they might be afraid of describing sensitive events from the past in front of a fellow countryman. Sometimes when using a remote interpreter, it was obvious that the interpreter was not alone. There were even situations where informants afterwards had learned that the interpreter had made unpleasant remarks to the patient in their common language.

“Solutions”

This category explains how the informants worked with adaptations and strategies for improving their clinical work and their own approach. This included strategies for handling interpreted mediated communication and develop rehabilitation methods to better suit the patients’ needs. Some solutions were already being used and some were under preparation or being considered for further development. The informants’ own approach to themselves and their work developed and became a tool for coping with the remaining difficulties in their clinical work and their frustrations.

Interpreted mediated communication was a necessary tool, and when it worked well, it worked seamlessly.

Then there are some interpreters that you don’t even notice are in the room. Things flow really well, it’s as if they’re just there. It feels like they’re completely neutral and things just flow and then it’s really fantastic. (Social worker) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

When there were problems, the informants described how they learned to handle interpreted mediated communication in different ways. One way was to reduce the time interpreters were involved with each patient. The informants tested the possibilities of conversations without interpreted mediated communication in order to assess the need. Together with the patient, they planned how to gradually decrease the need for interpreted mediated communication. As the patients increased their sense of security at the unit, the Swedish language worked better, and the patients could often manage without interpreted mediated communication during practical interventions. Most of the patients retained interpreted mediated communication during doctor’s visits because they were worried about missing information. Another method was to ensure that the interpreted mediated communication worked as well as possible and when necessary, they did their best to support the interpreters emotionally:

Then the interpreter… I see them reacting. And then they look at me and I look back, and then maybe there’s a little gesture or something, and then they’re reassured, and I know it’s difficult for them. Because it’s difficult watching someone having a full-scale panic attack. For example (yes, exactly) But they’re reassured, they realise they can deal with it, they see it’s okay and they can let it go. That sort of thing. (Psychologist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants strove to use language that was simple, clear and in short sentences. The rules for interpreted mediated communication were read out loud to the interpreters and patients when a new group started and a list with frequently used terms was sent to the interpreter services and the interpreters were trained about how rehabilitation methodology works:

Because we felt that the interpreters saw us as callous and mean for not helping the patients get dressed and undressed when they asked for help. So we had to explain about the process, that we’re actually carrying out an examination. (Physiotherapist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

Before the theoretical sessions with up to four interpreters, the interpreters were specifically instructed, for example, not to handle interpreted mediated questions from other patients until they could use interpreted mediated communication together with the answer from the healthcare professional (informant). When the interpreted mediated communication was unsatisfactory, the informants sometimes attempted to frame the questions differently or stated that they were not satisfied with the interpreted mediated communication, with the risk of being perceived as offensive by the interpreter. If the conversation was still not working satisfactorily, the informants had to end the meeting. In retrospect, the informants described how they regretted that they had not reprimanded the interpreters and ended meetings more often than they had actually done.

It was important to choose the patients who would benefit the most from being included in the IPRI. Some of the most important aspects were whether the patients could speak some Swedish and whether they had been working. This was seen as a major advantage. The informants described how they strove to develop the rehabilitation programme so that it would support the patient in implementing their individual goals as well as gaining knowledge and belonging to a group context. It was important to define and limit the goals and also schedule individual meetings in order to keep close control of the patients’ individual change process:

In a group activity, a lot more goes on than just… well, it’s like… uhm, they can converse to some extent, but there’s also non-verbal communication which may be in a group activity… well, they can have fun together and sometimes they might open up and get to know each other a bit too, and show… (Occupational therapist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants worked with adapting different kinds of material to suit the patients, e.g., information about activities in the programme and learning materials about the body and chronic pain. With time, they improved more and more. They simplified their explanations and the training materials, and they learned how to adapt the learning activities to suit illiterate patients and others, for example, by replacing text with pictures. The training always started on a basic level with knowledge about the body and bodily perceptions:

We start with… I mean, it’s important if you don’t understand about things like pulse and blood pressure, muscles and oxygenation and the link between breathing and pulse, that it’s a good thing if your pulse increases, that pulse rate is linked to anxiety, and sometimes your brain can misinterpret and think it’s caused by anxiety… learning about these sorts of things. (Occupational therapist) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

Teaching patients about pain physiology was a challenge. The informants wanted to use metaphors but found it difficult to know which metaphors they could use in the different languages. There was a constant feeling of a lack of time. Additional time was spent on meetings with the patients and the interpreter, as well as on time learning to work with the interpreter.

But it’s not necessarily only going to take twice as long. Because you might have to find other ways of helping them understand. And I need to understand what the patient says, so often I have to ask the same questions again. And it’s not only about what you say, but… well, it’s everything that goes on in the room, both verbally and non-verbally. (Medical doctor) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

In order to support the patient in a change process, it was important that the patients understood the concept of rehabilitation, were given support to be actively involved and received support throughout the entire process.

So I don’t think you can just dismiss what a person says when they say they want their pain to go away. Because that’s kind of (that’s also) Well, we’re here to approach them and help them understand. (Social worker) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

Preparation before an activity could take place by involving the patient in an exploratory discussion based on their previous experiences, such as details about how they were used to doing housework and what they thought about it. The informants both informed and practically involved the patients with the aim of making them active in their own change process:

…you need to be open to trying new things, to allow… You don’t need to have prior knowledge. But do you want to take part in this? Are you on board? (Psychologist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

It was important to make the patients feel comfortable and safe. This was done by validating the patients, normalising both pain and anxiety, making the patients understand that the informants could deal with their fear, and then doing activities together with the patients.

The informants worked to involve the patients’ relatives to ensure that they understood the aim of the rehabilitation. If they had not, there would be a risk that the relatives would be over-protective and increase the patients’ fear of physical activity, for example, and ultimately, both the patients and the relatives would be afraid:

The most important thing is to explain what pain is. Explain what anxiety is and that it isn’t dangerous. So, for example, if there are children and they see their mum feeling a certain way, that they know it’s not about them. And their mum can still do this and needs to do this, and the child doesn’t need to help her with it. Because children tend to do that. (Psychologist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants described how they took responsibility and struggled with informing other stakeholders about their patients’ needs. To support the patients, they did many things that were not part of their ordinary work: contacted stakeholders, arranged meetings and accompanied patients to meetings at the public employment office. Some situations could be so demanding that the informants expressed that their professional knowledge and working methods were not enough to meet the patients’ different needs.

Which aspects of my psychology training should I use here? What should I do in situations like this? It’s not exactly part of my professional expertise. (Psychologist) (Fewer years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The difficulties were sometimes handled by imagining different ways of working with these patients in a completely different setting out in society. However, the informants also found meaning and started to see important aspects of their work, which made them take an active standpoint about their own motivation for working. They strove to maintain a professional practice standard and treat everyone as an individual and with respect:

Treat them as respectfully as possible, carefully, read through things thoroughly, so they can see from what you’ve written that you’ve listened to them. (Medical doctor) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants developed their own approach. They reflected that they themselves obviously made misinterpretations based on cultural differences. However, fear of cultural missteps must not become an obstacle; they needed to think about being clear and honest in their feedback to the patients about the problem areas, for example, avoidance behaviours, or questioning the patients until they fully understood. It could sometimes be useful to use humour to de-dramatise:

…So here I am seeing a psychologist… do I seem crazy? And in the end they could have a bit of a laugh and joke about it together. (Social worker) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants struggled with finding a balance between engagement and doing their job professionally. It could be emotionally demanding for the informants when they had to reject a patient with significant needs from the rehabilitation programme, although they stated that they could not include a patient simply because they felt sorry for them.

It’s like, either you get lost in structures and planning, or you lose yourself so totally by getting involved that you become drained, and that doesn’t help much either. Instead, you need to try and find a balance between the structure and your involvement so that the two things propel each other forward. (Occupational therapist) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The informants also described the work as being stimulating, for example, when taking part in organised discussions about culture and religion with expert organisations, and also when they were able to work in different group interventions, for example, with creative activities, and when they accompanied the patients to meetings outside the clinic, when they felt that they could play an important role.

It’s fun working with this type of patient group. It’s rewarding when you feel or see or get some sort of feedback that shows a patient has understood or come closer to something they wanted to achieve, it doesn’t matter whether it’s big or small. (Social worker) (More years in the profession than the average for the informant group)

The demanding and meaningful work model

A model was developed to illustrate how the three categories interact and form the core category Demanding and Meaningful Work ().

Figure 1. The Demanding and Meaningful Work model.

Frustration and Challenges are closely related as illustrated through the shared arrow, where the dashed line visualises the continuous and concurrent interaction. Challenges can result in more Frustration and more Frustration can make it more difficult to handle the Challenges. The two categories contribute through reciprocation to the upward growth of the shared arrow.

The opposite-facing arrow represents Solutions. This arrow is narrower, illustrating that only some of the Challenges and Frustration were resolved while the rest remained partly or completely unsolved. Solutions consists of a wide range of solutions, which can mitigate some elements of Frustration and some of the Challenges.

The model can be simplified so the shared arrow (Frustration plus Challenges) represents the demanding work and the opposite-facing arrow (Solutions) represents the meaningful work. However, at a higher level of complexity, the model shows a composite playing field where the informants are located in different parts at the same time and the composite parts together form Demanding and Meaningful Work.

Discussion and conclusions

The main results of this study are the informants’ experiences of Demanding and Meaningful Work in which Frustration about shortcomings in the IPRI, care coordination and difficulties due to cultural dissonance and Challenges in collecting information, cooperating with the patients and managing interpreted mediated communication and interpreters were addressed by developing Solutions for handling interpreted mediated communication, developing rehabilitation methods, supporting patients, and developing their own approach to the work. The results point to challenges for both the authorities and professionals regarding the organisation of healthcare and rehabilitation for this kind of vulnerable patient group, and the need to develop care and rehabilitation according to the patients’ needs. Considering this challenging situation, we also want to highlight the need for support in many areas for healthcare professionals.

The informants often doubted whether the IPRI programme was the right intervention for the patients. Other studies have reported different ways of providing pain rehabilitation for culturally diverse patients [Citation22,Citation28,Citation29]. One qualitative study of a group of Somalian women with chronic pain found IPR to be beneficial, even if an interpreter was used [Citation22]. In contrast to the patients participating in IPRI in this study, the Somalian group all shared a language, and similar background and culture and had the opportunity to share their own experiences within the group which may have contributed to the participants’ positive experiences.

There were also several organisational obstacles, outside the IPRI programme, which hampered the patients. Although the patients had severe needs, they were not prioritised, and the lack of coordinated care was an obstacle. Zander et al. made similar findings in Swedish primary care [Citation21]. The needs of female patients from the Middle East were too complex for healthcare professionals to handle on their own; they entailed a need to develop multi-professional collaboration with other authorities. Coordinated care is supposed to counterbalance fragmentation in healthcare. The development and implementation of coordinated care has been on the agenda in Sweden for many years [Citation30]. However, for patients with chronic pain, so far, few examples have been found where care has been coordinated. A Swedish national report from 2016 [Citation31] concluded that the care for patients with pain has a lack of structure on all levels and that there is no organised collaboration between different levels of care. In the present study, the lack of continued support for patients after the IPRI programme made the informants question the long-term value of the patients’ achievements.

The informants’ experiences of cultural dissonance caused many dilemmas. Differences in how pain was perceived and experienced, and in the individual’s ability to cope with their pain, were important issues. When healthcare professionals and patients have different perspectives, values and beliefs about illness, this can easily cause misunderstandings and difficulties in communication [Citation32]. Zander et al. [Citation21,Citation33] found differences between healthcare professionals and female patients from the Middle East. The female patients identified problems with communication, their background and current life situation, but they also emphasised the importance of finding effective treatment with the help of God [Citation33]. The healthcare professionals did not mention religion or spirituality [Citation21]. Such differences add to the risk of misunderstandings and that healthcare professionals and patients’ crosstalk.

The differences between the patients’ and informants’ living circumstances and views on social obligations and health was another dilemma [Citation18]. When a female patient lives in a paternalistic family and is responsible for taking care of the family and household, a plan for a stepwise restitution of activities, for example, might be unrealistic. It may transpire that she can either do nothing or everything [Citation18]. The importance of educating men about women’s right to autonomy has previously been highlighted by healthcare professionals working with pain rehabilitation for women from the Middle East [Citation21]. The informants in this study described situations in which their patients were unable (due to family demands) or not used to expressing their own wishes and life goals, thereby making the informants lose important tools while working with the patients’ rehabilitation process. This is in line with findings in a review of intercultural communication. Paternotte et al. found in their review that patients with a hierarchical view of the world were not used to reflecting on their own thoughts about illness, which made it difficult for them to answer commonly asked questions [Citation34].

The methods used in IPR [Citation35] require active cooperation between the patient and the care giver. An important part of the work is the definition of each individual’s rehabilitation goal and the drawing up of a plan for how to reach this goal. This work was challenging, as illustrated by Scheermesser et al. [Citation18] who described how patients and healthcare professionals had different views on treatment goals. This contributed to differences in outcome expectations and hampered the rehabilitation process. Similar problems were also described in healthcare settings for other chronic diseases [Citation36]. A review by Holmen et al. reported on difficulties for healthcare professionals in reaching a mutual understanding because patients might trust their cultural traditions more than the healthcare professionals’ explanation [Citation36].

Talking with the patient using an interpreter was another challenge. Previous research has reported language barriers between healthcare professionals and patients, in situations both with and without interpreted mediated communication [Citation18,Citation20,Citation36]. The informants in this study described how the interpreters were of great importance for communication. Meetings were described where there were no problems communicating with the patients, but there were also examples of the opposite.

The informants in this study always used official interpreters, although the skills of the interpreters still varied significantly. The informants learned with time how to work with the interpreters and found solutions to many of the problems, although communication problems remained a major challenge. In a Swiss study, problems with communication were managed by providing similar rehabilitation programmes in two languages: German and Italian [Citation28]. In this way, both patients and professionals could communicate in their own language. However, although the rehabilitation measures were similar, the patients with an Italian immigrant background improved less in their biopsychosocial health and quality of life compared with the German-speaking patients, and at follow-up after 6 and 12 months, there were no improvements among the Italian-speaking patients. The authors conclude that for successful rehabilitation, reducing language barriers is not enough [Citation28].

The informants worked continuously on the development of the programme to make it possible for the patients to understand and take in the content and increase their participation. Adapting information according to the patient’s needs is time-consuming and also a pedagogical challenge [Citation21]. A previous study describes a cultural adaptation of educational material about pain for first-generation immigrant patients from Turkey [Citation37]. After adaptation, different cognitive-behavioural treatments were compared, with and without the cultural adaptation [Citation29]. The results showed a positive effect after both programmes but no lasting effect after 12 months and with no difference between the programmes [Citation29].

The informants in this study stated that the differences in knowledge about and attitudes towards the body, bodily functions and pain were often due to a lack of education and cultural diversity, which is in line with previous research [Citation18,Citation20,Citation21,Citation34]. In order to handle the cultural differences in perception of illness and disease, the informants improved their intercultural communication as described by Paternotte et al. [Citation34]. They developed skills in communication, increased their awareness of cultural differences when assessing the patients’ expectations of IPRI, and also raised their awareness of their own culture [Citation34].

The informants struggled with their own approaches and professional practice standards. Such results have rarely been highlighted before [Citation36]. Instead, the focus has been on the differences in knowledge and attitudes and problems in communication between patients and healthcare professionals [Citation4,Citation18,Citation29,Citation37,Citation38]. Healthcare professionals might be subject to emotional strain when caring for patients with chronic pain, including feeling a sense of failure, guilt and discontent [Citation39]. Other chronic diseases also pose emotional challenges for healthcare professionals, for example, in “maintaining professional sympathy” and in the “burden of responsibility,” described in a qualitative meta-synthesis by Holmen [Citation36] about the experiences of healthcare professionals working with patients with chronic disease. The informants in this study developed their own strategies for developing their professional practice standards and meeting the patients’ significant needs, of which they could only support a few, if any. Their approaches varied. For example, in the assessment they could adhere to the inclusion criteria or they could include nearly all the patients, since all of them needed support. The work to maintain professional practice standards was important, as described in the review by Holmen [Citation36].

In accordance with grounded theory, we did not relate to any specific theory beforehand. However, during the analysis, it became clear that the results could be understood in a wider perspective when relating to the concept of different identities and intersectionality [Citation40]. The fragmentation of healthcare has the most negative impact on individuals with minimal knowledge about the system and society. The patients for whom the informants in this study cared represented multiple identities which added negatively to their status in society: ethnicity, culture, class and minimal knowledge of Swedish. The informants struggled with what for them were different and difficult situations in relation to their own privileged position as Swedish healthcare professionals. It was apparent that their patients were marginalised in both healthcare and society at large. There was no rehabilitation, no adequate care or support [Citation10,Citation11]. Part of the problem was that the patients were female. The informants’ ethical dilemmas increased when paternalistic hierarchies became apparent; they had to be a part of that system and speak up for their patients.

This study can provide an awareness among policy-makers and administrators about vulnerable groups [Citation41], the difficulties these patients face in healthcare and the challenges healthcare professionals face when addressing these groups. Several factors could influence the observed differences in health status, as well as the differences in healthcare access. Our informants encountered challenges with both the social security system and the rehabilitation work being different and more complex than their work with their “usual” patients. Ethical considerations were constantly present. Diana Mulinari [Citation42] discusses the risk in Swedish healthcare of explaining complex processes, in which social, biological and genetic factors interact, using cultural assumptions. She stresses the importance of trying to identify when and why explanations about a patient’s ethnicity are relevant to their health status and when these explanations otherwise increase the boundaries, racism and distance to healthcare.

When establishing healthcare/rehabilitation facilities for patient groups such as those in this study, we want to highlight the importance of providing the necessary resources in terms of time, adequate professional and emotional support for the professionals, and sufficient coordinated care for the patients, in order to meet the standards of equal healthcare. The results also highlight the importance of studying the experiences from the patients’ perspectives [Citation41].

The Demanding and Meaningful Work model, developed through this project, aims to increase awareness among healthcare decision-makers about healthcare professionals’ needs in terms of time, resources and support in their area of expertise when setting up facilities for the rehabilitation of new and vulnerable groups of patients. The model also aims to support healthcare professionals in initiating such work by highlighting areas of potential success, as well as the pitfalls and opportunities for professional development.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Grounded theory generates theories or models located in time, space and context [Citation23,Citation25]. This study was performed at two university clinics in Sweden. These were the first tertiary clinics in Sweden to start pain rehabilitation programmes for non-Swedish-speaking immigrant patients. There is a need for further studies which include the patients’ perspectives before any strong recommendations for clinical practice can be made.

One limitation is the narrow selection of informants. However, there was heterogeneity in age, in professions and in working years in the profession, resulting in a broad range of represented perspectives. Also, two of the researchers had experience from working in such rehabilitation programmes and were collegues or former collegues of the informants. This might be viewed as a limitation as far as the aspect of neutrality is concerned. To increase neutrality, [Citation23] those two researchers did not conduct any interviews at their “home clinic” since they were aware of their preunderstanding and continually discussed the subject with each other and the other participating researchers. On the other hand, their preunderstanding might be viewed as prolonged engagement [Citation23], thereby increasing the credibility of the results.

All in all, the collection of data took more than 2 years. The time span has implications for which rehabilitation programme the informants were describing, since the programme was continuously developed. This might be a limitation but also a strength since the results describe a process where frustrations, challenges and solutions are interacting and the informants reached a high level of intercultural communication in some areas.

Conclusion

The informants’ frustration and challenges when working with a new group of patients, vulnerable and different in their preconceptions, led to new solutions in working methods and approaches. When starting a pain rehabilitation programme for culturally diverse patients, it is important to consider the rehabilitation team’s need for additional time, resources and support.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants for sharing their personal experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- IASP : IASP announces revised definition of pain. 2020. [cited 2020 30 July]. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/NewsDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=10475&navItemNumber=643

- Ekman SL, Emami A. Cultural diversity in health care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007;21(4):417–418.

- Free MM. Cross-cultural conceptions of pain and pain control. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2002;15(2):143–145.

- Sloots M, Dekker JH, Pont M, et al. Reasons of drop-out from rehabilitation in patients of Turkish and Moroccan origin with chronic low back pain in The Netherlands: a qualitative study. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(6):566–573.

- Cote D. Intercultural communication in health care: challenges and solutions in work rehabilitation practices and training: a comprehensive review. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:153–163.

- Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, et al. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302(5):537–549.

- Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in Western countries: a systematic review. Lancet (London, England). 2005;365(9467):1309–1314.

- Buhmann CB. Traumatized refugees: morbidity, treatment and predictors of outcome. Danish Med J. 2014;61:B4871.

- Liedl A, O’Donnell M, Creamer M, et al. Support for the mutual maintenance of pain and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Psychol Med. 2010;40(7):1215–1223.

- Carneiro IG, Rasmussen CD, Jørgensen MB, et al. The association between health and sickness absence among Danish and non-Western immigrant cleaners in Denmark. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86(4):397–405.

- Gilliver SC, Sundquist J, Li X, et al. Recent research on the mental health of immigrants to Sweden: a literature review. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):72–79.

- Allison TR, Symmons DPM, Brammah T, et al. Musculoskeletal pain is more generalised among people from ethnic minorities than among white people in Greater Manchester. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(2):151–156.

- Bosch JA, Cano A. Health psychology special section on disparities in pain. Health Psychol. 2013;32(11):1115–1116.

- Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, et al. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):670–678.

- Fischer MR, Schults ML, Stålnacke BM, et al. Variability in patient characteristics and service provision of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation: a study using the Swedish national quality registry for pain rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52(11):jrm00128.

- Brady B, Veljanova I, Chipchase L. Are multidisciplinary interventions multicultural? A topical review of the pain literature as it relates to culturally diverse patient groups. Pain. 2016;157(2):321–328.

- SBU - The Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment. Rehabilitation in chronic pain - a systematic review. Stockholm: The Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment; 2010.

- Scheermesser M, Bachmann S, Schämann A, et al. A qualitative study on the role of cultural background in patients’ perspectives on rehabilitation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:5.

- Lee TS, Lansbury G, Sullivan G. Health care interpreters: a physiotherapy perspective. Aust J Physiother. 2005;51(3):161–165.

- Dressler D, Pils P. A qualitative study on cross-cultural communication in post-accident in-patient rehabilitation of migrant and ethnic minority patients in Austria. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(14):1181–1190.

- Zander V, Eriksson H, Christensson K, et al. Rehabilitation of women from the Middle East living with chronic pain–perceptions from health care professionals. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(11):1194–1207.

- Semedo B, Stålnacke B-M, Stenberg G. A qualitative study among women immigrants from Somalia – experiences from primary health care multimodal pain rehabilitation in Sweden. Eur J Physiother. 2020;22(4):197–9177.

- Licoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. London: Sage Publications; 1985.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. 2nd ed. London: Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE publications; 1998.

- Ohman A. Qualitative methodology for rehabilitation research. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(5):273–280.

- Vimeo [Internet] Danderyd Hospital. 2016. [cited 2021 May 30]. Available from: https://vimeo.com/159185697.

- Open Code [Internet] Umeå university 2021 [cited 2021 May 30]. Available from: http://www.phmed.umu.se/enheter/epidemiologi/forskning/open-code/.

- Stenberg G, Stålnacke BM, Enthoven P. Implementing multimodal pain rehabilitation in primary care - a health care professional perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(21):2173–2181.

- Orhan C, Van Looveren E, Cagnie B, et al. Are pain beliefs, cognitions, and behaviors influenced by race, ethnicity, and culture in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Pain Phys. 2018;21(6):541–558. Nov

- Ahgren B. Chain of care development in Sweden: results of a national study. Int J Integr Care. 2003;7(3):e01.

- Rivano M, Gordh T, Brodda Jansen G, et al. Nationellt uppdrag: Smärta (in Swedish: National commission: Pain). Stockholm: Swedish Local Authorities and Regions; 2016.

- Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88(2):251–2588.

- Zander V, Müllersdorf M, Christensson K, et al. Struggling for sense of control: everyday life with chronic pain for women of the Iraqi diaspora in Sweden. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41(8):799–807.

- Paternotte E, van Dulme S, van der Leer N, et al. Factors influencing intercultural doctor-patient communication: a realist review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(4):420–445.

- Sharpe L, Jones E, Ashton-James CE, et al. Necessary components of psychological treatment in pain management programs: a Delphi study. Eur J Pain. 2020;24(6):1160–1168.

- Holmen H, Larsen MH, Sallinen MH, et al. Working with patients suffering from chronic diseases can be a balancing act for health care professionals - a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):98.

- Orhan C, Cagnie B, Favoreel A, et al. Development of culturally sensitive Pain Neuroscience Education for first-generation Turkish patients with chronic pain: a modified Delphi study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2019;39:1–9.

- Orhan C, Lenoir D, Favoreel A, et al. Culture-sensitive and standard pain neuroscience education improves pain, disability, and pain cognitions in first-generation Turkish migrants with chronic low back pain: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Phys Theor Pract. 2019;8:1–13.

- Matthias MS, Parpart AL, Nyland KA, et al. The patient-provider relationship in chronic pain care: providers’ perspectives. Pain Med. 2010;11(11):1688–1697.

- Abrams JA, Tabaac A, Jung S, et al. Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Soc Sci Med. 2020;258:113138.

- Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, et al. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113–2121.

- Mulinari D. Medical practices in the post-colonial Sweden - some (feminist) reflections. In: Hovelius B, Johansson EE, editors. Body and gender in medicine (in Swedish: Kropp och genus i medicinen). Lund (Sweden): Studentlitteratur; 2004. p. 459–467.