Abstract

Purpose

This study explored the experiences of patients, caregivers, healthcare providers, and health service leaders of compassion in the care of people hospitalized with COVID-19.

Materials and methods

This study is a secondary analysis of qualitative data deriving from primary research data on recommendations for healthcare organizations providing care to people hospitalized with COVID-19. Participants comprised patients with COVID-19 (n = 10), family caregivers (n = 5) and HCPs in COVID-19 units (n = 12). Primary research data were analyzed deductively under the “lens” of compassion, as defined by Goetz.

Results

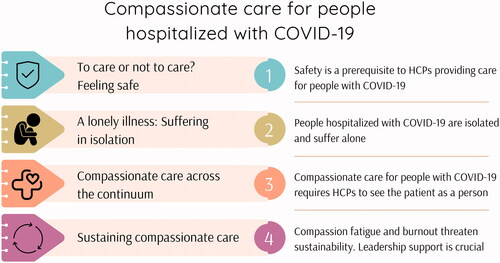

Four interacting themes were found: (1) COVID-19 – to care or not to care? The importance of feeling safe, (2) A lonely illness – suffering in isolation with COVID-19, (3) Compassionate care for people with COVID-19 across the hospital continuum, and (4) Sustaining compassionate care for people hospitalized with COVID-19 – healthcare provider compassion fatigue and burnout.

Conclusions

Compassionate care is not a given for people hospitalized with COVID-19. Healthcare providers must feel safe to provide care before responding compassionately. People hospitalized with COVID-19 experience additional suffering through isolation. Compassionate care for people hospitalized with COVID-19 is more readily identifiable in the rehabilitation setting. However, compassion fatigue and burnout in this context threaten healthcare sustainability.

Healthcare providers need to feel physically and psychologically safe to provide compassionate care for people hospitalized with COVID-19.

People hospitalized with COVID-19 infection experience added suffering through the socially isolating effects of physical distancing.

Compassion and virtuous behaviours displayed by healthcare providers are expected and valued by patients and caregivers, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.

High levels of compassion fatigue and burnout threaten the sustainability of hospital-based care for people with COVID-19.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Background

Compassion is defined as the recognition of suffering in another coupled with a deep desire to alleviate that suffering [Citation1]. Self-compassion follows the same principle, but in relation to sensing and responding to suffering in one’s self through mindfulness, self-kindness, and appreciating the commonality of human suffering [Citation2]. A construct closely linked to compassion is empathy, referring to the sensing the feelings and imagining the perspectives of another [Citation3]. While empathy is often viewed as a necessary but not sufficient component of compassion, it differs from compassion in that it need not be coupled with a desire to alleviate suffering. Evolutionary models suggest compassion is likely innate, having evolved from mammalian caregiving behaviours, through necessity, to protect and nurture vulnerable in-group others [Citation3]. Compassion is also closely linked to virtuous and altruistic behaviours motivated by the benefit of others with no personal gain or even incurring cost [Citation4].

Compassion is widely featured in mission statements among health service professional organizations and regulatory bodies [Citation5]. It is an important component of person-centred care [Citation6] and seen as essential for quality healthcare [Citation7]. Empirically defined, The Healthcare Compassion Model [Citation8], suggests several interacting factors as necessary for compassionate care. These include the virtuous intent and qualities of the healthcare provider (HCP), the patient being seen as a fellow human being, co-development of relational space between patient and HCP, fostering a healing alliance to allow optimal communication, establishment of need(s) and addressing these in a caring, personalized manner [Citation8].

Compassion can be cultivated at a healthcare organization level by creating an environment of physical and psychological safety [Citation9], explicitly valuing equity, diversity, and inclusivity [Citation10], providing training for HCPs in stress management, and dedicating space for reflective practice [Citation11]. Between HCPs and patients, compassion can be facilitated through longer times for consultations and by continuity of care [Citation12]. Leadership behaviours strongly influence the expression of compassion in organizations, “setting the tone” [Citation13], e.g., through altruistic acts by leaders that fuel “moral elevation” experiences in employees [Citation14].

Despite compassion being lauded by healthcare organizations, it is not always evident in practice [Citation15]. Multiple interconnected factors may account for the apparent loss of compassion in healthcare. Personal factors among HCPs, such as developmental history and attachment style [Citation16], perceived social status [Citation17], cognitive load [Citation18], and perceived futility [Citation19] can all act to moderate compassionate behaviour. In HCP education, the “Hidden Curriculum,” i.e., “learning of knowledge, behaviours, and values that [are] different from those being presented in required coursework and related formal teaching activities” can paradoxically facilitate modelling of adverse, sometimes inhumane behaviours [Citation20]. Challenging behaviour (e.g., aggression) by patients, caregivers, or colleagues can act to obstruct HCP compassion [Citation21]. The healthcare environment itself can also inhibit compassion; high volume workload and technology create busy schedules with competing priorities, can limit human contact between HCPs and patients, and has been strongly implicated in HCP burnout and compassion fatigue [Citation22]. Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, compassion fatigue and burnout were known to affect up to 40% and 70%, respectively, of HCPs in the intensive care setting [Citation23]. In rehabilitation settings, compassion fatigue estimates were less described [Citation24], but burnout affected up to 62% [Citation25].

The COVID-19 pandemic has entailed huge challenges, suffering, and excess deaths around the world [Citation26]. A vast number of people have been hospitalized, many critically so [Citation27] and numerous survivors have been left significantly impaired functionally, requiring specialist rehabilitation prior to community re-integration [Citation28]. In Canada, a surge of acute hospital admissions stretched healthcare systems beyond capacity, with limited space, equipment, and staff shortages creating crisis conditions [Citation29,Citation30]. Residents of long-term care (LTC) facilities were disproportionately affected in excess mortality rates, in part due to limited infection control procedure rollout and a shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) for staff, in part relating to for-profit status (for-profit LTC facilities had 25% higher mortality rates compared to municipal facilities, possibly accounted for through having a higher rate of admissions from acute care hospitals) [Citation31]. During this time, HCPs worked under exceptionally difficult circumstances [Citation32], high levels of moral distress [Citation33], compassion fatigue [Citation34], and burnout reported [Citation35], all of which can hinder the provision of compassionate care. Indeed, between spring 2020 and fall 2020, HCPs working in hospital settings in Canada reported an increase in burnout from 30–40% to over 60% [Citation36].

Recent cross-sectional data from >4000 community dwelling adults in 21 countries suggests that there is a key role for compassion in helping people cope during the extraordinary challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation37]. Specifically, greater self-compassion and compassion from others can buffer psychological distress and social fears associated with contracting COVID-19, while greater compassion for others is associated with less depression, also moderating fear of contracting COVID-19. Further, cross-sectional data from multi-disciplinary palliative care HCPs (n = 336) working on the frontline during the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that greater self-compassion correlates with higher resilience, professional-life satisfaction, mental and physical health [Citation38]. Thus, it is important to understand how self-compassion, compassion for and from others are experienced by patients, and exercised by HCPs in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This current study explored how compassion featured in the experiences of health service leaders, HCPs, patients, and family caregivers receiving hospital care following COVID-19 infection, in Toronto, Canada.

Methods

Research design

A qualitative descriptive study utilizing secondary analysis was undertaken [Citation39,Citation40]. Secondary analysis of qualitative data allows researchers to explore participant experiences that are of particular interest in more depth and can help develop new insights. Our primary research study from which data is derived used inductive thematic analysis [Citation41] to develop recommendations for healthcare organizations providing care to people hospitalized with COVID-19. In our primary study, we identified compassion as a potentially relevant theme. Thus, we subsequently analyzed our data deductively under the “lens” of compassion, as defined by Goetz et al. [Citation1]. Using a qualitative descriptive approach allowed us to stay near to participants’ own words and to formulate actionable recommendations to promote change [Citation42,Citation43].

Participants

The sample was recruited from a publicly funded hospital network in Canada, comprised of an acute care hospital and inpatient rehabilitation facility. Patients discharged from the COVID-19 rehabilitation unit (n = 10) and their family caregivers (n = 5) were recruited through the circle of care. Patients in the COVID-19 rehabilitation unit had either been COVID positive prior to admission to the rehabilitation facility or tested positive following admission. HCPs working in COVID-19 units (n = 12) were recruited through email listservs.

Data collection

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board (REB), at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, prior to any recruitment taking place; approval number: 2116. Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. Data were collected through one-on-one semistructured interviews conducted between August 2020 and February 2021 by a researcher trained in qualitative methods (SG). Safety protocols meant all interviews were conducted virtually through Zoom or the telephone. Participants were provided with an interview guide prior to the interview, to allow them to reflect on their experiences. Depending on stakeholder group, interview questions explored experiences with (a) the acute care discharge process, (b) transfer to in-patient rehabilitation, (c) creation of a COVID-19 rehabilitation unit, (d) provision of specific COVID-19 rehabilitation, and (e) community discharge. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, any identifying information removed to protect anonymity. Interviews ranged from 30 to 80 min. Data were collected until saturation was evident [Citation44].

For descriptive purposes, sociodemographic information was collected regarding patient and family caregiver age, sex, birth country, ethnic group, marital status, income, and highest level of education. For HCPs, we collected data on role and professional status within the healthcare institution.

Data analysis

For our primary study, descriptive statistics were used to illustrate sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants. NVivo [Citation45] was used to store and organize qualitative data. Raw data was deconstructed into isolated components, then systematically reconstructed into overarching themes [Citation46]. Two analysts immersed themselves in the data (SG and ZS), reviewing all transcripts, and producing initial codes based on similarity of ideas. These codes formed an initial coding framework that the study team then iteratively refined before systematically applying to all transcripts. The study team practiced reflexivity (i.e., acknowledging own role in the research) by regularly conversing and journaling our experiences, assumptions, and beliefs that may influence analysis. Once our coding framework was finalized, we condensed codes further, based on similarity, meeting again as a study team to develop codes into themes, which were refined through iterative discussion until consensus.

For the secondary analysis, we undertook a “supplementary analysis,” defined by Heaton as “a more in-depth analysis of an emergent issue or aspect of the data, that was not addressed or was only partially addressed in the primary study” [Citation40]. We used the definition of compassion outlined by Goetz et al. [Citation1], i.e., “the feeling that arises in witnessing another's suffering and that motivates a subsequent desire to help,” to guide our deductive thematic analyses. Specifically, we coded data as pertaining to the recognition of suffering, compassionate responding, the context where these experiences/behaviors took place, and what, if any, factors appeared to moderate compassionate responding.

Results

Complete sociodemographic data for participants by group are summarized in . We identified four interacting themes in relation to compassion (see ). These included: (1) COVID-19 – to care or not to care? The importance of feeling safe, (2) A lonely illness – suffering in isolation with COVID-19, (3) Compassionate care for people with COVID-19 across the hospital continuum, and (4) Sustaining compassionate care for people hospitalized with COVID-19 – healthcare provider compassion fatigue and burnout. Each of these themes are described in more detail below with select illustrative quotes in the text and all quotes available in .

Figure 1. Compassionate care themes for people hospitalized with COVID-19.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Table 2. Participant quotes.

Theme 1 – COVID-19 – to care or not to care? The importance of feeling safe

Feeling safe appeared to be prerequisite for HCPs in providing compassionate care to people hospitalized with COVID-19. HCP participants relayed how they were asked initially to provide care to patients with COVID-19 as HCP leaders prepared for the anticipated surge of patients requiring acute care hospitalization and subsequent inpatient rehabilitation. HCPs were presented with a choice by HCP leaders, in that HCPs could chose to volunteer to work on a COVID-19 unit, or not (, Quote 1). Accounts suggested this request precipitated much worry and fear among HCPs, and willingness to work on the COVID unit was described as “a spectrum, where there were people who really wanted to do this…. And people who adamantly did not want to do this” (HCP07, Occupational Therapist, rehab hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quote 2). Altruistic motivations moved some HCPs chose to volunteer (, Quote 3); however, for others, there was a sense that volunteering was expected of them. Fear of contracting COVID-19 was a consistent worry for HCPs deliberating over the request, “Your first thoughts are: how am I going to survive. Nobody wants to catch it, no one wants to help. No one knows the patient suddenly” (HCP07, Occupational Therapist, rehab hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quote 4).

Initial limited access to personal protective equipment PPE was a source of moral distress for HCPs; they worried both for themselves and others, and they experienced “a lot of anxiety […] about whether or not they were being exposed to COVID and that they could get it and bring it home” (HCP01, Professional Practice Leader, rehab hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quote 5). When PPE was made available and the protection it afforded became apparent, HCP fears lessened (, Quote 6). Indeed, HCP personal safety appeared to be a defining prerequisite to providing compassionate care in this context. With PPE in place, HCPs were now able to see the individual beyond the illness and respond compassionately, even under dramatic circumstances. For instance, one health care provider described:

When I sit back and reflect on the person coming on the stretcher, people are transferring in hazmat suits, and so we are all covered from head to toe, but it’s only when you go and say, hello, Mr. So and So, and you’re, like, hey, this is a person, we must help him (HCP06, Patient Care Manager, rehab hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quote 7).

Patients and caregivers were aware that HCPs were working under extraordinary pressures, acknowledging the professionalism and virtues on display (, Quotes 8, 9). However, patients and caregivers also reported a perception that care differed depending on COVID-19 status; when the patient was still deemed as contagious, HCPs were seen as less willing to provide care, and patients felt that the care which was provided lacked compassion (, Quote 10):

They don’t care about the patient. They don’t even sympathize with you. You know, I can, how this transfers, the disease, but it’s not good that you feel that way, and still, you feel like nobody cares (Patient 11, below mean age, COVID -ve on admission to rehab,, Quote 11).

Theme 2 – a lonely illness – suffering in isolation with COVID-19

People hospitalized with COVID-19 were clearly suffering, in large part through isolation. Although patients appeared to understand the need for physical distancing, it was clear this was not an easy experience for them. Boredom, sadness, and a sense of being shunned were reported; in one case, the patient likened the experience to incarceration: “And the biggest thing is that I had to have the door to my room closed all the time, and I hated it, and it was just I didn’t know, I felt like I was in jail” (Patient 05, below mean age, COVID-ve on admission to rehab,, Quote 12).

Visitation restrictions meant that caregivers were not allowed to see their loved ones in person. One caregiver, also an HCP, relayed how her mindset shifted when caring for patients with COVID-19 after seeing her own loved one suffer in isolation:

I went back to my work with more compassion for the patients because now I know how they feel. So, it's a learning for me that I have taken that even when I was giving to my patients, at the time before this happened, it improved me more as a care provider to be really more empathizing and sympathizing with the patients and the families as well (Caregiver 10,, Quote 13).

However, it was not just visitation restrictions that rendered patients isolated and lonely; HCPs also felt caregivers withdraw from contact with patients for fear of contracting COVID-19 (, Quote 14). HCPs too were troubled by how isolation was affecting their patients (, Quote 15) and responded compassionately by facilitating telephone or Zoom calls between patients and caregivers to address patient loneliness (, Quote 16), and in some cases went to considerable lengths personally, to provide comfort and care.

I found that a lot of patients that we were dealing with were very lonely and very needy of attention. I don’t really want to spend any extra time in there than I had to, but a lot of the time you just did that because that’s what these patients needed. They needed somebody to just sit with them. Sometimes they needed somebody to hold their hand (HCP10, Occupational Therapist, rehab hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quote 17).

Theme 3 – compassionate care for patients with COVID-19 across the hospital continuum

Compassionate care was perceived to differ depending on setting. Most patients expressed relief on being transferred to rehabilitation. This relief did not seem due simply to physical recovery from COVID-19, but instead related to perceptions of more compassionate care. Patients cited perceived virtues in their HCPs as highly valued and more tangible in the rehabilitation hospital. For instance, one patient described that “The people that were [at rehab], they were wonderfully kind, helpful, and loving to me… so your heart feels well” (Patient 17,, Quote 18). Indeed, the rehabilitation environment was considered “like a big family” (Patient 06, above mean age, COVID-ve on admission to rehab,, Quote 19), even in the absence of visitation.

Perceptions of compassionate care being deficit in the acute hospital were upsetting to patients (, Quote 20) and considered undignified and inhumane by caregivers.

If they came near her [patient], she was treated like you treat dirt. Something that is dirty, and you don’t want to get contaminated. She said she was treated like a person at the rehab. She felt warm at the rehab. She got attention at the rehab. Now she wasn’t COVID positive anymore, so people won’t be afraid to touch her, and to come into close communication with her, and those kinds of things (Caregiver 07,, Quote 21).

Indeed, caregivers spoke about how the apparent lack of care contravened assumed standards of care (, Quote 22). However, these criticisms were in contra-distinction to some HCP descriptions of how compassionate care was delivered in the acute hospital setting. A vivid example clearly illustrated attunement to patient suffering and explicit steps taken to preserve patient dignity despite the ravages of COVID-19:

Because she felt like she wasn’t presentable enough, so I used…She had some lipstick in her purse. So, we put on her lipstick. We washed her hair. She looked good. And that way, she will be able to face her family. Otherwise, she was at risk of isolation, too. So, just taking that extra minute to do those little things, I want to say that was so important because that helped with the psychosocial component with our patients as well (HCP 11, Registered Nurse, acute hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quote 23).

Theme 4 – sustaining compassionate care for people hospitalized with COVID-19 – healthcare provider compassion fatigue and burnout

Several HCP accounts attested to harsh working conditions in the COVID-19 units and how this undermined their ability to care compassionately. However, this was not a uniform finding, for example, having a smaller caseload led to one nurse being able to spend more time with patients, which constituted “some of the most healthy nursing I’ve done in years” (HCP08, Registered Nurse, rehab hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quote 24).

Nevertheless, the uniquely challenging context that staff faced appears to have contributed to an elevated emotional burden for HCPs. They reported high levels of burnout in both the acute care hospital and rehabilitation COVID-19 units, “I heard many, many stories of people who felt completely burnt out and didn’t feel that they were able to provide the care that they wanted to” (HCP03, Patient Care Manager, rehab hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quotes 25–27). HCP leaders were viewed by frontline HCPs as having an important role in ensuring staff wellbeing and safety, both in practical and humanistic terms (, Quote 28). Where HCP leaders were perceived as unsympathetic to frontline HCP concerns, this undermined staff wellbeing (, Quote 29). However, senior HCP leaders’ accounts suggest a clear awareness and concern that staff were working under severe pressure. Indeed, they took action to demonstrate that they cared, “Listen empathically is probably the thing that I most needed to do” (HCP04, Senior Leader, rehab hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quote 30), and to ensure staff were safe physically, “I think the safety officer program was successful. I think it helps keep the staff, make the staff feel safe, that we were caring for them as well as for the patient. I think that was very important” (HCP12, Senior Leader, acute hospital COVID-19 unit,, Quote 31).

Discussion

The scale and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic has presented unique challenges to global healthcare systems. The surge of acutely, often critically unwell patients subsequently requiring specialist rehabilitation has stressed the continuum of hospital care. In this secondary analysis of qualitative data, we identified four interacting themes pertaining to how compassion featured in the care of people hospitalized with COVID-19. In providing compassionate care for people with COVID-19, personal safety is a prerequisite for HCPs. When HCP and family caregiver contact is constrained, people with COVID-19 frequently suffer in isolation. How people with COVID-19 are cared for across the acute-rehabilitation hospital continuum can differ, which may reflect respective pressures and predominant cultures in these settings. Sustaining compassionate care for people hospitalized with COVID-19 is challenged by an elevated risk of HCP compassion fatigue and burnout.

In this current study, HCPs relayed the difficult decisions they faced when weighing up the potential costs of providing care to people with COVID-19. In keeping with Maslow’s theory of human motivation [Citation47], feeling safe was prerequisite and having access to appropriate PPE facilitated caring and compassionate responses. At a time of crisis, HCPs were moved to help those in need. Prosocial and altruistic motivations feature strongly among reported reasons for becoming an HCP [Citation48]. However, feeling compassion and responding with compassionate action is not a given. Psychological theory suggests that a “Rubicon,” or watershed moment is approached when deciding whether to act or not. The Rubicon for HCPs caring for people with COVID-19 includes weighing perceived threat to self against perceived patient need. Broadly in keeping with Maslow’s theory, self-preservation for HCPs appears paramount [Citation49], but the gravity of the dilemma faced by HCPs cannot be understated [Citation50], as it speaks to core ethical principles, moral obligations, and social pressures in healthcare provision, i.e., to make “the care of the patient the primary concern” [Citation51].

Patients, caregivers, and HCPs in this study all described how COVID-19 status and perceived infectivity influenced the provision of compassionate care, both in the acute hospital and in rehabilitation settings. Physical distancing led to considerable patient suffering through inadvertent social isolation. A pressing concern during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation52], social isolation confers an elevated risk for multiple adverse physical, cognitive, emotional, and social outcomes, including greater mortality [Citation53]. Effective interventions in the community setting include mindfulness, robotic pets, friendship lessons, and use of social facilitation software [Citation54]. The effects of social isolation in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 may be more severe in comparison to those in the community [Citation55] and robust evidence for effective interventions is lacking. In this current study, HCP driven interventions included spending more time with patients, responding personally, seeking to preserve patient dignity, and enabling virtual contact with family.

In this study, patients and caregivers spoke about perceived differences in care between the acute and rehabilitation COVID-19 units, with compassionate care being more often noted in the latter. Potential reasons accounting for perceived differences in care across settings may include elevated risk of delirium in acute settings [Citation56], the prevalent culture of patient and family centered goal setting in rehabilitation [Citation57], coupled with more time with patients and greater continuity of care [Citation58,Citation59]. However, variation in occupational stress(ors) across settings may also contribute, as stress attenuates empathic awareness and compassionate responding [Citation60]. HCPs in acute care routinely work in high pressure, stressful environments [Citation61]. Occupational stress in rehabilitation settings is, by comparison, much less studied [Citation62]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, HCP occupational stressors have been accentuated generally [Citation63], and for reasons similar to those identified in this current study, i.e., HCP personal and family issues, loss of autonomy, staff shortages, and increased workload [Citation34,Citation64].

Multiple HCPs in the current study reported compassion fatigue and burnout. Worse, several patients and family caregivers perceived instances of inhumane care. This fits with recent survey data pointing to higher levels of compassion fatigue and burnout among HCPs working in COVID-19 units [Citation35]. A recent meta-ethnography suggests compassion fatigue and burnout among those caring for people with COVID-19 relate mainly to fear, heavy workload, physical and emotional exhaustion [Citation34]. One of the core facets of burnout is “depersonalization,” or objectification of patients [Citation65]. It is not clear whether the perceived failings in compassionate care, i.e., depersonalization, reported in this current study were due to objectification; there were certainly no direct reports of HCPs actually using words like “dirty” or “animal” when communicating with patients or caregivers, and misperception of HCP intentions and non-verbal behaviors by patients and caregivers is possible. Another plausible explanation, though, is perceived futility on the part of HCPs, in the face of an overwhelming volume of suffering, leading to “compassion collapse” [Citation19].

Implications for future research

We used a very broad, albeit empirical, definition of compassion to guide our analysis. A future study might use a more specific theoretical model, for example, the recently developed Healthcare Compassion Model [Citation8], which, although developed in a palliative care setting, has the potential to be adapted to the context of studying care for people hospitalized with COVID-19.

Implications for policy and practice

Collectively, our findings emphasize that compassionate care cannot be taken for granted in those hospitalized for COVID-19 infection. HCPs face difficult personal and professional dilemmas when caring for people with a highly communicable, lethal disease. Bolstering HCP physical safety through providing appropriate PPE reduces moral distress and seems prerequisite to facilitating caring and compassionate behaviors. Seeking to facilitate the development of self-compassion in HCPs caring for people hospitalized with COVID-19 may be justified [Citation66], given described correlations with higher resilience, professional-life satisfaction, mental and physical health [Citation38]. One possible strategy is through the Mindful-Self-Compassion program [Citation67]. Patients treated for COVID-19 and their caregivers value compassionate care from HCPs regardless of hospital setting. However, healthcare organizations and HCP leaders need to remain alert to the risks of HCP compassion fatigue and burnout in this context and should take proactive steps to pre-empt such issues by using humane and evidence-based strategies, where possible, which may include training in self-compassion for leaders [Citation66]. Investing in the healthcare workforce in this way feeds sustainability, a crucial concern in this ongoing global pandemic [Citation68].

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that we used a well described qualitative analytic method, coding reflexively, refining themes by group discussion and consensus, with themes remaining close to participant accounts. Secondary analysis of qualitative research data has been criticized by some [Citation69], concerns relating to ensuring ethical standards in research are maintained, besides potential issues with removing data from the ecological context in which it was originally collected and analyzed. When taking steps to counter such concerns, we were guided by the recommendations of Ruggiano and Perry [Citation39]. For example, our REB approvals and informed consent procedures ensured participants were made aware that we might perform additional analyses, and we applied the theoretical lens of our supplementary analysis to our own data, in which we were already deeply immersed having recently completed our primary analyses. A limitation with our supplementary analysis is that the original study was not designed to explore compassionate care for people with COVID-19. Thus, the relevance and depth of the data is likely less than it would be had we sought specifically to explore concepts relating to compassionate care within interviews. Additional limitations include a low number of family caregivers, and a sample comprised of mostly Caucasian and well-educated patients, not representative of people hospitalized with COVID-19 who frequently come from other ethnicities and socioeconomic statuses [Citation70].

Conclusion

Caring for people hospitalized with COVID-19 brings unique challenges for healthcare organizations, HCP leaders, HCPs, patients, and caregivers. HCPs need to feel physically and psychologically safe to provide compassionate care in this context and look to HCP leaders to provide this platform. Physical distancing requirements, plus visitation restrictions for caregivers, means that patients hospitalized with COVID-19 are socially isolated, which can be distressing. Hospital setting may influence the demonstration of compassionate care, which may be less apparent in acute care. HCP compassion fatigue and burnout threaten the sustainability of hospital-based care for people with COVID-19.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E. Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(3):351–374.

- Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2(3):223–250.

- De Waal FB, Preston SD. Mammalian empathy: behavioural manifestations and neural basis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(8):498–509.

- Gilbert P. Explorations into the nature and function of compassion. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;28:108–114.

- Canada RCoPaSo. CanMEDS Role: professional. 2021 [cited 2021 Dec 28]. Available from: https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/canmeds/framework/canmeds-role-professional-eaccessed

- Sharp S, McAllister M, Broadbent M. The vital blend of clinical competence and compassion: how patients experience person-centred care. Contemp Nurse. 2016;52(2–3):300–312.

- Mercer SW, Reynolds WJ. Empathy and quality of care. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(Suppl):S9–S12.

- Sinclair S, Hack TF, Raffin-Bouchal S, et al. What are healthcare providers’ understandings and experiences of compassion? The healthcare compassion model: a grounded theory study of healthcare providers in Canada. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e019701.

- Simpson A, Farr‐Wharton B, Reddy P. Correlating workplace compassion, psychological safety and bullying in the healthcare context. Acad Manag Proc. 2019;2019:16632.

- Bilias‐Lolis E, Gelber NW, Rispoli KM, et al. On promoting understanding and equity through compassionate educational practice: toward a new inclusion. Psychol Schs. 2017;54(10):1229–1237.

- Cocker F, Joss N. Compassion fatigue among healthcare, emergency and community service workers: a systematic review. IJERPH. 2016;13(6):618.

- Howick J, Steinkopf L, Ulyte A, et al. How empathic is your healthcare practitioner? A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient surveys. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):136.

- de Zulueta P. How do we sustain compassionate healthcare? Compassionate leadership in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Integr Care. 2021;8:100071.

- Saturn SR. Two factors that fuel compassion: the oxytocin system and the social experience of moral elevation. In: The Oxford handbook of compassion science, Oxford Academic; 2017. p. 121–132.

- Newdick C, Danbury C. Culture, compassion and clinical neglect: probity in the NHS after mid staffordshire. J Med Ethics. 2015;41(12):956–962.

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Adult attachment and compassion: normative and individual difference components. In: The Oxford handbook of compassion science, Oxford Academic; 2017. p. 79–90.

- Piff PK, Moskowitz JP. The class–compassion gap: how socioeconomic factors influence. In: The Oxford handbook of compassion science, Oxford Academic; 2017. p. 317–330.

- Meiring L, Subramoney S, Thomas KG, et al. Empathy and helping: effects of racial group membership and cognitive load. S Afr J Psychol. 2014;44(4):426–438.

- Cameron CD. Compassion collapse: why we are numb to numbers? In: The Oxford handbook of compassion science, Oxford Academic; Vol. 261(271); 2017.

- Hafferty FW, O’Donnell JF. The hidden curriculum in health professional education. Hanover (NH): Dartmouth College Press; 2015.

- Christiansen A, O'Brien MR, Kirton JA, et al. Delivering compassionate care: the enablers and barriers. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(16):833–837.

- Wiljer D, Strudwick G, Crawford A. Caring in a digital age: exploring the interface of humans and machines in the provision of compassionate healthcare. McGill-Queens University Press; 2020. https://www.mqup.ca/without-compassion--there-is-no-healthcare-products-9780228003779.php

- Van Mol MM, Kompanje EJ, Benoit DD, et al. The prevalence of compassion fatigue and burnout among healthcare professionals in intensive care units: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136955.

- McGrath K, Matthews LR, Heard R. Predictors of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in health care workers providing health and rehabilitation services in rural and remote locations: a scoping review. Aust J Rural Health. 2022;30(2):264–280.

- Bateman EA, Viana R. Burnout among specialists and trainees in physical medicine and rehabilitation: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(11):869–874.

- Simonsen L, Viboud C. Mortality: a comprehensive look at the COVID-19 pandemic death toll. Elife. 2021;10:e71974.

- Ginestra JC, Mitchell OJ, Anesi GL, et al. COVID-19 critical illness: a data-driven review. Annu Rev Med. 2022;73(1):95–111.

- Wasilewski MB, Cimino SR, Kokorelias KM, et al. Providing rehabilitation to patients recovering from COVID‐19: a scoping review. PM&R. Wiley Online Library: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pmrj.12669

- Detsky AS, Bogoch II. COVID-19 in Canada: experience and response to waves 2 and 3. JAMA. 2021;326(12):1145–1146.

- Detsky AS, Bogoch II. COVID-19 in Canada: experience and response. JAMA. 2020;324(8):743–744.

- Akhtar-Danesh N, Baumann A, Crea-Arsenio M, et al. COVID-19 excess mortality among long-term care residents in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262807.

- Sriharan A, Ratnapalan S, Tricco AC, et al. Women in healthcare experiencing occupational stress and burnout during COVID-19: a rapid review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4):e048861.

- Smallwood N, Pascoe A, Karimi L, et al. Moral distress and perceived community views are associated with mental health symptoms in frontline health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. IJERPH. 2021;18(16):8723.

- Agyei FB, Bayuo J, Baffour PK, et al. Surviving to thriving”: a meta-ethnography of the experiences of healthcare staff caring for persons with COVID-19. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07112-w

- Ruiz‐Fernández MD, Ramos‐Pichardo JD, Ibáñez‐Masero O, et al. Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID‐19 health crisis in Spain. J Creat Behav. 2020;29(21–22):4321–4330.

- Maunder R, Heeney N, Strudwick G, et al. Burnout in hospital-based healthcare workers during COVID-19. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. 2021;2(46):1–24.

- Matos M, McEwan K, Kanovský M, et al. Compassion protects mental health and social safeness during the COVID-19 pandemic across 21 countries. Mindfulness. 2022;13(4):863–880.

- Garcia ACM, Ferreira ACG, Silva LSR, et al. Mindful self-care, self-compassion, and resilience among palliative care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;64(1):49–57.

- Ruggiano N, Perry TE. Conducting secondary analysis of qualitative data: should we, can we, and how? Qual Soc Work. 2019;18(1):81–97.

- Heaton J. Secondary analysis of qualitative data: an overview. Historical Soc Res. 2008;33(3):33–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/23293691.2022.2090304

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340.

- Sandelowski M. What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84.

- Thorogood N, Green J. Qualitative methods for health research. London (UK): SAGE Publications Ltd; 2009.

- Richards L. Using NVivo in qualitative research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1999.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev. 1943;50(4):370–396.

- Wouters A, Bakker AH, van Wijk IJ, et al. A qualitative analysis of statements on motivation of applicants for medical school. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):200–211.

- Poulin MJ. To help or not to help: goal commitment and the goodness of compassion. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017.

- Menon V, Padhy SK. Ethical dilemmas faced by health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic: issues, implications and suggestions. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102116.

- Jaques HG. Publishes new version of good medical practice. British Medical Journal: https://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.f2003; 2013.

- Pietromonaco PR, Overall NC. Implications of social isolation, separation, and loss during the COVID-19 pandemic for couples' relationships. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;43:189–194.

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237.

- Williams CY, Townson AT, Kapur M, et al. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness during COVID-19 physical distancing measures: a rapid systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0247139.

- Walecka I, Ciechanowicz P, Dopytalska K, et al. Psychological consequences of hospital isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic-research on the sample of polish firefighting academy students. Curr Psychol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01982-3

- Boehm LM, Jones AC, Selim AA, et al. Delirium-related distress in the ICU: a qualitative Meta-synthesis of patient and family perspectives and experiences. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;122:104030.

- Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. London, England: SAGE Publications Sage UK; 2009.

- Medina-Mirapeix F, Oliveira-Sousa SL, Escolar-Reina P, et al. Continuity of care in hospital rehabilitation services: a qualitative insight from inpatients’ experience. Braz J Phys Ther. 2017;21(2):85–91.

- Hirschman KB, Shaid E, McCauley K, et al. Continuity of care: the transitional care model. Online J Issues Nurs. 2015;20(3):1.

- Stevens L, Gauthier-Braham M, Bush B. The brain that longs to care for itself: the current neuroscience of self-compassion. The neuroscience of empathy, compassion, and self-compassion. Elsevier; 2018. p. 91–120.

- Upton KV. An investigation into compassion fatigue and self-compassion in acute medical care hospital nurses: a mixed methods study. J Compassionate Health Care. 2018;5(1):1–27.

- Allday RA, Newell JM, Sukovskyy Y. Burnout, compassion fatigue and professional resilience in caregivers of children with disabilities in Ukraine. Eur J Soc Work. 2020;23(1):4–17.

- Hochwarter W, Jordan S, Kiewitz C, et al. Losing compassion for patients? The implications of COVID-19 on compassion fatigue and event-related post-traumatic stress disorder in nurses. JMP. 2022;37(3):206–223.

- Cubitt LJ, Im YR, Scott CJ, et al. Beyond PPE: a mixed qualitative–quantitative study capturing the wider issues affecting doctors’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e050223.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–529.

- Lefebvre J-I, Montani F, Courcy F. Self-compassion and resilience at work: a practice-oriented review. Adv Dev Hum Resour. 2020;22(4):437–452.

- Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self‐compassion program. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(1):28–44.

- Rathnayake D, Clarke M, Jayasinghe VI. Health system performance and health system preparedness for the post-pandemic impact of COVID-19: a review. Int J Healthcare Manage. 2021;14(1):250–254.

- Walters P. Qualitative archiving: engaging with epistemological misgivings. Aust J Soc Issues. 2009;44(3):309–320.

- Wingert A, Pillay J, Gates M, et al. Risk factors for severity of COVID-19: a rapid review to inform vaccine prioritisation in Canada. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e044684.