Abstract

Purpose

It is well documented parents of children who have a disability are at an increased risk of poor mental health and wellbeing. A capacity building program designed to build key worker self-efficacy to support the mental health of parents accessing early childhood intervention services (ECIS) for their child was trialled.

Materials and Methods

A stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial design was utilised to deliver and evaluate a 12-month intervention program, comprising tailored professional development, resource development and sustainability measures. The repeated measurements on individuals in six clusters over three follow-up periods were analysed using linear mixed models. Comparison of the control and new program statistical means (adjusted for period effects) were assessed with an F test.

Results

Key workers reported increased confidence to talk to parents about their own wellbeing (d = 0.51, F(1, 51.8) = 4.28, p = 0.044) and knowledge of parental mental wellbeing improved (p = 0.006). A reduction in staff sick leave partially offset the cost of the intervention.

Conclusions

A multi-pronged intervention targeted at key workers was found to be an effective way to ensure parental wellbeing is supported at an ECIS in Australia.

Trial Registration

ACTRN12617001530314

There are implications for the development of children whose parents are experiencing high stress and poor mental health, whereby parents of children with disability or developmental delays are at increased risk.

Findings from this study support the recommendation that a key worker is provided to holistically support families who access Early Childhood Intervention Services to aid in reducing poor parental wellbeing and child outcomes.

Improved confidence to support and initiate conversations regarding parental wellbeing by key workers, in combination with support from management and the organisation to undertake this as part of their role, is a positive finding from this intervention study.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Background

It is well documented that parents of children who have a disability are at an increased risk of experiencing issues with their mental health and wellbeing [Citation1–6]. In an Australian study, mothers of children with a disability reported one to two standard deviations below other Australians in five out of eight Short Form (SF-36) Health Survey domains, a well-known measure to assess health status, as well as scoring lower on the overall mental health component score [Citation5,Citation7]. Factors contributing to impaired mental health included a higher intensity of caregiver duties, grief associated with the diagnosis of the child’s disability, and difficulties associated with receiving adequate and timely support from health and community services [Citation1,Citation8].

Early childhood intervention services and family centred practice

Early Childhood Intervention Services (ECIS) provide specialised support and services for children with a disability and/or development delay with the aim of increased functional independence and social participation for children and their families. This service, which can include support for families, is provided in many Western countries such as the US, UK, Canada and Australia. In Australia, where this study was conducted, an ECIS provider often offers supports via the key worker model. A key worker has expertise in child development, learning and wellbeing, as well as professional qualifications, in fields such as occupational therapy, physiotherapy, psychology, speech pathology, social work and special and early childhood education [Citation9]. Following best practice, a key worker takes a lead role in ensuring that a transdisciplinary group of professional’s work in collaboration with the family to provide a ‘team around the child’. Family-centred practice is considered a key approach to working with children with a disability or developmental delay because providing professional supports to develop trust with the child’s family and strengthening daily family functioning theoretically provides the best chance for positive developmental outcomes [Citation10,Citation11]. In line with family-centred practice principles, provision of emotional support for parents and carers of a child with a disability should be standard care by key workers, but research has shown this may not be provided or prioritised by all professionals [Citation12,Citation13].

National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS)

Following the findings of a Productivity Commission into the Australian disability sector, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was introduced in 2013 to improve the lives of people with disability and their families. The NDIS aims to provide adequate access to social services support and promote active participation in society [Citation14]. The control of funding and choice of services resides with the person with a disability or their primary carer, rather than disability service providers [Citation15]. Early Childhood Early Intervention (ECEI) services provided by the NDIS are listed under ‘capacity building supports for early childhood’. Each child’s NDIS plan is expected to focus on functional and participation-based goals and be regularly reviewed by the service provider [Citation16]. However, issues have been raised about scheme implementation, including reports that some children and their families are not receiving timely or adequate access to services, and/or access to skilled planners and support coordination to link them into the services they need [Citation17–20]. It is likely that these factors, particularly a delay in access to ECIS, could have detrimental impacts on a child’s future developmental outcomes and family quality of life [Citation21,Citation22]. Many ECIS services are provided by individual therapists, rather than transdisciplinary key worker teams [Citation18,Citation23]. The authors deemed that the shift to a therapy-only service for the child (rather than family-centred practice) risks failing to identify and respond to parental distress. Further to this, low staff self-efficacy and limited training to effectively support parental distress, along with unclear role boundaries exacerbated by the introduction of the NDIS, may reduce timely and effective emotional support for parents accessing ECISs [Citation23].

Development of the intervention

This study was preceded by a qualitative scoping study, conducted prior to the introduction of the NDIS to inform the development of an intervention that aimed to identify what families with children with a disability or developmental delay required from the ECIS to optimize their health and well-being, and how staff could facilitate this [Citation23,Citation24]. Although parents reported they were satisfied with the professional advice and therapeutic support that their child received from their key worker; they reported that they struggled with their own mental wellbeing and felt this did not receive adequate acknowledgment and support. Discussions with key workers found one of their major challenges at work was addressing parental distress, particularly within the boundaries of their role to provide child-related therapy. They expressed a need for increased confidence, knowledge, skill and organisational support to more effectively support parental mental wellbeing during their in-home visits. In line with the literature, these results suggested the need for professional development to increase key workers’ knowledge, skills and confidence to assist with addressing parental distress, and improved organisational structures to enhance staff wellbeing whilst providing help to parents.

Study aims

The aims of this study were to trial a capacity building program to increase staff knowledge and self-efficacy to manage the mental wellbeing of the parents at an ECIS; and to evaluate the feasibility, value for money and sustainability of the intervention program provided within a disability service (see published protocol [Citation25] for detailed description of the study and outcome measures). This paper reports on the trialling and evaluation of the intervention program, titled the ‘Pursuit of Wellbeing’, within an Australian ECIS setting.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval was obtained from The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Number 1648536.1) and Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC Number 2017-262). The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12617001530314) on 3 November 2017.

Study setting

The ‘Pursuit of Wellbeing’ study was co-developed and conducted in partnership with a major Victorian non-government disability service provider in Victoria, Australia and involved all staff based within their ECIS, which provides services to children aged up to six years and their families from six different sites across metropolitan Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Study design

‘Pursuit of wellbeing’ program

A one-day professional development training session for key workers was developed and facilitated by an internal senior manager from the disability service with a clinical psychology background. It included the following educational modules: i) the importance of, and barriers to, supporting parental mental wellbeing; ii) capacity building activities to increase confidence to support parental wellbeing; and iii) a toolkit of psychological resources for key workers to discuss well-being with parents during home visits [Citation25]. The training was also delivered to managers to strengthen their capacity to support their staff to incorporate the new knowledge and skills into their role.

Stepped-wedge trial design

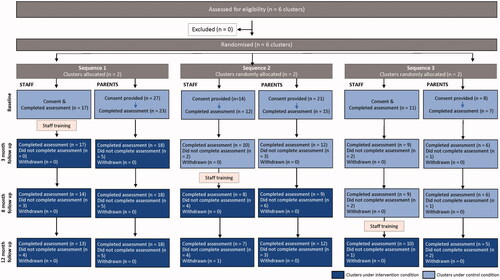

A stepped-wedge design was selected to deliver and evaluate the program. This trial design [Citation26] was appropriate and practical in this setting as staff and parents associated with each hub were sequentially exposed to the intervention over an eight-month period, thus ensuring equitable access. Please see the protocol paper for a complete description of the study design [Citation25]. At three successive time points after a baseline (0 months) assessment, two hubs received the intervention. The first two hubs were not randomised due to organisational readiness to undertake the intervention. The four remaining hubs were then randomised to cross over from the control group to receive the intervention at either the 3 month or 8 month follow up mark. Participation and retention in the study by ECIS staff and parents is depicted in following CONSORT reporting recommendations for stepped-wedge trials [Citation27].

Figure 1. Participant flow diagram using stepped wedge randomised design demonstrating sample sizes and participant dropout for at the four data collection time points (Baseline, 3 month, 8 month and 12 month follow up).

While the sample size (six hubs) was pragmatically determined by the number of hubs in the selected ECIS and the funding period for the roll-out of the intervention, sample size calculations, conducted via simulation, indicated that with six to eight keyworkers repeatedly assessed at each site (i.e., 144 to 192 observations), there was 80% power to detect effect sizes (the difference in the post and pre intervention means divided by the total standard deviation) of between 0.5 and 0.7 for a range of plausible variance components. Cost data is focused on rigor and representativeness, as effect size issues are rarely applicable.

Participant recruitment

Staff recruitment

All key workers and managers at each hub had the opportunity to participate in the intervention as this was delivered to all ECIS staff through the one-day training and provision of resources. Researchers attended staff meetings prior to the intervention to invite staff to participate in the evaluation. To allow key workers to feel comfortable in providing feedback on their current management and any adverse experiences encountered, staff had the option of returning the consent form directly to the researchers so managers of each hub were blinded to which key workers were taking part in the evaluation. Reminder emails were sent to all staff by management to enhance recruitment before the intervention was delivered at each hub.

Parent/carer recruitment

To recruit parents/primary carer, all key workers were requested to pass on the plain language statement and consent form during their regular home visits to families. Recruitment forms were also distributed via each hub’s administrator. Written consent was provided by the parent or carer to the researcher directly or via the key worker to the researcher. Our inclusion criteria was any child/family dyad that was eligible for Early Intervention services. Children from mild to severe ranges of disability were included. Parents who accessed the service opted in to participate in our evaluation.

Data collection

Repeated online assessments were conducted with key workers, managers and parents/carers using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) hosted at The University of Melbourne [Citation28]. Consistent with the stepped wedged design assessments occurred at a total of four time points (baseline, 3 months, 8 months, 12 months) with each survey link distributed via email (see ).

Outcome variables

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was key worker self-efficacy in supporting parental mental wellbeing. This was a newly developed measure by the researchers due to Bandura’s recommendation that self-efficacy measurement be task specific [Citation29], and is available in the study protocol [Citation25]. Item generation for the key worker confidence KWC scale was developed through consensus with an advisory panel representing experts from multiple fields (public health, disability and rehabilitation, mental health, pediatrics, health economics, biostatistics). While this is not a pre-existing validated scale, the items were found to have high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .93). KWC was assessed as the average of ten measures (A-J) collected on a visual analogue scale bounded at 0 and 100. The items were developed to assess perceived confidence of staff in understanding and supporting parental mental well-being; their knowledge about how to communicate with parents about their well-being and how to refer parents for additional help. The first four items (A-D) formed the domain of “understanding”, and the last five items (F-J) formed the domain of “knowing”. The remaining singleton item (E) namely “Talking to parents of children with a disability about their own well-being”, directly related to communication and was considered to be a domain in its own right. For all items, domains and the overall KWC, higher scores reflected a higher level of self-efficacy. Domains as well as individual items were statistically analysed.

Secondary outcomes

The assessment of the secondary outcome data reported in this paper are detailed below, with the scales available in the published study protocol [Citation25]:

Parental mental well-being

Parental mental wellbeing was assessed using the shortened Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale [Citation30], with the seven items (A-G) assessed using a 5-point Likert scale from (‘None of the time’ to ‘All of the time’) averaged and also analysed individually. Higher scores reflect higher levels of mental wellbeing.

Job-related well-being

Job-related mental wellbeing was assessed using nine items from a scale published by Warr [Citation31] with each item being assessed using a 5-point Likert scale (‘Strongly disagree’ - ‘Strongly agree’) with B, D, F, G, H and I reverse-scored. Higher scores reflect a higher level of well-being. The ‘Job Competence Domain’ is the unweighted average of items A-F and the ‘Negative Job Carryover Domain’ is the unweighted average of items G, H and I.

A second scale by Warr with twelve items (A – L) was used to assess job-related affective wellbeing for staff [Citation31–33] using a 6-point Likert scale ’never’ to ‘all’ (‘Never’ – ‘All of the time’). The four “quadrants” are defined as:

HAUA = high-activation unpleasant affect, partly summarised as anxiety (items A, B and C);

HAPA = high-activation pleasant affect, partly summarised as enthusiasm (items J, K and L);

LAUA = low-activation unpleasant affect, partly summarised as depression (items G, H and I);

LAPA = low-activation pleasant affect, partly summarised as comfort (items D, E and F).

Higher scores reflect a higher level of job-related well-being. Affects in the four quadrants tend to be inter-correlated, but can have different causes and consequences [Citation33]. Demands from a job are more strongly negatively related to the Anxiety and Comfort quadrant than to the other quadrants Depression and Enthusiasm [Citation34].

Parental satisfaction with key workers

To assess parental satisfaction with key workers, five items were developed (A-E) with each assessed using a 5-point Likert scale. The items are based on previous assessments used by the partner disability organisation to assess parental satisfaction with the service and parents’ perceived support from key workers [Citation25]. Higher scores reflect a higher level of parental satisfaction.

Staff perceptions of supervisory support

Three out of eight items were used from Eisenberg’s Perceived Supervisor Support scale [Citation35,Citation36], with each assessed using a 7-point Likert scale. Higher scores reflect higher levels of satisfaction with supervisory support. The average of the three items was also calculated and statistically analysed.

Economic credentials

Economic credentials were assessed using cost consequences analysis that combines trial outcomes and an assessment of costs and cost offsets. Key components were program cost, staff absenteeism and health services used by parents at an individual level, assessed using the service provider’s data and self-reported by the parent using the World Health Organisation Health and Performance Questionnaire [Citation37,Citation38]. Previous studies have found that absence from work relates to staff wellbeing [Citation39]. Therefore, we hypothesised that receiving the capacity building program would decrease staff absenteeism. Hours of sick leave was used as a proxy for absenteeism. It was also hypothesised that if parental mental wellbeing was addressed by key workers, they would be less likely to use both health care resources and non-health care services to support their mental wellbeing, such as psychologists or pastoral care.

Statistical methods

The repeated measurements of endpoints were analysed using linear mixed models with random effects for hubs, individuals within hubs and assessments within individuals, and with fixed effects for “time” (0, 3, 8, and, 12 months) and “condition” (pre or post exposure to the new program). Comparisons of the pre and post exposure conditions (i.e., control versus intervention) were conducted on the predicted means, hereafter referred to as “means”, which were constructed from the estimated fixed effects in the mixed model. The F-test was used to compare these means and diagnostic residual plots were examined to check the key assumption (homogeneity of variance of residuals) on which the methodology is based. Checks for autocorrelation in the repeated assessments were conducted and the simple “equicorrelation” model was almost always the best fitting model and, accordingly, it has been used as the basis for all the reported analyses. Means (M) are reported together with their standard errors (SEs), which were constructed from the variance components estimated in the linear mixed models. Effect sizes (d) were calculated as the difference in a pair of predicted means divided by the square root of the sum of the estimated variance components. A 5% significance level (i.e., p < 0.05) was used to highlight differences in means and no adjustment has been made for multiplicity of comparisons. The REML directive in the Genstat statistical package was used for all mixed model analyses [Citation40].

The "classic" pre vs post design in which the "pre" measurement occurs during the control condition and the "post" measurement occurs after the intervention has been implemented, completely confounds the passage of time (and associated external factors) with the intervention. The stepped-wedge design [Citation26] is a non-orthogonal design that, when analysed, uncouples the partially confounded effects of elapsed time and the uni-directional switch from the control condition to the intervention condition. As such, the authors Hussey & Hughes (2007) suggest it is an "innovative choice for a cluster randomised crossover trial" that is particularly suited to the evaluation of the roll-out of community-level or group-level interventions for which a return to the control condition is considered to be "unethical" or not feasible (due to "contamination" or carryover effects).

Economic analysis

Linear mixed models with similar random and fixed effects to the primary outcomes analysis was employed. The best fitting model used to predict means of the economic outcomes was selected based on AIC (Akaike Information Criteria) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criteria). Diagnostic residual plots were examined to check the homogeneity of variance of residuals. The STATA 16 statistical package [Citation41] was used for the economic analysis.

Costs of the capacity building program using Australian 2019 prices were estimated using a top-down costing approach. Staff related time costs for those who attended the training was assumed to be equal to the cost of service outlined in the NDIS 2019 ECIS price guide at $214.41/hour. The opportunity cost to the provider of one hour of sick leave was determined from the difference between the NDIS price for ECIS and NDIS indexed Base Price limit 2019-20 at $52.85 suggested by the NDIS cost model [Citation16].

Results

Sample characteristics

Forty-two staff participated in baseline data collection. Majority of participants were female aged 25–45 years (71.4%). Speech therapy (42.0%) and occupational therapy (28.6%) were the dominant participant disciplinary backgrounds ().

Table 1. Staff characteristics at baseline (n = 42).

Forty-five primary carers participated in baseline data collection, with the majority being mothers (88.9%). Participants most commonly reported that their main duties were paid employment or home duties, highest education level varied from Year 10 completion to postgraduate degree (). The final survey was completed by 76.0% of parents. Recruitment of parents relied on staff at each hub to share information with parents and invite them to participate in the study. There was varied interest and uptake across hubs therefore not all key workers involved in the evaluation had a parent under their care that also participated in the evaluation.

Table 2. Parent characteristics at baseline (n = 45).

Primary outcome – key workers’ self efficacy to support parental mental wellbeing

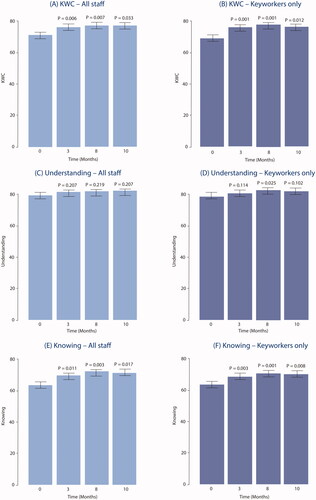

There was a statistically significant improvement (F(3, 95.6) = 3.12, p = 0.029) in self-efficacy for staff over the course of the trial with the means increasing from 70.7 at baseline to 76.9 at the 8-month assessment (). A similar improvement (F(3, 79.7), p = 0.003) was observed when analysis was restricted to key workers (i.e., excluding managers) (). The improvement in self-efficacy of all staff from pre-exposure (73.15 ± 2.03) to post-exposure (76.93 ± 1.94), adjusted for the underlying change over time, was not statistically significant (d = 0.34, F(1, 97.9) = 3.15, p = 0.079) and when restricted to key workers the observed increase from a pre-exposure mean of 72.56 ± 1.91 to a post-exposure mean of 75.63 ± 1.78, was also not statistically significant (d = 0.32, F(1, 82.1) = 1.88, p = 0.174).

Figure 2. Key workers’ self-efficacy in supporting parental mental well-being. Predicted means and their standard errors. P-values refer to comparisons with the baseline (0 months) mean.

The “Understanding” domain (items A-D) showed no statistically significant improvement (p = 0.568) over time in all staff () and also in the analysis restricted to key workers (p = 0.166), however the observed improvement at 8 months () was statistically significant (p = 0.025) and was sustained. Small improvements from pre to post intervention were noted but were not significant in the analyses of all staff (, Pre = 82.1, Post = 83.4, d = 0.17, F(1, 97.3) = 0.87, p = 0.353) or key workers only (, Pre = 82.4, Post = 83.1, d = 0.07, F(1, 81.4) = 0.10, p = 0.753).

Table 3a. Self-Efficacy, pre and post intervention predicted means and their standard errors for all staff.

Table 3b. Key Workers’ Self-Efficacy, pre and post intervention predicted means and their standard errors.

The “Knowing” domain (items F-J) showed statistically significant improvements from baseline in all staff (p = 0.026, ) and in key workers (p = 0.006, ).

Improvements associated with the intervention were not significant at the conventional 0.05 level in the analyses of all staff (, Pre = 65.9, Post = 71.4, d = 0.40, F(1, 94.5) = 3.83, p = 0.053) and key workers only (, Pre = 64.5, Post = 69.6, d = 0.42, F(1, 79.3) = 2.92, p = 0.091). However, two of the five items (G and H. “Knowing how to support parents’ wellbeing”, “Knowing how much time a key worker should spend on supporting parents’ wellbeing”) in the “Knowing” domain showed significant improvements in the analyses of all staff () and in key workers ().

For key workers, the communication item (E. “Talking to parents of children with a disability about their own wellbeing”) showed a statistically significant increase (d = 0.51, F(1, 51.8) = 4.28, p = 0.044) from pre to post intervention ().

To investigate the durability of the effect of the intervention on the primary outcome variable KWC, exploratory analyses were conducted. Declines over time in the post-exposure predicted means were noted but there was no statistically significant overall variation in these means. Supplementary Table S2 can be read in conjunction with .

Secondary Outcome - Parental mental wellbeing

Parental mental wellbeing (PMWB) averaged over the seven items did not vary significantly over time (p = 0.238) and the observed improvement (pre versus post intervention), while not statistically significant (p = 0.095), appeared to be driven by a statistically significant improvement in one of the items (E) “I’ve been thinking clearly” ().

Table 4. Parental mental wellbeing, pre and post intervention means and their standard errors.

Secondary Outcome - Job-Related Well-Being

Job-Related mental Well-Being

For key workers the job competence domain exhibited a statistically significant worsening as did the component item (D. Job quite difficult). The item (F) that referred to “In my job I often have trouble coping” also exhibited a significant worsening from a mean score of 3.89 to 3.40 (p = 0.013) (). When managers were included in the analysis there were no significant changes in the domain scores but one item (D. Job quite difficult) exhibited a statistically significant worsening post intervention (p = 0.013).

Table 5. Job-related well-being, pre and post intervention means and their standard errors for key workers.

Job-Related affective Well-Being

Results for key workers show no statistically significant improvements for job-related affective wellbeing due to the intervention ().

Table 6. Four-quadrant investigation of job-related affects and behaviours in key workers, pre and post intervention means and their standard errors.

Secondary Outcome - Parent satisfaction with key workers

Mean levels of satisfaction were observed to have increased for each item and the overall mean score () but there were no statistically significant increases.

Table 7. Parent satisfaction with key workers (PSWKW), pre and post intervention means and their standard errors.

In a series of unplanned supplementary analyses of the parental outcomes that were measured on 5-point Likert scales, the parental mental wellbeing items (including their average, PMWB) and the parental satisfaction with key workers items (including their average, PSWKW) were dichotomised at > =3 and also at > =4 and analysed using generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs). The rationale for this was that some of the items had high (i.e., > 4) pre and post predicted means and changes in the left-tails of the distributions of the bounded discrete 5-point Likert scales may have been obscured in the linear mixed model analyses. The results of the GLMM analyses are summarised in Table S1. Comparisons of the results with the corresponding PMWB results in and the PSWKW results in Table 7 indicate attenuation in the p-values, most likely associated with the loss of information that accompanies dichotomisation of a measurement scale. However one item (PSWKW, Item c, “KW Listened”) when dichotomised at > =4, had a small reduction in the p-value for the pre versus post comparison possibly due to the pre and post means (4.01 and 4.32 respectively in ) being close to the upper bound of the Likert scale.

Secondary outcome – staff perceptions of supervisory support

Statistically significant increases in the averages and the first two items (a. ‘Goals and values’, and b. ‘Help is available’) were observed for analyses based on all staff () and for analyses restricted to key workers (). Improvements in the rating of the third item, “My supervisor really cares about my wellbeing” were observed but were not significant at the 5% level.

Table 8a. Perceived supervisor support (PSS), pre and post intervention means and their standard errors for all staff.

Table 8b. Perceived supervisor support (PSS), pre and post intervention means (M) and their standard errors for key workers only.

Secondary outcomes – economic evaluation

Staff characteristics e.g., employment status (full time and part time), employment class and position were not statistically significant predictive variables in the regression model used to assess economic outcomes. About 30% of parents did not use health services. General practitioners (GP) accounted for 66% (63 out of the 96 over the entire study period) of all reported health services followed by psychologist services (11%). Other health services (e.g., counsellor, community health services), ranged from 1%-7%. Over 80% of the 45 parents did not use non-health support and respite was only used by 4% of parents. The average hours of sick leave per 3-months among key workers who attended the program decreased, but the change was non-statistically significant. Increases were found in the most used health services (GPs and psychiatrists), similarly not statistically significant ().

Table 9. Pre and post intervention means and their standard errors of economic outcomes.

Six training sessions were delivered to 72 staff in total. The average cost to provide a one-day training by an in-house facilitator was $3,317 per session or $264 per person. demonstrates the breakdown in costs for each training component.

Table 10. Cost of the intervention.

The NDIS billable price for ECIS was $214.41/hour and the NDIS estimated unit cost of ECIS for disability service providers was $52.85 on average. The difference of $161.56 between the billable price and the average unit cost is an ‘opportunity cost’ (i.e., benefit forgone) to the disability service provider, when the worker takes sick leave. Based on this opportunity cost, an average reduction of 1.63 h in sick leave would achieve a break even result with the training cost per head. lists the average sick leave of key workers who attended the training and provided ECIS was slightly reduced by 0.2 h, this is not significant at the normal 5% level.

Discussion

This study evaluated the roll-out of a capacity building intervention program for key workers within an ECIS to improve parent and staff mental wellbeing. Over the period of the roll-out, key worker confidence (KWC) to support parental mental wellbeing significantly improved and was maintained, but after adjustment for this trend, the effect of the intervention program on KWC was not statistically significant. Improvement for all staff was seen in the assessment of ‘knowing’ how to support parental wellbeing which appeared to be influenced by the intervention (p = 0.053), but this was not as evident when the analysis was restricted to key workers (p = 0.091). However, two of the five components of the knowing domain exhibited statistically significant improvements associated with the intervention for all staff, namely “Knowing how to support parents’ well-being” and “Knowing how much time a key worker should spend on supporting parents’ well-being”. We found that uncontrollable and/or unknown factors, linked to the passage of time, were significantly associated with an improvement in knowledge from baseline to 8 months. But despite this, we also found that after adjustment, the controllable intervention had a causal effect on 2 of the 5 components of the knowing domain. The relative importance of the two factors (time and intervention) in any future roll-out of this (or a similar) intervention naturally depends on the presence and extent of the uncontrollable factors at work in the milieu in which the intervention is rolled out, but it would be reasonable to expect the demonstrated intervention effect to be present.

Of particular note is that key workers reported a statistically significant improvement in “Talking to parents of children with a disability about their own well-being” (p = 0.044). This single item in the 10-item KWC is the only one that related directly to communication and this improvement has important implications for service delivery. Qualitative research undertaken by Gilson et al (2018) found health professionals working with mothers of a child with a disability had a good understanding of the mental health difficulties faced by these mothers but lacked confidence to engage in open discussion with them. Another Australian study reported staff working with children had experienced anxiety associated with discussing mental health and wellbeing concerns with parents, and strategies were required to support these types of emotions if effective mental health support was to be provided to families [Citation42].

Key workers’ and managers’ perceptions of supervisory support were significantly improved by the intervention and this improvement was most apparent in ratings for “My supervisor strongly considers my goals and values” and “Help is available from my supervisor when I have a problem”, which is a critical component of job satisfaction and job-related wellbeing that will have positive flow-on effects for staff-client interactions [Citation43].

We observed positive trends in improved self-reported parental mental wellbeing and satisfaction with the service. Previous research conducted with families in the UK showed key workers carrying out more aspects of the key worker role, such as appropriate contact with families, regular training, supervision and peer support, and having a dedicated service manager and a clear job description were associated with better outcomes for families [Citation44]. Research conducted in Australia has also shown that health promoting activities aimed at mothers of children with a disability, such as encouraging prioritizing oneself, strongly predicted maternal mental health [Citation45], which aligns with our positive psychology training module. This intervention was unable to demonstrate a statistically significant effect on improved parental mental wellbeing as anticipated in the study’s program logic model [Citation25], which may be attributed to the scale and timeframe of this study. The training modules for key workers included information on referral pathways. We anticipate that for those parents experiencing high levels of distress, a longer timeframe receiving professional support would be required to see marked improvements. As the scale used to measure parental satisfaction with the service is unvalidated, this positive trend is a speculative finding with limitations in generalisability for other ECIS. Measurement of job-related affective wellbeing, and mean levels of key worker sick leave demonstrated positive trends due to the intervention but did not achieve statistical significance. From a program logic perspective [Citation25], there are credible grounds to anticipate positive changes in these parameters. There are important components of the intervention that prioritise staff wellbeing through the promotion of debriefing after stressful client interactions and the increase in knowledge, skills and confidence to approach the topic of wellbeing with parents - therefore decreasing stress associated with managing parental distress. As we did not investigate if the increased self-efficacy to support parental wellbeing and the improved parental mental wellbeing outcomes are mediators of wellbeing and sick leave, further exploration of these relationships and sick leave taken by staff would be advantageous to explain absences from work. Other research [Citation39] has suggested that meaningful work increases work engagement, and subsequently low levels of absenteeism. The test for cost-effectiveness then moves to the criterion of whether the net cost of the intervention is demonstrated as being ‘worth’ the benefits achieved. There is no easy yardstick here, of say ‘$50,000 per QALY’ being value for money (as in Cost Utility Analysis) or benefits measured in dollars being higher than the cost (as in Cost Benefit Analysis), as these forms of economic evaluation were not suited to the aims and objectives of the intervention. Cost consequences analysis – the form of economic evaluation adopted here – is suited to situations where the benefits are diverse and not easily amenable to combination into a single metric (QALYs or dollars). This leaves the judgement of ‘worth’, however, to the decision-maker. In other words, the answer to the question of whether cost-effectiveness was achieved, depends upon whether the benefits reported above, particularly those that achieved statistical significance, were assessed by the organisation as ‘worth’ the net cost of the intervention. Within the changing Australia disability provider environment, this intervention was deemed worthy by the partner organisation for ECIS services where the key worker role, in a family centred paradigm, is central to service delivery for the child and family. The evidence generated through this trial will be used to advocate to the NDIS for the key worker role to be the default funded method of service provision for children and families requiring early intervention. There are also the unmeasured economic costs to individuals and families when they experience ongoing stress. An intervention such as this, has potential longer-term benefits and would warrant further longitudinal exploration of the impact of training on long term mental wellbeing.

Providing professional development to key workers about the importance of recognizing and supporting parental distress within the family setting, and the implications on child development if parental distress is not actively identified and addressed, was however novel to this key worker cohort. We hypothesized that parents would use more mental health services because their key worker was able to guide them to this support if needed. However, our findings indicated no statistically significant increase in service utilisation by parents. The training also included the importance of seeking support for staff’s own well-being due to the potential for burnout and stress associated with working in a complex environment.

The positive findings of this trial suggest there is a need for parents’ wellbeing to be supported, which is easily accommodated within the family-centred, key worker service delivery framework [Citation46]. There may be reduced ability to provide this holistic service if allied health support for children aged 0–6 years with a disability or developmental delay is provided as ‘therapy-only’ rather than the key worker service within NDIS plans.

Strengths and limitations

The successful conduct of a partly randomised trial using a stepped wedge design with ECIS staff and parents of children with a disability, while experiencing disruptions to their usual service due to the NDIS disability service reform, is considered a strength of this study and shows the commitment of the disability organisation to building evidence to guide practice. Recruitment via the relationships with key workers enabled parents to be engaged in this study, although participant numbers were still quite low. We assume this to be due to parents of a child with a disability or developmental delay historically being a difficult cohort to engage in longitudinal research due to caring demands and the wellbeing issues they encounter [Citation47], although retention of parents in the study was pleasing with 76% completing the final survey. The use of REDCap allowed access to surveying parents easier but meant that some families with limited technology and reading literacy may have chosen not to participate for this reason, highlighting potential socio-economic differences in the possible sample of participants.

As is common in research conducted in community and service delivery settings, issues arose that impacted on adhering to the study protocol, in this case the study timeline. Due to organisational priorities or competing demands affecting individual hubs the delivery of the training in adherence to the planned stepped wedged 3-month sequence was impacted, with some of the later training dates being delayed. All measures were taken for the hubs to receive the intervention as soon as possible once they were allocated to cross over from the control group. These delays are evident in the nominated 6-month repeated measures being conducted at the 8-month mark and the nominated 9-month, and final, repeated measures being conducted 12-months post baseline (). The roll out of the NDIS, which occurred at varying times for each hub during the trial, was a potential confounder to the results, as the delivery of the key worker model by staff shifted in many cases to child therapy-only for those children who became NDIS participants. The timing of uptake of the NDIS within each hub was patchy, with the scheme rollout delayed at each planned timepoint. Therefore, we could not adjust for the impact of this disruption to service delivery on individual parent-keyworker dyads. The varied uptake of the NDIS by individuals may have added to the variability in outcome measures for key workers and parents.

The primary outcome measure, Key Worker Confidence (KWC), is a new measure based on there being ‘no all-purpose measure of perceived self-efficacy’ [Citation29]. It was out of scope to conduct a validation study of the measure, and we acknowledge the limitation this then has to the generalisability of the findings. The reliability of the measure was demonstrated by very high internal consistence with Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93.

Keyworker outcome means were consistently highest after initial program exposure, which may suggest there was an attenuation in program impact over the study period following the initial intervention. If so, this would reduce the power to find overall differences significant. Future studies examining similar interventions could consider repeated staff training sessions as a way of increasing and consolidating program impacts.

We surmise that the pragmatic constraints, one service with six hubs, and the sample size of parent participants will have impacted the findings. Future investigations to assess the generalisability of the intervention to other ECIS services is warranted given the observed positive trends across the measures.

Conclusions

Given the evidence for mental health and wellbeing issues experienced by some parents of a child with a disability and perceived low self-efficacy by key workers to support this, an intervention was developed to trial a strategy to build the confidence of key workers to support parental mental wellbeing during routine home visits.

Overall, the results of this trial indicated that the provision of capacity building training for staff has considerable potential and applicability for organisations promoting the ongoing wellbeing of both clients and staff. Although service delivery models were changing for ECIS, the commitment to addressing parental mental wellbeing was demonstrated through the implementation of the intervention. Evaluation indicated that a multi-pronged approach through tailored professional development, resource development and sustainability measures can increase organisational and staff capacity to address parental wellbeing. Improvements observed in key worker confidence to discuss and support the mental wellbeing concerns of parents, coupled with significant improvements in two items (G and H) in the “Knowing Domain”, as a result of receiving tailored training, as well as non-significant improvements in other items (F and J) is a critical finding that has positive implications for the uptake of the intervention program by other ECIS and early childhood organisations.

From an overall economic perspective, there were positive signs, but not clear-cut cost-effectiveness. Certainly, the small falls in staff sick leave achieved a minor cost offset, but the intervention did not provide a net financial benefit to the organisation. In any broader application, therefore, this suggests that cost-effectiveness for the provider would depend upon whether the benefits reported above, particularly those that achieved statistical significance, were assessed by management as ‘worth’ the net cost of the intervention.

This study confirms the critical need for: i) the transdisciplinary key worker role to be expanded to include support for parental mental health and wellbeing; ii) for professional development and organisational support to be provided to ECIS staff to ensure they have the skills and ability to support parental wellbeing through this role; and iii) for this holistic service to be available for families with children aged 0–6 years with a disability or developmental delay, even if ‘therapy-only’ services rather than a ‘key worker’ are included within NDIS plans.

Supplementary_Material.docx

Download MS Word (34.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of our colleague and friend, the late Professor Elizabeth Waters, who founded this study in partnership with Yooralla to enhance the health and well-being of children with a disability and their families through improved support services. We acknowledge Dr Elise Davis and Dr Kim-Michelle Gilson during their employment at The University of Melbourne; Jennifer Morgan, Adjunct Professor Jeffrey Chan, Jenifer Morris-Cosgriff and Elaine Krassas from Yooralla for their key contributions to the study, particularly the design and delivery of the intervention. We thank the Melbourne Clinical and Translational Sciences research platform for the administrative and technical support that facilitated data collection via REDCap. The authors would lastly like to acknowledge the generous contribution by parents and staff members from Yooralla who willingly participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

Authors R Carr, PK, CK were employees of the partnering organisation and JT is a Board Member of the partnering organisation.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gilson KM, Davis E, Johnson S, et al. Mental health care needs and preferences for mothers of children with a disability. Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44(3):384–391. May 1

- Yamaoka Y, Tamiya N, Moriyama Y, et al. Mental health of parents as caregivers of children with disabilities: Based on japanese nationwide survey. Lin H, editor. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145200. Dec 21

- Narramore N. Meeting the emotional needs of parents who have a child with complex needs. J Children Young People Nurs. 2008;2(3):103–107.

- Falk NH, Norris K, Quinn MG. The factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression in the parents of children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(12):3185–3203.

- Bourke-Taylor H, Howie L, Law M, et al. Self-reported mental health of mothers with a school-aged child with a disability in Victoria: a mixed method study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48(2):153–159.

- Byrne MB, Hurley DA, Daly L, et al. Health status of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Devel. 2010;36(5):696–702. Sep 1

- Ware ME, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to score version 2 of the SF-36 health survey (standard & acute forms). Lincoln (RI): Quality Metric Incorporated; 2001.

- Ryan C, Quinlan E. Whoever shouts the loudest: listening to parents of children with disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2018;31:203–214.

- Early Childhood Intervention Australia. Best practice in early childhood intervention: National guidelines. Sydney: Early Childhood Intervention Australia; 2016.

- Dunst CJ, Trivette CM, Hamby DW. Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(4):370–378.

- Trivette CM, Dunst CJ, Hamby DW. Influences of Family-Systems intervention practices on Parent-Child interactions and child development. Top Early Childhood Spec Educ. 2010;30(1):3–19.

- Rosenbaum PL, King SM, Cadman DT. Measuring processes of caregiving to physically disabled children and their families. I: Identifying relevant components of care. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34(2):103–114.

- Gilson KM, Johnson S, Davis E, et al. Supporting the mental health of mothers of children with a disability: Health professional perceptions of need, role, and challenges. Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44(5):721–729. Sep 1

- Council of Australian Governments. National disability strategy 2010-2020. Canberra (ACT): Council of Australian Governments; 2010.

- Brien J, Page J, Berman J. Enabling the exercise of choice and control: how early childhood intervention professionals may support families and young children with a disability to exercise choice and control in the context of the national disability insurance scheme. Austr J Early Childhood. 2017;42(2):37–44.

- National Disability Insurance Agency. NDIS price guide 2019-20. Vol. 1.3. Australia: National Disability Insurance Agency; 2019.

- Joint Standing Committee on the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Progress report 2019. Canberra (Australia): Joint Standing Committee on the National Disability Insurance Scheme; 2019.

- Gavidia-Payne S. Implementation of Australiaʼs national disability insurance scheme: experiences of families and young children with disabilities. Infants Young Children. 2020;33(3):184–194.

- Boaden N, Purcal C, Fisher K, et al. Transition experience of families with young children in the Australian national disability insurance scheme (NDIS). Austr Soc Work. 2021;74(3):294–306.

- Purcal C, Hill T, Meltzer A, et al. Implementation of the NDIS in the early childhood intervention sector in NSW: final report (SPRC report 2/18). Sydney (Australia): Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW; 2018.

- Bailey DB, Hebbeler K, Spiker D, et al. Thirty-Six-Month outcomes for families of children who have disabilities and participated in early intervention. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1346–1352.

- Gavidia-Payne S, Meddis K, Mahar N. Correlates of child and family outcomes in an Australian community-based early childhood intervention program. J Intellectual Developmental Disab. 2015;40(1):57–67.

- Young D, Gibbs L, Gilson K, et al. Understanding key worker experiences at an Australian early childhood intervention service. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29(6):1–10.

- Young D, Davis E, Gilson KM, et al. Developing a new service model for children with a disability: What do parents want? J Intellect Disab Res. 2016;60(7):765.

- Davis E, Young D, Gilson KM, et al. A capacity building program to improve the Self-Efficacy of key workers to support the Well-Being of parents of a child with a disability accessing an early childhood intervention service: Protocol for a Stepped-Wedge design trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(4):e12531.

- Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007; Feb 128(2):182–191.

- Hemming K, Taljaard M, McKenzie JE, et al. Reporting of stepped wedge cluster randomised trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement with explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2018;363:k1614–26.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381.

- Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F, Urdan T, editors. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents [internet]. Greenwich (CT): Information Age Publishing; 2006. p. 307–337. https://www.uky.edu/∼eushe2/Bandura/BanduraGuide2006.pdf

- Stewart-Brown S. The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS). NHS Health Scotland, University of Warwick and University of Edinburgh; 2008.

- Warr P. The measurement of wellbeing and other aspects of mental health. J Occup Psychol. 1990;63(3):193–210.

- Warr P, Bindl UK, Parker SK, et al. Four-quadrant investigation of job-related affects and behaviours. Euro J Work Organiz Psychol. 2014;23(3):342–363.

- Warr P. IWP multi-affect indicator. Institute of Work Psychology, University of Sheffield; 2016.

- Warr P. Work, happiness, and unhappiness. New York (NY): Routledge; 2007.

- Eisenberger R, Stinglhamber F, Vandenberghe C, et al. Perceived supervisor support: contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(3):565–573.

- Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, et al. Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(3):500–507.

- Kessler RC, Ames M, Hymel PA, et al. Using the world health organization health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect workplace costs of illness. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(6 Suppl):S23–S37.

- Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, et al. The world health organization health and work performance questionnaire (HPQ). J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45(2):156–174. Feb

- Soane E, Shantz A, Alfes K, et al. The association of meaningfulness, Well-Being, and engagement with absenteeism: a moderated mediation model. Hum Resour Manage. 2013;52(3):441–456.

- VSN International. Genstat for windows. Hemel Hempstead: VSN International; 2018.

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 16. College Station (TX): StataCorp LLC; 2019.

- Laletas S, Reupert A, Goodyear M, et al. Pathways of care: targeting the early childhood sector for early intervention. Advances in Mental Health. 2015;13(2):139–152. 3

- Moore T. The nature and role of relationships in early childhood intervention services. In: Second conference of the international society on early intervention. Zagreb (Croatia): International Society on Early Intervention; 2007.

- Sloper P, Greco V, Beecham J, et al. Key worker services for disabled children: what characteristics of services lead to better outcomes for children and families? Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32(2):147–157.

- Bourke-Taylor H, Pallant J, Law M, et al. Predicting mental health among mothers of school-aged children with developmental disabilities: the relative contribution of child, maternal and environmental factors. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(6):1732–1740.

- Moore T. Rethinking early childhood intervention services: Implications for policy and practice. In: Pauline McGregor memorial address presented at the 10th biennial national conference of early childhood intervention Australia, and the 1st Asia-Pacific early childhood intervention conference. Perth (Western Australia): Murdoch Childrens Research Institute and The Royal Children’s Hospital Centre for Community Child Health; 2012.

- Adams D, Handley L, Heald M, et al. A comparison of two methods for recruiting children with an intellectual disability. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2017;30(4):696–704.