Abstract

Purpose

People living with stroke and neurological conditions access rehabilitation at different times but self-management is often viewed as what happens post-discharge. Personalised models that integrate self-management support within everyday care are now advocated but this may require practitioners to change their behaviour to adopt and sustain new ways of working. The People1st project evaluated integration of an existing Supported Self-Management programme (“Bridges”) across varied stroke and neurorehabilitation service contexts.

Materials and methods

Mixed-method evaluation of training for groups of healthcare practitioners across 24 UK National Health Service (NHS) Trusts, exploring how learning from Bridges was assimilated and enacted in practice, on an individual and collective basis.

Results

Staff growth in confidence and skill around supported self-management was demonstrated. Transformations to practice included changes to: the structure of, and language used in, patient interactions; induction/training processes to increase potential for sustainability; and sharing of successes. Bridges helped practitioners make changes that brought them closer to their professional ideals. Engaged leadership was considered important for successful integration.

Conclusions

Bridges was successfully integrated within a wide range of stroke and neurorehabilitation service contexts, enabled by an approach in line with practitioners’ values-based motivations. Further work is required to explore sustainability and impact on service users.

Personalised models of care and support for self-management are advocated for people living with stroke and neurological conditions; this requires practitioners to be supported to change behaviour and practices to adopt and sustain new ways of working.

Staff from a wide variety of backgrounds in neurorehabilitation and stroke can learn collaboratively about self-management practices via the Bridges programme and can integrate those practices into their service contexts.

Bridges can take practitioners closer to their professional ideals of caring and making a difference and empowers them to initiate change.

Organisational commitment and engaged leadership are required to facilitate a culture of support for self-management in practice.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

People with stroke and neurological conditions have some of the most complex care needs of those living with long-term conditions (LTCs) [Citation1], and inevitably experience healthcare and rehabilitation in systematically complex and professionally diverse contexts [Citation2]. It is, therefore, unsurprising that support for people living with LTCs such as stroke has been a feature of health and social care policy narrative since 2014 and continues to be addressed in the NHS Long Term Plan for England [Citation3]: whilst the focus is on helping people to stay independent for longer and preventing emergency admissions there is also a strong emphasis on advocating more personalised approaches to care and rehabilitation. For people living with an LTC, it is now widely acknowledged that complex needs will not be met with a “one size fits all,” condition-specific approach orientated around professional expertise – rather that outcomes and experiences improve when people are involved in shaping care around their own strengths and preferences [Citation3,Citation4].

One prominent strand of current healthcare policy is, therefore, a move from directive paternalistic practices to personalised models of care. Such models require shared emphasis on improving the knowledge, skills, and confidence of people to live well and manage their condition, such as through support for self-management, and on workforce transformation through development and training to support new models of care [Citation4–6].

People living with stroke and neurological conditions will access care and rehabilitation at different times but self-management is often viewed as what happens after discharge. As personalised models of care which integrate self-management support within everyday care are now advocated, there is a requirement for such approaches to feature in the entire patient pathway; but this may require practitioners to change their behaviour and adopt new ways of working. An interprofessional, democratic approach is required with elements that enable the expertise and contributions of all professionals to be valued equally, in order to work together around a common aim [Citation7], supported by evidence-based training and development. “Bridges” is one such staff training approach [e.g., Citation8,Citation9], co-created with service users to address the need for more personalised care for people with stroke in multiple contexts. Bridges involves staged training for interprofessional groups of practitioners to integrate self-management language and techniques into everyday practice [Citation8]. Whilst Bridges is a well-established approach to supported self-management, the mechanisms by which implementation and sustainability might be achieved are less well known [Citation8] and detailed evaluation in a variety of settings is indicated.

Almost all changes in healthcare, particularly those that require uptake and adoption by multiple professional groups, such as a shift to more personalised care through self-management training, can be considered a complex intervention with several interacting components [Citation8–10]. However, development and evaluation of any such intervention that requires changes in behaviour of practitioners requires contextual relevance and tailoring to local circumstances of healthcare teams and organisations [Citation11]. This also requires an understanding of staff learning needs, to develop the broader expertise required to implement and sustain change. Theoretical models, such as the Normalisation Process Model (NPM) a middle-range sociological theory can help to conceptualise how new innovations in healthcare are implemented, embedded, and sustained and understand factors that act as barriers or enablers for routine incorporation of complex healthcare innovations into practice [Citation12].

When gaps exist between goals and application in daily working practice, even pathways considered “gold standard,” such as Liverpool End of Life (EOL) Care, have received criticism for not studying the process of implementation [Citation13]. Noble et al. explore how EOL care excellence was embedded and normalised into acute healthcare settings, and advocated that learning used for training should use strategies informed by NPT [Citation13]. Other projects have used NPT to guide the roll-out of new ways of working in practice such as the SMART MOVE study, which promoted physical activity through a pedometer app and highlighted the need to understand not only the intervention itself but the context in which it is applied [Citation14].

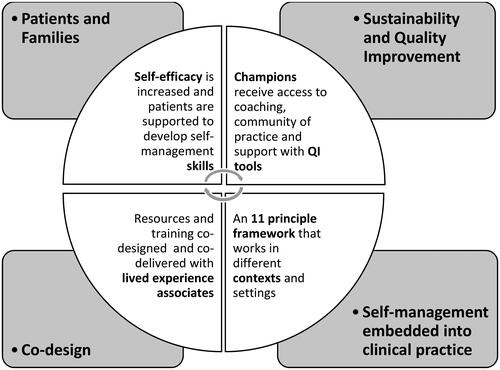

It is clear that there is a need to support new models of personalised care in stroke and neurorehabilitation with evidence-based training and development; and to evaluate those programmes using appropriate theoretical frameworks to enhance new ways of working. In the People1st Quality Improvement (QI) project presented here, our complexity was how to integrate an existing, person-centred, evidence-based approach to self-management (“Bridges”), working with an interprofessional workforce with similar and different organisational structures and processes – to deliver care for individuals with stroke and neurological conditions. Bridges is theoretically grounded in self-efficacy and underpinned by co-production and co-design. Bridges delivers training and coaching to healthcare teams and focuses on the skills, attitudes, and knowledge of practitioners, aiming to transform therapeutic relationships with patients and facilitate collective change within teams and service pathways.

Evidence from research and QI projects has shown Bridges impact on the confidence and skills of patients, and changes in attitudes and practices of practitioners across different healthcare pathways [e.g., Citation8,Citation9].

Aim and evaluation questions

The overarching aim was to evaluate the integration of a Supported Self-Management programme (“Bridges”) into a wide variety of stroke and neurorehabilitation service contexts, from acute to community settings.

Specific evaluation questions were:

How does Bridges enable practitioners to change their practice?

Does Bridges increase practitioner skills and confidence in providing personalised self-management support?

What changes to individual and collective practice are enacted following the training and what are the perceived benefits of using Bridges?

What are the barriers and facilitators to integrating personalised self-management support into stroke and neurorehabilitation practice?

Methods

Setting

The People1st project took place in six Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) in East of England. STPs were established as health and care collaborations between the UK National Health Service (NHS) and local government services in 2016, later evolving Integrated Care Systems (ICS), with responsibility for providing more efficient and joined-up care tailored to local health needs [Citation15]. All NHS Trusts providing stroke and neurological services were invited to participate in Bridges training. The project, funded by Health Education England, offered 125 training places in each STP.

Design

The evaluation focused on the assessment of adult learning and how healthcare practitioners, both on an individual and collective basis, assimilated and enacted learning from Bridges in their practice. A mixed method evaluation was employed, using pre- and post-training practitioner questionnaires, non-participant observation of training, and practitioner interviews.

Theoretical frameworks

The evaluation used two complementary theoretical frameworks to help shape methods and interpret findings, chosen to provide a breadth of empirical insights in relation to individual and collective learning [Citation16].

First, Kirkpatrick’s Model of Learning Evaluation [Citation17] informed the assessment of adult learning principles. Widely used in medical training evaluation it includes four levels: (1) reaction to the training, (2) learning, (3) how learning translates into behaviour change, and (4) the results or impact of the behaviour change.

Further, the four generative mechanisms of Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) [Citation18,Citation19] were used as an additional organising framework to help guide the evaluators’ understanding of the process of implementation of Bridges into everyday practice, considering factors external to the training programme. This encompassed how practitioners made sense of (Coherence) and engaged with (Cognitive Participation) Bridges, how they sought to implement and sustain Bridges in their individual and collective practice (Collective Action), and how they sought to appraise the value of using the approach (Reflexive Monitoring). describes NPT’s generative mechanisms and their respective subconstructs in relation to activities and outputs of the People1st project.

Table 1. Description of normalisation process theory (NPT) generative mechanisms and subconstructs aligned to the People1st project.

Project inclusion criteria

All practitioners involved in delivering stroke and neurorehabilitation services were eligible to take part in Bridges training, including professionally qualified nurses and allied health professionals, medics, and support staff (healthcare and therapy assistants). Service leads allocated staff to training places. The embedded evaluation included only those practitioners from NHS Trusts providing governance approval.

A convenience sample from those attending training in each STP took part in telephone interviews.

The Bridges programme

Bridges provides a unifying approach to supporting self-management that is integrated into healthcare interactions (). Based on a series of research and QI studies in stroke, it has now been adapted for use with patients with multiple conditions including brain injury, and neuromuscular disease [Citation9,Citation20–22]. Essentially, the focus is on facilitating practitioners’ behaviour change to prioritise what is most important and meaningful to patients during healthcare interactions, and use language and techniques to support self-management [Citation20]. Underpinned by Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory [Citation23], practitioner interactions are used to support patient’s self-efficacy through facilitating activities such as goal mastery, problem-solving, and reflection. Within Bridges, self-management support is viewed as a continuum depending on patient needs and capabilities. This means that practitioners learn how to adapt support for individual patient needs such as communication and cognitive difficulties, and to tailor their approach so it can start at any point in a patient’s recovery including the acute phase post-stroke [Citation21].

Figure 1. Bridges: a unifying approach to supporting self-management.

Bridges facilitates behaviour change in everyday healthcare practice through in-action reflection on interactions with patients and families, the use of vignettes of patients living with LTCs and case examples of strategies used by other practitioners and teams to illustrate new ways of working. Bridges promotes integration of self-management principles into everyday therapeutic language, so support becomes “a way of working” rather than an add-on to everyday practice.

Discovery interviews, delivered by members of the Bridges team, prior to training commencing, enable an understanding of key drivers for different practitioner groups, as well as organisational challenges. These interviews are a routine part of Bridges processes. Training is co-delivered by experienced Bridges practitioners and people with lived experience of LTCs. Practitioners consider theory, research, and evidence base for self-management along with their own individual targets and actions plans for practice change. At the time (pre-pandemic) training was delivered face-to-face to interprofessional groups from the same team or service pathway via a full-day workshop (“Knowledge Zone 1”) and a half-day follow-up workshop (“Knowledge Zone 2”). A 12-week “transition phase” between workshops gives participants time to implement the techniques in clinical practice, and receive continued support through access to online resources and coaching from Bridges facilitators. To support successful implementation and sustainability [Citation6,Citation24], Masterclasses are held 6–12 weeks after Knowledge Zone 2 (KZ2) for small groups of practitioners (“Champions”) who have expressed interest and enthusiasm in promoting and sustaining the adoption of Bridges in their service. At the Masterclasses, the Champions share key changes made within their services, reflect on successes and challenges in implementing changes to team practice, and discuss the development of local plans for sustainability and evaluation.

Evaluation data generation

To gain a breadth of insights into development of skills, practice changes and barriers and facilitators to adoption, questionnaires, observations, and interviews were used. presents the tools used to explore the evaluation questions, aligned to each project stage and the theoretical frameworks used to underpin interpretation. The tools are described below.

Table 2. People1st data collection tools and content aligned to project stages and evaluation aims.

Questionnaires

Bespoke questionnaires were developed and administered at three time points: pre- and post-Knowledge Zone 1 (KZ1) and post-KZ2.

Practitioners’ confidence and performance in supported self-management were assessed prior to initial training and at completion by means of 18 statements from the Self-Efficacy and Performance in Self-Management Support (SEPSS-36) instrument [Citation25], mapped to the Bridges 11 core principles ().

Table 3. Bridges 11 principles framework.

The Normalisation MeAsure Development (NoMAD) tool [Citation26] was used for implementation assessment: statements relating to coherence and cognitive participation were measured at the end of KZ1, and collective action and reflexive monitoring were measured at the end of KZ2.

Workshop observations

The two members of the evaluation team (JH and NH) observed a third of the training workshops, attending as peripheral members [Citation27], i.e., they had no functional role but were introduced to attendees and gave an overview of evaluation activities. Field notes were taken (guided by Kirkpatrick and NPT frameworks – see ) and personal reflections about the session noted. All Masterclasses were attended by a member of the evaluation team.

Interviews

Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with a sub-sample of practitioners after the completion of KZ2. An interview topic guide was developed using NPT constructs to explore changes to individual and collective practice introduced following the training, the perceived benefit of the changes, and the barriers and facilitators to implementing supported self-management. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed using an intelligent verbatim approach.

Analysis

Quantitative data from the questionnaires were analysed by means of descriptive statistics, examining changes in confidence and performance of supported self-management tasks. Open text responses were categorised and analysed thematically.

A single coding approach was used for qualitative data (non-participant observations and interview data) [Citation28]. Data were coded directly against the headings of the four core constructs of NPT and their respective sub-components.

JH applied the coding framework to the first four interview transcripts and met with NH to review interpretation and coverage of the data, and to check consistency in coding to each of the constructs and subconstructs. The framework was found to accommodate the data and was applied to the full dataset.

Responses to the confidence and performance statements and NoMAD survey tool were triangulated against observation and interview data. Qualitative data were used to triangulate, elaborate and clarify quantitative responses to gain a more nuanced understanding.

Governance

Approvals for evaluation activities were granted by each participating NHS Organisation. Notification of all approvals were shared with the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Ethics Committee, University of East Anglia. Ethical principles were adhered to throughout the evaluation. All interviewees received a participant information sheet and provided informed consent prior to interview.

Results

Participation

Twenty-eight trusts were invited to participate and staff from 24 Trusts attended the Bridges training workshops. Available evaluation data comprised: 553 pre-KZ1, 539 post-KZ1, and 432 post-KZ2 questionnaires; 24 interviews with staff; and 102 h of observations. summarises total numbers of participants by profession and work setting in each training session. Fewer nurses and healthcare assistants attended than therapist groups due to staffing pressures.

Table 4. Participant practitioner group and work setting.

Twenty-four practitioners participated in telephone interviews. Interviewees had a mean of 18 years (SD 1–34) in their profession and a mean of 9 years (SD 1–20) in their current service.

Evaluation findings

Findings are reported according to the evaluation questions stated at the end of the introduction, under the following headings: learning experience, and motivating and enabling changes to practice (question 1), changes in practitioner confidence and skills (question 2); workforce transformation-changes to individual and collective practice (question 3); barriers and facilitators to implementing supported self-management into daily practice (question 4).

Evaluation question 1: learning experience, motivating and enabling changes to practice

Observations illustrated key areas which contributed to a positive learning experience including: level of interactivity and group work, use of the “patient voice” (through patient videos and co-delivery of training by people living with LTCs) and “peer voice” (practitioner video examples of using Bridges principles). Analysis of open text questionnaire responses at the end of KZ1 supported these observations, highlighting practitioners’ appreciation of space away from clinical demands to reflect on practice with other service members, acknowledgement of the credibility and enthusiasm of the trainers, and the value of hearing patient perspectives. Similar themes emerged from the practitioner interviews.

Hearing stories from patients … I found that very powerful. It makes it relevant to us and brings it home. That’s what made a big difference. It was people who had been through it saying that’s what worked for them. (Int #22, Physiotherapist, Early Supported Discharge and Community Services)

In the workshops and during interview, practitioners also reflected on how they had been reminded of aspects of practice that had been forgotten or eroded as a result of day-to-day pressures and they were prompted to re-examine and to change aspects of their approach.

I think [the training] is self-reflective for practitioners. It gets you to analyse your own practice and reflect upon the words that you have used and the patients where perhaps you haven’t been able to engage them very well. I think it’s just very good at making people reflect upon their practice and then also think about other ways and methods. (Int #24, Physiotherapist, Community Service)

Prior to KZ1, practitioners were asked to describe the professional ideals that had attracted them to work in healthcare. Categorisation of the questionnaire responses revealed two main intrinsic motivations: (1) caring for and helping others (i.e., improving quality of life, promoting independence and “making a difference”) and (2) professional opportunities (i.e., developing self and practice, collective working and contributing to quality of care). At the end of KZ1 training, 94% of practitioners agreed or strongly agreed that Bridges would help them to make changes to their practice that would bring them closer to those professional ideals.

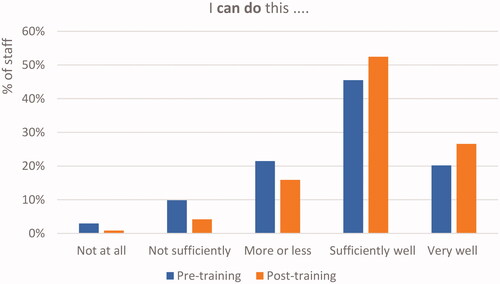

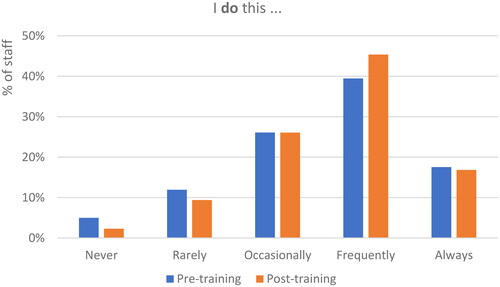

Evaluation question 2: changes in practitioner confidence and skills in providing self-management support

Practitioner learning was assessed by means of self-reported confidence in (I can do this …) and performance of (I do this …) 18 Supported Self-Management tasks. and show the percentage of questionnaire responses in each category pre-KZ1 and post-KZ2, indicating a positive shift in confidence and performance.

Figure 2. Practitioner confidence in 18 supported self-management tasks pre- and post-initial training (n = 553).

Figure 3. Practitioner performance of 18 supported self-management tasks pre-and post-training and initial implementation period (n = 432).

Insights into the process of change in practitioners’ confidence were evident from workshop observations and interview data. This was not always immediate and revealed some initial discomfort as practitioners stepped out of their comfort zone or default mode.

I think it’s having more confidence with the approach, because it becomes more natural. So when I had my very early on conversations with Bridges it felt quite slow and I was really having to think quite hard on my feet, whereas yesterday doing this “to do list” [with patient] it almost came quite naturally. I think the more you use the model, it becomes more of your natural everyday questioning. So I think the more you use it the better. (Int #20, Occupational Therapist, Acute Stroke Unit)

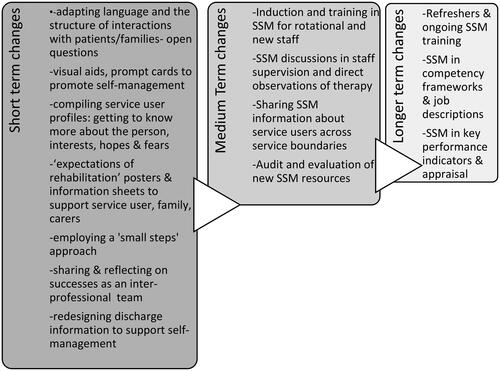

Evaluation question 3: workforce transformation: changes to individual and collective practice

A range of enacted and planned changes to integrate Bridges into practice were described in the KZ2 workshops, post-training open text questionnaire responses and interview data, summarised in .

Figure 4. Enacted and planned changes to practice.

Short term changes included altering language to support self-management during practitioner–patient interactions, and devising prompt cards or other reminders (e.g., posters in staff room) to support change. Practitioners described focusing goals and therapy sessions around what is important to the patient taking into account previous life history and interests. Visual aids in the environment were used as a mechanism to build awareness of self-management and to help manage expectations of rehabilitation (of patients, families, and staff). Sharing information and success stories in team meetings was considered critical to maintaining enthusiasm generated by the training, allowing practitioners to support each other through the change process. These short term “quick fixes” were regarded as important to maintain the momentum for change, accompanied by longer term plans to incorporate self-management language and strategies into paperwork, processes and systems (e.g., audit and appraisal).

Changes over the medium and longer term centred around the need to ensure sustainability of supported self-management within teams, across service boundaries and within organisations.

What was the perceived impact of sharing control with patients?

Knowledge Zone 2 observations and interview data identified that practitioners perceived a range of benefits in using Bridges.

Practitioners reported greater enjoyment in working collaboratively with patients, feeling less pressure to have all the answers. Examples were provided of how the approach had helped in the delivery of more meaningful therapy to patients who found engaging with rehabilitation more challenging. Practitioners perceived that patients and their family members felt more listened to, were reassured that their hopes and fears had been acknowledged, and that their specific needs were being addressed. As a result of the changes to their interactions with patients, practitioners reported that they felt they were providing more effective and efficient therapy leading potentially to better outcomes, and reducing a sense of frustration about their efforts going to waste.

I am feeling a lot less responsibility in a way, whereas before you sometimes felt that the only way anything was going to happen was you would have to go and be the expert and tell them what to do, whereas for lots of people it has been “what do you think is going to work for you?” … and I have been giving a lot less ideas to people … and it’s a bit more powerful if someone comes up with the ideas themselves and then they are more committed to it. (Int #1, Occupational Therapist, Early Supported Discharge and Community Services)

Importantly, practitioners also stated that they had greater satisfaction from the emphasis on putting the patient at the centre of rehabilitation and felt they were able to regain aspects of practice that had been eroded by system pressures.

My approach to patients hasn’t changed over the years … I would say it’s the system of how we treat patients that has changed, so the Bridges for me just sort of brings it back to being how it should be. (Int #10, Ward Sister, Acute Stroke Unit)

In the KZ2 workshops and in the Masterclasses, practitioners noted that the programme had demonstrated how small changes to practice had a big impact on patients and staff, and 91% agreed or strongly agreed with the post-training questionnaire statement that Bridges Supported Self-Management had enabled them to make changes to their practice to bring them closer to their professional ideals.

In addition to greater collaboration with patients, practitioners also noted that Bridges promoted better communication and sharing within their teams, reduced silo working and eliminated repetition. Collaboration was facilitated by having a shared language and using Bridges in multi-disciplinary meetings to discuss how to support patients in working towards their goals.

When we were redesigning the goal sheet … we were thinking it might be a joint kind of goal. It can be something that all of us are interacting with, so make that a bit more, like, ‘this is your goal, so how can we support that?’ So that will be a bit more of a conversation and I think that is probably what used to happen, a lot more collaboration between you. (Int #1, Occupational Therapist, Early Supported Discharge and Community Services)

Within our weekly MDT (multi-disciplinary team) we are trying to say what are we, what kind of Bridges approaches are we taking with these particular patients, often the patients and families who are very complex. So we are trying to support each other when we’re talking about a complex patient. (Int #6, Occupational Therapy Lead, Community Services)

Evaluation question 4: barriers and facilitators to implementing supported self-management into practice

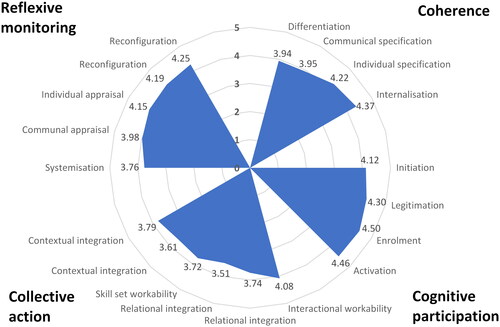

presents a radar diagram of mean scores for responses to the NoMAD tool, with higher scores representing more successful implementation or “normalisation” in relation to the subconstructs of the four generative mechanisms of NPT (see ). Supporting illustrative quotes from the qualitative dataset can be found as supplementary material (suppl. 1). In what follows, we address each NPT generative mechanism in turn, highlighting those subconstructs that point to successful or less successful implementation of Bridges.

Figure 5. Radar diagram illustrating mean responses to NoMAD survey tool (Likert scale – 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)).

Coherence

Practitioners understood how Bridges impacted their work (individual specification NoMAD mean survey score 4.22) and could see the potential value of the approach for their practice (internalisation score 4.37). Observation and interview data, confirmed that Bridges resonated with practitioners’ professional philosophies and intrinsic motivations for working in health care, and was seen as a way to reconnect with person-led, rather than service-led, practice.

Not all practitioners agreed with the statement “I can see how Bridges differs from my usual ways of working” (differentiation score 3.94). Observations revealed how some practitioners felt they were already using self-management principles in practice. However, further exploration through interviews illustrated this was not always consistent and reminders and developing deeper understanding were valued.

The communal specification subconstruct received a mean survey score of 3.95. Qualitative data indicated that practitioners felt Bridges should be integrated more widely (i.e., including medical staff, as well as those commissioning services and organising patient discharge) in order to have an enhanced impact on rehabilitation culture. However, achieving spread across the team was enhanced by sharing of success stories in team meetings, and through supervision and joint working between staff.

Cognitive participation

Initiation received the lowest mean survey score (4.12) in this construct. Observations identified the importance of leadership for engagement with Bridges and commitment to the change process. Some service and team leads acted as “Pre-Champion Champions” in signalling the value of the training to staff. They attended the workshops, introduced the Bridges and evaluation teams, and highlighted why the training was important for personal and service development. There were examples of team leaders encouraging their staff to take extra time to trial and embed new approaches (e.g., to goal setting), with the focus on the longer term patient benefit. However, some team leaders did not engage and practitioners reported their efforts to implement supported self-management without encouragement.

In the interviews, practitioners stated that the Bridges “Champions” and other Bridges enthusiasts would be key to maintaining visibility and helping to ensure sustainability. In some areas, these individuals had sought to share their Bridges learning with other services (e.g., orthopaedics and end-of-life care) where they perceived it would add value.

The other subconstructs in this mechanism had scoring consistent with more successful normalisation.

Collective action

Interactional workability received the highest mean survey score (4.08) in this construct. In the workshops and interviews, practitioners reported that they were able to incorporate Bridges tools and techniques readily into their practice, although recognised time was needed to build confidence such patients.

Confidence in colleagues’ support of and ability to use Bridges principles (relational integration) received relatively low mean survey scores (3.51 and 3.74, respectively), and practitioners expressed the view that it would take time to ensure that Bridges was appropriately cascaded throughout the wider teams. In the acute setting in particular, the view was that changing language and the nature of interactions with patients needed to be part of an ongoing process of culture change. The need for a consistent approach to interactions with patients was recognised, with the focus on enabling their confidence and independence. It was perceived that it was perhaps easier for therapists to embed Bridges in their practice because of the structure of their interactions with patients. In the workshops, nurses expressed the view that their more routinised task structure and greater time pressures gave less opportunity to explore key aspects of self-management such as problem solving and goal setting.

Similar concerns influenced responses to the issue of skill set workability (mean survey score 3.72). To overcome skill set barriers, practitioners initiated plans including: development of induction packs and videos, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) sessions to consolidate learning, ongoing refresher training, use of Bridges in supervisions, and plans for shadowing and direct observation of therapy. There were examples of acute stroke teams using Bridges principles to promote greater interprofessional collaboration when faced with complex decision making, e.g., issues such as swallowing, medication and clothing choice and continence management.

The availability of sufficient resources (survey score 3.61) and adequate management support (survey score 3.79) (contextual integration) was perceived to impact implementation through budgetary pressures, staff shortages in the acute sector, lack of protected time, and a lack of engagement in Bridges by managers and team leaders.

Reflexive monitoring

During the Masterclasses, the Bridges “Champions” outlined their plans for systematisation (survey score 3.76). Practitioners were concerned that existing assessment methods would not capture sufficiently the benefits of using supported self-management. Plans therefore included the development of new patient feedback questionnaires around self-management, as well as confidence-based rating scales (to be used before and after therapy as measurable outcomes, and in relation to preparation for discharge). Patient vignettes and stories were also perceived as a means to capture evidence of success with Bridges. However, the process of adoption of new measures by organisations as key performance indicators was challenging.

Informal communal appraisal and individual appraisal (survey scores 3.98 and 4.15, respectively) further identified value in using the approach for both practitioners and patients. Practitioners were very positive about the ease with which Bridges can be improved and adapted in the future (reconfiguration) (survey scores 4.19 and 4.25). The ability to use Bridges flexibly in line with patient characteristics, professional context or service context was felt to support implementation and the likelihood of sustainability.

Discussion

We were successful in meeting the overarching aim of the People1st QI project, by integrating a Supported Self-Management programme (“Bridges”) into a wide variety of stroke and neurorehabilitation service contexts, from acute to community settings. Further, by exploring four key evaluation questions with application of complementary theoretical frameworks, we were able to address an established gap in the current understanding of staff learning needs around supported self-management, and how staff use that learning to enhance services and care [Citation8]. Insights were gained into how staff from a variety of professional backgrounds could learn collaboratively about supported self-management practices, via an established approach originally developed for use by practitioners in stroke, and go on to integrate those practices into the wide variety of existing health-care pathways, processes and contexts in which people with stroke and neurorehabilitation needs might access care.

In considering how Bridges might enable change, the value of “learning together” in a collaborative, interactive manner, in a dedicated environment away from clinical demands, was recognised by practitioners. This “trialability space,” regarded as important in the assimilation of innovative approaches [Citation29] offered opportunities for practitioners to learn, experiment with and refine their knowledge together. Interactions across differing levels of practitioner skill and experience, and delivery via a facilitatory approach without “expert teaching,” are fundamental to Bridges. Such diffusion of professional silos and diminishing of the influences of hierarchy and power, are crucial in meeting identified challenges to successful interprofessional working and shared decision making [Citation30,Citation31]. However, whilst the training space here enabled a shared, non-hierarchical learning experience, we do not know if this necessarily translated into practice-based interactions due to the scope and nature of this QI work. Minimal attention has been given to the complex nature of support for self-managing as enacted in clinical practice, where role tensions and accepted “norms” surrounding healthcare professionals, may exert restrictive forces [Citation32], and further work in this area is indicated.

Growth in practitioner confidence and skill are crucial to integration of supported self-management in practice [Citation8] and, importantly, positive shifts in both were evident from the findings here. However, on deeper exploration, the process underpinning change was more complex as practitioners reflected on moving beyond their comfort zones and experiencing some discomfort alongside growth. The paradigm shift required to both let go of and share control as practitioners adopt supported self-management approaches is known to be challenging [Citation33], but here practitioners felt supported in making that shift, with Bridges training offering “permission” to change through multiple examples of “how others had done it” [Citation20]. This growth in confidence and skill may have implications beyond the integration of supported self-management – it is recognised that developing staff skill and expanding capabilities beyond traditional roles and approaches creates workforce flexibility and boosts morale [Citation3]. A powerful finding from our evaluation was the identified nature of Bridges in taking practitioners closer to their professional ideals of caring and making a difference [Citation34]. Enabling the patient voice through a creative and collaborative approach to care and rehabilitation, was perceived to be valuable and held meaning and resonance for practitioners, congruent with previous findings in similar services [Citation22]. Practitioners were instigating and sharing their proposed and enacted changes throughout the programme, rather than being the targets of change in a task-driven, pressurised service that prevents psychological, emotional and physical engagement with patients and their families [Citation35].

Our findings also suggested that, at the outset of the project, not all practitioners perceived the approach to be different to that which they would ordinarily adopt for people with stroke and neurorehabilitation needs. The idea that the integration of patient values and preferences in health decisions encouraged by Bridges is seen to be already occurring by practitioners is well-recognised [Citation6,Citation30] but not necessarily supported in practice [Citation30]. Possible reasons for this include a lack of understanding of all facets of shared decision making, and staff engaging in insufficient depth [Citation30]. These challenges were addressed and evidenced in the People1st project presented here, as staff learned and grew together, sharing their stories, their small steps to changing practice and their successes. Differences to usual care were gradually exposed with retrospective realisation [Citation6] and ideas for sustainability of the approach were explored.

In considering our findings on barriers to integration of supported self-management in practice, it was clear that practitioners considered a whole system approach is required, with strategies needed to empower practitioners themselves to initiate change; success or otherwise can be predicated on engaged leadership to facilitate that change. This resonates with previous work in rehabilitation services, where engaged leadership has been identified as crucial to supporting change [Citation8], and is considered a critical enabler of enacting change [Citation6]. Health and care leaders were considered a key resource in integrating and sustaining the approach in our project. Further work is required to understand the mechanisms by which leadership engagement might be improved across differing service contexts to drive change.

Strengths and limitations

People1st was a large-scale, QI project that used established methodologies and theoretical frameworks to evaluate the integration of an existing approach to supported self-management across a wide range of UK NHS service contexts. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest evaluation of supported self-management training undertaken in UK NHS services.

The project was affected to a degree by the COVID-19 pandemic. One follow-up workshop and one Masterclass was cancelled and the evaluation team was not able to access 45 follow-up questionnaires for inclusion in the data analysis. We also acknowledge the potential for participant bias as those recruited to interview were generally engaged with the Bridges programme and supportive of service change. Fewer nurses and healthcare assistants attended than therapist groups due to staffing pressures and we acknowledge the possible impact of this on our findings.

The scope of this evaluation did not permit direct assessment of impact on the main beneficiaries – patients and their families/carers. Further, with funding limited to allow only one Masterclass we were not afforded the opportunity to examine the role and effectiveness of the Bridges Champions in the embedding and sustaining change longer-term. Sustainability beyond the remit and timescale of this QI work is unknown.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrated that it is possible to integrate a Supported Self-Management programme (“Bridges”) into a wide variety of stroke and neurorehabilitation service contexts, and provided rich insights into the value of collaborative learning on supported self-management, the growth in confidence and skills of practitioners, and tangible transformations to individual and collective practices in stroke and neurorehabilitation services. We reported enabling factors such as collaborative inter-professional learning in a “safe space” to explore and develop knowledge, confidence, and skill, an approach in line with practitioners’ values-based motivations, and a need for engaged leadership and organisational commitment to the approach to reduce barriers to integration. This QI project has demonstrated need for future primary research to explore sustainability and direct impact on service users and families.

Supplementary_material_1.pdf

Download PDF (65.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all practitioners, service leads, and relevant NHS trust governance teams for their support for this initiative. We would like to acknowledge the team at HEE not only for funding this work, but for ongoing support throughout the project.

Disclosure statement

Professor Fiona Jones is the founder and CEO of Bridges Self-Management a social enterprise run in partnership with St Georges University of London and Kingston University. Dr Nicola Hancock and Julie Houghton have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Stroke Association, UK. State of the Nation Stroke Statistics; 2017. Available from: https://www.stroke.org.uk/sites/default/files/state_of_the_nation_2017_final_1.pdf

- Bonifacio GB, Ward NS, Emsley HCA, et al. Optimising rehabilitation and recovery after a stroke. Pract Neurol. 2022.

- NHS England. NHS long term plan; 2019. Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/

- NHS England. NHS universal personalised care: implementing the comprehensive model; 2019. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/universal-personalised-care.pdf

- Lazcano-Ponce E, Angeles-Llerenas A, Rodríguez-Valentín R, et al. Communication patterns in the doctor–patient relationship: evaluating determinants associated with low paternalism in Mexico. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21(1):125.

- Ahmad N, Ellins E, Krelle H, et al. Person-centred care: from ideas to action. London (UK): The Health Foundation; 2014.

- van Dijk-de Vries A, van Dongen JJJ, van Bokhoven MA. Sustainable interprofessional teamwork needs a team-friendly healthcare system: experiences from a Collaborative Dutch Programme. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(2):167–169.

- Kulnik ST, Postges H, Brimicombe L, et al. Implementing an interprofessional model of self-management support across a community workforce: a mixed-methods evaluation study. J Interprof Care. 2017;31(1):75–84.

- Jones F, McKevitt C, Riazi A, et al. How is rehabilitation with and without an integrated self-management approach perceived by UK community-dwelling stroke survivors? A qualitative process evaluation to explore implementation and contextual variations. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e014109.

- Skivington K, Simpson SA, Craig P, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council Guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061.

- Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, et al. Achieving change in primary care—effectiveness of strategies for improving implementation of complex interventions: systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009993.

- Huddlestone L, Turner J, Eborall H, et al. Application of normalisation process theory in understanding implementation processes in primary care settings in the UK: systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):52.

- Noble C, Grealish L, Teodorczuk A, et al. How can end of life care excellence be normalised in hospitals? Lessons from a qualitative framework study. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):100.

- Glynn LG, Glynn F, Casey M, et al. Implementation of the SMART MOVE intervention in primary care: a qualitative study using normalisation process theory. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):48.

- NHS England. Next steps on the NHS five-year forward view; 2017. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf

- Reeves S. Ideas for the development of the interprofessional education and practice field: an update. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(4):405–407.

- Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick JD. Evaluation training programs: the four levels. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler; 2006.

- May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535–554.

- Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med. 2010;8:63.

- Jones F, Gage H, Drummond A, et al. Feasibility study of an integrated stroke self-management programme: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e008900.

- Mäkelä P, Gawned S, Jones F. Starting early: integration of self-management support into an acute stroke service. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3(1).

- Mäkelä P, Jones F, de Sousa de Abreu MI, et al. Supporting self‐management after traumatic brain injury: codesign and evaluation of a new intervention across a trauma pathway. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):632–642.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Worth publishers; 1997. ISBN: 10: 0716728508

- Miech EJ, Rattray NA, Flanagan ME, et al. Inside help: an integrative review of champions in healthcare-related implementation. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6.

- Duprez V, Vandecasteele T, Verhaeghe S, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to enhance self-management support competencies in the nursing profession: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(8):1807–1824.

- Finch TL, Girling M, May CR, et al. Nomad: implementation measure based on normalization process theory [measurement instrument]; 2015. Available from: http://www.normalizationprocess.org

- Adler P, Adler P. Membership roles in field research. Newbury Park: Sage; 1987.

- Strauss A, Corbin JM. 1990. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage.

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, MacFarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organisations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629.

- Légaré F, Thompson-Leduc P. Twelve myths about shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(3):281–286.

- Norris M, Kilbride C. From dictatorship to a reluctant democracy: stroke therapists talking about self-management. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(1):32–38.

- Makela P. Contaminating data with theory to reimagine support for ‘self-management’. Sociol Rev. 2021.

- Mudge S, Kayes N, McPherson K. Who is in control? Clinicians’ view on their role in self-management approaches: a qualitative metasynthesis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e007413.

- Moyo M, Goodyear-Smith FA, Weller J, et al. Healthcare practitioners’ personal and professional values. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21(2):257–286.

- Cornwell & Fitzsimmons. Behind closed doors. London (UK): Point of Care Foundation; 2017.