Abstract

Purpose

To examine patients’ perception of performance and satisfaction with the activities in their set goals before and after very early supported discharge (VESD) with continued rehabilitation.

Materials and methods

A descriptive cohort study with data extracted from a randomized controlled trial. Sixty-nine patient allocated to the intervention group were eligible. Before discharge, the patients were asked to set rehabilitation goals, and they were asked to rate the performance and satisfaction of their set goals. At discharge from the rehabilitation, the patients were asked to re-evaluate their experience and satisfaction with the goal performance.

Results

One hundred and forty goals were registered. At 81.5% of the set goals, the patients estimated that they performed the task better at discharge than at enrolment and at 86.5% of the set goals the patients were more satisfied with the performance at discharge than at enrolment.

Conclusions

Patients with mild to moderate stroke, undergoing a VESD after stroke, reported high performance level for their set goals and were satisfied with their performance execution. Further research is needed to investigate whether the goal should be set preferably at home or at hospital before discharge.

Many of the patients can formulate achievable goals with their rehabilitation after stroke.

Patients ongoing rehabilitation after stroke are satisfied with their performance of the set goals.

As part of patient-centered care, stroke patients should be given the opportunity to formulate their own goals with their rehabilitation.

Short hospital times and fast planning of goal-meetings, seems to influence patient goal setting in early discharge rehabilitation.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Stroke is one of the leading causes of permanent disability worldwide [Citation1]. Stroke has consequences not only for the person, but also for close loved ones. A core component of the rehabilitation process after a stroke is the identification and setting of rehabilitation goals [Citation2,Citation3]. By involving the care taker, attention is taken away from the traditional, narrow approach of medical, disease-driven concepts, to a wider problem-based perspective where the involvement of the patient becomes explicit and fundamental [Citation4]. This means that rehabilitation need to take not only the impairments into consideration but also the social context of the patient.

Goal setting is often a process where the rehabilitation team together with the patient, and sometimes family members, agree on goals to collaborate on during the rehabilitation period. Over the past two decades, there has been a shift in health-care policy from a care where the patient is a passive recipient to a care where you have a patient-centered approach, where the patient is active in the planning of their care and rehabilitation. Care recipients have found that by being involved in identifying goals for their rehabilitation, they became more aware of the treatment time and think more about what could be achieved during the rehabilitation period [Citation5], and it is also suggested that the involvement will have a positive impact on patients’ motivation to reach the set goals [Citation6]. It has been established that in order to achieve good results with the rehabilitation, it is important that the goals are relevant and meaningful for the patient [Citation7]. There are tools or strategies that can be used to help the patient identify, formulate, and prioritize their own goals, but it is important that such tools are integrated to the clinical reasoning [Citation8,Citation9]. It is important that the team is sensitive to that different patients prefer different approaches in their goal setting, some prefers to be passive and let the team set the goals while others prefer to be more active in their goal s etting [Citation10,Citation11].

Early supported discharge (ESD) services are usually provided by a multidisciplinary team consisting of physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses, and doctors. With the help of this team, the patient is given an opportunity to be discharged home early and to receive rehabilitation in the familiar environment of their own home. Patients satisfaction with being a part of the goal setting both in inpatient and outpatient care has been studied, but patient experience in performing the activities in their goals and how satisfied they are with its execution have not been explored. Since 2012, EDS has been a service offered at the stroke unit at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden. As part of the ESD service, a patient-centered goal-setting meeting is held before discharge.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) is a classification of health and health-related domains. It focuses on human functioning and can be used to indicate functioning and disability in three different domains: body structure, activities, and participation [Citation12]. The ICF framework provides a theoretical basis for developing goals for rehabilitation that are centered around the patient and his/her lifestyle, and is recommended to be incorporated in goal setting and treatment planning after stroke [Citation13].

The aim of this study was to examine patients’ perception of their performance of the activities in their set goals and their satisfaction with their performance before and after very early supported discharge (VESD) with continued rehabilitation at home.

Materials and methods

Study design and samples

This is a descriptive cohort study in which data were extracted from a randomized controlled trial, Gothenburg Very Early Supported Discharge (GOTVED) [Citation14] clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01622205. The GOTVED study compared patients who received VESD with continued rehabilitation at home after stroke with a control group who had been discharged according to the department’s usual routines after stroke. Patients admitted to the stroke unit at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg were consecutively screened between September 2011 and April 2016. The GOTVED study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg (registration number: 426-05 and 042-11). The 69 patients in the intervention group were eligible for this part of the project.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The GOTVED study had the following inclusion criteria: age >18 years, a diagnosis of stroke according to World Health Organization criteria [Citation15], a National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score from 0 to 16 on day 2 [Citation16,Citation17], a Barthel Index (BI) [Citation18] of 50 or more on day 2 [Citation19], and a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [Citation20] index of 26 points or less if BI = 100. Patients with a life expectancy of <1 year (e.g., with severe malignancy) or who could neither speak nor communicate in Swedish prior to stroke were excluded. For this study, the patient had to have formulated at least one goal for rehabilitation, for which they estimated their performance and satisfaction.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure in this study was a modified version of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Citation21]. The COPM is a method used to identify and prioritize the problems encountered by patients when performing an activity. It is intended to be used at the beginning of a contact to set goals and is repeated after an appropriate time to determine the change and results. The original COPM is used as a semi-structured interview, but in this study, we have only used the form for estimating the performance of their set goals and their satisfaction with their performance. A change in score of two-points or more has shown be a clinically meaningful change in the Swedish version of COPM [Citation22]. ADL function was assessed by the BI, which ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a higher level of ADL independence [Citation18]. Cognitive function was assessed using the MoCA [Citation20], with a score of ≥26 indicating normal cognitive functioning [Citation23]. Stroke-related neurological deficits were assessed with the NIHSS [Citation16]. The Goal Attainment Scale (GAS) was used to assess if the patient had achieved his or her rehabilitation goals set with the team [Citation24].

Goal settings

Before being discharged and beginning the rehabilitation with the VESD team, the patient attended a goal-setting meeting together with the team members which consisted of a nurse, a physiotherapist, and an occupational therapist. At the meeting, the patient was asked to identify their rehabilitation goals. All goals were patient generated; however, if necessary, they could get some guidance from the team to come up with suitable goals. At the time of goal setting, participants were asked to identify three main goals. There was no order to the three selected goals. A modified variant of the COPM [Citation21] was used, in which the patient was asked to rate their current experience on a 0–10 scale of how they thought they performed the goal right now and then rate how satisfied they were with their execution. The rating options ranged from “can not perform it at all” or “not satisfied at all” (score 0) to “can perform it extremely well” or “is extremely satisfied” (score 10). A change based on a two-point or more is suggested as clinically meaningful change [Citation22]. Ward physicians who were not involved in the study decided when the patient was ready to be discharged. At discharge from the VESD team about 4 weeks later, the patients were asked to re-evaluate their experience and satisfaction with the performance of the set goals. Upon discharge from the VESD team, the VESD team also assessed if they thought the patient had met the set rehabilitation goals based on the GAS.

Goal categorization

To get a better overview of the set goals, they were categorized into different themes. The two authors first categorized separately and then a compilation was made where they agreed on the different categories. The patient’s goals were furthermore divided into the tree different categories according to ICF; body structure; activities; participation. The two authors independently categorized the goals into one of the three different categories by using the ICF browser and in the event of an inconsistency consensus, it was solved through discussion.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were analyzed and expressed as percentages, mean ± SD, or median and interquartile range (IQR). All patient goals were extracted and entered into a database along with patient-reported performance and satisfaction with performance of each goal at admission and discharge from the VESD team. Any differences between patients who completed goal-setting measures and those who did not were examined using the Chi-squared test and Mann–Whitney U-test, and t-test and χ2 test of independence for demographic characteristics (age, sex, side of stroke, NIHSS, BI, and MoCA scores). The level of significance was set at p≤ 0.05. The change in patients’ perception of performance and satisfaction was examined using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Results

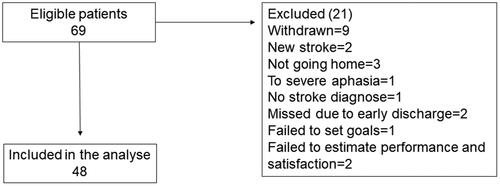

Of the 69 patients who were eligible for the study, 19 patients were lost prior to the goal setting meeting, and two patients were not able to estimate their goals (); thus, 48 patients were included in this study. Of these 48, two patients could only identify one goal, and one patient could only identify two goals. The median age was 76.5 years (IQR 68–81). Of the included patients, 42% were women, and 31% experienced a right-hemispheric stroke ().

Figure 1. Flowchart of the inclusion.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population, and comparisons with those excluded from the study.

A total of 140 goals were registered. Eight themes were identified (). The three most common goals were to improve mobility outdoors (which 83% of patients set as a goal), improving hand function (29%), and to be able to cook (27%) ().

Table 2. Patient goals categorized by themes.

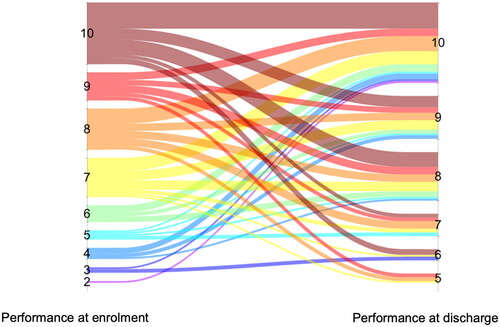

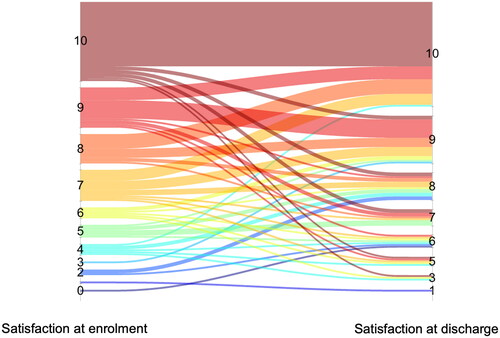

The majority of the goals (85%) were classified under the domain of activity limitation according to the ICF (). In 16 of the goals, the patients had difficulty in estimating how they thought they performed the set goals, and in 15 of the goals, the patients had difficulty in estimating how satisfied they were with their execution of the goal. Therefore, 124 and 125 goals, respectively, were included in those analyses. The median estimate of goal performance was 8 (IQR 6–10) at admission to the VESD team and 9 (IQR = 7–10) at discharge from rehabilitation, and there was a statistically significant difference in their estimation before and after the VESD rehabilitation period (p < 0.001) (). In 27% of cases, patients estimated the same score for performance at admission and discharge, and in 47% of cases they estimated a difference in score ≥2 points. At admission, the median estimate of how satisfied the patients were with their performance was 9 (IQR 7–10) and the same median estimate was made by the patients at discharge from the rehabilitation, 9 (IQR 8–10) (). There was a statistically significant difference in the patients’ experience of how satisfied they were with the execution of the goals before and after VESD rehabilitation (p < 0.001). In 42% of the set goals, patients estimated the same score for satisfaction at admission and discharge, and in 40% of the set goals they estimated a difference in score ≥2 points.

Figure 2. A Sankey diagram showing the changes in the rate of performance for each goal between enrolment and discharge from the VESD team.

Figure 3. A Sankey diagram showing the changes in the rate of satisfaction, for each goal, between enrolment and discharge from the VESD team.

Table 3. Patient-identified rehabilitation goals linked to the ICF framework using link rules for meaningful concepts.

The patients estimated that they performed the task worse at discharge than at enrolment for 18.5% of the set goals, and the patients estimated that they were less satisfied with their performance at discharge than at enrolment for 13.5% of the set goals. The majority of the goals (89.3%) were attained during the rehabilitation period according to the GAS. Seven percent of the goals were partially attained, and 2.9% of the goals were not attained according to the GAS.

Discussion

This study shows that the majority of patients felt that they performed their set goal well both at admission and at discharge from the rehabilitation. This agrees with some previous studies that have concluded that that patients would benefit from greater participation in the goal setting process [Citation25], and letting the patients formulate their goals makes them more motivated and more committed to the goal and leads to better performance [Citation26]. Others, however, have concluded the opposite that assigned specific and difficult goals lead to better performance than self-set or easy goals [Citation27]. A review from 2013 concluded that goal setting appeared to improve recovery, performance, and goal achievement, and positively influenced patients’ perceptions of self-care ability and engagement in rehabilitation. However, they also concluded that further research was needed to strengthen the evidence [Citation28].

Even if our study showed a significant difference in performance and satisfaction between admission and discharge from the VESD only 47% and 40% respectively reported a change of score two points or more, which has been reported as a clinically meaningful difference [Citation21,Citation22]. This can also be a sign that many patients set too easy goals. A limitation and bias in this study could be that the highly significant results was swayed by a few participants having high positive change on multiple goals. The study shows that individual goals have been estimated with a high difference, but none of the patients with multiple goals raised the significance level by estimating all their goals with a high difference.

In this study, the majority rated both their performance and satisfaction quite highly at enrolment and higher still at discharge. An explanation for this could be that the patients chose goals that they had already almost achieved. Perhaps the assignment of a more difficult goal would lead to a higher function post-stroke [Citation27]. A limitation in this study it that those who were excluded because they were not able to formulate goals for their rehabilitation were significantly older, scored lower on MoCA, and stayed significantly longer in the hospital compared to those in the included group. This may be due to impaired cognition, which may explain their difficulty in formulating goals. This is important to reflect on and to take with you at future goal setting meetings, otherwise there is a risk that this group will not have the same opportunity to focus their rehabilitation on things that are important to them. Older patients with reduced cognition and who require longer hospitalization may need more support and time to be able to formulate goals for their rehabilitation.

A few patients had problems estimating how satisfied they were with the performance of their goal activity. One explanation for this could be that the meeting was held at the hospital before discharge home, and it was difficult to imagine how they could manage activities which they had not tried to perform after their stroke. With nearly 20% of the goals, the patient experienced deterioration in the performance of the set goal at discharge from rehabilitation. This may be because the goal setting was performed at the hospital before discharge. If a normal and well-known activity has not been practiced after stroke, it may be assumed that it may be performed just as well as before stroke. At discharge from the VESD team, the patients practice the activity and have more insight into their performance. The same applies to the satisfaction with their performance. In nearly one-sixth of the set goals, the patients were less satisfied with their performance at discharge compared to that at enrolment by the VESD team. This may be because the expectation that the activities could be performed as well as before the stroke was not met when they returned home and gained more insights into their disability.

Most of the goals were activity-based. This may be because the patients included in this study had mild stroke with a median NIHSS score of 1. For these patients, goals linked to impaired function were probably not as relevant as those linked to the daily activities that they want to manage. Although a goal is activity-based, it may still be the case that parts of the rehabilitation for the set goal may be function-based.

A strength of this study is that the goal setting had a patient-centered approach, which is required of staff at Sahlgrenska Hospital to work according to and which many authors state should be focused on during rehabilitation [Citation10,Citation25,Citation29].

As mentioned above, a goal-setting meeting was held in the hospital. This can be a limitation because it can be difficult for the patient to imagine how to manage daily activities that they used to perform but had not tried to perform after their stroke. An alternative would be to hold the meeting a few days after the patient has been discharged home.

None of the stroke team members had to our knowledge any education in how to help the patient set meaningful and sufficiently challenging goals, or how to facilitate insecure patients or patients with impaired cognition to set goals with their rehabilitation. This is a weakness that can lead to that the rehabilitation is concentrated on something that the team thinks is important instead of something that is important for the patient to train on. This leads to rehabilitation that is not person-centered.

With training in goal setting and facilitating of goals perhaps the patients that had difficulties with setting goals would have managing and those setting easy a goal that they quickly achieved would have had set more difficult goals, which could result in an even better function after the rehabilitation period.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express gratitude to the VESD team at the stroke unit at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, who were committed in carrying out the goal-setting meetings.

Trial registration: VGFOUGSB-669501.

Clinical trials registry: The Gothenburg Very Early Supported Discharge trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01622205.

Disclosure statement

No conflicts of interest have been declared by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Feigin VL, Norrving B, Mensah GA. Global burden of stroke. Circ Res. 2017;120(3):439–448.

- Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):291–295.

- Levack WM, Dean SG, Siegert RJ, et al. Purposes and mechanisms of goal planning in rehabilitation: the need for a critical distinction. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(12):741–749.

- Lawler J, Dowswell G, Hearn J, et al. Recovering from stroke: a qualitative investigation of the role of goal setting in late stroke recovery. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30(2):401–409.

- Holliday RC, Ballinger C, Playford ED. Goal setting in neurological rehabilitation: patients’ perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(5):389–394.

- Rose A, Rosewilliam S, Soundy A. Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):65–75.

- Randall KE, McEwen IR. Writing patient-centered functional goals. Phys Ther. 2000;80(12):1197–1203.

- Stevens A, Köke A, van der Weijden T, et al. Ready for goal setting? Process evaluation of a patient-specific goal-setting method in physiotherapy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):618.

- Stevens A, Moser A, Köke A, et al. The use and perceived usefulness of a patient-specific measurement instrument in physiotherapy goal setting. A qualitative study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;27:23–31.

- Lloyd A, Roberts AR, Freeman JA. Finding a balance’ in involving patients in goal setting early after stroke: a physiotherapy perspective. Physiother Res Int. 2014;19(3):147–157.

- Thomson D. An ethnographic study of physiotherapists’ perceptions of their interactions with patients on a chronic pain unit. Physiother Theory Pract. 2008;24(6):408–422.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Miller EL, Murray L, Richards L, et al. Comprehensive overview of nursing and interdisciplinary rehabilitation care of the stroke patient: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2010;41(10):2402–2448.

- Rafsten L, Danielsson A, Nordin A, et al. Gothenburg Very Early Supported Discharge study (GOTVED): a randomised controlled trial investigating anxiety and overall disability in the first year after stroke. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):277.

- Stroke—1989. Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Report of the WHO Task Force on Stroke and Other Cerebrovascular Disorders. Stroke. 1989;20(10):1407–1431.

- Goldstein LB, Bertels C, Davis JN. Interrater reliability of the NIH Stroke Scale. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(6):660–662.

- Brott T, Adams HP Jr., Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20(7):864–870.

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65.

- Kay R, Wong KS, Perez G, et al. Dichotomizing stroke outcomes based on self-reported dependency. Neurology. 1997;49(6):1694–1696.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699.

- Law M, Baptiste S, McColl M, et al. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 1990;57(2):82–87.

- Wressle E, Samuelsson K, Henriksson C. Responsiveness of the Swedish version of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Scand J Occup Ther. 1999;6(2):84–89.

- Lees R, Selvarajah J, Fenton C, et al. Test accuracy of cognitive screening tests for diagnosis of dementia and multidomain cognitive impairment in stroke. Stroke. 2014;45(10):3008–3018.

- Kiresuk TJ, Sherman RE. Goal attainment scaling: a general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Ment Health J. 1968;4(6):443–453.

- Holliday RC, Cano S, Freeman JA, et al. Should patients participate in clinical decision making? An optimised balance block design controlled study of goal setting in a rehabilitation unit. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(6):576–580.

- Seijts GH, Latham GP. The construct of goal commitment: measurement and relationships with task performance. Problems and solutions in human assessment. Springer; New York 2000. p. 315–332.

- Gauggel S, Hoop M, Werner K. Assigned versus self-set goals and their impact on the performance of brain-damaged patients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24(8):1070–1080.

- Sugavanam T, Mead G, Bulley C, et al. The effects and experiences of goal setting in stroke rehabilitation – a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(3):177–190.

- Playford ED, Dawson L, Limbert V, et al. Goal-setting in rehabilitation: report of a workshop to explore professionals’ perceptions of goal-setting. Clin Rehabil. 2000;14(5):491–496.