Abstract

Purpose

Quality disability support is fundamental to the lives of many adults with acquired neurological disability. However, little is known about the factors that influence the quality of paid support. This study is part of a larger project to develop a holistic understanding of quality support, grounded in the experience of people with acquired neurological disability, close others, and disability support workers. The current study focuses on the support worker perspective.

Methods

Following constructivist grounded theory methodology, interviews were conducted with 12 support workers. Grounded theory analysis was followed to develop themes and subthemes and build a model of quality support.

Results

Five key themes, with fifteen subthemes emerged to depict factors influencing the quality of support. The five themes are: being the right person for the role, delivering quality support in practice, working well together, maintaining and improving quality support, and considering the broader context. Findings emphasise the importance of the support worker recognising the person as an individual and respecting their autonomy.

Conclusions

Critical to quality support is centring the needs and preferences of people with disability, improving support worker working conditions and supporting people with disability and support workers to build effective, balanced working relationships.

Delivering quality support in practice relies upon the support worker recognising, centring, and respecting the autonomy of the person with disability.

To deliver quality support, support workers need to feel valued, be committed to the role and actively work to maintain and improve the quality of support provision.

Quality support provision is facilitated by the support worker and the person with disability effectively balancing boundaries and friendship, and in turn building a quality working relationship.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Quality support provision is fundamental to adults with acquired neurological disability (i.e., acquired brain injury, stroke, spinal cord injury and neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis) who experience a range of complex needs. The onset of an acquired disability can be sudden and traumatic resulting in a very different experience to adults with a congenital intellectual disability whose experiences reflect lifelong functional limitations [Citation1]. Disability support workers are the primary workforce critical to ensuring people with acquired neurological disability can participate fully and independently in society, as is their right in line with United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [Citation2]. The support worker role encompasses multiple responsibilities from support with daily living to support with finances, employment and housing [Citation3–5], across various settings (i.e., home, community, day centres, shared supported accommodation and residential aged care) [Citation4–7]. This research focuses on what constitutes an excellent support worker and what other factors influence the quality of support provided to adults with acquired neurological disability.

Disability support provision has undergone fundamental reform in the past decade, with an international shift away from aggregate funding to individualised funding and a focus on person-centred support [Citation8,Citation9]. In Australia, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was introduced in 2013 to provide individualised funding packages to promote the provision of quality supports and maximise the control people have in choosing and following their goals [Citation10,Citation11]. Promisingly, this shift provides people the opportunity to choose and manage their supports and allows support workers to be more flexible in support provision, both of which have been shown to facilitate quality support [Citation12–19]. However, with the number of NDIS participants expected to reach 500,000 by 2024 [Citation20], the disability workforce needs to grow by 30 per cent and improve in quality and efficiency [Citation20]. Even though the support industry is one of Australia’s fastest growing sectors [Citation20,Citation21], concerns remain around attracting new people to the workforce given the growth still required and the large number of unfilled vacancies [Citation20,Citation22]. Concerningly, support work is perceived to have low job prestige, low pay, and limited opportunities for career progression [Citation20,Citation23]. Providers report that recruitment difficulties are due to a lack of appropriately qualified and willing candidates [Citation22]. These issues are compounded for culturally and linguistically diverse workers, workers in regional and remote communities or workers to provide support for adults with complex needs [Citation20,Citation24–26].

Retaining existing quality workers is also seen as problematic. Workforce growth is primarily evident in the casual workforce, with trends towards permanent positions decreasing [Citation21,Citation22,Citation27]. However, the wave of casualisation has seen the introduction of new online matching platforms (i.e., HireUp and Mable) that have disrupted the support industry for people living in the community, giving them the opportunity to directly choose workers for the amount and type of support they need. Nevertheless, whilst casual work suits some workers, for others the lack of certainty means they would prefer permanent positions [Citation21]. Limited resources for training and professional development [Citation20,Citation28–30], coupled with stress and burnout [Citation31,Citation32], further exacerbate workforce turnover concerns. Service quality suffers as experienced workers leave and inexperienced workers enter the workforce [Citation21,Citation27]. In response, increasing government and industry efforts have been made to deliver improvements to the workforce [Citation20,Citation33,Citation34]. Recently, the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission produced a Workforce Capability Framework describing core capabilities the Australian government expects of all NDIS-funded workers [Citation34]. The framework encompasses capabilities around relationship building, providing individualised support and engaging in reflective practice. However, a lack of research to inform service development and ensure these capabilities are grounded in lived experience and will improve the quality of support in practice persists [Citation27].

Considering available evidence, provision of quality support is a complex process influenced by multiple interrelated factors [Citation12]. People with acquired neurological disability and support workers point to important soft skills (e.g., empathy), relationship and communication skills, and practical skills (e.g., manual handling and behaviour support management) an excellent support worker should have [Citation12,Citation14,Citation16,Citation18,Citation30,Citation35,Citation36]. In 2019, Moskos and Isherwood [Citation30] described additional skills and competencies required to provide quality support within the context of individualised funding schemes (e.g., client-focused and decision-making skills). Further, research indicates that the support worker’s prior knowledge, training and experience impact support provision [Citation12,Citation14,Citation37,Citation38], yet the NDIS pricing structures are not considered to provide sufficient resources for training and development opportunities [Citation7,Citation29,Citation30]. Increasingly, evidence highlights the importance of the relationship between the person with disability and the support worker in facilitating quality support [Citation6,Citation12–14,Citation19,Citation35,Citation39–43] and protecting against mistreatment [Citation39]. To build a quality relationship, people with disability in our earlier study, and previous research, considered compatibility, respect, and communication critical alongside balancing boundaries and friendship [Citation12,Citation19]. Correspondingly, research has shown that people need time to develop familiarity and trust with their support workers, thus continuity of support is important [Citation13], as is support from the provider organisation [Citation44].

Although systemic, organisational, and dyadic factors that influence the quality of support have been identified in the literature, limited research has directly focused on the perspective of support workers. Considering the evidence points to support as a relational process situated within an institutional context, it is fundamental to understand the lived experience of workers providing support to adults with acquired neurological disability. This study is situated within a series of studies aiming to develop a holistic understanding of quality support, grounded in the lived experience of people with acquired neurological disability, close others (i.e., family, friends, partners) and support workers. It is hoped the combined findings from the three studies will inform subsequent policy and practice recommendations to improve the quality of disability support. Following completion of the study focused on adults with acquired neurological disability [Citation19], this study aims to obtain the perspective of support workers on factors that influence the quality of support.

Method

Study design

This research was a qualitative constructivist grounded theory study utilising in-depth interviews [Citation45,Citation46]. Constructivist grounded theory was well suited to the research as it provides the opportunity to capture the contextualised lived experience of a social process (i.e., support provision) about which little is known. This methodology also facilitates an inductive approach, allowing concurrent data collection and analysis. In turn, it enables rich data collection through flexible interviewing that incorporates questions in line with emerging data. Additionally, this methodology acknowledges the interaction between the researcher and the participant, thus subsequent theory generation is considered a construction between the participants and researcher.

Participant recruitment

Institutional approval was obtained from the University Human Ethics Committee (HEC20253). Participants were recruited via university networks, a non-for-profit advocacy organisation and a support provider. Advertisements were incorporated into the organisations’ newsletters or social media platforms. An administrative staff member from each organisation approached potential participants. Participants provided written informed consent. Purposive sampling was used to recruit support workers who had experience working with adults with acquired neurological disability, with attention to variation regarding age, gender, employment arrangement and experience. As the first eight participants were female, four male support workers were purposively sampled. Participants received a gift voucher following participation.

Participants

Twelve disability support workers (8 female, 4 male; mean age 33, range 20 − 52) living in Australia were recruited to the study (see ). Most worked with adults with a range of disability types and in a range of settings (e.g., home, community, supported accommodation, day centres). Support workers were asked to only discuss experiences relating to adults with acquired neurological disability. Years of experience as a support worker ranged from 6 months to 10 years. Employment arrangements included via an online platform (7), and via a service provider (9), with four participants employed via multiple arrangements.

Table 1. Participants characteristics.

Procedure

Participants were provided with written information and the opportunity to discuss the study with the first author before providing consent. Interviews were conducted between November 2020 and February 2022. Interview length ranged from 30 to 90 min. Due to COVID-19 related restrictions, interviews were conducted via Zoom videoconferencing (10) or telephone (2). Additional measures were implemented to reduce the risk of losing the richness of the interviews and ensure participants were comfortable (e.g., rapport building efforts and participant-led interview) [Citation47,Citation48]. In turn, the data collection approach did not impact rapport building or subsequent data. The semi-structured interview schedule was developed by the authors in consultation with a person with disability receiving paid support, incorporating open-ended questions to generate rich life experiences of providing paid support, what is required to be an excellent support worker and other factors that influence support quality (see Appendix 1 for interview schedule). The first author conducted the interviews, taking a flexible approach (i.e., following the participant’s leads of enquiry and using probes to extract deeper insights). Probes were also used to explore lines of enquiry raised by earlier participants. To aid later analysis, the first author engaged in reflective journaling following each interview and documented notable participant behaviours and their surroundings. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Analysis followed an iterative process utilising Charmaz’s [Citation45] grounded theory three-stage coding method: initial, focused and axial-coding. Nvivo software [Citation49] was used to organise the interview data, codes, and memos. The first and second author coded the first five interview transcripts to establish consistency. The first author coded all transcripts. Constant comparison techniques were employed throughout analysis, whereby data within and between codes were compared to facilitate conceptual abstraction. Memos were used to capture initial thoughts about the emerging analysis, challenge researcher biases and ensure themes were grounded in the original data. In the final analysis stages, diagramming was used to facilitate theme development and explore interconnections between themes. The authors discussed codes and emerging themes until consensus was reached and theme saturation was apparent, at which point, no further sampling was necessary [Citation50,Citation51].

Quality

Strategies were employed to address Charmaz’s [Citation45] questions regarding credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness. Efforts to build rapport with participants prior to the interview were made to help participants feel comfortable to share their authentic experiences. The first author took field notes during the interviews, engaged in reflective journaling after each interview and used memo writing to comprehensively document the data collection and analysis process. Correspondingly, a data verification strategy, whereby the first author created short summaries of each participant’s contributions to send back to them, was employed to ensure the participant’s insights were captured accurately and to provide the opportunity to amend their contributions. None of the participants modified the summaries, but three participants provided more depth to their contributions. The first author continually engaged in reflective processes (e.g., acknowledged personal biases and assumptions when interpreting the data) and discussed analysis regularly with the other authors during supervision sessions. When discrepancies between the authors occurred, transcripts, fieldnotes and memos were reviewed to aid ongoing discussions until consensus was reached. To verify the resonance and usefulness of the research, the findings have been presented and discussed at local, national, and international forums. Discussions endorsed the findings and provided contextualised individual perspectives but did not alter the presented findings. Illustrative interview quotes are presented throughout the results to demonstrate the analysis is grounded in participants’ experiences. The comments and quotes included in the text of the results are short excerpts that reflect the points made by participants that came together to encompass their experience-based narrative of supporting people with acquired neurological disability. Further unabridged example quotes in line with the themes and subthemes that emerged from the analysis are provide in . Pseudonyms replace participant names to protect their identity. The study was conducted and reported in line with the criteria set by the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research [Citation52].

Table 2. Themes, subthemes and example participant quotes.

Results

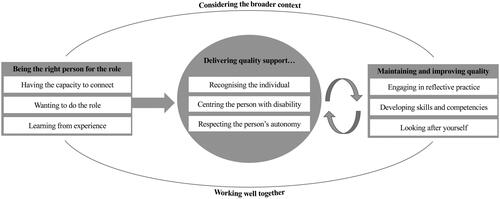

Five key themes were identified, which included (a) being the right person for the role; (b) delivering quality support in practice; (c) working well together; (d) maintaining and improving quality support; and (e) considering the broader context. The factors influencing the quality of support emerged as a dynamic model (see ) with being the right person for the role as the starting point. With the appropriate attributes and motivations, support workers are better placed to deliver quality support in practice. Delivery of quality support is facilitated by the person with disability and the support worker being the right fit, building trust and finding the balance between boundaries and friendship, and in turn working well together. Quality support is maintained and improved by support workers actively engaging in reflective practice, developing their skills, and looking after themselves. Maintaining and improving quality support is facilitated by the delivery of quality support and vice versa. Finally, participants acknowledged how the external, contextual factors (i.e., societal attitudes and institutional structures) impact the support workforce, the delivery of support in practice, as well as support workers’ opportunities to maintain and improve the quality of support.

Figure 1. Model of quality disability support from perspective of disability support workers.

Being the right person for the role

Having the capacity to connect

Participants highlighted the importance of support workers having the capacity to connect with people. For some participants, this meant being a “people person” (Frankie), who enjoys and is open to building connections. Others highlighted the importance of being “approachable, good humoured… able to socialise and talk” (Frankie), “build[ing] rapport” (Pat) and “having a bit of humility” (Sam). Participants also referred to good support workers being “decent” (Joyce), “nice” (Rory) or “kind” (Courtney) people, who like “working with people… within the community” (Courtney). One participant, Courtney, directly referred to the value of having the “capacity to emotionally connect with someone” and a “degree of emotional intelligence”. Participants felt support workers who have empathy are more able to connect with and see the person’s perspective, and in turn provide personalised support.

Wanting to do the role

Participants recognised the importance of support workers coming to the role with the right motivations and genuinely wanting to do the role. There was a strong notion that “there’s so many people in this industry that really shouldn’t be and they’re only in it for the money” (Kerry), and “with that comes failed support” (Joyce). Participants discussed support workers who “jump into this industry because it can be easy money in their eyes” (Joyce) and felt they often “just do the bare minimum” (Kerry). Moreover, the consensus was that workers who are “doing it for the sake of money… don’t really care about the client’s quality of life” (Pat) and are not committed to the role. Participants felt support workers should show they are “interested in helping” (Jordan) and in turn, people with disability will “get a better experience” (Rory) and “trust who is around” (Jordan). Participants also acknowledged that service providers need to have the right motivations to foster quality support.

As well as being motivated to do the role, participants felt that support workers need to be comfortable with the specific tasks required for the individual. Jordan highlighted that sometimes new workers “just get scared the first day and it’s too much” because they do not know what to expect. Correspondingly, Frankie suggested that support workers should “get a little bit of supervised time in the industry where [they] can say, 'yeah, this is for me' or 'it’s not for me'”. Consistently, multiple participants pointed out the importance of “understanding your own boundaries” and being “honest with what you are willing and not willing to do” (Kerry). Otherwise, it can become “a snowball effect of not liking the situation, not being comfortable with the situation and feeling like you’re both trapped” (Kerry).

Participants considered it important to be “motivated to help the client” (Morgan) and have “passion for what [they] do” (Jamie). When asked what the most important factor influencing the quality of support was, Rory said “the drive to help, I guess… you just want to help people”. Accordingly, participants thought with the right motivations, support workers are more inclined to “go above and beyond the job description” (Rory), rather than just “go through the motions” (Courtney). Participants felt workers should “think outside the box” (Sam) to meet people’s needs and “ensure everything is done correctly” (Rory).

Learning from experience

Participants agreed that training “on the job” (Joyce; Jamie), via experience, was the most effective way to prepare support workers to provide quality support. Thus, most participants valued prior experience, be that life experience or industry experience, over formal qualifications. Life experience (i.e., supporting family, or lived experience of disability) was cited in reference to developing empathy, communication skills and “general life skills” (Sam) (i.e., domestic skills – cooking and cleaning, personal care and “common sense” – Sam).

Participants identified other skills and competencies support workers primarily learned from hands-on experience or working with experienced support workers. The most cited of which was to understand the disability and the skills required to respond to the needs of people with that disability. For example, to support people with acquired brain injuries, participants considered it important to “know how to prompt people” (Morgan), as well as “strategies to de-escalate situations” (Pat, referring to behaviours of concern). Participants also commented on the importance of being physically fit for the manual work required. Other competencies included good time management, attention to detail and problem-solving abilities. Consistent with the notion of learning from other support workers, when starting with a new person, most support workers attended multiple “shadow shifts” (Jordan; Stacey; Pat) with an experienced support worker demonstrating how to support the person.

Delivering quality support in practice

The following factors can be considered the “how to” of delivering quality support in practice. Facilitating the fulfilment of these factors, participants emphasised the importance of support workers maintaining honest and open communication and taking a flexible approach to support provision.

Recognising the person as an individual

Participants stressed the importance of recognising the person as an individual with their own needs and preferences, rather than seeing them as a “number” (Stacey), “a cog in a large machine” (Danny) or a disability type. They emphasised that support workers should not make assumptions based on disability type or their prior support work experience. Thus, workers should spend time “get[ting] to know the person… [and] approach [each person] in a different way” (Stacey). Participants also acknowledged that in recognising the person as an individual, support workers are more inclined to “treat [the person] as [they] would like to be treated” (Joyce).

To be prepared to provide individualised support, participants deemed it important to learn about the person before working with them. For some participants this looked like reading “a support plan which gives some ideas of what the role is with each client” (Danny). As support workers, participants wanted to know “what [the person’s] main disability is… the positive stuff, the challenging stuff” (Joyce), and encouraged asking other support workers or family members questions to learn beyond the written information.

Centring the person with disability

Participants highlighted the importance of centring the person with disability and being perceptive to their needs. In practice, this meant to “really focus on the client” (Pat) and have their “interests and well-being at the forefront” (Sam), because “it’s not about you, you’re not there for you” (Stacey). Participants stressed that support workers should strive to make the person happy and be “invested in their goals” (Morgan). Accordingly, keeping the person at the centre of support provision allows workers to “recognise [the person’s] potential” (Joyce) and in turn, engage in building their capacity, and “help them achieve what they want to achieve” (Stacey). Centring the individual was also about support workers “pay[ing] attention” (Jordan) to, engaging with and including the person in conversations and activities.

To centre the person and their needs, participants valued the capacity to “put [them]selves in the client’s shoes” (Jordan). This involved having empathy and being able to consider the holistic impact of their attitudes and actions on the person’s life. Moreover, Jordan highlighted that support workers need to “think ahead” to foresee how a situation may impact the individual, and “be proactive” in responding to those needs.

Respecting the person’s autonomy

Participants stressed respecting the person’s autonomy. Fundamentally, support workers should respect the person’s choices and allow them to “drive the sessions” (Pat). Participants felt support workers should “put [their] personal agenda aside” (Morgan) and follow the person’s lead. Support workers should see the person as the “expert of the disability” and “learn from each different human” (Joyce) about how to best support them. Participants felt good communication helps workers to uphold the person’s autonomy. Support workers should be asking the person how they want things done and ensure they listen and make decisions with the person, rather than for them. Participants acknowledged that it can be difficult with people who are non-verbal. However, it is critical to “learn how your person communicates” (Joyce) and “try not to make assumptions or do things on behalf of people” (Courtney). Participants also discussed the support worker’s role in risk enablement, emphasising that they should support the person in activities they want to do and provide a safe way to do those things without being paternalistic and acting as a barrier.

Working well together

Being the right fit

Participants felt being the right fit facilitated a good working relationship. Participants discussed being the right fit in terms of having compatible personalities, getting along well, and sharing similar interests. Similar interests were of particular importance when supporting people with community access, because if the support worker is also interested in the activity “it gives [the person] a better experience as opposed to [going with] someone who doesn’t know anything about it or is not as interested” (Rory). Participants commented that being compatible in terms of demographics (i.e., similar age, gender) was preferable for some people in the community because “we blend in” (Joyce) and “you can’t tell who the support worker is” (Frankie). Overwhelmingly, participants described being the right fit as reciprocal, in terms of having “chemistry,” a “connection” (Rory) and “gelling” (Sam) or “clicking” (Kerry) with one another. However, as Kerry highlighted, it can “take a lot to click” with someone. Thus, having the opportunity to choose one another, and being able to meet helps both parties decide if it’s the right fit.

Building trust

“Trust and respect” (Morgan) between the person and their support worker was emphasised as critical to quality support. The key indicator of a trusting relationship was the person and support worker feeling comfortable to be themselves and communicate honestly with one another. Participants acknowledged that there is a “period of building trust” and “adapting to a new person” (Pat). Thus, participants considered continuity of support, alongside being the right fit as facilitators of quality relationships. In turn, it was stressed that service providers should not “flip, change workers constantly” (Joyce) and workers should be committed to their roles.

An indicator of a trusting relationship highlighted by participants was the person feeling safe to depend on support workers and knowing they are prioritising their preferences. Participants felt that within a secure, trusting relationship, the support worker “know[s] when to push and when not to” (Morgan), in turn facilitating capacity building. Additionally, participants thought that knowing the person well allows the support worker to foresee and handle behaviours of concern and trusting the support worker helps the person with disability handle “situations where they’re vulnerable” (Morgan).

Finding the balance

For some participants, quality support relationships were reminiscent of friendship, whereas others highlighted the importance of maintaining boundaries to ensure both parties remain comfortable. Participants acknowledged that finding the balance can be difficult because some people want support workers to “be their friend” (Kerry), especially those who “don’t have a lot of friends or their family doesn’t keep in touch, so you sometimes are the only person they do talk to that day” (Morgan). However, overwhelmingly participants recognised “professional boundaries” (Danny; Sam) as critical because if the relationship becomes “too friendly” (Kerry), it can compromise the person’s comfort in “holding [the support worker] accountable” (Morgan). Similarly, it can result in the support worker feeling obliged to provide support outside of their working remit, or support workers not taking the job seriously. Examples of boundaries included not socialising outside of work hours and being careful sharing personal information.

Participants believed that balancing friendship and boundaries in line with the person’s needs and preferences can result in a better support experience for the person with disability, and the support worker. Participants acknowledged the importance of “having a good time” (Joyce) together and the person “feeling like [they] can be [them]self” (Kerry). The value of humour was also stressed by participants, as it can “change the narrative of a situation” (Sam) and help people feel comfortable in potentially uncomfortable situations.

Maintaining and improving the quality of support

Engaging in reflective practice

As support provision is individual, participants deemed it critical to regularly reflect on their work and “question, am I doing the best I can; am I doing it the best way, as the client’s requested?” (Danny). Engaging in reflective practice was considered important in terms of staying accountable as often the only “real performance management [is] that trust between yourself and the clients” (Jamie). Participants working for service providers sometimes felt their formal performance reviews were “about the organisation itself and us working for the organisation, not always about the clients we work with” (Danny). Whereas participants working via an online platform wanted more formal mechanisms to get feedback because “there isn’t a lot of that accountability, which would be good to have” (Jamie). Thus, participants felt it was important to “recognise your deficits” (Joyce), facilitate mechanisms for reviewing one’s own performance and engage in ongoing learning.

The key reflective practice mechanism participants referred to was simply “ask[ing] for feedback” (Jordan) from the people they’re supporting and using this guidance to inform practice. Participants endorsed always “being open to talking” and “receiving feedback” (Jordan), as ongoing, informal communication can be “more valuable” (Sam) than formal performance reviews for maintaining quality support. Participants acknowledged that support workers cannot always get direct verbal feedback from the person with disability. Thus, participants highlighted the importance of “looking at the client’s behaviours” (Pat) to gauge their feelings in response to the support provided. Participants also appreciated feedback and guidance from the wider support team (i.e., therapists or service provider staff), as well as discussions with colleagues to help them stay accountable and deliver best practice.

Developing skills and competencies

Participants considered it critical to be continually “open and willing to learn” (Jordan) and develop skills and competencies. Participants saw “every single shift [as] a learning opportunity” (Stacey) because “each human is going to provide you with a different challenge that you might not be prepared for” (Joyce). In addition to on-the-job learning, participants thought support workers should engage in ongoing formal training to develop competencies and avoid becoming “complacent if you’re repeatedly doing the same thing” (Danny). Most participants felt satisfied with the training they received on practical competencies e.g., “showering, toileting, manual handling, infection control” (Jordan). However, some participants felt there was a “lack of good training opportunities” and wanted “access to a broader range of training” (Danny), encompassing “mental health” (Danny), relationship management, “signs of potential abuse” (Courtney), “uphold[ing] someone’s privacy” (Courtney), as well as handling “behaviours of concern” (Courtney; Sam) and general “training around people” (Jamie).

Participants preferred face-to-face training over online modules, which could be “arduous” and “feel like a chore” (Courtney). There was an overwhelming view that training via online modules was “insufficient because you’re providing physical support to people… it’s like expecting them to go for their P plates by just reading how to drive a car” (Sam). Whereas face-to-face training gives workers the opportunity to “discuss with the trainer a range of concerns or ideas” (Danny), as well as to physically practice tasks and engage in scenario-based training.

Looking after yourself

Given the physical and emotional demands of the role, participants considered it important to look after yourself to remain able to deliver quality support. Participants highlighted valuable prerequisites, such as having “physical fitness,” “a healthy mindset” (Danny) and “resilience” (Frankie; Courtney). These attributes helped because working with people with acquired neurological disability often involves “emotionally taxing” (Courtney) circumstances. Participants acknowledged the importance of “monitoring yourself” and ensuring to “lean back and take some time… because you can’t deliver support if you are not ok” (Joyce). Correspondingly, participants set boundaries between work and home life and tried to avoid “taking things personally” (Kerry; Morgan) and “taking home stuff from the day” (Courtney). Additionally, participants engaged in self-care activities outside of work to protect themselves from burnout.

Considering the broader context

Feeling valued

Participants emphasised the importance of employers, be that the person with disability, their family, or service provider, valuing the support worker. It was suggested that independent support workers provide better quality support because they are more likely to be valued by their employer. In addition, participants suggested that “if you have management that’s more supportive of you then you don’t feel as restricted” (Courtney) and are therefore more likely to deliver support according to the person’s needs and preferences. Participants appreciated employers who “call you and check on you and see how you’re going… they really care about you” (Frankie). Some participants felt “underappreciated and unvalued” by the person’s family as they “fobbed [them] off, like [they]’re just a paid friend” (Joyce). Participants also felt the role was undervalued at a societal level, as it’s “viewed as not needing a lot of skills” (Frankie) and felt this could attract the wrong people to the industry. Moreover, multiple participants discussed the diverse and difficult nature of the role, and felt underappreciated when people made patronising remarks such as “that’s so easy, why can’t I do that?” (Rory).

Having a community of practice

Given the isolating nature of the role, participants wanted a community of practice to support them to deliver quality support. Primarily, participants valued having people in the sector to ask for guidance. This was relevant in terms of receiving information and feedback around particular people with disability from the wider support team (i.e., therapists and allied health professionals), and more generally learning from others in the sector. One participant, working via an online platform, was grateful to the organisation for setting up “a conference day where [support workers] all got to meet, so [they] finally got to meet people that [they] actually work with or are in [their] industry” (Frankie). Others were grateful to work for a service provider and have colleagues because “if [they] were having trouble or had a difficult situation… [they] could call somebody” (Stacey). Networking also helped participants to “be aware of what’s out there in terms of other jobs” and knowing other support workers means they can “help each other out with getting a little bit more work” (Frankie).

Working within institutional constraints

Participants expressed that working within institutional constraints of the broader system (i.e., NDIS) or service provider sometimes hindered support quality. Of particular focus was how the rules and regulations implemented by the NDIS and service providers conflicted with “upholding someone’s autonomy and independence” because there were “limitations on spontaneity” (Courtney). Participants spoke of organisational guidelines that restricted their relationships with people. Sam expressed that this prohibited them “provid[ing] the level of support that [they] know [they] can provide and the level of support that the person requires”. Participants also felt service providers sometimes made decisions without considering the impact on the person with disability e.g., changing workers frequently, or not considering how well the person matches their support worker. Another example was when service providers implemented rules stating that support workers cannot engage with people once they stop working with them. Although participants understood this boundary, they did not feel it was fair to ignore people if they saw them in public, as it would “make someone feel invisible… [and] cause some significant, long-lasting trauma” (Joyce). Correspondingly, participants discussed how the “mentality of the [service provider] management” and “the support from the top-down is really crucial” (Courtney). With supportive management, participants felt less constrained and more trusted to provide quality individualised support.

Lack of institutional structure

Although institutional conditions constrained workers in ways, participants also felt the lack of supportive institutional structure around the workforce could impede support provision. Jordan expressed that some workers directly employed by the person with disability or via online platforms “don’t have a boss… don’t have this kind of responsibility, they think they are free to do whatever they want and sometimes they just don’t turn up”. Similarly, participants were concerned that the lack of entry requirements for the role can attract workers who “think they can do a good job but in actual fact they can’t” (Rory). This was of particular concern in the context of employment via online platforms because “it seems very easy to set up as a support worker… like anyone can log in and create an account” (Jamie). Participants did note that the introduction of the NDIS led to an increase in qualification requirements from service providers, but they did not think the requirements led to better workers. In fact, participants felt inconsistencies in requirements caused confusion “because [people] think there are these huge expectations, like qualifications” (Joyce), resulting in potentially good support workers not entering the workforce.

Participants gave the sense that qualification requirements were not necessary, but a minimum education requirement may be helpful. Participants suggested a “baseline standard” (Sam) of training when you start “to make it fair on the clients you’re supporting for the first few times” (Jamie). Participants found “lack of standardisation” (Sam) around training across different employment set-ups to be concerning for the quality of support.

Participants also discussed the lack of career progression pathways for the support workforce. Jordan, for example, found it challenging with the “level of responsibility [they] have and the experience [they] have, [to] earn the same thing as these guys that just started yesterday”. Participants felt that with more experience, they were given more jobs to do but earned the same as the less experienced workers. However, Jordan did note that they prefer working privately, as they can “develop really good conditions for [their] job… and give them [their] price”. Whereas working for a service provider means the support worker is capped at their rates, which some participants felt were unfair. Unfair pay was considered to have “huge effect on the quality of the workforce” because “fantastic” (Danny) support workers leave the industry to find higher paying roles. Participants felt that when support workers are “getting paid appropriately, [they’re] going to be going a little bit extra” (Joyce) and deliver better quality support. Finally, participants commented on the casualisation of the workforce increasing workforce instability. Although participants enjoyed the flexibility of the role, they acknowledged the associated issues of uncertainty for support workers and people with disability.

Discussion

This constructivist grounded theory study aimed to capture the perspectives of support workers around factors that influence the quality of support. As this study sits within a series of three studies our research team are conducting, we hoped to identify relevant evidence from the support worker perspective to combine with the perspectives of people with disability [Citation19] and close others of people with disability (in prep) to inform subsequent practice recommendations for quality support. While some participants worked with people with other disability types, the findings are situated in their experiences with adults with acquired neurological disability. Of primary importance was the support worker’s approach and behaviour in the delivery of support (i.e., recognising the individual, centring the individual and respecting their autonomy). Thus, this study, alongside our previous research with people with disability [Citation19] and other research highlighting the importance of people having autonomy over their supports [Citation12,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17], reinforces the notion that the quality of support hinges on how aligned it is with the person’s needs and preferences. These principles echo NDIS objectives to respect the decisions and preferences of people with disability [Citation10], as well as the rights of people with disability to have choice and control around support provision [Citation2]. Promisingly, with the introduction of the NDIS, online support provider platforms centred around these values have been developed, providing avenues for people to lead their supports. However, more needs to be done to support people with disability to take charge of their supports and realise these principles in practice.

Corresponding with the concerns around attracting the right people to the workforce [Citation20,Citation22], participants rejected the notion that anyone can do the role and identified pre-requisites of a quality support worker. Echoing our previous research with people with disability [Citation19], participants emphasised the importance of workers coming to the role with the right motivations, as there are people in the industry for the wrong reasons. These findings imply the need for better education as to what support work entails, as well as targeted screening to identify candidates who genuinely want to do the role. Participants also considered prior experience, particularly life experience and on-the-job experiences, valuable pre-requisites of a skilled support worker. However, it is important to note that participants acknowledging the value of experience does not mean older or more experienced support workers are necessarily better than newer workers. As suggested in previous research [Citation19], experienced support workers can come with an attitude of knowing best and be less willing to listen. Considering these findings together with the importance of respecting the person’s autonomy, it appears that the support worker’s attitude and willingness to learn can effectively outweigh the value of prior experience.

In line with previous research [Citation6,Citation12–14,Citation17,Citation35,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43,Citation44], participants discussed the complexity of the support relationship and stressed the importance of finding the balance between professional boundaries and friendship. In the complex process of finding balance, support workers considered having the capacity to connect, being the right fit with the person and having time to build trust as facilitators of a quality support relationship. Crucially, the person with disability and the support worker need to feel comfortable to communicate openly and honestly. This authentic communication enables the realisation of the factors key to the delivery of support in practice (i.e., recognising and centring the individual, and respecting their autonomy). These findings have important implications for service providers who should aim to include the person with disability and support worker in the hiring and matching process. Their inclusion gives them the opportunity to choose one another and therefore improves their likelihood of being the right fit. Encouragingly, online matching platforms can prioritise compatibility and provide pathways to facilitate making informed decisions about working together.

Findings depicted provision of quality support as a dynamic process that support workers need to actively maintain and improve. Critically, support workers should regularly reflect on their practice to ensure they are delivering optimum support for each individual. This finding aligns with the NDIS Workforce Capability Framework competency, engaging in reflective practice, and demonstrates a need to build the capacity of people with disability to provide regular feedback and support workers to seek ongoing feedback. It also speaks further to the importance of a positive working relationship to foster a comfortable feedback loop between the support worker and person with disability. In line with previous research stressing the importance of support workers being willing to learn [Citation12], participants endorsed support workers continually developing their skills. It is noteworthy that the training gaps participants highlighted reflect the needs identified through the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability in Australia (i.e., safeguarding, behaviours of concern, mental health) [Citation53]. Thus, it would be useful to develop practical training resources on specific topics led by people with disability. In this way people with disability can specify the training they want their support workers to have. Person-led training will also help to platform people with disability as the support experts [Citation19], and better allow support workers to understand the perspective of the person they are supporting. Finally, to protect from stress and burnout and provide quality support in a sustainable manner, participants stressed the importance of looking after themselves. These findings, alongside previous research [Citation31,Citation32,Citation54], emphasise the need for support workers to be well supported and provided with resources around the risks and how to manage feeling overwhelmed.

Moving beyond the support dyad, the broader context within which support workers practise was highlighted as key in influencing the support quality. Supporting research findings from support workers working with people with dementia [Citation55], participants in the current study discussed the importance of feeling valued by their employer. Similarly, previous Canadian and British research has demonstrated that employees who feel valued are more committed and motivated to invest in the role [Citation56,Citation57]. Thus, service providers have a responsibility to provide good working conditions. However, people with disability are not trained to be employers but are thrust into the employer role as a by-product of wanting autonomy over their support arrangements. Consequently, this finding demonstrates a need for resources and support for people with disability directly employing workers. Support workers also felt undervalued at a societal level and believed this negatively impacted recruitment of the right people to the industry. These findings align with the perception of the Australian general population [Citation23] and further emphasise the importance of educating people on the value of support work. Moreover, lack of career progression pathways, alongside the isolating nature of the role was seen as problematic for both attracting and retaining quality support workers. Accordingly, support workers’ working conditions need to be improved in terms of developing pathways for professional development and building upon and increasing engagement with existing peak bodies and communities of practice for support workers. Additionally, in line with the expert consultant on our scoping review [Citation12], the current findings suggest mechanisms to hold support workers accountable for their work would improve the quality of support provision. Such mechanisms include setting clear expectations to workers and providing avenues for performance management and feedback provision.

Future research

As noted earlier, this study is one of three studies focused on quality disability support from three different perspectives: people with acquired neurological disability, support workers and close others. Once the studies are complete, we will analyse the perspectives together to build a holistic model grounded in the three perspectives and draw out recommendations at the dyadic, practice and policy levels. Following this, we plan to conduct a co-design project with people with acquired neurological disability to translate these findings into practical solutions aiming to improve the quality of support. Beyond this research project, these principles need to be tested with other disability groups, in different settings and across cultural groups. It would also be useful to obtain the perspective of service provider management and allied health professionals working with support workers, around their role in influencing the quality of support.

Implications for policy and practice

Combined with the perspective of people with acquired neurological disability [Citation19], these findings can inform policy and practice around quality support provision. The pre-requisites participants identified could inform guidance for people with disability and service providers recruiting support workers, as well as policy initiatives to screen NDIS workers beyond safety measures [Citation58]. One potential solution, raised by a participant in response to workers being sent to support people about whom they know little or nothing, is to have regulations around a minimal level of knowledge support workers should have about the person before working with them.

The findings could also inform resources for potential support workers deciding if the role is appropriate for them (e.g., questions to ask oneself, essential elements of the role). Combining quality practice findings from the lived experience of people with disability [Citation19] and support workers provides work-relevant insights to inform training resources about the nature of quality support, as well as resources to help people lead their own supports and communicate their expectations. Although, the current findings indicate support workers learn best by experience, it is important to consider the expense of shadow shifts which require paying multiple workers for one shift. Thus, we need innovative ways for people with disability to lead the training of support workers, without the burden of repeating themselves [Citation12,Citation13,Citation15,Citation19]. One such initiative could be the use of video technology to create participant-led videos [Citation59,Citation60], whereby people create a video to train their support workers on how they want to be supported. Further, these findings suggest service providers should aim to provide support workers with opportunities to engage with other staff, facilitate a comfortable space for workers to ask questions and learn, and include support workers and people with disability in the hiring process. Overall, the findings correspond with some of the key capabilities in the NDIS Workforce Capability Framework (i.e., relationship building, individualised support and reflective practice), and provide rich, practical examples from support workers; thus demonstrating the value of lived experience in the development of policy and practice guidelines around quality support provision.

Strengths & limitations

This constructivist grounded theory study is the first to explore the perspective of support workers working with adults with acquired neurological disability around the quality of support and enriches the findings of our previous research [Citation12,Citation19]. The participants represent workers with a range of experience levels, in different settings, under various employment arrangements. There is a broad representation of ages, and the gender split is representative of the workforce [Citation22]. The methodology of the current study was in line with constructivist grounded theory with additional considerations, informed by the literature, for conducting interviews online [Citation47]. Additionally, the first author engaged in reflective journaling, thorough documentation of the interviews and discussions with the second and third authors throughout the analytical process to reduce the risk of researcher bias. Thus, this study is based on rich data grounded in the lived experience of the participants. It must be acknowledged that, although it is promising that support workers in the current study recognise these principles around centring the person with disability, it is a self-selected sample. Therefore, it is likely the participants in this study represent motivated support workers who are invested in improving support provision. Moreover, most of the participants had some link to the advocacy organisation involved in recruiting (i.e., attended forums or supported a person linked to the advocacy organisation), so are likely to be somewhat aligned with the organisation’s principles. This potential selection bias is not necessarily problematic for this research question, as we were looking to understand best support practice, but it is important to note that these findings may not represent the priorities of the support worker population. Finally, this study represents one perspective in the support dyad, and thus should be considered alongside the perspective of people with disability, as their needs and preferences around quality support should be prioritised.

Conclusion

Conducting this qualitative investigation contributes to our understanding of factors that influence the quality of support grounded in the experience of disability support workers. The results illustrate a model of quality support which is consistent with the perspective of adults with acquired neurological disability [Citation19], the broader literature and the rights of people with disability to autonomy over their supports. The current findings have important practice and policy implications regarding the working conditions of the support workforce, suggesting that workers need to feel valued and be better supported to deliver best practice. Moreover, this study demonstrates the complex relational nature of support work, and how important the working relationship is on the realisation of the factors key to the delivery of quality support. Most importantly, this study stresses the importance of centring the autonomy, needs and preferences of the person with disability for quality support provision.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank the disability support workers who generously shared their experiences and perspectives, making this research possible.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Data availability statement

Qualitative data – for purposes of protecting participants identity, this cannot be made available publicly.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bogart KR. The role of disability self-concept in adaptation to congenital or acquired disability. Rehabil Psychol. 2014;59(1):107–115.

- UN General Assembly. Report of the special rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities (theme: access to rights-based support for persons with disabilities) A/HRC/34/58 [Internet] 2016. [cited 2021 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Disability/SRDisabilities/Pages/Reports.aspx

- Redhead R. Supporting adults with an acquired brain injury in the community ‐ a case for specialist training for support workers. Social Care Neurodisabil. 2010;1(3):13–20.

- Iacono T. Addressing increasing demands on Australian disability support workers. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;35(4):290–295.

- Hewitt A, Larson S. The direct support workforce in community supports to individuals with developmental disabilities: issues, implications, and promising pactices. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13(2):178–187.

- Robinson S, Hall E, Fisher KR, et al. Using the ‘in-between’ to build quality in support relationships with people with cognitive disability: the significance of liminal spaces and time. Soc Cult Geogr. 2021;1–20.

- Macdonald F, Charlesworth S. Cash for care under the NDIS: shaping care workers’ working conditions? J Ind Rel. 2016;58(5):627–646.

- Ungerson C, Yeandle S. Cash for care in developed welfare states. Hampshire and New York: Palgrave McMillan; 2007.

- Purcal C, Fisher KR, Laragy C. Analysing choice in Australian individual funding disability policies. Austr J Public Adm. 2014;73(1):88–102.

- Parliament of Australia. National Disability Insurance Scheme Act. Canberra: Parliament of Australia; 2013.

- Cukalevski E. Supporting choice and control—an analysis of the approach taken to legal capacity in Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme. Laws. 2019;8(2):8.

- Topping M, Douglas JM, Winkler D. Factors that influence the quality of paid support for adults with acquired neurological disability: scoping review and thematic synthesis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;44(11):2482–2499.

- Gridley K, Brooks J, Glendinning C. Good practice in social care: the views of people with severe and complex needs and those who support them. Health Soc Care Commun. 2014;22(6):588–597.

- Ahlström G, Wadensten B. Enjoying work or burdened by it? How personal assistants experience and handle stress at work. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2012;11(2):112–127.

- Bourke JA, Nunnerley JL, Sullivan M, et al. Relationships and the transition from spinal units to community for people with a first spinal cord injury: a New Zealand qualitative study. Disabil Health J. 2019;12(2):257–262.

- Braaf SC, Lennox A, Nunn A, et al. Experiences of hospital readmission and receiving formal carer services following spinal cord injury: a qualitative study to identify needs. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(16):1893–1899.

- Wadensten B, Ahlström G. Ethical values in personal assistance: narratives of people with disabilities. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16(6):759–774.

- Wadensten B, Ahlström G. The struggle for dignity by people with severe functional disabilities. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16(4):453–465.

- Topping M, Douglas J, Winkler D. “They treat you like a person, they ask you what you want”: a grounded theory study of quality paid disability support for adults with acquired neurological disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;1–11.

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. NDIS National Workforce Plan: 2021–2025 [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.itsanhonour.gov.au/coat-arms/index.cfm

- National Disability Services. Australian disability workforce report: 2nd edition February 2018. [Internet]. 2018. Available from: www.carecareers.com.au

- National Disability Services. Australian disability workforce report: 3rd edition July 2018; 2018. Available from: https://www.nds.org.au/images/workforce/ADWR-third-edition_2018_final.pdf

- IPSOS. Survey of a representative sample of Australians on the perceptions of disability support work. Australia; 2020.

- Australian Government National Rural Health Commissioner. National Rural Health Commissioner Final Report. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government; 2020.

- Australian Government Department of Jobs and Small Business. The labour market for personal care workers in aged and disability care: Australia 2017. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government; 2017.

- Indigenous Allied Health Australia. Remote and rural Indigenous allied health workforce development. Australia (ACT): Indigenous Allied Health Australia; 2019.

- National Disability Services. State of the Disability Sector Report. Australia: National Disability Services; 2021.

- Cortis N, Blaxland M. Workforce issues in the NSW community services sector (SPRC report 07/17). Social Policy Research Centre. Sydney: UNSW Sydney; 2017.

- Mavromaras K, Moskos M, Mahuteau S, et al. Evaluation of the NDIS: a final report. 2018. Available from: https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/04_2018/ndis_evaluation_consolidated_report_april_2018.pdf

- Moskos M, Isherwood L. Individualised funding and its implications for the skills and competencies required by disability support workers in Australia. Labour Industry. 2019;29(1):34–51.

- Czuba KJ, Kayes NM, McPherson KM. Support workers’ experiences of work stress in long-term care settings: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2019;14:1622356.

- Judd MJ, Dorozenko KP, Breen LJ. Workplace stress, burnout and coping: a qualitative study of the experiences of Australian disability support workers. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(3):1109–1117.

- Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Social Services). Growing the NDIS market and workforce [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.pmc.gov.au/government/its-honour.

- Commonwealth of Australia (National Disability Insurance Scheme Quality and Safeguards Commission). NDIS Workforce Capability Framework. Australia: NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission; 2021.

- Ahlström G, Wadensten B. Encounters in close care relations from the perspective of personal assistants working with persons with severe disablility. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18(2):180–188.

- Nilsson C, Lindberg B, Skär L, et al. Meanings of balance for people with long-term illnesses. Br J Community Nurs. 2016;21(11):563–567.

- McEwen J, Bigby C, Douglas J. What is good service quality? Day service staff’s perspectives about what it looks like and how it should be monitored. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(4):1118–1126.

- Cornwell P, Fleming J, Fisher A, et al. Supporting the needs of young adults with acquired brain injury during transition from hospital to home: the Queensland service provider perspective. Brain Impairment. 2009;10(3):325–340.

- Robinson S, Fisher KR, Graham A, et al. Recasting ‘harm’ in support: misrecognition between people with intellectual disability and paid workers. Disabil Soc. 2022;1–22.

- Robinson S, Graham A, Fisher KR, et al. Understanding paid support relationships: possibilities for mutual recognition between young people with disability and their support workers. Disabil Soc. 2020;1–26.

- Robinson S, Blaxland M, Fisher KR, et al. Recognition in relationships between young people with cognitive disabilities and support workers. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;116:1–9.

- Martinsen B, Dreyer P. Dependence on care experienced by people living with duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(2):82–90.

- Bourke JA. The lived experience of interdependence: support worker relationships and implications for wider rehabilitation. Brain Impairment. 2022;23(1):118–124.

- Fisher KR, Robinson S, Neale K, et al. Impact of organisational practices on the relationships between young people with disabilities and paid social support workers. J Soc Work. 2021;21(6):1377–1398.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Los Angeles (CA): Sage; 2006.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Los Angeles (CA): Sage; 2014.

- Topping M, Douglas J, Winkler D. General considerations for conducting online qualitative research and practice implications for interviewing people with acquired brain injury. Int J Qual Methods. 2021;20:1–15.

- Topping M, Douglas J, Winkler D. Adapting to remote interviewing methods to investigate the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support. In: Sage research methods: doing research online. California, USA: SAGE; 2022.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo [Internet]. 2020. [cited 2021 Dec 2]. Available from: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home?_ga=2.57117602.966813235.1638426383-1710954617.1638426383.

- Constantinou CS, Georgiou M, Perdikogianni M. A comparative method for themes saturation (CoMeTS) in qualitative interviews. Qual Res. 2017;17(5):571–588.

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, et al. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):148.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251.

- Commonwealth of Australia. Royal Commission into violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disability. 2021. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/

- Smyth E, Healy O, Lydon S. An analysis of stress, burnout, and work commitment among disability support staff in the UK. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;47:297–305.

- Hale LA, Jenkins ML, Mayland B, et al. Living with dementia: the felt worth of support workers. Ageing Soc. 2021;41(7):1453–1473.

- Berta W, Laporte A, Perreira T, et al. Relationships between work outcomes, work attitudes and work environments of health support workers in Ontario long-term care and home and community care settings. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):15.

- Ellemers N, Sleebos E, Stam D, et al. Feeling included and valued: how perceived respect affects positive team identity and willingness to invest in the team. Brit J Manage. 2013;24(1):21–37.

- Australian Government. National Disability Insurance Scheme (Practice Standards—Worker Screening) Rules 2018. National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013; 2021. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2020C01138.

- Douglas J, Cruz KD. Participant led training videos. Melbourne: Summer Foundation; 2018.

- Douglas J, D’Cruz K, Winkler D, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of a novel Participant-Led video intervention to train disability support workers. Health Soc Care Community: 1–12; 2022.

Appendix 1. Participant interview schedule

Begin interview by thanking the participant for participating in this study and remind the participant that their participation is voluntary, and they can stop the interview at any time. Give the participant the opportunity to ask questions. Once consent has been re-confirmed verbally, confirm any incomplete items from the demographics form and then use the following questions as an interview guide. Prompt participants as necessary (e.g., tell me more, can you give me an example of a time…) and alter questions and ordering of questions as necessary in line with the participant’s narrative.

Tell me about your background as a support worker

How would you describe your role as a support worker, without using the word support?

What do you like about providing support?/Can you give me examples of positive experiences?

What do you dislike/what is difficult about providing support? Examples of negative experiences

What does high quality support provision look like?

What helps you deliver quality support?

What hinders your capacity to deliver quality support?

How do you know if you have delivered quality support?

What skills or attributes do you think are important to be a good support worker?

What does your relationship look like with the people you support? How do you manage that?

Have you received formal training? Are there things you think support workers should be trained in?

How do you think the quality of support could be improved?

What advice would you give to a new support worker about how to be an excellent support worker?

What is the most important factor that influences the quality of support?