Abstract

Purpose

Insurers often commission psychiatric experts to evaluate the eligibility of workers with mental disorders for disability benefits, by estimating their residual work capacity (RWC). We investigated the validity of a standardized, computer-based battery of established diagnostic instruments, for evaluating the personality, cognition, performance, symptom burden, and symptom validity of claimants.

Methods

One hundred and fifty-three claimants for benefits were assessed by the assembled test battery, which was applied in addition to a conventional clinical work disability evaluation.

Results

A principal component analysis of the test and questionnaire battery data revealed six factors (Negative Affectivity, Self-Perceived Work Ability, Behavioral Dysfunction, Working Memory, Cognitive Processing Speed, and Excessive Work Commitment). Claimants with low, medium, and high RWC exclusively varied in the factor Negative Affectivity. Importantly, this factor also showed a strong association to psychiatric ratings of capacity limitations in psychosocial functioning.

Conclusions

The findings demonstrate that the used test battery allows a substantiation of RWC estimates and of psychiatric ratings by objective and standardized data. If routinely incorporated in work disability evaluations, the test battery could increase their transparency for all stakeholders (insurers, claimants, medical experts, expert case-coordinators, and legal practitioners) and would open new avenues for research in the field of insurance medicine.

The residual work capacity (RWC) estimation by medical experts is internationally good practice, but plagued by a relatively low interrater agreement.

The current study shows that psychiatric RWC estimates and capacity limitation ratings can be substantiated by data from objective, standardized psychometric instruments.

Systematically using such instruments might help to improve the poor interrater agreement for RWC estimates in work disability evaluations.

Such data could also be used for adopting vocational trainings and return-to-work programs to the individual needs of workers with mental health problems.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Aside from its adverse effects on general well-being, sustained health problems often impair the capacity to work and might sometimes lead to disablement. In countries with a developed social security system, workers can in such case claim benefits from the governmental disability insurer or early retirement. The degree of work incapacity is usually critical for granting disability benefits: only sustained and substantial reductions of the work capacity qualify for disability benefits. In Switzerland, the entitlement to disability benefits arises at the earliest if the insured person has been incapacitated for work on average for at least 40% of the time during one year [Citation1]. The amount of Swiss governmental disability benefits depends on the income lost because of health problems. For quantifying this income loss, it is necessary to determine the income generated before the health problems and the income that could still be earned despite the health problems. The determination of the latter income is the much more difficult part, because this income is often hypothetical due to an unemployment of the claimant and depends on the residual work capacity (RWC). The RWC itself is a complex and difficult to access construct, because the impact of health-related problems on work capacity is often elusive, in particular for mental health problems. In order to obtain RWC estimates, disability insurers often commission work disability evaluations to medical experts and neuropsychologists [Citation2].

Conflicts arise when there is a discrepancy between the claimant’s perception of his limitations and the expert’s assessment, resulting in a lower-than-expected granting of benefits [Citation3]. In some cases, such conflicts might originate from the unrealistic expectations of the claimants, their overestimation of their functional limitations, or their subjective belief to “deserve” the disability benefits. However, in other cases, this kind of conflict may arise because the experts underestimated the functional limitations or wrongfully considered them as exaggerated (or even simulated). Related, as shown in a survey, claimants sometimes felt that the medical expert did not give them the trust and respect they needed or the experts were superficial during their work disability evaluation [Citation4]. Claimants complained about occasionally very short face-to-face examinations by the medical expert (<30 min) and that the medical experts gave different diagnoses than the attending physician [Citation4].

Insurance medicine experts have been well aware of the need to ensure quality standards for work disability evaluations. Already in 2003, the Swiss Society for Insurance Psychiatry [Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Versicherungspsychiatrie SGVP] for example published first guidelines in the field of insurance medicine in pursuit of such an aim [Citation5]. The current version of these guidelines recommends in particular which information should be reported in what order in these assessments, with an emphasis on clinical findings and related impairments in activities and participation [Citation6]. The commissioned medical experts do not necessarily have to come to the same conclusion about the claimant’s diagnosis and his functional limitations as the attending physician of the claimant, but they should detail the reasons for doing so to maintain transparency.

However, how exactly can the quality of work disability evaluations be evaluated? The German public pension insurer [Deutsche Rentenversicherung DRV] published a manual to allow for peer reviews of work disability evaluations [Citation7]. The manual contains a list of criteria regarding several aspects of such reports, namely (a) formal layout, (b) intelligibility, (c) transparency, (d) sufficiency, (e) consideration of medical evidence, and (f) economic appropriateness. Comprehensibility represents an overarching criterion. Its fulfillment is regarded as critical and imperative for the quality of the assessment. The Swiss federal office for social insurance [Bundesamt für Sozialversicherung BSV] currently develops an adapted version for Switzerland [Citation8].

Though attempts to assure and to improve the quality of work disability evaluations by manuals and checklists is supported by experts, the details of such quality assurance measures nonetheless still need to be outlined and refined. In 2018, there were alone 4437 poly-disciplinary work disability evaluations in Switzerland [Citation9], with 94% including a psychiatric evaluation. Aside from issues with the selection of criteria that should ideally apply during such quality evaluations, it is likewise important who exactly is going to review the assessments in how many cases and in what depth. (And ultimately: How much funding is available for such quality assurance measures?) For Switzerland, Hermelink and Kocher proposed an in depth analysis of 300 assessments per year, which corresponds to a low one-digit percentage of all work disability evaluations [Citation8]. Given that the mode of work disability evaluations varies between countries [Citation2], no international standards have yet been established for assuring quality standards in the field.

The idea to include the expertise of more than one medical expert for such purpose is not new and some authors proposed that peer review would be highly useful for psychiatric work disability evaluations, as it would facilitate the prevention of fundamental errors, arguing that wrong core assumptions, e.g., about the claimant’s diagnosis could hazard the whole assessment [Citation10]. By the same token, it was reasoned that intervision and supervision, which are established methods for quality control in therapeutic work, could reduce the risk of such flaws in work disability evaluations. Consequently, and somewhat contrary to the more recent concept of the BSV implementing the peer review process after the written assessment, it was suggested that the peer review process be conducted as part of the assessment process [Citation10].

No matter how peer review is implemented in quality control, the complexity of case histories and their documentation represent one major challenge for medical experts, both when evaluating the work disability of claimants and when reviewing the evaluation of a second expert. Medical records are often extensive, might be incomplete, poorly structured, or both, they might contain discrepancies and inconsistencies, might vary in their formal structure, and so forth. Moreover, the medical history needs to be translated into capacity and participation limitations in order to estimate the RWC. Pertinent information is often not at hand, but needs to be extracted from medical records, as well as complemented and verified by interviewing the claimant and by cross-referencing to other sources of information. Psychometric instruments (such as questionnaires, performance or personality tests, or rating scales) might help to structure critical information, to quantify limitations and to highlight important aspects. Unfortunately, for German-speaking countries, there are currently only non-binding recommendations which tests and inventories should be used in work disability evaluations under what circumstances [Citation6,Citation11,Citation12]. To the best of our knowledge, the situation in other countries is similar. Due to the resulting lack of standardization (because experts use different or no tests and inventories), information becomes less accessible for other medical experts and stakeholders. Moreover, the lack of standardization also hampers research, since it prevents the large-scale empirical evaluation of factors modulating the RWC or other outcome variables.

Instruments like the Mini-ICF-APP (Mini-International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)-activity and participation limitations in psychiatric diseases (APP)) allow for a structured data collection [Citation13,Citation14]. The Mini-ICF-APP is a rating instrument for quantifying activity and participation limitations in psychiatric disorders and includes ratings in 13 different domains of social functioning, such as, e.g., adherence to regulations or group integration. The ratings provide both a systematic documentation and quantification of functional limitations. Such data bridge the gap between the psychiatric diagnosis and RWC, and document functional limitations, as perceived by the medical expert [Citation15–18].

In the current study, we sought to investigate the feasibility of a comprehensive, standardized, computer-based battery of diagnostic instruments, which we named Digitally Assisted Standard Diagnostics in Insurance Medicine (DASDIM). The DASDIM incorporates a number of well-established instruments for quantifying various fundamental aspects that are relevant for the work disability evaluation, including mental health, cognition, personality, resilience, and work-related behavior. The DASDIM is accessible via a user-friendly computer interface and allows for an automated analysis of conducted tests. We propagate that the DASDIM can fundamentally increase the transparency and objectivity of work disability evaluations. Moreover, by collecting quantitative, objective, and standardized data, the DASDIM allows for conducting systematic studies in insurance medicine and offers the possibility to evaluate the predictive power of medical assessments.

The current proof-of-concept study aimed to evaluate the usefulness and validity of the DASDIM for work disability evaluations. The study sought to determine the construct validity of the DASDIM, by clarifying which functional dimensions the battery of diagnostic instruments covered and which instruments showed redundancies. In order to test for criterion validity, extracted factor loadings were used as predictors for the RWC (as estimated by the medical expert) and were contrasted between claimants for disability insurance benefits and applicants for early retirement. Based on practical experiences from work disability evaluations, applicants for early retirement were presumed to show fewer capacity limitations, better cognitive functioning, and less symptom burden, as compared to claimants for disability insurance benefits. Moreover, in an exploratory analysis, extracted factor loadings were also compared between participants with different primary psychiatric diagnoses, with some initial evidence suggesting that claimants with personality and behavior disorders show more capacity limitations than claimants with mood disorders or with neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders [Citation18].

Methods

Participants

One hundred and fifty-three claimants (79 female) for disability benefits or applicants for disability-related, early vocational retirement participated in the proof-of-concept study. The recruitment took place at three centers in Switzerland: the medical assessment center asim (Basel University Hospital), the practice network Zurich-Winterthur (G. Ebner, B. Schaub, and T. Cotar), and the assessment center at the Psychiatric University Hospital in Zurich. All participants previously underwent a psychiatric work disability evaluation. Work disability evaluations were commissioned by the Pension Fund Zurich (Pensionskasse Zürich, n = 51), the Swiss governmental disability insurer (IV-Versicherung, n = 97), and the Swiss National Accident Insurance Fund (SUVA, n = 5). Furthermore, participants were required to be between 18 and 65 years old and to have good command of German language, since the interface and test materials of the DASDIM were implemented in German. Moreover, for claimants for disability benefits, the cantonal disability insurance office (IV-Stelle) needed to have agreed to the study. Claimants who required the assistance of interpreters or such who had severe mental deficits, suicidal tendencies, pronounced movement disorders, severe personality disorders, or profound fear of failure were excluded. Study participation was voluntary and participants were granted monetary compensation (100 Swiss francs ≈ 100 US $; further details on the recruitment can be found in Supplementary materials). All participants gave written informed consent to the study. A total of 12 psychiatric experts participated in the study, eight from asim Basel, three from the practice network Zurich-Winterthur, and one from the Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich. The participating psychiatrists were part of the extended research network, who volunteered to the study as part of the conducted work disability evaluations. The DASDIM was supposed to take place in close temporal proximity to the psychiatric work disability evaluation (with maximally 10 days delay), allowing the DASDIM results to be considered in the expert’s report to the insurer. The Ethics Committee Northwest/Central Switzerland approved the study on 17 May 2017 (EKNZ: 2017-00781).

Procedure

In the following, we describe all data collected by the DASDIM. As one key characteristic, the DASDIM contains clinically established psychometric instruments. As such, some medical experts might already have used some of the instruments in work disability evaluations. Aside from the information directly provided by the claimant, socio-demographic information, and information on the RWC was collected by the leading expert case-coordinator (“Fallführer”), usually based on existing records. The psychiatric expert provided additional case information after interviewing the claimant or after extracting relevant information from medical records. Finally, the investigator, who introduced the DASDIM to the claimant and gave technical assistance if necessary, provided additional information. The investigator was either a psychologist or a psychology student, who were trained or experienced in applying all DASDIM tests, questionnaires, and rating scales. Trainings were provided in 1:1 sessions by a research psychologist (VH or GD). The sessions lasted until the investigator was able to use the DASDIM platform without error, and lasted about 1–2 h in total. In some cases, after being trained, the medical expert acted as investigator and was in charge of introducing the DASDIM to the claimant. The expert case-coordinator and the psychiatric expert were the same person in mono-disciplinary work disability evaluations (work disability evaluations involving a single medical expert).

Information provided by the expert case-coordinator

Master data: Demographic information about the claimant, such as age, sex, context of the work disability evaluation, disability status, nationality, country of birth, migration background, native language, command of German, education, professional training, family situation (parents, siblings, family status, children, and partnership), vocational status, last occupation, number of previous vocational activities, number of working years, workload, highest income in work life, current funding, and social benefits.

The RWC (in %) in the last job and an alternative job (a hypothetical job on the general labor market with adjustments to the claimant’s limitations), with differentiating between the average capability of working full time and the total RWC, taking both the average daily work capability and the average job performance into account. The expert case-coordinator provides an integration of the estimated RWC, when several medical experts evaluated the work disability (as it is the case for bi- and poly-disciplinary work disability evaluations).

Information provided by the psychiatric medical expert

Master data: Year of immigration, birth countries of the parents, German command, grown up within the original family, time in foster care, contact with family members (parents, siblings), intimate relationships, friendships, effects of disability on social life, traumatic life events, reduction of working hours, reason for work reduction, stress factors, professional career, layoffs, job changes, funding, expenses, and prognosis.

The RWC (in %) in the last job and an alternative job; the RWC estimates provided by the psychiatric expert are exclusively based on his work disability evaluation and might, therefore, differ from the RWC estimates documented by the expert case-coordinator.

Mini-ICF-APP [Citation14]: Activity and participation limitations in 13 different domains of social functioning, as rated by the medical expert; five levels of limitations are coded from “0” to “4”: (“0”) no impairment; (“1”) mild impairment, some problems in fulfilling circumscribed tasks, with essentially no negative consequences; (“2”) moderate impairment; pronounced problems in performing certain tasks compared to a reference group, with negative consequences for the individual or others, (“3”) severe impairment; the individual can no longer meet role expectations in essential parts and partly requires assistance in circumscribed activities; (“4”) full impairment, i.e., the required activities need to be done by others.

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV R) [Citation19]: a single scale to rate the overall functioning of the claimant from 0 to 100%.

Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale contains ratings for assessing the severity of the disorder, the global improvement (by therapeutic interventions), and the therapeutic efficacy (weighting therapeutic benefits and adverse side effects) [Citation20].

Information provided by the claimant via computerized testing and questionnaires

Master data: Momentary well-being, last night’s sleep quality, recent changes in medication, last consumption of alcohol and other recreational drugs, native language, command of German, handedness, impairments in vision and hearing, as reported by the claimant;

Estimation of the premorbid IQ based on socio-demographic information [Citation21];

Test of Attentional Performance (TAP Version 2.3): Subtest alertness [Citation22];

Screening of cognitive impairments (Montreal Cognitive Assessment MoCA, Alternative Version 2) [Citation23];

Digit span memory (forward and backward, subtest from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale WAIS-IV, German adaption) [Citation24];

Short Form SF-36 Health Survey: Self-reported health status of the claimant [Citation25];

WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) 2.0, 12 item version, self-reported functional limitations in daily activities [Citation26];

Work Ability Index (WAI) [Citation27], self-reported work ability of the claimant;

Work-related behavior and experience patterns ([Arbeitsbezogenes Verhaltens- und Erlebensmuster AVEM]) [Citation28]; 44-item version; self-reported experiences with stress and failure in work;

Personality: Munich Personality Inventory ([Münchener Persönlichkeitstest MPT]) [Citation29]: 49 items; assessment of extraversion, neuroticism, frustration tolerance, rigidity, tendency to isolate, esoteric tendencies, and norm orientation;

Psychopathology and personality: Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2 Restructured Form Research Version (MMPI-2-RF) [Citation30,Citation31]; 338 items, nine validity scales, three higher-order scales, nine clinical scales, 23 specific problems scales, two interest scales, and five personality scales;

Behavioral evaluation of the claimant at testing (five-point rating scale, modified version of [Citation32], as observed by the investigator: need for breaks, understanding of the instructions, working speed, test motivation, complaining behavior, and signs of fatigue.

DASDIM platform

Once a claimant agreed to study participation, the data manager of the study created a case identity number. The expert case-coordinator, psychiatric expert, and investigator were informed and were granted access to the DASDIM interface pages of this case, each confined to his assigned role in the DASDIM. After entering the requested information, each of them closed the case in order to avoid data corruption or data loss by unintentionally re-opening a case and by erasing previously entered information by mistake. Only the data manager of the study (one of the authors, GD) who supervised the data collection had unlimited data access and could re-open a case. The interface of the DASDIM also provided some feedback about data that still had to be entered by one of the operators in charge. In case of missing data, the data manager requested data completion by the respective operator.

All psychometric instruments were presented on a computer interface and responses were, in most instances, directly entered into this interface. Moreover, the data were automatically analyzed and summarized as z-scores, based on normative data of the psychometric instruments. These data were summarized in the individual DASDIM report. This report documented and visualized the key results of the claimant’s DASDIM (for an exemplary excerpt Supplementary Figure S1).

Statistics

Major aims of the statistical analyses

The analyses sought to reveal empirically the functional dimensions covered by the used psychometric instruments. To this end, collected data were subjected to principal component analyses (PCAs). Two PCAs were calculated, one for the ratings of psychiatric medical experts for describing the functional limitations and health impairments (Mini-ICF-APP, GAF, and CGI), and one for the computerized test and questionnaire data of the claimants.

In order to evaluate the criterion validity of the extracted dimensions (“factors”), factor scores were compared between claimants for disability benefits and claimants for early retirement. This analysis was conducted to show whether the factor scores were sufficiently sensitive to reveal such (to-be-expected) group differences. Moreover, the factor scores were compared between participants diagnosed with different mental disorders. Within claimants for disability benefits, the factor scores were compared between claimants with low, medium, and high RWC, providing information about which dimensions were presumably most relevant for the psychiatric expert when estimating the RWC. As to further elucidating this issue, we also investigated whether there was a statistical association between the dimensions of the psychiatric expert ratings and the claimant’s test and questionnaire data.

Principal component analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and with the R statistical computing environment v 4.0.4 (Vienna, Austria) [Citation33]. PCAs were conducted with SPSS based on correlation matrices, using a principal component approach. Suitability of the correlation matrices for factorization was assessed by Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (BTS) [Citation34] and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) [Citation35]. The number of extracted factors was determined by the elbow criterion, based on the scree plot [Citation36]. The initial PCA solution was orthogonally rotated (varimax) in order to achieve a simple structure with items loading high on individual factors and low on others. Individual factor scores were extracted as regression scores.

General goal of the PCAs was to find parsimonious and well interpretable factor solutions that would allow describing the most important functional dimensions underlying the multitude of deployed instruments. Scales were assigned to the factor onto which they had the highest absolute factor loadings with a threshold of |0.5|. A possible factor solution was evaluated based on two main criteria: (A) Interpretability – the majority of scales loading above threshold on a factor should be semantically sound and represent a nameable higher order concept. (B) Simple structure – The majority of scales associated with a given factor should have low loadings onto any other factor, i.e., less than 0.3. Scales with all factor loadings <|0.5| were presumed not to be reflected by the factor solution.

Missing and excluded data

Sixteen values of the claimants’ test and questionnaire data (0.1%) were missing, that was one missing submission of the AVEM (11 values), two instances of not quantifiable complaining behavior during DASDIM assessment, and two irretrievable entries of the WAI, which prevented the calculation of the respective WAI Total Score in one case. From the psychiatric experts’ instruments, in a single case the CGI Efficacy Index was unavailable (0.04%). Such missing data were imputed using a random forest-based technique (package missForest) [Citation37].

Scales used for symptom validation were not considered in the current analysis study and will be published separately, due to the complexity of this issue. These unconsidered scales encompassed the nine MMPI-2-RF validity scales and the TAP Alertness Performance Validity Scale. Of note, scores in the symptom validity scales were largely inconspicuous.

Group comparisons

Demographic sample characteristics were compared between claimants for disability benefits (work disability evaluations commissioned by the governmental disability insurer) and applicants for early retirement (commissioned by the Pension Fund Zurich) by Wilcoxon’s rank sum test. Due to the small number and the structural similarity of the accident insurance cases with disability insurance cases, these cases were merged with the disability insurance cases.

The individual factor scores (as extracted from the psychiatric ratings, as well as from the test and questionnaire data) were compared between the two commissioning bodies (disability insurer vs. pension fund) by one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA). Moreover, the factor scores were compared between participants diagnosed with different mental disorders by one-way ANOVAs, comparing the scores between participants with mood disorders (ICD-10 F3x), neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F4x), and disorders of adult personality and behavior (F6x) as the participants’ primary psychiatric diagnosis. The effects of RWC on the factor scores were exclusively tested in claimants for disability benefits. To this end, the claimants were grouped according to their RWC level, based on the psychiatric expert’s RWC estimate in an alternative job, which is most relevant for the eligibility for disability benefits. Low RWC was defined as an RWC estimate <40%, Medium RWC as an RWC ≥40% and ≤60%, and High RWC as an RWC >60%. This categorization is similar to ones used in previous research [Citation16,Citation18]. In Switzerland, if the degree of invalidity is less than 40%, there is no entitlement to a governmental disability pension. The individual factor scores were compared by one-way ANOVAs between Low, Medium, and High RWC. All significant effects of Diagnoses and RWC Level were further evaluated by calculating least significant difference post hoc tests. Potential associations between the dimensions of the psychiatric ratings and of the DASDIM instruments were analyzed by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients and a multiple stepwise regression. The analysis of RWC was restricted to claimants for disability benefits, because in applicants for early retirement work capacity referred to the applicants’ capacity to work on their current position and at the very time point of the evaluation.

Eta squared (η2) is reported as effect size for the ANOVAs, with small, medium, and large effects reflected by values off equal to 0.0099, 0.0588, and 0.1379 [Citation38,Citation39]. For group contrasts of non-normally distributed data, the Pearson correlation coefficient r is provided as effect size measure (small effect: r ≥ 0.1, medium effect: r ≥ 0.3, large effect: r ≥ 0.5) [Citation40]. The significance level was set to α = 0.05.

Results

Demographic sample characteristics

Of the 153 participants, 102 were claimants for disability benefits (including five injury-related cases commissioned by the SUVA) and 51 were applicants for early retirement, commissioned by the Pension Fund Zurich. shows the demographic characteristics of the total sample as well as of its two subsamples, defined by the commissioning bodies. Statistical comparisons of the two subsamples revealed that the two groups did not differ in age, but applicants for early retirement had more years of education (school and professional training), a higher premorbid IQ, and a higher maximal annual income in the past, as compared to claimants for disability benefits. Moreover, the large majority of the work disability evaluations commissioned by the pension fund were monodisciplinary psychiatric evaluations (48 of 51), in contrast to the small number of monodisciplinary work disability evaluations related to disability claims (seven of 102). This difference was due to the recruitment. The practice network Zurich-Winterthur conducted all work disability evaluations, commissioned by the pension fund, whereas the assessment center asim had some focus on multidisciplinary work disability evaluations, commissioned by the governmental disability insurer. Across both contracting bodies, most participants had mood/affective disorders (ICD-10 F3x), neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F4x), or disorders of adult personality and behavior as primary psychiatric diagnosis (F6x, ). Within claimants for disability benefits, participants with F6x diagnoses also showed a lower RWC as compared to participants with F3x and F4x diagnoses (F2,74 = 6.428, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.148; F3x: mean RWC = 54.5, standard deviation (SD) = 28.2; F4x: mean RWC = 53.6, SD = 40.7; F6x: mean RWC = 25.7, SD = 24.3).

Table 1. Demographic sample characteristics.

Table 2. Number of the participants’ main primary ICD-10 F-diagnoses.

Principal component analyses

Psychiatric ratings

The set of psychiatric experts’ rating instruments comprised the 13 capacity limitation ratings of the Mini-ICF-APP, the GAF score, and two CGI ratings (severity of disease and efficacy index). Data met the prerequisites for PCA (BTS: χ2(120) = 1499.10, p < 0.001; MSA = 0.927). All scales except Mini-ICF-APP – Mobility and CGI – Efficacy Index showed high loadings (>|0.5|) on the first factor. Therefore, a one-factor solution was deemed appropriate (Supplementary Table S1). As the factor showed high factor loading on scales describing capacity limitations and a negative loading on the global functioning scale (GAF), the factor was presumed to reflect limitations of psychosocial capacities.

Claimant test and questionnaire data

A total of 103 test and questionnaire scales were entered as variables into the second PCA (AVEM: 11 scales, Behavioral Evaluation: six scales, Digit Span: seven scales, MMPI-2-RF: 42 scales, MoCA: one scale, MPT: 11 scales, Premorbid IQ: two scales, SF-36: 11 scales, TAP Alertness: five scales, WAI: 10 scales, WHODAS 2.0: one scale). All included scales can be derived from Table S2 in Supplementary materials. The appropriateness of the correlation matrix for PCA was confirmed by BTS (χ2(5253) = 17664.42, p < 0.001) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin MSA = 0.71.

A six-factor solution provided a simple structure and good interpretability of the factors; it explained 52.8% of the total variance of the test and questionnaire data. When considering more than six factors, any additional factor showed only one or two loadings >|0.5|. For each factor of the six-factor solution (Fa1 to Fa6), the scales with the five highest factor loadings are displayed in (see Table S2 in Supplementary materials for a complete list with the factor loadings of all 103 scales).

Table 3. Factor loadings and communalities (h2) for the test and questionnaire data.

Factor 1 (Fa1) was dominated by MMPI-2-RF scales reflecting dispositions for psychological distress and negative emotionality, as well as related SF-36 and AVEM scales, such as the AVEM scale Tendency to Resignation (Table S2). Fa1 was labeled Negative Affectivity. Factor 2 (Fa2 Self-Perceived Work Ability) was mainly formed by the WAI scales describing demand-related work ability with an emphasis on physical/somatic aspects. Physical/somatic scales of the SF-36 supported that scope. Factor 3 (Fa3 Behavioral Dysfunction) exclusively clustered the MMPI-2-RF scales of behavioral and mainly externalizing dysfunctions associated with dispositions for hyperactivity, aggression, and psychotic distortions of thoughts and experiences. Factor 4 (Fa4 Working Memory) was lead on by Reliable Digit Span encompassing all other scales of the Digit Span test. Factor 5 (Fa5 Cognitive Processing Speed) was formed by the TAP Alertness scales (except TAP Phasic Alertness), as well as the DASDIM examiners’ evaluation of working speed. Factor 6 (Fa6 Excessive Work Commitment) was led by the MPT scale Rigidity and contained AVEM scales expressing a highly dedicated attitude toward work. Of note, 29 of the 103 scales entered into the PCA, did not show loadings>|0.5| on any of these six factors (Table S1).

Across the total sample, the factor Limitations in Psychosocial Capacity (FaPsy) that was determined from the psychiatric ratings showed significant correlations with four of six test and questionnaire factors (Fa1 Negative Affectivity: r = 0.498, p < 0.001; Fa2 Self-Perceived Work Ability: r = −0.175, p = 0.030; Fa5 Cognitive Processing Speed: r = −0.174, p = −0.032; Fa6 Excessive Work Commitment: r = −0.203, p = 0.012). Fa1 Negative Affectivity explained 24.8% of the variance of Limitations in Psychosocial Capacity, all four factors with significant correlations explained 35.0% of its variance, as shown in a multiple stepwise regression (Table S3).

Claimants for disability insurance benefits and for early retirement

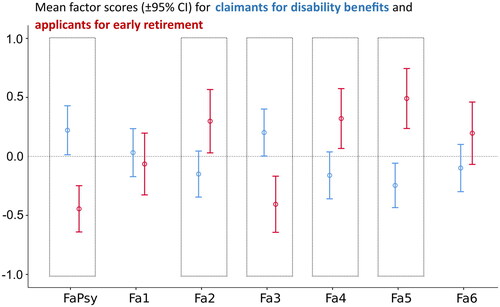

displays the comparison of the extracted factor scores between claimants for disability benefits and applicants for early retirement. Limitations of Psychosocial Capacities (FaPsy) were significantly less pronounced in applicants for early retirement (mean score = −0.444, SD = 0.697), as compared to claimants for disability benefits (mean score = 0.222, SD = 1.056; F1, 151 = 16.627, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.099). With regard to the test and questionnaire data, applicants for early retirement exhibited better Self-Perceived Work Ability (Fa2, F1, 151 = 7.102, p = 0.009, η2 = 0.045), less Behavioral Dysfunction (Fa3, F1, 151 = 13.614, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.083), and they presented better Working Memory functions (Fa4, F1, 151 = 8.259, p = 0.005, η2 = 0.052) and Cognitive Processing Speed (Fa5, F1, 151 = 20.846, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.121) than claimants for disability benefits. The groups did not significantly differ in Negative Affectivity (Fa1, F1, 151 = 0.314, n.s., η2 = 0.002) and Excessive Work Commitment (Fa6, F1, 151 = 2.998, n.s., η2 = 0.014).

Figure 1. Factor score profile of claimants for disability benefits and applicants for early retirement. Claimants for disability benefits (blue bars) exhibited higher scores in the factor FaPsy Limitations in Psychosocial Capacity, as obtained from the psychiatric ratings, and in Behavioral Dysfunction (Fa3), as well as lower scores in the factors Self-Perceived Work Ability (Fa2), Working Memory (Fa4), and Cognitive Processing Speed (Fa5), as compared to applicants for early retirement (red bars). The two groups did not vary in Negative Affectivity (Fa1) and Excessive Work Commitment (Fa6). Significant group differences are marked by the dashed boxes.

Claimants with different primary psychiatric diagnoses

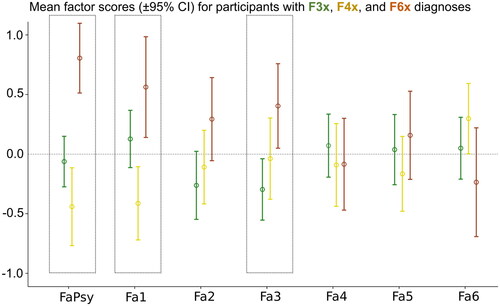

displays the comparison of the extracted factor scores between participants with F3x, F4x, and F6x diagnoses. Participants with these diagnoses varied in Limitations of Psychosocial Capacities (FaPsy, F2, 119 = 17.727, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.230). Participants with F6x diagnoses showed more limitations than participants with F3x diagnoses (mean difference: 0.868, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.477 − 1.258) and F4x diagnoses (mean difference: 1.246, 95%CI: 0.826–1.666). Participants with F3x diagnoses exhibited slightly higher scores than participants with F4x diagnoses (mean difference: 0.379, 95%CI: 0.024–0.733).

Figure 2. Factor score profile of claimants with different psychiatric diagnoses. Participants with F6x diagnoses (brown bars) exhibited higher scores FaPsy Limitations in Psychosocial Capacity, Negative Affectivity (Fa1), and Behavioral Dysfunction (Fa3), as compared to participants with F3x and F4x diagnoses (green and yellow bars, respectively). The groups did not vary in Self-Perceived Work Ability (Fa2), Working Memory (Fa4), Cognitive Processing Speed (Fa5), and Excessive Work Commitment (Fa6).

Participants with various psychiatric diagnoses also significantly differed in two factors extracted from the test and questionnaire data, namely in Negative Affectivity (Fa1, F2, 119 = 8.667, p < 0.001 η2 = 0.127) and Behavioral Dysfunction (Fa3, F2, 119 = 4.823, p = 0.010, η2 = 0.075). In detail, participants with F6x diagnoses had significantly larger scores in Negative Affectivity than participants with F4x diagnoses (mean difference: 0.975, 95%CI: 0.504–1.446) and on trend larger scores than participants with F3x diagnoses (mean difference: 0.435, 95%CI: −0.003 to 0.872). Participants with F4x diagnoses had larger scores in Negative Affectivity than participants with F3x diagnoses (mean difference: 0.540, 95%CI: 0.142–0.938). With regard to Behavioral Dysfunction (Fa3), participants with F6x diagnoses had significantly larger scores than participants with F3x diagnoses (mean difference: 0.700, 95%CI: 0.253–1.147) and showed a trend toward larger scores than participants with F4x diagnoses (mean difference: 0.441, 95%CI: −0.038 to 0.923). The latter two groups showed similar scores in Behavioral Dysfunction (mean difference: 0.258, 95%CI: −0.147 to 0.664). No significant differences between participants with different primary ICD-F diagnoses were observed for Self-Perceived Work Ability (Fa2, F2, 119 = 2.948, n.s., η2 = 0.047), Working Memory (Fa4, F2, 119 = 0.377, n.s., η2 = 0.006), Cognitive Processing Speed (Fa5, F2, 119 = 0.867, n.s., η2 = 0.014), and Excessive Work Commitment (Fa6, F2, 119 = 2.306, n.s., η2 = 0.037).

Claimants for disability benefits with different levels of residual work capacity

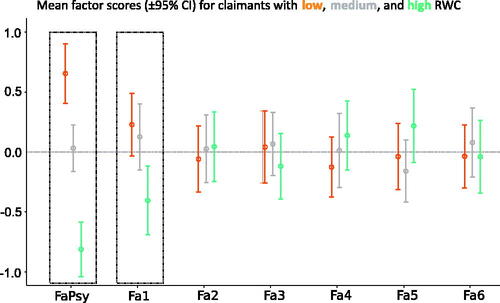

displays the comparison of the factor scores between claimants for disability benefits with low, medium, and high RWC. There were 37 claimants for disability benefits with low RWC, 37 with medium RWC, and 28 with high RWC. More severe Limitations of Psychosocial Capacities were associated with lower RWC levels (FaPsy; F2, 99 = 87.249, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.638). Post hoc examination revealed that the capacity limitations significantly varied between Low RWC and Medium RWC (mean difference: 0.944, 95%CI: 0.648–1.240), Low RWC and High RWC (mean difference: 2.123, 95%CI: 1.804–2.442), as well as between Medium and High RWC (mean difference: 1.179, 95%CI: 0.860–1.498).

Figure 3. Factor score profile of claimants for disability benefits with different levels of RWC. Claimants with different levels of RWC showed significant differences in the factor FaPsy Limitations in Psychosocial Capacity, as obtained from the psychiatric ratings, and the factor 1 (Fa1) Negative Affectivity. They did not vary in the factors Self-Perceived Work Ability (Fa2), Behavioral Dysfunction (Fa3), Working Memory (Fa4), Cognitive Processing Speed (Fa5), and Excessive Work Commitment (Fa6).

Loadings in Negative Affectivity also varied with the level of RWC (Fa1; F2, 99 = 6.471, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.116). Post hoc tests showed that claimants with high RWC had significant lower factor scores in Negative Affectivity than claimants with low RWC (mean difference: −0.819, 95%CI: −1.308 to −0.330) and medium RWC (mean difference: −0.745, 95%CI: −1.234 to −0.256). In contrast, no such group differences were found for other factors derived from the test and questionnaire data: Self-Perceived Work Ability (Fa2, F2, 99 = 0.319, n.s., η2 = 0.006), Behavioral Dysfunction (Fa3, F2, 99 = 0.020, n.s., η2<0.001), Working Memory (Fa4, F2, 99 = 1.390, n.s., η2 = 0.027), Cognitive Processing Speed (Fa5, F2, 99 = 0.511, n.s., η2 = 0.010), and Excessive Work Commitment (Fa6, F2, 99 = 1.032, n.s., η2<0.020). Post hoc analyses of all test and questionnaire scale data by one-way ANOVAs showed that 15 out 19 significant effects of RWC Level were found for scales with loadings above |0.5| on Fa1 Negative Affectivity (Table S4).

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the feasibility of a comprehensive, standardized, computer-based battery of clinically established diagnostic instruments in psychiatric work disability evaluations and assessed the construct and criterion validity of this battery.

Construct validity: factor structure of the test and questionnaire data

The test and questionnaire battery was compiled to determine characteristics of claimants for disability benefits (or early retirement) that were considered as potentially relevant for the granting or decline of such benefits. A PCA was run in order to assess which dimensions were covered by these instruments and to evaluate the clinical relevance of these dimensions. Six factors explained 52.8% of the total data variance, with two factors covering aspects of personality and mental health, two factors covering cognition, one factor each covering self-perceived work ability and work commitment.

Psychopathology and personality

The differentiation of psychopathology and personality in just two dimensions, Negative Affectivity (Fa1) and Behavioral Dysfunction (Fa3), is without doubt a coarse one, in particular as compared to the multi-dimensional inventories used in the DASDIM (such as the MMPI-2-RF and MPT). Negative Affectivity and Behavioral Dysfunction might be understood as higher-order factors, thus as broad dimensions underlying psychopathology and personality, similar to higher-order factors likewise described by the MMPI-2-RF (Emotional/Internalizing Dysfunction, Behavioral/Externalizing Dysfunction, and Thought Dysfunction). The DASDIM factor Negative Affectivity showed a strong association with the MMPI-2-RF higher order factor Emotional/Internalizing Dysfunction, whereas the DASDIM factor Behavioral Dysfunction showed high correlations with both of the other two MMPI-2-RF higher-order factors, Behavioral/Externalizing Dysfunction and Thought Dysfunction, not just one (Table S2). Thus, the here obtained factor structure of psychopathology and personality varies from the one proposed for the MMPI-2-RF. The finding might suggest that in our sample Behavioral/Externalizing Dysfunction and Thought Dysfunction often co-occurred. The differentiation of Emotional/Internalizing Dysfunction and Behavioral/Externalizing Dysfunction resembles differentiation of positive and negative symptoms, i.e., an excess or diminution of normal functions, is well established for qualifying and quantifying symptom severity in patients with mental disorders, as for example demonstrated by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [Citation41]. Interestingly, the original PANSS study also described an association between positive symptoms and unusual thought content, similar to our finding.

In contrast to pure symptom scales like the PANSS, the scales underlying Negative Affectivity and Behavioral Dysfunction capture both, personality traits and symptoms. Scales of the MMPI-2-RF but also of other instruments (AVEM, MPI, and SF-36) contributed to the factor Negative Affectivity, whereas exclusively scales of the MMPI-2-RF contributed to Behavioral Dysfunction (Table S1). Some of the MMPI-2-RF scales contributing to Negative Affectivity and Behavioral Dysfunction allow a differential diagnosis of major depressive disorder and schizophrenia, as previously shown [Citation42,Citation43], underlining the construct validity of these scales and their clinical relevance.

Cognition

In contrast to the two aforementioned psychopathology and personality factors, the two extracted factors Working Memory (Fa4) and Cognitive Processing Speed (Fa5) were largely based on two single instruments, namely the subtest Digit Span from the WAIS-IV [Citation24] and the subtest Alertness from the TAP [Citation22]. These two tests tap into the larger psychological domains of attention and memory, but reflect just two subdomains. Attention has been defined as comprising functions of alerting, orienting, and executive control [Citation44]. The memory system encompasses functions of working memory, sometimes also labeled as short-term memory, and long-term memory, which again is divided into declarative and non-declarative memory [Citation45–47]. Hence, it becomes self-evident that these two tests reflect a limited, but utmost important spectrum of cognitive performance. However, the inclusion of instruments measuring cognitive functions was not intended to substitute a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, which is mandatory when cognitive impairment or dementia is suspected. Other cognitive indices of the DASDIM (MoCA Total Score, the Premorbid Total IQ, and Verbal IQ) showed some positive correlations with Working Memory and Cognitive Processing Speed, but factor loading of these scales were below |0.5| (Table S1). Some of the investigator’s Behavioral Evaluations of the claimant’s testing behavior, such as Working Speed and Understanding of Instruction, showed loadings above |0.5| on Cognitive Processing Speed, suggesting that external observers, be it the employer or an assessor, are able to perceive abnormalities indicated by this cognitive factor.

Self-Perceived Work Ability (Fa2)

Scales of the WAI [Citation27] and SF-36 [25] contributed to the factor Self-Perceived Work Ability. This factor reflects impairments of work capacity from the claimant′s point of view, whereas the RWC represents medical expert’s estimate of claimant’s work capacity. SF-36 scales contributing to this factor were among others Bodily Pain and Physical Functioning, emphasizing somatic or physical health aspects.

Excessive Work Commitment (Fa4)

This factor was primarily composed of four AVEM scales [Citation48], complemented by the MPT factor Rigidity [Citation29]. Fa4 widely corresponded to the AVEM factor Work Commitment, which summarizes five of its scales (Subjective Importance of Work, Work-related Ambition, Willingness to Work Until Exhausted, Striving for Perfection, and Distancing Ability). In our study, the scale Distancing Ability showed higher factor loadings on Negative Affectivity (Fa1) than on Excessive Work Commitment. Of note, no MMPI-2-RF scale showed high loadings on Excessive Work Commitment, even though the MMPI-2-RF otherwise covers broad aspects of psychopathology and personality.

DASDIM scales poorly reflected the six-factor solution

Given the heterogeneity of the scales subjected to the PCA, it is little surprising that not all scales were reflected in the six-factor solution, as indicated by the low communality of some scales (h2, Table S2). Examples for scales with low communality are MMPI – Multiple Specific Fears (h2 = 0.206) or pm IQ – Premorbid Verbal IQ (h2 = 0.212). Some other scales, such as MMPI – Neurological Complaints, did not show factor loadings>|0.5|. The fact that some scales had only a minor contribution to any of the six factors does not qualify them as irrelevant for work disability evaluations. Low or high levels in these scales may nevertheless be linked to impaired work capacity. One such example for the current sample is MPT-Extraversion (h2 = 0.464), where low scores of Extraversion were significantly associated with low RWC (Table S4). In the context of work disability evaluations, some other scales with low factor loadings may be considered negligible based on theoretical considerations, such as MMPI-Mechanical-Physical Interests or MPT-Esoteric Inclinations. However, the MMPI-2-RF and the MPT have been validated in their entirety. Therefore, items of MMPI-2-RF and MPT scales that deem to be irrelevant for the purpose of work disability evaluations cannot easily be omitted when using these questionnaires, also considering copyright issues.

Criterion validity

Scores of Fa1 to Fa6 and FaPsy were compared between claimants for disability insurance benefits and for early retirement, between participants with different primary psychiatric diagnoses, and between claimants for disability benefits with different levels of RWC, as estimated by the medical expert for a limitation-adapted work environment.

Claimants for disability insurance benefits and for early retirement

The two groups of participants were defined by the context and the kind of work disability evaluation. In almost all participants, mental problems were prominent and affected to some extent the work ability. The two groups were expected to differ, with claimants for early retirement showing better psychosocial functioning and better cognition than claimants for disability benefits. Applicants for early retirement were usually still regularly employed and often worked in the public sector (e.g., as police officers, teachers, or nurses). Claimants for disability insurance benefits encompassed a much broader range of occupation, some of them poorly trained, some out-of-work for years, and some never having been regularly employed for a substantial period of time. The comparison of demographic data confirmed this assumption, with claimants for early retirement showing more years of education, a higher premorbid IQ, and a higher maximal annual income in the past. In agreement with our assumption, claimants for early retirement showed fewer Limitations in Psychosocial Capacity and better Working Memory and Cognitive Processing Speed (). They also exhibited better Self-Perceived Work Ability and fewer Behavioral Dysfunction, as compared to claimants for disability benefits. In contrast to the latter, Negative Affectivity was quite similar in both groups, which might be referred to the fact that mood disorders were the most frequent diagnoses in claimants for early retirement. The analysis showed that the two groups of participants can be discriminated on the basis of their DASDIM data. The group data differed in the expected direction and the derived factor scores allowed a concise description and comparison of the two samples.

Claimants with different primary psychiatric diagnoses

An important issue from a medical insurance point of view is how the diagnostic groups (F3x/F4x/F6x; ICD-10) differ in terms of the factors. The results show that especially the factor profile in personality disorders (F6x) significantly differed from the profile of other psychiatric disorders. In the presence of a diagnosis in the personality domain, claimants showed significantly more Limitations in Psychosocial Capacity than claimants with mood disorders (F3x) or with neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F4x), replicating a previous finding in a large sample of claimants for disability benefits, based on Mini-ICF-APP data [Citation18]. The current finding extends this previous finding because it shows that claimants with personality disorders are characterized by more pronounced Negative Affectivity and Behavioral Dysfunction, as compared to others, which might have contributed to their limitations in psychosocial functioning. Within claimants for disability benefits, individuals with personality disorders also showed lower RWCs, as compared to other claimants, again replicating previous findings [Citation18]. However, as previously argued, the severity of capacity limitations in claimants with personality disorder (and their low RWCs) is not necessarily to be expected, given the high prevalence of personality disorders in the general population [Citation49]. Further research is required to understand why the rate of claimants with personality disorders and mild impairments in RWC is low. In the current sample, none of these claimants showed an RWC >60%.

Claimants with different RWC levels

The RWC is a critical measure to determine whether a claimant is eligible for disability benefits or not. It is internationally good practice to commission the RWC estimation to independent experts [Citation2]. Nevertheless, the field is plagued by the relatively low agreement between medical experts, when evaluating the same individual [Citation50–52]. The recent meta-analysis showed that the interrater agreement could be improved when structured instruments guided work disability evaluations [Citation50].

In the current study, the DASDIM battery was applied in addition to the conventional psychiatric work disability evaluation, which is primarily based on a clinical interview with the claimant and the consideration of medical and work records. It is important to point out that the psychiatric experts of our study were free to consider the information provided by the DASDIM report in their work disability evaluation. The DASDIM report provided scale-dependent z-scores (Figure S1), but did not contain factor scores. The factor scores were calculated just after the data had been collected and all cases had been closed. Future studies need to show whether using the DASDIM battery would improve the interrater agreement of work disability evaluations.

Negative Affectivity and Behavioral Dysfunction were expected to have a significant impact on a function-related assessment, since both reflect dysfunctional behavioral patterns impairing the capacity for work participation. Impairments in Working Memory and Cognitive Processing Speed might also diminish the capacity for work participation. Likewise, Excessive Work Commitment has been associated with burnout [Citation53,Citation54] which in turn might result in work disability [Citation55]. With regard to Self-Perceived Work Ability, it is more difficult to make predictions for its association with RWC. On the one hand, population-based studies have shown that workers with poor self-perceived work ability exhibited an increased likelihood for applying for disability benefits [Citation56] and granting of disability benefits [Citation57,Citation58]. On the other hand, claimants for disability benefits were also reported to overestimate their limitations in work capacity [Citation3].

Somewhat surprisingly, we only found a negative relationship between Negative Affectivity and RWC. However, the lack of associations between RWC and other test and questionnaire factors might possibly be referred to methodological issues:

As outlined further above, RWC assessment in its current form is suffering from low interrater reliability. The resulting proneness to misclassification of low, medium, and high RWC individuals weakens the discovery of associations between test and questionnaire factors and RWC.

Some individual characteristics presumably need to be pronounced before they unfold their impact on work capacity. This might for example explain the absence of associations between Behavioral Dysfunction and RWC in the study sample. When inspecting the z-values of MMPI-2-RF scales contributing to this factor, such as Thought Dysfunction or Antisocial Behavior, the average z-values of these scales were inconspicuous for all three RWC levels (Table S4). In other words, high levels of Thought Dysfunction or Antisocial Behavior were rare among the claimants for disability benefits. Likewise, only few participants exhibited pronounced Working Memory deficits. In cohorts with a higher proportion of claimants with F2x diagnoses or with organic brain dysfunctions, increased Behavioral Dysfunction and limitations of Working Memory might indeed allow a differentiation of claimants with different RWC levels. Interestingly, although objective performance in working memory tasks did not differ between RWC levels, subjective cognitive complaints (MMPI-scale, Table S4) were highest in low RWC level and lowest in high RWC level.

For differentiating claimants with different RWC levels, it is also necessary to have sufficient data variance. Cognitive Processing Speed was apparently impaired for the total sample of claimants for disability benefits, with a mean z-score for TAP alertness <–1 (Table S4). Thus, reduced Cognitive Processing Speed may be considered as a frequent characteristic of these claimants, as also suggested by the marked reduction of Cognitive Processing Speed in comparison to applicants for early retirement (). The same applied for the Self-Perceived Work Ability, which claimants usually rated as low.

Finally, individuals might have low RWC for various reasons. Given this, averaging across individuals with low RWC might just have revealed impairments that were predominantly present in the study sample.

Psychiatric ratings and RWC

The central task of an insurance medical assessment is to determine the individual capacity restrictions in daily life and, essentially, to determine the RWC. It is generally recommended that the expert assessment of functionalities be supplemented by structured procedures. Especially ratings of the Mini-ICF-APP have become increasingly established for this purpose [Citation15]. In the present study, scales from Mini-ICF-APP, CGI, and GAF were used to derive the factor Limitations of Psychosocial Capacities. In line with previous studies [Citation16–18], claimants for disability benefits with low, medium, and high RWC showed significant differences with regard to this factor. However, the close association between these ratings and RWC estimate should not be overvalued since the experts rated the Limitations of Psychosocial Capacities and estimated the RWC. Hence, misjudgments by the experts would consequently affect both. In other words, the strong association between the two measures does not foster their validity. Moreover, even though there is a robust association between the two measures, about half of the RWC variance still remains unexplained when considering Mini-ICF-APP ratings [Citation18].

In addition, in daily routine, the value of the Mini-ICF-APP is weakened by the fact that the information leading to the rating is often poorly described and sometimes not even reported. Consequently, in clinical practice, applicant information, preliminary findings, external reports, test performance, and examination findings should be rigorously incorporated into these ratings and explicitly indexed, for example by “narrative explanation” [Citation18,Citation59]. Such a narrative explanation might for example line out that the expert considers a claimant (working as chemical-technical assistant) to have severe limitations in adherence to regulations because that claimant repeatedly violated laboratory protocols by leaving potentially hazardous chemicals in plain sight, unguarded, and showing no insight. He also went AWOL from mandatory lab meetings. Such descriptions explain to other parties the aspects of the applicant’s behavior that led the expert to his assessment. In clinical practice, such narrative explanations should provide descriptions of all 13 Mini-ICF-APP domains, i.e., they should be detailed and not just describing global functional impairment (as used here for scientific data aggregation).

In our study, we observed significant correlations between the scores in Limitations in Psychosocial Capacity and the factor scores of four test and questionnaire factors. These factor scores explained 35% of the variance of Limitations in Psychosocial Capacity. In other words, psychiatric ratings could partially be substantiated by objective, standardized data collected from the claimants by the computerized testing and questionnaires. Of note, the tests and questionnaires did not directly refer to functions relevant for the psychosocial capacity; there are for example no standardized measures for Endurance or Flexibility, which are rated in the Mini-ICF-APP.

Study limitations

The study investigated the feasibility of the DASDIM in a naturalistic setting of work disability evaluations. Due to this setting, no healthy participants were recruited as control group. This limits the direct interpretation of the described factor scores, because these scores provide parameter values relative to the study sample. Scores of 0 reflected the average of the study participants and not the average of a normative population. However, normative data were at hand on the level of each instrument’s scales and these data (and not the factor values) were also the ones provided to the medical experts (Figure S1). We might add that the PCA was not intended to replace existing test and questionnaire scales, because their mean scores can directly be compared with previous findings that used the same instrument. Instead, the revealed factors were presumed to structure the extensive information, provided by the 100+ scales, and to summarize this information.

The sample size with 150 participants was sufficient to show the feasibility of the DASDIM. With regard to the reliability of the PCA solution, a higher n would have been desirable [Citation60,Citation61], but recruiting an even larger sample of applicants proved difficult, not least because of the vulnerability of the candidates. The sample size was not sufficient to perform detailed subgroup analyses (beyond the comparison of claimants for disability insurance benefits and applicants for early retirement, of individuals with different primary ICD-F diagnoses, and claimants with different RWC levels).

The study design did also not allow making any cost-benefit analysis for the DASDIM. The usefulness of the DASDIM as perceived by the psychiatric expert was on average moderately high (seven points on a 10-point Likert scale, see Supplementary materials), but strongly varied between experts. Some of the participating experts already used psychometric instruments in their evaluations. Those experienced experts might welcome the information the DASDIM report provides more than the inexperienced ones or those who might rather be reluctant to employ such instruments. The study did not address these likewise important issues.

General discussion and conclusions

The dramatically increasing follow-up costs due to mental disorders in Europe and beyond in recent years are increasingly recognized as a key societal problem. The financial resources of social security systems are limited and it is essential to allocate these resources as efficiently and fair as possible. Since the severity of performance deficits resulting from mental disorders is of utmost importance for the award of disability grants, a reliable methodology is needed in psychiatric assessment to determine these deficits as accurately and valid as possible. Despite the importance of resource allocation to society and the affected individual, research efforts are so far limited. The low reliability in insurance medical assessments by psychiatric evaluators is a recurring complaint [Citation50–52]. In the absence of uniformly used standardized procedures, evidence-based knowledge cannot be generated, and thus psychiatric assessments are largely determined by the judgment of the individual assessors.

In the present study, we used the DASDIM in parallel to the conventional expert examination. In addition to extended basic data, essential psychological and cognitive dimensions were recorded in a standardized and objective manner. This generated data set represents an additional, supplementary source of information, largely independent of subjective assessments of the medical expert and suitable for further scientific analysis. Nevertheless, the medical expert’s competence is required to interpret this additional data and to include it in the overall assessment of the claimant’s work disability.

The results of the present study show that the use of such a platform is convenient and feasible. Moreover, they demonstrate the potential to generate normative data for the specific setting of an insurance medical evaluation, which is urgently needed, since the adoption of normative data generated in clinical settings can be misleading. The presented factors provide a methodological basis for identifying associations between master data, psychiatric-cognitive dimensions and assessors’ ratings of performance and psychosocial functioning.

Coupling with follow-up parameters and other health data could then enable a predictive model. Such a model would be essential to use resources effectively and to support the individual in the most efficient and reasonable way. Overall, in our view, there are two main benefits from the proposed methodology: first, medical experts gain an additional source of information via the recorded data set, which they can compare with their impressions from the conventional exploration. For example, the experts can identify and clarify discrepancies between statements made by the applicant and their own assessment. Second for the first time, this offers the possibility of evaluating expert reports in a meaningful way as there is a framework of objective data.

Conclusions

The incorporation of the DASDIM in work disability evaluations opens new avenues for research in insurance medicine and allows for a substantiation of RWC estimates and psychiatric ratings by objective, standardized data. This would also increase the transparency and traceability of such evaluations for all stakeholders (insurers, claimants, medical experts, expert case-coordinators, and legal practitioners).

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee Northwest/Central Switzerland approved the study on May 17, 2017 (EKNZ: 2017-00781).

Consent form

Not applicable.

Author contributions

TR wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, conducted most statistical analyses, interpreted the data, created the artwork but Figure S1, and finalized the manuscript according to the feedback of the co-authors; GD programmed and implemented the DASDIM, recruited participants, coordinated the data collection, collected data, conducted exploratory statistical pre-analyses, drafted parts of Methods, and created Figure S1; trained psychology students in applying DASDIM and trained psychiatric experts to use DASDIM and to interpret DASDIM results; GE led the study center Zurich-Winterthur, recruited participants, collected data, supervised the data collection in his study center, and contributed to the data interpretation and discussion; VH wrote the initial ethics proposal, contributed to the selection of psychometric tests, recruited participants, collected data; trained psychology students in applying DASDIM and trained psychiatric experts to use DASDIM and to interpret DASDIM results, and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript; MOP was involved in the conceptualization of the study and counseled the composition of the DASDIM, as well as statistical analyses; RDS counseled the composition of the DASDIM and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript; PC counseled the composition of the DASDIM, contributed to the discussion of the findings and to the drafting of the manuscript; BS recruited participants and was involved in the data collection; TC recruited participants and was involved in the data collection; MJ led the study center at Psychiatric University Hospital Zurich, recruited participants, and was involved in the data collection; HJ counseled the composition of the DASDIM; YB supervised the administrative processes and involved personnel at the main study center asim Basel; RM conceptualized and initiated the study, secured funding, supervised all study activities, interpreted the data and drafted parts of the discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material.docx

Download MS Word (268.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors greatly appreciate the contribution of Drs. Nathalie Franke, Melanie Hess, Kristin Rabovsky, Wolfram Brandt, Robin Halioua, Martin Eichhorn, Julian Strauss, and Marc Walther in data collection, as well as the committed involvement of Daniel Hess, Din Burazorovic, Ornella Fasolin, Manuela Frei, and Martina Apostolo in recruitment and DASDIM assessment.

Disclosure statement

All authors declared no potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data protection reasons. Coded data might be selectively available from the senior author (RM) upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AHV. Invalidenrenten der IV; 2022. p. 1–20. Available from: https://www.ahv-iv.ch/p/4.01.d

- Baumberg Geiger B, Garthwaite K, Warren J, et al. Assessing work disability for social security benefits: international models for the direct assessment of work capacity. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(24):2962–2970.

- Dell-Kuster S, Lauper S, Koehler J, et al. Assessing work ability – a cross-sectional study of interrater agreement between disability claimants, treating physicians, and medical experts. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40(5):493–501.

- Inclusion Handicap. Meldestelle zu den IV-Gutachten [Registration portal for disability evaluations]; 2021. Available from: https://www.inclusion-handicap.ch/de/themen/invalidenversicherung-%0A(iv)/meldestelle-484.html

- Marelli R. Zur Entstehung der Leitlinien im deutschsprachigen Raum und speziell in der Schweiz [On the development of the guidelines in German-speaking countries and especially in Switzerland]. Schweizerische Ärztezeitung. 2004;85:1045–1047.

- Ebner G, Colomb E, Mager R, et al. Qualitätsleitlinien für versicherungspsychiatrische Gutachten [Quality guidelines for insurance psychiatric reports]. Bern: Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie SGPP Leitlinien für die Begutachtung psychiatrischer und psychosomatischer Störungen in der Versicherungsmedizin; 2016.

- Vogel H. Qualitätssicherung der sozialmedizinischen Begutachtung [Quality assurance of socio-medical assessments]. Berlin: Deutsche Rentenversicherung; 2020.

- Hermelink M, Kocher R. Versicherungsmedizinische Qualitätssicherung in der Invalidenversicherung [Insurance medical quality assurance in disability insurance]. In: SGVP-Jahreskolloquium; 2021 Jan 29; 2021.

- Eidgenössisches Departement des Innern EDI. SuisseMED@P Reporting 2019. Bern: Eidgenössisches Departement des Innern EDI; 2020.

- Pizala H. In: Escorpizo R, Brage S, Homa D, et al., editors. Qualitative Evaluation von psychiatrischen Gutachten unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des methodischen Vorgehens der Gutachter [Qualitative evaluation of psychiatric assessments in consideration of the methodological rater’s approach]. Inaugural disserat. Basel: Faculty of Medicine, University of Basel; 2010.

- Deutsche Rentenversicherung. Leitlinien für die sozialmedizinische Begutachtung. Berlin; 2018. Available from: https://www.deutsche-rentenversicherung.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Experten/infos_fuer_aerzte/begutachtung/leitlinie_sozialmed_beurteilung_abhaengigkeitserkrankungen.pdf?__blob = publicationFile&v = 4

- AWMF. Teil I Gutachtliche Untersuchung bei psychischen und psychosomatischen Störungen. Günzburg: AWMF; 2019.

- Linden M, Baron S. Das “Mini-ICF-Rating für Psychische Störungen (Mini-ICF-APP)”. Ein Kurzinstrument zur Beurteilung von Fähigkeitsstörungen bei psychischen Erkrankungen [The “Mini-ICF Rating for Mental Disorders (Mini-ICF-APP)”. A brief instrument for the assessment of incapacity disorders in mental illness]. Rehabilitation. 2005;44(3):144–151.

- Linden M, Baron S, Muschalla B. Mini-ICF-Rating für Aktivitäts- und Partizipationsbeeinträchtigungen bei psychischen Erkrankungen [Mini-ICF rating for activity and participation impairments in mental illness – manual]. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2009.

- Ebner G. ICF und Begutachtung in der Psychiatrie [ICF and psychiatric evaluations]. Medinfo. 2018;2:16–26.

- Jeger J, Trezzini B, Schwegler U. Applying the ICF in disability evaluation: a report based on clinical experience. In: Escorpizo R, Brage S, Homa D, Stucki G, editors. Handbook of vocational rehabilitation and disability evaluation: application and implementation of the ICF. Cham: Springer; 2015. p. 397–410.

- Habermeyer B, Kaiser S, Kawohl W, et al. Assessment of incapacity to work and the Mini-ICF-APP. Neuropsychiatrie. 2017;31(4):182–186.

- Rosburg T, Kunz R, Trezzini B, et al. The assessment of capacity limitations in psychiatric work disability evaluations by the social functioning scale Mini-ICF-APP. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):480.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV R. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000.

- Guy W. Clinical global impressions. Rockville (MD): U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Public Health Service; 1976.

- Jahn T, Beitlich D, Hepp S, et al. Drei Sozialformeln zur Schätzung des (prämorbiden) Intelligenzquotienten nach Wechsler [Three social formulas for estimating the premorbid IQ according to Wechsler]. Zeitschrift für Neuropsychol. 2013;24(1):7–24.

- Zimmermann P, Fimm B. Testbatterie zur Aufmerksamkeitsprüfung (TAP). Version 2.3 [Test of attentional performance, version 2.3]. Herzogenrath: PSYTEST; 2012.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699.

- Petermann F. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – fourth edition (WAIS-IV). German version. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2012.

- Morfeld M, Kirchberger I, Bulliger M. Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand – SF-36 [Short form (36) health survey]. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2011.

- Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, et al. Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(11):815–823.

- Ilmarinen J. The Work Ability Index (WAI). Occup Med. 2006;57(2):160.

- Schaarschmidt U. AVEM: Ein Instrument zur interventionsbezogenen Diagnostik beruflichen Bewältigungsverhaltens [An instrument for the intervention-related diagnosis of professional coping behavior]. In: Arbeitskreis Klinische Psychologie in der Rehabilitation BDP, editor. Psychologische Diagnostik – Weichenstellung für den Reha-Verlauf; 2006. p. 59–82.

- von Zerssen D, Petermann F. Münchener Persönlichkeitstest (MPT) [Munich Personality Inventory]. Bern: Huber; 2012.

- Ben-Porath Y, Tellegen A. Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory – restructured form: manual for administration, scoring, and interpretation. Minnesota: University of Minnesota; 2008.

- Engel R. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory – 2 Restructured Form™. German Version. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2019.

- Dohrenbusch R, Pielsticker A. Psychologische Begutachtung von Personen mit chronischen Schmerzen [Psychological assessment of people with chronic pain]. In: Kröner-Herwig B, Frettlöh J, Klinger R, et al., editors. Schmerzpsychotherapie. Heidelberg: Springer US; 2017. p. 251–273.

- Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna; 2020.

- Bartlett M. A note on the multiplying factors for various chi square approximation. J R Stat Soc. 1954;16:296–298.

- Kaiser H. A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika. 1970;35(4):401–415.

- Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav Res. 1966;1(2):245–276.

- Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. MissForest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(1):112–118.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press; 1969.

- Richardson JTE. Measures of effect size. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 1996;28(1):12–22.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Academic Press; 1988.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276.

- Sellbom M, Bagby RM, Kushner S, et al. Diagnostic construct validity of MMPI-2 restructured form (MMPI-2-RF) scale scores. Assessment. 2012;19(2):176–186.

- Lee TTC, Graham JR, Arbisi PA. The utility of MMPI-2-RF Scale Scores in the differential diagnosis of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. J Pers Assess. 2018;100(3):305–312.

- Posner MI. Measuring alertness. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:193–199.

- Baddeley A. Working memory: theories, models, and controversies. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:1–29.

- Richardson JTE. Measures of short-term memory: a historical review. Cortex. 2007;43(5):635–650.