Abstract

Purpose

Functional neurological disorder (FND) causes many neurological symptoms and significant disability. It is often misunderstood by medical professionals and the public meaning stigma is regularly reported. The aim of this review was to synthesise the qualitative findings in the literature to develop a more in-depth understanding of how people with FND experience stigma to inform future interventions.

Method

This review used a meta-ethnography approach. Five databases were searched (PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE) in February 2021 and updated in July 2022 for qualitative papers in FND. Included papers were critically assessed using the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) checklist. Data were analysed and synthesised utilising meta-ethnography.

Results and conclusion

Sixteen papers were included in the final synthesis. Four major themes emerged: stigmatized by delegitimization; stigmatized by social exclusion and rejection; coping with stigma; and stigma and identity. The results identified negative, stigmatizing attitudes towards people experiencing FND symptoms in a variety of contexts including healthcare and other social institutions. The effects of stigma led to further exclusion for participants and appeared to trigger coping styles that led to additional difficulty. Stigma is a key part of the illness experience of FND and needs to be addressed.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Functional neurological disorders can cause a significant degree of disability for those individuals who experience them.

This experience appears to be compounded by stigma these people encounter as a result of their illness in their day-to-day lives as well as in their contact with institutions including education, workplaces, and healthcare.

A potential strategy to reduce the impact of stigma is through raising awareness of the reality of this condition which may be achieved through education targeted towards healthcare providers.

Introduction

Functional neurological disorder (FND) describes the experience of a range of symptoms including problems with movement, altered awareness, which can resemble seizures, and changes in sensation [Citation1]. The symptoms of FND can resemble neurological conditions, such as epilepsy, stroke, or Parkinson’s but without similarly identifiable biomarkers [Citation1]. FND has an estimated incidence rate of 4–12 per 100 000 per annum worldwide [Citation2] and a large-scale study in Scotland found that FND was a frequently diagnosed condition following first-time presentations to outpatient neurology clinics [Citation3].

In addition to the primary symptoms of FND, people with this diagnosis experience a range of mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression [Citation2]; with these being more common than for individuals with some other neurological conditions [Citation4]. As a result of their symptoms people with FND can experience a significant level of disability which can lead to a range of psychosocial difficulties within their family, work, and social lives [Citation5]. For example, one study reported that employment levels fell from 87.5% before experiencing symptoms to 24.5% post-diagnosis [Citation6].

Recent explanations of FND emphasise the role of biological and psychological factors in the development and maintenance of symptoms. Neurobiological investigations have found that while no specific brain lesion or abnormality can explain FND, differences in activation and connectivity in specific brain areas have been observed [Citation7]. For example, hypoactivation has been observed in the motor cortex of those with functional tremor [Citation8] and strong functional connectivity has been observed between areas associated with emotion, movement, and executive function in those experiencing functional seizures (FS) [Citation9].

Modern psychodynamic explanations posit the role of FND symptoms in the unconscious management of feelings, interactions, or memories that are unbearable in some way [Citation10]. However, this explanation is contested due to the lack of a clear traumatic event in many cases of FND [Citation11]. Further psychological explanations focus on links between the attentional system, illness beliefs, and FND symptoms [Citation12]. Beyond this, cognitive explanations highlight schemas or frames of understanding that underpin FND and result in symptoms being activated [Citation13]. Biopsychosocial explanations of illness seek to combine these various understandings into a meaningful whole, integrating the impact of each factor on the development and maintenance of the condition [Citation14]. Models encompassing cognitive, attentional, and affective processes alongside social and biological vulnerabilities [Citation15] facilitate the integration of different understandings of FND and allow for the heterogeneity that exists amongst those who develop these symptoms.

Due to the lack of specific biomarkers of disease, stigma is a common experience for those with FND [Citation16]. Current understandings of stigma have been heavily influenced by Goffman [Citation17] who defined stigma as a social construct consisting of a devaluation of social identity which prevents individuals from attaining full social acceptance. Link and Phelan [Citation18] further emphasised the impact that stigma has in highlighting the difference between people or groups. This fosters a “them” and “us” narrative which ultimately leads to discrimination, power imbalance, and loss of status for those affected.

An international survey in 2020 of people with FND found that 81% of participants reported being treated poorly due to stigma related to their diagnosis [Citation19] with 61% experiencing trauma as a result of their illness journey. Furthermore, 61.8% believed that having an FND diagnosis had affected the healthcare provided in the past and 64% were concerned about how it would affect future healthcare. Similarly in a UK survey of patients with one FND diagnosis, functional seizures (FS), 82.7% had experienced perceived stigma [Citation4] and those with FS were 42% more likely to experience perceived stigma than individuals with epilepsy. Quantitative research has also highlighted that stigma exacerbates difficulties with the quality of life for those experiencing FND symptoms [Citation20].

Research with healthcare professionals has highlighted stigmatizing beliefs towards people experiencing FND [Citation21] including beliefs that those with FND symptoms are “faking” their illness to benefit from secondary gain [Citation22]. A synthesis of studies on the views of healthcare providers working with FND highlights a vicious circle in which managing the complexity of the presentation of people with FND leads to them “passing the buck” [Citation20, p. 7] onto another discipline without providing adequate support, thus further contributing to stigma.

Qualitative research methodology can amplify marginalised voices, and so have a humanizing effect [Citation23], giving service users an active voice in a sphere that affects them greatly. Furthermore, reviews of qualitative research play an important role in healthcare and serve functions, such as consolidating research on the lived experience of individuals and supporting practitioners [Citation24] as well as influencing policy [Citation25]. While the experience of stigma has been noted repeatedly in research to date, it has yet to be explored in detail as a central component in its own right.

Consequently, the aim of the present review is to examine the unique experiences of stigma described by individuals with FND to gain a greater understanding of the impact of stigma on their experience. It is anticipated that this will inform the provision of higher quality care and increased understanding with the ultimate aim of improving outcomes for this group. Therefore, the review proceeded with the broad research question; how do people with FND experience stigma?

Methods

The method adopted for this review was Noblit and Hare’s [Citation26] seven-step method of meta-ethnography. A meta-ethnography approach allowed for information pertaining to stigma from previous studies to be synthesised and interpreted to provide a fuller understanding of this experience with a view to developing results that will inform practice [Citation27].

Database searches

In consultation with two subject librarians, five databases were chosen for the search: PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE. These databases were chosen for their focus on health sciences research, psychology, healthcare, and medicine. The search strategy sought to identify all of the qualitative papers available on FND. In doing so, it adopted qualitative research and FND as two core concepts. Keywords and synonyms of FND combined with qualitative research terms were combined in the search. The specific FND terms were informed by previous reviews in the area [Citation5,Citation15,Citation28]. See Appendix 1 for a sample of the search run in PsycINFO. For the remaining databases, this was translated to use their specific subject headings and syntax.

Searches were initially conducted in February 2021 and were updated in July 2022. A search strategy test was conducted whereby five known key papers relevant to the review were identified. All five papers were present in the search results indicating that the search strategy was effective in finding papers relevant to the review.

Inclusion criteria and systematic search

Inclusion criteria for the review were: qualitative methodology used that involved participants’ descriptions of their lived experience; focused on the perspective of individuals with an FND diagnosis; peer-reviewed and available in English. Furthermore, papers must have reported a theme or similar portion of text relevant to stigma. For the purpose of this review, any theme that detailed participants being treated differently from others, facing discrimination, or being treated in a way which prevented them from attaining full social acceptance due to their illness was deemed relevant. For instance, a theme or subtheme which explicitly mentioned stigma or described an experience of this nature was considered to meet the inclusion criteria.

Following the systematic search, papers were entered into a referencing management system and duplicates were removed. The title and abstract of these papers were screened for relevance including the methodology and presence of the topics of interest. The full-text of the remaining papers were assessed for eligibility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and finally, reference lists of the full-text papers were also searched for additional relevant papers. The systematic search and screening were conducted by the first author, at the time a trainee clinical psychologist, supported by a research supervisor based on a doctoral training programme in clinical psychology and a consultant clinical neuropsychologist. Supervision was used throughout all phases of the study to increase reflexivity.

Data analysis

Following Noblit and Hare’s [Citation26] seven steps for meta-ethnography, the first two steps of “getting started” and “deciding what is relevant to the initial interest” for meta-ethnography are detailed in the introduction to the topic and the search strategy. Following this, the papers were read and coded line by line, notes were made of key concepts completing the “reading the studies” phase. This was done manually, papers were printed and annotated. Then, in the “determining how the studies are related” phase, the codes were compared to identify relationships between the concepts covered in each study. For instance, codes, such as “not believed” and “blamed” were identified in this step. The “translating the studies into one another” phase involved translating the codes and themes together to develop an understanding of stigma. As themes began to emerge, quotations from individual papers were compiled on a spreadsheet to be able to see the supporting data as a whole and to be able to cross-check meanings back with the original papers. “Synthesising translations” brought the translations together into themes that represented common translations and new interpretations. Finally, the synthesis was expressed through the writing of this paper.

Quality rating system

Included papers were screened using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tool [Citation29]. The first two questions act as screening questions to determine whether proceeding with the appraisal is worthwhile. The remaining eight questions were used to rate the quality of the papers used in the review. In doing so, the three-point rating system advocated by Duggleby et al. [Citation30] was utilized. Scores ranged from a weak score (one point) for papers that did not explain or justify the issue being examined by the CASP question, a moderate score (two points) where the issue was mentioned but not expanded upon, or a strong score (three points) where the issue was both justified and sufficiently expanded upon. The scores from the eight items were added to give a total score for each paper with a maximum possible score of 24. Using this system, the first author and a colleague reviewed the papers independently and reached a consensus on scores afterwards. Where consensus was not possible, the first author had the final say on the score applied. While CASP scores were not used as inclusion or exclusion criteria, following the analysis the sources of each theme were checked to ensure that the higher quality papers were well-represented in the results and no theme depended solely on the weaker papers.

Results

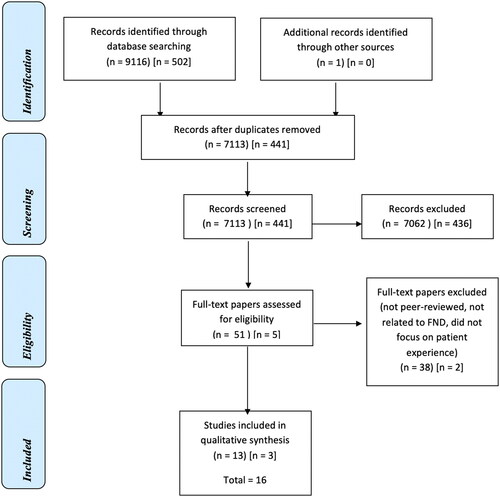

A total of 9116 papers were identified from the databases searched. After duplicates were removed, 7114 remained. Title and abstract screening led to 7063 papers being removed and 51 full-text papers were assessed for eligibility. Reference lists of these 51 papers were screened and one additional relevant paper was identified and assessed for eligibility. At this stage, 40 papers were excluded as they did not meet inclusion criteria. This left 16 papers remaining. While all 16 papers contained a minimum of one subtheme describing stigma or stigmatising encounters, just one explicitly explored an aspect of stigma throughout the paper [Citation31]. See for a PRISMA diagram of the screening process and for the details of the papers included in the review.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram. Figures in parentheses indicate the initial search conducted in February 2021. Figures in square brackets represent those conducted in July 2022.

Table 1. Papers Included in the review.

The review incorporated 16 qualitative papers. On the quality rating system described above, the papers achieved ratings that ranged from 16 to 22. These studies included a total of 277 participants with an FND diagnosis. Geographically, samples were recruited from the UK for eight papers, Norway for three papers, and one each from India, the U.S.A., South Africa, and Argentina. A further paper [Citation41] recruited internationally with the majority of participants living in the UK or North America. In terms of gender, where reported there was a majority of over 80% female participants across all of the studies. This is consistent with the epidemiological profile of FND [Citation6].

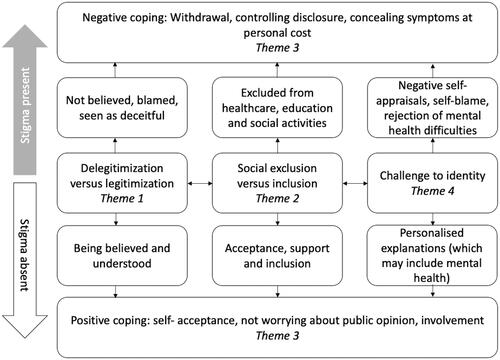

The review identified four themes through which the synthesis of these papers can be expressed. These were: Stigmatized by delegitimization; Stigmatized by social exclusion and rejection; Coping with stigma; and Stigma and identity.

provides an example of how the themes identified in this review are described as impacting upon the experience of those with FND symptoms. The impact of each of the themes being dependent on whether stigma is present (top part of diagram, as indicated by grey arrow) or absent (lower part of diagram, as indicated by white arrow). The majority of the experiences are represented by the top part of the diagram, but the lower part indicates what can happen when stigma is absent and support is present. When stigma is present the experiences of delegitimization and exclusion, coupled with self-beliefs and beliefs about mental health lead to unhelpful ways of coping. However, when experiences are legitimised, people are included and explanations of symptoms are personalised, this leads to more positive coping. More details about each of the themes are given below.

Figure 2. Diagrammatic representation of the themes.

Theme 1. Stigmatized by delegitimization

This theme reflects the experience of individuals across the studies whereby they were treated with less legitimacy than those with other illnesses and represents external stigma towards the individuals with FND.

The lived experience of delegitimization for many came in the form of not being believed [Citation29,Citation31–45], for example: “I was pretty much told that my condition didn’t really exist and that I was just hysterical and an attention seeker” [Citation41, p. 7]. The lack of belief in the experience of participants’ symptoms was frequently accompanied by a level of judgement “[they] told me I am going crazy and I have conscious control over everything and nothing is wrong I am just lazy and go to the hospital frequently because I have nothing better to do [Citation41, p. 8].” For many participants the experience of not being believed was extended to situations where it was implied that they were feigning their symptoms [Citation29,Citation31–33,Citation39,Citation41,Citation43,Citation45], encountering attitudes, such as “either you are making it up or it isn’t a real condition [Citation40, p. 88].”

Alongside disbelief, a degree of blame was present [Citation32,Citation34,Citation37,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44]. It appeared that where the people and institutions in the lives of participants did not understand the condition, they blamed the person experiencing FND. At times it appeared that where a system, such as a family, healthcare, or the workplace could not account for the experience of a person with FND, it led to that system rejecting the idea that the individual could possibly have that experience “Well none of it makes sense so you can’t be experiencing all these [Citation23, p. 9].”

Interactions with healthcare services served as a location for many delegitimizing experiences [Citation31–35,Citation37–41,Citation44,Citation45]. Participants spoke about their journeys towards a diagnosis which often took a significant amount of time [Citation32,Citation37–41,Citation44,Citation45] and then even when a diagnosis was given, participants felt that medical professionals saw their condition as less valid than one with an identifiable organic cause. Experiences of delegitimization were also experienced beyond healthcare and present throughout the lives of the participants. Individuals described similar attitudes in work [Citation31,Citation32] and in educational settings; “[a teacher] said that I played her just to get out of having a test and I faked having a fit [Citation35, p. 132].”

Other participants experienced direct physical harm as a result of their FND diagnosis [Citation38,Citation41]. Participants spoke of dangerous situations where healthcare workers sought to prove that the condition was being feigned in some way:

[…] I was very woozy and didn’t understand what was happening. My body started to shake, my eyes were open so I was clearly awake, the nurse went to do the sternum rub and instead punched my collar bone and started to rub her knuckles hard on that, she then pushed the wheelchair back into the wall and my head hit. She […] said that I was taking up everyone’s time and I was wasting the NHS resources and money [Citation38, p. 9, edited to abbreviate quote].

Such instances appeared to indicate a breach of ethical practice and displayed how an experience of social stigma within an institution could manifest in direct physical harm. Indeed, situations, where medical professionals appeared to act in these ways, seemed to be underpinned by a lack of understanding, for example presuming the patient was deceitful.

On the other hand, there were less frequent occasions where individuals had a more positive experience [Citation32,Citation34,Citation37,Citation38,Citation44,Citation45]. Where a sense of legitimacy was present, this changed the nature of interactions for the better. For instance, participants feeling believed and accepted by the professionals that they were encountering had a range of positive implications, such as “I’m thinking, ‘yes! yes! somebody believes me.’ It just made me feel … a genuine person [Citation42, p. 511].” These examples appeared to be rare moments of legitimacy and understanding in a process where the predominant experience was one of being dismissed and delegitimized. For many participants, it appeared that the experience of legitimacy was more frequent in closer personal relationships than in contact with professionals and institutions, as the authors commented: “At school and in working life, the participants said that they felt more respected and better understood by peers and friends than by teachers and employers [Citation35, p. 25].”

Theme 2. Stigmatized by social exclusion and rejection

This theme relates to the social cost of stigma for participants, including exclusion and rejection, and the impact of this external stigma on the public and private lives of those affected.

A loss of status or damage to individuals’ social role was a consequence of stigma [Citation31–33,Citation35,Citation38,Citation41]. Participants spoke about losing their independence, friends, and education [Citation35]. While some participants spoke of the isolation experienced as they missed out on social relationships [Citation44], bullying [Citation43], a rejection from social institutions, such as healthcare [Citation31–35,Citation37–41,Citation44,Citation45], work [Citation31,Citation32] and education [Citation40] was central to this experience. Other participants described a sense of subtle exclusion from normal activity whereby they were cushioned from harm to an extent but ultimately treated differently from their peers; “At school they still treat me like a little kid as well. They say you can’t do this, you’ve got to be careful because you’ll over exert yourself [Citation35, p. 130].”

For many, the social cost of stigma came in the form of being abandoned by healthcare services [Citation31–35,Citation37–41,Citation44,Citation45] “I was discharged again without any explanation and just left [Citation42, p. 511].” This left individuals feeling frustrated with services “refer me on! Do something. Don’t just allow me to stay at home and do nothing [Citation37, p. 2046].” These difficulties in finding appropriate care were frequent with participants feeling that they were alone in managing the condition, and that support was not available to them [Citation40]. This feeling was very much present in the journey towards a diagnosis that participants described as long and arduous [Citation32,Citation37–41,Citation44,Citation45]. Furthermore, a secondary cost of stigma was identified in that healthcare services often paid less attention to other non-FND health concerns raised by participants meaning that participants’ other health concerns were ignored [Citation41, p. 7].

Where participants encountered social systems that were supportive and inclusive, this appeared to act in the opposite fashion, helping them to adjust to their symptoms and diagnosis [Citation31,Citation33,Citation34,Citation41]. The support of friends and family counteracted some of the effects of stigma in some cases “And then all the caring and love that, around it… It helps you. So don’t push people away … Let people help you, to care and love you [Citation38].”

Theme 3. Coping with stigma

This theme is related to the personal costs of stigma and represents individuals’ efforts to cope with external stigma. Often, participants were presented with a position where they had to manage stigma in addition to their illness. In these situations, participants seemed to respond by seeking to protect themselves against further harm. In some instances, these strategies led to further harm to participants.

To manage the stigma that they encountered, some participants sought to carry on as normal, as if they did not have FND symptoms [Citation32,Citation34,Citation36]. In doing so, participants wore themselves out “I felt exhausted from trying to continue to be normal [Citation23, p. 9].” Similarly, controlling the information available to others about their FND symptoms was a key strategy.

“I was furious if they (the teachers) said something while I was away… (…) … I'll sue them for breach of confidentiality. I do not want to tell the teachers this … (…) Really, I want to say that they diagnosed epilepsy. [Citation34, p. 25]”

Telling people that they had epilepsy was a common strategy as this was more readily understood and felt less stigmatising for these participants [Citation31,Citation33,Citation35].

In addition to the imposed isolation in theme 2, many participants resorted to self-isolation to cope with the stigma that they encountered [Citation31,Citation32,Citation37,Citation38,Citation41,Citation44]. It appeared that individuals expected a degree of stigma in daily life and as a result avoided normal activity “I went out less… I just didn’t want to do anything that was going to embarrass me [Citation23, p. 9].” In doing so, participants described withdrawing from social relationships [Citation23] and work [Citation31]. This avoidance of situations extended to healthcare for fear of further adverse experiences and judgement;

“I felt deeply misunderstood and offended and it has affected me hugely […] I now have difficulty trusting healthcare professionals […] I fear hospitals, almost to a phobic extent […] It has affected me massively […] when you don’t trust that you’ll be treated appropriately by others when completely unable to explain or defend yourself, it’s terrifying […] I don’t think health professionals realise the potential consequences of their actions [Citation41, p. 10].”

Through this strategy, individuals often appeared to experience compounded difficulties. For example, they did not receive appropriate healthcare as they did not seek it out for fear of encountering further stigma and judgement. Furthermore, this approach resulted in participants experiencing further exclusion “you hear less and less from people [Citation37, p. 2045]” and it reduced the potential for participants to experience positive validation [Citation31].

Underlying some of these actions were a variety of fears, such as a fear of being judged [Citation31–35,Citation39–42,Citation44,Citation45] “if someone saw me what would they be thinking [Citation23, p. 9]” and participants spoke widely of feeling that others were judging them in some way “I worry that they will think lots of negative things. They’ll think I’m a complete lunatic [Citation34, p. 25].” It appeared that for some, the experience of stigma led to expectation of further judgement from others in many participants “They surely think that I am faking the seizures now as there is no organic reason for them [Citation33, p. 42].”

Similar to the previous themes, participants described infrequent moments where their symptoms were seen as legitimate and they were treated respect [Citation29,Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation38,Citation44,Citation45]. This in turn led them to feel that they could participate as normal in society and resume their normal activities in spite of both their symptoms and the associated stigma.

“I know I have seizures, and I know that I have problems. It has taken me a long time … But I'm happy that I have reached where I am today. When I get seizures in public…. I care… not. What happens, happens [Citation32, p. 26].”

Where this was the case, individuals appeared to arrive at this opinion after a significant period of adjustment [Citation34, p. 42].

Theme 4. Stigma and identity

This theme describes interactions that participants found particularly stigmatizing, where they were confronted with opinions and explanations for their difficulties that contrasted greatly with their view of themselves and the world. However, this theme also represents a resistance to internalising stigma where it clashed with individuals’ core beliefs about themselves and others.

Many of the stigmatizing responses towards people experiencing FND appeared to cause particular discomfort and pain where they led to a perceived threat to the identity of the individual. For instance, where they were not believed as described above, participants highlighted the feeling that they had been judged as somebody who would set out to deceive others [Citation32,Citation35,Citation37,Citation40–42,Citation44]. This was often accompanied by some implied judgement that they were in control of their symptoms or chose to have them. In turn, this led participants to feel that their identity was under attack, e.g., “I do not want people to think I’m a bad person because I suffer from seizures [Citation34, p. 110].”

Another significant threat to participants’ identity presented through the internalisation of blame [Citation31–35,Citation37–41]: with participants describing themselves as a “loser, just pull yourself together” while feeling “weak,” “useless,” “pathetic,” and a “waste of space and money” [Citation40, p. 87]. While the blame identified in descriptions of delegitimization above was external and directed towards individuals, here the blame was internalised with participants blaming themselves for their difficulties and the impact that they have had on others “I feel guilty, I feel like, why do I have this? I made everyone feel angry and upset and I'm making the family fall apart [Citation35, p. 130].” Statements, such as this appeared to show that participants felt a degree of self-blame for stress in their family caused by their symptoms and stigmatizing understandings about the degree of control that they held over them. Additionally, the experience of external stigma for some participants led to an internalisation of stigmatising ideas that their symptoms may not be real “Am I actually getting these symptoms or is it all in the head? [Citation23, p. 9].” This sense of internalised blame for their difficulties often led to intense emotional experiences, such as anger “I’d get right frustrated, start crying… chuck things and get right angry with myself [Citation23, p. 8].”

Across the studies, psychological explanations of FND appeared closely linked with notions of identity for individuals in the studies. For some, psychological explanations added to the sense of delegitimization discussed above (theme 1) “Because that’s what it feels like, psychological feels like it should mean, it’s literally you are making it up. It’s all in your head, there’s nothing wrong with you at all [Citation35, p. 2046].” However, for many the description of experiencing a mental illness presented as a greater threat to their identity [Citation31–34,Citation37–39,Citation41,Citation45]. For example, a key concern for many individuals covered by the studies in this review related to being diagnosed with a mental health issue [Citation31–34,Citation37–39,Citation45]. Some participants completely rejected the idea of experiencing a mental health difficulty, seeing it as abnormal in some way, and expressed that such an explanation was a challenge to how they viewed themselves “I am normal and don’t have any mental health issues [Citation40, p. 88].” Participants felt misunderstood when referred to psychology or psychiatry for support “I can’t see how talking to somebody is going to fix it [Citation42, p. 510]”

Some of the negative perspectives towards psychological explanations for FND came through healthcare interactions whereby they had been treated well until they had been diagnosed with a functional disorder implying psychological cause. As one author described;

Negative attitudes of [healthcare practitioners](HCPs) towards what they perceived as psychogenic problems (i.e., having a psychological basis), may have played some role in the participants’ dissatisfaction with receiving psychological explanations for their problem. It was common for participants to describe experiences of poor treatment and negative interactions with HCPs only after a psychogenic diagnosis was made [Citation35, p. 2046].

This response to psychological explanations of their experience was not universal to participants across the studies. Contrasting with the threats to identity that some participants experienced, others highlighted participants highlighted the benefits of viewing their condition from this perspective [Citation32,Citation34,Citation37,Citation42,Citation44]. For example, providing psychological explanations that recognised the interactions between life events and physical responses, such as stress and the subsequent impact on FND symptoms appeared more acceptable to some with FND [Citation34]. Indeed, explanations that accounted for the individual experience and identity of the person experiencing FND appeared to be more readily acceptable. It appeared that these explanations recognised the complexity that the participants faced and sought to understand that as opposed to informing them that they are experiencing psychological difficulty that they somehow should have control over [Citation32,Citation34,Citation37,Citation42,Citation44].

Discussion

This systematic review provides the first synthesis of studies exploring the experience of stigma for people with FND. In doing so, it adds to the growing body of literature that overtly recognises stigma towards people with FND as a central part of their experience [Citation4,Citation20]. The results of this review identified that stigma is experienced in all aspects of their lives from their own psychological experience to their interactions with wider society [Citation16].

Returning to Goffman’s [Citation17] definition of stigma concerning the devaluation of social identity, the descriptions here show that people with an FND diagnosis experience this on a large scale. The theme of delegitimization described here represents a sense of being treated as “lesser than” or “less valid” than other people. Through this, a sense of “othering” creates distance and presents those with FND with a somehow less valid social identity, the effects of which are clearly visible throughout the review. On top of this enacted or internal stigma [Citation46], individuals described the phenomenon of internalised stigma whereby they have taken this message delivered by society and applied it to themselves, visible in participants’ descriptions of coping and identity. Research into mental health stigma [Citation47] has highlighted the additional impact of internalised stigma on symptom severity and treatment adherence, signalling the potential additional difficulty that this causes for those with FND symptoms. Additionally, a central tenet of the theory of stigma centres around a power imbalance. Indeed, Link and Phelan’s [Citation18] theory on stigma in healthcare notes a power imbalance as a pillar without which stigma cannot operate. As can be seen in the experience of these participants’ descriptions of delegitimization and social exclusion, stigma has arisen in traditional institutions where a power imbalance often exists—school, work, and healthcare. Conversely when experiences are validated, individuals experience relief and acceptance and indeed such validation can improve future outcomes [Citation48].

Furthermore, the results of this review show how participants experience compounding difficulties as a result of the stigma they face. Link and Phelan [Citation18] highlight how stigmatising experiences are likely to affect life chances through increased barriers to accessing appropriate education, employment, and healthcare. Indeed, difficulty accessing these have been noted in the FND population [Citation6] and are described by the participants in this review, with stigma compounding the barriers due to disability. This finding reflects quantitative research on this topic which also identified the compounding effect of stigma on the FND population, highlighting an inverse relationship between stigma and health-related quality of life for this group [Citation20].

Naturally, people make efforts to manage stigma, such as carrying on regardless of the difficulties that they face or carefully managing the perceptions of others while coping with their symptoms. This additional stress may act as an exacerbating factor making the original difficulties faced worse [Citation18], another mechanism through which stigma exacerbates the difficulties faced by those experiencing FND. Indeed, this effect of stigma leading to psychological distress and causing additional damage through the erosion of social support has been noted in the general population [Citation49], whereas high levels of social support have been shown to buffer the effect of external stigma in a variety of health conditions [Citation47,Citation50,Citation51].

Considering the delegitimization that participants described in this review, a key factor underpinning this experience appears to be the view that FND is less valid due to the lack of established biomarkers for its diagnosis. The idea that healthcare has a positive bias towards conditions that can be observed and counted has been commented on in healthcare literature [Citation52] identifying neoliberal ideals in health. This perspective encourages values in healthcare and society that promote an attitude of personal responsibility. This viewpoint disregards difficulties that cannot be clearly observed as a “disease of the will” [Citation53] creating a belief that those who suffer from them have a degree of control over them. This preference for the physical and observable can be seen on a wider scale in the funding of services. For example, mental health services faced more cuts during the austerity era in the UK than their physical counterparts [Citation54]. Indeed, the feelings of being abandoned expressed by individuals in this review may relate to this lack of recognition of and subsequent provision for an illness that has not historically been socially accepted. For example, participants in this review were noted in the change in healthcare professional’s attitudes towards them when they were deemed to be experiencing a mental health difficulty and in the views of participants not wishing to be viewed as being part of this stigmatized group.

The above point links the results of this study with the experience of stigma faced more widely by people experiencing medically unexplained symptoms (MUS). Whilst MUS are more common than FND, a similar stigma towards people experiencing them exists due to the lack of a medical explanation [Citation55]. Similar to FND, those with MUS have reported greater levels of perceived stigma compared to those with the corresponding medically explained diagnosis [Citation56] which has been shown to have a negative impact on patient outcomes [Citation57]. However, the experience of FND is distinct from some MUS in the visibility of symptoms to others, which can attract a greater degree of external stigma.

Clinical implications

This review identified stigmatizing interactions with healthcare professionals. People with FND reported limiting their contact with services as a result. It has been well-documented that people experiencing FND often do not attend follow-up appointments, particularly with psychiatric services [Citation56]. In these cases, addressing stigma would likely improve trust between services and those with FND and increase attendance at treatment. The results in this study compared with a review of practitioner experiences [Citation21]. In the present review, participants reported feeling misunderstood or dismissed leading to stigmatizing experiences. Interestingly, when practitioners spoke of their experiences, they reflected similar themes, reporting feelings of being out of their depth, and not understanding the presentation of FND [Citation25]. The review of healthcare professionals identified the idea of a vicious cycle whereby individuals diagnosed with FND were passed from one service to the next without receiving an appropriate service. This closely matches participants’ descriptions of being abandoned by healthcare services. Thus, it may be that this lack of understanding or ability to provide support for FND patients presents practitioners with a degree of symbolic threat (a desire to understand and treat the condition, but feeling unable to do so) which leads to a stigmatizing response. Indeed, a perceived threat of change has been identified as a key process in the development of stigmatizing beliefs [Citation57]. Therefore, increasing awareness and knowledge of FND is crucial in combatting stigma. Seeking to achieve this, recent research [Citation58] has identified positive changes to practitioners’ views of FND following a training programme delivered over 6 h-long sessions based on questions commonly asked by people with an FND diagnosis, connecting these with perspectives from modern neuroscience and skills in empathic communication. While little exists in the way of national guidance for the management of FND, a quality standard issued by the UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) [Citation59] recommends that those with FND can access support to understand and manage their symptoms through standard rather than specialist care. A lack of understanding of the condition may be a central barrier to meeting this standard. Evidently, further training and education for healthcare practitioners are required to reduce the stigma towards FND. Education informed by people with FND may be a positive step in this regard.

Furthermore, for some people with an FND diagnosis, a coping style characterised by avoidance is core to their experience [Citation28]. Therefore, for this group encountering the attitudes outlined in themes 1 (delegitimization) and 2 (exclusion and rejection) may compound this further, leading to the self-isolation and avoidance of services seen in theme 3. Due to the potential for an interaction between stigma and such coping styles to compound the difficulties of those experiencing FND, there is a clear clinical imperative to develop an early understanding of patient difficulties to support their adjustment and to prevent future disengagement due to stigma.

The findings in this study are consistent with those frequently reported in studies on perceptions of people who experience mental health difficulties [Citation60]. Participants in this review rejected the idea of experiencing a mental health difficulty, perhaps recognising the stigma towards mental health difficulties that exist in society and do not wish to join this stigmatized group in the explanation of their own difficulties. However, it has widely been acknowledged that psychological factors can play an important role in the development, and/or maintenance, and indeed the treatment of FND for many [Citation13]. Therefore, this raises the question: how can people with an FND diagnosis access explanations for their condition that incorporate important psychological factors without the associated stigma and threats to their identity? Some hints are to be found in the responses from participants in this review who identify the utility of explanations of the condition that connect with their unique experience and incorporate biological, psychological, and social factors as has been advocated elsewhere [Citation15] and may include psychological formulation [Citation14]. Further research [Citation61] has identified that the manner in which the diagnosis is explored can have an impact on how people adjust to the condition which in turn affects their prognosis. While there is evidence that psychological factors can often play a central role in understanding FND [Citation13], this review highlights the need to provide psychologically informed explanations in a way that does not result in further stigma.

Limitations

As noted in the results section, of the studies published on this topic, a large majority came from Western countries. Thus, the review was limited to the experience in these countries. In addition, all of the research that makes up the review has been led by clinicians and academics working in the area of FND research or clinical practice, as has this review. By its very nature, qualitative research involves a level of active participation and interpretation on the researchers’ part. As a result, despite their focus on the experience of individuals with FND, in the process of research, this has been filtered through the perspectives of researchers and clinicians who form part of the institutions through which stigma towards this population has been perpetuated. In future research, it may be beneficial to seek greater involvement from those affected by the issues covered in this review in the process of design, and analysis of research in this area.

Future research

Despite the descriptions of stigma in the papers in this review, only one had an explicit focus on stigma. Therefore, further qualitative research into the stigma experienced by this group is warranted. Furthermore, given the impact that stigma has on the lives of individuals affected by it, further research is required in this field to address stigma towards people with FND. Research investigating the efficacy of initiatives designed to reduce stigma would be useful to tackle this problem in healthcare settings and on a wider social scale.

Conclusion

Stigma is a pervasive experience for people with FND, who experience discrimination and delegitimization in a variety of contexts, particularly in healthcare. The effects of stigma lead to exclusion, compounding barriers already faced due to the disability, and can trigger coping strategies which are an additional stressor or cause further isolation. Experiences can challenge individuals’ beliefs about themselves and the world. Education is urgently needed so that stigma towards this group is addressed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Miss Janeen Kirwan who assisted in the quality review of the papers and Subject Librarians Tanya Williamson and John Barbrook for their help in planning the searches.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2023.2170107).

References

- Stone J, Burton C, Carson A. Recognising and explaining functional neurological disorder. BMJ. 2020;371:m3745.

- Carson A, Lehn A. Chapter 5 – epidemiology. In: Hallett M, Stone J, Carson A, editors. Handbook of clinical neurology. Amsterdam (Netherlands): Elsevier; 2016. p. 47–60.

- Stone J, Carson A, Duncan R, et al. Who is referred to neurology clinics?—The diagnoses made in 3781 new patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112(9):747–751.

- Rawlings GH, Brown I, Reuber M. Deconstructing stigma in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: an exploratory study. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;74:167–172.

- Rawlings GH, Reuber M. What patients say about living with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a systematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Seizure. 2016;41:100–111.

- O'Connell N, Nicholson TR, Wessely S, et al. Characteristics of patients with motor functional neurological disorder in a large UK mental health service: a case–control study. Psychol Med. 2020;50(3):446–455.

- Espay AJ, Aybek S, Carson A, et al. Current concepts in diagnosis and treatment of functional neurological disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1132–1141.

- Voon V, Brezing C, Gallea C, et al. Emotional stimuli and motor conversion disorder. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 5):1526–1536.

- van der Kruijs SJM, Bodde NMG, Vaessen MJ, et al. Functional connectivity of dissociation in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(3):239–247.

- Carson A, Ludwig L, Welch K. Psychologic theories in functional neurologic disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;139:105–120.

- Ludwig L, Pasman JA, Nicholson T, et al. Stressful life events and maltreatment in conversion (functional neurological) disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(4):307–320.

- Edwards MJ, Adams RA, Brown H, et al. A bayesian account of ‘hysteria’. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 11):3495–3512.

- Brown RJ, Reuber M. Towards an integrative theory of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES). Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;47:55–70.

- MacGillivray L, Lidstone SC. The biopsychosocial formulation for functional movement disorder, in functional movement disorder. Cham (Switzerland): Springer; 2022. p. 27–37.

- Pick S, Anderson DG, Asadi-Pooya AA, et al. Outcome measurement in functional neurological disorder: a systematic review and recommendations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(6):638–649.

- MacDuffie KE, Grubbs L, Best T, et al. Stigma and functional neurological disorder: a research agenda targeting the clinical encounter. CNS Spectr. 2021;26(6):587–592.

- Goffman E. Stigma and social identity. In: Understanding deviance: connecting classical and contemporary perspectives. Vol. 256. New York (NY): Routledge; 1963. p. 265.

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Stigma and its public health implications. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):528–529.

- FNDHope. FNDHope Stigma Study; 2020 [cited 2021 Feb 14]. Available from: https://fndhope.org/fnd-hope-research/

- Robson C, Myers L, Pretorius C, et al. Health related quality of life of people with non-epileptic seizures: the role of socio-demographic characteristics and stigma. Seizure. 2018;55:93–99.

- Barnett C, Davis R, Mitchell C, et al. The vicious cycle of functional neurological disorders: a synthesis of healthcare professionals’ views on working with patients with functional neurological disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(10):1802–1811.

- McMillan KK, Pugh MJ, Hamid H, et al. Providers’ perspectives on treating psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: frustration and hope. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;37:276–281.

- Todres L, Galvin KT, Holloway I. The humanization of healthcare: a value framework for qualitative research. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2009;4(2):68–77.

- Seers K. Qualitative systematic reviews: their importance for our understanding of research relevant to pain. Br J Pain. 2015;9(1):36–40.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45–10.

- Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Vol. 11. London (England): Sage; 1988.

- Tyerman E, Eccles FJR, Gray V. The experiences of parenting a child with an acquired brain injury: a meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature. Brain Inj. 2017;31(12):1553–1563.

- Cullingham T, Kirkby A, Sellwood W, et al. Avoidance in nonepileptic attack disorder: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;95:100–111.

- Loewenberger A, Davies K, Agrawal N, et al. What do patients prefer their functional seizures to be called, and what are their experiences of diagnosis? – A mixed methods investigation. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;117:107817.

- Duggleby W, Holtslander L, Kylma J, et al. Metasynthesis of the hope experience of family caregivers of persons with chronic illness. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(2):148–158.

- Karterud HN, Haavet OR, Risør MB. Social participation in young people with nonepileptic seizures (NES): a qualitative study of managing legitimacy in everyday life. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;57(Pt A):23–28.

- Dosanjh M, Alty J, Martin C, et al. What is it like to live with a functional movement disorder? An interpretative phenomenological analysis of illness experiences from symptom onset to post‐diagnosis. Br J Health Psychol. 2021;26(2):325–342.

- Karterud HN, Knizek BL, Nakken KO. Changing the diagnosis from epilepsy to PNES: patients’ experiences and understanding of their new diagnosis. Seizure. 2010;19(1):40–46.

- Karterud HN, Risør MB, Haavet OR. The impact of conveying the diagnosis when using a biopsychosocial approach: a qualitative study among adolescents and young adults with NES (non-epileptic seizures). Seizure. 2015;24:107–113.

- McWilliams A, Reilly C, McFarlane FA, et al. Nonepileptic seizures in the pediatric population: a qualitative study of patient and family experiences. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;59:128–136.

- Moyon RS, Thomas B, Girimaji SC. Subjective experiences of dissociative and conversion disorders among adolescents in India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68(7):1507–1515.

- Nielsen G, Buszewicz M, Edwards MJ, et al. A qualitative study of the experiences and perceptions of patients with functional motor disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(14):2043–2048.

- Pretorius C, Sparrow M. Life after being diagnosed with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES): a South African perspective. Seizure. 2015;30:32–41.

- Rawlings GH, Brown I, Stone B, et al. Written accounts of living with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a thematic analysis. Seizure. 2017;50:83–91.

- Rawlings GH, Brown I, Reuber M. Narrative analysis of written accounts about living with epileptic or psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Seizure. 2018;62:59–65.

- Robson C, Lian OS. “Blaming, shaming, humiliation”: stigmatising medical interactions among people with non-epileptic seizures. Wellcome Open Res. 2017;2:55.

- Sarudiansky M, Lanzillotti AI, Areco Pico MM, et al. What patients think about psychogenic nonepileptic seizures in Buenos Aires, Argentina: a qualitative approach. Seizure. 2017;51:14–21.

- Tanner AL, von Gaudecker JR, Buelow JM, et al. “It’s hard!”: adolescents’ experience attending school with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2022;132:108724.

- Thompson R, Isaac CL, Rowse G, et al. What is it like to receive a diagnosis of nonepileptic seizures? Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14(3):508–515.

- Wyatt C, Laraway A, Weatherhead S. The experience of adjusting to a diagnosis of non-epileptic attack disorder (NEAD) and the subsequent process of psychological therapy. Seizure. 2014;23(9):799–807.

- Scambler G, Hopkins A. Being epileptic: coming to terms with stigma. Sociol Health Illness. 1986;8(1):26–43.

- Szaflarski M. Social determinants of health in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;41:283–289.

- Stone J, Carson A, Hallett M. Explanation as treatment for functional neurologic disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;139:543–553.

- Schibalski JV, Müller M, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Stigma-related stress, shame and avoidant coping reactions among members of the general population with elevated symptom levels. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;74:224–230.

- Cariello AN, Tyler CM, Perrin PB, et al. Influence of social support on the relation between stigma and mental health in individuals with burn injuries. Stigma Health. 2021;6(2):209–215.

- Earnshaw VA, Lang SM, Lippitt M, et al. HIV stigma and physical health symptoms: do social support, adaptive coping, and/or identity centrality act as resilience resources? AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):41–49.

- Brown BJ, Baker S. Responsible citizens: individuals, health and policy under neoliberalism. London: Anthem Press; 2012.

- Marshall M. Mariana Valverde, diseases of the will: alcohol and the dilemmas of freedom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Soc Hist Alcohol Rev. 1999;38–39:63–68.

- Docherty M, Thornicroft G. Specialist mental health services in England in 2014: overview of funding, access and levels of care. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2015;9(1):1–8.

- Sowińska A, Czachowski S. Patients’ experiences of living with medically unexplained symptoms (MUS): a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):1–9.

- Looper KJ, Kirmayer LJ. Perceived stigma in functional somatic syndromes and comparable medical conditions. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(4):373–378.

- Taft TH, Keefer L, Leonhard C, et al. Impact of perceived stigma on inflammatory bowel disease patient outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(8):1224–1232. (8):

- Medina M, Giambarberi L, Lazarow SS, et al. Using patient-centered clinical neuroscience to deliver the diagnosis of functional neurological disorder (FND): results from an innovative educational workshop. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45(2):185–189.

- National Institute for Clinical Guidance (NICE). Suspected neurological conditions: recognition and referral; 2021.

- Stangor C, Crandall CS. Threat and the social construction of stigma; 2000.

- Brown RJ, Reuber M. Psychological and psychiatric aspects of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES): a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;45:157–182.