Abstract

Purpose

Attention to paid work in clinical health care—clinical work-integrating care (CWIC)—might be beneficial for patients of working age. However, the perceptions and expectations of patients about CWIC are unknown. The aim of this study was to develop an understanding of current practices, needs, and expectations among patients for discussing work with a medical specialist.

Materials and methods

A qualitative study was undertaken involving patients with diverse medical conditions (n = 33). Eight online synchronous focus groups were held. A thematic analysis was then performed.

Results

Three themes emerged from the data: (1) the process of becoming a patient while wanting to work again, (2) different needs for different patients, (3) patients’ expectations of CWIC. We identified three different overarching categories of work-concerns: (a) the impact of work on disease, (b) the impact of disease or treatment on work ability, and (c) concerns when work ability remained decreased. For each category of concerns, patients expected medical specialists to perform differing roles.

Conclusions

Patients indicated that they need support for work-related concerns from their medical specialists and/or other professionals. Currently, not all work concerns received the requested attention, leaving a portion of the patients with unmet needs regarding CWIC.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Patients have a wide range of questions regarding work and health, which they want to discuss with their medical specialist

In current clinical practice, not all work concerns get the requested attention, leaving some patients with unmet needs

Cooperation with different health care professionals, including rehabilitation occupational health care, might aid in supporting patients with their work-related questions

Introduction

Employment has positive health effects and improves the overall quality of life and well-being of individuals [Citation1,Citation2]. Having employment can lead to better general and mental health outcomes, promote full participation in society, and reduce poverty [Citation1,Citation2]. In contrast, unemployment is associated with poorer general and mental health, more psychological distress and long-standing illness, as well as higher mortality [Citation2]. At the same time, due to improving health care the number of patients living with chronic diseases is globally increasing [Citation3–6]. Literature shows that ill health and chronic disease are associated with a higher risk of early exit from paid employment [Citation7–10]. Reduced work ability is associated with increased health care use [Citation11], which has negative consequences for both the individual and society.

Work participation and health are thus inter-related, but not all health care professionals in clinical health care (including medical specialists; i.e., physicians with post-graduate specialist training most often working in hospitals such as cardiologists or orthopedic surgeons) are aware of these mutual influences and the role that they could fulfill in supporting patients in work participation [Citation12–16]. As a result, many medical specialists do not take work participation into consideration during treatment [Citation16–21]. This can lead to preventable negative health and work outcomes resulting in long-term unemployment [Citation22–24]. One could speculate that patients of working age would benefit from clinical health care professionals paying more attention to work participation [Citation19,Citation20,Citation25,Citation26], and integrating work as a factor within clinical care. We call this concept clinical work-integrating care (CWIC).

In CWIC, clinical health care professionals pay attention to the interrelationship between work and health, including considering this interrelation during medical decision-making. The underlying principle behind CWIC is an understanding that work-related factors can affect health, and medical actions can affect work participation. CWIC can be as limited as asking “do you work” or as broad as actively supporting people with (chronic) diseases to remain at work for as long as they wish. Thus, both the positive effects of work participation on the patient’s well-being as well as the negative effects of employment as a cause or contributor to illness (e.g., negative work-related health behaviors or exposure to allergens at work) are addressed.

In many countries, attention for work participation in clinical health care traditionally involves offering sick notes or dealing with injured worker claims [Citation13,Citation27–37]. During these tasks, physicians often struggle with work ability assessment, or experience disagreements with insurers [Citation22,Citation32,Citation33,Citation35,Citation37]. These tasks can trigger tension in the physician–patient relationship when a patient wants a specific outcome of the work ability judgment while a physician is obliged to be objective during this assessment [Citation31,Citation38,Citation39]. However, the concept of CWIC would fit well within clinical health care because attention to the interrelationship of work and health within a clinical context would not provoke any conflicts of interest. Instead, the attention to the interrelationship of work and health imposed by CWIC would mean having the understanding that many work-related factors influence health care delivery. This may result in actively supporting patients to remain in work, which is not the same as providing a statement about a patients ability to work. Awareness of this interrelationship might likewise be of benefit to patients.

Although patients may benefit from CWIC, the expectations that patients of working age may have regarding CWIC are unknown. To apply CWIC in its full potential, it is important to know these patients’ perspectives. Therefore, the current study focuses on patient perspective regarding CWIC delivered by the medical specialist within the Dutch context. The aim of this study was to develop a better understanding of the current practices, needs, and expectations surrounding discussing work with a medical specialist from a patient’s perspective. This understanding ultimately contributes to find ways to implement CWIC in common practice.

Methods

Study design

Thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke was chosen to explore patients’ perspectives of current practices, needs, and expectations for discussing work with a medical specialist [Citation40]. The study was undertaken by exploring their experiences through group discussion. To interpret the findings, it is important to understand the Dutch health care system in which a separation between clinical and occupational health care exists, which is unique compared to other countries—an explanation of which can be found in Box 1. This study was designed and reported in accordance with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research [Citation41].

Online synchronous focus group interviews by means of video calling were held to collect the data [Citation42]. Focus group interviews have been shown to be a valuable method for exploring a broad range of views and eliciting information in a short time [Citation43,Citation44]. The richness of focus group data emerges from the group dynamic and diversity [Citation43,Citation44]. Online synchronous focus groups, in general, provide an efficient and secure way to converse across geographic space, while maintaining the advantages of a regular face–to–face focus group dynamic [Citation45]. In the current study, the online setting furthermore provided a physical barrier to secure the safety of our participants during the COVID-19 pandemic. We aimed for groups of 4–6 participants (compared to the regular number of 8–12 in focus groups) [Citation44]. We made this choice because, in our opinion, smaller groups give the opportunity for better engagement in the discussion when video calling, since the discussion is easier to follow for participants with mild cognitive or hearing disabilities and, in general, for those with less experience with video calling.

Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited using two sources, each with a different sampling method. First, convenience sampling within our own networks was used. Participants were recruited from the departments of cardiology, dermatology, oncology, orthopedics, pulmonology, and rehabilitation medicine of the affiliated hospitals of the researchers (both general, academic, and specialized rehabilitation clinics). The treating medical specialist asked patients to participate. If willing, contact details were transferred to the researcher to further inform the participant. The second source was a patient platform set up by the Dutch Patient Federation (ikzoekeenpatient.nl) where purposive sampling was used. An advertisement was placed in their regular newsletter. From the responding patients, a selection was made by an employee of the platform to obtain a heterogeneous sample based on disease, age, and sex before transferring the contact details to the researcher for final inclusion. During the focus group sessions participants from both recruitment strategies were combined. Participants were eligible while: under the treatment of a medical specialist; between 18 and 67 years of age; currently employed, considering employment, or wanting to return to work after absence due to illness; able to speak and read Dutch; and with access to the internet using a personal computer, tablet, or mobile phone with a working camera and microphone.

Procedures and data collection

The key questions for the interview guide were developed by a multidisciplinary group consisting of a physician researcher (LK), rehabilitation physician (CvB), and psychologist (AdB). The interview guide was pilot tested with colleagues and no adjustments were made. The questions are listed in Box 2. The interview guide existed of five main topics. The central aim behind the first three questions was to gain the patients’ perspective of the interactions between themselves and a medical specialist regarding the topic of work participation. The final two topics were addressed to comprehend the experiences with occupational health care in relation to clinical care and the interaction between both health care professionals. Although the focus of the current article was on the patients’ perspective of the interactions between themselves and a medical specialist regarding the topic of work participation, the final two topics provided us important knowledge to develop an understanding regarding patient–medical specialist interactions within the Dutch health care system. Furthermore, in qualitative research it is important to give each data item equal attention [Citation40]. Thus, we evaluated all data to answer our research question. More detailed descriptions of interactions between medical specialists and occupational health care from the patients’ perspective fall beyond the scope of the current article.

A few days ahead of each focus group, participants received a brief questionnaire to obtain their demographic characteristics using the cloud-based clinical data management platform Castor EDC [Citation46]. Hence, the interviewers were aware of this information before the focus groups were held. The participants received instructions for the use of Microsoft Teams and were offered an individual test run [Citation47]. The moderator for all the focus groups was LK (female, MD, PhD candidate) and IO (female, BSc, student of Health Sciences) assisted as an observer. IO also provided technical support when required. The focus groups were organized during working hours. Before the start of the recording, the moderator set ground rules for online video calling and repeated the goal of the meeting and the informed consent, which participants had already received and signed via post or Email. Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions about the procedures and verbally gave consent to start the recording.

Directly after each focus group, LK and IO reflected on the session using a debriefing form following the data collector’s field guide of Mack et al. [Citation43] to elaborate on the main themes that had emerged, any contradicting or confusing information, observations, which could not be distracted form the transcript, any technical problems, and focus points for the next session. Based on this evaluation, LK and IO decided, which main topic needed to be further explored and made changes to some of the follow-up questions when appropriate, such as adding a sub question. Participants were sent a separate online evaluation form to give them the opportunity to comment on their responses during the session by asking this with an open question “Would you like to comment on any of the topics discussed?” [Citation46]. No remarks in the evaluation form were made by the participants that influenced our results. Transcripts were not returned to the participants. Participants received a nonmonetary reward.

Data analysis

All video recordings were transcribed verbatim by LK or IO and corrected by the other. All analyses were done using MAXQDA 2020 [Citation48]. A thematic analysis of the data was conducted following the guidelines of Braun and Clarke [Citation40]. The first five transcripts were coded in duplicate and discussed by LK and IO to check consistency of interpretation [Citation49]. One of these transcripts was coded by a researcher not involved in the focus groups (JvV) to enhance the intercoder reliability [Citation50]. Further duplication was not deemed necessary, since at this point LK and IO made no major differences in their coding. For the final three transcripts, IO did re-read the coding made by LK and any disagreement was discussed. The themes extracted from the data were regularly discussed by LK, IO, and AdW until consensus was reached.

A realist approach was used to report the experiences and reality of the participants [Citation40]. The analysis of all focus groups was performed as an iterative process of six steps, in which both inductive and deductive techniques were used to identify the themes on a semantic level [Citation40]. After familiarization with the data (Step 1) and generating initial codes (Step 2), we used an ecological approach to group the codes into a code tree in the search for themes using the first four transcripts (Step 3) [Citation51]. When reviewing this code tree (Step 4), we found fragmented code groups instead of coherent themes—at this point, we decided to plan four more focus groups. To understand the complexity, we made a mindmap to visualize the relationships between the code groups [Citation52]. This visualization helped us to detect the major themes, which we then named and defined (Step 5). Steps 1–5 were consecutively repeated for the transcripts of focus groups 5 till 8 to refine the themes and check if any new themes had emerged. In addition to these steps, we were able to construct a model describing the patients’ needs and expectations of CWIC on a latent level [Citation40]. After the analysis of the last two focus groups, data saturation was reached [Citation53]. Finally, we produced the current article (Step 6).

Research ethics

The general principles of research ethics outlined in the 2013 World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki were applied [Citation54]. Ethical approval was sought from the Medical Ethical Board of the Amsterdam UMC location AMC but was not required (W20_266 # 20.303). All participants volunteered and returned a written informed consent form.

Results

We organized eight focus groups with a total of 33 participants in September and October 2020, each consisting of 2–7 participants (median = 4). The groups contained a heterogeneous mix of participants with diverse medical histories. A summary of the demographic characteristics and treatment-related factors is found in . Detailed descriptions per focus group and the outcomes of the participants’ evaluation form can be found in Supplementary Appendix 1. We recruited 19 participants through the patient platform of the Dutch Patient Federation and 14 from the affiliated hospitals of the researchers. A slight difference in perspectives was noted between these two groups. The participants from the patient platform often had received several years of treatment, and several of them were involved in patient advocacy groups. They expressed more profound opinions of the care being provided. Patients from the affiliated hospitals, on the other hand, were often being treated for a newly found condition. As a result, they were less experienced with health care and the problems that one might encounter as a working patient. Several participants from both recruitment groups were under treatment by more than one medical specialist. Overall, the recruitment strategy led to a heterogeneous study sample, which provoked lively conversations between the participants. The duration of the focus group ranged from 41 to 128 min.

Table 1. Demographics and treatment-related factors.

Three themes emerged from the analysis of the focus groups. An overview of the themes and their subthemes can be found in . Below, we describe the themes in detail.

Table 2. Themes and subthemes.

Theme 1: the process of becoming a patient while wanting to continue working

While most participants had a strong wish to continue working, they encountered several difficulties when becoming a patient and desiring to continue working despite their health problems. They regarded their medical specialist as a guide to support them during this period (subtheme 1). The process of identifying the patient’s work concerns was described by the participants as an exchange between patient and medical specialist (subtheme 2).

The medical specialist as a first contact for continuing daily life as normal (which includes working)

Becoming sick was a life changing event for many participants. They saw their medical specialists as their guides during this period, thereby establishing a relationship based on trust. Overcoming the first shock, participants started to accept having a disease, and eventually wanted to continue daily life as normal—including life as a working person, as this participant expressed:

“Once I was doing better and the dosage of my medication had been set correctly […] I said to her: ‘Well, what do you think, can I go back to work?’”

(R17, female, 59 years, cardiology, attorney)

To continue daily life meant learning to cope with the restrictions of their disease, including restrictions related to work participation. Participants wanted to discuss sickness and work participation with their specialist, because they regarded their specialist as the expert of their disease and the expert in their future prospects including their abilities to maintain in paid employment. For example, one participant was not aware in advance that he could have expected not being able to kneel after a knee operation which effected his relationship with his workplace (for how long? I need to kneel a lot to do my work). Another participant had experienced severe fatigue during her cancer treatment hindering her to stay in work (does this improve when the cancer is beaten? I hope to work again someday). A third participant recalled to have refused medication because of the side effect of the prescribed drug (does this drug influence my ability to drive? I’m a driver).

When asked directly about their primary motive for bringing up work during a consultation with their medical specialists, almost all participants emphasized that balancing health and work during their treatment was important because work participation was important in their lives. However, the meaning of work differed from person to person. Meanings of work mentioned by the participants included that work contributes to quality of life and that it is a source of social contact as well as a source of income, but the most common meaning was that work is a central part of both individual identity and societal role. This participant captured her identity and social role in work participation emblematic:

“I have always worked fulltime and done volunteer work on the side; I wanted to get going again and not sit at home.”

(R12, female, 48 years, orthopedics, neurology and cardiology, job seeker)

The exchange between patient and medical specialist

Participants explained that an exchange between patient and medical specialist took place in order to allay their concerns about work participation. During this exchange, the specialist would at some point ask about the patient’s work and the patient posed his or her questions about work. Next, the specialist would advise on a strategy for the management of these work concerns. This process most often occurred through direct discussion during a consultation, but other means of communication such as email were used as well. An illustrative example of how this process occurred was given by the following participant:

“[We] have, well, talked about ‘what options do I have in the long run? What are the possibilities?’ And in the end, you, as the client-patient, fill this in yourself. But I did realize then that they indicated ‘listen, you have… this may not be it [your job] anymore, but you may be able to expand the knowledge you have with a study or with a job in a different direction. Go have a good look around.’ And yes, that’s how my own search actually started.”

(R26, male, 44 years, rehabilitation, teacher)

Theme 2: Different needs for different patients

In this theme, we elaborate on three different categories of work concerns that participants struggled with (subtheme 1), the expected role of the medical specialist in relation to these concerns (subtheme 2), and when work participation does not need to be a topic of conversation (subtheme 3).

Three categories of work concerns

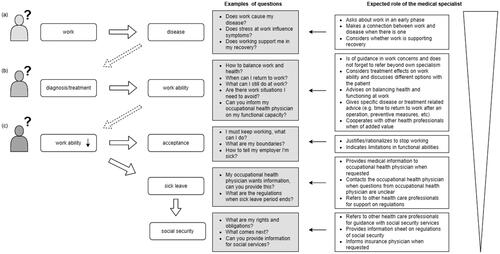

Participants had varying kinds of concerns regarding work and health. These concerns related to the specific circumstances of the participants regarding their disease, symptoms, and disease burden, as well as to their job. Their concerns were also dynamic and changed over time following the participants’ journeys from first contact and diagnosis to later stages of disease and treatment. Within this dynamic process, we identified three main categories of concerns as illustrated in our model in . The first category of concerns (A) related to the impact of work on disease, the second category (B) related to the impact of the disease diagnosis or treatment on work ability, and the third category (C) related to concerns around coming to terms with decreased work ability and practical questions regarding sick leave and social security.

Figure 1. Three-layered model of work-related concerns from a patients’ perspective with exemplary questions and the expected role of a medical specialist. (A) Influence of work on disease (both positive and negative); (B) influence of diagnosis or treatment on work ability (mostly about the negative influence); and (C) work ability will remain decreased, which has to be accepted and gives rise to questions about sick leave and social security. The expected role of the medical specialist is larger for questions in category A and decreases toward category C.

The concerns of category A mostly arose at the beginning of the patient’s journey during the diagnostic phase. Some participants worried about a causal relation between their work and illness in this phase, as is illustrated by the following quote:

“Because I myself am trying to find out what in heaven’s name could be the cause […] Then everything is possible, your work most certainly too.”

(R1, male, 63 years, dermatology, risk manager)

Once diagnosed, it was also noted that work participation can help a patient in illness recovery and should therefore be a part of treatment. This participant had tried to convey this positive effect of work participation to her medical specialist in an attempt to achieve more personalized advice:

“If I can manage that [work] again, it will also help me in my further recovery. Then suddenly the recovery no longer goes in a straight line, but possibly at quite an angle.”

(R8, female, 43 years, gastroenterology, logistics specialist)

Most participants started to have concerns about the impact of their diagnosis or accompanying treatment on their work ability (category B). Work-related questions varied widely within this category, depending on the participant’s work demands and the severity of the symptoms. For example, participants with physically demanding jobs had different concerns than those with office jobs, even though they both may suffer from joint pain. In addition to disease diagnosis, treatment could also have a negative effect on work ability. For some participants this too resulted in concerns, as this participant experienced:

“I have so many complaints during and after the treatments […] that I couldn’t, like, practice my profession anymore.”

(R11, female, 51 years, oncology, cook)

Questions in category C were posed by participants for whom it became clear that work ability would remain decreased because a limit had been reached in what was medically possible to improve. This raised questions about coming to terms with and accepting decreased work ability, as illustrated with this experience:

“I was actually unstoppable. I just wanted to continue what I was doing […] Only, that was really not an option anymore… and that was difficult.”

(R18, female, 52 years, rehabilitation, receiving disability benefits)

Decreased work ability was often accompanied with long term sick leave for the participants and, in some cases, resulted in complete work disability. Participants with decreased work ability faced uncertainties with social security due to complex regulations and financial consequences, which created extra obstacles to continuing life alongside their illness. In many cases, these challenges resulted in frustration that hindered a focus on health, even as a focus on health was considered to be the top priority, as illustrated by the following quote:

“Physically there is something wrong with you and that is what you want to focus attention on. You don’t want to worry about the financial side of it. That should give you peace of mind.”

(R29, female, 58 years, rehabilitation, receiving partial disability benefits - employed)

Not all participants had questions from all categories of this three-layered model as they went along their patient’s journey. For example, one participant had a work accident resulting in a spinal cord injury which made it instantly clear that work ability had and would remain decreased, thereby resulting in having mostly questions from category C. Furthermore, most participants managed to find a balance between work and sickness or only experienced sickness temporarily, meaning that most participants expressed questions from category B. For a few participants, questions existed at multiple levels at the same time. For example, they had questions from category A about the causality between their work and their symptoms when no formal diagnosis had yet been made, but were also on long-term sickness absence since a lot of time had passed in waiting for a diagnosis while being sick listed, which resulted in questions from category C about regulations. These participants in particular also suffered from mental health complaints. It must be noted that other factors, such as informal caregiving, were also mentioned as influencing the participants’ work concerns. However, this falls beyond the scope of the current article.

The role of the medical specialist in relation to differing work concerns

For the different categories (), the participants expected different roles from their medical specialists. Central to this model is the primary role the participants assigned to the medical specialist, which is to be a specialist for medical problems. Therefore, within our model most emphasis was placed on the role of the medical specialist during the early phases of diagnostics and treatment (corresponding to category A), since medical expertise is needed at these stages. Participants expected their specialists to show an interest in their work at these early stages in order to examine work as causal factor in their illness and considered this to be a part of regular health care, as this quote explains:

“Since a doctor is an investigator and has to try to find the cause of something, I do think it’s part of the doctor’s tasks.”

(R1, male, 63 years, dermatology, risk manager)

Over the course of a patient’s journey, concerns related to the influence of disease diagnosis and treatment on work ability arose (category B). The common goal behind the questions in this category was to achieve work participation despite sickness. The role for the medical specialist here was, according to the expectations of participants, to give advice on how to achieve continued work ability or to be clear on when it would no longer be possible to remain working and offer support around accepting this loss (category C). In many cases, participants preferred specialists to offer an estimate on the length of recovery time so that the participant could determine for themselves when it would be possible to return to work. More complex questions also arose regarding balancing sickness, treatment and work, in which cases participants expected their specialist to actively inquire into these questions and not only to refer them to an occupational health physician (who also may not always be available, e.g., in case a worker does not have an employer). In the cases where an occupational health physician was available, cooperation between the medical specialist and occupational health physicians might also have been beneficial so that the occupational health physician was correctly informed about the disease specifics and disease burden. These physicians would then be able to further support the participant with work participation. This ideal scenario did not play out for all participants, leaving a small group of participants with a feeling of injustice and sensation of being pulled and kept downward by the cascade of events. The experience of this participants demonstrates this:

“Because he [the medical specialist] knows better than anyone what a disease entails and how […] you can respond to it. Every body, every situation is different. […] My body did not respond regular to things […] and then you look further. But yes, you could tackle certain things if you say ‘well the specialist has looked at it with me’, and then you can also go to the occupational physician, so look ‘yes you claim this, but this is also [found]’, and then try to get on the same page.”

(R12, female, 48 years, orthopedics, neurology and cardiology, job seeker)

Moving forward along the patient’s journey to the other questions in category C, the expected role of the medical specialist in relation to concerns about work disability was only minor, and other health care professionals were discussed by the participants to better aid them at this point in their patient journey. At this point, participants mainly wanted their specialist to guide them toward the right help or sources of information.

“Look, I don’t think you can expect the average doctor to be aware of all the regulations and things like that. […] That indeed a doctor can at least point you in the right direction.”

(R32, male, 54 years, rehabilitation, consultant)

Work participation does not always need to be a topic of conversation

The participants explained that when their medical specialists took an interest in their work, shared the responsibility, and made decisions about health care delivery jointly with them, it became apparent whether or not there was any direct correlation between work and their health problems. As a result of this clarity, work participation could be taken off the table as a topic of conversations when appropriate without leaving patients with unmet needs or questions. Participants further explained that they could understand that not all diseases have a causal relation with work and therefore may not need further investigation in the relation with work, as this participants highlighted:

“Look, maybe it also depends on what kind of disease you have, right. Because I understand it too, right, that if you have a tumor or a lung problem, you know, but when it comes to your heart, stress and work play a major role, right, I think. So, then it is more obvious that you discuss with your cardiologist as well about what you do to make a living and something like that, right. So maybe that matters a lot too, I can imagine that actually.”

(R17, female, 59 years, cardiology, attorney)

Indeed, not all participants encountered problems at work, because they were able to adjust their work or discuss health concerns with their employer without outside support. Several participants found this important to mention so as not to demand too much from health care and to keep health care affordable (out of respect for the scarcity of time and resources in the health care system).

Theme 3: Patients’ expectations of CWIC during interaction with a medical specialist

Despite many good examples, work participation was not always discussed between medical specialist and patient, and not all specialists took work concerns into consideration even when asked about the topic—an omission for which the participants suggested a number of explanations (subtheme 1). However, participants speculated on solutions and expressed a desire for health care professionals to take on responsibilities in CWIC (subtheme 2). Furthermore, they recognized that they themselves as a patient have a role in CWIC as well (subtheme 3). Overall, they formulated that health care professionals most of all need to be empathetic and work alongside the patient to be able to integrate CWIC and expressed this a precondition (subtheme 4).

Why medical specialists did not always discuss work participation

Exchange of the patient’s work concerns and the specialist’s knowledge about work participation in relation to the disease was not experienced by all participants. One participant described this as a feeling of being in two separate worlds:

“It seemed like two worlds, while as patient you are both employee and patient.”

(R8, female, 43 years, gastroenterology, logistics specialist)

Participants expressed several possible contributing factors to explain these differing experiences, originating from both the medical specialist as person and factors outside of the specialist’s control.

The participants remarked that medical specialists sometimes simply did not discuss work. They attributed this to specialists being focused solely on their own field of expertise or working using a standard medical protocol from which they did not deviate. Therefore, work concerns were not prioritized by the specialists. Other participants encountered specialists who had little knowledge about work-related subjects and who thus evaded such conversations. Participants also reported their specialists stating that they were not allowed to make work-related statements and directing the participants to the occupational health physician without further inquiry into the actual question the participants had. Some participants encountered an empathetic specialist who listened but did not necessarily support them in finding answers to their work-related questions. In contrast, others encountered indifference on the part of their specialist toward their work concerns, causing work concerns to remain unidentified and unresolved. This resulted in indifference toward medical specialists by some participants, as illustrated by this quote:

“They [medical specialists] do their best within their small area of expertise […] And the whole world around it is of no interest to anyone else.”

(R27, male, 51 years, pulmonology and rheumatology, former manager)

Participants attributed a general shortage of time and resources in health care as another explanation for why work concerns were not prioritized by their medical specialists. Yet, most participants desired work-related support from within clinical health care, but it was not their expectation that the specialist should do this, as was pointed out by this participant:

“I can’t expect my specialist [to discuss work] while he measures my blood and goes through my medication […] So, the man or woman simply doesn’t have time for it. It’s not that they don’t want to.”

(R3, male, 58 years, cardiology and rehabilitation, team lead)

Nevertheless, participants appreciated when individual specialists made time to discuss their work-related concerns—for example, by scheduling a new appointment with double the time.

Unmet needs fulfilled by other health care professionals

Despite having unmet needs to discuss work-related concerns within clinical health care, the participants did not expect their medical specialists to solve all their work-related concerns. They understood the following elements of care to be outside the role of specialists: specialists do not determine work ability, do not have extensive knowledge of all occupations, do not provide guidance at work, and do not contact the employer. However, participants expressed that they could not always find resolution for these concerns by themselves and speculated on possible solutions for support. They remarked that many work-related concerns could be solved with help of other health care professionals within the hospital or by cooperating more closely with the occupational health physicians. A few participants speculated on the potential of a new role within the hospital for a health care professional dedicated to work-related problems. Others placed an occupational health physician or rehabilitation physician in this function. Participants explained that the medical specialist should refer them to these professionals, as this quote illustrates:

“That he can say: ‘Well, if you want information about that, go talk to a psychologist or to talk to the social worker.’”

(R29, female, 58 years, rehabilitation, career advisor)

However, in the current practice participants did not always have access to such an alternative. Some participants could turn to other health professionals within the hospital, like an occupational therapist, but not all hospitals provided this. Furthermore, participants experienced shortages of time and resources within occupational health care as well. Long waiting times for receiving regular care, appointments during working hours, and fragmented care due to changes of treating physicians affected the participants’ work participation. This participant experienced these hindrances:

“I found it very difficult that you have to wait so unbelievably long for everything […] Because that means that you go through all those waiting times and that they ultimately make it almost impossible for you to be able to return to your old position.”

(R17, female, 59 years, cardiology, attorney)

For some participants, these experiences triggered dissatisfaction and seeking support elsewhere, without knowing where to look for this support. This is illustrated by the fact that some participants mentioned private clinics as a solution; yet in the Netherlands private clinics, mostly focus on simple diagnostics or offering noncomplex clinical care and do not provide support for work concerns. Once set in motion, this cascade of events (from diagnosis through navigation of complex health care systems and challenges) resulted in prolonged sickness absence for some and forced exit from paid work for others. Furthermore, participants suffered negative mental health impacts. It was not easy for them to escape from such situations. The participants who experienced this described lengthy searches to find support for their work concerns:

“It took me ten years before I finally understood how things worked. And those were ten very hard years, because you fall between the cracks everywhere.”

(R26, male, 44 years, rehabilitation, teacher)

The role of the patient him- or herself

Participants themselves also felt responsible for integrating the topic of work into consultations with their medical specialist, because a patient is responsible for his or her own health and considers whether advice can be followed. They therefore suggested that they themselves have the responsibility to ask questions, actively seek solutions for work problems, and make sure the logistics (e.g., planning of appointments, providing information such that the medical specialist knows who the other involved health care professionals outside the hospital are) surrounding their own health care are well organized. With regard to occupational health care, this last responsibility included the patient making sure to give permission for information exchange between the hospital and the occupational health physician.

“As the patient you also have a role. At least that is my opinion. I think that you have your own responsibility too in your own process.”

(R35, female, 59 years, rehabilitation, director child care)

However, some participants were used to being self-reliant and therefore were not inclined to ask for support. They expressed embarrassment or not wanting to burden the specialist, especially in the context of applications for disability benefits. Others were preoccupied by their disease and forgot to address their work-related concerns, as this participant described:

“I think it’s me too. […] You focus the conversation on ‘how can you get better’ rather than on ‘how can you get better and how can I learn to cope in a working environment.’”

(R2, female, 33 years, pulmonology, financial controller)

Furthermore, not all participants seemed to have the ability to start the conversation about work or the skills to understand the information given by the specialist. Some participants got too overwhelmed by the medical system to be assertive or struggled to comprehend as a result of symptoms related to the disease itself (e.g., cognitive problems or fatigue).

Preconditions for providing CWIC

As a common thread throughout all conversations, participants repeatedly expressed the preconditions for integrating work into consultations with a medical specialist. As set by the participants, these preconditions are: to be open to considering the patient as a person in the context of their daily life (which includes life as a working person) and to respond with understanding to the requests that come forward from this context. Furthermore, they wanted to decide together about their health and have a shared responsibility.

Nevertheless, participants experienced medical decisions mostly following a medical protocol which did not consider personal situations outside the biomedical scope of their disease, such as the experience of this participant:

“I really needed my medical specialist for which work capacity, which medication leads to the most stable possible situation or, and which factors can undermine that. […] And that’s different from his protocol. His protocol is the [disease] under control and done. But some medications gave me such side effects that I said ‘if we control the [disease] a little less, maybe in the long run I can do a little more with a little less medication’. That was for me the most important reason [to discuss work], because I really wanted to go back to work.”

(R19, female, 44 years, pulmonology, former nurse)

In some cases, integrating personal aspects into a consultation did happen and resulted in positive experiences. These positive experiences mostly derived from knowledge around expected functional outcomes that the medical specialist was able to convey the participant in relation to their disease or prognosis. To illustrate, one participant, whose poor prognosis made future work disability inevitable, had a medical specialist clearly explain the impact of the disease on her functional abilities (in this case extreme fatigue). The medical specialist rationally justified reducing work participation to increase the participant’s quality of life as she neared the limits of the physical abilities at work, as she explained here:

“My doctor said during the diagn– the conversation, so to speak, it was actually a bad news conversation, he said to me ‘you have to imagine that your [body] experiences top sport 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year, and all the activities you do in addition, that makes you so tired. You have to find a way to deal with it yourself’.”

(R36, female, 58 years, oncology, team lead)

Nonetheless, it took several conversations with additional health care professionals for this participant to understand the meaning of these words and actually reduce work participation.

Being a patient sometimes meant being vulnerable. By receiving negative responses to concerns, which moved away from regular health care—or what participants referred to as “protocols” as illustrated by the first quote in this subtheme—participants felt unsupported and were left with unmet needs regarding their work-related concerns. However, by sharing the responsibility with their medical specialist, with a specialist clearly explaining what was happening to their health, and with a specialist actively guiding them through the medical system toward other sources of support, the participants felt heard.

Discussion

This study aimed to develop an understanding of the current practices, needs, and expectations around discussing work with a medical specialist from a patient’s perspective. Participants in this focus group study expressed a wide range of work-related questions they had for their medical specialists which reflected the complex relationship between work and health and which fit within the scope of CWIC. Their concerns can be described in a model by arranging them into three categories, namely: (A) the influence of work on disease (both positive as well as negative influences); (B) the influence of disease or treatment on work ability after diagnosis; and (C) support for the acceptance of loss of work ability and concerns about sick leave and social security in a more progressive phase of the disease. Exploring negative influence of work causing disease by medical specialists was often encountered as part of regular clinical health care. However, in current clinical practice a portion of the participants experienced a lack of attention for the other categories of concerns from their medical specialist, leaving them with unmet needs. The participants discussed both personal factors (e.g., showing an interest, having the right knowledge, and the patient’s own responsibility for his or her health) as well as organizational factors (e.g., time constraints and limited resources) as to why this lack of attention occurred. In the context of these factors, participants debated whether they needed the role of their medical specialist to be larger in addressing concerns about influence of work on disease or vice versa (category A and B) compared to the concerns about regulations (category C). Additionally, they stated that other health care professionals may be better equipped to support with the last type of concerns.

CWIC is a new concept that addresses the benefits of engaging work participation in clinical health care [Citation20,Citation55]. In the recent past, some governmental policies have encouraged health care to become more “work-focused” [Citation56]. However, the definition of work-focused health care places a strong emphasis to the responsibilities in work-related care to clinical health care professionals, since it states they have to “accept responsibility for obstacles for work participation” [Citation56]. This does not align with our findings in which the patients wished their medical specialist to focus on medical problems first and stated they also have a responsibility regarding resolving their obstacles for work participation. At the same time our and other patients do wish for an understanding of the importance of work participation for a patient [Citation34,Citation57–60]. Thus, integrating the understanding that work and health (including medical-decisions) affect each other and that this could be an important aspect in clinical health care is supported by patients.

However, medical specialists may hold the perception that addressing work-related issues is not their task [Citation37,Citation38], may lack an understanding of the importance of work participation for the patient [Citation16,Citation37,Citation61,Citation62], may lack training in dealing with work-related issues [Citation32,Citation61,Citation63,Citation64], or may lack time or organizational support to provide work-related support [Citation16,Citation37,Citation61]. In line with the experiences of some of our participants, specialists may focus on different aspects of disease and its management that they address, but in doing so contribute to the experiences of unmet needs for information and support in work participation [Citation18,Citation31,Citation33,Citation65]. When attention was given to work during consultations, it was described as an exchange between patient and medical specialist. Such exchanges (when successful) were characterized by the specialist showing an interest in the patient as a person in his or her context and taking on shared responsibility and shared decision making. These characteristics were regarded as preconditions to enable a consultation about work-concerns and closely relate to the concept of patient-centered care [Citation66–68], which centers a biopsychosocial perspective, regards the patient as person in the context of his or her own social world, and calls for shared responsibility and decision making between patient and physician [Citation66,Citation67]. These characteristics were repeatedly discussed throughout all focus groups.

Work participation is important in all phases of disease, following the patient’s journey from diagnostics to recovery or progressive disease as final end-point as captured in our model. From the early onset of disease, it could be a question whether work is a factor causing or worsening a given disease from the patient’s as well as a medical point of view. However, from within the hospital a medical specialist is limited to history taking and diagnostics only [Citation69,Citation70]. A medical specialist does not have access to the workplace to do any extensive investigation of work-relatedness, nor did the participants find such an undertaking appropriate for a medical specialist to carry out. Within the Dutch health care system, an occupational health physician would be the right person to investigate this [Citation71]. In other countries this is often led by official authorities outside the hospital as well [Citation12,Citation72].

Our participants also mentioned the positive effects work could have on recovery from disease. Especially in psychiatry it has been recognized that employment can be supportive to promote recovery [Citation73–76]. However, the effects of having employment on physical health has not yet been thoroughly explored [Citation1].

The impact of disease on work participation was most thoroughly discussed by our participants, since many participants had experienced work participation problems during the course of their treatment. They expected their medical specialist to give advice on balancing disease and work participation. Upon review of aspects of vocational rehabilitation using the model of the International Classification of Functioning, disability and health (ICF) [Citation77,Citation78], it is evident a patient requires information on expected limitations in activities or participation resulting from the disease or the expected impact that treatment might have in order to balance work and health. For example, a patient should understand in advance to expect the limitation of not being able to kneel after a knee operation (for how long? I need to kneel a lot for my work), to expect fatigue after a cancer diagnosis (does this improve when the cancer is beaten? I hope to work again someday), and to expect any side effects of prescribed drugs (does this drug influence my ability to drive? I’m a driver). In this advice, patients require some extent of detail so it will fit in the context of their daily work lives [Citation34,Citation65].

Not all concerns the participants mentioned required the expertise of a medical specialist. Work-related concerns in further advanced stages of illness or injury when work ability would remain decreased had a different nature and required expertise on sick leave and social security regulations. The main request for the medical specialist was to inform the occupational health or insurance physicians when requested or to direct the patient themselves to the correct sources of information to learn about these regulations. Informing the occupational health or insurance physicians is in line with the guideline for dealing with medical data from the Royal Dutch Medical Association (KNMG) [Citation79]. However, some participants needed more guidance than could be given via information sharing alone, because patients can be unsure about what procedures are involved [Citation65].

Methodological considerations

We reflect on the strengths and limitations of our study in accordance with the commonly used aspects of trustworthiness, that is, credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [Citation80]. These aspects can be regarded as the qualitative counterparts to determine the quality in quantitative research [Citation81], in which credibility refers to internal validity (important strategies are, e.g., collecting data of a prolonged period, being reflective on biases, triangulation), transferability refers to external validity (important strategy is provision of a detailed description of the context), dependability refers to reliability (important strategies are, e.g., being clear about the research process and peer review), and confirmability refers to objectivity (important strategies are, e.g., being neutral and using “negative” cases).

To obtain credibility, we used triangulation to recruit our participants by combining two recruitment strategies, namely purposive sampling through the Dutch Patient Federation and convenience sampling by medical specialists from our own networks. This resulted in two slightly different groups of patients. When we would have used only participants recruited from our own networks, this probably would have let to a selection bias due to the physicians willing to help us to find the best suitable patients to interview and acquiescence bias due to patients wanting to support their physician. When we would have used only participants recruited from the Dutch Patient Federation this too would have given a selection bias, because in this group we found patients participation in patient advocacy groups with more profound opinions toward health care delivery. By using these two groups and mixing the patients during the focus group sessions we reduced these biases which increases the credibility.

However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were forced to use online methods that provided a physical barrier to protect the safety of our participants. This might have influenced the credibility of our findings [Citation80]. In the early days of the use of online focus groups, it was debated as to whether nonverbal signs conveyed through body language could be obtained [Citation82]. However, this disadvantage has been noted in the use of asynchronous focus groups using chat rooms. Due to improvements in internet technology, we were able to use synchronous methods with face–to–face video calling allowing us to notice the nonverbal signs. Furthermore, the advantage this online method provided us was geographical freedom. We were able to interview people from across the Netherlands who otherwise may not have been brought together in one focus group. This geographical advantage is also mentioned by other authors [Citation45,Citation83]. A result of this freedom was the heterogeneous composition of the focus groups, including patients with different medical histories and experiences within health care delivery increasing the triangulation within our sample. This increases the credibility of our study. In contrast, most studies, which investigate work discussions in a clinical setting focus on one specific patient population (e.g., breast cancer survivors, young adults with acquired brain injury) [Citation16,Citation30,Citation34,Citation39,Citation58,Citation59,Citation65,Citation68].

To reduce social desirability bias as a measure to increase the credibility, we composed smaller focus groups, compared to 8–12 person group size that is normally advocated [Citation45]. In these smaller groups we noticed a different group dynamic, resulting in more felt cohesion and natural conversations, which the participants emphasized at the end of all sessions. In contrast, when we held one larger focus group of seven participants everyone waited for their turn from the moderator before speaking, whereby sometimes participants were reacting to a subject started 2–3 speakers earlier which disrupted the flow of the conversation.

Another limitation of the study design, which may have influenced the credibility, was the short time frame of 2 months in which all eight focus groups were held, leaving little time for reflection and analysis of the results prior to the last group. Therefore, the researchers were not able to detect the major themes before the end of the last focus group. However, upon analyzing the final two groups we found that the narratives of the participants were similar and, thus, no new theoretical insights emerged and data saturation had been reached [Citation53]. This revealed that it was not necessary to conduct any further focus groups.

To ensure the transferability of our findings to other situations [Citation80], we provided a detailed description of the Dutch health care context in Box 1 and a detailed description of our focus groups and participants in Supplementary Appendix 1. Within our diverse group, we found that many participants struggled with the same problems regarding work concerns and their health. By placing these different participants together, we were able to highlight this commonality, resulting in our model having a generalizable applicability.

To enhance the dependability of our research [Citation80], we followed the six-step guideline of thematic analysis of Braun and Clarke [Citation40]. All decisions throughout the process were made in accordance with this guideline, as we have described in our methods section.

To establish confirmability [Citation80], we paid attention to balance our quote’s equal across our sample. Yet, some participants were able to express their experiences with more striking examples. Choosing the quotes and all other minor decisions were discussed with at least two members of our research team consisting of researchers with different backgrounds. All major decisions from development of the study design till reporting were deliberated with all members of our research team.

Implications for research and practice

In the context of an aging workforce, the absolute number of working patients will increase in the coming decades [Citation3–5]. Therefore, it might be to the benefit of patients if clinical health care were more aware of the needs of this particular group. This conclusion is supported by the results of this focus group study. With this study we constructed a model which could aid in understanding patients’ concerns and expectations. This model could aid clinical practice in structuring the patients’ needs regarding work participation or used as tool in further research.

A majority of the participants indicated a need for support with work-related concerns from their medical specialists. Considering the ICF model [Citation77,Citation78], to answer most work-related concerns requires getting information on limitations in daily activities resulting from disease or treatment. One might expect to get this information from a medical specialist [Citation84], especially since it does not require the medical specialist to have extensive occupational health knowledge [Citation26]. However, what the consequences of the limitations are, will differ for each person based on the different job requirements. It can be debated that this should be the own responsibility of the patient [Citation16,Citation65]. In the Netherlands, an occupational health physician could guide a patient in this process (see Box 1). It could be a topic for further research to explore how the ICF model could be applied to aid the different health care professionals to support work participation of their patients.

Reversely, within our model patients also had questions concerning work-relatedness of disease. If medical specialists were more aware of work-relatedness and questioned this from within the hospital, the specialist could then deliberate on any suspicion of occupational disease with an occupational health physician for further evaluation [Citation12]. The occupational health physician could then take adequate actions, which could in turn help with prevention or early detection of occupational and work-related diseases [Citation85,Citation86]. This might also reduce the burden of illness due to occupational exposure [Citation87,Citation88] and support a healthy work force in general.

It is important for patients that the medical specialist in clinical health care supports work participation despite ill-health, wherever possible [Citation25,Citation26]. Yet, regarding the patient–physician interaction, CWIC was considered as part of patient-centered care by the participants. This implies that a patient takes responsibility for his or her own care. Likewise, the medical specialist will effectively clarify the patient’s goals regarding work participation and support these work participation goals. This could improve the efficacy of health care delivery [Citation89–91] and empower the sometimes vulnerable patient to start a conversation about their work concerns and find solutions for their work participations problems. How to achieve CWIC within current patient-centered care delivery could be a topic for further research. Better cooperation with other health care professionals, especially professionals within occupational health care such as the occupational health physician, might be part of the solution. This could broaden the support network of the patients and reduce the workload for a single medical specialist.

Conclusion

Patients indicated that they needed support for work-related concerns from their medical specialists and/or other professionals. Patients expressed different work-related concerns reflecting all aspects of the relationship between work and health, including both the positive effects of work participation on the patient’s well-being or recovery as well as the negative effects of employment as a cause or contributor to illness. Work-related concerns depended on the stage of the disease (i.e., from first diagnosis to progressive disease), the symptoms influencing the patient’s work ability, and the patient’s work situation. Currently, not all work-related concerns received the requested attention by medical specialists, leaving a portion of the patients with unmet needs regarding CWIC.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (564.2 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all participants in this study for sharing their experiences and for their time investment. The current study was conducted with financial support from the department of Public and Occupational Health at the Amsterdam UMC.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Box 1. Explanation of the Dutch health care system

Within the Dutch health care system, there exists a separation between clinical and occupational health care [Citation25]. The rationale behind this is that tasks within occupational health care (such as providing a sick note) can provide a conflict of interest for the physician when a patient does not agree with the outcome. For example, when patient and physician disagree on the question whether a patient is fit to return to work. When the physician providing sick notes is also the treating physician, this could harm the physician–patient relationship, since the patient might subsequently disagree on the proposed treatment as well [Citation38,Citation92]. Therefore, in the Netherlands health care professionals in clinical health care—such as medical specialists—provide treatment for disease without the burden of these occupational health task to maintain a good provider–patient relationship [Citation25].

Sick leave guidance is regulated by the Gatekeeper Improvement Act [Citation93]. This law only applies for employed people and comes into force from the moment an employee calls in sick. From this moment onwards, the employer continues paying the employee and both employer and employee have to make an effort to enhance return–to–work over a period of two years. The occupational health physician acts as a gatekeeper during this two years between employee and employer. When an employee is not able to return–to–work within this timeframe an insurance physician will then provide medical advice on eligibility on a disability benefit claim.

One of the efforts an employee can make is to seek advice from a medical specialist. In accordance with the guideline for dealing with medical data from the Royal Dutch Medical Association (KNMG) [Citation79], the medical specialist is allowed to provide details of a patient’s treatment to the occupation health or insurance physician. This is mostly the only point of contact between clinical and occupational health care in the Netherlands. However, many patients are not aware of these tasks when they first become ill, since most often their first point of contact is clinical health care and not occupational health care [Citation25]. Furthermore, this law does not apply to self-employed and unemployed patients, resulting that they most often do not have access to occupational health care [Citation25,Citation94].

Box 2. Interview guide (original language, Dutch)

1. Have you ever discussed work-related questions with your physician at the hospital?

a. If so, what is your experience with this?

b. If not, what is the reason you never discussed this?

2. What is the most important reason for you to bring up your work during a consultation with your physician in the hospital?

3. CWIC deals with problems at the interface between health and work. What role do you think your medical specialist has in CWIC?

4. Have you ever been to an occupational health physician?

a. If not, we continued to question 5

b. If so, do you know whether there was contact between your occupational health physician and your medial specialist and what is your experience with this?

5. How do you think cooperation between the hospital and the occupation health physician could improve?

Data availability statement

The data is not available for others at this point in time. If an individual is interested in the data, however, they can send a request to the corresponding author.

References

- van der Noordt M, IJzelenberg H, Droomers M, et al. Health effects of employment: a systematic review of prospective studies. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(10):730–736.

- Waddell G, Burton A. Is work good for your health and well-being?. London: The Stationery Office; 2006.

- England K, Azzopardi-Muscat N. Demographic trends and public health in Europe. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(suppl_4):9–13.

- Hajat C, Stein E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: a narrative review. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:284–293.

- Schoemaker CG, van Loon J, Achterberg PW, et al. The public health status and foresight report 2014: four normative perspectives on a healthier Netherlands in 2040. Health Policy. 2019;123(3):252–259.

- Mathers CD, Stevens GA, Boerma T, et al. Causes of international increases in older age life expectancy. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):540–548.

- Schuring M, Robroek SJ, Otten FW, et al. The effect of ill health and socioeconomic status on labor force exit and re-employment: a prospective study with ten years follow-up in The Netherlands. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2013;39(2):134–143.

- Alavinia SM, Burdorf A. Unemployment and retirement and ill-health: a cross-sectional analysis across european countries. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;82(1):39–45.

- van Rijn RM, Robroek SJ, Brouwer S, et al. Influence of poor health on exit from paid employment: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(4):295–301.

- Leijten FR, de Wind A, van den Heuvel SG, et al. The influence of chronic health problems and work-related factors on loss of paid employment among older workers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(11):1058–1065.

- Reeuwijk KG, Robroek SJW, Hakkaart L, et al. How work impairments and reduced work ability are associated with health care use in workers with musculoskeletal disorders, cardiovascular disorders or mental disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(4):631–639.

- Moscato G, Maestrelli P, Bonifazi F, et al. Occupation study (occupational asthma: a national based study): a survey on occupational asthma among italian allergists. Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;97:657.

- Wada K, Ohtsu M, Aizawa Y, et al. Awareness and behavior of oncologists and support measures in medical institutions related to ongoing employment of cancer patients in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42(4):295–301.

- Yagil D, Eshed-Lavi N, Carel R, et al. Health care professionals’ perspective on return to work in cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27(4):1206–1212.

- Varekamp I, Haafkens JA, Detaille SI, et al. Preventing work disability among employees with rheumatoid arthritis: what medical professionals can learn from the patients’ perspective. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(6):965–972.

- MacLennan SJ, Murdoch SE, Cox T. Changing current practice in urological cancer care: providing better information, advice and related support on work engagement. Eur J Cancer Care. 2017;26(5):e12756.

- Buijs P, Weel A. Blinde vlek voor arbeid in de gezondheidszorg: buitenlandse remedies voor nederlands probleem? [blind spot for labor in health care: foreign remedies for dutch problem?]. Hoofddorp: TNO; 2005.

- Nilsing E, Söderberg E, Normelli H, et al. Description of functioning in sickness certificates. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(5):508–516.

- Bartys S, Edmondson A, Burton K, et al. Work conversations in healthcare: how, where, when and by whom: a review to understand conversations about work in healthcare and identify opportunities to make work conversations a part of everyday health interactions. London: public Health England; 2019.

- Black CM. Working for a healthier tomorrow: dame carol black’s review of the health of britain’s working age population. London: The Stationery Office; 2008.

- World Health Organization. Connecting health and labour: bringing together occupational health and primary care to improve the health of working people. Global conference “connecting health and labour: what role for occupational health in primary health care”; 29 November to 1 December 2011; The Hague, the Netherlands: WHO Press; 2012.

- Russell E, Kosny A. Communication and collaboration among return-to-work stakeholders. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(22):2630–2639.

- Brannigan C, Galvin R, Walsh ME, et al. Barriers and facilitators associated with return to work after stroke: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(3):211–222.

- Magalhães L, Chan C, Chapman AC, et al. Successful return to work of individuals with chronic pain according to health care providers: a meta-synthesis. Cad Bras Ter Ocup. 2017;25(4):825–837.

- KNMG. KNMG-visiondocument care that works: To a better work-oriented medical care for (potential) workers [KNMG-visiedocument zorg die werkt: naar een betere arbeidsgerichte medische zorg voor (potentieel) werkenden]. Utrecht: KNMG; 2017.

- Walker-Bone K, Hollick R. Health and work: what physicians need to know. Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21(3):195–200.

- Hayman K, McLaren J, Ahuja D, et al. Emergency physician attitudes towards illness verification (sick notes). J Occup Health. 2021;63(1):e12195.

- Ladak K, Winthrop K, Marshall JK, et al. Counselling patients for return to work on immunosuppression: practices of Canadian specialists during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39(4):874–878.

- Salit RB, Lee SJ, Burns LJ, et al. Return-to-work guidelines and programs for post-hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors: an initial survey. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26(8):1520–1526.

- Tiedtke C, Donceel P, Knops L, et al. Supporting return-to-work in the face of legislation: stakeholders’ experiences with return-to-work after breast cancer in Belgium. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(2):241–251.

- Morrison T, Thomas R, Guitard P. Physicians’ perspectives on cancer survivors’ work integration issues. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(1):e36-42–e42.

- Kosny A, Lifshen M, Yanar B, et al. The role of healthcare providers in return to work. Int J Disabil Manag. 2018;13:e3.

- Szekeres M, Macdermid JC, Katchky A, et al. Physician decision-making in the management of work related upper extremity injuries. Work. 2018;60(1):19–28.

- Newington L, Brooks C, Warwick D, et al. Return to work after carpal tunnel release surgery: a qualitative interview study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019 2019;20(1):1–11.

- Holmlund L, Guidetti S, Eriksson G, et al. Return-to-work: exploring professionals’ experiences of support for persons with spinal cord injury. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28(7):571–581.

- Ljungquist T, Hinas E, Nilsson GH, et al. Problems with sickness certification tasks: experiences from physicians in different clinical settings. A cross-sectional nationwide study in Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:321.

- Frank C, Lindbäck C, Takman C, et al. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of their work with patients of working age with heart failure. Nord J Nurs Res. 2018;38(3):160–166.

- Swartling M, Wahlstrom R. Isolated specialist or system integrated physician–different views on sickness certification among orthopaedic surgeons: an interview study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:273.

- Main DS, Nowels CT, Cavender TA, et al. A qualitative study of work and work return in cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2005;14(11):992–1004.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Stewart K, Williams M. Researching online populations: the use of online focus groups for social research. Qual Res. 2005;5(4):395–416.

- Mack N, Woodsong C, MacQueen KM, et al. Qualitative research methods: a data collector’s field guide. Durham (NC): Family Health International; 2005.

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE; 2015.

- Wirtz AL, Cooney EE, Chaudhry A, American Cohort To Study HIV Acquisition Among Transgender Women, et al. Computer-mediated communication to facilitate synchronous online focus group discussions: Feasibility study for qualitative HIV research Among transgender women Across the United States. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e12569-e12569.

- Castor. Castor electronic data capture. Version 2020.2. Amsterdam: Castor; 2019.

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft teams. Version 1.4.00.19572. Redmond (WA): Microsof Corporation; 2017.

- VERBI Software. Maxqda 2020. 20.3.0. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software; 2019.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

- O’Connor C, Joffe H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:160940691989922. 1609406919899220.

- Richard L, Gauvin L, Raine K. Ecological models revisited: their uses and evolution in health promotion Over two decades. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32(1):307–326.

- Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res. 2001;1(3):385–405.

- Charmaz K, Thornberg R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):305–327.

- World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194.

- Buijs P, Bongers P, Klauw D, et al. Care for work. How can (primary) health care contribute to a healthy labor force [zorg voor werk. Hoe kan de (eerstelijns) zorg bijdragen aan een gezonde beroepsbevolking]. The Hague, Netherlands: TNO; 2014.

- Bartys S, Stochkendahl MJ. Work-focused healthcare for low back pain. In: Boden SD, editor. Lumbar spine online textbook. Towson (TX): Data Trace Publishing Company; 2018.

- Bosma AR, Boot CRL, Schaafsma FG, et al. Facilitators, barriers and support needs for staying at work with a chronic condition: a focus group study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–11.

- Dugan AG, Decker RE, Namazi S, et al. Perceptions of clinical support for employed breast cancer survivors managing work and health challenges. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;15(6):890–905.

- Paniccia A, Colquhoun H, Kirsh B, et al. Youth and young adults with acquired brain injury transition towards work-related roles: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(11):1331–1342.

- Hollick RJ, Stelfox K, Dean LE, et al. Outcomes and treatment responses, including work productivity, among people with axial spondyloarthritis living in urban and rural areas: a mixed-methods study within a national register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(8):1055–1062.

- Lamort-Bouche M, Peron J, Broc G, FASTRACS Group, et al. Breast cancer specialists’ perspective on their role in their patients’ return to work: a qualitative study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46(2):177–187.