Abstract

Purpose

Low back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of disability worldwide. Providing evidence-based practice (EBP) for patients with LBP is more cost-effective compared with non-EBP. To help health care professionals provide EBP, several clinical practice guidelines have been published. However, a relatively poor uptake of the guidelines has been identified across various countries. To enhance future implementation of EBP, the aim of this study was to explore barriers to using LBP guidelines in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

A qualitative constructivist grounded theory design was employed in order to gain an in-depth understanding of the barriers. Semi-structured interviews (+/− observations) of nine physiotherapists and nine chiropractors from primary care in the Central Denmark Region were conducted.

Results

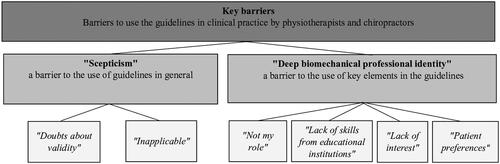

Two key barriers were found to using guidelines in practice: (1) a scepticism due to doubts about validity and applicability of the guidelines, which emerged particularly among physiotherapists; and (2) a deep biomechanical professional identity, due to perceived role, interest, lack of skills, and patient preferences, which emerged particularly among chiropractors.

Conclusions

For guidelines to be better implemented in practice, these key barriers must be addressed in a tailored strategy. Furthermore, this study showed a difference in barriers between the two professions.

Implications for Rehabilitation

It is important that physiotherapists and chiropractors reflect on what constitutes their core task and professional identity if the implementation of the biopsychosocial model is to be successful.

To overcome the barrier of scepticism towards guidelines, the applicability of the guidelines could be improved by elaborating on how the recommendations could be individualised.

It is important to incorporate the biopsychosocial model into the programs of educational institutions and provide training to improve those skills in physiotherapists and chiropractors.

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of disability worldwide, and is associated with a significant burden to both patients and society [Citation1,Citation2]. According to the most recent Global Burden of Disease study published in 2020, Denmark has the third-highest burden of disease due to musculoskeletal disorders in the world, of which people with LBP constitute the largest group by far [Citation3]. Denmark is a welfare state, where most health care services and sickness benefits are state-funded. An annual average for the years 2010 to 2012 showed that the direct costs of treatment, sick leave and early retirement due to LBP amounted to around EUR 900 million (= 0.36% of BNP) [Citation4–6].

It is well documented that providing evidence-based practice for patients with LBP is more cost-effective compared with non-evidence-based practice, as it leads to larger reductions in pain and disability with fewer treatments [Citation7–10]. Providing evidence-based practice requires health professionals to incorporate existing research findings into their treatment, in combination with their clinical expertise and the patients’ preferences [Citation11]. To help health care professionals provide evidence-based practice for patients with LBP, several clinical practice guidelines have been published and continuously updated in the past decade [Citation12–17]. Clinical guidelines aim to help bridge the gap between practice and research. The clinical guidelines synthesise the latest knowledge and evidence within a defined area and present it to health professionals by providing indication for action, e.g., performing certain examinations or treatments for specific patient groups. However, although considerable effort and resources have been spent developing these guidelines [Citation18], several studies have identified relatively poor uptake of these guidelines, where the implementation of the biopsychosocial approach, in particular, is lacking [Citation19–21]. Studies also show that patients with LBP receive inconsistent information and experience fragmented pathways [Citation22–25], indicating that implementation of an evidence-based standardised practice has not yet been achieved.

Previous research has identified a number of barriers to implementing the LBP guidelines. The main barriers identified have been limited time, patient preferences and lack of knowledge, confidence and skills of health care professionals to apply the biopsychosocial treatment approach recommended in the guidelines [Citation19,Citation26–31]. Additionally, although the barriers for the implementation of the guidelines have been known for more than 20 years [Citation32] and several implementation strategies have been tested [Citation33,Citation34], health professionals still do not sufficiently adhere to the guidelines [Citation21,Citation35,Citation36].

There may be several reasons for this continued challenge with guideline uptake in practice. Implementing guidelines is about changing the behaviour of health professionals, and for behaviour change to be effective, the strategy needs to be tailored to the contextual barriers that are impeding the behaviour change [Citation37]. Thus, in order to attain successful implementation, it is of utmost importance that we identify the local barriers to implementing the guidelines by particular groups of health professionals [Citation38,Citation39]. Previous attempts to implement guidelines may have underestimated the importance of the local context, resulting in the poor uptake seen across countries today [Citation21].

Two Danish studies have also shown challenges with guideline-adherent practice among physiotherapists and chiropractors providing LBP health services [Citation40,Citation41]. In Denmark, private physiotherapy and chiropractic practices play a pivotal role in LBP management, with patients who have LBP accounting for 30% of all visits to a physiotherapist or chiropractor [Citation6]. Therefore, it may have a significant impact on the patient and society burden of LBP in Denmark if physiotherapists and chiropractors provided evidence-based practices [Citation7–10]. The barriers for implementing LBP guidelines within these two groups of health professionals has not yet been explored in a Danish context. This leaves us without knowledge about how to develop efficiently tailored implementation strategies. Therefore, to enhance future implementation, the aim of this study was to explore barriers to using LBP guidelines in clinical practice by Danish physiotherapists and chiropractors.

Methods

A qualitative constructivist grounded theory design was employed in order to gain an in-depth understanding of the barriers to the use of guidelines by physiotherapists and chiropractors [Citation42]. Grounded theory was chosen as it aims to construct theories that are rooted (grounded) in practice and thus applicable to practice [Citation42].

Study context

The study was conducted in private physiotherapy and chiropractic practice settings in the Central Denmark Region, where 1.3 million citizens reside. In Denmark, health care services are largely free of charge and independent of the individual’s income. However, with respect to private physiotherapy and chiropractic practice, the public health insurance covers only 40% and 20% of the expenses, respectively. The main differences between the two professions are, that authorised physiotherapists hold a professional bachelor’s degree following a tertiary education of 3.5 years’ duration, while chiropractors hold a 5-year master’s degree in clinical biomechanics followed by a 1-year internship [Citation43,Citation44]. Furthermore, patients do not have direct access to physiotherapy consultations, but must be referred either from their general practitioner or from the secondary (hospital) sector [Citation45]. In contrast, patients consulting chiropractors have direct access to their services. In terms of clinical practice guidelines in Denmark, three national clinical guidelines have been developed for the treatment of patients with LBP and in addition, one regional guideline that focusses on the organisation and timing of the health care services provided, e.g., timing of referral to secondary care [Citation12–14,Citation17]. The developing process of the guidelines is described in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Researcher characteristics and reflexivity

In the current study, the first author (M.H.H.) is a female physiotherapist with 8 years of clinical experience working in private clinics and 5 years of research experience within the field of LBP. The background of the first author ensured an in-depth understanding and knowledge about the terminology used and enhanced the sensitivity regarding the field of research [Citation42]. The four co-authors are experienced researchers within the field of LBP and with different professional backgrounds (two physiotherapists (N.R., A.G.), one nurse (C.B.R.), and one chiropractor (T.S.J.)). The researcher triangulation (comparison of data analysis between the researchers) contributed with different perspectives in the data analysis, and thereby promoted the sensitivity of the data [Citation46].

Data collection

Theoretical sampling of participants

In order to capture rich data, the initial purposive sampling was conducted to get diversity in location, demographic variables (age and sex), variables related to education and occupation (professional experience, size and type of clinic) and level of adherence to guidelines (assessed in a survey conducted prior to this study [Citation40]) [Citation42]. To be eligible to participate in the study, the physiotherapists and chiropractors had to be practising in a private clinic, and managing at least one patient with LBP per week. Ongoing analysis guided a further theoretical sampling [Citation42]. For example, the data showed that there was a tendency for participants to have either a biomedical or a biopsychosocial approach. In order to explore if the participants’ approach had an impact on their use of guidelines, those having a biomedical as well as those having a biopsychosocial approach were invited. Thus, a snowball strategy was used asking already-recruited participants if they could refer us to other participants with primarily either a biomedical or a biopsychosocial approach, respectively. We contacted 36 clinics which resulted in nine participating physiotherapists and nine chiropractors from 14 clinics (see ). All the clinics or health professionals responding that they were interested in participating were subsequently contacted by telephone to make appointments for study visits at the clinic. Clinics not responding to the initial invitation were also contacted by telephone by M.H.H. to repeat the invitation. The clinics were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. A large part of the clinics declined the telephone invitation due to busyness.

Table 1. Description of participants’ demographic factors.

Theoretical sampling of data

In accordance with grounded theory, a theoretical sampling of data was carried out by jointly collecting, coding and analysing the data, meaning that the initial analysis of the data from one interview or observation guided the subsequent data collection until a theory emerged [Citation47]. Two types of data were collected: (1) data from formal and informal interviews and (2) field notes associated with participant observation [Citation48]. The informal interviews were conducted immediately after the observations to deepen the understanding of the behaviour, if there had been any cause for wonder during the observations. Throughout all study stages, memos were written to prompt analysis, capture creative thoughts, and follow up on instincts.

By triangulating data, using both interviews and observations, we aimed to strengthen the validity, as the information from an observation could be elaborated in subsequent interviews or vice versa. Triangulation of data also strengthened a deeper and more nuanced understanding of potential barriers, as the observations of participants’ practices were not always consistent with their own narratives of their practices. By using triangulation, theoretical saturation was reached [Citation46]. The triangulation was conducted by M.H.H. in an ongoing dialogue with C.B.R. The data were collected between September 2019 and December 2020 by M.H.H.

Interviews

The interviews were all planned to be conducted as physical face-to-face sessions, but because of the COVID-19 pandemic, 11 out of 19 interviews were conducted virtually (video) or by telephone. To minimise any risk of bias induced by the change in data collection method, a slightly different introduction was given in the interviews conducted by telephone or video, and more effort was put into communicating presence in form of “yeah,” “okay,” and “right” given by the interviewer. Also, more time was allocated for the video interviews to facilitate a safe and trusting atmosphere, by ensuring that the participants felt confident with the format before initiating the actual interviews [Citation49,Citation50]. The physical face-to-face interviews took place at the participants’ workplaces. Interviews lasted from 30 to 75 min, with an average of 49 min. Before initiating the interview, the participants were informed that the aim of the study was to learn more about their work processes, experiences of patients’ preferences, their thoughts on what challenges their practice, and how to improve LBP clinical practice. All interviews were constructed with introductory questions followed by open-ended questions, such as: How do you usually advise patients with LBP regarding physical activity? capturing the participants’ experiences and thoughts regarding the key guideline recommendations, and also the barriers to using the guidelines. Subsequently, the interview questions became more focused in order to elaborate the participants’ approach towards managing patients with LBP, e.g., How do you feel addressing patients’ psychosocial factors?

The interview was guided by our overall research questions and practice interests, but due to the theoretical sampling, the interview guide was continually modified to develop the emerging categories (see Supplemental Appendix 2). For example, a question regarding the participants’ perception of their core role was developed on the basis of a memo from the first interview with Participant 301. In the memo, M.H.H. wrote: “He (P301) feels responsible for making it all come together: What does the participant experience as his core task/role?”

Observations

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, observations of four physiotherapists and three chiropractors were cancelled. Observations of a total of five physiotherapists and six chiropractors were carried out, together managing a total of 31 patients (see ). Despite canceled observations, a thick description of the clinical practice was obtained from the 31 observations, which led to a nuanced understanding of the barriers [Citation42]. Each observed consultation lasted between 15 and 60 min. Field notes and memos were made during and after the observations. The focus of the observations was the participants’ clinical practice in general, and specifically on given key guideline recommendations, for example advice on work and physical activity. If elements from the guidelines (e.g., patient education) were not addressed during the observation, or if the participants’ behaviour deviated from the recommendations in the guidelines, this was noted and explored in the following formal or informal interview. For example, Participant 206 advised a patient not to perform normal activities, like emptying the dishwasher and participating in yoga classes after the treatment. This was noted and the reason for the advice was subsequently explored by informal interview.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using a grounded theory design and an abductive approach and constant comparative method [Citation42]. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a research assistant. M.H.H. read through the transcriptions while listening to the audiotaped interviews to maximise familiarity with the data. Data were collected in native language (Danish) and quotes were translated to English by M.H.H. An experienced proof reader validated the translations. All data, including memos, were then coded by MHH using NVivo 12 software. The analytical process was conducted at three levels.

At level one, initial line-by-line coding was conducted by M.H.H., defining and labelling what was seen as significant in the data in relation to the aim. Barriers identified in the material were then grouped into preliminary codes and patterns describing the participants’ explanations or M.H.H.’s observations of barriers. Five categories were constructed, grounded in the initial codes, encompassing: lack of trust in the guidelines; lack of motivation; lack of skills; approach towards management of patients with LBP; core task. The analysis was continuously discussed with co-author C.B.R.

At level two, a focused analysis was conducted by M.H.H. and C.B.R. using comparative methods. The analysis revealed that the most frequent categories from the initial coding embraced the participants’ “approach to management of patients” and “lack of skills.” The initial categories “lack of trust” and “motivation” were also found as significant categories but were merged and reconstructed to form the new category of “lack of willingness.” In an abductive process, theoretical ideas about what might cause the barriers to using the guidelines was tested by asking theoretical questions of the data set, e.g., Why do the participants experience a lack of willingness? Axial coding was used to identify the following three tentative categories and subcategories: (1) “Lack of willingness to implement guidelines due to lack of trust and/or lack of priority”; (2) “Lack of skills to implement guidelines due to lack of education and/or lack of interest in assessing and treating the patients’ psychosocial factors”; (3) “Professional identity as a barrier for implementing guidelines due to participants’ approach and view of their core task of providing biomechanical treatments.” In the following, deviant cases and professions were compared in order to challenge the analysis.

At level three, interpretations of the three tentative categories were discussed with all authors and in two dialogue meetings with three practice consultants from the study’s steering group and researchers with physiotherapist and chiropractor background from M.H.H.s workplace. The practice consultants contributed with good insight into the attitudes, beliefs, and clinical skills of the physiotherapists’ and chiropractors’. Through this abductive process, possible theoretical explanations were hypothesised and tested until a plausible theoretical explanation was found [Citation42,Citation46]. The categories “lack of willingness to implement guidelines” was reconstructed to “scepticism” and the two categories “lack of skills” and “professional identity” were merged and reconstructed to “deep biomechanical professional identity.” Finally, the two categories of barriers to using guidelines in practice were tested on the complete data set to ensure that the categories were grounded in the data.

Ethical issues pertaining to human subjects

According to Danish regulations, the study was not required to undergo an ethical review for approval, as it did not fall within the scope of the Danish Medical Research Involving Human Subject Act (§14). The Regional Research Ethics Committee of Central Denmark was notified of the project (j. no 180924). Prior to the interviews, written and oral information about the study was given to all participants, and written informed consent was obtained. Prior to the observation of patient consultations at the clinics, patients were given written and oral information and told that the observation did not focus on them as a patient, but instead on the management they received from their physiotherapist or chiropractor. No patients refused to participate.

Findings

When asked what barriers the participants experienced when using guidelines in clinical practice, the majority from both professions responded offhand: “None” and they generally considered their practice to adhere with the guidelines. However, based on data from both observations and interviews, the analysis revealed that barriers did exist among these physiotherapists and chiropractors.

Two categories were identified as key barriers: the first category, Scepticism showed how the participants felt sceptical about the use of the guidelines. Scepticism was elaborated on in the two subcategories of validity of the guidelines and applicability of the guidelines. The second category deep biomechanical professional identity, showed how the biomechanical model was deeply rooted in practice and how this identity challenged the uptake of some of the key recommendations in the guidelines. The deep biomechanical professional identity was elaborated on in four subcategories: not my role; lack of skills; lack of interest; and patient preferences. The two categories and subcategories are shown in , which summarises the constructed theory, encompassing the two categories explored.

Figure 1. Category map, showing the constructed theory encompassing the two categories and subcategories with key barriers identified.

First category: “scepticism”

Nearly all participants described the guidelines as a useful tool for supporting clinical decisions in practice. However, many participants also expressed some degree of scepticism about the guidelines, especially the physiotherapists. This scepticism was related to doubts about the validity and applicability of the guidelines. The comparative analysis showed that chiropractors had more trust in guidelines than physiotherapists; however, several chiropractors expressed and demonstrated challenges when applying the guidelines.

Validity of the guidelines

Some physiotherapists believed that the guidelines were developed primarily on the basis of consensus decisions rather than scientific evidence, and therefore would be prone to influence by whoever had participated in the expert working group. These doubts about validity were stated by a female physiotherapist with 14 years of experience:

One could think that the guidelines…well, there has been a person educated within the McKenzie methods as part of the working group, and then its direction-specific exercises that are recommended in the guidelines…Then I think to myself 'yeah right, well, the conclusion depends on who is a member of the working group. (Participant 303)

The participant suspected that the recommendations given in the guidelines could be influenced by whatever physiotherapy treatment concept the expert group members were trained in at postgraduate level (e.g., McKenzie or Mulligan), rather than being based on evidence. Another concern communicated by several physiotherapists was the low level of evidence base of the guidelines. A male physiotherapist with 20 years of experience voiced the following concern:

I think there is something missing in the guidelines. And then they [the working group] may have chosen recommendations that have been found to lack evidence, and then only a few recommendations that are actually evidence-based… quite a lot is said about recommendations lacking evidence… and hardly much about recommendations built on good evidence. (Participant 307)

The view on guidelines lacking evidence hindered the participants’ perception of the guidelines as being a supportive tool for providing evidence-based treatment. Instead, the lack of evidence contributed to a feeling of doubt about the validity of the guidelines, and despondency as to whether it was possible to practise based on guidelines. This feeling of doubt might have caused the participants to have more trust and put more value in their own clinical experience and patient preferences than in the guidelines.

Applicability of the guidelines

Many of the physiotherapists described how they found the guidelines too general to be applicable in practice when managing individual patients, and instead, they used the guidelines as a kind of benchmark. For example, a male physiotherapist with 14 years of experience expressed his view on the guidelines:

So, I think the guidelines are a nice tool to get an overview, but I do not know how much it can actually guide your practice when faced with the individual patient. (Participant 302)

This experience was shared by several physiotherapists, who all voiced the opinion that treatment of patients with LBP is complex, and has to be tailored to the individual patient. The participants found that the guidelines did not provide sufficient guidance for personalised counselling and, therefore, were not applicable in practice, as not all patients need to be given the same advice or treatment. Also, some chiropractors stated that the guidelines were not comprehensive enough, as they could have contained other valid recommendations. Thus, the chiropractors only used those recommendations in the guidelines they found applicable.

The scepticism implied that the participants did not put much value on the guidelines and would rather base decisions on their clinical experience and patient preferences. Hence, scepticism acted as a key barrier to the use of the clinical practice guidelines.

However, one of the physiotherapists (a male with 19 years of experience) appeared as an outlier with regard to this barrier. He described feeling obliged to adhere to the guidelines in his daily practice, in relation to the choice of treatment modalities:

I feel enormously obliged to read what is written [in the guidelines] and also have a critical attitude towards it. But I feel obligated, for example, if tomorrow there was very convincing evidence that acupuncture has a significantly better effect on acute lumbar pain compared to other recommended treatment methods, then I have to learn to provide acupuncture. (Participant 306)

He explained this sense of obligation to the oath taken by a physiotherapist in which one has sworn to practise according to the best evidence available, even if the available evidence is low. This belief and attitude about the guidelines was unique to this participant.

Second category: “deep biomechanical professional identity”

Many participants demonstrated a biomechanical approach in their treatment of patients with LBP, especially the chiropractors, which is contrary to the guidelines recommending a biopsychosocial approach. The following field and interview note exemplifies the finding that key elements from the guidelines were not always reflected in their practice. The note was made during the observation and informal interview of a male chiropractor (Participant 206) with 7 years of experience, performing an initial consultation with a patient having had LBP for 6 months:

At the end of the consultation, the patient is informed that she should go for some small walks and then return and relax. ‘Your back needs rest, it needs to recover’, Participant 206 explains. He also informs the patient that she can use ice or heat for 20 minutes on her back. Participant 206 informs the patient that she must avoid making any lifts that involve twisting her back, and that she must not empty the dishwasher. Later in the consultation, the patient asks if she can sign up for yoga. Participant 206 replies that it is too early, not yet: ‘You will not be able to participate and it will not do you any good’.

After the consultation, MHH asks Participant 206 the reason for advising the patient to avoid emptying the dishwasher and not starting yoga. Participant 206 responds that if patients do too much while receiving treatment, then they are unable to control their recovery curve. He wants them to receive the treatment without being too active as it can provoke their pain.

(Field note and informal interview made during observation of Participant 206)

This field note indicated that the chiropractor understood pain as primarily a biomechanical problem of the back, rather than a biopsychosocial problem being influenced by how the patient perceived her pain. This understanding of pain led to a choice of a passive biomechanical treatment and advice to postpone usual physical activities, which was in contrast to that recommended in the guidelines, where resumption of physical activities is advised as soon as possible. The majority of chiropractors shared this understanding of pain and expressed the belief that LBP was mostly due to structural injuries. Even though the physiotherapists expressed and showed a more nuanced understanding of LBP, several of them still spent a lot of time talking about the pain as a mechanical phenomenon and looking for causal explanations.

“Not my role”

Despite the data revealing a biomechanical focus, especially by chiropractors, they simultaneously acknowledged that the patients’ pain also may have been affected by other factors. For several chiropractors, the challenges of having a biopsychosocial approach were connected to their understanding of what kind of treatment and services they should and could offer a patient as professionals. A female chiropractor with 2 years of experience argued that she did not perceive it as her role to manage the patients’ psychosocial factors. Instead, she believed it was her role to help the patients with biomechanical issues:

As it is right now, the psychosocial factors are not something I really talk about with patients, because I still believe it’s not my task as such… It’s not because I think it’s unimportant at all - on the contrary - but my competencies just do not fit the psychosocial aspect. Then I would rather take care of the biomechanical issues and pass the patients on to someone else who does nothing but talk about psychosocial factors with the patient. (Participant 202)

The participant felt she lacked skills to manage patients’ psychosocial issues, and preferred referring the patients to a psychologist, as she believed the patients would be better off with a specialist. In comparison, all physiotherapists agreed that managing the patients’ psychosocial factors was part of their professional role, and some had improved their skills by taking further education in cognitive behavioural therapy and/or pain science.

Lack of skills from educational institutions

Except for two chiropractors, all participants stated that the educational institutions had a biomechanical focus in the management of musculoskeletal disorders at the time they were enrolled. In their opinion, the institutions generally leave the health care practitioners unprepared for managing the patient’s psychosocial factors, and a trained physiotherapist or chiropractor therefore does not have the necessary skills and knowledge regarding this matter. A male chiropractor with 36 years of experience, expressed:

I think it varies from individual to individual, to what extent you choose to address patients’ psychosocial factors… because you’re kind of in a slightly different ball game if you do…where one could say that with our education [as chiropractors] we are not exactly prepared for it [addressing psychosocial issues]. (Participant 203)

This chiropractor did not feel skilled to manage the patients’ psychosocial factors based on his education. The perceived lack of skills may influence the participants’ treatment choices and approaches, as one may often choose the treatment modalities one feels skilled at using. The three most recently educated chiropractors did, however, find, that there was an increased focus on patients’ psychosocial factors during their education. Still, they expressed that they lacked the ability to apply the theoretical knowledge to practice, which is also seen in the observations where only one chiropractor paid some attention to this subject.

Lack of interest

A lack of interest in managing the patients’ psychosocial factors was evident in the explanations by some chiropractors. A chiropractor with 4 years of experience put into words:

I believe it’s my role to screen and treat patients’ psychosocial factors, but it’s not very easy [laughs easily]. I have to admit that’s not what I think is the funniest thing to treat because it may be a bit hard, and that’s because there are all sorts of other factors that come into play.

It’s not because they’re stupid and tiring patients, but it’s just more fun to help someone when you can see you make a difference… and I think when you succeed, it’s fun, but I think that the success rate is just reached faster by the other patients [without psychosocial issues], and when you are dedicated to helping people, you think it’s awesome when they return after five treatments and say: ‘I’m just feeling really good now’, and then you give each other a high five. (Participant 207)

The participant experienced more recognition when treating patients who recover quickly compared to those with psychosocial risk factors, who more often have prolonged courses of treatment. Moreover, it seems that the time needed to apply a biopsychosocial approach had an essential influence on the participants’ interest in practising it. Several participants from both professions agreed that it would have economic consequences, as it takes more time to practise a biopsychosocial approach.

Patient preferences

Some chiropractors argued that challenges to addressing the patients’ psychosocial factors also have to do with their patients’ preferences. In their experience, patients often expect to receive a biomechanical, passive treatment. A male chiropractor with 22 years of experience voiced:

When the patients seek treatment with a chiropractor or a physiotherapist… well, then it’s the physical discomfort they want us to take care of - and not necessarily the other things. (Participant 208)

Other chiropractors shared this experience explaining that when addressing psychosocial issues, they found that patients were surprised or even seem offended by their questions. The chiropractors did witness that the patients were concerned about whether they (chiropractors) believed it was a mental problem and that it was not “real.” Thus, patient preferences were a barrier for adhering to the guidelines.

Discussion

Our analysis highlighted that the main barriers to using guidelines as part of clinical practice are a scepticism towards the validity and applicability of the guidelines and a deep biomechanical professional identity. We will discuss our findings in comparison with other research and conclude with a discussion of the findings in the light of the self-determination theory [Citation51].

Discussion of scepticism as a barrier

To our knowledge, scepticism is not found in other studies exploring barriers to the use of guidelines by physiotherapists and chiropractors. However, several studies including a review by Slade et al. show that health professionals report relying on experience, clinical judgement, and patient relationship above the use of guidelines, a finding also in our study [Citation31,Citation52]. The scepticism towards doubts about the validity of the guideline development process is also confirmed by other research showing that members of development groups tend to be biased with respect to sex, education, age, procedures, or theories linked to their field of knowledge, and their experience [Citation53,Citation54]. Despite this, the content of the Danish LBP guidelines is consistent with other international guidelines, and in this way, is not unique in its recommendations [Citation16,Citation55]. Also, in a review by Corp et al. the Danish guidelines development process has been assessed to be of high quality, which contradicts the perceived scepticism among the participants [Citation16]. Nevertheless, it is an important finding that must be addressed in a future strategy as the scepticism is a possible explanation as to why especially physiotherapists find it challenging to apply the guidelines to practice.

The perception of the guidelines being inapplicable and incapable of being tailored to individual patients’ needs, as found in our study, is in line with the result from the study by Bishop et al. [Citation56]. They found that the clinicians perceived the guidelines as a rigid treatment pathway that was inconsistent with individually tailored care. The discrepancy concerning the perceived generic approach in the guidelines and the health professionals’ desire to have a more individual approach may indicate that the guidelines lack specification on e.g., how to use the biopsychosocial model and how to deliver patient education so they can use these recommendations to better meet the individual patient’s needs.

Discussion of deep biomechanical professional identity as a barrier

The second key barrier, deep biomechanical professional identity, implies that the recommendations about the adoption of a biopsychosocial approach conflicts with the participants’ professional identity, especially among chiropractors. Contrary to this finding, a recent study by Arnborg Lund et al. described Danish health professionals as having a highly nuanced understanding of nonspecific LBP, which moved beyond a biomedical diagnosis [Citation57]. That study was conducted on a select group of health professionals engaging in a social cognitive behavioural theory programme, and therefore, the results should not be generalised to the broader group of health professionals, including the participants of our study. Likewise, a qualitative study by Cöte et al. showed that even though health professionals have biopsychosocial attitudes and beliefs, it does not necessarily translate into their clinical practice [Citation58]. Also, a qualitative study by Stilwell et al. identified that although the chiropractors understood the value of psychosocial factors, the majority appeared to follow a biomechanical approach in their practice due to a perceived lack of knowledge and skills in the psychosocial domain [Citation59]. The lack of skills to practice a biopsychosocial approach was also stated by the participants in our study and is in line with the existing body of knowledge about barriers [Citation28,Citation30]. The lack of skills in entering a dialogue with patients about psychosocial factors may make the participants anxious, because they have a feeling of going beyond their scope of practice. This is substantiated in previous research, where it is evident that lack of these skills causes anxiety in health professionals to broach patients’ psychosocial factors [Citation60].

The participants’ biomechanical professional identity was furthermore enforced by their expectation that patients prefer biomechanical treatments, and several other studies endorse this concern [Citation29,Citation31,Citation57]. Kamper et al. showed that most patients with chronic LBP expect the management of their condition by physiotherapists to consist of tests or investigations leading to a diagnosis and an explanation of causation [Citation61]. But the study also showed that more than half of the patients wanted to discuss problems in their life, which points to the need for physiotherapists to consider LBP from a biopsychosocial perspective. The discrepancy between the assumed patient-preferred treatment and the current understanding of LBP reflected in the guidelines might challenge the health professionals. Not accommodating the patient’s request might make the participants fear that the patient might seek care from another health care professional and thereby, result in reduced earnings for the participant. However, participants’ assumptions about patient preference might also be associated with the health professionals’ anxiety about addressing patients’ psychosocial factors or be due to the health care professionals’ experience of being acknowledged by patients when they passively “fixed” their patients rather than when they gave them advice and guidance for self-management.

Comparison between the professional groups

Including both chiropractors and physiotherapists in this study provided the opportunity to compare and contrast across the two professions. The comparative analysis showed that there is a difference between the two professions, with scepticism being more evident among physiotherapists and the biomechanical professional identity being more deeply rooted in the chiropractors. To our knowledge, this finding has not previously been described in other studies. The analysis does not explain why the chiropractors have more trust in the guidelines compared with the physiotherapists. But part of the explanation could be that the biomechanical approach is more deeply rooted in the chiropractors’ professional identity because their education is more focused on the musculoskeletal system and biomechanical treatments, whereas the physiotherapists’ education takes a more diverse perspective on functional ability and health [Citation43,Citation44]. Also, the patient characteristics might differ, as patients treated at chiropractic clinics tend to have a higher level of education and are in a better socioeconomic position compared with the average population [Citation62].

Self-determination theory as a theoretical interpretation of data

The interaction of different factors influencing the participants’ use of guidelines can be seen in the light of self-determination theory (SDT), described by Ryan and Deci in 1985 and used in the field of implementation science [Citation51]. Through that lens, the findings can be nuanced to gain a deeper understanding and explanation of the motivational aspects underpinning the use of guidelines by physiotherapists and chiropractors. SDT frames motivation as a continuum moving between amotivation (lack of motivation), extrinsic (controlled) motivation through to intrinsic (autonomous) motivation, of which the third is the most powerful motivation [Citation63]. In our study, intrinsic motivation would be described as the participants finding pleasure in using the guidelines to influence their practice. Motivation is affected by three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness [Citation63].

In our study, using the guidelines may be experienced as a loss of autonomy with respect to making one’s own clinical decisions, especially for those participants doubting the validity and applicability of the guidelines. The finding that guidelines can restrict clinical judgement and challenge professional autonomy was also found in a review by Slade et al. who reported that some clinicians believed that the guidelines were constraining and prescriptive, and designed to control practice [Citation31]. Also, the identified deep biomechanical professional identity contributed to amotivation, as the participants did not believe it to be their role, did not have any interest or did not feel skilled in adopting the recommendations about addressing the patients’ psychosocial factors, which can be described as a lack of psychological need for competence. In addition to autonomy and competence, the intrinsic motivation for using the guidelines in clinical practice is also affected by the need for relatedness in interaction with contextual factors [Citation51]. When some physiotherapists or chiropractors at a given clinic are sceptical about the validity of the guidelines, this scepticism may spread to colleagues, as they may seek shared beliefs in order to create a group identity [Citation63]. Likewise, the participants’ approach and deep biomechanical professional identity, could be based on a recognition of the attitudes of colleagues and patients, and of being part of a social group. Thus, the psychological need for relatedness can be seen as an underpinning factor for the barrier, as social influences can have negative consequences for the use of guideline. Social influences were also found to be important factors for using guidelines in the review by Slade et al. [Citation31]. When aiming at changing health professionals’ behaviour to be more adherent with guidelines, it is important to use implementation strategies that will fulfil the three psychological needs required to elicit the intrinsic motivation.

Strengths and limitations

We conducted and reported this study following the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research guideline. Several factors contributed to the credibility and trustworthiness of the study: it was conducted and the findings interpreted in close collaboration with the co-authors as well as with a steering group consisting of practice consultants from both physiotherapy and chiropractic, which strengthen the validity of our interpretation, and the applicability of the study findings. The grounded theory analysis made it possible to identify not only a list of descriptive barriers but to go deeper into the findings asking why the participants felt sceptical and why they had a biomechanical approach. Furthermore, including both chiropractors and physiotherapists provided the opportunity to look for similarities and differences between the two professions.

A limitation of the study could be that not all interviews were conducted as physical face-to-face sessions as planned, and several observations were cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The data collection was therefore not as comprehensive as planned. However, data from telephone and video interviews did not deviate from the face-to-face interviews and no increased sample size was found necessary. Moreover, previous studies using different methods of data collection in the same study, have not reported meaningful differences in the richness of the data collected [Citation64,Citation65]. Nevertheless, using triangulation (observation and interviews) helped produce a rich description of the data, and theoretical saturation was reached [Citation42].

Although this study was conducted in a Danish context where certain conditions in terms of health care services and welfare systems apply, our findings may be applicable to other settings.

Conclusion

The constructed theory of this study identified two key barriers to the use of clinical practice guidelines among Danish physiotherapists and chiropractors. The theory also contributed knowledge that the barriers differ between the two professions. The physiotherapists, in particular, experienced a scepticism due to lack of validity and a perceived inapplicability of the guidelines. The chiropractors, on the other hand, found it challenging to use a biopsychosocial approach in practice due to a deep biomechanical professional identity. Viewing the findings, the barriers are considerably complex as they are rooted in the beliefs and attitudes, as well as the professional identity, among the health professionals. Addressing the barrier of a deep biomechanical professional identity in a future implementation strategy might be challenging, but nonetheless essential, if the approach to LBP patients’ needs to change, not only in the health professionals’ attitudes and beliefs but also in practice. The future strategy may need to be different for the two professions in order to address the barriers of greatest importance to each profession. However, implementation strategies for both professions could benefit from including motivational aspects in an effort to change the health professionals’ behaviour to be more guideline-adherent by fulfilling the need for professional autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (31.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating physiotherapists and chiropractors for sharing their thoughts and experiences, and allowing us to observe their practice. Likewise, we would like to thank the patients for allowing us to observe them during their treatments. Also, sincere thanks to the steering group of the project (Nils-Bo de Vos Andersen, Bo Albertsen, Henrik Frederiksen, and Jeppe Mølgaard Mathiasen) who helped to ensure that the project stayed on the right path. We appreciate their professional dialogue. Finally, we would like to thank our colleagues who have given important feedback on the analysis process.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858.

- Fullen B, Morlion B, Linton SJ, et al. Management of chronic low back pain and the impact on patients’ personal and professional lives: results from an international patient survey. Pain Practice. 2022;22(4):463–477.

- Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Cross M, et al. Prevalence, deaths, and disability‐adjusted life years due to musculoskeletal disorders for 195 countries and territories 1990–2017. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(4):702–714.

- Danish Health Authority. The Danish healthcare system and The Danish Cancer Society 2016. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2017/Det-danske-sundhedsv%C3%A6sen/Det-Danske-Sundhedsv%C3%A6sen,-d-,-Engelsk.ashx

- Danish Health Authority. Knowledge and evidence 2019. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/da/om-os/saadan-arbejder-vi/viden-og-evidens

- Flachs EE, Koch MB, Ryd JD, et al. The burden of disease in Denmark - diseases. Copenhagen: Danish Health Authority; 2015.

- Schwartz AL, Landon BE, Elshaug AG, et al. Measuring low-value care in medicare. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1067–1076.

- Guerrero Silva VA, Maujean A, Campbell L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological interventions delivered by physiotherapists on pain, disability and psychological outcomes in musculoskeletal pain conditions. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(9):838–857.

- Luna EG, Hanney WJ, Rothschild CE, et al. The influence of an active treatment approach in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13(2):190–203.

- Hanney WJ, Masaracchio M, Liu X, et al. The influence of physical therapy guideline adherence on healthcare utilization and costs among patients with low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156799.

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–72.

- Danish Health Authority. Course programme for low back pain 2012. Available from: https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/2/78902_forloebsprogram_laenderyg.pdf

- Danish Health Authority. National Clinical guideline for the treatment of new-onset low back pain 2019. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2016/NKR-l%C3%A6nderygsmerter/National-klinisk-retningslinje-laenderygsmerter.ashx?la=da&hash=AF45A82DE3A17CD9C3043F2A46538E71AC615257

- Danish Health Authority. National clinical guideline for non-surgical treatment of new-onset lumbar nerve root compression (lumbar radiculopathy) 2018. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2016/NKR-lumbal/National-klinisk-retningslinje-for-lumbal-radikulopati.ashx?la=da&hash=45C3891B2329D7109BB6A47749C9105B24574D28

- Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, et al. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(2):79–86.

- Corp N, Mansell G, Stynes S, et al. Evidence‐based treatment recommendations for neck and low back pain across Europe: a systematic review of guidelines. Eur J Pain. 2021;25(2):275–295.

- Danish Health Authority. National clinical guidelines for the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis 2017. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2017/NKR-lumbal/NKR-Lumbal-Spinalstenose-13,-d-,10,-d-,17.ashx?la=da&hash=66D4F4702895589AB1610CDFC9E14FA755A1AFBB

- Danish Health Authority. Udmøntning af puljen: Nationale kliniske retningslinjer 2017-2020. 2018. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Puljer/NKR-2020/NKR-pulje-2020-puljeopslag.ashx?la=da&hash=3989656E09837636CBF7A1107468FA023457513A

- Bussieres AE, Al Zoubi F, Stuber K, et al. Evidence-based practice, research utilization, and knowledge translation in chiropractic: a scoping review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:216.

- Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. The Lancet (British Edition). 2018;391(10137):2368–2383.

- Zadro J, O'Keeffe M, Maher C. Do physical therapists follow evidence-based guidelines when managing musculoskeletal conditions? Systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e032329-e032329.

- Ryan C, Pope CJ, Roberts L. Why managing sciatica is difficult: patients’ experiences of an NHS sciatica pathway. A qualitative, interpretative study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e037157.

- Lim YZ, Chou L, Au RT, et al. People with low back pain want clear, consistent and personalised information on prognosis, treatment options and self-management strategies: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2019;65(3):124–135.

- Petersen L, Birkelund R, Schiøttz-Christensen B. Experiences and challenges to cross-sectoral care reported by patients with low back pain. A qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):96–96.

- Rossen CB, Høybye MT, Jørgensen LB, et al. Disrupted everyday life in the trajectory of low back pain: a longitudinal qualitative study of the cross-sectorial pathways of individuals with low back pain over time. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2021;3:100021.

- Cowell I, O'Sullivan P, O'Sullivan K, et al. Perceptions of physiotherapists towards the management of non-specific chronic low back pain from a biopsychosocial perspective: a qualitative study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;38:113–119.

- Synnott A, O'Keeffe M, Bunzli S, et al. Physiotherapists may stigmatise or feel unprepared to treat people with low back pain and psychosocial factors that influence recovery: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2015;61(2):68–76.

- Driver C, Kean B, Oprescu F, et al. Knowledge, behaviors, attitudes and beliefs of physiotherapists towards the use of psychological interventions in physiotherapy practice: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(22):2237–2249.

- Holopainen R, Simpson P, Piirainen A, et al. Physiotherapists’ perceptions of learning and implementing a biopsychosocial intervention to treat musculoskeletal pain conditions: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Pain. 2020;161(6):1150–1168.

- Alexanders J, Anderson A, Henderson S. Musculoskeletal physiotherapists’ use of psychological interventions: a systematic review of therapists’ perceptions and practice. Physiotherapy. 2015;101(2):95–102.

- Slade SC, Kent P, Patel S, et al. Barriers to primary care clinician adherence to clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(9):800–816.

- Schers H, Wensing M, Huijsmans Z, et al. Implementation barriers for general practice guidelines on low back pain a qualitative study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(15):E348–353.

- Zadro JR, O'Keeffe M, Allison JL, et al. Effectiveness of implementation strategies to improve adherence of physical therapist treatment choices to clinical practice guidelines for musculoskeletal conditions: systematic review. Phys Ther. 2020;100(9):1516–1541.

- Flodgren G, Hall AM, Goulding L, et al. Tools developed and disseminated by guideline producers to promote the uptake of their guidelines. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(8):Cd010669.

- de Souza FS, Ladeira CE, Costa LOP. Adherence to back pain clinical practice guidelines by Brazilian physical therapists: a cross-sectional study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(21):E1251–E1258.

- Amorin-Woods LG, Beck RW, Parkin-Smith GF, et al. Adherence to clinical practice guidelines among three primary contact professions: a best evidence synthesis of the literature for the management of acute and subacute low back pain. J Can Chiropract Assoc. 2014;58:220–237.

- Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C, et al. Tailored interventions to address determinants of practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(4):CD005470.

- Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):189–189.

- Taylor SL, Dy S, Foy R, et al. What context features might be important determinants of the effectiveness of patient safety practice interventions? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(7):611–617.

- Husted M, Rossen CB, Jensen TS, et al. Adherence to key domains in low back pain guidelines: a cross-sectional study of Danish physiotherapists. Physiother Res Int. 2020;25(4):e1858.

- Brockhusen SS, Bussières A, French SD, et al. Managing patients with acute and chronic non-specific neck pain: are Danish chiropractors compliant with guidelines? Chiropr Man Therap. 2017;25:17.

- Kathy C. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London: SAGE; 2014.

- University of Southern Denmark, bachelor’s programme in Clinical Biomechanics 2014. Available from: https://sdu.azureedge.net/-/media/files/information_til/studerende_ved_sdu/din_uddannelse/klinbiomek/aktuel_studieordning/bachelorstudieordning_klinisk_biomekanik.pdf?rev=5fcf063edff749038b57230b0f92c56f&hash=B859489B6F6D400190708B82DA801675

- College VU. Study Programme VIA The Physiotherapist Education 2022. Available from: https://www.via.dk/-/media/VIA/uddannelser/sundhed/fysioterapeut/dokumenter/semesterbeskrivelser/Studieordning_2022.pdf

- Danish Health Care Act §66 and §67 Valby: Schultz Information; 2010. 8th edition. Available from: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2019/903

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 4th ed. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE; 2019.

- Wagner HR. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago (IL): Aldine Publishing Company; 1967.

- Wilson HS, Hutchinson SA. Triangulation of qualitative methods: Heideggerian hermeneutics and grounded theory. Qual Health Res. 1991;1(2):263–276.

- Farooq MB, de Villiers C. Telephonic qualitative research interviews: when to consider them and how to do them. MEDAR. 2017;25(2):291–316.

- Ward K, Gott M, Hoare K. Participants’ views of telephone interviews within a grounded theory study. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(12):2775–2785.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. 1st ed. New York (NY): Springer US; 1985.

- Zadro J, Peek AL, Dodd RH, et al. Physiotherapists’ views on the Australian Physiotherapy Association’s Choosing Wisely recommendations: a content analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e031360.

- Richter Sundberg L, Garvare R, Nyström ME. Reaching beyond the review of research evidence: a qualitative study of decision making during the development of clinical practice guidelines for disease prevention in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):344–344.

- Michie S, Berentson-Shaw J, Pilling S, et al. Turning evidence into recommendations: protocol of a study guideline development groups. Implement Sci. 2007;2(1):29–29.

- Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(11):2791–2803.

- Bishop FL, Dima AL, Ngui J, et al. Lovely pie in the sky plans: a qualitative study of clinicians’ perspectives on guidelines for managing low back pain in primary care in England. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(23):1842–1850.

- Arnborg Lund R, Kongsted A, Bäcker Hansen E, et al. Communicating and diagnosing non-specific low back pain: a qualitative study of the healthcare practitioners perspectives using a social diagnosis framework. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52(3):jrm00036.

- Côté A, Durand M, Tousignant M, et al. Physiotherapists and use of low back pain guidelines: a qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(1):94–105.

- Stilwell P, Hayden JA, Des Rosiers P, et al. A qualitative study of doctors of chiropractic in a Nova Scotian practice-based research network: barriers and facilitators to the screening and management of psychosocial factors for patients with low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(1):25–33.

- Richmond H, Hall AM, Hansen Z, et al. Exploring physiotherapists’ experiences of implementing a cognitive behavioural approach for managing low back pain and identifying barriers to long-term implementation. Physiotherapy. 2018;104(1):107–115.

- Kamper SJ, Haanstra TM, Simmons K, et al. What do patients with chronic spinal pain expect from their physiotherapist? Physiother Can. 2018;70(1):36–41.

- Association DC. Profile of the Danish chiropractor patient 2014. Available from: https://www.danskkiropraktorforening.dk/media/1367/patientundersoegelse-v2-2014.pdf.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78.

- Aziz MA, Kenford S. Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews in assessing patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(5):307–313.

- Bampton R, Cowton C. The E-interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung. 2002.