ABSTRACT:

Purpose

Mental ill health and sensory processing difficulties often limit participation in everyday life for adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Interventions using technology such as virtual reality (VR) are increasingly accessible and may mitigate these difficulties. Understanding what contributes to the successful implementation of novel interventions is important for future use and evaluation. This study aimed to explore the feasibility of implementing a VR sensory room for adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities, their carers and support staff and to explore future iterations of the product and process.

Materials and Methods

Thirteen stakeholders who participated in a pilot trial of a VR sensory room were interviewed. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim for thematic analysis.

Results

Eleven themes were identified which indicated that adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities found the VR sensory room to be mostly acceptable and enjoyable with usage largely consistent. Individual variation and support requirements were highlighted for each user. Future use may require modifications to the headset, in-built customisation options as well as buy-in and training for support staff.

Conclusions

The VR Sensory room is a promising tool to support adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities and results warrant further scaled research into the impact of this tool on outcomes for adults with disabilities.

Whilst adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities may experience sensory processing difficulties which impact their everyday life, there is a paucity of interventions to address these difficulties.

Implementation studies offer the opportunity to explore how evidence-based interventions may be implemented to facilitate the best outcomes.

A Virtual Reality Sensory Room may offer an innovative alternative to a traditional sensory room for adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities where implementation is well supported.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

People with neurodevelopmental disabilities frequently experience marginalisation and exclusion from social participation, including challenges to key components of life like employment, education and health care [Citation1]. This social exclusion can exacerbate issues for those with disabilities by compounding inequality, vulnerability and social disadvantage [Citation2]. Likewise, the inequity experienced by individuals with disabilities is evident in the disproportionate burden of mental illness for members of this population; including, but not limited to, anxiety and depression [Citation2]. For instance, the prevalence of internalising (anxiety and depression) and externalising (aggression and non-compliance) problems in people with disabilities has been found to be up to four times higher than that experienced by those within the general population [Citation3].

Importantly, such issues can often in part be the result of disordered sensory processing [Citation4,Citation5] which negatively impacts a person’s participation in everyday life, social relating [Citation6] engagement with education [Citation7] and general quality of life [Citation8]. Sensory processing disorders are a broad term describing difficulties registering, organising and using incoming sensory input in a functional way through touch, vision, auditory and movement [Citation9]. Sensory processing difficulties are most commonly diagnosed in children, with prevalence reportedly ranging between 1 in 6 to 1 in 20 children [Citation10]. Difficulties with sensory processing can persist into adulthood; for instance, they are thought to impact up to 94% of autistic adults [Citation11]. People with disabilities, and particularly autistic people, can experience greater severity of sensory processing difficulties [Citation12].

Timely and effective prevention and treatment programs to address sensory processing difficulties are critical to reducing the emotional and financial impact of this symptomatology for both affected individuals and their families or carers [Citation13]. The inherent vulnerability of this population underscores the importance of mitigating the impact of such disadvantage through the implementation of evidence-based, high-quality programs which are tailored to meet their specific needs.

Even evidence-based programs will have a minimal impact unless stakeholders such as health care systems, organisations and care professionals (such as occupational therapists, psychologists and behaviour support clinicians) willingly adopt them into practice. Moreover, the individual users themselves must find these programs suitable. The translation of research findings into practice is often unpredictable and can be a slow and disorganised process [Citation14]. To ensure the feasibility and efficacy of a proposed intervention, studies that evaluate implementation are key to identifying factors that may enhance or impede its effectiveness and real-world application [Citation15]. Implementation studies offer the opportunity to enhance the understanding of evidence-based interventions and maximise the likelihood of achieving meaningful outcomes [Citation16]. The Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom advises that all interventions should have their feasibility thoroughly tested before the commencement of larger trials [Citation17], with the assessment of the suitability of interventions for people with disabilities of particular importance given their pre-existing disadvantage and vulnerability [Citation18].

Interventions to address sensory processing difficulties for people with disabilities through the utilisation of physical sensory rooms (often termed ‘Snoezelen rooms’) are common within the research literature [Citation19–22]. Such interventions may include a range of different sensory items arranged within a set space. Activities and equipment in the room may include visual stimuli such as bubble tubes, projected visual effects [Citation23,Citation24]. Auditory input is also utilised such as nature sounds or dimmed music and tactile input such as vibrating massagers [Citation25]. Physical sensory rooms have been implemented in a variety of environments from schools to prisons and psychiatric facilities for decades [Citation26–28], often with the purpose of self-management of distress and assistance with emotional [Citation29] or behavioural regulation [Citation20]. While results have varied and must be generalised with caution, sensory rooms have been found to decrease anxiety [Citation30] as well as reduce aggression and maladaptive behaviours [Citation24,Citation31].

Whilst study results on the use of physical sensory spaces are promising, their creation and utility present creators, operators and users with several logistical issues; not least of which is the requirement of a dedicated location in which to house the sensory room [Citation32]. This could potentially limit access to a broad range of users who might otherwise benefit from such intervention and the use of these spaces, particularly people with disability who may have limited access to the resources required to attend such venues. Additionally, the social changes caused by the global pandemic since early 2020 have brought to the fore limitations related to physical access, increased digitisation of everyday activities and the need to be able to perform tasks and interact remotely [Citation33]. Herein lies an opportunity to capitalise on the rise of technology, such as Virtual Reality (VR), as a panacea to participatory challenges such as sensory processing difficulties.

The ability to create effective interventions for sensory processing difficulties with the use of VR technology presents a promising area of growth [Citation34]. VR offers a vast environment of computer-generated stimuli in which users can immerse themselves. Developers may be able to customise experiences to individual sensory needs through implied touch, hearing and vision [Citation35], and the implementation of virtual sensory rooms has the potential to revolutionise the implementation of sensory rooms. A number of limitations have been noted with physical sensory rooms including set up and equipment costs and the need for a fixed location. VR overcomes these limitations by offering portable equipment and on-demand set up as well as programs that allow numerous options for tailored, personalised experiences and environments that can be designed to suit desired outcomes. In general, VR has shown emerging positive outcomes for improvements in emotional regulation [Citation36], anxiety [Citation37], functional skill development [Citation38] and decision-making in people with intellectual disabilities [Citation39]. However, the potential benefits of this technology are new and remain largely unexplored. The Evenness VR Sensory Room, which is the focus of this study, was developed by Devika Opsco (Devika, Wollongong, Australia).

Utilising a qualitative approach with semi-structured interviews, this paper aims to first explore the feasibility of an intervention using Evenness VR Sensory Room technology for people with disabilities. Second, this paper aims to identify improvements to future iterations of the product and process. This study was conducted alongside a small pilot study of the efficacy of the Evenness VR Sensory Room for people with disabilities (see Mills et al. [Citation40]) which showed improvements in anxiety and depression for adults with disabilities following Evenness use.

Materials and methods

The current small-scale study represents a feasibility study [Citation41] of the Evenness VR Sensory Room and included participant perceptions of three components: demand, acceptability, and implementation. Demand refers to the extent that a program will be used by participants whilst acceptability depicts whether the program is satisfactory for participants. Finally, implementation refers to the degree to which a program is delivered as intended. Qualitative analysis allows a detailed examination of the feasibility of pilot interventions prior to conducting larger studies [Citation42].

Design

A pragmatic qualitative descriptive approach underpinned this research. Pragmatic approaches are commonly utilised when evaluating intervention implementation, ensuring a fit between answering the research aims whilst allowing for the practical constraints of the research [Citation43]. This approach often involves semi-structured interviews exploring the perspectives of participants, linking this with set research questions and existing knowledge in the field [Citation44]. Interview schedules were designed to gather the perspectives of participants, their carers and staff about: the benefits for the individual participants and the participating organisation; features that influenced the attainment of benefits; implementation and recruitment issues; enablers and barriers for implementation; and how the Evenness VR Sensory Room compared to the use of a physical sensory room.

Participants

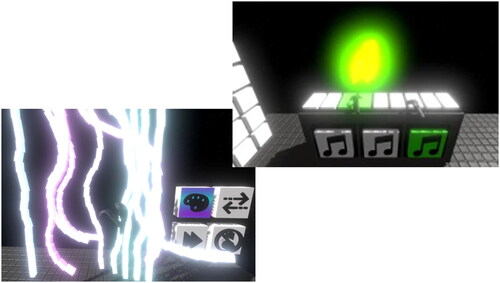

Participants were recruited as part of a pilot evaluation of the VR Sensory Room using purposeful sampling. For this study, a total of eight interviews were conducted across 13 stakeholders including five people with disabilities and their carers; and three staff members from the organisation who coordinated the VR project implementation and facilitated the participants’ use of the VR Sensory Room. Participants were selected to represent a cross section of the total of 31 users of the VR sensory room encompassing people with a range of disabilities and VR sensory room usage. describes the characteristics of participants with disabilities and outlines their VR Sensory Room usage experience in terms of time and duration and how many hours per week they spent with their carer. Carers included a paid worker or a family member who spent time caring for the participant over the year preceding the study. Carers were included as they knew the participant and their support needs quite well and were present at the interviews at the request of the participant. Staff comprising two females and one male gave their perspectives on the implementation of the VR sensory room based on their observations coordinating the VR Sensory Room program. shows the VR headset as worn by participants with hand controllers and shows the inside of the VR Sensory Room as experienced by participants.

Figure 1. Evenness VR Headset.

Figure 2. Inside of the Evenness VR Sensory Room.

Table 1. Details of Qualitative Interview Participants with Disabilities.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the Western Sydney University Human Ethics Research Committee (HREC) (Approval Number H1385, June 2020) prior to participant recruitment. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research for Australia (2018). All participants gave written informed consent with some participants with disabilities gaining support from a trusted carer where necessary.

Participants then were offered the chance to use the VR system for a period of six months. shows the VR system as used by participants. shows a graphic of the inside of the Evenness VR Sensory Room as seen by participants.

A selection of participants was then recruited for qualitative interviews to explore their perspectives relating to demand, acceptability, and implementation following their involvement with the VR Sensory Room over the previous 5 months. The interview schedule was constructed based on protocols for designing feasibility studies [Citation38]. More specifically, to measure demand, participants were asked about intentions and motivations for initial use; whilst acceptability was measured via questions that captured participants’ satisfaction with the VR Sensory Room and intended continual use as well as perceived effects. Finally, implementation was measured with participants asked to comment on the resources required and factors affecting implementation.

Interviews were conducted on the premises of the disability organisation where the VR Sensory Room was delivered and were conducted individually with staff and with dyads comprising participants with disabilities and their carers. To assist people with disability to fully participate in the interview, the interview was conducted in the same location as the Evenness VR Sensory Room to provide a visual prompt of the topic; simple language was used; and a trusted carer was in attendance with their permission. Interviews ranged from 4 min to 40 min with an average interview length of 15 min.

Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and these transcripts formed the data set for analysis. Reflexive thematic analysis was utilised to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the data [Citation45].

Analysis was conducted by two independent researchers (CM and DT) following Braun and Clarke’s six steps for thematic analysis [Citation46]. First researchers read each of the transcripts several times in order to immerse themselves in the data. Through this process, initial codes were developed. Coding was completed by identifying and grouping implicit and explicit meanings together from the text and using these groupings to form themes [Citation47]. Developing themes is described by Braun and Clarke as an active process comprising linking codes together and determining their relationship to the research questions [Citation46]. Detailed field notes were kept during this process. Following the development of initial themes, the two independent researchers met together a number of times to discuss, review and compare themes. This process allowed for ‘researcher triangulation’ where two skilled researchers independently analysed the same data set in order to overcome any bias present with a single researcher [Citation48]. Findings thus emerged through consensus. Here researchers were able to determine the significance of themes and overall findings and refine the final themes. Themes are presented in relation to the overarching aim of the project in relation to describing demand, acceptability, implementation of the VR sensory room and suggested improvements. An example of the coding scheme included:

Broad Theme: Feasibility

Theme 1: Demand

Code: New technology experience

Theme 2: Acceptability

Code: Most enjoyed and enjoyment increased

Code: VR Headset reduced enjoyment and usage

Results

Findings are discussed in relation to key research aims of exploring demand, acceptability and implementation. In presenting the findings, themes are presented under each main component of the implementation study with quotes provided to demonstrate evidence from the data. An overall summary of themes is presented as .

Table 2. Summary of Themes.

Demand: Will evenness be used?

Theme 1: Participation is motivated by the desire to engage with a new experience that involved technology

Staff and people with disability explained that users were eager to engage with the Evenness VR Sensory Room as it presented a new opportunity, one that was founded in technology which was already enjoyable and it could potentially lead to some benefits. One staff member noted:

“It’s obviously something different. It’s new. It’s technology. It’s innovative. So because of that I think there were a lot of families who were interested.” (Staff 2).

“Because it’s just a new experience and actually it was the best thing for me, ever. I didn’t know what to expect at first but just reading a bit up about it … And it’s amazing. It was something good as well actually and I'm so grateful to have had the opportunity to have a go at it actually.” (Participant 29).

Acceptability: is it satisfactory for participants?

Theme 2: the majority of users enjoyed using the evenness VR sensory room and enjoyment increased over time

Staff reported that the majority, although not all, VR users enjoyed using the Evenness VR Sensory Room, and were encouraged to participate by their carers and families. Their enjoyment, confidence and comfort level reportedly increased over time as one staff member said:

“I think participants are getting a lot more comfortable in using it, so that’s the main thing that I'm seeing… And they’re now quite happy to go in there and increase their time in there as well. So we’re seeing an increase in time, every two weeks, which is great.” (Staff 1).

“It was daunting at first when I said I was only focusing on one thing and then, when that guy just said to say, “Have a look at this and have a look at that,” you go, “Oh, yeah.” … I just seen this one thing there and then all sudden, I ran and the next minute up there, … and the second time was, as I said before, it was more confident, actually more confident.” (Participant 29).

“So at the start, she was really, really excited. She was enjoying it. She was in there for like five-minute periods. I don’t know what happened along the course of the six months, but now she doesn’t want to come here.” (Staff 1).

“Participant 27: Well, there’s … piano. Carer: The piano? You like playing the piano. Participant 27: Yeah. Carer: And what else?, Participant 27: More fishies. Carer: Do you see fish in there? What else is in there that you liked? You liked the music? Participant 27: Yeah.”

Theme 3: the VR headset was not suitable to some participants and reduced enjoyment and usage

Where users reported dissatisfaction with the VR Sensory Room, the mostly commonly cited reason was user’s reluctance to place the VR Headset on. As described by a carer:

“There’s a barrier for a lot of other participants being able to put the headset on. They don’t like the feeling of having it on their head, it’s quite intimidating for them.” (Carer of Participant 2).

“I think a lot of the barrier is the big goggles, because a lot of the sensory part on the head is an issue because you’re tracking them in these confined, autistic children or adults that’s confined, that’s a sensory thing.” (Carer of Participant 8).

“So I think the first issue that I have seen when I have been here to see them, is that obviously getting the headset on, once they’ve finally got it on, and over time they’ve been able to become more used to the sensation of putting the headset on themselves.” (Staff 2)

“At the start, we had a majority, so maybe about 10 to 15 that wouldn’t put the headset on at all. But we’ve made some really good progress with them, just from consistency every time that they come.” (Staff 1)

Implementation: is it delivered as intended?

Theme 4: Individual experiences within the VR sensory room varied according to individual preferences as intended

Reports from interview participants indicated the experiences within the Evenness Sensory Room varied for each user, led by their personal preferences, as described by one staff member:

“I think it varies as to what they actually use when they’re in there, because obviously there’s the whole range of different items they can look at, once they’re in there. Some just like the colours, the lights, the sounds. Others will be more glued to a specific within the sensory space.” (Staff 2)

Theme 5: Delivery consistently included repeated practice, demonstration, verbal prompts and the presence of a support person

Implementation was largely consistent and usage increased as a user became more familiar with the VR Sensory Room, as described by a staff member:

“We tried to keep that standard when they come in … So when they came back for multiple uses, we had to obviously help to desensitise them, just on the using of the space. We have seen that progress with a number of our participants, and I think the time data will show that they’re only in for two seconds to start with, but they might be in for 15 seconds, and then 30 seconds, and longer later on.” (Staff 2)

“Yeah, he can go in there and he knows where to go now. Now he’s familiar with the space.” (Carer of Participant 5).

“I think, yes, I do think the support for maybe the first four times would be good because it’s a new technology, learning, I think it’s good to have someone to show you how it works. And to be with you in that experience too…” (Carer of Participant 29).

“It’s more we just show them what to do ….So I'll put the headset on their head, and then I'll put the controllers … put the controllers in their hand, obviously, telling them what’s happening the whole time, saying I'm about to put the controllers in your hands. And then I'll hold their hands whilst they’re holding the controllers. And I'll help them walk around and reach out to touch everything and explain what all the buttons do… now that we’re six months into it, they’re capable of doing it by themselves.” (Staff 1)

Participant 29, a 61 year old with intellectual disability reiterated the importance of being with others upon VR usage: “But I myself, if I wanted to come down myself, I'll be frightened. I'm scared. But … this group we’re in now, … group was marvellous to have this opportunity to do something.” (Participant 29)

Support needs were also highlighted by a carer of a 26-year-old with a variant of Klinefelter Syndrome who used a wheelchair for mobility stated: “You will need to have someone dedicated to the VR because they do need help to get it going. And some of the participants as well will need support whilst in there, especially if they’re in wheelchairs, and they’re also the ones that are quite uncomfortable with walking around. They sometimes like you to help them so you definitely need a carer.” (Carer of Participant 2).

With regard to implementation, user, carer and staff accounts support the consistency of delivery, with delivery founded on user-led experiences, repeated practice, demonstration, verbal prompts and the presence of a support person.

Future iterations: Improvements to product and process

Following collation and categorisation of demand, acceptability and implementation of Evenness, interviewees presented some useful suggestions about how to improve the future implementation, both in terms of the product and the process. The main suggestions are presented below.

Theme 6: the headset should be modified or removed

With the headset cast as the main barrier to acceptability and thus usage, staff, and one carer, identified the need to modify the headset by changing its colour, or making is less bulky and similar to wearing glasses, or remove the need for the headset completely in the technology, as highlighted by two of the carers: “We could probably have a look at brightening up the headset a little bit so it’s not as dark and intimidating because it’s black, it’s quite intimidating.” (Carer of Participant 2). The carer of participant 8, a 20-year-old with intellectual disability, who had difficulty accessing the HMD because they wore glasses also stated: “So that could be some way you could not make them so big or I don’t know, like a pair of glasses like this, but it just has a little – I don’t know how they could work it, just maybe not so big and have to have it on their head.” (Carer of Participant 8).

A staff member was in agreement with this, highlighting the potential issues with the black head mounted display (HMD) that was part of the VR Sensory Room usage. “I think even if the goggles were more glasses not – they’re quite big and bulky at the moment. I think they would be more open to just putting on some glasses, because it is quite intimidating. It’s black. It’s very big and bulky. So even if it was glasses, or if it was a screen that they could look at, that would probably be a lot more successful.” (Staff 1)

Theme 7: Assign, train and build awareness of staff across the organization

Future implementation will need to consider the workforce implications and strategies to seed success at an organisational level. While information about individual usage was provided by people with disabilities and their carers, much of the organisational level considerations were highlighted by staff who participated. Comments suggest that staff availability and capacity plays an important role at various points within the organisation. First, a support person is required to accompany the user as reported by one staff member: “I think they definitely need the support person with them at least for the first few times. And then you can gauge whether or not they have the independence to go in there by themselves. But there’s not much that you need to run it really.” (Staff 1)

Second, staff motivation was highlighted as a consideration for Evenness implementation. Motivation was enhanced when staff perceived there may be benefits for users, suggesting a positive communication strategy across the staff is central to implementation:” I think the staff are motivated to use the VR space, because they’ve also seen the benefits to the participants they’re supporting.” (Staff 2). A staff member also reported: “So I think we need to adjust the way in which we’re getting people involved in it so that the staff are more willing to be involved in the use of it.” (Staff 1)

Third, to ensure the sustainability of implementation there should be multiple staff who have the capacity to use the Evenness VR Sensory Room as reported by one staff member:”If those participants who are onsite want to come in and use it, then those staff who are supporting those clients need to be able to support them to turn the system on, get it all up and running and ready to go.” (Staff 2)

In addition to staff supporting Evenness use with participants, one staff advocated for the appointment of an organizational leader or champion to support organization-wide usage: “It would probably be great for there to be a VR specific position for someone who could help with the implementation and rollout to make sure it goes – we’re not setting everyone up for failure… So if it’s rolled out correctly, it’s something that could be very positive for the company.” (Staff 1). Organisation-wide roll-out of a technology-based program such as Evenness necessitates the need for timely IT assistance: “I think with any sort of IT or computer, having access to, if there was – or a frequently asked questions, or a problem-solving answer to the process.” (Staff 2)

Theme 8: Adopt wireless portable VR

Staff advised that user accessibility and benefits would be enhanced if the portable version of the Evenness VR Sensory Room was adopted, and the cost would also be reduced. For the pilot VR trial, the VR headset was only available in one location, which was highlighted by the carer of Participant 5 as a barrier: “Probably just getting here to be able to use it, because he’s actually from another centre, so we have to organise time to get him here but that’s probably it. So the accessibility” (Carer of Participant 5).

One of the staff suggested that a wireless portable VR system would overcome this barrier: “If you have the wireless one, which is quite good, then you don’t need to have a space that’s solely for the virtual reality room, because the wireless one can be moved around and quickly” (Staff 1). This was echoed by Staff 2: “Wherever a participant goes it could come with them”. (Staff 2)

Theme 9: Incorporate individual behaviour or sensory support strategies for users

Two staff members recognised that Evenness may form part of a user’s individual positive behaviour support or sensory support program and that relevant professionals could be involved in the future delivery of the Evenness VR Sensory Room in order to increase the participation of the user and to maximise benefits: “And it’s also important for the participant to learn that when they’re feeling heightened, that they can self-regulate themselves, and they can go to that space without having to involve anyone else, so it’s very important.” (Staff 1) In agreement with this, another staff member said: “I think that definitely there could be a role to play from a clinical space, whether it be a speech therapist, and OT, someone along those lines who can prepare social stories and prepare someone for the use of the space.” (Staff 2).

Theme 10: Incorporate an inbuilt measurement of anxiety

Staff and carers stated that the ability to collect real time outcome data about the impacts of Evenness use on the participants would be an important means of using evidence to inform their practice and understand the needs of the participants. This was highlighted by one of the carers who spoke about difficulties determining a participant’s response, particularly when they may be minimally verbal or non-speaking: “I think you’d have to go off body language and visual, like their senses, because they’re scared, they’re hesitant or, if they’re excited, they’re excited after they finish it. So I think you have to read their body language to understand if they’re really liking it…” (Carer of Participant 8). Further, one staff member reported: “So it will be good if we can implement the new headset that has the anxiety testing and that in there, because then we’re not just guessing.” (Staff 1)

Theme 11: Incorporate technology that adapts to user’s interests

One staff member identified that a positive development may be to design the technology so that it could be tailored to the user’s interests, given there was a wide range of exhibited sensory preferences whilst in the room. For example, Participant 27 was focussed on the sound aspects of the experience in their interview: “Come and turn on the music and just calm” whereas Participant 29 described the visual aspects “Just looking up in the sky, seeing the stars up there”. This variation in preferences was described by Staff #2 who suggested that the technology could align with a user’s interests: “I think if someone’s more interested in the lights, you know, lights versus the sounds, or the sounds versus the lights, having more items within the space that adapt to allow sound versus something … But just trying to correlate what their interests are, how we can make, more align it with either the sound of the light or what they’re actually interested in in that sense.” (Staff 2).

Interview findings provided valuable suggestions for improvements to both the VR Sensory Room itself, such as improvements to the headset and portability, as well as the personnel support required to maximise delivery and potential impact for the user.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the demand, acceptability and implementation of the Evenness VR Sensory Room as well as describe identified improvements to the product and process. As the first study to consider the feasibility of the Evenness VR Sensory Room, the study findings have important implications for future clinical work as well as subsequent efficacy studies investigating outcomes for users.

From the interview data, eleven themes were identified: one theme in relation to demand, two themes relating to acceptability, two themes relating to implementation and six themes offering suggestions for improvements. Findings suggest that demand and acceptability was strong, apart from some resistance to the VR Headset, and implementation was largely consistent. The study findings revealed the need to address the suggested improvements to the product and wrap around personnel and processes to enhance both clinical application and readiness for efficacy trials.

Several key findings were identified and are discussed in relation to research aims. First, the Evenness VR Sensory Room was in demand and users were motivated to engage with novel technologies. Findings align with previous studies describing VR as motivating and interesting for adults with disabilities. Lotan, Yalon-Chamovitz [Citation49] utilised an activity-based VR system with modified games such as soccer and drums. They reported that VR may provide an opportunity for motivating activities to entice participation and engagement in adults with disabilities, which may be important given this group is at increased risk for a sedentary lifestyle [Citation49]. Similarly, a survey of special educators on classroom-based VR usage reported that motivating students was the most common reason for implementing VR in the classroom for students with disabilities [Citation50].

Second, mixed findings were observed in relation to acceptability of VR, in particular the use of the headset with some participants reporting a positive experience from full immersion with a head mounted display (HMD), and others refusing to wear the HMD. Use of VR with a HMD may enable full immersion in a ‘VR world’ and function as a safe, predictable environment for young people with disabilities [Citation38,Citation51], where sensory input can be controlled [Citation35]. Advances in HMD technology have increased availability and affordability of full immersion VR for users [Citation52]. However, clear concerns were raised in the present study regarding the feasibility of using a HMD for adults with disabilities in terms of acceptability, with several participants refusing to engage with the HMD. Similar concerns are echoed in previous studies citing concerns with possible cybersickness [Citation51], and discomfort for autistic individuals [Citation38,Citation53] and others with disabilities [Citation52]. To mitigate some of these concerns, Schmidt, Newbutt [Citation52] suggested that a structured process of gradual acclimation to a HMD may support and empower autistic participants to use the HMD successfully. This was observed to some extent in the present study where some participants were able to practice HMD usage gradually over time, increasing acceptability. Careful monitoring of comfort may be necessary while using HMDs in VR practice and research for people with disabilities [Citation38].

A third finding was that implementation of the Evenness VR Sensory Room was individualised to each participant and was facilitated by repeated practice, verbal prompts and the presence of a trusted support person. The individual nature of sensory processing difficulties in people with disabilities, particularly autism is well documented in literature [Citation54], and sensory interventions may be individualised in nature to reflect this [Citation55]. Individual support requirements described in the present study are discussed in literature, particularly when implementing novel technology with people with disabilities. Schmidt and colleagues [Citation52] highlighted the importance of key support people in successful implementation of VR. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of prompting to support participation of adults with disabilities [Citation56], however, appropriate prompting may vary between participants [Citation57].

Several improvements were suggested for advancing the implementation of the Evenness VR Sensory Room. Modification or removal of the headset may support implementation for some participants, while implementation may be facilitated by increased availability of portable VR equipment. The present study found that the Evenness VR Sensory Room mostly was delivered as intended but participants highlighted staffing and resourcing as areas of suggested improvement. At an organisational level, the present study indicated that successful implementation of Evenness may require a strategic approach with buy in across the organisation which necessitates ongoing training, trouble shooting and resources for multiple staff members, including the appointment of a ‘champion’ to support the work. Previous studies have echoed the importance of technical support and training to facilitate VR usage for adults with disabilities [Citation49] and highlighted the importance of coordination of staffing support across an organisation [Citation52]. A survey of special educators by Yakubova, Kellems [Citation50] cited lack of training and technical support as a barrier to successful implementation of VR for young people with disabilities in a school setting.

Programs within Evenness could be customised to the needs of individual users whereby the technology learns from and is tailored to the individual user. Programs could also offer the capacity for inbuilt measurement of physiological responses such as heart rate or blood pressure [Citation58] or electrodermal activity (EDA). In a small study by Pfeiffer, Stein Duker [Citation59], EDA was measured when autistic children used noise cancelling headphones and may offer a method of evaluating the impact of Evenness on individual participants as part of a potential clinical intervention and as part of a larger group evaluation study. Future iterations could incorporate the perspectives of clinicians who may provide clinical interventions to those with disabilities to explore the potential for Evenness to be used as a clinical intervention. Previous literature has highlighted the possible clinical utility of VR interventions in relation to behavioural interventions for autistic children [Citation35] and depression and anxiety treatments for adults with mood disorders [Citation58]. Bradley and Newbutt [Citation51] highlighted that future research into VR interventions should include the perspectives of clinicians.

Study limitations

This study included the perspectives of a small number of participants who used the Evenness VR Sensory Room. Study participants primarily had intellectual disability and/or autism and this may not be representative of other disability groups. This study adopted a pragmatic approach, adopting thematic analysis for a small number of participants. It is possible that a different type of qualitative approach with a larger number of participants may have yielded different findings. Although the study methodology was founded on gathering the perspectives of people with disabilities and strategies such as visual prompts of the VR and presence of carer support was used, further supports could have bolstered their contribution (for example, capturing non-verbal responses) to gather feedback.

Clinical implications

This study found that a VR Sensory Room was novel, in demand and may have utility for adults with disabilities. Clinical use of the VR Sensory Room may require the modification or removal of the HMD for some participants and graded exposure for other participants. Clinical utility may require specific resourcing from an organisational point of view including additional resources in staffing, technical support, provision and maintenance of hardware and software to support implementation.

Future research could include a larger scale experimental study with sufficient power to determine the impact of Evenness on variables of importance to people with disabilities including anxiety, participation in daily activities and quality of life. Future research could incorporate in built measures of physiology which could be used as part of objective evaluation of the impact of Evenness.

Conclusion

The present study explored the perceptions of adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities who had used the Evenness VR Sensory Room for a period of 5 months, as well as their carers and the program implementation staff to identify the feasibility of the new system. Results suggest that demand and acceptability were strong, although one notable challenge to acceptability was the VR Headset which warrants attention. Implementation processes were consistent which supported the intended individualised experience whilst in the VR Sensory Room. Interviewees described numerous improvements to the product itself as well as the personnel and wrap around supports required to maximise implementation. Results highlight user and stakeholder insights to inform VR developers about the design features most desired, as well as guidance to clinicians about the processes and wrap around supports sought when implementing VR Sensory Rooms. The results, together with the preliminary impact results by Mills and colleagues [Citation40], cast the Evenness VR Sensory Room as a promising tool for adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities, warranting further larger-scale research and development into impacts in clinical practice.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from Western Sydney University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and was conducted in line with ethical procedures. This HREC is constituted and operates in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018). Approval granted 1st June 2020, No: H13815.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to acknowledge and thank The Disability Trust for their support of this work.

Disclosure statement

This research was funded by Devika, Wollongong along with NSW Business as part of the TechVoucher program which provides matched funding to small businesses to engage in research activities ($24,000AUD). Devika are also the developers and owners of Evenness. Devika were not involved in data collection, interpretation or write up of findings. Western Sydney University and University of Wollongong do not have any ownership of Evenness and do not benefit financially from Evenness sales. Researchers have no other conflicts to declare.

Data Availability statement

Due to the qualitative nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. Disability and Health. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health.

- Council for Intellectual Disability. The health of people with intellectual disability. Budget and federal election 2019. NSW, Australia: Commitments sought from Australian political parties 2019. p. 19. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://cid.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Intellectual_disability_health_bid_200219.pdf

- Baudewijns L, Ronsse E, Verstraete V, et al. Problem behaviours and major depressive disorder in adults with intellectual disability and autism. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:769–774.

- Ball J, Fazil Q. Does engagement in meaningful occupation reduce challenging behaviour in people with intellectual disabilities? A systematic review of the literature. J Intellect Disabil. 2013;17(1):64–77.

- Machingura T, et al. Effectiveness of sensory modulation in treating sensory modulation disorders in adults with schizophrenia: a systematic literature review. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2018;16(3):764–780.

- Tomchek SD, Little LM, Dunn W. Sensory pattern contributions to developmental performance in children with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69(5):6905185040p1–690518504010.

- Ashburner J, Ziviani J, Rodger S. Sensory processing and classroom emotional, behavioral, and educational outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62(5):564–573.

- Costa-López B, et al. Relationship between sensory processing and quality of life: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2021;10(17):3961.

- Anzalone ME, Lane SJ. Sensory processing disorder. In: Bundy S.J.L.A.C., editor. Kids can be kids: a childhood occupations approach. FA Davis: Philadelphia; 2012. p. 437–459.

- Crasta JE, et al. Sensory processing and attention profiles among children with sensory processing disorders and autism spectrum disorders. Front Integr Neurosci. 2020;22:14.

- van den Boogert F, et al. Sensory processing and aggressive behavior in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Brain sciences. 2021;11(1):95.

- Robertson CE, Baron-Cohen S. Sensory perception in autism. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(11):671–684.

- Petrenko CL. A review of intervention programs to prevent and treat behavioral problems in young children with developmental disabilities. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2013;25(6):651–679.

- Eccles MP, et al. An implementation research agenda. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):1–7.

- Moir T. Why is implementation science important for intervention design and evaluation within educational settings?. Front Educ. 2018;3(61):1–9.

- Kelly B, Perkins DF. Handbook of implementation science for psychology in education. 2012. CambridgeUK: Cambridge University Press.

- Medical Research Council. Developing and evaluating complex interventions. 2019. Available from: https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance.

- Andreassen M, et al. Feasibility of an intervention for patients with cognitive impairment using an interactive digital calendar with mobile phone reminders (RemindMe) to improve the performance of activities in everyday life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7). DOI:10.3390/ijerph17072222

- Fava L, Strauss K. Multi-sensory rooms: comparing effects of the snoezelen and the stimulus preference environment on the behavior of adults with profound mental retardation. Res Dev Disabil. 2010;31(1):160–171.

- Lotan M, Gold C. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of individual intervention in the controlled multisensory environment (Snoezelen®) for individuals with intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;34(3):207–215.

- Toro B. Memory and standing balance after multisensory stimulation in a snoezelen room in people with moderate learning disabilities. Br J Learn Disabil. 2019;47(4):270–278.

- Cameron A, et al. Making sense of multi-sensory environments: a scoping review. Internl J Disabil, Dev Educ. 2020;67(6):630–656.

- Koller D, McPherson AC, Lockwood I, et al. The impact of snoezelen in pediatric complex continuing care: a pilot study. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2018;11(1):31–41.

- Nadkarni NM, et al. Impacts of nature imagery on people in severely nature-deprived environments. Front Ecol Environ. 2017;15(7):395–403.

- Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Winton ASW, et al. Effects of snoezelen room, activities of daily living skills training, and vocational skills training on aggression and self-injury by adults with mental retardation and mental illness. Res Dev Disabil. 2004;25(3):285–293.

- Barbic SP, et al. Health provider and service-user experiences of sensory modulation rooms in an acute inpatient psychiatry setting. PLOS One. 2019;14(11):e0225238–e0225238.

- Thompson SBN, Martin S. Making Sense of multisensory rooms for people with learning disabilities. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1994;57(9):341–344.

- Durante SB, Reddon JR. An environment enrichment redesign of seclusion rooms. Current Psychology, 2022.

- Scanlan JN, Novak T. Sensory approaches in mental health: a scoping review. Aust Occup Ther J. 2015;62(5):277–285.

- Shapiro M, Melmed RN, Sgan-Cohen HD, et al. Effect of sensory adaptation on anxiety of children with developmental disabilities: a new approach. Pediatr Dent. 2009;31(3):222–228.

- Breslin L, Guerra N, Ganz L, et al. Clinical utility of multisensory environments for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a scoping review. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74(1):7401205060p1–7401205060p12.

- Fowler S. Multisensory rooms and environments: controlled sensory experiences for people with profound and multiple disabilities 1st ed. 2008. London, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- De’ R, Pandey N, Pal A. Impact of digital surge during Covid-19 pandemic: a viewpoint on research and practice. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;55:102171.

- Wuang Y-P, Chiang C-S, Su C-Y, et al. Effectiveness of virtual reality using Wii gaming technology in children with down syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(1):312–321.

- Dechsling A, Shic F, Zhang D, et al. Virtual reality and naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;111:103885.

- Montana JI, et al. The benefits of emotion regulation interventions in virtual reality for the improvement of wellbeing in adults and older adults: a systematic review. JClinMed. 2020;9(2):500.

- Gerardi M, Cukor J, Difede J, et al. Virtual reality exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder and other anxiety disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(4):298–305.

- Bryant L, Brunner M, Hemsley B. A review of virtual reality technologies in the field of communication disability: implications for practice and research. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;15(4):365–372.

- Standen PJ, Brown DJ. Virtual reality and its role in removing the barriers that turn cognitive impairments into intellectual disability. Virtual Reality. 2006;10(3):241–252.

- Mills CJ, et al. Evaluating a virtual reality sensory room for adults with disabilities. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1). DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-26100-6

- Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452–457.

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London, UK: Sage; 2018.

- Ramanadhan S, et al. Pragmatic approaches to analyzing qualitative data for implementation science: an introduction. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1). DOI:10.1186/s43058-021-00174-1

- Neergaard MA, et al. Qualitative description – the poor cousin of health research? BMC Med Res Method. 2009;9(1):52.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. Analysing qualitative data in psychology. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 2021. p. 128–147.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. London, UK: SAGE Publications. 2022. 376.

- Vaismoradi M, et al. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2016;6(5). DOI:10.17169/fqs-20.3.3376

- Curtin M, Fossey E. Appraising the trustworthiness of qualitative studies: guidelines for occupational therapists. Aust Occup Ther J. 2007;54(2):88–94.

- Lotan M, Yalon-Chamovitz S, Weiss PL. Training caregivers to provide virtual reality intervention for adults with severe intellectual and developmental disability. J Phys Ther Educ. 2011;25(1).15–19.

- Yakubova G, et al. Practitioners’ attitudes and perceptions toward the use of augmented and virtual reality technologies in the education of students with disabilities. J Spec Educ Technol. 2022;37(2):286–296.

- Bradley R, Newbutt N. Autism and virtual reality head-mounted displays: a state of the art systematic review. J Enabling Technol. 2018;12(3):101–113.

- Schmidt M, et al. A process-model for minimizing adverse effects when using head mounted Display-Based virtual reality for individuals with autism. Front Virtual Real. 2021;2. DOI:10.3389/frvir.2021.611740

- Markopoulos P. Mental health practitioners perceptions’ of presence in a virtual reality therapy environment for use for children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. New Orleans (LA): University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations; 2018.

- Werkman MF, et al. The impact of the presence of intellectual disabilities on sensory processing and behavioral outcomes among individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2022. DOI:10.1007/s40489-022-00301-1

- Mills CJ, Chapparo C, Hinitt J. The impact of sensory activity schedule (SAS) intervention on classroom task performance in students with autism – a pilot randomised controlled trial. Adv Autism. 2020;6(3):179–193.

- Gil V, Bennett KD, Barbetta PM. Teaching young adults with intellectual disability grocery shopping skills in a community setting using least-to-most prompting. Behav Anal Pract. 2019;12(3):649–653.

- Dollar CA, Fredrick LD, Alberto PA, et al. Using simultaneous prompting to teach independent living and leisure skills to adults with severe intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(1):189–195.

- Shah LBI, Torres S, Kannusamy P, et al. Efficacy of the virtual reality-based stress management program on stress-related variables in people with mood disorders: the feasibility study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(1):6–13.

- Pfeiffer B, Stein Duker L, Murphy A, et al. Effectiveness of noise-attenuating headphones on physiological responses for children with autism spectrum disorders. Front Integr Neurosci. 2019;13:65.