Abstract

Purpose

To identify the experiences and needs of dependent children who have a parent with an acquired brain injury (ABI) using a systematic review and thematic synthesis.

Materials and methods

A systematic search of Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, and Web of Science was conducted. The search included variants of: “children,” “parents,” “acquired brain injury,” and “experiences” or “needs.” Eligible articles reported on the experiences/needs of dependent children who have a parent with an ABI, from the child’s perspective. Thematic analysis was used to identify themes.

Results

A total of 4895 unique titles were assessed, and 9 studies met inclusion. Four themes were identified: (1) Sustained Emotional Toll (subthemes: (i) Initial Shock and Distress; (ii) Ongoing Loss and Grief; (iii) Present-Day Stress and Emotions), (2) Responsibilities Change and Children Help Out, (3) Using Coping Strategies (subtheme: Talking Can Help), and (4) Wanting Information about the Injury.

Conclusion

Themes highlighted significant disruption and challenges to children’s wellbeing across development, with ongoing and considerable impacts many years after the parent’s injury. The nature of the experiences shifted with time since the parent’s injury. These children need ongoing support starting shortly after their parent’s injury that is grounded in their particular experiences.

When a parent has an acquired brain injury (ABI), dependent children and adolescents face emotional upheaval, significant stressors, increased responsibilities, and lack of information about their parent’s injury that persist even many years after injury.

The nature of these experiences and therefore their needs change based on the acute versus later stages of the parent’s injury.

Children often do not ask questions or tell others how they feel, which means that they need support that asks about, and listens and responds to their needs.

Support for children needs to start soon after the parent’s injury, be grounded in the lived experiences of this group, consider their parent’s recovery stage, and be embedded as part of service provision rather than rely on children or families to make service contact.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is an umbrella term that refers to brain damage occurring after birth, from diverse causes such as stroke, accidents, degenerative neurological disease or oxygen deprivation [Citation1,Citation2]. ABI affects people across the lifespan and is considered relatively common; for example, data from the United States indicates a 53% increase in emergency care hospital visits for traumatic brain injury over 2006–2014 [Citation3], and about a 30% increase in stroke in 18–54 year olds over 2003–2012 [Citation4]. An ABI can profoundly impact the individual with the condition, causing disability of varying severity to cognition, emotions, sensation, behaviour, and/or physical functioning [Citation5,Citation6].

Given the immense and wide-ranging personal impacts for the individual with a moderate to severe ABI, families are a crucial source of practical and emotional support [Citation7]. Although preparing families to provide care for the person with ABI is needed, many families describe that the focus of care remains on the person rather than their family context [Citation8]. A recent meta-synthesis of qualitative studies describing families’ needs prior to hospital discharge highlighted challenging experiences across seven themes, including: (1) adjustment after the injury; (2) being involved in care; (3) dealing with the event; (4) perceptions of rehabilitation; (5) perceptions of relationships; (6) preparing to be a caregiver; and (7) information needs [Citation9]. These themes emphasise the intense emotions, use of coping strategies, need to tolerate uncertainty, and need for support from friends, family, and professionals. These results are consistent with those found after hospital discharge [Citation10–12], and highlight the impact of the ABI not only on the affected individual, but all family members.

These previous studies focus on families at any stage of life. What, then, happens when the individual with the ABI is a parent, and the family has dependent children? Children and adolescents rely on their parents to meet their needs; having a parent who experiences an ABI can cause substantial change and disruption during these sensitive developmental years [Citation13]. As well as the grief connected to the parent’s injury, children and adolescents must understand and cope with a parent who does not relate or behave as they did previously. Symptomatic changes that impact on the parenting role are diverse and contingent on the type and severity of the injury, spanning changes in motor ability and social relationships, as well as emotional and cognitive changes such as memory loss, aggression, difficulties with planning and judgement, short temper, and/or aphasia and other communication disorders. These changes are associated with complex and multiple losses [Citation14–16], including the interruption of parenting skills, the ongoing confusion of altered parent-child relationships, and the loss of a major source of support and protection. Co-parents are substantially impacted, often providing additional care and/or work outside the home, and thus children must also cope with the reduced availability of their well parent [Citation17]. Many children assist with caring, and therefore children face realignment of family roles, routines, and responsibilities [Citation15]. The hidden nature of the ABI-related disability in the presence of some symptoms (e.g., communication and memory problems) can also lead to disengagement from social and community support [Citation18]. For the child, this potentially means limited interactions with others in their neighbourhood and school, limiting the child’s access to support that is needed as they develop and confront the long-term challenges related to their parent’s neurocognitive impairments.

There is a small but growing literature on the psychosocial impact of parental ABI on dependent children. Some literature shows that children adjust to the challenges presented by their parent’s ABI, with some even identifying positive aspects of the experience [Citation14,Citation17,Citation19,Citation20]. However, this group is also at risk of poorer psychosocial outcomes, including elevated levels of distress, emotional and behavioral problems, school difficulties, disruption of social relationships, and issues with sleep and eating [Citation14,Citation20–25]. These impacts can be long-lasting. A 21-year follow-up study of 60 069 Finnish children born in 1987 using linked administrative data found that children affected by parental traumatic brain injury were more likely to experience psychiatric disorders and access specialist psychiatric services than their same-aged cohort [Citation26,Citation27]. Factors that have been associated with poorer psychosocial functioning in children include mental health of the parent with ABI and their spouse [Citation17,Citation28,Citation29], limitations in extended activities of daily living associated with the ABI [Citation17], higher levels of family stress [Citation30], poorer parental relationships [Citation21], and female gender of the child [Citation17], although there is evidence that males are at increased risk of externalising disorders compared to females [Citation26].

The need to provide this population with relevant psychosocial support has been highlighted (e.g., [Citation18,Citation31]). However, such support is frequently not available through formal channels, and the needs of dependent children are often overlooked by health service providers, as they are tasked with providing for the affected parent [Citation23,Citation32]. This stands in contrast with children’s expressed desire for supportive services [Citation15,Citation31]. As service user involvement increasingly plays a central role in establishing priorities for the development and evaluation of health services, it is important to understand the support needs and preferences of this population. This knowledge can facilitate evaluating and adapting existing interventions and developing new ones, and help to ensure that interventions are relevant to the lives and experiences of the population they are intended to support.

Recent systematic reviews have been undertaken to comprehensively identify the needs and experiences of children affected or bereaved by other types of serious and protracted parental illness, such as cancer and mental illness [Citation33–37]. These studies tend to report that children and adolescents need developmentally appropriate information about the parent’s illness [Citation33,Citation35–37], support [Citation33–37], help to communicate [Citation33,Citation36], support with social relationships [Citation33–36], and to cope with distress and other difficult emotions [Citation33,Citation35,Citation37]. It is possible that the needs of offspring affected by a parent’s ABI will share some overlap with those of children affected by a parent’s cancer or mental illness given that there are some potential overlapping concerns (e.g., questions around course of the illness and interventions, effectiveness of interventions). However, it is also possible that they will differ in meaningful and important ways, as the neurocognitive component and treatment course or effectiveness might engender other needs.

Within the literature on parental ABI, recent reviews have focused on exploring the impact of a parent’s ABI on child adjustment [Citation23], comparing child responses across a range of parental neurological disorders [Citation38], and understanding parenting after stroke [Citation18]. These studies provide valuable information on the various ways in which children and families experience and are affected by ABI, highlighting that these children are at risk and in need of support tailored to the parent’s condition [Citation23,Citation38], as well as the many changes that happen to parenting after a stroke specifically [Citation18]. Yet no systematic review study has examined the needs and experiences of dependent children affected by a parent’s ABI. A better understanding of how children are impacted and their needs could guide resource allocation, service development, and staff training within facilities that offer services to people with ABI. In particular, a review of qualitative studies has the potential advantage of offering insight into perceptions of the child’s experiences and needs through their eyes [Citation39], which has been called for as especially needed in brain injury research [Citation10]. In so doing, interventions developed on the basis of these findings would therefore be grounded in the lived experience of this group of vulnerable children, which is increasingly emphasised in healthcare services [Citation40]. To this end, the primary goal of this study was to aggregate and synthesise the existing literature on the needs of children and adolescents living with a parent’s ABI. To do so, we conducted a systematic review to address the following question: What are the experiences and needs of children and adolescents (aged less than 18 years at the time of their parent’s diagnosis or injury) who have a parent with an ABI, as identified in the published literature?

Methods

Methods for this review followed guidelines provided by the Centre for Review and Dissemination [Citation41], and Preferred reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used to report findings.

Search strategy

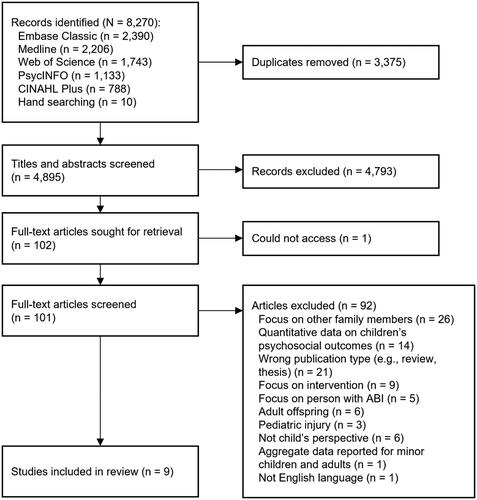

A comprehensive electronic search was conducted using Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Web of Science. Four key concepts informed the search strategy: “children,” “parents,” “acquired brain injury,” and “needs” or “experiences.” Database searching was carried out on the same day (18 November 2020) and updated on 10 August 2021 and again on 5 November 2022 according to Bramer and Bain’s [Citation42] guidelines for updating systematic review searches. Results were limited to those in the English language studying humans. No other search limits were applied. The search strategy was guided by similar reviews exploring child needs and experiences of chronic parental illness (e.g., [Citation33]). See Appendix 1 for the full search strategy (Supplementary Material). Reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and included articles were scanned for additional literature. The process of the systematic search and inclusion of papers is detailed in .

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they were (1) peer-reviewed original research, (2) published in English, and (3) provided data from children up to 18 years who had a parent with an ABI about their psychosocial support needs and/or experiences in the results section of the manuscript. To be included, child needs or experiences needed to be reported from the perspective of children (<18 years). Studies were excluded if data were derived from children/offspring aged ≥18 years, or from the perspective of other family members, unless data from children <18 years at the time of their parent’s injury could be separated out, in which case only the perspectives from children <18 years at the time of their parent’s injury were included in the analysis. To limit studies to ABI, if a study included parental illness/injury other than ABI, it was excluded unless data specifically relevant to ABI could be separated out. Studies that provided a quantitative assessment of children’s psychosocial adjustment following parental ABI or reported on interventions to support families following parental ABI without providing data on needs or experiences were excluded.

Study selection

After conducting the search as described, duplicates were removed before applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Two authors who are PhD students in psychology studying mental health, wellbeing, and adversity of adolescents and young adults (initials withheld for review) independently screened titles and abstracts. They then independently read the full text of each study that was screened in at the abstract stage and later checked for agreement.

Data extraction and critical appraisal of studies

Data extraction was performed by one of the authors (initials withheld for review) and checked by the first author, including: author(s), year of publication, country in which the study was conducted, study purpose, study design, sample strategy, sample characteristics, data collection techniques, data analysis techniques, and findings. Two authors (HMJ and GF) used the QualSyst Tool for Qualitative Studies [Citation43] to assess the quality of the studies reviewed. The tool comprises 10 criteria scored as 0 (no), 1 (partial), and 2 (yes), with a maximum total score of 20. A summary score can be obtained by summing item scores and dividing by 20 so that the final score falls between 0 and 1. When scoring discrepancies occurred, they were discussed with the first author to reach agreement.

Analysis of findings from studies in this review

Findings from all studies were extracted and analysed using theoretical thematic analysis [Citation44]. The data analysis was primarily led by three authors who are all female and have an academic background in psychology: the first author (JLO) is a clinical psychologist and academic whose research expertise spans parenting and child development with a focus on vulnerable families; the second author (HMJ) is a PhD student whose studies are focussed on accessibility of and engagement in digital mental health and wellbeing interventions for adolescents and young adults; the third author (RB) is a practicing clinical and counselling psychologist and works with children, parents, and families, including those with a parent with an acquired brain injury. Given the research and practical experience of the first and third authors in particular, we approached this analysis acknowledging that our knowledge and experiences could not be fully removed from the process, and that the analysis could therefore not be entirely inductive. We therefore chose to use Braun and Clarke’s theoretical thematic analysis, which acknowledges pre-existing knowledge, and adopted a constructivist and subjective approach to analysis [Citation44]. Still, we engaged in reflexive journaling throughout to address potential bias. These three authors first read through each study. In the second step, the authors extracted and read through all data relating to direct quotes from children aged less than 18 at the time of the parent’s injury from all studies, making notes about impressions and emerging ideas. Codes were developed and applied to the data, and these were grouped together based on similarities to develop meaningful emergent themes. Next, we extracted theme names from all studies, where themes included at least one quote from a child aged less than 18 years at the time of the injury, and these were also coded for fit within the emerging theme clusters. Themes were refined based on continual review of the clusters and the ideas they represented. The authors met to discuss and agree on themes.

Results

The search identified 4895 unique manuscripts, and 9 studies met inclusion criteria (see ). A summary of study characteristics and key findings is presented in . Studies were conducted in the UK [Citation15,Citation19,Citation45,Citation46], Australia [Citation14,Citation31], South Africa [Citation47], Denmark [Citation16], and Norway [Citation48]. All studies primarily used a qualitative approach, with six reporting an explicit aim to explore the experiences of children affected by ABI [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation46,Citation47] and the remaining examined family experiences more generally [Citation31,Citation45,Citation48].

Table 1. Characteristics and key findings of eight ABI studies included in the systematic review.

Three studies used child reports to assess children’s experiences and needs [Citation14,Citation16,Citation47], and six also incorporated parents’ perspectives [Citation15,Citation19,Citation31,Citation45,Citation46,Citation48]. All of the children in the selected studies were 18 years or under at the time of their parent’s injury, although some were young adults at the time of interview [Citation19,Citation47,Citation48], with the exception of one study [Citation46], which included children aged 11–20 years at the time of the parent’s injury (and in this case, only data related to children under 18 years at the time of their parent’s injury was extracted). Three studies reported exclusively on adolescents [Citation19,Citation47,Citation48], and five included school aged children and adolescents [Citation14–16,Citation31,Citation45,Citation46].

Parent diagnoses included stroke (n = 3) [Citation45,Citation46,Citation48], severe traumatic brain injury (n = 1) [Citation47], and specified or unspecified ABI (n = 5) [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation31]. Two studies reported on children’s experiences of having a father with ABI [Citation14,Citation47], with the remaining reporting on ABI in either parent. For included child data, in studies reporting the child’s age at the time of the interview, ages ranged from 7 to 19 years, and the time since the parent’s injury ranged from 88 days to 7 years [Citation14,Citation16,Citation19,Citation45–47]. Details are in , which is organised by type of parent injury (mixed cause, stroke, motor vehicle or cycling accident, or not reported/unknown).

Critical appraisal of the included studies

Quality assessment was conducted on the studies reviewed. Quality scores ranged from 0.70 to 1 (see ). The most common methodological shortcoming involved a lack of reflexivity regarding the impact of the researchers’ personal characteristics on the data obtained. Kmet and colleagues [Citation43] suggest 0.55 as the minimum acceptable score for a study’s inclusion, therefore all studies were included in analysis.

Children’s experiences and needs related to having a parent with an ABI

Four themes were identified, reflecting intertwined experiences and needs: (1) Sustained Emotional Toll (subthemes: (i) Initial Shock and Distress; (ii) Ongoing Loss and Grief; (iii) Present-Day Stress and Emotions), (2) Responsibilities Change and Children Help Out, (3) Using Coping Strategies (subtheme: Talking Can Help), and (4) Wanting Information about the Injury. presents an overview of the thematic structure and the key characteristics of each theme and subtheme. To privilege children’s voices, we include quotes from studies directly within the theme description alongside information about child age, child and parent gender, and time since the parent’s ABI diagnosis/event (where this information was given from the original study). We provide these quotes from a mix of studies, ages, and genders.

Table 2. Names and characteristics of themes describing experiences and needs of children and adolescents who have a parent with an ABI.

Sustained emotional toll

In all studies, children across all ages described persistent, strong emotions that started from the time of their parent’s injury [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation31,Citation45–48]. These emotions changed with time since the injury, beginning with shock and fear of losing the parent during the acute stage(s). After the acute phase, children described a sense of loss and sadness that stayed with them, even many years after the injury. In the current day, children also described significant stress and negative emotions related to the impacts of their parent’s injury. This progression of emotional experiences was across ages and study locations and is presented as subthemes below.

Initial shock and distress (subtheme)

Shortly after their parent’s injury, all but one study highlighted the range of negative emotions—including shock, confusion, sadness, distress, and fear—that children and adolescents experienced during the acute stage of their parent’s injury [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation31,Citation45,Citation47,Citation48]. Emotions were overwhelming, “…I was sure he was dying and collapsed totally crying” boy, aged 15, father with ABI [Citation16,p.1565]. These experiences were often vividly recalled across age and gender, for example, a 17-year old girl described “feeling numb” soon after her mother’s injury [Citation47,p.50], and an 8-year old boy with a mother with an ABI recalled, “I thought we were losing her and got very scared. She was all blue in the face and looked spooky. I couldn’t look at her without crying, so my aunt took me out of the ward” [Citation16,p.1565].

Ongoing loss and grief (subtheme)

In seven studies, soon after the acute stages of the injury resolved and lasting to the present day (time of participation), children of all ages described an ongoing sense of loss and associated sadness and grief [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation31,Citation45,Citation46]. Their parent is present, but not the same, “he’s still a Dad like he cares for me and all that, but most of him now, he’s like a friend now… it feels like you’ve lost something and it just feels like I’ve lost a bit of my Dad” boy, aged 16, father 46 months post-ABI onset [Citation45,p.480]. For some, the sense of loss was profound, “for me, it is like he died, and I got a stepfather instead. This is a tough thought to have. It would have been 100% easier if he had died; then everybody would understand that he was gone...” girl, aged 14, father with ABI [Citation16,p.1566].

For some children, the discrepancy between their parent before and after injury was stark and realised suddenly, “when we got home, it just basically all, kind of, crashed and burned. It just wasn’t the same and that is when it really hit, I think…just, like, not having the dad that we had before” girl, aged 17 [Citation31,p.4]. Some children, however, focussed on consistencies pre- versus post- ABI, “She has always been the quiet type and she hasn’t changed a lot, because if I think she has changed, I get sad” boy, aged 12, mother 42 months post-ABI onset [Citation16,p.1566], or did not notice or acknowledge changes, “it hasn’t changed her” girl, aged 16, mother 18 months post-ABI onset [Citation45,p.480]; both of which mitigated feelings of loss and grief. For some it was a struggle to understand ‘invisible’ changes, “… to see someone in your mom’s body but she’s not the person she was before. And you can’t, you can’t understand why it’s not the same person” girl, aged between 9 and 18 mother with ABI [Citation15,p.202].

Present-day stress and emotions (subtheme)

In six of the studies, children described facing ongoing challenges due to their parent’s ABI or impairments related to their parent’s ABI, and that this resulted in persistent, strong emotions into the present-day [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation45,Citation46]. Many children noted a change in their injured parent’s mood that could affect the family’s emotional climate, as well as their own wellbeing, “He never seemed in a good mood. And, a lot, lots of times they were arguing and it’s such a small house it’s quite hard not to hear, and that was quite upsetting…” girl, aged between 9 and 18, father with ABI [Citation15,p.201]. Worry and distress were most prominent, “When mum [non-injured parent] gets really angry she just goes for a little walk or a drive… sometimes I think that she is leaving us. She’s been saying one day she’ll leave… I have nightmares… I think she will have an accident or a car crash or something” girl, aged 9, father 4 years post-ABI onset [Citation14,p.90]. Sometimes children extended to worry about their own health, “…if I get like a mole or something, I’d be scared like “oh no, I’m getting, say like cancer” or something like that and I just worry about it for like three or four weeks and then it’s like an ongoing cycle, my heart races, I feel ill” boy, aged 16, father 42 months post-ABI onset [Citation45,p. 79]. However, some children experienced anger, hostility, and/or annoyance, “At home, I would be able to help out, but at school for some reason I couldn’t really… I just seemed to be angry at school, not home” girl, aged 17, father 32 months post-ABI onset [Citation19,p.1229].

Whereas some children contained their emotions at times or in certain places, for others the stress was unmanageable, “life’s a mess, life stinks … I’m crazy, I’m going to have an aneurism” boy, aged 12, father 4 years post-ABI onset [Citation14,p.94]. This variability might be related to the severity of the parent’s post-injury impairments. Many children did not share their stress or emotions with others, even when it affected them severely, “…I kept a lot of stuff in like at the time and erm I didn’t tell anyone or anything and then like I ended up in hospital, like my face like half of it like blew up like I’d got a massive swollen face, and then like I couldn’t move my right side either and then like they knew it wasn’t [stroke] [. . .], they said well it’s stress” girl, aged 16, mother 18 months post-ABI onset [Citation45,p.480].

Using coping strategies

Seven studies described children’s use of and need for coping strategies [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation45–47]. The most commonly reported coping strategies that children and adolescents reported included avoidance (e.g., “going out the house to avoid it completely was good” girl, aged between 9 and 18 years [Citation15,p.204]) and distraction (e.g., spending time with friends, playing with pets, going to school, listening to music). Although less frequently mentioned, cognitively reappraising the situation (e.g., “I have to remind myself that it is more difficult for my parents than it is for me because it doesn’t help me that I feel sorry for myself all the time!” boy, aged 14 [Citation16,p.1566]) and helping others (e.g., “I might as well use what I have learned” girl, aged 14 in talking about caring for others [Citation16,p.1566]) were also mentioned as helpful. Some mentioned avoiding or hiding their needs and/or emotions; for example, regarding sadness, “… I flush them down the toilet…. And then I just don’t think about it,” boy, aged 12, father 4 years post-ABI onset [Citation14,p.94]. During adolescence, some found meaning, “… She (mother) stays so positive […] makes me more positive about the whole situation” girl, aged 17, father 4-years post-ABI onset [Citation19,p.1226].

Talking can help (subtheme)

Seven studies reported that children felt isolated and alone, and that for those who could, talking to someone helped make them feel better and more connected [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation31,Citation45,Citation47]. Participants felt estranged from, misunderstood by, and/or different from their peers. Their family experiences, especially with their injured parent, were foreign to those of their peers, “I find it so annoying when my girlfriends complain about how fed up they are with their mothers—I think they are lucky just to have a normal mother” girl, aged 11 years [Citation16,p.1566]. Conversely, having at least one source of social support was crucial to help cope with stressors that resulted from their situation; this support could come from peers, teachers/school, professionals, friends of the family, and/or family members. This was true for children (e.g., “It feels good talking to her, as she often has emotions and reactions resembling my own” girl, aged 10, talking about her 8-year old sister [Citation16,p.1567]) as well as adolescents, “All my real good friends took over…they took a big decision to like coat me in bubble wrap” girl, aged 17, father 49-months post-ABI onset [Citation19,p.1229]. Social support, especially in the form of talking, was seen as therapeutic and necessary:

“…we’re all supportive and I think if we keep being supportive, it will help and it’ll just keep on helping even more but if we keep it to ourselves, it’s just gonna break us more, we’re gonna become more lonely and won’t be able to talk about it” boy, aged 16, father 42 months post-ABI [Citation45,p.481]

Responsibilities change and children help out

In all studies [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation31,Citation45–48], children observed significant changes to family members’ responsibilities soon after a parent’s brain injury. These resulted in the child taking on additional responsibilities, “No not really. But I look after her. So it’s alright. I look after myself and I look after her yeah” boy, 12 years, mother 124 days post-ABI [Citation46,p.9]. Children saw how the parent’s injury impacted the co-parent, increasing their stress and tasks, “Well now it’s like looking after four children now instead of like three” boy, aged 16, father 42 months post-ABI onset [Citation45,p.480], which often led to an angry or unhappy mood [Citation14]. Shifts in responsibilities for other family members, especially siblings, were also described, “I remember very well my mother not being there and my sister taking the responsibility; it was a lot of responsibility… she took me to kindergarten on her bicycle” girl, aged under 18 years at time of parent’s injury [Citation48,p.E5]. Although the extent of additional responsibilities changed with development, increases in the child’s responsibilities were across age and continued.

Children and adolescents described taking on practical chores (e.g., cooking, cleaning) [Citation15,Citation16,Citation31,Citation46–48]. They also described indirectly helping out, “you have to be patient with them and you can’t, like, stress them out a lot” girl, 16 years, mother 18 months post-ABI onset [Citation45,p.480]. Some adolescents felt that they matured quickly as a result, “…We had to grow up so fast, which was kind of wrong I suppose’’ girl, aged 17, father 49 months post-ABI onset [Citation19,p.1227]. These role changes impacted children differently, with some finding the situation wearing and in need of respite, “…how long until we can all relax a bit?” girl, aged 17 [Citation31,p.285], and some noting positive impacts on themselves personally, “‘I think it is a good thing (having a caring role in the family) because when I move out and I have to look after myself and they (friends) move out they won’t know what to do’’ girl, 17, father 49 months post-ABI [Citation19,p.1227] and relationally.

Wanting information about the injury

Seven of the nine studies described children’s and adolescent’s need for information about the parent’s injury, treatments, and expected course [Citation14,Citation15,Citation31,Citation45–47]. Children described not being given enough—or even any—information about their parent’s injury in the acute stage after injury, “they [health care professionals] just do their job and then they skedaddle” boy, 11 years, father 332 days post-ABI [Citation46,p.8]. This was not confined to younger child participants, as adolescents also described not receiving information, “They [health professionals] would not tell us anything” girl, aged 17, father with ABI [Citation47,p.52]. The desire for information continued and was needed at all phases of the injury and recovery, although the type of information shifted from wanting to know about the immediate impact of the parent’s injury to its long-term course and treatment, “I knew it was like a life risk but I didn’t know how it can be caused, I didn’t know what the consequences could be, I didn’t know like you have to have all these tablets” boy, 16 years, father 46 months post-ABI onset [Citation45,p.479]. Not having information left children and adolescents unprepared; for example, one participant described that she thought her father “would come back to normal” girl, aged 18, father post-ABI onset [Citation47,p.52].

Children not only felt the desire for this information, but also that they had a right to it given the closeness of the parent-child relationship, “after all… he is our Dad…” girl, aged 12, father 3 years post-ABI onset [Citation14,p.88]. At the same time, children felt that they could not express this desire or ask questions, “I just normally kept that [questions about the parent’s injury] in my head” girl, aged 7 [Citation31,p.5]. In general, children described not being given enough information about their parent’s injury, which made it difficult to anticipate the consequences of living with a parent with an ABI.

Discussion

When a person experiences an ABI, it impacts the entire family [Citation9,Citation10]. This review used a meta-synthesis methodology to describe children’s experiences and needs when they have a parent with an ABI. Nine studies met our inclusion criteria; the majority described experiences, which comment on and suggest needs. Four themes were identified: (1) Sustained Emotional Toll (subthemes: (i) Initial Shock and Distress; (ii) Ongoing Loss and Grief; (iii) Present-Day Stress and Emotions), (2) Using Coping Strategies (subtheme: Talking Can Help), (3) Responsibilities Change and Children Help Out, and (4) Wanting Information about the Injury. Throughout themes, children and adolescents alike tended to describe keeping questions, needs, and experiences to themselves, sometimes to the point of purposefully pretending to be well. Although this might serve multiple purposes (e.g., maintain privacy, not burden family members), this risks their needs being overlooked, and children not getting help until the toll is very serious. This also supports the importance of research into needs, and the purpose of this review, which is to understand and represent their experiences and needs.

The findings overlap somewhat with a previous meta synthesis of family members’ needs when a loved one is hospitalised for an ABI [Citation9], including concerns about social consequences and support needs, use of coping strategies, intense emotional impacts, and the need for information. The current findings also overlap with themes reported in meta syntheses of the needs and experiences of children affected or bereaved by parents with serious and protracted illness [Citation33–37]. As in the current findings, these previous reviews have noted themes of emotional and social challenges [Citation33,Citation34,Citation37], as well as the need for developmentally appropriate information about the parent’s illness [Citation33,Citation35,Citation37], social support [Citation33–37], coping strategies [Citation33–35,Citation37], and help to communicate [Citation33,Citation36]. However, there are differences between these previous and our current findings; in particular, themes in previous meta syntheses focused less on concerns about loss and grief of the parent pre- versus post-illness/injury onset, or on the increases in children’s responsibilities pre- versus post- illness/injury onset. Furthermore, the themes from our current review did not generally emphasise preparing to be a caregiver and children’s perceptions of rehabilitation [Citation34,Citation35], outside of taking on more responsibilities. Support to help children reconcile pre- versus post- injury changes in the parent, and for the family to negotiate shifting responsibilities post-injury might be a unique need of dependent children who have a parent with an ABI. Thus, despite the many similarities between these populations, adapting or tailoring types and timing of resources and support is crucial to speak to the particular lived experiences and needs of each group.

Overall, the themes identified in the current review describe experiences of ongoing challenges and adversity. This was invariant across age: children and adolescents alike described a significant and lasting emotional toll. The nature of the emotional impact tended to change with time since the parent’s injury, showing a progression of overwhelming emotions in the acute phase (Initial Shock and Distress), followed by grief over the differences in the parent before versus after the injury (Ongoing Loss and Grief), and stress-related feelings into the current day, even many years after the parent’s injury (Present-Day Stress and Emotions). Such shifts were also seen throughout other themes as well; for example, children felt that they should be given access to information about the nature of their parent’s injury soon after its onset, and additional information on the long-term outlook and treatment throughout later stages of recovery and adaptation [Citation14,Citation15,Citation19,Citation31,Citation45,Citation46]. This indicates that children need long-term support that starts soon after the parent’s injury, but that the nature of this support will need to shift based on the parent’s stage of injury. Providing information during the acute stage should attend to children’s needs for information about the parent’s injury and the child’s overwhelming emotions, whereas later stages should focus more on information about longer-term course and treatment, managing and coping with stressors, and dealing with feelings of grief and sadness associated with having a parent who has suddenly and significantly changed. Within this, support can help to provide children with someone to talk to and opportunities to connect with other children/adolescents in similar families [Citation14–16,Citation19,Citation31,Citation45,Citation47].

Some adolescents noted positive personal growth from role changes, such as self-reliance and a sense of identity and purpose [Citation15,Citation19,Citation31,Citation46]. These experiences seem akin to children’s reports of benefit-finding [Citation49] and post-traumatic growth [Citation50] when a parent has a serious illness such as cancer. This has been linked to adaptive coping and resiliency [Citation50], and might present an opportunity to develop support or interventions for children who have a parent with an ABI. However, future research will first need to consider the scope and frequency of these positive experiences and work closely with this population if such an intervention were to be authentic and respect the challenges that these children encounter.

Finally, children described wanting but not having enough information about their parent’s brain injury. These experiences and desires are common to previous meta-syntheses of children’s experiences and needs when they have an ill parent [Citation33,Citation35–37], and suggest a general need for health services to holistically consider the family context of their seriously ill family member (e.g., [Citation51]). This information might contribute to easing children’s distress and anxiety, as having timely information would benefit them through reducing confusion and fears about the unknowns [Citation14,Citation15,Citation31,Citation45,Citation47]. Furthermore, parents in some studies have described a lack of age-appropriate guidance for talking with their children [Citation15,Citation31]. Providing this information is not straightforward, as it will need to consider the parent’s particular injury, stage, and course, as well as the child’s developmental stage; for example, younger children might primarily need information on physical changes, while older children and adolescents may require more complex education on the brain and the impact of ABI on their parent, as well as the potential impacts on relationships [Citation31]. More research is needed to understand the informational needs of children, as well as to inform the age-appropriate delivery of this information throughout the parent’s recovery.

Strengths and limitations

Meta-syntheses enable consideration of a wide range of qualitative studies, overcoming low participant numbers inherent to most qualitative work. The 9 studies included in this review consider the perspectives of 67 children. The findings were generally coherent with other meta-syntheses of children who have an ill parent, lending evidence to the validity of the findings. Still, there are limitations; due to considering children’s lived experiences via their own articulated perspectives, younger children or infants/toddlers were not included due to developmentally-related language limitations. The needs of infants, toddlers, and preschoolers might differ but will need to be considered through other methods, such as parents’ perspectives and/or observations. Another limitation is that the reviewed studies preponderantly focused on experiences rather than needs, and those focusing on needs did not necessarily clarify how these could best be met. To move forward, we need to further our understanding and meeting of needs, such as through the type of resources or support and the best timing to offer them. To help do so, studies should also consistently provide information on the type and length of time since the parent’s injury, as well as the child’s age and gender identity.

Conclusion

Much research and clinical services focus on the needs of the person with the ABI. This does not always acknowledge the impact on the family, including dependent children. The information reviewed here offers a glimpse into the acute, intermediate, and long-term changes in a child’s life after a parent sustains an ABI. To effectively support these children, support needs to start early and continue, be grounded in their particular experiences, consider their parent’s recovery stage, and be embedded as part of service provision rather than rely on children or families to make service contact. Furthermore, this offers a preliminary guide to service provision, as well as how to move forward in attending to children’s needs that respect and are sensitive to their lived experiences. Developing services, interventions and/or resources for children informed by their perspectives will ensure that the services are relevant and timely. We encourage greater attention to this aspect of the impact of brain injury in future research and clinical service provision, as well as to future work that seeks to improve the experiences and meet the needs of children and their families.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics 11th revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance report of traumatic brain injury-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths—United States, 2014. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019.

- Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2018 update: a report from the American heart association. Circ. 2018;137(12):e67–e492.

- Grauwmeijer E, Heijenbrok-Kal MH, Peppel LD, et al. Cognition, health-related quality of life, and depression ten years after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective cohort study. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(13):1543–1551.

- Azouvi P, Ghout I, Bayen E, et al. Disability and health-related quality-of-life 4 years after a severe traumatic brain injury: a structural equation modelling analysis. Brain Inj. 2016;30(13–14):1665–1671.

- Lefebvre H, Pelchat D, Swaine B, et al. The experiences of individuals with a traumatic brain injury, families, physicians and health professionals regarding care provided throughout the continuum. Brain Inj. 2005;19(8):585–597.

- Silva-Smith AL. Restructuring life: preparing for and beginning a new caregiving role. J Fam Nurs. 2007;13(1):99–116.

- Oyesanya T. The experience of patients with ABI and their families during the hospital stay: a systematic review of qualitative literature. Brain Inj. 2017;31(2):151–173.

- Kneafsey R, Gawthorpe D. Head injury: long-term consequences for patients and families and implications for nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(5):601–608.

- Turner BJ, Fleming J, Ownsworth T, et al. Perceived service and support needs during transition from hospital to home following acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(10):818–829.

- Cain CH, Neuwirth E, Bellows J, et al. Patient experiences of transitioning from hospital to home: an ethnographic quality improvement project. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):382–387.

- Verhaeghe S, Defloor T, Grypdonck M. Stress and coping among families of patients with traumatic brain injury: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(8):1004–1012.

- Butera-Prinzi F, Perlesz A. Through children’s eyes: children’s experience of living with a parent with an acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2004;18(1):83–101.

- Rohleder P, Lambie J, Hale E. A qualitative study of the emotional coping and support needs of children living with a parent with a brain injury. Brain Inj. 2017;31(2):199–207.

- Kieffer-Kristensen R, Johansen KLG. Hidden loss: a qualitative explorative study of children living with a parent with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2013;27(13–14):1562–1569.

- Van de Port I, Visser-Meily A, Post M, et al. Long-term outcome in children of patients after stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(9):703–707.

- Harris GM, Bettger P. J. Parenting after stroke: a systematic review. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2018;25(5):384–392.

- Moreno-Lopez A, Holttum S, Oddy M. A grounded theory investigation of life experience and the role of social support for adolescent offspring after parental brain injury. Brain Inj. 2011;25(12):1221–1233.

- Visser-Meily A, Post M, van de P, et al. When a parent has a stroke: clinical course and prediction of mood, behavior problems, and health status of their young children. Stroke. 2005;36(11):2436–2440.

- Redolfi A, Bartolini G, Gugliotta M, et al. When a parent suffers ABI: investigation of emotional distress in children. Brain Inj. 2017;31(8):1050–1060.

- Pessar LF, Coad ML, Linn RT, et al. The effects of parental traumatic brain injury on the behaviour of parents and children. Brain Inj. 1993;7(3):231–240.

- Tiar AMV, Dumas JE. Impact of parental acquired brain injury on children: review of the literature and conceptual model. Brain Inj. 2015;29(9):1005–1017.

- Kieffer-Kristensen R, Teasdale TW, Bilenberg N. Post-traumatic stress symptoms and psychological functioning in children of parents with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2011;25(7–8):752–760.

- Uysal S, Hibbard MR, Robillard D, et al. The effect of parental traumatic brain injury on parenting and child behavior. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;13(6):57–71.

- Kinnunen L, Niemelä M, Hakko H, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses of children affected by their parents’ traumatic brain injury: the 1987 finnish birth cohort study. Brain Inj. 2018;32(7):933–940.

- Niemelä MPD, Kinnunen LMD, Paananen RPD, et al. Parents’ traumatic brain injury increases their children’s risk for use of psychiatric care: the 1987 finnish birth cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):337–341.

- Visser-Meily A, Post M, Meijer AM, et al. Children’s adjustment to a parent’s stroke: determinants of health status and psychological problems, and the role of support from the rehabilitation team. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37(4):236–241.

- Sieh DS, Meijer AM, Visser-Meily JMA. Risk factors for stress in children after parental stroke. Rehabil Psychol. 2010;55(4):391–397.

- Kieffer-Kristensen R, Siersma VD, Teasdale TW. Family matters: parental-acquired brain injury and child functioning. NeuroRehabil. 2013;32(1):59–68.

- Dawes K, Carlino A, van den Berg M, et al. Life altering effects on children when a family member has an acquired brain injury; a qualitative exploration of child and family perceptions. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(2):282–290.

- Webster G, Daisley A. Including children in family-focused acquired brain injury rehabilitation: a national survey of rehabilitation staff practice. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(12):1097–1108.

- Ellis SJ, Wakefield CE, Antill G, et al. Supporting children facing a parent’s cancer diagnosis: a systematic review of children’s psychosocial needs and existing interventions. Eur J Cancer. 2017;26(1):e12432.

- Källquist A, Salzmann-Erikson M. Experiences of having a parent with serious mental illness: an interpretive meta-synthesis of qualitative literature. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28(8):2056–2068.

- Yamamoto R, Keogh B. Children’s experiences of living with a parent with mental illness: a systematic review of qualitative studies using thematic analysis. J Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;25(2):131–141.

- Hanna JR, McCaughan E, Semple CJ. Challenges and support needs of parents and children when a parent is at end of life: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2019;33(8):1017–1044.

- Huang X, O'Connor M, Lee S. School-aged and adolescent children’s experience when a parent has non-terminal cancer: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Psycho-Oncol. 2014;23(5):493–506.

- Hartman L, Jenkinson C, Morley D. Young people’s response to parental neurological disorder: a structured review. Adolesc Health, Med Ther. 2020;11:39–51.

- Jennekens N, Casterlé D, Dobbels BD. F. A systematic review of care needs of people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) on a cognitive, emotional and behavioural level. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(9–10):1198–1206.

- Castro EM, Malfait S, Van Regenmortel T, et al. Co-design for implementing patient participation in hospital services: a discussion paper. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(7):1302–1305.

- Butler A, Hall H, Copnell B. A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016;13(3):241–249.

- Bramer WM, Bain P. Updating search strategies for systematic reviews using EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2017;105(3):285–289.

- Kmet LM, Cook LS, Lee RC. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. 2004.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Coppock C, Ferguson S, Green A, et al. It’s nothing you could ever prepare anyone for’: the experiences of young people and their families following parental stroke. Brain Inj. 2018;32(4):474–486.

- Cameron TM, Walker MF, Fisher RJ. A qualitative study exploring the lives and caring practices of young carers of stroke survivors. Int J Environ Res. 2022;19(7):3941.

- Harris D, Stuart A. Adolescents’ experience of a parental traumatic brain injury. Health SA Gesondheid. 2006;11(4):46–56.

- Kitzmüller G, Asplund K, Häggström T. The long-term experience of family life after stroke. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(1):E1–E13.

- Michel G, Taylor N, Absolom K, et al. Benefit finding in survivors of childhood cancer and their parents: further empirical support for the benefit finding scale for children. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36(1):123–129.

- Morris JN, Turnbull D, Martini A, et al. Coping and its relationship to post-traumatic growth, emotion, and resilience among adolescents and young adults impacted by parental cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020;38(1):73–88.

- Bell MF, Bayliss DM, Glauert R, et al. Developmental vulnerabilities in children of chronically ill parents: a population-based linked data study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019;73(5):393–400.