Abstract

Purpose

People with multiple sclerosis (pwMS) want disease-specific dietary advice to reduce the confusion around diet. This study used co-design principles to develop an online nutrition education program for pwMS.

Methods

Mixed-methods (multiphase sequential design). Phase 1: online survey (n = 114 pwMS) to explore preferred content and characteristics of a nutrition program and develop a draft program. Phase 2: feedback on the draft program from stakeholders (two meetings; n = 10 pwMS and multiple sclerosis (MS) health professionals) and pwMS (two workshops; n = 6) to produce a full program prototype. Phase 3: cognitive interviews (n = 8 pwMS plus 1 spouse) to explore acceptability and ease of comprehension of one module of the program, analysed using deductive content analysis.

Results

Preferred topics were included in the program, which were further developed with consumer feedback. Cognitive interviews produced four themes: (1) positive and targeted messaging to motivate behaviour change; (2) “not enough evidence” is not good enough; (3) expert advice builds in credibility; and (4) engaging and appropriate online design elements are crucial.

Conclusions

Positive language appears to improve motivation to make healthy dietary changes and engagement with evidence-based nutrition resources. To ensure acceptability, health professionals can use co-design to engage consumers when developing resources for pwMS.

Co-designed nutrition education programs can help people achieve high-quality diets in line with recommendations, but very few programs exist for people with multiple sclerosis (MS), and none were co-designed

The participatory research in this study was instrumental in ensuring that important information regarding program acceptability was identified

Co-design can ensure that the language is appropriate for the target audience, and positive language appeared to improve motivation in people with MS to engage with the online nutrition education program

Where practical and feasible, health professionals should collaborate with MS consumers when developing resources, and use positive, empowering language

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

The nutrition recommendation for people with multiple sclerosis (MS) is to follow the national dietary guidelines [Citation1,Citation2], but people with MS (pwMS) are sceptical of this generalised dietary advice given the seriousness of the disease [Citation3,Citation4]. PwMS commonly use the internet to search for information on diet and MS [Citation5,Citation6] and around 20% have reported following a specific diet [Citation7]. However, the information retrieved online is conflicting [Citation5], resulting in confusion about where to seek credible nutrition information [Citation4]. An MS-specific nutrition education program would help to reduce the confusion and provide pwMS with knowledge and skills to assess the credibility of nutrition information [Citation4]. However, very few nutrition educations programs for pwMS exist or have been co-designed with pwMS [Citation8].

Nutrition education programs are defined as a set of educational strategies designed to improve nutrition-related behaviours and dietary intakes [Citation9], and the best practice principles for the design of nutrition programs include an increasing recognition of co-design [Citation10]. The principles of co-design can be achieved using participatory research methods which capture the lived experiences of consumers (i.e. pwMS) and stakeholders (i.e. MS health professionals) and produce programs that meet their needs, while also considering their beliefs and values [Citation11,Citation12]. Co-design also ensures that the visuals, language, activities, and underlying theories and behaviour change techniques (BCTs, active components of interventions that support behaviour change) [Citation13] are appropriate for the audience [Citation14]. Cognitive interviewing is one example of a participatory research method that can be used while developing and testing programs to help identify features that are not well accepted, including visual design, language, and the content [Citation15]. Nutrition interventions that have been co-designed with consumers and stakeholders are more acceptable and result in positive health behaviour change [Citation10]. Despite this, evidence of any participatory research for existing nutrition education programs for pwMS is very limited, evident in only one program as identified in our recent scoping review [Citation8].

Our previous research [Citation4,Citation8,Citation16,Citation17] identified relevant program characteristics, suitable theoretical frameworks (the self-determination theory [Citation18] and context, executive and operational systems (CEOS) theory [Citation19]), suitable BCTs, and desired topics, which were used to draft a framework for a potential nutrition education program. Building on that draft framework, we aimed to use co-design principles to develop an online nutrition education program for pwMS. The objectives were to: (1) collaborate with pwMS and MS health professionals to identify the preferred content and characteristics of a nutrition education program; and (2) explore the acceptability and ease of comprehension of one module of an online nutrition education program for pwMS.

Methods

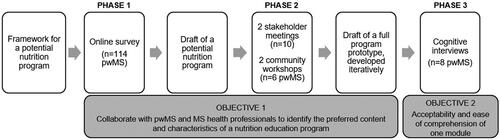

We used a multiphase mixed-methods research design, with sequential phases conducted over a period of time within one overall study [Citation20] ().

Figure 1. The phases of a co-design approach for developing a nutrition education program for people with multiple sclerosis, using a mixed-methods research design. pwMS, people with multiple sclerosis.

Preferred content and characteristics of a nutrition education program: consumer and stakeholder collaboration

Quantitative survey (phase 1)

Study design and participants

A cross-sectional online survey was used to determine the interest and preferred characteristics and content of a nutrition education program for pwMS. Participants were purposively sampled from a local MS organisation, MS Western Australia (MSWA, approximately 2400 members). Members with MS were emailed a description of the research and a hyperlink to the survey. A recruitment notice was also placed in the MSWA e-newsletter. There were no exclusion criteria. The Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (HRE2020-0484).

Data collection

The survey was developed using key topics identified from four sources: (1) MS and diet scientific literature [Citation2,Citation21–27]; (2) our previous focus groups [Citation4]; (3) website topic review of six international MS organisations; and (4) input from the research team. All authors pilot-tested the survey prior to recruitment, which was distributed using Qualtrics software (Version 2020, Provo, UT) between September and October 2020. Participants provided online informed consent. We collected sociodemographic data for sex, age, time since diagnosis, type of MS, highest level of education, and employment status. The survey contained 22–34 questions, depending on participants’ responses. The questions related to dietary changes made since diagnosis, reasons for making dietary changes, sources of dietary information, interest in a nutrition education program, and the preferred characteristics and content of a nutrition education program. Participants selected from one of four nutrition education program formats (face-to-face seminar, online seminar, face-to-face group discussion, or online group discussion), and selected preferences for length, number, and frequency of sessions. Participants selected topics from five options (food, diets, nutrients/supplements, research, and other). Each topic had various subtopics to select from. Participants could select multiple subtopics and submit open-ended answers in a free-text field.

Data analysis

Categorical variables were reported as percentage and number; normally distributed variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD); and non-normal distributions as median and interquartile range (IQR). Differences in participant characteristics by “interested in a nutrition education program” versus “not interested” were analysed using t-tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and chi squared tests, as appropriate. We used multivariable logistic regression to explore all the potential predictors of interest in a nutrition education program collected in our survey: sex, age (years), time since diagnosis (years), level of education (year 12 equivalent or below; trade/apprenticeship or technical certificate/diploma; bachelor’s degree or higher), employment status (employed; retired; not working), dietary changes made since diagnosis of MS (yes/no), type of MS, and current adherence to a specific diet (yes/no). Using backward stepwise regression, only the predictors that remained statistically significant at p ≤ 0.1 were retained in the final model. Data were analysed using Stata software (version 16.1, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Developing a draft of a potential nutrition education program

We developed a draft of a potential nutrition education program by building on the framework outlined in the introduction and findings from the online survey (phase 1). The draft program was developed using guidelines for developing complex interventions [Citation28], guidelines for effective health promotion interventions for individuals with disabilities [Citation29], our previous quantitative and qualitative research involving pwMS and MS health professionals [Citation4,Citation8,Citation16,Citation17], and input from our project stakeholder advisory group (two pwMS, a neurologist, an MS nurse, an MS senior counsellor, three MS Accredited Practising Dietitians, an Accredited Practising Dietitian with MS experience, and a clinical psychologist and MS researcher; five meetings held between 2019 and 2021). The themes identified from our six focus groups with pwMS (n = 34) were incorporated into the program, namely: confusion about where to seek dietary advice (and how to judge the credibility of information); scepticism towards national dietary guidelines; barriers to dietary changes; and wanting dietary guidelines that are tailored for MS [Citation4].

We identified suitable BCTs for the potential program that were commonly used in nutrition education programs for people with neurological diseases [Citation8], effective emotional wellness programs for pwMS [Citation16], brief nutrition interventions for adults [Citation30], and nutrition interventions for adults with mobility-impairing neurological or musculoskeletal conditions [Citation31]. Some of the BCTs included were instruction on how to perform the behaviour, demonstration of the behaviour, behavioural practice/rehearsal, credible source, information about health consequences, social comparison, social support, goal setting, action planning, problem solving, self-monitoring of behaviour, framing/reframing, and prompts/cues. The BCTs were incorporated into the draft program through text (instruction on how to perform the behaviour, information about health consequences), expert videos (credible source), discussion board topics (social comparison), and activities relating to the module topics (e.g. demonstration of the behaviour, goal setting, action planning, problem solving, behaviour practice/rehearsal, self-monitoring of behaviour, etc).

Stakeholder meetings and consumer workshops (phase 2)

We consulted with stakeholders and MS consumers to provide feedback on the draft of the potential nutrition education program. Two online meetings were held in June and July 2021 with the project stakeholder advisory group (n = 10, meeting duration = one hour). Two online workshops were conducted with MS consumers in July and August 2021, involving pwMS who had been diagnosed within the previous five years (n = 6, workshop duration = three hours). Note: the inclusion criterion of diagnosis of MS within the previous five years was selected as this was the initial target audience for the program; however, the stakeholders and MS consumers in this phase of the research suggested that the program would be potentially useful to people with all stages of MS. Workshop participants were recruited through the Consumer and Community Involvement Program (CCIP, part of the Western Australian Health Translation Network, which aims to support consumers, community members, and researchers to work in partnership https://cciprogram.org/). The CCIP advertised the consumer involvement positions on their website, social media, and in their e-newsletter. Interested consumers submitted an expression of interest via the CCIP website, and a CCIP Support Officer phoned each applicant to discuss their background, interest in the project, and availability (n = 21). The CCIP Support Officer phoned the referees of 13 shortlisted applicants to enquire about their communication skills and other strengths that would be relevant to the workshops. The Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (HRE2019-0179) and participants provided written, informed consent.

The meetings and workshops were facilitated by RDR (a nutritionist with qualitative experience). Participants were informed about the goals of the research. Data collected from meetings and workshops were in the form of notes (no video or audio recordings). The participants provided input and feedback on the program topics and content, and the proposed supporting activities, such as short, optional quizzes, a discussion board forum (including the topics for discussion and the rules for engagement) and the activities that reflected the BCTs, for example, goal setting and problem solving. Informal data analysis involved the confirmation or rejection of the topics and content discussed, as well as the addition of missing information or further points to consider. The workshop participants also suggested some example goals, barriers to achieving goals, and positive phrases to be included in an activity book.

All the feedback from the first meeting and workshop was incorporated into the program, and the program updates were presented to the stakeholders at the second meeting and workshop for confirmation/participant checking and to seek any amendments.

Developing a draft of a full nutrition education program prototype

A draft of a full nutrition education program prototype was iteratively developed (program outline, Supplementary Appendix table 1), by building on the draft of a potential program (post-phase 1) and the findings from the stakeholder meetings and consumer workshops (phase 2). The prototype program was proposed to run for six weeks and be asynchronous, where one topic/module would be released each week at a set time, and participants would aim to complete each module within the week. The program contained goal setting and goal re-evaluating activities and discussion board threads to engage in online discussions). Short optional quizzes were included at the end of each topic to provide participants with feedback on their learning and serve as a source of external motivation that aligned with the self-determination theory [Citation18].

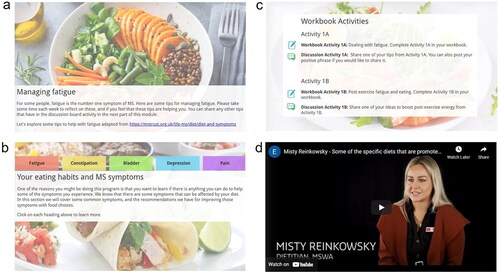

An online version of one module was produced by an instructional designer for testing with pwMS (phase 3). The content of the module included the evidence for diet and MS, how diet may affect symptoms of MS, and tips for managing fatigue in relation to shopping, preparing, and cooking foods (). The objectives of the module were to (1) discuss the evidence for how different ways of eating, foods, and supplements might affect the symptoms and progression of MS; (2) describe the ways that your eating habits can affect MS symptoms (fatigue, constipation, bladder issues, depression, and pain); (3) describe how your MS symptoms might affect your eating habits; and (4) identify ways you can manage fatigue when shopping for, preparing, and cooking food. The content was delivered using a range of modes including text, images, interactive graphics, and videos featuring expert interviews ().

Figure 2. Screenshots from a draft nutrition education program prototype showing the various modes of content delivery (a. text and images; b. interactive graphics; c. activities to support behaviour change; d. an expert video featuring an MS dietitian). MS, multiple sclerosis.

Table 1. Overview of the content for one module of an online nutrition education program for people with MS.

Acceptability and ease of comprehension of one module of a nutrition education program. Cognitive interviews (phase 3)

Cognitive interviews were used to assess the acceptability and ease of comprehension of one module of the online nutrition education program prototype.

Study design and participants

We used a qualitative study design with purposive sampling. Participants were recruited from pre-existing sampling frames [Citation15], specifically, previous research participants who had consented to contact about future studies (recruited from MSWA, as described in phase 1 and via the CCIP described in phase 2). The sampling frames were used to select potential participants based on the sampling considerations. The primary sampling consideration was time since diagnosis (two categories: <3 years since diagnosis, and 3–5 years since diagnosis). Within those two categories, the sampling sub-criteria were sex, age (≤40 years and >40 years, given the mean age at diagnosis is 20–40 years [Citation1]), and level of education (trade/apprenticeship or technical certificate/Diploma or below, and Bachelor’s or Postgraduate degree). Within the two main categories (<3 years and 3–5 years since diagnosis), we aimed to recruit enough participants to cover each of the dichotomous sub-criteria) (minimum n = 6) [Citation15]. Potential participants were contact by email with information about the study and were invited to participate in a one-to-one online interview with the first author (RDR) (n = 11) using Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, United States). We adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist [Citation32]. The Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (HRE2019-0179).

Data collection

Individual interviews were conducted between November 2021 and January 2022. Participants provided online informed consent and completed a short demographic questionnaire prior to the interview which collected data on highest level of education and employment status. The interviewer (RDR) explained the purpose of the research and the reasons for her interest in the research topic. Time was spent building rapport with participants before the interview began. The participants were shown an overview of the draft nutrition education program prototype and worked through one module of the online program, which contained around 4000 words. The estimated interview completion time was one hour. Participants were instructed by the interviewer to “think aloud” (verbalise their thoughts) throughout the interview [Citation15]. Verbal probing was used to determine the participants’ thought processes, including general probes such as “tell me what you’re thinking about” and “do you think that section was easy or difficult to understand?,” and theory-driven probes based on the types of motivation from the self-determination theory (see Supplementary Appendix table 2 for question guide). Interviewer observations noted throughout the interview included: how participants worked through each page, evidence of skim-reading, key phrases used, any emotional responses to the content, and visual and aural signs of demeanour (e.g. tone and pitch of voice or body language that indicated interest, excitement, fatigue, etc.). The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data collection continued until each of the sampling criteria were achieved. The transcripts were emailed to participants for comments and/or corrections and one edited transcript was returned.

Data analysis

Transcript data and interviewer notes were summarised using the Framework method [Citation15] in NVivo (version 12.6.0, QSR International Pty Ltd). Data management involved two steps. Firstly, the raw data for each interview was entered into an “interview summary document” using a set template for each interview. Each summary document contained interview information (date, time, participant pseudonym, participant demographics, interview duration, summary), transcript data from the think aloud and general probes for each section, and interviewer notes. Secondly, the data from each interview was combined into a single dataset to create a thematic framework matrix. Each row contained participant data and the columns contained the areas of investigation (each page of the program). Thus, data could be read vertically for each page across all cases, or horizontally as a complete record for each participant.

We analysed the data using deductive content analysis [Citation33]. The first round of coding involved labelling transcripts and interview notes with five codes that aligned with the research objectives (ease of comprehension, overall acceptability, content acceptability, language acceptability, and format acceptability). Round two involved dichotomising each initial code (e.g. format acceptable and format not acceptable), and the third round involved explanatory analysis [Citation15] to identify reasons for those codes (e.g. format was not acceptable due to too much text), resulting in 35 codes. We then reduced the number of codes by grouping relevant codes and reducing redundant codes, which produced three main themes. Data analysis was conducted by the interviewer (RDR) and emerging themes were discussed with the research team (AB and LJB). Final themes were confirmed by an experienced qualitative researcher (AB) who independently reviewed all transcripts. A summary of the themes was emailed to the participants and there were no suggested changes returned.

Results

Preferred content and characteristics of a nutrition education program. Consumer and stakeholder collaboration

A total of 127 pwMS completed the survey (). The majority were female (79%) and diagnosed with relapsing-remitted MS (76%). The mean age was 52 years and the median time since diagnosis was 10 years. Over half of the participants (n = 73; 57.5%) had made dietary changes since their diagnosis and less than one third of the participants (n = 32; 27.6%; data missing from n = 11) were currently adhering to a specific diet. Of the 114 participants who responded to the questions regarding interest in a nutrition program, the majority (72%) were interested. Those who were interested were more likely to have made dietary changes since their MS diagnosis (p = 0.007) and were currently adhering to a specific diet (p = 0.021), compared to those who were not interested in a nutrition education program. There were no other statistically significant differences.

Table 2. Survey results showing participant characteristics by interest in a nutrition education program for people with MS (n = 127).

Program topics of interest were answered by 103 participants. The most preferred topics were: foods (89%); nutrients/supplements (70%); current/emerging research (62%); and diets (51%). The most popular subtopics were: foods to avoid and food to eat; vitamin D; omega 3 supplements; the Overcoming MS diet; and intermittent fasting. The preferred characteristics of a nutrition education program were answered by 100 participants. The highest-ranked preferences were online (58%), one-hour sessions (50%), and “no preference” for number of sessions (46%). There was no clear preference for the number of frequency of sessions (“no preference” 32%, monthly 25%, fortnightly 22%, weekly 21%).

In the multivariable analysis (complete data available for n = 114), the only statistically significant associations were: compared to males, females were nearly three times more likely to be interested in a nutrition education program (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.82, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03–7.73, p = 0.044); and participants who reported making dietary changes since diagnosis were 3.5 times more likely to be interested in a nutrition education program compared to those who had not made a dietary change (aOR 3.46, 95% CI 1.44–8.29, p = 0.005) ().

Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression model showing statistically significant participant characteristics and odds of being interested in a nutrition education program for MS (n = 114).

Acceptability and ease of comprehension of one module of a nutrition education program. Cognitive interviews (phase 3)

Eight pwMS and one spouse participated in the cognitive interviews (). The majority were female (78%), with a median (IQR) time since MS diagnosis of 2.5 (3.2) years, (range, 2 months to 5.3 years). Median (IQR, range) interview duration was 76 (42, 41–103) minutes.

Table 4. Sociodemographic characteristics of the cognitive interview participants (n = 9, 8 people with MS and 1 spouse of a person with MS).

The qualitative findings are presented under four overarching themes: (1) positive and targeted messaging to motivate behaviour change; (2) “not enough evidence” is not good enough; (3) expert advice builds in credibility; and (4) engaging and appropriate online design elements are crucial.

Theme 1: Positive and targeted messaging to motivate behaviour change

All participants liked that the language and phrasing used in the module was straight-forward and person-centred. They preferred to read and hear positive messages that were tailored to them, for example, dietary changes that could potentially improve their symptoms. The positive, targeted messages provided them with motivation to change their eating habits, “[it’s] empowering seeing these things” (Nina, 2 years 9 months since diagnosis). When asked about a hypothetical situation where they noticed improvements in their symptoms after making the suggested dietary changes, the motivation to stick with the dietary changes was even greater. All participants said that they would continue with the following five modules if they were enrolled in the online program, as they were keen to learn more: “I am always open to learning new developments very interested the latest research results” (Elena, 5 years 4 months since diagnosis). The majority stated that they would make or consider making changes to their diet based on this module.

Yep, definitely would apply the stuff that I learned to my diet. Mariam, 11 months since diagnosis.

When questioned about the order of the content in the module, all the participants stated that they would prefer to receive the positive messages first. They suggested moving the information about diet and symptoms to the beginning of the module, rather than leaving it at the end, so that the module starts off on a positive note. After viewing one of the expert videos, one participant suggested to redo or edit the video so that it begins with a positive message because starting with a negative message was deflating.

When she says there’s no specific things or one thing I'd recommend, it’s a pretty negative way to start. Um, if this is your first introduction, it’s really negative. She then goes on to say what can be done, but it’s a bit of a deflater […] Reverse it, put the positives first, you know, the benefits of I guess revising your diet with a dietitian would be better outcomes, you know, better weight, better whatever, and then followed by the caveats, the warnings. Camilla, 4 months since diagnosis.

In parts of the module where the message was not clearly targeted to pwMS, the participants were not motivated to make the suggested dietary changes. One example is related to the Australian Dietary Guidelines. Participants expressed that the module did not clearly explain why the Australian Dietary Guidelines were suitable for pwMS (therefore, not targeted information), hence, some of the participants were unsure about the appropriateness of the content on that page. One participant suggested to clearly state why the guidelines are suitable for pwMS, and to relate it back to them and their MS, because referring to the guidelines without explaining why would likely be dismissed by pwMS.

Just saying ‘follow the dietary guidelines’, they’re just gonna say ‘I've heard that before. It’s not going to help my MS’…. Elena, 5 years 4 months since diagnosis.

Theme 2: “Not enough evidence” is not good enough

Statements referring to the current state of evidence for diet and MS, using phrases such as “the evidence is inconclusive,” or “not enough evidence to recommend a specific diet” were frequently referred to as frustrating, despite the statements being acknowledged as the truth.

It’s frustrating to just continually read that there’s not enough evidence to really say either way…. Taylor, spouse of Max.

…Even though it’s the truth […] the fact that a lot of the stuff goes back to like non-conclusive evidence is a frustrating thing. Max, 4 years 2 months since diagnosis.

The message is a little bit disheartening […] everything is inconclusive. Even at the point maybe someone who is like really down in the dumps with their diagnosis would click off it [the program] […] if someone’s really overwhelmed with it, it’s like ‘oh for God’s sake, Google tells me more’. Nina, 2 years 9 months since diagnosis.

Theme 3: Expert advice builds in credibility

The expert videos featuring an MS dietitian and a professor in epidemiology, the links to research studies, and that the program was being developed by an Australian university were considered to give the module credibility. When the information was delivered via an “expert video” format, the participants appeared more receptive to the information, even if it was going against what they were currently doing with their dietary habits.

There’s a lot of like confidence in what they’re saying as well in the videos. I'm looking at the other one, Professor Lucinda, and yeah, it sounds like she knows what she’s on about. Nora, 3 years 4 months since diagnosis.

Knowing how much research we did at the start [when Max was diagnosed], already three slides in I'm like this would have been so good to have […] Because you hear different things [about diet] from different people but reading this it’s like ‘okay well you’ve heard from a nutritionist.’ Taylor, spouse of Max (diagnosed 4 years 2 months prior).

Most of the participants mentioned that they would also like additional videos or audio clips featuring pwMS as the experts and sharing their tips, in addition to the text. The page of the module that listed tips for managing fatigue while shopping, preparing, and cooking foods was of great interest to the participants. Given that the tips had been compiled from pwMS as the experts of managing fatigue on a daily basis, this content added to the credibility of the module by providing another form of expert advice. The content was described as useful, practical advice, and often resonated with what they were already doing or what they had experienced.

I’d - probably [say] this is one of the most useful ones [fatigue management tips] […] It’s actually nice seeing these things on a module teaching me how to manage my fatigue, when the message it’s sending me is I don’t need to be harsh on myself, I am actually doing the right thing. Like putting my dishes in to soak. Nina, 2 years 9 months since diagnosis.

Theme 4: Engaging and appropriate online design elements are crucial

The online design elements were crucial to overall acceptability and comprehension of the module. The layout was described as visually appealing with a good mix of text, interactive graphics, and “nice, short, sharp videos” (Olivia, 2 years 5 months since diagnosis). All of the participants stated that they would continue with next five weeks of the program if they were enrolled, and majority indicated that they would make positive changes to their dietary habits after working through the module.

While overall the module was easy to comprehend, the context on specific pages was misunderstood when key messages did not stand out in the online layout, i.e. all plain black text and without the use of bold text or coloured boxes surrounding key points to highlight main messages. One example of a message that was misunderstood was stating that a healthy diet is important, but no one specific diet is recommended for pwMS. This was perceived as conflicting because the current online design and layout did not visually highlight that “one specific diet” and the dietary guidelines and/or a healthy diet were different; hence, the message was misunderstood as the terms were perceived as interchangeable, particularly when participants skim read. One participant, who skim read through most of the module, appeared overwhelmed as she described this conflicting message as she clicked back and forth between the pages in quick succession.

It talks about how there’s no evidence for, for certain types of foods and everything. But then it says nutrition is important. But then it says this may not work for you. Nora, 3 years 4 months since diagnosis.

All participants skim-read through some of the content at some point during the interviews, which almost always resulted in the context or messages on that particular page being misunderstood. This typically occurred with pages that had numerous paragraphs of text and required scrolling down the page to view all the content. Many participants appeared more fatigued and less interested when they viewed those pages of the module, and conversely, they seemed more energetic and interested while viewing the pages that had shorter sections of text, more videos, and included interactive graphics. Most participants suggested reducing the amount of text on certain pages and including more videos throughout the module, and one person suggested using bold words to highlight key messages.

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

In this paper we have described how we used co-design principles to collaborate with MS consumers and stakeholders to develop a nutrition education program for pwMS. We surveyed pwMS to identify the preferred content and characteristics of a nutrition education program and used the findings to develop a draft of a potential program. We further engaged with MS consumers and stakeholders through online meetings and workshops to refine the draft program, resulting in a full program prototype of an online nutrition education program. The prototype program was proposed to be asynchronous, contain six modules, and run for six weeks (one module released/opened per week). The program prototype contained content and activities that aligned with suitable BCTs, including goal setting and discussion board threads relating to content and practical activities. We used an instructional designer to produce one module in an online format and explored the acceptability and ease of comprehension using cognitive interviews. The interviews highlighted key elements that influenced acceptability and/or ease of comprehension, including positive messaging to motivate behaviour change, avoiding phrases that are perceived as negative, such as “not enough evidence,” expert advice including pwMS as experts to provide credibility, and the importance of engaging and appropriate online design elements.

PwMS are interested in online nutrition resources [Citation34], and this paper highlights the importance of using co-design principles to develop resources that suit their online learning needs. PwMS are regular users of online technologies [Citation35,Citation36] and the internet is a suitable platform to deliver nutrition education, while addressing the inherent challenges associated with dietary behaviour change [Citation34]. The challenges can be addressed by using appropriate behavioural supports in an online learning environment, including the BCTs described in this paper, such as goal setting and self-monitoring [Citation34]. However, a recent study has reported that pwMS had poorer internet-based technology skills (i.e. skills required to use computers, smartphones, and tablets) compared to people without MS [Citation37], emphasising the need for online education to be delivered via an easy-to-use platform to meet their online learning needs. Given that some of key determinants of the acceptability of eHealth interventions for pwMS include an easy-to-use program, having a user-centric design, and content that is targeted to pwMS [Citation38], co-design methods are important to develop acceptable online programs.

A possible consequence of not using co-design principles is research waste: programs that do not meet the needs of the end-users can potentially waste research funds and resources [Citation39]. Co-design can help avoid this waste by ensuring that both the content needs and the online delivery needs of pwMS are met, therefore potentially increasing uptake and effectiveness of the program [Citation10]. Using co-design principles by collaborating with MS consumers while developing a nutrition education program enabled us to create an online prototype program that was easy to comprehend and aligned with their online learning needs. However, developing relationships and building trust with consumers to avoid conflict and feelings of tokenistic involvement in health research requires additional time and financial resources [Citation39]. It is also likely that the perspectives of people with MS regarding to topics of interest could change over time, given the changes mapped in the diet and MS literature in a recent data-driven literature review [Citation40]. For example, articles about fish and dairy date back to the 1990s, sodium did not appear until after 2000, caffeine was not reported until 2010, and the past five years has produced studies on seaweed, coconut oil, and meat [Citation40]. Despite the possible changing topic preferences, this manuscript presents elements from the cognitive interviews that may persist over time, such as use of positive and empowering language, avoiding referring to “not enough evidence,” and the inclusion of experts to provide credibility (including pwMS as the experts).

The participants described their interest in making positive dietary changes and continuing with the following five weeks of the program prototype. The use of co-design practices aimed to ensure that the needs and priorities of pwMS were met. Some of the needs and priorities addressed in our program were strategies to overcome common barriers to making healthy dietary changes, which were discussed by pwMS during our focus group research [Citation4]. These strategies greatly contributed to the module acceptability as they were relatable to the audience. Our findings are supported by those of Sesel et al. [Citation41], who developed a web-based mindfulness program for pwMS using co-design principles. Their program was described as acceptable and highly relatable, as the content was also targeted to the needs and experiences of pwMS [Citation41]. These findings have also been found in physical activity interventions for pwMS, where addressing the needs and desires of pwMS improves adherence to physical activity recommendations [Citation42]. Given that co-designed nutrition interventions show the most promise for positive health behaviour change [Citation10], future nutrition education programs should adopt co-design principles during the development and testing stages to ensure that the needs of pwMS are met and the program is acceptable.

Conducting cognitive interviews at the full prototype stage of one module of the online nutrition education program provided important information that could impact on the acceptability of the final program. Specifically, the interviews revealed that language was key in influencing program acceptability, and the preference was for positive messages that included practical advice. The preference for positive tone when discussing diet and nutrition was not surprising, given that pwMS make dietary changes as a way to feel in control of their disease [Citation3] and taking action provides them with a source of hope [Citation43]. This also aligns with expert advice that nutrition messages should be practical, motivating, and focus on what can be gained or achieved [Citation44,Citation45]. Practical advice and tips may also provide external motivation to further support positive dietary behaviour change [Citation18]. The participatory research approach employed in this study was instrumental in ensuring that important information regarding nutrition program acceptability was identified and therefore could be addressed in a full prototype version of the program.

The main limitation of this study relates to self-selection bias, which may have resulted in an over-representation of interest in a nutrition education program in both the online survey and the cognitive interviews. Furthermore, the survey was conducted online which may have influenced the preference for an online program. However, given the high employment rate of pwMS [Citation46] and accessibility for eHealth interventions amongst pwMS [Citation38], this is unlikely. Lastly, the qualitative findings may not be representative of the wider MS community as we did not capture the views of adolescents or children with MS or people who do not identify as either female or male, and the perspectives from the six MS consumers providing feedback on the draft program (phase 2 workshops) were limited to pwMS who had been diagnosed within the previous five years.

Conclusion and recommendations

Collaborating with MS consumers and stakeholders at multiple stages while developing a nutrition education program enabled us to create an acceptable and easy to understand program with content that aligned with their needs. Without the final stage of consumer engagement (the cognitive interviews), it is possible that the future program would not be as well-received, given the valuable insights revealed during the interviews. Specifically, the preference for positive and targeted messaging to motivate behaviour change and engagement, dissatisfaction with the phrase “not enough evidence,” and the importance of suitable online design elements. This paper has highlighted the importance of co-design to ensure that the language is appropriate, as positive language appears to improve the motivation to make healthy dietary changes and engagement with evidence-based nutrition resources. Where practical and feasible, nutritionists and dietitians should use a variety of participatory methods to engage with MS consumers and stakeholders when developing resources for pwMS to ensure acceptability.

Using the findings from the cognitive interviews, we have developed a full program prototype which has recently been tested in a feasibility study; data analysis is underway (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12622000276752).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.2 KB)Acknowledgements

This study will partially fulfil the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Philosophy in the Curtin School of Population Health, Curtin University, for RDR. Thank you to MSWA for assistance in recruiting. We thank the participants who took part in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- MS Research Australia. Modifiable lifestyle factors and MS: a guide for health professionals. MS Research Australia. [cited 2021 Apr 20]. https://msra.org.au/modifiable-lifestyle-guide-2020/health-professionals/guide/.

- Evans E, Levasseur V, Cross AH, et al. An overview of the current state of evidence for the role of specific diets in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;36:101393–101396.

- Russell RD, Black LJ, Sherriff JL, et al. Dietary responses to a multiple sclerosis diagnosis: a qualitative study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2019;73(4):601–608.

- Russell RD, Black LJ, Begley A. Navigating dietary advice for multiple sclerosis. Health Expect. 2021;24(3):853–862.

- Beckett JM, Bird M-L, Pittaway JK, et al. Diet and multiple sclerosis: scoping review of web-based recommendations. Interact J Med Res. 2019;8(1):e10050-e10050.

- Marrie RA, Salter AR, Tyry T, et al. Preferred sources of health information in persons with multiple sclerosis: degree of trust and information sought. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(4):e67.

- Marck CH, Probst Y, Chen J, et al. Dietary patterns and associations with health outcomes in Australian people with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75(10):1506–1514.

- Russell RD, Black LJ, Begley A. Nutrition education programs for adults with neurological diseases are lacking: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2022;14(8):1577.

- Contento I, Balch G, Bronner Y, et al. The effectiveness of nutrition education and implications for nutrition education policy, programs, and research: a review of research. J Nutr Educ, Vol. 1995;27(6):275.

- Tay BSJ, Cox DN, Brinkworth GD, et al. Co-design practices in diet and nutrition research: an integrative review. Nutrients. 2021;13(10):3593.

- McGill B, Corbett L, Grunseit AC, et al. Co-produce, co-design, co-create, or co-construct - who does it and how is it done in chronic disease prevention? A scoping review. Healthcare. 2022;10(4):647.

- Agency for Clinical Innovation. Patient experience and consumer engagement – a guide to build co-design capability. [cited 2022 May 4]. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/502240/Guide-Build-Codesign-Capability.pdf.

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

- Baker S, Auld G, Ammerman A, et al. Identification of a framework for best practices in nutrition education for low-income audiences. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020;52(5):546–552.

- Collins D, editor. Cognitive interviewing practice. London: SAGE, 2015.

- Russell RD, Black LJ, Pham NM, et al. The effectiveness of emotional wellness programs on mental health outcomes for adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;44:102171.

- Russell RD, Black LJ, Begley A. The unresolved role of the neurologist in providing dietary advice to people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;44:102304.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: a macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can Psychol. 2008;49(3):182–185.

- Grech LB, Borland R. Using CEOS theory to inform the development of behaviour change implementation and maintenance initiatives for people with multiple sclerosis. Curr Psychol. 2021. DOI:10.1007/s12144-021-02095-7

- Zoellner J, Harris JE. Mixed-methods research in nutrition and dietetics. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(5):683–697.

- Riemann-Lorenz K, Eilers M, Schulz K-H, et al. Dietary interventions in multiple sclerosis: development and pilot-testing of an evidence based patient education program. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165246.

- Fitzgerald KC, Tyry T, Salter A, et al. A survey of dietary characteristics in a large population of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;22:12–18.

- Farinotti M, Vacchi L, Simi S, et al. Dietary interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5(5):CD004192–48.

- Bagur MJ, Murcia MA, Jiménez-Monreal AM, et al. Influence of diet in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2017;8(3):463–472.

- Pommerich UM, Brincks J, Christensen ME. Is there an effect of dietary intake on MS-related fatigue? – a systematic literature review. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;25:282–291.

- Katz Sand I. The role of diet in multiple sclerosis: mechanistic connections and current evidence. Curr Nutr Rep. 2018;7(3):150–160.

- Mische LJ, Mowry EM. The evidence for dietary interventions and nutritional supplements as treatment options in multiple sclerosis: a review. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2018;20(4):8.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ, Vol. 2008;337(7676):a1655–983.

- Drum CE, Peterson JJ, Culley C, et al. Guidelines and criteria for the implementation of community-based health promotion programs for individuals with disabilities. Am J Health Promot. 2009;24(2):93–101, ii.

- Whatnall MC, Patterson AJ, Ashton LM, et al. Effectiveness of brief nutrition interventions on dietary behaviours in adults: a systematic review. Appetite. 2018;120:335–347.

- Plow MA, Moore S, Husni ME, et al. A systematic review of behavioural techniques used in nutrition and weight loss interventions among adults with mobility-impairing neurological and musculoskeletal conditions. Obes Rev. 2014;15(12):945–956.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115.

- Silveira SL, Richardson EV, Motl RW. Desired resources for changing diet among persons with multiple sclerosis: qualitative inquiry informing future dietary interventions. Int J MS Care. 2022;24(4):175–183.

- Haase R, Schultheiss T, Kempcke R, et al. Use and acceptance of electronic communication by patients with multiple sclerosis: a multicenter questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(5):e135-e135.

- Marrie RA, Leung S, Tyry T, et al. Use of eHealth and mHealth technology by persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;27:13–19.

- Goverover Y, Stern BZ, Hurst A, et al. Internet-based technology in multiple sclerosis: exploring perceived use and skills and actual performance. Neuropsychology. 2021;35(1):69–77.

- Scholz M, Haase R, Schriefer D, et al. Electronic health interventions in the case of multiple sclerosis: from theory to practice. Brain Sci. 2021;11(2):180.

- Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co-design in health: a rapid overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1):17.

- Qu X, Walsh EI, Cherbuin N, et al. Mapping the literature on diet and multiple sclerosis: a data-driven approach. Nutrients. 2022;14(22):4820.

- Sesel A-L, Sharpe L, Beadnall HN, et al. Development of a web-based mindfulness program for people with multiple sclerosis: qualitative co-design study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e19309-e19309.

- Hale LA, Smith C, Mulligan H, et al. “Tell me what you want, what you really really want…”: asking people with multiple sclerosis about enhancing their participation in physical activity. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(22):1887–1893.

- Soundy A, Benson J, Dawes H, et al. Understanding hope in patients with multiple sclerosis. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(4):344–350.

- Fitzgibbon M, Gans KM, Evans WD, et al. Communicating healthy eating: lessons learned and future directions. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(2 Suppl):S63–S71.

- Khandpur N, De Morais Sato P, Neto JRG, et al. Developing and refining behaviour-change messages based on the Brazilian dietary guidelines: use of a sequential, mixed-methods approach. Nutr J. 2020;19(1):66.

- Taylor KL, Hadgkiss EJ, Jelinek GA, et al. Lifestyle factors, demographics and medications associated with depression risk in an international sample of people with multiple sclerosis. BMC Psychiatry, Vol. 2014;14(1):327.