Abstract

Purpose

To investigate if a 12-week community-based exercise program (FitSkills) fostered positive attitudes towards disability among university student mentors.

Methods

A stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial was completed with 4 clusters. Students were eligible to be a mentor if enrolled in an entry-level health degree (any discipline, any year) at one of three universities. Each mentor was matched with a young person with a disability and the pair exercised together at the gym twice a week for an hour (24 sessions total). At 7 times over 18 months, mentors completed the Disability Discomfort Scale to indicate their level of discomfort when interacting with people with disability. Data were analysed according to the intention to treat principles using linear mixed-effects models to estimate changes in scores over time.

Results

A total of 207 mentors completed the Disability Discomfort Scale at least once, of whom 123 participated in FitSkills. Analysis found an estimated reduction of 32.8% (95% confidence interval (CI) −36.8 to −28.4) in discomfort scores immediately after exposure to FitSkills across all four clusters. These decreases were sustained throughout the remainder of the trial.

Conclusions

Mentors reported more positive attitudes towards interacting with people with disability after completing FitSkills with changes retained for up to 15 months.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Participating in a 12-week community physical activity program fostered lower levels of discomfort in interacting with young people with disability among university student mentors.

Student mentor’s positive attitudes to disability were sustained for up to 15 months following the program.

Mentors with no previous experience of disability had a larger reduction in discomfort scores than mentors who had previous disability experience.

We recommend short-duration (24 hours over 12 weeks) community-based experiences such as FitSkills to positively impact how entry-level health professional students relate to young people with disability.

Introduction

An estimated 50% of students entering university to train as health professionals say they have had no contact with a person with a disability either through family, social connections or work [Citation1]. In the absence of other experiences, their attitudes towards disability can often reflect the predominant societal view of ‘tragedy’ [Citation2]. Negative attitudes towards disability among health professionals can have adverse consequences for people with disability by limiting access to quality healthcare and health services [Citation2–4]. For example, medical students reported feeling less comfortable when working with people with disability [Citation5]. Negative attitudes during interactions can also adversely influence the willingness of health professionals to work with people with disability [Citation6]. People who have more contact with people with disability tend to have more positive attitudes [Citation7,Citation8], suggesting attitudes to disabilities are not fixed. Contact theory proposes attitudes can change in response to frequent, good-quality interactions with people with disability [Citation9]. This is more likely when interactions include: relationships of equal status, working towards a common goal, the absence of competition and acknowledgement of the same social norms [Citation10].

Previous studies show the attitudes toward disability of physiotherapy students can change positively in response to community-based experiences [Citation11,Citation12]. Short-term (8–12 week) community experiences, where physiotherapy students supported the participation of a young person with a disability in exercise, have enabled those students to become more comfortable interacting with people with disability [Citation12,Citation13], while simultaneously developing professional skills [Citation12,Citation13]. A feature of one such program, called FitSkills, is the mutual benefits gained by participants. The young person with a disability receives the support they need to exercise and the student mentor has the opportunity to become acquainted with a young person with a disability [Citation11]. Positive changes in attitudes were found immediately after the FitSkills student mentoring experience [Citation12–14] and these changes were retained, with some regression to the mean, for up to three months [Citation1].

Previous studies focused on the attitudes of physiotherapy students [Citation11,Citation12,Citation14]; it is unknown if the positive effects of volunteering as a mentor for a community exercise program would be the same for students of other health disciplines. Previous data lacked a control group and had only short-term follow-up. Therefore, it is unknown whether a change in students’ attitudes was due to maturation or exposure to university curricula and whether any changes were sustained. Also, previous studies have not routinely described the severity of the disability of young people with disability. It is possible students’ attitudes are influenced by the complexity of the disability of the young person with whom they spend time. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to investigate if FitSkills fostered positive attitudes towards interacting with people with disability among student mentors from across health disciplines. The secondary aims were to investigate how demographic characteristics and adherence to the program, moderated any effect on attitudes.

Methods

Study design

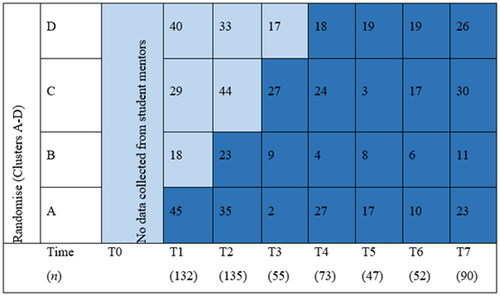

Data for this quantitative study were collected as part of a stepped-wedge cluster randomised trial. This trial design involves the sequential transition of clusters (in this case community gyms) from control to intervention phases in a randomised order. The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12617000766314) and a trial protocol has been published [Citation15]. During the trial, an intervention (FitSkills) was sequentially introduced to 11 community gyms (sites) in random order () in Melbourne, Australia. After an initial period when no sites were exposed (control phase), at regular intervals sites crossed from the control to the intervention phase [Citation16]. Participants contributed repeated observations under control and intervention phases up to seven times at three-month intervals (). The trial design comprised four groups (clusters) each containing 2 to 3 randomly allocated gym sites. A member of the research team (LP) not involved in recruitment, assessment or intervention delivery, randomised the order of the sites using web-based software. Ethical approval was granted by university ethics committees. Participants provided written informed consent to take part. Data were collected data between June 2018 and May 2020.

Figure 1. Schematic of student mentor responses to Disability Discomfort Scale questionnaire across stepped wedge design. Each ‘step’ is 3 months in duration. There are 8 assessment points (T0 to T7) and assessments occur at the start of each new step. Light shading represents the control period. Dark shading represents the intervention period. Data were not collected from student mentors at T0.

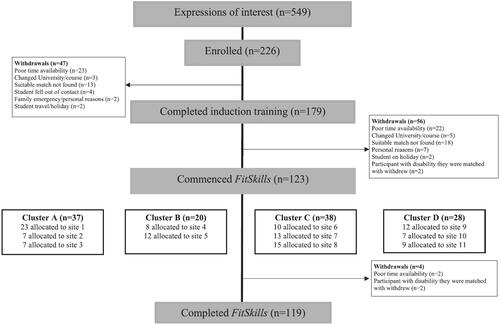

Figure 2. Flow of student mentors through the trial.

Participants

Students were eligible to participate as mentors if they were enrolled in an entry-level allied health or health science course (any discipline and year level) at three universities in Melbourne [Citation17]. Mentors were invited to take part if they were matched with a young person with a disability who had enrolled in the trial based on their residential location or willingness to travel to a nearby suburb. Mentors volunteered their time but received up to $200AUD for travel expenses. Some mentors received credit towards the clinical requirements of their degree course.

The young people with disability who participated were aged 13 to 30 years, identified as having a disability (any type) and could follow simple verbal instructions in English. These young people were on average aged 20.8 ± 5.0 years, 37% were female, had cerebral palsy (36%), Down syndrome (25%) and/or autism spectrum disorder (18%), and had an average of one co-morbidity (e.g., mental health condition, overweight/obesity, epilepsy, asthma [Citation17]. Young people with disability were excluded if they regularly participated in a high-intensity exercise program during the previous 3 months, had an acute or concurrent medical condition rendering them unfit to take part in moderate-to-high intensity exercise, or had a significant psychological or behavioural problem that severely impacted their ability to participate.

Intervention

FitSkills is an evidenced-based 12-week, a student-mentored, community-based exercise program for young people with disability [Citation18–21]. Each young person with a disability was matched with a mentor from their locality and the pair exercised together at their local gym twice weekly for one hour each session (24 sessions in total) [Citation15]. To promote a peer relationship, the mentor exercised alongside the young person with a disability. After baseline data collection mentors completed a 3-h training session, including program content, motivational and support strategies for the young people with disability and an orientation to the gym setting and equipment.

The exercise content was individually tailored to the young person with a disability, prescribed by exercise professionals from the research team after a consultation at their gym site and guided by the young person’s goals and preferences [Citation15]. FitSkills sessions were not directly supervised by an exercise professional, but all participants and mentors exercised at community gyms where gym staff worked within the gym space when gym patrons were exercising. FitSkills was modified for 27 participants who were identified as having a ‘complex disability’ [Citation22]. The complexity involved participants having co-morbidities (e.g., significant cardiac, respiratory, renal, or mental health conditions), activity limitations (e.g., high risk of falling) and behavioural challenges (e.g., very limited attention span). Participants with ‘complexity’ often had intellectual disability (n = 23), communication difficulties (n = 15), and/or epilepsy (n = 11). The adaptations made to support these participants included additional mentor training and monitoring and having an experienced physiotherapist attend the first gym session to provide coaching support to the mentor. Mentors of participants with epilepsy were offered additional online training (non-compulsory, 1 h duration). Mentors of participants with complexity did not exercise during the sessions, so they could focus on providing support.

Measures

Outcome measure

Mentors completed the 5-item Disability Discomfort Scale of the Interaction with Disabled Persons Scale [Citation23], at 3-month intervals. The five items were: (i) I feel unsure because I do not know how to behave; (ii) I feel uncomfortable and find it hard to relax; (iii) I cannot help staring at them; (iv) I tend to make contacts only brief and finish them as quickly as possible; (v) I am afraid to look at the person straight in the face. Each of these items was scored using a 6-point Likert type scale (1 = I disagree very much; 6 = I agree very much) with an overall score calculated by summing the scores with lower scores indicating less discomfort interacting with people with disability.

Data analysis

Repeated measures of the outcome measure over seven times were analysed using linear mixed-effects models with random effects to account for correlation within individuals and for clustering within sites [Citation24]. For all models, we used random components, random intercepts to control for heterogeneity between sites and for individuals to account for repeated measures, as well as random slopes to allow the effect of treatment to vary across individuals. Due to skewness, outliers were removed to see if this reduced skewness and to see if the assumption of normal distribution of residuals was met. When removing outliers still resulted in the data being skewed and model diagnostics showed some non-linearity, the data were subjected to a log transformation [Citation25], which resulted in no obvious violations of the model assumptions and so results were reported as per cent change [Citation26]. The stepped wedge design enabled the modelling of the effect of time [Citation27] by including time as a factor moderator which allowed for nonlinear change over the duration of the study. A secondary analysis was conducted for which a time-since-intervention variable was included to see whether the treatment effect was sustained during the rest of the trial [Citation27]. Consistent with intention to treat principles, the linear mixed models used a maximum likelihood estimation to handle missing data under the assumption of missing-at-random [Citation28]. Missingness of data was inspected visually using functions (missing patterns, missing pairs and missing compare) from the finalfit R package [Citation29]. There were no clear patterns or inter-variable dependencies that indicated any systematic missingness of data.

The following demographic variables were added to the model to test if they had an effect on overall disability discomfort scores: age, gender, the course of study enrolled in, year level of study, whether they were a domestic or international student, whether they had previous contact with people with disability or not and whether they were to receive credit for volunteering as part of FitSkills towards their university degree. In addition, separate interaction models compared the effect on discomfort scores before and after the students completed FitSkills of the above demographic characteristics and complexity of disability. We calculated effect sizes using partial eta square (ηp2) that indicate the amount of variance accounted for in the model by moderators using the r2glmm R package [Citation30] and thresholds were interpreted as follows: small effect = 0.01, medium effect = 0.06, and large effect = 0.14 [Citation31].

A correlation analysis investigated if adherence to the program (number of completed sessions at the gym) had any effect on discomfort scores. Mentors were dichotomised as ‘adherent’ if they attended 18 sessions (75%) or more, and ‘non-adherent’ if they attended less than 18 sessions. A sensitivity analysis was performed to study the influence of some extreme discomfort score values found in the data. A robust mixed linear model was fitted using the robustlmm R package [Citation32]. The robust model uses Design Adaptive Scale estimates [Citation32] to produce model estimates where outliers have minimal effect. These estimates were compared to those of the main analysis. The main assumptions for linear mixed-effects models were assessed. Violations of the normal distribution of errors assumption were visually checked using Q-Q plots and model linearity and homoscedasticity of error variance were inspected using residual versus fits plots.

Results

Participants

Of 226 students who agreed to be a mentor, 207 provided data for this study by completing the Disability Discomfort Scale on at least one occasion (). Eighty-four of these 207 students withdrew after baseline testing but before starting FitSkills. The remaining 123 student mentors were matched with participants with a disability and commenced FitSkills. Seven mentors completed FitSkills twice with two different participants with disability, and two mentors completed 6 weeks of training each with one participant (as one mentor was unable to complete all 12 weeks). Mentors were, on average, 21 years (SD 4) and most were female (70%), in the first or second year of their studies (79%) and were local students (95%) ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of student mentors who consented to complete the disability discomfort scale (n = 207).

Effect of FitSkills on level of discomfort when interacting with people with disability

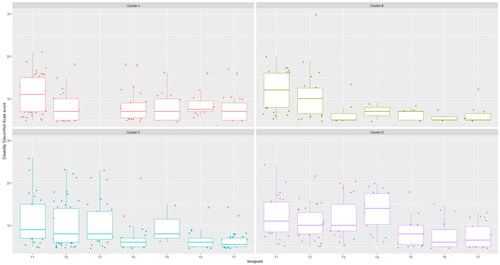

The estimated mean discomfort score at baseline was 10 (out of a possible 30) across all clusters. Across all clusters, discomfort scores decreased by 32.8% (95% CI −36.8 to −28.4, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.33) after exposure to FitSkills (). The subsequent changes in discomfort scores estimated a change of −4.0% (95% CI −5.6 to −2.4, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03), suggesting post-intervention decreases in discomfort scores were sustained.

Figure 3. Box plots with jitter plots (using small random jitter variation) of Time (x-axis) vs. Discomfort Scale scores (y-axis) shown in separate panels for Clusters 1 to 4. In each boxplot, the bottom and top edges indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles respectively. The line within each box indicates the median Discomfort Scales score. The whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range to the most extreme scores. Scores lying beyond the whiskers are outliers (red crosses). Cluster 1 was exposed to the intervention at T1, Cluster 2 at T2, Cluster 3 at T3 and Cluster 4 at T4.

At baseline, mentors who indicated they had previous experience with disability than mentors without previous experience reported significantly lower scores (19.0% lower, 95% CI −28.3 to −8.6, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05). Similarly, mentors who were to receive credit towards their university degree for volunteering as part of FitSkills reported significantly lower scores by 18.9% (95% CI −28.1 to −8.6, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04) than mentors who would not receive credit for their volunteering respectively. Occupational therapy and exercise science students reported significantly lower scores by 23.9% (95% CI −35.1 to −10.9, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02) and 17.2% (95% CI −28.0 to −3.8, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.05) respectively, compared to physiotherapy students at baseline. There was no significant moderating effect on discomfort scores at baseline for age (-0.9%, 95% CI −2.3 to 0.6, p = 0.23, ηp2 = 0.00), year level of study (−4.1%, 95% CI −10.5 to 2.8, p = 0.24, ηp2 = 0.00), or whether a student was a domestic or international student (13.9% reduction for international students, 95% CI −35.2 to 14.3, p = 0.30, ηp2 = 0.00).

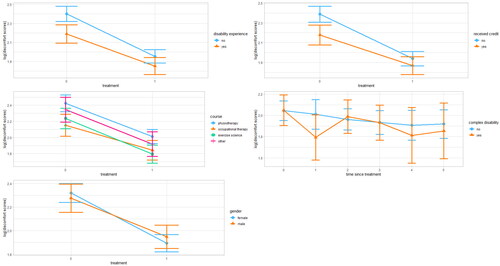

Regarding interaction effects (), students with no reported previous experience with people with disability reported larger reductions in discomfort scores after FitSkills than students who had reported experience with people with disability (-11.6%, 95% CI −27.1 to −2.1, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.02). Also, students who did not receive credit towards their university degree through volunteering for FitSkills, reported larger reductions in discomfort scores than those receiving credits (−15.0%, 95% −30.7 to −1.2, p < 0.03, ηp2 = 0.02). There was no interaction effect for whether a young person with a disability was categorised as having a complex disability or not (-8.1%, 95% CI −19.0 to 4.3, p = 0.19, ηp2 = 0.00), for age (1.1%, 95% CI −0.4 to 2.5, p = 0.14, ηp2 = 0.00), course of study enrolled in (10.8% and 2.9%, 95% CI −6.6 to 31.6 and −17.1 to 13.8, p = 0.24 and p = 0.72, ηp2 = 0.00 and ηp2 = 0.00 for occupational therapy students and exercise science students respectively), year level of study (0.7%, 95% CI −6.4 to 8.4, p = 0.85, ηp2 = 0.00) or whether a student was a domestic or international student (15.6% for international students, 95% CI −18.3 to 63.7, p = 0.41, ηp2 = 0.00). There was no association between adherence to FitSkills and changes in discomfort scores (r = 0.12, p = 0.27). Sensitivity analysis using a linear mixed model to determine the influence of outliers found the magnitude and significance of the treatment effect remained unchanged (-34.4%, 95% CI −37.5 to −31.1, p < 0.001). Visual inspection of residual plots did not reveal any model or error assumption violations.

Figure 4. Interaction plots between some considered moderators and their effects on predicted values of the outcome variable (log of discomfort scores) when passing from control (treatment/time since treatment = 0) to immediately after treatment (time since treatment = 1) and subsequent 3-month interval follow-ups. The bars on either extreme are 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Our main findings were: (1) FitSkills fostered lower levels of discomfort interacting with young people with disability among mentors from across a range of health disciplines; (2) these changes were sustained for up to 15 months following completion of FitSkills; and (3) mentors with no reported previous experience of people with disability and those not receiving university credit for completing FitSkills had a larger reduction in discomfort scores than mentors with disability experience or those receiving university credit for volunteering.

That mentors reported feeling less discomfort interacting with people with disability after completing a short community-based volunteer experience is consistent with previous studies involving physiotherapy students [Citation1,Citation11–14]. Consistent with contact theory, the results [Citation9] confirm attitudes to disability are amenable to change among health students when interactions include relationships of equal status, working towards a common goal, the absence of competition and acknowledgement of the same social norms [Citation10]. It confirms the findings of a systematic review that disability training involving people with disabilities, community placements and interactive sessions are effective in improving knowledge, confidence, competency, and self-efficacy among health workers [Citation33]. The current study builds on previous literature by showing the positive and sustained effects of volunteering as a mentor in a community exercise program for students from across a range of health disciplines.

Positive attitudes toward people with disability among student health and exercise professionals are important to facilitate better access to quality healthcare for people with disability. Patient encounters in health settings are likely to be more positive when student health professionals feel comfortable interacting with people with disability. Similarly, people with disability may be more likely to receive pertinent health information about the physical activity when health professionals appreciate their physical capabilities. Practical experiences, such as FitSkills, can fill a gap in university curricula about how to relate to people with disability [Citation34], by providing a richer understanding of what it means to live with a disability, challenging negative assumptions about disability directly and encouraging thinking about disability as a social construct rather than as a medical problem.

An important new finding was that a reduction in the discomfort experienced by student health and exercise professionals when interacting with people with disability was sustained for up to 15 months. As these data were collected as part of a study with a robust trial design, this increases the certainty changes were due to the intervention rather than other variables such as student maturation or exposure to university curricula. The longer-term retention of positive changes towards those with disability over 15 months in the current study supports the utility of this type of short-term community experience for entry-level health students, even with variable levels of program adherence.

At baseline, students with previous experience of disability or who were to receive university credit for completing FitSkills had lower discomfort scores yet mentors who reported no previous experience of disability and those not receiving university credit for completing FitSkills had a larger reduction in discomfort scores than students with disability experience or those receiving university credit for volunteering. Those with disability experience or those who sought out a university-credited experience focused on disability initially may have felt more comfortable interacting with people with disability. It is possible those without this experience had greater scope to reduce discomfort after contact with people with disability.

It was hypothesised that students’ attitudes are influenced by the functional level of the young person with a disability and that spending time with someone with a ‘mild’ disability might produce a more positive change in attitude [Citation1]. Describing the severity of the disability of the young people who participated in FitSkills is difficult because of differences in the way severity is measured across participants with such varied diagnoses. The description of a participant’s disability as ‘complex’ was used as a proxy for more severe disability, and we found disability complexity had no effect on mentor discomfort scores. In fact, the analysis approached significance in the opposite direction i.e., students working with young people with more complex disabilities tended to have greater reductions in discomfort scores after FitSkills. We also found age, year level and program adherence had no association with changes in discomfort scores.

The strengths of this study were: (1) its robust study design, incorporating control data to allow for direct comparison of attitudes before and after exposed FitSkills, and longitudinal post-intervention data over 15 months; (2) its use of rigorous and sophisticated analytical techniques, including linear mixed effects models, the analysis of potential moderator variables and sensitivity analysis of outliers; and (3) an extensive database from 207 mentors recruited from 11 disciplines and across three universities. This study also had limitations. As it was not possible to blind mentors to the intervention, their self-report outcomes were not blinded. Self-reported outcomes may not necessarily reflect mentors’ behaviour and were not corroborated with other data such as observational data. Another limitation is that although the study outcome (discomfort with interacting with people with disability) was measured using a 5- item questionnaire with sound measurement properties (confirmed by factor and Rasch analysis), this is only one dimension of attitudes to disability. Qualitative data based on semi-structured interviews with approximately 90 mentors after their participation has been collected as part of the larger FitSkills trial. These data will be analysed to explore other dimensions of attitudes such as thoughts and emotions. That analysis will be published separately due to the extent of the available data.

Conclusions

Entry-level health students reported more positive attitudes towards interactions with people with a disability immediately after completing a 12-week volunteer community-based program called FitSkills. Positive changes in attitudes were retained up to 15 months after the experience. These findings support the value of short-term volunteer community experiences for health students to promote and sustain more positive attitudes towards people with disability among future health and exercise professionals.

Ethical Statement

Ethics approval was obtained from La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee (HEC17-012), Australian Catholic University (2017-63 R), Deakin University (2017-206) and the Victorian Department of Education and Training (2018_003616).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the mentors and participants with a disability who so generously volunteered their time to FitSkills.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Shields N, Stukas AA, Buhlert-Smith K, et al. Changing student health professionals’ attitudes toward disability: a longitudinal study. Physiother Canada. 2021;73(2):180–187.

- Alborz A, McNally R, Glendinning C. Access to health care for people with learning disabilities in the UK: mapping the issues and reviewing the evidence. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(3):173–182.

- Brown M, MacArthur J, McKechanie A, et al. Equality and access to general health care for people with learning disabilities: reality or rhetoric? J Res Nurs. 2010;15(4):351–361.

- Matin BK, Williamson HJ, Karyani AK, et al. Barriers in access to healthcare for women with disabilities: a systematic review in qualitative studies. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):1–23.

- Chardavoyne PC, Henry AM, Forté KS. Understanding medical students’ attitudes towards and experiences with persons with disabilities and disability education. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(2):101267.

- Ee J, Stenfert Kroese B, Rose J. A systematic review of the knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of health and social care professionals towards people with learning disabilities and mental health problems. Br J Learn Disabil. 2021; 50(4):467–483.

- Au KW, Man DWK. Attitudes toward people with disabilities: a comparison between health care professionals and students. Int J Rehabil Res. 2006;29(2):155–160.

- Stachura K, Garven F. A national survey of occupational therapy students’ and physiotherapy students’ attitudes to disabled people. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(5):442–449.

- Gething L. Attitudes toward people with disabilities of physiotherapists and members of the general population. Aust J Physiother. 1993;39(4):291–296.

- Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison Wesley Publishing Company Inc; 1954.

- Shields N, Bruder A, Taylor NF, et al. Getting fit for practice: an innovative paediatric clinical placement provided physiotherapy students opportunities for skill development. Physiotherapy. 2013;99(2):159–164.

- Shields N, Taylor NF. Contact with young adults with disability led to a positive change in attitudes toward disability among physiotherapy students. Physiother Canada. 2014;66(3):298–305.

- Shields N, Taylor NF. Physiotherapy students’ self-reported assessment of professional behaviours and skills while working with young people with disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(21):1834–1839.

- Shields N, Bruder A, Taylor N, et al. Influencing physiotherapy student attitudes toward exercise for adolescents with down syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(4):360–366.

- Shields N, Willis C, Imms C, et al. FitSkills: protocol for a stepped wedge cluster randomised trial of a community-based exercise programme to increase participation among young people with disability. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e037153.

- Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, et al. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ. 2015;350(feb06 1):h391–h391.

- Shields N, Willis C, Imms C, et al. Feasibility of scaling-up a community-based exercise program for young people with disability. Disabil Rehabil . 2022; 44(9):1669–1681

- Shields N, van den Bos R, Buhlert-Smith K, et al. A community-based exercise program to increase participation in physical activities among youth with disability: a feasibility study. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(10):1152–1159.

- Mahy J, Shields N, Taylor NF, et al. Identifying facilitators and barriers to physical activity for adults with down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2010;54(9):795–805.

- Shields N, Taylor NF. A student-led progressive resistance training program increases lower limb muscle strength in adolescents with down syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. J Physiother. 2010;56(3):187–193.

- Shields N, Taylor NF, Wee E, et al. A community-based strength training programme increases muscle strength and physical activity in young people with down syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(12):4385–4394.

- Ritzema AM, Lach LM, Rosenbaum P, et al. About my child: measuring ‘complexity’in neurodisability. Evidence of reliability and validity. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(3):402–409.

- Iacono T, Tracy J, Keating J, et al. The interaction with disabled persons scale: revisiting its internal consistency and factor structure, and examining item-level properties. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30(6):1490–1501.

- Nickless A, Voysey M, Geddes J, et al. Mixed effects approach to the analysis of the stepped wedge cluster randomised trial—investigating the confounding effect of time through simulation. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0208876.

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics title: using multivariate statistics Vol. 5. Boston, MA; Pearson; 2019.

- Yang J. Interpreting coefficients in regression with log-transformed variables. Cornell Univ Ithaca, NY, USA; 2012.

- Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):1–9.

- Groenwold RHH, Moons KGM, Vandenbroucke JP. Randomized trials with missing outcome data: how to analyze and what to report. CMAJ. 2014;186(15):1153–1157.

- Harrison E, Drake T, Ots R, et al. Package ‘finalfit. Retrieved Febr. 2020;29: 2020.

- Jaeger B. Package ‘r2glmm.’ R Found Stat Comput Vienna available CRAN R-project org/package = R2glmm; 2017.

- Norouzian R, Plonsky L. Eta-and partial eta-squared in L2 research: a cautionary review and guide to more appropriate usage. Second Lang Res. 2018;34(2):257–271.

- Koller M. {robustlmm}: an {R} package for robust estimation of linear mixed-effects models. J Stat Softw. 2016;75(6):1–24.

- Rotenberg S, Gatta DR, Wahedi A, et al. Disability training for health workers: a global evidence synthesis. Disabil Health J. 2022;15(2):101260.

- Shakespeare T, Iezzoni LI, Groce NE. Disability and the training of health professionals. Lancet. 2009;374(9704):1815–1816.