Abstract

Purpose

Telehealth may help meet the growing demand for orthotic/prosthetic services. Despite the resurgence of telehealth due to COVID-19, there is limited evidence to inform policy and funding decisions, nor guide practitioners.

Methods

Participants were adult orthosis/prosthesis users or parents/guardians of child orthosis/prosthesis users. Participants were convenience sampled following an orthotic/prosthetic telehealth service. An online survey included: demographics, Telehealth Usability Questionnaire, and the Orthotic Prosthetic Users Survey – Client Satisfaction with Services. A subsample of participants took part in a semi-structured interview.

Results

Most participants were tertiary educated, middle-aged, female, and lived in metropolitan or regional centres. Most telehealth services were for routine reviews. Most participants chose to use telehealth given the distance to the orthotic/prosthetic service, irrespective of whether they lived in metropolitan cities or regional areas. Participants were highly satisfied with the telehealth mode and the clinical service they received via telehealth.

Conclusions

While orthosis/prosthesis users were highly satisfied with the clinical service received, and the telehealth mode, technical issues affected reliability and detracted from the user experience. Interviews highlighted the importance of high-quality interpersonal communication, agency and control over the decision to use telehealth, and a degree of health literacy from a lived experience of using an orthosis/prosthesis.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Orthotic/prosthetic users were highly satisfied with the clinical services they received via telehealth.

Satisfaction was linked to having agency and control over the decision to use telehealth, a clear understanding of the purpose of the appointment and any requirements, and a degree of health literacy that facilitated communication.

Orthosis/prosthesis users and practitioners can make informed choices about using telehealth which suggests that many telehealth guidelines maybe unnecessarily risk averse.

Telehealth is a useful tool to overcome barriers to accessing orthotic/prosthetic care for people in both metropolitan and regional areas.

There are opportunities to support clinicians with targeted telehealth education to improve practice and reduce barriers to high-quality telehealth services.

Introduction

The number of people requiring assistive technology – including orthoses and prostheses – is expected to double by 2030 given a larger and ageing population, and increased prevalence of non-communicable disease such as diabetes that are common among orthosis/prosthesis users [Citation1]. In Australia, like many parts of the world, it will be difficult to meet this growing demand given the low number of practitioners (i.e., orthotist/prosthetists) per head of population, and the geographic clustering of clinical service providers in large regional and metropolitan centres [Citation2,Citation3]. Innovative models of service delivery – such as telehealth – will be required to improve access to orthotic/prosthetic care; particularly for those living in regional, rural, and remote areas, where the greatest health inequalities exist [Citation4,Citation5].

The World Health Organization defines telehealth as “the delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.”[Citation6] (p. 9) Telehealth has been used to varying extents by many health professions including: general practitioners [Citation7,Citation8], psychology [Citation9,Citation10], physiotherapy [Citation11–13], audiology [Citation14–16], speech pathology [Citation16–18] and dietetics [Citation19,Citation20]. Research suggests that there are many benefits to telehealth including: improved access to healthcare [Citation21–24], improved quality of services and clinical outcomes [Citation21,Citation23,Citation25], decreased cost [Citation21–23], improved convenience [Citation22–24], as well as high-levels of consumer satisfaction [Citation22–24,Citation26].

Despite these benefits, there has been limited adoption of telehealth for orthotic/prosthetic services given a wide range of barriers including: structural barriers (e.g., lack of reimbursement for services provided using telehealth, initial cost outlay) [Citation27–29], patient-related barriers (e.g., age, level of education, computer literacy) [Citation24,Citation28,Citation30] and practitioner-related barriers (e.g., resistance to change, poor technology self-sufficiency, perceptions of depersonalised care, perceptions that clinical services have to be “hands-on”) [Citation27–29].

Since early 2020, telehealth has been more widely utilised in Australia given the impact of COVID-19 [Citation31,Citation32]. In early 2020 the Victorian state government imposed a range of restrictions to minimise community transmission of COVID-19 including physical distancing and stay-at-home orders. Given the need to minimise the burden on the healthcare system during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was important that critical healthcare – including orthotic/prosthetic services – could be provided safely during extended periods of lock down and as such, a range of policy changes were introduced to remove some of the structural barriers to the adoption of telehealth. For example, funding bodies began to reimburse for allied health services provided using telehealth [Citation33], which lead to a rapid uptake of telehealth across Australia [Citation31,Citation32,Citation34]; including orthotic/prosthetic clinical services.

Despite the rapid uptake of telehealth for orthotic/prosthetic clinical services in Australia, little is known about the demographics of users, the types of orthotic/prosthetic services delivered using telehealth, nor the user experience of, and satisfaction with, the clinical service received. A contemporary understanding of orthotic/prosthetic telehealth services is required to inform important policy and investment decisions, as well as support the development of clinical standards that help ensure safe and effective orthotic/prosthetic services using telehealth. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe:

the population receiving orthotic/prosthetic services using telehealth in Australia

the orthotic/prosthetic services being provided using telehealth in Australia

the consumer experiences and satisfaction with both the telehealth mode as well as the clinical service received.

Materials and methods

This sequential explanatory study [Citation35] involved two phases. In the first phase, a quantitative approach was used to: described the population receiving orthotic/prosthetic services in Australia using telehealth, the type of orthotic/prosthetic services being provided, and the user experience and satisfaction with both the telehealth mode as well as the clinical service received. In the second phase, a qualitative approach was used to learn more about the detail of the consumer experience and satisfaction with the telehealth mode and the clinical service received. In this way, the richness of the qualitative data were important to help interpret and clarify of the results from the quantitative data analysis [Citation35].

Ethics approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committees at La Trobe University (HEC#20327) and the University of South Australia (HREC#203413).

Phase I: quantitative

Participants

Participants were adult orthosis/prosthesis users ≥18 years of age (adult subgroup) or parent/guardian of children orthotic/prosthesis <18 years of age (parent/guardian subgroup). Participants in the adult subgroup were eligible if they had received an orthotic/prosthetic service using telehealth. Participants in the parent/guardian subgroup were eligible if their child had received an orthotic/prosthetic service using telehealth. There were no restrictions based on the type (e.g., initial assessment) or purpose (e.g., a repair) of the orthotic/prosthetic clinical service, nor the telehealth mode.

Using convenience sampling (where participants were selected based on ease of access, availability, and willingness to participate), participants were recruited from the providers of orthotic/prosthetic clinical services across Australia (i.e., clinical service providers) who had partnered in this research. Clinical service providers were invited to partner in this research through the Australian Orthotic Prosthetic Association (AOPA); the peak professional body representing orthotists/prosthetists in Australia. AOPA sent expressions of interest to the AOPA member database via email and promoted the opportunity through AOPA’s social media, the AOPA website, and personal invitations to AOPA Clinical Corporate Partners [Citation36]. As such, the expression of interest would have reached approximately 630 individual AOPA members who worked at approximately 150 clinical services providers, including both private and public facilities, in every Australian state and territory in both August and November 2020.

Clinical service providers who expressed interest received detailed instructions regarding what their participation in the study would involve. Those interested in partnering in this research returned a signed agreement and confirmed their willingness to partner in either one or two, 12-week recruitment periods.

Upon receipt of the signed agreement, a suite of onboarding documents were provided to the clinical service provider. These documents: summarised the purpose of the project, stated the inclusion criteria, set expectations about the communication with prospective participants including the standardised text for emails, text messages, or communications sent using proprietary client management software (e.g., Cliniko) as well as hyperlinks to the online survey.

Data collection

Prospective participants, who met the inclusion criteria, were made aware of the study by the treating practitioner at the conclusion of their orthotic/prosthetic telehealth service. A standardised script was used to introduce the study (Supplementary Appendix 1). Within seven days following the orthotic/prosthetic telehealth service, prospective participants received a standardised email or text message from the clinical service provider that included a link to the online survey. A single reminder email or text message was sent one-week after the initial invitation.

Prospective participants were then able to follow the link to the online survey landing page where they could read the Participant Information and Consent form, as well as complete the online survey. Consent was implied in completing the online survey.

Survey instruments

The online survey was administered using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, USA). The survey instrument comprised of three subsections:

Participant demographics

This subsection of the survey included a comprehensive range of questions including, as illustrative examples: contact details, date of birth, sex, education level, postcode, the primary reason for requiring orthotic/prosthetic care received, and comorbid health conditions.

Telehealth usability questionnaire (TUQ)

This 21-item survey of telehealth usability included five subscales: Usefulness, Ease of Use, Effectiveness, Reliability, and Satisfaction [Citation37]. Each subscale included between three and six questions that quantified aspects of telehealth usability in accord with precise subscale definitions (e.g., reliability was defined by …how easily the user could recover from an error and how the system provided guidance to the user in the event of error [Citation37] (p. 5). Participants responded to each question using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree with higher scores indicating stronger agreement. The TUQ has been shown to have good content validity and reliability (Cronbach’s α > 0.8) [Citation37].

Orthotic prosthetic users survey – client satisfaction with services module (OPUS-CSS)

This 10-item subscale of the OPUS quantifies user satisfaction with orthotic/prosthetic clinical service and includes questions focused on courtesy and respect of staff, or involvement in decision-making, as illustrative examples. Participants responded to each question on a five-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction [Citation38]. The OPUS-CSS has adequate test-retest reliability and has been validated for people of all ages living with either uni- or bi-lateral orthotic/prosthetic needs [Citation38,Citation39].

Minor modifications were made to the three subsections of the survey to create bespoke versions suitable for either the adult or parent/guardian subgroups with the intent to maintain the psychometric integrity of the original instruments. For example, the following question from the OPUS-CSS was suitable for the adult subgroup (i.e., I waited a reasonable amount of time to be seen) but required minor adaptations for the parent/guardian subgroup (i.e., I waited a reasonable amount of time for my child to be seen). Both the adult and the parent/guardian versions of the survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete.

Clinical service audit

At the end of each 12-week data collection period, clinical service providers were given an audit spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel, Redmond, WA, USA) that contained the names of the participants from their service who had completed the online survey. Clinical service providers completed the following details about the telehealth service from the participants’ health records: telehealth platform/mode (e.g., telephone, online platforms), consult duration (e.g., 10–20 min), type of consult (e.g., routine review), post-consultation activities (e.g., scheduled routine review) and funding for consultation (e.g., self-funded). Clinical service providers were asked to return their completed audit data within 10 days.

Data reduction and analysis

Raw data from the online survey were exported to Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA) for reduction and analysis. Demographic data were summarised using descriptive statistics appropriate to the data type for each of the participant subgroups and the cohort. Age was calculated from each participant’s date of birth and categorised into 10-year age brackets. Details about each participant’s place of residence (i.e., state/territory, remoteness category) were calculated by entering their postcode into an online Australian Bureau of Statistics map [Citation40]. For the TUQ, Likert scale responses were averaged within each subscale for each participant [Citation37]. Mean subscale scores and standard deviations were subsequently calculated for each of the adult and parent/guardian subgroups, as well as the cohort. For the OPUS-CSS, Likert scale responses were summed for each participant and raw scores transformed to a population-based T-score [Citation38]. Mean T-scores and standard deviations were subsequently calculated for each of the adult and parent/guardian subgroups, as well as the cohort. Data from the clinical service audit were summarised using descriptive statistics appropriate to the data type for each of the participant subgroups and the cohort. Written responses describing the activities performing during and after the clinical service were thematically analysed to reconcile the way different clinicians described the same activities (e.g., review socket fit, evaluate the fit of the prosthetic socket) and thereby synthesise these data.

Phase II: qualitative

Participants

All participants who completed the online survey (Phase I) received an email invitation to take part in a one-on-one semi-structured interview (Phase II) given the intent to obtain a richer understanding of the participant experience. A single reminder email was sent one-week after the initial invitation.

Data collection

Participants who accepted the invitation to take part in a semi-structured interview were provided with a mutually agreeable interview date and time. Participants elected to undertake the interview by telephone or video conference.

Interviews commenced with participants describing the purpose of the study and reaffirming their consent to participate. Interviews proceeded in accord with the semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary Appendix 2). The interview guide was developed in accord with best-practice guidelines [Citation41,Citation42] that included drafting and refining the interview questions to ensure they were not leading, and included nested questions to an open-up conversation about the participants’ experience and satisfaction with telehealth in keeping with the study aims. Similarly, the interview guide was designed to cue the interviewer to amend the language to ensure the questions were appropriate for each participant subgroups. For example, “Can you tell me why you/your child [select one] had an appointment with the orthotist/prosthetist?” The interview guide was piloted and subsequently refined after testing with potential participants. Based on this testing, interviews took approximately 30–45 minutes to complete.

Interviews were conducted by a female research assistant (KB) with undergraduate training in psychology and significant experience as a crisis counsellor. While the research assistant had significant interview experience, additional training was provided prior to the investigation to learn more about prosthetic services including several visits to partner clinical service providers. The research assistant (KB) completed a reflective diary immediately following each interview to become more aware of feelings, assumptions, personal biases, and decisions throughout the study [Citation43].

Data analysis

Following the interviews, data were analysed in accord with the process described by Castleberry and Nolen [Citation44] and incorporated a range of strategies that engender confidence in the rigour and trustworthiness of the analysis. In summary, audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by a third-party service (Rev, San Francisco, USA). All transcripts were independently read and analysed by the research assistant and one other investigator. Transcripts were initially read in their entirety to gain an understanding of the conversation. Using an inductive approach, line-by-line coding was undertaken using NVivo 11 (QSR International, Chadstone, Australia). Similar codes were grouped to derive themes and sub-themes characterising the participants’ experience and satisfaction with telehealth. Independent coding was then discussed, and differing interpretations were reconciled by discussion until consensus with reference to the original transcription. The clinical service audit data provided a means to confirm details about the type of consultation and what occurred during the consultation.

A single-page document containing a summary of themes and illustrative first-person quotes was distributed to each participant as part of the process of member-checking (Supplementary Appendix 3). As necessary, questions were raised with participants to clarify any queries that arose during the analysis. Participants had the opportunity to provide feedback on the summary via email or telephone. Participants were told that the summary would be considered accurate if no feedback was received within 10 days. Based on the participant feedback, amendments were made to ensure the participants’ experience was accurately reflected in the summary.

Following the process of member-checking, investigators (KB and MD) independently identified common themes and subthemes using a first principles approach. Differences in the interpretation were discussed until consensus. Each theme and subtheme were then drafted and included illustrative first-person quotes (KB and MD). This interpretation was provided to all members of the research team ahead of a half-day discussion to engender confidence in the trustworthiness of the interpretation. An investigator not associated with synthesising the data or drafting the results narrative (ER) then read each interview in its entirety to ensure that the themes, subthemes, narrative, and first-person quotes were a truthful reflection of the participants’ experience. In presenting the illustrative first-person quotes, we have been deliberate in using pseudonyms and avoiding the inclusion of individual demographic data about the participants to ensure their anonymity.

Results

Phase I: quantitative

Participant characteristics

Between 19th November 2020 and 10th September 2021, 17 surveys were completed. Following data screening, two survey responses were excluded because participants had completed the survey twice. As such, data were available for 15 participants including 12 participants in the adult subgroup and 3 participants in the parent/guardian subgroup.

Most participants were female (60%) adults between 30 and 59 years of age (59%) who lived in major cities (40%) or inner-regional centres (47%, ). There were some noteworthy differences between subgroups. Participants in the parent/guardian subgroup were younger (32.3 ± 2.1 years) than those in the adult subgroup (56.2 ± 15.3 years, ). The parent/guardian subgroup included a larger proportion of people with multiple prior telehealth experiences compared to the adult subgroup (). In comparison to the parent/guardian subgroup, the adult subgroup included people who were retired or on some form of disability support pension ().

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Clinical services received

Participants were recruited from six orthotic/prosthetic service providers who partnered with this investigation. All six were private orthotic/prosthetic clinical service providers, reflecting a cross-section of Australian states including: Western Australia, Victoria, and New South Wales ().

Table 2. Clinical service characteristics.

While details of the clinical services received by participants have been reported in , there are some noteworthy observations. Most telehealth services were for routine reviews of an existing orthosis/prosthesis (). The handful of initial assessments were to establish treatment goals or obtain information necessary to complete a funding application. The purpose of the appointment seemed unrelated to the choice of telehealth mode, nor the duration of the service encounter. Most participants chose to use telehealth given the distance to the orthotic/prosthetic service (); acknowledging that the proportion of people living in major cities and regional areas were similar ().

Telehealth usability

There was a high degree of satisfaction with the telehealth mode among both the adult (5.8 ± 0.7) and the parent/guardian (5.6 ± 1.5) subgroup. Both subgroups found telehealth similarly easy to use, effective, and useful. In both subgroups, issues with reliability detracted from satisfaction with the telehealth system ().

Table 3. Telehealth usability questionnaire scores.

Satisfaction with orthotic/prosthetic services

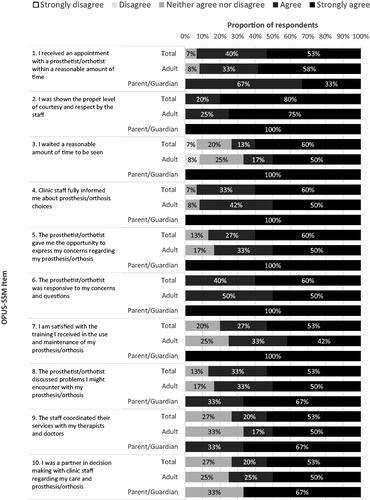

Participants were very satisfied with the orthotic/prosthetic services they received (T-score = 74.6 ± 23.3). All participants strongly agreed or agreed that: orthotists/prosthetists were responsive to participant’s concerns and questions (, question 6), and participants felt they were shown the proper level of courtesy and respect by staff (, question 2). Similarly, most participants felt they were fully informed about their prosthesis/orthosis choices (, question 4), and waited a reasonable about of time to be seen (, question 3). While satisfaction with orthotic/prosthetic services was very high in both the adult (T-score = 71.2 ± 24.7) and parent/guardian subgroups (T-score = 87.6 ± 10.7), satisfaction was more varied in the adult subgroup.

Figure 1. Results of Orthotic Prosthetic User Survey – Client Satisfaction with Services (OPUS-CSS). Proportion of responses to the OPUS-CSS items stratified by subgroup. N Total= 15, n Adult = 12, n Parent/guardian = 3.

Phase II: qualitative

Participant characteristics

Of the 15 participants who completed the survey, five (5) agreed to a follow-up interview including four participants from the adult subgroup, and one participant from the parent/guardian subgroup. Demographic details of those who were interviewed have been reported in .

Clinical services received

Most people who participated in the interview used telehealth for either routine or unscheduled reviews to resolve problems with the orthosis/prosthesis (). Most of these appointments were between 10 and 30 min and occurred by telephone ().

Interview themes

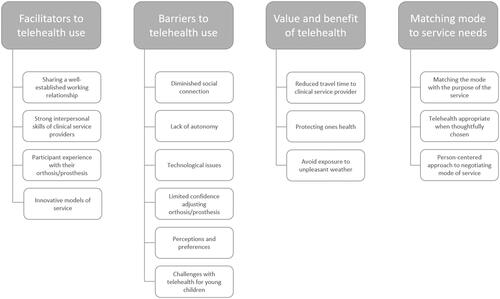

Four themes were identified from the interviews: facilitators to telehealth use, barriers to telehealth use, value and benefit of telehealth, and matching mode to service needs ().

Figure 2. Summary of qualitative themes.

Facilitators of telehealth use

Participants identified several factors that enhanced their experience and satisfaction using telehealth including a well-established working relationship with the practitioner, the practitioner possessing strong interpersonal skills, participant experience with their orthosis/prosthesis, and innovative models of service.

Well-established working relationship: Many participants described that a well-established working relationship with their practitioner was key to their satisfaction with telehealth. This was often attributed to the practitioner’s familiarity with the consumer’s orthotic/prosthetic history and the strong personal relationship.

“It’s like talking to a friend, because I’m used to communicating with her, we’ve been able to discuss what we need using telehealth without any issues.” – Matilda

“I’ve got a very good relationship with [the prosthetist], she’s been looking after me all this time, she’s a lovely, friendly person” … “So that relationship’s already there, and I’m used to communicating with her via text and phone” … “Because she is already aware of my foot, it’s easy to explain things.” – Gale

Some of the participants who shared a well-established working relationship with their practitioner hypothesised that it would be challenging for them to build that relationship using telehealth exclusively.

“I think I’m lucky because we already had an established relationship, so it would be different if we had to build that over telehealth… it could be done, but it would take a lot of effort” … “[My prosthetist and I] just continued that relationship of trust, and gratitude on my part [When switching to telehealth].” - Matilda

Interpersonal skills: Participants unanimously described the importance that the practitioner possessed strong interpersonal skills such as effective communication, attentiveness, reassurance, and the ability to convey empathy. These skills seemed to be very highly valued and positively impacted the telehealth experience.

“She introduced herself to my daughter first, didn’t really even acknowledge me which is like, a great sign. It was quite clear who she was there for… I get the feeling that anyone with a lower amount of social skills would not have been able to pull it off. I think just her communication skills came through really well. She was very clear, she was very softly spoken, she was very friendly. Big smile. All the things that you’d want to see in real life anyway. It made me feel comfortable and my daughter [child O&P user] seemed happy. She’s pretty stubborn [child O&P user], if she doesn’t like something or someone, she’ll tell you straight away. But she [child O&P user] stuck it out there for at least half an hour, so that’s probably a good sign.” – John, parent

“He [orthotist] rang me several weeks later just to make sure that everything was okay. So I think it depends on your specialist as to how well [telehealth] pans out. I didn’t have to ear bash him to get his attention.”… “I probably would’ve done that [what the orthotist advised] anyway. I mean, I just got reassurance that what I was doing was reasonable” – Jane

Where there was not yet a well-established working relationship between the consumer and practitioner, high-level interpersonal skills seemed particularly important for a satisfactory telehealth experience.

“I guess, overall [the experience using telehealth was] positive. But only because she reassured me that she was happy with what she got. Without that, my doubts probably would have felt a little stronger and I would have thought “Oh, maybe that [telehealth consultation] didn’t go so well” –John, parent

Participant experience with their orthosis/prosthesis: Participants with a significant lived experience of orthosis/prosthesis use seems to have a high degree of health literacy that facilitated communication about the problem and what needed to be done. These participants seemed to have a more positive telehealth experience given they could better communicate their needs and make informed decisions about when telehealth was appropriate.

“I’m not a prosthetist, but I know what they do, and I was in hospital for [several months]” … “I’m smart enough to know when I need to see someone” … “I’ve had a tough time with my disease, and I’ve always pushed. I will ring all the time if I need to.” – Alexander

“I can always get my message across. We don’t have any trouble communicating, I can sort of explain what’s going on or what I’m needing, then she’s able to reciprocate totally with suggestions” – Gale

Innovative models of service: There was an isolated example of a very innovative practice that greatly enhanced a participant’s experience of telehealth and challenged parochial barriers to providing high-quality care. At the time these data were collected, severe travel restrictions were imposed on residents in the state of Victoria (Australia) to minimise the community spread of COVID-19 (State-mandated stay-at-home orders). This prevented people living in regional/remote areas travelling to the city (i.e., Melbourne) for their usual orthotic/prosthetic care. In this example, a participant living in regional Victoria sought a telehealth appointment with their Melbourne-based clinical service provider given a problem with the suspension of their transfemoral prosthesis. It was identified that the valve in the prosthetic socket needed to be replaced. The Melbourne-based service provider arranged for an orthotist/prosthetist living in a regional centre to undertake the repair.

“Well, that was when the Ring of Steel was up [a colloquialism for police-enforced road closures that cordoned off Melbourne from the rest of the state of Victoria] and I was in distress because I knew I couldn’t [go to Melbourne]. So, [my prosthetist] knew the prosthetist here [in the regional centre], and so he sent the valve up to him, and the prosthetic dude here, fitted it for me, so… I mean and that was through Telehealth, I suppose, he organised it so that I stayed safe here in [regional centre].” - Alexander

Barriers to telehealth use

Participants identified a wide variety of barriers to the use of telehealth including: diminished social connection, lack of autonomy, technological issues, limited confidence with adjusting the orthosis/prosthesis, perceptions and preferences, and challenges working with young children.

Diminished social connection: Many participants underscored a sense of diminished social connection with their practitioner compared with in-person clinical services, which detracted from their satisfaction with the experience:

“It’s not the same” … “I suppose I’d be a bit disappointed if it was all over telehealth – I mean, it’s professional, but I’d nearly call him my mate.” – Alexander

“I’m sure there were times during COVID where I had telehealth, but I really just wanted to see them… But that could be from a combination of factors, like the lack of social connection” … “You get a bit hungry for your face-to-face after a little while.” – Matilda

“I think those micro moments of connection are probably not as enhanced through video compared to face-to-face. We’re not getting all the bodily cues that we usually get and missing all of that interpretation”. – Matilda

Lack of autonomy: Participants felt strongly that the lack of agency and autonomy over their telehealth service detracted from the experience; emphasising how important it was to have a choice and control over their appointments.

“I didn’t have control because by the time they rang, I needed to be heading out the door – I didn’t have time to explain my issue to him. It was extremely negative.” – Gale

“I think the ability for people to have choice in their healthcare needs is really critical.” – Matilda

Technological issues: Although all participants reported feeling confident with using technology, there were some notable technological barriers.

“I know I’m going to be speaking with you, so I need to get organised. I put the phone in the bathtub [where there’s reception] and I’m here a couple of minutes beforehand” … “if I’m on hold, I can’t just walk around here with the phone and wait for them to answer in case the signal drops out”. …. “And also, it [the phone] can just suddenly drop out and it goes onto searching for five minutes, and I can’t use it for five minutes” – Gale

In one instance, the parent/guardian was asked to show their child walking via video conferencing, and described the challenge using a laptop for this purpose:

“It was just a little bit clunky. Picking up a laptop, trying to turn it around and make sure she’s [prosthetist] got a good angle of the camera and that she could see what she needs. In hindsight I probably should have used a phone, but I definitely left the meeting thinking, “Oh geeze, surely she didn”t get what she needed there. That was pretty ordinary." – John, parent

“I can talk to the prosthetist until the cows come home [colloquialism meaning indefinitely or forever] … but not much is going to happen because I can’t fix the damn thing [the prosthesis]” … “They [the prosthetist] can tell me a million things on how to fix it [the prosthesis] and I’m probably not going to be able to do it.” – Alexander

“When I get instructions to tighten this screw or loosen this one, my confidence isn’t as great as my prosthetist” – Matilda

Participant perceptions and preferences: Some participants were concerned about the utility of the telehealth mode, and it seemed to be a barrier to their experience and satisfaction.

“She [the prosthetist] might miss something because she can’t see properly… You can’t quite get that same level of detail over video. For example, walking gait or skin breakdown”-Matilda

“You can do a lot of multitasking and not really focus on that conversation. You might have the conversation going, but you might have five other tabs open or whatever it might be. So, there’s a distraction issue there on both ends potentially” – Matilda

In one instance, it was apparent that a participant’s expectations were very different from the practitioner, which undermined confidence in the telehealth service. In this example, the practitioner undertook an initial assessment for the purpose of developing a funding application. The parent/guardian was dissatisfied given their expectation that the practitioner would make careful observations and measurements of their child’s limbs; the sorts of detailed measurements needed to fabricate the orthosis, not necessarily to develop a prescription and funding application.

“If someone [clinician] was making a custom set of orthotics for you, and you’d never met them, they’ve never actually seen your feet or your ankles, it’s a big ask I reckon. But they’re professionals, so maybe it’s possible. I guess” … “She [clinician] said she got what she needed, so I guess I should just shut up and be happy.” But yeah, a little bit mixed in that my feelings and satisfaction didn’t seem to match up with what the practitioners. She [clinician] seemed happy, I felt couldn’t have gone that well.” – John, parent

Some participants felt quite strongly that telehealth was unlikely to work and focused on a narrow range of clinical services to substantiate their view. These opinions were often counter to the thoughtful and innovative approaches to providing a clinical service that were evident in some interviews.

“I think it [telehealth] would only work 15–20% of the time… Prosthetic legs and joints, they break, and your leg shrinks, the socket no longer works, the valves break, a piece of metal might break, sometimes a plastic will erode and corrupt and something inside will rust … I mean, not going to be happy unless I see them, and they look at it. Because it’s my leg, it’s all I’ve got that keeps me going. So telehealth is never going to work for that. If it’s broken, what can I do? He might throw some suggestions at me and generally they won’t work, because it needs their intervention” – Alexander

Challenges with telehealth for young children: The parent/guardian described the challenges of maintaining their young child’s attention span during telehealth appointments, and how this differed to their experience of a face-ot-face appointment.

“It’s hard enough for some adults to sit in front of a screen for an hour, for a one-hour therapy session. That’s the frustration. Whatever day of the week it is, she might just wake up moody and she doesn’t want to be there, in which case the outcome of the session is pretty poor. It’s tricky. Thinking about some of the more successful services locally – there might be (toys) at hand to maintain interest or “trick” the child into thinking they’re playing with the specialist who is treating them – Obviously this isn’t as easily over telehealth.” – John, parent

Value and benefit of telehealth

Most participants experienced some benefit from using telehealth, and all were able to acknowledge the potential value of telehealth. Participants described a range of personal benefits including reduced travel time to their clinical service provider, protecting ones health, or avoiding exposure to unpleasant weather conditions.

“Telehealth is a definite benefit. Because there’s a long, long distance [From home to clinical service provider]. Otherwise, we’d have to travel more often” – Gale

“It’s more convenient. You can jam more into a day, like you go from one meeting to the next… [Telehealth] was way better than having to drive half an hour there and half an hour back.” – Matilda

“I’m immunosuppressed, so I’d rather not travel to the Ring of Steel [a colloquialism for police-enforced road closures that cordoned off Melbourne from the rest of the state of Victoria].” – Alexander

“I knew it was going to be a hot day, and I’m awful in the heat, so I took the telehealth option” – Jane

Matching mode to service needs

While clinical services might be provided using a variety of different modes (e.g., face-to-face, telephone, videoconferencing, etc.) some might be considered more-or-less appropriate based on a wide range of factors including: the purpose of the clinical service, the issue or problem, and user experience with their orthotic/prosthetic needs.

“I think it just depends on what the problem, what the issue, is, as to whether telehealth is the best option or not.” – Jane

“Some of the issues to do with my health are quite personal and scary, so I don’t think a video link would be appropriate for me.” … “If I’m really concerned about something, then I would definitely prefer to see the prosthetist in person.” – Alexander

“The accident was six years ago, so we’ve already put a lot in place. If it was the early days, where we were just starting – I would have felt I needed more face-to-face appointments” – Gale

There seemed to be agreement that telehealth could play a useful role when thoughtfully chosen. For example, many participants held strong views that telehealth was appropriate for triaging and planning appointments, as well as scheduled reviews of a routine nature.

“In that sense, telehealth could be a decision maker, in the course of conversation, they come to a point where they think well, I really need to see this person, in person” … “When planning or touching base, telehealth is satisfactory.” – Gale

“I think a lot of in-person visits, particularly when they are follow-ups, could readily be replaced by telehealth.” – Jane

There were differing views about how each of these factors might be weighted, and some participants held opposing views.

“You’re in the comfort of your own home. So, you might perhaps feel more comfortable to explain any issues that you have going on, as opposed to perhaps being in an unfamiliar environment or an environment where you don’t feel comfortable, or know all the people there, or whatever it might be” – Matilda

“I wouldn’t do a video telehealth…. I suppose I would feel invaded” … “I’m not comfortable doing that” – Gale

This contrast illuminated the value of a person-centred approach to negotiating the mode of care (e.g., the choice to use telehealth, or the way in which is it used) where the individual needs and preferences of individuals are considered.

“I’m sure if you spoke to somebody who doesn’t like technology, then you’d get a whole bunch of different answers [as to whether telehealth is satisfying]. Or somebody who’s rural, again, you’d have a whole bunch of different answers. So, it isn’t a one size fits all … The choice is there. And we live in a country and we live in a system where we are lucky enough to have systems that support the ability to have that choice.” – Matilda

Discussion

The discussion has been sub-sectioned to mirror the aims of the study; specifically, to characterise the population receiving orthotic/prosthetic services using telehealth in Australia, and the types of orthotic/prosthetic services being provided using telehealth. This background provides the necessary context to understand the participants’ experience and satisfaction with both the telehealth mode as well as the clinical service itself. Based on these findings, we have made several recommendations to guide clinical practice and future research.

Population receiving orthotic/prosthetic services using telehealth

Consistent with the broader body of telehealth literature, participants in this investigation likely chose to utilise telehealth because they were comfortable with the mode, felt their treatment needs could be met without a face-to-face service, or for other reasons such as minimising travel time [Citation30]. As such, the reasons for choosing telehealth may challenge our assumptions about who uses telehealth and why. For example, there is a perception that telehealth is most advantageous for people living in regional cities or rural areas without recognising that the issues with access and travel times may be similar for those who travel across a large metropolitan city to their clinical service provider [Citation26]. As such, it may not be surprising that similar proportions of participants in this investigation lived in metropolitan (40%) or regional areas (47%) in keeping with research that suggests people who had to travel longer than about 30 min were more likely to choose telehealth [Citation30]. Similarly, it might be assumed that the technology was a barrier for many older people wanting to use telehealth without recognising the bias inherent in this assumption and evidence describing the experience of older people with telehealth [Citation45–47]. Access to technology (e.g., the internet, smart phones) has become far more ubiquitous, user-friendly, and intuitive over time which has reduced barriers to its use for everyone, not just older people [Citation31]. Many older people have spent their life using increasingly sophisticated communication technology and continue to use that technology for day-to-day activities such as connecting with family or shopping online. This might explain why almost all participants felt comfortable or very comfortable using computers and smartphones for their telehealth service, and why previous telehealth research has shown no difference in satisfaction between those who used the telephone or video conference [Citation48,Citation49].

Participants in this investigation were typical of those living in the community with long-term orthotic/prosthetic needs as reflected by the types of health conditions reported, interventions provided, funding schemes accessed, and the way many participants characterised their long-term relationship with a clinical service provider.

Most participants in this investigation were tertiary educated, female, and lived in metropolitan or regional centres. While most participants were aged between 30 and 59 years of age, participants in the parent/guardian subgroup were about 20 years younger than those in the adult subgroup. These demographic characteristics are similar to other telehealth studies that suggest young-to-middle-aged adult females, and people with high-levels of education, are more likely to access the care they need via telehealth [Citation26,Citation30,Citation48]. While there are complex factors that inform the choice to use telehealth (or not), some studies have suggested that females are more willing to take a more active role in managing their healthcare which may make them better users of telehealth given the greater responsibility to manage the appointment [Citation26].

While the demographic characteristics of participants in this investigation may differ from cohort studies of orthotic/prosthetic users [Citation38,Citation39], it is difficult to know whether participants in this investigation were typical of the subset of orthotic/prosthetic users who might choose to use telehealth; particularly given there are no contemporary studies that described the orthotic/prosthetic users experience of telehealth. It is important to acknowledge that telehealth research describing the experience of orthosis/prosthesis users is dated given the technology available on any smartphone or tablet has superseded telehealth facilitated by professionals in regional hubs [Citation50–55].

Clinical services received using telehealth

In this investigation, most telehealth services were either scheduled (e.g., routine review following fitting of a new device) or unscheduled (e.g., an urgent repair where a device had failed) reviews in keeping with other contemporary orthotic/prosthetic telehealth research [Citation56]. The initial assessments were for a preliminary consultation as would be required to develop an understanding of the client’s goals or to prepare a quote for the funding agency.

Given this characterisation of the types of clinical services provided via telehealth, we hypothesise that orthotic/prosthetic users and clinicians may have self-selected the mode of care appropriate to the goals of a particular service encounter. For example, none of the service encounters delivered via telehealth were for the physical assessment or measurement that would be required for a new orthosis/prosthesis. We suggest that these sorts of clinical service encounters were likely provided in follow-up face-to-face appointments (e.g., post-approval of a funding application, or when stay-at-home orders had been lifted) given that most telehealth encounters required some form of follow-up appointment.

Consistent with the broader body of literature, telehealth services were delivered almost entirely via telephone or video conferencing [Citation26,Citation48] using either mainstream platforms (e.g., FaceTime, Zoom) or clinical practice management software (e.g., PowerDiary). The model of telehealth seemed unrelated to the purpose or duration of the clinical service encounter which challenged our assumptions. For example, we assumed that initial assessments would take longer that routine or unscheduled reviews. However, the initial assessments observed in this investigation did not include the sort of detailed physical assessment, observations, and measurements that would be required to produce an orthosis/prosthesis and as such, it is perhaps not surprising that these truncated initial assessments were of similar duration to many review appointments. There are also likely other factors that influence the duration of these appointments such as the complexity of the fitting issue(s), the practitioner’s familiarity with the details of the user’s orthosis/prosthetic needs, or the extent to which communication is aided by the user’s lived experience or a shared understanding of the issues.

Participant experience and satisfaction with telehealth, and the clinical services received

Given this background understanding of the participants and the types of clinical services received, there is context to describe the experience and satisfaction with the telehealth mode, as well as the clinical services.

Participants in this investigation were highly satisfied with the telehealth mode [Citation26,Citation48]. In keeping with the definitions of the TUQ subscales, the telehealth mode was perceived as easy to use and learn given that it was intuitive and didn’t require deliberate effort. Similarly, the interface was thought to facilitate a high-quality interaction between participants and clinical service providers that was similar to an in-person service [Citation26]. There did not appear to be appreciable differences in the experience or satisfaction based on the mode of telehealth (i.e., telephone or video conference) given that participants and practitioners likely chose the mode most appropriate to the purpose of the service [Citation48]. While there was a high degree of satisfaction with the telehealth mode, participants noted a range of technical issues – the quality of the video or cell phone reception - that negatively impacted the perceived reliability of the mode [Citation26,Citation48]. As highlighted in the interviews, many of the issues affecting reliability with telehealth could be easily addressed with thoughtful planning, such as scheduling the telehealth service (rather than cold calling) to ensure participants were physically located where there was good internet or telephone reception. These experiences with the telehealth mode were similar to contemporary studies that utilised similar platforms for similar types of services [Citation22,Citation26,Citation48,Citation57,Citation58].

As in other studies of telehealth [Citation26,Citation48], participants in this investigation were also highly satisfied with the clinical service they received. Satisfaction with the clinical service seem to reflect:

high-quality interpersonal interactions characterised by clear and open communication, trust, and empathy. While many participants had well-established working relationships with their clinical service provider, there were also examples where practitioners were able to quickly establish an effective working relationship with a new participant given some very high-level interpersonal skills.

that participants had agency and control over the choice of the mode that best met their needs at a particular point-in-time. For some participants, the choice to use telehealth was driven by convenience or a desire to minimise their exposure to COVID-19, rather than the mode that might best meet their orthotic/prosthetic needs. Some participants highlighted that there were trade-offs in choosing the mode, but the ability to choose seemed critical in the overall satisfaction of participants.

that a high degree of health literacy greatly facilitated communication about the purpose of the clinical service as did participation in decision making. Many participants highlighted that their lived experience gave them the skills to know what was required and facilitated their ability to communicate those needs to their practitioner.

It is important to acknowledge that the high level of satisfaction reported by participants probably reflects a degree of selection bias; that is, participants who choose to use telehealth probably did so because they were comfortable with the mode and knew it could meet their needs. Similarly, the well-established and trusting relationship between many participants and their practitioner likely facilitated more meaningful conversations about the suitability of telehealth given the participant’s needs. The agency and control that comes from being able to make the decision to use telehealth (or not) is probably key to participants also feeling satisfied with the mode of clinical service they chose [Citation48].

Limitations

The findings of this research should be considered in light of several limitations.

Given the purpose of this investigation, we considered that the parents/guardians of paediatric orthosis/prosthesis users were active participants in the telehealth service given they act as a conduit between the practitioner and their child. Neither the TUQ nor the OPUS-CSS have been validated for use by a parent/guardian. We hope that by explicitly describing how the instruments were adapted, readers can evaluate the face validity of the changes made.

We acknowledge that the cohort was small and the potential impact this may have on the representativeness of the sample. As we have discussed, not all orthotic/prosthetic users may choose telehealth. In the absence of a well-developed body of telehealth research in orthotics/prosthetics, it is important that we not default to comparing this sample to large cohort studies of orthosis/prosthesis user who may (may not) represent the subsample who choose to use telehealth. Similarly, we should not expect that orthosis/prosthesis users and practitioners will choose telehealth for all types of service encounters (e.g., measurement and casting of a residuum) and as such, it may be inappropriate to expect to see these types of services represented in telehealth research. These reflections highlight the importance of further research to characterise the subsample of orthosis/prosthesis users who use telehealth, and the types of orthotic/prosthetic services provided using telehealth.

Recruitment for this investigation was challenging. Despite partnering with six clinical service providers in three Australian states, we were only able to recruit a small sample over an extended time period. The data collection for this investigation was hampered by COVID-related restrictions. While these restrictions may have created an environment that encouraged many to use of telehealth, clinical service providers were often under great strain given the impact that prolonged stay-at-home orders on the viability of their businesses, their ability to retain staff and provide a high-quality clinical service. Service providers often had a narrow view of what constituted telehealth; something that came to light part-way through our recruitment when we discussed with partner clinical service providers our concerns with the rate of recruitment.

The TUQ includes a 7-point Likert scale that in our survey were anchored by the words “Strongly Disagree” and “Strongly Agree” in line with the OPUS-CSS, rather than “Disagree” and “Agree” [Citation37]. While the results remain internally valid, there are challenges comparing these results to other studies that have used the TUQ.

Recommendations for practice and future research

Arising from the results of this investigation are two key recommendations: the need for a right-touch approach to the regulation of telehealth, and the need for explicit telehealth training for practitioners.

Right-touch regulation of telehealth

Participants had the lived experience to make informed choices about telehealth in partnership with their practitioner. In our opinion, none of the clinical services documented in this investigation were inappropriate for a telehealth mode. This suggests that participants and practitioners were able to make thoughtful decisions about the mode that best meets the participant’s needs, and would fulfill the purpose of the service. As such, the results of this investigation should engender confidence that practitioners are utilising telehealth to provide safe and effective clinical services within their scope of practice.

It is understood that in some parts of the world, state licensure and registration requirements create barriers to the use of orthotic/prosthetic telehealth services that cross jurisdictional lines [Citation59,Citation60]. Aside from questions of business viability, where feasible, policies and registration requirements should be streamlined to support client choice, and right-touch regulation of what appears to be a low-risk clinical service.

There are opportunities for professional associations and regulatory organisations to help achieve the right-touch regulation by ensuring modern standards and evidence-based practice guidance are in place to capture contemporary models of service delivery, such as telehealth. Standards, such as the Code of Conduct and Scope of Practice, must be modernised and ensure they are contemporary and do not hinder the implementation of innovative models of care. In addition, the development of evidenced-based guidelines will support clinical service providers to operate within their scope of practice whilst adopting technologies, such as telehealth, that push the boundaries of typical clinical care. Modern standards and evidence-based practice guidelines will instil confidence in jurisdictional regulators and funding agencies of the quality, safety, and compliance of the services delivered and paid for using new modes of care, such as telehealth. As technology continues to advance, it is important that associations and regulatory organisations are nimble and adopt an evidence-based approach to help ensure that regulation is appropriate to the actual risks and empowers consumers and practitioners to make thoughtful and informed decisions.

Explicit telehealth training

Practitioners new to telehealth would benefit from specific training to avoid common pitfalls; many of which were reflected in the interviews we conducted. Consistent with best practice [Citation61], clinicians should treat a telehealth consult just as they would any face-to-face consult and observe the same professional practices and courtesies [Citation62–65]. For example, the purpose of the clinical service should be clear. Clinical services should be scheduled appointments, not cold calls. If there are specific requirements for the clinical service (e.g., that the telehealth appointment be conducted using a mobile phone to facilitate a practitioner observing gait, or a foot complication) then these requirements should be communicated in advance to prime the clinical service for success.

We encourage practitioners to make use of the free training through both academic institutions [Citation66,Citation67] as well as the providers of telehealth platforms such as COVIU Academic [Citation68]; acknowledging that explicit telehealth training is being incorporated into graduate-entry curricula and continuing professional development programs [Citation69,Citation70].

There are opportunities to promote a more nuanced understanding of telehealth among health professions, funding agencies, consumers, and the public. For example, many of the participants in this investigation had very narrow views about what constituted telehealth (e.g., only video conferencing), and fixed ideas about its utility; particularly given the view that orthotic/prosthetic care needs to be hands-on without recognising that many aspects of care (e.g., goal setting) can be effectively provided using telehealth. These views may limit innovative practice and the development of mature funding streams that are necessary to reduce barriers to the widespread use of telehealth that can help consumers access the safe and effective care they need.

Conclusion

This research shed new light on who uses telehealth and the types of orthotic/prosthetic services provided. While orthotic/prosthetic users were highly satisfied with the telehealth mode, there were technical issues that detracted from the user experience. Many of these issues could be addressed with thoughtful planning that includes scheduled appointments and ensuring users were clear about the purpose of the appointment and any requirements. Orthotic/prosthetic users were also highly satisfied with the clinical services they received via telehealth. Satisfaction with the clinical service highlighted the importance of high-quality interpersonal communication, agency and control over the decision to use telehealth, and a degree of health literacy born out of the lived experience of using an orthosis/prosthesis. There are opportunities to raise awareness and understanding of telehealth among orthotic/prosthetic users, practitioners, professional associations, and funders to ensures access to safe and effective clinical services that fully exploit the benefits of telehealth.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (220.9 KB)Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the support of the many orthosis/prosthesis users who participated in this investigation, and the opportunity it provided to learn more about their experience of using telehealth. We wish to acknowledge and thank the clinical services providers across Australia who partnered in this research and facilitated the recruitment of orthosis/prosthesis users.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

In consenting to this research, participants did not provide approval for their data to be made available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Assistive technology. Geneva: WHO; 2020 [updated 2018 May 18; cited 2020 May 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/assistive-technology.

- Ridgewell E, Clarke L, Anderson S, et al. The changing demographics of the orthotist/prosthetist workforce in Australia: 2007, 2012 and 2019. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):34. 2021/03/17

- Ridgewell E, Dillon M, O’Connor J, et al. Demographics of the Australian orthotic and prosthetic workforce 2007–12. Aust Health Review. 2016;40(5):555–561.

- Wakerman J, Humphreys JS. Sustainable primary health care services in rural and remoteareas: innovation and evidenc. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(3):118–124.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural and remote health. Canberra: AIHW; 2021. updated 22 October 2019; cited 2021 December 17]. Available from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-remote-health/contents/summary

- World Health Organization. Telemedicine – opportunities and developments in member states. Report on the second global survey on eHealth. (Global observatory for eHealth series. Vol. 2). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Downes MJ, Mervin MC, Byrnes JM, et al. Telephone consultations for general practice: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):128.

- Chapman JL, Zechel A, Carter YH, et al. Systematic review of recent innovations in service provision to improve access to primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(502):374–381.

- Luxton DD, Sirotin AP, Mishkind MC. Safety of telemental healthcare delivered to clinically unsupervised settings: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(6):705–711.

- Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, et al. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;16(6):444–454.

- Cottrell MA, Galea OA, O’Leary SP, et al. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(5):625–638.

- Dario AB, Cabral AM, Almeida L, et al. Effectiveness of telehealth-based interventions in the management of non-specific low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Spine J. 2017;17(9):1342–1351.

- Jiang S, Xiang J, Gao X, et al. The comparison of telerehabilitation and face-to-face rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(4):257–262.

- Swanepoel DW, Hall JW.III A systematic review of telehealth applications in audiology. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(2):181–200.

- Ravi R, Gunjawate DR, Yerraguntla K, et al. Knowledge and perceptions of teleaudiology among audiologists: a systematic review. J Audiol Otol. 2018;22(3):120–127.

- Molini-Avejonas DR, Rondon-Melo S, de La Higuera Amato CA, et al. A systematic review of the use of telehealth in speech, language and hearing sciences. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21(7):367–376.

- Theodoros DG. A new era in speech-language pathology practice: innovation and diversification. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2012;14(3):189–199.

- Reynolds AL, Vick JL, Haak NJ. Telehealth applications in speech-language pathology: a modified narrative review. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15(6):310–316.

- Marx W, Kelly JT, Crichton M, et al. Is telehealth effective in managing malnutrition in community-dwelling older adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2018;111:31–46.

- Jaimon K, Allman Farinelli M, Chen J, et al. Dietitians Australia position statement on telehealth. Nutr Diet. 2020;77(4):406–415.

- Jennett PA, Affleck Hall L, Hailey D, et al. The socio-impact of telehealth: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2003;9(6):311–320.

- Orlando JF, Beard M, Kumar S. Systematic review of patient and caregivers’ satisfaction with telehealth videoconferencing as a mode of service delivery in managing patients’ health. PLOS One. 2019;14(8):e0221848.

- Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, et al. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e016242.

- Filbay S, Hinman R, Lawford B, et al. Telehealth by allied health practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic: an Australian wide survey of clinicians and clients. Melbourne, Australia: The University of Melbourne; 2021.

- Wade VA, Karnon J, Elshau AG, et al. A systematic review of economic analyses of telehealth services using real time video communication. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):223.

- Isautier JM, Copp T, Ayre J, et al. People’s experiences and satisfaction with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e24531.

- Binedell T, Subburaj K, Wong Y, et al. Leveraging digital technology to overcome barriers in the prosthetic and orthotic industry: evaluation of its applicability and use during the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;7(2):e23827.

- Cottrell MA, Russell TG. Telehealth for musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;48:102193.

- Moffat JJ, Eley DS. Barriers to the up-take of telemedicine in Australia – a view from providers. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11:1581.

- Reed ME, Huang J, Graetz I, et al. Patient characteristics associated with choosing a telemedicine visit vs office visit with the same primary care clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e205873.

- Dykgraaf SH, Desborough J, de Toca L, et al. “A decade’s worth of work in a matter of days”: the journey to telehealth for the whole population in Australia. Int J Med Inf. 2021;151:104483.

- Taylor A, Caffery LJ, Abrha Gesesew H, et al. How Australian health care services adapted to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of telehealth professionals. Front Public Health. 2021;9:648009.

- Australian Department of Health. COVID-19 telehealth items guide [updated Version 2.1]. 2020 [updated 2021 Dec 08; cited 2021 Dec 17]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/12/coronavirus-covid-19-telehealth-items-guide.pdf

- Australian Communications and Media Authority. Trends in online behaviour and technology usage. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 01]. Available from: https://www.acma.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-02/Trends-in-online-behaviour-and-technology-usage_ACMA-consumer-survey-2020.pdf

- Edmonds WA, Kennedy TD. An applied guide to research designs: quantiative, qualitative, and mixed methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2017. Chapter 17. Explanatory-sequential approach.

- Australian Orthotic Prosthetic Association. Connect with AOPA – clinical corporate partners: australian orthotic prosthetic association. 2021 [cited 2021 May 1]. Available from: https://www.aopa.org.au/about-us/connect-with-aopa

- Parmanto B, Lewis ANJr, Graham KM, et al. Development of the telehealth usability questionnaire (TUQ). Int J Telerehabil. 2016;8(1):3–10.

- Heinemann AW, Bode RK, O’Reilly C. Development and measurement properties of the orthotics and prosthetics users’ survey (OPUS): a comprehensive set of clinical outcome instruments. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):191–206. 2003/01/01

- Jarl GM, Heinemann AW, Norling Hermansson LM. Validity evidence for a modified version of the orthotics and prosthetics users’ survey. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(6):469–478.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. ABS Maps. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2021 [cited 2021]. Available from: https://dbr.abs.gov.au/absmaps/index.html

- Kallio H, Pietilä A-M, Johnson M, et al. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):2954–2965.

- Laforest J. Guide to organzing semi-structured interviews with key informant: safety diagnosis tool kit for local communities. Vol. 11 Charting a course to safe living. Québec: Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec; 2009.

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120–124.

- Castleberry A, Nolen A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: is it as easy as it sounds? Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(6):807–815.

- Global Centre for Modern Ageing. Telehealth – here to stay? Key insights from an expansive study into Australia’s response to COVID-19. Tonsley (SA): Global Centre for Modern Ageing; 2020.

- Brode N. Telemedicine adoption stagnant for first time during pandemic in August: civic science. 2020 [cited 2022 January 20]. Available from: https://civicscience.com/telemedicine-adoption-stagnant-for-first-time-during-pandemic-in-august/

- Raja M, Bjerkan J, Kymre IG, et al. Telehealth and digital developments in society that persons 75 years and older in European countries have been part of: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1157.

- Dennett AM, Taylor NF, Williams K, et al. Consumer perspectives of telehealth in ambulatory care in an Australian health network. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;30(5):1903–1912.

- Rush KL, Howlett L, Munro A, et al. Videoconference compared to telephone in healthcare delivery: a systematic review. Int J Med Inf. 2018;118:44–53.

- Lemaire E, Fawcett J. Using NetMeeting for remote configuration of the Otto Bock C-Leg: technical considerations. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2002;26(2):154–158.

- Lemaire E, Jeffreys Y. Low-bandwidth telemedicine for remote orthotic assessment. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1998;22(2):155–167.

- Lemaire ED, Boudrias Y, Greene G. Low-bandwidth, internet-based videoconferencing for physical rehabilitation consultations. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7(2):82–89.

- Lemaire ED, Smith C, Nielen D, et al. T. 120 application sharing for the remote configuration of prostheses. J Telemed Telecare. 2004;10(5):267–271.

- Linassi AG, Shan RLP. User satisfaction with a telemedicine amputee clinic in Saskatchewan. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11(8):414–418.

- Rintala DH, Krouskop TA, Wright JV, et al. Telerehabilitation for veterans with a lower-limb amputation or ulcer: technical acceptability of data. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2004;41(3b):481–490.

- Eddison N, Healy A, Calvert S, et al. The emergence of telehealth in orthotic services across the United Kingdom. Assist Technol. 2023;35(2):163–168.

- Andrews E, Berghofer K, Long J, et al. Satisfaction with the use of telehealth during COVID-19: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2020;2:100008.

- Beard M, Orlando JF, Kumar S. Overcoming the tyranny of distance: an audit of process and outcomes from a pilot telehealth spinal assessment clinic. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;23:8.

- Whelan LR, Wagner N. Technology that touches lives: teleconsultation to benefit persons with upper limb loss. Int J Telerehabil. 2011;3(2):19.

- Cason J. Telehealth: a rapidly developing service delivery model for occupational therapy. Int J Telerehabil. 2014;6(1):29–36.

- Spelten ER, Hardman RN, Pike KE, et al. Best practice in the implementation of telehealth-based supportive cancer care: using research evidence and discipline-based guidance. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(11):2682–2699.

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. Telehealth guidance for practitioners: Australian health practitioner regulation agency. 2020 [cited 2022 February 7]. Available from: https://www.ahpra.gov.au/News/COVID-19/Workforce-resources/Telehealth-guidance-for-practitioners.aspx

- Medical Board of Australia. Technology-based patient consultations: medical board of Australia. 2012 [cited 2022 February 7]. Available from: https://www.medicalboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Policies/Technology-based-consultation-guidelines.aspx

- Allied Health Professions Australia. Telehealth guide for allied health professionals: allied health professions Australia. 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 7]. Available from: https://ahpa.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AHPA-Telehealth-Guide_Allied-Health-Professionals-May-2020.pdf

- Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Telehealth guidelines and practical tips: royal australasian college of physicians. Forthcoming. Available from: https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/advocacy-library/telehealth-guidelines-and-practical-tips.pdf

- Charles Sturt University. Three rivers UDRD telehealth – embracing technology in healthcare. Charles Sturt University. [cited 2022 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.openlearning.com/csu/courses/three-rivers-udrh-telehealth/?cl=1

- Torrens University Australia. Professional Development. Connecting with telehealth. [cited 2022 Jan 21]. Available from: https://shortcourses.torrensonline.com/catalog/info/id:383

- Coviu Academy. Welcome to Coviu Academy. [cited 2022 Jan 21]. Available from: https://coviuacademy.thinkific.com/

- Monash University. Telehealth – M4024. Graduate certificate. 2022 [cited 2022 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.monash.edu/study/courses/find-a-course/2022/telehealth-m4024?international=true

- La Trobe University. Telehealth training future professionals. 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.latrobe.edu.au/news/articles/2021/release/telehealth-training-future-professionals