Abstract

Purpose

To describe the scope and nature of health concerns, functional impairments, and quality of life issues among adults with brachial plexus birth injury (BPBI).

Methods

A mixed methods study was conducted by surveying two social media networks of adults with BPBI using a combination of closed-ended and open-ended questions regarding the role of BPBI on ones’ health, function, and quality of life. Closed-ended responses were compared across ages and genders. Open-ended responses were qualitatively analyzed to expand upon the close-ended responses.

Results

Surveys were completed by 183 respondents (83% female, age range 20–87 years). BPBI was reported to impact hand and arm use in 80% of participants (including affected and unaffected limbs and bimanual tasks), overall health in 60% (predominantly pain), activity participation in 79% (predominantly activities of daily living and leisure), life roles in 76% (predominantly occupation and parenting), and overall quality of life in 73% (predominantly self-esteem, relationships, and appearance). Significantly more females than males reported other medical conditions and an impact on hand and arm use and life roles. No other responses varied by age or gender.

Conclusions

BPBI affects many facets of health related quality of life in adulthood with variability among affected individuals.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Brachial plexus birth injury’s scope of impact in adulthood is broad, covering every aspect of HRQoL.

The focus of rehabilitation for brachial plexus birth injury (BPBI) through the lifespan should extend beyond improving physical musculoskeletal function and include comprehensive support for physical, emotional, social, and life role concerns.

Brachial plexus birth injury’s nature of impact in adulthood varies among individuals within each aspect of health-related quality of life.

The variability of BPBI’s impact in adulthood underscores the need for individualized, patient-centered assessment and rehabilitative care.

Introduction

Brachial Plexus Birth Injury (BPBI) is the most frequent birth injury and the most common cause of upper limb paralysis in children, with an incidence of 1–3 per 1000 live births [Citation1]. Approximately 30% of affected children have permanent paralysis leading to secondary complications, including persistent weakness, contractures, joint deformity/dislocation, and altered limb growth [Citation2]. Treatment of BPBI is thus multifaceted, focused both on repairing the nerve damage and on preventing and treating the secondary musculoskeletal sequelae [Citation3]. However, current treatments cannot restore normal function, leaving affected individuals with permanent dysfunction and deformity, the long-term impacts of which remain poorly characterized, especially into adulthood.

Studies examining health related quality of life (HRQoL) in adults with BPBI have conflicting findings with measured quality of life ranging from normal [Citation4,Citation5] to globally reduced [Citation6]. This variability in the literature is further complicated by the reported relationships between disability and quality of life varying from high disability and normal quality of life [Citation4,Citation5] to low disability and substantially impacted quality of life [Citation7,Citation8]. These published studies examining HRQoL and outcomes in adults with BPBI use a combination of researcher-selected clinical measures and patient reported outcome measures [Citation4–8]. Similarly, among children with BPBI, lower HRQoL has been reported in various aspects of functioning in studies using a variety of researcher-selected patient reported outcome measures [Citation9–11]. However, when researchers have used a qualitative approach to explore affected children’s and their parent’s perspectives of the child’s quality of life, factors beyond what the patient reported outcomes typically measure emerged [Citation12,Citation13]. Thus, multiple methodologies may be necessary to truly understand HRQoL in this population.

To date, only one small study [Citation14] of adults with BPBI in the United Kingdom offers very limited qualitative perspectives on this population. A mixed methods approach that combines quantitative assessment with qualitative description could provide a more complete identification of the breadth of concerns expressed by adults with BPBI [Citation15]. Because the domains of HRQoL impacted by BPBI remain incompletely defined and may vary widely by person and culture, it is first necessary to identify what affected individuals report as their primary concerns.

Therefore, the current study aims to describe the scope and nature of health concerns, functional impairments, and quality of life issues among adults with BPBI using a survey with both close-ended and open-ended questions. To ensure a comprehensive exploration of these factors, the survey construction and subsequent analyses were organized around the key domains of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation16,Citation17]. The ICF is a conceptual framework which provides a universal language for describing health and disability. The ICF is grounded in a biopsychosocial model of disability that encompasses social and medical models of disability, thus, allowing for a descriptive depiction of an individual’s pattern of functioning. In addition, this study utilizes collaboration with two large, international networks of BPBI-affected individuals for recruitment of participants to overcome limitations of prior small, regional studies.

Study findings will provide a comprehensive report of the HRQoL concerns identified by a large sample of adults with BPBI. This report will help to identify opportunities for improved care for this currently incurable condition across the lifespan. Furthermore, the findings can be applied to help inform future research regarding the measurement, evaluation, and prioritization of treatments of BPBI in adulthood and may inform treatment prioritization in childhood.

Methods

A mixed methods survey design was used to gather complementary quantitative data (i.e., close-ended responses) and qualitative data (i.e., open-ended responses) from adults with BPBI. This design follows the logic of a convergent approach where the two forms of data are gathered concurrently, analyzed separately, and then merged (i.e., the quantitative and qualitative results are compared) for a more comprehensive understanding [Citation18,Citation19].

Participants

Study participants were recruited from the Adults with BPBI Facebook Group and the United Brachial Plexus Network (UBPN).

Adults with BPBI Facebook Group

The Adults with BPBI Facebook Group was founded in May of 2016 by a nurse with BPBI (who is a member of the research team) and two other adults with BPBI. All 658 members of the BPBI Facebook Group are adults with BPBI. This international community covering five continents serves as an unstructured support group to its members. Although membership is open to anyone with BPBI, the membership is predominately female (78%) and residents of the United States (71%).

United Brachial Plexus Network (UBPN)

The UBPN was founded in 1999, with its Facebook support group created in September 2014. International membership to UBPN, covering six continents, includes teens and adults with BPBI and traumatic brachial plexus injury (BPI) and their families. The network also includes professionals such as healthcare providers and lawyers who have an interest in BPBI. The UBPN Facebook support group has 4509 members. The membership is predominantly female (69%) and residents of the United States (59%).

Survey

We developed a survey (see Appendix, Supplementary Material) with three types of questions: screening questions (questions #1–3), demographic questions (#4–10), and questions to understand the impact of participants’ BPBI in the context of health, function, and quality of life (#11–26). Screening questions were designed to ensure that participants met the following inclusion criteria: age 21 or older with a brachial plexus injury that was acquired at birth. Participants whose responses to these screening questions did not meet inclusion criteria were thanked for their interest and the survey was closed. Basic demographic questions such as age, biological sex, affected upper extremity, and medical conditions, were administered to characterize the sample.

For the remaining questions we drew upon the ICF as a frame of reference. Survey questions were not written in direct alignment with the ICF taxonomy, as we suspected participants may not be familiar with the ICF language. Instead, we designed questions with broad, overlapping concepts to accommodate participants’ varied definitions of quality of life, while still covering the biopsychosocial model of the ICF. Survey questions therefore inquired about the following five constructs: hand and arm use, health, activity participation, life roles, and quality of life. For each of these constructs, the survey contained categorical yes/no questions followed by open-ended questions for participants to elaborate with free text.

After receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board at the host institution, data collection was conducted via an electronic survey administered through REDCap from 27 August 2020, until 30 September 2020. The survey link was posted on the social media pages of the Adults with BPBI Facebook Group and the UBPN and sent directly via individual email messages to a subset of 294 members of the Adults with BPBI Facebook Group for whom email addresses were available. A reminder email and link were sent and reposted on the social media sites three times at 2 and 4 weeks following the initial posting. Upon completion of data collection, the anonymous survey responses were reviewed to remove duplicates. Because no personally identifying information was collected, responses were compared to identify responses which contained matching or repetitive information such as age, sex, and unique upper extremity information. Six responses contained identical answers to demographic questions and eight out of the nine close-ended questions appeared to be duplicates. In these instances, the responses with more complete answers to open-ended questions were labeled as complete and retained and the incomplete responses removed.

Data analysis

Consistent with the convergent mixed methods approach, the team first analyzed the quantitative and qualitative databases independently and then integrated the two databases using a merging analysis [Citation18,Citation20]. We performed quantitative and qualitative analysis for each of the five constructs of inquiry: hand and arm use, health, activity participation, life roles, and quality of life.

Quantitative analysis

Traditional measures of central tendency and variability were computed on demographic and categorical data. Additionally, Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests of association were performed to evaluate the relationships between selected categorical responses and biological sex and age groups using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA). All statistical tests were performed at an unadjusted α = 0.05 level.

Qualitative analysis

Coding and thematic analysis was performed on all deidentified responses to open-ended questions. Two researchers (JMD, an occupational therapist, and JW, a nurse and adult with BPBI) completed qualitative content analysis deriving codes from participant transcripts [Citation21]. While the coders’ interpretations of the data were informed by the ICF and five constructs of inquiry (e.g., hand and arm use, health, activity participation, life roles, and quality of life), the coders developed codes inductively based on the meaning of the data within the responses. All qualitative analysis was performed in MAXQDA 2020 (VERBI Software, Berlin, Germany).

For the responses from the first 20 participants, the coders both independently coded each response set and met iteratively to bring consensus to coding and the codebook. The data for the remaining participants were divided equally between the coders to complete all coding. A random sample of 10% of the remaining participants was used to establish inter-coder reliability with both coders independently coding the same data and then meeting to compare coding and achieve consensus for any discrepancies. For the subset of responses which were independently coded by both data coders ([blinded for review] and [blinded for review]) initial inter-coder agreement was 73% [Citation22]. Disagreements were instances in which the coders assigned the same code to a section of text and a second code was applied by one coder which the other coder did not use. For example, one coder assigned the “wrist” code to text referencing “carpel tunnel” when the other coder had not assigned the “wrist” code, yet both coders assigned the code “overuse/misuse” to the same section of text. These situations were discussed to bring agreement to the coding process. Additionally, once all coding was completed both coders reviewed all coded content to bring agreement to all text assigned to each code, such that consensus was reached for all coding.

Throughout the coding process, the coders discussed the codebook and ongoing coding with the research team and recorded reflective memos. Once all responses were coded, the coders met to bring final consensus to all coding. When coding was complete, categories about BPBI impact were identified to describe the types of areas impacted and range of impact. Additionally, frequency counts identified the number of participants who contributed to each major code and theme in order to report percentages of the sample for the codes [Citation23]. Frequency counts were then used to group the codes into three categories. Codes with a frequency of 50% or greater were categorized as “common,” those with a frequency of 20 to 49% were grouped into “less common,” and those with a frequency less than 20% were labeled “uncommon.”

Integrated analysis

After completing quantitative and qualitative analyses, the two data sets were merged, and qualitative responses were used to expand on the quantitative results to develop a more complete picture of participants’ experiences. Complementary quantitative and qualitative results are presented by major construct using a weaving narrative approach [Citation19] with quantitative results followed by qualitative results.

Results

We received a total of 198 survey responses. We removed 6 duplicate survey responses, 7 surveys that did not meet inclusion criteria, and 2 surveys that had incomplete responses to close-ended questions. Survey responses that had all close-ended questions completed were maintained for data analysis even when respondents did not answer all open-ended questions. A total of 183 surveys were used for analysis. We first describe the sample in terms of demographics and other medical conditions after which we report the quantitative and qualitative results in response to the study aims. Participant responses and quotes are referred to by participant number (P###).

Demographics

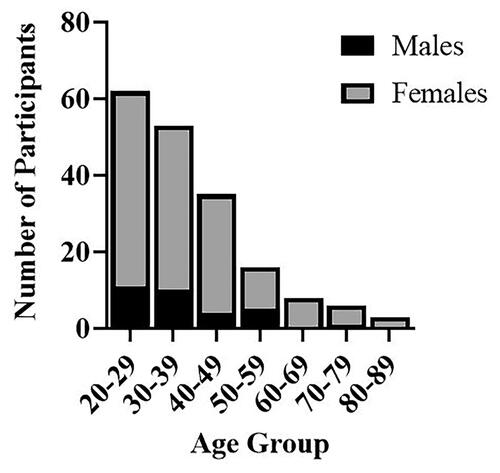

Thirty-one male (17%) and 152 (83%) female participants comprised the study sample. Participant age varied from 21 to 87 years old (M = 38 years, SD = 14) (). The study sample had similar distribution between right (n = 95, 52%) and left affected (n = 83, 45%) extremities, with five (3%) participants reporting bilateral BPBI.

Figure 1. Distribution of biological sex by age (N = 183).

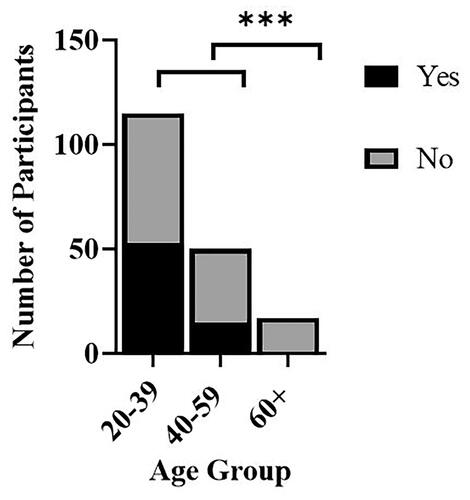

Severity of BPBI could not be precisely determined in the absence of access to medical records. However, participants were asked whether they had undergone surgery in childhood as a proxy for injury severity. A statistically significant relationship between surgical intervention and age was found (X2 = 15.04, p = 0.001). Forty-one percent (n = 68) of participants, all younger than 60 years of age, reported one or more childhood BPBI surgeries (). No statistically significant relationship between surgical intervention and sex of participants (X2 = 1.40, p = 0.236) was found.

Figure 2. Prevalence of surgery on BPBI-affected upper extremity childhood (N = 183). Yes indicates a history of having surgery on the BPBI-affected upper extremity in childhood. No denotes no history of childhood surgery on the BPBI-affected upper extremity. ***p < 0.001.

Other medical conditions

With the understanding that the presence of other medical conditions may be confounders in impacting the participants’ responses, the survey included a question to identify co-existing medical conditions other than BPBI. Forty-three percent (n = 78) of the participants indicated they have medical conditions other than BPBI. No significant relationship was found between age and report of other medical conditions (X2 = 1.91, p = 0.551). A significantly higher proportion of females than males (X2 = 4.22, p = 0.038) reported other medical conditions, with no differences between males and females in qualitative findings outlined below.

Participants reported a variety of additional health concerns in open-ended responses. For example, chronic medical conditions, such as asthma, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and heart disease, were among the health conditions most frequently noted. Additionally, participants reported other health conditions that included a variety of rheumatological, musculoskeletal, neurological, gastrointestinal, and mental health conditions. Two participants reported being cancer survivors.

In responding to the question asking participants if they “have any medical conditions other than a brachial plexus birth injury,” 11% (n = 20) of participants reported medical conditions that they attributed to BPBI. For example, P195 responded, “Myofascial pain syndrome in non-injured arm due to a secondary injury from overuse.” Thus, one cannot draw a clear delineation between health conditions participants perceived to be separate from BPBI and the health conditions they attribute to being related to BPBI with all participant responses to this question.

Impact of BPBI

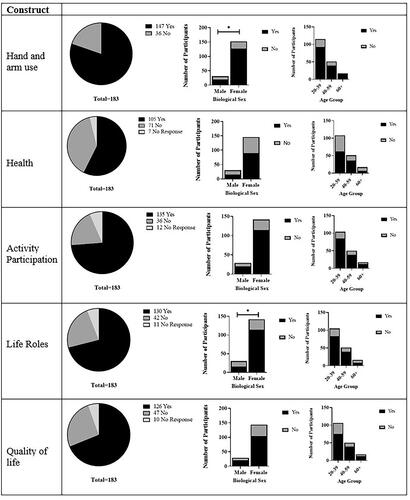

The study aim was to explore the health concerns, functional limitations, and quality of life concerns expressed by adults with BPBI. Thus, we report on participants’ descriptions of the impact of living with BPBI in relation to the five constructs of inquiry (e.g., hand and arm use, health, activity participation, life roles, and quality of life) beginning at the level of the hand and arm expanding to broader scopes of impact and ending with quality of life. Consistent with our convergent mixed methods approach, we report quantitative results followed by their respective qualitative findings for each construct of inquiry with presentation of qualitative findings presented and discussed by frequency of responses. Participant quotes are included to illustrate the different perspectives. Quantitative findings are summarized in and an overview of qualitative findings are provided in .

Figure 3. Quantitative summary of BPBI impact by construct of inquiry. For each of the five constructs overall prevalence of impact is followed by distribution of yes/no responses among sexes and age groups. Yes indicates impact of BPBI on the construct. *p < 0.05.

Table 1. Qualitative summary of BPBI impact by construct of inquiry.

Hand and arm use

Among the five constructs, hand and arm use was reported as impacted by the greatest proportion of participants (80%, n = 147), with no statistically significant relationship observed between age and hand and arm use (p = 0.600). However, a significantly greater proportion of females than males reported that BPBI impacts their hand and arm use (X2 = 5.905, p = 0.015). No differences were elucidated between male’s and female’s qualitative responses that follow.

In the open-ended responses, participants identified a dozen types of impact related to hand and arm use (see ). Commonly, use of affected upper extremity (65%, n = 118) and unaffected extremity (54%, n = 98) were described as affected by BPBI. Less commonly, participants noted BPBI affecting bimanual skills. All other specific hand and arm functions impacted were uncommon among participants. Among these uncommonly cited hand and arm functions, lifting, reaching, and carrying impairments were specified more frequently than grasping and fine motor functions. Most infrequently, participants reported BPBI impacts throwing, catching, pushing, and pulling.

Qualitatively, the range of described impact on hand and arm use varied depending on which upper extremity the participants referenced. When referring to using the affected upper extremity, the range of impact predominantly reflected difficulty or an inability to perform specific hand and arm functions. Reflecting difficulty, P69 described, “[I’m] not completely free to use my left [affected] arm like [my] right. [This] has made some tasks more difficult.” P140 reported, “Fine motor skills are very difficult in the affected arm.” Other participants provided specific references to hand and arm functions they are unable to perform. For example, participants described, “Some things I can’t do, like carry or lift heavy objects" (P97), and “I cannot hold/grasp things with my [affected] left” (P62). Other participants referenced impairments with dexterity, such as the “inability to manipulate stuff with my fingers” (P51). Some participants described using modified techniques. For example, P26 noted, “I catch and throw the ball with the same hand.” Conversely, abilities in fine motor dexterity, reaching, and lifting were reported by some participants. P169 with a left BPBI highlighted an ability, “Strangely, I use my left hand alone for buttoning and unbuttoning.”

Qualitatively participants expressed concerns about the negative impact of “overuse” as the overarching range of impact on their unaffected extremity. Responses reflecting this concern include “The muscles on the right side of my body (non-BPI) side are in frequent pain from overuse” (P62), and “my good arm has had nerve decompression surgery and carpal tunnel surgery twice from overuse” (P46). A propensity to use the unaffected extremity more than the affected was cited as underlying participants’ experience of overuse of their unaffected upper extremity. P85 described this phenomenon when noting, “it became natural to use my unaffected arm for most things” (P85). Another participant described, “I have to use my left [unaffected] hand all the time and it put a lot of strain on left hand” (P135).

The range of impact participants described on bimanual upper extremity function ranged from inability to difficulty with bimanual tasks. For example, P66 stated, “There are simple things I’ve never been able to do—clap my hands, for one.” Other participants expressed challenges when attempting bimanual activities. This experience is reflected in the following responses: “Frustration with menial chores that would involve both arms—reaching into cabinets, changing light bulbs, etc.” (P61), and “How do you keep a child from running out into a parking lot when you juggle keys, a bag, another child, locking the vehicle etc.” (P127).

Health

Most participants (60%, n = 105) indicated BPBI impacts their health. No statistically significant differences were observed across age groups (X2 = 5.172, p = 0.075) or between male and female responses (X2 = 1.40, p = 0.236).

Nineteen types of health concerns from BPBI emerged from participants’ open-ended responses. Most commonly, participants reported pain and range of motion concerns. Less common were reports of strength concerns, mental health conditions, nerve symptoms, muscular symptoms, joint inflammation/degeneration, and spinal conditions. The following were uncommon: altered body development, weight concerns, sleep disturbance, postural concerns, standing/walking impairments, joint instability, eye/vision concerns, headaches, respiratory symptoms, vascular symptoms, and balance concerns.

Qualitatively participants described a broad range of experiences with pain. Some participants reported “chronic pain” or “hav[ing] constant pain.” Others described pain in terms of “aches from overuse” (P28) or “occasional arm pain” (P29). Some participants described experiencing “nerve pain” or “muscle pain.” Among all participants, pain was reported in a variety of anatomic regions, including the neck, face, shoulder, arm, hand, wrist, fingers, back, lower extremities and in the unaffected upper extremity. Some participants noted their pain has increased with age, and others expressed a concern that their pain will increase as they age. One participant stated, “I fear my arm will get worse as I get older because the pain has gotten worse as I got older” (P148). Some participants reported experiencing pain while participating in specific activities while others reported avoiding specific activities because of their pain. Pain was reported to impact sleep, mental health and/or quality of life for some participants. One participant stated, “The nerve spasms and pain also take away life quality” (P31), while another stated “Always in pain cause[s] depression” (P119). Some participants reported using specific interventions (e.g., therapy or medication) to manage their pain while others expressed a desire for improved pain management.

When referring to concerns with range of motion, most participants made general comments about the range of impact. For example, when referring to range of motion concerns in their affected upper extremity, participants reported having “limited range of motion,” “stiffness,” a “lack of mobility,” or “limitations in movement.” Other participants provided more descriptive explanations of the range of their range of motion concerns. For example, P85 stated, “my affected arm does not fully straighten, and my scapula/shoulder often pop out of place to compensate.” Other participants described range of motion limitations in other regions of their upper body. P62 reported, “losing strength/ROM [range of motion] in my non-BPI arm,” and P74 stated “[I] can’t turn my neck.” Some participants described experiencing declining range of motion in their affected upper extremity with age. One participant described “experiencing a loss of mobility in my injured arm as I get older. Now I cannot get my hand up to my head. Even to touch my face is no longer possible” (P101). In contrast, other participants described having abilities with respect to their range of motion in their affected upper extremity. For example, P76 reported “my motion range is fairly decent,” and P117 stated, “I’m very fortunate in the fact that I have high mobility with my BPI arm. I have never sought care for my BPI as my mobility in that arm is extremely high.” Some participants described performing stretches or specific activities to maintain range of motion in their affected upper extremity, while other participants described accessing therapy services to address range of motion concerns. P34 described this phenomenon remarking, “I have been swimming for 34 years to try to keep some range of motion.” Other participants expressed hope that range of motion can be improved. P135 expressed, “I pray they will come out with a way to help me with mobility and to be able to open up my hand and raise my arm up high.”

While reported less commonly than range of motion concerns, most participants also made general statements regarding the range of their strength concerns in their affected upper extremity, reporting “weakness” or a “lack of strength.” Some participants compared their strength in their affected upper extremity to their unaffected. For example, P107, reported “My BPBI arm is much weaker and tires or aches quicker than my non-injured arm.” Other participants described strength concerns in other regions of their body. P130 reported, “[my] muscles on the non-BPI side that have begun to atrophy,” and P178 described “decreased muscle girth and strength on the entire right side of my body—shoulder, back, buttocks, leg, calf.” Some participants provided examples of the range of their strength impairments. P26, who reported having to handle large reference books at work, stated, “sometimes the books are very large and (to me) heavy,” and P93 described, “I have only 30% movement and strength.” Specific examples of strength concerns impacting function were provided by some participants. P62 stated, “I’ve noticed I’m dropping things more often as my grip is getting weak.” P178 also remarked, “I transfer and lift patients often and need to compensate for lack of range and strength in my R [right] arm for almost all aspects of my work.” Some participants also expressed a decline in their affected upper extremity’s strength with age. For example, P13 stated, “as I grow older, it continues to weaken.” Some participants described actively engaging in therapy or fitness training during childhood and their adult years to improve strength in their affected upper extremity. P65 remarked, “I actively work on strengthening my affected arm and have done so consistently for several years.” Another participant expressed, “I exercise and the more I work my BPBI arm, the stronger it gets” (P180). Like range of motion limitations, a desire for improved strength in the affected upper extremity was expressed with comments such as, “any possible treatment to strengthen my BPBI will be great” (P58).

Among reported mental health conditions attributed to BPBI, participants most frequently noted experiencing anxiety and/or depression. Participants either reported having general anxiety or experiencing social anxiety. A participant described, “I have had serious anxiety about people staring at my arm, having to ask for help, or being put in situations where I might not be able to do an activity because of my arm” (P51). Similarly, some participants reported either having depression or feeling depressed because of the limitations experienced from having BPBI. One participant remarked, “BPI has had a major impact on [my] perceived self-worth, contributing to life-long depression” (P127). Other participants cited the mental impact of their BPBI in broader terms. One participant stated having BPBI was “mentally draining” (P106). Another reported, “The emotional suffering has been bad” (P107).

Among participants who described experiencing nerve symptoms the range of impact varied. Some participants reported experiencing sensory symptoms such as impaired sensation, numbness, tingling, pins and needles, or hypersensitivity in the affected upper extremity. Nerve compression conditions, including carpal tunnel syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome, and sciatica were reported among some participants. One participant described, “My sciatica is a daily struggle, and it can be linked back to my arm” (P34). Other nerve symptoms reported include “nerve pain,” “nerve spasms,” and extrasensory symptoms (i.e., changes on nail growth or diaphoresis). A participant described, “I have to take ongoing medication for nerve pain” (P86). Another stated, “nerve spasms lower my quality of life tremendously” (P31).

The variety of less commonly reported musculoskeletal conditions include muscular symptoms, inflammatory or degenerative joint and tendon conditions, and spinal conditions. The range of these musculoskeletal conditions was broad. Muscular symptoms ranged from muscle tightness to muscle spasms, to concerns with muscle control. Examples of muscular symptoms included remarks such as “tightness in my neck and elbow” (P34), “extreme muscle spasms in my BPBI arm” (P66), and “I barely can control my BPBI arm” (P52). Several inflammatory or degenerative joint and tendon conditions were reported. Participants referenced arthritis in their back, neck, and jaw which they attributed to BPBI. For example, P95 stated, “I have arthritis in [my] neck from my BPI arm being pretty much dead weight.” Some participants also reported arthritis, tendonitis, rotator cuff pathology and bursitis in their affected upper extremity while others noted these pathologies in their unaffected upper extremity. Spinal conditions which participants attributed to BPBI included both general references to BPBI affecting their spine and specifically reporting having scoliosis. These phenomena are reflected in statements such as “the way I lean and sit can contribute to the worsening of my back angle to one side” (P131), and “it has started to pull my back out, creating a scoliosis” (P116).

Infrequently participants noted altered body development, weight concerns, sleep disturbance, postural concerns, standing/walking impairments, joint instability, eye/vision concerns, headaches, respiratory symptoms, vascular symptoms, and balance concerns. Alterations in body development were described through responses such as “My left [BPBI] arm has much less muscle mass and is shorter” (P68). Participants who noted weight concerns expressed perspectives such as, “minimal physical activity contributes to weight challenges” (P130). Participants described experiences such as BPBI causing “poor, uncomfortable sleep” (P165), “all kinds of muscle and posture issues” (P23), and “walking is limited because gravity is not a friend of BPI arm” (P62). Reported joint instabilities include shoulder instability or dislocation in the affected upper extremity, and Horner’s syndrome was the most cited eye concern. Some participants attributed headaches to BPBI, remarking, “I have a slight suspicion that my chronic migraines are due to my brachial plexus injury, but doctors don’t really know why I have chronic migraines” (P173). Respiratory symptoms were described as “breathing issues” (P22) attributed to BPBI. Vascular issues attributed to participants’ BPBI were lymphedema and “poor blood flow on the right side [affected] of my face” (P23).

Activity participation

Most participants reported their BPBI impacts their participation in activities (79%, n = 135) with no statistically significant differences found between age groups (p = 0.415) or between males and females (X2 = 2.09, p = 0.148).

Qualitatively, the types of areas impacted are diverse. Some participants broadly mentioned the impact of their BPBI on general activity participation with statements such as “It [BPBI] impacts my ability to [participate] in some activities” (P172). Such responses that do not cite a specific activity are reported as “general activity participation” in . Responses which include specific activities are categorized by the type of activity the participants referenced. Most commonly participants noted BPBI impacting activities of daily living (ADLs), sports and recreation, general activity participation, and exercise. Uncommonly, BPBI was noted to impact participation in performing and visual arts, typing/using computers, writing, hobbies, communication, and physical intimacy.

The range of impact on activity participation was also broad and varied across types of activities impacted. For ADLs, the reported impact varied from difficulty or limitations performing the tasks, to needing to use modifications or assistance, to being able to perform specific ADLs without difficulty. One participant reported “It takes me longer to get dressed” (P26) and another noted “I do depend on family members to help me with my hair, cutting food, cleaning, folding laundry, doing dishes” (P150). However, other participants remarked “I can drive, dress myself (mostly)” (P130) and “I am able to cook” (P79). Similarly, for all other activities, except for hobbies and writing, most responses reflected difficulties, noting limitations or the need to adapt the activities to perform them. Participations had responses such as “I can’t swim or do things like yoga, which I had always wanted to do” (P61), and “I always require an ergonomic keyboard in order to type pain-free” (P54). Conversely, for both hobbies and writing, abilities were noted. For example, one participant responded, “I am able to have hobbies such as horseback riding that require me to use both of my arms” (P139), and another who reported having a right BPBI remarked “I still use my right hand for writing and drawing” (P113).

Life roles

Most participants reported their BPBI impacts their life roles (76%, n = 130), without varying significantly with age (p = 0.078). Significantly more females than males (X2 = 9.75, p = 0.002) reported BPBI impacts their life roles, but sex differences were not evident in the qualitative findings described below.

Most commonly, participants described BPBI as impacting their career/occupation. Less commonly, the role of parent/caregiver and infrequently roles as student and coach/instructor were noted to be affected by BPBI (). Qualitative responses depict the range of impact for each life role and are presented according to each life role as follows.

The spectrum of impact upon participants’ careers/occupations varied from participants reporting BPBI has resulted in the inability to work to participants reporting their ability to assume a specific career. The inability to work includes experiences with unemployment, disability, and early retirement. On the other end of the continuum, participants reported having careers as teachers, nurses, and scientists. Yet, reported experiences of impact fall within this continuum. Some participants reported difficulty finding or maintaining employment. One participant remarked “employment is hard because people see your disability and are not willing to waste their time on you” (P143). Being limited in feasible career options or in promotions within one’s job was also reported. For example, a participant stated, “I wanted to join the Navy when I was young but couldn’t pass the physical” (P61). However, other participants reported being unable to perform specific job tasks, having reduced productivity in job functions compared to colleagues, or having to use modifications at work. For example, P83 reported, “I cannot reach certain things or lift heavier objects due to weakness in my left [affected] arm.” Reflecting the need to use modifications, a participant who reported being a nurse remarked, “I had to find my own way to do things, including taking blood pressure” (P123).

Less commonly, participants reported BPBI affects being a parent/caregiver. The range of impact on parenting was also varied. BPBI was reported to impact participants’ ability to care for their children, such as bathing them, changing diapers, and fixing their children’s hair. Participants referred to impairments experienced when caring for infants and toddlers more than caring for children at other developmental stages. P29 described: “Taking care of my son when he was a baby … Just being able to hold him properly, carry him around, breastfeed, change him, etc…. were slightly more challenging” (P29). Additionally, participants described limitations in which specific activities they can participate in with their children. P31 responded “I cannot do everything my child wants me to do due to it being difficult to do something as simple as holding an object (toy).” Using adaptations to complete parenting tasks, such as having to modify a stroller was also reported. Among participants who are not parents, some expressed concern that either BPBI will impact their ability to care for children or that their child may acquire BPBI during birth. P71 expressed this concern as follows:

Whilst not a parent yet, I am very much aware of how my arm will affect that. I will have to hold a baby one handed, feed them, change them, dress them one handed and whilst all can be adapted to. For me, the mental effects are more concerning. Will my future children resent my arm? Will they be picked on because of it? Or will it have a positive impact on them and their life?

Quality of life

Most participants reported that BPBI impacts their quality of life (73%, n = 126). No statistically significant relationship was found between age (p = 0.596) or biological sex (X2 = 0.003, p = 0.956) and quality of life.

In addition to BPBI impacting life roles and activity participation described previously, participants described BPBI impacting quality of life in terms of emotional health and relationships. The emotional impact of having BPBI was commonly noted among participants. Less commonly, participants reported BPBI impacting their relationships.

The range of emotional impact spans a breadth of perspectives which are reported in descending order of frequency (). Fear/worry was expressed in several ways. Some participants expressed health related fears, such as “I’m highly concerned about eventually losing the use of my ‘unaffected’ arm due to overuse” (P99). Participants also reported fears that impact their activity participation. Statements, such as “I limit myself even in activities I can do as I am scared to hurt my non BPBI hand/arm” (P36), reflect this concern. Also, fears were expressed pertaining to life roles, either related to concerns with being able to perform occupational demands or related to parenting as previously described. Additionally, concerns that participants’ BPBI will cause them to lose independence with aging was expressed. For example, one participant stated, “My biggest concern is that my condition will continue to get worse as I get older (it already has) to the point that I will not be able to take care of myself” (P188).

A range of other negative impacts on emotional health were also reported. Some participants described feeling BPBI negatively impacts their self-image, self-confidence, or self-worth. Statements reflecting this perspective include “It has caused insecurities” (P69), and “I have struggled with confidence and self-worth” (P39). Some participants made remarks suggesting a desire for different circumstances, such as “I just wish there was something I could do to change it” (P81), and “I wish I were able to be more athletic” (P35). Other participants expressed the feeling that it is hard to have BPBI with comments such as “Mentally and emotionally, having BPBI is draining and discouraging” (P83), and “Having limitations is a big deal when it comes to living a full and happy life” (P58). Additionally, some participants expressed frustration, with statements such as “I get frustrated trying to do “‘simple’ tasks” (P194). Other participants expressed anger about having limitations.

Other reported emotional health impacts of having BPBI include feeling disabled, feeling resigned/helpless, and feeling wronged. P176 remarked, “I love who I am, but I can’t pretend that my life might not be better if I were never subjected to discrimination because of my disability.” Another expressed “Obviously, this is quite debilitating and leaves me feeling helpless sometimes” (P68). Other participants expressed feeling wronged, stating “It has taken so much away from me” (P134).

In contrast, participants also described experiences with coping, such as “I have adapted well” (P51), “I make the best of it” (P46), and “I do not feel sorry for myself and feel good about my accomplishments” (P70). Some participants also conveyed acceptance of having BPPI, not knowing any differently, determination, and feeling fortunate as perspectives of BPBI’s impact on their lives. P71stated “For the most part it’s no different to others’ lives. Having had my injury all my life, I know no different which works to my advantage as I’ve had to adapt as I go along.” Another participant responded, “But, in other ways, it motivated me—for example, in sports. I was actually a very good athlete in spite of my BPI arm. I wanted to be as good as—if not better—than the other kids I was competing against” (P187). Expressions of gratitude included statements such as “I’m fortunate that I’m not in a lot of pain” (P90), and “It’s made me appreciate life a lot more” (P134).

BPBI’s impact on relationships was less commonly reported by participants. Participants described a variety of ways BPBI impacts relationships. Some participants mentioned discomfort engaging in romantic relationships. For example, one participant stated, “Dating is another challenge—some people aren’t interested in dating a disabled person” (P176). Others expressed they feel compelled to hide their arm or explain BPBI when dating. When noting activity limitations, some participants mentioned these in the context of socializing with family or friends. One participant reflected, “I have friends that are very physically active, and I frequently cannot join in some of their activities” (P117). Varying degrees of impact on social participation were described. Some participants reported avoiding group exercise classes or activities such as dancing in public while other participants stated they “avoid being around people” (P46). In contrast, other participants noted BPBI has impacted their relationships in beneficial ways. Participants described their condition as helping them “connect with people with any paralysis” (P110) or fostering a sense of empathy towards others.

Participants also made general references to how others react to their condition, such as “people star[ing]” (P16). In addition, participants expressed feeling that others have preconceived perceptions of their abilities. For example, one participant stated, “Since it [BPBI] is not noticeable, others frequently have expectations of me that I cannot fulfill” (P124). Participants also described experiences with bullying, lack of understanding, and discrimination. One participant remarked “I definitely experienced lots of intrusive questions and occasional bullying” (P162). One participant reported feeling “misunderstood” (P67), while another stated “It is challenging because only a couple of people in my life truly understand my injury” (P98). Others provided specific examples of experiencing discrimination. For example, a participant remarked, “Well, I know for sure of at least one role I auditioned for that the production team conceded I was the best choice for but didn’t choose me because of my arm. I’m willing to bet that’s happened a lot more than I know about” (P176).

Discussion

The current study, surveying two large, international populations with a combination of open-ended and close-ended questions, describes the scope and nature of health concerns, functional impairments, and quality of life issues among adults with BPBI. Using five constructs of inquiry the current study elucidated the impact of BPBI in adulthood broadly on HRQoL. Thus, the findings from this study help us to identify the HRQoL factors considered relevant by affected individuals. Some of the current study’s findings are consistent with prior studies and some findings are novel, yet together they help to reconcile previous studies’ conflicting findings, shedding a more holistic light on the breadth of impact of BPBI in adulthood. From this starting point, we can begin to identify opportunities to improve care throughout the lifespan for individuals affected by BPBI.

Prior findings of BPBI’s impact in adulthood

Prior attempts to determine the impact of BPBI in adulthood have utilized a variety of research methods and samples and have yielded conflicting findings. Methods have varied in the outcomes assessments used. One study used clinical measures only [Citation24], Patridge and Edwards [Citation14] developed and used a symptoms checklist survey, two studies only included clinician-selected patient reported outcome measures [Citation6,Citation8], and all other studies employed a combination of clinical measures and clinician-selected patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7]. Most studies included small convenience samples of adults with BPBI, ranging from 8 to 50 participants, who had received care in region specific clinics during childhood [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7,Citation8,Citation24]. Two studies drew study participants (N ≤ 50) from a national (UK) BPBI support group [Citation14,Citation25].

Studies examining pain found results ranging from varied experiences with pain among adults with BPBI [Citation14] to pain being the greatest driver of patients’ overall quality of life [Citation7]. Impaired upper extremity function was observed in 3 studies [Citation5,Citation7,Citation24]; however, measures of physical function ranged from impaired physical function [Citation4] to normal physical function [Citation5]. Similarly, quality of life outcomes were variable. Yau [Citation25] elucidated decreased quality of life compared to population norms while other authors report good quality of life [Citation4,Citation8]. Some studies reported no psychosocial concerns in their study populations [Citation4,Citation5], despite findings of concerns with appearance in other studies [Citation14]. The one study examining activity participation revealed that impaired activity participation did not correlate with severity of injury [Citation7].

Each of these prior studies have attempted to draw generalized conclusions about the long-term impact of BPBI in adulthood, but their conflicting findings limit such generalization. It is possible that these conflicts arise because of the use of different specific measures with preset item banks failing to capture the full breadth of relevant patient concerns, or because of the distinct and specific populations queried.

Impact of BPBI

Therefore, in contrast to these prior focused studies, the current study sought to assess the comprehensive breadth of impact of BPBI in adulthood by surveying two large, international populations, using open-ended and close-ended questions relating to five overlapping constructs: hand and arm use, health, activity participation, life roles, and quality of life. Among these constructs explored, roughly three quarters of participants reported BPBI impacts their hand and arm use, activity participation, life roles, and quality of life. Sixty percent of participants reported their BPBI impacts their health with most participants attributing health concerns they experience to their BPBI. Across all constructs, qualitative data revealed a broad range of impact—people have unique experiences in terms of the type and severity of impacts they report. Nonetheless, important findings can be distilled from examination of the results in each construct.

Hand and arm use

It is not surprising that among the 5 constructs, hand and arm use was reported impacted by the highest proportion of participants. Most participants described the impact of BPBI on the extremity directly affected by the injury, citing gross and fine motor difficulties. These findings are consistent with prior studies that describe a variety of limitations in the affected upper extremity [Citation5,Citation7,Citation8,Citation14].

Interestingly, half the participants also attributed concerns with their unaffected upper extremity to their BPBI, with overuse of the unaffected extremity being the predominant concern. The effects of unilateral BPBI on the contralateral upper extremity have not been fully elucidated in prior research. Impairments in the unaffected extremity function among children with BPBI were found to resolve after 8 years of age [Citation26]. In adults with BPBI, functional assessments have revealed normal functioning in the unaffected extremity [Citation7], yet overuse pain in the unaffected extremity was elucidated in a survey study [Citation14]. Thus, it remains unclear the extent that unilateral BPBI directly affects the functionality, durability, and symptomatology in the contralateral unaffected extremity. However, the current study clearly elucidates the hand and arm use concerns of affected individuals are not confined to the originally injured extremity.

In addition, a third of participants described impact on bimanual tasks, consistent with prior studies demonstrating impaired bimanual skills among unilaterally affected children with BPBI [Citation27–29]. The concerns regarding bimanual hand use raised by participants in this study highlight the importance of bimanual skill training in rehabilitative efforts [Citation30]. It is important to note that the survey questions related to hand and arm use did not specify the extremity in question, so the focus on contralateral and bimanual hand and arm use is reflective of the participants’ own concerns.

Health

The impact of BPBI beyond the affected extremity can be similarly noted in the responses to the questions regarding general health. A wide range of health conditions were reported. The developmental biological effects of BPBI span multiple organ systems from the brain and spinal cord to the muscles, bones and joints in the affected limb [Citation3]. It is also possible that BPBI could disrupt development of other organ systems beyond the affect arm. For example, the finding of abnormal speech development in children with BPBI has been postulated a causative link between limb use and speech lateralization during postnatal brain development [Citation31]. However, the clinical effects of this injury on symptomatology in other systems not directly related to the affected limb remain poorly characterized. For instance, prior authors have found no increased prevalence of structural spine (e.g., scoliosis) or lower limb deformities in children and young adults with permanent BPBI [Citation32], whereas others have reported adults with BPBI frequently attribute scoliosis to their BPBI [Citation14]. Nonetheless, as with hand and arm use, the current study’s participants perceive a wide array of health conditions as related to their BPBI, warranting further research into potential connections between BPBI and other health problems.

Despite the unclear relationships between BPBI and other physical health conditions, the most striking finding in the survey responses regarding overall health was the predominance of reported pain. Prior studies examining the patient-reported outcomes in children and adults with BPBI have reported conflicting findings regarding pain, ranging from childhood pain similar to the general population [Citation11] to significantly worse childhood pain than the general population [Citation33]. Prior authors examining pain in adults with BPBI, have found it to be the most common symptom [Citation7,Citation14], with pain being the largest driver of worse overall function, including psychosocial function [Citation7]. Furthermore, pain was found to worsen over time [Citation7] and exist in body regions beyond the affected arm [Citation7,Citation14] Conversely, a study assessing shoulder pain, function and deformity in adults with BPBI found minimal pain despite substantial deformity seen radiographically [Citation5]. These discrepancies in pain findings may result from the use of different measures, or from actual variability in the pain experience among affected individuals. Indeed, in the current study, not all participants reported pain. Thus, despite the common description of pain as a health concern, it cannot be assumed to be universal, highlighting the individuality of the long-term impact of BPBI, and underscoring the need for individualized assessment and care for affected individuals.

Given the nature of BPBI, range of motion and strength impairments are commonly reported sequalae of BPBI [Citation3]. Thus, finding these concerns among participants in the current study was not surprising. The prevalence of reported mental health concerns, predominantly depression and anxiety, is a more remarkable finding in the current study. The psychological impact of BPBI in childhood has been examined, with conflicting findings. Using the Pediatric Data Outcomes Collection Instrument (PODCI) Happiness scale, some authors have found significantly worse scores than the general population [Citation33,Citation34], whereas others have found scores no different than the general population [Citation35]. Such a scale may not clearly elucidate the psychological impact on patients, especially when parent proxy instruments are used. This relationship is complicated by the psychosocial impact of the BPBI on the family itself [Citation36]. In addition, the psychological ramifications may differ over the life span into adulthood. Prior studies on BPBI in adolescents and adults have demonstrated no differences between adults with BPBI and the general population on the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression and Anxiety scale [Citation5] and no psychiatric symptomatology on formal psychological screening [Citation4], whereas others have found worse psychosocial function associated with worse pain [Citation7]. Variability existed in our study participants’ responses regarding mental health concerns as well, in that not all participants reported mental health impacts. Nonetheless, those who reported mental health concerns predominantly related the concerns to the BPBI, either as a cause or a target of the concerns. Therefore, in seeking to improve quality of life for affected individuals, the psychological concerns surrounding the condition must not be overlooked.

Activity participation

Activity participation was also reported to be impacted by most participants, primarily involving activities of daily living, sports, and leisure activities, and driven by physical limitations, psychosocial concerns, and fear. However, while some participants described limitations others remarked on abilities to participate in activities. This breadth and diversity of impact on activity participation is consistent with seemingly conflicting findings of prior studies in both children and adults. Prior studies have found children with BPBI engage in similar levels of sports [Citation37] and school and leisure participation [Citation38] as unaffected peers. While expressed worry about risk of injury was discovered [Citation38], an increased risk of sports related injury was not found [Citation37]. In some prior studies BPBI-affected adults have demonstrated disability on the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) and QuickDASH scales including the work and sports/music modules [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7], whereas in another study DASH scores were consistent with the general population [Citation8]. A study specifically aimed at evaluating activity participation in adults with BPBI found no overall quantitative differences in participation between affected adults and the general population, although a majority of participants described restrictions from their BPBI affecting choices and performance in work, education, leisure, and/or social activities [Citation8]. It is possible that quantitative scales measuring overall activity participation are missing the decisions or adaptations that are required for such participation among affected individuals. Therefore, additional research exploring the modifiable barriers to participation in a variety of activities should include learning from the adaptations made by affected individuals.

Life roles

Among life roles reported as impacted by BPBI, employment was the most commonly cited. Employment has been investigated in prior studies of adults with BPBI, with seemingly conflicting findings. One study found limitations in shoulder function that were not reported to limit performance of the participants’ chosen occupation [Citation5]. However, these investigators did not ask about the impact of the BPBI on the choice of occupation, which was found to be a consistent concern among our study’s participants. Another prior study found employment to be the most impacted life role among adults with BPBI, with problematic restrictions in employment reported by 80% of affected individuals [Citation8]. In the current study participants reported a broad range of impact on employment, including some highlighting their abilities to perform in their varied occupations, once again illustrating the diversity in experiences with BPBI as an adult.

Parenting was a less commonly reported life role impacted by BPBI in our study. Parenting has not been a focus of prior research on adults with BPBI, but our study reveals parenting to be a relative microcosm of the effects of BPBI in adulthood. Participants reported the impact of BPBI on parenting to include physical limitations in hand and arm use, as well as restrictions in the activities in which they can participate with their children. Furthermore, the emotional impact of BPBI on parenting was apparent, including worry among participants who were not yet parents, and guilt among parents who felt they were depriving their children of opportunities because of their own BPBI. Overall, knowledge is limited regarding the impact of adulthood physical disabilities on parenting, as well as opportunities to improve affected individuals’ experiences in this important life role [Citation14]. Our study adds weight to the call for further research.

Quality of life

Overall quality of life was reported as impacted by most participants. Importantly, “quality of life” was not defined for the participants in our study; rather participants were free to interpret the phrase according to their own definitions. Not surprisingly, many participants described restrictions in participation and life roles in response to questions regarding quality of life, and these findings are discussed previously. However, most commonly participants described emotional impacts when discussing the impact of BPBI on their quality of life. These emotional impacts and the relevant prior literature on the topic are described in part previously in the impact of BPBI on psychological health. It is striking that quality of life was defined in emotional terms by a majority of participants, further emphasizing the importance of holistic medical care focused on psychological and emotional care.

Fear was a commonly mentioned impact, often revolving around the unknown prognosis of this injury and its sequelae later in life. This finding highlights the need for increased awareness of the long-term prognosis among healthcare providers and affected individuals, as well as the need for additional research regarding the long-term impact of BPBI across the lifespan. The emotional impact was not uniformly negative, however. While some participants described strongly negative feelings of anger or hopelessness associated with their BPBI, others derived motivation from their injury and attributed their achievements to their experience with the injury. Others also described positive coping strategies. Thus, not only must we focus efforts on providing psychosocial support to affected individuals throughout the lifespan, but we must also not assume the impact of the injury to be uniformly negative. Again, learning from the resiliency of positively affected individuals may hold clues for support of others more negatively impacted.

Relationships were a less commonly reported area of impact on quality of life. While some participants cited physical limitations restricting leisure or intimate activities as drivers of this impact on relationships, most described the emotional impact related to others’ perception of the disability. The impact of BPBI on body image has been previously shown to cause social difficulties in adolescence [Citation12] and adulthood [Citation14]. In fact, the social and peer impact of BPBI has been revealed to be a primary driver of quality of life among affected adolescents [Citation39]. However, the potential impact of the social stigma of BPBI is understudied relative to the physical limitations, despite being a predominant component of quality of life in our study and prior studies. Opportunities exist to identify modifiable drivers of this impact within affected individuals’ social context. For instance, the aesthetic deformity of the elbow flexion contracture following BPBI is a primary driver for adolescents to seek treatment [Citation40]. While healthcare providers treating such contractures, including orthopedic surgeons, occupational therapists, and physical therapists, may base treatment decisions on the potential to improve physical function, social function due to aesthetic concerns must not be overlooked as a critical component of overall quality of life. Nonetheless, as with emotional impact, it is important to note that the impact of BPBI on relationships was not uniformly negative, as some participants reported that their BPBI increased their empathy toward others with disabilities.

Overall, despite the heterogeneity in the study sample regarding the nature and range of impact on quality of life, overall quality of life was reported to be good. This finding is consistent with prior studies on adults with BPBI finding quality of life in the normal range on the Peds QL and WHO-QOL-BREF [Citation4] and the SF-36 [Citation7,Citation8].

Strengths

Advantages of the current study include features of the populations sampled, characteristics of the study questionnaire, and the power of mixed methods research. First, the two social media groups sampled together comprise over 5000 members from 6 continents, although to ensure anonymity we did not inquire about geographic location. While it is not possible to ascertain how many of the UBPN members are themselves adults with BPBI, our screening questions ensured the full survey was provided only to individuals who indicated an age of 21 or greater. Furthermore, all members of the Adults with BPBI Facebook Group are vetted by the site administrator who is a member of the study team. Collaboration with these groups provided unprecedented access to geographically diverse populations and generated the largest study sample to date from which to ascertain the breadth of impact. Furthermore, the broad age range of study participants shed important light on perspectives at different life stages, such as younger participants worrying about the future and older subjects reflecting on changes they have experienced over their lifespan. Second, the use of broad, open-ended questions in the study questionnaire allowed participants to directly focus on concerns relevant to them, not what was assumed to be relevant by the study investigators. Similarly, the use of the WHO-ICF to ensure inclusion of broad HRQoL domains, although advocated in other musculoskeletal conditions [Citation41], is novel in this population. In addition, using questions regarding overlapping domains of impact allowed variety in participant definitions of disease impact and quality of life. Such variety was seen in qualitative data from responses that overlapped among the queried domains.

Limitations

Conversely, the findings of this study must be interpreted considering the study’s limitations. First, recruitment of participants from BPBI-related social media groups potentially created a selection bias in favor of more affected individuals. However, the purpose of the study was to determine the types and scope of impact among affected individuals rather than the prevalence or severity of impact among all individuals who have sustained a BPBI. It is precisely these most substantially affected individuals for whom we must understand the impacts of BPBI to guide treatment. Furthermore, both the quantitative and qualitative data demonstrate a broad diversity of impact, where no domain was reported to be impacted by all participants, and where range of impact varied from positive to very negative. Second, the predominance of female participants implies a selection bias that is consistent with prior research employing social media populations [Citation6,Citation14,Citation42]. However, although significant differences were noted between male and female participants in the proportions of categorical responses to some questions, qualitative data did not reveal consistent sex-based differences in the areas of impact of BPBI in adulthood. Nonetheless, opportunities exist to examine male perspectives more thoroughly on this topic. Additionally, future studies may benefit from using a more precise measurement than dichotomous responses to examine differences between males and females. Third, BPBI severity could not be ascertained to determine correlations between clinical injury severity and its impact on HRQoL in adulthood. However, participant anonymity was deemed particularly important in order to obtain candid responses from a population often at odds with the medical profession [Citation43]. Nonetheless, the use of childhood surgery as a proxy for injury severity demonstrated heterogeneity in the participant sample, where only a minority had undergone childhood surgery despite the majority being in an age group for whom childhood surgery was historically available. Fourth, we did not utilize a strict definition of HRQoL for this study. Recognizing that participants may have different definitions of quality of life, we did not want to influence or constrain the responses or analysis to a predetermined construct and thus we elected to use novel questions rather than a validated survey with questions derived from a predetermined definition of HRQoL. We did not test these questions for reliability and validity among this population because participant anonymity was deemed paramount at the outset of the study. Furthermore, the intent of the study was to identify the HRQoL domains considered relevant by affected individuals to tailor future quantitative studies using validated instruments. Nonetheless, we utilized the WHO-ICF as a broad framework to ensure a comprehensive inquiry into various aspects of HRQoL, and with such a strategy, we gained a broad understanding of participants’ views of the impact of BPBI in adulthood, identifying unexpectedly predominant impacts on pain and emotional and relationship domains.

Conclusions

The findings of this study support two conclusions. First, the scope of impact of BPBI in adulthood is broad covering every aspect of HRQoL. Despite the primary focus of treatment in childhood on improving physical musculoskeletal function, long term pain and psychosocial/emotional concerns should not be overlooked. Second, the nature of impact of BPBI in adulthood varies among individuals within each aspect of HRQoL. This variability underscores the need for patient-centered assessment and care and provides ample opportunity to study modifiable drivers of variable outcomes in this population. Additional knowledge and awareness are needed regarding the long-term impact and care of BPBI, both to provide prognostic guidance and to improve care for this currently incurable condition through the lifespan.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the United Brachial Plexus Network and the Adults with Brachial Plexus Birth Injury Facebook Group and their respective membership for their support of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Foad SL, Mehlman CT, Foad MB, et al. Prognosis following neonatal brachial plexus palsy: an evidence-based review. J Child Orthop. 2009;3(6):459–463.

- Pondaag W, Malessy MJA, van Dijk JG, et al. Natural history of obstetric brachial plexus palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(2):138–144.

- Cornwall R, Kevin L. Brachial plexus birth injury. eighth ed. Green’s operative hand surgery, Vol. 2. Amsterdam: Elsvier, Inc.; 2022. p. 1560–1597.

- Butler L, Mills J, Richard HM, et al. Long-term follow-up of neonatal brachial plexopathy: psychological and physical function in adolescents and young adults. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(6):e364–e368.

- Ploetze K, Goldfarb C, Roberts S, et al. Radiographic and clinical outcomes of the shoulder in long-term follow-up of brachial plexus birth injury. J Hand Surg Am. 2020;45(12):1115–1122.

- Yau CWH, Pizzo E, Prajapati C, et al. Obstetric brachial plexus injuries (OBPIs): health-related quality of life in affected adults and parents. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):212.

- de Heer C, Beckerman H, Groot V. Explaining daily functioning in young adults with obstetric brachial plexus lesion. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(16):1455–1461.

- Menno van der Holst JG, Steenbeek D, Pondaag W, et al. Participation restrictions among adolescents and adults with neonatal brachial plexus palsy: the patient perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(26):3147–3155.

- Akel BS, Öksüz Ç, Oskay D, et al. Health-related quality of life in children with obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(9):2617–2624.

- Medeiros DLd, Agostinho NB, Mochizuki L, et al. Quality of life and upper limb function of children with neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2020;38:e2018304.

- Manske MC, Abarca NE, Letzelter JP, et al. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) scores for children with brachial plexus birth injury. J Pediatr Orthop. 2021;41(3):171–176.

- Chang KW-C, Austin A, Yeaman J, et al. Health-related quality of life components in children with neonatal brachial plexus palsy: a qualitative study. Pm R. 2017;9(4):383–391.

- Squitieri L, Larson BP, Chang KW-C, et al. Medical decision-making among adolescents with neonatal brachial plexus palsy and their families: a qualitative study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(6):880e–887e.

- Partridge C, Edwards S. Obstetric brachial plexus palsy: increasing disability and exacerbation of symptoms with age. Physiother Res Int. 2004;9(4):157–163.

- Bryman A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research. 2006;6(1):97–113.

- Cieza A, Bickenbach J, Chatterji S. The ICF as a conceptual platform to specify and discuss health and health-related concepts. Gesundheitswesen. 2008;70(10):e47–e56.

- Organization, W.H. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva: WHO; 2002.

- Creswell J, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2018.

- FEtters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Acheiving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–2156.

- Plano Clark V, Ivankova N. Mixed methods research: a guide to the field. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2016.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Miles MBH, Michael A. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 1994.

- Morgan DL. Qualitative content analysis: a guide to paths not taken. Qual Health Res. 1993;3(1):112–121.

- Kirkos JM, Kyrkos MJ, Kapetanos GA, et al. Brachial plexus palsy secondary to birth injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(2):231–235.

- Lin X, Wang X. Examining gender differences in people’s information-sharing decisions on social networking sites. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;50:45–56.

- Aktaş D, Eren B, Keniş-Coşkun Ö, et al. Function in unaffected arms of children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018;22(4):610–614.

- Sundholm LK, Eliasson AC, Forssberg H. Obstetric brachial plexus injuries: assessment protocol and functional outcome at age 5 years. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40(1):4–11.

- Hulleberg G, Elvrum A-KG, Brandal M, et al. Outcome in adolescence of brachial plexus birth palsy: 69 individuals re-examined after 10–20 years. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(6):633–640.

- Morrow BT, Harvey I, Ho ES, et al. Long-Term hand function outcomes of the surgical management of complete brachial plexus birth injury. J Hand Surg. 2021;46(7):575–583.

- Zielinski IM, van Delft R, Voorman JM, et al. The effects of modified constraint-induced movement therapy combined with intensive bimanual training in children with brachial plexus birth injury: a retrospective data base study. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(16):2275–2284.

- Auer T, Pinter S, Kovacs N, et al. Does obstetric brachial plexus injury influence speech dominance? Ann Neurol. 2009;65(1):57–66.

- Kirjavainen M, Remes V, Peltonen J, et al. Long-term results of surgery for brachial plexus birth palsy. J Bone Joint Surg. 2007;89(1):18–26.

- Bae DS, Waters PM, Zurakowski D. Correlation of pediatric outcomes data collection instrument with measures of active movement in children with brachial plexus birth palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28(5):584–592.

- Singh AK, Mills J, Bauer AS, et al. Obesity in children with brachial plexus birth palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2015;24(6):541–545.

- Huffman GR, Bagley AM, James MA, et al. Assessment of children with brachial plexus birth palsy using the pediatric outcomes data collection instrument. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):400–404.

- Louden E, Allgier A, Overton M, et al. The impact of pediatric brachial plexus injury on families. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(6):1190–1195.

- Bae DS, Zurakowski D, Avallone N, et al. Sports participation in selected children with brachial plexus birth palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(5):496–503.

- Strömbeck C, Fernell E. Aspects of activities and participation in daily life related to body structure and function in adolescents with obstetrical brachial plexus palsy: a descriptive follow-up study. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(6):740–746.

- Squitieri L, Larson BP, Chang KWC, et al. Understanding quality of life and patient expectations among adolescents with neonatal brachial plexus palsy: a qualitative and quantitative pilot study. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(12):2387–2397. e2.

- Ho ES, Klar K, Klar E, et al. Elbow flexion contractures in brachial plexus birth injury: function and appearance related factors. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(22):2648–2652.

- Escorpizo R. Defining the principles of musculoskeletal disability and rehabilitation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(3):367–375.

- Whitaker C, Stevelink S, Fear N. The use of Facebook in recruiting participants for health research purposes: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(8):e290.

- Domino J, McGovern C, Chang KWC, et al. Lack of physician-patient communication as a key factor associated with malpractice litigation in neonatal brachial plexus palsy. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;13(2):238–242.