Abstract

Purpose

To identify barriers and enablers for access to and participation in rehabilitation for people with LLA in East, South, and Southeast Asian developing countries from the perspective of rehabilitation professionals.

Material and methods

A mixed-method study involving an anonymous cross-sectional screening survey followed by in-depth interviews of rehabilitation professionals in these regions following the COREQ guidelines. Participants were surveyed online using convenience and snowball sampling techniques to inform a purposive heterogenic sample for semi-structured online interviews, between September 2021 to February 2022. Interview transcripts were analysed and thematically coded using the modified Health Care Delivery System Approach (HCDSA) framework.

Results

A total of 201 quantitative survey responses shaped the interview questions and participation of 28 participants from 13 countries for the qualitative investigation. Important factors at the patient level were sex, economics, health issues, language differences, and lack of awareness; at the care team level, peer and/or family support, referrals, and the gender of the professional; at the organizational level, service availability, resources, and quality; and at the environmental level, policies, supports, and physical and/or social accessibility.

Conclusions

Identified interlinked factors at multiple levels of the HCDSA underpin the need for a systems approach to develop and address regional rehabilitation service provision but requires contextually adapted policy.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Amputation rehabilitation practices need improvements in the developing Asian region including evaluation and redesign of, and processes and policies by, policy makers with increased support for those with lower limb amputation.

The consistent factors identified in these regions as negatively impacting rehabilitation services suggest opportunities to collaborate and design common mitigation approaches between rehabilitation providers across countries.

Unique local factors impacting rehabilitation in different countries suggest the necessity for customization in consultation with rehabilitation practitioners rather than the adoption of generic charitable models by external agencies.

Rehabilitation professionals and others responsible for rehabilitation policy and practice should systematically target factors impacting rehabilitation outcomes for improvements at all levels within the health care systems.

Introduction

The life-changing event of Lower Limb Amputation (LLA) impacts most domains of an individual’s life and their families [Citation1,Citation2]. Following LLA social reintegration requires comprehensive interventions involving a range of stakeholders [Citation1,Citation3,Citation4]. The bio-psychosocial model describes disability as the outcome of interactions between the individual, their functionality, and their environment [Citation5], emphasizing access to timely and appropriate rehabilitation for re-integration involving all levels of the healthcare system [Citation6]. The bio-psychosocial model underpins the Health Care Delivery System Approach (HCDSA) which describes the importance of evaluating the efficacy of health services at four different systems levels to strategically identify appropriate rehabilitation service improvement requirements [Citation7]. The first of the four nested levels comprises individual or patient factors as the focus of the service; the next level is the care team (clinicians, peer, and family) factors; the third, the organisational (e.g., hospital, rehabilitation centre, etc.) factors including their infrastructure and resources; and finally the environmental factors (sociocultural, political, economic, physical, regulatory, financial, etc.) impacting the whole system [Citation6,Citation7].

A previous scoping review of rehabilitation access and participation in East, South, and Southeast Asian developing countries [Citation8,Citation9] through the HCDSA framework identified influences at all system levels [Citation6]. Commonly identified barriers included gaps in referral, awareness, and availability of services, and the centralised location of rehabilitation centres [Citation10–13]. Most previous research has identified barriers and enablers to rehabilitation from the perspective of people with LLA – the service users [Citation14]. While these service users are key informants, as consumers they have a limited understanding of the broader health system factors [Citation13]. Rehabilitation professionals providing services for those with an LLA are in a stronger position to identify and address gaps across all levels of healthcare delivery systems that impact rehabilitation access and services [Citation10,Citation15–17]. The limited research exploring the views of rehabilitation professionals in this region has focused on professional practice issues rather than comprehensively investigating their understanding of rehabilitation access and participation [Citation13,Citation14].

Establishing a comprehensive view of rehabilitation access and participation from service delivery stakeholders requires a systematic approach [Citation14,Citation18]. Rehabilitation professionals (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, prosthetist & orthotists (P&O), vocational trainers, physician, etc.) working within the health care delivery system are key information sources as they interact at all levels of HCDSA to provide care [Citation7]. Their interactions with patients, developing and delivering care plans [Citation19], and working with other care team members, can inform development initiatives [Citation20]. Also, as important organizational stakeholders, rehabilitation professionals can provide information on the availability of services, capacities, and organizational limitations and strengths [Citation21] and insights into a broad range of factors including barriers to be addressed to better accommodate the reintegration of people with LLA into their pre-LLA life [Citation7]. Factors relevant to community reintegration include country or regional support policies, physical and social environmental impacts, and rehabilitation outcomes including social and financial outcomes [Citation18]. The use of a participative approach involving rehabilitation professionals promoted by the World Health Organization’s Systematic Assessment of Rehabilitation Situation [Citation18] and the HCDSA framework [Citation7] provides opportunity to develop a comprehensive understanding of relevant factors.

Rehabilitation professionals, as important stakeholders in rehabilitation delivery, have the potential to provide valuable evidence about barriers and enablers relating to rehabilitation access and participation towards improving life after LLA [Citation22]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify the barriers and enablers for first access to and then continuing participation in rehabilitation for people with LLA in East, South, and Southeast Asian developing countries from the perspective of rehabilitation professionals.

Method

Study design

This mixed-method study involved a cross-sectional screening survey followed by in-depth interviews. The survey aimed to understand the nature and distribution of current rehabilitation services available in East, South, and Southeast Asian developing countries, and inform purposive sampling of interview participants for maximum heterogeneity. The qualitative semi-structured interviews were used to gain insights from the rehabilitation professionals about barriers and enablers of access to and participation in rehabilitation. This study followed Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews reporting [Citation23]. This paper reports part of a mixed-method study with multiple outcomes presented in different papers focusing on key factors related to rehabilitation. This paper presents the findings from the qualitative interviews which were informed by an initial quantitative screening survey related to rehabilitation access and participation in developing countries in this region. Sections of the methodology and a small component of the results, both relating to details about the participants are also reported elsewhere [Citation24].

Population

The participant population included rehabilitation professionals (P&O, Physiotherapist, Occupational Therapist, Rehabilitation Counsellor, Vocational trainers, etc.) involved in rehabilitation of people with LLA in East, South, and Southeast Asian developing countries. The countries of interest were selected by combining the Asian Development Bank categorisation of Asian developing countries (2019) into five regions (Central Asia, East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and The Pacific [Citation25], and the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2018) list of 25 Asian developing countries [Citation9] in the Central, East, South, and Southeast Asia regions. These are Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China (People’s Republic of), India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Korea (Democratic People’s Republic of), Kyrgyzstan, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor Leste, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam.

Research team

The study was conducted by three researchers. Md Shapin Ibne Sayeed, a male researcher, with a background in physiotherapy in prosthetic rehabilitation in an international organization working in limited-resource countries. Along with his work experience in that organization, he has had the opportunity to develop an international rehabilitation perspective for people with amputation and previous research work in the field. Dr. Jodi Oakman and Dr. Rwth Stuckey, are both experienced women allied-health practitioners and occupational health researchers with extensive experience in rehabilitation, ergonomics, and human factors.

Anonymous screening survey

Convenience and snowball sampling techniques were used to recruit survey respondents. Participants were invited through various media including via professional organizations (global/local) e.g., International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics, World Physiotherapy, World Federation of Occupational Therapists, Global Cooperation on Assistive Technology; and, by email to relevant researchers identified from published journal articles. Additionally, around 300 email invitations were sent to local/international professional organizations, Non-government Organizations (NGOs – ICRC, HI, Exceed Worldwide, etc.), and individuals working with LLA. A professional social media page (Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter) was created inviting survey participation and shared to social media pages of rehabilitation professional organizations. Snowball recruitment included sharing social media posts to and inviting survey participants to share the survey invitation with colleagues.

Eligibility criteria were to be 18 years or older; have at least one year of work experience with people with LLA in East, South, and Southeast Asian developing countries; be currently working as a rehabilitation professional; be able to answer questions in English.

The anonymous survey questionnaire was based on the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework [Citation26] and the WHO rehabilitation service assessment template for rehabilitation information collection (TRIC) [Citation18]. The questionnaire was administered online through the QuestionPro® online survey platform [Citation27]. (See Supplementary Appendix: 1 for the survey questions).

Qualitative interview

Interview participants were drawn from survey respondents who indicated an interest in participating in an online interview. To maximise heterogeneity, a purposive sample was selected which aimed for representation of (if available) country, gender, and professional roles. The selection aimed to include varied views by including at least 2–3 participants of each (country/sex/profession) if available. Selected participants were contacted via email for informed consent.

The interview schedule, used semi-structured questions based on the survey responses, RE-AIM framework [Citation26], and TRIC [Citation18] (see Supplementary Appendix 2 for the Semi-structured Interview questions). Interviews were conducted from September 2021–February 2022 using Zoom© or Teams© platforms and recorded. Recorded interview files were securely stored under pseudonyms. All interviews (n = 28) were conducted by the first author (Shapin); with 26 co-conducted by the other authors, 25 with Rwth and one with Jodi.

For data analysis, the interviews were transcribed using the transcription platform Otter [Citation28], carefully checked and corrected by the first author for a draft transcript. Draft transcripts were re-checked by the other author present during the interview. Interviewees were provided with their own individual transcript via email to enable them to check the transcription and add or delete any data they wished to and asked to return it to the researcher within two weeks. Seventeen out of twenty-eight participants reviewed and returned their transcript, but the rest did not respond to the request within two weeks, or to the two reminder emails sent after that time. The final transcripts were thematically analysed using Braun and Clarke’s proposed (2006), and updated (2019) steps for reflexive thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews [Citation29] including the process of reflecting on the philosophical and theoretical assumptions in the six-recursive-steps [Citation30], to organize outcome based on the HCDSA framework [Citation7]:

Step 1- all authors familiarized themselves with the data reading the transcriptions multiple times and noting primary ideas based on the 4 different levels of the HCDSA micro-system [Citation7].

Step 2- all authors developed a coding framework with a clear and agreed coding process to promote the reflective outcome from the interviews for readability and reliability [Citation31]. Coding was undertaken using the NVivo 20 software (QSR International©). All three authors independently coded the same 2 transcripts, then two authors independently coded the same 12 more transcripts. After comparing to check consistency and validity between the coders, the remaining 14 transcripts were coded using the agreed codes by one author (Shapin).

Step 3- potential primary themes were created based on the modified HCDSA framework [Citation6].

Step 4- sub-themes were created by checking the thematic maps, code extracts and matching across the entire data set.

Step 5- themes were iteratively defined and named with clear definitions, and relevant factors identified and extracted [Citation26];

Step 6: Results were drawn from extracts relating back to the modified HCDSA levels [Citation6] with themes and key factors. The modified version of the framework has 11 nested themes used to provide a detailed understanding and comparability of the data outcomes [Citation6]. Quotes used in the results are identified by country rather than a participant to protect participant identities, particularly within their country (See ).

Table 1. Theme: Client/Patient- Access and participation factors at Level-1 of HCDSA, country and key outcomes.

Table 2. Theme: Care Team – Access and participation factors at Level-2 of HCDSA, country and key outcomes.

Table 3. Theme: Organization – Access and participation factors at Level-3, level of HCDSA, country and key outcomes.

Table 4. Theme: Environment – Access and participation factors at Level-4 of HCDSA, country and key outcomes.

Ethical consideration

Ethics approval (HEC21196) was provided by the La Trobe University- Melbourne Human Ethics Committee.

Results

Survey participant demographics

A total of 201 survey responses were received with 106 surveys fully completed. Participants from 14 (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam) of the 25 targeted countries responded to the anonymous survey. The mean age was 34.2 ± 9.1 year with a range of 21–71 years, more men (61%, n = 97) than women (38.4%, n = 61) responded. Participants’ education ranged from non-certified to Ph.D. level, most having at least a bachelor’s or higher level of education (84.3%, n = 134). Prosthetists and orthotists (52.8%; n = 84), and physiotherapists (36.5%; n = 58) dominated participants’ professions.

Interview participant demographics

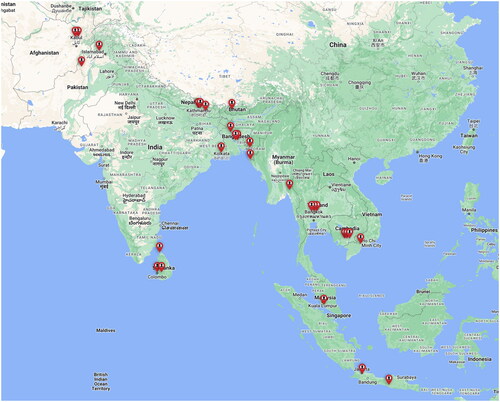

The 28 interview participants were from 13 countries (see ), with recorded interviews providing over 30 hours of data.

Table 5. Interview participants demographic information (N = 28).

All but three participants were representing their country of nationality. About half (n = 13) were experienced in working with LLA in more than one country ranging from 2–5 countries. The majority (n = 19) had travel from their own to a different country for their entry level professional education. Three had diploma-level education, while most had bachelor’s or higher-level education. As with the survey participants, their rehabilitation roles were dominated by P&O (n = 19) and physiotherapists (Citation7). One worked in vocational rehabilitation, and another was a physical medicine doctor. Mean years of rehabilitation work experience was 16.0 ± 9.9 years with a range of 3–47 years. Most reported working in national or international NGOs (n = 16). Five worked in government or semi-government organizations, and the remainder in private practice (n = 4) or government university-attached hospitals (n = 3). Participants (n = 17) reported their experience from working in urban/city rehabilitation settings in their country. Participants experiences were drawn from work across 13 countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam (see ); from a variety of locations.

Figure 1. Map of participant locations (Created using Google My Maps: https://www.google.com.au/maps/about/mymaps/).

The interview questions enabled a deep understanding of factors related to rehabilitation access and participation. Participants worked in a range of countries with varied experiences of geography, conflict, social, religious, and economic circumstances, and contributed different professional and organizational perspectives.

Reported socio-demographic characteristics of the LLA population

Participants were asked to describe the demographics of their country’s overall LLA population to understand local access and participation factors. Demographics varied between countries and sometimes between participants within the same country, reflecting their different locations and organizational focus (see ). summarizes both common and different experiences in each country. The primary cause of amputation was described as traumatic LLA from road/industrial/work accidents. The second most common cause was dysvascular with Diabetes Mellitus and Peripheral Artery Disease affecting the middle to older age population. War related injuries leading to amputation were common for countries with current or recent conflict/war e.g., Afghanistan, and Pakistan. In both traumatic and war-related cases the younger (18–50 years) population group were primarily affected.

Table 6. Reported socio-demographic characteristics of LLA population in each country.

Regardless of cause or age, participants described the lower compared to higher socio-economic group as more impacted.

They are actually less educated, economically lower level. I mean the ones who are working mostly in daily labour jobs where physical effort is needed to continue, and (they are) the primary earner of the family. (Bangladesh)

Themes and sub-themes

The 4 themes and 8 sub-themes extracted from the data described factors related to access to and participation in rehabilitation and organized within the four levels of the HCDSA framework. The HCDSA was proposed as a framework by Ferlie and Shortell (2001) to explain the healthcare delivery system model and the structural dynamics of rehabilitation access and participation between patients, the care team, the organization, and the environment [Citation32]. All factors identified at each HCDSA level for each theme and sub-theme are presented in detail in , with identification of which country(s) noted for each theme. The themes are “Client/patient” (Sub-themes: “individual patient characteristics” and “individual patient- skills & resources”), “Care Team” (Sub-themes: “team characteristics and functions” and “external influences”), “Organization” (Sub-themes: “service challenges” and “service delivery”) and “Environment” (Sub-themes: “economic factors” and “physical, political, social and cultural factors”). provide additional information: the countries in which theme was identified; examples of each sub-theme demonstrating when relevant to either or both, access and participation, and, in which countries these access or participation issues were identified.

This section presents a summary of the most frequently identified factors across the countries within the themes and sub-themes.

Theme: patient factors (HCDSA level- 1)

Patient-related factors consider the demographic characteristics, health issues, and individual/personal factors including economic status which impact rehabilitation access and participation (see for details).

Gender impacts both rehabilitation access and participation as many women are not allowed to leave their home without a man from their family for cultural/religious reasons and require a man (usually husband/brother) to accompany them to receive rehabilitation services.

Children depend on their families to take them to the rehabilitation centre. They usually need their mother with them but then because the mother has restrictions to go out of the house alone, they also need another male family member. (Afghanistan)

Participants identified the experience of women with LLA as having unique barriers to rehabilitation access and participation in all countries except Thailand, including a lack of prioritization within the family for their rehabilitation access or participation.

Women have many obstacles or challenges, like education and also independence. Sometimes their fathers, brothers, or husbands are busy. And they ignore to bring this woman with a disability to rehabilitation centres. (Afghanistan)

Amputation was primarily reported in the lower socio-economic groups, and the inability to afford rehabilitation or related costs leads to accepting disability without accessing rehabilitation.

We understand their position, their ability and their financial limitations. Usually, they do jobs with lower socio-economic status, very poor earning and living, so they can’t afford rehabilitation. (Bangladesh)

Some struggle following initial access to continue to participate due to reduced supports from organizations for follow-up. For some, this is compounded by the need to spend money on rehabilitation and the loss of income while attending.

They lost their work and income, which they need to help in the village to support the family. So, in some cases they don’t want to come to get the advice, service, even if they need help, they have broken their device, they say I will just use this. (Cambodia).

In contrast, for some being visibly disabled resulted in earning more money through begging compared to other work, which impacted attendance at rehabilitation.

Most of the poor people, they are begging in the streets, if they use prosthesis, they don’t get the money from people, or help from the people, but without the prosthesis they get more money. (Bangladesh)

Health-related “complications” impacted both access and participation. Traumatically amputated patients suffer more because of difficulty accepting their disability compounded by a lack of mental health support which is further exacerbated by delays in rehabilitation access. Delayed rehabilitation access also results in contractures or stump deformities creating difficulties for prosthetic fitting and/or long pre-prosthetic management. Difficulties with prosthetic fitting undermined outcomes with longer rehabilitation time and costs. Other related factors reported were comorbidities requiring urgent management, phantom limb pain and congenital limb deficiencies with multi-disability affecting participation.

As they don’t do the proper stump care or pre-prosthetic management is missing always, we see stump complications like contracture, oedema and bulbous stump. (Sri Lanka).

For those mostly young and active people with amputations caused by trauma, this sudden life-changing event can be even more challenging to accept, and they hide themselves without accessing rehabilitation or continuing participation.

Most of the patients coming here with amputations are in a shock or traumatized. Sometimes the patient does not want to live anymore, because losing one or two legs, or one hand, the life is gone, so no need to live anymore, or even their family ignored them. (Afghanistan)

Those with LLA who were the primary income source for their family often had to prioritise work over rehabilitation. For others the decision to access rehabilitation is a dilemma because they and/or their family are uncertain of rehabilitation outcomes.

Another problem is [the] patient is not sure what he will do after receiving the prosthesis. They are confused whether they will be able to return to work. (Bangladesh)

Even after access, work remains a priority over rehabilitation, with participation in follow-up only when they experience a serious problem with their prosthesis.

The priority for the family and their life, they can move with a crutch without a prosthetic limb… I had people who were not really willing to have the prosthesis and then they feel like they will keep prosthesis for some festive to use. (Nepal)

Initial effective communication between the patient, their family, and the rehabilitation professional were identified as important, with some participants noting they were able to manage language diversity in their setting. For others, language differences between patients and/or their family and those providing services was a barrier to access and participation.

Language diversity is a challenge for people with disability in Afghanistan. Some provinces people are not speaking in the official language of Afghanistan and some of our technicians don’t know their (patients) local language. If they need to provide some advice for patients, it’s difficult for them to treat them. (Afghanistan)

Participants highlighted not having official translation facilities or supports as a barrier, and commonly tried to manage language issues unofficially, using family members or other centre staff who can speak the required language.

We try to find some interpreter, someone who knows a different language than the Nepali language…. Otherwise, we just use kind of sign language to understand. (Nepal)

The patients’ “culture and religion” was identified as contributing to barriers across some countries. The shortage of professional women in their countries was an issue for Muslim women who don’t want to be seen by professional men.

Muslims, when they bring their kids, especially adult females, they prefer not to be seen by the men. (Sri Lanka)

Participants from Cambodia and Nepal identified Buddhist beliefs in “karma” as a barrier – those who lost a limb hid themselves at home, not accessing rehabilitation.

Buddhist, we believe in karma, the action in the past, that bring them to what they are now in life. They think that to get amputation, they have done something bad in their past. (Cambodia)

Lack of information about service availability impacts both access and participation. Lack of rehabilitation awareness or information from acute-care services about service provision limits access to rehabilitation.

There is still not much awareness about the physical rehabilitation service. How they can access the service, how the services can help them to retain mobility, social activities, or other activities. So, this is the major barrier for people in Afghanistan. (Afghanistan)

An important enabler for patients was learning about rehabilitation through social media platforms. Another enabling factor identified was the value of previous service users of rehabilitation services, as a useful source of information to new people with LLA.

Most of the patients told me that ‘I had amputation for five years, I was unaware, I didn’t see, I didn’t know about rehabilitation centre. Now, I have seen that in social media, my friend told me that there is a rehabilitation centre. (Pakistan)

Regular rehabilitation follow-up particularly for any issues with prosthesis, was limited by several factors. Patients were reported to undertake “prosthetic improvisation” themselves skipping follow-up. These improvisations often result in total prosthesis damage, therefore requiring replacement- a further financial, resources, and time burden for the patient and/or the service support systems.

They do the changes like somewhere cutting the plastic. So, they make the changes even though we told them to come to the rehabilitation centre if they experience any problem. Maybe at that time the problem is such that minor changes just needed. But now we must change the whole prosthesis. (Pakistan)

Theme: the care team (HCDSA level- 2)

Care team-related factors relate to the involvement of family and friends, the acute care team, and the rehabilitation care team and how these stakeholders’ impact rehabilitation access and participation (see for theme and sub-theme details).

The concept of peer-group support facilitating rehabilitation participation was identified as important. Some participants reported having occasional disability programs providing some form of peer support, with some rehabilitation organizations deliberately recruiting people with a disability at their centre, thereby demonstrating examples of successful outcomes.

It improves motivation and encourages our clients but there is no official peer group support, in my organization. Prosthetic rehabilitated patients are working in different sections, like the reception or in the stores. Patients can see them working and talk to them to get support. (Bangladesh)

Participants noted the importance of involving family as an integral part of the rehabilitation process for both rehabilitation access and participation, particularly for the support of women or children, dependent on men from their family to take them to the rehabilitation centre.

The other barrier is family cooperation. Mostly, patients have no cooperation of their own family, when a patient is disabled, patient lives in their own place and they cannot give them help for rehabilitation – majority of patients have no family support for rehabilitation. (Pakistan)

The referral was one of the biggest challenges identified for access, with a lack of rehabilitation professionals or services involved in acute patient care. Participants identified that in many cases patients are sent home from acute care without any referral for rehabilitation for many reasons including no rehabilitation awareness by surgeons or acute care professionals; no/poor referral systems for rehabilitation; the complexity of health system referral mechanisms; lack of patient follow up for rehabilitation wait lists; and doctors delaying referrals.

The rehabilitation system in Sri Lanka is not well developed, and some surgeons or doctors from the hospital don’t care about prosthetic management. So, some people after amputation go home without knowing there is a centre to have the prosthetic rehabilitation. (Sri Lanka)

Participants described patients’ referral sources including previous rehabilitation patients; rehabilitation centres attached to hospitals; other rehabilitation professionals; regional hospitals without rehabilitation services; and other NGOs.

… the hospitals are not much aware of rehabilitation services. So far as I know, the amputee person, they get the message from peer to peer, the one who have got prosthesis from our centre spread the information. (Myanmar)

Participants from two countries identified improved referrals following awareness programs undertaken through their professional organizations.

Surgical considerations by the acute care team impacted both access and participation, particularly surgeons or acute-care professionals not considering ideal stumps for a prosthesis (with often a focus on only saving lives.

Patients having unsuitable stump shape and size, limits participation in rehabilitation.

They cut the stump too short or sometime the scar is immobile or have complications for the prosthesis. I have seen the bones are very prominent. They didn’t cover the bones properly, bones are very sharp, neuroma and then the surgical immobile scar. And then I have seen patients, they have like scars on their patella tendon area, difficult for prosthetic fitting. (Malaysia)

Professional challenges related to working for professions involved in rehabilitation impact rehabilitation service in all countries. Most notably, the lack of rehabilitation professions/professionals and limited services.

In fact, we do not have any occupational therapists in the country. This subject taught to physiotherapist, and the physiotherapist must do the occupational jobs in Afghanistan. (Afghanistan)

Participants also mentioned challenges for professional education or higher education, including availability and admission requirements, with participants undertaking travel to other countries for their education a common finding. Professionals leaving their roles because of multiple challenges to work in their countries was noted. Additionally, the lack of professional and regulatory bodies has led to malpractice issues by non-certified professionals, creating negative societal attitude towards the professions.

We don’t have regulatory body, so besides our organization, there are some NGOs and the private sector giving the service by some people who do not have the training. (Bangladesh)

Professionals working in rural areas are usually not working in rehabilitation teams; and many prefer to work in city areas further challenging the availability of regional services.

And then mostly they want to stay in Bangkok. They don’t want to go to rural areas. (Thailand)

Participants from Sri Lanka and Bhutan noted their government provides scholarships to students to study in rehabilitation professions, with agreements to later work in government rehabilitation centres for a fixed period helping to improve rehabilitation access and participation.

After 2015 the government, when they recruit students for P&O, they need to sign a bond to at least work 10 years for Sri Lankan government. And they get student allowance during these three years of the study period. (Sri Lanka)

Despite the regional need for professional women, participants identified a range of barriers to increasing their numbers including rehabilitation work considered too heavy/dangerous for women; negative societal attitudes towards womens’ work roles; and professional women leaving the profession after marriage or children.

Many professional women who have overcome initial barriers do not want to, or are not allowed to, work away from their home city creating further issues with service provision in regional or remote areas.

Due to security, safety they stay with their family but if they have to come to the regional area, their family is not allowing them. So, that’s why they are not coming in the regional area. (Bangladesh)

Participants noted the need for a range of professionals in the team to achieve successful rehabilitation goals. Challenges identified included no clear understanding of the role of different rehabilitation professionals, and some professionals working in roles other than their own professional role.

In some settings the rehabilitation medicine specialist is the sole decision maker and utilises a clinical rather than taking a multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach, creating issues affecting participation. In 5 countries orthopaedic workshops prosthesis are provided by P&Os, usually privately, without any other professional input.

I made the prosthesis and then deliver to the patient, get the initial training, doctor checkout my case. And after that I never see them, how the patient gets the training. We don’t have collaboration together. (Malaysia)

Interestingly, while most participants mentioned working in an MDT, these teams usually consisted only of physiotherapists and P&Os.

There is a multidisciplinary team working together for the rehabilitation of the people with LLA. There is a physio, there is a P&O. (Bangladesh)

However, while most teams are limited, these professionals report co-operation, working well together to provide better outcomes.

In the rehab centre P&O work with physiotherapy. So important to carry out the responsibility to collaborate and communicate to each other. There’s no conflict between these professions. (Cambodia)

Participants advised that in some cases support could be organised from other rehabilitation professionals, including from occupational therapists, physicians, surgeons, nurses and rehabilitation medicine specialists. Only two countries identified having a wide range of rehabilitation team members available when needed, in a capital city Pakistani government rehabilitation hospital and a Sri Lankan army rehabilitation centre. In addition to the limited range of professionals, conflict between the different professions was also impacted teamwork in some countries.

But there is huge conflict between all these professionals when they work in one place. Who is better than others, huge conflicts. (India)

Theme: organization (HCDSA level- 3)

Sub themes at the Organization level are service-related factors including available service facilities and delivery strategies which impact rehabilitation access and participation (see for details).

Availability and location were identified as major rehabilitation access and participation barriers, with the need to travel long distances to services and rehabilitation centre locations primarily in big cities, creating difficulty for those in remote locations.

The usual time that it takes for people to come from another region to the centre, like from the extreme, I mean east, they take three days. In between, they have to stay in a hotel. (Bhutan)

Patient supports within the organizations impact access and participation in all countries except Malaysia. Participants identified multiple systems of rehabilitation funding within countries and centres, and different service models e.g., private, government, NGO etc. Supports varied with some countries providing free prostheses, while others require payment from patients.

Some organizations provide free or subsidized additional therapeutic services including gait training. Apart from rehabilitation, funding varies for other related costs (transportation, food, accommodation, etc.), from no supports available in some settings to services provided to outpatients.

A further difficulty for some organizations is reliance on supports from short-term funded projects and/or dependency on the availability of funding or donors compounded by the bureaucratic systems to access supports.

At first, we used to provide accommodation for those who are from far area, almost 100- or 200-kilometer distance from our rehabilitation centre, and also, we give food free of cost. But now, due to some issues and funding issues, it has been stopped. (Pakistan)

Support strategies identified included: transport or reimbursing transport expenses, accommodation during rehabilitation, and food or allowances for expenses. Importantly, some organizations also provided support for an accompanying family member to improve rehabilitation access and participation.

Specially ICRC and there is HI or Swedish are working free of charge, and they are admitting the patients if needed. They give food three times (a day) free of charge, provide laundries and even when they’re with relatives, they also get everything is free of charge. (Afghanistan)

Rehabilitation for LLA in these countries is a relatively new service delivered through three different model identified by the participants. Services started in response to natural disasters or conflicts/wars, by national and international NGOs, and continuing was one model; the government provided or supported rehabilitation another, and private organizations providing services the other.

Northern part of Sri Lanka had war for the three decades, and there were many war-related amputees. But there were no prosthetic and orthotics centre. So, then the Handicap International took the initiative to establish the prosthetics and orthotics centre. (Sri Lanka)

Participants discussed issues with funding models including NGOs providing support based on their own funding priorities for that country; charitable service models lacking sustainability; government services limited to tertiary level hospitals; service delivery through social welfare instead of health services, and dependency on NGOs for service when no government rehabilitation is available. Among the different funding challenges, participants mentioned that they have community-based rehabilitation or mobile camps supporting rehabilitation in their service areas, which are dependent on funding.

… we go to a village for outreach or social mobilizing, gather data from 10 to 20 patients in different places. Then when there are 70-80 patients on the list, then we go for approval, for other charities, when approval is come then we go for the camps. (Pakistan)

An interesting initiative described in Myanmar is a model supporting local prosthetic repairs by training volunteers in locations distant from the rehabilitation centre.

We have a mobile prosthetic repairing program and repairman network. We train them, sometime the person could be our service user or a person who is interested in volunteer work. The service information spreads among them. (Myanmar)

Participants from Bangladesh and Cambodia mentioned poor acute-care services could create negative attitudes for patients towards accessing rehabilitation. In contrast, good quality services, help to promote the importance of attending rehabilitation.

Successful rehabilitation making a positive impact on the people in community like a ripple effect. After observing rehabilitation changing life of a person with LLA, they are referring or spreading information to other patients. (Bangladesh)

Participants identified that government and/or NGOs provide very basic prosthetic technologies, unsuitable for the needs of people with LLA or professionals’ requirements.

The components or materials that we are providing doesn’t meet some of the user needs. Looking at the components sometimes they get completely demotivated. We should use technology/components based on the patient need, but the thing is I decide based on availability. (Bangladesh)

In some countries, corruption related to service provision impacts rehabilitation access and participation.

When they (surgeons) do amputation, they get money from the patient, and when they refer to a private prosthetic clinic, they get paid. Private clinics bribe the doctor to get patient. (India)

Participants identified a range of participation barriers including transfer of the service delivery model from NGOs to the government with subsequent service deterioration or closure; poor quality government rehabilitation centre services; poor prosthetic alignment causing component damage, and provision of the ready-made prosthesis without customization.

Government sector, the quality is an issue and if the people are not satisfied the news go word-to-mouth ‘Oh, I went there, it’s very painful. Don’t go there. It’s not worth it’. (India)

Participants described multiple strategies in place for improving access and participation including an MDT approach; family involvement in rehabilitation for women and children; recruiting staff for gender balance; women caring for women; collaboration among organizations; and rehabilitation linked to acute care hospitals.

We have a department completely working for the women and the babies, all these staff are women, all even securities guards. Even the cleaners. And all of them are women with disabilities. (Afghanistan)

Other strategies for improved participation are ensuring informed consent regarding gender issues, arranging follow-up during discharge, and contacting patients before the follow-up to prepare a work plan for them on arrival.

Theme: environment (HCDSA level- 4)

Environment-related factors including economic, physical, and social environmental and political factors impact rehabilitation access and participation (see for details).

The cost of care impacts rehabilitation in all countries except Malaysia. It includes high costs of private care, government and NGOs services, with any subsidised service charges undermined by unsuitable criteria for access.

Showing the poor ID card patient can get free health services. But challenge is they do assessment based on the household and sometime people get an amputation but are not identified as a poor family. He is poor, but the household doesn’t have the ‘ID poor’ and can’t get the free service. (Cambodia)

Rehabilitation related costs were described as more than just the cost of rehabilitation.

We also provide the person who cannot afford for travelling, we are reimbursing them. But the main barriers are finance, that they do not have initial funds to cover their travelling. (Myanmar)

The financial support mechanisms impacting rehabilitation access and participation, including the challenge for patients to cover their rehabilitation costs, fully or partially.

Patients are not able to pay the full costs of the prosthesis. So, they are sourcing different ways. They are receiving some support from social welfare fund, some contributions from their relative or friend or from rich person in his society who could help. (Bangladesh)

Societal attitudes, such as negative community attitudes, particularly in rural areas, is a major challenge for people with LLA accessing rehabilitation, identified in all countries except Malaysia and India.

In Pakistan, people mostly consider disabled people not a normal people. So, that is the main thing from the community and overall, from the government side. (Pakistan)

Charitable or sympathetic behaviours from others making people with LLA feel less valued or capable, was reported as further restricting rehabilitation access or participation.

… the people in society, they mostly have sympathetic support for people with disability. This will not help as these changes the mind of people with disability. They have sympathetic support. It is not encouraging. (Afghanistan)

On a positive note, other participants felt attitudes or acceptability within their community for people with a disability is improving through awareness programs run by different organizations, and people with LLA are now well accepted within their regions.

Before, 15 years ago community attitude was a big problem but nowadays, NGOs are doing awareness for the person with disabilities. Community people accepts. (Nepal)

Difficulties for people with LLA moving around their community because of lack of public or other transport, mountainous terrain and/or weather factors, severe heat, rain, floods in their local area were also identified as major challenges.

Some places they could only travel in summer, not in the rainy season, because they live far away in the country, or mountainous area. travelling is not possible, because in the monsoon season there are lots of rain, so they cannot cross the river. (Myanmar)

Participants from war-affected countries described the increasing number of patients with LLA due to conflict or war in their country impacting service demand and availability.

Rehabilitation service is not sufficient because the number of patients in need of rehabilitation day by day is increasing because of civil war, and many congenital diseases or indirect war victims. (Afghanistan)

Weak policy or an absence of policy to support people with LLA, and/or exclusion of rehabilitation services from national health systems, and provision of services through the social welfare departments, undermined referrals and service availability.

The lack of the integration of the rehabilitation sector into the health sector is the main gap to get the immediate rehabilitation. (Cambodia)

Participants also noted that despite there being policies, actual implementation in their country was limited or the systems were overly bureaucratic to access support services.

We have ratified the UNCRPD convention and then in 2016, we have special act for people with disabilities. But implementation of the law is always the difficult part. We still need the act properly implemented. (Indonesia)

However, participants from Bhutan, Myanmar and Sri Lanka noted government rehabilitation policy is supporting people with LLA to some extent.

Governments treating rehabilitation as charity and accepting charitable supports from other governments or organizations for political advantage was identified as an issue in some countries. Frequently these charitable supports do not match the contextual need of the country and are for only short duration, sometimes increasing patient expectations and further limiting participation. rehabilitation.

I have seen many donations of second-hand devices from USA, Japan and other NGOs, I saw a lot of rubbish. I had to discard the useless components…. For example, some donated silicon liners for the patients. But as this is not a regular supply we had to say, ‘next time you cannot get this, only this time. (Thailand)

Participants discussed how professional bodies in the country are working to develop rehabilitation professional supports for physiotherapists and P&Os. These initiatives aim to standardise services within countries and develop awareness programs to improve rehabilitation access and participation.

Government regulations for the control and protection of professional titles to ensure quality care for the people with LLA were limited. Regulatory bodies were not available in some countries for Physiotherapists and for P&Os in others.

Malpractice also has a negative impact on the professions.

Malpractice is all around the country. We get complaints from the consumers authority, some people assessed, charged big money, but there is no outcome of the prosthesis. (Sri Lanka)

Discussion

This study explored the barriers and enablers for access to and participation in rehabilitation for people with LLA in East, South, and Southeast Asian developing countries, identifying issues throughout the region related to individual, community, rehabilitation design and delivery, and physical, cultural, and environmental factors. For those with LLA, issues limiting both access and participation included lack of awareness of rehabilitation services; poverty; multiple health issues; speaking a different language to service providers, and being a woman, Gender also impacted at the care-team level, with limited support for women accessing rehabilitation, as well as a general lack of rehabilitation professionals, and, again, particularly women. Service availability, most notably in rural and remote areas combined with limited skilled personnel, financial and other service-related resources impacted at the organisational level of the HCDSA, while, the lack of, or poor implementation of supportive policies, combined with physical and/or social and cultural accessibility, were identified as challenges at the broader country environmental level.

The use of interviews with the service providers enabled the capture of a rich and unique data set. The interview participants experience captured was from varied geographical, cultural, and religious contexts and locations. However, many inter-related factors consistent with findings in other studies in more economically developed countries were identified within the four levels of HCDSA consistently across the thirteen developing Asian countries [Citation33]. The identified factors impact both rehabilitation access and participation for people with LLA, which in most cases was described as primarily focused on improving mobility, rather than providing a broader MDT approach [Citation6,Citation34]. Studies from developed countries have identified that effective rehabilitation outcomes are achieved through MDT providing services addressing return to life with consideration of all physical and psycho-social dimensions [Citation33].

The rehabilitation professionals provided rich, critical firsthand experiences of working in a variety of clinical and organizational settings within each of the 13 countries. Their broad insights at all four levels of the HCDSA is shaped by their intimate relationships with patients while working within their care team within their organization in their particular country’s sociocultural environment, enabling understanding of the health services across whole systems [Citation10,Citation15–17]. The collection of information from rehabilitation professional as primary informants rather than using patients or using rehabilitation providers as a patient proxy is relatively uncommon, and this novel method helped to open the door to a much greater systemic understanding of the experience of rehabilitation of those with LLA in this region [Citation13,Citation14].

With the advantage of having a shared understanding of both the patient and rehabilitation professional experience, this study identified particular challenges at the patient level of the HCDSA framework [Citation35]. They identified significant rehabilitation access and participation barriers for women with LLA, unique to this region compared to developed countries and shaped by educational status and other sociocultural and religious beliefs [Citation36–39]. The prevalence of amputation in less educated young men, frequently the principal family earners from lower socio-economic group results in significant barriers to rehabilitation in an environment of limited supports and affordable rehabilitation compared to that in more developed countries [Citation40,Citation41]. Factors such as health complications; speaking different languages to service providers, and/or lack awareness about services add further difficulties to accessing rehabilitation. These characteristics have been identified as key limiting factors for rehabilitation access and participation in previous studies [Citation42–46]. Age, gender-sensitive [Citation38,Citation39] and affordable rehabilitation [Citation40,Citation41] with effective or supportive communication [Citation46], informing patients about their complete care plan [Citation47] by the professionals, and including mental health support services [Citation48–50] are all important for improving rehabilitation. These findings support the need for establishing, implementing, and regulating health care policies which consider all these factors, and inform and involve the patient at every stage [Citation44,Citation51] starting before surgery until full re-integration into the community by MDT [Citation52–54].

As active members of the care team participants identified multiple factors including lack of family and peer supports and timely referrals of patients appropriate for rehabilitation. The socio-cultural expectations of these countries of women caring for their family and children and only undertaking home-based occupations while men are the bread winners, results in families seeing them as a burden rather than support them after LLA, an experience not as significant in developed countries [Citation36–39]. Previous research in developed countries demonstrates this could be improved well established, gender-balanced rehabilitation MDT, as well as family support and inclusion of the patient’s community in the rehabilitation process [Citation40,Citation43,Citation55,Citation56]. Involvement of MDT, including the family, in service planning from acute-care to community reintegration should begin pre-amputation with involvement in decisions for amputation or limb deficiency aiming to provide the best possible outcome [Citation51,Citation55,Citation57,Citation58]. Increasing the number of and gender balance within professionals, along with government regulation and practice guidelines is key to improving service quality and thereby rehabilitation access and participation [Citation56,Citation59,Citation60]. Professional bodies and governments need to work together to improve the quality of services and professional education [Citation6,Citation52,Citation61].

Being integral stakeholders within the organizations, the rehabilitation provider participants with were positioned to identify the experience of limited numbers of rehabilitation centres, lack of support systems, and low quality of services. Rehabilitation services are commonly not a component within mainstream health services in these regions are therefore dependent on national and international NGOs who often impose traditional westernized service models rather than customization to the local context, a relevance currently being also questioned by other researchers [Citation62,Citation63]. The findings suggest the need for increasing rehabilitation centre numbers in appropriate locations to improve local access, with customized support systems catering to the needs of different socio-economic groups [Citation2,Citation6,Citation40,Citation64]. Additionally, improving or resourcing local professional education and practice and human resources to enable MTD with the technological availability for sustainable rehabilitation programs is recommended to improve rehabilitation access and participation [Citation55,Citation65,Citation66].

Practicing within the health system involves navigating local economic, political, and physical environments providing the rehabilitation participants with deep insights contributing to the identification of important factors at the environment level of health services in their country [Citation67]. Rehabilitation not being a component within national health systems and weak supporting policy results in a lack of awareness, and rehabilitation costs out of reach for most patients, a key challenge for development initiatives [Citation18,Citation21,Citation40]. The lack of financial supports for patients, negative societal attitudes, inaccessible transport, conflict or other security issues, combined with poor policy support of rehabilitation professionals impact rehabilitation in these countries have also been identified in other studies [Citation56,Citation68]. These factors impact all levels of health services in these regions and are different to challenges in developed countries necessitating contextually appropriate support plans for at-risk persons [Citation52,Citation68,Citation69]. Along with financial support, this requires changes in cultural and social attitudes towards expectations of economic independence, activities of daily living, occupation and conjugal life [Citation70,Citation71]. Service delivery plans should consider barriers unique to each context and environment to facilitate optimum individual rehabilitation outcomes [Citation40,Citation72]. The many factors identified relating to policies impacting rehabilitation in these countries suggest the importance of governments re-evaluating and re-developing policy to support effective implementation in the field [Citation14,Citation52,Citation73–75].

The identification of multiple interlinked factors influencing rehabilitation at all levels of HCDSA in these countries, supporting the need for comprehensive measures for improvements using systems approaches applied in developed countries [Citation7,Citation26,Citation76,Citation77]. The collection of data from the rehabilitation professionals is congruent with the World Health Organization’s healthcare-system development initiatives [Citation77] and provides new and more system focussed information than that of studies focussed on only the patient experiences in this region [Citation6]. Participants identified multiple key factors (barrier and enablers) at different levels of the healthcare delivery system impacting both rehabilitation access and participation in their countries. This reinforces concerns around serious health system gaps in this region [Citation6,Citation64] as well as evidencing the benefits of evaluation of health systems and strategies from different stakeholders viewpoints within and across the rehabilitation system [Citation14].

The identification of important common factors impacting rehabilitation access and participation in these countries with limited resources throughout this region [Citation78] suggests possibilities and opportunities to design common and targeted mitigations using collaborative approaches [Citation74,Citation79]. However, although collaborative improvement opportunities are potentially significant, the diversity of health care models [Citation74], lack of resources [Citation2,Citation6], and geo-political differences [Citation80] also suggests the necessity for customization of services specific to local contexts [Citation7,Citation52,Citation81]. This also suggests the need for detailed planning before the adoption or imposition of western and/or charitable models, a currently experience with many NGOs and other well-meaning organizations [Citation73,Citation82].

Recommendations for future research

This study identified many factors, both barriers and enablers, interacting within the different layers of the health system. Although the rehabilitation professional participants identified detailed and diverse factors impacting rehabilitation access and participation, many of them acknowledged gaps in their understanding of policy-level factors that need to be explored through further research involving organizational and policy-level stakeholders. Also, this study explored access to and participation in rehabilitation but not return to life after initial rehabilitation, including re-integration into occupation post-LLA. Therefore, further research is needed of rehabilitation professionals’ understanding of factors impacting rehabilitation and return to occupation towards identifying and understanding factors impacting people with LLA in this region, to underpin best practice services strategies.

Strengths and limitations

Although qualitative research methods have some limitations, this methodology is important in providing an understanding of the complexity and background of actions to a specific problem [Citation83]. This study aimed to recruit participants from 25 countries but despite extensive measures was able to only recruit from 13. Attempts were made to reach participants in the 12 countries not included in this study. Eight of those countries (Kyrgyzstan, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Maldives, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Timor Leste, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) are not member countries of international rehabilitation professional organizations e.g., physiotherapy, occupational therapy, P&O, etc. which made them difficult to reach and difficult to identify rehabilitation systems and potential contacts. Despite these efforts, we were unable to identify any meaningful information about them due to a lack of evidence or research in these countries, including in our earlier scoping review study in which we attempted to understand LLA rehabilitation in these regions [Citation6]. The use of a convenience sample may limit generalisability [Citation84] Some countries such as China which have been identified as having policies limiting research participation [Citation85] were not recruited. Interviewing online and having English as the language of communication were potential barriers to participation in the study. The research was undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic which may have impacted services including rehabilitation and created further difficulties reaching potential participants. However, while data saturation may not have been reached with this convenience sample, it has been recently argued by Braun & Clarke (2021) that when undertaking thematic analysis judgements about when to stop data collection are subjective and should not be determined prior to analysis [Citation86].

The aim of this study was to address rehabilitation access and participation rather than return to occupation which is a factor that needs further researching. The use of a framework other than the HCDSA framework may have different outcome to other approaches, but using a bio-psychosocial approach provides opportunity for generalisability of outcomes [Citation7]. However, this study provides new and rich information to inform a significant gap in the evidence base in the understanding of rehabilitation practice for people with LLA in the region.

Conclusion

This study identified many key interlinked factors using the HCDSA framework which impact rehabilitation access and participation for people with LLA. The multi-dimensional dynamics affecting rehabilitation start from individual patient characteristics (gender, education, etc.), skills and resources (economic, information, etc.); include care-team characteristics, functions (family, challenges, etc.), and external influences (referral); organizational challenges to service delivery (models, qualities, etc.); and physical and psychosocial environmental factors (cost and financial support), physical, political, social and cultural factors. These findings underpin the need for a systems approach to developing improvements which address all levels of health service provision in developing Asian countries. The provision of services with the patient as the primary focus for rehabilitation with well-supported management plans starting from acute care and continuing to community re-integration is a priority for improvement initiatives. Sustainable rehabilitation policies need to be embedded into the primary to tertiary healthcare facilities to ensure rehabilitation access and participation for all. And policies need to comprehensively address issues at all layers of health services to improve practice, with sustainable resources as a key strategy to improving accessible rehabilitation in all countries in this region.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (41.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge the survey and interview participants for sharing both their time and experiences. This study would not have been possible without their contributions, and that of those who shared our invitation to enable the participants involvement.

Disclosure statement

The authors confirm they have no potential conflict of interest in the study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Silander NC. Life-Changing injuries: psychological intervention throughout the recovery process following traumatic amputations. J Health Serv Psychol. 2018;44(2):74–78.

- Sayeed MSI, Oakman J, Dillon MP, et al. Disability, economic and work-role status of individuals with unilateral lower-limb amputation and their families in Bangladesh, post-amputation, and pre-rehabilitation: a cross-sectional study’. Work. 1 Jan. 2022:1405–1419. https://content.iospress.com/articles/work/wor211064. DOI: 10.3233/WOR-211064

- Wee J, Lysaght R. Factors affecting measures of activities and participation in persons with mobility impairment. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(20):1633–1642.

- Shakespeare T, Officer A. Breaking the barriers, filling the gaps. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(18):1487–1488.

- Madans J, Loeb M, Eide AH. Measuring disability and inclusion in relation to the 2030 agenda on sustainable development. Disabil Glob South. 2017;4:1164–1179.

- Sayeed MSI, Oakman J, Dillon MP, et al. Influential factors for access to and participation in rehabilitation for people with lower limb amputation in east, South, and southeast Asian developing countries: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(25):8094–8109.

- Reid PP, Compton WD, Grossman JH, et al. Building a better delivery system: a new engineering/health care partnership. (Committee on engineering and the health care system, national academy of engineering, institute of medicine, editors.). Washington (DC): The National Academic Press; 2005.

- Asian Development Bank. Asian development outlook 2021. Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank; 2021. Available from: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/692111/ado2021.pdf.

- DFAT Australia. List of developing countries. Barton. 2018. Available from: https://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Pages/list-of-developing-countries-as-declared-by-the-minister-for-foreign-affairs.aspx.

- Imam MHA, Alamgir H, Akhtar NJ, et al. Characterisation of persons with lower limb amputation who attended a tertiary rehabilitation centre in Bangladesh. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(14):1995–2001.

- Aftabuddin M, Islam N, Jafar M, et al. The status of lower-limb amputation in Bangladesh: a 6-year review. Surg Today. 1997;27(2):130–134.

- Burger H, Marinček Č. Return to work after lower limb amputation. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(17):1323–1329.

- Shigli K, Hebbal M, Angadi GS. Prosthetic status and treatment needs among patients attending the prosthodontic department in a dental institute in India. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2009;17:85–89.

- Darzi AJ, Officer A, Abualghaib O, et al. Stakeholders’ perceptions of rehabilitation services for individuals living with disability: a survey study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:2.

- Choong M, Chau T, Chy D, et al. Clinical management of quadriplegia in low and Middle-income countries: a patient’s road to physiotherapy, prostheses and rehabilitation. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2018225171.

- Magnusson L. Professionals’ perspectives of prosthetic and orthotic services in Tanzania, Malawi, Sierra Leone and Pakistan. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2019;43(5):500–507.

- Järnhammer A, Andersson B, Wagle PR, et al. Living as a person using a lower-limb prosthesis in Nepal. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(12):1426–1433.

- World Health Organization. Template for rehabilitation information collection (TRIC): a tool accompanying the systematic assessment of rehabilitation situation (STARS). Geneva: World Health Organisation (WHO); 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/template-for-rehabilitation-information-collection-(-tric)

- Khasnabis C, Heinicke Motsch K, Achu K, et al. Assistive devices – community-based rehabilitation_ CBR guidelines. In: Rehabilitation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Franz S, Muser J, Thielhorn U, et al. Inter-professional communication and interaction in the neurological rehabilitation team: a literature review. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(11):1607–1615.

- Mills J-A, Marks E, Reynolds T, et al. Rehabilitation: essential along the continuum of care. In: Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, Jha P, Laxminarayan R, Mock CN, NUgent R, editors. Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty. 3rd ed. Washington (DC): World bank; 2018. pp 285–295. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525298/

- Barnett C, Davis R, Mitchell C, et al. The vicious cycle of functional neurological disorders: a synthesis of healthcare professionals’ views on working with patients with functional neurological disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(10):1802–1811.

- Booth A, Hannes K, Harden A, et al. COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies). In: Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Simera I, Wager E, editors. Guidelines for reporting health research: a user’s manual. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014. P. 214–226.

- Sayeed MSI, Oakman J, Stuckey R. Rehabilitation professionals’ perspectives of factors influencing return to occupation for people with lower limb amputation in east, South, and southeast asian developing countries: a qualitative study. Front Public Heal. 2023;11:1039279.

- ADB. Asian Development Outlook (ADO) 2019: Strengthening Disaster Resilience. 2019. Available from: https://www.adb.org/publications/asian-development-outlook-2019-strengthening-disaster-resilience.

- Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327.

- Questionpro. Online Survey Software and Tools | QuestionPro®. 2022. [cited 2022 July 11]. Available from: https://www.questionpro.com/.

- Anon. Otter.ai – Voice Meeting Notes & Real-time Transcription. [cited 2022 April 8]. Available from: https://otter.ai/

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589–597.

- O’Connor C, Joffe H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods;19:1609406919899220.

- Ferlie EB, Shortell SM, Quarterly TM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):281–315.

- Darter BJ, Hawley CE, Armstrong AJ, et al. Factors influencing functional outcomes and return-to-work after amputation: a review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(4):656–665.

- Stuckey R, Draganovic P, Ullah MM, et al. Barriers and facilitators to work participation for persons with lower limb amputations in Bangladesh following prosthetic rehabilitation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2020;44(5):279–289.

- Kennedy BM, Rehman M, Johnson WD, et al. Healthcare providers versus patients’ understanding of health beliefs and values. Patient Exp J. 2017;4(3):29–37.

- Somani T. Importance of educating girls for the overall development of society: a global perspective. JERAP. 2017;7(1):125–139.

- Ott J, Champagne SN, Bachani AM, et al. Scoping ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ in rehabilitation: (mis)representations and effects. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21(1):179.

- Cutson TM, Bongiorni DR. Rehabilitation of the older lower limb amputee: a brief review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(11):1388–1393.

- Laatsch L, Shahani BT. The relationship between age, gender and psychological distress in rehabilitation inpatients. Disabil Rehabil. 1996;18(12):604–608.

- Allen APTT, Bolton WS, Jalloh MB, et al. Barriers to accessing and providing rehabilitation after a lower limb amputation in Sierra Leone – a multidisciplinary patient and service provider perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(11):2392–2399.

- Miyata Y, Sasaki K, Guerra G, et al. Sustainable, affordable and functional: reimagining prosthetic liners in resource limited environments. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(12):2941–2947.

- Geertzen JHB, Martina JD, Rietman HS. Lower limb amputation part 2: rehabilitation-a 10 year literature review. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2001;25(1):14–20.

- Meier RH, Choppa AJ, Johnson CB. The person with amputation and their life care plan. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2013;24(3):467–489.

- Fitzpatrick MC. The psychologic assessment and psychosocial recovery of the patient with an amputation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;361:98–107.

- Abou-Zamzam AM, Teruya TH, Killeen JD, et al. Major lower extremity amputation in an academic vascular center. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003;17(1):86–90.

- Taylor E, Jones F. Lost in translation: exploring therapists’ experiences of providing stroke rehabilitation across a language barrier. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(25):2127–2135.

- Ostler C, Ellis-Hill C, Donovan-Hall M. Expectations of rehabilitation following lower limb amputation: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(14):1169–1175.

- Deans S, Burns D, McGarry A, et al. Motivations and barriers to prosthesis users participation in physical activity, exercise and sport: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2012;36(3):260–269.

- Senra H, Oliveira RA, Leal I, et al. Beyond the body image: a qualitative study on how adults experience lower limb amputation. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(2):180–191.

- Bhutani S, Bhutani J, Chhabra A, et al. Living with amputation: anxiety and depression correlates. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2016;10(9):RC09–RC12.

- NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation (ACI). ACI care of the person following amputation: minimum standards of care. 1.0. Chatswood (NSW): ACI Rehabilitation Network; 2017. Available from: www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au

- Furtado S, Briggs T, Fulton J, et al. Patient experience after lower extremity amputation for sarcoma in England: a national survey. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(12):1171–1190.

- Zidarov D, Swaine B, Gauthier-Gagnon C. Life habits and prosthetic profile of persons with lower-limb amputation during rehabilitation and at 3-month follow-up. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11):1953–1959.

- Demey D. Post-amputation rehabilitation in an emergency crisis: from preoperative to the community. Int Orthop. 2012;36(10):2003–2005.

- Ennion L, Rhoda A. Roles and challenges of the multidisciplinary team involved in prosthetic rehabilitation, in a rural district in South Africa. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:565–573.

- Ennion L, Johannesson A. A qualitative study of the challenges of providing pre-prosthetic rehabilitation in rural South Africa. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2018;42(2):179–186.

- Bhuvaneswar CG, Epstein LA, Stern TA. Reactions to amputation: recognition and treatment. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(4):303–308.

- Marshall C, Stansby G. Amputation and rehabilitation. Surgery. 2010;28(6):284–287.

- Harkins CS, McGarry A, Buis A. Provision of prosthetic and orthotic services in low-income countries: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2013;37(5):353–361.