Abstract

Purpose

To examine the applicability and process of change of Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT) in the management of pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis who were offered knee replacement surgery and had risk factors for poor response to surgery.

Methods

Single-case experimental design with a mixed-methods, repeated measures approach was used to investigate the process of change through CFT in four participants. Qualitative interviews investigated beliefs, behaviours and coping responses, and self-reported measures assessed pain, disability, psychological factors, and function at 25 timepoints. Study registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12619001491156).

Results

Qualitative data indicate that CFT promoted helpful changes in all participants, with two responses observed. One reflected a clear shift to a biopsychosocial conceptualisation of osteoarthritis, behavioural re-engagement and the view that a knee replacement was no longer necessary. The other response reflected a mixed conceptualisation with dissonant beliefs about osteoarthritis and its management. Psychological and social factors were identified as potential treatment barriers. Overall, quantitative measures supported the qualitative findings.

Conclusion

The process of change varies between and within individuals over time. Psychological and social barriers to treatment have implications for future intervention studies for the management of knee osteoarthritis.

Cognitive Functional Therapy is applicable in the management of knee osteoarthritis.

Reconceptualisation of osteoarthritis reflected a helpful change.

Psychological and social factors emerged as barriers to recovery.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

The personal and societal impact of knee osteoarthritis places substantial burden on health systems worldwide [Citation1,Citation2]. All major clinical guidelines recommend non-surgical care for all people with knee osteoarthritis [Citation3,Citation4]. However, up to 25% of knee replacement surgeries are performed on inappropriate candidates who are at high risk of non-response to surgery [Citation5,Citation6]. This is partly due to misconceptions among patients and clinicians about osteoarthritis and its management [Citation7].

Common misconceptions are that pain and functional limitation associated with knee osteoarthritis are due to irreversible structural changes caused by ‘wear and tear’ [Citation8]; and that loading the joint causes damage [Citation7]. These beliefs impact on a person’s confidence to be physically active often leading to disability and distress [Citation7–9]. In contrast, evidence supports that osteoarthritis-related pain and disability is influenced by the interaction of multiple biopsychosocial factors, which modulate inflammatory processes and behavioural responses [Citation10–13].

This contrasting view reinforces the critical role of non-surgical approaches to manage knee osteoarthritis [Citation14]. Non-surgical core treatments for OA include exercise, weight-loss and education and support for self-management [Citation15]. Despite their efficacy [Citation16], many patients do not respond, and may also be at risk of not responding to surgery [Citation6]. These patients may require a personalised non-surgical approach that addresses multi-dimensional drivers of pain and disability [Citation13].

Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT) is a physiotherapist-led behavioural approach that targets modifiable multidimensional factors underlying a person’s pain and disability [Citation17]. CFT aims to coach people towards self-management, by providing a personalized biopsychosocial understanding of their condition, building confidence to engage in feared, painful or avoided movements and activities, coaching a healthy lifestyle and self-management of flare-ups [Citation17]. Efficacy trials demonstrated CFT to be more efficacious than usual care [Citation18], traditional physiotherapy [Citation19,Citation20] and group education and exercise [Citation21] for people with disabling back pain. While knee osteoarthritis and chronic back pain share similar multidimensional drivers of pain and disability [Citation11,Citation13], it is not known whether CFT is also applicable to people with knee osteoarthritis.

To understand the applicability of CFT in the management of pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis, we conducted a multiple single-case series. This study involved people with osteoarthritis who had been offered knee replacement surgery, but had risk factors of poor response to surgery including, higher body mass index (BMI), better function, poorer mental health and less severe radiographic knee osteoarthritis Kelgren-Lawrence grading [Citation6]. The specific aim of this study was to understand the process of change through CFT, using a mixed-methods, repeated measures approach. Qualitative interviews investigated beliefs, behaviours and coping responses and self-reported measures assessed pain, disability and psychological factors, and function.

Methods

This study complies with the Single-Case Reporting guideline In BEhavioural interventions (SCRIBE) 2016 [Citation22].

Study design

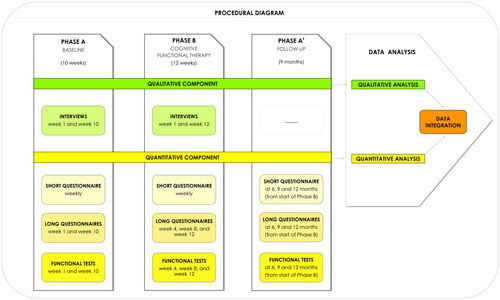

A triangulation convergent mixed-method design embedded in an A-B-A′ non-randomised, single-case experimental design study (SCEDs) with repeated measures (). Qualitative and quantitative data were collected concurrently and integrated during analysis to enable rich interpretation of the process of change [Citation23].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the study design and procedures. Footnote to Figure 1. Short questionnaire measured the following items: patient-specific function, pain intensity, and psychological factors (bothersomeness, fear beliefs, knee confidence, pain control and pain catastrophising). Long questionnaires measured the following items: disability and pain (Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scale using the daily living and pain sub-scales), and psychological factors including, fear beliefs (Knee Osteoarthritis Fears and Beliefs Questionnaire), Pain control (Brief Pain Coping Inventory-2), and Pain catastrophising (pain catastrophising scale). Functional tests included: 40m fast-paced walk test (Wright et al 2011), and a 30 second chair stand test (Jones et al 1999). Both functional tests are OARSI guideline recommended (Dobson et al 2013).

Phase A consisted of a 10-week baseline phase during which participants received no intervention. This phase acted as a comparator to determine within-person change [Citation24]. During Phase A, two qualitative interviews (see Data collection section below) were conducted at weeks 1 and 10 (pre-intervention), and weekly quantitative measures were collected on up to 10 occasions. Phase B was a 12-week intervention phase where participants received up to 8 sessions of CFT [Citation17]. During Phase B two interviews were conducted, one after the first CFT session (early-intervention) and one at the end of the intervention (post-intervention); with weekly quantitative measures collected on up to 12 occasions. As the effect of behavioural interventions are expected to carry over after the intervention ceased, the subsequent Phase A’ was used as a follow-up monitoring period during which participants received no intervention. This phase consisted of the same weekly measures over 1 week at three different timepoints (6, 9 and 12-month) after commencing treatment. No qualitative data was collected during Phase A′.

The study was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12619001491156). There were no protocol deviations, but this paper reports non-obese participants only. Obese participants were offered an additional treatment phase of psychologically-based weight management and will be reported separately to adequately capture the extra complexity.

Participants

Eligible people were (i) aged ≥30 years with knee osteoarthritis presenting to orthopaedic surgeons or general practitioners in Perth, Australia; (ii) had been offered knee replacement surgery; (iii) had >15% risk for non-response to surgery according to a prognostic nomogram [Citation6], and (iv) were willing to undergo CFT. Exclusion criteria were (i) previous major ipsilateral knee surgery; (ii) pregnancy; (iii) compromised cognitive state (e.g., psychiatric disorder); (iv) comorbidities causing severe mobility impairment (e.g., Parkinson’s disease).

Seventeen people were screened for eligibility. Sequential candidates were purposively selected to capture different profiles of factors assessed by the nomogram, resulting in four non-obese participants (BMI <30 kg/m2).

This study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee at Melbourne University (1646845); and reciprocal approval was granted at Curtin University (HRE2018-0097). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Intervention

The CFT intervention was delivered face-to-face in a clinical setting by three specifically-trained physiotherapists who had reached an acceptable level of competency and had at least 100 h of experience in delivering CFT. The CFT intervention aimed to coach people to self-manage their pain symptoms using three principle processes: (1) making sense of pain; (2) exposure with control; (3) lifestyle coaching (see for description of the principles, and a detailed CFT management for each case).

Table 1. Multidimensional factors and cognitive functional therapy (CFT) management for the four clinical cases.

Treatment dosage

Up to 8 sessions in total over the 12-week intervention. One-hour initial session, and 30–45 min follow-ups. Participants were seen weekly for 2–3 sessions and progressed to one session every 2–3 weeks.

Treatment adherence

Participants were encouraged to keep diary on their exercise/activity. Physiotherapists kept a ‘therapist log’ including clinical notes and communication with participants over the study period.

Treatment fidelity

The developer of CFT (POS) was present as an observer in the first session, as well as at a follow up (WEEK 6 or 12), using a fidelity form previously used [Citation19].

Data collection

Qualitative component

Participants completed four one-to-one semi-structured interviews (30–60 min) conducted in person in a private room in a physiotherapy clinic or over the phone by an academic physiotherapist and experienced qualitative researcher (NRK), not previously known to the participants or involved with their treatment. Interviews were structured on the Common Sense Model [Citation25], a health belief theory comprised of four dimensions: (i) understanding of pain, its causes and consequences; (ii) perceptions of pain controllability; (iii) behavioural responses and (iv) emotional responses to pain. This model has previously been applied to understand the process of change through CFT in participants with chronic low back pain [Citation10] (Supplementary A–D). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. At the end of the treatment (Phase B), a short interview with the participant’s partner was completed to support any observed changes during the intervention period (Supplementary E).

Quantitative component

Collected weekly via an electronic short questionnaire during baseline (10 weeks), treatment period (12 weeks) and follow-up period (once at 6, 9 and 12 months after commencing treatment):

Patient-Specific Function: Patient Specific Functional Scale (PSFS) [Citation26]. Participants nominated three activities they found difficult or were unable to perform because of their knee problem. Participants rated how well they were able to perform the activity compared to before their problem on an 11-point numerical rating scale anchored by ‘0 = able’ and ‘10 = unable’. The PSFS score reflecting the most disabling activity was used for analysis.

Pain intensity: measured as average intensity in the last week rated on an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS – 0–10).

Psychological factors: Fear measured by two items from The Knee Osteoarthritis Fears and Beliefs Questionnaire [Citation27]; Knee confidence measured by a single-item from the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scale (KOOS) [Citation28]; Pain control measured by a single-item from Coping Strategy Questionnaire [Citation29]; and Pain self-efficacy measured by the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire-2 [Citation30]; Pain catastrophising measured by 3-items from the Pain Catastrophising Scale (PCS) [Citation31].

The use of standardised outcome measures with established psychometric properties provides information about whether participants have made a meaningful change [Citation32,Citation33]. The following long questionnaires and functional tests were collected twice during baseline (weeks 1 and 10), three times during treatment period (weeks 4, 8 and 12) and follow-up period (at 6, 9 and 12 months after commencing treatment):

Disability: The KOOS Function sub-scale (KOOS-daily living). Minimal clinically important change (MCIC) of 8–10 points in each subscale is considered appropriate for the KOOS [Citation34].

Pain intensity: KOOS Pain Sub scale (KOOS-pain).

Psychological factors: The Knee Osteoarthritis Fears and Beliefs Questionnaire (MCIC not available); Pain control measured by a single-item from the Coping Strategy Questionnaire and the Two-item Brief Pain Coping Inventory-2 [Citation35](MCIC not available); and Pain catastrophising measured by the PCS (MCIC of 6 points) [Citation31].

Function: two OARSI guideline-recommended [Citation36] physical tests, the 40m fast-paced walking test [Citation37], and the 30s chair stand test [Citation38]. The MCIC for these tests are respectively, a change of 0.2–0.3m/s in walking speed, and a change of 2–3 sits to stands [Citation37].

Qualitative data analysis

Transcribed interview data were analyzed following a 5-step Framework Approach [Citation39]. Each step involved two analysts experienced in framework analysis (NRK and BIRdO) who met regularly to agree on interpretations through discussion. Step 1: Data familiarization through reading and re-reading transcripts collected at each time point. Step 2: Coding of data using deductive codes based on the Common Sense Model. Coded data were uploaded into NVivo 12 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) to facilitate further analysis. Step 3: Charting of coded data onto a matrix created for each participant with the four common-sense model dimensions as row headings and each time point as column headings. Step 4: Interpretation of salient perceptions at each timepoint for each participant and how they change over time. Step 5. Description of process of change for each participant presented as themes. Steps 4 and 5 involved group discussion to challenge and agree on emerging interpretations, Group discussion involved members of the research team who were physiotherapists not involved in the CFT intervention.

In the results, a narrative description of the process of change is supported by a tabular summary, in which selected quotes illustrate changes over time for each participant ().

Table 2. Process of change for each participant.

Quantitative data analysis

Weekly measures of disability, pain and psychological factors were graphed for visual inspection of baseline stability and change during Phase B. The academic physiotherapist who collected the data (JST) was not involved in the statistical analysis. Simulation Modelling Analysis (SMA Version 8.3.3, http://clinicalresearcher.org) was used as a statistical test for significant change in each variable between phases A and B after adjusting for autocorrelation [Citation40]. SMA is a nonparametric bootstrapping approach effective at handling short time series data-streams, whilst both adjusting for autocorrelation and reducing the risk of Type I and II errors [Citation40].

Data from the long questionnaires and functional tests were tabulated for all eight timepoints over all three phases. Change scores from Phase A to B were calculated by subtracting the average score from weeks 1 and 10 in Phase A, from the week 12 score in Phase B; and Change scores from phase B to A’ were calculated by subtracting the week 12 score in Phase B, from the average scores from months 6, 9 and 12 in Phase A’. Change scores were referenced against consensus MCIC change where available.

Data integration

To facilitate interpretation of the process of change within and between participants, qualitative data was tabulated alongside radar graphs displaying changes in the weekly measures for each participant (). To support attribution of any systematic change between Phase A and B to the intervention, the interview content (participant and their partner/significant other – Supplementary E) and therapist log were examined to identify explanations for change other than the intervention.

Role of funding source

The funder played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Results

Participants’ profiles and nomogram score

outlines a detailed description of the four cases. describes the participants’ profiles on the risk factors assessed by the nomogram. Participants had different profiles of risk relating to mental health and disability. All participants completed the treatment and all assessments across the three phases of the study. There were no adverse events, and all participants attended all sessions as scheduled. The clinicians reported in the therapist log that for all participants, their functional movement behaviours were modifiable and pain was controllable via guided behavioural experiments used in the first consultation.

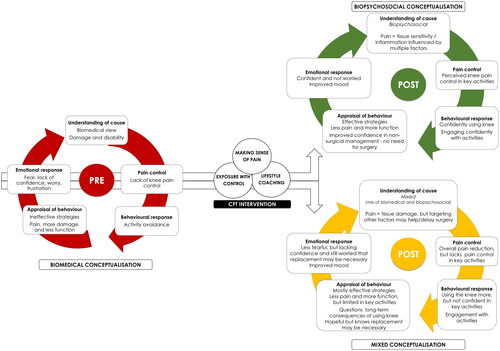

Qualitative findings

Two themes describing different responses to the approach were observed. One (illustrated by Cases 1 and 4) reflected a clear shift to a biopsychosocial conceptualisation of osteoarthritis, behavioural re-engagement and the view that a total knee replacement was no longer necessary. The other response (illustrated by Cases 2 and 3) reflected a mixed conceptualisation (biomedical and biopsychosocial) with dissonant beliefs about osteoarthritis and its management. While these two participants were more behaviourally engaged (physical, work and social) after CFT, they were uncertain about their future need for knee replacement surgery. See for a detailed description of the process of change for each participant.

Significant others

All significant others reported that their respective partner had a similar positive response to CFT that impacted not only on pain, but also on their partner’s ability to engage with meaningful activities be it physical, social or work-related (Supplementary F).

Quantitative findings

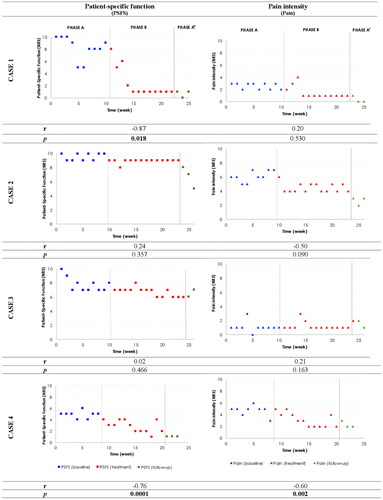

On visual inspection, all participants showed a stable baseline (Phase A) for all weekly measures of patient-specific function and pain, and pain-related psychological factors. Findings from the weekly measures and corresponding statistical tests for change from Phase A to B for each participant are presented in and . These, provide evidence for change for case 1 for patient-specific function and four of five psychological measures, and for case 4 for patient-specific function and pain, and all four psychological measures. In contrast, there was no evidence for change in any of the weekly measures for case 3, and only evidence for change in confidence for case 2.

Figure 2. Patient-specific function and pain intensity. Simulation Modeling Analysis for significant change between baseline and treatment period over the course of the intervention (correlation of data stream with phase vector and respective p-values for patient-specific function and pain intensity). Significant values are displayed in bold. Footnote to Figure 2. NRS: Numerical Rating Scale.

Radar graphs in provide an overview of each participants’ profile and how they varied over the course of the study, including long-term timepoints of months 6, 9 and 12 post-intervention.

Findings from the long questionnaires and functional tests over Phases A and B indicate that cases 1 and 4 reported greater changes in disability (KOOS), pain psychological factors and functional tests () when compared to cases 2 and 3.

Table 3. Patient self-reported outcome measures and functional tests across the three phases of the study.

A similar pattern is again observed in the long-term at months 6, 9 and 12 post-intervention, with cases 1 and 4 maintaining the improvements in disability (KOOS), pain, psychological factors and functional tests (). However, cases 2 and 3 maintained the improvements in disability, pain, and functional tests, and they improved further in pain catastrophising and in fear beliefs about knee osteoarthritis.

Findings from integration of qualitative and quantitative data

Overall, the changes observed in the quantitative measures support the qualitative findings, where cases 1 and 4 demonstrated a greater shift in all factors as measured by both weekly short questionnaires, long questionnaires, and functional tests, when compared to cases 2 and 3 ( and , ).

Specifically, cases 1 and 4 showed a very similar pattern of change. Both cases showed improvement in most quantitative measures in line with their qualitative reports of change in understanding of the condition, improved knee confidence and active engagement in their lives ().

Figure 3. Process of change based on the Common Sense Model, for people with knee osteoarthritis undergoing CFT.

In comparison, cases 2 and 3 presented a mixed pattern of change. Cases 2 and 3 showed no improvement in most weekly quantitative measures, no meaningful improvement in pain catastrophising, and little improvement in fear beliefs about knee osteoarthritis after the intervention (). In contrast, they showed meaningful change in the long questionnaires for disability, pain, pain catastrophising and functional tests, as well as some improvement in fear beliefs (particularly case 3) at long term follow up. The quantitative findings are in line with the experience of these two participants reported by the qualitative findings, where despite reported improvements in function, pain and social interaction, they still reported a lack of confidence in key activities and concern about the long-term consequences to their joint ().

Discussion

Best-practice guidelines strongly recommend non-surgical core treatment for osteoarthritis that include education, exercise and lifestyle changes that support self-management [Citation16]. However, societal misperceptions that osteoarthritis is part of ageing, caused by wear and tear and that surgical replacement of the ‘worn out’ joint is inevitable, affect engagement with these recommended non-surgical treatments to manage the condition [Citation41]. This had led to calls for the management of osteoarthritis to consider the individual needs and context of the person with knee pain [Citation15].

This study aimed to understand the process of change and applicability of CFT, a person-centred behavioural approach for the management of knee osteoarthritis in people at risk of poor response to knee replacement surgery. CFT promoted helpful changes in the four participants. Two different responses to the approach were observed which may be explained by differences in individual psychological and social profiles as discussed below.

A shift towards a biopsychosocial conceptualisation of osteoarthritis

A biopsychosocial conceptualisation about knee osteoarthritis accommodates an understanding of joint pathology within a multidimensional framework. This view supports that CFT can help a person reconceptualise their condition, and actively engage in valued life activities with reduced pain, greater confidence, increased physical activity levels and overall healthier lifestyle [Citation10,Citation42]. Across different musculoskeletal [Citation43] and non-musculoskeletal conditions [Citation44], studies suggest a positive relationship between a helpful understanding of the condition and perceived control over the management of the condition [Citation45].

Cases 1 and 4 had a clear shift in their understanding about knee osteoarthritis. This was evidenced by a reconceptualization of pain as a sign of tissue sensitivity caused by multiple factors rather than a sign of damage. These participants adopted a new understanding in which movement and loading of the knee was viewed as necessary to optimise the health of their joint. This conceptualisation was associated with them becoming more active despite some level of pain, increasing confidence about their future, and adopting a view that a knee replacement was not inevitable. Focusing on what one can do despite their condition, rather than what one cannot do because of their condition, is consistent with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), established by the WHO to promote a common, evidence-based approach to healthcare. The ICF shifts attention away from (only) curing diseased/damaged body parts; towards empowering people to participate in life situations regardless of their health state [Citation46,Citation47].

This study adds to a growing body of evidence[Citation10,Citation48] that experiential learning (a central component of CFT) to de-threaten pain, enhance pain control and build self-efficacy is an important potential mechanism underpinning positive change for people with disabling musculoskeletal pain [Citation49,Citation50].

A shift towards a mixed conceptualisation of osteoarthritis

Misconceptions about osteoarthritis are common among patients, clinicians, and the public [Citation7–9]. These misconceptions appear deeply rooted in society and commonly reinforced by clinicians and may be perpetuated by dominant ways of thinking about the body and pain (i.e., that pain is a sign of damage and it is unsafe to use painful body parts) [Citation42]. This may potentially undermine a person’s confidence to accept an alternative biopsychosocial narrative [Citation9,Citation42].

By the end of the intervention, cases 2 and 3 shifted aspects of their understanding about their condition. They appeared to adopt a mixed conceptualisation whereby they still perceived that pain was caused by tissue damage, but at the same time, believed that targeting other factors could help avoid or delay knee replacement surgery. While this change allowed them to become more functionally active, their focus on the impairment was still present, which may undermine their confidence about the future of their knees and the need for a joint replacement [Citation42].

Interestingly, follow up data indicates sustained changes in the long-term, with cases 2 and 3 reporting reductions in fear and catastrophic thoughts by month 12. It is possible that continued engagement with their knee without experiencing the feared outcome (i.e., more pain and less function) played a role in shifting their cognitive and emotional responses [Citation45,Citation50,Citation51]. The adoption of positive coping strategies has been demonstrated to mediate a shift in beliefs towards a healthier and less threatening understanding of their condition [Citation52]. This highlights the potential need for additional support/booster sessions beyond the 12 weeks’ intervention.

Why did these four cases respond differently to CFT?

Key differences in the social context, work status, activity levels and mental health profile of these participants may have influenced the different patterns of change. Case 1 was still working and somewhat active, with a good social network of support. While Case 4 reported high levels of social stress, she was still attending group exercise classes, which provided a positive environment for interaction. In contrast, Cases 2 and 3 reported greater psychological and social distress, and less social support.

There is growing evidence that health outcomes are explained less by the quality and availability of medical care than they are by the context of people’s lives [Citation53]. For instance, people with lower health literacy, lower income, no life partner and poorer mental health are more likely to develop osteoarthritis and co-morbid health conditions [Citation54]. Community context [Citation55], social support (e.g., family, caregivers) and participation are key for people with osteoarthritis to maintain a healthy lifestyle [Citation56] and stay engaged with meaningful activities [Citation57]. This highlights the potential need for integrated co-care.

How do these findings inform the management of knee osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis has a dominant pervasive ‘impairment’ narrative that is difficult to change, [Citation10,Citation58]. Some people may need more time and/or a more salient experience of safety to shift their conceptualisation about pain as was observed by cases 2 and 3. While CFT may promote a helpful shift, people presenting with more complex psychosocial profiles may require additional co-care to effectively address social determinants of health [Citation59,Citation60]. For instance, co-care with psychologists may provide targeted strategies for management of contextual stress and co-morbid mental health [Citation17,Citation50,Citation61]. Ongoing monitoring of the person’s profile using repeated outcome assessments (e.g., Örebro multidimensional screening [Citation62]) prior to each treatment session and at 3-6 month intervals post-intervention may highlight barriers for recovery, manage flare-ups and trigger appropriate referrals. How this process could be implemented, and its effectiveness are important questions to be addressed by future research.

Nevertheless, for some people a positive and safe experience in which pain is controlled or reduced may not be achievable. Their meaningful activity may always be associated with pain, irrespective of how much other contributing factors are able to be downregulated. In that scenario, reconceptualising the meaning of pain (i.e., accepting that pain may still be present but it is not dangerous to move) and reframing their valued activities (i.e., shifting priorities to align with current functional state), may enable people to participate in their lives despite pain [Citation63].

Design considerations

SCEDs are vulnerable to plausible rival hypotheses that may explain the outcomes such as, maturation, regression to the mean and external factors. Although the authors strategized to limit this problem, by using a stable baseline with ten data points (above the recommended five) [Citation22,Citation64], a therapist log and interview content with the participant and their partner, such possibilities cannot be fully excluded. While the study aimed to include different profiles of people with knee osteoarthritis, some profiles were not included, most evidently, people who are obese. The authors recognise this is a common and important co-morbid issue for people with knee osteoarthritis, and this will be addressed in a separate study. Finally, the authors acknowledge that our backgrounds as researchers with an interest in cognitive and behavioural approaches to the management of musculoskeletal pain and disability, and our clinical backgrounds as physiotherapists caring for people with knee osteoarthritis informed the analysis and interpretations of the data from this study. The presentation of qualitative data serves to render the authors’ interpretations visible to readers.

The strength of the current study lies on the richness of data provided by the SCED. This design enabled an in-depth analysis of the process of change in a challenging group of patients with knee osteoarthritis undergoing a novel individualised behavioural approach.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the applicability of CFT for the management of knee osteoarthritis. While CFT promoted helpful changes in four people with knee osteoarthritis, two different responses to the approach are documented. One reflected a clear shift to a biopsychosocial conceptualisation of osteoarthritis and its management. The other response reflected a mixed conceptualisation with dissonant beliefs about the condition, rendering them uncertain regarding knee replacement surgery in their future. Individual psychological and social factors emerged as potential barriers to treatment, and have been discussed as considerations for future intervention studies for the management of knee osteoarthritis.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (56.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants for devoting their time and efforts during the process of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us. The institution of one or more of the authors (PFC, AS, PO, MMD) has received, during the study period, funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Centre of Research Excellence in Joint Replacement Surgery (APP1116325)

Data availability statement

Data for the four participants of this study is embedded in the manuscript and individually presented either in a graphic or table format.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- NICE Guideline [NG226] Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2022 [updated 2022 Oct 19; cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226.

- Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323–1330.

- Arden NK, Perry TA, Bannuru RR, et al. Non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis: comparison of ESCEO and OARSI 2019 guidelines. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(1):59–66.

- Bannuru RR, Osani M, Vaysbrot E, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(11):1578–1589.

- Cobos R, Latorre A, Aizpuru F, et al. Variability of indication criteria in knee and hip replacement: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11(1):1–9.

- Dowsey MM, Spelman T, Choong PFM. Development of a prognostic nomogram for predicting the probability of nonresponse to total knee arthroplasty 1 year after surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(8):1654–1660.

- Bunzli S, O’Brien P, Ayton D, et al. Misconceptions and the acceptance of evidence-based nonsurgical interventions for knee osteoarthritis. A qualitative study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(9):1975–1983.

- Teo PL, Bennell KL, Lawford BJ, et al. Physiotherapists may improve management of knee osteoarthritis through greater psychosocial focus, being proactive with advice, and offering longer-term reviews: a qualitative study. J Physiother. 2020;66(4):256–265.

- Darlow B, Brown M, Thompson B, et al. Living with osteoarthritis is a balancing act: an exploration of patients’ beliefs about knee pain. BMC Rheumatol. 2018;2(1):15.

- Caneiro JP, Smith A, Linton SJ, et al. How does change unfold? An evaluation of the process of change in four people with chronic low back pain and high pain-related fear managed with cognitive functional therapy: a replicated single-case experimental design study. Behav Res Ther. 2019;117:28–39.

- Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1745–1759.

- Hunter DJ, Bowden JL. Are you managing osteoarthritis appropriately? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(12):703–704.

- Kittelson AJ, George SZ, Maluf KS, et al. Future directions in painful knee osteoarthritis: harnessing complexity in a heterogeneous population. Phys Ther. 2014;94(3):422–432.

- Caneiro JP, Sullivan PB, Roos EM, et al. Three steps to changing the narrative about knee osteoarthritis care: a call to action. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(5):256–258.

- Bowden JL, Hunter DJ, Deveza LA, et al. Core and adjunctive interventions for osteoarthritis: efficacy and models for implementation. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(8):434–447.

- Smedslund G, Kjeken I, Musial F, et al. Interventions for osteoarthritis pain: a systematic review with network meta-analysis of existing cochrane reviews. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2022;4(2):100242.

- O’Sullivan PB, Caneiro JP, O’Keeffe M, et al. Cognitive functional therapy: an integrated behavioral approach for the targeted management of disabling low back pain. Phys Ther. 2018;98(5):408–423.

- Kent P, Haines T, O’Sullivan P, et al. Cognitive functional therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): a randomised, controlled, three-arm, parallel group, phase 3, clinical trial. The Lancet. 2023;401(10391):1866–1877.

- Vibe Fersum K, O’Sullivan P, Skouen J, et al. Efficacy of classification‐based cognitive functional therapy in patients with non‐specific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(6):916–928.

- Vibe Fersum K, Smith A, Kvåle A, et al. Cognitive functional therapy in patients with non‐specific chronic low back pain—a randomized controlled trial 3‐year follow‐up. Eur J Pain. 2019;23(8):1416–1424.

- O’Keeffe M, O’Sullivan P, Purtill H, et al. Cognitive functional therapy compared with a group-based exercise and education intervention for chronic low back pain: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT). Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(13):782–789.

- Tate RL, Perdices M, Rosenkoetter U, et al. The single-case reporting guideline in BEhavioural interventions (SCRIBE) 2016: explanation and elaboration. Arch Scient Psychol. 2016;4(1):10–31.

- Creswell JW. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. In: Creswell John W, Plano Clark Vicki L, editors. Los Angeles, California: SAGE Publications; 2011.

- Tate RL, Perdices M, Rosenkoetter U, et al. Revision of a method quality rating scale for single-case experimental designs and n-of-1 trials: the 15-item risk of bias in N-of-1 trials (RoBiNT) scale. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2013;23(5):619–638.

- Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn Ther Res. 1992;16(2):143–163.

- Westaway MD, Stratford PW, Binkley JM. The Patient-Specific Functional Scale: validation of its use in persons with neck dysfunction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27(5):331–338.

- Benhamou M, Baron G, Dalichampt M, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire assessing fears and beliefs of patients with knee osteoarthritis: the knee osteoarthritis fears and beliefs questionnaire (KOFBeQ). PLOS One. 2013;8(1):e53886.

- Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, et al. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28(2):88–96.

- Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 17(1):33–44.

- Nicholas MK, McGuire BE, Asghari A. A 2-Item short form of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire: development and psychometric evaluation of PSEQ-2. J Pain. 2015;16(2):153–163.

- Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–532.

- Morley S. Single case methods in clinical psychology: a practical guide. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge; 2017.

- Onghena P, Van Damme G. SCRT 1.1: single-case randomization tests. Behav res meth instrum comput. 1994;26:369. DOI:10.3758/BF03204647

- Roos EM, Lohmander LS. The knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):1–8.

- Cleeland C, Ryan K. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1994;23(2):129–138.

- Dobson F, Bennell K, Hinman R, et al. Recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Melbourne: OARSI. 2012.

- Wright AA, Cook CE, Baxter GD, et al. A comparison of 3 methodological approaches to defining major clinically important improvement of 4 performance measures in patients with hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(5):319–327.

- Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC. A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70(2):113–119.

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. Analyzing qualitative data. London:Routledge; 1994. Chapter 9, p. 173–194.

- Borckardt JJ, Nash MR, Murphy MD, et al. Clinical practice as natural laboratory for psychotherapy research: a guide to case-based time-series analysis. Am Psychol. 2008;63(2):77–95.

- Hunter DJ, March L, Chew M. Osteoarthritis in 2020 and beyond: a lancet commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10264):1711–1712.

- Bunzli S, Taylor N, O’Brien P, et al. How do people communicate about knee osteoarthritis? A discourse analysis. Pain Med. 2021;22(5):1127–1148.

- De Raaij EJ, Ostelo RW, Maissan F, et al. The association of illness perception and prognosis for pain and physical function in patients with noncancer musculoskeletal pain: a systematic literature review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48(10):789–800.

- Hagger MS, Orbell S. A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychol Health. 2003;18(2):141–184.

- Hagger MS, Koch S, Chatzisarantis NL, et al. The common sense model of self-regulation: meta-analysis and test of a process model. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(11):1117–1154.

- Whiteneck G, Dijkers MP. Difficult to measure constructs: conceptual and methodological issues concerning participation and environmental factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11 Suppl):S22–S35.

- ICF. 1.The ICF: an overview; 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.wcpt.org/sites/wcpt.org/files/files/GHICF_overview_FINAL_for_WHO.pdf.

- Bunzli S, McEvoy S, Dankaerts W, et al. Patient perspectives on participation in cognitive functional therapy for chronic low back pain. Phys Ther. 2016;96(9):1397–1407.

- Edwin de Raaij E, Harriet Wittink H, Francois Maissan J, et al. Illness perceptions; exploring mediators and/or moderators in disabling persistent low back pain. Multiple baseline single-case experimental design. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1–14.

- Caneiro J, Smith A, Bunzli S, et al. From fear to safety: a roadmap to recovery from musculoskeletal pain. Physical Ther. 2022;102(2):pzab271.

- Craske MG, Stein MB, Eley TC, et al. Anxiety disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17024.

- McAndrew LM, Crede M, Maestro K, et al. Using the common-sense model to understand health outcomes for medically unexplained symptoms: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2019;13(4):427–446.

- Daniel H, Bornstein SS, Kane GC, et al. Addressing social determinants to improve patient care and promote health equity: an American college of physicians position paper. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(8):577–578.

- Vennu V, Abdulrahman TA, Alenazi AM, et al. Associations between social determinants and the presence of chronic diseases: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–7.

- Kowitt SD, Aiello AE, Callahan LF, et al. How are neighborhood characteristics associated with mental and physical functioning among older adults with radiographic knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Care Res. 2021;73(3):308–317.

- Rantakokko M, Wilkie R. The role of environmental factors for the onset of restricted mobility outside the home among older adults with osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e012826.

- Willett M, Greig C, Fenton S, et al. Utilising the perspectives of patients with lower-limb osteoarthritis on prescribed physical activity to develop a theoretically informed physiotherapy intervention. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):1–13.

- Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The Common-Sense model of Self-Regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med. 2016;39(6):935–946.

- Ramanuj P, Ferenchick EK, Pincus HA. Depression in primary care: part 2—management. BMJ. 2019;365:l835.

- Marmot M, Bell R. Social determinants and non-communicable diseases: time for integrated action. BMJ. 2019;364:l251.

- Keefe FJ, Main CJ, George SZ. Advancing psychologically informed practice for patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain: promise, pitfalls, and solutions. Phys Ther. 2018;98(5):398–407.

- Linton SJ, Halldén K. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. Clin J Pain. 1998;14(3):209–215.

- Klem N-R, Smith A, O’Sullivan P, et al. What influences patient satisfaction after TKA? A qualitative investigation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(8):1850–1866.

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock J, Horner R, et al. Single-case designs technical documentation; 2010. Retrieved from What Works Clearinghouse website: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

Appendix

Table A1. Participants’ characteristics.

Table A2. Pain-related psychological factors.

Simulation modeling analysis for significant change between baseline and treatment period over the course of the intervention (correlation of data stream with phase vector and respective p-values for pain-related psychological factors). Significant values displayed in bold.