Abstract

Purpose

To understand the pathways of children with disability participating in gymnastics in Victoria, Australia.

Materials and methods

A sequential explanatory mixed-method study design was used. Participants completed an online survey, with selected participants purposively invited to undertake semi-structured interviews via videoconference. Quantitative survey data was analysed using descriptive statistics with preliminary findings informing the invitation of interview participants and refinement of interview questions. Qualitative survey and interview data were analysed together using thematic analysis to create themes. Data was combined to create a conceptual model.

Results

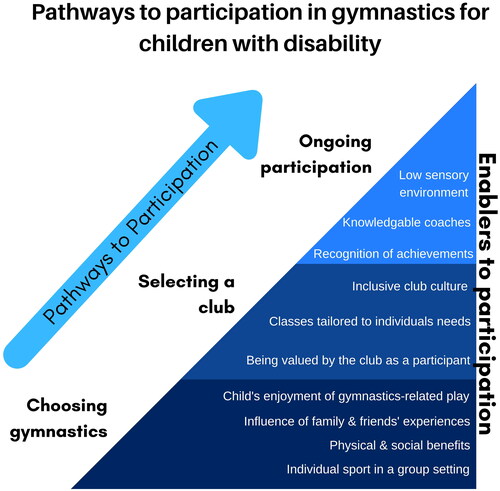

Fifty-eight parents consented to participate in the study with eight interviews conducted. Key themes were: (1) Tailored, accessible, supportive environments and programs make a difference, (2) An explicitly inclusive club culture helps young people get and stay involved, (3) Coach knowledge about engaging children with disability is valued, (4) Enjoyment, recognition, and achievement facilitate ongoing participation, and (5) Gymnastics has physical and social benefits for children with disability. The findings inform a conceptual model that describes three key stages along a pathway to participation including; choosing gymnastics as a sport, selecting a club, and ongoing participation.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore participation of children with disability in gymnastics in Australia. These findings provide guidance to those supporting children with disability to participate in gymnastics (e.g., policy makers, club owners, coaches, and allied health professionals) regarding creating more inclusive environments and experiences at each stage of participation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

This study furthers our understanding of the impact of childhood disability on participation in sport and recreation, with a focus on gymnastics.

A combination of accessible environments, inclusive club cultures, recognition and enjoyment, and knowledgeable coaches facilitated participation in gymnastics.

Parents perceive gymnastics to have physical and social benefits for their child.

A conceptual model has been developed based on the findings to support gymnastics clubs and assist rehabilitation professionals to understand the challenges and enablers to participating in gymnastics.

Introduction

It is well known that physical activity has numerous benefits for children including social inclusion, improving physical fitness and motor coordination, increasing self-esteem and quality of life [Citation1]. However, children with disability usually participate in lower levels of physical activity, and fewer meet Physical Activity Guidelines compared to typically developing children [Citation2,Citation3].

Children with disability often encounter several barriers when attempting to participate in sports and recreation. These barriers largely relate to the environmental and personal factors domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) [Citation4]. Environmental barriers include lack of choice and challenges finding appropriate programs that match physical function and meet needs to optimise participation, costs associated with raising children with disability, and lack of parental support while low self-efficacy and self-esteem are personal factor barriers that have been identified in the literature [Citation2,Citation5–8].

Most children engage in a range of sports and recreational activities in childhood, including gymnastics. Gymnastics is an overarching name for a group of sports including women’s and men’s artistic gymnastics, as well as rhythmic, aerobic, and acrobatic gymnastics. Most recreational gymnastics programs incorporate aspects from each sub-type. All forms of gymnastics lay the foundation of movement and involve learning to run, jump, flip upside-down, and swing [Citation9]. Gymnastics is a popular sport in Australia; currently, there are 800 000 people engaged with gymnastics Australia-wide with over 225 000 registered athletes across 600 different clubs, and 92% of those athletes are under the age of 12 years [Citation10]. In Victoria, gymnastics is the fourth most popular sport-related activity for children broadly with an estimated 9.6% of the population aged 0–14 years (n = 114 418) participating in gymnastics each year [Citation11].

Gymnastics programs and pathways for children with disability vary by state and territory across Australia. There are limited competitive pathways in gymnastics for athletes with physical disability in Australia compared to typically developing athletes as Gymnastics is not a Paralympic sport, nor a currently identified Commonwealth Games para-sport [Citation12]. However, athletes with intellectual disability and/or autism are eligible for Special Olympics National and World Games [Citation13].

Globally, there has been significant disability reform to improve the lives of people living with disability [Citation14]. In Australia, where this study was conducted, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was initiated in 2013 to assist individuals living with disability to participate fully within their communities. The scheme aims to provide people with disability choice and control over their services, and funding, to meet their goals [Citation15]. This may include goals related to participating in community sports, such as gymnastics. In doing so, the scheme aspires to address inequities, and barriers to, participation that people with disability face. However, to enable goal attainment and to achieve the aims of the scheme, it is important to consider the environmental and personal factor barriers and enablers identified previously, alongside context-specific barriers (in this case gymnastics-specific) so that communities are safe and inclusive environments for participation. Otherwise, the same inequities may continue to be perpetuated.

In 2014, a project investigating the benefits of gymnastics for children with disability in Victoria, Australia was undertaken [Citation16]. This project found that gymnastics promoted strength, flexibility, balance, and coordination as well as increasing children’s confidence, self-esteem, and social development. However, it did not discuss how the children came to be involved in gymnastics, and what facilitators and barriers that children with disability face to stay involved, and it has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal [Citation16].

Most previous research that tries to address low participation in physical activity by children with disability has focused on modifying body structure and function, and activity execution as opposed to addressing environmental and contextual barriers [Citation17]. In contrast, this study aimed to understand the experiences of, and pathways to participation in gymnastics for children with disability in Victoria, Australia to inform strategies to address the predominant environmental and contextual barriers. While frameworks for improving inclusion in sports broadly do exist [Citation18,Citation19], we sought to create a conceptual model reflecting these experiences and pathways that can be applied to develop more inclusive environments specific to gymnastics settings [Citation4].

Materials and methods

Study design and ethics

This study used a sequential explanatory mixed-methods study [Citation20]. First, a survey collected both qualitative and quantitative data. Then, semi-structured interviews were undertaken to further explain the themes identified from the survey responses. Qualitative data from the surveys and interviews were analysed together. This research was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee and was performed by researchers at The University of Melbourne with funding from Gymnastics Victoria (GV), the state sporting association for Gymnastics with funds received from the Victorian Government Sport and Recreation Victoria Access All Abilities scheme. Gymnastics Victoria was not involved in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, nor was the Victorian Government.

Participants

Participants were parents or legal guardians of children and young people (aged 0–25 years) with any type of disability living in Victoria who; (1) were currently participating in gymnastics, (2) had participated in gymnastics in the last three years, or (3) had attempted to participate in gymnastics in the last three years but did not go on to participate. There were no exclusion criteria. In total 58 parents participated for 59 children.

Recruitment

Stage 1: online surveys

Participants were recruited through the e-newsletters, social media accounts, and email subscription lists of organisations that promote sports participation for children and young people with disability in Victoria. These organisations included: GV, Access All Abilities Play, Disability Sport and Recreation, and Special Olympics Australia. Participants provided consent on entry to an online survey using REDcap following provision of information about the study and an opportunity to ask questions. The survey was open between September 2020 and April 2021.

Stage 2: semi-structured interviews

A selection of survey respondents who consented to be interviewed completed the second stage of this study. The response rate for interviews was calculated after the completion of the survey. Due to the high response rate of participants consenting to be interviewed (n = 31 of 58, 53%), maximum variation purposive sampling was used to include a diverse range of lived experiences [Citation21]. Where possible, we looked for variation in the following domains related to their child: rural and regional vs. metropolitan location, gender, age, type of disability, discipline of gymnastics (e.g., women’s artistic gymnastics or rhythmic gymnastics), and length of time participating in gymnastics. The potential to expand on preliminary themes interpreted from survey responses was also considered.

Data collection

Online survey

Parents provided responses to the online survey which contained questions that resulted in both quantitative and qualitative data. The survey explored different aspects of parents’ experiences of navigating pathways for their child to participate in gymnastics including the facilitators and barriers to participation, factors they considered when enrolling in gymnastics, and funding options for gymnastics participation. However, data pertaining to parental demographics was not collected. Given no previous measures or surveys were available to capture this experience, the survey questions were developed by members of the research team in consultation with two parent advisors. For the quantitative data collected, participants were asked to respond on either a Likert or sliding scale. A Likert scale was used for questions requiring discrete categorical responses. The questions enquired about aspects—such as the attitudes of peers, coaches, and the child themselves—that might be perceived to make participation easier or harder according to previous literature [Citation4]. A sliding scale was used if the question was able to be answered on a continuum, such as rating the importance of a particular factor. These questions focused on the range of factors that influenced participation in gymnastics. The qualitative data was collected via free text responses to give participants the opportunity to elaborate further on the topics covered in the quantitative questions. The survey is attached as a Supplementary File.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured qualitative interviews elaborated on the themes discussed in the survey (see Supplementary Online Material for interview guide). While the core questions were designed to elicit responses regarding the key themes identified in stage one, interviewers were able to ask additional questions to obtain more in-depth information about participant experiences.

The 1:1 interviews were conducted by two researchers (H.S. and L.H.). All interviews were recorded on the Zoom videoconferencing platform and transcribed verbatim by an external transcription service. Upon receipt of the transcripts one author (H.S.) checked them for accuracy.

Data analysis

Quantitative data was analysed using descriptive statistics with results informing the interview recruitment and questions. Analysis of qualitative data from surveys and interviews was undertaken using reflexive thematic analysis by two authors (H.S. and L.H.) [Citation22,Citation23]. This way our findings are applicable to the context and experiences of our participants. The data was analysed using a six-step process: (1) read data line-by-line, noting any initial ideas; (2) generated initial codes of features of the data related to the study aims; (3) collated codes into potential themes; (4) connections between themes were reviewed and noted; (5) defined and named themes; and (6) producing the report [Citation22,Citation24,Citation25]. Upon completion of the initial collation of coding into potential themes (step 3), the potential themes were discussed with the third author (R.T.). Once themes were further defined and named (step 5), they were once again discussed with the third author (R.T.) [Citation26]. All disagreements were resolved through negotiation by the research team. Both quantitative and qualitative data were mixed to create a conceptual model. Coding was completed using Microsoft Excel.

Upon completion of our analysis, we undertook member checking by providing the interviewees as well as two parent advisors with a summary of the findings and the conceptual model for their review and feedback. One parent responded noting that the themes were considered “too positive” and did not reflect the challenges of participation in gymnastics by children with disability. Thus, the reporting of qualitative data was revised. Final feedback was procured from two parent advisors regarding the readability of the findings.

Results

A total of 72 people responded to the invitation to participate with fifty-eight parents meeting eligibility criteria and consenting to participate for a total of 59 children. One parent completed the survey with respect to two children with disability. However, several participants did not fully complete the survey after providing consent. Despite meeting the eligibility criteria for the study, the reasons for this are unknown. The findings are reported with the number of responses in the results below.

Thirteen of the 31 (42%) participants who expressed interest in an interview were identified as interview candidates. However, five did not respond to the subsequent interview invitation. Therefore, eight interviews were conducted. Due to the time and resource constraints of the research project, capacity to interview additional respondents was limited. Further, the authors made a pragmatic judgement to cease recruitment given the interviews were undertaken following the completion of survey data. The characteristics of the children of the five participants did not differ substantially from the eight that went on to participate in the interviews.

Quantitative results

Child characteristics and gymnastics participation status

Parents’ provided information about their child and gymnastics participation. A summary of child characteristics and their gymnastics participation status is reported in . For the children described in the sample, the mean age was 10 years old (SD 4.6) and 56% (n = 25 of 45) were female. The most common diagnosis was autism spectrum disorder (n = 35 of 44, 80%). The largest proportion of children had participated in gymnastics for 1–3 years (n = 18 of 44, 41%) and most children participate in group programs (n = 40 of 43, 93%).

Table 1. Characteristics of participants’ children, and their participation in gymnastics.

Factors influencing decisions pertaining to selecting a club or class

Description of these factors can be seen in . Coaches’ knowledge regarding disability was an important factor in decision-making for parents. Additionally, the location of the club was also important with proximity to home being desirable. The option to participate in inclusive classes was also significant in selecting a class for their child.

Table 2. Factors considered by parents when selecting a club or class.Table Footnote*

Facilitators and barriers to getting and staying involved in gymnastics

Forty parents reported factors that shaped their child’s experience when participating in gymnastics once they had been enrolled.

Child-specific factors that impact on participation

Several factors specific to the child were reported to impact on the participation of children with disability in gymnastics. Most parents reported that time taken for their child to develop skills, and comparison to peers, made participation harder (n = 29, 73% and n = 28, 70%, respectively) rather than easier (n = 6, 15% and n = 2, 5%, respectively). However, responses related to physical skill level and age were more mixed with parents stating physical skill level made participation both harder (n = 22, 55%) and easier (n = 10, 25%) and 50% (n = 20) of parents stated that the child’s age was neither a facilitator nor barrier to participation.

Attitudes towards a child with disability participating in gymnastics

The attitudes of the child, parent/s, peers, and coaches were also examined. The attitudes of the adults (parents 44% and coaches 40%) were factors that made it easier and therefore more likely to positively influence the participation of the child in a gymnastics program. There was a mixed picture related to the child’s attitude and its influence on participation. However, many parents (n = 16; 40%) indicated that the attitude of the child’s peers was a factor that made it harder for children with disabilities to participate.

Available gymnastics programs

The types of gymnastics programs available and knowledge of coaches regarding disability to children with disability were important considerations for parents. Factors, such as travel time (n = 21, 53%), class size (n = 18, 45%), coach knowledge regarding disability (n = 18, 45%), and the availability of inclusive programs (n = 18, 45%) being perceived by as enablers for their child’s participation. However, a similar proportion of parents reported these same factors as making it harder for their child to participate in gymnastics (>40% for all except travel time).

Funding used to enable the child or young person’s participation in gymnastics classes

The majority (n = 30, 75%) of parents reported their child’s participation in gymnastics class was self-funded. Fifteen parents in this study sample had attempted to access funding through the NDIS for their child, of which only nine had been successful. This is in the context that 65% (n = 24) of parents reported that the additional cost of raising a child with disability made participation in gymnastics harder. Parents learned of funding provided by NDIS through word-of-mouth on social media and discussion with their child’s NDIS planner. For those who were successful, this funding was allocated under their core budget (community participation) for one-on-one support for their child within a group program.

Qualitative results

Parent responses to qualitative questions in the surveys and interviews were synthesised, from which five key themes were identified as follows. All quotes were provided by parents of children who are currently participating in gymnastics.

Tailored, accessible and supportive environments and programs make a difference

The physical gymnastics space and environment were important considerations for parents when making decisions regarding their child’s participation in gymnastics. A key feature of an inclusive environment that positively influenced participation was the consideration of sensory stimulation. Sensory stimulation, such as excessive noise, background music, and multiple concurrent classes all negatively impacted participation of children with disability. One parent stated, “the most challenging thing for us was the overwhelming sensory overload when the gym is busy” (P8; children are twins. One has participated between 1 and 3 years, and the other has participated between 6 months and 1 year).

Furthermore, large busy clubs were more likely to have high staff turnover rates leading to sudden changes in coaches for children with disability. The absence of a transition period to new coaching staff was often challenging for children with disability whose parents described a greater need for preparation for changes compared with their children’s peers. Additionally, parents stated that some coaches demonstrated a low tolerance of the behaviours of children with disability and were reluctant to adapt the session to assist in minimising the disruptive behaviours. One parent, whilst acknowledging that “in terms of feasibility it probably [wouldn’t be] possible,” (P2; child has participated between 3 and 5 years) stated that smaller group sizes with fewer concurrent classes would facilitate participation by children with disability. Specific classes for children with disability were valued by some as parents recognised that some children may experience limited participation in a “mainstream” class: “You’ve got one group of kids that will follow instructions and you’ve got one group of kids who fail to notice there are instructions” (P2; child has participated between 3 and 5 years).

Another way clubs facilitated the inclusion of children with disability was allowing or providing one-on-one support. Sometimes this provided the opportunity to participate in mainstream classes with one parent stating:

She actually has a one-on-one coach, so within the group there’s the group with the coach and then they have another coach…around to keep her on track so that she’s not distracting for the rest of the kids (P4; child has participated for >5 years)

An explicitly inclusive club culture helps young people get and stay involved

In this study, the awareness of inclusive gymnastics programs was notably absent in the parents’ responses. When searching for a program for their child parents reported a lack of knowledge about inclusive programs offered by gymnastics clubs when enquiring about enrolment. Even once the child was enrolled little information was provided regarding the inclusive practices of the club.

Despite the lack of information provided, an inclusive club culture was highly valued by parents of children with disability when selecting a club. The parents expressed that when they sensed an inclusive culture it gave the child a sense of belonging within the community. While parents acknowledged that it is not feasible for coaches to be knowledgeable about all forms of disability, being open to learning about the child was essential in creating an inclusive environment with one parent stating: “I think an inclusive attitude is more important than knowledge of disabilities.” (P3; child has participated for >5 years).

According to parents involved in this study, inclusive clubs demonstrated open communication, other children with disability participating in the class, and classes specifically for children with disability. One parent reflected on the simple actions staff implemented to support their child’s participation:

Helpers would always come up and talk at the end of a session to say how’s it going, was there anything they [child] had difficulty with, [whether we had] any ideas to help them and I think just that openness to talking about how things is going make it much easier to…stay involved and make it work well. (P3; child has participated for >5 years)

I had not thought of my son joining the club until I was doing the paperwork for my daughter to join and on it, they had a specific policy for how children with disabilities would be included and supported and it was really clear to me that the club was open to having children with disabilities and that they were able to put in a structure to make it successful (P3; child has participated for >5 years)

Inclusive club cultures assured parents that enrolling their child in gymnastics was a beneficial decision and one parent stated: “It is really heart-warming to see her out there with peers her own age and just doing all the stuff that they’re doing and knowing that she has got support from everybody.” (P4; child has participated for >5 years).

Coaches’ knowledge about engaging children with disability is valued

Parents in the surveys and interviews reported that having knowledgeable coaches was an important consideration when weighing up the suitability of gymnastics for their child. As a result, finding the right coach was often a critical factor for parents of children with disability in this study when trying to select a gymnastics program or club. However, this often resulted in a dependence on the specific coach. While there are some advantages to this coaching-gymnast relationship, parents stated a preference for a universal understanding among the coaching staff to create opportunities for their child to move between programs as necessary.

According to parents in this study, coaches need to understand the additional challenges of children with disability as they age. Parents noted that as their children aged, their participation became more difficult. Often, this was related to changes in expectations of the club which encouraged school-aged children to progress to competitive gymnastics. The increased competition in gymnastics widened the gap between children with and without disability. This gap widened with age and often resulted in the child’s withdrawal from gymnastics. Parents expressed that more needs to be done to promote individual challenge over competition and recognition over reward to encourage children with disability to remain in the sport.

What is more, coaches’ ability to modify instructions and classes to promote inclusion. Parents suggested that visual cues and additional training for coaching staff on how they can be inclusive of children with disability in their programs would be highly beneficial.

Enjoyment, recognition, and achievement facilitate ongoing participation

Parents reported that the child’s enjoyment when doing gymnastics was a key factor in their ongoing participation. Many parents shared that their children had previously attempted other activities, such as ball sports or team-based activities; but the team-based nature of the sports raised specific challenges that impacted on their enjoyment of participating. These included complex social negations and differences in skill level. Gymnastics offered an opportunity for their child to enjoy participating at an individual level while still being in a group environment akin to a team sport. This environment allowed their child to socially engage with peers of their age without the pressure of complex interpersonal interactions that were sometimes challenging to navigate. Ongoing participation was also linked to the child’s enjoyment, with one parent stating: “she enjoyed it. If she didn’t, I wouldn’t hesitate to pull her out and find something suitable for her.” (P6; child has participated between 1 and 3 years).

Recognition and celebration of their child’s progress and personal goals was a source of pride for families of children with disability. This enjoyment often motivated children with disability to continue with gymnastics. While each family had a different definition of enjoyment, the need for engaging classes that also celebrated accomplishments was a common theme reported by parents. A child’s physical skill level sometimes engendered a sense of confidence and success, but for the majority of children physical skill level was described as a barrier that only increased with age. Furthermore, parents reported that their children were disengaging when they noticed “younger children being more advanced” (P2; child has participated between 1 and 3 years). Parents also described that a child’s perception of a lack of achievements was a challenge and a barrier to ongoing participation.

Gymnastics has physical and social benefits for children with disability

The decision to enroll children in gymnastics was often largely influenced by the physical benefits of gymnastics. Parents identified that their child’s developmental delay or gross motor challenges prompted their decision to enroll their child in gymnastics classes. Parents viewed gymnastics as a sport that could assist their child to increase strength, coordination, and balance. Sometimes these challenges were recognised by a health professional, such as a physiotherapist or occupational therapist who recommended gymnastics as an activity for their child. Moreover, parents cited that gymnastics for their child provided the opportunity for children to learn transferable skills for everyday life: “the skills that they learn at gymnastics they can actually bring that into everyday life [such as] the playground at school” (P4; child has participated for >5 years).

Furthermore, some participants reported that the movements required in gymnastics, such as running, jumping, climbing, and swinging can assist in sensory regulation and management of anxiety.

The social benefits of gymnastics were also considered. Parents articulated that gymnastics promoted social interaction in a way that other team-based sports could not. Parents noted that team sports frequently required understanding complex social cues and body language which was often overwhelming for children with disability. In contrast, the structure of gymnastics classes provided the children an opportunity to listen and follow multi-step instructions—all skills that improved their social interactions and could be transferred to other social contexts. This social interaction also benefited the children’s mental health according to their parents. Parents described an increase in confidence in their children’s ability to engage socially with their peers and that their children were more willing to actively participate in play at school and community playgrounds. Parents noted that these were unexpected yet highly valued secondary benefits to the primary physical benefits that prompted the enrolment of their child in gymnastics.

The conceptual model

The findings from the study were used to inform the conceptual model and to map out the many pathways, at each stage of involvement. This model acts within the context of gymnastics in Victoria and provides us with initial evidence for what may constitute an inclusive gymnastics program for children with disability. This study identified three stages of participation for children with disability:

Choosing gymnastics

The decision to enroll a child with disability into a gymnastics program was initially motivated by the parent’s desire to facilitate the physical and social development of their child. Some parents chose gymnastics as a positive alternative to team sports. If a child had already shown interest in gymnastics skills, such as running, jumping, and climbing, or had a sibling in gymnastics parents were more likely to enroll their child in gymnastics.

Selecting a club

Parents were mindful and alert to the signs of an inclusive culture while looking for a club. A specific program for children with disability that recognised and met additional their needs was, at times, preferred but moreover, an openness and willingness to include children with disability in gymnastics programs maintained the child’s participation beyond the initial point of enrolment. While the initial motivation for the child’s enrolment may have been related to their physical health, ongoing participation led to additional social benefits for their child.

Ongoing participation

The physical space is an important consideration and often a determinant for successful participation. Gymnastics sessions that have small class sizes and scheduled at times to reduce sensory stimuli are recommended. Gymnastics coaches also need to demonstrate a willingness to anticipate and respond to any issues that may limit the child’s participation. Collaborative problem solving between club staff and families to overcome any barriers to participation was critical to the ongoing involvement of the child.

Discussion

This study identified multiple themes related to gymnastics participation by children with disability. The “Pathways to Participation” model may assist gymnastics organisations and clubs by assisting the families of children with disability navigate the challenges involved in accessing inclusive gymnastics class and creating more supportive gymnastics environments. By exploring the barriers and facilitators of gymnastics participation by children with disability we were able to synthesise the core components of gymnastics participation by children with disability. This study identified five core themes: (1) tailored, accessible and supportive environments and programs make a difference, (2) an explicitly inclusive club culture helps young people get and stay involved, (3) coaches’ knowledge about engaging with children with disability is valued, (4) enjoyment, recognition and achievement facilitate ongoing participation, and (5) gymnastics has physical and social benefits for children with disability. These themes build on previous research into physical activity participation by children with disability [Citation5,Citation8,Citation27–29].

This study provides important insights into the many factors that parents consider when choosing a gymnastics club for their child. We sought to understand the breadth of experiences, positive and negative, and to that end decided on a broad and open recruitment strategy to invite participation via organisations most typically in contact with children with disability and their families. The survey sample size was relatively small and homogenous with responses ranging from 30 to 59 participants and 80% (n = 35) being diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Therefore, we may not have captured the experiences of children with other disability. However, the rich data from the surveys and interviews combined could be synthesised to inform the conceptual model. The conceptual model remains valuable to gymnastics clubs—and potentially other sports—looking to improve their inclusive practices.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to explore the barriers and facilitators families of children with disability face when navigating the pathways to participation in gymnastics for their child. This study seeks to inform how the environment can be changed to facilitate participation by children with disability. Therefore, it provides guidance for gymnastics service providers who are seeking to improve inclusive practices to foster participation of children with disability in gymnastics programs. Given the significant changes in disability reform in Australia—such as the rollout of the NDIS—it is also timely to consider ways in which the scheme facilitates or, conversely, acts as a barrier to pathways to gymnastics for children with disability who are seeking to join and remain involved with a gymnastics program.

This study revealed that parents and guardians enrolled children in gymnastics due to the perceived physical and social benefits for their child. The benefits of physical activity for children with disability are well documented and are reflected in this study [Citation2,Citation30]. An unexpected finding of this study was that parents described the movements in gymnastics, such as jumping and swinging fulfilled sensory needs among their children. This is likely due to a high proportion of our participants having Autism Spectrum Disorder—a disorder where sensory processing is often impacted [Citation31]. Parents acknowledged the social benefits of gymnastics which allows children to be working individually in a group setting eliminating the complex interactions in team sports but maintaining social interactions. These benefits have been previously documented in the literature which has also noted that physical activity can improve the social skills of children with disability [Citation2]. Moreover, it has been shown unified sports—where children with and without disability participate together—have both physical and social benefits and also improve children’s attitudes and connections as well [Citation29]. More recently, Special Olympics Unified Sports® have been shown to benefit children with disability’s confidence, sense of belonging, and friendships [Citation28]. Sometimes parents identified the developmental and gross motor delays of their child and enrolled them in gymnastics to address these. Other times they were recommended gymnastics by a healthcare professional, such as a physiotherapist or occupational therapist. In light of these results, it may be appropriate for rehabilitation professionals to promote and assist gymnastics participation by supporting coaches and NDIS applications.

This study found that the child’s attitudes towards gymnastics and their enjoyment were key factors in participation. A child’s physical skill and competence in gymnastics was reported as a barrier and a facilitator depending on the child. However, most parents felt that it was a barrier and that it increased with age. This is echoed in a systematic review that stated that as children aged the disparity in abilities between them and their peers increased. However, if they tried to participate with people who were developmentally equivalent, children with disability were often too physically strong [Citation32].

Further, the child’s enjoyment was important in deciding whether to participate in gymnastics. Several parents stated that they enrolled their child in gymnastics because they showed an affinity for movements associated with gymnastics, such as swing and climbing, and that their child continued gymnastics because they enjoyed it. Parents in this study reflected that children were benefited by increased self-confidence and opportunity for success.

There was a concerning disparity in knowledge and information held by parents in this study about accessing funding for their child’s gymnastics class. The research evidence is clear that families bear additional costs when raising a child with disability [Citation33,Citation34]. The exact fees and costs to the parents were not collected and it is acknowledged that the fees may have been a factor of non-participation that was not captured in this study. It is therefore important for families to understand what financial support may be available for their child to engage in activities, such as gymnastics. With the introduction of the NDIS into the disability landscape in Australia, it will be important to facilitate these pathways in the future.

Further research with a more heterogenous cohort would be beneficial to understand whether these findings remain relevant when considering wider experiences of disability. Our recruitment strategy is unlikely to have captured many participants who are no longer participating in gymnastics given it was largely through sports organisation. Given the known differences in perceptions between parents and children with disability in participation research [Citation35], future work in this area should prioritise capturing children’s experiences. The lack of parental demographics captured is also a limitation of this study. Collection of data related to parental and family characteristics, the perspective gymnastics coaches and club owners as well as young people with disability who currently and no longer participate in gymnastics would deepen our understanding of how to improve existing and new gymnastics programs. In saying that, this study does provide a greater understanding regarding participation in gymnastics of children with disability, data that has been lacking for gymnastics and other popular sports for children with disability in Australia [Citation10].

This study collated data that was used to demonstrate the pathways families are currently using to participate in gymnastics. The model, “Pathways to Participation” () provides a useful tool for gymnastics organisations and clubs to conceptualise and assess program inclusivity or to develop new accessible programs. The model was developed using the real experiences of families with children with disability and thus provides clubs and organisations with meaningful data specific to the gymnastics community.

Figure 1. Pathways to participation in gymnastics by children with disability: a conceptual framework.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (94.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Gymnastics Victoria and Disability Sport and Recreation for their contribution to this project both in funding and assistance with the project, respectively. We also acknowledge the input of the two parent advisors at various stages of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Where consent has been provided by individual participants, the data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [RT]. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed BS, Lamy M, Cameron D, et al. Factors impacting participation in sports for children with limb absence: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(12):1393–1400.

- MacEachern S, Forkert ND, Lemay J-F, et al. Physical activity participation and barriers for children and adolescents with disabilities. Int J Disabil Dev Educ. 2022;69(1):204–216.

- McCarthy N, Hall A, Shoesmith A, et al. Australian children are not meeting recommended physical activity levels at school: analysis of objectively measured physical activity data from a cross sectional study. Prev Med Rep. 2021;23:101418.

- World Health Organisation. International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva: world Health Organization; 2001.

- Shields N, Synnot A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:9.

- Boman C, Bernhardsson S. Exploring needs, barriers, and facilitators for promoting physical activity for children with intellectual developmental disorders: a qualitative focus group study. J Intellect Disabil. 2023;27(1):5–23.

- Siyi Y, Taijin W, Tianwei Z, et al. Barriers and facilitators of physical activity participation among children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities: a scoping review. Healthcare. 2022;10(2):233–233.

- Wright A, Roberts R, Bowman G, et al. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation for children with physical disability: comparing and contrasting the views of children, young people, and their clinicians. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(13):1499–1507.

- Gymnastics Victoria. What is gymnastics? 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 11]. Available from: https://vic.gymnastics.org.au/VIC/Discover_Gymnastics/What_is_Gymnastics_/VIC/Join_Us/What_is_Gymnastics.aspx?hkey=df9b6efc-4a96-4a1c-ad47-44002b43dc3f

- Gymnastics Australia. Gymnastics Australia: About Us Australia: Gymnastics Australia; 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.gymnastics.org.au/about-us

- Australian Sports Commission. Ausplay: National Sport and Physical Activity Participation Report. Australian Government; 2022.

- Mannion T. Nine Para-sports confirmed for Victoria 2026 Australia; 2022 [cited 2023 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.paralympic.org.au/2022/10/nine-para-sports-confirmed-for-victoria-2026/#:∼:text=Para%2Dshooting%20will%20appear%20for,table%20tennis%20and%20Para%2Dtriathlon

- Special Olympics Australia. Sport and competition; 2016 [cited 2023 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.specialolympics.com.au/sport

- United Nations. United Nations Disability and Inclusion Strategy; 2019.

- National Disability Insurance Agency. What is the NDIS? 2021 [cited 2022 Jul 11]. Available from: https://www.ndis.gov.au/understanding/what-ndis

- Campain R. Understanding the benefits of gymnastics for children with disability. Box Hill: Scope; 2014.

- Reedman S, Boyd RN, Sakzewski L. The efficacy of interventions to increase physical activity participation of children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(10):1011–1018.

- Legg D, Higgs C, Douer OF, et al. A framework for understanding barriers to participation in sport for persons with disability. Palaestra. 2022;36(1):13–20.

- Play by the Rules. The 7 pillars of inclusion Australia; 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.playbytherules.net.au/resources/videos/the-7-pillars-of-inclusion

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd ed. London: SAGE; 2017.

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–544.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Thorne SE. Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2016.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Novel insights into patients’ life-worlds: the value of qualitative research. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(9):720–721.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589–597.

- Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2015.

- Barr M, Shields N. Identifying the barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2011;55(11):1020–1033.

- Rodriquez J, Lanser A, Jacobs HE, et al. When the normative is formative: parents’ perceptions of the impacts of inclusive sports programs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10889.

- McConkey R, Dowling S, Hassan D, et al. Promoting social inclusion through unified sports for youth with intellectual disabilities: a five-nation study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2013;57(10):923–935.

- Driscoll SW, Conlee EM, Brandenburg JE, et al. Exercise in children with disabilities. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2019;7(1):46–55.

- Ausderau K, Sideris J, Furlong M, et al. National survey of sensory features in children with ASD: factor structure of the sensory experience questionnaire (3.0). J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(4):915–925.

- McGarty AM, Melville CA. Parental perceptions of facilitators and barriers to physical activity for children with intellectual disabilities: a mixed methods systematic review. Res Dev Disabil. 2018;73:40–57.

- Bourke-Taylor H, Cotter C, Stephan R. Young children with cerebral palsy: families self-reported equipment needs and out-of-pocket expenditure. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(5):654–662.

- Anderson D, Dumont S, Jacobs P, et al. The personal costs of caring for a child with a disability: a review of the literature. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(1):3–16.

- Dada S, Andersson AK, May A, et al. Agreement between participation ratings of children with intellectual disabilities and their primary caregivers. Res Dev Disabil. 2020;104:103715.