Abstract

Purpose

Stroke survivors regularly report experiencing boredom during inpatient rehabilitation which may detrimentally affect mood, learning and engagement in activities important for functional recovery. This study explores how stroke survivors meaningfully occupy their non-therapy time and their experiences of boredom, to further our understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Methods

Secondary analysis of transcripts from semi-structured interviews with stroke survivors exploring activity during non-therapy time. Transcripts were coded and analysed using a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive thematic analysis, guided by a published boredom framework.

Results

Analysis of 58 interviews of 36 males and 22 females, median age 70 years, revealed four main themes: (i) Resting during non-therapy time is valued, (ii) Managing “wasted” time, (iii) Meaningful environments support autonomy and restore a sense of normality, and (iv) Wired to be social. Whilst limited therapy, social opportunities and having “nothing to do” were common experiences, those individuals who felt in control and responsible for driving their own stroke recovery tended to report less boredom during their rehabilitation stay.

Conclusion

Creating rehabilitation environments that support autonomy, socialisation and opportunities to participate in activity are clear targets to reduce boredom during non-therapy time, increase meaningful engagement and possibly improve rehabilitation outcomes post-stroke.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Stroke survivors with a low sense of autonomy are at greater risk of boredom and may benefit from person-centred strategies to support participation in meaningful activities during non-therapy time whilst undertaking inpatient rehabilitation.

Review and reduction of paternalistic practices within traditional models of care, to increase patient autonomy, may empower stroke survivors to drive their own activity and reduce boredom.

The redesign and reorganisation of rehabilitation environments to increase opportunities for socialisation and access to nature and the outdoors may reduce boredom during inpatient rehabilitation.

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide [Citation1]. In Australia, around one quarter of people that have a stroke are admitted to inpatient rehabilitation units where they can participate in rehabilitation therapies to relearn skills and regain independence with the goal to return home [Citation2]. Inpatient rehabilitation therapy programs are typically structured around scheduled individual therapy sessions (e.g. physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy) and sometimes group-based sessions. Stroke clinical guidelines recommend participating in as much scheduled therapy and active task practice as possible [Citation3] as higher doses are linked with better functional recovery post stroke [Citation4,Citation5]. However, time spent in scheduled therapy is typically low [Citation6] and many stroke survivors find it difficult to drive their own practice during non-therapy time [Citation7]. Observational research indicates stroke survivors spend the majority of their non-therapy time physically, cognitively and socially inactive [Citation8] and many, about two in five, have reported to be highly bored during inpatient rehabilitation [Citation9]. Experiencing boredom is not only detrimental for a person’s mood, cognitive resources, motivation and effort, but has wider implications for impeding on their ability to engage in therapeutic activities important for learning and facilitating functional recovery after stroke [Citation9,Citation10].

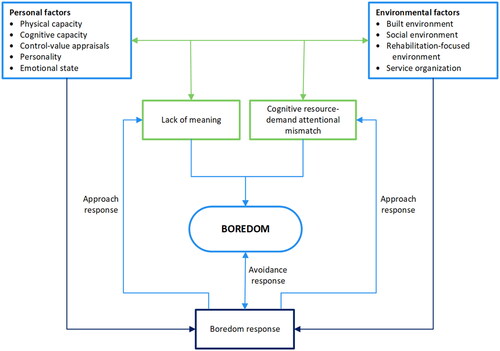

Boredom arises when activities lack meaning and/or are not optimally matched with available cognitive resources [Citation11]. A range of personal factors (e.g. physical capacity, cognitive capacity, control-value appraisals, personality and emotional state) and environmental factors (e.g. built environment, social environment, rehabilitation-focused environment and service organisation) may contribute to boredom during inpatient rehabilitation [Citation9]. The interaction of these factors has been proposed to contribute to the maintenance of boredom by constraining stroke survivors from initiating or switching activities in response to being bored [Citation9].

Whilst the experience of post-stroke depression and a lack of socialisation have been associated with high levels of boredom during inpatient rehabilitation, being inactive was not [Citation9]. The latter may be related to a desire for rest and relaxation during non-therapy time [Citation12], but on the whole, how stroke survivors prefer to meaningfully occupy their non-therapy time and their experience of boredom is poorly understood. The aim of this exploratory study was to explore stroke survivors’ experiences of non-therapy time to better understand what can lead to people becoming bored. Our specific research questions were:

How do stroke survivors meaningfully occupy their non-therapy time and what are their experiences of boredom?

What factors affect how stroke survivors occupy their non-therapy time and contribute to their experience of boredom?

Methods

Study design

This study involved secondary analysis of interview data gathered in the cluster non-randomised controlled trial AREISSA [Citation13]. Interviews conducted in AREISSA were completed to understand stroke survivors’ perceptions of factors that helped or hindered their engagement in physical, cognitive or social activity during non-therapy time whilst undertaking inpatient rehabilitation [Citation14]. Further details of patient recruitment, setting and a copy of the interview guide for the original study have been published previously [Citation14]. Initial findings indicated varying levels of boredom among stroke survivors, which provided the impetus for a more focused analysis of boredom in the current study. Interviews in AREISSA were conducted between February 2015 and June 2018. Ethics was approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Committee and governing research ethics committees at all participating sites (HNE HREC 13/09/18/4.06) for the original study and subsequent studies.

Participants

Participants attended one of four metropolitan inpatient rehabilitation units in Australia. Stroke survivors were eligible for inclusion in the interview component of AREISSA if they had a confirmed stroke <4 weeks, a pre-morbid modified Rankin Scale score ≤2 (minimal/no disability), were able to stand with the assistance of two people or less during their physiotherapy session, were able to follow a one stage command, and had a predicted length of stay of ≥10 days. Exclusions were a diagnosis of pre-existing dementia, any behavioural or medical issue that limited safe participation in standard rehabilitation, and severe communication impairment which prevented effective communication as judged by their treating speech pathologist.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by trained research assistants (three female speech pathologists) with the participants in their own home or via telephone up to two weeks following discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Interviews utilised an interview guide developed by an expert multidisciplinary team and collected participants’ perspectives of their rehabilitation experience, including their thoughts on the physical environment; opportunities for physical activity, thinking-based leisure or social activities, and directly questioned participants on their experience of boredom. A copy of the interview guide is freely available to download as a supplement attached to the original study [Citation14]. Interviews lasted on average 35 min (range 12 to 121 min). All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

We completed a secondary data analysis with a focus on understanding stroke survivors’ experiences of non-therapy time and what can lead to people becoming bored. Analysis was completed by KK who has a clinical background as a physiotherapist in stroke rehabilitation and was working at one of the rehabilitation units involved in AREISSA on commencement of this study.

The original 58 interview transcripts were imported into NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd) for analysis. Analysis involved a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and reflexive process of thematic analysis within a constructivist paradigm [Citation15–17]. This was an iterative process that involved data familiarisation and initial inductive data coding, in which descriptive codes were assigned to portions of text to capture observations or facets of meaning. Following the development of a conceptual boredom framework by our research team as part of another study [Citation9], we returned to the data and completed a second round of coding using a deductive approach informed by the boredom framework, to deepen our understanding and interpretation of the data. The boredom framework describes how the interaction of personal factors (including appraisals, stroke-related impairments) and environmental factors of the rehabilitation unit may give rise to boredom when a situation lacks meaning or does not sustain one’s attention. Failure to respond adequately (e.g. continuing with the same activity) leads to boredom being sustained (). The categories within the framework served as a prompt to identify and code salient concepts within the dataset. Additionally, the framework provided a guide to reorganise previous inductive driven codes and check and link concepts to understand how certain factors described in the data may contribute to boredom. Codes were not predefined and were identified throughout the analytical process.

Figure 1. A conceptual framework of boredom in stroke rehabilitation was used to identify salient concepts with the dataset and assist with data interpretation. From Kenah et al. (2023). Depression and a lack of socialization are associated with high levels of boredom during stroke rehabilitation: an exploratory study using a new conceptual framework. Neuropsychol Rehab, 33(3):497–527, reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis Ltd., http://www.tandfonline.com).

Participants who reported being bored or not were identified during initial coding based on their response to the question “Were there times when you were bored?”. Contributing factors to boredom were identified directly from participants’ explanations of why they were or were not bored and more implicitly through a deep interpretative process of analysis grounded in people’s discussions of their experience and comparisons across participants.

Initial themes were generated and collated into a shared document that contained the contributing codes for each theme and a representative quote for each code. This document informed discussion with co-authors (HJ and MT) to refine, define and name the final four overarching themes that captured patterns of shared meaning united by a central concept and were consistent with the data. Additionally, study rigour was assured through meetings with a co-author (MT) with extensive experience in undertaking and teaching qualitative research methods. Meetings involved review and discussion of selected transcripts to sense-check ideas and different interpretations of the data. This process assured beliefs and assumptions were challenged and observations were not overlooked during the coding process, enhancing the overall level of interrogation of the data.

Results

The 58 participants included in the study had a median age of 70 years (interquartile range (IQR) 55 to 80), the majority were male (62%), and just over half (53%) could walk short distances independently with or without an aid and about one third had aphasia ().

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Analysis of interview data revealed four main themes in relation to how participants experienced non-therapy time and subsequent factors that contributed to the experience of boredom. The complete transcripts of all 58 interviews were taken into account when constructing themes, although several participants with significant cognitive impairment provided limited data for analysis. Only key exemplar quotes are reported below.

THEME 1: resting during non-therapy time is valued

Many stroke survivors valued having downtime and breaks in their therapy schedule, which provided opportunities for needed rest and relaxation. Rest was commonly reported to be needed to combat stroke-related fatigue and recover from “busy” therapy schedules which left many stroke survivors with low energy and motivation reserves.

…there wasn’t an awful lot of free time… Some days I’d have two sessions of physio, one of OT [occupational therapy] and one of gym. And by the end of that day I was absolutely worn out. I’d probably be in bed by six o’clock. (P22, male, 67 y, moderate stroke)

Fatigue was often reported to be exacerbated by environmental factors such as lights and noise that meant several participants …didn’t hardly get any rest at night… (P19, female, 58 y). Whilst noise from other patients was accepted to be a common downside of shared patient rooms, participants were particularly frustrated by what they deemed as carelessness or unnecessary interruptions overnight (e.g. loud conversations at the nurses station, slamming doors or interruptions to complete observations).

Many stroke survivors described rest during the day to be therapeutic and essential for their recovery and managing fatigue. However, perceived norms and staff attitudes sometimes led to feelings of guilt about wanting to rest.

The other ladies said, oh, look, you’re not supposed to be on your bed during the day, you’re supposed to be sitting in a chair… So there was different theories on how to recover, I suppose, from different nursing staff. (P38, female, 50 y, mild stroke)

Many participants also found that it was …hard to concentrate for a long time… (P33, male, 30 y, mild stroke) following their stroke, either as a result of fatigue or stroke-related cognitive changes. Consequently, they commonly opted for accessible activities with low cognitive loads (e.g. watching TV) over more cognitively demanding activities (e.g. reading) to occupy their non-therapy time.

Sometimes stroke survivors described pleasure in being able to relax, unwind and simply “do nothing” which was not driven by fatigue. This appeared to be more apparent in older stroke survivors, some of whom reported more sedentary routines prior to their stroke. In contrast, one younger participant appreciated the opportunity in rehabilitation to just slow down (P6, female, 46 y, moderate stroke) from her normal busy lifestyle.

THEME 2: managing “wasted” time

Whilst many participants valued opportunities for rest, for others there was just too much downtime in their therapy schedule which contributed to boredom and frustration that there was “nothing to do” and they were “wasting time” in rehabilitation. Such perceptions were commonly driven by the belief that scheduled therapy was the mainstay of rehabilitation. Many participants correlated the amount of therapy and effort applied in therapy sessions with stroke recovery, contributing to dissatisfaction when the amount of scheduled therapy was less than expected. Alongside the belief that therapy was imperative for stroke recovery, some stroke survivors ascribed ward activities to have limited therapeutic value.

They did leave behind an iPad for me to do some games, but I did not play. Maybe they have more activities for exercise. I only had [therapy] twice a day and sometimes they forget. So it’s a waste of time. (P55, female, 52 y, mild stroke)

Similarly, limited therapy on weekends meant boredom typically peaked during this time.

Weekends were the worst part because there’s just nothing from when you woke up Saturday morning until Monday morning. (P22, male, 67 y, moderate stroke)

How stroke survivors managed extended non-therapy periods on weekdays and weekends often delineated the pervasiveness of boredom experienced. Use of passive avoidance strategies to cope with boredom during non-therapy time, such as waiting or sleeping, often cemented the boredom, contributed to poor sleep hygiene and were perceived to be unhelpful in the long-term.

When there was nothing else to do, you feel pretty bored. Yeah. I think sleeping most of the time. So at night, can’t sleep because you sleep during the daytime. (P56, male, 81 y, mild stroke)

These avoidance strategies tended to be used by stroke survivors who perceived that they had little autonomy and whose time use was driven by their therapy schedule.

Just watching the time click by…waiting for time for your roster to come round or – yeah, it’s a boring old life in hospital. (P29, male, 46 y, moderate stroke)

Not all participants’ behaviour appeared to be dependent on these schedules, with many reporting non-therapy time as an opportunity for practice and to participate in activities that they believed would be beneficial for their recovery.

Bored was something I never felt to be honest. I tried to get better. I really tried to use the time there to get better… So I did a puzzle one-handed, three puzzles one-handed, just because I could… (P9 male, 62 y, mild stroke)

Such attitudes did not automatically carryover despite engagement during therapy sessions; many participants approached therapy sessions with enthusiasm but appeared to struggle with the self-management of rehabilitation outside of such sessions. Stroke survivors that were able to reframe “wasted” non-therapy time and take charge of their own recovery appeared to be driven by an internal locus of control, a nothing motivates you if you don’t motivate yourself (P11, male, 66 y, moderate stroke) type attitude. Such beliefs were aided by knowledge that activity drives stroke recovery and an understanding of specific exercises and ward activities that they could access.

What you do. I mean, you want to get better? You’re not there for a holiday. There is no resort. That’s what a lot of people think. You know, bring me food – no, you’ve got to go and get it. Help yourself. (P34, male, 64 y, mild stroke)

This profound sense of agency appeared to be an important personal characteristic in warding off boredom.

THEME 3: meaningful environments support autonomy and restore a sense of normality

Hospital environments that enabled the practice of everyday activities and supported autonomy were reported to help restore a sense of normality and avert boredom. Everyday activities such as watching television, reading the newspaper, listening to the radio, and accessing the internet, social media and also emails, provided an important connection to the outside world whilst in hospital. Functional activities, such as the ability to make a cup of tea or coffee or reheat a home-cooked meal increased participants’ sense of normality and supported preparation to return home. Integration of activities and interests that participants enjoyed pre-stroke into their daily routines (e.g. knitting, yoga or involvement with volunteer organisations) also provided meaningful forms of occupation during their non-therapy time. One participant was particularly creative in how he incorporated his interest in dance into his non-therapy time:

I spent a lot of time playing music, listening to the tempo that could be exercise from a wheelchair, and…I prepared a 30 page book of all the dance steps that could be exercise from a wheelchair. And I spent six weeks doing that. (P56, male, 81 y, mild stroke)

Yeah, so if someone says that there’s no activities and things, that’s down to them because they’re all there. You just get yourself down to that common room, the TV is there, the books are there, the games are there, out into the open air area is there. What more can you expect in a hospital? (P47, male, 56 y, mild stroke)

However, for others, opportunities to perform everyday activities were not always afforded, due to the structured, clinical and paternalistic nature of the hospital environment.

I wanted to get out [of hospital] as soon as I could, because I think you do more at home, just subconsciously, walking around, bending, making a cup of tea, all the different things that you do. Instead of in a hospital situation where it’s all a bit structured… (P8, male, 69 y, moderate stroke)

For example, hospital routines and therapy timetables were perceived by stroke survivors to centre around the day-to-day management needs of the busy staff who were juggling multiple demands, rather than serving the best interests of the stroke survivor. As a result, patient choice, flexibility and decision-making about showers, meals, therapy and bed times were frequently compromised.

So it’s like your tea comes at 5:15, who eats tea at 5:15?. Two hours of daylight left and you’re wasted sitting in bed eating a meal. But it’s hospital… I used to have my last feed at 8 and then the lights go out, like prison… I can understand the nurses actually need to go ‘Phew thank god for that, we’re rid of them for a little bit.’ (P11, male, 66 y, moderate stroke)

Hospital rules, in particular falls prevention policies and subsequent overprotection by staff, also reinforced sedentary and compliant patient behaviours (e.g. the perception that they must stay in their bedroom or inform staff of their whereabouts at all times). Such submissive behaviours restricted patient mobility, control and participation in everyday activities.

[Nursing staff] say ‘You can’t walk, no you can’t do this, you can’t do that.’ …But nothing that show you how to do the right procedure so I can one day become independent… (P18, male, 64 y, moderate stroke)

Along with the need to conform to the routines and rules of the hospital environment, a loss of independence with mobility commonly limited stroke survivors from being able to freely leave their bedroom and participate in meaningful activities to occupy their non-therapy time.

I kept to the room; I didn’t walk around much on my own. Actually, the greater part of my stay I was not allowed to walk on my own, I only went for walks when my husband came to visit…so I was pretty much restricted until he came in. (P23, female, 68 y, moderate stroke)

Stroke-related mobility impairments could be negated through the provision of one-arm drive or power wheelchairs which markedly increased stroke survivors’ independence and autonomy, but did not appear to be routinely provided to all participants with mobility limitations.

Once I got the electric wheelchair…I did whatever I liked. I had my own choice and if I wanted to go I just got in the wheelchair and went. (P22, male, 67 y, moderate stroke)

The built environment of the rehabilitation unit was also found to support or hinder patient activity and autonomy and therefore experience of boredom. Many participants ascribed a sense of security and comfort with being in their room, which was likened to a second home (P27 male, 85 y, mild stroke). Spending time in their room surrounded by their own belongings allowed participants to create their “own space,” provided privacy and a place they could retreat to for needed rest. Single rooms in particular, in which participants had greater control over their environment (e.g. television on or off, lights, door open or closed) increased participants’ sense of autonomy but this often appeared to be at the expense of increasing social isolation and inactivity.

Access to modern, attractive and well-resourced communal spaces with comfortable furnishings and artwork could provide an incentive to leave the comfort of patient rooms and fostered a sense of normality and detachment from institutionalisation.

It didn’t even feel like a rehab hospital, it felt like a nice place to be really. (P44, male, 52 y, mild stroke)

Quiet and semi-private communal spaces were particularly valued as they provided places to meet with visitors. Designated spaces to meet with family which had access to kitchen facilities and toys to entertain young children or grandchildren, further enhanced the quality of visitor interactions and sense of normality.

Patient rooms and communal areas with large windows, sunshine and pleasant views of nature and nearby roadways helped participants to feel connected to the outside world and more grounded. Being able to venture outside further provided an escape from the hospital environment and means to connect with nature and admire the peacefulness and beauty of the surrounding gardens.

It was nice to breathe the air… and smell the flowers and realise there’s an outside world after all, the sun shines and all that. (P9, male, 62 y, mild stroke)

However, outdoor spaces were frequently reported to be difficult to access independently by the stroke survivor due to the distance from the rehabilitation ward, wayfinding issues or poor wheelchair accessibility (e.g. steps, curbs, narrow and undulating paths, or an inability to open external doors on own). Inclement weather and a lack of outdoor options if it was cold or wet further restricted participants from spending time outdoors during their non-therapy time.

THEME 4: wired to be social

Social interaction with other patients, visitors and staff was not only a positive distraction that appeared to help avert boredom during non-therapy time, it also appeared to support self-identity and wellbeing, laying the foundation for stroke recovery.

It’s amazing how important conversation is; as important as using your affected hand to do simple tasks… (P44, male, 52 y, mild stroke)

Authentic therapeutic relationships with staff who listened and took the time to get to know participants as individuals gave meaning to their rehabilitation stay. Staff with positive, caring and supportive attributes helped improve stroke survivors’ mindset, motivation and hope for recovery.

I woke up one morning and I was in a bad place…but before I knew it [name], one of the very senior nurses, was sitting on the side of my bed holding my hand and she sat there and talked to me for about an hour about how I was feeling. And I was just overwhelmed by that caring attitude. (P22, male, 67 y, moderate stroke)

Staff that were attentive, efficient and accountable were also valued, particularly when many participants were dependent on staff for basic needs (e.g. toileting). However, participants often perceived staff to be busy and unavailable. Interactions with staff were often described to focus on the essential task at hand (e.g. taking observations, giving medications) with little time for deeper conversation. Some participants avoided non-essential requests of staff as they didn’t like troubling them because they’re so busy (P10, male, 82 y, mild stroke) or did not want to be seen to be “demanding”. Such self-sacrificing attitudes contributed to inactivity and passive strategies to cope with boredom during non-therapy time.

Visiting family members were described to provide vital emotional and practical support to stroke survivors during their rehabilitation stay. Encouragement and support from family members helped boost morale and motivation. Practical assistance was provided through assisting with caregiving (e.g. personal care, feeding), exercises and facilitation of activity on and off the ward (e.g. playing board games, visiting the onsite café, walking through the gardens) that helped participants to meaningfully occupy their time.

If I hadn’t got visitors I would have gone crazy. Just laying there hour after hour. (P28, male, 85 y, mild stroke)

Opportunities to establish meaningful relationships with other patients, camaraderie and the formation of friendships helped stroke survivors to navigate inpatient rehabilitation. Observing others improve, sharing experiences and encouraging one another was an important source of motivation and provided hope for recovery. Shared patient rooms, communal mealtimes and therapy sessions all provided opportunities to meet other patients, bond over shared experiences and meaningfully occupy their time.

I just sat in the room and talked to the ladies, it was great. It was a real social sort of hub - we had people almost dropping in on our room just to have a chat type thing. (P38, female, 50 y, mild stroke)

However, other stroke survivors lamented about the lack of social opportunities that were available. This sense of isolation and loneliness was heightened in single patient rooms as most people stayed in their rooms, kept to themselves (P31, male, 54 y, mild stroke).

However, not everyone wanted more social activity. Those who identified as shy or an introvert often felt more comfortable on their own. Some younger participants felt they could not relate with the other older adults present on the ward due to the age gap (P40, male, 21 y, moderate stroke).

Discussion

Analysis of interviews with stroke survivors indicated varying levels of boredom during inpatient rehabilitation. Resting as well as participating in activities that were perceived to promote functional recovery, restore a sense of normality or provide social connection, were all considered to be meaningful activities during non-therapy time. However, prolonged periods of rest or inactivity led stroke survivors to become bored and frustrated that they were “wasting time” in rehabilitation. Personal factors contributing to the experience of boredom included dependence with mobility and an external locus of control leading to an inability to take charge of one’s recovery and how they spent their non-therapy time. The physical design and the paternalistic nature of the rehabilitation unit (i.e. the rigid structure and rules of the rehabilitation unit and perceived overprotective staff attitudes) were environmental factors which appeared to restrict autonomy, socialisation and engagement in meaningful activities and contributed to people experiencing boredom. Conversely, well designed spaces and caring and empowering attitudes of rehabilitation staff appeared to support autonomy and meaningful engagement during non-therapy time and reduce boredom.

Results from this study support the notion that inactivity does not necessarily lead to boredom, validating previous quantitative findings [Citation9] and building on the findings of Purcell et al. [Citation12] that stroke survivors need and value time for rest and relaxation to manage stroke-related fatigue. However, despite wanting to rest, some stroke survivors found themselves second guessing whether it was acceptable to pursue rest on the rehabilitation unit. These findings suggest an individualised approach to support stroke survivors to manage their fatigue is needed, in the absence of evidence to guide fatigue management [Citation18]. Such approaches should legitimise rest and incorporate therapeutic ways to rest that don’t necessarily involve sleep (e.g. meditation, mindfulness, listening to music).

Whilst some rest was valued during non-therapy time, others complained of boredom and desired more activity or simply slept because they were bored. Results indicated a wide variation in participants’ sense of personal responsibility, motivation and competence to direct their own activity outside of therapy sessions. Underlying subjective interpretation processes are thought to be a key factor in the emergence of boredom [Citation19]. In this study, those that were bored tended to interpret non-therapy time negatively, struggling to find value and assessing it to be “wasted time”. They often focused on the losses (i.e. there was not enough therapy) and appeared to be powerless in driving their own activity. In contrast, those that reported low levels of boredom described boredom to be a consequence of their own actions, focused on the opportunities and took responsibility to initiate their own activity during non-therapy time. These interpretations highlight the central role that autonomy, feeling in control and the perceived value of activities, described as control-value appraisals in the psychological literature, have in the development and maintenance of boredom [Citation9,Citation10]. Subjective interpretations of situations are not fixed [Citation19]. Self-management interventions focusing on enhancing autonomy and competence to empower stroke survivors to take charge of their own recovery have proven to be effective in improving self-perceived stroke recovery in community dwelling stroke survivors [Citation20]. Application of self-management principles in inpatient rehabilitation may support the development of internally motivated mindsets and behaviours to improve patient engagement. A starting point to promote more active behaviours during non-therapy time, as indicated by participants in this study, may be to routinely orientate the stroke survivor and their family to the facilities available in the rehabilitation unit, educate about stroke recovery and discuss expectations of continuing practice outside of therapy sessions.

Person-centred care, in which the stroke survivor plays an active role and is considered as a partner with capabilities and resources to contribute to their care, is widely recognised to be at the core of quality stroke rehabilitation service delivery [Citation21]. However, in practice, our study and others have found that the capacity of stroke survivors to exercise autonomy is frequently inhibited by disempowering staff attitudes and behaviours shaped by staff time pressures, rules/policies, traditional roles, and the organisational structure of the healthcare environment [Citation22,Citation23]. For example, the risk of falls and preventing harm from falls as patients recover following stroke is an inherent part of inpatient rehabilitation care. However, prohibiting stroke survivors from engaging in autonomous therapeutic activities that enhance their recovery as part of a blanket approach to managing falls risk may cause other forms of harm [Citation24]. Patient autonomy may be supported through shared decision making, allowing stroke survivors to make informed choices about engaging in higher-risk activities that they may wish to practice to promote independence as part of their recovery [Citation24]. Such relational orientations to care, that prioritise the development of therapeutic relationships, building trust and patient empowerment, are the cornerstone of person-centred care [Citation25]. However, formation of therapeutic relationships often appeared to be compromised in our study as staff were perceived to be too busy and needing to attend to other tasks, contributing to patient disempowerment and boredom. Infrequent information sharing and a lack of feedback and validation from rehabilitation staff has also been reported to hamper engagement in stroke rehabilitation [Citation26]. Conversely, when positive and caring therapeutic relationships were able to develop, they appeared to play a critical role in empowering patients within the health system in our study. There is a need to foster a culture where flexible, caring and compassionate staff attitudes and behaviours that promote patient autonomy are upheld and organisational priorities are better aligned with the outcomes, values and experiences that matter most to patients [Citation21,Citation25].

Harnessing social capital (families, other patients and volunteers) is another strategy to reduce the boredom and isolation reported by stroke survivors, increase social connection, support autonomy and promote engagement in meaningful occupations during non-therapy time. Families provided important access to recreational activities in our study (e.g. playing games, visiting an onsite café). Additionally, including families in the processes of care through training family members to assist with exercises [Citation27] or teaching of bedside handling skills, may support patients and families’ involvement in the recovery process and their emotional wellbeing [Citation28]. Volunteer programs can be used to augment therapy exercise programs, facilitate recreational activity or support communication opportunities for people with aphasia [Citation29,Citation30]. Additionally, peer support programs provided by former stroke survivors can provide valuable social, emotional, informational, and experiential support to stroke inpatients that may support engagement [Citation31]. Fostering social interaction between patients through groups, shared meals and access to communal spaces, can also facilitate stroke survivors to develop new social networks and friendships that provide enduring support throughout their rehabilitation stay.

Rehabilitation facility design could also be leveraged to support socialisation, reduce boredom and promote patient empowerment [Citation32]. Considered design of communal spaces is needed to provide opportunities for patients to socialise with other patients and visitors outside their rooms [Citation27]. Results from our study indicated that many patients valued quiet locations to meet privately with visitors away from their rooms, suggesting that the design of communal spaces to support visitors may differ from those spaces designed to promote social interaction between patients. Attention to the design of outdoor spaces is also warranted given many participants highlighted the therapeutic value of spending time outdoors and being able to connect with normal life outside of the rehabilitation unit. Stroke survivors commonly identified the inaccessibility of outdoor spaces as a problem, but the location and design of outdoor spaces likely also contributed to their infrequent use. For example, stroke survivors have been observed to spend greater amounts of time in a winter garden (an enclosed glass space with places to sit and views of the outdoor garden) co-located next to a coffee shop compared with other communal spaces [Citation27]. Results from our study suggest that the creation of accessible, attractive and inviting all-weather outdoor spaces or bringing outdoor elements inside are important considerations for rehabilitation facility design – an area in need of research in the context of stroke rehabilitation [Citation32].

Strengths, limitations and future directions

A limitation of our study is that the data analysed was originally collected to answer a research question which sought to understand the reasons stroke survivors found it difficult or easy to engage in physical, cognitive and social activity during their time on a rehabilitation ward. Hence, whilst participants were questioned about their experience of boredom in the original interview, the interview guide did not focus on understanding factors that specifically contributed to this experience. Nevertheless, the interview structure allowed participants to provide rich accounts of their experiences of boredom, prompting a reanalysis to explore this concept in more depth, a common approach in qualitative research [Citation33]. Another potential limitation of this study is that interviews were conducted after discharge (within two weeks) from rehabilitation. This may have limited recall of certain events but allowed participants time to reflect on their overall experience and freely discuss any negative experiences.

The recruitment of a large number of participants across multiple stroke rehabilitation settings in Australia is a strength of the study and ensures that these findings are not limited to the unique design and organisational structure of individual rehabilitation units. Recruitment of people with aphasia and interviews conducted by a speech pathologist support inclusivity and increase the relevance of our research findings to rehabilitation populations typically seen in inpatient rehabilitation.

A further strength of this study is the hybrid approach to coding and analysis that was used, which enhanced our interpretation of stroke survivors’ experiences of boredom. The initial inductive data-driven approach ensured that the themes generated were closely linked to the data. Use of a conceptual boredom framework to inform a further round of coding and analysis provided an alternative lens through which to interpret stroke survivors’ experiences. The framework increased our understanding of how a perceived lack of control may contribute to boredom and prompted us to identify and link examples of this in the data that may have otherwise been missed. Findings from this study support the concepts proposed in the boredom framework and the utility of the framework to enhance our understanding of how boredom may develop and be maintained in an inpatient rehabilitation setting.

This study provides a novel perspective for understanding how stroke survivors can meaningfully occupy their non-therapy time and the factors that contribute to boredom during their rehabilitation stay. Boredom is shaped by factors related to the person and the environment that constrain social connection and autonomy. Future research could utilise a co-design approach involving stroke survivors, their carers, architects and staff at all levels of the healthcare system. Key stakeholders working together to redesign and reorganise rehabilitation environments that support stroke survivor autonomy and acknowledge individual stroke survivor preferences, has the potential to support better engagement in rehabilitation and subsequently, improve recovery and quality of life after stroke.

Author contributions

KK, HJ, JB and NJS designed the study; KK, MT and HJ performed the data analysis, KK, HJ and MT wrote the manuscript and all authors were involved in manuscript revision.

Acknowledgements

We thank all stroke survivors who contributed their time and Dr Julie Luker and research assistant David Shakespeare who contributed to KK’s initial training and interpretation in qualitative data analysis.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Feigin VL, Brainin M, Norrving B, et al. World stroke organization (WSO): global stroke fact sheet 2022. Int J Stroke. 2022;17(1):18–29. doi: 10.1177/17474930211065917.

- Cadilhac D, Dalli L, Morrison J, et al. The Australian Stroke Clinical Registry Annual Report 2020. The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health; December 2021, Report No. 13. p. 64.

- Stroke Foundation. Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management [Accessed 2022 September 7]. Available from: https://informme.org.au/en/Guidelines/Clinical-Guidelines-for-Stroke-Management

- Lohse KR, Lang CE, Boyd LA. Is more better? Using metadata to explore dose-response relationships in stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 2014; 45(7):2053–2058. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004695.

- Schneider EJ, Lannin NA, Ada L, et al. Increasing the amount of usual rehabilitation improves activity after stroke: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2016;62(4):182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2016.08.006.

- Gittins M, Vail A, Bowen A, et al. Factors influencing the amount of therapy received during inpatient stroke care: an analysis of data from the UK Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(7):981–991. doi: 10.1177/0269215520927454.

- Eng XW, Brauer SG, Kuys SS, et al. Factors affecting the ability of the stroke survivor to drive their own recovery outside of therapy during inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Stroke Res Treat. 2014;2014:626538. doi: 10.1155/2014/626538.

- Janssen H, Ada L, Bernhardt J, et al. Physical, cognitive and social activity levels of stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation within a mixed rehabilitation unit. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(1):91–101. doi: 10.1177/0269215512466252.

- Kenah K, Bernhardt J, Spratt NJ, et al. Depression and a lack of socialization are associated with high levels of boredom during stroke rehabilitation: an exploratory study using a new conceptual framework. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2023;33(3):497–527. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2022.2030761.

- Pekrun R, Goetz T, Daniels LM, et al. Boredom in achievement settings: exploring control–value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. J Educ Psychol. 2010;102(3):531–549. doi: 10.1037/a0019243.

- Westgate EC, Wilson TD. Boring thoughts and bored minds: the MAC model of boredom and cognitive engagement. Psychol Rev. 2018;25(5):689–713. doi: 10.1037/rev0000097.

- Purcell S, Scott P, Gustafsson L, et al. Stroke survivors’ experiences of occupation in hospital-based stroke rehabilitation: a qualitative exploration. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(13):1880–1885. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1542460.

- Janssen H, Ada L, Middleton S, et al. Altering the rehabilitation environment to improve stroke survivor activity: a phase II trial. Int J Stroke. 2022;17(3):299–307. doi: 10.1177/17474930211006999.

- Janssen H, Bird ML, Luker J, et al. Stroke survivors’ perceptions of the factors that influence engagement in activity outside dedicated therapy sessions in a rehabilitation unit: a qualitative study. Clin Rehabil. 2022;36(6):822–830. doi: 10.1177/02692155221087424.

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107.

- Xu W, Zammit K. Applying thematic analysis to education: a hybrid approach to interpreting data in practitioner research. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:1–9. doi: 10.1177/1609406920918810.

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238.

- Aali G, Drummond A, das Nair R, et al. Post-stroke fatigue: a scoping review. F1000Res. 2020;9:242. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22880.2.

- Ohlmeier S, Klingler C, Schellartz I, et al. Having a break or being imprisoned: influence of subjective interpretations of quarantine and isolation on boredom. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4):2207. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042207.

- Fu V, Weatherall M, McPherson K, et al. Taking charge after stroke: a randomized controlled trial of a person-centered, self-directed rehabilitation intervention. Int J Stroke. 2020;15(9):954–964. doi: 10.1177/1747493020915144.

- Martin-Sanz MB, Salazar-de-la-Guerra RM, Cuenca-Zaldivar JN, et al. Person-centred care in individuals with stroke: a qualitative study using in-depth interviews. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):2167–2180. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2105393.

- Luker J, Lynch E, Bernhardsson S, et al. Stroke survivors’ experiences of physical rehabilitation: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(9):1698–1708 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.03.017.

- Janssen H, Bird ML, Luker J, et al. Impairments, and physical design and culture of a rehabilitation unit influence stroke survivor activity: qualitative analysis of rehabilitation staff perceptions. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(26):8436–8441. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.2019840.

- Andreoli A, Bianchi A, Campbell A, et al. In defence of falling: the onomastics and ethics of “therapeutic” falls in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2022:1–5. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2135777.

- Terry G, Kayes N. Person centered care in neurorehabilitation: a secondary analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(16):2334–2343. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1561952.

- Last N, Packham TL, Gewurtz RE, et al. Exploring patient perspectives of barriers and facilitators to participating in hospital-based stroke rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(16):4201-4210. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1881830

- Kevdzija M, Marquardt G. Stroke patients’ nonscheduled activity during inpatient rehabilitation and its relationship with the architectural layout: a multicenter shadowing study. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2022;29(1):9-15. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2020.1871281.

- van Dijk M, Vreven J, Deschodt M, et al. Can in-hospital or post discharge caregiver involvement increase functional performance of older patients? A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):362. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01769-4.

- Nelson MLA, Thombs R, Yi J. Volunteers as members of the stroke rehabilitation team: a qualitative case study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4):e032473. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032473.

- D’Souza S, Godecke E, Ciccone N, et al. Investigation of the implementation of a communication enhanced environment model on an acute/slow stream rehabilitation and a rehabilitation ward: a before-and-after pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2022;36(1):15–39. doi: 10.1177/02692155211032655.

- Saunders R, Chan K, Graham RM, et al. Nursing and allied health staff perceptions and experiences of a volunteer stroke peer support program: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:3513–3522. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S341773.

- Lipson-Smith R, Pflaumer L, Elf M, et al. Built environments for inpatient stroke rehabilitation services and care: a systematic literature review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e050247. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050247.

- Wästerfors D, Åkerström M, Jacobsson K. Reanalysis of qualitative data. In: Flick E, editor. The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. London: SAGE Publications; 2014. p. 467–480.