Abstract

Purpose

To identify and synthesise the current evidence on social participation in adults with cerebral palsy (CP).

Methods

Four databases (PubMed, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO, Web of Science) were systematically searched between December 2021 and February 2022. Pre-specified eligibility criteria were applied to all identified studies resulting in the inclusion of 16 articles. Data extraction was performed using a standardised tool and quality appraisal was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. A narrative synthesis approach was taken for data analysis.

Results

The 16 included studies were rated as high (n = 11) and medium quality (n = 5). Numbers of participants included in the studies ranged from 7 to 335. Definitions of social participation were discussed. Common themes were identified: the impact of home and work environments on social participation, the importance of age-appropriate support and interventions, and the impact of limited autonomy on social participation.

Conclusions

Adults with CP experience limited social participation due to lack of appropriate support in childhood, issues across the lifespan including physical limitations when ageing, and factors such as societal expectations and inaccessible environments which limit opportunities for autonomy. Social participation may be improved by supporting families to provide opportunities in childhood, providing timely interventions, and by enhancing autonomy.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Considering the support needs of the wider family, in order to build a supportive family environment in childhood, could improve social participation opportunities for individuals with cerebral palsy (CP) in adulthood.

Social participation in adulthood may be improved by encouraging independence and autonomy in childhood and adolescence.

Taking a lifespan approach to services for individuals with CP could improve social participation and better prepare them for the challenges of adulthood.

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a complex condition, which affects 1.5–3.4 per 1000 live births [Citation1] and encompasses a range of possible comorbidities such as movement disorders, sensory problems, speech impairment, seizures, and behavioural differences [Citation2]. While much research, support and healthcare are focused on children with CP, most individuals with CP have similar life expectancies to that of the general population [Citation3]. Although medically described as non-progressive, the experience of living with CP changes as an individual ages [Citation4]: alongside the challenges that all individuals experience during adolescence and the transition to adulthood, adults with CP face additional difficulties in fully participating in society in later life due to pain, transportation needs and regular medical appointments [Citation5,Citation6]. Previous research has examined the transition from paediatric to adult healthcare [Citation4,Citation7–10], while others have focused on access to healthcare in adulthood [Citation11] and the effects of exercise on quality of life of adults with CP [Citation12], but few have explored the interrelationship of ageing with CP and social participation.

There are clear difficulties involved in defining “social participation,” as it is a term often used interchangeably with “participation.” Since the publication of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in 2001 [Citation13], the concept of participation has been a growing theme in publications from health and social care fields [Citation14]. However, many studies fail to provide a clear definition of “participation”, and commonly blur the lines between it and social participation [Citation15], as well as social/community integration, involvement, and engagement. In a systematic review of definitions of social participation, Levasseur et al. [Citation16,p.2145] found 43 definitions across seven disciplines, the content of which varied, but were summarised as “the person’s involvement in activities that provided interactions with others in society or the community.”

The World Health Organisation [Citation13,p.10] defines participation as “involvement in a life situation.” Levasseur et al. [Citation17] note that difficulties in application of definitions that align with the ICF model could be related to the model’s attempt to integrate the opposing positions of medical and social model beliefs about disability. The medical model places health conditions of the individual as the main contributor to disability, whereas the social model considers the impact of environmental, social, and attitudinal barriers to be the predominant issue [Citation18,Citation19]. Combining the medical and social models has resulted in the individual’s environment becoming a sub-factor of participation in the ICF, rather than a key and defining component of participation.

The Institute for Social Participation [Citation20] states that the term social participation shares close links with social inclusion and social capital, whereby individuals achieve social participation through social inclusion. This position is shared by Hyyppa et al. [Citation22,p.390] who define social participation as “how actively the person participates in the activities of formal and informal groups.” Gao et al. [Citation22] highlight that many studies measure social participation by counting the number of social activities an individual attends, whereas Imms et al. [Citation23] argue that such counts effectively measure attendance, which does not necessarily constitute participation. For the purposes of this review, and due to the prevalence of the ICF model in the literature, the stance taken by Levasseur et al. [Citation17] will be followed, in that the ICF can be interpreted as constituting social participation when “participation” and “activities” are considered together as involvement and engagement with community activities.

While there have been some improvements in the social participation of disabled adults in recent years [Citation24,Citation25], there remains a stark contrast in access to opportunities for individuals with CP in comparison to the general population [Citation26,Citation27]. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UN CRPD) [Citation28] highlights the right of all disabled individuals to have access to the environment and participation in political, public, and cultural life on an equal basis with others. Currently, levels of social participation and opportunities for disabled people to enhance their social participation are still considered to be limited [Citation29], and so this systematic review sought to address the question, “what is the existing evidence base for social participation in adults with cerebral palsy?”

Methods

Information sources

Databases that included medical and healthcare publications, in addition to those with social sciences material, were used as information sources for a systematic search. These included PubMed, CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO and Web of Science. Searches were conducted between December 2021 and February 2022. Reference lists of included articles were hand-searched for additional relevant papers.

Search strategy

Similar search strategies were used for all databases, with slight editing of truncation symbols and proximity searching to allow use in different databases. A combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and key words were used to provide a comprehensive search, and these were integrated using Boolean operators (AND/OR). Key search terms “adult,” “cerebral palsy” and “social participation” were included in the search, with variations of the terms used to expand the search. Previously published reviews relating to participants with CP were examined for additional search terms. Advice was sought from an expert subject librarian before carrying out the search. All search terms used are summarised in .

Table 1. Search terms.

Eligibility criteria

Studies published between 2011 and 2021 were considered eligible for this review to reflect the most recent research findings (i.e., within the last 10 years). Inclusion criteria were: adult participants who had CP (at least 50% of the sample), studies focused on or which included measures of social participation, studies that included empirical data, and were published in the English language. Studies which provided no data on people with CP, had a majority of participants aged under 18 years old, were discussion or review articles, or did not discuss social participation were excluded from the review.

Selection process

Database searches were conducted and results exported to reference management software, EndNote version 20 [Citation30]. Following de-duplication, all remaining articles were imported to Rayyan, an online systematic review tool [Citation31]. Hand-searching of reference lists was also conducted to identify additional articles. Two reviewers independently screened the title and abstract of each record according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria and met to resolve any conflicts. A third reviewer was available for advice if conflicts could not be resolved. After title and abstract screening, two reviewers also completed full text screening for the retained articles.

Data collection process

A standardised data extraction tool was created following guidance from the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis [Citation32]. Data from the remaining 16 articles were extracted by two independent reviewers. Reviewers extracted data on author/s name and year of publication, country, aim(s), design, participants, methods/measures, findings, and definition of social participation. The final item, “definition of social participation” was not always made explicit by authors, in which case a decision was made based on the domains the research focussed on and measures used.

Quality assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool [Citation33] was used for quality appraisal of included studies. Two reviewers completed quality appraisal independently, one on all the included studies and the second reviewer on half of the included studies, selected at random. Following current guidance on the use of the MMAT [Citation33], a brief description of the assessment of quality decision was included alongside appraisal questions.

Analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of included studies a meta-analytic approach was not feasible. A narrative synthesis was employed to answer the review’s research question. Popay et al. [Citation34] describe narrative synthesis as a textual approach to summarising the findings of a systematic review, grouping together commonalities between papers to present the evidence as a narrative.

Results

The following section details the findings of the systematic search, characteristics of the included studies and quality appraisal of the studies. Findings in relation to the definitions of social participation employed and the three main themes identified in the narrative synthesis are then presented.

Systematic search results

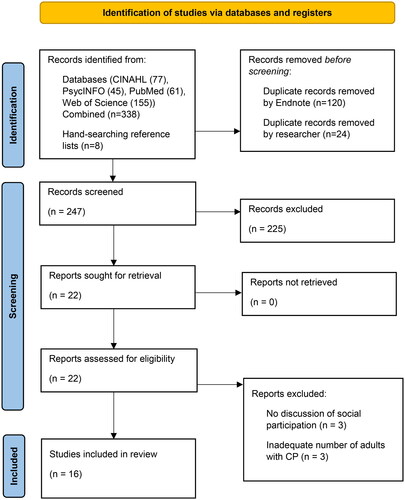

A total of 345 records were identified from the systematic search: CINAHL (n = 77), PsycINFO (n = 45), PubMed (n = 61) and Web of Science (n = 155). Following de-duplication, all remaining articles (n = 247) were screened by title and abstract: 225 records were excluded, with 22 articles retained for full text review. A further six articles were excluded following full text review as there was either no clear discussion of social participation (n = 3) or the articles had inadequate numbers of adult participants with CP (n = 3). Of the eight articles identified from hand-searching reference lists, only one was included following full text screening. The selection process is outlined in , PRISMA flowchart [Citation35].

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 16 studies included in this review are presented in . Included studies followed both qualitative (n = 5) and quantitative (n = 10) study designs, with one [Citation38] adopting a mixed methods approach. Numbers of participants in each study ranged from 7 to 335 individuals. One study [Citation36] included individuals from various diagnostic groups, but was included as 50% of participants had CP, in line with the inclusion criteria of the review. Studies were conducted in eight countries with The Netherlands being the most common place of origin (n = 5, of which n = 4 related to one longitudinal study). The remaining studies were conducted in the USA (n = 2), Canada (n = 2), Australia (n = 3), Croatia (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Latvia (n = 1) and South Africa (n = 1).

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

Quality appraisal

Quality assessment using the MMAT [Citation33] showed that 11 studies addressed all criteria [Citation24,Citation27,Citation36,Citation37,Citation41,Citation42,Citation46,Citation50,Citation52,Citation54,Citation58], whilst four studies failed to adequately address non-response bias [Citation47,Citation49,Citation55,Citation56]. The mixed methods study [Citation38] failed to provide sufficient detail to assess quality and did not address inconsistencies between qualitative and quantitative findings. Responses to MMAT questions are summarised in , with a brief explanation of quality decisions.

Table 3. Quality assessment (MMAT).

Definitions of social participation

Of the 16 included studies, only seven [Citation36–38,Citation50,Citation52,Citation54,Citation55] provided definitions of social participation. Six of these did so using the ICF model, either considering participation and activities together or reporting on social participation specifically. One study [Citation36] defined social participation through the social model. Thus, nine of the included studies [Citation24,Citation27,Citation41–43,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation56] did not define social participation but were included in the review as the measures used (quantitative studies) or questions asked (qualitative) aligned with the ICF (n = 8) [Citation24,Citation27,Citation41,Citation42,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation56] or the social model (n = 1) [Citation43].

Results from the narrative synthesis

Following narrative synthesis, three themes were identified: (1) Impact of Home & Work Life on Social Participation, (2) Considerations Across the Lifespan, and (3) Factors Limiting Autonomy.

Impact of home & work life on social participation

The first theme considered the impact of home and work environments on an individual’s social participation. The impact of the home environment was explored through the concepts of family support and parenting styles. Three of the five included qualitative papers [Citation24,Citation37,Citation41] found that family expectations both enabled and hindered social participation, as some individuals reported their parents encouraged them to be involved, while others were held back from building independence by protective parents. However, van Wely et al. [Citation55] found that the home environment in childhood (including a rejective parenting style) did not impact adult participation, whereas Van Gorp et al. [Citation54] found that environment in the teenage years negatively impacted social participation within the same cohort. Hanes et al. [Citation41] also noted the importance of family support to enable social participation for provision of transportation. Similarly, Jacobson et al. [Citation27] reported that 43% of young adults with CP were dependent on family support, both financially and for transport, with only 20% living independently by the age of 22 years.

Family support and parenting style in childhood was also found to impact individual beliefs about capacity to work. Gaskin et al. [Citation24] found that over-protective parenting in childhood may result in an apprehension towards employment due to a fear of negative employer attitudes, while supportive parenting instilled a firm belief in the individual’s employability. The benefits of employment were framed by Bartolac and Jokic [Citation36] in the context of occupational participation, which provided an avenue to meaningful participation and an improved sense of wellbeing. Jiang et al. [Citation46] reported a link between quality of life and social participation in the domain of employment, while Hanes et al. [Citation41] noted that work was a key element of meaningful social participation discussed in their qualitative interviews. Although a substantial increase in school completion in recent years by individuals with CP in Australia was found by Imms et al. [Citation42], a clear lack of improved participation outcomes in the domain of employment were evident, with employment levels of adults with CP (32.6%) being much lower than those of the general population (75.8%).

Considerations across the lifespan

Four of the five included qualitative papers [Citation24,Citation37,Citation41,Citation58] discussed the importance of considering the provision of appropriate care and support across the lifespan. Three papers [Citation37,Citation41,Citation58] framed this issue in a Life Course analysis perspective [Citation59] and considered the timeliness of interventions for individuals with CP to be crucial for ensuring optimum opportunity for social participation. One of the key findings by Gaskin et al. [Citation24] was the importance of experiences in the formative years, with many successful outcomes in adulthood being attributed to the provision of adequate support and physical interventions in childhood. Palisano et al. [Citation58] considered healthy living, that is physical, mental, and social health, to be a key component of social participation, and noted that the potential for healthy living is constantly changing as individuals with CP age. In addition, Carroll et al. [Citation37] found that social participation was hindered by the physical effects of accelerated ageing, and by the apprehension of ageing, with participants stating that they had limited knowledge on what to expect in later life with CP. Consideration of a lifespan approach was also explored through the individual experience of ageing and the difficulties involved in this process. In their longitudinal study, Van Gorp et al. [Citation54] found that difficulty in social participation increased in domains of education and employment, recreation, community life, housing, and interpersonal relationships for adults with CP in their mid to late 20s, and consequently achievement of desired levels of social participation were low. Both Van Gorp et al. [Citation52] and Van Wely et al. [Citation55] reported that individuals may benefit from early intervention in a rehabilitative setting to develop participation skills, with Van Gorp et al. [Citation52] finding that CP-related childhood factors such as intellectual disability, epilepsy, or lower levels of mobility were shown to predict up to 90% of variation in participation in adulthood.

The impact of physical interventions received during childhood on social participation in adulthood were considered in four papers [Citation24,Citation38,Citation50,Citation56]. This included discussion of medical procedures such as Selective Dorsal Rhizotomy (SDR), orthopaedic surgery and physical therapy, as well as structured exercise programmes. In their longitudinal study, Gannotti et al. [Citation38] found that the majority of participants (n = 22/26, GMFCS I–IV) who had undergone orthopaedic surgery as a child maintained or improved their gross motor function and gait abilities in adulthood and had levels of social participation similar to the general population. Similarly, Veerbeek et al. [Citation56] noted that higher levels of accomplishment and satisfaction in social participation were evident in individuals with higher levels of gross motor function and improved mobility following an early medical intervention in childhood. Notably however, in qualitative interviews, Gaskin et al. [Citation24] found that while participants recognised the positive impact of childhood physical interventions, they also felt that their social participation in childhood had been negatively impacted by the need to take time off to recover, which impacted not only their education but also their personal relationships. The importance of promoting fitness in childhood and adolescence to improve social participation outcomes in adulthood were discussed by both Slaman et al. [Citation50] and Gannotti et al. [Citation38]. Participation in a fitness training intervention by Slaman et al. [Citation50] was shown to improve quality of life and family support, and decrease fatigue and pain in adults with CP, while Gannotti et al. [Citation38] also demonstrated a relationship between increased social participation in adulthood and fitness and physical therapy in childhood/adolescence.

Factors limiting autonomy

Several papers [Citation24,Citation27,Citation36,Citation38,Citation41,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation52,Citation54,Citation58] included discussion of factors which impact an individual’s social participation by limiting their autonomy. These included physical limitations [Citation27,Citation36,Citation47,Citation52,Citation54], societal expectations [Citation24,Citation27,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation52], and environmental barriers [Citation24,Citation36,Citation38,Citation41,Citation58]. Five included papers discussed the impact of an individual’s motor skills on their social participation [Citation27,Citation36,Citation47,Citation52,Citation54]. Rozkalne et al. [Citation47] noted that physical limitations may lead to lower levels of autonomy for adults with CP in all participation domains (education and employment, finance, housing, leisure, intimate relationships, sexuality, and transportation). Further to this, Jacobson et al. [Citation27] and Bartolac and Jokic [Citation36], found that increased physical disability and lower levels of gross motor function, were linked to a lower probability of the individual with CP achieving their desired level of social participation. In a qualitative study, participants expressed that feelings of low self-confidence, the additional effort required and the fear of injuring themselves due to decreased physical ability were barriers to meaningful participation [Citation36]. In addition, Van Gorp et al. [Citation52,Citation54] showed that individuals with limited mobility experienced more difficulty in participation than those with greater motor function.

Van Gorp et al. [Citation54] suggested that increasing difficulty in achieving social participation may be explained by an increase in societal expectations as the individual enters adulthood, whereby adults are expected to be more autonomous in how they access society, leisure activities, housing, and employment. These expectations were alluded to in several studies included in this review [Citation24,Citation27,Citation46,Citation47,Citation49,Citation52]. In their quantitative study, Schmidt et al. [Citation49] considered autonomy as a key element of participation as it involves self-determination and independence. Jacobson et al. [Citation27] noted that a lack of autonomy in participation in younger years, particularly in activities of daily living, was an obstacle to successful transition to adulthood, while Rozkalne et al. [Citation47] and Schmidt et al. [Citation49] found that autonomy in participation increased with age. However, as Bartolac and Jokic [Citation36] highlighted through their social model approach to participation, environmental barriers and inaccessible physical spaces impact an individual’s experience of independence and autonomy, and a lack of choice around how they wish to participate in society. These barriers to meaningful social participation for adults with CP were highlighted in several papers [Citation24,Citation36,Citation38,Citation41,Citation58]. Gaskin et al. [Citation24], Palisano et al. [Citation58] and Gannotti et al. [Citation38] echoed these findings highlighting how addressing modifiable environmental barriers could allow individuals to reach their desired level of social participation, in addition to improving individual mental health and employment opportunities.

Discussion

This review has examined the current evidence base for social participation in adults with CP. Findings from the 16 studies included in the review demonstrate that social participation is often not a clearly defined concept. Despite this, studies included in this review were found to be of good methodological quality following quality appraisal using the MMAT [Citation33], demonstrating that while the quantity of conducted studies in this field is low, the quality of that research is high. However, the review demonstrated that although social participation is an important aspect of overall health and wellbeing of adults with CP, it is often hindered by reduced opportunities for building independence and social participation in childhood. The results showed that this is due to protective parenting styles, lack of support in finding employment, the consequences of accelerated ageing and a lack of a lifespan approach to care, and a lack of autonomy caused by physical impairments and inaccessible physical environments.

By not providing a clear definition of social participation, it is possible that studies relating to the concept may have been missed when searching the literature. While participation outcomes such as employment, education and mobility have been reported on since the 1970s [Citation60], the measures used to assess these domains have been inconsistent. Participation has also been a key theme in research and legislation relating to disabled people since the publication of the UN CRPD [Citation28], however, the value of research on participation may be lost if the frequency of attendance is measured rather than the quality of involvement. For these reasons, social participation requires a clear definition so that research focuses on “meaningful involvement”, as called for in the UN CRPD as a basic human right for disabled people. In a review on outcomes of adolescents and adults with CP, conducted by Frisch and Msall [Citation61], six commonly used measures of social participation were highlighted, only two of which emerged in the current review (Life-H [Citation51]; Short Form 36 Health Survey [Citation39]). This inconsistent use of measures and the complexity of factors examined may relate to the difficulties involved in defining social participation [Citation16,Citation17]. This lack of a clear, universal definition of social participation, combined with variability in measures used to capture the concept, has resulted in the possibility that papers of relevance may not have been identified in this systematic search.

The results from this review showed how an individual’s childhood environment, and the support they received from family and professionals affects how they experience social participation later in life [Citation6,Citation24,Citation47,Citation49,Citation54,Citation55]. In addition to studies included in this review, evidence shows that parenting styles can have either a positive or negative impact on the individual in adulthood. Wiegerink et al. [Citation62] found that a rejective parenting style resulted in poor participation in relationships in adulthood, while Reedman et al. [Citation63] found that participation in leisure activities in childhood was more successful when parents were supportive of the individual’s autonomy. This heralds a need for support to be provided for parents in early years, to highlight the impact of parenting style on social participation in later life. Also highlighted in this review was the impact that family support may have on future social participation such as fostering self-belief in the individual’s capabilities, as well as a positive attitude towards employment. It is widely known that disabled people may face barriers when seeking employment such as discrimination, lack of access to required training and education, and inaccessible workplaces [Citation64,Citation65]. While the disability employment gap remains a key concern in many countries [Citation66–68], Vornholt et al. [Citation69] suggest that disabled people are increasingly being recognised as an underutilised demographic as the current population of workers age. Employment has been found to have a positive impact on disabled individuals, including opportunities for socialisation, a sense of purpose, and a feeling of participation [Citation70,Citation71], and thus better pathways to employment opportunities are necessary to ensure individuals can participate to their desired extent.

The need for the adoption of a life course perspective to healthcare was described by several papers in the review [Citation37,Citation41,Citation58]. Interventions and support provided at the correct time, when the individual is ready (rather than when a service can provide it), could be more beneficial in the longer term. In a study on adult beliefs about the impact of surgery they received in childhood, Gannotti et al. [Citation72] found that 58% of participants believed that orthopaedic surgery had a positive impact on their functioning as adults, and related this to being happy, independent and being able to build meaningful relationships and participate in activities. However, participants who did not agree with this stated that there is a need for more information to be provided to families on the long-term outcomes and the decline in physical health that comes with ageing, once again drawing attention to the need for a lifespan approach to healthcare and provision of information. Palisano et al. [Citation58] noted that the timing of interventions, provision of assistive technologies and changes to the physical environment should correspond with the individual’s readiness to achieve desired participation outcomes, as everyone develops at a different rate. In addition to this, providing support for parents to ensure a supportive childhood home environment, as well as thinking long-term about development goals, could help the individual to prepare for change as they age. Finally, while a discussion of transition from paediatric to adult healthcare falls outside the remit of this review, many studies have highlighted the negative impact that this process may have on social outcomes and participation in adulthood if it is not planned adequately with sufficient information and support provided for both the individual and their families in childhood [Citation8,Citation73–76]. Transition must therefore be considered from early in the individual’s life for a lifespan approach to healthcare to be adopted.

This review highlighted the lack of autonomy and limited confidence many adults with CP experience due to reduced mobility and how social participation is impacted by apprehension about how physical abilities may change over time. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of autonomy and self-efficacy in the development of independence for disabled individuals, and that independence is a key factor contributing to how, and to what extent, individuals participate in society [Citation77–79]. Bartolac and Jokic [Citation36] discussed the impact of personal attributes as enablers of social participation, and how a positive attitude towards capabilities could improve the frequency and success of participation. Imms et al. [Citation42] reported that 48.7% of participants felt that a lack of confidence impacted their participation in education. Participation, and the promotion of independence to achieve social participation, should be the end goal for rehabilitation of individuals with CP, as well as key considerations for health development [Citation80,Citation81]. This independence has been alluded to through studies on autonomy [Citation47,Citation49,Citation54] as well as its interrelationship with self-efficacy [Citation50,Citation82,Citation83]. Van der Slot et al. [Citation82] suggest that by improving self-efficacy, quality of life and social participation could be improved for individuals with CP. This could in turn assist the individual in navigating expectations of adulthood and improve confidence in attending and participating in social events.

Finally, a critical factor limiting the opportunity for autonomy in social participation for adults with CP is the lack of accessible physical environments. Article 9 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN CRPD, [Citation28,p.8]) highlights the right of all persons with disabilities to “live independently and participate fully in all aspects of life,” calling for access to the physical environment, transport, and information to be provided on an equal basis with others. Despite this, accessibility remains a key issue in achieving social participation goals for people with CP. In a review on the role of the physical environment on social participation for people with limited mobility, Bigonnesse et al. [Citation73] found that the environment can be both an enabler and a barrier to social participation. Safe neighbourhoods, open public spaces such as parks, and the proximity of homes to facilities such as shops and banks enabled individuals to participate in society more easily. However, narrow pavements with poorly designed curb cuts [Citation84], lack of accessible parking spaces [Citation85] and insufficient provision of public transport [Citation86] remain significant barriers to social participation. Hanes et al. [Citation56] reported that while participants believed they had the physical ability and the desire to participate in society, they were hindered from doing so due to the inaccessibility of the environment. This was particularly true for wheelchair users who recalled issues accessing events in areas with steep inclines, as well as the unreliability and lack of elevators.

Changes to UK legislation such as the Disability Discrimination Act 1995/2005 (DDA) [Citation87] sought to reduce marginalisation and improve participation in society for all disabled people, through accessible employment, education, and transport. However, Bell and Heitmueller [Citation88] argue that due to a lack of awareness and financial support, no positive impact has been evident on employment rates of disabled people in the UK since the publication of the DDA [Citation87], and Sayce and Boardman [Citation89] highlight that disabled people are still experiencing inequality and discrimination in access to the environment. Similarly, in the USA, Carroll et al. [Citation37] found that while the enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990/2008) [Citation90] saw the provision of more accessible public transport, this was an unreliable and frustrating service, as the frequency and number of services available were insufficient to meet the needs of disabled people. Without appropriate provision of services and recognition of the accessibility of those services, social participation for disabled people, including adults with CP, cannot be achieved.

Strengths and limitations

This review provides a useful addition to the knowledge-base on adults with CP, and has highlighted a lack of clarity in definition of participation, social or otherwise, in several papers. We contend that social participation is a distinct concept, but acknowledge that term is used interchangeably with participation and thus must often be interpreted, leading to a risk of non-consensus among readers. This review also identifies sparsity in the literature regarding social participation in adults with CP and, given the small number of studies deemed eligible for inclusion and the exclusion of studies that were not published in English, conclusions should be interpreted with caution. Key strengths of this review are that two reviewers completed data extraction for included papers, thus reducing the risk of bias. An expert subject librarian was consulted when developing the search strategy to ensure the most appropriate terms were included. Reviewers also followed guidance from the Joanna Briggs Institute [Citation32] when developing a data extraction table, used the latest version of a standardised tool for quality appraisal [Citation33], and followed PRISMA guidelines when constructing the review [Citation35].

Future research

The review highlights the need for future longitudinal studies: of the ten included quantitative studies, only four were longitudinal [Citation49,Citation52,Citation54,Citation55] and all related to different elements of the same study. Longitudinal data on individuals with CP can provide an insight into factors that contribute to social participation and allows consideration of how these may change over time. With a clear definition of social participation, and the creation of an appropriate measure for the concept, more robust data could be collected on how social participation is impacted by the experience of CP. Previous reviews with this population have addressed the wider context of the lives of individuals with CP, with a focus on the physical impact of CP [Citation91] and exercise interventions [Citation12,Citation92,Citation93], as well as pain [Citation94,Citation95], and access to healthcare [Citation7,Citation11]. Future reviews should consider specific factors that hinder or promote social participation for adults with CP, in order to provide families and healthcare professionals with information on how to best support individuals across the lifespan.

Conclusions

Social participation is important for all individuals as an essential part of healthy living and wellbeing. This review sought to examine the current evidence on social participation for adults with CP and has shown that there is a lack of consensus on a definition. Clarity and consistency on a definition and measurement of the concept would facilitate a deeper understanding of social participation across the lifespan and enable fusrther research into when and how best to support social participation in people with CP. Aside from this, the barriers that still exist in society which hinder individuals from achieving their desired levels of social participation, such as physically inaccessible public spaces, are not new issues. The ongoing effort to increase awareness in public and political domains must be further substantiated with action and financial support, in order to fully implement the legislation that is already in place to improve equality for people with disabilities in access to the environment, public life, work and education. Further research should focus on the longitudinal development of social participation for individuals with CP, aiming to develop autonomy and independence from childhood, as well as developing appropriate family support, to benefit the individual in adulthood.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- McIntyre S, Goldsmith S, Webb A, et al. Global prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64(12):1494–1506. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.15346.

- Bax M, Goldstein M, Rosenbaum P, et al. Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy, April 2005. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47(8):571–576. doi: 10.1017/s001216220500112x.

- Colver A. Outcomes for people with cerebral palsy: life expectancy and quality of life. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;22(9):384–387. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2012.03.003.

- Nystrand M, Beckung E, Dickinson H, et al. Stability of motor function and associated impairments between childhood and adolescence in young people with cerebral palsy in Europe. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56(9):833–838. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12435.

- Parkinson K, Dickinson H, Arnaud C, et al. Pain in young people aged 13–17 years with cerebral palsy: cross-sectional, multicentre European study. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(6):434–440. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303482.

- Dang V, Colver A, Dickinson H, et al. Predictors of participation of adolescents with CP: a european multi-Centre longitudinal study. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;36C:551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.043.

- Solanke F, Colver A, McConachie H, Transition Collaborative Group. Are the health needs of young people with cerebral palsy met during transition from child to adult health care? Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44(3):355–363. doi: 10.1111/cch.12549.

- Freeman M, Stewart D, Cunningham E, et al. “If I had been given that information back then”: an interpretive description exploring the information needs of adults with cerebral palsy looking back on their transition to adulthood. Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44(5):689–696. doi: 10.1111/cch.12579.

- Roquet M, Garlantezec R, Remy-Neris O, et al. From childhood to adulthood: health care use in individuals with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(12):1271–1277. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14003.

- Myers L, Nerminathan A, Fitzgerald D, et al. Transition to adult care for young people with cerebral palsy. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2020;33:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2019.12.002.

- Manikandan M, Walsh A, Kerr C, et al. Health service use among adults with cerebral palsy: a mixed-methods systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;10(8):e035892. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035892.

- Czencz J, Shields N, Wallen M, et al. Does exercise affect quality of life and participation of adolescents and adults with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;:1–17. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2148297.

- International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health. World Health Organization; 2001 [online] [cited 2021 Oct 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health.

- Piskur B, Daniels R, Jongmans MJ, et al. Participation and social participation: are they distinct concepts? Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(3):211–220. doi: 10.1177/0269215513499029.

- Dalemans R, de Witte LP, Lemmens J, et al. Measures for rating social participation in people with aphasia: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(6):542–555. doi: 10.1177/0269215507087462.

- Levasseur M, Richard L, Gauvin L, et al. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2141–2149. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.041.

- Levasseur M, Desrosiers J, Tribble DS. Comparing the disability creation process and international classification of functioning, disability and health models. Can J Occup Ther. 2007;74:233–242. doi: 10.1177/000841740707405S02.

- Oliver M. Social work with disabled people. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 1983.

- Oliver M. The politics of disablement. London: Macmillan; 1990.

- Bathgate T, Romios P. Consumer participation in health: understanding consumers as social participants. La Trobe University, Institute for Social Participation and Health Issues Center; 2011. Available from: https://hic.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/HIC-Understanding-consumers-as-social-participants.pdf

- Hyyppa MT, Maki J, Alanen E, et al. Long-term stability of social participation. Soc Indic Res. 2008;88(2):389–396. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9199-y.

- Gao M, Sa Z, Li Y, et al. Does social participation reduce the risk of functional disability among older adults in China? A survival analysis using the 2005–2011 waves of the CLHLS data. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):224. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0903-3.

- Imms C, Granlund M, Wilson PH, et al. Participation, both a means and an end: a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(1):16–25. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13237.

- Gaskin C, Imms C, Dagley G, et al. Successfully negotiating life challenges: learnings from adults with cerebral palsy. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(12):2176–2193. doi: 10.1177/10497323211023449.

- Pagliano E, Casalino T, Mazzanti S, et al. Being adults with cerebral palsy: results of a multicenter italian study on quality of life and participation. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(11):4543–4550. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05063-y.

- Michelsen S, Flachs E, Damsgaard M, et al. European study of frequency of participation of adolescents with and without cerebral palsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18(3):282–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.12.003.

- Jacobson DNO, Lowing K, Hjalmarsson E, et al. Exploring social participation in young adults with cerebral palsy. J Rehabil Med. 2019;51(3):167–174. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2517.

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. United Nations General Assembly; 13 December 2006, A/RES/61/106, Annex I [cited 2021 Oct 27]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CRPD/Pages/ConventionRightsPersonsWithDisabilities.aspx.

- Bricout J, Baker PMA, Moon NW, et al. Exploring the smart future of participation: community, inclusivity, and people with disabilities. Int J E-Plan Res. 2021;10(2):94–108. doi: 10.4018/IJEPR.20210401.oa8.

- The EndNote Team. EndNote [64 bit]. EndNote 20. Philadelphia (PA): Clarivate; 2013.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan – a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

- Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Canada: Canadian Intellectual Property Office; 2018.

- Harris F, Yang H, Sanford JM. Physical environmental barriers to community mobility in older and younger wheelchair users. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2015;31(1):42–51. doi: 10.1097/TGR.0000000000000043.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Brit Med J. 2021;372(71):1–9.

- Bartolac A, Jokic CS. Understanding the everyday experience of persons with physical disabilities: building a model of social and occupational participation. J Occup Sci. 2019;26(3):408–425. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2018.1522597.

- Carroll A, Chan D, Thorpe D, et al. A life course perspective on growing older with cerebral palsy. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(4):654–664. doi: 10.1177/1049732320971247.

- Gannotti ME, Gorton GE, Nahorniak MT, et al. Gait and participation outcomes in adults with cerebral palsy: a series of case studies using mixed methods. Disabil Health J. 2013;6(3):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.01.013.

- Jahnsen R, Villien L, Egeland T, et al. Locomotion skills in adults with cerebral palsy. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18(3):309–316. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr735oa.

- Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, et al. Canadian occupational performance measure. 4th ed. Canada: Canadian Occupational Therapy Association; 2005.

- Hanes JE, Hlyva O, Rosenbaum P, et al. Beyond stereotypes of cerebral palsy: exploring the lived experiences of young Canadians. Child Care Health Dev. 2019;45(5):613–622. doi: 10.1111/cch.12705.

- Imms C, Reddihough D, Shepherd DA, et al. Social outcomes of school leavers with cerebral palsy living in Victoria. Front Neurol. 2021;12:753921. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.753921.

- Palisano RJ, Cameron D, Rosenbaum PL, et al. Stability of the gross motor function classification system. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(6):424–428. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206000934.

- Eliasson AC, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Rosblad B, et al. The manual ability classification system (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(7):549–554. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206001162.

- Hidecker MJ, Paneth N, Rosenbaum PL, et al. Developing and validating the communication function classification system for individuals with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(8):704–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03996.x.

- Jiang B, Walstab J, Reid SM, et al. Quality of life in young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(4):673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.04.006.

- Rožkalne Z, Mukāns M, Vētra A. Transition-Age young adults with cerebral palsy: level of participation and the influencing factors. Medicina. 2019;55(11):737. doi: 10.3390/medicina55110737.

- Donkervoort M, Wiegerink DJHG, van Meeteren J, et al. Transition to adulthood: validation of the Rotterdam transition profile for young adults with cerebral palsy and normal intelligence. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(1):53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03115.x.

- Schmidt AK, van Gorp M, van Wely L, Perrin-Decade Pip Study Groups, et al. Autonomy in participation in cerebral palsy from childhood to adulthood. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62(3):363–371. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14366.

- Slaman J, Van Den Berg-Emons HJG, Van Meeteren J, et al. A lifestyle intervention improves fatigue, mental health and social support among adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy: focus on mediating effects. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29(7):717–727. doi: 10.1177/0269215514555136.

- Fougeyrollas PNL, St-Michel G. Life habits measure – shortened version (LIFE-H 3.0). Canada: Lac St-Charles; 2001.

- Van Gorp M, Roebroeck ME, Van Eck M, et al. Childhood factors predict participation of young adults with cerebral palsy in domestic life and interpersonal relationships: a prospective cohort study. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(22):3162–3171. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1585971.

- Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV. Vineland-II: Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: survey forms manual. Minneapolis: NCS Pearson Inc; 2005.

- Van Gorp M, Van Wely L, Dallmeijer AJ, et al. Long-term course of difficulty in participation of individuals with cerebral palsy aged 16 to 34 years: a prospective cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(2):194–203. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14004.

- Van Wely L, Van Gorp M, Tan SS, et al. Teenage predictors of participation of adults with cerebral palsy in domestic life and interpersonal relationships: a 13-year follow-up study. Res Dev Disabil. 2020;96:103510. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103510.

- Veerbeek BE, Lamberts RP, Fieggen AG, et al. Daily activities, participation, satisfaction, and functional mobility of adults with cerebral palsy more than 25 years after selective dorsal rhizotomy: a long-term follow-up during adulthood. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(15):2191–2199. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1695001.

- Graham HK, Harvey A, Rodda J, et al. The functional mobility scale (FMS). J Pediatric Orthop. 2004;24(5):514–520. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200409000-00011.

- Palisano RJ, Di Rezze B, Stewart D, et al. Promoting capacities for future adult roles and healthy living using a lifecourse health development approach. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(14):2002–2011. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1544670.

- Elder GH, Johnson MK, Corsnoe R. The emergence and development of life course theory. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the life course. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. USA: Springer; 2003.

- Kembhavi G, Darrah J, Payne K, et al. Adults with a diagnosis of cerebral palsy: a mapping review of long-term outcomes. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(7):610–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03914.x.

- Frisch D, Msall ME. Health, functioning, and participation of adolescents and adults with cerebral palsy: a review of outcomes research. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2013;18(1):84–94. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.1131.

- Wiegerink DJHG, Stam HJ, Ketelaar M, et al. Personal and environmental factors contributing to participation in romantic relationships and sexual activity of young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(17):1481–1487. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.648002.

- Reedman SE, Boyd RN, Ziviani J, et al. Participation predictors for leisure‐time physical activity intervention in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021;63(5):566–575. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14796.

- Awsumb J, Schutzt M, Carter E, et al. Pursuing paid employment for youth with severe disabilities: multiple perspectives on pressing challenges. Res Pract Persons Severe Disabil. 2022;47(1):22–39.

- Friedman C. The relationship between disability prejudice and disability employment rates. Work. 2020;65(3):591–598. 2020doi: 10.3233/WOR-203113.

- Kuromiya K. Econometric analysis of the employment of persons with disabilities in prefectural boards of education. Int J Econ Policy Studies. 2022;16:423–441.

- Konur O. Access to employment by disabled people in the UK: is the disability discrimination act working? Int J Discrim Law. 2002;5(4):247–279. doi: 10.1177/135822910200500405.

- Mizunoya S, Mitra S. Is there a disability gap in employment rates in developing countries? J World Dev. 2013;42:28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.05.037.

- Vornholt K, Villotti P, Muschalla B, et al. Disability and employment – overview and highlights. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2018;27(1):40–55. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2017.1387536.

- McCausland D, Guerin S, Tyrrell J, et al. A qualitative study of the needs of older adults with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34(6):1560–1568. doi: 10.1111/jar.12900.

- Johnson KL, Yorkston KM, Klasner ER, et al. The cost and benefits of employment: a qualitative study of experiences of persons with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(2):201–209. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00614-2.

- Gannotti ME, Wilson JL, Bagley AM, et al. Adults with cerebral palsy rank factors associated with quality of life and perceived impact of childhood surgery on adult outcomes. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(17):2431–2438. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1701718.

- Bigonnesse C, Mahmood A, Chaudhury H, et al. The role of neighborhood physical environment on mobility and social participation among people using mobility assistive technology. Disabil Soc. 2018;33(6):866–893. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2018.1453783.

- Björquist E, Nordmark E, Hallström I. Living in transition – experiences of health and well-being and the needs of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(2):258–265. doi: 10.1111/cch.12151.

- Carroll EM. Health care transition experiences of young adults with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(5):e157-164–e164. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.018.

- Ryan JM, Walsh M, Owens M, et al. Transition to adult services experienced by young people with cerebral palsy: a cross-sectional study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2023;65(2):285–293. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.15317.

- Cardol M, De Jong BA, Ward CD. On autonomy and participation in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(18):970–974. 2002doi: 10.1080/09638280210151996.

- Cijsouw A, Adriaansen JJE, Tepper M, et al. Associations between disability-management self-efficacy, participation and life satisfaction in people with long-standing spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2017;55(1):47–51. 2017doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.80.

- Te Velde SJ, Lankhorst K, Zwinkels M, et al. Associations of sport participation with self-perception, exercise self-efficacy and quality of life among children and adolescents with a physical disability or chronic disease – a cross-sectional study. Sports Med Open. 2018;4(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s40798-018-0152-1.

- Michelsen SI, Uldall P, Hansen T, et al. Social integration of adults with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(8):643–649. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206001368.

- Colver A. Quality of life and participation. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(8):656–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03321.x.

- Van der Slot WM, Nieuwenhuijsen C, van den Berg-Emons RJ, et al. Participation and health-related quality of life in adults with spastic bilateral cerebral palsy and the role of self-efficacy. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(6):528–535. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0555.

- Belil FE, Alhani F, Ebadi A, et al. Self-efficacy of people with chronic conditions: a qualitative directed content analysis. J Clin Med. 2018;7(11):411. doi: 10.3390/jcm7110411.

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme; 2006. Available from: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf

- Bromley RDF, Matthew DL, Thomas CJ. City Centre accessibility for wheelchair users: the consumer perspective and the planning implications. Cities. 2007;24(3):229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2007.01.009.

- Gibson BE, Secker B, Rolfe D, et al. Disability and dignity-enabling home environments. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.006.

- Disability Discrimination Act. Disability discrimination act. 1995 [online] [cited 2022 May 24]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1995/50/contents.

- Bell D, Heitmueller A. The disability discrimination act in the UK: Helping or hindering employment among the disabled? J Health Econ. 2009;28(2):465–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.10.006.

- Sayce L, Boardman J. Disability rights and mental health in the UK: recent developments of the disability discrimination act. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2008;14(4):265–275. doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.106.003103.

- Van Der Slot WMA, Benner JL, Brunton L, et al. Pain in adults with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2021;64(3):101359. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2019.12.011.

- Hombergen SP, Huisstede BM, Streur MF, et al. Impact of cerebral palsy on health-related physical fitness in adults: systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(5):871–881. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.11.032.

- Ross SM, Macdonald M, Bigouette JP. Effects of strength training on mobility in adults with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(3):375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.04.005.

- Ryan JM, Cassidy EE, Noorduyn SG, et al. Exercise interventions for cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD011660. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011660.pub2.

- Americans with Disabilities Act. As amended with ADA Amendments Act of 2008 [online]; 1990 [cited 2022 May 25]. Available from: http://www.ada.gov/pubs/adastatute08.htm#12102.

- Mckinnon CT, Meehan EM, Harvey AR, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of pain in children and young adults with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(3):305–314. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14111.