Abstract

Purpose

Specialised vocational rehabilitation (VR) following acquired brain injury (ABI) positively impacts return to work, however access to this is limited globally. Providing VR as a component of standard ABI rehabilitation may improve access to VR and influence vocational outcomes. This study aimed to develop an evidence-based framework for the delivery of ABI VR during early transitional community rehabilitation.

Materials and Methods

The development of the ABI VR framework utilised an emergent multi-phase design and was informed by models of evidence-based practice, national rehabilitation standards, guidelines for complex intervention development, model of care and framework development, and the knowledge-to-action framework. Four study phases were undertaken to identify and generate the evidence base, with findings synthesised to develop the ABI VR framework in phase five.

Results

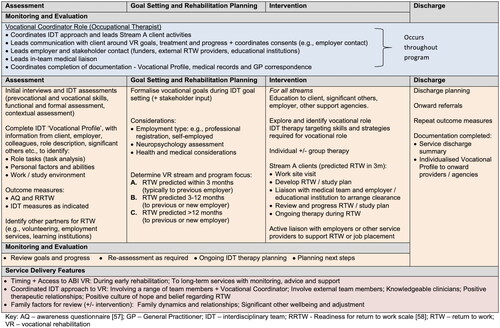

The framework provides a structure for the systematic delivery of VR as a component of team-based ABI rehabilitation, through five phases of rehabilitation: assessment; goal setting and rehabilitation planning; intervention; monitoring and evaluation; and discharge. It details the activities to be undertaken across the phases using a hybrid model of ABI VR (involving program-based VR and case coordination) and contains service delivery features.

Conclusion

The framework has the potential to translate to other similar service contexts.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

An evidence-based framework has been developed to support the provision of vocational rehabilitation as a component of team-based rehabilitation for adults with acquired brain injury, within the context of early, community rehabilitation.

Providing vocational rehabilitation as a component of team-based rehabilitation should improve access to vocational rehabilitation and may positively influence client return to work outcomes.

The vocational framework may assist clinicians to identify components of vocational rehabilitation that they can deliver in practice in their own service context.

Introduction

Within Australia, acquired brain injury (ABI) (including traumatic brain injury (TBI)), is the leading cause of disability in working-aged adults [Citation1]. An estimated one in 45 Australians live with a disability resulting from ABI that limits their activity or participation [Citation1], including returning to paid employment. It is estimated that only 40% of working-aged adults with ABI return to work (RTW) post-injury [Citation2], with difficulty experienced across all injury severities [Citation3] and impacting the quality of life [Citation4].

Returning to work following ABI is challenging. ABI can impact a range of skills that are required for the workplace, including cognition and executive skills, insight and awareness, communication and social skills, physical skills, fatigue, mood and personality [Citation5–11]. Other factors that influence RTW for adults with ABI include workplace factors such as supportive employers, knowledge of ABI, the ability to modify tasks and the nature of work to be undertaken [Citation6,Citation7,Citation9,Citation12]; environmental factors including family, partner and social supports [Citation7,Citation9]; and individual factors including a person’s level of education, employment status, pre-injury job performance, drive and motivation for work, participation in meaningful activities and interests, as well as previous illnesses including a psychiatric history or substance abuse [Citation5,Citation7–9,Citation12].

Adults with ABI benefit from access to specialised vocational rehabilitation (VR) to support RTW [Citation5–7,Citation13]. VR aims to support and enable people with disability to overcome barriers to employment [Citation14] and involves targeting skills through specific rehabilitation programs [Citation15]. ABI VR can be provided across all timepoints, from early post-injury (e.g., during inpatient rehabilitation) [Citation16] to those experiencing long-term unemployment [Citation17], through a variety of services and models. A recent scoping review identified 16 different models of ABI VR [Citation18]. Models included case coordination, program-based rehabilitation, supported employment [Citation19], consumer-directed models [Citation20], stakeholder models [Citation21,Citation22], models related to specific components of VR (e.g., work readiness evaluation) [Citation23] and mixed or hybrid models. While the identified models of ABI VR differed in regard to their membership, timing, access and service delivery features, they shared common themes, including utilising person-centred approaches; involving stakeholders; and recognising the importance of environment and the complex interaction of factors for ABI VR [Citation18]. Conversely, the processes that underpinned VR were more consistent across the studies [Citation18]. Identified processes of ABI VR included: intake; information gathering, assessment and analysis/synthesis; goal setting; engaging stakeholders; providing interventions pre- and post- work placement; reviewing outcomes; and discharge [Citation18].

Successful RTW for adults with ABI is associated with a range of VR interventions, including preparing clients for the workplace by providing pre-vocational training, work-directed interventions and targeting specific skills in rehabilitation [Citation7,Citation9,Citation24], and providing job coaching, education and guidance for returning to work [Citation9,Citation25,Citation26]. Typically, a combination of intervention components is provided during VR [Citation9]. While the evidence base for ABI VR continues to grow, there is currently no gold standard model or service [Citation18,Citation19,Citation27], and variations in service provision (including timing and population features) add to the complexity of translating evidence into practice.

Improving rates of RTW for adults with ABI is complex. It requires services and clinicians to have specialist knowledge of brain injury and VR [Citation28] as well as improving client access to specialised services. Access to ABI VR is influenced by the policies, services and systems of rehabilitation provision [Citation5,Citation8], however, access to ABI VR is not universal, with unmet needs identified in countries with established health care and rehabilitation services [Citation7]. Within Australia, access to services, funding and skilled clinicians for dedicated ABI VR is limited [Citation24,Citation29]. This includes reduced access to ABI VR for clients without insurance-based funding [Citation24] and a lack of experienced ABI VR providers [Citation7]. Australian clinicians have identified the need for increased education and support for providing brain injury rehabilitation [Citation30] and training and support to provide ABI VR [Citation31].

Within the state of Queensland, Australia, access to and provision of ABI VR is varied. State-wide planning acknowledges the need to improve vocational services and facilitate vocational outcomes for clients with ABI, including during transitional and community rehabilitation [Citation32]. Service consumers (adults with ABI) may access VR through insurance-funded therapy services or access components of VR through a publicly funded rehabilitation program [Citation31,Citation33]. Both service consumers and service providers have identified a range of challenges with ABI VR, including staff knowledge and training; access to services including longer-term services; and service delivery, including communication with employers and across services, and provision of key VR components (e.g., conducting workplace visits) [Citation29,Citation31,Citation33]. While clinicians provide rehabilitation according to international best-practice models [Citation34,Citation35] and national rehabilitation guidelines [Citation36,Citation37], no specific model or framework of ABI VR is currently used in Queensland [Citation31]. Internationally, similar challenges are reported for ABI VR, including access and availability of services, provision of VR components and use of specific protocols/frameworks in practice [Citation7,Citation9,Citation38]. In the absence of dedicated, accessible ABI VR services, improving access to ABI VR may require a different solution. Providing VR as a component of ABI rehabilitation has been recommended as a service delivery option [Citation31,Citation39], however, guidelines, models or frameworks to support this are limited.

The need for a framework to guide the provision of ABI VR in Queensland within and across services has been identified by clinicians [Citation31]. Frameworks aim to positively change practice within an organisation and should align with the intent of users, accurately detail components, be easily understood and implemented, and be developed with input from stakeholders including consensus on good practice [Citation40]. A framework for ABI VR would assist rehabilitation services and clinicians to provide VR in a consistent manner, by detailing the processes and components of ABI VR to be undertaken, activities and responsibilities of rehabilitation team members, timing of activities, and ideally assist in transitions between services. This would directly influence practice within and across services and improve client experiences and outcomes. Further, the framework should align with the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [Citation34] which underpins the delivery of health and rehabilitation services worldwide, including national rehabilitation guidelines [Citation36].

The aim of this study was to develop a contextual, evidence-based framework for the delivery of interdisciplinary VR for adults with moderate-severe ABI during early transitional community rehabilitation. The VR framework was designed for a specific service context – a publicly funded transitional ABI rehabilitation service, which provides 12 weeks of interdisciplinary rehabilitation for adults with moderate-severe ABI transitioning from hospital to home, as a component of a state-wide ABI service [Citation32,Citation41], where services are provided within the ICF framework [Citation34]. In this context, ABI severity is determined prior to admission, through a range of factors and measures including immediate clinical presentation (e.g., level of consciousness as measured by the Glasgow Coma Scale [Citation42]), diagnostic findings (e.g., brain imaging and grading of severity) and specific patient symptomatology (e.g., length of post-traumatic amnesia following TBI) [Citation43–45]. Detailed information regarding the model of care of this service including admission and exclusion criteria is publicly available [Citation41], as is clinical program outcome data [Citation46,Citation47]. Within the service context around 60% of clients identify vocational goals (i.e., related to RTW, volunteering or study). Developing clinical services to address the ABI VR needs of clients was a component of the service’s pilot funding agreement and an identified state-wide system-level need [Citation32]. Additionally, service clinicians identified the need to improve VR service delivery, including providing consistent, evidence-based ABI VR to clients with vocational goals, across all levels of readiness for RTW.

Materials and methods

This study has ethical approval from Metro South Health and Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committees (HREC/18/QPAH/497; GU Ref:2018/998). An emergent multi-phase design [Citation48] guided the development of the evidence-based framework for ABI VR in early rehabilitation. Five separate phases of research activity were undertaken, with findings from phases 1–4 (identifying the contextual evidence base for ABI VR) informing the final study phase (phase five, ABI VR framework development). As each study phase had an individual methodology, a range of processes, models and frameworks have informed this research. This is detailed below.

Study phases 1-4: Identifying the evidence base

In phases 1-4, a series of studies were undertaken to identify and generate the contextual evidence base for ABI VR, guided by Hoffman’s model of evidence-based practice (EBP-4) [Citation35]. This involved identifying the formal research evidence base plus investigating the evidence base related to consumer and expert clinician views and experiences with ABI VR within the context of Queensland services.

In phase one, the international research evidence base for ABI VR was investigated via a systematic scoping review, to identify models, processes and components of ABI VR [Citation18]. Phase two investigated consumer (community-living adults with ABI) experiences with ABI VR and RTW, within the context of Queensland-based services [Citation33]. Phase three identified the views and experiences of ABI and VR clinicians regarding their provision of ABI VR services in Queensland, to provide expert opinion [Citation31]. Phase four investigated the views and experiences of families/significant others of phase two participants regarding ABI VR and RTW in Queensland, to provide additional consumer evidence. Outcomes of the first three phases have previously been published [Citation18,Citation31,Citation33]; findings from phase four are reported in this paper (see Results and Appendix 2). A summary of the research phases that identified the clinical evidence base that informed the ABI VR framework are presented in . The specific findings from these studies that influenced framework development are reported in the Results and in Appendix 1.

Table 1. Phases of research activity underpinning the ABI VR framework.

Study phase 5 – developing the ABI VR framework

Phase five involved the development of the ABI VR framework. This was informed by a range of models, processes and frameworks, including the Knowledge to Action (KTA) framework [Citation49], the Medical Research Council’s (MRC) guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions [Citation50,Citation51], the Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare: revised guidelines (CReDICI 2 guidelines) [Citation52], plus principles of model of care and framework development [Citation53]. The ABI VR framework’s content and structure were informed by the evidence-based findings from phases 1-4, national practice standards for ambulatory rehabilitation [Citation36] and the context and model of care of the service for implementation [Citation41]. This process is detailed below.

Initial processes from the KTA framework, knowledge creation and the first two steps of the action cycle, were applied [Citation49]. This involved: identifying the problem; creating knowledge through research and inquiry; synthesising findings; identifying, reviewing and selecting knowledge (for use in the ABI VR framework); adapting the knowledge to the local context; and developing tools. The validity of applying parts of the KTA framework is supported by its authors [Citation49].

Guiding principles for a model of care and framework development [Citation53] were also adhered to when developing the ABI VR Framework. This included: using the best available evidence (e.g., as identified across phases 1–4); wide collaboration to develop the framework (involving clients, carers, clinicians, health care partners, managers and other organisations across phases 2–4); extending and enhancing service provision (i.e., ABI VR) within and across services; and linking to strategic initiatives and service targets/performance indicators (i.e., at a service and state-wide level [Citation32]).

The first step of the MRC’s guidelines for developing and evaluating complex interventions [Citation50,Citation51] was undertaken. This involved identifying existing evidence and theory, plus modelling the processes of ABI VR (e.g., clinical activities and intervention components). Additionally, the CReDICI 2 guidelines [Citation52] for the development of complex healthcare interventions were applied to this study, with all four steps of Stage 1 (i.e., development) conducted.

The ABI VR framework’s content and structure were designed to align with Australian national practice standards for ambulatory and community rehabilitation [Citation36] and address core components of community rehabilitation. Specifically, this included assessment, rehabilitation planning, goal setting, providing interventions, reviewing and reassessing, service liaison, supporting RTW and completing documentation. Additionally, the context of the implementing service and its model of care (including workflow, service delivery structure, provision of family-centred rehabilitation and the use of team-based interdisciplinary practice) [Citation41] influenced framework development. This is detailed further within the Results.

The international research and contextual clinical evidence base regarding ABI VR, as identified through study phases 1-4 and application of the EBP-4 model [Citation35] also informed the content and structure of the ABI VR framework. These findings (e.g., ABI VR clinical activities, processes, timing, service delivery features) were aligned and synthesized with the core national rehabilitation components [Citation36] and the service model of care [Citation41] to create the ABI VR framework. The specific findings from phases 1–4 that influenced framework development are reported in the Results and in Appendix 1. Aligning with KTA processes [Citation49], the development of local tools and processes to support the local implementation of the ABI VR Framework also occurred; this is detailed further in the Results and Discussion.

Results

The key findings from the four study phases that informed the framework are presented below, additional detail is provided in Appendix 1. Synthesis of the findings and framework development are reported in detail in phase five.

Phase one findings: scoping review

The systematic scoping review [Citation18] investigated how VR is provided to adults with ABI, and identified models of ABI VR, clinical processes and components of ABI VR; 57 articles met the criteria for review. Key findings [Citation18] were used to develop the ABI VR framework as follows:

All nine identified clinical processes of ABI VR identified in the scoping review were included in the ABI VR framework - intake/purpose, information gathering, assessment/evaluation, analysis and synthesis, stakeholder engagement, goal setting, intervention, evaluation/review and discharge from service [Citation18].

Seven of the eight process components identified in the scoping review were included - assessment of the person, the environment/work factors, job demands; contextual assessment and intervention; development of return-to-work plan and recommendations; pre-placement intervention; and education [Citation18]. While the framework highlights ongoing intervention during RTW, the component of post-placement intervention was not included, given the time-limited nature of the implementing service.

All four service delivery components identified in the scoping review were included - active stakeholder engagement (including engaging with workplaces and employers), using a coordinated interdisciplinary approach to deliver ABI VR, timing of ABI VR (i.e., commencing from post-hospital discharge) and access to ABI VR as part of regular service delivery.

Of the 16 models of ABI VR identified in the scoping review [Citation18] a hybrid model of ABI VR was selected for the ABI VR framework, aligning with the service model of care [Citation41], supporting the delivery of VR as a component of an ABI rehabilitation program, and supporting delivery of key identified activities for ABI VR. Specifically, the hybrid model involves aspects of case coordination (i.e., having a designated VR coordinator role to coordinate the VR plan within the team and with external stakeholders) and program-based VR (including providing the majority of rehabilitation and training prior to RTW) [Citation18].

The key processes, components, service delivery components and model factors detailed above have been included in the ABI VR framework (see phase five findings), with further detail included in Appendix 1.

Phase two findings: consumer experiences of ABI VR in Queensland

Consumer experiences with ABI VR in Queensland were examined through a qualitative study [Citation33]; 8 adults with ABI discussed their experiences and views through focus groups or interviews, and data were analysed thematically [Citation54]. From this, five experiential themes and five areas for future service development were identified [Citation33]. The key consumer experiences and views regarding ABI VR that have been integrated into the framework are detailed below.

Access to ABI VR following hospital discharge, including receiving interventions that: are individualised; link therapy activities with work goals, particularly for clients with longer RTW timeframes; and include education and information regarding rehabilitation, VR and RTW.

Addressing the impact of injury on partners/families as a specific component of VR.

Having a designated clinician undertake employer communication and liaise with other services and supports, through implementing a VR coordinator role.

Receiving interventions that address changes to identity, maintaining relationships, social relationships in the workplace, and establishing social and peer supports. This is addressed in the framework through the involvement of the interdisciplinary team to address RTW goals, including social work, psychology, speech pathology and group-based interventions, within a client- and family-centric model of care [Citation41].

Clinician-specific service delivery factors, including fostering positive therapeutic relationships and clinicians acknowledging the importance of RTW goals from early in recovery. These are addressed in the framework by: including the therapeutic relationship in the ‘service delivery features’ of the ABI VR framework; ensuring vocational goals are addressed through goal setting and rehabilitation planning, identifying level of readiness for RTW and linking rehabilitation activities to work goals; and through discharge planning, onward referrals and handover to later services to continue to address RTW goals and ongoing ABI VR following discharge from the service.

The areas identified above from phase two have been incorporated into the ABI VR framework (see phase five), with further detail provided within Appendix 1.

Phase three findings: health professional experiences and views of ABI VR

This phase investigated the experiences and views of ABI and VR clinicians (n = 34) regarding the provision of ABI VR in Queensland, through focus groups and online surveys to provide information on contextual clinical practice, expert opinion and clinicians’ views of ideal practice [Citation31]; data were analysed through content analysis [Citation55,Citation56]. This qualitative study identified current service delivery and clinical practice for ABI VR (including assessment and interventions, determining readiness for RTW), and views on service gaps and future best-practice services [Citation31]. The key findings that informed the ABI VR framework development are summarised below and include:

Having a coordinated interdisciplinary approach for ABI VR, and utilising a VR coordinator role to coordinate the team and processes;

Undertaking specific assessment processes, including identifying pre-vocational and vocational skills, gathering information from a range of sources including family, conducting task analysis, and using formal and informal assessments across the rehabilitation team;

Using collaborative team-based goal setting and rehabilitation planning, including determining readiness for RTW and type of VR activities required (e.g., targeting pre-vocational skills, targeting workplace skills);

Providing a range of ABI VR interventions, including education; communicating goals and their VR focus to clients; providing VR from early in recovery – including addressing pre-vocational skills, actively addressing workplace skills and roles, and addressing other vocational roles; involving family; undertaking specific workplace tasks including employer liaison, conducting worksite assessments, creating a graded and realistic RTW plan; supporting clients during and post-RTW;

Monitoring to identify changes in VR needs over time;

Undertaking discharge planning (including making early referrals, improving service transitions and providing VR handover as standard practice).

The above features have been included in the ABI VR framework (see phase five); also see Appendix 1 for additional details.

Phase four findings: views of significant others regarding ABI VR in Queensland

This phase examined the experiences and views of significant others (S/Os) regarding their family member’s ABI VR experience in Queensland, through an online survey. The S/Os (n = 2) were the partners of phase two participants (adults with ABI, n = 8). The study identified S/O’s views of their partner’s RTW goals and VR experiences, S/O satisfaction with rehabilitation, the impact of the ABI on the S/O and recommendations for future services. Data were analysed thematically [Citation54,Citation56] with three experiential themes identified. The key findings that informed the development of the ABI VR framework are summarised below and include:

Promoting clinician-specific service delivery features of a positive therapeutic relationship, including positivity and hope for RTW and acknowledging the importance of work from early in recovery;

Access to VR from early in recovery and during community rehabilitation;

Provision of ABI VR interventions that involve cognitive rehabilitation and higher level skills, active workplace liaison and a coordinated approach for RTW;

Access to longer-term supports for ABI VR (e.g., through onward referrals and discharge planning);

Ensuring ABI VR considers the impact on family and S/O and provides support in key areas (e.g., adjustment, relationships).

The above features have been included within the ABI VR framework (see phase five below), and further detailed in Appendix 1. The study is reported in detail in Appendix 2, with survey questions provided in Appendix 3.

Phase five findings: development of a framework for early ABI VR

In phase five, the evidence-based framework for ABI VR was developed by the research team. Information on the service context and model of care for implementation [Citation41], national rehabilitation practice standards [Citation36] and the key findings from phases one to four above were synthesized to create the framework. This is reported in detail in the following section; an overview of the framework is presented as follows. The framework comprises five phases of rehabilitation (assessment, goal setting and rehabilitation planning, intervention, monitoring and evaluation, discharge) and details the ABI VR activity components provided within these phases. These activities are performed by either a VR coordinator (top section of the framework) or by the interdisciplinary team (middle section of framework). The bottom component of the framework contains the team-based service delivery features for ABI VR. The interdisciplinary ABI VR framework is presented in ; additional information on research phases and their contribution to the framework are presented in Appendix 1; further detail on the framework development is presented below.

Figure 1. Framework for interdisciplinary vocational rehabilitation in transitional ABI rehabilitation.

The framework was developed for implementation within a specific clinical context and model of care [Citation41]. Specifically, a 12-week interdisciplinary transitional community ABI rehabilitation program which utilises set clinical workflow and service delivery structures to deliver a range of rehabilitation activities (e.g., assessment based on the ICF [Citation34], interdisciplinary goal setting and rehabilitation planning, therapeutic interventions, rehabilitation medicine review, discharge planning) [Citation41]. Within this context, VR is provided as a component of a client’s interdisciplinary rehabilitation program and involves the rehabilitation team (comprised of occupational therapy, speech pathology, social work, physiotherapy and/or exercise physiology and rehabilitation medicine; plus clinical psychology, neuropsychology and therapy assistants as required), external stakeholders (e.g., employer, funders and support coordinators, employment support services), the client, their family and community networks. These factors informed both the structure and content of the framework.

The structure of the framework was developed to align with national rehabilitation practice standards [Citation36] and includes multiple components of community rehabilitation, including assessment, rehabilitation planning, goal setting, providing interventions, reviewing and reassessing, service liaison, supporting RTW and completing documentation [Citation36]. These components were aligned with the implementing service’s model of care and workflow [Citation41] to create the structure of the ABI VR framework, which consists of five specific phases of rehabilitation activity. The first four phases are cyclical and involve Assessment, Goal setting and rehabilitation planning, Intervention, and Monitoring and evaluation. The final phase of the framework is Discharge (including discharge planning and onward referrals). The cyclical structure allows clients to undertake additional specific vocational activities and repeat phases of the framework as their rehabilitation progresses and skills change (e.g., undertake specific assessments to support RTW later in the program).

The key findings identified across study phases one to four regarding the VR activities, processes and clinical service delivery for adults with ABI with vocational goals were combined and organised into the five clinical phases of the framework. Forty-nine specific elements were determined from the findings (see Appendix 1) and synthesized into the framework, guided by the specific clinical context for implementation. Over 87% (43/49) of the framework components were identified from two or more studies/investigated evidence bases. The elements included in the framework also align with the international ABI VR literature and current evidence base, including identified models, processes and components of VR [Citation18]; consumer experiences and factors influencing RTW [Citation5–9,Citation11,Citation12,Citation24,Citation26,Citation59,Citation60]; and clinician experiences and service delivery factors [Citation16,Citation17,Citation38,Citation60–63].

Delivery of the framework elements involves components of both case coordination and program-based VR [Citation19] delivered through a hybrid model of ABI VR, plus specific service delivery features required from the treating team.

The identified case coordination activities occur across all five phases and form the top section of the framework. These are implemented through a designated vocational coordinator role. The vocational coordinator is a member of the treating team (occupational therapist) and is responsible for coordinating the interdisciplinary VR program.

Program-based VR: A range of VR activities are delivered across the five phases by the interdisciplinary team (program-based VR), as detailed in the middle section of the framework. These occur primarily through team-based activities, with the majority of activity occurring prior to commencing graded RTW/workplace trials.

The key service delivery features that underpin the framework and occur across all five phases are presented in the bottom section. These apply to the treating team, and include (a) timing and access to ABI VR, through its availability to all clients with vocational goals for the duration of their rehabilitation program, (i.e., early transitional community rehabilitation for 12 weeks); (b) utilising a coordinated interdisciplinary approach, which involves skilled clinicians, positive therapeutic relationships and a culture of positive belief for RTW; and (c) responsiveness and support for family factors (e.g., relationships, early adjustment) as a component of team-based rehabilitation to support VR.

The majority of framework elements apply to all clients with vocational goals, with specific elements identified for clients predicted to RTW on-program. This is detailed in the following section.

Supporting implementation of the framework to practice

The ABI VR framework includes reference to specific clinical processes and tools designed to support the implementation of the framework into practice within the study service context. As the framework supports the delivery of ABI VR to all clients who express goals of returning to work, regardless of readiness, clients are ‘streamed’ for their ABI VR program by their treating team. This clinical decision is informed by information identified across the framework including factors that influence RTW (e.g., clinical presentation, workplace factors, social supports) which determines the focus of the client’s ABI VR program and activities undertaken. Stream ‘A’ clients are expected to RTW in some capacity during their 12 week rehabilitation program; stream ‘B’ clients are predicted to RTW within 12 months; and stream ‘C’ clients are predicted to RTW in more than 12 months. Clients’ predicted VR stream may change during their rehabilitation program. All programs involve discharge planning for ongoing services to support long-term VR and RTW goals.

Specific documentation processes and tools detailed in the framework include formal consent forms for employer contact and a ‘vocational profile’ document, which are completed by the treating team. The vocational profile document details the client’s vocational information, strengths and strategies for the workplace. It acts as a communication and handover tool for future therapists, supporting the future provision of ABI VR post-service discharge.

Additional clinical tools and processes have been developed to aid the implementation of the ABI VR framework by the interdisciplinary team and contextualise service delivery for clients, in line with KTA processes [Citation49]. These include templates for workplace visit risk assessments and documentation, guidelines for priority neuropsychological assessment, plus identified (discipline-specific) assessments and interventions for different client streams.

Discussion

This study has detailed the development of an evidence-based framework to support the delivery of consistent, interdisciplinary ABI VR during transitional community rehabilitation. By including evidence from all components of the EBP-4 model [Citation35], the framework has addressed specific findings related to the study context of Queensland ABI and VR services, including identified gaps in service delivery, experiences with previous services and views on ‘ideal’ services, from both consumers (clients and S/Os) and clinicians. This process should also support the translation and implementation of the framework to clinical practice, as the majority (>87%) of framework components were identified from two or more investigated EBP-4 [35] components and study phases (see Appendix 1). While the framework has been designed for a specific Australian clinical context, this research has relevance to clinical practice and service design across other contexts and settings, as framework components align with the international literature and evidence base across the areas of consumer experiences and factors influencing RTW [Citation5–9,Citation11,Citation12,Citation24,Citation26,Citation59,Citation60]; models, processes and components of VR [Citation18]; and service delivery factors and clinician experiences [Citation16,Citation17,Citation38,Citation60–63].

The framework primarily uses aspects of two traditional ABI VR models, case-coordination and program-based VR [Citation19]. This addresses international recommendations for the need for dedicated ABI VR program coordination [Citation27] and aligns with identified ABI VR service delivery practices and needs in Queensland [Citation31]. The need for a vocational coordinator role during ABI VR was identified by Queensland clinicians across public and private services; traditionally, this is provided by privately funded VR services [Citation31], typically occurring later in recovery/rehabilitation. In addition to program coordination, the VR coordinator undertakes specific liaison activities, which were identified as either service gaps or components of ideal services by consumers with ABI [Citation33] and clinicians [Citation31], including employer liaison and contact, and being a key liaison for all stakeholders. This supports best-practice recommendations of involving a range of stakeholders in ABI VR, including the client, the employer and the interdisciplinary team [Citation27]. In practice, the VR coordinator role may be a designated clinician in a publicly funded rehabilitation team (e.g., occupational therapist, psychologist), or a designated private provider for clients accessing either funded or mixed (funded and public) services (e.g., vocational occupational therapist, rehabilitation counsellor). Identifying which professional(s) should ideally undertake the VR coordinator role and the potential requirements of this role will involve consideration of available professionals (including experience and qualifications) and scope of practice, plus service and funding context. This is an identified area for future research.

While the use of a supported employment or ‘place and train’ approach [Citation19] to ABI VR was not reported by Queensland clinicians [Citation31] the developed framework does include some aspects of this model that are detailed within the evidence base [Citation18,Citation19,Citation63] and align with areas of practice identified across study phases 1–4 [Citation18,Citation31,Citation33]. This includes liaising with employers or service providers to support job placement (which may include ‘job seeking’ services such as Disability Employment Support services), providing therapy and support during RTW/job placements, and providing monitoring, advice and support for clients with long-term RTW goals and VR needs. These features may assist clinicians to deliver components of this approach and to provide longer-term VR services and support to clients with ABI.

The process of VR and RTW for adults with ABI can require long-term timeframes and support [Citation17], with different client readiness at different stages of rehabilitation. The framework has been developed to be cyclical to allow clients to progress through the different vocational rehabilitation streams and related rehabilitation activities, and support the provision of VR across a service continuum (e.g., clients may require further assessment, goal planning and/or different interventions over time). While the framework was developed to be implemented within a time-limited service, it is envisaged that its cyclical nature supports its translation and implementation by other rehabilitation services or providers, at differing time points.

ABI VR is recognised as a specialised rehabilitation service [Citation5–7] and Australian brain injury clinicians have previously identified the need for education and support for providing ABI VR [Citation30,Citation31]. The developed framework helps to address this need by providing a structure for the delivery of consistent VR, detailing specific VR processes and activities to be undertaken, and including information on VR roles and timing. This is particularly relevant to support the provision of more complex and specialised VR interventions (e.g., workplace assessments) which were reported to be performed inconsistently by local rehabilitation clinicians (phase three participants) [Citation31]. Additionally, with recently established state and national insurance schemes, adults with ABI should have increased access to funded private providers to provide ABI VR and support their RTW goals, when compared with previously reported experiences [Citation33]. While the lack of experienced private ABI VR providers in Australia has previously been identified [Citation24], this framework should support community clinicians to identify evidence-based processes and activities for VR and positively influence their delivery of VR to clients with ABI.

It is anticipated that supporting clinician skill development and delivery of ABI VR will positively impact consumer experiences and satisfaction with services. Further, including clinician-specific factors in the framework also addresses findings from consumers (in phases two and four) regarding the importance of clinician expertise, skill, and positive therapeutic relationships for ABI VR. These factors support prior consumer-focussed research which identified the importance of clinician expertise in community ABI rehabilitation for adults with ABI [Citation64–66], the therapeutic working alliance for ABI VR and RTW and having ‘faith’ in rehabilitation professionals [Citation5,Citation59].

The service delivery feature of providing ABI VR within a positive culture of hope and belief for RTW is supported by previous research findings on the importance of hope during ABI rehabilitation, its potential positive impact on outcomes, the need for hope to be fostered by clinicians [Citation67] and clinical frameworks of family-directed ABI rehabilitation where hope is a key component [Citation68]. Family and S/Os have been included specifically in the framework, in addition to being included in any ‘stakeholder’ activity within ABI VR, as has previously been recommended [Citation62]. This aligns with the contextual client and family-centric model of care used in the implementing service [Citation41] and acknowledges the positive influence of family and social supports on RTW for adults with ABI [Citation7,Citation9,Citation59].

Translation of the framework

While the framework has been designed to support the delivery of ABI VR as a component of a rehabilitation program within a specific context, it is envisaged that the early interdisciplinary ABI VR framework will translate to other services and settings and has the potential to translate beyond an Australian context. This includes services where ABI rehabilitation is provided under the ICF [Citation34] and within designated rehabilitation standards [Citation36,Citation69] and in areas where VR could be provided as a component of an existing ABI rehabilitation program. This is an identified future research direction.

Translating and implementing the framework to other rehabilitation services and settings is supported through KTA [Citation49] and EBP-4 [Citation35] processes. This may include reviewing the components of the framework in line with the context of the other service, including aspects currently provided and possible areas for service expansion, developing clinical tools specific to the service and context [Citation49] and including any specific local evidence (e.g., from clinicians or consumers) to support contextual implementation [Citation35]. At the level of individual clinical practice, clinicians may utilise the framework to reflect on their personal service provision, either across the phases of activity or through the service delivery features, or the integration of their role within team-based practices to improve service delivery. This should support clinicians to provide and tailor ABI VR services and programs to meet individual client needs, and positively impact RTW outcomes [Citation27].

The framework should also support transitions and handovers between services, including communicating the components of VR that have occurred and those required in the future. For example, if utilized by an inpatient rehabilitation team, a vocational coordinator would be appointed from within the team and would conduct early stakeholder liaison and employer contact. This may assist early job retention for severely injured clients, and ensure families do not resign clients from their work role early post-injury [Citation33]. The rehabilitation team would commence ABI VR (i.e., assessment, goal setting and rehabilitation planning, intervention/therapy), including identifying the vocational stream of the client and developing and implementing a VR rehabilitation plan and activities. Specific VR discharge planning and handover would then occur when the client discharges from inpatient rehabilitation and transitions to the community, and the next rehabilitation service (e.g., community or private rehabilitation) would continue to provide and progress VR utilising the framework to guide service delivery and subsequent future handover and service transitions.

Limitations

While the framework focuses on providing VR to support adults with ABI with RTW goals early post-injury, it may not fully address the needs of adults with ABI who have already returned to employment, including maintaining employment or supporting clients with changes to work roles [Citation2,Citation70]. Further, while the framework has been developed for people with ABI, its application to other neurological populations or disability groups is currently unknown. The small data set in phase four (two significant others) is a limitation, however, the key findings aligned with those from phase 2 (experiences of adults with ABI) and phase 3 (experiences of health professionals), supporting their inclusion within framework development.

Conclusion

A framework has been developed to support the delivery of ABI VR as a component of transitional community ABI rehabilitation, utilising both a broad and contextual evidence base. The framework aims to improve the consistency of ABI VR service delivery, impacting client experiences and potentially influencing future outcomes. While formal evidence on its implementation and effectiveness within the developed context is not available for reporting, this is an identified research direction. The framework should also be a useful tool for ABI clinicians and teams, supporting them to deliver VR as a component of ABI rehabilitation (from delivering aspects of the framework as services allow to providing all included components consistently). The framework may also assist clinicians and rehabilitation services to consider the breadth of ABI VR components and activities in their current service provision and inform future service change.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the individuals involved in this research - adults with lived experience of ABI, their significant others, and the health and rehabilitation professionals, who have generously shared their experiences, views and time across these studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Disability in Australia: acquired brain injury. Canberra: AIHW; 2007.

- van Velzen JM, van Bennekom CA, Edelaar MJ, et al. How many people return to work after acquired brain injury?: a systematic review. Brain Inj. 2009;23(6):473–488. doi: 10.1080/02699050902970737.

- Watkin C, Phillips J, Radford K. What is ‘retun to work’ following traumatic brain injury? Analysis of work outcomes 12 months post TBI. Brain Inj. 2020;34(1):68–77. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2019.1681512.

- Saunders SL, Nedelec B. What work means to people with work disability: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(1):100–110. doi: 10.1007/s10926-013-9436-y.

- Shames J, Treger I, Ring H, et al. Return to work following traumatic brain injury: trends and challenges. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(17):1387–1395. doi: 10.1080/09638280701315011.

- van Velzen JM, van Bennekom CA, van Dormolen M, et al. Factors influencing return to work experienced by people with acquired brain injury: a qualitative research study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(23-24):2237–2246. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.563821.

- Libeson L, Downing M, Ross P, et al. The experience of return to work in individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI): a qualitative study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020;30(3):412–429. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2018.1470987.

- Donker-Cools BHPM, Wind H, Frings-Dresen MHW. Prognostic factors of return to work after traumatic or non-traumatic acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(8):733–741. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1061608.

- Donker-Cools BHPM, Schouten MJE, Wind H, et al. Return to work following acquired brain injury: the views of patients and employers. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(2):185–191. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1250118.

- Meulenbroek P, Bowers B, Turkstra LS. Characterizing common workplace communication skills for disorders associated with traumatic brain injury: a qualitative study. J Vocat Rehabil. 2016;44(1):15–31. doi: 10.3233/JVR-150777.

- Rubenson C, Svensson E, Linddahl I, et al. Experiences of returning to work after acquired brain injury. Scand J Occup Ther. 2007;14(4):205–214. doi: 10.1080/11038120601110934.

- Macaden AS, Chandler BJ, Chandler C, et al. Sustaining employment after vocational rehabilitation in acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(14):1140–1147. doi: 10.3109/09638280903311594.

- Tyerman A, Meehan M, Tuner-Stokes L. Vocational assessment and rehabilitation after acquired brain injury: inter-agency guidelines. London: British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine; 2004.

- Vocational Rehabilitation Association UK. VRA standards of practice and code of ethics for vocational rehabilitation practitioners. 2nd Edition. Doncaster: vocational Rehabilitation Association; 2013.

- Baldwin C, Brusco NK. The effect of vocational rehabilitation on return-to-work rates post stroke: a systematic review. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18(5):562–572. doi: 10.1310/tsr1805-562.

- Radford K, Sutton C, Sach T, et al. Early, specialist vocational rehabilitation to facilitate return to work after traumatic brain injury: the FRESH feasibility RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2018;22(33):1–124. doi: 10.3310/hta22330.

- Ownsworth T. A metacognitive contextual approach for facilitating return to work following acquired brain injury: three descriptive case studies. Work. 2010;36(4):381–388. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2010-1041.

- Murray A, Watter K, McLennan V, et al. Identifying models, processes and components of vocational rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: a systematic scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(24):7641–7654. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1980622.

- Fadyl JK, McPherson KM. Approaches to vocational rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury: a review of the evidence. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24(3):195–212. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181a0d458.

- Tyerman A. Vocational rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury: models and services. Neurorehabilitation. 2012;31(1):51–62. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2012-0774.

- Schwarz B, Claros-Salinas D, Streibelt M. Meta-Synthesis of qualitative research on facilitators and barriers of return to work after stroke. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(1):28–44. doi: 10.1007/s10926-017-9713-2.

- Dodson MB. A model to guide the rehabilitation of high-functioning employees after mild brain injury. Work. 2010;36(4):449–457. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2010-1044.

- Stergiou-Kita M, Rappolt S, Kirsh B, et al. Evaluating work readiness following acquired brain injury: building a shared understanding. Can J Occup Ther. 2009;76(4):276–284. doi: 10.1177/000841740907600406.

- McRae P, Hallab L, Simpson G. Navigating employment pathways and supports following brain injury in Australia: client perspectives. Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling. 2016;22(2):76–92. doi: 10.1017/jrc.2016.14.

- Gilworth G, Carey A, Eyres S, et al. Screening for job loss: development of a work instability scale for traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2006;20(8):835–843. doi: 10.1080/02699050600832221.

- Gilworth G, Eyres S, Carey A, et al. Working with a brain injury: personal experiences of returning to work following a mild or moderate brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(5):334–339. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0169.

- Hoeffding LK, Nielsen MH, Rasmussen MA, et al. A manual-based vocational rehabilitation program for patients with an acquired brain injury: study protocol of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial (RCT). Trials. 2017;18(1):371–371. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2115-0.

- Phillips J, Radford K. Vocational rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury: what is the evidence for clinical practice? Advances in Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation: ACNR. 2014;4(5):14–16.

- Johnston V, Brakenridge C, Valiant D, et al. Using framework analysis to understand multiple stakeholders’ views of vocational rehabilitation following acquired brain injury. Brain Impairment. 2022;1–24. doi: 10.1017/BrImp.2022.27.

- Pagan E, Ownsworth T, McDonald S, et al. A survey of multidisciplinary clinicians working in rehabilitation for people with traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment. 2015;16(3):173–195. doi: 10.1017/BrImp.2015.34.

- Watter K, Murray A, McLennan V, et al. Clinician perspectives of ABI vocational rehabilitation in Queensland. Brain Impairment. 2023;1–24. doi: 10.1017/BrImp.2023.6.

- Queensland Health. Statewide adult brain injury rehabilitation health service plan 2016-2026. Brisbane: Queensland Health System, Policy and Planning Division; 2016.

- Watter K, Kennedy A, McLennan V, et al. Consumer perspectives of vocational rehabilitation and return to work following acquired brain injury. Brain Impairment. 2022;23(2):164–184. doi: 10.1017/BrImp.2021.4.

- World Health Organisation. International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2001.

- Hoffman T, Bennett S, Del Mar C. Evidence-based practice across the health professions. 3rd ed. Sydney: Elsevier; 2017.

- Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine. Standards for the provision of rehabilitation medicine services in the ambulatory setting. Sydney: Royal Australasian College of Physicians; 2014.

- Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine. Standards for the provision of inpatient adult rehabilitation medicine services in public and private hospitals. Sydney: Royal Australasian College of Physicians; 2019.

- Van Velzen JM, Van Bennekom CA, Frings-Dresen MH. Availability of vocational rehabilitation services for people with acquired brain injury in Dutch rehabilitation institutions. Brain Inj. 2020;34(10):1401–1407. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2020.1802778.

- Burns SP, Schwartz JK, Scott SL, et al. Interdisciplinary approaches to facilitate return to driving and return to work in mild stroke: a position paper. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2018;99(11):2378–2388. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.01.032.

- Mitchell L, Boak G. Developing competence frameworks in UK healthcare: lessons from practice. J Euro Ind Train. 2009;33(8/9):701–717. doi: 10.1108/03090590910993580.

- Division of Rehabilitation. Acquired Brain Injury Transitional Rehabilitation Service Model of Care. Brisbane: Metro South Health, Queensland Health; 2020. Available from: https://metrosouth.health.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/abitrs-model-care.pdf.

- Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2(7872):81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0.

- Teasell R, Bayona N, Marshall S, et al. A systematic review of the rehabilitation of moderate to severe acquired brain injuries. Brain Inj. 2007;21(2):107–112. doi: 10.1080/02699050701201524.

- Teasell R, Marshall S, Cullen N, et al. Introduction and methodology. In: Teasell R, Marshall S, Cullen N, editors. Evidence-based review of moderate to severe acquired brain injury. Version 15.0. 2022. p. 1–14. Available from: https://erabi.ca/modules/module-1/

- Haydel MJ. Evaluation of traumatic brain injury, acute. BMJ Best Practice. 2023. Available from: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/515

- Borg D, Nielsen M, Kennedy A, et al. The effect of access to a designated interdisciplinary post-acute rehabilitation service on participant outcomes after brain injury. Brain Inj. 2020;34(10):1358–1366. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2020.1802660.

- Bohan JK, Nielsen M, Watter K, et al. “It gave her that soft landing”: consumer perspectives on a transitional rehabilitation service for adults with acquired brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2023;33(6):1144–1173. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2022.2070222.

- Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, et al. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health; 2011.

- Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655.

- Craig P, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: reflections on the 2008 MRC guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(5):585–587. ():doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.009.

- Mohler R, Kopke S, Meyer G. Criteria for reporting the development and evaluation of complex interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2). Trials. 2015;16(:204. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0709-y.

- Agency for Clinical Innovation. Understanding the process to develop a model of Care - An ACI framework. Sydney: NSW Government; 2013.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Vaismoradi M, Snelgrove S. Theme in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2019;20(3), Art. 23. doi: 10.17169/fqs-20.3.3376.

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health researchers. London: SAGE Publications; 2004.

- Sherer M, Bergloff P, Boake C, et al. The awareness questionnaire: factor structure and internal consistency. Brain Inj. 1998;12(1):63–68. doi: 10.1080/026990598122863.

- Park J, Roberts M, Esmail S, et al. Validation of the readiness for return-to-work scale in outpatient occupational rehabilitation in Canada. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(2):332–345. doi: 10.1007/s10926-017-9721-2.

- Hooson JM, Coetzer R, Stew G, et al. Patients’ experience of return to work rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury: a phenomenological study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2013;23(1):19–44. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2012.713314.

- Kendall E, Muenchberger H, Gee T. Vocational rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury: a quantitative synthesis of outcome studies. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2006;25(3):149–160.

- Dillahunt-Aspillaga C, Jorgensen Smith T, Hanson A, et al. Exploring vocational evaluation practices following traumatic brain injury. Behav Neurol. 2015;2015:924027. doi: 10.1155/2015/924027.

- Stergiou-Kita M, Yantzi A, Wan J. The personal and workplace factors relevant to work readiness evaluation following acquired brain injury: occupational therapists’ perceptions. Brain Inj. 2010;24(7-8):948–958. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2010.491495.

- Hart T, Dijkers M, Whyte J, et al. Vocational interventions and supports following job placement for persons with traumatic brain injury. J Vocl Rehab. 2010;32(3):135–150. doi: 10.3233/JVR-2010-0505.

- Piccenna L, Lannin N, Gruen R, et al. The experience of discharge for patients with an acquired brain injury from the inpatient to the community setting: a qualitative review. Brain Inj. 2016;30(3):241–251. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2015.1113569.

- Christie L, Egan C, Wyborn J, et al. Evaluating client experience of rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: a cross-sectional study. Brain Inj. 2021;35(2):215–225. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2020.1867768.

- Dawes P, Arru P, Corry R, et al. Patient reported experiences of using community rehabilitation and/or support services whilst living with a long-term neurological condition: a qualitative systematic review and meta-aggregation. Int J Audiol. 2022;41(23):1–9. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1473508.

- Kuipers P, Doig E, Kendall M, et al. Hope: a further dimension for engaging family members of people with ABI. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;35(3):475–480. doi: 10.3233/NRE-141139.

- Fisher A, Bellon M, Lawn S, et al. Family-directed approach to brain injury (FAB) model: a preliminary framework to guide family-directed intervention for individuals with brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(7):854–860. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1407966.

- British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine. BSRM standards for rehabilitation services, mapped onto the national services framework for long-term conditions. London: BSRM; 2009.

- Oppermann JD. Interpreting the meaning individuals ascribe to returning to work after traumatic brain injury: a qualitative approach. Brain Inj. 2004;18(9):941–955. doi: 10.1080/02699050410001671919.

Appendix 1.

Evidence base for the ABI VR framework

Appendix 2.

Phase four – significant others experiences of ABI VR

Phase four explored the views of significant others (S/Os) regarding their partner’s ABI VR experience, through an online survey involving open-ended questions and free-text responses. The S/Os were the partners of the phase two participants (adults with ABI, n = 8). Three of the eight participants with ABI identified a S/O who could participate; only two S/Os participated in the study. Details of the participating S/Os (n = 2) are provided in below. The survey questions were developed by the research team, involving experienced ABI and VR researchers and clinicians. Questions were designed to complement those asked of phase two participants [Citation33] plus identify S/O-specific factors that may influence RTW [Citation7,Citation9,Citation59]. The online survey involved 10 questions regarding S/O’s views of their partner’s RTW goals and VR experiences, S/O’s satisfaction with this rehabilitation, the impact of the ABI on the S/O, recommendations for future services, with space for additional information or comments; demographic information was also collected. Questions were open-ended and required text-level responses. The online survey is provided in Appendix 3. The data were analysed by authors VM and KW using thematic analysis [Citation54,Citation56], with agreement in coding reached. While the data set was small, three themes emerged from the analysis – ‘Importance of work’, ‘No journey is the same’ and ‘Areas for change’.

Table 2. Significant other demographics.

Importance of work

Both S/Os reported their partner had vocational goals early post-injury which were recognised as having the “utmost importance” (S/O2) for both the individual with ABI and their S/O. The goal of RTW influenced motivation and drive, as reported by S/O1: “Extremely important and was the main driving force through his recovery”. This goal was also identified by participants as being important to their relationship with their partner with ABI, including providing a positive outlook: “[it] allowed him to stay positive while he was working towards those goals” (S/O1).

No journey is the same

Varied S/O experiences with their partner’s VR and RTW were reported. S/O2 identified an overwhelmingly negative experience, reporting an absence of early and post-hospital rehabilitation, nil vocational rehabilitation, no employer liaison and a negative initial RTW experience which focussed on termination, with disagreement between the manager and the RTW coordinator: “that company should have offered a graded return to work program instead of being fired”. S/O1 reported satisfaction with their partner’s rehabilitation and VR from early in recovery (sub-acute rehabilitation) through to outpatient services, including clinicians linking with the employer and HR, and satisfaction with staff skill: “all of the staff were amazing”. However, S/O1 identified her partner with ABI did not receive enough support targeting higher level skills or post-discharge supports: “I do feel that higher level cognitive activities that were important to [his] work were not as addressed”.

Areas for change

Both S/O1 and S/O2 identified a number of areas for service improvement and future service delivery for ABI VR, including the need for better access to rehabilitation post-discharge and more rehabilitation across time points, including “post-discharge assessment and identification of deficits to assist with a plan to rehab cognition and then plan for RTW” (S/O2). S/Os also identified the need for ongoing therapeutic support, community supports and longer-term access to rehabilitation, as “rehabilitation [is] still needed” (S/O1) and requires a “co-ordinated approach from rehab to employer” (S/O2). Additionally, S/O1 highlighted the need for clinical staff to demonstrate a positive culture of belief and expectancy for returning to work following ABI: “a lot of negative language from allied health, nurses and doctors about his lack of recovery and how he is unlikely to succeed - this didn’t motivate him, but rather brought him down”. Lastly, both S/Os identified a number of additional impacts of the ABI, including the impact on their own vocational status and on relationships.

Key findings from the results above were used to inform the development of the ABI VR framework, as summarised in the Results section, with further details included in Appendix 1.