Abstract

Purpose

Stroke survivors often live with significant treatment burden yet our ability to examine this is limited by a lack of validated measurement instruments. We aimed to adapt the 60-item, 12-domain Patient Experience with Treatment and Self-Management (PETS) (version 2.0, English) patient-reported measure to create a stroke-specific measure (PETS-stroke) and to conduct content validity testing with stroke survivors.

Materials and Methods

Step 1 – Adaptation of PETS to create PETS-stroke: a conceptual model of treatment burden in stroke was utilised to amend, remove or add items. Step 2 - Content validation: Fifteen stroke survivors in Scotland were recruited through stroke groups and primary care. Three rounds of five cognitive interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Framework analysis was used to explore importance/relevance/clarity of PETS-stroke content. COSMIN reporting guidelines were followed.

Results

The adapted PETS-stroke had 34 items, spanning 13 domains; 10 items unchanged from PETS, 6 new and 18 amended. Interviews (n = 15) resulted in further changes to 19 items, including: instructions; wording; item location; answer options; and recall period.

Conclusions

PETS-stroke has content that is relevant, meaningful and comprehensible to stroke survivors. Content validity and reliability testing are now required. The validated tool will aid testing of tailored interventions to lessen treatment burden.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Treatment burden is reported by stroke survivors but no stroke-specific measure of treatment burden exists.

We adapted an existing measure of treatment burden for use in multimorbid patients (PETS) to create a stroke specific version (PETS-stroke).

The items in PETS-stroke are relevant and meaningful to people with stroke.

Further testing will examine construct validity, reliability, and useability.

This measure will be useful in future RCTs to measure treatment burden and to identify stroke patients who are at high risk of treatment burden.

Introduction

Stroke affects an estimated 17 million people worldwide and is recognised as a leading cause of disability in adults [Citation1,Citation2]. Demographic projections estimate that the number of people living with stroke in the EU will increase by 25% to around 4.6 million in 2035 [Citation1]. Physical post-stroke sequalae can be life altering, with approximately 60% of stroke survivors living with limb weakness, 70% with speech difficulties and 30% with urinary incontinence [Citation3]. A UK-based study identified that stroke survivors live with a range of unmet needs including poor mobility, falls, incontinence, fatigue and emotional difficulties [Citation4]. Additionally, it is estimated that around two thirds of stroke survivors experience cognitive decline [Citation5]. The optimisation of stroke management could positively impact and increase quality of life for many people on a global scale. Stroke treatments have advanced greatly in recent decades, including acute treatments, rehabilitative therapies and supported self-management, and methods of secondary prevention. However, these treatments can be complex and demanding, placing a resultant burden of treatment onto the stroke survivor [Citation6,Citation7].

‘Treatment burden’ is defined as the workload of healthcare from the perspective of people with long-term conditions and its impact on functioning and wellbeing [Citation8]. The term encompasses the demands made by healthcare professionals and the day-to-day tasks of health management [Citation9]. Stroke survivors are expected to adhere to often complicated, multi-faceted treatment regimens. This can involve healthcare work such as strict adherence to medications, appointment attendance, maintenance of physical mobility through recommended exercises and monitoring of dietary intake. Additionally, retaining information regarding medication and diet, enduring side effects of treatments, finding the time to attend appointments and planning associated travel may pose mental, physical and financial challenges. Treatment burden after stroke is likely to be associated with reduced adherence to treatments and poor health-related outcomes such as mortality, however a lack of validated tools to measure treatment burden in people who have survived a stroke has precluded examination of this [Citation10–12]. Treatment burden can also be experienced by the carers of stroke survivors, with an estimated prevalence of between 25–54% [Citation13].

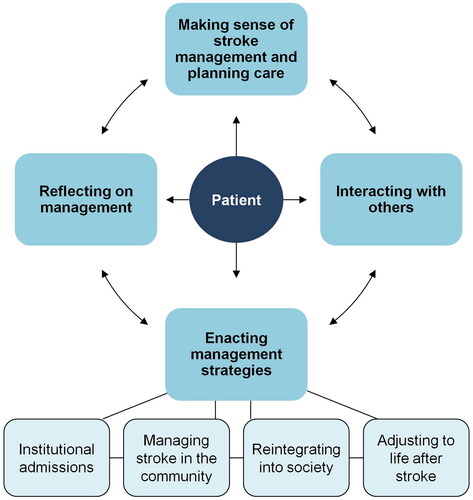

Figure 1. Conceptual model of stroke treatment burden.

We previously created a conceptual model and taxonomy of treatment burden in stroke (see ) through a systematic review of qualitative research and interviews with stroke survivors [Citation6,Citation7]. This work demonstrated that treatment burden can arise as a consequence of a high healthcare workload i.e. all the different activities recommended by healthcare professionals in order to maintain or improve health [Citation7,Citation9,Citation14]. It may also arise from care deficiencies i.e. aspects of care that did not meet the needs or expectations of stroke survivors such as long waiting times [Citation6]. Both healthcare workload and care deficiencies can influence and be influenced by patient capacity, which in this context refers to the ability of stroke survivors to adhere to their management plan and engage with health professionals [Citation6]. Four types of treatment burden have previously been identified: (1) making sense of stroke management e.g. seeking information; (2) interacting with others e.g. arranging healthcare appointments; (3) enacting management strategies e.g. taking medications; and (4) reflecting on management e.g. monitoring progress of recovery [Citation6,Citation7]. Treatment burden is increasingly recognised as a barrier to advancing a patient’s goals in health and life, especially for patients with complex health needs resulting from long-term conditions [Citation15].

Several patient reported measures (PRM) of treatment burden have been developed. The Patient Experience with Treatment and Self-Management (PETS) (version 2.0, English) questionnaire is one such measure [Citation16], developed for use in patients with multiple chronic conditions and/or complex self-care and subsequently validated in other groups e.g. patients with type 1 or 2 diabetes [Citation10,Citation16–18]. Other PRMs of treatment burden include: the Treatment Burden Questionnaire (TBQ), validated in a sample group of patients with chronic conditions [Citation19,Citation20]; the Diabetic Treatment Burden Questionnaire (DTBQ), validated in patients with type 2 diabetes [Citation21]; and the Multimorbidity Treatment burden questionnaire (MTBQ) which has been validated in patients with multimorbidity [Citation22]. However none have been validated in a stroke population, and none comprehensively address the treatment burdens reported by stroke survivors [Citation9] as detailed in our published conceptual model [Citation7].

PRMs of treatment burden are based on formative models, meaning that the intention is to capture a wide range of healthcare-related problems that can contribute to the experience of treatment burden, but these are not necessarily correlated to one other, and may differ between populations. Specific aspects of treatment burden reported by stroke survivors that are not represented in existing general measures include obtaining walking aids, making adaptations to the home, struggling to attend appointments due to reduced mobility, and returning to work and driving [Citation7]. While much research has been conducted to investigate treatment burden in stroke patients qualitatively, a PRM allowing for standardised measurement has not yet been developed [Citation9]. A systematic review of PRMs in stroke found none that measured treatment burden comprehensively [Citation6]. It is standard practice to adapt generic PRMs for use in index conditions such as stroke, e.g. the Stroke Adapted Sickness Impact Profile [Citation23].

This study aims to adapt and validate the content of the Patient Experience with Treatment and Self-Management in stroke measure (PETS-stroke), a new PRM adapted from the existing PETS measure, that can be used to measure treatment burden in stroke. The conceptual model of treatment burden underpinning PETS fits closely with our own () and hence we chose this measure for adaptation [Citation7,Citation8]. The PETS assesses treatment burden in people with multimorbidity. It is a paper and pencil survey that includes items (answered on a Likert scale) on treatment burdens such as medications and appointments. It was developed and validated using rigorous psychometric methods [Citation10,Citation16,Citation18]. However, it lacks stroke-specific content, and the length of the measure (60 items) may be challenging for stroke survivors to complete due to issues such as cognitive difficulties, fatigue, low mood and physical disabilities [Citation1]. We have therefore adapted the PETS measure to create a stroke-specific version (PETS-stroke) and validated the content in a UK stroke survivor population [Citation24,Citation25]. Our research questions were:

What items should be included in the adapted PRM?

Is the content of the adapted PRM important, relevant, and understandable to stroke survivors?

Does the adapted PRM cover all aspects of perceived treatment burden that is important to stroke survivors?

Materials and methods

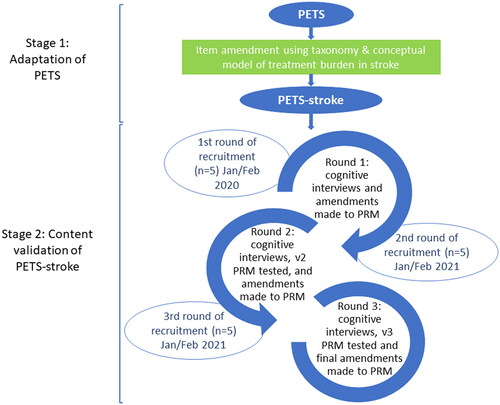

A formal reporting guideline suitable for use in studies involving patient-reported outcome measures – COSMIN – was utilised for this study [Citation26]. shows our study processes. We utilised our conceptual model and taxonomy of treatment burden in stroke [Citation7] to adapt the existing 60-item PETS measure (version 2.0) to include aspects of treatment burden relevant to stroke survivors (see Step 1 below– Adaptation of PETS to create PETS-Stroke) [Citation6,Citation7]. The resultant modified PRM was then tested in three rounds of cognitive interviews with stroke survivors (see Step 2 – content validation).

Figure 2. Stages of content validation.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the ethics committee at the University of Glasgow (College of Medical, Veterinary & Life Science) and NHS London Surrey Border Research Ethics Committee (REC Reference − 20/LO/0871).

Step 1 – adaptation of PETS to create PETS-stroke

Members of the research team (AS, KG, FM) worked collaboratively to examine the items in PETS closely and compared them to the taxonomy and conceptual model of treatment burden in stroke [Citation6,Citation7], carefully noting any differences and similarities. The wording of items was then amended, items merged to reduce the overall number in the questionnaire or deleted if not relevant to stroke survivors. New items were added if a burden was noted to be in our taxonomy [Citation7] but not included in the PETS to ensure that the new PRM reflected treatment burdens relevant to stroke survivors. This took place over two team meetings with items in the PETS being adapted accordingly to create PETS-stroke.

Step 2 – content validation

Content validation of PETS-stroke was then assessed through cognitive interviews with stroke survivors. Cognitive interviewing is a technique commonly used in content validation of patient-reported outcome measures that involves collaboratively reading through the content of each item with the participant to establish if it is fit for purpose [Citation27]. Changes are then made to items based on feedback from participants [Citation27].

Participant recruitment

Purposive sampling was used in this study. The sampling frame aimed to recruit a varied group of stroke survivors according to gender, age, time since stroke and level of disability/aphasia. Inclusion criteria were: diagnosis of stroke, being able to read and communicate in English and being able to provide informed consent. Those with aphasia or mild cognitive difficulties were included. Participants had the option of being supported by a carer who could act as a proxy if helpful, however no participants opted to do this. Those with a terminal illness and prognosis under six months were excluded.

There is no consensus on sample size for content validity studies, rather it is advised that a pragmatic decision be made based on the measure and study population [Citation28]. As this was a qualitative study it did not aim to determine generalisability. In content validity testing it is useful to have rounds of interviews, each involving a small number of participants, with data analysis conducted between rounds to allow changes to be made to the measure before it is shown to the next group of individuals [Citation28]. We interviewed five participants in each round, as this was deemed a manageable amount of data that would provide useful information. Further rounds of interviews and revision of the PRM continued until the research team were satisfied that no further revision would be required based on feedback from participants. This was achieved after three rounds of interviews with a total of 15 stroke survivors.

To optimise recruitment, two methods were utilised. Recruitment for the first round of interviews was conducted through the Glasgow Stroke User Group, hosted by NHS Research Scotland (NRS). Participants were interviewed in person (n = 5) providing written consent at the time of interview. Participants in the second and third rounds were recruited via GP practices, facilitated by the NRS Primary Care Research Network. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic at the time of the second and third round of interviews, these were conducted via telephone (n = 7) or Microsoft Teams video calls (n = 3). Participants were sent consent forms by post or email to be returned by post to the research team. At the beginning of each interview, verbal consent was also obtained by reading the consent form aloud. Participants were provided with a £10 gift voucher as a token of thanks for their participation.

Data collection

There is no consensus on the correct way to conduct cognitive interviews [Citation29], therefore we utilised methods previously used by members of the research team when developing the PETS measure [Citation16].

Participants were provided with a copy of the pilot PETS-Stroke measure for reference during the interview. The researcher and participant worked through the measure from beginning to end, with the researcher reading instructions and items aloud and asking participants to reflect on three questions:

How important they felt the item was to their usual care. As an aid to discussion, they were asked to rate the item on a scale of 0 to 10 – corresponding to their perceived importance of the item (0 = no importance; 10 = highest importance).

How relevant the item was to their present state of health. They were also asked to comment on the recall period of the question (if a time frame was included).

How understandable the item was and if they had any difficulty making sense of the wording.

The rating of importance was intended to stimulate conversation and was not used as criteria for exclusion. At the end of the interview participants were invited to share their comments on any aspect of the survey, particularly any omitted aspects of treatment burden and also whether the instructions were easy to follow. Each interview lasted approximately 1 h (conducted by AS and KW), was audio recorded and later transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Framework analysis was considered the most suitable approach in this research. The structure of the framework i.e., importance, relevance, clarity and recall period of each item had been identified prior to data analysis [Citation30,Citation31]. NVivo 12 Pro software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Australia) and Microsoft Word (version 2017, Microsoft, USA) were utilised in the analysis.

Decisions to remove any item were based on the majority opinion of participants, strength of opinion related to key themes, and discussion between the research team (KG, AS, KW). The balance between relevance and importance among participant responses was also considered. For example, where most participants said an item was not relevant to them as an individual but they did consider the item to be important, it was not removed from the measure. Decisions to alter items were taken following discussion about participant feedback amongst the research team (KG, AS, KW). Where there was disagreement between participants’ responses and feedback, answers were scrutinised for possible reasons. Consideration was given to importance, relevance, clarity, response options, recall period and wording of instructions throughout the questionnaire.

Results

The results of the item adaptation of PETS are presented below, followed by the results of the cognitive interviews including findings related to importance, relevance, clarity, comprehensiveness and recall period.

Item adaptation

The 60-item PETS (included in Supplementary materials) was adapted to a 34-item PETS-stroke prototype. Some items were reworded to make them relevant to stroke or to accommodate for language differences between the UK and US e.g. ‘refill your medications’ was altered to ‘get your repeat medications’. Items were removed if content was not relevant in the UK e.g. navigating health insurance, or if not included in our stroke conceptual model e.g. monitoring blood sugars. Some items were removed to reduce the overall number of items and therefore the burden on the person completing it. For example, multiple questions about medication difficulties were removed and the item ‘how easy or difficult is it for you to take your medications as directed’ retained as it was felt that this would capture all medication issues. Similarly, various items asked how self-management limited social roles and responsibilities. These were replaced with one item asking ‘how much has looking after your health impacted your usual activities, roles and responsibilities’. Five items about mental fatigue asked how often self-management resulted in the person feeling angry, preoccupied, depressed, worn out, or frustrated, and these were replaced by one item: ‘how often does your self-management affect your mood?’.

Items were added if treatment burdens included in our published taxonomy and conceptual model were not in the original PETS. For example, a domain ‘care planning’ was added that included the items ‘how easy or difficult is it for you to set goals for recovery’ and ‘how easy or difficult is it for you to stay motivated to improve your health and functioning?’. The domain ‘medical equipment’ was changed to ‘living at home with stroke’ to encompass questions about walking aids, home adaptations and organising personal care. The ‘diet’ domain was merged with ‘exercise’ to create the domain ‘lifestyle’. This separated questions about exercise from those about physiotherapy, previously grouped together in PETS, as it was felt that these are different types of treatment work for stroke survivors. Items about returning to work and driving were added as these are relevant to stroke recovery but are not available in PETS. The recall period in PETS was 4 weeks, this was changed for some items to ‘since your stroke’ when it was felt that 4 weeks was unsuitable e.g. when asking about obtaining walking aids.

Lastly, the version of PETS that we were adapting (version 2.0) included yes/no screening questions for select domains (i.e. diet, exercise/physical therapy, and medical equipment) to allow respondents to skip certain questions they deem irrelevant. Due to concerns that this may result in relevant items being accidentally skipped, we opted to add in a ‘does not apply to me’ answer at the level of each item. This change has also been made in subsequent versions of the generic PETS measure to reduce the amount of missing responses to these items [Citation10].

The 60-item version of PETS had 12 domains and two single-item indicators of medication-related bother while the new 34-item PRM had 13 domains. shows the domains in PETS and PETS-stroke. Of the 34 items in the PETS-stroke, 10 were unchanged from PETS, 18 were amended PETS items and 6 were new items.

Table 1. Domains included in PETS and PETS-stroke.

Cognitive interviews

Participants

shows the characteristics of the 15 participants. There were a mix of male and female participants (male = 9), all were white (n = 15) and ages ranged from 51 to 88 years. Participants lived in areas representing a range of deprivation levels [Citation32], including 3 participants from the 20% most deprived data zones in Scotland and 2 participants from the 20% least deprived. Two participants reported that they had experienced their stroke in the last year. Several of the participants had experienced physical sequelae of their stroke, such as effects on their arm and hand function or walking. One participant reported aphasia. Most participants had at least one co-morbidity in addition to their stroke – the most common being atrial fibrillation (4 participants), arthritis, hypertension and osteoporosis (3 participants for each) - and most were taking multiple medications.

Table 2. Self-reported participant characteristics.

Items

shows the status of each item in PETS-stroke following the 15 cognitive interviews. In summary, no items were removed from the measure, while 15 items remained unchanged. A total of 18 items were altered due to concerns around relevance and clarity with changes also made to the instructions at the start of the questionnaire and the order of one item. The recall period was amended for all 34 items.

Table 3. Status of 34 PETS-stroke items post-content validation.

Interviewees felt the questionnaire covered all aspects of treatment burden that were important to stroke patients, commenting nothing had been omitted.

“…the questions are all very relevant…I couldn’t really think of any other questions that, that could be asked.” [Participant 15, Male, stroke ≤1 year ago]

“…I can’t think of anything off-hand.” [Participant 14, Female, stroke ≤1 year ago]

shows the items included in PETS-stroke following item adaptation, and the finalised items following cognitive interviews.

Importance

No changes were made based on importance. All items were considered important (score of ≥5) by the majority of participants. On careful examination of the qualitative feedback for items that received any scores of less than 5, it became apparent that many participants had subsequently stated the items were in fact important, but not to them personally.

Table 4. Items included in PETS-stroke following item adaptation and finalised items following cognitive interviews.

“It’s not important to me, but it might be important to 90% of the population” [Participant 10, Male, stroke >5 years ago, Item 19]

Relevance

No items were removed based on relevance however, several were amended. Various items were reported by participants as relevant only for a short time in the immediate aftermath of their stroke. Others reported that items had never been relevant due to their high level of physical functioning, for example they had not required the provision of walking aids or the support of carers during their recovery.

“At this time, again, I’m too far along the road, and not really got – pardon me -any goals written down…these were big goals at the start. But now I can, I accomplished them” [Participant 1, Male, stroke >1–5 years ago, Item 1]

“I’ve no idea, whether you struggle or not, I’ve not had…no I’ve not had, never had anything or done anything.” [Participant 2, Male, stroke >5 years ago, Item 18]

“So it doesn’t apply, I don’t think that applies to me. Because I have recovered from my stroke” [Participant 8, Male, time since stroke unknown, Item 3]

“…it doesn’t apply to me at all, I didn’t really lose any power, it was more coordination I lost.” [Participant 12, Male, stroke >5 years ago, Item 17]

While such items were not currently relevant to all participants, they were still thought to be important to others. For example, those experiencing greater levels of disability, those who were older or who had their stroke more recently.

“For me, not, but for other people, as I say, the worse the stroke, the more relevant it becomes.” [Participant 1, Male stroke >1–5 years ago, Item 20]

“…it’s not as relevant to me as it would be…or as it is to other people that I know…especially if you’re…a working age person who’s had a stroke…And it doesn’t really affect me a lot, but it does other people.” [Participant 4, Female, stroke >1–5 years ago, Item 19]

“Because it’s not relevant to me, but it’s very important, some people have big problems with this, it’s a very important item” [Participant 7, Male, time since stroke unknown, Item 18]

“No it’s not relevant. I don’t drive…It’s important for some people, ‘cause some people will drive so…” [Participant 11, Female, stroke >5 years ago, Item 33]

There was a strong feeling among participants that items were most relevant to individuals in the first year following their stroke.

The relevance of two items (Items: 14 and 15) which included reference to “healthcare provider…recommendations” were not relevant to several participants who reported they were either no longer, or had never been, in receipt of such recommendations. These participants often followed their own self-directed physical activity or healthy lifestyle regimes.

“I only had physio for I think about, is it, nine month or something like that, then it sort of stopped. Once you get home…your physiotherapy sometimes is the last thing you think about, you know?” [Participant 2, Male, stroke >5 years ago, Item 29]

“Yes. Totally relevant, apart from the fact that I don’t get any advice…” [Participant 7, Male, time since stroke unknown, Item 15]

“I don’t think it’s relevant, because I’ve had no advice on that, but I do have a routine which I do from my own awareness of things.” [Participant 10, Male, stroke >5 years ago, Item 15]

Alterations were made to the wording of these items to incorporate the burden of making lifestyle changes and maintaining them.

One item (Item 24) which referred to paying for medications was not relevant to the majority of participants, however most felt it was important and so it was not removed. In Scotland, most medications are available on prescription without monetary charge, leading one participant to question “it makes me wonder who needs to pay for medication?” (Participant 5, Female, stroke >5 years ago). However, cognisant of health care systems in other countries where paying for medications is the norm, it was felt important to retain this item in the measure.

Several participants indicated they would choose to answer ‘Does not apply to me’ to an item which was relevant, but the experience of burden was low.

“No, it’s…it’s not relevant, because I manage it quite easily. Okay. But you do get repeat prescriptions? Yes.” [Participant 15, Male, stroke ≤1 year ago, Item 6]

“No, it’s not relevant. I get home care provided by [Company] and that goes along very nicely, thank you.” [Participant 13, Male, stroke >1–5 years ago, Item 18]

Following discussion among the research team, the ‘does not apply’ answer was removed from some items (Items: 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30). For other items, it was retained as a potential answer where it was possible that some individuals would have no experience of that burden, for example questions relating to medication side effects (Item 9), obtaining mobility aids (Item 17) and organising carers (Item 18).

Recall period and time since stroke

Recall periods included in iterations of the adapted 34-item PETS-stroke measure ranged from four weeks to one year, and also ‘since your stroke’. However, many participants did not like the use of exact recall periods for certain questions and often felt they were not relevant to them.

The length of time since a participant’s stroke appeared to be the main factor influencing such responses. If an individuals’ stroke had occurred many years prior to the interview, even the recall period of one year was often not felt to be relevant. Findings suggested that items in the measure are most relevant in the first year following stroke.

“At the start of your stroke, yes, that’s…the further away from your stroke, the longer the time band has to be.” [Participant 1, Male, stroke >1–5 years ago, Item 31]

“…if it had been asked you know, six months after my stroke, it might have been slightly different, but at this point in time, I don’t think there’s any…not at all, I would say.” [Participant 3, Female, stroke >1–5 years ago, Item 31]

“For someone who’s recently had a stroke, yes. For me now, six years after, no, not four, I wouldn’t talk in terms of four weeks, again it…it’d be months.” [Participant 5, Female, stroke >5 years ago, Item 4]

“No, I think you’d probably need to go back to, you know, when you actually had the stroke, because that was more frightening and more relevant then…” [Participant 12, Male, stroke >5 years ago, Item 1]

“I suppose…yeah, probably. Okay. Unless somebody’s had a, a recent stroke, it might be more relevant to them.” [Participant 9, Female, stroke >1–5 years ago, Item 16]

“I would’ve said, following the stroke…I’ve not deteriorated significantly since my stroke, the big issue was stroke and immediately afterwards. And that’s the timeframe that this is gonna be relevant to for getting rehabilitation…” [Participant 7, Male, time since stroke unknown, Item 33]

After initially extending recall periods it was decided to remove recall periods from all items and instead use the following instruction:

When answering these questions, think about the time since your stroke. If your stroke was many months ago then think about the past few months.

Clarity

Changes were made to several items to improve clarity, but no items were removed. Confusion was noted about whether the measure focused only on stroke. Several participants noted that while some items did not apply to their stroke, they did apply to their other health conditions. It was decided that respondents should consider all health conditions when answering and an additional instruction was added stating this. The position of one item was altered to make the measure easier to follow (Item 6).

Changes were also made to the wording of three items which were not inclusive of other health conditions (Items: 3, 4, 16) and where there was confusion about item meaning (Items: 2, 12, 13, 14, 24, 28, 31). Despite including a brief explanation in the measure, some participants expressed confusion around the meaning of ‘self-management’ in two items (Items: 31, 34). This term was replaced with “looking after your health” (Item 31) and “attempting to manage your health conditions” (Item 34). One participant felt that two items were very similar (Items: 14 and 15) as both referred to healthcare provider’s recommendations for physical activity - the wording of one was altered (Item 14). Further changes were made to items to improve clarity (Items: 5, 12, 24, 33) in response to queries raised by participants and to ensure consistency of wording (Items: 32, 17).

Discussion

Creating a measure of treatment burden specific to stroke survivors is important because evidence suggests that this population faces significant burden of treatment due to multi-faceted, chronic treatment regimens [Citation33,Citation34]. We have created the first version of a measure of treatment burden that contains items relevant to stroke survivors (PETS-stroke). Including stroke survivors in scrutinizing the items for relevance and clarity, the scale should have pragmatic validity and be feasible for further rigorous evaluation and testing in the wider population of stroke survivors. The PRM developed for use in this project is a significantly shorter, 34-item version of the 60-item PETS version 2.0 measure. Our findings suggest that the measure is best suited to measuring treatment burden in the first year after stroke, capturing the acute rehabilitative phase of recovery that is not sufficiently covered by existing PRMs. People who have had a stroke report feeling abandoned after discharge and at the end of acute rehabilitation – there is a need in that first year to support people to build their confidence, explore what self-management works for them, and to help them become independent and be able to adapt to what life looks like after a stroke [Citation35]. Based on our findings, our subsequent validation of PETS-stroke will therefore focus on the first year after stroke. However, it is important further work is done to explore the best way to measure treatment burden after this time. It may be that measures developed for use in people with multiple long-term conditions are suitable for those beyond the first year of their stroke, but research is needed to explore this.

Strengths and limitations

Our adapted stroke-specific treatment burden measure leverages the foundation of a previously developed and rigorously tested comprehensive general measure of treatment burden. While some items required modification to optimize relevance to stroke survivors, others remained relevant and were therefore maintained verbatim from the original measure. When changes were necessary, they occurred after discussion amongst members of a research team with considerable treatment burden expertise, using a conceptual model derived from rigorous qualitative research that examined the stroke survivor perspective.

A further strength is the use of appropriate recommendations - COSMIN - to inform the methodological approach [Citation24,Citation26,Citation36]. The inclusion of stroke survivors with different experiences (e.g. variety of ages, length of time since stroke) and impairments (e.g. aphasia, extent of impairments) was an additional strength, allowing us to benefit from a variety of viewpoints on the importance and relevance of items in the measure.

We encountered some methodological difficulties when conducting the cognitive interviews. Some participants found it difficult to distinguish between the themes of importance and relevance. There was also difficulty associated with asking participants to evaluate the content of the question itself rather than answering it which was the more instinctual response. We sought to resolve this by reiterating explanations of ‘importance’ and ‘relevance’ throughout the interviews and revisiting our interview questions as needed to refocus participants on examination of content of items. This was generally effective but time consuming.

The second and third round of interviews in this study occurred in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, participants often raised issues they had faced as a consequence of the pandemic and local lockdown restrictions. Responses, particularly related to relevance and timeframe, were occasionally influenced by such recent experiences. Therefore, it was sometimes necessary to elicit answers that encompassed both their pre- and post-pandemic experiences.

There is no consensus on sample size for content validations studies. A wide variation in sample size is apparent in previous cognitive interview studies, for example smaller studies including eight participants [Citation37] and larger studies including 52 participants [Citation38]. This study’s small sample size could be viewed as a limitation. However, recruitment was terminated when no further changes to the PRM were required. It should also be noted that participants’ demographic and health information was self-reported. We did not specifically ask participants to describe sequela and did not formally record their functional level. In addition, all participants in this study were white, limiting the generalisability of the findings to people of other races and ethnicities. Future tests of the measure will aim to recruit a broad representation of people from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

Future research

This work is part of a larger programme of work aimed at measuring and lessening treatment burden after a stroke. Construct validity and reliability of PETS-stroke will be tested in a large postal survey. As there is no ‘gold standard’ measurement of treatment burden in this population, PRMs of related concepts will be utilised for examination of construct validity, for example illness burden. Initially we will focus on the first year at home following stroke as our findings here suggest this is when PETS-stroke items are most relevant. Our previous research has also identified that as a particularly difficult time for stroke survivors [Citation6,Citation7]. Acknowledging that life after stroke is a growing research priority, however, it would be important for further research to also examine how best to measure and lessen treatment burden in the longer-term after a stroke.

When fully developed and psychometric properties have been tested, PETS-stroke has the potential to be utilised to identify those at high risk of treatment burden and examine associations between treatment burden and health-related outcomes. It also has potential to be appropriate for use as an outcome measure (or baseline case-mix adjuster) in clinical trials of stroke treatments and complex interventions. It will allow inclusion of treatment burden as a primary outcome in trials of interventions aimed at reducing it and also as an important secondary outcome in any trial of changes to usual practice in stroke care. We envisage PETS-stroke becoming part of a ‘core outcomes set’ for use in stroke trials. However, it is important to recognize that the changes necessitated by adaptation to the stroke population will preclude any direct comparisons with scores of the original PETS (general) measure.

Conclusion

The work reported here has led to the development of a measure with content that is relevant and meaningful to stroke survivors while also being easy to understand and complete. Following further validation, this patient-reported measure of treatment burden will allow for identification of high-risk individuals, aid the testing of stroke treatments, and facilitate the improvement of life after stroke.

Author contributions

This study was conceptualised by KG, FM, DE, TQ, and LK. Data collection was completed by AS and KW. KW drafted the majority of the manuscript utilising findings from the first round of interviews written by AS. KG contributed to writing sections of the introduction, methods, results and discussion. All authors commented and critically revised drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (53.2 KB)Disclosure statement

Prof Mair and Dr Gallacher are members of an international work group that promotes a move to “minimally disruptive medicine”. This work is unfunded. Prof Eton was responsible for the development and validation of the original PETS versions 1 and 2.

Data availability statement

Access to anonymised data can be discussed by contacting the authors. The Patient Experience with Treatment and Self-management (PETS), including all versions, is protected by copyright to the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, © 2016, 2020, all rights reserved. The PETS (general measure) and its scoring are available by contacting Dr Kathleen Yost ([email protected]).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Stevens E, Emmett E, Wang Y, et al. The burden of stroke in Europe the challenge for policy makers. In: Korner J, editor. London, UK: King’s College London; 2017.

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2021 update. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254–e743. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950.

- Clery A, Bhalla A, Rudd AG, et al. Trends in prevalence of acute stroke impairments: a population-based cohort study using the South London stroke register. PLoS Med. 2020;17(10):e1003366. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003366.

- McKevitt C, Fudge N, Redfern J, et al. Self-reported long-term needs after stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1398–1403. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598839.

- Leys D, Hénon H, Mackowiak-Cordoliani M-A, et al. Poststroke dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005; 4(11):752–759. 2005/11/01/doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70221-0.

- Gallacher K, Morrison D, Jani B, et al. Uncovering treatment burden as a key concept for stroke care: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2013;10(6):e1001473. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001473.

- Gallacher KI, May CR, Langhorne P, et al. A conceptual model of treatment burden and patient capacity in stroke. BMC Fam Pract. 2018; 2018/01/0919(1):9. doi:10.1186/s12875-017-0691-4.

- Eton DT, Ramalho de Oliveira D, Egginton JS, et al. Building a measurement framework of burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2012;3:39–49. doi:10.2147/PROM.S34681.

- Gallacher KI, Quinn T, Kidd L, et al. Systematic review of patient-reported measures of treatment burden in stroke. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e029258. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029258.

- Eton DT, Lee MK, St Sauver JL, et al. Known-groups validity and responsiveness to change of the patient experience with treatment and self-management (PETS vs. 2.0): a patient-reported measure of treatment burden. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(11):3143–3154. doi:10.1007/s11136-020-02546-x.

- Boyd CM, Wolff JL, Giovannetti E, et al. Healthcare task difficulty among older adults with multimorbidity. Med Care. 2014;52(Suppl 3):S118–S125. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a977da.

- Schreiner N, DiGennaro S, Harwell C, et al. Treatment burden as a predictor of self-management adherence within the primary care population. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;54:151301. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151301.

- Rigby H, Gubitz G, Phillips S. A systematic review of caregiver burden following stroke. Int J Stroke. 2009;4(4):285–292. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00289.x.

- May CR, Eton DT, Boehmer K, et al. Rethinking the patient: using burden of treatment theory to understand the changing dynamics of illness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):281. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-281.

- Spencer-Bonilla G, Quiñones AR, Montori VM. Assessing the burden of treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(10):1141–1145. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4117-8.

- Eton DT, Yost KJ, Lai J-S, et al. Development and validation of the patient experience with treatment and self-management (PETS): a patient-reported measure of treatment burden. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(2):489–503. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1397-0.

- Rogers EA, Yost KJ, Rosedahl JK, et al. Validating the patient experience with treatment and Self-Management (PETS), a patient-reported measure of treatment burden, in people with diabetes. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2017;8:143–156. doi:10.2147/PROM.S140851.

- Lee MK, St Sauver JL, Anderson RT, et al. Confirmatory factor analyses and differential item functioning of the patient experience with treatment and Self-Management (PETS vs. 2.0): a measure of treatment burden. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2020;11:249–263. doi:10.2147/PROM.S282728.

- Tran V-T, Montori VM, Eton DT, et al. Development and description of measurement properties of an instrument to assess treatment burden among patients with multiple chronic conditions. BMC Med. 2012;10(1):68. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-68.

- Tran V-T, Harrington M, Montori VM, et al. Adaptation and validation of the treatment burden questionnaire (TBQ) in english using an internet platform. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):109. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-12-109.

- Ishii H, Shin H, Tosaki T, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a questionnaire measuring treatment burden on patients with type 2 diabetes: diabetic treatment burden questionnaire (DTBQ). Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(3):1001–1019. doi:10.1007/s13300-018-0414-4.

- Duncan P, Murphy M, Man M-S, et al. Development and validation of the multimorbidity treatment burden questionnaire (MTBQ). BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019413. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019413.

- van Straten A, de Haan RJ, Limburg M, et al. A Stroke-Adapted 30-Item version of the sickness impact profile to assess quality of life (SA-SIP30). Stroke. 1997;28(11):2155–2161. doi:10.1161/01.str.28.11.2155.

- Reeve BB, Wyrwich KW, Wu AW, et al. ISOQOL recommends minimum standards for patient-reported outcome measures used in patient-centered outcomes and comparative effectiveness research. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(8):1889–1905. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0344-y.

- Gallacher K, Taylor-Rowan M, Eaton D, et al. Protocol for the development and validation of a patient reported measure (PRM) of treatment burden in stroke [version 1; peer review: awaiting peer review]. healthopenres. 2023;5:17. doi:10.12688/healthopenres.13334.1.

- Gagnier JJ, Lai J, Mokkink LB, et al. COSMIN reporting guideline for studies on measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(8):2197–2218. doi:10.1007/s11136-021-02822-4.

- Willis GB, Artino AR.Jr. What do our respondents think we’re asking? Using cognitive interviewing to improve medical education surveys. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):353–356. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-13-00154.1.

- Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed Patient-Reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 2—assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011; 2011/12/01/14(8):978–988. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.013.

- Wright J, Moghaddam N, Dawson DL. Cognitive interviewing in patient-reported outcome measures: a systematic review of methodological processes. Qual Psychol. 2021;8(1):2–29. doi:10.1037/qup0000145.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):117. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-117.

- Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage Publications; 2013.

- Scottish Government. Scottish index of multiple deprivation: crown Copyright. 2020. https://www.gov.scot/collections/scottish-index-of-multiple-deprivation-2020/

- May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally disruptive medicine. BMJ. 2009;339:b2803. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2803.

- Mair FS, May CR. Thinking about the burden of treatment. BMJ. 2014;349:g6680. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6680.

- Kidd L, Lawrence M, Booth J, et al. Development and evaluation of a nurse-led, tailored stroke self-management intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):359. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-1021-y.

- Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1159–1170. doi:10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0.

- Rivara MB, Edwards T, Patrick D, et al. Development and content validity of a Patient-Reported experience measure for home dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(4):588–598. doi:10.2215/CJN.15570920.

- Flythe JE, Dorough A, Narendra JH, et al. Development and content validity of a hemodialysis symptom patient-reported outcome measure. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(1):253–265. Jandoi:10.1007/s11136-018-2000-7.