Abstract

Purpose

Physiotherapists working in hospitals have a key role in decisions about when a person with stroke is safe to walk independently. The aim of this study was to explore the factors influencing decision-making of physiotherapists in this situation.

Methods

A qualitative design with semi-structured interviews and reflexive thematic analysis was used. Fifteen physiotherapists with recent experience working in inpatient stroke rehabilitation participated.

Results

Multiple factors influence decision-making about walking independence after stroke in hospitals. Four themes were identified: (1) Assessment of walking safety involves observation of walking function and consideration of complex individual factors; (2) Perspectives on risk vary, and influence whether a person is considered safe to walk; (3) Institutional culture involves background pressures that may influence decision-making; and (4) Physiotherapists adopt a structured, individualised mobility progression to manage risk. Physiotherapists consistently use observation of walking and understanding of attention and perception in this decision-making. There can sometimes be a conflict between goals of independence and of risk avoidance, and decisions are made by personal judgements.

Conclusions

Decision-making about independent walking for people in a hospital after a stroke is complex. Improved guidance about clinical assessment of capacity and determining acceptable risk may enable physiotherapists to engage more in shared decision-making.

Regaining independence in walking after a stroke comes with the potential risk of falls.

Assessment of walking safety should be specific to the complexity of the situation and consider perception and cognition.

Benefits of activity and autonomy, and the risk of falls need to be considered in decisions about walking independence.

Patients with the capacity to understand consequences and accept risk can be active participants in determining what is sufficiently safe.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Walking impairment has been reported in up to two-thirds of people with stroke [Citation1,Citation2], and recovery of independence, speed, and balance are common rehabilitation goals [Citation1]. Potential for recovery is variable with achievement of independent walking reported at between 57% and 64% of those who cannot initially walk [Citation2–4], or 85% overall [Citation5,Citation6]. It is generally agreed that promoting activity is beneficial for recovery after stroke [Citation7,Citation8], however, the optimal dose is unknown. Commonly people in inpatient rehabilitation settings have less active time than is recommended [Citation9–12].

People with stroke carry a high risk of falls during the inpatient period (up to 47%) and a higher risk than age-matched controls in the longer term [Citation13]. Falls contribute to the carer burden and have a negative impact on stroke recovery due to potential injury and fear of falling which may further limit mobility [Citation13,Citation14]. It is clear that falls are undesirable in hospitals [Citation13–15], however, staff concerns about falling may lead to falls reduction strategies that reduce physical activity [Citation16,Citation17]. Despite the potential risk of injury from falls, walking independence is important for discharge success, independence [Citation18,Citation19], and future health status [Citation20,Citation21]. The threshold for what is considered sufficiently safe to walk is unknown, however, there is a possibility that some level of risk in rehabilitation may be acceptable if it allows for more autonomy and activity, and longer-term community participation [Citation22,Citation23].

Only one study has been found investigating the clinical reasoning of physiotherapists in determining independent walking in a hospital after a stroke. Takahashi et al. [Citation24] found that the key features of assessment related to the observation of walking and balance as well as higher brain functions and opinions of other staff. This study did not explore other potential factors including structural influences, and provider, patient or family factors that are known to influence decision-making have been identified in a recent scoping review [Citation25,Citation26]. Structural influences in hospital settings can include time constraints, pressure for discharge and culture around accountability or blame [Citation25,Citation26]. Provider factors may include professional competence, background and experience, cultural competence, and flexibility in diverse circumstances [Citation26]. Ultimately the patient should be influential in decisions about their care, however, issues of decision-making capacity may give that responsibility to families [Citation25,Citation26]. When decisions are made that involve tension between the potential benefits of activity and the risk of falls, two different ethical principles of health care can conflict – autonomy (promoting independence) and beneficence (acting in the best interests of the patient) [Citation26].

Where individual priorities and judgement are a factor, a person-centred approach and shared decision-making are often recommended [Citation27–31]. Shared decision-making involves consideration of patient values and preferences as well as medical knowledge in decision-making [Citation27]. Health professionals may also share responsibility for a difficult decision or recommendation within a multidisciplinary team [Citation26]. Despite these principles being generally accepted as appropriate, patients at times report little to no involvement in decisions about their care [Citation30]. Many people hospitalised after a stroke experience dependency and lack of control, which can be exacerbated by the hospital environment [Citation32]. The loss of autonomy and independence after stroke continues to be restricted at five-year follow-up [Citation19], however, it is unclear if habits developed in the hospital have any impact on this.

Anecdotally, physiotherapists are key health professionals involved in decision-making processes regarding independent walking in hospital after a stroke. With little known about how decisions about walking safety are made, the objective of this study was to explore physiotherapists’ perspectives on what influences decisions about the transition to independent walking after stroke.

Materials and methods

Design

Semi-structured interviews were used, with reporting in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research [Citation33]. This study is best described as having a critical realist ontology and contextualist epistemology which recognises the ambiguity and subjectivity in understanding truth from experience. As health decision-making is sometimes made on vague representations of the overall meaning of information rather than precise details [Citation34], qualitative methodology is appropriate to understand perspectives on what influences these decisions. Ethical approval was obtained from Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2021-0764) prior to the study commencing.

Participants

Physiotherapists registered to work in Australia were invited to participate if they had been involved in decision-making around walking independence for a person with stroke in an inpatient setting at least once in the past year. Potential participants were approached with a flyer attached to a monthly neurological physiotherapy mailing list managed by a local senior physiotherapist. Purposive sampling and snowballing were used to recruit participants with varied experience, across acute and rehabilitation inpatient settings and including tertiary, secondary, and regional hospitals.

Interviewer characteristics

Interviews were conducted by one of the authors (LB), a female physiotherapist studying a Doctor of Philosophy degree. She has more than 20 years of experience in neurological physiotherapy across inpatient, outpatient and community areas and is now working in education as well as clinically. This researcher was known in varied professional capacities to several, but not all, participants and is considered to have insider status with an understanding of the health system from personal experience.

Data collection

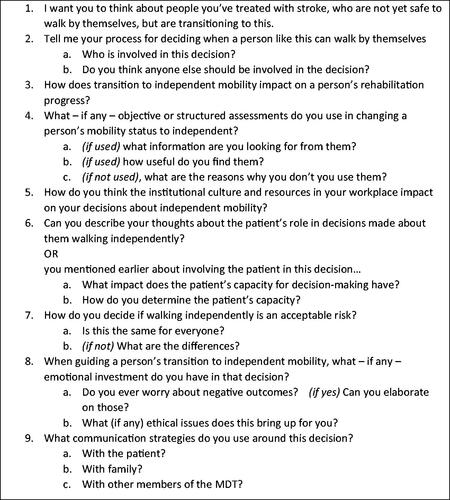

A semi-structured interview guide () was developed with a focus on topics that were identified as relevant in a systematic scoping review of the literature [Citation26]. Pilot testing of the interview guide with two physiotherapists prior to the recruitment of participants found it fit for purpose. Participants were fully informed of the reasons for the research. Prior to the interview, participants gave informed consent and provided basic demographic information including gender, age, years of experience in inpatient neurology, seniority of position title, and post-graduate qualifications. Interviews lasted from 25 to 40 min and were conducted and recorded online in private settings. Field notes were taken during the interview to assist the interviewer asking relevant follow-up questions, and to aid data analysis. Subsequently, recordings were transcribed verbatim by the interviewer and reviewed for accuracy by a second member of the research team (KB). Transcripts were identified only by an ID code prior to data analysis.

Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis was conducted in accordance with the six stages outlined by Braun and Clarke [Citation35] with the purpose of developing themes or meaningful patterns from the data. The primary researcher (LB) made familiarisation notes during transcription, and both semantic and latent codes were collated using NVivo (R1.0). The coding tree evolved over several iterations of data review, initially coding data generally and developing nodes where collections of codes were present. Initial themes were developed by LB and reviewed by a second researcher (KB). Initial themes were further developed and defined by LB and then reviewed by the full research team. After further review of raw data, codes, and initial themes, the final themes were developed to best represent the raw data. The final report was produced by the research team.

The possibility of data saturation is a debated concept in qualitative research [Citation36,Citation37], with the primary approach for this study to explore the influences on participants’ decision-making in depth. It was noted that while additional depth was developed after 8 transcripts were coded, there were no new nodes identified. This situation can be interpreted as approaching saturation [Citation38,Citation39]. Member checking was not used as the study intended to capture the conscious influences on decision-making rather than thoughts that evolved from the discussions.

Strategies to ensure trustworthiness

The main strategies to ensure the trustworthiness of the findings were in-depth interviews, reflexivity of the data analysis, and review of transcripts, coding, and themes. To ensure the depth of the interviews, initially, a scoping review of the literature was conducted to develop a sufficient and relevant breadth of interview topics, and the semi-structured interview guide was pilot tested and developed in conjunction with experienced neurological physiotherapists. As this qualitative approach focusses on the depth of analysis and reflexivity [Citation35], this process also involved the researcher considering the impact of insider status and checking personal bias during the interviews and data analysis. To further ensure faithfulness of the representation of the data, a second researcher (KB) reviewed the recordings and transcriptions for accuracy, and fairness in coding and theme development. While sample size is often not considered to be the most important factor in qualitative research, fifteen participants is generally considered sufficient [Citation36,Citation39,Citation40].

Results

Physiotherapists who responded to the flyer came from a variety of different workplaces, and it is interpreted that the initial emailed invitations achieved wide distribution within the city. Two participants from regional areas were recruited purposively for greater coverage. Fifteen participants in total were interviewed once between 1st March 2022 and 14th November 2022. There were no dropouts, everyone who expressed interest progressed to interview, and all fifteen interviews were included in the data analysis. All participants were female and ranged in age from 23 to 50+ years (median = 32; interquartile range = 18) and included diversity in experience from less than one year to greater than 20 years (median = 7; interquartile range = 13) in inpatient neurology. While there are some males working in inpatient neurology areas, none responded to the invitation to participate in this study. The current workforce in this area is predominantly female [Citation41] so this sample is not unrepresentative. Participants reported experience across acute and rehabilitation areas. Characteristics of participants are summarised in , aggregated to maintain confidentiality.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Four themes were identified: (1) Assessment of walking safety involves observation of walking function and consideration of complex individual factors; (2) Perspectives on risk vary, and influence whether a person is considered safe to walk; (3) Institutional culture involves background pressures that may influence decision-making; and (4) Physiotherapists adopt a structured, individualised mobility progression to manage risk.

Theme 1: assessment of walking safety involves observation of walking function and consideration of complex individual factors

When making decisions about walking safety, participants described using an individualised assessment mix involving observation of walking function, assessment of impairments related to motor, sensory, and higher cortical function, and discussion with other staff in complex cases. The different components of function or impairment that were considered important varied between participants, and judgement or “gut feeling” was valued highly in making an overall decision. The use of standardised assessments or outcome measures was widely reported as useful where results supported decisions but was not a driver of decision-making about walking safety.

Observation of walking was considered to be an important part of the assessment of walking safety to determine relevant characteristics about control of walking and how patients negotiated the environment.

Looking at [the] patient walking both within their room [and] around their room environment… also if they’re able to walk longer distances I like to see how they’re walking in a corridor because … [it] gives me a bit of information about how they negotiate obstacles, people, distractions and that sort of thing (senior, 7 years inpatient neurology).

Specific observations of function that were important in making decisions about independence were varied and a complete list of these is included in . Most frequently reported were observations of non-linear and perturbed walking, signs of cognition or attention in functional walking, balance and saving responses, gait speed, and stance control. It was also common for participants to find it difficult to clearly articulate exactly which observations were important as individuals and their circumstances were unique: “I feel like there is so much that I weigh up probably without like having a regimented process” (Junior, 4 years inpatient neurology).

Table 2. Specific features of walking function reported as relevant for a decision on independence.

In addition to observing function, most participants also assessed impairments, with perceptual deficits, lower limb control, sensation, vision, and trunk control all considered relevant to decisions about walking safety: “it would depend a lot on the patient so not only their physical abilities and I think even more so it would depend on their cognitive abilities, problem-solving, and perceptual abilities” (Senior, 11 years inpatient neurology).

All participants reported gathering information from other staff – particularly occupational therapists and nurses. Occupational therapists (OT’s) were considered relevant for their contribution in how the patient performed in functional activities, crowded spaces, dual tasking, and with distractions. Nurses were consulted regularly for their feedback related to the consistency of patient performance over the 24 h period, particularly at night, when tired, and outside of formal assessment.

I will obviously work with the OT’s … if they were wanting to go [and] make a hot drink or … go have a shower I probably have a little chat and just see were they safe in the shower on their own… obviously the nurses as well are really invaluable if one day I might say “this patient is independent” and then if the nurse comes to me the next day and [says] “oh you will never guess what the patient was doing when they were on their feet” (Junior, 1 year inpatient neurology).

Participants described using their judgement or “gut feeling” to make decisions rather than a formula of assessment findings: “are you comfortable standing five metres away from them and watching them walk?” (Junior, 2 years inpatient neurology). Particularly in rehabilitation settings, this evolved through becoming familiar with the patient over time in addition to formal assessment: “over time and some of that is a little bit of a gut [feeling]… you just feel comfortable to start drifting away from them and then you realise they’re probably getting towards being safe” (Senior, 7 years inpatient neurology).

Standardised measures were generally considered to be a helpful part of the overall assessment, with the Berg Balance Scale most frequently acknowledged. Most participants reported awareness of some predictive value in these measures and would use them to support their decision. However, participants’ decisions were generally not based on standardised measures due to time constraints and the limited scope of tests that may measure a specific feature of movement but not specifically walking safety.

Objective measures look at balance and there are so many more factors that affect someone’s safety with mobilising than just balance, like their cognition and attention … so no I don’t use it to help with my decision-making for independence. (Senior, 15 years inpatient neurology).

Theme 2: perspectives on risk vary and influence whether a person is considered safe to walk

Assessing falls risk and making recommendations about walking independence was considered a key responsibility by all participants, however, there were different perspectives on balancing the importance of beneficence and autonomy. In recommending against independence to prevent risk, participants acknowledged that some patients choose to walk without telling anyone. When promoting a person’s autonomy or walking independence, the importance of that individual’s capacity to accept any risk was important, however there was a lack of clear assessment of this in the hospital setting.

Participants’ approaches to decision-making about walking independence were significantly shaped by beliefs about their responsibility to manage risk. All participants reported that assessing the risk of falls and then making recommendations about walking safety was a key part of their practice. However, the degree to which this dominated decision-making varied markedly. While some participants reported that any risk was intolerable in a hospital setting: “I’d err on the side of caution… I think being in a hospital environment you have to, because if there’s a catastrophic fall then that’s not really acceptable” (Senior, 15 years inpatient neurology). Other participants believed that the promotion of autonomy should not be compromised: “Well you know they’re an adult person with the ability to make their own decisions so actually they can do that and that’s their right to take that risk” (Senior, 11 years inpatient neurology). Other participants sat between these two extremes in their approach to balancing risk and autonomy.

Participants reported that patients erroneously believed they were safe to walk independently, and this was a frequent issue. Several participants saw their role as protecting patients from potential harm: “for me it’s an issue because patients will often say ‘I can walk as long as I can hold on to the wall’ and that’s just not good enough” (Senior, 20+ years inpatient neurology). In these situations, however, it was difficult to prevent the person taking those risks and participants would focus on reminding them of the risk and minimising harm: “often they’re doing it [walking] already but it’s just whether … they know the risks associated” (Senior, 4 years inpatient neurology).

Participants generally expressed support for a patient’s right to accept risk against their advice if the person had the capacity to make that decision, however there was a lack of clarity about how this capacity should be assessed. Some participants reported occupational therapy cognitive assessments were helpful, and others believed a lack of capacity was usually obvious. Others reported that capacity could only be determined by formal medical or legal certification, which was occasionally requested for discharge decisions, but not for making decisions about walking independence. In these complex situations, participants took the decision to the multidisciplinary team to share responsibility and gather all perspectives. Despite potential risks, good reasons for patients to want to walk independently were recognised: “they don’t have to wait for nursing staff which is a big frustration for a lot of our patients, so they’ve got a bit more autonomy and control back” (Senior, 7 years inpatient neurology).

All participants were asked their perspective on what was an acceptable level of risk to promote independence. There were a range of responses listed in that related to the severity of potential harms or the practicality of alternatives. Consistently, the complexity and variability of each individual situation was highlighted.

Table 3. Circumstances reported as relevant when deciding if level of risk is acceptable to promote independent walking.

We get to see the patients every day, … so when it comes time to make that decision, it’s not like a single decision, it’s like a cumulative [of] all that … information … that kind of feeds into that decision-making (Senior, 4 years inpatient neurology).

Participants reported that experience had a big impact on decision-making, and that they may have become less conservative about risk over time. This was related to situations where patients were walking independently despite some risk, but there were no negative consequences: “over time being a little bit less cautious and haven’t had too many negative outcomes so have been more confident to make those decisions” (Senior, 15 years inpatient neurology). Participants reported that junior staff benefited from the presence of supportive senior staff who could help with decision-making.

Theme 3: institutional culture involves background pressures that may influence decision-making

Participants reported that their recommendations about independent walking were based on the professional assessment described in theme 1 without undue pressure from their workplace. However, two background institutional pressures became evident throughout the interviews. Hospital environments were noted as risk-averse with prominent falls prevention policies that factored against independent walking, while pressure to increase bed availability by discharging patients could accelerate independent walking.

The risk-averse nature of hospital environments was noted by several participants who reported ward education and general procedures based around falls prevention making risk avoidance a prominent goal of the institution:

Stats for falls were projected everywhere and doing everything you can to try and minimise falls and… I guess if I’ve done lots of post fall reviews recently on the ward… then it would make me less likely to want to take the risk (Junior, 1 year inpatient neurology).

Awareness of general pressure to discharge patients from both within the hospital and from the patients was frequently reported, although participants did not feel personally under pressure to document a patient as safe to walk against their clinical judgement: “probably subconsciously you are certainly under pressure to get people discharged” (Junior, 2 years inpatient neurology). Some participants reported that imminent discharge would prompt them to change walking status to independent even if walking safety was unclear, as this would lead to more walking practice prior to discharge.

I think it’s tricky when you leave it right to the last minute and make them independent and then send them home to start managing by themselves [as] they haven’t… discovered what they can do, what their limitations are… when they can… take those risks and when they need to be a bit more cautious (Senior, 3 years inpatient neurology).

In some situations, the potential for discharge could delay independent walking with some participants reporting concerns that a doctor might see a patient walking independently on the ward and assume they were safe for discharge. Participants reported the need to make sure a person could cope with the complex walking tasks required in their home setting prior to discharge: “for me it’s about trying to replicate what someone might have to cope with in the home environment or in the community as the case may be” (Senior, 20+ years inpatient neurology).

Factors complicating the impact of discharge on decisions about walking safety were deciding on an appropriate walking aid and factoring in the quality of the gait pattern. While walking safety was clearly the main factor in decisions about independence, there was reluctance amongst some participants to encourage independent practice when they believed improvements in walking quality were still likely. This was acknowledged as potentially delaying discharge but was mentioned to have long-term benefit by a small number of participants: “If we’re not wanting them to get those compensatory patterns I would steer away from making them independent on the ward… while building up their endurance” (Senior, 20+ years inpatient neurology).

Theme 4: physiotherapists adopt a structured, individualised mobility progression to manage risk

Participants described strategies to promote mobility and manage risk, involving graduated stages of independence and communication with a patient, family and staff to inform and manage expectations. This allowed patients to have some independence and opportunity to practice, while minimising risk.

Physiotherapists gave recommendations about specific environments in which they encouraged people to walk independently in order to achieve practice while minimising risk. People with limited ability to manage distance or hazards could walk in a specific controlled environment (usually their room, but parallel bars was another example). Walking on the ward with predictable hazards was a second stage, with the most difficult progression being walking outdoors or off the ward, with increased distance and unpredictable hazards. Other variations in independence included independent transfer and wheelchair mobility and independence from staff with family support.

The importance of communication with patients and family was highlighted, particularly where there was the presence of risk. Explaining to patients and family why the decision about independent walking was made was seen as important to promote walking where patients were reluctant, or to avoid risk in patients who were considered unsafe: “I would try and make sure that they [patient and family] have an understanding of the reasoning behind a decision as well as getting them to be involved in the decision a little bit” (Senior, 15 year inpatient neurology). Repetition of this was particularly important when cognitive or higher cortical dysfunction affected a person’s ability to make decisions or remember instructions: “depending on memory and things like that and how their cognition is, we write it down for them as well. We’ve written prompts in the past on people’s tray tables to say remember to call for your nurse” (Senior, 2 years inpatient neurology). The importance of clearly documenting the process and communications was also noted.

Discussion

This study has identified that due to each unique situation, there are many and varied considerations and influences on decision-making in relation to walking independence in hospital after stroke. Physiotherapists in this study consistently reported prioritising observation of walking and balance in functions and environments that are relevant to the individual, in addition to considering cognition, perception or higher cortical function and information gathering from other staff. There is no clear definition of what constitutes “safe to walk independently”, so decisions vary with the physiotherapist’s perceptions of the potential harms from falling and the benefits of promoting independence. Given the number of competing factors relevant to the decision, it appears that experience and “gut feeling” play a role, as well as the potentially institutional culture of the hospital or ward. In general, physiotherapists appear to be very structured in progressing independence and communicating with patients and families in order to manage the inherent risk and expectations.

These findings strongly support the previous study in this area, with the observation of complex components of walking and balance a key feature of assessment, with less value given to standardised assessments [Citation24]. Both studies also identified the importance of higher cortical functions such as cognition, attention, insight and safety behaviours, and the value of discussions with other staff [Citation24]. There is a need to explore innovative approaches to address the barriers to objective assessment of walking safety. To be most effective in clinical scenarios, a tool would need address issues of mobility, balance, and higher cortical functions as well as being time efficient and usable on a daily basis to keep pace with changes in functional mobility.

In addition to the physiotherapy assessment of independent walking, a range of other factors that potentially influence decisions were found in this study, matching previous work in the area of health professional decision-making [Citation26]. Personality traits are believed to be a factor in decision-making generally [Citation42], which is reflected in this study in relation to perspectives on risk and autonomy. While some participants prioritise autonomy (err towards letting the patient decide), others prioritise benevolence (err towards preventing harm). This difference in the personal beliefs of the participant led to differences in the outcomes of decisions, and how they were communicated.

Perceptions of risk also vary between individuals and can be felt as instinct, or analysed logically [Citation43]. Gender is a factor influencing risk perception, with females tending to perceive risks as higher [Citation44,Citation45]. All of the participants in this study were female which may have influenced findings, however, it is likely that with a female-dominated physiotherapy workforce [Citation41], this is representative of clinical practice. In addition to the health professional’s individual beliefs, health care organisations are also broadly acknowledged as affecting knowledge translation into clinical practice [Citation46], and in this study, organisational risk aversion and discharge pressure were both identified as potential factors.

Clinical decision-making in physiotherapy is not well understood, with varied theories about how decisions are made and no consensus about how it should be taught [Citation34,Citation47–49]. Two types of reasoning are used in different situations – deductive reasoning involving hypothesis generation based on information gathered, and inductive reasoning using pattern recognition based on experience [Citation50]. Decisions in health care are often made with incomplete or potentially conflicting information and uncertain outcomes, and decision-makers often simplify this information into big-picture representations to create meaningfulness [Citation34,Citation51]. From this study, participants identified many factors (e.g., discharge pressure or family support) that could be considered relevant in a specific situation. Participants highlighted the importance of experience in interpreting these factors in the context of the situation and making a judgement call, indicating the use of inductive reasoning. This is a challenge for health professionals without access to that experience such as those who have recently graduated or are new to the area without senior support. Given the importance of clinical experience to support this type of decision-making, there may be value in ensuring support mechanisms that provide support to junior staff in these positions.

The value in shared decision-making where the health professional’s knowledge and the patient’s values are brought together to make a person-centred decision has previously been identified [Citation25,Citation27,Citation28,Citation52]. In this study, all participants described the importance of communication with patients. Conversely, few described a genuine shared decision-making process, with concerns about safety often a key factor when the participant believed this was their decision to make. It is unclear from this study how much a culture of risk aversity is implicated in this, but sentiments around health professionals’ reluctance to allow patient involvement in risk-based decisions related to hospital discharge have been previously reported [Citation53].

Perspectives around risk were potentially further complicated as participants reported that patients with the capacity to accept risk should be able to make that decision themselves. However, participants also reported limited practical ability to determine capacity formally. Participants believed they were able to determine capacity through clinical impressions, however, a study of health professionals’ ability to recognise capacity using clinical judgement found a limited correlation with results of formal neuropsychological assessment [Citation54]. Participants also frequently reported cognition as a determinant of capacity, whereas the ability to understand consequences is generally reported to be a more critical indicator of capacity [Citation55,Citation56].

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first qualitative study to explore psychosocial influences on decision-making by physiotherapists in hospitals about walking independence and as such makes a worthwhile contribution to knowledge in this area. The impact of the researcher perspective in a qualitative study is difficult to quantify but is inevitably present. In this study, the researcher was motivated by the need for data about current practice to aid undergraduate physiotherapy education. This study has been completed in a relatively isolated city, and despite the broad representation from acute and rehabilitation areas of tertiary, secondary and regional hospitals, the findings may not necessarily translate to other areas. There were no males in the sample, which may reflect a gender disparity in clinical practice and may not capture some of the diversity in risk perspectives of physiotherapists.

Conclusion

A wide range of factors have been identified as potentially influencing decision-making about walking independence after a stroke in hospitals. Risk management and falls prevention are critical for physiotherapists to consider in making these decisions, however they should reflect on their own predisposition in relation to risk and the patient’s values and beliefs in addition to considering the physical assessment. Different values exist about whether safety or autonomy are more important, and these values potentially lead to different outcomes. There appear to be no guidelines for physiotherapists about how to maintain a duty of care or determine capacity in this clinical context. Further work is required to develop a framework or guideline that could be used to aid decision-making in clinical practice.

Funding

LB was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship that provides fees remission. EB’s time was supported by a NHMRC Investigator Grant (APP1174739). There is no direct funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Moore SA, Boyne P, Fulk G, et al. Walk the talk: current evidence for walking recovery after stroke, future pathways and a mission for research and clinical practice. Stroke. 2022;53(11):3494–3505. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.038956.

- Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, et al. Recovery of walking function in stroke patients: the copenhagen stroke study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(1):27–32. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80038-7.

- Friedman PJ. Gait recovery after hemiplegic stroke. Int Disabil Stud. 1990;12(3):119–122. doi:10.3109/03790799009166265.

- Jang SH. The recovery of walking in stroke patients: a review. Int J Rehabil Res. 2010;33(4):285–289. doi:10.1097/MRR.0b013e32833f0500.

- Skilbeck CE, Wade DT, Hewer RL, et al. Recovery after stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983;46(1):5–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.46.1.5.

- Bernhardt J, Langhorne P, Lindley R, et al. Efficacy and safety of a very early mobilisation within 24h of stroke onset (AVERT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:46–55.

- Lohse KR, Lang CE, Boyd LA. Is more better? Using metadata to explore dose-response relationships in stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2053–2058. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004695.

- Schneider EJ, Lannin NA, Ada L, et al. Increasing the amount of usual rehabilitation improves activity after stroke: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2016;62(4):182–187. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2016.08.006.

- Astrand A, Saxin C, Sjoholm A, et al. Poststroke physical activity levels no higher in rehabilitation than in the acute hospital. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(4):938–945. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.12.046.

- West T, Bernhardt J. Physical activity patterns of acute stroke patients managed in a rehabilitation focused stroke unit. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:438679. doi:10.1155/2013/438679.

- Bernhardt J, Dewey H, Thrift A, et al. Inactive and alone: physical activity within the first 14 days of acute stroke unit care. Stroke. 2004;35(4):1005–1009. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000120727.40792.40.

- Selenitsch NA, Gill SD. Stroke survivor activity during subacute inpatient rehabilitation: how active are patients? Int J Rehabil Res. 2019;42(1):82–84. doi:10.1097/MRR.0000000000000326.

- Batchelor FA, Mackintosh SF, Said CM, et al. Falls after stroke. Int J Stroke. 2012;7(6):482–490. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00796.x.

- Teasell R, McRae M, Foley N, et al. The incidence and consequences of falls in stroke patients during inpatient rehabilitation: factors associated with high risk. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(3):329–333. doi:10.1053/apmr.2002.29623.

- Tan KM, Tan MP. Stroke and falls-clash of the two titans in geriatrics. Geriatrics. 2016;1(4):31. doi:10.3390/geriatrics1040031.

- Growdon ME, Shorr RI, Inouye SK. The tension between promoting mobility and preventing falls in the hospital. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):759–760. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0840.

- Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Ganz DA, et al. Inpatient fall prevention programs as a patient safety strategy a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 Pt 2):390–396. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00005.

- Proot IM, ter Meulen RH, Abu-Saad HH, et al. Supporting stroke patients’ autonomy during rehabilitation. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(2):229–241. doi:10.1177/0969733007073705.

- Palstam A, Sjodin A, Sunnerhagen KS. Participation and autonomy five years after stroke: a longitudinal observational study. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219513. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219513.

- Simpson DB, Breslin M, Cumming T, et al. Go home, sit less: the impact of home versus hospital rehabilitation environment on activity levels of stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(11):2216.e1–2221.e1. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2018.04.012.

- Simpson DB, Jose K, English C, et al. Factors influencing sedentary time and physical activity early after stroke: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(14):3501–3509. doi:10.1080/09638288.2020.1867656.

- Andreoli A, Bianchi A, Campbell A, et al. In defence of falling: the onomastics and ethics of “therapeutic” falls in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2022. doi:10.1080/09638288.2022.2135777.

- Hanger HC, Wills KL, Wilkinson T. Classification of falls in stroke rehabilitation–not all falls are the same. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(2):183–195. doi:10.1177/0269215513496801.

- Takahashi J, Takami A, Wakayama S. Clinical reasoning of physical therapists regarding in-hospital walking independence of patients with hemiplegia. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26(5):771–775. doi:10.1589/jpts.26.771.

- Dy SM, Purnell TS. Key concepts relevant to quality of complex and shared decision-making in health care: a literature review. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(4):582–587. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.015.

- Bainbridge L, Fary RE, Briffa K, et al. Health care professionals’ decision making related to mobility and safety for people in the hospital: a scoping review. Phys Ther. 2023;103(5):pzad024.

- Armstrong MJ. Shared decision-making in stroke: an evolving approach to improved patient care. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2017;2(2):84–87. doi:10.1136/svn-2017-000081.

- Visvanathan A, Dennis M, Mead G, et al. Shared decision making after severe stroke-How can we improve patient and family involvement in treatment decisions? Int J Stroke. 2017;12(9):920–922. doi:10.1177/1747493017730746.

- Johnson J, Smith G, Wilkinson A. Factors that influence the decision-making of an interdisciplinary rehabilitation team when choosing a discharge destination for stroke survivors. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2015;37(2):26–32.

- Holzmueller CG, Wu AW, Pronovost PJ. A framework for encouraging patient engagement in medical decision making. J Patient Saf. 2012;8(4):161–164. doi:10.1097/PTS.0b013e318267c56e.

- Santana MJ, Manalili K, Jolley RJ, et al. How to practice person-centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2018;21(2):429–440. doi:10.1111/hex.12640.

- Luker J, Lynch E, Bernhardsson S, et al. Stroke survivors’ experiences of physical rehabilitation: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(9):1698–1708 e10. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.03.017.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Reyna VF. A theory of medical decision making and health: fuzzy trace theory. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(6):850–865. doi:10.1177/0272989X08327066.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2022.

- Lowe A, Norris AC, Farris AJ, et al. Quantifying thematic saturation in qualitative data analysis. Field Methods. 2018;30(3):191–207. doi:10.1177/1525822X17749386.

- Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13(2):201–216. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846.

- Fusch P, Ness L. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. TQR. 2015;20(9):1408–1416. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2281.

- Hennink M, Kaiser BN. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: a systematic review of empirical tests. Soc Sci Med. 2022;292:114523. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523.

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903.

- Pretorius A, Karunaratne N, Fehring S. Australian physiotherapy workforce at a glance: a narrative review. Aust Health Rev. 2016;40(4):438–442. doi:10.1071/AH15114.

- Flynn KE, Smith MA. Personalith and health care decision-making style. J Gerontol B Pshychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(5):261.

- Slovic P, Peters E. Risk perception and affect. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(6):322–325. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00461.x.

- Gustafsod PE. Gender differences in risk perception: theoretical and methodological erspectives. Risk Anal. 1998;18(6):805–811. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.1998.tb01123.x.

- Rana IA, Bhatti SS, Aslam AB, et al. COVID-19 risk perception and coping mechanisms: does gender make a difference? Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021;55:102096. Mardoi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102096.

- Straus SE, Tetroe JM, Graham ID. Knowledge translation is the use of knowledge in health care decision making. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(1):6–10. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.016.

- Brainerd CJ, Reyna VF. Gist is the grist: fuzzy-trace theory and the new intuitionism. Dev Rev. 1990;10(1):3–47. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(90)90003-M.

- Christensen N, Black L, Furze J, et al. Clinical reasoning: Survey of teaching methods, integration, and assessment in Entry-Level physical therapist academic education. Phys Ther. 2017;97(2):175–186. doi:10.2522/ptj.20150320.

- Edwards I, Jones M, Carr J, et al. Clinical reasoning strategies in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2004;84(4):312–330. doi:10.1093/ptj/84.4.312.

- Furze J, Kenyon LK, Jensen GM. Connecting classroom, clinic, and context: clinical reasoning strategies for clinical instructors and academic faculty. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2015;27(4):368–375. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000185.

- Kushniruk AW. Analysis of complex decision-making processes in health care: cognitive approaches to health informatics. J Biomed Inform. 2001;34(5):365–376. doi:10.1006/jbin.2001.1021.

- Vahdat S, Hamzehgardeshi L, Hessam S, et al. Patient involvement in health care decision making: a review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(1):e12454.

- Geerars M, Wondergem R, Pisters MF. Decision-making on referral to primary care physiotherapy after inpatient stroke rehabilitation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30(5):105667.

- Mackenzie JA, Lincoln NB, Newby GJ. Capacity to make a decision about discharge destination after stroke: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22(12):1116–1126. doi:10.1177/0269215508096175.

- Durocher E, Gibson BE. Navigating ethical discharge planning: a case study in older adult rehabilitation. Aust Occup Ther J. 2010;57(1):2–7. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00826.x.

- Khizar B, Harwood RH. Making difficult decisions with older patients on medical wards. Clin Med. 2017;17(4):353–356. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.17-4-353.