Abstract

Purpose

Participation difficulties among adults with developmental coordination disorder (DCD) have been documented. However, little attention has been given to the subjective aspects of participation, also called occupational experience, including feeling during engagement in activities and their meaning. This study aimed to explore the occupational experience of young adults with DCD.

Materials and methods

Informed by the phenomenological approach, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 10 young adults with DCD.

Findings

Three themes emerged: (1) Complexity of occupational experience; describes the motives for participation, with variations in experience across activities and individuals. Participants engage in activities that provide them with pleasure and fulfillment, while other activities require constant effort and cause stress and shame; (2) The role of internal factors; illustrates the influence of poor motor and organizational/planning skills, self-acceptance; and utilizing strategies on the participants’ occupational experience; and (3) The role of the social environment; reveals the participants’ dual perception of their environment – as a source of criticism as well as a source of support.

Conclusions

Individuals with DCD may benefit from intervention during young adulthood to enhance their well-being. The interventions should target their subjective occupational experiences in addition to their objective performance difficulties, by enhancing their psycho-social resources.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Occupational experience, the subjective experience of participation in daily activities, is vital for well-being.

The occupational experience of young adults with developmental coordination disorder (DCD) varies across activities, including daily struggles with household tasks and work.

Rehabilitation clinicians and researchers are encouraged to relate to the subjective occupational experience of young adults with DCD in addition to objective performance difficulties.

Well-being may be enhanced by altering the occupational experience of young adults with DCD, by fostering self-acceptance and support developing adaptive strategies and social resources.

Introduction

Participation, a central determinant of health and well-being, is a multidimensional construct [Citation1]. It consists of both objective aspects (e.g., frequency of engaging in activities, and level of performance) and subjective aspects called “occupational experience” [Citation2,Citation3]. Occupational experience, the subjective experience of participation, refers to the individuals’ feelings while engaging in activities, such as enjoyment, persistence, productivity, connectedness to others, or feelings of renewed energy [Citation1,Citation2,Citation4]. Occupational experience also relates to the personal meaning and importance that individuals attribute to their engagement in activities, such as will, values, choices, and control [Citation2,Citation3]. These objective and subjective aspects of participation are inter-related; they are viewed as the product of interaction involving one’s biological characteristics, psychological factors, social factors, and health condition [Citation1,Citation3]. Objective participation limitations, as well as adverse occupational experiences, pose a risk to one’s self-identity, quality of life, and well-being [Citation1–3].

Among the populations that encounter participation limitations are individuals with developmental coordination disorder (DCD) [Citation5]. DCD is prevalent among 5–8% of school aged children, defined by major motor-coordination difficulties that significantly and persistently affect performance and participation patterns in everyday life [Citation6,Citation7]. These limitations emerge in education, sports, and social life [Citation5,Citation8]. The motor difficulties persist into adulthood [Citation9] among 50–70% of the children [Citation7], however, there is lack of empirical data regarding the incidence of DCD diagnosis in the adult population. The motor difficulties are accompanied by executive function difficulties [Citation10,Citation11], as well as psycho-social adversities such as low self-efficacy [Citation12] and increased risks of experiencing loneliness, depression, and anxiety [Citation13].

The few studies regarding DCD participation in adulthood refer mainly to the objective aspect of participation (e.g., performance difficulties). Preliminary studies have suggested that as individuals with DCD mature, they are able to master self-care activities [Citation14], and that their social participation may be similar to their non-DCD peers [Citation15]. Yet they are less likely to be involved in activities performed with others, such as leisure activities [Citation14,Citation16]. Additionally, activities of daily living were found to be a major concern for these individuals [Citation10], such as driving, packing a suitcase, managing money and time, or organizing equipment [Citation14]. Only a limited number of studies have addressed the occupational experience of adults with DCD. They reported negative emotions (e.g., frustration, anger) and stress while performing activities [Citation16,Citation17].

Qualitative methods are particularly suited to the research of questions related to understanding occupational experience [Citation18]. To date, qualitative research exploring the lived experience of DCD has mostly focused on the perspectives of parents, educators, or children and adolescents themselves [Citation19]. Literature on the adult perspective is generally limited to describing their retrospective report on experience as a child with DCD, or their occupational experience in specific life domains [Citation16,Citation20,Citation21]. Moreover, in the few studies mentioned above, participants were defined as having probable or suspected DCD based only on childhood diagnosis or self-report questionnaires, and not based on all the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders – 5th edition (DSM-5 (diagnostic criteria for DCD. These previous studies also did not exclude individuals with co-occurring prevalent neurodevelopmental disorders, which may have influenced the findings [Citation7].

The high prevalence of DCD, and its significant impact on participation and well-being, calls for a better understanding of participation in the unique phase of young adulthood. In order to comprehensively grasp the participation limitations of individuals with DCD in adulthood, their own perspective on their current experience while engaging in daily activities should be recognized and valued. Exploring the subjective aspects of participation – the occupational experience – may deepen our understanding of the interrelations of participation, health, and well-being [Citation2,Citation4] for this population. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of young adults with DCD regarding their occupational experience in everyday activities, and to identify the factors they view as contributing to their experience.

Materials and methods

Qualitative research methods are based on philosophical beliefs, emphasizing subjective experience of how the world is perceived as an approach to reality [Citation22]. Specifically, this study was informed by a hermeneutic phenomenological approach, which is influenced by the philosophy of Heidegger and Gadamer [Citation23]. The phenomenological approach is ground in individuals’ personal knowledge about a concept or phenomenon and aspire to explore, understand and interpret people’s common experience as they are perceived in consciousness and the underlying meaning that people attribute to their lives [Citation18]. The hermeneutic phenomenology approach further acknowledges that the researcher’s understanding of a phenomenon is influenced by their pre-existing conceptions, hence requiring ongoing reflection on their values, beliefs, and knowledge [Citation23].

Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited via notices posted on social media. The notices stated that, for research purposes, we are searching for young adults with DCD or those who have experienced motor difficulties in childhood (such as a tendency to fall or bump into objects, illegible handwriting, difficulties in learning complex motor activities such as driving or sports exercises). The adds also invited those who are interested to contact the PI. In this study, each interview was analyzed before the next interview was conducted. After two interviews failed to yield new codes, thereby meeting the criteria for saturation [Citation24], the recruitment stopped. In this study, saturation was reached after ten participants. This sample size is aligned with other phenomenological studies which explored adults with DCD [Citation16,Citation20].

Participants met the following inclusion criteria: (a) aged 21–35, (b) Hebrew-speaking, and (c) met the four criteria of the DSM-5 for DCD [Citation6]. In relation to criterion A, participants obtained a score in the 0–5 percentile (standard score ≤ 5) on the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition, age band 3 (M-ABC-2) [Citation25]. Criteria B and C were established based on an interview, and a score in the 0–15 percentile on the Adolescents and Adults Coordination Questionnaire (AAC-Q) [Citation26]. Criterion D, the elimination of other medical conditions that might explain the motor difficulties, was established based on participants’ self-report of attending general education schools (indicating normal IQ), and their self-report of not having additional neuro-sensory difficulties (e.g., epilepsy, visual impairment, or cerebral palsy).

Although many individuals with DCD also have co-occurring disorders [Citation6,Citation7], in this study we aimed to understand the unique occupational experience of young adults due to their DCD, not influenced by accompanying disorders. Therefore, we excluded individuals if they reported having a co-occurring neurodevelopmental disorder, or an additional health condition such as a psychiatric disorder, cancer, diabetes, etc. Moreover, since attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) is the most frequent co-occurring disorder among individuals with DCD [Citation7], it was additionally screened out by using the ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS v1.1) [Citation27].

In reply to our advertising of the study on social media, we received 37 applications. Participants were gradually invited to undergo the screening battery (n = 23) with the purpose of examining their meeting of the study criteria. Those who met the criteria were interviewed. When approaching the potential participants, we considered various factors such as gender, education, etc., to ensure diversity of the sample (see also Trustworthiness section). We continued this process until we reached saturation (n = 10), and hence 14 potential participants were not invited to participate in the study.

The ten participants were aged 21–31, and half were females. Most of the participants resided with romantic partners, and none had children. The majority of the participants either owned a higher-education degree (one graduate degree and five undergraduate degrees), or were undergraduate students (n = 2), while the youngest participants had completed their high school studies (n = 2). Although none of the participants had been diagnosed in childhood with DCD, all had received professional support during childhood (occupational-, physio-, or speech therapy), and six reported being currently engaged in psychotherapy treatment ().

Table 1. Participants’ demographic information.

Measures

Movement Assessment Battery for Children, second edition, age band 3 (M-ABC-2) [Citation25]

The M-ABC-2 is a test designed to measure fine and gross motor skills in three domains: manual skills, ball skills, and static and dynamic balance. It is considered a gold standard for diagnosing DCD [Citation7]. The standard scores for each domain are summarized and converted to percentiles (0–5%, significant motor difficulties; 6–15%, at risk for motor difficulties; 16–99.9%, without motor difficulties). The M-ABC-2 is designed and norm-referenced for individuals up to the age of 16. However, it was found to be feasible for motor assessment and as an inclusion criterion for diagnosing adults [Citation9,Citation10].

Adolescents and Adults Coordination Questionnaire (AAC-Q) [Citation26]

The AAC-Q is a valid screening questionnaire designed to detect motor coordination difficulties reflected in everyday activities, among adolescents and young adults aged 16–35. The 12 items of the AAC-Q are measured on a 5-point scale (5 = “always experience difficulty” to 1 = “never experience difficulty”), yielding scores ranging from 12 to 60. Cut-off scores of 26–30 (represent the 5th to 15th percentile) indicate borderline DCD and scores of 31 or above (represent a score below the 5th percentile) indicate probable DCD.

Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS; version 1.1) [Citation27]

The ASRS is a valid self-report questionnaire for ADHD screening according to current symptoms. It consists of 18 items that are measured on a 5-point scale (0 = “never” to 4 = “very often”), yielding scores ranging from 0 to 72. A score ≥ 51 is predictive of symptoms consistent with ADHD [Citation28].

Semi-structured interview

The interviews followed a manual containing general guiding questions regarding challenges and successes in daily routines, and additional prompts to elicit the participants’ perspectives and interpretations of their experience (). Although the interview was based on a predetermined interview guide, the order of the questions was flexible; an empathic attitude was employed, allowing the participants to tell their stories in their own way and to develop trust.

Table 2. Interview questions.

Procedure

Ethical approval was received from the institutional research board (IRB) of the Hebrew University (Approval no. 14012021). Young adults who expressed interest in participating signed an informed consent form and were administered the test battery. Participants who met the DSM-5 criteria for DCD were interviewed. The interviews were conducted in a similar way by the first author, face-to-face or via the Zoom platform (according to the participants’ choice), and lasted for approximately 2 h (ranging from 1:53 to 2:05 h). The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, and all names were changed to pseudonyms. The participants were financially compensated for their time.

Data analysis

We used the Narralizer software to analyze the interviews. Each interview was analyzed before starting the next interview. The analysis followed the qualitative conventional content analysis method [Citation29] with additional steps required by the hermeneutic phenomenological studies [Citation23], to uncover the underlying meanings and structures of participants’ occupational experience. First, the researchers read the transcribed interviews separately, wrote analytic notes, and discussed their first impression of each interview as a whole with the team members [Citation23,Citation29]. Then, each researcher, separately, continued to analyze the data while identifying and coding the units of meaning [Citation29]. Next, the researchers discussed similarities and differences in their coding, and whether or how the codes related to the meaning of the interview as a whole [Citation23], until unanimous agreement on coding [Citation29]. During the data analysis, the codes were compared across interviews and were reviewed and modified, until a master list of codes was created with and explicit significance of each code/meaning unit. Then, the researchers, together, discussed patterns identified across interviews and the classification of codes into meaningful categories until unanimous agreement was reached. Finally, the researchers discussed the relationship among the categories and organized them into themes [Citation29]. See for examples of the analysis process.

Table 3. Examples from the analysis process.

Trustworthiness

To enhance trustworthiness and reduce potential bias in the findings, multiple strategies were employed [Citation18,Citation30]. As stated above, we approached the potential participants in a manner that ensured a diverse range of characteristics, such as gender, age, urban/rural settings living and religious affiliation, providing different perspectives to the phenomena under the research focus. When participants had similar characteristics, priority was given to the first applicant to minimize selection bias. Second, all interviews were conducted during a 2-month period by the same researcher (the first author, S.Z.V.), following an interview manual that included consistent introductory questions, ensuring dependability.

Additionally, bracketing techniques [Citation23] were used. First, to strengthen dependability of the findings, we applied triangulation, using three different researchers analyzing the data [Citation30]. Second, the research team engaged in ongoing reflection on their ideas [Citation30], perspectives and thoughts, to challenge their personal prior assumptions and professional acquittance with individuals with DCD. The first author (S.Z.V) conducted all the interviews and applied the motor test battery. Therefore, to track the impact of her pre-assumptions [Citation23] on the interviewing process, prior to the interviews she reflected on her perspective as a young adult herself and on her former perspective on the participants’ behavior in their interaction during the motor examination. This was particularly important to ensure that the perspective shared by participant did not restrict the information that was gathered. The two other researchers, occupational therapists had many years of experience working with young adults with DCD.

Findings

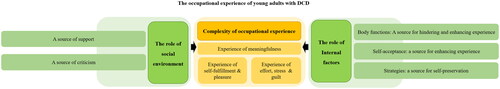

The analysis revealed three themes: (1) Complexity of occupational experience; (2) The role of internal factors; and (3) The role of social environment (); all included in the main theme: The occupational experience of young adults with DCD.

Figure 1. Themes and categories elicited from interviews.

A review of the narratives provided by participants indicated that they were able to identify experiences they felt were not related to DCD, such as specific life events (e.g., fertility treatment, COVID-19 isolation, etc.) or other health issues (e.g., toothaches), as opposed to experiences due to their DCD. For example, one participant distinguished between challenges she experienced at work as a new employee and those stemming from her DCD. We believe that this distinction increased the reassurance that the themes that were identified reflected the occupational experience of participants with DCD rather than other factors.

Theme 1: complexity of occupational experience

Experience of meaningfulness

The participants described involvement in all areas of life – working, studying, maintaining romantic and social relationships, and managing their household. They shared the meaning and motivation they derived from engaging in their daily activities. All the participants strongly emphasized at least one of their activities as a reflection of who they were; their traits, interests, identity, or values. Gabriel shared his attitude towards his clinical fieldwork as a student: “I have an opportunity to do good and help patients who really need support, which is something that very much guides me in my desires and decisions.”

Interestingly, most of the participants acknowledged that they also derived meaning from engaging in activities they felt that had to be done because the activities were critical for life maintenance or health considerations, especially sports or household tasks:

I persisted in exercising 7 minutes every day for 2 months, using an app. It wasn’t fun, but I did it because it’s healthy, because I wanted to look better, because it’s important to maintain the body. (Abigail)

Finally, the needs and wants of their social environment, especially romantic partners, motivated them to engage in activities. Shay explained: “I’ll make an effort to do something when it’s essential to my environment. When it’s important to my girlfriend that I complete a particular task, in the proper way, then it’s important for me too.”

Experience of self-fulfillment and pleasure

Participants repeatedly described engaging in leisure activities and social interactions as a source of pleasure and enjoyment. These activities were relaxing, rejuvenating, and improved their mood:

Being with people I love, doing spiritual things, like crafts, playing music, hiking and being in nature calms me down. It seems to balance the stress and madness I feel sometimes. (Abigail)

Experience of effort, stress, and guilt

Alongside experiencing pleasure and fulfillment, participants also described the mental and emotional cost of engaging in daily activities. One reason was that they experienced activities that most people considered relatively easy, as effortful and frustrating, such as cooking a simple meal, hammering a nail into a wall, or making a bed:

Every task requires many mental resources; my brain is working very hard. The simplest thing requires me to think, ‘How do I dip the rag in the bucket, and how, and at what point should I wring the water out?’ (Maya)

It’s not possible for a 25-year-old to have difficulty doing such easy chores. It’s disgraceful. So I hide it, because it’s not normal. I’m not normal. (Shay)

These lifelong snags caused me to distrust my body. Feeling disappointed by my body after such experiences is extremely difficult and embarrassing. (Natalie)

I like to do things slowly. To fold laundry slowly, to cook slowly. When it’s not possible, there is a lot of stress. I feel bad at the end, and get upset about anything that goes wrong along the way. (Gabriel)

In fact, a “vicious cycle” is created, some tasks provoke stress and anxiety, which in turn, make it difficult to perform the task. Stress and fear were also described in relation to the participants’ future life roles:

What will happen when I have children? Will I have more difficulties? How will I raise them? How will I give birth? How will I maintain a bigger house? [.] I have a sense of failure and fear about the future, a kind of helplessness. (Maya)

Theme 2: the role of internal factors

Participants discussed the role that they believed internal factors (i.e., factors intrinsic to the person, such as skills, psychological traits, and behaviors) played in their occupational experience.

Body functions: a source for hindering and enhancing experience

When participants described their efforts and daily struggles, they asserted that poor motor and organizational/planning abilities hindered their performance. For example, they attributed the challenges of cooking several dishes simultaneously, or of eating neatly while talking, to their poor attention or coordination abilities. Shay: “Things like arranging or organizing, that require physical actions, don’t always go well for me. What I have is not only expressed in motor skills, it’s also expressed in my ability to organize space. These are all things I have a hard time with; ‘it’ crosses life domains.”

Furthermore, the participants noted that the above-mentioned abilities are the reasons why their quality of performance is limited. As such, they believed that even with great effort, there is a level of performance which they could not surpass. Gabriel shared his experience in firearms training as part of his work as a guard: “Obviously I don’t perform very well; at best I can reach a reasonable level. It’s the same with cleaning and tidying - I can try harder, but there is just a certain level that I cannot pass.”

Alongside poor skills that negatively affect their occupational experience, participants also recognized personal abilities that enable them to maintain significant life roles. Among these strengths, the most frequently mentioned was interpersonal skills (sensitivity and empathy), which some attributed to their challenging life experience of having DCD. Sarah stated: “In my family, we joke that I’m the psychologist, because everyone confides in me. That’s what matters in life, that’s what I’m glad God gave me.”

Self-acceptance: a source for enhancing experience

Although they were aware of their poor motor and organizational skills, participants expressed a compassionate attitude towards themselves, accepting their difficulties as well as their poor capacities:

I’m at peace with my challenges. It’s who I am. That’s what I have, and that’s good enough. (Sarah)

There is an acceptance and knowing of what I am good at, and what I am less good at, and an attempt to think more about the things I’m good at. (Shay)

I say to myself, ‘I’m not good at this, but my self-worth doesn’t hinge on it; I’m good at other things’. My ‘difficulties’ don’t determine who I am. That way, I can just try and experience things and not avoid them; and I feel much less frustrated. (Gabriel)

Strategies: a source for self-preservation

Participants mentioned using various strategies that enabled them to engage in activities, supported their sense of confidence and control, and reduced the stress associated with performance. The most frequent strategies mentioned were performing activities in a fixed order according to a checklist, planning ahead, repeating an action multiple times, and performing tasks slowly. David described the enabling routine he created as a teacher: “I arrive at school an hour before everyone else in order to do things slowly and without anyone breathing down my neck, without the stress.”

Yet several participants noted that these kinds of strategies required extra time and effort, and therefore were not always efficient. The participants also mentioned other facilitating strategies, such as environmental adaptations:

I bought a bag with compartments to put in my keys and pens, so I wouldn’t forget them. (Adam)

I need luxury facilities, like a kitchen with a dishwasher. It’s much easier than dish washing by myself. (Maya)

If I’m going somewhere, I almost always work closely with Google Maps, or else I’ll get totally lost. Reminders and e-calendars are also useful. (Dan)

The key to avoiding failures is to find the areas and level of challenge that I can deal with; jobs that don’t make me too frustrated or too sad. Everywhere I went, I tried to orient myself to do things I was good at. For that matter, at the restaurant where I worked, I told them, ‘Let me be a barista’, since it’s one action with a clear beginning, middle and end. (Ruth)

When you grow up, you can do more of what you want to do, and don’t have to do what you don’t want to do. It was really easy to just get older. (Nathaly)

Theme 3: the role of social environment

The third theme offers insight into participants’ perceptions of the role of their external-social environment in their daily occupational experience. In their views, their social environments played a dualistic role, both hindering and supporting their occupational experience in activities.

The social environment as a source of support

Participants found a sense of safety and comfort in the presence of accepting peers, family members, and spouses, whose accepting and nonjudgmental attitudes allowed them to make mistakes without feeling shame. This supported their sense of competence and willingness to participate in activities which they do not perform well or usually avoid:

My friends wanted to drill a hole in their wall. I insisted that I would drill that hole [.]. I did it at my friends’ home because they know me and I feel very safe with them. I wouldn’t do it in the presence of someone else. (Gabriel)

The people around me help me process how I feel by talking with me, or thinking of ways to do things, or sometimes they even come up with practical solutions. My family and friends are very helpful in that, and also, as a source of support, and a place where I can let go for a moment and not be stressed.

Knowing my difficulties, my mother tries to reduce them to a minimum. She says, ‘Maya, come back and live at home with us’. In contrast, my boyfriend’s mother comes and helps me in my apartment. She pushes me to try. She says, ‘You’re gonna succeed’. That’s more helpful for me. (Maya)

The social environment as a source of criticism

Participants also identified negative attitudes towards them from their social environments. They described feeling misunderstood, with their behavior interpreted in a negative manner since others associated specific failures with a general inadequacy. Gabriel described: “I hate that people link clumsiness with irresponsibility, like ‘you can’t trust a clumsy person.’ People think that if you don’t notice that you dropped your glasses, you probably also don’t notice other things.”

In addition, participants described that others criticize them with the assumption that they choose to be disorganized, attributing it to “carelessness.” Maya, Shay, and Gabriel agreed that others see their challenges as weakness, and accordingly, they need to make an effort to hide them, especially at work. Maya: “No one at work knows anything about ‘it’. People don’t like weak or ‘needy’ people. It’s a repulsive trait. I want people at my job to trust me and allow me to try things, to believe in me.” (Maya)

Unsurprisingly, challenging actions that they performed in the presence of others were experienced as uncomfortable and stressful:

I had to hang some shelves. I prayed that my wife wouldn’t see me do it. But she was there, sizing me up. She saw that it took me a long time, and it made me even more frustrated and delayed my ability to succeed. I was constantly worrying that she thinks I’m helpless. (David)

Discussion

This study endeavored to describe the perspectives of young adults with DCD regarding their occupational experience, the subjective experience of participation in everyday activities. Currently, there is initial evidence that adults with DCD experience performance limitations in various life domains, the objective aspect of participation (for reviews see Blank et al. [Citation7] and Tal-Saban and Kirby [Citation5]). However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that provides data on their subjective occupational experience in the specific phase of young adulthood. Therefore, we chose the Phenomenological approach, which focuses on exploring participants’ personal worlds and aims to understand the structures and essences of their experiences, while setting aside pre-assumptions about reality [Citation18].

This study is unique in two additional aspects. First, it focused on individuals with DCD without co-occurrence of other neuro-developmental disorders. Second, in the participants’ selection, we confirmed Criterion A of the DSM-5 DCD diagnosis criteria [Citation6], i.e., the existence of motor coordination difficulties based on an objective motor test, rather than relying only on self-reports.

Three major themes arose, based on the interviews of 10 participants, reflecting their beliefs regarding their occupational experience. These themes relate to the meaning that young adults with DCD attributed to their daily activities and their positive and negative experiences across activities. Additionally, the themes reflect the participants’ views regarding the role of internal and external social factors in these experiences.

This study’s findings support the bio-psycho-social perspective of health as portrayed in the International Classification of Function, Health, and Disability (ICF) framework [Citation1]. The ICF framework provides a description of health and disability conditions. It asserts that participation (objective aspect and occupational experience) of an individual are not only based on one’s biological characteristics (referred to as “body function and structure”), but also on social factors (referred to as “environmental factors”) including social support, as well as psychological factors (referred to as “personal factors”) such as self-acceptance. The findings are also congruent with the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) [Citation3], emphasizing the motivational forces behind human engagement in activities. In the Discussion, we interpret the study’s findings in light of the ICF framework and the MOHO. We also elaborate on the interaction between daily occupational experience, well-being and bio-psycho-social factors, including motivational constructs, among young adults with DCD.

Occupational experience in everyday activities

Our findings showed that the participants engaged in activities in all domains of life. Yet, there were intra-, and inter-variability across life domains, involving both the level of performance difficulty and the feelings that engagement in activities elicited. All participants described positive occupational experiences while engaging in at least one life domain (mainly romantic relationships and work), gaining fulfillment, self-worth, and positive self-image from successes. These findings were unique, given that very few studies have discussed positive experiences among individuals with DCD throughout childhood and adolescence [Citation19]. Similar to previous studies [Citation17], the participants also noted difficulties they experienced while engaging in various activities. However, as opposed to children and adolescents with DCD [Citation19], the difficulties described by the young adults in this study extended beyond academic functioning, sports activities, or social interactions, to also include simple household chores, such as cleaning and cooking or work. Such tasks were time-consuming, entailed cognitive effort, and required a quiet environment or external support.

Similar to children [Citation19], the objective difficulties described by the young adults with DCD were associated with a negative occupational experience of frustration and a sense of reduced control over life. Furthermore, the findings indicated that the feelings of shame for having limitations and being marginalized, which are common among children and adolescents with DCD [Citation16,Citation19,Citation20], continued in adulthood, when the participants compared their own performance to the norms expected from adults.

The adverse occupational experience may underlie the risk of individuals with DCD to experience reduced mental well-being, i.e., to face depression and anxiety [Citation13]. Zimmer and Dunn [Citation31] suggested that the “daily hassles” constantly experienced by children with DCD, due to manifestation of motor difficulties during physical group activities, can evoke accumulating stress that poses a risk to mental health and well-being. Our findings confirm their perspective, showing that for young adults with DCD, difficulties with organizing and planning tasks (and not only motor tasks) in every life domain (and not only sports activities), along with perceived negative social interpretations of these difficulties all constitute stressors. Performance difficulties also cause stress by raising concerns regarding future functioning, which may translate to general anxiety unrelated to performance. Additionally, stress itself can hinder performance, starting a vicious cycle between performance difficulties and decreased mental well-being.

Furthermore, the participants provided insight into the meaning they attributed to certain activities, which enhance their motivation to engage in them. For example, they noted that participation in some activities symbolized gaining independence and overcoming their limitations. These motives and meanings coincide with the MOHO [Citation3], which suggests that the ‘volitional system’ determines individuals’ level of participation in activities, based on their expectations regarding their quality of performance, their experience while performing the activity, and their values and interests. The participants noted that they frequently engaged in activities that challenged them because it was important to them, or they felt it was important to their spouses, or because they believed that those activities were expected from adults. Furthermore, these young adults with DCD stated that their decision to engage in challenging activities reflected their autonomy (choosing activities according to their values and interests), and provided the opportunity for successful experiences, which resulted in a sense of accomplishment. Yet, on the other hand, the decision also exposed them to a potentially negative occupational experience in terms of effort and stress, posing a risk to their well-being.

The role of internal (biopsycho) and external (social) factors in occupational experiences

Our findings provide insight into how the participants with DCD interpret internal and external-social factors as influencing their occupational experience. Participants associated their poor motor and organizational/planning skills (i.e., executive functions) with their inability to meet high performance standards, along with the experience of extra effort, stress, and reduced control. These findings support and extend earlier findings showing that movement-related anxiety is higher among adults with DCD compared to their non-DCD peers and is associated with their self-efficacy [Citation12]. In addition, our findings support previous studies suggesting that the difficulties of adults with DCD in daily activity performance was most prominent in executive function-related activities [Citation10,Citation11], which caused more anxiety than movement-related activities. It is interesting to note that the young adults with DCD in this study attributed their difficulties to their body-function deficits, even though they had never been formally diagnosed with DCD or received a professional explanation concerning their difficulties. Concurrently, similar to previous studies [Citation15], the participants acknowledged their interpersonal skills as a major strength, which supported and enhanced their participation.

The participants further identified acceptance (both self- and social) of their difficulties as factors that encouraged them to engage in challenging activities and enhanced their occupational experience, while also reducing frustration and stress in facing failures. These findings are in line with previous studies among adults with various neurodevelopmental disorders, with respect to self-acceptance [Citation32,Citation33] and social acceptance [Citation32,Citation34]. Concurrently, positive occupational experiences supported the participants’ self-acceptance; it allowed them to accept their difficulties in various areas of performance by focusing on their strengths. Moreover, young adults described that their self-acceptance and occupational experience were compromised by social lack of acceptance. When they felt that their social milieu misinterpreted their objective difficulties, attributing them to negative attitudes or traits (e.g., “carelessness”), the participants avoided engaging in challenging activities in public, had negative occupational experiences, and difficulty accepting themselves (i.e., shame and guilt). Similar to findings among adults with ADHD [Citation35], participants in this study also shared that negative social attitudes led them to exert much effort in concealing their poor skills, contributing to their negative occupational experience. Therefore, nonacceptance might accentuate the negative occupational experience already prevalent among individuals with DCD. However, these are only initial findings that should be further explored.

Alongside, the participants identified strategies that they developed throughout their lives, to support their performance by overcoming the gap between their poor skills and the task demands. This included executive strategies, altering task requirements, adapting the environment, and finding activities that pose just the right alternate challenges. Use of these strategies reflects the participants’ self-awareness of their poor motor and organizational/planning skills, compared to a given task’s demands, and their need to bridge the gap [Citation36]. Similar to various earlier studies [Citation8,Citation16,Citation17,Citation21], participants described the utility of such strategies for enhancing their performance in multiple life domains. The findings of our study extended this evidence, by shedding light on how to harness the significance of these strategies to support positive occupational experience, thus decreasing the feeling of effort, stress, and shame while engaging in challenging activities.

Finally, participants acknowledged that besides emotional support, they also required practical support in performing daily activities such as shopping or task organization. Evidence has shown that children with DCD require specific support [Citation19]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first studies indicating that this need persists into young adulthood. Similar to previous studies among adults with DCD [Citation16,Citation21], the participants in our study identified their support network as including their family, friends, and spouses. However, they indicated that while this support helped in practical ways, it also taxed their positive occupational experience, eliciting feelings of guilt for being “a burden” to their loved ones. This was especially difficult in relationships with romantic partners. The feeling of shame appeared to be unique to this developmental stage; but as this is one of the first studies reporting such a finding, it should be further examined, including its effect on marital relationships.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, although our analysis showed that we reached saturation after a sample of ten participants, it is possible that there may be participant with experiences that were not represented in this study. Additionally, although there was variation among participants in line with phenomenology approach, some characteristics were similar, such as romantic relationship status and the fact that the sample in this study encompassed highly educated young adults, and none were parents, which may limit transferability to other settings or groups. Furthermore, the authors reflected and were aware of their pre-assumptions on the phenomena under study. However, this process does not make the study completely bias-free; it may have been influenced by the authors’ professional perspective, personal experiences, and cultural background.

As part of our recruitment process, potential participants underwent testing to verify if they met the DSM-5 criteria for DCD. Attention should be given to the fact that none of the participants were formally diagnosed with DCD in childhood, due to the low rate of diagnosis of DCD in Israel; they may be considered probable DCD. However, they did meet all the DSM-5 criteria [Citation6], except that criterion D was based on self-report rather than a physician’s diagnosis. In addition, during the recruitment process, and specifically the fact that the participants were included in the study because they met the criteria, may have influenced their responses. Hence, findings of the study should be interpreted in this context.

Conclusions

Young adults with DCD are engaged in all life domains. However, they reported an adverse occupational experience of effort, frustration, and stress in their daily participation; for some of them this resulted in reduced mental and emotional well-being, including general anxiety, shame, and guilt. Young adults with DCD also reported a positive occupational experience of success, pleasure, and fulfillment, which related to internal and external factors. This indicates that young adulthood may be a crucial time for intervention with individuals with DCD. However, as these are only initial findings, we suggest further exploring both the qualitative and quantitative associations between occupational experience and quality of life and well-being among young adults with DCD. A key recommendation emerging from our findings is for evaluation and intervention in this population that will focus on subjective occupational experience, in addition to objective performance difficulties, in order to more deeply understand their participation profiles and well-being. A second recommendation for intervention is to focus on enhancing self-acceptance, and support developing adaptive strategies and social resources, as well as finding compatible tasks and environments that will meet their desires to engage in valued activities.

Acknowledgments

This research was not supported through any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors. The authors would like to thank all the interviewees who agreed to share their intimate experiences and participate in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Authors agree to make data and materials supporting the findings or analyses presented in their paper available upon reasonable request (via an email to the corresponding author). Data will be shared only if the request is ethically correct to do so, where this does not violate the protection of human subjects, or other valid ethical, privacy, or security concerns

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability & health (ICF). Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- Hammell KW. Self-care, productivity, and leisure, or dimensions of occupational experience? Rethinking occupational “categories”. Can J Occup Ther. 2009;76(2):107–114. doi:10.1177/000841740907600208.

- Kielhofner G, Kielhofner G. The model of human occupation. In: Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): F.A. Davis; 2009. p. 147–174.

- Atler K. An argument for a dynamic interrelated view of occupational experience. J Occup Science. 2015;22(3):249–259. doi:10.1080/14427591.2014.887991.

- Tal-Saban M, Kirby A. Adulthood in developmental coordination disorder (DCD): a review of current literature based on ICF perspective. Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2018;5(1):9–17. doi:10.1007/s40474-018-0126-5.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders – DSM-5®. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

- Blank R, Barnett AL, Cairney J, et al. International clinical practice recommendations on the definition, diagnosis, assessment, intervention, and psychosocial aspects of developmental coordination disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61(3):242–285. doi:10.1111/dmcn.14132.

- Gagnon‐Roy M, Jasmin E, Camden C. Social participation of teenagers and young adults with developmental co‐ordination disorder and strategies that could help them: results from a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42(6):840–851. doi:10.1111/cch.12389.

- Warlop G, Vansteenkiste P, Lenoir M, et al. Gaze behaviour during walking in young adults with developmental coordination disorder. Hum Mov Sci. 2020;71:102616. doi:10.1016/j.humov.2020.102616.

- Purcell C, Scott-Roberts S, Kirby A. Implications of DSM-5 for recognizing adults with developmental coordination disorder (DCD). Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78(5):295–302. doi:10.1177/0308022614565113.

- Subara-Zukic E, Cole MH, McGuckian TB, et al. Behavioral and neuroimaging research on developmental coordination disorder: a combined systematic review and meta-analysis of recent findings. Front Psychol. 2022;13:809455. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809455.

- Harris S, Wilmut K, Rathbone C. Anxiety, confidence and self-concept in adults with and without developmental coordination disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;119:104119. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104119.

- Harrowell I, Hollén L, Lingam R, et al. Mental health outcomes of developmental coordination disorder in late adolescence. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(9):973–979. doi:10.1111/dmcn.13469.

- Kirby A, Edwards L, Sugden D. Emerging adulthood in developmental co-ordination disorder: parent and young adult perspectives. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(4):1351–1360. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.01.041.

- Tal-Saban M, Kirby A. Empathy, social relationship and co-occurrence in young adults with DCD. Hum Mov Sci. 2019;63:62–72. doi:10.1016/j.humov.2018.11.005.

- Missiuna C, Moll S, King G, et al. Life experiences of young adults who have coordination difficulties. Can J Occup Ther. 2008;75(3):157–166. doi:10.1177/000841740807500307.

- Tal-Saban M, Ornoy A, Parush S. Success in adults with probable developmental coordination disorder using structural equation modeling. Am J Occup Ther. 2018;72(2):1–8.

- Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2013.

- O’Dea Á, Stanley M, Coote S, et al. Children and young people’s experiences of living with developmental coordination disorder/dyspraxia: a systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative research. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0245738. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245738.

- Ruiz-Perez LM, Palomo-Nieto M, Gómez-Ruano MA, et al. When we were clumsy: some memories of adults who were low skilled in physical education at school. J Phys Educ Sport. 2018;5:30–36.

- Scott-Roberts S, Purcell C. Understanding the functional mobility of adults with developmental coordination disorder (DCD) through the international classification of functioning (ICF). Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2018;5(1):26–33. doi:10.1007/s40474-018-0128-3.

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, et al. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):148. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7.

- Fleming V, Gaidys U, Robb Y. Hermeneutic research in nursing: developing a gadamerian‐based research method. Nurs Inq. 2003;10(2):113–120. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1800.2003.00163.x.

- Young ME, Ryan A. Post-positivism in health professions education scholarship. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):695–699. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003089.

- Henderson S, Sugden D, Barnett A. Movement assessment battery for children. 2nd ed. London (UK): Pearson; 2007.

- Tal-Saban M, Ornoy A, Grotto I, et al. Adolescents and adults coordination questionnaire: development and psychometric properties. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66(4):406–413. doi:10.5014/ajot.2012.003251.

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, et al. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med. 2005;35(2):245–256. doi:10.1017/S0033291704002892.

- Zohar AH, Konfortes H. Diagnosing ADHD in Israeli adults: the psychometric properties of the adult ADHD self report scale (ASRS) in hebrew. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2010;47(4):308–313.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Zimmer C, Dunn JC. A developmental perspective of coping with stress: potential for developmental coordination disorder research. Adv Neurodev Disord. 2021;5(4):351–359. doi:10.1007/s41252-021-00211-z.

- Cage E, Di Monaco J, Newell V. Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(2):473–484. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3342-7.

- Willoughby D, Evans MA. Self‐processes of acceptance, compassion, and regulation of learning in university students with learning disabilities and/or ADHD. Learn Disabil Res Pract. 2019;34(4):175–184. doi:10.1111/ldrp.12209.

- Dvorsky MR, Langberg JM. A review of factors that promote resilience in youth with ADHD and ADHD symptoms. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2016;19(4):368–391. doi:10.1007/s10567-016-0216-z.

- Barkley RA, Benton CM. Taking charge of adult ADHD: proven strategies to succeed at work, at home, and in relationships. New York (NY): Guilford Publications; 2021.

- Toglia J, Goverover Y. Revisiting the dynamic comprehensive model of self-awareness: a scoping review and thematic analysis of its impact 20 years later. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2022;32(8):1676–1725. doi:10.1080/09602011.2022.2075017.