Abstract

Purpose

Social isolation and reduced social participation are common after traumatic brain injury (TBI). Developing interventions that aim to increase social participation through recreation or leisure activities continues to be challenging. This scoping review was conducted to provide an overview of interventions used to increase social participation through in-person recreation or leisure activity for adults with moderate to severe TBI living in the community.

Methods

Using the Arksey and O'Malley framework, a scoping review of the literature published from 2005 to 2023 was conducted across four databases: Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Scopus. Quality appraisals were conducted for included studies.

Results

Following the removal of duplicates, 10,056 studies were screened and 52 were retained for full-text screening. Seven papers were included in the final review. Studies varied with respect to the type of intervention and program outcomes. The interpretation was impeded by study quality, with only two studies providing higher levels of evidence. Barriers and facilitators to successful program outcomes were identified.

Conclusions

Few studies with interventions focused on increasing social participation in leisure or recreation activity were identified. Further research incorporating mixed methods and longitudinal design to evaluate effectiveness over time is needed to build the evidence base for increasing social participation through leisure activity.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

There is evidence to support participating in recreation and leisure activities that involve interactions with others can increase social participation outcomes for adults with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury.

Participating in leisure-based interventions not only provides opportunities for social connection but may also impact positively on personal wellbeing, enjoyment, and confidence.

Understanding the range of personal, practical, support, and activity factors that can facilitate or obstruct participation in leisure or recreational activity programs at an individual level may improve social participation outcomes.

Measuring the impact of an intervention for social participation should include post-intervention changes across outcome domains and over time

Introduction

Every year approximately sixty-nine million people globally sustain traumatic brain injury (TBI), with 19% acquiring a moderate or severe injury [Citation1]. For those who survive the initial trauma, the complexity of the journey ahead cannot be underestimated. The impact of that “one moment in time” is life-changing, with future and long-term implications uncertain. Often the full extent of the neurological event and subsequent change in circumstance become more confronting when the person is residing within their community and attempting to construct a new life for themselves [Citation2]. At this time the psychosocial consequences of brain injury become more evident, and the person is frequently confronted with significant social losses; loss of friendships and social networks [Citation3], loss of previous leisure or recreational activities [Citation4,Citation5], loss of vocation and the structure, purpose and social connection provided therein [Citation6,Citation7], and loss of “self” [Citation8,Citation9]. Given these social and personal losses, it is not surprising that social isolation, loneliness and sadness have emerged as consistent themes within the TBI literature [Citation10–14], along with a correlation between loss of social connection, psychological wellbeing and quality of life [Citation15–17]. A recent study by Douglas [Citation3] explored the experience of friendship from the perspective of 23 adults with severe TBI and found that 61% of participants reported having no friends outside of family or paid carers. Significant associations consistent with moderate to large effects between number of friends and depression, strong-tie supports and quality of life were reported.

It is not only researchers who highlight the importance of social and community participation for quality of life after TBI. People with TBI consistently identify social connection and participation as important life goals. In a qualitative study by McColl et al. [Citation18] exploring individuals' experiences of community integration, “meeting new people” and “making new friends” emerged as important themes for people with TBI. Martin et al. [Citation19] also identified the significance of social connection and friendship when they explored life goals from the perspective of five participants with severe acquired brain injury (ABI) in a residential rehabilitation setting.

The construct of “social participation” is ill-defined in the field of ABI. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) defines “participation” as “involvement in a life situation” [Citation20]. Social participation is not specifically defined by the ICF, and thus a clear distinction between “participation” and “social participation” is not made [Citation21]. Furthermore, definitions of social participation across the literature vary and the concept is used interchangeably with terms such as social integration, social engagement, social connectedness, community participation, community integration, community engagement and so on. For the purposes of this review, social participation is broadly defined as a person's involvement in activities that provide interaction with others [Citation22]. This is captured in the ICF chapter “community, social and civic life” (d9), that covers engagement in social life outside family and includes recreation and leisure (d920) and socialising (d925) [Citation21].

Engaging in recreation or leisure activity offers people with TBI an important opportunity for social participation and connection with others, yet people with TBI are consistently found to have lower social activity levels post-injury compared to both premorbid levels and levels reported by comparison groups. For example, Wise et al. [Citation5] found that one year post-injury, 81% of people with TBI had significantly decreased leisure activity compared with premorbid participation. In an earlier study, Winkler et al. [Citation23] compared the leisure time of people with TBI with people who were unemployed in the general population and found that people with TBI spent significantly less time in recreation and leisure, more time alone, and less time with family. Fleming et al. [Citation4] found that participation in more socially oriented activities declined markedly following TBI. Commonly reported reasons for this decline were associated with post-injury disability, and barriers such as transport and finances, the latter a consequence of being unable to return to work.

Systematic reviews of recreation and leisure-based activity for people with TBI have found improvement in wellbeing and quality of life outcomes following participation in leisure activity programmes [Citation24,Citation25]. Given the value placed on social participation by people with TBI and its impact on emotional wellbeing and quality of life, several researchers have investigated factors that potentially shape social outcome after injury. Kersey et al. [Citation26] conducted a scoping review of the literature specifically looking at factors that facilitate community integration outcomes for people with TBI. They reported wide variability across findings, with some evidence to suggest that personal and environmental factors such as mood, disability, social support and social obstacles are meaningfully associated with community integration outcomes. They also highlighted the complexity of community integration as a construct, and the wide variability in tools used to measure it.

In view of the ongoing challenges associated with participation in community, social and civic life following moderate to severe TBI, along with the need to develop interventions to address the problem, this scoping review was conducted to (i) examine the existing evidence base, (ii) evaluate study characteristics, and (iii) map barriers and facilitators to successful social participation outcomes for people with moderate-severe TBI living in the community. We aimed to identify and evaluate studies that focused on increasing social participation, social connection, or community integration through in-person recreation or leisure-based activity. Our evaluation incorporated quality appraisal of studies and provided insight into factors determining successful social participation outcomes.

Method

Scoping reviews provide a rigorous and transparent method for mapping and summarising existing literature on a given topic [Citation27]. They provide an inclusive means for compiling and synthesising available evidence, not limited by study design, methods of data collection, analysis and quality, and can be used to identify gaps in evidence and priorities for future research [Citation27]. This scoping review followed the five-stage framework described by Arksey and O'Malley [Citation27], with the methodology modifications recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [Citation28].

Stage 1: identifying the research question

The specific research question underpinning the review was: what type of interventions have been used to support social participation through in-person recreation or leisure activity for adults with moderate to severe TBI? Within our review question, we defined three specific aims: (i) to provide an overview of the types of interventions that have been used to support people with moderate-severe TBI to connect socially with others through in-person recreation or leisure activities, (ii) to evaluate the impact of these interventions on social participation outcomes, and (iii) to identify barriers and facilitators contributing to reported social participation outcomes following participation in these interventions.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

A customised search strategy was developed by the authors in consultation with a research librarian. Three broad concepts (acquired brain injury, recreation/leisure activities, and intervention/rehabilitation) and their corresponding search terms were defined, and a systematic search of four databases (Medline, Cinahl, PsychInfo, Scopus) was conducted (see ). Search terms were adapted for use with each bibliographic database, with MeSH and Emtree headings used where appropriate. Searches were limited to studies involving human participants published in English from January 2005 through May 2023. This timeframe was considered appropriate given developments in contemporary brain injury rehabilitation approaches towards social participation and community integration, and the time periods covered by previous reviews in related areas. Research falling solely within the domains of dementia, military-acquired injuries, or psychotherapy was excluded.

Table 1. Search strategy.

Search terms for recreation and leisure were based on the recreation and leisure categories within the Activity and Participation domain of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework [Citation20]. The category “recreation and leisure” is defined as “engaging in any form of play, recreational or leisure activity, such as informal or organised sports, programs of physical fitness, relaxation, amusement or diversion, going to art galleries, museums, cinemas or theatres, engaging in crafts or hobbies, reading for enjoyment, playing musical instruments, sightseeing, tourism and travelling for pleasure.” [Citation20]. Specific examples of sports, crafts, hobbies and recreational creative pursuits were included as search terms. Details of terms used in the final Medline search appear in Appendix A.

Reference lists and forward citations of eligible studies were hand-searched, publications by the authors of included studies were identified using Scopus to screen for further relevant articles, and manual searches of three relevant journals (Disability and Rehabilitation, Brain Injury, Neuropsychological Rehabilitation) were completed.

Stage 3: study selection

The study selection process was informed and reported following the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [Citation28]. Peer-reviewed articles with extractable primary research data (quantitative or qualitative) were included. All study designs were considered. Non-empirical studies, reviews, books/book chapters, opinion pieces, study protocols and conference proceedings were excluded.

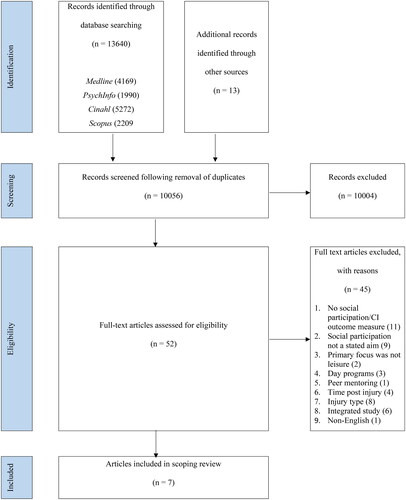

A yield of 13,640 studies was returned through a combination of database searching and other means, subsequently reduced to 10,056 once duplicates were removed. Due to the broad nature of search terms, most of these studies were irrelevant. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were revised to guide exclusion of irrelevant studies, with the following tightening or addition of criteria: (i) study population restricted to those aged 19 and over with moderate-severe TBI, initially two years post-injury but subsequently reduced to one-year post injury, (ii) discharged from inpatient rehabilitation, and (iii) a minimum of 33% of participants in the sample being identifiable as meeting these criteria. Reviews, studies that focussed on multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs covering several approaches, and studies with non-English content were further excluded. Title and abstract screening of 10,056 studies was conducted by the authors using Covidence software and uncertain studies were resolved via consensus. After this process 52 studies remained for full-text screening.

Stage 4: charting the data

This selection of 52 studies was reviewed in full by the authors, and data were charted relating to key aspects of the population under investigation (injury mix/type, time post-injury) and the study itself (aim/s, design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, intervention/activity, outcome measures, results). On appraisal of this data, studies without social participation as a primary outcome measure and those that did not involve in-person recreation or leisure activity were excluded (see ). Guided by these criteria and with discrepancies resolved by consensus, seven studies were retained for inclusion in this review. See for the full PRISMA/Search flow diagram.

Figure 1. PRISMA/Search flow diagram.

Table 2. Final inclusion and exclusion criterion.

Stage 5: summarising and reporting results, and evaluation of quality

The PRISMA-ScR checklist was used to guide the collating, summarising, and reporting of results [Citation28].

Quality appraisal

Methodological quality was evaluated independently by the first two authors using the following online tools: National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series studies [Citation29]; Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Qualitative Studies Checklist [Citation30], and Risk-of-Bias in N-of-1 Trials (RoBiNT) Scale [Citation31]. Consensus was achieved through discussion and involvement of the third author where required.

Results

Study characteristics and quality

Key study characteristics (authors, location, aims, participants, design, and interventions) are reported in . The seven articles deemed eligible for review spanned research from Australia (3), USA (2), Canada (1), and UK (1), and were published from 2006 to 2022. Designs were diverse and included four case series [Citation15,Citation32,Citation33,Citation35], two qualitative studies [Citation34,Citation36] and one single-case experimental design (SCED) [Citation37] that used a multiple baseline design across behaviours, with direct inter-subject and systematic replications. Three studies provided follow-up data varying from 1 to 6 months post intervention (see ).

Table 3. Study characteristics, aims, and interventions.

All of the case series studies used a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodology, but only one [Citation32] identified the type of qualitative analysis employed, that being thematic analysis. Of the remaining three, the collection and reporting of qualitative data involved quotes from participants on their program experience [Citation15,Citation33] and responses from interactive questionnaires [Citation35]. In their qualitative analyses, Donnelly et al. [Citation36] used inductive content analysis to explore the experience of attendees and carers in a community-based yoga group called Loveyourbrain, whereas Gibbs et al. [Citation34] used thematic analysis to understand the experience of surf therapy for people with ABI.

Studies were evaluated for methodological strengths and weaknesses (see ). Two studies provided higher levels of evidence through their SCED methodology [Citation37] and qualitative design [Citation36]. Tate et al. [Citation37] reported the outcome of their quality evaluation with the Risk-of-Bias in N-of-1 Trials (RoBiNT) scale [Citation31], and their findings were confirmed by the current authors. This study was found to have good external validity and moderate internal validity. The solely qualitative studies [Citation34,Citation36] were of appropriate research design and the results were well-described. One of these [Citation34] lacked in-depth description of data-analysis and evidence of triangulation. Case series designs provide low levels of evidence (level IV) according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [Citation38]. Within the four pre/post case series a variety of strengths and weaknesses were evident, with the most common problems being small sample size and lack of specific intervention detail.

Table 4. Quality of included studies.

Outcome measures

According to the ICF framework, outcome measures used by studies included in this review varied across type (e.g., functioning and disability, or global and multidimensional), component (e.g., activities and participation, body functions, or environmental factors) and domain (e.g., community, social and civic life, interpersonal interactions and relationships) (see ). All seven studies included a primary outcome measure targeting a domain under the component “Activities and Participation”, and four included a secondary outcome in this domain. Two studies used primary measures that fell solely under “Community, Social and Civic Life”, two employed a measure representing multiple domains, and four studies utilised treatment-specific measures (e.g., Goal Attainment Scaling and semi-structured interviews) as primary outcomes. Primary outcome measures from three studies encompassed domains under the component Body Functions (Mental functions – emotions, cognitive and global), and two employed these as secondary outcome measures. Environmental factors were measured in two studies, and Global and Multidimensional components such as Quality of Life, and Global life satisfaction were investigated in two studies as primary outcome measures and a further two as secondary outcome measures.

Table 5. Outcome measures mapped onto ICF domains.

Measures of social participation/community integration

As per the inclusion criteria for this review, all studies reported at least one measure of social participation as a primary measure. Of the five quantitative studies, two included additional social participation measures as secondary or adjunct outcome measures.

A variety of primary measures relating to social participation were used. These included the Community Integration Questionnaire (CIQ) [Citation40]), WHOQOL-BREF (social relationships domain) [Citation41], and Katz Adjustment Scale (frequency of free-time activities) [Citation42]. There were also two embedded items relating to social relationships within the Leisure Satisfaction Scale (LSS) [Citation43], but these were not reported individually. Non-standardised measures such as Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) [Citation44] were also included as measures of social participation for two studies [Citation33,Citation37].

The secondary or adjunct social participation measures included the Mayo Portland Adaptability Inventory – Participation scale (MPAI) [Citation45], Community Integration Measure (CIM) [Citation46], Lubben Social Network Scale [Citation47], and relevant items embedded within the Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire [Citation48]. See for the full list of measures and the studies in which they were used. Alongside social participation measures, other frequently used measures included well-being, quality of life, mental health, and self-esteem measures.

Interventions

demonstrates the marked variability in the type and delivery of interventions. All studies aimed to evaluate the impact of an intervention on social participation outcomes through participation in in-person recreation or leisure activity. The interventions were diverse; two studies were classified as Leisure Education Programs (LEPs) [Citation32,Citation33], three reported the impact of single activity group leisure interventions [Citation34–36,], and two described multi-option leisure interventions [Citation15,Citation37].

Leisure education programs

Two studies [Citation32,Citation33] described their interventions as LEPs, and although markedly different in nature, both incorporated multiple components with the aim of developing skills, awareness and confidence to facilitate autonomous engagement, satisfaction in leisure/recreation activity and increased community integration.

Carbonneau et al. [Citation32] provided a home-based individual program to elicit behaviour change and confidence in self-management of leisure activities. The underlying premise lay in understanding the personal meaning leisure activity held for each individual, and how this understanding impacted on leisure selection and ways to pursue leisure activity. As well as individual intervention sessions, participants were required to take part in self-selected leisure activity. The authors were interested in determining whether the benefits of the leisure program extended to community integration, well-being, and quality of life. Results were not statistically analysed due to it being a pilot study, however, two of the three participants demonstrated improved self-rated scores on the primary community integration outcome measure (KAS: frequency of free-time activities) at one-month follow up. All three participants showed improvement on the secondary measure of social participation (MPAI-4) at follow-up. Qualitative analysis revealed benefits that extended beyond the program such as increased confidence and greater autonomy. One participant joined a group activity with the aim of developing a new friendship, but the subsequent relationship was reportedly quite limited.

Mitchell et al. [Citation33] aimed to determine the effects of a group-based week-long LEP on leisure satisfaction, self-esteem and QOL in individuals with ABI. The program focused on social skill development and participation in group activities. Activities were selected according to individual choice and preference, with participants trialling at least six sporting, recreational, and social activities across the week. The overall aim was for participants to develop the confidence to continue with activities in their communities and have the social skills to meet people and form friendships in their own community. The results showed a significant improvement in social relationships on the WHOQOL-BREF at three-month follow-up but not immediately post-intervention, suggesting a cumulative impact of the program. Eighty-one percent of participants reported achieving their personal leisure, recreation, and social goals, and participant comments demonstrated ongoing increases in confidence and motivation.

Single activity group leisure interventions

Notably different approaches were used to explore the impact of leisure-focused group activity on social participation outcomes. Fraas and Balz [Citation35] examined the effect of a computer-based journal writing group on communication, emotional status, social integration and quality of life. Participants were supported to discuss and formulate ideas as a group, produce a piece of writing individually on a computer, and then email this to facilitators for feedback. The authors reported an unexpected decrease in scores on a measure of community integration (CIQ), which was attributed to an unrelated increase in social activity for all participants at the time of pre-assessment due to a fundraising event. Changes at the social participation level were reported anecdotally on completion of the program; one participant joined an external memoir group, whereas other participants described greater motivation to embark on new writing projects or seek work in a creative writing field.

The impact of a community-based “holistic” Loveyourbrain yoga intervention was investigated by Donnelly et al. [Citation36]. The program was designed to facilitate community integration and build relationships with others, incorporating breathing exercises, gentle yoga, guided meditation and facilitated group discussion with psychoeducation about topics relating to TBI. The researchers identified themes such as ease of participation, belonging, sustaining community connection, physical health, self-regulation, self-efficacy and resilience. The intervention was found to have positive physical and emotional outcomes, including improved strength and flexibility, better regulation of emotions and stress, and greater self-efficacy. Participants reflected positively on the value of the group discussion and psychoeducation in cultivating social connections. “Making friends” was highlighted as a positive outcome of the study, with half of the participants reporting they had sustained relationships with people they had met at the yoga group.

Gibbs et al. [Citation34] aimed to characterise individuals' experience of participating in a 5-week surfing intervention (Surfability). The program incorporated individual goal-setting and monitoring, with typical goals reflecting psycho-social outcomes such as socialising with new people. As well as developing surfing skills and techniques, sessions were designed to facilitate mindfulness, awareness of positive and negative feelings and experiences, and the experience of belonging in a group. One theme to emerge from qualitative interviews was “building community through social connection”, with the authors reporting that Surfability had provided an opportunity for those who were previously socially isolated to experience greater social connections and form meaningful social ties.

Multi-option leisure interventions

Douglas et al. [Citation15] evaluated a leisure service for people with severe TBI (Community Group Programs) that aimed to provide opportunities for people to engage in leisure activities and develop social networks. Twenty people with TBI were supported to attend a self-selected activity through scheduling, co-ordination of transport to activity venues, and training and consultation with relevant community support staff. After completion of the program, it was noted that three categories of participation had evolved naturally: those who had not attended any groups (no activity), those who had attended infrequently (unsustained activity), and those who attended regularly (sustained activity). Outcomes from this study showed a significant increase in social integration scores for participants in the sustained activity group only. Other positive health-related outcomes in the domains of mental health, depression, and quality of life were also reported for those in this group. Qualitative data revealed that individuals who had participated in activity groups reported positive responses such as feeling happy and more confident, highlighting their enjoyment of social aspects such as meeting other people and making friends.

Tate et al. [Citation37] adopted a “whole of life” philosophy, investigating the effectiveness of their Programme for Engagement, Participation and Activities (PEPA). The program aimed to develop goal-directed interventions to increase activity for people with TBI across three domains (leisure, social and lifestyle). The authors supported participants to choose individualised goals from a personalised menu of activities such as lawn bowls (leisure), phone contact with extended family (social), or cooking a meal (lifestyle). They used techniques similar to Goal Management Training (GMT) [Citation49] and metacognitive strategy instruction to develop underlying skills in planning, implementing, monitoring and solving problems around participating in leisure, social activity and other meaningful occupation. Target behaviours differed but were underpinned by a consistent target skill. Six participants met criteria for inclusion in this review. Clinically meaningful change in GAS scores was evident for four of these six participants in at least one domain. Two of these participants showed clinically meaningful change in GAS scores across each of the social, leisure and life-style domains. Although variability occurred across participants at various time points, statistically significant improvements were also reported on adjunct social participation measures and various secondary measures including social networks, quality of life, mood and self-esteem for individual participants.

presents the social participation outcomes and main findings as reported by the authors.

Table 6. Social participation outcomes and main findings as reported by authors.

Factors that facilitate or prevent participation in leisure/recreational activity

Barriers and facilitators to participation in leisure or recreational activities were identified within several of the included studies. Factors fell under four broad categories: personal considerations, practical considerations, support, and activity. Of the personal considerations, the ability to attach personal meaning to activities was found to facilitate participation and positive outcomes [Citation32], whereas severe cognitive impairment, mental health issues, or poor physical health were all found to be barriers [Citation15,Citation33–35,Citation37]. Practical considerations that facilitated participation included supported travel arrangements (both financial and physical) [Citation15,Citation36], whereas barriers included lack of financial and physical access (including distance) [Citation15,Citation33,Citation37], and incompatibility with timetables [Citation15,Citation36]. The presence of family, co-participants and professional support all acted as facilitators [Citation33,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37], whereas the absence of family support was noted to have a negative impact [Citation37]. Finally, factors pertaining to the activity itself had the potential to impact positively or negatively on participation. Individual choice and control over activities [Citation15,Citation33,Citation34], the opportunity to develop friendships, compatibility of group members, and enjoyment of the activity [Citation15,Citation34,Citation36] were all found to make a difference. (See for a full list of factors.)

Table 7. Factors that facilitate or obstruct participation in leisure/recreational activity.

Insert about here (Factors that facilitate or obstruct participation in leisure/recreation activity)

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to provide an overview of types of interventions that have been used to support social participation and social connection through in-person recreation and leisure activities for people with moderate-severe TBI. We also endeavoured to report on the social participation outcomes of these interventions and identify relevant contributing factors to successful outcomes. The search strategy covered studies published from January 2005 through May 2023, and a total of seven studies were found to meet the selection criteria.

Our findings highlight that interventions, outcome measures, and methods of data collection and analysis are diverse in this area of research. Interventions fell into three broad categories: LEPs, single-activity group leisure interventions, and multi-option leisure interventions. Some studies combined individual intervention sessions and group leisure or recreation activities [Citation32,Citation33,Citation35,Citation37], and others involved group activity only [Citation15,Citation34,Citation36].

Six studies reported positive change for at least some participants in social participation outcome measures after involvement in their intervention. Qualitative thematic analysis of the Loveyourbrain yoga intervention program [Citation33] and the Surfability program [Citation34] highlighted the social benefits of group activity. Further qualitative data from two other studies [Citation15,Citation32] revealed positive social outcomes such as meeting new people, enjoying the activity, and increased confidence. These results suggest that a range of approaches to supporting interventions for social participation in recreation or leisure activity can have a positive impact on social outcome for some individuals. Qualitative data enabled deeper understanding of the experience of participants in relation to social participation and social connection through leisure, and further substantiated quantitative outcomes.

Several personal and practical barriers and facilitators to participation in leisure activities were highlighted by various authors, including mental and physical health, social support from fellow attendees and family members, and factors pertaining to the activity itself, such as having choice and control. Many of these factors are consistent with those reported in Kersey and colleagues' [Citation26] scoping review on predictors of community integration following TBI. They found that mood had the strongest relationship with community integration, with depression and positive affect most strongly associated with negative and positive outcomes respectively. Given the high prevalence of depression amongst people with TBI [Citation50,Citation51], it seems prudent to monitor mood routinely to allow for timely and appropriate support and to maximise social participation outcomes. Consideration also needs to be given to building strong support systems to further facilitate successful social participation outcomes for individuals with TBI. As with any person-centred endeavour, a key ingredient to successful intervention in this area is likely to be placement of the individual at the forefront of decision-making, with careful consideration given to their interests, preferences and life circumstances [Citation52,Citation53].

Limitations

As is often the case with scoping reviews, our review has limitations. First, as a result of our inclusion criteria, our findings are limited to review of studies published in English and do not reflect the breadth of work potentially available in non-English publications. The population of interest was also restricted to adults with moderate-severe TBI and thus findings cannot be generalised to children, or adults with mild TBI. We also limited the focus of the review to studies where social participation was explicitly targeted in the aims of the program and excluded studies where social participation was not identified as a primary outcome. Thus our final yield does not reflect the results of studies where social participation findings are reported as secondary or post hoc observations that were not the primary focus of the intervention. In addition, while we firmly endorse consumer consultation in the context of scoping review methodology, we did not include the optional stage of consultation outlined in the framework proposed by Arksey and O'Malley [Citation27]. This decision primarily reflected the ongoing pandemic restrictions that were in operation during the course of this review. With respect to the development and evaluation of social participation programmes for people with disability, we consider the inclusion of consumer-focussed, codesign principles is essential. Indeed as well as being informed by the findings of this scoping review, our ongoing work on the development and evaluation of social participation programmes for people with TBI incorporates consumer-focussed exploration of factors and programme features that shape social participation in leisure-recreational activity after TBI [Citation52].

Finally, while scoping reviews are not required to weight findings based on study quality [Citation54], we consider it is important to ackowledge the design quality and methodological parameters of the final yield and to exercise caution when drawing conclusions about the success of interventions where weaknesses are evident. Thus, the variable quality and associated limitations of these studies must be taken into account when interpreting the findings of this review. Tate and colleagues' [Citation37] SCED study provided the highest level of evidence, as compared to the lower level inherent in case series design [Citation15,Citation32,Citation33,Citation35]. One qualitative study [Citation36] provided clear evidence of rationale and evaluation methods for confidence in reported outcomes, yet one limitation of this study with respect to the focus of this scoping review was the low number of participants with moderate or severe TBI (4/13) and subsequent likely weighting of the results towards people with mild TBI. Donnelly and colleagues' study [Citation36], however, shows a promising means of promoting relationships with others through participation in yoga activity and psychoeducation. The outcome of Tate and colleagues' [Citation37] PEPA intervention also shows promise in providing people with TBI an opportunity to develop social connections. However, it should be acknowledged that in this study interventions for “social” and “leisure” domains were independent of each other. Some leisure activities did not clearly involve interactions with others and frequency of participation was the outcome for this domain. As Rousseau et al. [Citation55] pointed out, quality of leisure is different to frequency of participation in leisure activity. Activities under the “social” domain involved interactions with others, and for some participants included recreation or leisure activity such as lawn bowls. This highlights the importance of considering domain overlap and individual versus group setting of proposed intervention goals and activities.

A further limitation was the concept of “social participation,” and its interchangeability with related terms such as “community integration”, and subsequent variety of tools used to measure this phenomenon. Some authors [Citation15,Citation32,Citation36] used the term “community integration” in the stated aim of the program. Donnelly et al. [Citation36] were the only authors to define this concept to include “relationships with others”, whereas others [Citation15] highlighted the importance of relationships on community integration. Some authors who used the term “community integration” isolated the “social participation” component embedded within a broader measure of community integration, such as the “social integration” subscale of the CIQ ([Citation15] or “social relationships” on the WHOQOL-BREF [Citation33]. For other studies where the relevant measure of “social participation” was embedded within a complete measure (for example line items within the LSS), it was not possible to isolate the relevant outcomes and this impeded interpretation of results for this review. In their SCED study, Tate et al. [Citation37] used standardised complete community integration measures as adjunct measures, but utilised individualised GAS goals across “social” and “leisure” domains as their primary measure. This individualised approach provides an opportunity to focus outcomes on person-specific goals and capture small, meaningful changes that may not be reliably evident through changes in standardised assessments scores. Given the individualised and multifactorial nature of social participation, employment of SCED may be a particularly effective means of systematically developing an evidence base to guide intervention in this domain [Citation3,Citation56].

The variability in the type and use of outcome measures compels researchers and clinicians to consider what might be the best tool to measure social participation. This process would be greatly assisted by a precise working definition of social participation. “Participation” defined as “involvement in a life situation” (ICF) differs from the definition of “social participation” used in this scoping review – that is, “involvement in activities that provide interactions with others” [Citation26,Citation27]. Further, although participating in recreation or leisure activity provides an opportunity to interact with others, it does not necessarily result in increased quality of interactions or meaningful connections being made. Any evaluation of the impact of an intervention targeting social participation would therefore need to consider both immediate change (e.g., number and type of opportunities for social interactions and enjoyment of the activity) and sustained change (e.g., building of friendships, development of confidence, increased self-efficacy, and development of sense of self). Improvements may then occur at a broader social participation level, such as becoming more active in the community and joining other groups.

Future research

Further research incorporating consumer involvement and robust methodological design and reliable, valid and personally meaningful ways of measuring social participation outcomes is clearly required to inform the development of interventions. Furthermore, longitudinal follow-up would assist in determining barriers and facilitators to sustained leisure participation, and how connections with others develop and are maintained over time. Given the restrictions on in-person leisure and social activity due to the global pandemic, future research may also include the use of technology to connect with others, including online groups or social media platforms.

Conclusion

The importance of ameliorating the negative impact of TBI on social participation in leisure and recreational activities is well-recognised in the literature, and interventions aimed at doing so are varied in their design, content and effectiveness. Progress in identifying clinically useful recommendations would be assisted by consensus on key terms (i.e., social participation and community integration) and subsequent agreement on a minimum set of relevant outcome measures of greatest utility and validity in the community. For example, the Centre for Excellence in Traumatic Brain Injury Psychosocial Rehabilitation has developed recommendations for outcome instruments to use in psychosocial research following moderate-severe TBI [Citation57]. Ideally, measures of social participation and community integration would enable the assessment of both immediate and sustained change when engaging in social activity. Monitoring progress and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions over time using both quantitative and qualitative methodological approaches is critical to the ultimate success of this endeavour. Despite the small number of studies and mixed quality of the evidence, this review has revealed clinically useful information to guide further development of interventions focussed on social participation in leisure or recreation after moderate-severe TBI.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (103.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, et al. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2018;1:1–18.

- Ponsford J, Sloan S, Snow P. Traumatic brain injury rehabilitation for everyday adaptive living. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Psychology Press; 2013.

- Douglas J. Loss of friendship following traumatic brain injury: a model grounded in the experience of adults with severe injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020;30(7):1277–1302. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2019.1574589.

- Fleming J, Braithwaite H, Gustafsson L, et al. Participation in leisure activities during brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2011;25(9):806–818. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.585508.

- Wise E, Mathews-Dalton C, Dikmen S, et al. Impact of traumatic brain injury on participation in leisure activities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(9):1357–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.009.

- Conneeley AL. Exploring vocation following brain injury: a qualitative enquiry. Social Care and Neurodisability. 2013;4(1):6–16. doi: 10.1108/20420911311302272.

- Macaden A, Chandler B, Chandler C, et al. Sustaining employment after vocational rehabilitation in acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(14):1140–1147. doi: 10.3109/09638280903311594.

- Levack W, Kayes N, Fadyl J. Experience of recovery and outcome following traumatic brain injury: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(12):986–999. doi: 10.3109/09638281003775394.

- Douglas J. Elizabeth usher memorial lecture: placing therapy in the context of the self and social connection. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2015;17(3):199–210. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2015.1016113.

- Douglas JM, Spellacy FJ. Correlates of depression in adults with severe traumatic brain injury and their carers. Brain Injury. 2000;14(1):71–88.

- Hoofien D, Gilboa A, Vaki E, et al. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) 10-20 years later: a comprehensive outcome study of psychiatric symptomatology, cognitive abilities and psychosocial functioning. Brain Injury. 2001;15(3):189–209.

- Osborn A, Mathias J, Fairweather-Schmidt A, et al. Traumatic brain injury and depression in a community-based sample: a cohort study across the adult life span. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33(1):62–72. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000311.

- Salas C, Casassus M, Rowlands L, et al. “Relating through sameness”: a qualitative study of friendship and social isolation in chronic traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2018;28(7):1161–1178. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2016.1247730.

- Shorland J, Douglas J. Understanding the role of communication in maintaining and forming friendships following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2010;24(4):569–580. doi: 10.3109/02699051003610441.

- Douglas J, Dyson M, Foreman P. Increasing leisure activity following severe traumatic brain injury: does it make a difference? Brain Impairment. 2006;7(2):107–118. doi: 10.1375/brim.7.2.107.

- Huebner R, Johnson K, Bennett C, et al. Community participation and quality of life outcomes after adult traumatic brain injury. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57(2):177–185. doi: 10.5014/ajot.57.2.177.

- Jacobsson L, Westerberg M, Malec J, et al. Sense of coherence and disability and the relationship with life satisfaction 6–15 years after traumatic brain injury in Northern Sweden. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2011;21(3):383–400. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2011.566711.

- McColl MA, Carlson P, Johnston J, et al. The definition of community integration: perspectives of people with brain injuries. Brain Inj. 1998;12(1):15–30. doi: 10.1080/026990598122827.

- Martin R, Levack W, Sinnott K. Life goals and social identity in people with severe acquired brain injury: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;20137(14):1234–1241. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.961653.

- World Health Organization. ICF: international classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Piskur B, Daniëls R, Jongmans M, et al. Participation and social participation: are they distinct concepts? Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(3):211–220. doi: 10.1177/0269215513499029.

- Levasseur M, Richard L, Gauvin L, et al. Inventory and analysis of definitions of social participation found in the aging literature: proposed taxonomy of social activities. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2141–2149. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.041.

- Winkler D, Unsworth C, Sloan S. Time use following a severe traumatic brain injury. J Occup Sci. 2005;12(2):69–81. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2005.9686550.

- Tate R, Wakim D, Genders M. A systematic review of the efficacy of community-based, leisure/social activity programmes for people with traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment. 2014;15(3):157–176. doi: 10.1017/BrImp.2014.28.

- Powell J, Rich T, Wise E. Effectiveness of occupation- and activity-based interventions to improve everyday activities and social participation for people with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70(3):7003180040p1–7003180040p9. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2016.020909.

- Kersey J, Terhorst L, Wu CY, et al. A scoping review of predictors of community integration following traumatic brain injury: a search for meaningful associations. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2019;34(4):E32–E41. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000442.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study quality assessment tools. 2019. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2022. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Tate R, Rosenkoetter U, Wakim D, et al. The risk-of-bias in N-of-1 trials (RoBiNT) scale: an expanded manual for the critical appraisal of single-case reports. Sydney: John Walsh Centre for Rehabilitation Research; 2015.

- Carbonneau H, Martineau É, Andre M, et al. Enhancing leisure experiences post traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. Brain Impairment. 2011;12(2):140–151. doi: 10.1375/brim.12.2.140.

- Mitchell EJ, Veitch C, Passey M. Efficacy of leisure intervention groups in rehabilitation of people with an acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(17):1474–1482. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.845259.

- Gibbs K, Wilkie L, Jarman J, et al. Riding the wave into wellbeing: a qualitative evaluation of surf therapy for individuals living with acquired brain injury. PLOS One. 2022;17(4):e0266388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266388.

- Fraas M, Balz MA. Expressive electronic journal writing: freedom of communication for survivors of acquired brain injury. J Psycholinguist Res. 2008;37(2):115–124. doi: 10.1007/s10936-007-9062-y.

- Donnelly KZ, Goldberg S, Fournier D. A qualitative study of LoveYourBrain yoga: a group-based yoga with psychoeducation intervention to facilitate community integration for people with traumatic brain injury and their caregivers. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(17):2482–2491. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1563638.

- Tate RL, Wakim D, Sigmundsdottir L, et al. Evaluating an intervention to increase meaningful activity after severe traumatic brain injury: a single-case experimental design with direct inter-subject and systematic replications. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020;30(4):641–672. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2018.1488746.

- Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, et al. The 2011 Oxford CEBM levels of evidence (Introductory Document). Oxford (UK): Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Available from: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence.

- Hadorn DC, Sorensen J, Holte J. Large-scale health outcomes evaluation: how should quality of life be measured? part II-questionnaire validation in a cohort of patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(5):619–629. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00186-t7730919.

- Willer B, Rosenthal M, Kreutzer JS, et al. Assessment of community integration following rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1993;8(2):75–87. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199308020-00009.

- World Health Organisation. WHOQOL-BREF introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment, field trial version. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1996.

- Katz M, Warren W. Katz adjustment scales relative report form manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1998.

- Ragheb M, Griffith C. The contribution of leisure participation and leisure satisfaction to life satisfaction of older persons. J Leis Res. 1982;14(4):295–306. doi: 10.1080/00222216.1982.11969527.

- Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):362–370. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101742.

- Malec J, Lezak M. Manual for the Mayo-Portland adaptability inventory (MPAI-4) for adults, children and adolescents. San Jose (CA): Center for Outcome Measurement in Brain Injury; 2008.

- McColl M, Davies D, Carlson P, et al. The community integration measure: development and preliminary validation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(4):429–434. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.22195.

- Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the lubben social network scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist. 2006;46(4):503–513. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.503.

- Drummond A, Parker C, Gladman J, et al. Development and validation of the Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire (NLQ). Clin Rehabil. 2001;15(6):647–656. doi: 10.1191/0269215501cr438oa.

- Levine B, Robertson IH, Clare L, et al. Rehabilitation of executive functioning: an experimental–clinical validation of goal management training. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2000;6(3):299–312. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700633052.

- Albrecht J, Barbour L, Abariga S, et al. Risk of depression after traumatic brain injury in a large national sample. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(2):300–307. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5608.

- Singh R, Mason S, Lecky F, et al. Prevalence of depression after TBI in a prospective cohort: the SHEFBIT study. Brain Inj. 2018;32(1):84–90. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1376756.

- Leeson R, Collins M, Douglas J. Finding goal focus with people with severe traumatic brain injury in a person-centered multi-component community connection program (M-ComConnect). Front Rehabil Sci. 2021;2:786445.

- McPherson K, Fadyl J, Theadom A, et al. Living life after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33(1):E44–E52. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000321.

- Pham M, Rajić A, Greig J, et al. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–385. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123.

- Rousseau J, Denis M-C, Dube M, et al. Activity, autonomy and psychological Well-Being of the elderly. Loisir Et Société. 1995;18(1):93–122. doi: 10.1080/07053436.1995.10715492.

- Perdices M, Tate R. Single-subject designs as a tool for evidence-based clinical practice: are they unrecognised and undervalued? Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2009;19(6):904–927. doi: 10.1080/09602010903040691.

- Honan C, McDonald S, Tate R, et al. Outcome instruments in moderate-to-Severe adult traumatic brain injury: recommendations for use in psychosocial research. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2019;29(6):896–916. 2019doi: 10.1080/09602011.2017.1339616.