Abstract

Purpose

Physical interventions during subacute rehabilitation have potential to improve functional recovery. This study explored the perspectives of children and adolescents with acquired brain injury (ABI) and their parents with respect to physical rehabilitation during the subacute phase.

Methods

Thirteen children and adolescents with ABI and their parents were included and interviewed using semi-structured interviews. Interview transcripts were analysed using inductive thematic analysis approach.

Results

Six themes were identified: 1) beliefs of physical rehabilitation, 2) content of physical rehabilitation, 3) tailored care, 4) impact of context, 5) communication and 6) transition. The importance of intensive physical practice was widely supported. The positive can-do mentality was emphasised to create an atmosphere of hope, meaning that every effort would be made to achieve maximum recovery. Intensive involvement of parents is considered essential during subacute rehabilitation including an open and mutual dialogue about the focus of rehabilitation, therapy goals and future participation in their own environment.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the need for an intensive rehabilitation approach, tailored to the individual’s needs. The perspectives of children and adolescents and their parents in our study contribute to a better understanding of factors that are important for optimal recovery through physical rehabilitation during the subacute phase.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Children with acquired brain injury and their parents indicate the potential and thus the importance of intensive physical practice to enhance optimal recovery.

Involvement of parents and the potential of their continuous presence during subacute rehabilitation may have a positive impact on the effect of rehabilitation efforts.

The positive can-do mentality of rehabilitation professionals creates an atmosphere of hope and is an important requisite to achieve maximum recovery.

Open dialogue between clinicians and the family is warranted about the focus of interventions.

Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) refers to a brain insult acquired after the first year of life and is the leading cause of death and disability among children and adolescents [Citation1,Citation2]. ABI may result from traumatic brain injuries (TBI) or nontraumatic brain injuries (nTBI) such as stroke and brain tumours [Citation3]. In children and adolescents, ABI is associated with acute and negative effects on physical, cognitive, social and emotional functioning [Citation4,Citation5]. After the acute phase in the hospital, children and adolescents with moderate to severe ABI may require multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes to treat the complex and multidimensional sequelae of ABI [Citation6]. Emphasis is initially given to physical rehabilitation, since changes in mobility are often most apparent during this subacute rehabilitation phase [Citation7–10].

Recently, a review [Citation11] revealed that the current body of evidence about content and effects of physical rehabilitation interventions in children and adolescents during the subacute rehabilitation phase is limited. Consequently, the optimal physical intervention characteristics and their effects on performance outcomes, including participation in daily life remain unclear. Nevertheless, the potential of intensive physical rehabilitation interventions during the subacute phase has been discussed for adult populations with emphasis on the understanding and identification of its effective ingredients [Citation12–14]. These ideas are now emerging for the paediatric population [Citation15]. Active collaboration between clinicians and families is essential in paediatric rehabilitation practice. Therefore, children and adolescents with ABI and their parents have unique experiential knowledge which could contribute to a better understanding of the essential ingredients to optimize current physical rehabilitation practice [Citation16,Citation17].

Qualitative research is a useful method for obtaining patients’ perspectives as the findings can improve our understanding of factors determining the rehabilitation goals, processes and outcomes relevant to the child and family [Citation18]. While a few qualitative studies have been published about the perspectives of young people with ABI and their parents regarding inpatient rehabilitation [Citation17,Citation19–21], none of them have focused on physical rehabilitation during the subacute phase. Therefore, the objective of this study is to identify and synthesise the perspectives of children and adolescents with ABI and their parents with respect to physical rehabilitation during the subacute phase.

Methods

Study design

A qualitative, exploratory study with semi-structured interviews was conducted using an inductive thematic analysis approach [Citation22]. The research team consisted of researchers and healthcare professionals with expertise in paediatric physical therapy (CGM, OV, RE), neuropsychology (IR) and paediatric rehabilitation medicine (JWG). An expert in qualitative research methodology was frequently consulted to ensure the quality of the process and the results. The Ethics Research Committee of the Hoogstraat Rehabilitation Utrecht approved commencement of the study (file reference: rvb/JWGM/cl).

Participants

All participants were recruited from the local database of The Hoogstraat Rehabilitation, Utrecht The Netherlands. Children and adolescents were included if 1) they were diagnosed with moderate to severe ABI, 2) they had an age between 6-18 years during their rehabilitation process, 3) their rehabilitation treatment was finished between January 2019 and January 2022, indicating there was a recall period of no longer than a maximum three years. Exclusion criteria were 1) children, adolescents or parents who were not able to understand or converse in Dutch, 2) their rehabilitation process was primarily focused on cognitive or psychological problems or 3) their rehabilitation process was prematurely ended due to a medical complication. Based on previous qualitative studies regarding perspectives of children with ABI and their parents, the sample size was estimated between 10-15 children and adolescents (and their parents) to reach data saturation [Citation19,Citation23,Citation24]. Therefore, 20 eligible families were informed by email about the study and after consent was given for initial contact further information about the study was sent. A purposive sampling method ensured that the sample comprised a diverse group of participants with representation in age, injury types and severity levels. Participation in the study was voluntary and informed consent was permitted by children (>11 years old) and their parents.

Procedure

Participants received a digital brochure with a link to a short video of the rehabilitation department to recall memories of their own rehabilitation process. Subsequently, the interview was planned in person at the Hoogstraat Rehabilitation Utrecht, The Netherlands or online via Microsoft Teams®, depending on the preference of the participants. Children and adolescents were allowed to choose whether to have this interview individually or in the presence of their parents.

The interview guide was developed based on existing literature and expert knowledge, in consultation with a representative of the patient organisation (supplemental appendix 1). A pilot interview was conducted with a random child and its parent at our inpatient rehabilitation department to ensure the feasibility of the interview guide. Although the interviews were guided by pre-set topics, participants were allowed and encouraged to address topics and issues which they felt deserved to receive attention. Individual semi-structured interviews were independently conducted by graduate students (ES, DD) in the Paediatric Physiotherapy Master Programme in Utrecht who had no clinical or professional link to the participants. An independent researcher supervised the first three child interviews and three parent interviews to ensure in-depth discussions of the topics and the consistency between the interviews. Relevant issues were discussed within the research group during peer debriefings to ensure data saturation on all topics through the remaining interviews. If data saturation, defined as the point which no new information was emerging from the data collection process, on all topics was identified, one final interview was held to ensure completeness [Citation25]. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission and transcribed verbatim with Amberscript®. Identifiable details were anonymised and a unique numeric code was assigned to each interview transcript.

Data analysis

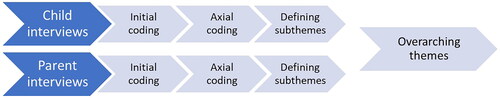

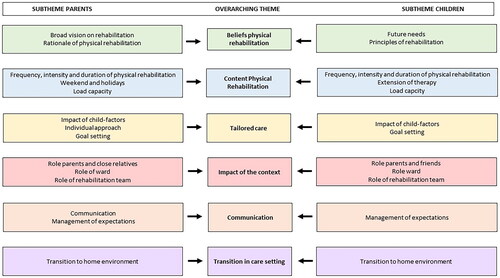

Inductive, data driven, analysis [Citation26] was performed separately for the child interviews (ES) and parent interviews (DD) in order to be able to distinguish between the perspectives of children and parents (). The software Atlas.ti® was used. The first phase involved the production of initial codes from the data in the form of key descriptive phrases for patterns within the data [Citation26]. The first three child interviews and the first three parent interviews were coded independently (ES/DD and CGM). After each interview, disagreements were resolved by consensus between the two researchers. Based on the high degree of similarity in coding between the researchers, the remaining interviews were initially coded by ES/DD and checked by CGM. All disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. The second phase involved axial coding by CGM in which the initial codes with comparable meaning were clustered into categories, and subsequently grouped into tentative subthemes. All tentative subthemes were discussed and considered whether they accurately reflected the data set overall in a team meeting (CGM, ES, DD, OV and IR). Subsequently, the subthemes were summarized and presented schematically to provide insight into their mutual relationships. By this stage, we were able to see whether themes reflected parental and/or child perspectives. Because of the similarities between the subthemes of child interviews and parent interviews, overarching main themes were defined through discussions until agreement was reached. Member checking was employed by providing a descriptive summary of the results to the participants by email. The participants were asked if they could agree with the content of the summary and provide additional feedback by email. The final phase involved the full team writing up the findings to reflect our interpretation of the data and the extraction of relevant quotations.

Results

Participants

Thirteen of twenty invited families agreed to participate in the study, resulting in a total of twenty-six interviews with respectively 13 children/adolescents and 13 parents between March-May 2022. Characteristics of the participants are summarised in .

Table 1. Characteristics of participants.

Themes

Six main themes with associated subthemes () were identified from the data analysis: 1) beliefs of physical rehabilitation, 2) content physical rehabilitation, 3) tailored care, 4) impact of context, 5) communication and 6) transition.

Figure 2. Overview of themes and subthemes.

Theme 1: beliefs of physical rehabilitation

All participants emphasised that physical rehabilitation should focus on optimal recovery and that everything should be put into action for this. Several parents mentioned disagreements with the rehabilitation team about the focus of rehabilitation. These parents expressed their need for recovery focused interventions, contrary to the experience they have had of a more or less fixed focus on compensation strategies.

Here you learn how to deal with your disability. That’s kind of the approach, but we didn’t want to deal with a disability. We want results. (Father of a 6-year-old boy)

[emotional] You focus on recovery as best as possible […], it’s for the rest of your life. But for example with the occupational therapist, they started directly to teach how to tie shoelaces with one hand. So we immediately thought: ‘Uh what? He has two hands, doesn’t he?’ We totally disagreed (…). It’s fine if someone is independent, perfect. But it was actually a waste for his recovery and I’m still really disappointed about that. (Mother of 15-year-old boy)

Many parents expressed a need for a broader vision on rehabilitation, beyond the expertise and possibilities of the rehabilitation center the child is admitted to. This includes alternative treatment options and the involvement of other experts if necessary. The overarching feeling that emerged in the interviews was a sense of hope. Both parents and children expressed the need for a positive approach from the rehabilitation team that enables them to stay hopeful throughout the rehabilitation phase resulting in a firm belief that every effort was made to achieve the maximum.

I think it’s all a little conservative. Sometimes I missed a kind of more holistic, experimental approach. (…) I would be more open for treatment methods or outside knowledge. (Mother of 13-year-old girl)

If you are constantly reminded that it’s uncertain what [the treatment] is going to do and how much he will recover… that is not what you want to hear as parents. You just want a positive approach, which gives you a little hope and that is what you convey to your child. (Mother of 6-year-old boy)

My therapists were really great, they were involved with both me and my parents and they created a very good atmosphere. They helped me to get the most out of myself. (17-year old boy)

Theme 2: content of physical rehabilitation

Physical rehabilitation was seen as more than the physical therapy sessions: all daily activities (for example dressing, walking, playing games, going outside) may contribute to recovery.

Really, it was all therapy. So everything that you did had a therapeutic function. Walking, going somewhere even if it was in a wheelchair, or giving her something so she had to use her arm. Everything was therapy. (Father of 10-year-old girl)

The importance of intensive physical practice was widely supported by parents and children. However, several adolescents and parents indicated that the rehabilitation programme was not intensive enough and expressed a need for more frequent therapies and physical activities during subacute rehabilitation.

I always had that thought of ‘Yes, I just want to keep going and now I’m just sitting there wasting my time in my room. (13-year-old girl)

First, she got half an hour [of therapy] a day, then twice a day and that didn’t go fast enough for us. So in our opinion, we thought that she could be more physically challenged instead of so little amount of therapy sessions. (Mother of 13-year-old girl)

In addition, parents and children have experienced limited opportunities for therapeutic activities during weekends and holidays. This is perceived as a negative aspect because there is no (supervised) physical training which caused boredom. Besides, parents and children referred to the principle ‘stagnation means decline’, indicating the need of continuing physical activities through weekends and holidays. Children have identified ideas for involving siblings and friends on weekends to increase therapeutic activities with them.

Certainly in the beginning, because then you see so much progress and then you’re like: ‘Well, now it stops at the weekend…’. Friday afternoon it is all done, and we will continue Monday morning. But we want to continue [practicing] with him, he is showing so much progress. (Father of 9-year-old boy)

Especially if, for example, friends came and visited. I just wanted to do things with them, and now I see that those things have made me stronger because they pushed me ‘Oh come on, let’s do this, let’s do that. In that respect there wasn’t much here. (15-year-old boy)

Theme 3: tailored care

Parents stressed the importance of tailored care. Each child, their family and the consequences of the brain injury are unique. Some children have recovered very smoothly, others had to deal with various complications and required more time to recover. The rehabilitation team should take these unique personal factors and circumstances into account.

They really listened to what I thought was most important to teach [child’s name] again. Look, for him it wasn’t just 30 minutes of therapy, he sometimes needed much more time than another child with a brain tumor. And they ensured that [therapy] was really well aligned. (Mother of 7-year-old boy)

And not running a predetermined therapy programme, but looking what he could handle on that day and at that moment. Sometimes he could handle less than we actually thought. And then they adjusted. That is customisation. (Father of 9-year-old boy)

Goal setting was seen as helpful to tailor physical rehabilitation to individual needs and to monitor the progression during the rehabilitation process. Parents and children have experienced limited flexibility regarding tailored therapy programmes, especially when there was a need for an increased amount of therapy sessions.

Sometimes the therapy session passed so quickly and then I thought: ‘Yes, I actually want to continue longer’, but then it was the next person’s turn. (10-year old girl)

Well, there were possibilities to skip a therapy session, but what I can remember there were limited possibilities to easily increase the frequency of therapy sessions at another time of the day. (Mother of 13-year-old girl)

Theme 4: impact of context

Many interviews indicated that rehabilitation after ABI is an intense process for both the child and their family. The key finding is that intensive involvement of parents is essential for optimal recovery. Parents indicated that their continuous presence resulted in individual attention for their child to practice intensively and in frequent communication with the rehabilitation professionals.

But if I may give one piece of advice to the people it happens to: stay with your child! I’m convinced, based on what we have seen and experienced, that it is really the best for the recovery of your child. And that makes sense, because you give more attention and care to your child and can more easily respond to things that you would otherwise not think about when you are not there. (Father of 10-year-old girl)

In addition, the atmosphere at the ward was mentioned unanimously as an important factor during rehabilitation together with the expertise, flexibility and ‘can-do-mentality’ of the rehabilitation team. A committed therapist with a curious attitude and positive contact with the child was seen as conditional for recovery.

That enormous positive can-do mentality was actually essential. No matter how hopeless things may look, they remain optimistic and continue to see it from the bright side. And I think that is important. So they actually made it a kind of party for each child. (Father of 10-year-old girl)

When he saw his physiotherapist, I noticed that there was a connection [between the two]. He had such a good feeling with his therapist, I saw it happening. I was like, ‘Wow, he’s able to achieve a lot with my child’. And when I see what they all achieved (…) I actually had my child back again, and that is the greatest thing you as therapists can give me as a parent. (Mother of 7-year-old boy)

Finally, children and adolescents indicated their need for involvement of friends and peers during their rehabilitation process.

My optimal rehabilitation? Well, girlfriends, nice therapists, a lot of therapy. (…) I think just a fun and relaxed atmosphere is very important for a rehabilitation process. (13-year-old girl)

Theme 5: communication

Frequent consultation and short lines of communication were mentioned as key elements in this theme. Although several parents expressed their appreciation for the pleasant communication, some parents expressed frustrations about the lack of a mutual dialog about the treatment programme. Overall, parents stressed the importance of the involvement of the child (according to ability), parents and rehabilitation professionals in open dialog to discuss rehabilitation goals and the (suggested) approach.

If we didn’t like something or something didn’t work the way we wanted, we just talked about it and I always have liked that. I think that is just very important. You have to keep talking to each other because otherwise it won’t work. (Mother of 7- year-old boy)

So it would be good to first have a consultation here and there with: ‘Hey, what do you actually want’? Not one fixed plan, but listen to what that person wants. And even though the therapist knows in the back of his mind ‘he will never succeed’, do it anyway! Go for it, and don’t give up in advance. (Mother of 15-year-old boy)

Several adolescents indicated that the strict rules on the paediatric ward (e.g. going out in the evening) complicated their possibilities to participate in the environment of the rehabilitation center.

Yes, I understand that there are some rules, but well I don’t know. I think more could be allowed if you want to go out with family and friends… just to stimulate the reintegration. (18-year-old girl)

Theme 6: transition in care setting

Parents have various experiences regarding transition from hospital to the rehabilitation center and from rehabilitation center to their own environment. The awareness by the team of the child’s life before and after rehabilitation was indicated as important. Rehabilitation effort should align with meaningful activities of the child in their own environment and possible barriers should be identified at an early stage.

It is like being released from a fishbowl into the big sea, you know? Everything feels comfortable in the rehabilitation center, you know everyone and there is a lot of support. And then suddenly you have to do your own things and you have to go to school. And I had once learned how to roll a sidewalk in therapy, but when I drive down my own street, my arms are already tired so I can no longer roll. It really stops with independence. (15-year-old boy)

I think you get the tools from your therapist, like a sort of start, but eventually the reintegration process is almost more rehabiltiation than you actually did in the therapy sessions. (16-year-old girl)

In addition, parents stressed the importance of a safety net and a fallback after the rehabilitation process.

You know what? You have a completely different child who is functioning differently than before. On every domain. And yes, then you have to do it without help and that’s just very tough. Yes, I think that the rehabilitation process ended too abruptly. It would have been better to take more time to phase out. (Mother of 6-year old boy)

Discussion

Our qualitative study captured the perspectives of children and adolescents with ABI and their parents on physical rehabilitation during the subacute phase and identified various issues that deserve attention by rehabilitation professionals. The interviews in our study revealed that subacute rehabilitation is a new and overwhelming experience for children and their parents in which hope and gratitude as well as frustrations and sadness come together. Most parents are impressed with the extent to which their child has recovered after ABI, but also see opportunities to optimise physical rehabilitation. The feedback from experts by experience is essential as they are able to quantify and pinpoint key factors to inform future improvements in clinical care [Citation27].

The stories in this study reveal the huge impact of childhood brain injury on children’s functioning in daily life and their future. The participants emphasise the need to explore all therapeutic possibilities to achieve maximal physical recovery and to optimise participation in their own environment. Children and adolescents with ABI and their parents indicate the importance of optimally exploiting the window of opportunity during the subacute rehabilitation phase. In general, we have seen differences in perspectives of parents, children and adolescents over time. Some parents express a need for restorative interventions during the subacute phase, with the focus shifting more towards independence and transition to the own home environment after this phase. However, some parents indicated the current focus of subacute rehabilitation on maximum independence from the start, if necessary, by means of compensation strategies. This finding highlights the need for discussions between the family and the rehabilitation team about the focus of rehabilitation. The considerations to an optimal balance between restorative and compensatory interventions in clinical practice have been discussed in the literature but remains a challenge in clinical practice [Citation28,Citation29]. Based on the perspectives in our study, we stress the importance of an open dialogue between clinicians and the family about the focus of interventions, based on the clinical presentation and developmental needs of the child. In addition, our findings show the relevance of the alignment of physical rehabilitation with future participation in their own environment. Awareness of transition to home at an early stage of recovery may help families to better understand the conditions needed to facilitate optimal reintegration in a meaningful context. Adequate follow-up and access to on-going rehabilitation and other support services after discharge is required [Citation23].

Participants unanimously stressed the potential and thus the importance of intensive physical practice to enhance optimal recovery. This finding is in line with the increasing understanding of recovery mechanisms after ABI, such as the principles of experience-dependent neuroplasticity [Citation30–34]. Neuroplasticity is considered as the mechanism by which the damaged brain encodes experience and (re)learns behaviours in response to rehabilitation [Citation30]. Dosage of rehabilitation interventions appears to be an important component of the principles of experience-dependent neuroplasticity [Citation29,Citation30]. Several studies in adults support increased intensity of practice with better outcomes in terms of functioning and participation in daily life after ABI [Citation14,Citation35–37]. However, the translation to physical rehabilitation practice in children and adolescents with ABI has not yet been made and thus the optimal dosage of practice remains unclear. Nevertheless, the awareness of the potential of increased practice may help clinicians during the clinical reasoning process to design a physical rehabilitation programme. In line with the parents in our study, this supports tailored physical interventions aligned with the child or adolescent’s individual needs [Citation24,Citation38].

Current rehabilitation practice in De Hoogstraat Rehabilitation, The Netherlands, does not include weekend therapies. Several participants expressed a need for more therapeutic activities during weekends and holidays with the perspective that rehabilitation is not a nine-to-five approach. This is in line with current literature in adult neurorehabilitation in which the potential of a continuity of weekend therapy is discussed [Citation39–41]. Although the ‘weekend-feeling’ was seen as important, the ideas of our participants are mainly in line with a 24/7 approach during subacute rehabilitation with adequate balance between activity and rest [Citation11,Citation42]. This is reflected by other participants’ experiences of maximising the opportunities for physical practice by extending therapeutic activities into meaningful activities throughout the week, combined with adequate rest and sleep.

Physical rehabilitation in ABI during the subacute recovery phase is an approach requiring an interdisciplinary team effort with contribution of various allied health professionals depending on the goals. Moreover, interdisciplinary collaboration should be extended to parents and their social context to create a comprehensive system approach [Citation43]. Our findings emphasise the involvement of parents and the potential of continuous presence during subacute rehabilitation on the effect of rehabilitation efforts. This is supported by studies that linked increased family collaboration in the rehabilitation process to better outcomes for individuals after brain injury [Citation44–46]. The importance of family involvement and family-centered care are widely accepted in paediatric rehabilitation [Citation17,Citation47]. Moreover, a family-directed approach to brain injury (FAB) model has been developed to provide a theoretical framework for educating and training family members of adults with ABI, based on principles of hope, family expertise, education building and family-directed interventions [Citation48]. The reflection of the parents in our study on the importance of hope aligns with the prominent position of hope in the FAB-model. Therefore, the FAB-model and specific recommendations made by Fisher et al. 2019 [Citation48] could help clinicians with the application in clinical practice. As this requires specific skills and attitudes of each rehabilitation professional, we believe it is essential that the entire rehabilitation team is well equipped for this [Citation17]. Specific training in professional-client rapport with empathy and interpersonal communication skills could be helpful to ensure collaborative partnership with families.

Study limitations

While our study provides new insights into perspectives of children and adolescents with ABI and their parents on physical rehabilitation during subacute phase, there are several limitations that should be considered. Participants were recruited from one single-site rehabilitation center which may limit the transferability of the findings. Although we sought to include a varied sample of participants, those who participated may have been influenced by their own need to express their positive or negative experience with their rehabilitation process. In addition, most recruited participants have had a treatment relationship with the principle investigator which may have affected whether they would participate or not (selection bias).

Despite our intervention (digital brochure with a video of the rehabilitation department) to minimise recall bias, the wide range of time since injury may have affected the ability to recall memories. Besides, this range of time has also allowed for the rehabilitation approach to change in the intervening period, which could have influenced the responses of the participants. Although data saturation was reached, the quality of the data from the individual interviews may have been impacted by the method of conducting the interview as in-person techniques may generate richer data than online techniques [Citation49]. The interviews with younger children (<12 years old) resulted in limited rich data, indicating that semi-structured interviews were not the most adequate method in this younger population. Future research could consider method-triangulation with visual or active applications [Citation50].

Conclusions

This qualitative study has filled a gap in knowledge surrounding the experiences of children and adolescents with ABI and their parents and contribute to a better understanding of factors that are important for optimal recovery through physical rehabilitation during the subacute phase. The perspectives of our participants revealed the need for an intensive physical rehabilitation approach, tailored to the individual needs of the child and the parents during subacute rehabilitation. Children, adolescents and parents should be structurally involved in the development and execution of a treatment plan in the subacute phase of rehabilitation. Families should be viewed as active team members in an interdisciplinary team collaboration to achieve optimal results of physical rehabilitation interventions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the participants who shared their experiences with us. We thank Camille Biemans for supervising the first interviews and support with transcription of interviews, Floryt van Wesel (expert in qualitative research) for assistance in research methodology and Fara Verhagen (representative of patient organisation Hersenletsel.nl) for her assistance with the topic guide.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chevignard M, Toure H, Brugel DG, et al. A comprehensive model of care for rehabilitation of children with acquired brain injuries. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36(1):31–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00949.x.

- Bruns J, Jr., Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia. 2003;44(s10):2–10. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.44.s10.3.x.

- Varela-Donoso E, Damjan H, Munoz-Lasa S, et al. Role of the physical and rehabilitation medicine specialist regarding of children and adolescents with acquired brain injury. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2013;49(2):213–221.

- Bedell GM. Functional outcomes of school-age children with acquired brain injuries at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2008;22(4):313–324. doi:10.1080/02699050801978948.

- Anderson V, Catroppa C, Morse S, et al. Functional plasticity or vulnerability after early brain injury? Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1374–1382. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1728.

- Reuter-Rice K, Eads JK, Berndt S, et al. The initiation of rehabilitation therapies and observed outcomes in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Rehabil Nurs. 2018;43(6):327–334. doi:10.1097/rnj.0000000000000116.

- Galvin J, Lim BC, Steer K, et al. Predictors of functional ability of Australian children with acquired brain injury following inpatient rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2010;24(7–8):1008–1016. doi:10.3109/02699052.2010.489793.

- Dumas HM, Haley SM, Carey TM, et al. The relationship between functional mobility and the intensity of physical therapy intervention in children with traumatic brain injury. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2004;16(3):157–164. doi:10.1097/01.PEP.0000136004.69289.01.

- Dumas HM, Haley SM, Ludlow LH, et al. Recovery of ambulation during inpatient rehabilitation: physical therapist prognosis for children and adolescents with traumatic brain injury. Phys Ther. 2004;84(3):232–242.

- Ryan JL, Zhou C, Levac DE, et al. Gross motor change after inpatient rehabilitation for children with acquired brain injury: a 10-year retrospective review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2023; 65:953–960. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.15471.

- Gmelig Meyling C, Verschuren O, Rentinck IR, et al. Physical rehabilitation interventions in children with acquired brain injury: a scoping review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64(1):40–48. doi:10.1111/dmcn.14997.

- Kwakkel G. Impact of intensity of practice after stroke: issues for consideration. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(13–14):823–830. doi:10.1080/09638280500534861.

- Langhorne P, Bernhardt J, Kwakkel G. Stroke rehabilitation. Lancet. 2011;377(9778):1693–1702. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60325-5.

- Konigs M, Beurskens EA, Snoep L, et al. Effects of timing and intensity of neurorehabilitation on functional outcome After traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(6):1149–1159 e1. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2018.01.013.

- Forsyth R, Hamilton C, Ingram M, et al. Demonstration of functional rehabilitation treatment effects in children and young people after severe acquired brain injury. Dev Neurorehabil. 2022;25(4):239–245. doi:10.1080/17518423.2021.1964631.

- Smits DW, van Meeteren K, Klem M, et al. Designing a tool to support patient and public involvement in research projects: the involvement matrix. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6(1):30. doi:10.1186/s40900-020-00188-4.

- Jenkin T, Anderson VA, D’Cruz K, et al. Family-centred service in paediatric acquired brain injury rehabilitation: bridging the gaps. Front Rehabil Sci. 2022;3:1085967.

- Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-based medicine working group. JAMA. 2000;284(4):478–482. doi:10.1001/jama.284.4.478.

- Lemon J, Cooper J, Defres S, et al. Understanding parental perspectives on outcomes following paediatric encephalitis: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0220042. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220042.

- Fleming J, Sampson J, Cornwell P, et al. Brain injury rehabilitation: the lived experience of inpatients and their family caregivers. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19(2):184–193. doi:10.3109/11038128.2011.611531.

- Metzner G, Hohn C, Waldeck E, et al. Rehabilitation-related treatment beliefs in adolescents: a qualitative study. Child Care Health Dev. 2022;48(2):239–249. doi:10.1111/cch.12922.

- Boeije H. Analysis in qualitative research. London (UK): Sage Publications; 2009.

- Abrahamson V, Jensen J, Springett K, et al. Experiences of patients with traumatic brain injury and their carers during transition from in-patient rehabilitation to the community: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(17):1683–1694. doi:10.1080/09638288.2016.1211755.

- Lundine JP, Utz M, Jacob V, et al. Putting the person in person-centered care: stakeholder experiences in pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2019;12(1):21–35. doi:10.3233/PRM-180568.

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893–1907. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Kneebone II, Hull SL, McGurk R, et al. Reliability and validity of the neurorehabilitation experience questionnaire for inpatients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26(7):834–841. doi:10.1177/1545968311431962.

- Forsyth R, Basu A. The promotion of recovery through rehabilitation after acquired brain injury in children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(1):16–22. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12575.

- Hylin MJ, Kerr AL, Holden R. Understanding the mechanisms of recovery and/or compensation following injury. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:7125057–7125012. doi:10.1155/2017/7125057.

- Kleim JA, Jones TA. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51(1):S225–S39. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2008/018).

- Overman JJ, Carmichael ST. Plasticity in the injured brain: more than molecules matter. Neuroscientist. 2014;20(1):15–28. doi:10.1177/1073858413491146.

- Szulc-Lerch KU, Timmons BW, Bouffet E, et al. Repairing the brain with physical exercise: cortical thickness and brain volume increases in long-term pediatric brain tumor survivors in response to a structured exercise intervention. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;18:972–985. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2018.02.021.

- Voss MW, Vivar C, Kramer AF, et al. Bridging animal and human models of exercise-induced brain plasticity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(10):525–544. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2013.08.001.

- Caleo M. Rehabilitation and plasticity following stroke: insights from rodent models. Neuroscience. 2015;311:180–194. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.10.029.

- French B, Thomas LH, Coupe J, et al. Repetitive task training for improving functional ability after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11(11):Cd006073.

- Kwakkel G, van Peppen R, Wagenaar RC, et al. Effects of augmented exercise therapy time after stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2004;35(11):2529–2539. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000143153.76460.7d.

- Turner-Stokes L, Pick A, Nair A, et al. Multi-disciplinary rehabilitation for acquired brain injury in adults of working age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(12):Cd004170.

- Yun D, Choi J. Person-centered rehabilitation care and outcomes: a systematic literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;93:74–83. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.012.

- English C, Shields N, Brusco NK, et al. Additional weekend therapy may reduce length of rehabilitation stay after stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Physiother. 2016;62(3):124–129. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2016.05.015.

- de Jong AU, Smith M, Callisaya ML, et al. Sedentary time and physical activity patterns of stroke survivors during the inpatient rehabilitation week. Int J Rehabil Res. 2021;44(2):131–137. doi:10.1097/MRR.0000000000000461.

- Otterman NM, van der Wees PJ, Bernhardt J, et al. Physical therapists’ guideline adherence on early mobilization and intensity of practice at dutch acute stroke units: a country-wide survey. Stroke. 2012;43(9):2395–2401. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660092.

- Verschuren O, Hulst RY, Voorman J, et al. 24-hour activity for children with cerebral palsy: a clinical practice guide. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2021;63(1):54–59. doi:10.1111/dmcn.14654.

- Gmelig Meyling C, Verschuren O, Rentinck ICM, et al. Development of expert consensus to guide physical rehabilitation in children and adolescents with acquired brain injury during the subacute phase. J Rehabil Med. 2023;55:jrm12303. doi:10.2340/jrm.v55.12303.

- Sander AM, Caroselli JS, High WM, Jr., et al. Relationship of family functioning to progress in a post-acute rehabilitation programme following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2002;16(8):649–657. doi:10.1080/02699050210128889.

- Sander AM, Maestas KL, Sherer M, et al. Relationship of caregiver and family functioning to participation outcomes after postacute rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury: a multicenter investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(5):842–848. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.11.031.

- Macaden AS, Chandler BJ, Chandler C, et al. Sustaining employment after vocational rehabilitation in acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(14):1140–1147. doi:10.3109/09638280903311594.

- Smith KA, Samuels AE. A scoping review of parental roles in rehabilitation interventions for children with developmental delay, disability, or long-term health condition. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;111:103887. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103887.

- Fisher A, Bellon M, Lawn S, et al. Family-directed approach to brain injury (FAB) model: a preliminary framework to guide family-directed intervention for individuals with brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(7):854–860. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1407966.

- Guest G, Namey E, O’Regan A, et al. Comparing interview and focus group data collected in person and online. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. (PCORI). Washington (DC); 2020. Available from: doi: 10.25302/05.2020.ME.1403117064.

- Mah K, Gladstone B, King G, et al. Researching experiences of childhood brain injury: co-constructing knowledge with children through arts-based research methods. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(20):2967–2976. doi:10.1080/09638288.2019.1574916.