Abstract

Purpose: To systematically review the research relating to views and experiences of people with disability eating out in cafés, restaurants, and other settings; and identify factors that impede or enhance accessibility of eating out experiences, inform future inclusive research, and guide policy development.

Materials and Methods: This study involved systematic search and review procedures with qualitative metasynthesis of the barriers to and facilitators for participation and inclusion in eating/dining-out activities. In total, 36 studies were included.

Results: Most studies reviewed related to people with physical or sensory disability eating out, with few studies examining the dining experiences of adults with intellectual or developmental disability, swallowing disability, or communication disability. People with disability encountered negative attitudes and problems with physical and communicative access to the venue. Staff lacked knowledge of disability. Improvements in the design of dining spaces, consultation with the disability community, and staff training are needed.

Conclusion: People with disability may need support for inclusion in eating out activities, as they encounter a range of barriers to eating out. Further research within and across both a wide range of populations with disability and eating out settings could guide policy and practice and help develop training for hospitality staff.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Some people with disability require support for increased self-determination and self-advocacy to access eating out experiences satisfactorily.

Goals and strategies to increase access and participation in eating out activities for people with disability should include attention to the environment and hospitality venues and to staff training.

Rehabilitation professionals have a role in training hospitality staff about disability access and inclusion in eating out activities.

To enhance community inclusion and participation, rehabilitation professionals could focus more on the skills and strategies needed for people with disability to participate in eating out activities.

Rehabilitation professionals could implement a range of facilitators that might strengthen participation in eating out activities for people with disability.

Introduction

Sharing a meal with friends and family is an important part of community life. Indeed, the social significance of sharing a meal, or commensality [Citation1], is one way of informing how a person becomes a cultural and social member of society. Meal sharing is connected to our identity as human beings [Citation2–4]. Thus, eating out (also known as “dining out”) with others is an important activity in both our social and working lives and helps people within organisations and teams to bond [Citation5]. A restaurant, café or other hospitality venue provides a “consumption space” deeply attached to “symbolic meanings, where several rituals associated with social and cultural life take place” [Citation6, p.722]. Hospitality venues provide a place for eating out, and people with disability are likely to need or want to eat out and join this cultural “consumption space”. However, diverse populations, including people with disability, may be denied this experience due to a range of barriers that prevent them from engaging in eating out activities.

Cipriano-Crespo et al. [Citation4] suggested that acknowledging people’s diversity fosters a richness in society and allows recognition that diversity is a natural dimension of the human condition. All people can be considered functionally diverse. However, many people with disability, who may be perceived as different because of their eating practices or ability to access venues or services, may experience a sense of social isolation and ultimately loneliness if unable to participate in the same eating out activities as others. In fact, Cipriano-Crespo et al. [Citation4] noted that many people with disability may choose to isolate themselves from the social activity of sharing a meal because of feelings of stigma and self-consciousness. A range of difficulties, including access problems, communication problems and problems with eating and drinking eating out with family, friends, or colleagues, particularly in a public place, may cause conflict and fear rather than social pleasure and feelings of connection [Citation7].

Social isolation and a lack of community engagement can extend beyond the individual with disability to others in their family, social, and work circles. Acts such as the Disability Discrimination Act, 1992 in Australia [Citation8] and the Americans with Disability Act, 1990, 2008 [Citation9] declare that legally the associates of people with disability can be deemed to be discriminated against in the same way as the person with disability if the family’s social participation in eating out is impaired [Citation10]. The higher the level of the person with distality’s support needs, the greater the potential impact on the participation and inclusion of others in activities such as eating out. A lack of availability of supports, including physical and financial support, often limits social activities and participation for the entire family [Citation10]. Further to this, the expectations for social engagement are often influenced by previous experience in a hospitality environment. Davey et al. [Citation10] noted that “parents’ choice of family activities and the belief that these activities could influence the quality, enjoyment and satisfaction derived from family social participation were shaped by past experiences and perceived benefits of participation” (p. 2264). The authors noted that social connections were central to the success of any experience, and significant support might be required particularly in a public space.

This systematic review focuses on people with disability and their eating out experiences in hospitality services and settings. The theoretical foundation of the review draws upon the WHO International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health [Citation11] and the social-relational model of disability [Citation12]. The ICF is a bio-psycho-social model of disability recognising that a disability is not defined according to a diagnosis of a health condition but results from the interaction of several factors, including the person’s health condition, the person’s impairments and limitations, the activities and participation, and a wide range of environmental and personal factors. Within the ICF, not only the individual but also factors in their environment interact to form both barriers to and facilitators for their participation and inclusion in activities. In the context of this review, participation refers to a person with disability taking part in eating out activities, and inclusion relates to doing so in the same ways and with the same options as other people.

The social model of disability developed out of the 1970s disabled people’s movement and framed the approaches taken by disability advocacy organisations. A social-relational model of disability underpins the United Nations (2006) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [Citation11,Citation13]. The Convention was heralded as a global approach to addressing human rights abuses of people with disability and improving their social participation [Citation14]. As an example, Article 30 protects “participation in cultural life, recreation, leisure and sport” including cultural, hospitality and tourism venues where food consumption forms part of the cultural experience. Many nations have their own anti-discrimination or disability discrimination legislation through which the rights of people with disability are safeguarded. Despite this legislation, numerous studies have identified the direct and indirect discrimination that people with disabilities face in their everyday lives, including in restaurants, cafés, and hospitality venues (e.g. [Citation15–18]).

To date, there is no systematic review of the research relating to eating out with a disability, drawing together knowledge across diverse populations of people with disability in different hospitality settings, identifying: how people with disability have been included in research to date; gaps in knowledge; and implications for rehabilitation, future research, and policy. Thus, little is known about the issues related to eating out or the impacts of eating out activities on a range of groups, including hospitality staff. This study systematically reviewed the body of research at the intersection of disability and eating out activities. The aim of the review was to identify strategies to improve inclusion, identify gaps in knowledge, suggest directions for future research, and inform policy and practice for all stakeholders. Specifically, this review aimed to answer the following questions from the existing research:

What groups of people with disability and food hospitality venues are included in research that examines disability access and inclusion in cafés and restaurants or other eating out venues?

What are the views and experiences of people with disability and their family members or support workers, and hospitality staff, about disability access and inclusion in cafés, restaurants, and other eating out settings?

What limits, enables, or facilitates the inclusion and participation of people with disability in cafés, restaurants, and other hospitality venues?

What are the directions for future research arising from the scientific literature to date in relation to these and other questions?

What are the policy driving findings and rehabilitation implications of previous research?

Methods

The protocol for this review was published on Prospero, a database of protocols for systematic reviews in health, in 2022 [Citation19]. The interdisciplinary research team included researchers with disciplinary backgrounds in speech-language pathology, business, marketing, nursing and public health, and urban planning; a person with cerebral palsy and swallowing disability; a person with high level spinal cord injury who is also a researcher in disability and business; a parent of a child with intellectual disability who is also a researcher in design and the built environment; and a health services researcher whose brother has an intellectual disability. The team members collaborated in the design, analysis, and write-up of this report, first meeting to discuss and define the scope and parameters of the review and co-author the protocol. All team members met to discuss the data analysis, findings within the studies, and the ways that these related to the aims of the review. The team co-authored this report.

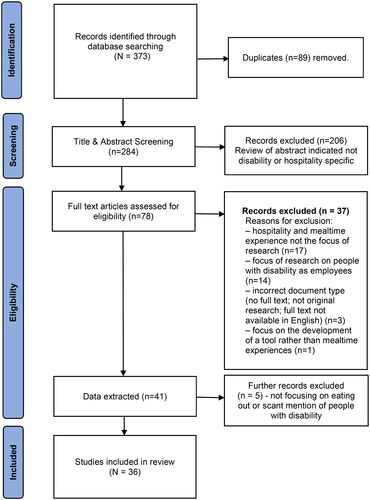

In July 2022, a systematic search of six scientific databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science) was conducted to locate peer-reviewed articles from any date written in English, reporting on original research or systematic reviews. Search terms (see ) were applied to each of the databases chosen and then the results of these searches were compared. This thorough search of the available research resulted in many of the same research papers appearing in the searches of multiple databases, (i.e., data saturation). Papers not written in English, editorials, narrative reviews, and conference papers were excluded. provides the search terms used in each of the databases. The search terms were developed by the whole team and were combinations and permutations of words related to the disability or conditions associated with disability (e.g. disability types, health conditions associated with disability), hospitality venues (e.g. restaurants, cafés), meal or food preparation and hospitality experiences (e.g. inclusion, access). The complete search strategy is available from the first author. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included, and a meta synthesis planned, as preliminary searches for relevant studies revealed a lack of controlled trials comparing interventions to improve the accessibility or eating out experiences of people with disability in hospitality venues.

Table 1. Search concepts and terms.

Titles and abstracts were initially screened by the first three authors for relevance using Covidence software [Citation20] designed to support systematic reviews through storage and retrieval of data along with tracking decisions to include or exclude studies from the review. Two reviewers independently undertook full text screening with a third rater consulted to resolve any differences of opinion and determine if a study should be included or excluded.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in the review, studies must have (a) been published in English, (b) related to hospitality settings with “mealtimes associated with eating out” and “disability”; (c) reported either systematic reviews or original research; and (d) if original research, included at least one person with disability, a support worker of a person with disability, or a hospitality staff member with views on their experiences with customers with disability. Studies were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria or related only to the experiences or employment of staff with disability in the hospitality sector. Finally, a manual search of the reference lists of the included articles was conducted to find any additional articles meeting the inclusion criteria. These were assessed against the criteria for inclusion. No additional studies were located in this manual search. The PRISMA flowchart is presented in .

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram for rapid review/study selection flow chart.

Data were extracted by the second and third authors, imported into an Excel data extraction spreadsheet and checked for accuracy and consistency of extraction by the first author. The data extracted included information on the location of the study, authors, year, type of study, methodology, tools used for data collection, aims, population of focus in the research, participants included and excluded, disability type, results relating to the aims of the review, any policy implications noted by the authors, directions for future research, and any limitations identified by the study’s authors. Each article was also checked for any policy mentions using Overton (a database of policies and guidelines) and these citations were added to the data extraction sheet. A full data extraction sheet for all studies is available from the first author.

Quality appraisal

The Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Design (QATSDD) was used to critically appraise the quality of research across diverse methodological designs [Citation21]. QATSDD was selected as it provides researchers with a tool to appraise methodological quality, evidence quality and the quality of reporting in all forms of mixed methods, quantitative or qualitative research. QATSDD has 16 specific items that focus on the explicitness, aims, clarity in describing the research setting, sample size, representativeness, recruitment, data collection, congruency, transparency, and organised reporting of the research study processes. By rating each of the items (not at all, very slightly, moderately, completely) researchers can compare studies across the diversity of methods, populations, and design. Once each of the items is scored an overall score for the research is derived. The quality appraisal was undertaken independently by two of the team experienced in using QATSDD and an overall score assigned to each research paper. Results were then reviewed and compared the team for agreement on individual ratings and the final score allocated to the article, and any differences of opinion resolved by consensus rating. Previous assessment of QATSDD indicated that applying this review and comparison technique to studies of diverse methodological designs has good reliability and validity [Citation21].

Content thematic analysis

As noted in the published protocol, the variety of paradigmatic and epistemological orientations, and lack of comparability in populations with disability across the range of studies, meant that (a) a meta-analysis was not possible; and (b) a qualitative synthesis using content thematic analysis was deemed both powerful and flexible enough to take a staged approach to the analysis. Data from the results and findings of each of the studies were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet by the second author and checked by the first and third authors for accuracy, prior to open coding and then creation of categories of meaning across the studies. The goal was to construct categories of meaning based on the identification, analysis, and reporting of repeated patterns across the data to connect elements of the data extracted from all the studies [Citation22].

The first stage of this inductive, qualitative metasynthesis involved reading and re-reading the texts for open coding of the data extracted. The first three authors assigned open codes to the findings of each of the included studies, identifying (a) units and categories of meaning within and across the studies, (b) any relationships between the codes to form categories, and (c) any connections or patterns that could be identified as content themes connecting the categories. The findings of the included studies were coded iteratively, with coders moving back and forth between the studies and reaching consensus at each stage of the analysis process (i.e., for codes, categories, and themes). The codes and categories were organized using a Microsoft Excel database, in which each study had one row with the same types of data extracted from each study for comparison, and new columns added to note the codes applied to each finding; and Word tables displaying the categories and including example quotes from relevant studies, enabling use of colour coding and comments in the margins from members of the research team. In the second stage of verification of the interpretive coding, the research team discussed the emergent framework of codes, categories, and content themes for verification. All members of the research team had access to the full text papers, the data extraction table, and the table of content codes, categories, and themes to guide their consensus discussions.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the 36 studies included in the review, including quality ratings, are presented in . The studies are numbered for ease of reference in later tables.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies arranged alphabetically by first author.

Quality appraisal

The quality appraisal ratings indicated that the quality was variable across the range of studies, with the highest-rated study at 90% [Citation47,Citation50] and the lowest at 40% [Citation29]. The overall quality of included studies was moderate to good with an average rating of 67%; however, 26 studies were rated low for the criterion of user involvement in research design.

Publication dates

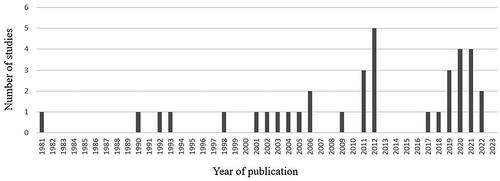

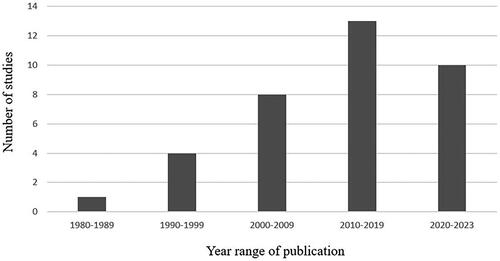

Studies were published in the years ranging from 1981 (n = 1) [Citation12] to 2022 (n = 2) [Citation4,Citation30]; with no studies located in the year range 1982–1990 (see and ). Indeed, 15 studies (41%) were published in the recent past (in or since 2017) indicating growing interest in this area of research; with each decade seeing at or almost a doubling of the number of studies. All but one study [Citation49] was published after the ADA [Citation9, 1990] and two thirds (n = 24) since its amendment Act in 2008; and all but 8 (or 72%) were published after the UN CRPD [Citation13, 2006].

Populations and settings

The 36 included studies were published in 15 different countries or areas (some studies were undertaken across multiple countries): USA (n = 20), Canada (n = 3), Taiwan Area of the Republic of China (n = 2), Korea = (n = 2), Spain (n = 2), and 10 other countries in Asia (2), Scandinavia (1), Europe (2), Middle East (2), Africa (1), and South America (2). In terms of populations at focus in the studies, studies related to either people with unspecified disability (n = 6, 17%), or with a mobility disability or impairment or a physical disability (n = 18, 50%), or being blind or having visual impairment, or Deafblind (n = 10, 28%), or having intellectual disability (n = 6, 17%), or communication disability after stroke (n = 5, 14%), or hearing impairment (n = 4, 11%), or swallowing disability (n = 1, 3%).

Of the studies included in the review, 29 (80%) focused on a full-service restaurant; nine (25%) included a focus on fast-food settings (with two thirds of these focused exclusively on fast-food settings and people with intellectual disability, the only setting at focus for this population); and five (14%) focused on cafés. All but five of the studies included data on the views of people with disability (n = 31, 86%); and five (16%) reported on the views of disability support workers, family members of people with disability, or hospitality staff providing services to customers with disability (see ).

Qualitative meta synthesis of findings

As noted previously, the qualitative meta synthesis involved the identification of categories of meaning and content themes within and across the studies, to answer the research questions. presents each study that contributed data to the content codes and categories.

Table 3. Content categories and sub-categories across findings in the included studies.

Views and experiences of hospitality staff and people with disability

Sixteen articles identified the attitudes of hospitality staff towards people with disability as a barrier to their inclusion in hospitality environments (e.g., [Citation16,Citation24,Citation27,Citation29,Citation36,Citation49]). Kim et al. [Citation16], and Lim [Citation17] identified community attitudes and a lack of empathy as a barrier to inclusion in eating out experiences. Staff attitudes were perceived to impact the person with disability’s eating out experience (e.g., [Citation24]) and led to the person with disability reporting a lack of confidence to request assistance when required [Citation27]. Bilyk et al. [Citation27] noted that many people who are blind or vision impaired may prefer to eat their evening meals in restaurants. However, if staff are unhelpful the person may order without complete knowledge of the menu. Cipriano-Crespo et al. [Citation4] noted that self-consciousness about disability and lack of confidence meant that people with disability often avoided eating out. For example, Anglade et al. [Citation24] found that, while staff may have the best of intentions, a lack of awareness can mean that they interrupt a social experience and conversation for people with communication disability.

Training of people with disability or hospitality staff

Seven of the articles related to studies that specifically investigated outcomes of training programs, and these involved training adults with intellectual disability to access services in a fast-food restaurant. Specifically, five studies [Citation23,Citation30–32,Citation35,Citation43] evaluated the success of a training program aimed at people with intellectual disability being able to make menu choices and navigate the ordering process. The studies described the training programs and the processes for evaluating success in accessing the fast-food services. All indicated that participants’ skills developed and were maintained over a period of time. One study [Citation23] described training parents or disability support staff to better support individuals with intellectual disability to make choices and to place orders. Two [Citation35,Citation43] noted that people with communication disability need training and support to improve their customer experience and increase their confidence in communicating with hospitality staff. Overall, seven studies [Citation18,Citation23,Citation24,Citation27,Citation29,Citation36,Citation50] identified hospitality staffs’ lack of training and skill as a barrier to people with disability accessing hospitality environments and 16 studies suggested that training for hospitality staff was needed. However, no studies specifically described any training provided for hospitality staff to support people with disability.

Factors related to the person with disability

Several studies identified the person with disability having limitations, particularly in relation to physical health and personal financial resources, confidence (e.g., [Citation4,Citation53]), and skills, which can impact an individual’s choice to eat outside the home. Five studies [Citation6,Citation16,Citation35,Citation38,Citation43] noted that the person with disability’s skills impacted opportunities to eat out but that training may improve this situation.

Only one study presented results related to the specific food that a person with swallowing disability consumes [Citation4]. Cipriano-Crespo et al. [Citation4] explained that many people with swallowing disability avoid eating in social situations and distance themselves from contexts where they feel uncomfortable and self-conscious. The authors suggested that this shame and embarrassment when eating out was associated with an individual’s need for texture-modified food and the way they consumed food or drink. Consequently, individuals might withdraw from eating out “for fear that their presence will subvert the unspoken hygiene rules that guide table manners, that dictate that food has to be attractive and people have to enjoy each other’s company” (p. 7).

Barriers to and facilitators for access and inclusion in eating out

Across the studies, a wide range of barriers and a small number of facilitators for the access and inclusion of people with disability and their families eating out in a range of hospitality venues were identified. These barriers and facilitators formed three main categories in order of commonality across studies: (1) Physical access to the hospitality venue and the services available, (2) Staff attitudes towards people with disability and need for training, and (3) The ability of the person with a disability to manage within the hospitality setting. presents the barriers to and facilitators for inclusion and participation of people with disability in restaurant, café, and other hospitality venues, identified in the research to date. The facilitators tabled appeared in the studies but did not necessarily propose ways to address the barriers identified.

Table 4. Three main categories of barriers and facilitators to access and inclusion across studies.

Physical access and service barriers and facilitators

Almost half of the studies (n = 16) identified physical access to the venue or the services as a barrier (e.g., [Citation26,Citation28]. Some, (e.g., [Citation33,Citation46,Citation53]) noted specifically the building or architectural codes had not been followed. Space problems that made access difficult for people with mobility issues included only providing buffet style meals [Citation26], small and narrow spaces [Citation41], and crowded access to the building [Citation36]. Service barriers included a lack of information [Citation38], lack of signage including no signs in braille [Citation6], prohibition of service animals [Citation38], and tables not being high enough for use by people using wheelchairs [Citation50]. In some studies (e.g., [Citation30,Citation51,Citation52]), barriers to physical access were noted but not specified, although ideas for facilitating a better experience were provided. Joo [Citation37] noted that “the most difficult aspect in restaurant usage is lack of facilities for the disabled and difficulties in access regardless of the type of disability.” (p245). Facilitators for physical access included adherence to building codes and the training of those who design buildings about the needs of people with a range of disability. However, studies on the effectiveness of these ideas or cost and building regulations were lacking.

Staff attitudes towards people with disability and training issues

Fifteen of the studies reported a lack of staff training and staff’s negative attitudes towards people with disability (e.g., [Citation16,Citation18,Citation25,Citation29,Citation49]). Chung and Lue [Citation22] noted that all participants were “afraid of being discriminated against, ignored and misunderstood…” (p. 126) and “that all of them have had the experience of being refused to be served, unless they were accompanied by “normal” people” (p. 126). One third of the studies (n = 12) identified communication barriers in customer-staff interactions as a barrier to people with disability eating out. Poria et al. [Citation50] highlighted issues with hospitality staff and their understanding and patience when dealing with people who have difficulty expressing themselves or with understanding spoken language. The difficulty of service encounters often reflected a lack of empathy and patience in staff in resolving communication difficulties. If hospitality staff are unhelpful or if communication is perceived as difficult, or a range of communication modalities are not available, the lack of access to information about the venue or the menu can impact negatively on the eating out experience. Despite the range of barriers identified, in most studies, the recommended facilitator was staff training [Citation3,Citation12–14,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23]. However, there was no indication in the included studies that staff training occurred or was effective, or indeed what should be the focus and evaluation of any training program.

The ability of the person with a disability to manage within the hospitality setting

Several studies suggested that the person with disability was somehow at fault or to blame for the difficulty in eating out. These faults included having health problems and lacking confidence [Citation4], lacking ability, lacking communication skills, and being untrained to manage in the context (e.g., [Citation35,Citation40,Citation43,Citation48]). Carlson and Myklebust [Citation28] noted that activities “outside the home, such as going to a restaurant, a sports event, or a movie obviously require more resources as well as better health.” (p. 43). Alvey and Aeschleman [Citation23], conducted a short training program aiming to assist mothers of children with disability to improve their child’s behaviours in cafes to better manage in that setting. Mechling and Cronin [Citation43] taught students (aged 17–21) with communication disability who used augmentative and alternative communication systems to communicate with the cashier in fast-food outlets. Nevertheless, for the most part, researchers have suggested the need for training but there is little research evaluating the implementation or outcomes of training programs to increase skills in the person with disability and their supporters.

Findings in relation to policy

Just over half (n = 19, 52%) of the included studies referred to the findings having policy implications, with data extracted and analysed across studies revealing a range of studies calling for further policy implementation, enforcement, and development. Areas for policy improvement included: (i) the implementation and enforcement of existing government policies on inclusion and accessibility for people with disability, including attitude change in the restaurant industry [Citation6,Citation30,Citation33,Citation35,Citation37,Citation40,Citation46]; (ii) development of new policies for government, society, service providers, and managers particularly in the context of the ageing of the population [Citation27,Citation34,Citation36]; and (iii) standardisation of procedures supporting implementation of the policies (e.g., of information display, staff training, universal design, food labelling) [Citation16,Citation17,Citation28,Citation38,Citation39,Citation41,Citation45], and (iv) public administration and funding being available to support services in policy implementation [Citation27,Citation40,Citation41]. The search of Overton for each study being mentioned in subsequent policy revealed that only three of the included studies had been cited into policy statements [Citation31,Citation36,Citation50], related to: economic impacts and patterns of accessible tourism [Citation50 cited in Citation54], supporting people with intellectual disabilities in decision-making [Citation31 cited in Citation55], and healthy community design [Citation36 cited in Citation56]. Three other studies had been cited in a European Commission report on food labelling [Citation6,Citation39 cited in Citation57] and study [Citation43] was cited a Cochrane review providing guidelines on speech and language therapy for children with cerebral palsy.

Discussion

The relatively small number of studies included in this review reflect the limited research attention given to the needs of people with disability in relation to eating out, and people with disability’s desire, and indeed, right to access eating out activities in a range of hospitality settings. There is some indication of recent growth in research in the past five years, although this does not yet include the full range of diversity in populations with disability, in particular people with communication or swallowing disability. Some of the studies were conducted before the rights of people with disability gained greater recognition [Citation13]. However, across the date range of included studies, more barriers than facilitators were identified in the literature. Increased training either of hospitality staff or people with disability was often mentioned (e,g., [Citation23] in 1990 and [Citation24] in 2021) yet there is little research or evaluation to support those suggestions. In addition, where studies involved training of people with disability to improve their skills in managing eating-out activities [Citation35,Citation42], disability was conceptualised as something to be fixed and there was little if any research focusing on improving the environment that would lead to inclusion. Similarly, some studies reflected stereotypical expectations of people with disability across the date range (e.g., a focus on people with intellectual disability accessing fast food outlets) (e.g., [Citation49] in 1981, [Citation23] in 1990, [Citation32] in 1998, [Citation31] in 2001, and [Citation35] in 2006).

Despite limited reports on the views and experiences of people with disability, these studies are important because they report customer dissatisfaction such as poor access [Citation28], negative attitudes of staff [Citation29], and communication barriers that need to be addressed [Citation39,Citation43,Citation45] for people with disability to exert their right to be included in the community through eating out. Where there was a focus on the experiences of people with physical or sensory disability, the findings were often limited to the physical accessibility of the environment [Citation30,Citation53] or encounters with service staff [Citation24,Citation36]; and did not provide insight into any need for or experiences of (a) mealtime assistance, or (b) availability of suitable texture-modified foods when eating out; two of the main forms of intervention to address the mealtime support needs of people with swallowing disability [Citation58,Citation59].

Views and experiences of hospitality venue staff and owners

Eating out with a range of companions is an important aspect of cultural life and social wellbeing [Citation1]. The attitudes of hospitality staff to customers, including those with disability, impact on the experience of being in a restaurant or hospitality environment. A lack of empathy and understanding may indicate that the hospitality industry does not identify people with disability as a potential target market for service, and that staff have very little experience providing their services to diverse communities including people with disability. Negative or ignorant attitudes can further impact the expectations, experience, and confidence of people with disability within a hospitality environment. Two studies, [Citation4,Citation24] identified the attitude of individuals with disability as a barrier to hospitality experiences. Cipriano-Crespo et al. [Citation4] noted that self-consciousness about their disability and lack of confidence meant that people with disability often avoided eating out. Anglade et al. [Citation24] noted that for many with a communication disability as a result of a stroke, interactions with unfamiliar people can be stressful and intimidating, but that greater understanding could provide knowledge about how to integrate these situations in rehabilitation programs and thereby potentially facilitate social engagement. People with disability are diverse, and their enjoyment of and willingness to engage in public spaces including hospitality venues may vary. Nevertheless, hospitality venues arguably have a responsibility to ensure that all customers, including those with disability, feel comfortable and accepted within the venue regardless of any impairments. Clearly, universal access, positive attitudes, and clear information and communication form part of this responsibility and conform with CRPD [Citation13].

Physical access and moving around

The built environment and wayfinding accessibility impacted the hospitality experiences of people with disability (e.g., [Citation26]). Depending on the country of residence, building and construction codes may have been introduced over long periods of time (e.g., [Citation11,Citation33]) the rate of compliance appears limited. There is still often a lack of basic access concepts, like accessible toilets or a continuous path of travel providing step-free access for people using wheelchair and others with mobility issues. Thus, there is a historical legacy of inaccessible built environments that require retrofitting to improve access [Citation11,Citation14,Citation46]. Even in major world cities signatory to CRPD, many hospitality venues still lack basic mobility access [Citation15,Citation60,Citation61]. The provision of information about access to a dining establishment would be helpful to anyone wishing to eat out in that space, to avoid the inconvenience and disappointment of not being able to climb steps into the venue or being unable to access basic facilities such as toilets.

Eating out for people with disability is clearly an ongoing concern that requires attention from research, and advocacy within the hospitality and building sectors. In particular, the overriding support for training to improve the experience for all stakeholders warrants further research and will not help if accessibility is the main barrier. Both staff training and training for individuals with disability have shown mixed results in improving attitudes and services towards people with disability. For staff training to be effective it must be embraced by the whole organisation from the top down and does not occur if the responsibility is taken by the staff involved in implementation alone (e.g., [Citation62]).

Absent from the research to date are studies taking an implementation science approach [Citation63] to what is a complex issue, as evidenced by the barriers and facilitators identified in this review. There are no reports on research examining the features or suitability of food for people with swallowing difficulties associated with disability, how staff would manage or respond to coughing or choking on food, or the willingness of hospitality and catering staff to modify food textures as required. Nor did any studies report on the provision of mealtime assistance, nor adaptive cutlery and/or crockery or straws to assist with food consumption in a hospitality environment. Furthermore, little attention has been given to modification of space or upgrading of facilities and the steps and potential costs that might be involved. For the most part, studies reviewed identified physical access to the venue or communication issues as the major issues for inclusion; but this limited view ignored the broad diversity of disability types and impacts that can limit engagement in social activities.

Policy implications

The findings of this review indicate that, despite repeated calls for better implementation of policies and growth in many areas of policy impacting the eating out experience of people with disability, there has been apparently little if any impact on policy and practice over the past three decades. Indeed, the year date of studies did not appear to make any material difference to the outcomes being reported in relation to inclusion and participation, and barriers or facilitators to eating out. Across three decades of research, there is little change in the nature of the reports on barriers to eating out and negative experiences; and a long-held call for implementation of current policies and for this to be monitored and enforced. A lack of policy focus in research to date further impoverishes the evaluation and development of standards, procedures, and training at a societal or local level that might lead to practice and behaviour change. With a relatively low rate of included studies being cited into policy or clinical guidelines, this systematic review could, by its synthesis of studies, be used to influence policy in the directions expressed by study authors. To increase the accessibility and inclusive practices being well supported by policies (e.g., on awareness raising, education, training, and implementation of policies), it is important that further policy development engages people with disability. Such engagement should ensure that any new policies work to (a) address the barriers to accessibility and inclusion identified in this review; and (b) enhance the facilitators to embed these into daily practice for both rehabilitation professionals and for hospitality service providers.

Clinical implications for rehabilitation

Given their focus on both the ICF [Citation11] and the social-relational model of disability, and upholding a person’s independence, inclusion, and participation in all aspects of society, rehabilitation professionals could implement a range of facilitators that might strengthen participation in eating out activities for people with disability. The findings of this review indicates that, given the access and inclusion barriers encountered, some people with disability will require support for increased self-determination and self-advocacy to access eating out experiences satisfactorily [e.g., Citation4,Citation24,Citation25,Citation40]. Goals and strategies to increase access and participation in eating out activities should include attention to the design of the environment and hospitality venues and to staff training [Citation25,Citation29,Citation30]. Rehabilitation professionals (e.g., occupational therapists, speech pathologists) have a role in training hospitality staff about disability access and inclusion in eating out activities, highlighting the benefits of supporting dignity and independence and effective communication at all stages of the complex interactions involved (e.g., in communicating to potential customers, booking systems, menu options, and service interactions). For example, speech and language therapists could suggest adaptations for restaurant and cafe owners to implement to make their outlets more communicatively accessible, particularly in countries where businesses are required to make their services fully accessible for people with communication disabilities (e.g., in Canada, US, Australia, United Kingdom, and India) [Citation64].

To enhance community inclusion and participation, rehabilitation professionals could focus more on the skills and strategies needed for people with disability to participate in eating out activities. Increasing the capacity and skills of individuals with disability eating out could help to improve their dining experiences. The new knowledge generated by this systematic review of the literature to date sets the challenge for strengthening the evidence-base and provides an important foundation recognising prior research and identifying gaps that need to be addressed urgently.

Limitations and directions for future research

This small study was limited by its inclusion only of studies in English, which may have reduced the body of literature available for inclusion to inform the results. While not explicitly excluded from this review, a broader search strategy to include studies relating to people with dementia as a primary health condition (e.g., not associated with Down syndrome) might have provided further insights to the review. The review having no restrictions on date included studies with different policy contexts in the countries where adoption of disability policy would have influenced the design and implications of the study. Furthermore, no attempt was made to analyse the policy settings of each included study, owing to the acknowledge complexity in this and lack of inclusion of this data in each study. Nonetheless, findings before and after UN CRPD [Citation13], and individual countries’ legislation (e.g., [Citation8,Citation9]) reflect similar barriers and facilitators to access and inclusion for people with disability eating out. Indeed, studies across the date range called for implementation of the policies of the day, standardisation of procedures, and monitoring or enforcement (i.e., strengthening of the requirements for accessibility and inclusion).

Further research could be undertaken to identify how to facilitate access to and encourage engagement with hospitality settings. Disabilities vary between individuals, and future research could focus on determining what physical interventions or tools could be developed to improve access, particularly to venues where the basic structures cannot easily be renovated. Further to this, in total, 24 of the studies (or 66%) provided some directions for future research, including (a) expanding the scope of future research to a broader range of populations with disability [Citation25,Citation33,Citation37], (b) further investigation of the impact of training people with disability [Citation23,Citation31,Citation32] or hospitality service providers [Citation24,Citation31]; (c) co-design research to include people with disability particularly in assessing hospitality access issues [Citation41,Citation47]; (d) interventions to improve access to food and eating out experiences [Citation27,Citation48]; (e) research on the use of technology including assistive technologies to improve eating out experiences [Citation4,Citation45]; (f) research on the outcomes of clinical rehabilitation interventions targeting eating-out skills and assistive technologies for people with a wide range of disabilities and their eating-out companions (e.g., adapting and managing texture-modified foods for safe dining; mobilising safely in dining settings; self-advocacy and communication skills in accessing restaurants; using online ordering or booking systems; making a complaint); and (g) research at the service level to investigate access, participation and inclusion and the impact of policies on hospitality experiences [Citation26,Citation36,Citation44].

Both earlier (see [Citation44]) and recent studies (see [Citation17]) noted that the hospitality sector does not recognise people with disability as a valuable market. Joint research involving the hospitality industry, people with disability, and researchers working in the field of disability, including those working in the field of swallowing disability or dysphagia, could focus on increasing the attention of the industry to this market and how changes to operations is likely to encourage engagement with their business. Implementation science approaches would be suitable for research aiming to understand ways to target barriers and facilitators to inclusion for people with disability eating out [Citation63]. People with disability must be included in any such projects. Furthermore, managing a variety of eating out opportunities could form part of rehabilitation or school programs along with programs that currently occur to promote independence. It is worth noting that in this review, only one study [Citation41] was co-designed with people with disability; involving a co-creation method and ethnographic approach with consultation with key stakeholders (e.g., a range of people with diverse disability, friends and family members, support workers and hospitality staff) at all stages of the study design and implementation.

Future research could also provide an evaluation on any training provided to any stakeholder, including planners, councils, architects and building designers, hospitality staff and people with disability and their supporters to ensure note only that skills are developed and maintained but also that eating out facilities are accessible to all. The involvement of people with disability in research relating to them is supported by the CRDP [Citation13] and vital because stakeholder meanings and experiences provide insights into their external reality. Further policy research could examine the development or changes in policy [Citation35] and enforcement [Citation6,Citation30,Citation33,Citation35,Citation40,Citation46] of existing policies, and standardization of procedures across settings and countries [Citation16,Citation17,Citation38,Citation41]. Implementation science designs consulting with all stakeholders across diverse settings might identify reasons for lack of implementation of current policies aiming to support the equal rights of people with disability to access healthy food [Citation36,Citation40] and eating out experiences. Finally, it has long been recognised that participation and social inclusion can benefit physical and mental health. Future research could identify the benefits for all stakeholders of people with diverse disabilities accessing and enjoying hospitality venues. This might encourage investment in appropriate design, training, and interventions in the hospitality industry.

Conclusion

People with disability have the same rights as other customers to access safe and enjoyable eating out experiences, and this includes an inclusive and accessible environment and empowering encounters with hospitality staff. Research to date, of a mixed quality, highlights that people with disability continue to encounter disabling attitudes and lack of knowledge in hospitality staff, along with a range of access barriers and lack of suitable supports in the environment, impeding their inclusion in dining out experiences. Yet, reasons as to why hospitality staff or venue responses to people with disability limit inclusion are not yet understood, and negative responses of staff are paradoxical given that the hospitality industry is premised on a welcoming of guests through customised and tailored service provision. The main focus of research has been on physical access to dining establishments, with little attention paid towards the need for mealtime assistance or texture-modified foods, and the dining out experiences of people with swallowing disability.

This review demonstrates that there is a paucity of research to date reflecting the full diversity and heterogeneity of people with disability, as studies to date have primarily focused upon the experiences of people with visible disability in restaurants and cafés and of people with intellectual disability in fast-food restaurants. While the hospitality and tourism industry has been innovative with respect to different food allergies or sensitivities and lifestyle food choices, it is less open to catering to people with disability, including swallowing disability, and their requirements. With greater research and increased awareness of these issues, the support required, and industry education this could be effectively resolved. This offers an opportunity to innovate and provide the support required for people with disability to enjoy accessible and safe meal preparation when dining out.

In the context of research in this field almost doubling each decade, this review provides a timely summary and analysis of research to date, across a range of policy contexts that should inform future research. However, there is little research to date examining the role of rehabilitation professionals across disciplines in supporting the functional skills of the person with disability, and the supports that they need for inclusion, in eating out activities. Larger scale, interdisciplinary and co-designed research should deepen understandings of the relationship the barriers and facilitators identified in this review, and the implementation of strategies to reduce barriers and enhance facilitators to inclusive dining. The activity of eating out crosses rehabilitation professionals’ disciplinary boundaries, so inter- and trans-disciplinary approaches could underpin future research design and by taking take an implementation science approach to understanding strategies identify those that are feasible and useful in the complex environment of hospitality venues. Co-designed research, particularly applying implementation science approaches, could (a) address priorities identified by people with disability, (b) create new knowledge that is useful to both people with disability and their supporters, and the hospitality industry to promote equitable, dignified, and enjoyable dining out experiences for this group, and (c) examine ways that policy enforcement and development could be supported by standards and flexible practices that can be tailored to individual environments to improve participation and inclusion in eating out experiences for people with a wide range of disabilities and across settings locally, nationally, and internationally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jönsson H, Michaud M, Neuman N. What is commensality? A critical discussion of an expanding research field. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6235. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126235.

- Adolfsson P, Mattsson Sydner Y, Fjellström C. Social aspects of eating events among people with intellectual disability in community living. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;35(4):259–267. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2010.513329.

- Boyer K, Orpin P, King AC. ‘I come for the friendship’: Why social eating matters. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35(3):E29–E31. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12285.

- Cipriano-Crespo C, Medina FX, Mariano-Juárez L. Culinary solitude in the diet of people with functional diversity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3624. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063624.

- Kniffin KM, Wansink B, Devine CM, et al. Eating together at the firehouse: how workplace commensality relates to the performance of firefighters. Hum Perform. 2015;28(4):281–306. doi: 10.1080/08959285.2015.1021049.

- de Faria MD, da Silva JF, Ferreira JB. The visually impaired and consumption in restaurants. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2012;24(5):721–734.

- Cipriano-Crespo C, Rodríguez-Hernández M, Cantero-Garlito P, et al. Eating experiences of people with disabilities: a qualitative study in Spain. Healthcare. 2020;8(4):512. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8040512.

- Disability Discrimination Act, 1992 (Cth). https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018C00125.

- Americans with Disabilities Act, 1990, and ADA Amendments Act of 2008. https://www.ada.gov/law-and-regs/ada/.

- Davey H, Imms C, Fossey E. “Our child’s significant disability shapes our lives”: experiences of family social participation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(24):2264–2271. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1019013.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability, and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health.

- Reindal SM. A social relational model of disability: a theoretical framework for special needs education? Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2008;23(2):135–146. doi: 10.1080/08856250801947812.

- United Nations. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. United Nations General Assembly A/61/611. 2006. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/convtexte.htm.

- Kayess R, French P. Out of darkness into light? Introducing the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Hum Rights Law Rev. 2008;8(1):1–34. doi: 10.1093/hrlr/ngm044.

- Darcy S, Taylor T. Disability citizenship: an Australian human rights analysis of the cultural industries. Leisure Studies. 2009;28(4):419–441. doi: 10.1080/02614360903071753.

- Kim J, Ladner JJ, Tran E, et al. Effect of mobile asl on communication among deaf users. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – Proceedings. 2011.

- Lim JE. Understanding the discrimination experienced by customers with disabilities in the tourism and hospitality industry: the case of Seoul in South Korea. Sustainability. 2020;12(18):7328. doi: 10.3390/su12187328.

- Swanepoel L, Spencer JP, Draper D. Education and training for disability awareness of front line hospitality staff in selected hotels in the cape winelands. Afr J Hosp Tour Leis. 2020;9(4):402–417.

- Hemsley B, L’Espoir Decosta P, Dann S, Darcy S, Almond B, Given F, Carnemolla P, Freeman-Sanderson A, Debono D, & Bobyreff N. People with disability and their experiences of mealtimes in cafes, restaurants, hotels and other venues: A systematic review. PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2021. Available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=338573

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. 2022. www.covidence.org.

- Sirriyeh R, Lawton R, Gardner P, et al. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: the development and evaluation of a new tool. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(4):746–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01662.x.

- Clarke V, Braun V. Using thematic analysis in counselling and psychotherapy research: a critical reflection. Couns Psychother Res. 2018;18(2):107–110. doi: 10.1002/capr.12165.

- Alvey GL, Aeschleman SR. Evaluation of a parent training programme for teaching mentally retarded children age-appropriate restaurant skills: a preliminary investigation. J Ment Defic Res. 1990;34 (Pt 5)(Pt 5):421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1990.tb01552.x.

- Anglade C, Le Dorze G, Croteau C. How clerks understand the requests of people living with aphasia in service encounters. Clin Linguist Phon. 2021;35(1):84–99. doi: 10.1080/02699206.2020.1745894.

- Anglade C, Le Dorze G, Croteau C. Service encounter interactions of people living with moderate-to-severe post-stroke aphasia in their community. Aphasiology. 2019;33(9):1061–1082. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2018.1532068.

- Atef TM. Assessing the ability of the egyptian hospitality industry to serve special needs customers. Manag Leis. 2011;16(3):231–242. doi: 10.1080/13606719.2011.583410.

- Bilyk MC, Sontrop JM, Chapman GE, et al. Food experiences and eating patterns of visually impaired and blind people. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2009;70(1):13–18. doi: 10.3148/70.1.2009.13.

- Carlson D, Myklebust J. Wheelchair use and social integration. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2002;7(3):28–46. doi: 10.1310/4VAG-D0BF-QLU5-Y1LT.

- Chung WC, Lue CC. Barrier-free dining environment for the visually impaired: a case study of restaurant in taichung, Taiwan. In: Zainal A, Radzi SM, Hashim R, Chik CT, Abu R, editores. Current issues in hospitality and tourism research and innovations. London: Taylor & Francis Group; 2012. p. 125–127.

- Cole S, Whiteneck G, Kilictepe S, et al. Multi-stakeholder perspectives of environmental barriers to participation in travel-related activities after spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(5):672–683. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1774669.

- Cooper KJ, Browder DM. Preparing staff to enhance active participation of adults with severe disabilities by offering choice and prompting performance during a community purchasing activity. Res Dev Disabil. 2001;22(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(00)00065-2.

- Cooper KJ, Browder DM. Enhancing choice and participation for adults with severe disabilities in community-based instruction. JASH. 1998;23(3):252–260. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.23.3.252.

- Crowe TK, Picchiarini S, Poffenroth T. Community participation: challenges for people with disabilities living in Oaxaca, Mexico, and New Mexico, United States. OTJR. 2004;24(2):72–80. doi: 10.1177/153944920402400205.

- Dashner J, Espin-Tello SM, Snyder M, et al. Examination of community participation of adults with disabilities: comparing age and disability onset. J Aging Health. 2019;31(10_suppl):169S–194S. doi: 10.1177/0898264318816794.

- Mechling LC, Pridgen LS, Cronin BA. Computer-based video instruction to teach students with intellectual disabilities to verbally respond to questions and make purchases in fast food restaurants. Educ Train Dev Disabil. 2005;40(1):47–59.

- Huang DL, Rosenberg DE, Simonovich SD, et al. Food access patterns and barriers among midlife and older adults with mobility disabilities. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:231489–231488. doi: 10.1155/2012/231489.

- Joo N, Cho K. Study on the utilization of restaurant services by the disabled and their demand for better access in Korea. Asia Pac J Tour Res. 2012;17(3):338–353. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2011.628327.

- Kaufman-Scarborough C. Publicly-researchable accessibility information: problems, prospects and recommendations for inclusion. Soc Incl. 2019;7(1):164–172. doi: 10.17645/si.v7i1.1651.

- Kostyra E, Żakowska-Biemans S, Śniegocka K, et al. Food shopping, sensory determinants of food choice and meal preparation by visually impaired people. Obstacles and expectations in daily food experiences. Appetite. 2017;113:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.02.008.

- Lee RE, O’Neal A, Cameron C, et al. Developing content for the food environment assessment survey tool (FEAST): a systematic mixed methods study with people with disabilities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217781.

- Lin PMG, Peng K-L, Ren L, et al. Hospitality co-creation with mobility-impaired people. Int J Hosp Manag. 2019;77:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.08.013.

- McClain L, Beringer D, Kuhnert H, et al. Restaurant wheelchair accessibility. Am J Occup Ther. 1993;47(7):619–623. doi: 10.5014/ajot.47.7.619.

- Mechling LC, Cronin B. Computer-based video instruction to teach the use of augmentative and alternative communication devices for ordering at fast-food restaurants. J Spec Educ. 2006;39(4):234–245. doi: 10.1177/00224669060390040401.

- Meek A, Uysal M. Restaurant owners’ attitudes toward the disabled and the Americans with disabilities act. J Hosp Tour Res. 1992;15(3):65–73. doi: 10.1177/109634809201500307.

- Obiorah MGS, Piper AM, Horn M. Designing AACs for people with aphasia dining in restaurants. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Mathura, India. 2021. doi: 10.1145/3411764.3445280.

- Peterson H. Built environment accessibility in the Eastern Province of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia as seen by persons with disabilities. J Access Des All. 2021;11(1):115–147.

- Park M, Kang-Hyun P, Park, Ji H, et al. The restaurant accessibility and task evaluation tool: development and preliminary validation. Ther Sci Rehabil. 2020;9(3):35–51.

- Plow M, Finlayson M. A qualitative study of nutritional behaviors in adults with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(6):337–350. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182682f9b.

- Pol RBA, Iwata MT, Ivancic TJ, et al. Teaching the handicapped to eat in public places: acquisition, generalization and maintenance of restaurant skills. J Appl Behav Anal. 1981;14(1):61–69. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-61.

- Poria Y, Reichel A, Brandt Y. Dimensions of hotel experience of people with disabilities: an exploratory study. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2011;23(5):571–591. doi: 10.1108/09596111111143340.

- Raanes E, Berge SS. Intersubjective understanding in interpreted table conversations for deafblind persons. Scand J Disabil Res. 2021;23(1):260–271. doi: 10.16993/sjdr.786.

- Soriano JM, Moltó JC, Mañes J. Improvement of accessibility for the disabled in university restaurants. Trav Hum. 2003;66(4):391–396. doi: 10.3917/th.664.0391.

- Hammel J, Jones R, Gossett A, et al. Examining barriers and supports to community living and participation after a stroke from a participatory action research approach. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2006;13(3):43–58. doi: 10.1310/5X2G-V1Y1-TBK7-Q27E.

- Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (European Commission). Economic impact and travel patterns of accessible tourism in Europe: final report, 2015. https://www.accessibletourism.org/resources/toolip/doc/2014/07/06/study-a-economic-impact-and-travel-patterns-of-accessible-tourism-in-europe–-fi.pdf.

- Bigby C, Whiteside M, Douglas M. Supporting people with cognitive disabilities in decision making – processes and dilemmas. 2015. Melbourne: Living with Disability Research Centre, La Trobe University.

- Werle C, Nohlen H, Pantazi M, et al. Literature review on means of food information provision other than packaging labels. EUR 31206 EN. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2022.

- Pennington L, Goldbart J, Marshall J. Speech and language therapy to improve the communication skills of children with cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2004(2):CD003466. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003466.pub2.

- Steele CM, Alsanei WA, Ayanikalath S, et al. The influence of food texture and liquid consistency modification on swallowing physiology and function: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2015;30(1):2–26. doi: 10.1007/s00455-014-9578-x.

- Reddacliff C, Hemsley B, Smith R, et al. Examining the content and outcomes of training in dysphagia and mealtime management: a systematic review informing co-design of new training. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2022;31(3):1535–1552. doi: 10.1044/2022_AJSLP-21-00231.

- Darcy S. Accessibility as a management component of the paralympics. In: Darcy S, Frawley S, Adair D, editors. Managing the paralympics. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan; 2017. p. 47–90.

- Legg D, Gilbert K. The paralympic games: legacy and regeneration. Champaign (IL): Commonground Publishing; 2011.

- Koski K, Martikainen K, Burakoff K, et al. Evaluation of the impact of supervisory support on staff experiences of training. Tizard Learn Disabil Rev. 2014;19(2):77–84. doi: 10.1108/TLDR-03-2013-0023.

- Harrison R, Ni She E, Debono D. Implementing and evaluating co-designed change in health. J R Soc Med. 2022;115(2):48–51. doi: 10.1177/01410768211070206.

- Collier B, Blackstone S, Taylor A. Communication access to businesses and organizations for people with complex communication needs. Augment Altern Commun. 28(4):205–218. doi: 10.3109/07434618.2012.732611.