Abstract

Purpose

This scoping literature review aimed to determine the definition of dignity in relation to disability. It also examined the extent to which inclusive research methods have been used to develop working definitions.

Materials and Methods

A comprehensive search was conducted in five electronic databases, using a modified framework by Arksey and O’Malley. Narrative synthesis and qualitative content analysis were employed to examine definitions of dignity and the use of inclusive research methods.

Results

22 peer-reviewed studies were included. The majority of the studies were qualitative (72.72%) and examined various disability populations in diverse settings. Although 19 studies offered a definition of dignity, there was no clear consensus. Dignity was frequently defined from a utilitarian perspective, emphasising affordances and barriers. However, engagement with theoretical constructs was superficial and limited. Further, no studies mentioned the use of inclusive research methods.

Conclusions

The absence of inclusive research methods hinders the development of a comprehensive definition of dignity that is accepted by and relevant to people with disability. Engaging with both theoretical and empirical perspectives of dignity is crucial to develop a meaningful and inclusive definition, which can inform interventions and policies that enhance dignity for people with disability across diverse settings and contexts.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

The adoption of inclusive research methods in disability research should be a priority for rehabilitation researchers and clinicians to better shape research agendas, study design, and outcomes.

The absence of inclusive research methods hinders the development of a comprehensive definition of dignity that is accepted by and relevant to people with disability

The findings emphasise the need to address dignity concerns within healthcare settings for people with disability.

Rehabilitation practitioners can advocate for person-centered approaches, improved communication and increased accessibility to create dignified healthcare environments.

Rehabilitation researchers and practitioners can play a pivotal role in advocating for social justice and equity by supporting policies and interventions that foster inclusive practices, dignity, and equitable opportunities for people with disability

Introduction

In 2006, the United Nations established the importance of dignity for people with disability by underpinning the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on the principle of human dignity [Citation1]. Dignity as a concept can provide hope to people who experience marginalisation and provides impetus that demands governments and communities protect it in some capacity [Citation2]. Indignity, the opposite of dignity, increases feelings of humiliation and withdrawal, and increases the risk of chronically poor physical and mental health [Citation3–8]. Despite being embraced as a concept by international bodies, national frameworks, healthcare strategies, and activists, dignity is still typically understood and experienced through a stigmatised view of human existence [Citation9,Citation10]. For people with disability, dignity is often understood in relation to the stigma and fear which associates disability with dependence and sickness [Citation9,Citation10].

In the current global context, in which people with disability experience economic, physical, attitudinal, systemic and environmental barriers [Citation11,Citation12], people with disability continue to be targets of exclusion, discrimination and oppression [Citation13–15]. For the over one billion people living with disability globally [Citation16], the struggle for a fairer and more inclusive society is becoming more difficult [Citation15]. Revised public expenditure re-examining social services and policies specific to the types of benefits for which people with disability are eligible are decreasing services and supports at a time when many people need it most [Citation17]. As services and supports are restricted, there is an increasing vulnerability to indignity, particularly for people with disability, impairment, injury and illness.

There is a growing body of literature, particularly in healthcare and palliative care settings, that examine perceptions and experiences of dignity [Citation3, Citation5,Citation6, Citation10, Citation18–21]. As evidenced in the literature, understandings and experiences of dignity can vary across different population groups. The increasing emphasis on dignity in research is important. However, the lack of disability perspectives [Citation10], particularly people for whom research has “historically been problematic and often tokenistic” [Citation22] is a major oversight. What results is a definition of dignity that is not underpinned by lived experience of people with disability, which then further entrenches the physical, attitudinal, and environmental barriers that contribute to ableism and discrimination [Citation14]. Because dignity is critically important for the delivery of human rights for people with disability, it is imperative to develop a holistic understanding of dignity, as derived and driven by lived experience. A lived experience perspective will allow for more practical, impactful protections and implementations of dignity and dignity work, addressing the criticism that dignity is a latent concept with little meaning.

Engaging the perspectives of people with disability in research must be done inclusively and with the intention to do so authentically [Citation22,Citation23]. Meaningfully engaging with consumers and people with disability in research requires dignified methods that “affirm the importance of individual lived experiences, personhood and indigenous knowledge” [Citation22]. Inclusive research methods must be applied which reduce the prevalence of the clinical voice and increase the emphasis of the community voice and experience [Citation24–26]. Inclusive research and engagement are thought to increase relevance and acceptability of research and lead to better implementation of results [Citation27]. An inclusive approach to including lived experience can increase recruitment and retention and improve the quality of research outcomes [Citation22].

To date, there is a noticeable gap in the literature related to dignity and disability. The aims of this scoping review are to determine if there is an existing definition of dignity as determined or understood by people with disability and to what extent people with disability have been inclusively involved in generating this definition. The aims will support the pursuit of a working definition of dignity at the intersection of disability.

Methods

Scoping reviews are used to examine complex concepts that have not yet been comprehensively examined and identify critical gaps in contemporaneous literature [Citation28,Citation29]. We chose a scoping review due to the broad objectives of the review and the intersection of broad concepts, which may require comprehensive synthesis across multiple disciplines [Citation30].

Inclusive research methods are critically important for both the objectives and the methods for this review. To ensure that the scoping literature review was grounded in the perspectives of lived experience of disability, the authorship team was formed to include a senior academic (EK) who is a family member of people with disability and has personal experience of a degenerative disabling health condition, and an established citizen scientist with disability (AD) who was embedded into the research team. Both members engaged in every stage of this review including its conceptualisation and the citizen scientist was remunerated both financially and in the currency of academia [Citation22]. Following the selection of the scoping review, the citizen scientist and first author defined the relevant terminology to be used, as language is an integral part of framing disability and confronting ableism. The language chosen and discussed in the terminology section below is a direct reflection of the contribution of the citizen scientist with disability.

Terminology

In this review, disability refers to the broadest possible definition, including physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments, injuries, or illnesses that may “hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” [Citation1]. We ascribe to the human rights model of disability, which acknowledges that disability results between a mismatch between impairment, injury, or illness and the society in which we live. The human rights model also allows for consideration of “bodily dimensions of both disablement and impairment”, including pain, fatigue, and de-conditioning [Citation31]. For the purpose of this review, permanency of impairment, injury or illness are not considered, as some of the diagnostic categories examined could lead to either and will depend on the individual. However, palliative care, terminal illness, and populations that were focused on aged and end-of-life care and dying with dignity were excluded. This choice was made to focus on living with dignity and disability rather than on dying with dignity and disability.

Inclusive research methods include any engagement with the target “population” of the research beyond typical forms of research participation [Citation27]. Terms for inclusive research may include “co-design”, “co-creation”, “co-production” [Citation32]. Citizen-led design, “participatory action research”, and any other mentions of “participatory”, “user-led”, “community”, or “collaborative” will be examined as inclusive research methods for the purpose of this review [Citation30, Citation33]. Inclusive research will also be considered in relation to the research team i.e., if there is a person with disability or a member of the studied population in the research team specifically disclosed.

Review design

The review followed the Arksey and O’Malley [Citation29] framework for scoping reviews with the enhancements recommended by Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien [Citation34]. All five steps of the framework were undertaken: (1) identify research question and purpose, (2) identify relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collate, summarise and report on the results.

The updated “PCC” (population, concept and context) guide from the Joanna Briggs Institute [Citation28] was used to design the review.

Identify research questions

The primary objective of the scoping review was to examine how dignity was defined by people with disability. Specifically, the review sought to answer two questions:

How is dignity defined and understood by people with disability?

To what extent are the definitions of dignity determined using inclusive research methods?

Identify relevant studies

Inclusion criteria

The review included peer-reviewed studies published in English in academic journals published between January 2012 and the end of January 2023. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in based on the “PCC” model.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for review.

Information sources

A comprehensive search was conducted across five electronic databases in January 2023: CINAHL complete, Taylor & Francis Online, ProQuest Central, Embase and Informit.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed by the first author in collaboration with the citizen scientist and in consultation with a qualified and experienced research librarian. The strategy was then provisionally applied to CINAHL complete and reviewed in consultation with the other members of the research team. Medical Subject-Headings (MESH) terms, keywords, and relevant database-specific terms were examined to create the final selection of keywords. The search was conducted by the first author in January 2023 using the five databases mentioned in information sources above. The search strategy was confined to abstract searching, in order to focus the search on the interplay of the key concepts and included the following search terms: Abstract (dignity OR dignified OR dignified care) AND Abstract (disabil* or impairment or impaired or special needs or injury or illness) NOT dying or death or end-of-life or bereavement or terminally ill or palliative care or child.

Study selection

The first author screened all titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. When the first author was unsure about eligibility, additional authors (EK, AD, and KC) were consulted about inclusion. The full-texts of the remaining studies were screened by the first author and AD for eligibility. Final decisions were made collaboratively and if consensus could not be reached, EK was consulted.

Charting the data and quality appraisal

A data charting spreadsheet was developed in Microsoft Excel, using a modified version of the suggested framework by Arskey and O’Malley [Citation29]. Following extensive discussions with the citizen scientist (AD), the data extracted from each study included: author(s), publication year, method, population, context, research design related to dignity, definition of dignity, key findings, and if/how inclusive research methods were utilised or discussed. We reviewed the inclusivity of the design, conduct and delivery, acknowledgements and conflict of interest statements. Data were charted by the first author and discussed with AD, who also read all articles at the screening stage, to ensure rigour and completeness.

The quality of the studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program checklist (CASP). The checklist was modified to suit the scoping review methodology, as recommended by Levac et al. [Citation34]. The checklist was used to assess relevance to the research question, and the appropriateness of the methods used to collect and analyse data, which allowed us to explore the extent of the evidence [Citation29,Citation30, Citation35].

Collating, summarising and report the results

A combination of narrative synthesis methods [Citation36] and descriptive qualitative content analysis [Citation28] was used to examine how dignity was defined – either by the authors of each study in the introduction, methods or discussion (theoretically) and/or by the study population as described in results and discussion (empirically). Synthesis was conducted by the first author. The results of the synthesis were reviewed and discussed with the citizen scientist.

Results

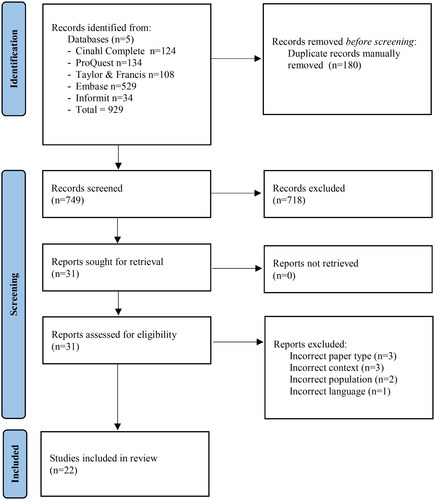

The systematic search conducted as part of the scoping review yielded 22 studies (See flow diagram in ). The characteristics of the included studies, including country, aims, study design, population, definition of dignity and key findings are described in .

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

The 22 studies were published across 19 journals, with Nursing Ethics the journal in which the majority of the studies were published (n = 5) [Citation37–41]. The majority of studies were qualitative (n = 16) in design, employing semi-structured interviews (n = 12) [Citation39–50], focus groups (n = 2) [Citation51,Citation52], and mixed qualitative methods (n = 2) [Citation3, Citation53]. The countries of origin for the studies were diverse, with the majority conducted in Iran (n = 7) [Citation37–39, Citation42, Citation48, Citation54,Citation55] and the USA (n = 4) [Citation3, Citation51, Citation53, Citation55].

The studies included people with varying health conditions, including people with long-term illnesses such as multiple sclerosis or dementia (n = 5) [Citation41, Citation46,Citation47, Citation50, Citation56], people with cancer (n = 4) [Citation39, Citation42, Citation54, Citation57], people with physical and/or mobility impairments or injuries (n = 3) [Citation3, Citation44,Citation45], and people experiencing heart failure (n = 2) [Citation37,Citation38]. One study each examined mothers with physical or sensory impairment [Citation43], people with mental illness experiencing homelessness [Citation53], people with intellectual disability [Citation51], people in a geriatric ward [Citation52], patients and staff in a psychiatric in-patient unit [Citation55], people who had a stroke [Citation40], people with burns [Citation48], and people with aphasia [Citation49].

Dignity was most frequently examined in the context of healthcare (n = 18), the most common of which were conducted in inpatient hospital settings (n = 10)

[Citation3, Citation37–41, Citation48, Citation52, Citation54,Citation55]. Beyond the healthcare setting, a single study explored dignity in the community [Citation45], built environment [Citation44], a day program [Citation51], and during periods of homelessness [Citation53] respectively.

Defining dignity

All of the included studies explored the ways that dignity was positively or negatively understood or experienced for their research participants. Despite this, 3 studies provided no clear definition of dignity [Citation43, Citation51, Citation54]. The remaining studies defined dignity in diverse ways, ranging from an aspect of inherent human worth or value [Citation41, Citation46, Citation48, Citation57], related to respect [Citation3, Citation37,Citation38, Citation41, Citation44,Citation45, Citation48, Citation50, Citation52, Citation55,Citation56], self-esteem and self-worth [Citation3, Citation41,Citation42, Citation44,Citation45, Citation52, Citation56], pride [Citation3, Citation42], independence [Citation48, Citation55], recognition and validation through acceptance [Citation40, Citation47, Citation49,Citation50, Citation53], and as a cultural concept that included human rights [Citation37–39]. Dignity was also defined as a cultural construct, based on the perception of interpersonal interactions that included mutual respect, empathy, compassion, acceptance and safety [Citation44, Citation49,Citation50, Citation52, Citation55,Citation56]. Three studies, all of which were conducted in Iran, defined dignity as a cultural or religious principle, emphasising pride, honour, and moral imperative [Citation42, Citation48,Citation49]. The subjective nature of dignity, as related to personal or individual perceptions, was also noted and described as related to self-worth, self-advocacy, and perceived independence [Citation3, Citation44,Citation45].

Engagement with the broader theoretical conceptualisations of dignity, although seemingly important, only occurred in 6 of the included studies [Citation3, Citation41, Citation47, Citation51,Citation52, Citation57]. All six briefly examined the two dominant theories of dignity- inherent dignity and contingent dignity - within their introduction and/or background sections. Inherent dignity often also referred to by the included studies as “human dignity” [Citation51,Citation52, Citation57] and “intrinsic dignity” [Citation47], best described by Rannikko et al. [Citation40] as an inviolable concept that recognises the value of every human being. Contingent dignity, also called by studies in this review “extrinsic dignity” [Citation47], has multiple dimensions, including dignity of identity [Citation52], “dignity of self” [Citation3, Citation40,Citation41], and “dignity of others/dignity in relation” [Citation3, Citation40,Citation41]. Contingent dignity can be lost or violated through interpersonal interaction [Citation3, Citation47]. Examination of contingent dignity was best articulated by Lind et al. [Citation3] who said that dignity was related to how people with disability “were treated and how they felt about themselves.” Jacobson’s [Citation4] taxonomy of dignity, a framework for contingent dignity, was most frequently used by included studies to unpack the dimensions of social dignity, including “dignity of identity” [Citation52], “dignity of self” [Citation3, Citation40,Citation41] and “dignity of others/dignity in relation” [Citation3, Citation40,Citation41].

Of the six studies that examined the theoretical concepts of dignity, only Rannikko et al. [Citation40] re-examined conceptualisations of dignity within the discussion and implications of the study, to propose a holistic definition of dignity. Rannikko et al. [Citation40] engaged with the key and critical dignity theorists, extending the theoretical construct for people with stroke in hospital care contexts.

All studies examined dignity through factors that enabled or threatened dignity or dignified experiences in some way. The most common way of conceptualising dignity was through a utilitarian view, whereby dignity was defined by what it affords a person, such as physical accessibility of built environments and spaces [Citation37, Citation43,Citation44, Citation52], inclusive attitudes and systems [Citation39–41, Citation43, Citation47–54], positive communication [Citation3, Citation37, Citation39, Citation41, Citation46, Citation49, Citation55], respect [Citation3, Citation37, Citation43–45, Citation48, Citation50,Citation51, Citation55], validation of individual preference and needs [Citation45,Citation46, Citation50], autonomy [Citation3, Citation40, Citation45, Citation48,Citation49, Citation56,Citation57], and privacy [Citation3, Citation37,Citation38, Citation54]. The opposite, sometimes referred to as barriers to dignity, were defined by the negative feelings generated or what was lost when dignity was not realized, including inaccessible built environments [Citation3, Citation44], negative relationships with healthcare staff [Citation3], illness related concerns and anxiety or depression [Citation37–39, Citation46–48, Citation56,Citation57], lack of transparency and empathic communication [Citation39, Citation43], feeling like a burden [Citation37, Citation40, Citation54, Citation57], loss of autonomy [Citation37,Citation38, Citation41, Citation47, Citation54, Citation57], economic insecurity [Citation39,Citation40, Citation47,Citation48, Citation54]. This utilitarian approach, while important to discussions of dignity, does not provide critical insight into how these affordances deliver dignity and more importantly, how dignity is still promoted when these affordances cannot be delivered.

Inclusive research methods

Following close examination of all 22 included studies, there were no studies that mentioned the use of inclusive research methods in the design, conduct and delivery of the relevant research. The role of people with disability was limited to that of participant only. It is unclear if any of the authors were/are people with disability, injury, illness or impairment or from the population group relevant to their specific studies. There is no clear disclosure by the authors about their own identity, but that does not mean that none of the authors identify as people with disability, it just cannot be determined from review of each study.

Discussion

The importance of inclusive research methods

The lack of inclusive research methods mentioned or examined in the included studies in this scoping review presents a significant problem in understanding and developing a working definition of dignity within the context of disability. By actively involving people with lived experience of disability in the research process, the emancipatory value of inclusive research can be realised, as it challenges the power imbalances and recognises the expertise and insights of the population that will be most impacted by the research results [Citation58]. For example, in the conduct of this scoping review, the contribution of a citizen scientist with disability improved the way in which we interrogated the studies, ensuring we adhered to both Critical Disability Theory and perspectives that confronted and challenged normative societal dynamics and perspectives. Authentic approaches to inclusive research help to ensure that research findings and recommendations are grounded in the lived experiences and priorities of people with disability, rather than researchers or health professionals, thereby enhancing the relevance and potential impact of research outcomes.

Principles and frameworks for inclusive research have been developed to guide researchers in conducting emancipatory and participatory research for people with disability. For example, Frankena et al. (2012) outlines ten principles for conducting inclusive research with people with disability [Citation59]. These principles emphasize the importance of valuing diverse perspectives, ensuring equal participation, and addressing power dynamics within research partnerships [Citation59]. Additionally, consensus statements, such as the one by O’Brien et al. [Citation60] for conducting inclusive health research with people with intellectual disability, provide specific guidelines and considerations for research that respects the dignity and agency of people with disability [Citation60]. Many of these types of frameworks and principles were published and publicly available at the time that the included studies in this literature review were published.

It is critical that peer reviewers, journal editors, and editorial policy begin to place emphasis on the importance of inclusive research methodologies and articulations within their author guidelines. Researchers ought to give priority to forming partnerships with people with disability and addressing power dynamics to ensure the inclusion and meaningful participation of diverse perspectives [Citation25–27, Citation61,Citation62]. Embracing a critical disability theory perspective is essential to challenge existing paradigms and promote scholarship that is bold, disruptive and led by lived experience of disability [Citation14]. By centring the voices and experiences of people with disability, inclusive research can contribute to a deeper understanding of dignity and support the realization of agency, social change and empowerment.

Defining dignity is a challenge, but a meaningful one

Concepts like dignity and dignity itself are notorious for evading concrete definitions [Citation58]. However, it is critical that a meaningful, potentially measurable definition be constructed. The aim of this literature review was to ascertain how contemporaneous literature defines dignity for people with disability to determine a working definition. Although 19 of the studies defined dignity, there was no obvious consensus across the studies about how dignity was defined by the priority population - people with disability, injury, illness or impairment. Despite frequently being on the receiving end of dignified and undignified experiences, people with disability are less frequently asked about their perceptions of dignity [Citation63]. When people with disability were asked about dignity, as participants within the included studies, it typically resulted in a complex list of affordances and barriers, including humiliation, staff behaviour, lack of communication and attitudes [Citation3, Citation8, Citation64], with little clarity about what these terms actually mean for the definition of dignity, beyond a utilitarian approach. Understanding the factors that affect dignity- positively or negatively- is not enough for developing a definition [Citation40].

Some of the divergences in definitions and explanations of dignity could be a result of the different specific populations included in each study. Definitions were developed by synthesising evidence from multiple actors (people with disability, clinicians, family members) [Citation3]. Most studies operated using a tight inclusion criterion versus only including individuals who have cancer or people with spinal cord injury, in comparison to this review which intentionally adopted a broad definition of disability. It is difficult to determine whether disability type or diagnosis impacts on the way a person views and defines dignity, but it is plausible as individual identities and experiences impact worldview [Citation8]. Perspectives on dignity may vary from one population to another, and in different settings. However, there is a need to develop unifying principles and a definition about dignity for all people with disability that support the implementation and realisation of dignity in interactions with other people, systems and services.

Conclusion

Despite the difficulties of defining dignity for people with disability in an inclusive, meaningful way that can be implemented into practice, it is critically important to pursue this body of research. This scoping review aimed to examine the existing definitions of dignity as understood by people with disability. Despite the included studies articulating definitions of dignity, none articulated the use of inclusive methods, which may limit the applicability of the definitions in practice. Most of the definitions were utilitarian in approach, defining dignity through affordances and barriers. Despite this, the review has significant implications for disability research. It highlights the relevance and importance of understanding and developing a working definition of dignity form the perspectives of people with disability, particularly in the healthcare context, where the majority of included literature was based. Many people with disability experience the healthcare system during the course of their injury, illness, diagnoses, and rehabilitation, and then frequently throughout their lives as they manage their impairments. However, it is also important that the focus of dignity research at the intersection of disability is expanded outside of the healthcare systems, to better address the holistic requirements for dignity. By examining the broader contexts in which people with disability live, work and engage in society, research can better advocate for social justice, equitable participation, and inclusive practices that enhance dignity for people with disability.

It is critical to move beyond the utilitarian and tokenistic examinations of dignity, to develop both deeper theoretical linkages and inclusive empirical perspectives of dignity for people with disability [Citation22, Citation59, Citation65,Citation66]. The limited engagement of all studies included in this review, with the theories of dignity, fails to provide full insight into the origins, dimensions, and theoretical conceptualisations of dignity and how they are constructed, manifested and experienced in various contexts. The foundation would be useful for future research in exploring the nuances and complexities of dignity and its relevance in different settings. Authentic engagement with theoretical constructs of both dignity and disability is also needed, to develop a more comprehensive understanding that can inform laws, policies, and practices [Citation67].

Understanding the multidimensional aspects of dignity can guide researchers and policymakers and practitioners to promote practical implementation of dignity into policies and service design and delivery. Developing a meaningful definition of dignity which articulates a level of consensus across diverse people with disability can contribute to the development of recommendations for implementation. These recommendations have the potential to improve disability tailored interventions and optimise engagement and outcomes for people with disability. Recommendations may also contribute to the development of policies and protocols that are more respectful, responsive and empowering for people with disability.

This scoping review demonstrates that dignity is not currently defined inclusively from the perspectives of people with disability. It also presents current gaps and challenges to developing an inclusive, practical, comprehensive working definition of dignity that adequately engages with both theory and empirical results. Future research should continue to interrogate empirical results with links to theoretical implications, adopt inclusive research approaches, and move beyond healthcare contexts to further enhance both practice and research, as well as the overall experiences of dignity for people with disability.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the research librarians at Griffith University and A/Prof Carolyn Ehrlich for her ongoing support in the design of this scoping review.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- United Nations. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD). 2006. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- Gilabert P. Human dignity and human rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018.

- Lind JD, Powell-Cope G, Chaves MA, et al. Negotiating domains of patient dignity in VA spinal cord injury units: perspective from interdisciplinary care teams and veterans. Ann Anthropol Pract. 2014;37(2):130–148. doi: 10.1111/napa.12027.

- Jacobson N. A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9(1):3. (doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-3.

- Baillie L. Patient dignity in an acute hospital setting: a case study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(1):23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.003.

- Berglund B, Mattiasson AC, Randers I. Dignity not fully upheld when seeking health care: experiences expressed by individuals suffering from Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(1):1–7. doi: 10.3109/09638280903178407.

- Brown SM, Azoulay E, Benoit D, et al. The practice of respect in the ICU. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(11):1389–1395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1676CP.

- Gazarian PK, Morrison C, Lehmann L, et al. Patients’ and care partners’ perspectives on dignity and respect during acute care hospitalization. J Patient Saf. 2020;17(5):392–397. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000353.

- Clark J. Defining the concept of dignity and developing a model to promote its use in practice. Nurse Times. 2010;106(20):16–19.

- Jones DA. Human dignity in healthcare: a virtue ethics approach. New Bioeth. 2015;21(1):87–97. doi: 10.1179/2050287715z.00000000059.

- de Melo-Martin I. Human dignity, transhuman dignity and all that jazz. Am J Bioeth. 2010;10(7):53–55. doi: 10.1080/15265161003686530.

- Pothier D, Devlin R. Critical disability theory: essays in philosophy, politics, policy, and law. Vancouver: UCB Press; 2006.

- Goodley D. Disability studies: an interdisciplinary introduction. Melbourne: Sage Publications; 2017.

- Shildrick M. Minority model: from liberal to neo-liberal futures of disability. In: Vehmas S, Watson N, editors. Routledge handbook of disability studies. 2nd ed. London: Routledge. 2020.

- Vehmas S, Watson N. Routledge handbook of disability studies. 2nd ed. London: Routledge. 2020

- World Health Organisation. Disability. 2023. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health#:∼:text=An%20estimated%201.3%20billion%20people,1%20in%206%20of%20us.

- Flynn S. Perspectives on austerity: the impact of the economic recession in intellectually disabled children. Dis Soc. 2017;32(5):678–700. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2017.1310086.

- Barclay L. Disability with Dignity: justice, Human Rights and equal status. Taylor and Francis Group: Proquest Ebook Central. 2019. Available from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.libraryproxy.griffith.edu.au/lib/griffith/detail.action?docID=5490915.

- Carrese JA, Geller G, Branyon ED, et al. Direct observation checklist to measure respect and dignity in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):263–270. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002072.

- Lohne V, Aasgaard T, Caspari S, et al. The lonely battle for dignity: individuals struggling with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Ethics. 2010;17(3):301–311. doi: 10.1177/0969733010361439.

- Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care- a new model for palliative care- helping the patient feel valued. J Am Med Ass. 2002;287(17):2253. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2253.

- Chapman K, Dixon A, Cocks K, et al. The dignity project framework: an extreme citizen science framework in occupational therapy and rehabilitation research. Aust Occup Ther J. 2022;69(6):742–752. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12847.

- Bonny R, Ballard HL, Jordan R, et al. Public participation in scientific research: defining the field and assessing its potential for informal science education: a CAISE inquiry group report. 2009. Available from https:///www.informalscience.org/sites/default/files/PublicParticipationinScientificResearch.pdf.

- Cox R, Molineux M, Kendall M, et al. Different in so many ways: exploring consumer, health service staff, and academic partnerships in a research advisory group through rapid ethnography. Aust Occup Ther J. 2022;69(6):676–688. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12830.

- Atkin H, Thomson L, Wood O. Co-production in research: co-researcher perspectives on its value and challenges. Brit J Off Ther. 2020;83(7):415–417. doi: 10.1177/0308022620929542.

- Hammell KRW, Miller WC, Forwell SJ, et al. Sharing the agenda: pondering the politics and practices of occupational therapy research. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19(3):297–304. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2011.57415.

- Cox R, Kendall M, Molineux M, et al. Consumer engagement in occupational therapy health-related research: a scoping review of the Australian occupational therapy journal and a call to action. Aust Occup Ther J. 2021;68(2):180–192. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12704.

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Bray EA, Everett B, George A, et al. Co-designed healthcare transition interventions for adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;44(24):7610–7631. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1979667.

- Shakespeare T, Watson N. Frameworks, models, theories and experiences for understanding disability. In: Brown RL, editor. The oxford handbook of the sociology of disability. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2022. Available from doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190093167.013.1.

- Ehrlich C, Slattery M, Kendall E. Consumer engagement in health services in Queensland, Australia: a qualitative study about perspectives of engaged consumers. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(6):2290–2298. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13050.

- Zamenopoulous T, Alexiou K. Co-design as collaborative research. Bristol University: AHRC Connected Communities Programme. 2018.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. (doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Lockwood C, dos Santos KB, Pap R. Practical guidance for knowledge synthesis: scoping review methods. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2019;13(5):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2019.11.002.

- Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):59. (doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59.

- Bagheri H, Yaghmaei F, Ashktorab T, et al. Test of a dignity model in patients with heart failure. Nurs Ethics. 2018;25(4):532–546. doi: 10.1177/0969733016658793.

- Bagheri H, Yaghmaei F, Ashktorab T, et al. Relatinoship between illness-related worries and social dignity in patients with heart failure. Nurs Ethics. 2018;25(5):618–627. doi: 10.1177/0969733016664970.

- Bagherian S, Sharif F, Zarshenas L, et al. Cancer patients’ perspectives on dignity in care. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27(1):127–140. doi: 10.1177/0969733019845126.

- Rannikko S, Stolt M, Suhonen R, et al. Dignity realisation of patients with stroke in hospital care: a grounded theory. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26(2):378–389. doi: 10.1177/0969733017710984.

- Žiaková K, Čáp J, Miertová M, et al. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of dignity in people with multiple sclerosis. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27(3):686–700. doi: 10.1177/0969733019897766.

- Azadi M, Azarbayejani M, Tabatabie SKRZ. Dignity in Iranian cancer patients: a qualitative approach. Mental Health Relig Culture. 2020;23(7):519–531. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2020.1712592.

- Collins B, Hall J, Hundley V, et al. Effective communication: core to promoting respectful maternity care for disabled women. Midwifery. 2023;116:103525. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2022.103525.

- Gibson BE, Secker B, Rolfe D, et al. Disability and dignity-enabling home environments. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.006.

- Kirk TN, Haegele JA, McKay C. Exploring dignity among elite athletes with disabilities during a sport-focused disability awareness program. Sport, Ed Soc. 2021;26(2):148–160. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2020.1713078.

- Lopez C, Bertram-Farough A, Heywood D, et al. Knowing about you: eliciting dimensions of personhood within tuberculosis care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(2):149–153. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0630.

- Podolinská L, Čáp J. Dignity of patients with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative descriptive study. Cent Eur J Nurs Midw. 2021;12(3):413–419. doi: 10.15452/cejnm.2021.12.0016.

- Tehranineshat B, Rakhshan M, Torabizadeh C, et al. The dignity of burns patients: a qualitative descriptive study of nurses, family caregivers, and patients. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00725-3.

- Tomkins B, Siyambalapitiya S, Worrall L. What do people with aphasia think about their health care? Factors influencing satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Aphasiology. 2013;27(8):972–991. doi: 10.080/02687038.2013.811211.

- Nygren Zotterman A, Skär L, Söderberg S. Dignity encounters: the experiences of people with long-term illnesses and their close relatives within a primary healthcare setting. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2022;23(e72):1–6. doi: 10.1017/S1463423622000603.

- Frounfelker SA, Bartone A. The importance of dignity and choice for people assessed as having intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil. 2021;25(4):490–506. doi: 10.1177/1744629520905204.

- Hubbard RE, Bak M, Watts J, et al. Enhancing dignity for older inpatients: the photograph-next-to-the-bed study. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41(5):468–473. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1398796.

- Jensen PR. Undignified dignity: using humor to manage the stigma of mental illness and homelessness. Comm Quart. 2018;66(1):20–37. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2017.1325384.

- Avestan Z, Rahmani A, Heshmati-Nabayi F, et al. Perceptions of iranian cancer patients regarding respecting their dignity in hospital settings. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(13):5453–5458. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.13.5453.

- Khorasanizadeh MH, Noee MG, Jamshidi T, et al. A comparative survey of the attitudes of nurses, nursing students, and patients as to the observance of the patients’ dignity in the psychiatric ward. AMJ. 2018;11(5):273–277. doi: 10.21767/AMJ.2017.3263.

- Klůzová Kráčmarová L, Tomanová J, Černíková KA, et al. Perception of dignity in older men and women in the early stages of dementia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):684. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03362-3.

- Philipp R, Mehnert A, Lehmann C, et al. Detrimental social interactions predict loss of dignity among patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(6):2751–2758. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3090-9.

- Series L. Disability and human rights. In Vehmas S, Watson N, editor. Routledge handbook of disability studies. 2nd edition. Longond: routledge. 2020.

- Frankena TK, Naaldenberg J, Cardol M, et al. A consensus statement on how to conduct inclusive health research. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2019;63(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/ijr.12486.

- O’Brien P, McConkey R, García-Iriarte E. Co-researching with people who have intellectual disabilities: insights from a national survey. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2014;27(1):65–75. doi: 10.1111/jar.12074.

- Beeker T, Glück RK, Ziegenhagen J, et al. Designed to clash? Reflecting on the practical, personal, and structural challenges of collaborative research in psychiatry. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:701312. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.701312.

- Happell B, Scholz B, Gordon S, et al. I don’t think we’ve quite got there yet.” the experience of allyship for mental health consumer researchers. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2018;25(8):453–462. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12476.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s welfare 2019: data insights. Australian government. 2019. Available from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/australias-welfare-2019-data-insights/contents/summary.

- Chochinov HM. Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. Student BMJ. 2007;335(Suppl S3):0709328. doi: 10.1136/sbmj.0709328.

- Layton NA. Syliva docker lecture: the practice, research, policy, nexus in contemporary occupational therapy. Aust Occup Ther J. 2014;61(2):49–57. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12107.

- Pereira RB, Whiteford G, Hyett N, et al. Capabilities, opportunities, resources and environments (CORE): using the CORE approach for inclusive, occupation-centred practice. Aust Occup Ther J. 2020;67(2):162–171. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.1264.

- Rioux MH, Valentine F. Does theory matter? Exploring the nexus between disability, human rights, and public policy. In Pothier D, Devlin R, editors. Critical disability theory: essays in philosophy, politics, policy and law. Vancouver: UCB Press. 2006.