Abstract

Purpose

Functional neurological disorders are common, highly stigmatised and associated with significant disability. This review aimed to synthesise qualitative research exploring the experiences of people living with motor and/or sensory FND. Identifying their needs should inform service development, education for healthcare professionals and generate future research questions.

Method

Five databases were systematically searched (Medline, PsychInfo, Web of Science, Embase and Cinahl) in November 2022, updated in June 2023. Data from included papers was extracted by two authors and studies were critically appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Data was thematically analysed and synthesised.

Results and conclusions

12 papers were included in the synthesis describing the views of 156 people with FND. The overarching theme was uncertainty; about what caused FND and how to live with it. Uncertainty was underpinned by four analytic themes; challenging healthcare interactions, loss of power and control, who or what is responsible and living with a visible disability and an invisible illness. Early and clear diagnosis, validation and support for living with FND should form part of multidisciplinary care. Co-produced service development, research agendas and education for clinicians, patients and the public would reduce stigma and improve the experiences of people with FND.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

A clear diagnosis and explanation of motor and/or sensory functional neurological disorder is validating and an important first step in recovery.

People with motor and/or sensory functional neurological disorder experience significant disability, stigma, self-blame and functional impairment.

Multidisciplinary care pathways for functional neurological disorder urgently need to be developed.

There is a need for co-produced education and training for healthcare professionals which covers how to deliver diagnoses and personalised formulations, communicate concepts of applied neuroscience and challenges stigma and discrimination.

Introduction

Functional neurological disorders (FNDs) occur when a person develops symptoms such as paralysis, dystonia, tremors, sensory disturbance, speech problems or seizures which are not caused by neurological disease but which result in significant illness and disability [Citation1]. The symptoms can appear similar to neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and Parkinson’s disease, however utilising specific examination techniques assessing for “positive” clinical findings, motor and sensory FND can be reliably diagnosed [Citation2]. Although changing definitions and labels have affected epidemiological studies, the incidence of FND is estimated to be 4–12 per 100,000 population [Citation3], accounting for somewhere between 6% and 16% of neurology outpatient consultations [Citation4, Citation5]. Despite being a common condition, patients frequently face long delays in receiving a diagnosis [Citation6], are sometimes given incorrect treatments and may experience iatrogenic harm [Citation7].

Previous theories of FND were underpinned by a Freudian model of “conversion”; the idea of intolerable trauma or stress converted into a physical symptom [Citation8]. Such concepts are reflected in the older labels “psychogenic” and “conversion” disorder [Citation9]. Newer explanatory models informed by detailed clinical and neuroscientific techniques describe how a range of previous sensitising events including physical injury, medical illness and physiological triggers may contribute to abnormal predictions of sensory data and body-focussed attention [Citation10, Citation11]. Similarly, recent functional neuroimaging studies have established dynamic abnormalities in multiple brain networks and confirmed FNDs are not under voluntary control [Citation12]. Furthermore, whilst psychological stress and trauma is common in people with FND, such experiences are more likely to play a role in sensitising and perpetuating symptoms, rather than representing a unifying causal pathway [Citation13, Citation14].

More recent classification of “Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (DSM-5) focusses on a positive diagnosis, and removes the need for identifying a precipitating stressful event [Citation15]. The term “functional” has also been found to be more acceptable to patients, when compared to other descriptors such as “conversion,” “psychogenic” or “medically unexplained” [Citation9].

Patients with FND experience considerable disability, distress and persistent symptoms [Citation16, Citation17]. However, early diagnosis and high satisfaction with care are associated with positive outcomes [Citation16]. Although the evidence base for treatments remains limited there have been some promising results from increasingly powered trials and longitudinal studies of inpatient and day hospital multidisciplinary interventions showing reductions in symptom burden, improving quality of life and patient understanding of their condition [Citation10, Citation18–20]. Vital in any treatment plan is an early and clear diagnosis, transparent communication of examination findings [Citation16], and a multidisciplinary rehabilitation focussed approach which embraces mind-body connections [Citation10, Citation20, Citation21]. Frequently occurring co-morbid symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive issues, pain, conditions including mood and post-traumatic stress disorder, and a variety of FND subtypes [Citation22] mean that personalised formulation and treatment is important [Citation20].

Despite advances in neuroscientific understandings, healthcare professionals often hold outdated and negative beliefs about FND being feigned or continue to utilise terms such as “psychogenic” with significant associated stigma [Citation23]. A recent study by the charity FND Hope found that 85% of 503 self-selected patients globally had felt disbelieved or dismissed by healthcare professionals [Citation24]. Patient advocacy groups, bioethicists and clinicians argue for the need for further research which explores stigma, and gives a voice to people with lived experience of FND [Citation25]. Qualitative research has the potential to highlight marginalised experiences, restore agency and connection, and guide care and research which addresses what is most important to individuals affected by a condition [Citation26].

Systematic reviews synthesising qualitative research can inform practice, identify unmet needs and future research agendas [Citation27, Citation28]. To date, reviews have been conducted exploring the experiences of functional seizures [Citation29], and views of a variety of professionals [Citation23]. A qualitative systematic review of 21 studies of the experiences of people with functional seizures described negative interactions with healthcare professionals and a significant burden of living with seizures [Citation29]. A synthesis of the views and experiences of 2769 healthcare professionals working with people with FND found that many felt unsure how to diagnose and treat FND and tended to avoid and pass patients on, leading to a “vicious cycle” where patients receive poor care [Citation23].

Motor FND includes symptoms such as paralysis or weakness, gait disorders, tremor, myoclonus, tics (jerky movements) and dystonia [Citation21]. Functional sensory symptoms include altered or absent sensation in the affected area [Citation30]. Although sensory disorders commonly co-occur with weakness or movement disorders, they are relatively less studied [Citation30]. Functional communication, swallowing and cough disorders [Citation31], drop attacks [Citation32] and functional forms of dizziness [Citation33] affect sensory or motor function and are increasingly recognised as functional disorders by experts in their respective fields. Further description of symptom types and terms used in this review are found in . To date literature focussing on the experiences of these specific patient groups have not been explored. Therefore, the aim of this review was to systematically collate, evaluate and synthesise the experiences of people living with motor and/or sensory FND as reported in qualitative research. It was anticipated that this review would inform education for clinicians, service development and future research questions.

Table 1. Terms and definitions used in this review.

Method

This review aimed to systematically review and synthesise relevant literature using a thematic approach described by Thomas and Harden [Citation36]. Thematic synthesis is a methodology adapted from meta-ethnography and grounded theory [Citation27]. It was chosen for its retention of primary qualitative research elements, such as line by line coding in combination with the rigor of a systematic review. The methodology seeks to go beyond aggregation and comparison of individual studies to generate new interpretations about the sample as a whole [Citation27]. The approach is recognised as useful in collating and translating qualitative research into evidence which can inform healthcare policy and practice [Citation36]. The protocol was pre-registered on PROSPERO [Citation37]. Where relevant to a qualitative synthesis the study was reported according to the PRISMA (Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) checklist [Citation38]. ENTREQ (Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research) checklist [Citation39] has also been completed and is found in Supplemental Appendix 1. Although the research question was broad a systematic rather than a scoping review was chosen because early preparatory searches suggested sufficient high-quality published papers were available for analysis and a rigorous systematic approach and appraisal could synthesise current knowledge and identify gaps [Citation40].

Search strategy

An adapted rather than standard PICO (population, intervention, control, outcomes) question, with the additional specifier of study design (S) was employed to achieve focussed findings as this has been described as more appropriate for qualitative reviews [Citation41]. The PICOS and search terms can be found in Supplemental Appendix 2. This strategy was combined with additional search approaches to maximise sensitivity, as described below.

Following consultation with co-authors and librarians at King’s College London, five databases were chosen for their coverage of relevant domains including medicine, health sciences and psychology: Medline, PsychInfo, Web of Science, Embase and Cinahl.

Initial draft searches to hone search terms were carried out in June 2021. The formal search process was undertaken by CB in November 2022, updated in June 2023. The aim was to identify all relevant papers on the topic and therefore hand searches of relevant journals were also completed by AT. Forward and back citation searching was undertaken, and authors and researchers were contacted to inquire if they were aware of any additional papers. Details of the additional search strategies are described in Supplemental Appendix 2.

Dates were restricted to the year 2000 onwards to capture experiences of patients currently living with FND and its contemporary understandings. This date was chosen as there has been a renewed interest in FND since the year 2000 [Citation42] and leading experts in the field identify the millennium as a turning point in modern conceptualisations and diagnostic categories [Citation43]. Due to the languages spoken by co-authors and lack of additional funding for translation only studies published in English were included.

Inclusion criteria

The pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria were agreed by co-authors and described in the PROSPERO protocol [Citation37].

Population and setting

The study included research populations of adult or older adult participants who were currently or had been affected by functional motor or sensory symptoms and at some point in contact with health services, i.e.: a clinical population. The FND would ideally have been diagnosed by a health professional within the study itself, however self-report of FND was considered acceptable and professional confirmation of diagnosis was not considered necessary for inclusion. Preliminary searches indicated a relatively small number of studies such that an inclusive approach would potentially provide important information. This was considered especially relevant when other methodological aspects of such studies might offer benefits such as larger sample sizes that can be attained in recruitment conducted by FND charities. Such studies also have other strengths including being designed by patients themselves. Self-reported diagnoses were also permitted to allow the broadest representation beyond only participants currently accessing services. It has been well documented that people with FND are often diagnosed and discharged without any treatment [Citation44]. Studies where patients experienced comorbid functional seizures and functional motor or sensory symptoms were considered where data could be extracted specific to the experience of the motor or sensory symptoms.

Study types and methodologies

Included study types utilised qualitative techniques such as interviews, focus groups, surveys with open-ended responses, or studies of treatment or educational programmes where patients provided qualitative information on their experiences of FND. Mixed-method studies were included where it was possible to extract qualitative data. Additional information about inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Supplemental Appendix 2.

Study selection

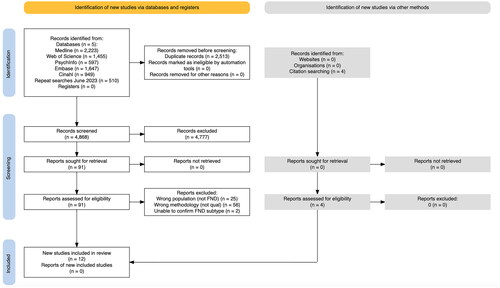

Titles and abstracts for all searches were imported into Rayyan Systematic Review Software. Duplicates were reviewed and excluded by CB. Both CB and AT independently assessed all abstracts against inclusion criteria and agreed on 91 papers for which full texts were sought and read in full. Full texts were similarly assessed by CB and AT independently and reasons for exclusion were recorded in Rayyan and are described in the PRISMA diagram (, generated using PRISMA 2020 Application [Citation45]).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

In studies where the subtype of FND was unclear authors were contacted. In one case the author responded but data on subtype was not available and the study was excluded. In the second case the author did not respond and a decision made to exclude the study. Any full text papers where there was disagreement or uncertainty [Citation46–49] were brought to co-authors ABW, NP and TRN and a resolution agreed.

Data extraction

Both CB and AT independently extracted data on study design, recruitment strategy, participant demographics, funding, diagnoses, specific symptoms, comorbidities, duration of illness, type of analysis and main findings (). Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

Qualitative data handling

QSR International’s NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software was used to handle and analyse data. Although there is debate about what constitutes data in qualitative reviews, this study followed guidance of Thomas and Harden [Citation33] and included results and conclusions sections from studies. Discussion and author interpretations were considered in contextualising findings but not coded.

Quality assessment

All included papers were evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative papers to assess methodological quality [Citation58]. In order to capture detail on the relative methodological strengths of each paper an adapted scoring system was used, similar to that employed in other qualitative systematic reviews [Citation59, Citation60].

Scores were not used to exclude papers, however they helped contextualise the methodological rigor of individual studies and extracted data.

CB and AT independently rated each paper and discussed scores and resolved differences. Each paper’s total scores are included in and detailed assessment in Supplemental Appendix 3.

Data analysis

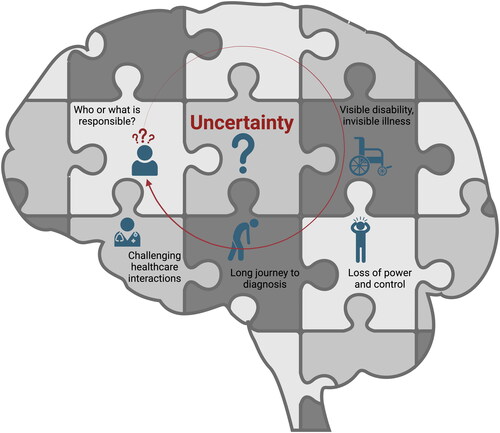

The thematic synthesis included three overlapping stages [Citation36]. The first was line by line coding of the data from each study, completed by both CB and AT independently using NVivo 12. Coding focussed on the raw quotes from participants to develop an inductive synthesis. Descriptive codes were then collated into an Excel spreadsheet and CB and AT met to share and compare codes, collate duplicates and combine overlapping concepts and ensure all raw data was represented in the final 163 codes with illustrative quotes. These were then allocated broadly according to initial subheadings for example “diagnostic process,” “effect on functioning.” Using a shared document CB and AT grouped descriptive codes into 43 descriptive sub-themes. At this point the descriptions stayed very close to the original data, for example “no (societal) permission to be ill if the illness has no name.” Each reviewer separately and collaboratively used the illustration programme Miro to develop analytic interpretations and shared these later with authors TRN, NP and PG who contributed to the discussion of themes and agreement on the overarching theme of “Uncertainty.” Part of the final process was to depict this pictorially where AT developed prototype diagrams and CB utilised BioRender for the finished which illustrates the interconnected and relational nature of the themes. The 5 analytic themes therefore go beyond the findings of the original studies and generate new interpretations [Citation36].

Figure 2. Illustration of synthesis and relationships between themes. Created with Biorender.

Results

The searches returned 4868 unique abstracts which were screened leading to 91 full text papers. 8 papers met inclusion criteria and a further 4 papers were located through citation searching of included papers leading to the 12 papers included in the final analysis ().

Overall paper quality was moderate to high, with recent papers demonstrating a more robust description of methodology and author reflexivity in keeping with advances in validation of qualitative research [Citation61].

The experiences of a total of 156 people, including 119 women and 37 men with motor and/or sensory FND types, drop attacks and Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD) were represented. A further unspecified number of participants views were included from a paper exploring experiences described on blogs and patient websites [Citation48]. Although comorbidity of different FND subtypes was common some studies specifically focussed on functional motor symptoms (65 participants) [Citation50–52], experiences of functional stroke (36 participants) [Citation56], PPPD (27 participants) [Citation46, Citation47, Citation53], and drop attacks (7 participants) [Citation49]. In the majority of studies a diagnosis of FND [Citation51, Citation52, Citation54], PPPD [Citation46, Citation47, Citation53] or drop attacks [Citation49] was confirmed by specialist examination. In two studies patients were recruited from a clinical population where their symptoms were “unexplained” [Citation55] or likely to have a functional cause [Citation57]. Two studies involved recruitment via charities or patient groups; Bazydlo and colleagues [Citation50] sought confirmation but not evidence from participants for a functional movement disorder diagnosis and Brenninkmeijer [Citation48] analysed message boards so diagnoses were not confirmed. Ethnicity was described in only 4 of the papers and where specified the participants were either all or majority white [Citation47, Citation51, Citation55, Citation57].

Nine studies recruited from a UK population with the remaining studies conducted in the USA [Citation52], New Zealand [Citation46], and Netherlands (but drawing on patient websites from across English speaking countries) [Citation48]. Qualitative methodologies included thematic analysis [Citation47, Citation56, Citation57], Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) [Citation50, Citation51, Citation53], interpretative descriptive methodology [Citation46], grounded theory [Citation49], conversation analysis [Citation54], textual analysis using ATLAS.ti [Citation48] and narrative analysis [Citation55].

Results of the synthesis

Uncertainty

The core theme of the experience of motor and sensory FND in this review was one of uncertainty. Central to the challenge of navigating life with FND was the uncertain nature of what causes FND, how to explain and treat it, and tension and confusion between the personal experience of symptoms and dualistic medical explanations. depicts the interconnected nature of the five analytic themes: (1) Uncertainty; (2) Navigating challenging healthcare interactions: a long journey from dismissal to diagnosis; (3) Loss of power and control (and how to regain it); (4) Who or what is responsible?; (5) Visible disability, invisible illness.

Navigating challenging healthcare interactions: a long journey from dismissal to diagnosis

Participants across the studies described frequent negative experiences with healthcare professionals; interactions characterised by disbelief, dismissal of the patient’s reports of their body and symptoms [Citation46, Citation48–56].

Many navigated an arduous and uncertain path, through health systems and different clinicians to receive a diagnosis of FND [Citation48–52] or subtype such as PPPD [Citation46, Citation58]. Participants searched for explanations, receiving incorrect diagnoses in the process, sometimes resulting in iatrogenic harm and leading them to question their own sanity [Citation49–56]. “It had been years of me trying to deal with … a debilitating situation where I thought ‘what is this? Is it my fault? Am I depressed? Am I doing this to myself?” – P05, a woman with drop attacks [Citation49].

Most participants in recent studies had received a diagnosis of FND, although those without diagnoses were left in a state of confusion, uncertainty, feeling unable to move forward [Citation54, Citation55, Citation57]. Many described being told what diagnoses they didn’t have, rather than what they did [Citation46, Citation54, Citation56, Citation57]. Some recounted being presented with negative test results and clinicians being surprised that they weren’t more relieved [Citation56]. Even when given a formal diagnosis of FND, this came only after other conditions were excluded, which seemed to contribute to a lack of confidence and uncertainty [Citation46, Citation56]. “Ahh I, I took it as bullshit really….You can’t find anything specifically wrong with me. My brain MRI is clear…So it has to be a functional neurological disorder. Because we can’t find anything else wrong with you.” – Michael, aged 46 with functional movement disorder [Citation56]

Identifying a cause of the symptoms created tension in appointments, where participants experienced clinicians using negative test results or stressful life history [Citation52, Citation56] as proof symptoms were of psychological origin [Citation48, Citation54, Citation56]. “I kept asking the doctor, but his answer was always, we did all kinds of tests and there is nothing there, believe me it’s only in your head, go to see psychiatry… I felt so humiliated, how could my problems be only in my head?” (A patient with functional weakness, age and gender not known) [Citation48]. This discord was observed in real time, in Monzoni et al.’s conversation analytic study where patients demonstrated resistance to the doctor’s explanation [Citation54]. The doctor is talking about stress and trauma as trigger for FND and Steph, a 39 year old man with functional paralysis and pins and needles responds, “To be honest, I don’t believe in things like that. I’m a counsellor, I’m well educated and I understand that some people may hang on to baggage and traumas, but it’s not how I live my life.” [Citation54]

For some, a diagnosis of FND, with the associated stigma and assumptions about psychological causes, led to a fear of life-threatening diagnostic overshadowing [Citation50–56]. “Now it’s on my medical record, I am really concerned that if I do have a stroke—because I can still get strokes or anything else—they’re gonna just assume it’s FND and write me off” – Hannah, a 34 year old woman with functional weakness, drop attacks, twitches and gait disturbance [Citation50]

Patients sensed implicit judgement and stigma from some clinicians, and felt doctors thought they were responsible for their condition or malingering; leading to feelings of shame and humiliation [Citation46, Citation47, Citation50–56]. “I was very angry at first, because it’s as if you are putting it on and wasting people’s time, but I am not that sort of person. I do not like hospitals.” Noel, aged 56 years, who experienced a functional stroke [Citation57]

Gamble and colleagues’ study [Citation53] noted a specific type of dismissal, where the participant identified sexism which had been pervasive throughout previous interactions. “Even before I’d gone in (and I was upset) he’d already decided there was nothing wrong with me. You could tell….Middle-aged, middle-class man. Crying lady. I’ve seen it, because it happened at the doctors before,” reported Lara, 29, diagnosed with PPPD [Citation53]

Participants described being dismissed and discarded after an FND diagnosis was made, or other diagnoses ruled out. Some interpreted this as lack of professional education and others perceived disinterest and disregard of functional conditions [Citation48, Citation50–57]. For example Sarah, a 21 year old woman with left sided weakness described, “Yeah, he said… you haven’t got a brain tumour and you haven’t got cancer, I’ve got other patients. Like, he said like, because I didn’t have cancer he didn’t want to help me” [Citation56]. Lack of clinician awareness of functional disorders awareness was often reported, and patients needing to provide education [Citation46, Citation47, Citation50–56], for example in the experiences of Hannah, a 34 year old woman with functional weakness, drop attacks, twitches and gait disturbance, “I had a GP say to me: ‘[it’s] a unicorn condition’ which I found quite offensive… I was taken aback and didn’t say anything but I wish that I had” [Citation50].

Two papers included perspectives of healthcare professionals (of unspecified discipline) also diagnosed with FND [Citation50] or PPPD [Citation53]. They reflected on stigma perpetuated by professionals’ lack of training and time in consultations. Lynn, 24 year old woman with unilateral weakness, twitches and gait disturbance described her FND diagnosis, “I was like: oh my God. How have I come this far as a professional and not been told about what this really was?… I myself stigmatised against functional patients because I didn’t know any better… My colleagues had taught me: ‘it’s functional, they’re just making it up, there’s nothing we can do to help them, but you just have to go along with it’”[Citation50].

Participants shared rare positive interactions with healthcare professionals, which did not exclusively have to be clinicians familiar with FND, but believed the patient, were caring, thorough and willing to seek more information [Citation50, Citation51, Citation53]. For example, as described by Anne, a woman in her 70s with dystonia, “It made you feel better knowing that somebody was interested in what was the matter with you. Rather than somebody who just made you feel as though they didn’t care less.” [Citation51].

For many receiving the diagnosis of FND was illuminating. The description of symptoms and explanation resonated with experience, giving validation and relief many had waited years for [Citation47, Citation48, Citation51, Citation56]. “It was nice to actually put a name to it, because it seemed like no one knew what was going on. It was like everyone was going to give up … and for about a decade people weren’t taking me seriously.” (P12), age unknown, with PPPD [Citation47]. However, often relief swiftly gave way to disappointment at a lack of follow up, or services which offered no little or no treatment [Citation46, Citation47, Citation50–57]. “You go and see the neurologist, but they can’t do anything for you—’we’ll see you at the next appointment’—which makes you think, why go to the next appointment because what’s the point?” Frances, aged 45, a patient with functional movement disorder [Citation50]

Confusion about what FND was sometimes left patients wishing for a more recognisable disorder such as MS, or a brain tumour with a clear treatment pathway or peer support [Citation46, Citation55]. As Elvy, aged 30 with PPPD described, “I don’t know how many times I wished I had lost an arm or something instead of, which sounds horrible and sounds really selfish because I don’t know how difficult it would be to have lost a limb or something but just it is more visual so you feel like people will understand” [Citation46].

Loss of power and control (and how to regain it)

Living with FND was described as a loss of power and control both of the body and also metaphorically; of expectations about the future, life, job roles and relationships [Citation46–48, Citation50–53]. The experience of symptoms in all descriptions was underpinned by uncertainty, confusion and fear. Some experienced their symptoms as pure loss of control, where there was nothing or no one in control [Citation48, Citation50–56]. As Gemma, a 43 year old woman with functional weakness described, “I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t move my mouth, I was just making noises, sort of screaming and wailing because I was angry and scared” [Citation50]. Others described the loss of control as if an external or additional force had taken over [Citation48, Citation51] as illustrated by Mary, a woman in her 40s with tics and tremor reported, “Right, I’m trying really hard”… to try and make it still, and it just won’t! …It’s almost like it’s just got a mind of its own…” [Citation51].

Frequently reported was a disconnection and dissociation, sometimes between the self and the world or the self and body [Citation48, Citation49, Citation52, Citation53]. For example, “An out-of-body experience” – a patient with a diagnosis of CD, age unknown [Citation48]. Many also described how trying to regain control of FND symptoms rarely helped, and battling would sometimes bring on depression and hopelessness [Citation48, Citation50, Citation51]. Mary, a woman in her 40s with tics and tremor expressed, “Trying to push myself all the time and nothing was happening. I think … that’s what brought the dark days… I felt exhausted from trying to continue to be normal” [Citation51].

Beyond symptoms themselves, and a loss of freedom and trust in the body, some participants described how FND controlled them and their lives [Citation46, Citation47, Citation49–56]. “It stops me from having a social life, stops me going to work, stops me from doing anything. It controls me, I don’t control it, it controls me.” – P2, a patient with PPPD [Citation47]. The sense of powerlessness also existed within healthcare relationships and systems. Doctors were seen as gatekeepers of services and a few patients resorted to paying privately to access treatment [Citation50–56].

Regaining control was often not about trying harder, but about tricks and counterintuitive actions [Citation50]. Progressing in recovery was sometimes about listening to, accepting and reconnecting with, rather than fighting for control of the body [Citation47, Citation50–52]. For some, this reconnection and acceptance of the body also meant accepting fluctuations and help from others [Citation51, Citation52]. “Now I am more attuned to my body—now when I have a down day, my family knows they need to cook and clean and take care of the house.” – P30, a 43 year old woman with gait abnormalities [Citation52]. Some participants reported a renewed appreciation of the mind-body relationship [Citation48, Citation51]. Zoe, woman in her 20s with tremor and dystonia described, “I think it’s all just been learning about your own body and what works better and getting that balance.” [Citation51].

Who or what is responsible?

Overlapping with loss of control and tensions with healthcare professionals was patients’ experience of the uncertain origins of their symptoms. Reports varied between attributing fault to the body, the mind, an external factor or a combination of these [Citation48, Citation50–54]. Rita, woman in her 30s with tremor, described “blaming myself… blaming my body.” [Citation51]. A patient with diagnosis of “conversion” disorder illustrated, “I can’t trust me anymore cos I don’t know who’s lying my body or my brain?” [Citation48].

Explanations presented by healthcare professionals often did not offer clarity [Citation48, Citation50–54]. For some participants the lack of clear explanation, uncertainty around the origin of symptoms and perceived judgement from healthcare professionals appeared to lead to blame turning towards the self [Citation46, Citation47, Citation49–56]. For example, as ID3, a 36 year old woman with coordination, mobility and intermittent paralysis and slurred speech described feeling “Guilt, being a fraud, a timewaster, that the whole thing is something I’ve manifested and in some way I’m perpetuating its ongoing” [Citation55].

A diagnosis of FND was potentially validating through the confirmation that the condition was real, but also putting a distance between illness and the person. For many participants this helped to shift blame from the self to a disorder and for some signalled the beginning of recovery [Citation48, Citation51, Citation56]. As Zoe, a woman in her 20s with tremor and dystonia described, “When you’re having a bad day, it’s… ‘Damn you, FND,’ … when you can put the blame onto something else, then you can think about how to overcome that something else, how you’re gonna get there coz you’re not just blaming yourself all the time. I think that was probably a big turning point for me” [Citation51].

The causal attribution of symptoms was often a source of contention between patients and clinicians, where patients experienced clinicians as overestimating the effect of psychological stress or emotions as a main trigger for FND. However, some participants demonstrated nuanced understanding of the role stress played in their condition, often seeing it as a perpetuating factor more than a cause or not relevant to their individual situation [Citation48, Citation51–53]. Amy, a 43 year old woman with functional head and limb tremor described, “We all have stress, we all have anxiety and it all depends how we deal with it…But I’m not sure that’s relevant to me. I do get stressed, I do worry [have] anxiety, which we all do. I don’t think I’m overly stressed or anxious” [Citation56]. Others noted symptoms persisted even when they felt calm, causing them to question how stress related to their illness [Citation46, Citation47, Citation49, Citation50, Citation53], for example P06, a woman with drop attacks recounted, “You could say reduce your stress and then it won’t happen, well it still can. You can be totally stress free and standing washing your dishes and (fall)” [Citation49]. For others the lack of obvious trigger gave a sense of symptoms “coming out of nowhere” (Zaynab, 43 year old woman with PPPD [Citation53]) leading to uncertainty and loss of confidence.

Participants also identified physical triggers at the onset of their FND which felt important, and overlooked by clinicians who focussed more on psychological stress [Citation46, Citation47, Citation49, Citation56], described here by P4, a woman diagnosed with PPPD, “I guess a lot of the symptoms do resonate with me and I think that I have got that, probably triggered by an acute BPPV (Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo) event of something … yeah I guess it’s a functional problem.” [Citation47].

A few patients who had started physical treatments such as physiotherapy alongside psychotherapy were able to see a role for psychological treatments as an adjunct or as improving their general emotional wellbeing [Citation50–52]. This led to a reduced sense of blame and increased acceptance of a variety of factors which might be responsible and how to address these. As Rita, a woman in her 30s with tremor described, “I felt a little bit alienated, like: … Why do I need to come to [psychology]? …but I think it’s just helped me learn to accept the tremor, and… understand a bit more about how functional neurological disorders work” [Citation51].

Visible disability, invisible illness

Participants across almost all papers described challenges not only of living with a chronic illness, but one poorly understood and stigmatised by clinicians and society. We conceptualised this as a “visible disability, invisible illness” dichotomy, in which people with FND may present with outwardly-visible impairment, but lack of societal and health service awareness about FND, or lack of diagnostic clarity rendered participants’ illness experience invisible.

The visible disability manifested in symptoms such as falls, tics or abnormal movements and lead to embarrassment and shame in public and affected participants’ ability to engage in work and family life [Citation49–56]. Anne, woman in her 70s with dystonia described, “when your face goes to one side, …you feel as ugly as sin… I don’t like going out because I feel like a freak and …everybody’s staring at me… I cover my face up with a handkerchief …so they can’t see it” [Citation51].

The uncertainty around FND as a condition, frequently attributed to psychological factors or personal failings was internalised by some participants [Citation46, Citation47, Citation49–56]. Mark, a 53 year old man with tremors, spasms and limb weakness recounted, “Some people have a fixed idea that it’s a psychological condition and that’s what hurts the most… They think you’re just lazy or not bothered, that you’ve given up” [Citation50].

The invalidation experienced in social interactions also seemed to link to personal feelings of being undeserving, as well as challenges in accessing support, which some felt might have been available for other medical conditions [Citation50–56]. This difficulty in accessing support as part of the sick role despite significant functional impairment is described here by ID, 40 year old woman, whose symptoms include disturbed mobility, coordination, blurred vision and fatigue, “I wasn’t allowed to come to terms with my illness… It’s there obviously because of the wheelchair, but everyone just treated it as an invisible entity that was not to be talked about” [Citation55].

Although symptoms were often visible, participants experienced a silence and invisibility around FND in interactions with health professionals and society more broadly [Citation49–51, Citation53, Citation55]. This affected how they communicated about their illness with employers, colleagues or friends [Citation46, Citation47, Citation49–51, Citation55]. “You feel embarrassed to say what it is because you can’t really describe…” reported Thea, a 66 year old woman with PPPD [Citation46]. For some this led to not disclosing their FND and trying to continue without adjustments [Citation50]. Others gave an alternative name (such as “myoclonus” or “brain injury” [Citation50]), which they hoped colleagues would understand. “[Colleagues] don’t know about what the condition is. I didn’t tell them. I didn’t want to appear weak….” said Harriet, a 32 year old woman with tremor and leg weakness [Citation50]. Some were humiliated when their roles were reduced by employers, for example Jude, a man in his 50s with dystonia recounted, “[I was given a] lesser role, like an “apprentice” doing the jobs nobody wanted to do…I felt embarrassed coz I couldn’t do a proper job; it were just like, like licking stamps, like rubbish” [Citation51]. Others were unable to work at all due to symptom severity, with significant financial implications [Citation49, Citation51, Citation52]. “I’ve been off [work] for the last 13 months…. I’ve lost virtually a year of my life because of my condition… It’s not knowing whether you’re going to get better or not,” said Michael, 46 year old man with functional motor disorder [Citation56].

The fluctuating nature of symptoms contributed to uncertainty, made it hard to communicate to friends and family and left participants questioning the validity of the condition, with a fear of being considered malingering [Citation50, Citation51, Citation53]. Mary, a woman in her 40s with tics and tremors described “…at times I wouldn’t go out, for six months, because I wasn’t at work and if somebody saw me, what would they be thinking… I might be having one good day in six months. But if I go out and they see me…” [Citation51].

Family life was affected with participants describing loss of ease in relationships, changing roles, having to depend on others and feeling like a burden [Citation46, Citation47, Citation49, Citation51–53]. Elvy, a 30 year old woman with PPPD described, “Guilt that I am ruining my husband’s life and dreams of also having children, travel, socialising, as he is stuck with me being dependent on him driving me and earning our living” [Citation46].

Participants’ confidence was impacted, often avoiding situations where they would experience symptoms; leading to a shrinking physical and social world [Citation46, Citation49–53, Citation55]. Some participants with PPPD specifically identified a link between symptoms and secondary anxiety and avoidance of going out [Citation53]. The isolation of living with FND was a combination of symptoms themselves, associated disability and the disorder being poorly understood. This doubt, blame and disconnection from society contributed to a changed sense of self, hopelessness, despair and at times suicidal thoughts [Citation46, Citation47, Citation49–53]. Lyna, a 54 year old woman with PPPD described being “anxious and cautious all the time” and having lost “the ability to be spontaneous” [Citation46]. This was echoed by P04, a woman with drop attacks, “There was one stage when, not for a wee while, but one stage when I was like ‘what’s the point? What’s the point in going on anymore?’” [Citation49]

Also contributing to a more hidden type of disability were a variety of comorbidities or additional symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, headache and dissociation [Citation46,c–Citation53]. However, many participants also recognised of their own strength and described having adapted to living with FND, which included tolerating uncertainty and complexity [Citation46, Citation48–56]. This was often described as both taking control and acceptance; a listening to the body and getting on with life. “Occasionally, I get a little bit anxious about it, but not really, not to the point where it stops me living my life. Brains are complex things, that’s the only thing I’d say,” reported Michael, aged 23 years who had functional stroke symptoms [Citation57]. Tolerating fluctuations in symptoms and the chronicity of the condition, without losing faith was key as described by Zoe, a woman in her 20s with functional movement disorder describing “bad days” that “you don’t like feeling poorly… but you don’t mind them as much now. I think it’s just part of the life now, but then I just enjoy my good days more… I appreciate them more” [Citation56]. Bazydlo and colleagues’ paper [Citation53] also described participants who were involved in raising awareness, education and research contributing to a sense of hope for the future.

Discussion

This review synthesised the experiences of people living with motor and/or sensory FND, including people with PPPD and drop attacks. The analytic themes represent an interaction between body and mind, in relation with self, healthcare professionals and wider society. Central to the experience is uncertainty; about what FND is and questions which follow including what treatment might be available, and how to live with a chronic illness.

Uncertainty, confusion and dualism

Participants described confusion and fear when experiencing symptoms and questioned who or what was responsible for their illness. Rather than receiving a clear and validating explanation from healthcare professionals many found interactions focussed on psychological stressors to the exclusion of other triggers, or were told nothing was wrong. Participants noted the unusual way in which diagnoses were presented, with clinicians at times describing what they didn’t have, rather than what they did, reflecting a departure from the usual process of diagnostic communication in medicine [Citation62]. This appeared to lead to mistrust and lack of confidence in the diagnosis given. Trust was further eroded when lack of biochemical markers led to the doctor’s assertion that the illness had a psychological cause. Some participants described how they felt a physical trigger, such as an injury or surgery had triggered their illness. This is increasingly being recognised in quantitative literature [Citation63] but rarely, if ever contributed to a formulation in interactions described in this study.

A lack of person-centred care has been highlighted in a recent comparison between experiences of patients with MS and FND in the NHS [Citation64]. People with FND reported not being treated with respect or dignity and feeling misunderstood by their doctors significantly more than those with MS. Those with FND also faced more difficulties in accessing specialists, received insufficient information about medication and lack of care coordination. The long journey to diagnosis described by participants in our review is reflected in other studies where mean time of 6.63 years is reported between onset of symptoms and functional motor disorder diagnosis [Citation6].

Studies of clinician views offer a useful perspective on the interactions which are experienced as dismissive and unhelpful by patients. A recent systematic review of healthcare professional experiences described uncertainty at the heart of a “vicious cycle” of lack of education and consensus, negative attitudes, buck passing and avoidance [Citation23]. Clinicians felt unsure about how to diagnose and manage FND, as well as some expressing uncertainty about aetiology, querying malingering and if symptoms were “real.” A lack of education about FND within undergraduate and postgraduate curricula have been highlighted [Citation65]. Additionally, although the diagnosis is increasingly recognised to be reliable and stable, the cause of FND is not fully understood [Citation34]. Various bio-psycho-social models have been hypothesised and suggest FND results from dysfunction of higher-order motor and limbic processes in complex interaction with early life adversity, stress, bodily experiences and expectations [Citation34]. Such a complex, multifactorial and still uncertain pathophysiology creates a challenge in communicating cause in a clinical interaction [Citation13].

However, the lack of education, research and attitudes towards FND are not solely a product of the complexity of the disorder. Structural discrimination, misogyny and stigma play a role in perpetuating the poor outcomes for people with FND. This has been highlighted in a lack of research and grants for FND, compared to other neurological disorders [Citation66, Citation67] and historical factors including stigmatising language such as “psychogenic” and “pseudo” [Citation66]. There is also a fundamental issue of the tendency of medicine to dismiss or attribute emotional causes to symptoms which are unexplained, affecting multiple systems, or occur predominantly in women. Lupus is one of many such examples where patients also frequently face long delays and misdiagnoses [Citation68]. Diagnostic delays and lack of treatment or rehabilitation for FND are likely to contribute to poor outcomes and chronic disability [Citation64] and may understandably lead to disengagement from the health system [Citation67]. The tendency to de-legitimise FND also affects clinician behaviour in the form of fewer referrals for physical therapy compared with MS [Citation69].

Illness perceptions, stigma and the self

Illness perceptions or representations refer to a person’s beliefs about their condition and how much they can influence their recovery [Citation70]. Such perceptions are related to outcomes in many conditions including FND [Citation71, Citation72]. Healthcare professionals have an important role in shaping illness beliefs and helping patients make sense of their symptoms.

A recent paper on stigma in FND describes when healthcare professionals dismiss FND symptoms as “not real” patients feel invalidated, trust is broken and professionals label interactions as “difficult” [Citation67]. Participants in this review described how invalidation not only affected a singular interaction, but was internalised, affecting sense of self, confidence in requesting reasonable adjustments in their employment, access to support and benefits. Disabilities studies experts have described how medical invalidation operates in chronic fatigue syndrome where individuals are portrayed by medicine and the media as not really ill, of deficient character and undeserving of support or disability allowances [Citation73].

A recent meta-synthesis examining stigma in FND found de-legitimization was a key theme, frequently occurring within health care interactions [Citation60]. The authors found stigma also operated through social exclusion, and coping with stigma was an additional burden, leading to a high level of self-blame and effect on identity [Citation60]. In functional seizures experiences of stigma were related to mood, anxiety and seizure frequency [Citation74]. Participants in our review reported concerns about how a label of FND might affect future healthcare interactions, including risk of diagnostic overshadowing, where clinicians might attribute any new symptoms to FND. This concern is shared by 64% of respondents in worldwide study of 501 people conducted by FND Hope [Citation75].

Applications for clinical practice and future research

A virtuous cycle?

Given the central importance of illness explanations, reducing stigma and collaborative healthcare relationships in recovery, does the synthesis offer suggestions as to what would be required for a “virtuous” rather than “vicious” cycle?

Firstly, for participants in this study receiving a diagnosis was perceived as helpful, and often a turning point. FND experts highlight the importance of making a positive diagnosis [Citation62] and transparently using neurological signs to demonstrate clinical reasoning [Citation76]. Humility in doctors was valued by patients in our review; clinicians who believed their symptoms and who would “look it up” even if they were not experts [Citation56]. Although traditionally doctors were expected to fulfil the role of expert, increasingly studies demonstrate clinician humility can predict satisfaction, trust and self-reported health [Citation77]. A meta-analysis of patient trust in healthcare professionals found it to be correlated with satisfaction, health behaviours and reduced symptom severity [Citation78].

Education for doctors, patients and their families clearly has a role in reaching shared understandings and bridging the gulf in communication and validation of FND. Lehn and colleagues developed a brief multidisciplinary course for healthcare professionals which was effective in improving confidence and knowledge in assessing and treating FND, with changes persisting at 6 months [Citation79].

A recent study demonstrated how a multidisciplinary education session utilising a bio-psycho-social explanation for people with FND and families increased ratings of understanding and agreement with diagnosis, belief in treatability and hopefulness about recovery [Citation80]. Although the prognosis for functional motor disorders remains poor overall, early diagnosis, short symptom duration and high satisfaction with care predict a more positive outcome [Citation16].

It is also important to note very few of the participants in this review reported experiences of treatment, likely reflective of the limited, patchy availability of services for people with FND [Citation62]. Given FNDs can be chronic conditions with associated disability, effect on finances and quality of life [Citation30, Citation81], there is a clear role for practical and functional assistance and advice, including from occupational therapy and social workers in FND treatment pathways [Citation82].

Embracing uncertainty and genuine bio-psycho-social models

Addressing the uncertainty of FND could represent a paradigm shift from pathology-focussed, de-contextualised and siloed medicine to rehabilitative, collaborative practice which embraces the fundamentally personal experience of illness [Citation83]. Divisions between mind and brain or brain and body in any branch of medicine rarely meet the needs of patients [Citation83]. Rather than expecting FND to fit a dualistic and simplistic model, we might ask instead what FND could demonstrate about the embodied mind and individual experiences of illness. Findings from research in FND have illuminated brain networks linking emotions to physical states and symptoms in a wide range of disorders, through processes such as interoception, attention [Citation84] and prediction [Citation11].

Key to addressing structural discrimination and stigma is the emerging practice of working jointly with people with lived experience of FND to develop evidence-based treatment pathways and education programmes [Citation67]. Within this review, Bazydlo and colleagues recent paper [Citation50] described the role of education and activism in hope and recovery. Charities such as FND Hope have partnered with academics to research experiences of people with FND [Citation22] and organisations such as the FND Society offer seminars where academics and clinicians teach alongside people with lived experience [Citation85]. Recent guidance from the National Neurosciences Advisory Group reflects collaboration with multiple partners including people with lived experience, to identify an optimum clinical pathway for FND in the UK [Citation44].

Strengths and limitations

This review included only studies available in English, meaning that valuable insights from the non-English speaking countries were excluded. Ethnicity was often not described in the included studies, and where it was reported the majority of participants were White. The experiences of people from minoritized ethnicities are therefore not represented, but also the intersectional aspects which might exacerbate experiences of discrimination such as racism within medicine cannot be explored.

The nature of qualitative synthesis means the results of studies are filtered through the analyses of authors of individual studies. Although our methodology focussed on raw quotes from participants, there may be biases which we cannot be aware of, in study authors’ selection of quotes and interpretations.

Included studies focussed predominantly on a clinical population which means people living with symptoms of FND who are not in contact with healthcare services are unlikely to have their views represented. Further research conducted by charities such as FND Hope, via online global surveys are vital in accessing the experiences of this broader group, especially those let down or harmed by health services.

A strength of the review is the use of two authors to independently screen and extract data, comprehensive search strategy and the involvement of people with lived experience of FND in developing the research question and synthesising results.

Conclusions

This review highlights that people with motor and sensory FND, PPPD and drop attacks experience significant disability, stigma, frequent negative interactions with healthcare professionals and systems, underpinned by uncertainty. This uncertainty is mirrored in and perpetuated by clinical encounters with professionals who lack education on FND and communicate dualistic explanatory models.

The challenge of living with a misunderstood and often invisible illness contributes to isolation and self-blame. Receiving a clear diagnosis of FND was valued as a first step in recovery. However, for participants in this review very little treatment was offered and many felt abandoned.

This review echoes the now widespread guidance from FND experts that making a positive, early diagnosis, offering explanation, validation and hope are vital. Participants in this study identified a need for education for healthcare professionals and the wider community. Education should be co-produced and combine the latest neuroscience and testimonies of people with lived experience. This may improve the doctor-patient relationship, rebuild trust and reduce stigma.

Future research in motor and sensory FND should be also be co-produced, utilise the benefits of qualitative and quantitative methodologies and redress the lack of FND research in comparison with other neurological conditions. Studies should focus on answering questions meaningful to people living with FND, including generating evidence on early intervention and opportunities for greater multidisciplinary treatment, support and validation for FND as a potentially chronic and disabling condition. Such research should explicitly seek the views of the many patients who have been unable to access diagnosis and treatment, those who have been harmed and from minoritized ethnicities.

FND is common and disabling and urgently deserves parity with other chronic neurological conditions. Rather than being seen as a “unicorn condition” FND could represent an opportunity for researchers and clinicians to apply new understandings of the neuroscience of emotions and the embodied mind. Embracing the uncertainty and complexity of FND could offer a blueprint for collaborative pathways which truly address the bio-psycho-social needs of patients experiencing a wide variety of illnesses.

Statement of ethics

Ethical approval not required because this study retrieved and synthesised data from already published studies.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (133.6 KB)Disclosure statement

CB’s MD(Res) degree is supported by a scholarship from Mental Health Research UK. MJE was co-author of Neilsen et al. paper [Citation56] but did not participate in quality assessment of papers. MJE does medical expert reporting in personal injury and clinical negligence cases, including in cases of functional neurological disorder. MJE has shares in Brain and Mind Ltd which provides neuropsychiatric and neurological rehabilitation in the independent medical sector, including in people with functional neurological disorder. MJE has received financial support for lectures from the International Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Society and the Functional Neurological Disorder Society. MJE receives Royalties from the Oxford University Press for his book: The Oxford Specialist Handbook of Parkinson’s Disease and Other Movement Disorder. MJE receives grant funding, including for studies related to functional neurological disorder, from NIHR and the MRC. MJE is an associate editor of the European Journal of Neurology.

References

- Stone J, Burton C, Carson A. Recognising and explaining functional neurological disorder. BMJ. 2020;371:m3745. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3745.

- Daum C, Hubschmid M, Aybek S. The value of ‘positive’ clinical signs for weakness, sensory and gait disorders in conversion disorder: a systematic and narrative review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):180–190. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-304607.

- Carson A, Lehn A. Chapter 5 - epidemiology. In: Hallett M, Stone J, Carson A, editors. Handbook of clinical neurology: functional neurologic disorders. 1st ed. London: Elsevier; 2016. p. 47–60.

- Ahmad O, Ahmad KE. Functional neurological disorders in outpatient practice: an Australian cohort. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;28:93–96. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2015.11.020.

- Stone J, Carson A, Duncan R, et al. Who is referred to neurology clinics? - The diagnoses made in 3781 new patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112(9):747–751. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.05.011.

- Tinazzi M, Gandolfi M, Landi S, et al. Economic costs of delayed diagnosis of functional motor disorders: preliminary results from a cohort of patients of a specialized clinic. Front Neurol. 2021;12:786126. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.786126.

- Cock HR, Edwards MJ. Functional neurological disorders: acute presentations and management. Clin Med. 2018;18(5):414–417. www.neurosymptoms.org.

- Reuber M. Trauma, traumatisation, and functional neurological symptom disorder—what are the links? Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(4):288–289. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30101-9.

- Ding JM, Kanaan RAA. Conversion disorder: a systematic review of current terminology. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;45:51–55. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.12.009.

- Espay AJ, Aybek S, Carson A, et al. Current concepts in diagnosis and treatment of functional neurological disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1132–1141. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1264.

- Edwards MJ, Adams RA, Brown H, et al. A Bayesian account of ‘hysteria’. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 11):3495–3512. doi:10.1093/brain/aws129.

- Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, et al. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74(3):223–228. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ca00e9.

- Fobian AD, Elliott L. A review of functional neurological symptom disorder etiology and the integrated etiological summary model. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019;44(1):8–18. doi:10.1503/jpn.170190.

- Ludwig L, Pasman JA, Nicholson T, et al. Stressful life events and maltreatment in conversion (functional neurological) disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(4):307–320. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30051-8.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Gelauff J, Stone J, Edwards M, et al. The prognosis of functional (psychogenic) motor symptoms: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):220–226. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2013-305321.

- Carson A, Stone J, Hibberd C, et al. Disability, distress and unemployment in neurology outpatients with symptoms ‘unexplained by organic disease’. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(7):810–813. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2010.220640.

- Demartini B, Batla A, Petrochilos P, et al. Multidisciplinary treatment for functional neurological symptoms: a prospective study. J Neurol. 2014;261(12):2370–2377. doi:10.1007/s00415-014-7495-4.

- Petrochilos P, Elmalem MS, Patel D, et al. Outcomes of a 5-week individualised MDT outpatient (day-patient) treatment programme for functional neurological symptom disorder (FNSD). J Neurol. 2020;267(9):2655–2666. doi:10.1007/s00415-020-09874-5.

- Beal EM, Coates P, Pelser C. Psychological interventions for treating functional motor symptoms: a systematic scoping review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;94:102146. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102146.

- Perez DL, Edwards MJ, Nielsen G, et al. Decade of progress in motor functional neurological disorder: continuing the momentum. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92(6):668–677. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2020-323953.

- Butler M, Shipston-Sharman O, Seynaeve M, et al. International online survey of 1048 individuals with functional neurological disorder. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(11):3591–3602. doi:10.1111/ene.15018.

- Barnett C, Davis R, Mitchell C, et al. The vicious cycle of functional neurological disorders: a synthesis of healthcare professionals’ views on working with patients with functional neurological disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;44(10):1802–1811. doi:10.1080/09638288.2020.1822935.

- FND Hope. International Survey. FND Hope Research. https://fndhope.org/fnd-hope-research/. https://fndhope.org/fnd-hope-research/.

- Rommelfanger KS, Factor SA, LaRoche S, et al. Disentangling stigma from functional neurological disorders: conference report and roadmap for the future. Front Neurol. 2017;8(MAR):106. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00106.

- Todres L, Galvin KT, Holloway I. The humanization of healthcare: a value framework for qualitative research. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2009;4(2):68–77. doi:10.1080/17482620802646204.

- Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):59. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-9-59.

- Seers K. Qualitative systematic reviews: their importance for our understanding of research relevant to pain. Br J Pain. 2015;9(1):36–40. doi:10.1177/2049463714549777.

- Rawlings GH, Reuber M. What patients say about living with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a systematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Seizure. 2016;41:100–111. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2016.07.014.

- Stone J, Sharpe M, Rothwell PM, et al. The 12 year prognosis of unilateral functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(5):591–596. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.5.591.

- Baker J, Barnett C, Cavalli L, et al. Management of functional communication, swallowing, cough and related disorders: consensus recommendations for speech and language therapy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92(10):1112–1125. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2021-326767.

- Hoeritzauer I, Carson AJ, Stone J. Cryptogenic Drop Attacks’ revisited: evidence of overlap with functional neurological disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(7):769–776. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-317396.

- Dieterich M, Staab JP. Functional dizziness: from phobic postural vertigo and chronic subjective dizziness to persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. Curr Opin Neurol. 2017;30(1):107–113. https://journals.lww.com/co-neurology/Fulltext/2017/02000/Functional_dizziness__from_phobic_postural_vertigo.16.aspx doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000417.

- Pick S, Goldstein LH, Perez DL, et al. Emotional processing in functional neurological disorder: a review, biopsychosocial model and research agenda. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(6):704–711. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2018-319201.

- Popkirov S, Staab JP, Stone J. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): a common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(1):5–13. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2017-001809.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

- Bailey C, Tamasauskas A, Bradley-Westguard A, et al. PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews lived experience of motor and sensory functional neurological symptoms: a systematic review of qualitative studies Citation. 2021. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021293759.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-181.

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, et al. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):579. doi:10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0.

- Carson AJ, Ringbauer B, Stone J, et al. Do medically unexplained symptoms matter? A prospective cohort study of 300 new referrals to neurology outpatient clinics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(2):207–210.

- Carson AJ, Brown R, David AS, et al. Functional (conversion) neurological symptoms: research since the millennium. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(8):842–850. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2011-301860.

- NNAG. Optimum clinical pathway for adults: Functional Neurological Disorder National Neurosciences Advisory Group (NNAG). 2023. www.nnag.org.uk/optimum-clinical-pathways.

- Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, et al. PRISMA2020: an R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev. 2022;18(2):e1230. doi:10.1002/cl2.1230.

- Sezier AEI, Saywell N, Terry G, et al. Working-age adults’ perspectives on living with persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: a qualitative exploratory study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(4):e024326. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024326.

- Herdman D, Evetovits A, Everton HD, et al. Is ‘persistent postural perceptual dizziness’ a helpful diagnostic label? A qualitative exploratory study. VES. 2021;31(1):11–21. doi:10.3233/VES-201518.

- Brenninkmeijer J. Conversion disorder and/or functional neurological disorder: how neurological explanations affect ideas of self, agency, and accountability. History of the Hum Sci. 2020;33(5):64–84. doi:10.1177/0952695120963913.

- Revell ER, Gillespie D, Morris PG, et al. Drop attacks as a subtype of FND: a cognitive behavioural model using grounded theory. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2021;16:100491. doi:10.1016/j.ebr.2021.100491.

- Bazydlo S, Eccles FJR. Living with functional movement disorders: a tale of three battles. An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychol Health. 2022;30:1–18. doi:10.1080/08870446.2022.2130312.

- Dosanjh M, Alty J, Martin C, et al. What is it like to live with a functional movement disorder? An interpretative phenomenological analysis of illness experiences from symptom onset to post-diagnosis. Br J Health Psychol. 2021;26(2):325–342. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12478.

- Epstein SA, Maurer CW, LaFaver K, et al. Insights into chronic functional movement disorders: the value of qualitative psychiatric interviews. Psychosomatics. 2016;57(6):566–575. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2016.04.005.

- Gamble R, Sumner P, Wilson-Smith K, et al. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis to probe the lived experiences of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD). J Vestib Res. 2023;33(2):89–103. doi:10.3233/ves-220059.

- Monzoni CM, Duncan R, Grünewald R, et al. Are there interactional reasons why doctors may find it hard to tell patients that their physical symptoms may have emotional causes? A conversation analytic study in neurology outpatients. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):e189–e200. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.014.

- Nettleton S, Watt I, O’Malley L, et al. Understanding the narratives of people who live with medically unexplained illness. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(2):205–210. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.010.

- Nielsen G, Buszewicz M, Edwards MJ, et al. A qualitative study of the experiences and perceptions of patients with functional motor disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(14):2043–2048. doi:10.1080/09638288.2018.1550685.

- O’Connell N, Jones A, Chalder T, et al. Experiences and illness perceptions of patients with functional symptoms admitted to hyperacute stroke wards: a mixed-method study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:1795–1805. doi:10.2147/NDT.S251328.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP qualitative studies checklist. p. 1–6. [Cited 2023 Aug 21]. www.casp-uk.net.

- Njau B, Covin C, Lisasi E, et al. A systematic review of qualitative evidence on factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV self-testing in Africa. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1289. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7685-1.

- Foley C, Kirkby A, Eccles FJR. A meta-ethnographic synthesis of the experiences of stigma amongst people with functional neurological disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;46(1):1–12. doi:10.1080/09638288.2022.2155714.

- Busetto L, Wick W, Gumbinger C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol Res Pract. 2020;2(1):14. doi:10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z.

- Carson A, Lehn A, Ludwig L, et al. Explaining functional disorders in the neurology clinic: a photo story. Pract Neurol. 2016;16(1):56–61. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2015-001242.

- Geroin C, Stone J, Camozzi S, et al. Triggers in functional motor disorder: a clinical feature distinct from precipitating factors. J Neurol. 2022;269(7):3892–3898. doi:10.1007/s00415-022-11102-1.

- O’Keeffe S, Chowdhury I, Sinanaj A, et al. A service evaluation of the experiences of patients with functional neurological disorders within the NHS. Front Neurol. 2021;12:656466. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.656466.

- Hutchinson G, Linden SC. The challenge of functional neurological disorder – views of patients, doctors and medical students. JMHTEP. 2021;16(2):123–138. doi:10.1108/JMHTEP-06-2020-0036.

- McLoughlin C, Hoeritzauer I, Cabreira V, et al. Functional neurological disorder is a feminist issue. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2023;94(10):855–862. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2022-330192.

- MacDuffie KE, Grubbs L, Best T, et al. Stigma and functional neurological disorder: a research agenda targeting the clinical encounter. CNS Spectr. 2021;26(6):1–6. doi:10.1017/S1092852920002084.

- Sloan M, Harwood R, Sutton S, et al. Medically explained symptoms: a mixed methods study of diagnostic, symptom and support experiences of patients with lupus and related systemic autoimmune diseases. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2020;4(1):rkaa006. doi:10.1093/rap/rkaa006.

- Begley R, Farrell L, Lyttle N, et al. Clinicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about the legitimacy of functional neurological disorders correlate with referral decisions. Br J Health Psychol. 2023;28(2):604–618. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12643.

- Whitehead K, Stone J, Norman P, et al. Differences in relatives’ and patients’ illness perceptions in functional neurological symptom disorders compared with neurological diseases. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;42:159–164. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.10.031.

- Williams IA, Morris PG, McCowat M, et al. Factors associated with illness representations in adults with epileptic and functional seizures: a systematic review. Seizure. 2023; 106:39–49. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2023.01.016.

- Pick S, Anderson DG, Asadi-Pooya AA, et al. Outcome measurement in functional neurological disorder: a systematic review and recommendations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(6):638–649. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2019-322180.

- Hunt JE. Towards a critical psychology of chronic fatigue syndrome: biopsychosocial narratives and UK welfare reform. J Crit Psychol Counsel Psychother. 2022;22(1):18–28. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361017759.

- Rawlings GH, Brown I, Reuber M. Deconstructing stigma in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: an exploratory study. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;74:167–172. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.06.014.

- FNDHope. FND hope stigma survey. 2021. https://fndhope.org/fnd-hope-research/.

- Stone J, Edwards M. Trick or treat?: Showing patients with functional (psychogenic) motor symptoms their physical signs. Neurology. 2012;79(3):282–284. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825fdf63.

- Huynh HP, Dicke-Bohmann A. Humble doctors, healthy patients? Exploring the relationships between clinician humility and patient satisfaction, trust, and health status. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(1):173–179. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.07.022.

- Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, et al. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170988. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170988.

- Lehn A, Navaratnam D, Broughton M, et al. Functional neurological disorders: Effective teaching for health professionals. BMJ Neurol Open. 2020;2(1):e000065. doi:10.1136/bmjno-2020-000065.

- Cope SR, Smith JG, Edwards MJ, et al. Enhancing the communication of functional neurological disorder diagnosis: a multidisciplinary education session. Eur J Neurol. 2020;28(1):40–47. doi:10.1111/ene.14525.

- Sharpe M, Stone J, Hibberd C, et al. Neurology out-patients with symptoms unexplained by disease: illness beliefs and financial benefits predict 1-year outcome. Psychol Med. 2010;40(4):689–698. doi:10.1017/S0033291709990717.

- Gardiner P, Macgregor L, Carson A, et al. Occupational therapy for functional neurological disorders: a scoping review and agenda for research. CNS Spectr. 2018;23(3):205–212. doi:10.1017/S1092852917000797.

- Edwards MJ. Functional neurological disorder: lighting the way to a new paradigm for medicine. Brain. 2021;144(11):3279–3282. doi:10.1093/brain/awab358.

- Cretton A, Brown RJ, Lafrance WC, et al. What does neuroscience tell us about the conversion model of functional neurological disorders? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;32(1):24–32. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19040089.

- FND Society. Virtual education and webinars. [cited 2023 Aug 7]. https://www.fndsociety.org/fnd-education/virtual-education-course/lectures