Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate short-term effects of the PREVention of Sickness Absence for Musculoskeletal disorders (PREVSAM) model on sickness absence and patient-reported health outcomes.

Methods

Patients with musculoskeletal disorders were randomised to rehabilitation according to PREVSAM or treatment as usual (TAU) in primary care. Sickness absence and patient-reported health outcomes were evaluated after three months in 254 participants.

Results

The proportion of participants remaining in full- or part-time work were 86% in PREVSAM vs 78% in TAU (p = 0.097). The PREVSAM group had approximately four fewer sickness benefit days during three months from baseline (p range 0.078–0.126). No statistically significant difference was found in self-reported sickness absence days (PREVSAM 12.4 vs TAU 14.5; p = 0.634), nor were statistically significant differences between groups found in patient-reported health outcomes. Both groups showed significant improvements from baseline to three months, except for self-efficacy, and only the PREVSAM group showed significantly reduced depression symptoms.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that for sickness absence, the PREVSAM model may have an advantage over TAU, although the difference did not reach statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level, and similar positive effects on patient-reported health outcomes were found in both groups. Long-term effects must be evaluated before firm conclusions can be drawn.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Early identification of at-risk patients and team-based rehabilitation within primary care to prevent sickness absence and long-term problems due to acute/subacute musculoskeletal disorders has been scarcely studied.

The PREVSAM model provides a framework for team-based interventions in primary care rehabilitation.

The PREVSAM model may be used in the management of acute/subacute musculoskeletal disorders in the prevention of sickness absence.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorder (MSD) is a term frequently used to describe a broad range of conditions with musculoskeletal pain and decreased physical function that are very common in the general population. It was estimated in 2019 that over one billion adults globally have an MSD that would benefit from rehabilitation [Citation1]. Even though acute episodes of MSD usually improve rapidly, recurrences are common and approximately 25% of adult patients’ primary care consultations are due to MSDs of any type [Citation2].

First line treatment for MSD is suggested to be self-management advice, exercise therapy, and psychosocial interventions and MSDs are to a large extent managed in primary care [Citation3,Citation4]. Physiotherapy is suggested as first line treatment for MSD when self-management is not enough [Citation5]. The aim of physiotherapy is: to promote health; prevent illness and injuries; and maintain, regain and maximise optimal movement potential, health-related quality of life, and participation in social life [Citation6]. Physiotherapists as primary assessors for MSDs in primary care has at least as positive health effects as general practitioners [Citation7]. Moreover, patients with MSD have reported high satisfaction with physiotherapy as a first line treatment [Citation8].

Several consistent recommendations have been identified that could be used as guidelines in MSD care, for example a person-centred approach, a clinical examination, assessing psychosocial factors and work-related issues [Citation9]. A biopsychosocial approach is recommended when explaining development of chronic pain [Citation10] and work-related causes for MSD [Citation11]. Work activities and work conditions can contribute both to the onset and progression of pain problems. One of the most common causes for work disability and sickness absence is MSDs, in Sweden representing about 17% of all sick leave in January 2023 [Citation12]. The initial intensity of pain itself did not seem to be related to the likelihood for extended pain duration or for sickness absence in a group of patients with neck and low back pain [Citation13]. Nor did pain itself correlate with work engagement, i.e., experienced work ability and occupational satisfaction, in women with MSD, while psychosocial and lifestyle factors significantly correlated with work engagement [Citation14]. Comorbidity with anxiety, depression, and stress-related conditions is common when having chronic pain [Citation15]. Therefore, the need for screening for risk factors and prevention of long-term disability is essential to reduce individual suffering and sickness absence. Early interventions may also reduce societal costs for medical care, reduced work ability and sickness benefits.

Obstacles towards why physiotherapists within primary care may not always discuss work-related factors with the patient have been identified. It may be due to the belief that assessing work-related issues is not the physiotherapist’s responsibility, perceived lack of competence, or organisational factors [Citation16]. A lack of clarity about occupational health and a wish for guidelines for work-related issues have been reported among physiotherapists [Citation17]. Moreover, even though patients find it important to address work issues with their physiotherapists, they may not raise the issue themselves [Citation18]. Therefore, it is important that health professionals prioritise discussing this topic with patients. Clinical guidelines for optimising work participation suggest that patient management involve: a strong therapeutic alliance with therapist-patient agreement on goals and interventions; a physical performance examination; an individual treatment plan; screening of psychosocial risk factors and work demand; and, if needed, communication with the workplace [Citation19]. Dropkin et al. recommend prompt treatment of work-related MSD using an extended team within primary care in cooperation with the patient’s employer [Citation20]. Involving work-related factors is important as, in Sweden, employers have responsibility for the work environment regulated in law [Citation21]. An early workplace dialogue, in addition to structural physiotherapy for MSD patients in primary care, has been shown to improve work ability statistically significantly compared to a control group [Citation22]. Moreover, workplace interventions, service coordination to ensure communication among different stakeholders and interventions to improve the patients’ health conditions are recommended [Citation23].

To facilitate identifying those at risk for long-term pain problems, screening tools have been developed to identify psychological factors which may increase the risk for sickness absence in those with MSD [Citation24]. The prognostic screening tool Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire in an original version (ÖMPSQ) [Citation25] and a short form, ÖMPSQ-SF [Citation26], are predominant in the literature. The instrument has been shown to be ‘excellent’ to identify risk for prolonged absenteeism due to low back pain [Citation24]. Fear of pain or reinjury, beliefs in severity of health conditions, catastrophising, depression, poor problem solving, low return-to-work expectancies and lack of confidence in performing work-related activities are risk factors for long-term work disability. However, it is important to bear in mind that psychological risk factors covariate with other risk factors such as older age, physically demanding work, societal factors such as social isolation, and reimbursement systems [Citation27].

Interdisciplinary treatment is recommended for rehabilitation of chronic pain, with teams consisting of at least three different health professions with a biopsychosocial understanding of the patient’s pain problem [Citation28]. Physiotherapy and occupational therapy are common within rehabilitation for chronic pain in primary care together with psychological treatment [Citation29]. The disciplines have a holistic view on the patient and contribute to the rehabilitation of MSD with different perspectives [Citation6,Citation30]. In occupational therapy, activities and occupations are core components with the aims to clarify the physical, emotional, cognitive and social demands of activities and occupations [Citation30].

In summary, evidence suggests identifying vulnerable subgroups to initiate secondary prevention of pain with a biopsychosocial and person-centred approach before a transition towards persistent pain and a disability state may occur [Citation9,Citation27,Citation31]. To meet these requirements, and hereby aiming to reduce individual suffering and societal costs, the rehabilitation model “Prevention of sickness absence through early identification and rehabilitation of at-risk patients with MSD” (PREVSAM) was designed [Citation32]. The PREVSAM model’s purpose is to prevent sickness absence and development of persistent pain in a group of patients with MSD who have been identified to be at risk for sickness absence. Levels of psychosocial problems and the way they influence personal pain conditions need to be identified and assessed to provide targeted interventions to patients with MSD in primary care rehabilitation [Citation33]. Furthermore, it must be clear when the patient can effectively be treated within primary care rehabilitation, and when more specialised psychological support is needed [Citation34]. For those at risk, the PREVSAM model’s interdisciplinary teamwork intends to provide targeted interventions for the MSD and for psychosocial factors, including work-related factors, and hereby prevent development of long-term problems and sickness absence.

The study hypothesis was that, in a short-term perspective (three months), early identification of risk factors and rehabilitation according to the PREVSAM model would be more effective than treatment as usual (TAU) in prevention of sickness absence and in improving health-related outcomes in at-risk patients with MSDs.

The overall aim of this study was to evaluate the trial’s short-term effects (three months) of the PREVSAM model on sickness absence and patient-reported health outcomes. Specific aims were: (1) to evaluate the proportion of patients remaining at work, number of sickness benefit days, and self-reported sickness absence and (2) to evaluate patient-reported outcomes: psychological risk factors associated with sickness absence, perceived work ability, physical disability, pain status, symptoms of anxiety and depression, general and pain self-efficacy, and health-related quality of life.

Materials and methods

Study design

A two-armed randomised controlled trial evaluating the effects of the PREVSAM model compared with TAU. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, Protocol ID: NCT03913325. This article presents three months’ follow-up results of sickness absence and patient-reported work ability and health outcomes. Findings are reported according to the CONSORT Checklist.

Setting

The trial was mainly conducted at public and private primary care rehabilitation clinics from May 2019 to June 2023 in Sweden’s second largest regional council Region Västra Götaland, which provides healthcare services to 1.7 million inhabitants. In the region, all existing public rehabilitation clinics and most private rehabilitation clinics within the reimbursement system “Care choice rehabilitation” were informed about the trial through managements team contacts and were invited to participate. The “Care choice” means that patients choose preferred rehabilitation clinic, and no referral is needed. The smaller Region Värmland was also invited which, like the Region Västra Götaland, has open access with equal conditions for public and private rehabilitation clinics.

Participants

Eligible participants were adults of working age, (aged ≥18 years, not fully retired) with MSD lasting less than three months. They were invited to participate when seeking care from a primary rehabilitation clinician for their MSD, if they scored 40 points or more on the ÖMPSQ-SF which indicate increased risk for sickness absence. Having a paid job or receiving parental benefits, unemployment benefits, or student aid were mandatory.

Exclusion criteria were “red flags” indicating risk of serious pathology, pain not primarily generated from the musculoskeletal system, severe mental illness, ongoing substance abuse disorders, pregnancy, being on sick leave due to the MSD for more than a month during the last year, fully retired or full disability pension, or inadequate Swedish literacy for the trial’s questionnaires.

Participants were told that the trial compared TAU with a more extensive team-based rehabilitation and were aware of their group allocation.

Procedure of randomisation

Participants were recruited and randomised at the rehabilitation clinic either at their first visit or by telephone a few days later by the responsible physiotherapist or occupational therapist. The participants were allocated by sealed opaque envelopes to either PREVSAM or TAU. Block-randomisation made by a computer programme in blocks of six (three of each) was used.

Treatment provided

Differences and similarities regarding treatment provided are presented in for the PREVSAM model and TAU.

Table 1. The PREVSAM model’s components and differences towards treatment as usual within primary care rehabilitation.

The PREVSAM model

Both pragmatic and theoretical considerations guided the design of the PREVSAM model, for the primary care setting [Citation32]. The PREVSAM model requires early identification of psychological risk factors and interdisciplinary teamwork with a person-centred approach (). The physiotherapist and the occupational therapist make their individual assessments and, based on these assessments and a biopsychosocial understanding of the patient’s situation, the health care professionals and the patient establish a joint individual health plan. Listening to the patients’ narrative, identifying important elements and their priorities, and discussing healthy lifestyle behaviours are emphasised. The health plan should include the patient’s goals and be inspired by the “SMART” approach, i.e., be specific, measurable/meaningful, achievable/activity-based, realistic/relevant and timed [Citation35]. Moreover, clarifying of responsibilities and whether other contacts need to be made, such as with a psychotherapist or the workplace, are documented in the health plan. If needed, the patient’s general practitioner is contacted for medical assessment. The PREVSAM model provides a framework for team-based rehabilitation. Therefore, treatments to be provided are not specified. The rehabilitation should comprise evidence-based treatments commonly used in primary care rehabilitation.

Treatment as usual

In the control group, TAU, mainly physiotherapy treatment is provided within primary care, but occupational therapy may also be provided. The physiotherapist and/or occupational therapist responsible for the patient’s care use evidence-based interventions and provide sessions in line with their clinical judgement and available resources.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was sickness absence, measured by collecting registry data on sickness benefits days from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA) and by patient-reported data.

Sickness absence is defined as “absence from work that is attributed to sickness by the employee and accepted as such by the employer” [Citation36]. In Sweden, the employee or the employer are liable for the costs of short-time sickness absence, the employee for one qualification day and the employer for the remaining days of the first two weeks. Periods longer than two weeks are compensated by the tax-funded social security system through sickness benefits from SSIA.

However, in Sweden, all residents with an income are insured by the Swedish sickness insurance system [Citation37]. The income may come from salary, parental benefit, student aid, or unemployment benefit. This means that it is not mandatory to be employed to be eligible for sickness benefits. When sick and not being able to take care of children, study or actively seek a new job it is thus possible to apply for sickness benefits. A doctor’s certificate is mandatory to apply for sickness benefits.

Sickness benefit days data on the individual level (including diagnoses) were provided by the SSIA for sick-leave spells longer than 14 days. Data for number of gross and net sickness benefit days during the three months’ follow-up period were retrieved from the MicroData for Analysis of Social insurance (MiDAS) database. According to the funder’s request, we followed the outcome measures in the Social Insurance Report 2016:9 [Citation38].

Responses to weekly sent text messages via mobile phone (SMS-Track ApS, Denmark, www.sms-track.com) were used to measure self-reported sickness absence. Validity and reliability of text messaging for research data collection have been established [Citation39]. The participants were asked to answer the question “Have you been absent from work during the past week due to your musculoskeletal pain, and if so for how many days?” and to enter a number from 0 to 7. They were informed that the number of days was regardless of whether they were absent the whole day or part of the day.

Self-reported sickness absence via SMS-track and sickness benefit days were operationalised as number and proportion of individuals with and/or without sickness absence during the follow-up period.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were patient-reported work ability and the health outcomes listed below. To collect the patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), an e-mail with a unique link to a web-based survey (esMaker.net, ©Entergate, Halmstad, Sweden) was sent to the participant at inclusion (baseline), and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after inclusion. The data collected at inclusion (baseline), and at three months after inclusion were used in this short-term follow-up.

Patient-reported risk associated with sickness absence

The instrument ÖMPSQ-SF was used primarily as a screening instrument. It was filled out at the first visit to either a physiotherapist or an occupational therapist, at the rehabilitation centre, for screening and this measure was used as baseline for those accepting to participate in the trial. It was included in the web-based survey’s follow-ups. ÖMPSQ-SF consists of ten items. The first item refers to duration of pain. The following 9 items each contain a statement or an assertion to be rated on an 11-point Likert scale from 0 = absence of impairment, to 10 = severe impairment, however three items are reversed [Citation26]. The ÖMPSQ-SF was also used as a secondary outcome measure to evaluate changed risk associated with sickness absence, including proportion lowering their risk by scoring <40p at follow-up. Validity and reliability of the instrument have been established [Citation25].

Patient-reported work ability

Work Ability Score (WAS) is a single-item question of the Work Ability Index (WAI), “current work ability compared with the lifetime best.” The participant is asked to rate his/her current work ability compared to his/her lifetime best on a 11-point Likert scale anchored by 0 = “Cannot work at all” and 10 = “My ability to work is at its best.” This question has been found to correspond well to WAI categories of the valid and reliable full instrument [Citation40].

Patient-reported physical disability

The Disability Rating Index (DRI), is a self-assessment measure of experienced physical disability in patients with MSDs. It includes twelve everyday activities that most people perform or can imagine. The questions are arranged in order of increasing physical demands, where the participants mark on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) in accordance with her/his presumed ability to perform the daily physical activities in question. The anchor points are 0 = “without difficulty” and 100 = “not at all.” The total score (index) is the mean of all 12 items. The instrument has shown good reliability, validity and responsiveness [Citation41].

Patient-reported pain status

Pain intensity during the previous seven days was measured using an 11-point numeric rating scale (PNRS) anchored by 0 = “no pain at all” and 10 = “worst imaginable pain.” To measure self-reported pain, the PNRS has been shown to have better responsiveness, ease of use, compliance rate and applicability compared to a visual analogue scale and a verbal rating scale [Citation42]. Even though PNRS is recommended and widely used to measure pain intensity, inconsistent results for measurement properties are reported [Citation43]. Pain frequency during the previous week was measured using a four-point Likert scale from 1 = “always/nearly always” to 4 = “rarely.”

Patient-reported pain self-efficacy

PSEQ-2 is a two-item short form of the Pain Self-Efficacy Scale (PSEQ), which is a valid, reliable and well-established measure of changes of beliefs held regarding the possibility to carry out certain activities despite pain [Citation44]. From 0 = “not at all confident” to 6 = “completely confident” is rated on a seven-point Likert scale. PSEQ-2 is translated into Swedish, PSEQ-2SV and culturally adapted [Citation45].

Patient-reported general self-efficacy

The General Self-Efficacy scale (GSE) assess the strength of an individual’s belief in his/her own ability to respond to difficult situations and to execute a course of action to a desired outcome [Citation46]. It consists of 10 items rated on a four-point Likert scale from 1 = “not at all true” to 4 = “exactly true.” The Swedish translation of the GSE has proven to be a valid and reliable indicator of perceived general self-efficacy [Citation47].

Patient-reported anxiety and depression symptoms

The HADS is a validated 14-item measure of self-reported symptoms of anxiety (7 items) and depression (7 items) [Citation48,Citation49]. Each item is scored from 0 to 3, where 0 = “indicating absence of symptoms or presence of positive features” and 3 = “maximal presentation of symptoms or the absence of positive features.”

Patient-reported health-related quality of life

The European Quality of Life, EQ VAS, is a validated measure to assess health-related quality of life [Citation50,Citation51]. EQ VAS is a vertical scale anchored between 0 = the “worst imaginable health” and 100 = the “best imaginable health.”

Baseline measurements

Data regarding age, sex, marital status, income and place of birth were retrieved from the web-based survey, while diagnoses were collected from the interdisciplinary team at each rehabilitation clinic.

Data analysis and statistical methods

Analysis was by intention to treat. Descriptive data are presented as mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and number and percentage for categorical variables. Between-group comparisons were analysed using the tests Mann-Whitney U test, independent t-test and chi-square test, depending on data level. Within-group comparisons were calculated with the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. For all comparisons, differences where p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28.0.1.1.

Results

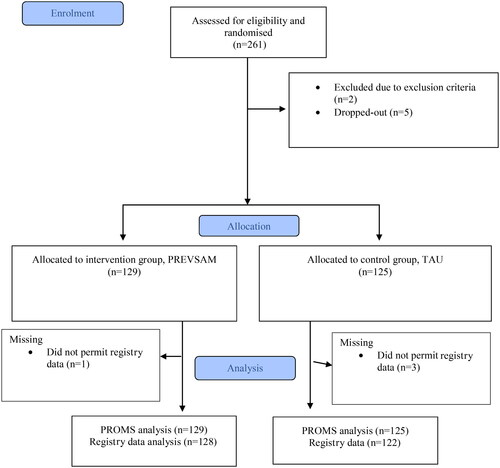

Eight rehabilitation clinics participated in the trial. Four clinics were located in a larger city, one in a small town, and the remaining three in rural municipalities within commuting distance (about 30–60 km) from the big city. Half of the clinics were smaller with about 10 employees, while the others were bigger with about 20 employees or more. A total of 261 patients were recruited and randomised to either the PREVSAM intervention or TAU. The external dropouts consisted of 7 patients (). From the remaining 254 participants, 129 in the PREVSAM group and 125 in TAU, data on background characteristics and treatment provided were collected, and short-term data from baseline to three months from SMS-track and PROMs were analysed. Four participants did not permit data to be retrieved from the MiDAS database. Results from the remaining 250 participants, 128 in the PREVSAM group and 122 in TAU, were analysed regarding sickness absence data from SSIA from baseline to three months. The response rate for the web-based survey was 98,5% at baseline and 82,9% at the three months follow-up. However, all PROMs were not always answered leading to additional missing data.

Figure 1. Flow chart of participants’ enrolment and allocation.

Description of participants

There were no statistically significant differences between the PREVSAM group and TAU at baseline regarding characteristics ( and ) except for occupations. The classification of occupation was made according to the Swedish Standard Classification of Occupations 2012 (SSYK 2012) based on the participants’ description of the work they do [Citation52]. More participants in the PREVSAM group described work classified as managers or requiring advanced level of higher education. On the other hand, in the TAU group, more participants described having potentially more physically demanding work.

Table 2. Baseline demographics regarding sex, place of birth, marital status/living situation, and age.

Table 3. Baseline demographics regarding education level, occupation, and income.

The team members reported the diagnoses according to ICD-10 they used in their medical records, and each patient had from one up to five diagnoses (). To have an MSD was mandatory and subsequently the most common was having an M diagnosis, i.e., “Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue.” MSD can also be caused by injuries and classified with an S diagnosis; “Injuries, poisonings, and certain other consequences of external causes.” When pain is unspecified, the R diagnoses “Symptoms, signs of disease and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings not elsewhere classified” were used. B and G diagnoses, such as late effects of polio and myotonic diseases, were rare forms of MSD. Even though the inclusion criteria were to have psychological risk factors according to the ÖMPSQ-SF, the use of F diagnoses “Mental and behavioural disorders” was relatively low in both groups while the use of Z diagnoses “Factors of importance for the state of health and for contacts with health care” was more common in the intervention group compared to the control group. A few participants had H diagnoses as well because of vertigo and G diagnosis because of tension type headache.

Table 4. ICD-10 diagnoses reported by the team members in the PREVSAM group and in TAU.

The diagnoses reported by the team members were not always equal to the diagnoses the physicians had used in the sickness certificate found in the MiDAS database. The differences may be due to another reason when seeking care or a change in condition as the diagnoses were set at different times and/or professional differences in which diagnoses are used. Sickness absence from the database were analysed in three rounds; first only sickness absence because of diagnoses related to the musculoskeletal system, i.e., M and S diagnoses was analysed. In the next round, F and R diagnoses were added. In the final step, all sickness absence was analysed regardless of the reason.

Primary outcome

Data on sickness benefit days from the SSIA were clearly skewed as most of the participants did not have any registered sick leave days for the three months following baseline. In the PREVSAM group, 86%–79% remained in full- or part-time work, compared with 78%–70% in TAU (at most 27 cases with sickness benefit days compared to 36 cases, respectively), not reaching statistically significant differences between the groups at p < 0.05. See for proportions and confidence intervals. There were approximately four more gross and net sickness benefits days in TAU, but the difference between groups was not statistically significant ().

Table 5. Comparison of proportions of patients remaining in full- and part time work (no registered sickness benefit days) between the PREVSAM group and TAU.

Table 6. Comparisons of registered sickness benefit days between the PREVSAM group and TAU.

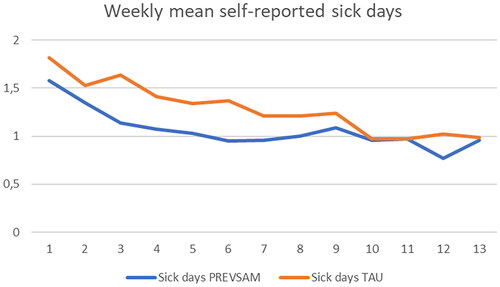

Self-reported sickness absence registered weekly by SMS-track was clearly skewed with approximately half the participants reporting no absence (). Slightly more patients in the PREVSAM group than in TAU reported sickness absence, but the mean number of self-reported sickness days was higher in the TAU group ( and ). None of the differences were statistically significant.

Table 7. Comparison of proportion of patients with self-reported sickness absence between the PREVSAM group and TAU.

Table 8. Comparison of self-reported sickness absence days between the PREVSAM group and TAU.

Weekly self-reported sickness absence is shown in for both groups. Most sickness absence was reported at the beginning of the study period. Missing values were common and slightly more frequent in TAU than in PREVSAM, with 51% and 48%, respectively, having one or more missing weekly reports (p = 0.201). Data from the Social Insurance Agency was imputed for missing values, when possible, for sickness absence over 14 days. Many of the missing values are likely zero based on surrounding values but this could not be confirmed from other sources.

Secondary outcomes

There were no statistically significant differences between groups in patient-reported work ability and health outcomes. Both groups showed statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in the within-group comparison for change over time from baseline to the three-month follow-up, except for general self-efficacy and depression symptoms (). Only the PREVSAM group showed significantly reduced depression symptoms. Both groups reported satisfactory levels of general self-efficacy already at baseline which remained over time.

Table 9. Differences in patient-reported health outcomes within and between groups.

Discussion

Most patients had no sickness absence during this short-term follow-up and significant improvements in patient-reported work ability and health outcomes were found in both groups. The results suggest that both team-based rehabilitation and TAU can be used for patients with acute/subacute MSDs who exhibit psychological risk factors.

According to this trial’s short-term results, a higher proportion in the PREVSAM group remained in full- or part-time work and had fewer registered sickness benefit days compared with TAU. The opposite was reported in a previous RCT, in which early multidisciplinary assessment was associated with increased sickness absence during the first three months [Citation53]. However, that intervention did not include any treatment and was not described as person-centred teamwork. After assessment, those who were judged to be able to benefit from treatment were referred by the GP to standard healthcare resources. Contrary to the PREVSAM model’s person-centred approach with goal-targeting rehabilitation, the extensive assessments provided may, as discussed by the authors, have focused more on the patients’ symptoms and problems.

Both groups reduced their self-assessed risk associated with sickness absence. In the PREVSAM group the risk decreased by 24% and in the control group by 19%. In the PREVSAM group, the median decreased to below the trial’s cut-off value of 40p on ÖMPSQ-SF at the three-month follow-up. Screening as routine for MSDs may have disadvantages, such as being burdensome or leading to false results [Citation34]. A score of 48 points on ÖMPSQ-SF is suggested as the optimal cut-off value to best balance between false positives (misclassifying as high risk) and false negatives (misclassifying as low risk) [Citation54]. This trial’s cut-off value of 40 points may therefore have been too low. However, median score was 51 in the PREVSAM group and 52 in TAU. Screening for risk factors is suggested to reduce long-term disability in medium- and high-risk patients, and prevent over-treatment of low-risk patients but requires that the therapists have biopsychosocial knowledge and competency to handle risk factors [Citation33]. Using a person-centred approach is suggested to be a cornerstone for all MSD management [Citation31]. If the healthcare professional only checks if the total score is above cut-off for increased risk, important information may be overlooked. In rehabilitation according to the PREVSAM model, both what the patient reports works well and issues from the screening results should be considered, using a person-centred approach. This information is important when establishing a health plan. Moreover, this person-centred approach should ensure that the health plan is neither too demanding or comprehensive, nor insufficient.

Regarding perceived work ability, the median was increased by two points to 8 in the PREVSAM group and by one point to 7.5 in the TAU group at the three-month follow-up, indicating that both groups reached a moderate to good work ability according to accepted classifications of the instrument [Citation40]. In prior research WAS as work ability measure has been suggested to measure other aspects of work ability than sickness absence, as patients may be working despite experiencing decreased work ability [Citation55].

On the score of DRI, both groups reported improvement, the intervention group by 43.1% and the control group by 36.8%. Changes greater than 10% on DRI have been suggested as a minimal important difference at a group level [Citation56]. Both groups reported a decrease by two points on the 11-point Likert scale for current pain, which is considered an important clinical improvement [Citation57]. Similar improvement in PNRS after 13 weeks in the intervention group receiving cognitive functional therapy, was seen in Kent et al.’s study [Citation58]. Contrary to our results, their control group receiving TAU did not report significant improvements. This may be due to differences in TAU and that their participants had chronic low back pain. In this group treatment mainly focuses on increasing function rather than decreasing pain. However, it is important to bear in mind that the pain experience may be influenced by other things than pain itself [Citation43].

A desirable level of pain self-efficacy was reported in both groups already at baseline, according to the interpretation guide from Nicholas et al. [Citation44], and was increased at follow-up. The reported level of general self-efficacy was high from baseline to follow-up in both groups. The self-reported high levels of self-efficacy already at baseline is a notable finding as prior research has suggested self-efficacy to be relevant for clinical outcomes in patients with MSDs in a primary care setting [Citation59,Citation60]. For patients with MSDs, having low pain levels and low pain self-efficacy at baseline, is associated with similar or worse outcome than having high baseline pain and high pain self-efficacy [Citation60]. As increased psychological risk factors were an inclusion criterion, it is interesting that the participants’ self-reported anxiety and depression symptoms were not troublesome on a group level, however present in some individuals. The bidirectional relationships between symptoms of depression, anxiety and pain are highlighted in prior research. The same applies to treatment, and consequently adequate treatments of pain as well as depression and anxiety are needed [Citation61]. Both groups reported rather low health-related quality of life on EQ VAS at baseline compared to a general Swedish population reporting 88.8 points [Citation62]. Both groups reported a higher health-related quality of life at the three-month follow-up compared to baseline, an increase of 34% from baseline in the PREVSAM group and 25% in TAU at the three months’ follow-up; however, the median was still below the general population. This finding may reflect the complexity of our participants’ health problems as EQ VAS is related to health-related behaviours, diseases, and self-reported conditions [Citation63].

Methodological considerations

Conducting research on complex interventions for participants with complex health issues within primary care is a major challenge. To our knowledge, few RCTs conducted in primary care have addressed sickness absence due to MSD and the interventions have seldom yielded significantly reduced days of sickness absence [Citation53,Citation64–66], with one exception [Citation22].

The randomisation was successful except for demographic differences in occupation. Slightly more patients described having a physically demanding work in the TAU group. Obstacles to work when having MSDs may be due to demanding work tasks and to psychosocial factors [Citation67]. On the other hand, those describing a more demanding intellectual job or personnel responsibilities in the PREVSAM group also have work-related risk factors for MSDs and psychosocial factors. Prior research reports that 20% to 60% of office workers suffer from MSDs related to upper limb or neck [Citation68]. Moreover, being a manager may also include physically demanding work, for example when working in construction, warehouse, or restaurant industries. Furthermore, they may have had secondary pain problems, such as sleep difficulties. During the COVID-19 pandemic, quality of sleep has been reported sub-optimal in office workers [Citation69]. Some reported working additional hours to compensate for the self-perceived submaximal work performance. However, stress is associated with MSD symptoms in both occupational groups [Citation70].

Evaluating prevention of sickness absence involves a statistical challenge, i.e., how to measure something that does not occur. In these short-term analyses, we analysed proportions who remained in full- or part time work, and gross and net days for those who were absent from work. As the first two weeks rely on patient-reported data, the missing data complicated the analysis as we cannot know whether participants were working or not, if not reporting sickness absence. A related limitation was that the patient-reported sickness absence data only provided information on absence, not whether it was a whole day or part of the day. We analysed the absence, regardless of full or part time, as reduced work ability leading to sickness absence, in line with prior research [Citation22]. Marmot et al. [Citation71] concluded that spells of sickness absence longer than seven days, are more likely to be health-related than shorter spells. This indicates that analysing registered sickness benefits days is a more reliable measure; however, as the aim was to prevent all sickness absence, not only sickness benefit days, we decided to include self-reported sickness absence. The non-parametric rank sum test was used due to data skewness as relatively few per group had sickness absence, which in turn means that each individual’s value significantly affects the results.

The minimal important difference is suggested by Jaeschke et al. [Citation72,p.408] to be “the smallest difference in score in the domain of interest which patients perceive as beneficial and which would mandate, in the absence of troublesome side effects and excessive cost, a change in the patient’s management.” Which treatment effects that patients with MSDs consider large enough to make it worthwhile to participate in treatments are discussed by Christiansen et al. [Citation73] and suggested to be at least 20% of additional improvement on pain and disability compared with natural recovery. As both groups received treatments in our trial, it is not clear to what degree these improvements are due to treatments provided or are a result of natural recovery. We used non-parametric tests in the analysis of differences in the PROMs between baseline and follow-up assessments. Both groups reported statistically significant improvements from baseline to the three-month follow-up that we consider clinically meaningful improvements in most of the PROMs, discussed above.

Strengths of the current study are the randomised controlled design, the objective measurement of sickness benefits days, the use of established PROMs, and that it was conducted within clinical settings in primary care and thereby reflects clinical reality. However, weaknesses may exist because different circumstances in this real-life setting may have affected the treatment fidelity. The PREVSAM intervention required active involvement from both the professionals and the patients. To recognise each patient’s unique situation, mapping his/her resources and personal goals is suggested to empower patients to cope with MSDs [Citation74]. Organisational factors, such as a high workload with time pressure and perceived lack of support from colleagues and managers, have been reported as barriers to teamwork [Citation75,Citation76] and may have affected the conditions at some clinics for a team-based, person-centred approach in the present trial.

Some other factors may have influenced the results of this trial. Firstly, it was mostly conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and from 11 March 2020, until April 2022, the qualification day for sickness absence which was not normally reimbursed was temporarily reimbursed by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Moreover, the temporary regulations meant that a doctor’s certificate was not required during the first 14 sick days to receive sick pay, in contrast to the usual requirement of providing a doctor’s certificate from the eighth sick day [Citation77]. Additionally, during six months in 2020 and nine months in 2021, a doctor’s certificate was not required until the 21st day of a sickness spell. While the temporary regulations for sick leave during the COVID-19 pandemic complicated the analysis, they should have affected both groups to the same extent and, therefore, should not have influenced the results. Moreover, the possibility to work from home may have reduced sickness absence, not only for infection symptoms but also for MSDs and minor mental illness. Due to the pandemic, there was a high level of absenteeism among both patients and staff. Scheduled visits had to be cancelled at short notice and could not always be postponed to a later date. Deviations from the PREVSAM model may have led to the care provided being too similar in the intervention and control groups to show significant differences between the groups.

Secondly, the treatment periods were longer in PREVSAM compared with TAU, which means that approximately 77% of the patients in PREVSAM had not yet completed their course of treatment within this short-term follow-up compared to 60% in TAU. As the PREVSAM intervention was team-based and thus more comprehensive compared with TAU, the longer treatment periods are not surprising but may have affected the short-term results, most likely to the disadvantage of the PREVSAM model.

Thirdly, patients agreeing to participate in a study may differ from the average patient in clinical reality. The target group of patients of working age with MSD, screening 40 points or above on the ÖMPSQ-SF is, according to our study’s result, a heterogenous group. The study participants differ to some degree from Swedish society in general. In Sweden, about 15% of the population were born outside the European Union [Citation78], whereas in this sample only about 5% were born outside Europe. The participants’ education level and income level are higher than the average in Sweden and the participants are married or co-habiting to a greater extent [Citation78,Citation79]. The study participants in both groups being more resourceful than the average MSD patient within primary care rehabilitation may limit the transferability of the study’s result to other clinical contexts.

Fourthly, although no significant differences in sickness absence or patient-reported outcomes compared to TAU were found, some benefits may be present. In qualitative studies, the PREVSAM model was well received by both healthcare professionals and patients, appreciating teamwork [Ekhammar accepted, Ekhammar, in manuscript]. However, concerns were also raised. The screening was considered important to capture risk factors, but a person-centred medical history was considered necessary to identify the need for team-based rehabilitation in those at risk.

Finally, the response rate decreased over time, both regarding patient-reported sickness absence and patient-reported health outcomes. Internal dropout is a major concern in research. Although we believe our study’s response rates for the patient-reported outcomes stand up well in a research context [Citation80,Citation81], they may still have affected the results. Prior research suggests reasons for not answering text messages may be being less motivated when having a poorer prognosis or low interest in the research regardless of health status [Citation75]. Therefore, it is unknown whether the dropouts have affected the results in favour of either of the compared groups.

Conclusions

Even though identified as being at increased risk for sickness absence, the majority of participants, in both groups, remained in full- or part-time work during and after their rehabilitation. For the primary outcome, sickness absence, the PREVSAM model may have an advantage over TAU, but the difference did not reach statistical significance at p < 0.05 level. The findings suggest similar, clinically meaningful improvements in patient-reported health outcomes with both rehabilitation according to the PREVSAM model and with TAU. Long-term effects need to be evaluated before firm conclusions can be drawn.

Future research

The addition of team-based interventions to TAU will be further explored in long-term follow-ups (six months and one year) as well as in qualitative studies of the healthcare professionals’ and the patients’ experiences. A process evaluation study will further explore whether the results may be due to the intervention itself or the way it has been implemented. A cost-effectiveness study will evaluate whether the PREVSAM model is cost-effective in relation to TAU, for example, whether the trend towards fewer sickness benefit days may compensate for the costs of increased number of visits.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority [Registration] No 2019-00832/1253-18, amendments 2020-00417, 2021-04275, 2022-06191-02, 2024-02233-02.

Consent form

The principles of the Helsinki declaration were followed, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data are available on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, et al. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;396(10267):2006–2017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32340-0.

- Haas R, Gorelik A, Busija L, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of musculoskeletal complaints in primary care: an analysis from the population level and analysis reporting (POLAR) database. BMC Prim Care. 2023;24(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12875-023-01976-z.

- Babatunde OO, Jordan JL, Van der Windt DA, et al. Effective treatment options for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: a systematic overview of current evidence. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178621.

- Jordan KP, Kadam UT, Hayward R, et al. Annual consultation prevalence of regional musculoskeletal problems in primary care: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11(1):144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-144.

- Kongsted A, Kent P, Quicke JG, et al. Risk-stratified and stepped models of care for back pain and osteoarthritis: are we heading towards a common model? Pain Rep. 2020;5(5):e843. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000843.

- World Physiotherapy. Description of physical therapy. Policy statement. 2016 [cited 2023 Sept 15]. Available from: https://world.physio/sites/default/files/2020-07/PS-2019-Description-of-physical-therapy.pdf

- Bornhöft L, Larsson ME, Nordeman L, et al. Health effects of direct triaging to physiotherapists in primary care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2019;11:1759720x19827504. doi: 10.1177/1759720X19827504.

- Ludvigsson ML, Enthoven P. Evaluation of physiotherapists as primary assessors of patients with musculoskeletal disorders seeking primary health care. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(2):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2011.04.354.

- Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, et al. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(2):79–86. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099878.

- Delgado-Sanchez A, Brown C, Sivan M, et al. Are we any closer to understanding how chronic pain develops? A systematic search and critical narrative review of existing chronic pain vulnerability models. J Pain Res. 2023;16:3145–3166. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S411628.

- Ching A, Prior Y, Parker J, et al. Biopsychosocial, work-related, and environmental factors affecting work participation in people with osteoarthritis: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):485. doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06612-6.

- The Swedish Social Insurance System . Social insurances in figures [Internet]. Försäkringskassan. 2023; [cited 2023 Oct 26]. Available from Statistikdatabas - Försäkringskassan (forsakringskassan.se)

- Macías-Toronjo I, Sánchez-Ramos JL, Rojas-Ocaña MJ, et al. Influence of psychosocial and sociodemographic variables on sickness leave and disability in patients with work-related neck and low back pain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5966. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165966.

- Malmberg-Ceder K, Haanpää M, Korhonen PE, et al. Relationship of musculoskeletal pain and well-being at work - does pain matter? Scand J Pain. 2017;15(1):38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.11.018.

- Garnæs KK, Mørkved S, Tønne T, et al. Mental health among patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and its relation to number of pain sites and pain intensity, a cross-sectional study among primary health care patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1115. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-06051-9.

- Hutting N, Boucaut R, Gross DP, et al. Work-focused health care: the role of physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2020;100(12):2231–2236. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa166.

- St-Georges M, Hutting N, Hudon A. Competencies for physiotherapists working to facilitate rehabilitation, work participation and return to work for workers with musculoskeletal disorders: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2022;32(4):637–651. doi: 10.1007/s10926-022-10037-8.

- Oswald W, Hutting N, Engels JA, et al. Work participation of patients with musculoskeletal disorders: is this addressed in physical therapy practice? J Occup Med Toxicol. 2017;12(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s12995-017-0174-5.

- Daley D, Payne LP, Galper J, et al. Clinical guidance to optimize work participation after injury or illness: the role of physical therapists. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(8):Cpg1–cpg102. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2021.0303.

- Dropkin J, Roy A, Szeinuk J, et al. A primary care team approach to secondary prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: physical therapy perspectives. Work. 2021;70(4):1195–1217. doi: 10.3233/WOR-205139.

- Swedish Work Environment Authority. [Arbetsmiljöverket] [updated 230623; cited 2023 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.av.se/en/work-environment-work-and-inspections/acts-and-regulations-about-work-environment/

- Sennehed CP, Holmberg S, Axén I, et al. Early workplace dialogue in physiotherapy practice improved work ability at 1-year follow-up -workup, a randomised controlled trial in primary care. Pain. 2018;159(8):1456–1464. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001216.

- Cullen KL, Irvin E, Collie A, et al. Effectiveness of workplace interventions in return-to-work for musculoskeletal, pain-related and mental health conditions: an update of the evidence and messages for practitioners. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10926-016-9690-x.

- Karran EL, McAuley JH, Traeger AC, et al. Can screening instruments accurately determine poor outcome risk in adults with recent onset low back pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0774-4.

- Linton SJ, Boersma K. Early identification of patients at risk of developing a persistent back problem: the predictive validity of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire. Clin J Pain. 2003;19(2):80–86. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200303000-00002.

- Linton SJ, Nicholas M, MacDonald S. Development of a short form of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Spine. 2011;36(22):1891–1895. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f8f775.

- Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, et al. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (“yellow flags”) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):737–753. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100224.

- Björk Brämberg E, Jensen I, Kwak L. Nationwide implementation of a national policy for evidence-based rehabilitation with focus on facilitating return to work: a survey of perceived use, facilitators, and barriers. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(2):219–227. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1496151.

- Stenberg G, Stålnacke BM, Enthoven P. Implementing multimodal pain rehabilitation in primary care - a health care professional perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(21):2173–2181. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1224936.

- Lagueux É, Dépelteau A, Masse J. Occupational therapy’s unique contribution to chronic pain management: a scoping review. Pain Res Manag. 2018;2018:5378451–5378419. doi: 10.1155/2018/5378451.

- Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, et al. Patient-centred care: the cornerstone for high-value musculoskeletal pain management. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(21):1240–1242. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101918.

- Larsson M, Nordeman L, Holmgren K, et al. Prevention of sickness absence through early identification and rehabilitation of at-risk patients with musculoskeletal pain (PREVSAM): a randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):790. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03790-5.

- Meyer C, Denis CM, Berquin AD. Secondary prevention of chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of clinical trials. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2018;61(5):323–338. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2018.03.002.

- Stearns ZR, Carvalho ML, Beneciuk JM, et al. Screening for yellow flags in orthopaedic physical therapy: a clinical framework. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(9):459–469. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2021.10570.

- Bovend’Eerdt TJH, Botell RE, Wade DT. Writing SMART rehabilitations goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):352–361. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101741.

- Whitaker SC. The management of sickness absence. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(6):420–424; quiz 424,410. doi: 10.1136/oem.58.6.420.

- The Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Customer centre for private individuals. 2024 [cited 2024 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.forsakringskassan.se/english

- Swedish, Social, Insurance, Agency. Förslag på utfallsmått för att mäta återgång i arbete efter sjukskrivning [in Swedish]. Social Insurance Report 2016;9:2016 [cited 2024 Feb 23]. Available from: https://forte.se/app/uploads/2016/10/socialforsakringsrapport_2016_09.pdf

- Whitford HM, Donnan PT, Symon AG, et al. Evaluating the reliability, validity, acceptability, and practicality of SMS text messaging as a tool to collect research data: results from the feeding your baby project. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(5):744–749. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000785.

- Ahlstrom L, Grimby-Ekman A, Hagberg M, et al. The work ability index and single-item question: associations with sick leave, symptoms, and health–a prospective study of women on long-term sick leave. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;36(5):404–412. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2917.

- Salén BA, Spangfort EV, Nygren AL, et al. The Disability Rating Index: an instrument for the assessment of disability in clinical settings. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(12):1423–1435. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90086-8.

- Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, et al. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(6):1073–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.016.

- Chiarotto A, Maxwell LJ, Ostelo RW, et al. Measurement properties of visual analogue scale, numeric rating scale, and pain severity subscale of the brief pain inventory in patients With low back pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2019;20(3):245–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.07.009.

- Nicholas MK, McGuire BE, Asghari A. A 2-item short form of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire: development and psychometric evaluation of PSEQ-2. J Pain. 2015;16(2):153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.11.002.

- Ekhammar A, Numanovic P, Grimby-Ekman A, et al. The Swedish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire Short Form; PSEQ-2SV. Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders. Scand J Pain. 2024;7:24(1). doi: 10.1515/sjpain-2023-0059.

- Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M.). Self-efficacy measurement and generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, editors. Measures in health psychology: a users’s portfolio. Causal control beliefs. Windsor: NFER-NELSON; 1995. p. 33–39.

- Löve J, Moore CD, Hensing G. Validation of the Swedish translation of the general self-efficacy scale. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(7):1249–1253. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0030-5.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3.

- EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208.

- Soer R, Reneman MF, Speijer BL, et al. Clinimetric properties of the EuroQol-5D in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine J. 2012;12(11):1035–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.10.030.

- Official Statistics of Sweden. The Swedish Occupational Register with Statistics. 2012. [cited 2023 Oct 26]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/labour-market/employment-and-working-hours/the-swedish-occupational-register-with-statistics/

- Carlsson L, Englund L, Hallqvist J, et al. Early multidisciplinary assessment was associated with longer periods of sick leave: a randomized controlled trial in a primary health care Centre. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2013;31(3):141–146. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2013.811943.

- Nicholas MK, Costa DSJ, Linton SJ, et al. Predicting return to work in a heterogeneous sample of recently injured workers using the brief ÖMPSQ-SF. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(2):295–302. doi: 10.1007/s10926-018-9784-8.

- Forsbrand MH, Turkiewicz A, Petersson IF, et al. Long-term effects on function, health-related quality of life and work ability after structured physiotherapy including a workplace intervention. A secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial (workup) in primary care for patients with neck and/or back pain. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2020;38(1):92–100. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2020.1717081.

- Persson E, Lexell J, Eklund M, et al. Positive effects of a musculoskeletal pain rehabilitation program regardless of pain duration or diagnosis. PM&R. 2012;4(5):355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.11.007.

- Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, et al. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(4):283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.09.004.

- Kent P, Haines T, O’Sullivan P, et al. Cognitive functional therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): a randomised, controlled, three-arm, parallel group, phase 3, clinical trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10391):1866–1877. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00441-5.

- Denison E, Åsenlöf P, Lindberg P. Self-efficacy, fear avoidance, and pain intensity as predictors of disability in subacute and chronic musculoskeletal pain patients in primary health care. Pain. 2004;111(3):245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.001.

- Chester R, Khondoker M, Shepstone L, et al. Self-efficacy and risk of persistent shoulder pain: results of a Classification and Regression Tree (CART) analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(13):825–834. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099450.

- Michaelides A, Zis P. Depression, anxiety and acute pain: links and management challenges. Postgrad Med. 2019;131(7):438–444. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2019.1663705.

- Teni FS, Burström K, Devlin N, et al. Experience-based health state valuation using the EQ VAS: a register-based study of the EQ-5D-3L among nine patient groups in Sweden. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2023;21(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s12955-023-02115-z.

- Teni FS, Gerdtham UG, Leidl R, et al. Inequality and heterogeneity in health-related quality of life: findings based on a large sample of cross-sectional EQ-5D-5L data from the Swedish general population. Qual Life Res. 2022;31(3):697–712. Mar doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02982-3.

- Andersen LN, Juul-Kristensen B, Roessler KK, et al. Efficacy of ‘Tailored Physical Activity’ on reducing sickness absence among health care workers: a 3-months randomised controlled trial. Man Ther. 2015;20(5):666–671. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.04.017.

- Emilson C, Demmelmaier I, Bergman S, et al. A 10-year follow-up of tailored behavioural treatment and exercise-based physiotherapy for persistent musculoskeletal pain. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(2):186–196. doi: 10.1177/0269215516639356.

- Fisker A, Langberg H, Petersen T, et al. Effects of an early multidisciplinary intervention on sickness absence in patients with persistent low back pain-a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):854. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05807-7.

- Madan I, Grime PR. The management of musculoskeletal disorders in the workplace. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29(3):345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2015.03.002.

- Hoe VC, Urquhart DM, Kelsall HL, et al. Ergonomic interventions for preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb and neck among office workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10(10):CD008570.

- Žilinskas E, Puteikis K, Mameniškienė R. Quality of sleep and work productivity among white-collar workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicina. 2022;8(7):883. doi: 10.3390/medicina58070883.

- Herr RM, Bosch JA, Loerbroks A, et al. Three job stress models and their relationship with musculoskeletal pain in blue- and white-collar workers. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79(5):340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.08.001.

- Marmot M, Feeney A, Shipley M, et al. Sickness absence as a measure of health status and functioning: from the UK Whitehall II study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49(2):124–130. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.2.124.

- Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10(4):407–415. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6.

- Christiansen DH, de Vos Andersen NB, Poulsen PH, et al. The smallest worthwhile effect of primary care physiotherapy did not differ across musculoskeletal pain sites. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;101:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.05.019.

- Larsson A, Barenfeld E, Fors A, et al. Person-centred health plans for physical activity in persons with chronic widespread pain (CWP) - a retrospective descriptive review. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45(11):1857–1864. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2077992.

- Sangaleti C, Schveitzer MC, Peduzzi M, et al. Experiences and shared meaning of teamwork and interprofessional collaboration among health care professionals in primary health care settings: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(11):2723–2788. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003016.

- Hellman T, Jensen I, Bergström G, et al. Essential features influencing collaboration in team-based non-specific back pain rehabilitation: findings from a mixed methods study. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(3):309–315. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2016.1143457.

- The Swedish Social Insurance. Effekter som covid-19 har på sjukförsäkringen. Del 3. 2020. [cited 2023 Oct 26]. Available from: regeringsuppdragets bilaga 2

- Official Statistics of Sweden. Population. 2023. [cited 2023 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/

- The Swedish Trade Union Confederation. Lönerapport 2022. [cited 2023 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.lo.se/start/lo_fakta/lonerapport_ar_2022

- Axén I, Bodin L, Bergström G, et al. The use of weekly text messaging over 6 months was a feasible method for monitoring the clinical course of low back pain in patients seeking chiropractic care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(4):454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.012.

- Keus van de Poll M, Nybergh L, Lornudd C, et al. Preventing sickness absence among employees with common mental disorders or stress-related symptoms at work: a cluster randomised controlled trial of a problem-solving-based intervention conducted by the Occupational Health Services. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(7):454–461. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2019-106353.