Abstract

Purpose

To explore the factors that influence clinicians (occupational therapists, physiotherapists, vascular surgeons, and rehabilitation medicine physicians) when prescribing prosthetic rehabilitation. Additionally, the study aimed to gain insight into clinicians’ perspectives regarding the role of patient cognition in prosthetic rehabilitation.

Materials and methods

This research constitutes one segment of a broader action research study which was undertaken in 2022. A total of thirty-four key clinicians involved in the amputation and prosthetic rehabilitation pathway within a local health district in Australia were engaged through a combination of group and individual interviews as well as surveys.

Results

Five essential considerations when prescribing prosthetic rehabilitation emerged. These included patient’s goals, medical history, quality of life, cognitive abilities, and the support available on discharge. This study also revealed variations in opinions among different disciplines concerning appropriateness of prosthetic rehabilitation for the patient cohort. Despite this, there was a desire to build a consensus around a shared approach of identification for patients and clinicians.

Conclusion

The identification of these key pillars for clinician consideration has simplified a complex area of care. These pillars could be used to guide pertinent conversations regarding prosthetic rehabilitation and are closely linked with the patient’s cognition.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Five key areas should be considered when prescribing prosthetic rehabilitation; patients’ goals, medical history, quality of life, cognitive abilities and supports available on discharge.

Qualitative findings show different clinician domains hold very different perspectives on the suitability of patients to receive a prosthesis and undergo prosthetic rehabilitation.

Occupational therapists and rehabilitation medicine clinicians most frequently view patients as suitable to undergo prosthetic rehabilitation, followed by physiotherapists and finally vascular surgeons.

Vascular surgeons view most patients’ complex vascular medical history as a reason why only certain (younger) patients should undergo prosthetic rehabilitation.

Communication of expectations between all members of the treating team is paramount for patient outcomes.

Introduction

Prosthetic rehabilitation is of considerable cost to the healthcare system [Citation1]. The average major amputation (below knee amputation or higher) as a result of circulatory issues will cost the healthcare system approximately $128 000AUD [Citation2]. This cost excludes the prosthetic costs which in Australia is provided by each relevant state government prosthetic/artificial limb service, and may be up to $55 000AUD depending on the level of amputation and componentry (EnableNSW 2023, pers. comm., 20 April). With the associated costs so high, research has sought to provide clinical prediction rules that assist clinicians in the early identification of non-prosthetic users [Citation3]. The goal of these prediction rules being to ensure the prosthesis that a patient receives is appropriate for their mobility and functional level, or to allow for alternative (wheelchair) prescription if a prosthesis is not appropriate. To date, the validated clinical prediction rules have included items such as amputation level, mobility aid at discharge, diabetic diagnosis, length of time to prosthetic fitting and having 19 or more co-morbidities (musculoskeletal and mental health inclusive) [Citation3]. Notably absent from this group of predictive factors is the patient’s level of cognitive functioning. While cognitive impairment has been found to be present in up to 10% of non-prosthetic users, it has not to date been found to be a strong enough predictive factor for determining long term prosthetic use [Citation3].

Traditional prosthetic rehabilitation programs address areas such as balance and co-ordination, gait training, nutrition, cardiovascular health and aquatic therapy, with an acknowledgement that there is an underlying cognitive load and skillset required to achieve success in those domains [Citation4,Citation5]. Increased mobility and independence, as well as prosthetic fit have been found to be associated with intact cognitive domains of attention, working memory and visuospatial construction [Citation6–9]. The implication of these findings is that a patient’s cognitive function should be considered when patients are being assessed for prosthetic rehabilitation.

There is a scarcity of literature with regards to the type or timing of cognitive testing in conjunction with, or prior to, undertaking prosthetic rehabilitation. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of literature on cognitive testing in other surgical procedures that also require a patient to learn and retain information to manage a device following surgery, e.g., percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). Therefore, there is limited ability to apply knowledge relating to cognitive testing and timing forward into different populations such as persons with amputations. There is an acknowledged cognitive load required during prosthetic rehabilitation and mobility [Citation10]. When considered with recent findings that only 21.9% of patients who had undergone amputation surgery had cognitive screening or assessment during their hospital admission [Citation11], it provides reason to ponder if clinician perceptions and awareness of the role of cognition in prosthetic rehabilitation is considered. The potential implication is that clinicians are not aware of the impact and role of cognition, and as such may be working with an incomplete picture of the patient’s ability to both manage rehabilitation and retain information for prosthetic use following discharge.

Given this the aim was to understand the factors that clinicians (occupational therapists, physiotherapists, vascular surgeons, and rehabilitation specialists) consider when prescribing prosthetic rehabilitation. In addition, it sought to understand the clinicians’ views on the role of patient cognition in prosthetic rehabilitation.

Method

This study was part of a larger multi-phased action orientated study. In this phase two methods were used, survey with a mix of quantitative and qualitative responses, and interviews. Online survey research was conducted within the Occupational therapy (OT) and Physiotherapy (PT) disciplines due to the large number of staff within one local health district employ (approx. 150 clinicians) and to be able to access as many allied health clinicians as possible whilst ensuring that the burden of participation was as low as reasonable [Citation12]. Prior to survey development, three focus groups were held with OT and PT on prosthetic rehabilitation and cognition to ensure the survey was informed by allied health perspectives and not biased from the lead researcher. Interview methods (both individual and group) were chosen for medical clinicians (vascular surgeons and rehabilitation medicine) at their request due to smaller overall cohort numbers in these two specialties.

Ethics considerations

Ethics approval was obtained through the University of Wollongong and Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee (2021/ETH00462).

Recruitment

There are seven hospital sites in the health district, with allied health clinicians (OT and PT) working from each of these seven sites, rehabilitation medicine clinicians work across four sites, and vascular medical clinicians work at the sole tertiary hospital site. Heads of each Department emailed invitations to participate. Email recruitment for the interviews (medical clinicians) occurred one month prior to commencing the interview process. A time and quiet location of their choosing was confirmed once they had agreed to participate. A participant information sheet and a consent form was then sent and they were given the opportunity to withdraw from the interview prior to commencing.

Each Head of discipline (OT and PT) sent an email invitation to the distribution list for their respective disciplines within the health district which contained a direct link to the survey. Follow-up email invitations for participation were sent at a further two time points; 1-week after opening and 3-weeks after opening to encourage further participation. Implied consent was used for survey participation as participants made an active choice to follow the disseminated invitation link.

shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation in the study.

Table 1. Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data collection

Data was collected over a three-month period, commencing June 2022, with interviews. This process continued throughout the three-month period. Interviews were audio-taped and transcribed by the lead researcher or an external transcription service as per the ethical approvals. Transcripts were checked for accuracy and to ensure names were removed for de-identification and to maintain confidentiality. As the interviews were semi-structured, an interview guide was devised by the authors which was used to provide an overarching guide to the questions that were asked to ensure data collection was consistent. Example questions include “Prior to amputation, what information do patients receive on the surgery and/or rehabilitation?” and “Are there any circumstances in which you would not recommend a patient receive a prosthesis?.”

The survey commenced mid-July 2022 and was open for a period of one month. Surveys were completed and data generated and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) [Citation13,Citation14]. The survey (Appendix 1) comprised 18 questions ranging from demographics to questions which addressed the aims of the study. This data was collected concurrently with interview data collection. More information regarding data collection and participation can be found in .

Table 2. Data collection and analysis.

A question pertaining to the role of cognition in prosthetic rehabilitation was asked at the end of each data collection session. For example, “To what extent do you think cognition is likely to be impacted on by the disease process that causes vascular patients to lose their legs?” This avoided unduly influencing clinicians to consider cognition when addressing the first research aim; factors they consider when prescribing prosthetic rehabilitation.

All data collection occurred in line with social distancing restrictions in place within the local health district as a result of COVID-19.

Data analysis

Data taken from interview transcripts and the open ended responses from the survey were subject to thematic analysis following the six-stage (see ) process established by Braun and Clarke [Citation15]. Thematic analysis was chosen as it allowed for an inductively developed critical analysis, allowing themes to be found within the research rather than being applied to it [Citation15,Citation16]. Rigour was established through three systematic engagements with the data by the lead researcher (ED). Final themes were confirmed by two other members of the research team (VB, LH).

Table 3. Braun and Clarke six stages of thematic analysis.

Descriptive statistics of survey data were used to describe the sample.

Results

Twenty-four surveys were completed by PT (n = 14) and OT (n = 10), giving a response rate of 16% from the PT and OT cohort of clinicians. The level of discipline specific years of experience, post graduate amputee education, confidence and experience in treating amputees as reported by the participants is shown in . A total of 10 medical clinicians participated across three interviews, encompassing all the vascular surgery team and 50% of the senior rehabilitation medicine clinicians.

Table 4. Clinician experience and amputee awareness.

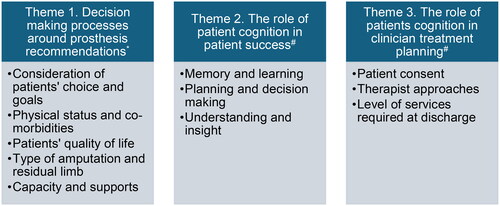

Three themes (and related sub-themes) emerged from the qualitative data (). Theme 1, annotated by an asterisk (*) related to the factors that clinicians consider when prescribing prosthetic rehabilitation. Themes 2 and 3, annotated by an octothorpe (#) related to clinicians views on the role of cognition in prosthetic rehabilitation.

Decision making processes around prosthesis recommendations

Theme 1 explored the many considerations that make up a patient admission, their journey through healthcare and their resultant discharge. Clinicians identified that working holistically with patients’ co-morbidities and quality of life were important considerations, as was the ability to work with the patients’ beliefs and choices. Five subthemes were identified.

Consideration of patients’ choice and goals

This subtheme focused on the patients’ right to be in control of the decisions that will affect their future mobility and function. Clinicians such as Med 5 described that receiving a prosthetic was “a fairly basic right if they seem that there may be a chance of using a prosthesis, [they] should be given a chance, especially for transtibial amputees.” While it was acknowledged to be a basic right, clinicians were quick to highlight that choice can be either for a prosthetic or against it; with PT 12 indicating “if they want to they should be able to have a chance” while PT 4 responded “if a patient has no intention or goal of prosthetic use and is agreeable to wheelchair use then they shouldn’t get a prosthetic.” This dichotomy was reflected in the response by PT 1 who stated, “if they want a trial they should have one, maybe they need to fail to see how hard it is.”

Physical status and co-morbidities

Prosthetic rehabilitation is a physically demanding task, and thus the physical status and co-morbidities that a patient presents with can influence clinician decisions about prosthetic rehabilitation. There are several health concerns that are associated with vascular disease which clinicians indicated could make prosthetic rehabilitation challenging; ranging from “peripheral neuropathy” as noted by Med 5, or the “morbid obesity,” “cardiorespiratory limitations” or “vision” concerns raised by PT 3, PT 14, and Med 1, respectively. The potential severity and life limiting nature of vascular disease was referenced by Med 2 with their response “the majority for us is palliative” which was confirmed by Med 1 stating “It’s end stage life, certainly there’s a lot that will never mobilise on a prosthetic.” An unlikely, less severe physical consideration was voiced by Med 3, noting that “the other thing that plays a part in terms of prosthetic use is the hand function” as without this the prosthetic cannot be donned or doffed.

Patients’ quality of life

Quality of life (QoL) can be viewed as an outcome measure following amputation or it can be viewed as an indicator for receiving a prosthesis. The consideration of QoL as an outcome was highlighted by OT 3’s reflection:

“I previously had a client with a very life limiting diagnosis spend significant periods of time in hospital attempting prosthesis training only to be discharged home in a wheelchair and pass away I think months [later]. This client’s quality of life was not improved.”

Given the seriousness of amputation in terms of overall health, it is unsurprising that there was consideration of patients’ mental health in the QoL discussion. PT 8 shared how “some [patients] may not have the physical abilities to manage walking, but it [a prosthetic] can assist with adjustment issues and psychosocial health.” Adjustment of personal identity and time to assimilate to their new identity was heard in the response from PT 7 who described how “a prosthesis can help a person who is grieving the loss of their limb.”

Type of amputation and residual limb

The type of amputation a patient has undergone, and the size and shape of the residual limb can influence prosthetic prescription. As OT 7 remarked, “not all patients’ residual limb will support a prosthetic.” Med 5 took it further and gave levels of amputation that may not support a prosthetic with their response “I think there are circumstances where we wouldn’t recommend or script one. If they’ve had a very high transfemoral or hip disarticulation.” There was acknowledgement and consensus amongst the physiotherapy respondents that a prosthetic can provide other stimulation and benefits to the residual limb beyond walking, with PT 3 responding “some will not have the physical abilities to manage walking, but it can assist with stump shaping.”

Capacity and supports

There was awareness from clinicians that cognition would play a role in prosthetic recommendations. Most clinicians were in agreeance with PT 5 who reported “some patients’ are not suitable [to manage a prosthetic] due to cognitive concerns.” It was OT 2 who paused and reflected that “even someone with a cognitive impairment may be able to manage a prosthesis.”

It may not be the patient who manages the prosthetic, and the safety, but support from within the home. Both PT 1 and PT 12 commented that “I would say no to a prosthesis” if the patient has “no supports at home” or if “the client and their carer were unable to don any type of prosthesis.”

The role of patient cognition in patient success

Three separate areas of the cognitive profile were identified as areas clinicians believed impacted on their prescription of prosthetic rehabilitation for patients. This theme saw exploration of both intact and non-intact cognition and resulted in some differing perspectives from the clinicians.

Memory and learning

This sub-theme saw all clinicians note that memory and learning is the key to patient success, but could vary depending on the situation, as Med 1 reflected on in their response “It’s interesting, you sit and talk to them in a room for 10 min and they seem quite fine… if you get them alone for half an hour you realise it’s actually miles apart.”

When asked about the potential role of cognition in prosthetic rehabilitation, many responded in line with OT 6 who noted that “cognitive impairments limit a person’s ability to learn new information.” One clinician, OT 7, elaborated further with “if someone’s ability to learn or retain new information is impaired, wheelchair use may be difficult let alone prosthetic use.”

Planning and decision making

Every day we make decisions about how our day will unfold. For a person who has undergone an amputation and has impaired cognition, these decisions can have consequences for the trajectory of their day, as highlighted by OT 3 with their response “planning skills impacts ability to plan activities such as showering and meal prep.” This was extended on by OT 9 who reflected that “cognition is required to make sound decisions, judge a new or challenging situation appropriately.”

The context of planning and decision making was not limited to activities of daily living for amputee patients, with Med 1 noting that a patient’s cognition in determining their success could center on planning relevant to their medical conditions and future care needs “it [cognition] can help in the decision making process to stop other active treatments.”

Understanding and insight

In examining the role of patient cognition in patient success, clinicians identified that insight and understanding were pivotal. Physiotherapist 13 noted that “cognition affects ability of [the] client to see value of prosthesis and rehab process” with fellow physiotherapist (PT4) explaining that patients’ needed cognition to “connect the dots of how their function in rehab influences discharge planning.”

There was acknowledgement from clinicians that the context and timing of information provision could impact on a patients’ understanding and insight, with Med 2 recalling “you bring them into theatre, a patient that seems to understand, co-operative, all good, but then in theatre by themselves under the bright lights, 20 people around, boom, no comprehension.”

Situational awareness also extends to the home environment, with OT 3 identifying that “insight impacts the ability to recall in the middle of the night that they have had an amputation and need to move different to [the] toilet.”

The role of patients’ cognition in clinician treatment planning

In theme 3 clinicians articulated how a patient’s cognition would impact on treatment planning, the clinician’s ability to provide education, prescribe rehabilitation and what that might mean for the patient when discharge planning was occurring. Two subthemes were identified.

Patient consent

At the very core of healthcare treatment is a patients’ consent to the tests, surgical intervention, or rehabilitation they are undergoing, or about to undergo. This was front of mind for Med 4, remarking “I mean whenever we assess a patient we have to assess their cognition because that plays into consent.” This sentiment was echoed by Med 3 and Med 5, both observing that cognitive testing “would be good to do if there’s clinical indicators of something” with Med 3 going on to comment “I guess that raises an issue of capacity to consent to the amputation.” Medical clinician 2 observed that in the absence of cognition, other methods of consent need to be gained for life saving procedures, “The majority even I don’t think can make a decision to be honest. More often than not we make the decision with the relatives.”

Therapist approaches

For clinicians, each interaction with a patient brings new information to light that is used to form the clinical picture and plan a treatment. Some therapists noted that in their role they have less time to form a full clinical picture, with Med 2 noting “often we don’t have time [to do an assessment], it’s life or limb.” For others, like OT 4, the timeframes are more extended and “cognition is important as it allows the rehab program to be tailored and adjusted to the person’s ability and capacity.” Tailoring of the rehabilitation program to match a patients’ cognition was heard repeatedly in the data from the allied health clinicians.

Tailoring was not just about the rehabilitation program, but also about the equipment prescribed and prosthetic componentry. Med 3 commented “if they’re cognitively unable to use a [manual] wheelchair, or it’s dangerous, you wouldn’t prescribe them an electric one.” Similar considerations were alluded to by Med 5, stating “I think one of things to consider is that there’s sometimes different prosthetic options, particularly for transfemoral amputation and knee units and types of prosthesis.”

Discussion

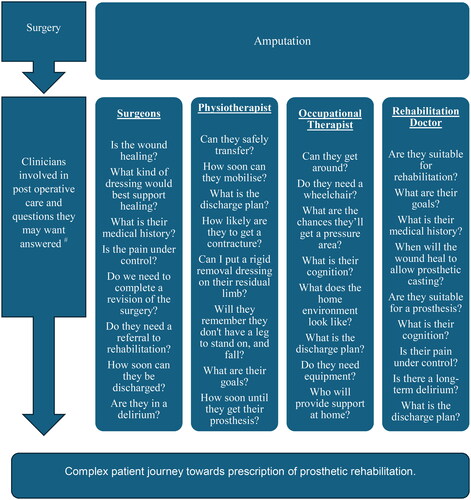

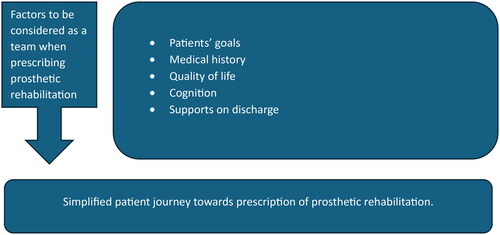

This study is the first that the authors are aware of that brings together the voices of the vascular surgeons, rehabilitation medicine specialists and allied health (OT and PT) clinicians involved in amputation and subsequent rehabilitation, on the topic of patient cognition in clinical care decision making. In seeking to understand the factors that clinicians consider when prescribing prosthetic rehabilitation, the study found that factors such as patients’ goals, medical history, quality of life, cognition and supports on discharge were all pertinent. Previous papers have urged clinicians to consider premorbid function, cognition, and socioeconomic status as indictors of likely success with rehabilitation following amputation [Citation17,Citation18]. The findings of this paper extend that, and in doing so have taken a complex patient journey (as seen in ) and made it simpler for clinicians to navigate by providing a framework to focus their attention (), while advocating that a patient centered approach remain key.

Figure 2. Overview of clinicians involved and considerations for prosthetic rehabilitation. # Note these are example topics and questions designed to provide a guide only, not an exhaustive list of discipline specific.

Figure 3. Framework proposed for multidisciplinary considerations when prescribing prosthetic rehabilitation.

The development and proposal of the framework seen in is designed as an adjunct to the discipline specific questions that clinicians use to support patient care. This study, and the framework provided, seeks to convey the importance of a collaborative multidisciplinary care approach, and highlights the importance of cognition to each of the disciplines involved in the patient’s hospital and amputation journey. Creation of a framework as proposed in could result in streamlining of clinician assessment resulting in improved patient flow through the hospital system. Furthermore, the framework provides clinicians new to the field of amputee care with a point of reference for their professional care. With formal education on the care of a person who has had an amputation varying between teaching sectors and healthcare disciplines, having a framework like the one proposed can increase the training resources available to clinicians.

Stepping further into understanding the role of cognition in prosthetic rehabilitation, clinicians indicated that this factored in at every stage of the process, from consenting to the amputation procedure through to decisions about prosthetic componentry and patient’s likely success with use of the prosthetic. This reinforces the work of Lombard-Vance [Citation19] and Lee and Costello [Citation20], and should serve as a timely reminder for clinicians to consider the impact that cognition is having on the patient’s success with prosthetic rehabilitation.

This study also identified differences in perspective between clinicians, and vastly different treatment approaches for the remaining life trajectory voiced. There was a prevailing view within the medical clinicians who had a vascular surgery background, that patients who had undergone amputation secondary to vascular causes are seen as palliative patients. Subsequently, the dominant perspective within this cohort was that most patients should not receive a prosthetic and undergo rehabilitation. Those that they believed eligible for prosthetic rehabilitation needed to be younger in age and demonstrate capacity to change modifiable risk factors, which would then elevate them to what they term ‘pseudo-palliative’. This differed from the data elicited from allied health clinicians, who believed that patients deserved a chance with a prosthetic but recognized that cognition played a significant role in prosthetic rehabilitation.

Within the literature, we see evidence of a high mortality rate for patients who undergo amputation as a result of diabetes [Citation21–23]. Australian data indicates that at 30 days post amputation the mortality rate is 10.1% of patients, extending to 51.7% of patients by the end of two years [Citation24]. In light of mortality rates, the palliative lens of the vascular clinicians is less surprising, but was in contrast with the views expressed by the allied health clinicians.

In analyzing these results, it became evident that use of the word palliative should not be taken to be synonymous with a referral to the palliative care team but was more indicative of patients who were more likely to adopt a passive approach to their healthcare and post amputation journey than be actively engaged.

Limitations

There are limitations to the study. The data presented here was taken from one local health district within New South Wales, Australia. Despite this, the data captures the perspective of various clinicians found within any health district within NSW, and indeed Australia, who are working with an amputation population. There is recognition that each health district may have differences in their amputee pathway, therefore future research is required to translate these study findings into different contexts. There was a lack of variation of participants across the medical teams and therefore results could not be analyzed separately by medical specialty and have been presented here as an amalgamation to avoid identification. Additionally, the voice of the prosthetists and orthotists could add valuable data to this topic, and inclusion of them in future research would add further depth. Finally, the survey data collection period was shorter than anticipated due to the impact of COVID-19 on working conditions amongst OT and PT clinicians. Increased collection periods may have resulted in greater participant numbers and potential for increased perspectives to be heard.

Conclusions

The results of this study have highlighted how the clinicians think about different factors relating to prosthetic rehabilitation and have simplified a complex process, identifying key areas for consideration for therapists prescribing prosthetic rehabilitation. To have cohesive multidisciplinary teams in amputee and prosthetic rehabilitation it is recommended that an open dialogue on all the constructs identified occur. Attention should be given to cognition of a patient at all points across their recovery journey to maximize its ability in achieving success with prosthetic rehabilitation.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in the submitted article do not reflect an official position of the institution.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (70.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- MacKenzie EJ, Castillo RC, Jones AS, et al. Health-care costs associated with amputation or reconstruction of a limb-threatening injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1685–1692. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.F.01350.

- Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. National efficient price determination 2023–24. Sydney: Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023.

- Roffman CE, Buchanan J, Allison GT. Predictors of non-use of prostheses by people with lower limb amputation after discharge from rehabilitation: development and validation of clinical prediction rules. J Physiother. 2014;60(4):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2014.09.003.

- Imam B, Miller WC, Finlayson HC, et al. Lower limb prosthetic rehabilitation in Canada: a survey study. Physiother Can. 2019;71(1):11–21. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2017-39.

- Coffey L, O’Keeffe F, Gallagher P, et al. Cognitive functioning in persons with lower limb amputations: a review. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(23):1950–1964. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.667190.

- Fletcher DD, Andrews KL, Butters MA, et al. Rehabilitation of the geriatric vascular amputee patient: a population-based study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(6):776–779. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.21856.

- Frengopoulos C, Payne MW, Viana R, et al. MoCA domain score analysis and relation to mobility outcomes in dysvascular lower extremity amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(2):314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.09.003.

- Schoppen T, Boonstra A, Groothoff JW, et al. Physical, mental, and social predictors of functional outcome in unilateral lower-limb amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(6):803–811. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9993(02)04952-3.

- O’Neill BF, Evans JJ. Memory and executive function predict mobility rehabilitation outcome after lower-limb amputation. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(13):1083–1091. doi: 10.1080/09638280802509579.

- MacKay C, Cimino SR, Guilcher SJT, et al. A qualitative study exploring individuals’ experiences living with dysvascular lower limb amputation. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(10):1812–1820. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1803999.

- Dawes E, Bliokas V, Hewitt L, et al. Cognitive screening in persons with an amputation: a retrospective medical record audit. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2022;46(5):500–504. doi: 10.1097/pxr.0000000000000169.

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. 4th ed. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley, 2014.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. London: SAGE Publications, 2022.

- Fleury AM, Salih SA, Peel NM. Rehabilitation of the older vascular amputee: a review of the literature. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2013;13(2):264–273. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12016.

- Batten HR, Kuys SS, McPhail SM, et al. Demographics and discharge outcomes of dysvascular and non-vascular lower limb amputees at a subacute rehabilitation unit: a 7-year series. Aust Health Rev. 2015;39(1):76–84. doi: 10.1071/ah14042.

- Lombard-Vance R, O’Keeffe F, Desmond D, et al. Comprehensive neuropsychological assessment of cognitive functioning of adults with lower limb amputation in rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(2):278–288.e272. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.07.436.

- Lee DJ, Costello MC. The effect of cognitive impairment on prosthesis use in older adults who underwent amputation due to vascular-related etiology: a systematic review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2018;42(2):144–152. doi: 10.1177/0309364617695883.

- Thorud JC, Plemmons B, Buckley CJ, et al. Mortality after nontraumatic major amputation among patients with diabetes and peripheral vascular disease: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(3):591–599. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2016.01.012.

- Gurney JK, Stanley J, Rumball-Smith J, et al. Postoperative death after lower-limb amputation in a national prevalent cohort of patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(6):1204–1211. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2557.

- Hoffstad O, Mitra N, Walsh J, et al. Diabetes, lower-extremity amputation, and death. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(10):1852–1857. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0536.

- Lim TS, Finlayson A, Thorpe JM, et al. Outcomes of a contemporary amputation series. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(5):300–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03715.x.