?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose

Provide an overview of existing knowledge on the concept of identity and identity changes and formation of people with language disorders of aphasia. To date, there has been limited exploration of identity changes of people with aphasia as communication difficulties have been perceived as a barrier to participation by researchers.

Method

A scoping review was performed utilizing Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework. The databases PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library were searched, and both descriptive and thematic analysis were conducted.

Results

The search yielded 492 records, of which 20 studies were included. The analysis revealed various theories and definitions of identity. There was limited uniformity in defining identity in the publications. A recurrent theme was, that identity is a social construct and storytelling is the vehicle through which it is navigated. Language and communication are essential in this process.

Conclusions

The model of Narrative Identity might be useful to clarify identity and its dynamic nature, since it integrates various theories of identity referred to in the publications. Different aspects of identity should be considered in future research to add to existing knowledge of identity changes and formation in people with aphasia and to tailor future interventions if necessary.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Identity formation is a complex and ongoing process for people with post-stroke aphasia, significantly influenced by language disorders. Continuous attention to this process is essential during rehabilitation.

Effective interventions include peer support through aphasia groups and elicitation of personal narratives, prominently through Guided Self-Determination, Biographic Narrative Intervention, and the My Story project.

People with aphasia exhibit diverse experiences, encompassing internal variation and ambiguity within themselves, while concurrently navigating dilemmas throughout the process of identity formation.

The “Narrative Identity Model” might be useful to comprehend identity and its dynamic nature, since it integrates various theories of identity referenced in publications about identity changes in people with aphasia.

Introduction

A sudden event like a stroke shifts a person’s life story and causes identity changes. Aphasia is a language disorder that affects the ability to communicate and occurs in approximately 30% of all stroke survivors [Citation1]. Communication is crucial in identity formation. Thus, for people with aphasia (PWA), there is an even greater challenge to reshape identity [Citation2]. This review focuses on the published literature about identity formation in PWA.

Theories of identity formation

In the literature different definitions are used to define the concept of identity. Moreover, the terms “identity” and “self” are often used interchangeably. Since the narrative turn in the social sciences in the 1970s and 1980s, identity has often been explained in the literature from the perspective of social constructionism. Social constructionism assumes that our knowledge of the world, including the understanding of human beings, is a product of human thought rather than rooted in an observable, external reality [Citation3]. The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur [Citation4] has had a major influence on this narrative turn in the humanities [Citation5]. According to Ricoeur [Citation4], people construct an understanding of who they are by giving meaning to the stories they exchange with others. This is what he calls narrative identity. Narrative identity is formed relationally and situationally in the present (synchronic) and evolves through time (diachronic) [Citation4]. Identity is shaped by creating narratives mediated through social interaction. Accordingly, the concept of identity is strongly interrelated with narrative [Citation2].

Also introduced in the 1970s and 1980s by psychologists Tajfel and Turner [Citation6] and consistent with social constructionism is social identity theory. This theory is frequently used in studies on stroke and identity changes to understand identity formation. Social identity theory is based on the concept that identity is shaped through group membership [Citation6]. The social groups to which an individual belongs can shape the understanding of self by being internalized, thereby influencing identity formation.

This means that social categories such as gender, health condition, or disability partially define identity. The sudden onset of a health condition such as stroke, during which an individual may lose social identities (for instance, being an able-bodied person), can threaten identity formation [Citation7]. For PWA, identity formation becomes even more threatened as a consequence of their communicative impairments.

In the field of aphasia and identity formation, Barbara Shadden substantially influenced the current theoretical background for understanding identity formation in PWA. She and her colleagues introduced the Four-Domain Interdisciplinary Framework [Citation8] designed to discuss the narrative self after the onset of neurogenic communication disorders such as aphasia. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only interdisciplinary framework to consider identity changes after stroke and aphasia. This framework addresses four dimensions of everyday life (cultural aspect, roles, situational interactions, biography) as well as the underlying concepts from which the self is constructed (agency and power), and provides professionals with consistent, universal terminology to discuss identity. This framework was also established from the perspective of social constructionism, such as Ricoeur’s narrative identity theory and Tajfel and Turner’s social identity theory, but specifically focused on people with communication disorders. Therefore, we use the Four-Domain Interdisciplinary Framework [Citation8] as a foundation for reviewing the literature on aphasia and identity.

Language disorders have an enormous impact on identity and identity formation [Citation2,Citation8,Citation9], since narrative identity is formed through the stories we share with others. Storytelling is a complex process that requires cognitive, language, and motor skills [Citation8]. Furthermore, people need the capacity to interpret and employ different nonverbal behaviors and the awareness of self and others in order to choose what will be shared with whom under what conditions.

Research on identity changes after stroke

Considerable research has been performed on identity changes after stroke. Important stroke-related themes that emerged in these studies were change of self-perception in relation to the pre-stroke self, coping with a new life and disability [Citation10–14], a disruption of body and self [Citation11,Citation14], and a change of meaning in life [Citation12]. Stroke survivors viewed themselves as significantly less independent, satisfied, and active [Citation10]. Many survivors lead more home-centered lives with reduced social relationships and are less actively involved in their communities [Citation10–12,Citation14].

However, it should be mentioned that PWA are often excluded from identity-related research because of their communicative impairments. Inclusion criteria often impose high demands on communicative ability of the participants. In some studies, communicative impairments are not mentioned [Citation9]. Not all studies exclude individuals with aphasia. In the studies performed by Kitzmüller [Citation13] and Pallesen [Citation14], 20 to 45% of participants had aphasia. Yet, the analysis did not differentiate between experiences of PWA and stroke survivors without aphasia. Ultimately, studies on identity changes after stroke are biased toward stroke-survivors who were able to share their stories. PWA encounter additional obstacles to reshaping their identity compared to people with stroke without aphasia due to their communication difficulties. Therefore, more knowledge about the precise impact of language disorders on identity formation of PWA is required. The importance of integrating identity-related issues into the study of PWA is underlined by several researchers [Citation8,Citation9,Citation15]. In the existing literature, regarding the experiences of PWA concerning identity changes and identity formation, various terms are used to define identity and salient themes. Greater knowledge and consistency of the concept of identity are required in order to compare studies or build on existing knowledge.

Changes in psychosocial functioning in aphasia

A better understanding of identity changes in aphasia is urgently required because a threatened identity is considered one of several psychosocial challenges faced by PWA [Citation16,Citation17]. PWA are especially susceptible to changes in psychosocial functioning because of their communicative difficulties. In addition to identity changes, PWA experience reduced social interaction, social isolation, unemployment and withdrawal from leisure activities [Citation16,Citation17]. Furthermore, suicide risk after stroke is reported to be as high as 73% [Citation18] and a large number of people with stroke experience anxiety (32%) [Citation19] and depression (23%) [Citation20]. Alarmingly, the prevalence of anxiety and depression among individuals with aphasia following a stroke is higher compared to those without aphasia. Among individuals with aphasia, 44% experience anxiety [Citation19], and they are 7.5 times more likely to develop depression than stroke survivors without aphasia [Citation20]. Changes to mental health and wellbeing extend beyond the PWA, with family members experiencing depression at prevalence rates of 46% [Citation21].

These psychosocial issues have a distinct effect on recovery, the psychosocial adjustment process, and the reaction to rehabilitation [Citation16,Citation22]. Consequently, the need for appropriate mental health services is substantial in PWA. In addition, several stroke clinical guidelines emphasize the need for general psychological care for PWA, (i.e., monitoring and assessment of emotional needs with validated instruments and triage to psychological care tailored to the person’s needs if required [Citation23–26]). Stepped psychological care can include various levels of support, such as mental healthcare for moderate to severe mental illness, to less intensive psychological care such as peer support through aphasia groups and counseling [Citation27]. PWA express great need for positivity, supported communication, and access to customized therapy [Citation28]. Nevertheless, they are currently attempting to navigate their way through communication and mood problems with limited psychological support and services in stroke rehabilitation.

Healthcare and support of identity formation

Healthcare professionals agree on the value of focusing on psychological care, including support of identity formation in PWA. Although they believe they are in a position to contribute to identity support, healthcare professionals experience barriers to addressing identity issues. They state that they do not possess the knowledge or skills to conduct such activities [Citation2]. Within healthcare, support of identity formation is often referred to specialists like clinical psychologists because it is considered to be beyond the area of expertise of most healthcare professionals [Citation29]. Furthermore, healthcare professionals state that they lack understanding of aphasia and how to support communication, and also that consultations with PWA are time consuming [Citation30]. However, the stepped psychological care model indicates that at level one (subthreshold problems) and level two (mild and moderate problems) therapy can be provided effectively by both psychologists and other healthcare professionals specializing in stroke. Not until level three (severe and persistent disorders of mood) is psychological care restricted to clinical (neuro)psychology and/or psychiatry [Citation27]. While psychologists and psychiatrists have professional expertise in the management of severe mood disorders, skill in supportive communication is of major value for PWA. They require support from their communication partner to formulate their stories [Citation2,Citation8], and they miss the narrative skills to do so without help [Citation31]. In this regard, speech-language pathologists can play an essential role since they are uniquely equipped to facilitate PWA to share their stories [Citation2]. Healthcare could be optimized if there was more knowledge about support of identity formation and communication of PWA across all disciplines.

Conclusively, aphasia may profoundly affect identity formation. Aphasia management could be optimized if there was increased knowledge about identity changes of PWA. This scoping review attempts to fill this gap by evaluating how the concept of identity, identity changes and identity formation is addressed in the existing literature concerning PWA. The goal is not only to provide a comprehensive overview of existing knowledge on identity and aphasia, but also to clarify how these findings can inform clinical practice.

Methods

A scoping review was conducted to explore the literature on identity and aphasia. Scoping reviews are appropriate for examining broad topics and mapping key concepts [Citation32]. Furthermore, research gaps in the existing literature can be identified. The terminology and methodology used was largely consistent with the PRISMA statement extension for scoping reviews [Citation33,Citation34]. In the final stage of the review process, we consciously diverged from PRISMA terminology. We used the term “reports” rather than “studies” in the final results. This decision was motivated by the fact that the inclusion criteria for this search were broad and included works such as book chapters in addition to peer-reviewed research. The methods used in the current scoping review will be explained according to the five stages of the methodological framework of Arksey and O’Malley [Citation32].

Stage 1: identifying the research question

The research question for this review was: What knowledge is available in the literature on the concept of identity, identity changes and identity formation of people with post-stroke aphasia and how do they integrate these changes in their lives?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Published scientific literature was searched on 19 October 2023 via electronic scientific databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library). Additionally, the yielded articles’ reference lists were searched to obtain a comprehensive set of literature on this topic. Multiple databases were searched given the nature of the topic and its applicability to diverse disciplines. The research team developed a list of search terms based on orientation searches, which led to search outcomes that best fit the research question. A library expert was consulted for advice on search strategies in the electronic databases. A strategy for searching PubMed was used as the main protocol and modified for other databases.

Since various terms were used to define identity and salient themes, we chose to conduct a broad search by using different keywords to find all studies in which identity changes might be discussed. Therefore, all studies on “life change events” and “personal experiences” were included because possible consequences may have been described in relation to identity. We used “personal narratives” as a keyword to do justice to the interrelationship of narrative and identity [Citation2]. The databases were searched using a search string consisting of two parts and five keywords (). Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used when applicable. Databases were also searched by utilizing Title Abstract terms (TiAb) to find articles not yet indexed with MeSH in the databases. No publication date restriction or other filters were used in the search, ensuring no relevant results were missed.

Table 1. Strategy for searching PubMed.

Stage 3: study selection

In the study selection phase, the relevance of the records was assessed in two steps: title and abstract level, and full text level. In these two selection steps, the first author (RB) assessed all the records, the co-authors (CL, KN, MC) assessed one third of the records independently of RB. Predefined inclusion criteria at the title and abstract level were: (a) PWA as the target group, (b) personal narratives, identity, and dimensions of the self as a main theme, (c) experiential knowledge and life change events as sub-themes and (d) publications written in Dutch or English. During the title and abstract selection step a four-point scale was used (0 = irrelevant; 1 = possibly relevant; 2 = partially relevant as the sub-themes of criterion a and c had been met; 3 = relevant as criterion a and b had been met). Discussion took place and consensus was pursued when scores between the researchers differed. All records with scores of 2 or 3 were included in the sample. Subsequently, any uncertainties to this point in the review process had not precluded records for assessment at the full text level.

During the title and abstract selection step, the concept of identity was taken broadly to ensure that no records would be inadvertently missed. During the full text selection step, the same procedure was followed, but the inclusion criteria for this level were further specified. To do so, a small subset of four reports was selected as idealized examples. In this way, a demarcated selection was performed to further specify inclusion criteria. The demarcated selection consisted of reports where the research frame focused specifically on identity and/or narrative, and the concept of identity was operationalized in the theoretical framework or elaborated on in the discussion. The final inclusion criteria were: (a) reports in which identity was the aim of research and/or operationalized in the theoretical framework, (b) reports with an open frame focused on “experiences” in which identity was one of the outcomes and was elaborated in the discussion, (c) reports on the dimensions of everyday life and underlying concepts of the self, discussed in relation to identity, and (d) narrative reports discussed in relation to identity. Only peer-reviewed academic publications and books published by academic publishers were included in the sample; therefore, we chose to exclude experiential stories written by PWA. The inclusion of reports was not limited by the design and/or methodological quality of the research. A three-point scale was used during the full text selection step (0 = irrelevant; 1 = possibly relevant; 2 = relevant as all inclusion criteria had been met). Each report was discussed by the first author and one of the co-authors to decide upon inclusion or exclusion. Inconsistencies and uncertainties were discussed within a research team meeting with all four researchers, who also checked the report for the selection criteria. The reference lists of the reports included in this third step were checked for additional relevant reports. This yielded two additional reports.

Stage 4: charting the data

After the final full text inclusion, a data extraction form was developed based on all full texts and a research team consultation. This data extraction form consisted of descriptive elements (author, year, study aim, theory of identity, study design, data collection, data analysis, study population, age, months post onset, and findings). The first author (RB) charted the data. The co-authors (CL, KN, MC) each assessed one third of the results independently of RB. Subsequently, patterns and inconsistencies were discussed in a research team consultation.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

A summary was made of the main characteristics of the reports, using the descriptive elements of the data extraction form. Thereafter, the researchers conducted a numeric [Citation31] and thematic analysis [Citation35] of the information in the reports. The numerical analysis captured the prevailing areas of research with respect to geographical location, research design [Citation31] and characteristics of the study population regarding age, gender and months post onset. The first phase of the thematic analysis focused on obtaining an overview of data coverage to become familiar with the data [Citation36]. The first author (RB) read all reports; the other three researchers (CL, KN, MC) read one third of the reports independently of RB. Text fragments related to the research question of the scoping review were highlighted and coded using free-line-coding [Citation35]. The coded excerpts from the reports that contained relevant qualitative information about identity and aphasia were independently placed in an Excel file. Based on discussion, a final Excel file including all relevant codes was developed. In the second phase, the codes were independently sorted into related areas by the research team and descriptive themes were named that were close to the findings in the primary reports. The third phase focused on generating new interpretive constructs and explanations by developing analytic themes [Citation35].

Results

Based on the initial 492 records in the databases, 49 reports were included in the full text phase and assessed for eligibility. Reports were excluded when they involved experiential stories written by PWA, the frame of research was not focused on identity, or narratives and/or identity were not operationalized in the theoretical framework. Also, duplicated reports published in two separate publications were excluded for analysis. Eventually, 20 reports were included in this review (), published between 1964 and 2023.

Figure 1. Number of publications included in each step of the review. Based on the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [Citation37].

![Figure 1. Number of publications included in each step of the review. Based on the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [Citation37].](/cms/asset/95d378b9-6853-47cf-85da-3630b88bb956/idre_a_2367606_f0001_c.jpg)

Summary of the reports included in the review

The final set of reports included 3 book chapters published by academic publishers, 5 theoretical papers, and 12 empirical papers from peer-reviewed journals. Detailed descriptions of these reports can be found in (Appendix A), which lists the authors, year, country, study aim, design, population, and findings, organized by year to illustrate the evolution of the research field. Additionally, (Appendix A) offers a descriptive summary of the theories used in the reports, outlining definitions and theoretical premises of identity.

Book chapters

The three book chapters represent the work of two author groups, Shadden and colleagues [Citation8], as well as Pound and colleagues [Citation38] ranging in dates from 2008 to 2018. Shadden et al. [Citation8] focus on adapting narrative theory to aphasia. In general, these two chapters explain how the Four-Domain Interdisciplinary Framework designed to discuss the narrative self can pertain to PWA [Citation39] with examples provided [Citation40]. Shadden et al. [Citation39] prefer the term “self” over “identity,” viewing “self” as a more holistic and personal concept, described as “a personal project.” They associate identity primarily with the dimension of roles [Citation39].

Pound et al. [Citation38] explore theory of identity and therapeutic approaches focused on promoting personal growth, self-exploration and self-actualization. They categorize identity into three types: personal, social, and collective. Additionally, Pound et al. [Citation38] highlight how unfamiliarity with aphasia in society poses a barrier for PWA in accessing services.

Theoretical papers

The five theoretical papers present the work of Shadden and colleagues [Citation2,Citation41–44]. Four of these papers [Citation41–44], ranging in dates from 2004 to 2007, mirror the content found in the book chapters described in the previous paragraph. In these chapters, the theories and definitions of identity used in the four theoretical papers appear to result in the Four-Domain Interdisciplinary Framework of the narrative self [Citation8]. The topics discussed in the papers are: identity related to aphasia and the impact on life participation and integration in the Life Participation Approach to Aphasia (LPAA), as well as a review of concepts from sociocultural literature in order to understand the consequences of aphasia and the impact of aphasia on storytelling and self.

In the first paper, Shadden and Agan [Citation41] provide an overview of varied interventions addressing identity issues. In the second paper, Shadden [Citation42] refers to theory of Taylor [Citation45] to define identity, and the impact of aphasia on identity is discussed. In the third paper Shadden and Hagstrom [Citation43] discuss different concepts and theories found within psychological, communication, and sociological literature to understand narrative identity. Among others, they incorporated Holstein and Gubrium’s [Citation46] theory of self, McAdams [Citation47] theory of narrative identity, and Frank’s theory of narrative types [Citation48]. In the fourth paper Shadden and Koski [Citation44] synthesize various theories to understand the impact of aphasia on storytelling and self, employing Holstein and Gubrium’s [Citation46] theory of self and Giddens’ [Citation49] theory of self-identity. Finally, the fifth paper by Strong and Shadden [Citation2], published in 2020, provides an overview of available narrative interventions and utilizes narrative theories from Taylor [Citation45], McAdams [Citation47], Bamberg [Citation50], and Bruner [Citation51].

Empirical papers focused on identity changes

Among the 12 empirical papers, three were specifically dedicated to exploring identity changes in aphasia. These papers range in dates from 2015 to 2020. Musser et al. [Citation52] conducted interviews with 24 individuals affected by aphasia following a stroke, utilizing a grounded theory approach. Taubner et al. [Citation9] investigated identity shaping in nine working-age people with chronic aphasia in a digitalized society. They incorporated Giddens’s [Citation49] theory of self-identity along with Bamberg’s dilemmatic-space theory [Citation50] to understand the concept of identity. Their methodology included both interviews and participant observation. Guerrero-Arias et al. [Citation53] conducted a case study on the intersectional identities of a participant (a black, middle-aged, Colombian woman of low socio-economic status) and how these related to social interaction. They employed Norton’s social identity theory [Citation54] and Crenshaw’s intersectionality theory [Citation55] as frameworks to analyze the concept of identity.

Empirical papers focused on identity interventions

Five studies were specifically focused on identity interventions. These ranging in dates from 2010 to 2018. Simmons-Mackie and Elman [Citation56] employed discourse analysis to pinpoint significant interactions during a group aphasia therapy session. They drew on Shadden and Agan [Citation41] to define identity, and on Pound et al. [Citation57] for theory of identity, differentiating between personal, social, and collective identity.

Bronken et al. [Citation58] explored experiences of PWA who participated in an intervention aimed at supporting the process of psychosocial adjustment and enhancing psychosocial well-being. They drew on narrative theory from Frank [Citation48], Bruner [Citation51], and Polkinghorne [Citation59]. The intervention was based on Zoffmann’s [Citation60] “Guided Self-Determination” principles, and structured as an individual, dialogue-based collaborative process. The contents addressed different psychosocial issues such as mood, social relationships, meaningful activities, identity, and body changes. Employing a longitudinal, complex health intervention development design, the study incorporated participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and standardized clinical assessments involving seven individuals in the subacute stage of aphasia.

Bronken et al. [Citation61] utilized participant observation and semi-structured interviews. Their aim was to elucidate the interactive process of narrative co-construction between a young woman with aphasia and a nurse during the first year after stroke, as part of a longitudinal psychosocial intervention. The intervention was based on Zoffman’s [Citation60] “Guided Self-Determination” principles. Bronken et al. [Citation61] employed the narrative theories of Frank [Citation48], Bruner [Citation51], Polkinghorne [Citation59], and Ricoeur [Citation62]. Additionally, they used Holstein and Gubrium’s [Citation46] theory of self, and Bury’s [Citation63] theory of biographical disruption in their report.

Corsten et al. [Citation15] evaluated and adapted an interdisciplinary biographic-narrative intervention, and investigated how this intervention influenced identity negotiation and quality of life in aphasia using a mixed-methods design. They incorporated McAdams [Citation47] and Bauer et al.’s [Citation64] narrative theory, and Bury’s [Citation63] theory of biographical disruption within their theoretical framework. Corsten et al. [Citation15] employed quantitative measures of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL) in 27 PWA, and they conducted interviews to gain a deeper understanding of identity formation in PWA.

Lastly, Strong et al. [Citation65] explored experiences of PWA who had participated in the My Story project, aimed at co-constructing personal narratives about living with aphasia. They utilized Taylor’s [Citation45] definition of identity and Ricoeur’s [Citation4,Citation62,Citation66] and McAdams’ [Citation47] theory of narrative identity within their theoretical framework. Strong et al. [Citation65] used a phenomenological design, conducting semi-structured interviews in three middle-aged men with chronic aphasia.

Empirical papers focused on narratives

The remaining four empirical papers represented reports, ranging in dates from 2006 to 2012, that were not specifically designed to investigate identity in PWA. Instead, they utilized a narrative approach to explore lived experiences of PWA. These studies were incorporated into this review due to the interrelationship of narrativity and identity [Citation2,Citation15], with identity issues emerging as outcomes elaborated upon in the discussion.

Hinckley [Citation67] conducted a review encompassing twenty published accounts authored by PWA, available in books and peer-reviewed journals. The objective was to discern the elements contributing to successful living with aphasia post-stroke. In the review, Hinckley [Citation67] employed Frank’s [Citation48] theory of narrative types and Bury’s [Citation63] theory of biographical disruption.

Barrow [Citation68] conducted a case study examining the role of disability narratives in a middle-aged woman with chronic aphasia and her proxies to understand their understanding of stroke and aphasia. Barrow incorporated Frank’s [Citation48] theory of narrative types, Somers’ [Citation69] narrative theory, as well as Corker and French’s [Citation70] theory on the narrative voices of disability in her work.

Mitchell et al. [Citation71] explored various narrative types and metaphors employed by eleven PWA. They integrated Frank’s [Citation48] theory of narrative types, Bury’s [Citation63] concept of biographical disruption, and Ricoeur’s [Citation4] theory of narrative identity within their theoretical framework to gain deeper insights into the narratives.

Finally, Armstrong et al. [Citation72] used a narrative approach to understand how Aboriginal Australian people adjusted to aphasia over time, interviewing three middle-aged males in the chronic stage of aphasia. Armstrong et al. [Citation72] underscored the importance of a holistic and narrative approach to understanding the experiences and stories of people with disabilities across diverse cultures, drawing on Hinckley [Citation73].

Descriptive summary of the reports

The empirical papers comprise a range of different settings and population characteristics as shown in . Most research took place in the chronic phase of aphasia (> 6 months post onset). Of the 12 empirical studies, 95 participants were recruited through speech-language pathologists, from ambulant rehabilitation and aphasia support groups or advertising via an aphasia association. In three studies, participants were included in the rehabilitation phase (from >1 months post onset). These participants joined an intervention program in a hospital [Citation52,Citation58,Citation61]. As for the review, only personal narratives (co-)authored by PWA that had been published in a book or professional journal were included [Citation67]. Often it was unclear whether people lived independently at home or were resident in a nursing home. Age varied from 30 up to 78 years old. In four studies, the focus was on middle-aged PWA [Citation9,Citation65,Citation68,Citation72], age ranging from 35 to 65 years [Citation74]. Two case studies focused on young women [Citation53,Citation68]. In the other studies, life stage and age were not considered or not substantiated. Additionally, there was a discrepancy between the proportion of men and women who were included in the studies; 31 women were included against 64 men. Gender was not substantiated for in the review [Citation67]. Furthermore, most studies were conducted in Western countries, mostly in the USA. One study was carried out in Colombia [Citation53]. In this study, social economic status and cultural background were considered. Information on social economic status was provided in one other study [Citation52]. Cultural background was considered in an Australian study on Aboriginal PWA [Citation72] and an Irish study [Citation68].

Perspectives on identity and identity formation

In this review the different approaches to the concept of identity used in studies on identity changes of PWA are analyzed. The following perspectives on identity and identity formation were based on the theoretical background on identity formation from all 20 included reports. The analysis revealed that various theories and definitions were used to describe identity. There was limited uniformity in the definition of identity in the articles. Thus, some authors refer to the “self,” others to “narrative self” [Citation8] or “narrative identity” [Citation15], while some distinguish between different types of identity such as “self-identity” [Citation9], “personal identity,” “social identity,” “collective identity” [Citation40,Citation56], “chronotype,” and “intersectional identity” [Citation53] or “occupational identity” [Citation52]. Additionally, different synonyms are used for identity “formation” (e.g., “renegotiation,” “shaping,” “construction,” “adaptation,” “adjustment,” and “development”). Furthermore, identity is interpreted differently between disciplines. In the studies, many different authors and theories are cited to describe identity. This proves identity to be a complex concept which is challenging to define.

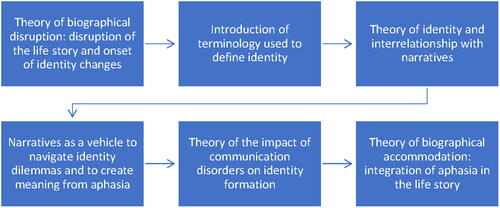

However, there is also consistency in the theories cited and how they are used throughout the studies. In most studies, the concept of identity is explained in sequential steps (). Explanation starts at the origins of post-stroke aphasia, that is, the biographical disruption theory introduced by Bury [Citation63]. The semantic term used for identity in the article is then explained, and the concept of identity is discussed. Identity is clarified using the following theories: “narrative identity” [Citation4,Citation15,Citation47,Citation62,Citation66], “narrative self” [Citation8], “self-interpretation” [Citation45], “self-identity” [Citation49], “self-narrative” [Citation51], “social identity” [Citation54], “dilemmatic space” [Citation50] and “intersectionality” [Citation55]. Subsequently, the interrelationship between narrative, co-construction, and identity is elaborated. Most studies employ narrative theory from Ricoeur [Citation4,Citation62,Citation66], and/or McAdams [Citation47] for this purpose. Furthermore, theory of different types of narratives is discussed: “big and small stories approach,” i.e., “everyday narrative” versus “life story narrative” [Citation2,Citation50], and “illness narratives” as a vehicle to integrate aphasia into the life story narrative [Citation48]. The impact of communicative difficulties of PWA on the construction of narratives and thus on identity formation is also discussed. Finally, the eventual goal of integrating aphasia into the life story and moving forward with one’s life, i.e., biographical accommodation, is explained [Citation40].

Figure 2. Step-by-step introduction of theory of the concept of identity in the reports.

The principal commonality between the theories used in the studies is that identity is considered a social construct, with storytelling as the navigating vehicle. Language and communication are an essential part of this process. Identity is negotiated in situational interactions in the present and evolves through time [Citation4,Citation39]. Life events are integrated into the life story, ensuring its continuity. Life story is influenced by one’s biographical characteristics i.e., gender, life stage, personality, physiology, and life history [Citation39]. People have agency in how they present their identity in different social situations and roles. However, this does not mean that the self is always consciously created. The self is also formed as a result of our actions, rather than a conscious creation [Citation39].

Another commonality in the studies is PWA’s struggle with societal perceptions of disability. PWA are faced with an abrupt change of their identity. Suddenly, they become “disabled” and are challenged by the cultural perspectives on illness and disability [Citation38,Citation40,Citation53,Citation68]. Often, cultural definitions of disability are associated with negative labels, i.e., stigmatization [Citation38]. Common manifestations of stigma include perceptions of incompetence, dependence, perceived lack of agency and reduced social appropriateness [Citation39]. Many PWA lack the agency, and power to negotiate and create an identity that is accepted by others [Citation39].

A final commonality is that in all studies identity is described as dynamic and subject to change. However, the areas of tension and interrelationship between different aspects or dimensions of identity are not always reflected in the definitions used in the articles. It becomes clear from how identity is introduced in the literature that it is of interest to relate multiple perspectives. As mentioned earlier, identity seems to be best explained in sequential steps (). This corresponds to the process of “maintaining and modifying life story and narrative self” [Citation8] in which the following steps are represented: life story and narrative self, disruptive event, illness narratives, and biographical accommodation.

Thematic summary of identity changes and challenges

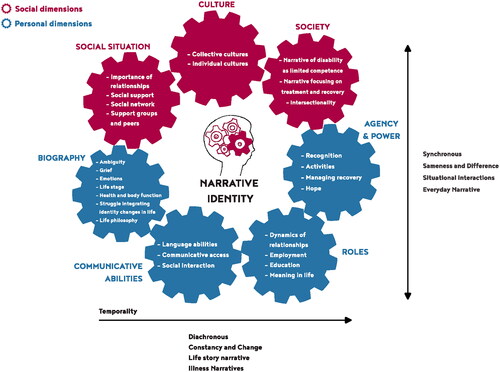

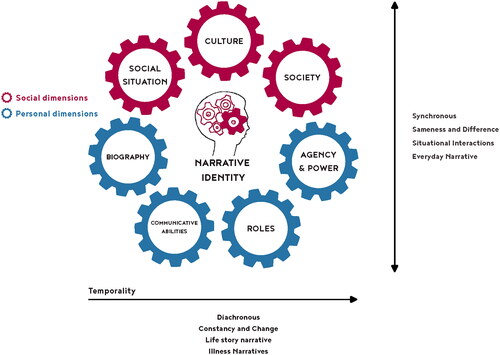

Within the studies, different research designs were used, and the results were analyzed by different disciplines from different perspectives. As a result, we found considerable variety in themes. These themes are systematically presented in (Appendix A), which presents overarching themes, sub-themes and examples from the reports in a structured manner. However, this tabular representation lacks the representation of the dynamic and interwoven nature of identity, leaving the interrelationships between these themes concealed. A further step was taken in this regard by attempting to synthesize the aforementioned complementary theories into the “Narrative Identity Model” (), to achieve an appropriate description of identity.

Figure 3. The “Narrative Identity Model.”

The “Narrative Identity Model”

The “Narrative Identity Model” depicts:

Identity as a social construct with storytelling as the navigating vehicle and language and communication as an essential part of this process.

Dimensions and underlying concepts of the interdisciplinary four-domain framework of Shadden et al. [Citation39].

Challenges that PWA experience while navigating their new identities based on Bamberg’s dilemmatic-space theory [Citation50] and Ricoeur’s narrative identity theory [Citation4,Citation62,Citation66].

The bottom of the model represents the “I” (personal dimensions) and the top represents the “We” (social dimensions). Narrative identity becomes visible in interaction with others at the intersection of the “I” and the “We” (illustrated by the head containing interconnected gears). The “I” refers to the personal dimensions: roles, communicative abilities, agency and power, and biography such as personal and physical characteristics and life story. The social dimensions refer to the social groups a person belongs to, culture e.g., norms, values, and semiotic signs (language and communication), and society or the world we belong to. The horizontal arrow represents temporality and refers to diachronic identity formation. The vertical arrow indicates synchronous identity formation in the present moment.

The “Narrative Identity Model” employs gears in different colors to represent themes related to narrative identity that interact. The themes are based on the analysis of the reports included in this review. The gears signify not only the interaction between the bottom “I”—personal dimensions, symbolized by blue gears—and the top “we”—social dimensions, symbolized by red gears—but also the interactions across various personal and social dimensions. This visualization underscores the dynamic interplay across dimensions, rather than depicting distinct selves.

The interactive relationship between the “I” and the “We” in the “Narrative Identity Model” is inspired by Ruijters et al.’s [Citation75] “Professional Identity Model,” which is based on research outside the domain of aphasia. Ruijters et al. [Citation75] distinguish between the personal, social, and collective self, using frames and half circles to depict interactions between the bottom half (“I”) and the top half (“We”). The themes in their model differ from those in the “Narrative Identity Model,” indicating that different themes influence the formation of narrative identity compared to professional identity.

Overview of sub-themes in the Narrative Identity Model

The Narrative Identity Model attempts to visualize the dynamic nature of identity and the challenges PWA face while navigating their new identities. PWA experience inner variation within themselves. They consistently explain their experiences in relation to a broader context, which is why an experience can be labeled in different ways. Change can be both positive and negative, or cause sadness while simultaneously promoting growth. This reflects the ambiguous nature of living with aphasia [Citation9,Citation53,Citation68] and demonstrates that one experience never excludes another. Recognizing the importance of addressing this ambiguity and the challenges PWA encounter in reshaping their identity, we incorporated the sub-themes in the “Narrative Identity Model” (). This addition emphasizes how these themes interact and influence each other, highlighting the dynamic and multifaceted nature of narrative identity formation in PWA.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to provide an overview of existing knowledge on the concept of identity and identity changes and formation of PWA by exploring existing research on identity of PWA. In total, 20 reports were included, encompassing various types of reports (book chapters, theoretical papers, and empirical studies focused on identity changes, interventions, and narratives).

The findings revealed a range of different:

settings

population characteristics

frames and research designs to understand identity

theories and definitions to describe identity

themes regarding identity changes in PWA

The renowned framework of Arksey and O’Malley [Citation32] was used to systematically conduct this scoping review.

Theory of identity

In this review, various approaches to the concept of identity used in studies on identity changes in PWA were analyzed. Different terms and definitions were employed in the reports to describe identity. The analysis revealed that these approaches ultimately converged around a shared underlying construct, grounded in social constructionism as outlined in the introductory chapter. Whether authors refer to “self-identity,” “narrative identity,” or “social identity,” they all serve as lenses through which the socially constructed nature of identity in PWA is viewed.

Overall, the analysis of the reports provides several insights regarding identity changes in PWA. Following the onset of post-stroke aphasia, PWA experience biographical disruption and face identity changes [Citation63]. Identity formation is a dynamic and interactive process where communication plays a crucial role, presenting additional challenges for PWA [Citation2]. During the process of identity formation, PWA must navigate dilemmas both in situational interactions (synchronous) and through time (diachronous) [Citation4,Citation50,Citation62,Citation66]. PWA experience inner variation and ambiguity within themselves, implying that change can be both positive and negative simultaneously [Citation9,Citation53,Citation68]. PWA require time to integrate aphasia into their lives (biographical accommodation), with their biography, communicative abilities, and agency and power influencing the process [Citation39,Citation40]. Aphasia profoundly impacts the roles individuals fulfill and meaning in life, as well as their social network. Moreover, societal perceptions of disability and cultural background significantly shape identity formation [Citation53,Citation68]. Recognition emerges as a fundamental need, yet PWA may lack agency to present themselves as they desire, potentially causing stigmatization [Citation39]. The insights from the analysis are captured in the proposed “Narrative Identity Model,” which visualizes the interactive and dynamic nature of narrative identity formation among PWA, addressing its inherent ambiguity, the dilemmas faced, and the pivotal role of language.

Similar to Shadden et al. [Citation39] we view identity as part of the self. Analoguos to Ruijter et al.’s [Citation75] definition of professional identity, we consider narrative identity as that which inextricably identifies you as the person you are at the intersection of the personal and social dimensions. The head containing interconnected gears in the model serves as a reflection of one’s unique life story at this particular moment. Based on the analysis of the reports included in this review, we found, like Bamberg [Citation50], that narrative identity emerges from the diachronic navigation of constancy and change and evolves through time. Moreover, we prefer identity formation above reconstruction or renegotiation. Besides the conscious nature of identity formation, this term also does justice to the unconscious part of the process.

The search process

Conducting a search for literature on identity changes in aphasia was challenging due to the varied definitions of identity within the literature, a concept that encompasses many dimensions of daily life. We used multiple synonyms to ensure that all relevant publications on identity changes in aphasia were included. However, despite the rigorous search process, some studies may have been missed. In line with the aim of this scoping review, we opted not to examine the quality of the studies reviewed. Therefore, the results should be perceived as existing theories and themes that are important when considering the concept of identity and identity changes in aphasia.

Population characteristics

Current research on identity changes in aphasia tends to focus on middle-aged PWA from Western cultural backgrounds. Also, more men than women are included in the studies and socioeconomic status is often not mentioned. Thus, little is known about the effects of intersectionality on identity formation of PWA, reflecting the marginalization of minority groups in both society and research. Moreover, most participants had received rehabilitation, were a member of an aphasia association, and/or were still attending therapy. This may have led to PWA, who have no access to therapy, being missed and may have affected the results.

In addition, the domestic situation of PWA was often not accounted for, even though it affects their position in the world and thus their navigation of agency to fit [Citation50]. Notably, there is a lack of studies focusing on elderly PWA in nursing homes or those with early-onset aphasia, and how these conditions impact identity formation. Finally, most PWA were in the chronic phase, where aphasia might be more integrated into their life stories. This integration may result in aphasia being represented in their narratives in a different manner, influencing the reported experiences [Citation72].

Credibility

A major challenge for PWA regarding identity formation is their reduced language capacity, which complicates their ability to share narratives and reshape their identity. Furthermore, communication difficulties also hinder research on identity changes in PWA. Most studies rely on verbal data collection methods, such as interviews, during which communication was adapted to the needs of PWA. However, identity changes might be more comprehensively captured through a combination of verbal and nonverbal methods, such as the ethnographic studies conducted by Barrow [Citation68], Taubner et al. [Citation9] and Guerrero-Arias et al. [Citation53]. This methodological triangulation allows for a more holistic examination of identity changes and formation, incorporating observations and the use of objects to enhance understanding.

Interventions focused on identity formation

This review specifically addressed the concept of identity and themes related to identity changes and formation. The literature on interventions that focus on identity formation in PWA demonstrates that narrative interventions improve quality of life [Citation15], well-being [Citation58,Citation61] and support a positive view of identity [Citation65]. Additionally, narrative interventions contribute to an increased sense of competence and positive self-acknowledgement of PWA [Citation15]. These findings show that appropriate treatment approaches are available to support identity formation of PWA.

Strong and Shadden’s [Citation2] theoretical paper provides a clear up-to-date overview of available narrative interventions. No new or differing literature on narrative interventions and identity in PWA was identified in this scoping review. Therefore, we refer to their work for further details.

Clinical implications and future research

This review demonstrates that identity formation is a complex and ongoing process, especially for PWA, who suffer from language disorders. Healthcare professionals should be aware of that and of the need for continuous attention to identity formation of PWA during rehabilitation.

Research on identity changes in PWA often employs verbal data collection methods. However, this review suggests that a combination of verbal and nonverbal methods could capture identity changes more fully. Triangulation of methods allows us to comprehend the multiplicity and complexity of experiences of PWA and how aphasia affects their life [Citation76]. Additionally, the dynamics of how PWA’s narratives change over time in terms of identity has not been thoroughly explored. Therefore, we have initiated narrative inquiry combined with visual ethnography to longitudinally explore identity changes of PWA [Citation77].

The review also highlights a significant gap in understanding the effects of intersectionality on identity formation in PWA. Therefore, healthcare professionals should be cautious when applying these findings generally, as they may not accurately represent every PWA. In addition, it is important to address different aspects of identity in future research to add to existing knowledge of identity changes and formation in PWA and to tailor future interventions if necessary. This can be done by including more PWA from non-Western backgrounds. Culture affects identity formation and this may be reflected in experiences of PWA. Furthermore, socioeconomic status, the domestic situation of PWA, life stage, and gender should be accounted for in the studies to do justice to experiences of a broader, more diverse group of PWA. Moreover, it is important to ensure that groups who are not known to receive speech therapy or do not have access to therapy are included in research. Also, the studies showed that the severity of communication impairment and the phase after the onset of post-stroke aphasia may influence experiences of PWA. Therefore, it is important to take these into consideration in research.

Our focus was primarily on identity changes of PWA. We did not encounter any literature that explicitly addressed identity changes of significant others of PWA. However, they experience identity changes as well. Thus, it is valuable to explore their experiences in future research.

Finally, in this review we decided not to include personal narratives of PWA themselves, as these cannot be considered scientific literature. Consequently, the results are influenced by the interpretations of different researchers, meaning that an important unfiltered perspective—that of PWA themselves—was overlooked. One way to do justice to this important viewpoint could be to include PWA as a co-researcher in research on identity changes of PWA.

Conclusion

Our review found that the “Narrative Identity Model” could be used to clarify the concept of identity, since it integrates different theories of identity referred to in the literature on identity changes of PWA. Also, the model could be utilized as a tool to articulate the complexities and ambiguities inherent in identity changes. To date, research on identity changes in PWA has been limited, primarily due to the communication challenges they face, because their communication difficulties form an obstacle in research. Nevertheless, literature shows that addressing identity changes in aphasia is possible, especially when diverse research methodologies are integrated. In addition, growing evidence suggests that narrative interventions are effective in supporting identity formation and positively affect the quality of life of PWA. It is important for healthcare professionals to deepen their understanding of the identity changes experienced by PWA and to explore ways to support these changes in interdisciplinary settings, and enhance healthcare.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank library expert Carola van Aert for her advice on the search strategies in the electronic databases. The authors also thank Reno Huibers for the drawing of the head with interconnected gears in the “Narrative Identity Model” and Astrid Bontenbal for her assistance with designing the model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Berns PEG, Jünger N, Boxum E, et al. Logopedische richtlijn ‘Diagnostiek en behandeling van afasie bij volwassenen’ [Speech pathology guideline ‘Diagnosis and treatment of aphasia in adults’]. Woerden: Ned Ver Logopedie Foniatrie; 2015. Dutch.

- Strong K, Shadden BB. The power of story in identity renegotiation: clinical approaches to supporting persons living with aphasia. Perspect ASHA Special Interest Gr. 2020;5:371–383.

- Burr V. Social constructionism. New York (NY): Routledge; 2015.

- Ricoeur P. Oneself as another. Kathleen Blamey, Trans. Chigago (IL): University of Chicago Press; 1992.

- Ganzevoort R. Narratieve benaderingen in de praktische theologie [Narrative approaches in practical theology]. Tijdschr Humanis. 2011;12(47):61–70. Dutch.

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Jost JT, Sidanius J, editors. Political psychology. London: Psychology Press; 2004. p. 276–293.

- Haslam SA, Jetten J, Postmes T, et al. Social identity, health and well-being: an emerging agenda for applied psychology. Appl Psychol Int Re. 2009;58(1):1–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00379.x.

- Shadden BB, Hagstrom F, Koski PR. Neurogenic communication disorders. Life stories and the narrative self. San Diego (CA): Plural Publishing; 2008.

- Taubner H, Hallén M, Wengelin Å. Still the same? Self-identity dilemmas when living with post-stroke aphasia in a digitalised society. Aphasiology. 2020;34(3):300–318. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2019.1594151.

- Ellis-Hill C. New world, new rules: life narratives and changes in self-concept in the first year after stroke [dissertation]. Southampton: University of Southampton; 1998.

- Ellis-Hill CS, Payne S, Ward C. Self-body split: issues of identity in physical recovery following a stroke. Disabil Rehabilit. 2000;22(16):725–733.

- Hinojosa R, Boylstein C, Rittman M, et al. Constructions of continuity after stroke. Symb Int. 2008;31(2):205–224.

- Kitzmüller G, Häggström T, Asplund K. Living an unfamiliar body: the significance of the long-term influence of bodily changes on the perception of self after stroke. Med Health Care Philos. 2013;16(1):19–29. doi: 10.1007/s11019-012-9403-y.

- Pallesen H. Body, coping and self-identity. A qualitative 5-year follow-up study of stroke. Disabil Rehabilit. 2014;36(3):232–241.

- Corsten S, Schimpf E, Konradi J, et al. The participants’ perspective: how biographic-narrative intervention influences identity negotiation and quality of life in aphasia. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2015;50(6):788–800. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12173.

- Kirkevold M, Bronken BA, Martinsen R, et al. Promoting psychosocial well-being following a stroke: developing a theoretically and empirically sound complex intervention. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(4):386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.006.

- Parr S. Living with severe aphasia: tracking social exclusion. Aphasiology. 2007;21(1):98–123. doi: 10.1080/02687030600798337.

- Chun HYY, Ford A, Kutlubaev MA, et al. Depression, anxiety, and suicide after stroke: a narrative review of the best available evidence. Stroke. 2022;53(4):1402–1410. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035499.

- Morris R, Eccles A, Ryan B, et al. Prevalence of anxiety in people with aphasia after stroke. Aphasiology. 2017;31(12):1410–1415. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2017.1304633.

- Zanella C, Laures-Gore J, Dotson VM, et al. Incidence of post-stroke depression symptoms and potential risk factors in adults with aphasia in a comprehensive stroke center. Top Stroke Rehabilit. 2022;30(5):1–11.

- McGurk R, Kneebone II, Pit ten Cate IM. “Sometimes we get it wrong but we keep on trying”: a cross-sectional study of coping with communication problems by informal carers of stroke survivors with aphasia. Aphasiology. 2011;25(12):1507–1522. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2011.599528.

- Pompon RH, Mach H. Characterizations of resilience in poststroke aphasia: a scoping review and considerations for treatment and research. Top Lang Disord. 2022;42(3):236–251. doi: 10.1097/TLD.0000000000000285.

- Gilham S, Clark L. NHS improvement – stroke psychological care after stroke improving stroke services for people with cognitive and mood disorders. Leicester: NHSI; 2011.

- Lanctôt KL, Lindsay MP, Smith EE, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: mood, cognition and fatigue following stroke, update 2019. Int J Stroke. 2020;15(6):668–688. doi: 10.1177/1747493019847334.

- Informme.org.au/Guidelines [Internet]. Melbourne (Aust): Stroke Foundation; [updated 2023 Jul 28; cited 2023 Aug 15]. Available from: https:///#/guideline/WE8wOn/section/nyQ6Vn

- Strokeguideline.org [Internet]. London (UK): SSNAP; [updated 2023 Apr 4; cited 2023 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.strokeguideline.org/app/uploads/2023/04/NCGS-2023_Rehabilitation-and-recovery.pdf

- Kneebone II. Stepped psychological care after stroke. Disabil Rehabilit. 2016;18(38):1836–1843.

- Baker C, Worrall L, Rose M, et al. ‘It was really dark’: the experiences and preferences of people with aphasia to manage mood changes and depression. Aphasiology. 2020;34(1):19–46. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2019.1673304.

- Ellis-Hill C, Payne S, Ward C. Using stroke to explore the life thread model: an alternative approach to understanding rehabilitation following an acquired disability. Disabil Rehabilit. 2008;30:150–159.

- Baker C, Worrall L, Rose M, et al. Stroke health professionals’ management of depression after post-stroke aphasia: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabilit. 2021;43:217–228.

- Armstrong E, Ulatowska H. Making stories: evaluative language and the aphasia experience. Aphasiology. 2007;21(6-8):763–774. doi: 10.1080/02687030701192364.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. 2021;71:372.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Int Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- James T, Harde A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):1–10.

- Spencer L, Ritchie J, O’Connor W, et al. Analysis: practices, principles and processes. In: Ritchie L, Lewis J, McNaughton N, et al., editors. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. 2nd ed. London: SAGE; 2014. p. 199–218.

- Rethlefsen ML, Page MJ. PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S: common questions on tracking records and the flow diagram. J Med Libr Assoc. 2022;110(2):253–257. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2022.1449.

- Pound C, Parr S, Lindsay J, et al. Beyond aphasia: therapies for living with communication disability. London: Routledge; 2018.

- Shadden BB, Hagstrom F, Koski PR. The self. In: Shadden BB, Hagstrom F, Koski PR, editors. Neurogenic communication disorders. Life stories and the narrative self. San Diego (CA): Plural Publishing; 2008. p. 33–45.

- Shadden BB, Hagstrom F, Koski PR. Life stories in aphasia. In: Shadden BB, Hagstrom F, Koski PR, editors. Neurogenic communication disorders. Life stories and the narrative self. San Diego (CA): Plural Publishing; 2008. p. 137–174.

- Shadden BB, Agan JP. Renegotiation of identity: the social context of aphasia support groups. Top Language Disord. 2004;24:174–186.

- Shadden B. Aphasia as identity theft: theory and practice. Aphasiology. 2005;19(3-5):211–223. doi: 10.1080/02687930444000697.

- Shadden BB, Hagstrom F. The role of narrative in the life participation approach to aphasia. Top Lang Disord. 2007;27(4):324–338. doi: 10.1097/01.TLD.0000299887.24241.39.

- Shadden BB, Koski PR. Social construction of self for persons with aphasia: when language as a cultural tool is impaired. J M Speech-Lang Pathol. 2007;15:99–106.

- Taylor C. The politics of recognition. In: Gutman A, editor. Multiculturalism. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press; 1994. p. 35–73.

- Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. The self we live by: narrative identity in a postmodern world. Symbolic Interact. 2000;23:95–115.

- McAdams DP. Personal narratives and the life story. In: John O, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of personality: theory and research. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Guilford; 2008. p. 242–262.

- Frank AW. Letting stories breathe: a socio-narratology. Chicago (IL): University of Chicago Press; 2010.

- Giddens A. Modernity and self-identity: self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge (UK): Polity Press; 1991.

- Bamberg M. Who am I? Narration and its contribution to self and identity. Theory Psychol. 2011;21:3–24.

- Bruner J. Life as narrative. Soc Res. 1987;54:11–32.

- Musser B, Wilkinson J, Gilbert T, et al. Changes in identity after aphasic stroke: implications for primary care. Int J Fam Med. 2015;2015(1):1–8.

- Guerrero-Arias BE, Agudelo-Orozco A, Pava-Ripoll NA. Intersectional identity chronotopes: expanding the disability experience. Dis Soc. 2020;35:1660–1681.

- Norton B. Identity and language learning: gender, ethnicity and educational change. London: Longman Publishing Group; 2000.

- Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersections of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ Chicago Legal Forum. 1989;1:139–167.

- Simmons-Mackie N, Elman RJ. Negotiation of identity in group therapy for aphasia: the Aphasia Café. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2010;27(1):1–12.

- Pound C, Parr S, Lindsay J, et al. Beyond aphasia: therapies for living with communication disability. London: Routledge; 2000.

- Bronken BA, Kirkevold M, Martinsen R, et al. Psychosocial well-being in persons with aphasia participating in a nursing intervention after stroke. Nurs Res Pract. 2012;49(4):1–14.

- Polkinghorne DE. Narrative knowing and the human sciences. New York (NY): Suny Press; 1988.

- Zoffmann V. Guided self-determination. A life skills approach developed in difficult type, 1. diabetes. Aarhus: University of Aarhus; 2004.

- Bronken BA, Kirkevold M, Martinsen R, et al. The aphasic storyteller: coconstructing stories to promote psychosocial well-being after stroke. Qualitative Health Res. 2012;22:1303–1316.

- Ricoeur P. Time and narrative. Vol 1. Chicago (IL): University of Chicago Press; 1990.

- Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Soc Health Illn. 1982;4:167–182.

- Bauer JJ, McAdams DP, Pals JL. Narrative identity and eudaimonic well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2008;9(1):81–104. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9021-6.

- Strong KA, Lagerwey MD, Shadden BB. More than a story: my life came back to life. Am J Speech-Lang Pathol. 2018;27:464–476.

- Ricoeur P. Narrative identity. Philos Today. 1991;35(1):73–81. doi: 10.5840/philtoday199135136.

- Hinckley JJ. Finding messages in bottles: living successfully with stroke and aphasia. Top Stroke Rehabilit. 2006;13:25–36.

- Barrow R. Listening to the voice of living life with aphasia: Anne’s story. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2008;43:30–46.

- Somers MR. The narrative constitution of identity: a relational and network approach. Theory Soc. 1994;23:605–649.

- Corker M, French S. Disability discourse. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1999.

- Mitchell K, Skirton H, Monrouxe L. Amelioration, regeneration, acquiescent and discordant: an exploration of narrative types and metaphor use in people with aphasia. Disabil Soc. 2011;26:321–335.

- Armstrong E, Hersh D, Hayward C, et al. Living with aphasia: three Indigenous Australian stories. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2012;14(3):271–280. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2011.663790.

- Hinckley JJ. Narrative-based practice in speech-language pathology: stories of a clinical life. San Diego (CA): Plural Publishing; 2008.

- Willis SL, Martin M, Rocke C. Longitudinal perspectives on midlife development: stability and change. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7(3):131–134. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0162-4.

- Ruijters MPC, Van De Braak EEPM, Draijer HMA, et al. Je binnenste buiten. Over professionele identiteit in organisaties [Your inside out. On professional identity in organizations]. Zeist: Vakmedianet; 2015. Dutch.

- Guillemin M. Understanding illness: using drawings as a research method. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(2):272–289.

- Brinkman R, Cardol M, Neijenhuis K, et al. Wie ben ik nu? Een pilotonderzoek naar identiteitsveranderingen van Lot, een persoon met afasie. [Who am I now? A pilot study on identity changes of Lot, a person with aphasia]. Ned Tijd Logopedie. 2023;95(6):22–29. Dutch.

- Corker M. Deaf transitions: images and origins of deaf families, deaf communities, and deaf identities. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1996.

Appendix A

Table A1. Descriptive summary of the reports.

Table A2. Descriptive summary of theory of the reports.

Table A3. Overview of (sub-)themes of identity changes in aphasia.