Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this review was to explore what is currently known about Māori experiences of physical rehabilitation services in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Methods

A scoping review was undertaken following steps described by the Joanna Briggs Institute. Databases and grey literature were searched for qualitative studies that included descriptions of Māori consumer experiences in their encounters with physical rehabilitation. Data relating to study characteristics were synthesised. Qualitative data were extracted and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

Fourteen studies were included in this review. Four themes were generated that describe Māori experiences of rehabilitation. The first theme captures the expectations of receiving culturally unsafe care that become a reality for Māori during rehabilitation. The second theme describes whānau as crucial for navigating the culturally alien world of rehabilitation. The third theme offers solutions for the incorporation of culturally appropriate Māori practices. The final theme encompasses solutions for the provision of rehabilitation that empowers Māori.

Conclusions

This scoping review highlights ongoing inequities experienced by Māori when engaging with rehabilitation services. Strategies for facilitating culturally safe rehabilitation for Māori have been proposed. It is essential that rehabilitation clinicians and policymakers implement culturally safe approaches to rehabilitation with a view to eliminating inequities in care provision and outcomes for Māori.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Māori experiences of physical rehabilitation are comparable to the negative experiences they have in other health contexts.

Although there are pockets of optimism, the results of this scoping review indicate that the delivery of culturally safe rehabilitation is inconsistent in Aotearoa New Zealand.

A whānau-centred approach to rehabilitation is key to recovery and healing for Māori.

There are opportunities for clinicians to disrupt the culturally unsafe care experienced by Māori by facilitating rehabilitation that normalises Māori cultural practices and embeds Māori approaches to health and wellbeing.

Introduction

Globally, the pervasive heath inequities that exist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations have been deemed one of the most urgent humanitarian issues of the twenty first century [Citation1,Citation2]. Rehabilitation is a common component of care following musculoskeletal injury, illness and acquired disability [Citation3]. Indigenous populations have been found to suffer a heavier burden of musculoskeletal conditions and physical pain [Citation4]. There is however, no associated increase in uptake or access by Indigenous people to rehabilitation services that are designed to assist in achieving and maintaining optimal function and quality of life [Citation5,Citation6].

Māori are the Indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand. Māori rights to equitable healthcare are set out in article 24 of the United Nations Charter for Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which was ratified in Aotearoa New Zealand, and in the text of Te Tiriti o Waitangi (hereafter Te Tiriti). Te Tiriti is a treaty that was negotiated between the Crown of England and Māori leaders in 1840. The articles of Te Tiriti affirm Māori sovereignty over their own affairs and treasures, including health and health practices. Te Tiriti guaranteed Māori the same rights and privileges as British settlers and assured equity to Māori [Citation7]. Since its signing, there has been persistent disregard of the tenets of Te Tiriti in the ways healthcare is delivered in Aotearoa New Zealand [Citation8]. Disregard of Māori sovereignty in healthcare is equally true of rehabilitation as it is of primary healthcare and is evident in differential treatment and outcomes that Māori experience.

Similar to other Indigenous populations that have been colonised, Māori are more likely than non-Māori to sustain life-changing injuries and are less likely to access rehabilitation services [Citation9]. Māori experience higher rates of long-term disability and mental health issues following injury compared to non-Māori [Citation10,Citation11]. Māori often attempt to self-treat injuries before seeking healthcare or the help of a rehabilitation professional, leading to delayed presentations at acute settings and with more serious symptoms [Citation12,Citation13]. Māori are also less likely than non-Māori to be referred for surgical or specialist services [Citation14,Citation15]. To address these disparities, rehabilitation professionals in Aotearoa New Zealand have responsibilities to recognise and uphold the commitments of Te Tiriti and design services that are suitable for Māori.

Although injury and disability inequities are well reported, little is known about the experiences of Māori as consumers of physical rehabilitation services. Studies on Māori experiences of healthcare have largely focused on acute and primary care settings, and medical conditions. Previous studies highlight inequities in access to services and health outcomes and institutional racism [Citation14,Citation16]. A review specifically examining rehabilitation experiences is not known to have been undertaken. Rehabilitation has been recognised as an area with the potential to address Māori health needs because it shares concepts with Māori models of health. Both approaches recognise environmental and contextual factors, incorporate a holistic model, and implement both client- and family-centred care [Citation17,Citation18]. It is therefore essential to gain an understanding of Māori experiences of physical rehabilitation to inform equitable and culturally safe service provision. Culturally safe services attend to a multitude of factors that can impact on a healthcare encounter. Culturally safe clinicians thoughtfully consider the influence of culture; biases and assumptions; power relationships; and historical, institutional, and social constructs. It is important to remember that the cultural safety of a healthcare encounter must be defined by the recipient of care and not by healthcare providers [Citation19].

This scoping review, therefore, aimed to synthesise what is known about Māori experiences of physical rehabilitation services in Aotearoa New Zealand. Scoping reviews allow for a broad range of literature to be included for topics that have not yet been systematically reviewed [Citation20,Citation21]. Additionally, Māori research is a developing area, so it was important to ensure the search extended beyond academic databases, to find studies that could address the objectives of this review [Citation22,Citation23]. The findings from this review will inform a planned qualitative study exploring Māori experiences of rehabilitation in a hand therapy context. The qualitative protocol for this study has been published and includes considerations for the completion of culturally safe, cross-cultural research in Aotearoa New Zealand [Citation24]. An essential element of culturally safe research is to recognise the influence of researcher positionality on design decisions and data analysis [Citation25,Citation26]. Oversight for the culturally safety of this review lay with the second author (DW), who is Māori of Ngāti Kahungunu descent. The first author (BS) is an Irish immigrant to Aotearoa New Zealand and the third author (JC) is Pākehā (non-Māori New Zealander, usually of European descent).

Methods

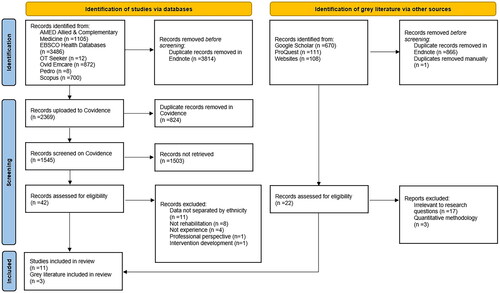

This scoping review was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) method [Citation23]. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist ensured comprehensive reporting of the review [Citation23,Citation27]. The search strategy was developed in consultation with an academic research librarian. The first author (BS) completed a literature search utilising the JBI three-stage iterative search strategy in conjunction with a population, concept, context framework (PCC) to determine eligibility criteria (see ). The first stage was a preliminary search for literature in two databases, using the PCC as search terms. Eligibility criteria and search terms were finalised following this preliminary search. The second stage involved a comprehensive literature search completed in February 2023 and again in January 2024. A full list of the databases and organisations searched for unpublished and grey literature can be found in supplementary file 1. The search strategy was adapted for each database and grey literature source. An example of a full search strategy completed for the Scopus database is provided in supplementary file 2. The third step was a search for additional literature in the reference lists from the studies selected for full review.

Table 1. Eligibility criteria.

Published studies were first exported to Endnote X9, with duplicates removed and titles screened for eligibility. Published studies were then uploaded to Covidence and checked again for duplication. Abstracts were screened in Covidence by the first author (BS). An additional step involved a search for the word Māori or ethnicity in the text body. A full text review of published studies that remained on Covidence after the abstract screen was completed by the first and second authors (BS and DW). Conflicts on study eligibility were resolved through consensus or by consultation with the third author (JC). Unpublished articles such as websites, large policy documents and theses, were examined separately by the first author (BS), due to incompatibility with Endnote and Covidence software.

Data analysis

Extraction of findings followed the JBI method and recommendations for thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden [Citation28]. Data relevant to Māori experiences of physical rehabilitation were extracted verbatim from the studies, for example from participant quotes, study discussions, tables, or supplementary materials. Extracted data excerpts were copied to a Microsoft Word table for analysis. Themes were formed using Braun and Clarke’s [Citation29] reflexive thematic analysis. This method was chosen because it allows for deep analysis of qualitative data. Additionally, reflexive thematic analysis has been used across a broad range of sources, including grey literature, and has been found to be work well alongside Thomas and Harden’s [Citation28] thematic synthesis [Citation30,Citation31]. Data familiarisation first occurred through full text review and multiple readings of the literature. Coding was conducted by the first author (BS). Codes were developed inductively; no a priori framework was applied. Both semantic and latent codes were applied across the data sets. Codes were transferred from the Microsoft Word table to an online visual whiteboard for grouping, comparison of codes and the formulation of themes. Generation of codes and themes involved an iterative, discussion-based process between all three authors. Points of analysis requiring a Māori lens were clarified with the second author (DW). Quotes were used to support the narrative of each theme.

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 14 studies were included in the review. The study selection process is depicted in . No additional studies were found through back-chaining of reference lists. An overview of the characteristics, purpose, and main findings of the studies from the peer-reviewed journals and grey literature searches are presented in and respectively. There were 11 studies from academic journals, two Master’s theses and one government study. Two articles [Citation32,Citation33] were descriptions of the same study with the findings from overall cohort and Māori participants published separately. Of the 14 studies, 8 solely explored Māori experiences. No study explicitly compared Māori to non-Māori experiences. The review includes the experiences of a total of 199 Māori, both individuals and their whānau (family). Most of the participants were adults with an age range of 19-94. Four studies included individuals under 18 years old. There was substantial variation in the rehabilitation contexts and diagnoses described in the studies. Programmes included hospital-based rehabilitation, outpatient and community rehabilitation, neurorehabilitation, and pulmonary rehabilitation. Participant diagnoses included neurological conditions, obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and non-specified musculoskeletal conditions. Rehabilitation was mostly facilitated by government-run organisations with one study comparing the experience of a hospital-based and an outpatient programme facilitated on a marae (Māori communal grounds). The studies differed in the parts of the rehabilitation process that were the focus of exploration. These components included personal factors, such as therapeutic relationships and caregiver experiences, as well as wider organisational factors and systemic barriers, such as access.

Table 2. Summary of characteristics and main findings sourced from peer-reviewed journals.

Table 3. Summary of study characteristics and main findings sourced from grey literature.

Themes

Four themes were generated to describe the experiences of Māori when engaging with rehabilitation services: Māori expectations of culturally unsafe healthcare become a reality during rehabilitation; Whānau are crucial for navigating cultural collisions during the rehabilitation journey; Rehabilitation is made culturally safe by embracing Te Ao Māori me ōna tikanga; Rehabilitation is made culturally safe through mana-enhancing services. Te Ao Māori me ōna tikanga refers to the Māori worldview and the protocols and practices encompassed within it. Mana is a concept from Te Ao Māori that describes a force that dwells within an individual akin to prestige, power, or status [Citation34,Citation35]. To enhance mana is to empower Māori and recognise Māori ways of doing things.

Theme one: Māori expectations of culturally unsafe healthcare become a reality during rehabilitation

This theme encompasses the preconceived ideas that influenced the expectations of Māori when entering the rehabilitation journey. Distrust towards the health system stemmed from past negative experiences not only in the health sector but with any government run organisation, such as the police. Before starting rehabilitation, participants had a sense of disconnection. Māori expected to feel isolated among Pākehā and for there to be a limited understanding of Māori concepts in health services. Many participants had their expectations of alienation confirmed by the negative experiences they had during rehabilitation. Engagement in rehabilitation for Māori was constrained by Te Ao Pākehā - referring to the Eurocentric configuration of health services in Aotearoa New Zealand. Participants found the services they received to be individualised and disease-driven with little flexibility or consideration for whānau wellbeing. Participants noticed a lack of Māori staff and encountered under-resourced Māori health services. Many described difficulties connecting with rehabilitation in any culturally meaningful way, resulting in some cases, to withdrawal from care.

…the services that he got were very westernised, there was a touch of Māori tradition but not a lot…his mum she very much does immerse herself in Māori culture… she stayed quite detached… If there was a bit more of a Māori element it would have created more of a connection with her… [Citation36, p. 54]

The participants described the culturally incompetent care of rehabilitation professionals and talked about staff making incorrect assumptions, being made to feel unworthy of treatment and being on the receiving end of discrimination. Māori described rehabilitation professionals’ communication style that was brief, cold, dismissive, and sterile. This way of communicating contradicted with Māori preferring to seek opportunities to create connections, a concept known as whakawhanaungatanga.

Another aspect of culturally unsafe care was clinician ignorance of the structural barriers that Māori faced and their impact on engagement with rehabilitation. Participants described the cumulative disadvantages that they experienced due to the combination of being Māori and having a physical disability. Such disadvantages included the intensification of negative societal perceptions and facing increased barriers to rehabilitation access. The lack of clinician understanding of wider systemic issues that Māori contend with was demonstrated in the following quote from a parent of one of the children engaging in a healthy lifestyle intervention for obesity:

And that’s what I said at the family group conference – ‘I disagree with that [comment made by a staff member in relation to child’s eating habits] because they were being fed. It might not be healthy to some people. But at least they were eating’ [Citation32, p. 673, Table 2]

Theme two: Whānau are crucial for navigating cultural collisions during the rehabilitation journey

This theme describes the essential roles that whānau hold during rehabilitation. For Māori, whānau includes both immediate and extended family groups. Whānau fought to ensure the best care for their loved one. There was a sense that the time whānau had available to support their loved one was reduced because of the additional roles they had to fulfil. At a time of high stress and vulnerability, whānau felt the additional pressure of having to help their loved one navigate a Te Ao Pākehā-driven system that clashed with Māori notions of health and wellbeing.

Whānau regularly acted as informal caregivers in the rehabilitation setting. The need for psychological, spiritual, and cultural support from whānau was emphasised frequently in the data. Participants felt issues such as cultural isolation and mental health were often inadequately addressed, therefore prolonging the healing process. In the absence of holistic support being provided by rehabilitation professionals, whānau stepped in to fulfil this need. This additional support served to keep their loved one engaged and motivated in rehabilitation, as depicted in the following quote.

Whānau…supported me to stay…so it was everybody talking to me really…so I wouldn’t rebuff against it, you know, keeping that engagement alive and trusting [Citation37, p. 1078]

Whānau were often required to be advocates during rehabilitation. Whānau wanted to ensure access to appropriate services and care. Participants reported issues in dealing with processes that were messy, not intuitive and involved dealing with multiple service providers simultaneously who gave contradictory information. Whānau with a better understanding of how the health system operates fought for services that should already have been in place. Whānau also worked to uphold tikanga (cultural practices) during rehabilitation. Where a lack of cultural awareness was displayed by clinicians, whānau promoted Māori perspectives and ways of doing things in support of their loved one.

Several of the studies discussed the cultural collisions between Te Ao Pākehā client-centred approach and Te Ao Māori collectivism. Whānau recognised the importance of being involved from the early stages of rehabilitation because once their loved one was discharged, they would be responsible for ongoing care. Participants often described instances where whānau were left out, despite repeatedly asking for them to be involved.

All the way through, any issue we’ve had has always been lack of consultation. So that we can be part of it. That’s all we’re asking. We’ll be there any time they want it but no, they had it somewhere else, and decisions made… I asked for the [meeting] to be around my bed with my husband present, but it didn’t happen [Citation38, p. 17]

The extra roles that whānau had in advocating for their loved one and providing additional care and holistic support appeared to go unrecognised. Because rehabilitation did not prioritise collective wellbeing of the whānau their needs were not addressed, and it tended to go unnoticed that the whānau group also required healing.

Theme three: Rehabilitation is made culturally safe by embracing Te Ao Māori me ōna tikanga

This theme encompasses solutions for cultural safety found in the data related to incorporating and enacting Māori ways of doing things during rehabilitation. Multiple interconnecting concepts from Te Ao Māori were described in their application to the rehabilitation space: manaakitanga (providing care and support), whakawhanaungatanga (creating connections), hononga (establishing bonds), kotahitanga (working together in unity), tikanga (cultural practices) and wairuatanga (processes that hold spiritual meaning). The importance of tikanga as a source for recovery was consistently emphasised by participants.

And it just that whanaungatanga (connecting with others) time is very important, how everyone feels…it’s kind of down to our level, and it’s good…bringing the tikanga aspect side of things, tikanga Māori…how we do things, who with, and in a place that we feel good in being [Citation39, p. 495]

Increasing access to and resources for Māori health services was suggested. Māori health services incorporated cultural approaches to healing and medicine to achieve wellbeing during rehabilitation. Increasing the Māori health workforce was also proposed. Māori clinicians had a positive impact during rehabilitation and were appreciated for their compassion and understanding. Participants reported that the approach and cultural familiarity of Māori staff put them at ease during rehabilitation and increased their feelings of connection.

Māori feel comfortable around Māori, I don’t think that’s a racial thing, it’s just they should know how Māori work [Citation40, p. 97]

The most strongly promoted solution relating to Te Ao Māori me ōna tikanga was the creation of culturally meaningful connections. Participants sought opportunities for whakawhanaungatanga during rehabilitation and valued time spent on developing connections with staff and services. Connections supported healing for Māori and facilitated increased participation and engagement in rehabilitation. When a positive connection was formed between participants and clinicians it led to a belief in the efficacy of rehabilitation and instilled confidence for the journey ahead. Participants felt comfortable and more relaxed with clinicians once a connection was established. Meaningful connections also helped to ease the impact of past unpleasant experiences and overcome negative preconceptions about rehabilitation and the wider health system.

Theme four: Rehabilitation is made culturally safe through mana-enhancing services

Themes three and four are inextricably linked. Clinicians could not embrace Te Ao Māori me ōna tikanga without working in a mana-enhancing way and vice versa. Services that enhanced mana were empowering, collaborative and whānau-centred. Participants requested that clinicians work as one with their whānau so that they would be included and recognised as integral members of the rehabilitation team. A collaborative communication style was described as one that was respectful, reciprocal, and open. The studies strongly recommended whānau inclusion at all stages of the rehabilitation journey, with appointed whānau decision makers being identified and consistent communication from staff.

Recognise whānau as a resource for recovery…they’re actually healing faster, [with] us as a whānau being here. We’re not getting in the way, we’re not a hindrance, we’re not here to be a burden…we’re here ‘cause it supports them [Citation41, p. 15]

Working collaboratively was advised so that rehabilitation could be made relevant for Māori. During initial assessments and whakawhanaungatanga, seeking information about meaningful daily activities, valued roles within the whānau and important environmental contexts served to connect participants with their rehabilitation. Participants felt that the barriers they faced, such as practical access issues, could be addressed when working collaboratively. It was recommended that clinicians actively seek information from Māori about the barriers they face as they are less likely to offer it spontaneously due to embarrassment and not wanting to be a nuisance. Incorporating meaningful activities as part of therapy and to achieve a goal was important for participants. Engaging in meaningful activities created a more relaxed and relevant interaction. Rehabilitation was enhanced when it took place in meaningful environments and cultural contexts.

It meant that they were listening. That’s that connection. It wasn’t just getting pulled out of the sky and saying ‘this is the best for you because this is what’s happened to you’…When you’re included in the solution and are able to participate in the solution, I think that’s a great thing [Citation37, p. 1078]

The included studies recommended ways in which clinicians could be culturally safe to provide mana-enhancing services. The studies encouraged rehabilitation professionals to be self-aware and self-reflective, particularly in relation to their culture and biases. Culturally safe clinicians were described as those who were conscious of the power relationship that inherently existed between themselves and Māori patients. Culturally safe clinicians actively incorporated and validated Te Ao Māori me ōna tikanga, as discussed in the previous theme. Several of the studies discussed the tendency to assume that health systems and the services they provide were culturally neutral. The studies advised that culturally safe clinicians recognise the historical impact of colonisation on the set up of the health system in Aotearoa New Zealand and the instilled institutional racism that accompanies this.

Discussion

This scoping review provides a thematic synthesis of the experiences described by Māori during their physical rehabilitation and proposes solutions that can assist in enhancing the cultural safety of rehabilitation for Māori. The results found that Māori expect to encounter and subsequently experience rehabilitation services that are culturally alien. We highlight that whānau are integral for Māori to navigate the nuances and complex processes of rehabilitation. The proposed solutions for cultural safety describe how rehabilitation professionals can enhance the mana of Māori consumers and embrace Māori approaches to health and wellbeing. Cultural safety has been recognised as a pathway for transformative change in the health system towards decolonisation and the eradication of health inequities [Citation42,Citation43]. Therefore, it is essential that physical rehabilitation services in Aotearoa New Zealand recognise and enact their responsibility to embed cultural safety throughout the rehabilitation journey.

The findings from this review challenge rehabilitation professionals to disrupt expectations that Māori have of culturally unsafe care. We suggest steps that can be taken to make meaningful change. One step towards culturally safe rehabilitation is to increase clinician awareness of what has caused intergenerational distrust of health services. These issues stem from colonisation and breaches of Te Tiriti that link to the poor outcomes and healthcare encounters that Māori experience [Citation8]. Clinicians who are cognisant of health inequities, as well as the historical and contemporary effects of colonisation, can prioritise the provision of culturally safe care. The demonstration of sensitivity to such matters in clinical interactions has the power to negate preconceptions and help to overcome past negative experiences [Citation39,Citation32].

Our review found that involving whānau made a critical difference for Māori during rehabilitation, leading to a raft of positive outcomes. Such benefits included increased participation and engagement and ensured the provision of culturally appropriate care. Autonomy and independence are taken for granted in rehabilitation contexts as a universally sought after goal [Citation44]. An essential step, therefore, towards countering individualistic rehabilitation models is to adopt a whānau-centred approach [Citation45]. Whānau-centred care enables whānau agency over the rehabilitation process and focuses on individual health within the whānau context, as well as the wellbeing of the whānau collective [Citation46,Citation47]. Rehabilitation services can address whānau needs through provision of accommodation, funding for kai and transport, and creating welcoming clinical spaces [Citation38,Citation45]. Delivery of home-based rehabilitation has also been suggested as a way of facilitating greater whānau inclusion [Citation48,Citation49].

Whakawhanaungatanga (creating connections) was the most frequently recommended solution from this review for the incorporation of tikanga (cultural practices) during rehabilitation. The concept of therapeutic rapport is well-known in rehabilitation. Whakawhanaungatanga extends beyond building rapport and simply introducing oneself, to a deeper connection that is vital for Māori [Citation46,Citation49]. Ways in which whakawhanaungatanga can be cultivated include correct name pronunciation, reciprocal sharing of personal information and finding connection through people and place [Citation39,Citation38]. Continuity of care and allowing time to form connections are aspects of whakawhanaungatanga that have been emphasised [Citation50,Citation51]. Because rehabilitation clinicians occupy intimate spaces in the lives of Māori patients when they are at their most vulnerable, it is essential that whakawhanaungatanga is prioritised [Citation42].

In terms of mana-enhancing services, it is important that when providing rehabilitation, clinicians recognise Māori diversity [Citation52]. Not all Māori share the same life experience or engage with Te Ao Māori me ōna tikanga in the same way. Understanding the influence of colonisation on migration and urbanisation of Māori can help clinicians to avoid typifying Māori as a singular group rather than as a culturally diverse group of people. Assumptions about Māori can be harmful and diminish mana [Citation19]. Flexibility of approach should be offered as part of rehabilitation, enabling choice and empowering Māori to be Māori as guided by them [Citation18]. Collaboration through shared decision-making and whānau-centred goal setting, approaches that align with rehabilitation best practice, would ensure the needs and preferences of Māori are known and met throughout rehabilitation [Citation53].

Participants from this study appreciated the familiarity and comfort of working with other Māori who could understand their perspective and cultural position, leading to a natural ease when forming connections. While this perspective is not new, our review draws attention to the pressing need to develop the Māori allied health rehabilitation workforce. Statistics show that Māori remain underrepresented across groups of allied health professionals compared to their proportion of the general population of Aotearoa New Zealand (17%). In 2020, 8% of occupational therapists and 7% of physiotherapists identified as Māori [Citation54]. Studies have shown the Māori allied health students and new graduates encounter racism and struggle with a lack of cultural support [Citation55,Citation56]. Pathways for Māori into allied health professions and the retention of clinicians once qualified are areas of workforce development that require close attention [Citation55,Citation57].

Increasing the Māori health workforce, however, does not absolve non-Māori clinicians from engaging with Te Ao Māori me ōna tikanga. Positive encounters with non-Māori clinicians who incorporated tikanga were described in the studies. Cultural safety training has the potential to address gaps in clinician knowledge related to culturally appropriate practice [Citation58,Citation59]. There has been an international surge in the implementation of cultural safety training over the last ten years [Citation60]. This too can be seen in the allied health competencies and rehabilitation policy of Aotearoa New Zealand [Citation9,Citation61,Citation62]. Evidence to support the efficacy of cultural safety training is lacking with evaluations tending to focus on learner experience alone [Citation60,Citation63]. Further research exploring the impact of cultural safety training from a service user perspective would be beneficial.

It is interesting to note that numerous studies excluded from this review reported to have Māori participants as part of their cohort. Such studies did not separate their results by ethnicity making it impossible to decipher Māori experiences from those of non-Māori. Māori experiences not being separated from the whole cohort indicates an almost tokenistic inclusion that lacks depth of analysis. While it is positive that Māori are actively being included in health research, our review indicates insufficient reporting of the outcomes and experiences that are unique to Māori.

Limitations

It has been noted that single-reviewer screening can limit the accuracy of literature searches [Citation64]. The screening process for this review was completed by a single reviewer and may have resulted in omission of eligible literature. Additionally, the definitions of health and rehabilitation used in the search strategy may have limited the studies available for inclusion. The World Health Organisation definition of rehabilitation emphasises the independence of individuals rather than collective wellbeing. The search for physical conditions in isolation contrasts with Māori holistic concepts of health and wellbeing, where physical health cannot be separated from emotional, spiritual and whānau wellbeing. Using these definitions in the search for literature may have resulted in only finding studies that define health in a similar, Eurocentric fashion. Future reviews may benefit from inclusion of search terms relating to holistic and collective wellbeing.

Conclusion

This review synthesised Māori experiences of physical rehabilitation in Aotearoa New Zealand. It is apparent that rehabilitation providers, as in other healthcare settings, are not consistently delivering culturally safe care for Māori. Rehabilitation services are challenged to create a safe space for Māori and deliver whānau-centred care. In this way Māori and their whānau can focus their energy on healing and recovery without having to navigate cultural collisions throughout the rehabilitation journey.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (240.2 KB)Disclosure statement

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jones R, Crowshoe L, Reid P, et al. Educating for Indigenous health equity: an international consensus statement. Acad Med. 2019;94(4):512–519. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002476.

- Nelson V, Derrett S, Wyeth E. Indigenous perspectives on concepts and determinants of flourishing in a health and well-being context: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e045893. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045893.

- World Health Organisation. Rehabilitation. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation.

- Lin I, Coffin J, Bullen J, et al. Opportunities and challenges for physical rehabilitation with Indigenous populations. Pain Rep. 2020;5(5):e838. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000838.

- CARF International. Medical Rehabilitation. 2023. Available from: https://carf.org/accreditation/programs/medical-rehabilitation/.

- Escorpizo R. Defining the principles of musculoskeletal disability and rehabilitation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(3):367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.09.001.

- Came HA, McCreanor T, Doole C, et al. Realising the rhetoric: refreshing public health providers’ efforts to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi in New Zealand. Ethn Health. 2017;22(2):105–118. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2016.1196651.

- Wilson D, Haretuku R. Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi 1840: its influence on health practice. In Wepa D, editors. Cultural safety in Aotearoa New Zealand. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2015. p. 79–99.

- ACC. Kawa Whakaruruhau Policy. 2023. https://www.acc.co.nz/assets/provider/cultural-safety-policy.pdf.

- Nelson V, Lambert M, Richard L, et al. Examining the barriers and facilitators for Māori accessing injury and rehabilitation services: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e048252. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048252.

- Wyeth EH, Samaranayaka A, Lambert M, et al. Understanding longer-term disability oucomes for Māori and non-Māori after hospitalisation for injury: results from a longitudinal cohort study. Public Health. 2019;176:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.08.014.

- Jeffreys M, Lopez MI, Russell L, et al. Equity in acess to zero-fees and low cost primary health care in Aotearoa New Zealand: results from repeated waves of the New Zealand health survey, 1996-2016. Health Policy. 2020;124(11):1272–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.hralyhpol.2020.08.009.

- Wren J. Barriers to Maori utilisation of ACC funded services, and evidence for effective intervention: Maori responsiveness report 2. Wellington: ACC Research; 2015.

- Health Quality & Safety Commission New Zealand. He Matapihi Ki Te Kounga o Ngā Manaakitanga Ā-Hauora O Aotearoa 2019. A Window on the Quality of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Health Care 2019. 2019. Available from: https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Window_2019_web_final.pdf.

- Zambas SI, Wright J. Impact of colonialism on Māori and Aboriginal healthcare access: a discussion paper. Contemp Nurse. 2016;52(4):398–409. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2016.1195238.

- Palmer SC, Gray H, Huria T, et al. Reported Māori consumer experiences of health systems and programs in qualitative research: a systematic review with meta-synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):163. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-1057-4.

- Harwood M. Rehabilitation and Indigenous peoples: the Māori experience. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(12):972–977. doi: 10.3109/09638281003775378.

- Hopkirk J, Wilson LH. A call to wellness - Whitiwhitia i te ora: exploring Māori and occupational therapy perspectives on health. Occup Ther Int. 2014;21(4):156–165. doi: 10.1002/oti.1373.

- Wepa D. Cultural Safety in Aotearoa New Zealand. 2nd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

- Jesus TS, Papadimitriou C, Bright FA, et al. Person-centered rehabilitation model: framing the concept and practice of person-centered adult physical rehabilitation based on a scoping review and thematic analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103(1):106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.05.005.

- Munn Z, Peters M, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- Barrett NM, Morgan R, Tamatea J, Jones A., et al. Creating an environment to inform, build and sustain a Māori health research workforce. J R Soc New Zealand. 2023:1–15. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2023.2235303.

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: A E, Z. Munn, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687342/Chapter+11%3A+Scoping+reviews.

- Sheehy B, Collis J, Wepa D. Te Tiriti informed approach: a korowai of cultural safety for research. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2024;71(1):33–39.

- Patterson EW, Ball K, Corkish J, et al. Enhancement of rigour in qualitative approaches to inquiry: a systematic review of evidence. QRJ. 2023;23(2):164–180. doi: 10.1108/QRJ-06-2022-0086.

- Terry G, Hayfield N. Essentials of thematic analysis. Washington, USA: American Psychological Association; 2021.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative reserach in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

- Braun V, Clarke C. Thematic analysis. A practical guide. London, UK: SAGE; 2022.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns Psychother Res. 2021;21(1):37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360.

- Rosin M, Mackay S, Gerritsen S, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of healthy food and drink policies in public sector workplaces: a systematic literature review. Nutr Rev. 2023;82(4):503–535. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuad062.

- Wild CEK, Rawiri NT, Willing EJ, et al. What affects programme engagement for Māori families? A qualitative study of a family-based, multidisciplinary healthy lifestyle programme for children and adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021;57(5):670–676. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15309.

- Wild CE, Rawiri NT, Willing EJ, et al. Determining barriers and facilitators to engagement for families in a family-based, multicomponent healthy lifestyles intervention for children and adolescents: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):e037152. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037152.

- Moorfield JC. ; 2024. Te Aka Māori Dictionary. Available from: https://www.maoridictionary.co.nz/.

- Wilson D, Moloney E, Parr JM, et al. Creating an Indigenous Māori-centred model of relational health: a literature review of Māori models of health. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(23-24):3539–3555. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15859.

- Silveira ML. Mai ngā pouwhirinaki - The experiences of whānau caring for Māori tangata whaiora with traumatic brain injury in the Waikato [Master’s of Science thesis, University of Waikato]. Research Commons. 2022. Available from: https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/15221.

- Bishop M, Kayes N, McPherson K. Understanding the therapeutic alliance in stroke rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(8):1074–1083. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1651909.

- Pihema S. Whānau Māori wheako ki te tauwhiro pāmamae me te whakaoranga. Whānau Māori experiences of major trauma care and rehabilitation Health Quality & Safety Commission Report; 2022. Available from: https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/Our-work/National-trauma-network/Publications-resources/Exec-summary-Maori-experience-trauma-rehab-report-final-April2022.pdf.

- Levack WM, Jones B, Grainger B, et al. Whakawhanaungatanga: the importance of culturally meaningful connections to improve the uptake of pulmonary rehabilitation by Maori with COPD - a qualitative study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11(1):489–501. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S97665.

- Fernandez FS. Understanding the experiences of whānau caregivers of stroke survivors [Master of Osteopathy, Unitec Institute of Technology]. Research Bank. 2020. Available from: https://www.researchbank.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10652/5062/MOst_2020_Favsta%20Fernandez%20%2b.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Wilson B-J, Bright FA, Cummins C, et al. ‘The wairua first brings you together’: Māori experiences of meaningful connection in neurorehabilitation. Brain Impairment. 2022;23(1):9–23. doi: 10.1017/BrImp.2021.29.

- Came H, Kidd J, Heke D, et al. Te Tiriti o Waitangi compliance in regulated health practitioner competency documents in Aotearoa. N Z Med J. 2021;134(1535):35–43.

- Hunter K, Roberts J, Foster M, et al. Dr Irihapeti Ramsden’s powerful petition for cultural safety: kawa whakaruruhau. Nursing Praxis. 2021;37(1):25–28. doi: 10.36951/27034542.2021.007.

- Carpenter C, Suto M. Qualitative research for occupational and physical therapists. A practical guide. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2008.

- Wepa D, Wilson D. Struggling to be involved: an interprofessional approach to examine Māori whānau engagement with healthcare services. J Nur Res Prac. 2019;3(3):1–5.

- Komene E, Pene B, Gerard D, et al. Whakawhanaungatanga—Building trust and connections: a qualitative study Indigenous Māori patients and whānau (extended family network) hospital experiences. J Adv Nurs. 2023;80(4):1545–1558. doi: 10.1111/jan.15912.

- Te Puni Kōkiri. Understanding whānau-centred approaches. Analysis of phase one whānau ora research and monitoring results. 2015. Available from: https://www.tpk.govt.nz/en/o-matou-mohiotanga/whanau-ora/understanding-whanaucentred-approaches-analysis-of.

- Cate L, Giles N, Van der Werf B. Equity of Māori access to the orthopaedic rehabilitation service of the Bay of Plenty: a cross-sectional survey. NZMJ. 2023;136(1581):44–50. doi: 10.26635/6965.6012.

- Pene B, Clark TC, Gott M, et al. Conceptualising relational care from an Indigenous Māori perspective: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(19-20):6879–6893. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16794.

- Carlson T, Moewaka Barnes H, Reid S, et al. Whanaungatanga: a space to be ourselves. J Indig Wellb. 2016;1(2):44–59.

- Masters Awatere B, Cormack D, Graham R, et al. Whānau experiences of supporting a hospitalised family member away from their home base. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 2024;19(1):86-104. doi: 10.1080/1177083X.2023.2227234.

- Durie M. Ngā matatini Māori = Diverse Māori realities: a paper/prepared by M.H. Durie. 1995.

- Baker A, Cornwell P, Gustafsson L, et al. Implementation of best practice goal-setting in five rehabilitation services: a mixed-methods evaluation study. J Rehabil Med. 2023;55(4471):jrm4471. doi: 10.2340/jrm.v55.4471.

- Te Rau Ora. Māori health and social care (HSC) workforce: 20 year trends. Infometrics. 2022. Available from: https://terauora.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/1.-MAORI-HEALTH-AND-SOCIAL-CARE-20-YR-TRENDS-SERIES.pdf.

- Davis G, Came H. A pūrākau analysis of institutional barriers facing Māori occupational therapy students. Aust Occup Ther J. 2022;69(4):414–423. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12800.

- Tofi VUF. Thriving as Māori & Pasifika allied health professionals in the first 2 years of practice in a DHB setting [Master of Health Practice, Auckland University of Technology]. Res Commons. 2021. Available from: https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/ee5caafe-72ad-44e9-a58f-154945b8409e/content

- Wikaire E, Ratima M. Māori participation in the physiotherapy workforce. Pimatisiwin J. Aborig. Indig. Commun. Health. 2011;9(2):473–495.

- Hunter K. Cultural safety or cultural appropriation? Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand. 2020;26(1):24–25.

- Kurtz DLM, Janke R, Vinek J, et al. Health sciences cultural safety education in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: a literature review. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:271–285. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5bc7.21e2.

- MacLean TL, Qiang JR, Henderson L, et al. Indigenous cultural safety training for applied health, social work and educational professionals: a PRISMA scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(6):5217. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20065217.

- Occupational Therapy Board of New Zealand. Competencies for Registration and Continuing Practice for Occupational Therapists. 2022. Available from: https://otboard.org.nz/document/5886/7569%20OTBNZ%20-%20Competencies%20for%20practice%20FINAL%20G.pdf.

- Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand. Physiotherapy Standards. 2018. Available from: https://pnz.org.nz/Folder?Action=View%20File&Folder_id=1&File=Physiotherapy%20Standards%202018.pdf.

- Hardy B, Filipenko S, Smylie D, et al. Systematic review of Indigenous cultural safety training interventions for healthcare professionals in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States. BMJ Open. 2023;13(10):e073320. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073320.

- Gartlehner G, Affengruber L, Titscher V, et al. Single-reviewer abstract screening missed 13 percent of relevant studies: a crowd-based, randomized controlled trial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;121:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.01.005.

- Boland P, Jones B, Stanley J, et al. Using a maori model of health to analyse the use of equipment by New Zealand Maori post-stroke. New Zealand J Occupat Therapy. 2020;67(2):19–26.

- Bourke JA, Owen HE, Derrett S, et al. Disrupted mana and systemic abdication: Māori qualitative experiences accessing healthcare in the 12 years post-injury. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09124-0.

- Derrett S, Langley J, Hokowhitu B, et al. Prospective outcomes of injury study. Inj Prev. 2009;15(5):e3–351. doi: 10.1136/ip.2009.022558a.

- Graham F, Boland P, Jones B, et al. Stakeholder perspectives of the sociotechnical requirements of a telehealth wheelchair assessment service in Aotearoa/New Zealand: a qualitative analysis. Aus Occup Therapy J. 2022;69(3):279–289. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09299-6.

- Harwood M, Ranta A, Thompson S, et al. Barriers to optimal stroke service care and solutions: a qualitative study engaging people with stroke and their whānau. N Z Med J. 2022;135(1556):81–93.

- Lambert M, Wyeth EH, Brausch S, et al. "I couldn’t even do normal chores": a qualitative study of the impacts of injury for Māori. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(17):2424–2430. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1701102.

- Perry M, Hudson S, Clode N, et al. What factors affect attendance at musculoskeletal physiotherapy outpatient services for patients from a high deprivation area in New Zealand? NZJP. 2015;43(2):47–53. doi: 10.15619/NZJP/43.2.04.