Abstract

Purpose

To gain a rich understanding of the experiences and opinions of patients, healthcare professionals, and policymakers regarding the design of OGR with structure, process, environment, and outcome components.

Methods

Qualitative research based on the constructive grounded theory approach is performed. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with patients who received OGR (n = 13), two focus groups with healthcare professionals (n = 13), and one focus group with policymakers (n = 4). The Post-acute Care Rehabilitation quality framework was used as a theoretical background in all research steps.

Results

The data analysis of all perspectives resulted in seven themes: the outcome of OGR focuses on the patient’s independence and regaining control over their functioning at home. Essential process elements are a patient-oriented network, a well-coordinated dedicated team at home, and blended eHealth applications. Additionally, closer cooperation in integrated care and refinement regarding financial, time-management, and technological challenges is needed with implementation into a permanent structure. All steps should be influenced by the stimulating aspect of the physical and social rehabilitation environment.

Conclusion

The three perspectives generally complement each other to regain patients’ quality of life and autonomy. This study demonstrates an overview of the building blocks that can be used in developing and designing an OGR trajectory.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

There’s a growing preference for providing geriatric rehabilitation in an outpatient setting at the patients’ home (called outpatient geriatric rehabilitation), but little is known about the content, efficiency, and quality assurance of outpatient geriatric rehabilitation.

The key elements for the outpatient geriatric rehabilitation framework consist of a specialized geriatric rehabilitation dedicated multidisciplinary team, patient-centered blended eHealth applications, collaboration with integrated care, especially in community care nursing, and physical and social rehabilitation environments.

The outpatient geriatric rehabilitation design framework, which emerged from the thematic analysis, offers valuable insights, and can support healthcare professionals and policymakers to establish an effective rehabilitation pathway.

Introduction

How are we going to make geriatric rehabilitation (GR) future-proof? The demand for GR will increase. An important driver of this is the aging of society and the associated loss of physical function. Acute and subacute functional decline as a result of hospitalization, exacerbations of chronic conditions, and injuries and falls will also increase [Citation1,Citation2]. At present, there is a growing shortage of healthcare professionals, leading to a limited capacity for inpatient GR (IGR) [Citation3–5]. Driven by these expectations and the knowledge that older adults experience a need for rehabilitation support at home after IGR [Citation6] and wish to stay at home for longer [Citation7], the tendency is to deliver GR at home with a specialized multidisciplinary team led by an elderly care physician. This is called ambulatory or outpatient geriatric rehabilitation (OGR) [Citation8,Citation9].

Since 2014, the Netherlands has introduced Geriatric Rehabilitation (GR) into its healthcare system, shifting reimbursement from a long-term care government-guided system to a market-guided payment system [Citation10]. This change has led to the professionalization of GR, involving the design of various care pathways [Citation11] and a focus on the rehabilitation climate [Citation12]. More recent developments have concentrated on the OGR trajectory [Citation13], driven by the added value demonstrated in several studies that show positive outcomes associated with rehabilitation at home, for example, on functional outcomes, self-employment, risk of falling, caregiver burden, and cost-effectiveness [Citation11,Citation12,Citation14–16]. Ramsey et al. [Citation17] demonstrated that patients at home spent 2.5 less time lying down than those undergoing inpatient care. Furthermore, a recent systematic review [Citation18] shows that OGR is as effective as usual care and possibly cost-effective. This review also highlighted several frequently used structure, process, and environment elements that may influence the outcomes of OGR.

Despite the professionalization within GR in the Netherlands and the evidenced positive outcomes of OGR, little is known about the perspectives of patients, healthcare professionals, and policymakers on the components that are needed in designing OGR. Examples of these could be the contents of OGR and inclusion criteria for receiving OGR instead of IGR [Citation8,Citation19]. Moreover, many barriers and facilitators exist. For example, external factors, such as financial and practical feasibility might play a role in how traveling, time management, and costs become barriers to providing rehabilitation at home [Citation14,Citation20]. Several studies have stated that more research is needed to finalize the contents, efficiency, and quality assurance of OGR for patients, healthcare professionals, and policymakers [Citation15,Citation21,Citation22].

Therefore, this study aims to gain a better understanding of the experiences and opinions of patients, healthcare professionals, and policymakers regarding the design of OGR on components related to the structure, process, environment, and outcome.

Research design and methods

Design and theoretical background

A qualitative research approach, which consisted of interviews and focus groups based on the constructive grounded theory approach according to Charmaz [Citation23,Citation24] was used to evaluate experiences and opinions regarding the design of OGR in (1) older adults who have been admitted to an OGR setting (patients), (2) healthcare professionals involved with OGR (professionals), and (3) members of the board of directors responsible for the policies associated with (O)GR within a healthcare organization (policymakers).

The Post-acute Care Rehabilitation (PAC-Rehab) quality framework by Jesus et al. [Citation25] was applied as a theoretical background. This model distinguishes four components of a patient-centered approach, namely that the processes (patient care and interprofessional) and immediate outcomes (ICF) have an iterative and integrative connection which is influenced by the structure (organizational requirements), and environmental (patient and systematic) context. All of the elements are related to the rehabilitation’s end goals (macro-outcomes), such as functional performance, patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life, consumer experience, and healthcare utilization [Citation25].

Setting

All participants were approached between March and October 2022 through the four organizations affiliated with the GR “Development Practice.” The Development Practice is a collaboration between The University Network for Elderly Care Amsterdam University Medical Center location VUmc and four Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) focused on GR in the Netherlands.

The GR trajectory in the Netherlands involves several steps based on internationally agreed-upon basic elements [Citation10,Citation19,Citation26]. It begins with hospital admission after an acute event, followed by transfer to a GR ward in a skilled nursing facility if the patient is medically stable. A specialized multidisciplinary team led by an elderly care physician focuses on rehabilitation, aiming to achieve independence in daily activities. Rehabilitation may continue through OGR with the specialized clinical team and community care nursing involvement. The elderly care physician leads the outpatient rehabilitation process, while the general practitioner handles other medical issues.

Recruitment and data collection

During the multidisciplinary discharge meeting, patient eligibility for the study was determined. A member of the multidisciplinary team provided an information letter and discussed the study with the eligible patients. If interested, the professional notified the researcher (AP). The researcher followed up with the patient within a week to give oral and written information. If the patient agreed to participate, written informed consent was obtained before inclusion.

Professionals and policymakers were recruited by e-mail via internal contacts within the organization. We adopted a purposive sampling strategy [Citation23,Citation24]. Written informed consent was obtained before inclusion.

Patients

We included patients who were able to communicate, were legally competent (assessed by a physician), and had recently completed the OGR trajectory after being admitted to a skilled nursing facility. The interviews were scheduled to occur within four weeks after finishing the OGR trajectory to minimize the risk of recall bias. We aimed to recruit participants with a wide variety of OGR trajectories (e.g., stroke, hip fracture, and chronic conditions). The interviewer (AP) conducted face-to-face semi-structured interviews (n = 13), using a pilot-tested interview guide (Supplementary Material 1) [Citation27]. The interviews took place at the patient’s home, where occasionally a caregiver was present (n = 5). The purpose of this interview was to understand a patient’s GR trajectory and experiences at home.

Professionals and policymakers

Two focus groups were held with professionals that contained five to eight respondents. Respondents were selected based on whether they worked in one of the four organizations involved and had experience with OGR. We included a variety of professionals, such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, elderly care physicians, (IGR/community care) nurses, and psychologists. We also held one focus group that included four policymakers from each of the four organizations involved who were familiar with the content and organization of OGR.

To facilitate attendance, we arranged a hybrid setting (a combination of an in-person meeting and online) for the professionals and online video conferencing using Microsoft Teams [Citation28] for the policymakers. A topic guide was used with questions, prompts, and exercises to encourage a focused and rich discussion (Supplementary Materials Citation2 and Citation3). The focus groups were moderated by two facilitators each with a clearly defined role: a discussion leader (AP) and an observer responsible for timekeeping, maintaining structure, and taking notes (MH/MP). This setup ensured that all predetermined topics were thoroughly discussed and explored, and besides identified unexpected, yet relevant, themes [Citation24,Citation29]. To increase the credibility of the study results, we performed a member check by emailing the summary of the focus group results to the participants for verification, with the opportunity to give additions and feedback [Citation24,Citation29]. To improve the study’s thoroughness, we made field notes during and immediately after the interviews and focus groups. These notes contain our observations (who, where, what, when) and critical reflective notes, which will contribute to the empirical evidence in the analysis [Citation24,Citation29].

The interviews (duration = 60 m) and focus groups (duration = 90 m) were recorded on tape and transcribed verbatim. The research data was stored in a safe place in a secure folder within Amsterdam UMC, along with any personal data. Any names of individuals and institutions are pseudonymized in the transcripts. Data collection and data analysis was an iterative process, which continued until saturation occurred.

Data analysis

The data analysis for the three groups was executed by AP and AL based on constructive grounded theory [Citation23]. We applied open coding techniques during two consecutive phases. First, a line-by-line analysis of the manuscripts was conducted (initial coding) with constant comparison between the data of each interview and between the interviews. Second, the focused selective coding phase took place in which we merged the most useful initial codes into categories. These categories were distributed across subthemes. The analysis per perspective is presented sequentially in Supplementary Materials Citation4–6. Subsequently, we conducted an in-depth analysis to assess the similarities and differences between the three perspectives, based on the PAC-Rehab quality framework [Citation25], which resulted in overarching themes. Whenever there were dissimilarities during the data analysis process, discussion with the research team resolved this. MAXQDA version 2020 was used for the analysis process. We used the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) as a reporting guideline [Citation30].

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Amsterdam in The Netherlands (protocol ID 2021.0786).

Results

and show the characteristics of the participating patients (n = 13), professionals (n = 13), and policymakers (n = 4).

Table 1. Participant characteristics; interview patients.

Table 2. Participant characteristics; focus groups healthcare professionals and organizational perspective.

In-depth analysis of three perspectives

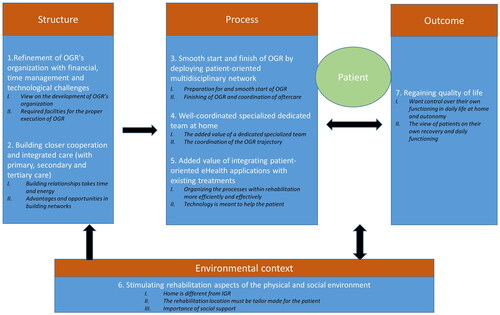

The in-depth and integrated analysis resulted in overarching themes that concerned the experiences and opinions of all three groups regarding the design of OGR. In some instances during the analysis, the field notes proved valuable in interpreting the results. presents the resulting overarching themes which are subdivided into the components of structure, process, environmental context, and outcome [Citation25].

Figure 1. The overarching themes from the in-depth analysis of the patient, healthcare professional and organisation perspectives based on the PAC-rehab quality framework.

Outcome

The outcome component relates to the goals of OGR [Citation19], with an emphasis on “Regaining quality of life.” Patients “want control over their functioning in daily life at home, and autonomy.” They are generally satisfied with the outcomes of OGR. Professionals strive for autonomy and independence for the patients. They see that patients often desire to be back at home. Moreover, they observe that patients experience loneliness, that they must learn to deal with a new situation, and do not like to organize everything themselves due to reduced self-confidence or fatigue. This is also experienced by many patients. In particular, the transition back home is often experienced as strange and tiring. Once at home, almost all of the patients became aware of the advantages as they now could be in charge of their daily schedule and take control of their lives:

“The idea that you still matter because you do your things. You can do anything you want, go into town with your girlfriends, I decide." (Patient 6)

“I tried by myself for as long as I could until my self-esteem came back. So that I could shower myself, and that I decide for myself, that I’m not tied to someone else.” (Patient 1)

“The view of the patients on their own recovery and daily functioning” is divided into two groups. The first group is patients who experience independence in their daily functioning and indicate that they can do a lot by themselves, such as daily activities and making day trips. This has a positive impact on their quality of life and is similarly reflected in confidence surrounding their recovery and satisfaction concerning their progress. The second group, which was the majority of patients, experienced obstacles in their daily functioning, such as walking (outside) and a fear of falling. This resulted in a negative attitude toward recovery and feelings of frustration and doubt about the future:

“You think, like, damn, you can manage, there is no way you can’t do it by yourself and then you get mad at yourself.” (Patient 4)

Process

To regain a better quality of life for the patient, several patient care and interprofessional process elements are essential. A “Smooth start and finish of OGR by deploying a patient-oriented multidisciplinary network” is essential. All three groups discussed the “preparation for and smooth start of OGR.” The policymakers indicated that triage before OGR is important to determine the division of tasks. During this stage, further admission options for OGR are explored:

“So, the outpatient rehabilitation does not necessarily have to start from a clinical admission but can also start directly from home or hospital.” (Policymaker 3)

“Yes, there’s no place like home. But now and then, I think, like, those 14 days would have been nice, but you won’t find out until you get home” (Patient 1)

“Finishing of OGR and coordination of aftercare” is organized differently in the participating care organizations. Professionals indicated that arranging a meeting at the end of OGR with the entire multidisciplinary team and the patient is desirable. In addition, professionals emphasized wanting to be able to follow the patient and guide them with a specialized team for longer to increase the effect of rehabilitation:

“I would like to keep someone within the organization to, like, say, prevent readmission…that you always have the same therapists throughout the process so that you no longer have crises either." (Professional 10)

Besides a smooth start and finish of OGR, a “well-coordinated, specialized dedicated team at home” is a second main theme. Both policymakers and professionals highlighted “the added value of a dedicated, specialized team” in which the clinical professionals follow the patient home. Patients also indicated that they preferred to be treated by the same professional at home as they had in IGR. They expressed a lot of confidence in the professionals and often left choices about the content and interpretation of rehabilitation to the therapists:

“I liked everything they did. I said yes to everything, that’s good. Being agreeable achieves more than opposing, at least that’s how I see it.” (Patient 13)

“…that we just have better communication, like, well, what did they manage at home and what should they be able to do to be allowed to return home.” (Professional 1)

“Coordination of the OGR trajectory” needs attention according to both the policymakers and professionals. Some professionals experienced a loss of control and oversight during OGR. All three groups indicated that a central guide for the patient, for example, distributed by a case manager, is important for keeping an overview during (O)GR:

“And we must not forget the client … who no longer understands anything about the situation anymore and is just aware that they now have an occupational therapist or a physiotherapist or a social worker. So that guide for the client is extremely important in that sense. Because a lot of this is about vulnerable older people.” (Policymaker 4)

The third essential process theme is “The added value of integrating patient-oriented eHealth applications with existing treatment.” Both professionals and policymakers believed that eHealth applications can make a positive contribution to “organizing the processes within rehabilitation more efficiently and effectively.” Earlier integration into (O)GR and interaction with existing treatments are desirable features:

“I wouldn’t have it be completely digital, but I do think it could be a nice addition, even if it’s only to make a video call about, like, how you’re doing. Sometimes you don’t have to travel all the way there and you can just briefly give some advice or…videos explaining your exercises that people can also do by themselves…" (Professional 2)

An automatic medication dispenser or assistive robot are things you would want to deploy clinically. You could integrate it much earlier in your pathway. (Policymaker 1)

Moreover, policymakers emphasized that “technology is meant to help the patient.” Technology can enable greater control for the patients over their care trajectory and encourage self-management. Policymakers also believed that a shift is needed to support the notion that technology is for the patient and not for the professional. In this way, the development of blended care pathways is needed:

Convert the rehabilitation trajectories or recovery trajectories to digital tools and really give control to the patient. Because right now, we still often see that the professionals are in control and determine what steps the patient goes through. And if we don’t change that, it’s almost impossible to succeed during rehabilitation at home. And if we can say here is your tablet, it says precisely what steps you must go through for the best possible rehabilitation or recovery. I think the patient will be more in control. The technology helps with that exceptionally well. (Policymaker 4)

Structure

The organizational requirements within the structure component will additionally influence the process elements and the outcomes of OGR. The first theme identified that “Refinement of OGR’s organization is needed with financial, time-management and technological challenges.” all three groups have a “view on the development of OGR’s organization.” Patients discussed how satisfied they are with the structure of OGR as it is now, noting that they had good experiences. However, they do provide further suggestions, such as wanting to be called by a team member a few days after discharge and having more therapy at home. The professionals and policymakers see the need and added value of OGR and support further development. The policymakers advised taking into account shortages in the labor market when developing OGR:

“Linking up with current infrastructure is really important to me. Especially given the scarcity we are experiencing in the labor market now and perhaps also financially in the future.” (Policymaker 4)

“Yes, more attention is paid to the hours than to the people.” (Professional 6)

“No matter how good the physiotherapist is, my options are very limited here, but in the building, there is a leg press for your legs and weights." (Patient 3)

As well as refinement of OGR’s organization “Building closer cooperation and integrated care (with primary, secondary, and tertiary care)” is a main theme on the structure level. Integrated care is an essential topic for policymakers. They highlighted that “building relationships takes time and energy.” For cooperation with general rehabilitation specialists and hospitals to be effective, gaining trust is key. This is especially the case concerning triage. Further, policymakers noted that cooperation in the social domain falls short and that timely collaboration could improve discharge possibilities (for example, due to completed adjustments to housing) and prevent readmissions:

“There is also quite a lot to organize when someone is going home and has few informal caregivers or no support structure around them. However, we do not know enough about this, and I have found that it also takes a lot of time and energy to build and maintain relationships.” (Policymaker 1)

Environment

The structure, process, and outcome components are all influenced by “Stimulating rehabilitation aspects of the physical and social environment.” At the start of OGR, both patients and professionals feel that rehabilitating at “home is different from IGR,” yet they do recognize the advantage:

“That they learn it the correct way right from the start because if we ask where they always hang the towel, they can’t tell you that at that moment.” (Professional 1)

All three groups indicated that “the rehabilitation location must be tailor-made for the patient.” Policymakers see the advantages of therapy at home. However, they advise providing therapy on location as soon as the patient is ready, partly because of the possibilities for group treatment. Patients who preferred therapy on the location indicated reasons, such as the presence of training equipment, advice from the therapist, and their own choice. In contrast, patients who preferred therapy at home cited reasons, such as fatigue, transport problems, not wanting to leave the house, and the practicality:

“There’s more at home, and you come across more things that are difficult and you haven’t thought about.” (Patient 7)

“That you can be partly at home in your environment, but in an exercise room you have other things that you can practice at a different level, which can make it challenging again, so to speak.” (Professional 4)

“…that there is a clear social map, with volunteers and buddies. I believe that social vulnerability in particular is an issue where we as therapists have our backs against the wall. It would be nice if you had shorter lines of communication with the regional organization there.” (Professional 13)

“If it has to come from yourself, you’ll do it, but it’s more non-committal.” (Patient 3)

Discussion

This qualitative study presents a better understanding of how to design OGR from the perspective of the patient, healthcare professional, and organization. An in-depth analysis of all three perspectives identified seven main themes. The findings suggest that the outcome of OGR is focused on regaining patients’ quality of life and autonomy. Essential process elements to attain this are a patient-oriented multidisciplinary network, a well-coordinated multidisciplinary dedicated team at home, and patient-oriented blended eHealth applications. Additionally, refinement of the organization of OGR and incorporating closer links with integrated care is needed at the structure level. The stimulating aspects of the physical and social rehabilitation environment influence all of these steps.

This present study has explored several important elements that are associated with the organization and content of OGR, which corroborates previous findings [Citation18], such as a case manager, a dedicated specialized team that provides inpatient and outpatient GR, integration of patient-oriented technology, caregiver involvement, and integrated care [Citation9,Citation10,Citation20,Citation31]. This knowledge about the potentially valuable elements for the OGR trajectory could be applied in the design of OGR. Overall, the three groups exhibited similarities in their experiences and wishes concerning OGR and complemented each other in many areas. The engagement and alignment of different stakeholders, including healthcare professionals and policymakers, can positively impact the implementation of a newly designed OGR intervention in the future [Citation32].

It was striking but not surprising that patients mainly expressed experiences and wishes regarding the outcomes, professionals were primarily focused on the process, and policymakers highlighted structural aspects. Being in control and having autonomy are essential topics for the patients and are related to their experienced quality of life [Citation33]. While patients indicated that being independent is essential for a better quality of life, they noted that external motivation to perform exercises and training is also necessary. Meanwhile, policymakers discussed how technology could effectively promote a patient’s autonomy. This aligns with earlier research [Citation3,Citation34–36] which demonstrated that blended eHealth applications can improve rehabilitation outcomes, such as in performing daily activities. Although our study did not indicate how to implement blended care in the OGR trajectory, the place of rehabilitation was extensively discussed. All three groups noted the advantage of providing therapy at home and on location, which aligns with the study of Prins et al. [Citation20]. A rehabilitation environment that fits the patient’s needs will improve functional outcomes and reduce negative feelings [Citation31]. Tijssen [Citation12,Citation37] demonstrated that an enriching rehabilitation environment can improve patients’ autonomy and ability to engage in daily activities and exercises, although this research primarily focuses on IGR. All three groups experienced home rehabilitation differently from IGR. Patients have to relearn behaviors at home and get used to new situations. They also typically have more ambitious goals than those put forward during IGR [Citation38]. The policymakers and professionals also felt the rehabilitation climate was missing at home. To improve this, transferring GR knowledge to PC professionals and CC nurses would be beneficial [Citation19,Citation39]. However, there is still much uncertainty about improving the rehabilitation environment at home and effectively encouraging the patient to exercise in this situation. More research is needed on the rehabilitation climate during OGR and how to promote the patient’s autonomy.

Finally, the organization and deployment of a dedicated team with specialized professionals throughout the rehabilitation process with a warm transfer to the CC nursing teams and PC was emphasized. The advantage of a dedicated team could be that patients can benefit from the specialist knowledge of the GR professionals for a more extended period [Citation31]. This is in line with research into transitional care after hospitalization [Citation38,Citation40], which shows that coordination of the transition home by a nurse and communication with integrated care are successful elements in preventing readmissions [Citation40]. Moreover, to increase the quality of care, it is necessary to strengthen collaboration and implement a person-oriented, integrated care model among providers and settings [Citation5]. It is also important to involve the patients’ social network from the beginning of the rehabilitation trajectory, which can influence the quality of GR [Citation33,Citation41].

The results of our study provide insights for structuring OGR and can be utilized by policymakers to develop the rehabilitation pathway. Further research on the effectiveness and efficiency of the elements is recommended.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this research is that a team of researchers reflected the design of OGR in the broadest way possible by exploring three specific perspectives and comparing them [Citation42–44]. Furthermore, through purposive sampling, we included a heterogeneous group of participants per perspective [Citation43,Citation44]. These points also increase the generalizability of the results to other healthcare organizations that offer OGR [Citation24,Citation42]. Although the perspectives have been collected in the Netherlands, they are in line with previous international research which demonstrated consensus that GR should preferably be offered in an outpatient setting [Citation8] and further development of OGR is needed [Citation19]. Finally, as the participants participated voluntarily, patients who felt weak and had little energy were less likely to participate, and people who had a positive experience and affinity with OGR were most willing to participate, which may have presented a distorted image and bias [Citation24,Citation44]. Nevertheless, a group of vulnerable people who are often excluded from research did participate in this study.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study provide an overview of the structure, process, and environmental components that may have an influence on the outcome of OGR with a clear focus on regaining patients’ quality of life. Essential elements are a well-coordinated dedicated team at home, patient-oriented blended eHealth applications, closer cooperation with integrated care, and the physical, and social rehabilitation environments. This provides a good foundation for further international consensus, development, and testing of blended OGR in clinical practice. It is crucial to emphasize the need for ongoing research and development in the OGR field, as the number of older people is expected to increase enormously, alongside a shortage in the workforce [Citation3–5].

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University of Amsterdam in The Netherlands (protocol ID 2021.0786).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.8 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants for their cooperation and their willingness to share their experiences and opinions. We also want to thank the organizations affiliated with the GR Development Practice; GRZPLUS (Omring and Zorgcirkel), Vivium Care Group, Zonnehuisgroup Amstelland), and the University Network for Elderly Care VUmc.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data will be made available, from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Betty Meyboom-de J, Klaske W, Anjo GB. Ageing better in the Netherlands. In: Grazia DO, Antonio G, Daniele S, editors. Gerontology. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2018. p. Ch. 6.

- Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, et al. Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):725–735. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60342-6.

- Jones M, Collier G, Reinkensmeyer DJ, et al. Big data analytics and sensor-enhanced activity management to improve effectiveness and efficiency of outpatient medical rehabilitation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):748. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030748.

- Kenneth Gopal J, Linckens D, Marchal B, et al. Sustainability of elderly care until 2050. Scenarios for future healthcare use, labor market and housing. Delft: ABF Research; 2022. p. 42.

- Health WGsoaa. UN decade of healthy ageing: plan of action 2021–2030; Geneva: 2020. p. 31.

- Lubbe AL, et al. The quality of geriatric rehabilitation from the patients’ perspective: a scoping review. Age Ageing. 2023;52(3):1–11. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afad032.

- Hatcher D, Chang E, Schmied V, et al. Exploring the perspectives of older people on the concept of home. J Aging Res. 2019;2019:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2019/2679680.

- van Balen R, Gordon AL, Schols JMGA, et al. What is geriatric rehabilitation and how should it be organized? A Delphi study aimed at reaching European consensus. Eur Geriatr Med. 2019;10(6):977–987. doi: 10.1007/s41999-019-00244-7.

- Becker C, Achterberg W. Quo vadis geriatric rehabilitation? Age Ageing. 2022;51(6):1–3. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afac040

- Holstege MS, Caljouw MAA, Zekveld IG, et al. Changes in geriatric rehabilitation: a national programme to improve quality of care. The Synergy and Innovation in Geriatric Rehabilitation study. Int J Integr Care. 2015;15(4):e045. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2200.

- Holstege MS, Caljouw MAA, Zekveld IG, et al. Successful geriatric rehabilitation: effects on patients’ outcome of a national program to improve quality of care, the SINGER study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(5):383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.10.011.

- Tijsen LM, Derksen EW, Achterberg WP, et al. Challenging rehabilitation environment for older patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1451–1460. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S207863.

- Q-consultzorg. Reporting assessment of care content geriatric rehabilitation. Utrecht: Q-conslut; 2019. p. 57.

- Nanninga CS, Postema K, Schönherr MC, et al. Combined clinical and home rehabilitation: case report of an integrated knowledge-to-action study in a Dutch rehabilitation stroke unit. Phys Ther. 2015;95(4):558–567. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130495.

- Kiel S, Zimak C, Chenot J-F, et al. Evaluation of an ambulatory geriatric rehabilitation program – results of a matched cohort study based on claims data. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-1415-5.

- Bharadwaj S, Bruce D. Effectiveness of ‘rehabilitation in the home’ service. Aust Health Rev. 2014;38(5):506–509. doi: 10.1071/AH14049.

- Ramsey KA, et al. Geriatric rehabilitation inpatients roam at home! A matched cohort study of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in home-based and hospital-based settings. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(12):2432–2439. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.04.018.

- Preitschopf A, Holstege M, Ligthart A, et al. Effectiveness of outpatient geriatric rehabilitation after inpatient geriatric rehabilitation or hospitalisation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2023;52(1):1–15. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afac300.

- Grund S, Gordon AL, van Balen R, et al. European consensus on core principles and future priorities for geriatric rehabilitation: consensus statement. Eur Geriatr Med. 2020;11(2):233–238. doi: 10.1007/s41999-019-00274-1.

- Prins LAP, Gamble CJ, van Dam van Isselt EF, et al. An exploratory study investigating factors influencing the outpatient delivery of geriatric rehabilitation. J Clin Med. 2023;12(15):5045. doi: 10.3390/jcm12155045.

- van den Besselaar J, et al. Navigate on experiences; of care receivers, caregivers and care professionals in geriatric rehabilitation, primary care residence and physician care for specific patient groups. The Netherlands: ZonMw and the Ministry of Health, Welfare & Sport; 2021. p. 53.

- Q-consultzorg. Quick scan geriatric rehabilitation care, primary care residence and additional physician care. Utrecht: Q-consultzorg; 2019. p. 36.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Los Angeles: Sage; 2006.

- Judith Green NT. Qualitative methods for health research. 4th ed. London: Sage; 2018.

- Jesus TS, Hoenig H. Postacute rehabilitation quality of care: toward a shared conceptual framework. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(5):960–969. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.007.

- Achterberg WP, Cameron ID, Bauer JM, et al. Geriatric rehabilitation-state of the art and future priorities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(4):396–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.02.014.

- Kallio H, Pietilä A-M, Johnson M, et al. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):2954–2965. doi: 10.1111/jan.13031.

- Gray LM, Wong-Wylie G, Rempel GR, et al. Expanding qualitative research interviewing strategies: zoom video communications. Qual Rep. 2020;25(5):1292–1301. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4212.

- Evers J. Qualitative interviewing; art and skills. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Boom Lemma Publisher; 2015. p. 304.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Feng W, Yu H, Wang J, et al. Application effect of the hospital-community integrated service model in home rehabilitation of stroke in disabled elderly: a randomised trial. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(4):4670–4677. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-602.

- Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2061.

- Lette M, Stoop A, Lemmens LC, et al. Improving early detection initiatives: a qualitative study exploring perspectives of older people and professionals. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0521-5.

- Pol MC, Ter Riet G, van Hartingsveldt M, et al. Effectiveness of sensor monitoring in a rehabilitation programme for older patients after hip fracture: a three-arm stepped wedge randomised trial. Age Ageing. 2019;48(5):650–657. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz074.

- Kraaijkamp JJM, van Dam van Isselt EF, Persoon A, et al. eHealth in geriatric rehabilitation: systematic review of effectiveness, feasibility, and usability. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(8):e24015. doi: 10.2196/24015.

- Muellmann S, Forberger S, Möllers T, et al. Effectiveness of eHealth interventions for the promotion of physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2018;108:93–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.026.

- Tijsen LMJ, Derksen, EWC, Achterberg WP, et al. A qualitative study exploring professional perspectives of a challenging rehabilitation environment for geriatric rehabilitation. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):2–16. doi:10.3390/jcm12031231

- van Seben R, Reichardt LA, Essink DR, et al. “I feel worn out, as if I neglected myself”: older patients’ perspectives on post-hospital symptoms after acute hospitalization. Gerontologist. 2019;59(2):315–326. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx192.

- Janssen MM, Vos W, Luijkx KG. Development of an evaluation tool for geriatric rehabilitation care. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1213-0.

- Verhaegh KJ, MacNeil-Vroomen JL, Eslami S, et al. Transitional care interventions prevent hospital readmissions for adults with chronic illnesses. Health Aff. 2014;33(9):1531–1539. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0160.

- van der Laag PJ, Arends SAM, Bosma MS, et al. Factors associated with successful rehabilitation in older adults: a systematic review and best evidence synthesis. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(1):83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.11.010.

- Yadav D. Criteria for good qualitative research: a comprehensive review. Asia Pac Edu Res. 2022;31(6):679–689. doi: 10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0.

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120–124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092.

- Johnson JL, Adkins D, Chauvin S. A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(1):7120. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7120.